Exhibition dates: 11th November 2020 – 31st May 2021

Curators: Yasufumi Nakamori, Senior Curator and Sarah Allen, Assistant Curator with Kerryn Greenberg, Head of International Collection Exhibitions, Tate and formerly Curator, Tate Modern.

Installation photograph of Zanele Muholi Exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020

Photo © Andrew Dunkley

Unclassified fabulousness

There are so many words that you can say about an artist and their work. So many unnecessary words. All you have to do is look at the work. Does it speak to you? does it make you feel, does it empower you?

For me, artists either have it or they don’t… and in this case, visual activist Zanele Muholi possesses it by the bucketful. Panache, flair, downright unclassified fabulousness, call it what you want. They just have it.

They are powerful, they are strong, they are courageous, they tell great stories, they make you question history, they make you analyse what you think you know, they challenge your memories, they make you feel something about their participants, they make you want to fight for LGBTQIA+ social rights. They make you want to stand up and fight for equality and freedom for everyone. No person is an island, alone by themselves; we should all be equal under this cosmic sky.

The older I get the less tolerant I get of the stupidity of the human race and its non-evolution, in terms of spirit of self. When is the human race going to just grow up! Ditch the patriarchy, misogyny, colonialism, racial and socio-economic oppression. Appreciate difference, value the quality of every human being, debunk the dogma of religion, curtail the power of corporations and live in harmony with the earth. Not f…ing much to ask is it, after all these thousands of years.

I won’t live to see it, but with artists like Muholi, there is hope for humanity yet. Unclassifiable. Beautiful. Hail the Dark Lioness – all power to them.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Tate Modern presents the first major mid-career survey of visual activist Zanele Muholi in the UK. Born in South Africa, Muholi came to prominence in the early 2000s with photographs that sought to envision black lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer and intersex lives beyond deviance or victimhood.

“My mission is to re-write a Black queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our resistance and existence at the height of hate crimes in South Africa and beyond.”

“In my world, every human is beautiful.”

Zanele Muholi

“Muholi prefers to be called an activist rather than an artist. Art, for them, is a means to an end, a tool to convey messages about social empowerment and visibility. “Zanele Muholi’s visual activism is not an occupation. It’s a lifestyle,” Kerryn Greenberg explains. “It’s something that occupies them day and night – whether they receive a call from someone in the community needing money to pay for a hospital appointment, or consoling those who’ve lost someone close to them in an act of violence, or giving some kind of public address at a wedding or a funeral. It’s about being a very active member of the community, and a public voice within that community.”

Maisie Skidmore. “Yes, but why? Zane Muholi,” on the We Present website [Online] Cited 11 April 2021

“The connection that Muholi has with their participants (which they are eager to distinguish from the word “subject,” which implies a distanced gaze) translates to the viewer, who, in looking at these images, is immediately welcomed into a space of understanding and empathy. Muholi also often highlights the voices of the participants in their shows, books and events. …

The political agenda of the 260 photographs on display – which critique centuries of anti-Black sentiment, oppression and erasure – echoes the rallying cry of the Black Lives Matter movement and the racial justice reckoning it has inspired worldwide. “Muholi’s work takes on an enormous importance within the context of Black Lives Matter because of its potential to educate audiences and promote mutual understanding,” said Sarah Allen. Each piece makes a clear visual statement: not only that Black queer lives matter but also that Black queer lives are nuanced, cherished and deserve to be celebrated.”

Cassidy George. “Zanele Muholi’s Photographs Celebrate Radical, Queer, Black Beauty,” on the W Magazine website 11/03/2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi – ‘In My World, Every Human is Beautiful’ / Tate

Visual activist, Zanele Muholi, uses photography and film to document and explore issues of race and representation and to celebrate the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa and beyond. Here they talk about how the power of images can show LGBTQIA+ people of South Africa, and QTIPOC people worldwide, that they are not alone. Watch as they introduce us to four key bodies of work and the ideas behind them.

Zanele Muholi: In Conversation with Lady Phyll / Artist’s Talk / Tate Exchange

Watch an in conversation between Muholi and Lady Phyll of UK Black Pride. Together, they discuss what difficult love looks like for QTIPOC communities in South Africa and Britain and the importance of chosen families.

This talk forms a part of From a Place of Love, a collaboration between Tate Exchange’s Love programme and UK Black Pride, whose theme for 2020 is home.

Born in 1972 and raised in Umlazi, a township on South Africa’s eastern coast, Muholi had a childhood shaped by the racial brutality of Apartheid – a white supremacist regime that systematically oppressed and displaced South Africa’s non white population for half a century. Muholi was an adolescent when Apartheid absolved and South Africa’s constitution was rewritten in 1996, with the intention of ushering a new era of equality. Even though South Africa’s constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, as a young queer person, Muholi was constantly reminded that the violent realities of gay life in South Africa did not align with this utopic vision of the future. Homophobia, queerphobia and transphobia remained rampant, and in South Africa, Black lesbians and transgender men are among the most at risk, and are often victims of heinous hate crimes, like “corrective” rape, abduction and murder. Drawing inspiration from the work of the American photographer Nan Goldin, whose early photographs documented queer culture and the HIV epidemic through intimate portraits of her family and friends, Muholi embarked on a mission to commemorate the battles and triumphs of her community with pictures.

Cassidy George. “Zanele Muholi’s Photographs Celebrate Radical, Queer, Black Beauty,” on the W Magazine website 11/03/2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi is a South African visual activist whose pronouns are they/them/theirs. Their work tells the stories of Black LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Agender, Asexual) lives in South Africa and beyond. Their photography raises awareness of injustices and aims to educate, while creating positive visual histories for under and mis-represented communities. Muholi also turns the camera on themself, making self-portraits that address race, history and representation. This exhibition charts Muholi’s emergence as an activist in the early 2000s to the present day.

During the 1990s, South Africa underwent major social and political change. Apartheid was officially abolished in 1994. This was a political and social system of racial segregation underpinned by white minority rule. Anyone who was not classified as white was actively oppressed by the regime. Apartheid continued the segregation that had begun under the Dutch and British colonial regimes in the late 19th century. The apartheid regime also upheld injustice and discrimination based on gender and sexuality. While the 1996 Constitution of the Republic of South Africa was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, the LGBTQIA+ community remains a target for prejudice, hate crimes and violence.

Installation photographs of Room 1 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020 showing photographs from the series Only Half the Picture (2002-2006)

Photos © Andrew Dunkley

Room 1: Only Half The Picture

This room incudes work from Muholi’s first series Only Half the Picture (2002-2006). It documents survivors of hate crimes living across South Africa and its townships. Under apartheid, townships were established as residential areas for those who had been evicted from places designated as ‘white only’. The people Muholi photographs – their participants – are presented with compassion, dignity and courage in the face of ongoing discrimination. The series also includes images of intimacy, expanding the narrative beyond victimhood. Muholi reveals the pain, love and defiance that exist within the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa.

Exhibition room guide text

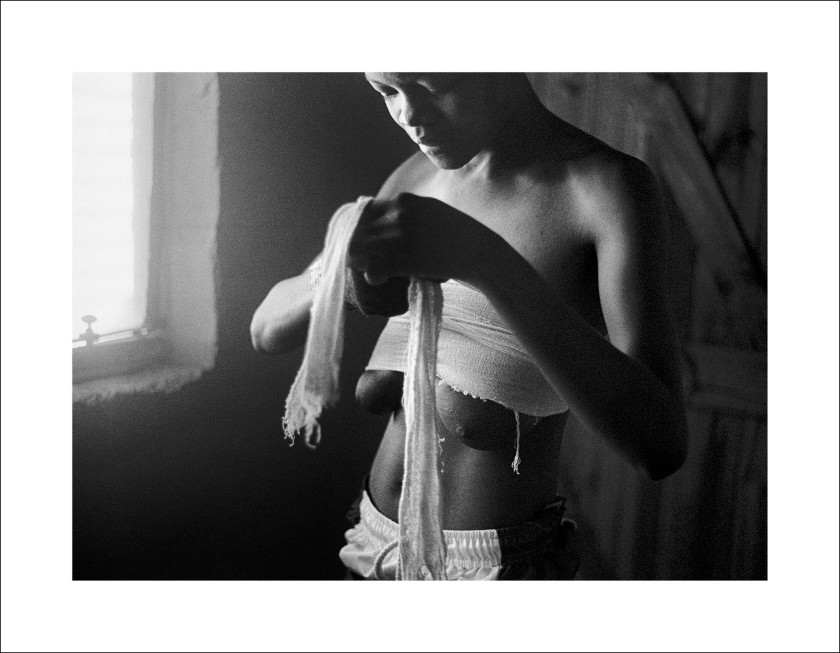

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Aftermath

2004

From the series Only Half the Picture

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

600 x 395mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

ID Crisis

2003

From the series Only Half the Picture

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

325 x 485mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

The exhibition opens with a group of deceptively gentle images. In the first, Aftermath (2004), a torso is cropped from waist to knees, hands modestly clasped in front of Jockey shorts, a huge scar running down the person’s right leg almost like a piece of body art. In another, Ordeal (2003), hands wring out a cloth in an enamel basin of water placed on a floor. A third image shows a cropped, seated figure, again waist to thighs, hands folded in their lap, plastic hospital ties around their wrists. These pictures have a softness and beauty which completely belies the fact that their subjects are all survivors of sexual violence and “corrective rape”.

As the caption to the last picture, Hate crime survivor I, Case number (2004) explains, “Corrective rape is a term used to describe a hate crime in which a person is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The intended consequence of such acts is to enforce heterosexuality and gender conformity.” This horrific practice is by no means unique to South Africa, but the term seems to have originated there – feminist activist Bernedette Muthien used it during an interview with Human Rights Watch in 2001 – and its effects on the community resonate throughout this exhibition.

Anonymous. “Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern,” on the Something I’m Working On website Wednesday 30th December 2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Installation photograph of Room 2 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020

Photo © Andrew Dunkley

Room 2: Being

This room features work from Muholi’s series Being (2006 – ongoing). The portraits capture moments of intimacy between couples, as well as their daily life and routines. Muholi addresses the misconception that queer life is ‘unAfrican’, a falsehood emerging in part out of the belief that same-sex orientation was a colonial import to Africa. Each couple is shown in the private spaces they share. Muholi explains how ‘lovers and friends consented to participate in the project, willing to bare and express their love for each other.’

Commenting on this series they say, ‘my photography is never about lesbian nudity. It is about portraits of lesbians who happen to be in the nude.’ This series dismantles the white patriarchal gaze and rejects negative or heteronormative images, common in political and social systems that uphold heterosexuality as the norm or default sexual orientation.

Since slavery and colonialism, images of us African women have been used to reproduce heterosexuality and white patriarchy, and these systems of power have so organised our everyday lives that it is difficult to visualise ourselves as we actually are in our respective communities. Moreover, the images we see rely on binaries that were long prescribed for us (heterosexual / homosexual, male/female, African / unAfrican). From birth on, we are taught to internalise their existences, sometimes forgetting that if bodies are connected, connecting, the sensuousness goes beyond simplistic understandings of gender and sexuality.

Exhibition room guide text

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg

2007

From the series Being (2006 – ongoing)

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Katlego Mashiloane and Nosipho Lavuta, Ext. 2, Lakeside, Johannesburg

2007

From the series Being (2006 – ongoing)

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Beloved V

2005

From the series Being (2006 – ongoing)

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Busi Mdaki and Malesedi Nthute, Johannesburg

2007

From the series Being (2006 – ongoing)

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

TommyBoys

2004

From the series Being (2006 – ongoing)

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

In “TommyBoys,” a colour photograph, two muscular figures in tracksuit pants sit on a tarmac. One, in a red T-shirt, sits with her hands folded against her chest, while next to her, the second uses her white vest to wipe something from her eyes. (“Tommy Boy” is a word used in South Africa, like “butch,” to refer to a masculine-presenting lesbian.)

Text from the New York Times website

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Busi Sigasa, Braamfontein, Johannesburg

2006

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Installation photographs of Room 3 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020 showing in the bottom photograph the series Miss Lesbian I-VII, Amsterdam (2009)

Photos © Andrew Dunkley

Room 3: Queering Public Space

Photographing Black LGBTQIA+ participants in public spaces is an important part of Muholi’s visual activism. This room contains portraits of transgender women, gay men and gender non-conforming people photographed in public places.

Several of the locations are important in the history of South Africa. Some images are taken at Constitutional Hill, the seat of the Constitutional Court of South Africa. It is a key place in relation to the country’s progression towards democracy. Other participants are photographed on beaches. These were segregated during apartheid. They are therefore potent symbols of how racial segregation affected every aspect of life. Participants are often shown on Durban Beach, close to Muholi’s birthplace of Umlazi.

Muholi states that ‘we’re ‘queering’ the space in order for us to access the space. We transition within the space in order to make sure that the Black trans bodies are part of this as well. We owe it to ourselves.’ Muholi often chooses to photograph participants in colour, bringing the work closer to reality and rooting them in the present day.

Exhibition room guide text

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Miss D’vine II

2007

Lambda print

765 x 765 mm

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Miss Lesbian VII, Amsterdam

2009

C-print

86.5 x 60.5cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Tate Modern presents the first major UK survey of visual activist Zanele Muholi.

Zanele Muholi is one of the most acclaimed photographers working today, and their work has been exhibited all over the world. With over 260 photographs, this exhibition presents the full breadth of their career to date.

Muholi describes themself as a visual activist. From the early 2000s, they have documented and celebrated the lives of South Africa’s Black lesbian, gay, trans, queer and intersex communities.

In the early series Only Half the Picture, Muholi captures moments of love and intimacy as well as intense images alluding to traumatic events – despite the equality promised by South Africa’s 1996 constitution, its LGBTQIA+ community remains a target for violence and prejudice.

In Faces and Phases each participant looks directly at the camera, challenging the viewer to hold their gaze. These images and the accompanying testimonies form a growing archive of a community of people who are risking their lives by living authentically in the face of oppression and discrimination.

Other key series of works, include Brave Beauties, which celebrates empowered non-binary people and trans women, many of whom have won Miss Gay Beauty pageants, and Being, a series of tender images of couples which challenge stereotypes and taboos.

Muholi turns the camera on themself in the ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama – translated as ‘Hail the Dark Lioness’. These powerful and reflective images explore themes including labour, racism, Eurocentrism and sexual politics.

Exhibition organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris, Gropius Bau, Berlin and Bildmuseet at Umeå University.

Text from the Tate Modern website

Tate Modern presents the first major UK survey of South African visual activist Zanele Muholi. Muholi (b. 1972) came to prominence in the early 2000s with photographs that told the stories of black lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer and intersex lives in South Africa. Over 300 photographs are brought together to present the full breadth of Muholi’s career to date, from their very first body of work Only Half the Picture, to their on-going series Somnyama Ngonyama. These works challenge dominant ideologies and representations, presenting the participants in their photographs as fellow human beings bravely existing in the face of prejudice, intolerance and often violence.

During the 1990s, South Africa underwent major social and political changes. While the country’s 1996 post-apartheid constitution was the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation, the LGBTQIA+ community remains a target for violence and prejudice to this day. In the early series Only Half the Picture Muholi aimed to depict the complexities of gender and sexuality for the individuals of the queer community. The collection includes moments of love and intimacy as well intense images alluding to traumatic events in the lives of the participants. Muholi also began an ongoing visual archive of portraits, Faces and Phases, which commemorates and celebrates black lesbians, transgender people and gender non-conforming individuals. Each participant looks directly at the camera, challenging the viewer to hold their gaze, while individual testimonies capture their stories. The images and testimonies form a living and growing archive of this community in South Africa and beyond.

The exhibition includes several other key series of works, including Brave Beauties, which celebrates empowered non-binary people and trans women, many of whom have won Miss Gay Beauty pageants, and Being, a series of tender images of couples which challenge stereotypes and taboos. Images like Melissa Mbambo, Durban also attempt to reclaim public spaces for black and queer communities, such as a beach in Durban which was racially segregated during apartheid. Within these series, Muholi tells collective as well as individual stories. They challenge preconceived notions of deviance and victimhood, encourage viewers to address their own misconceptions, and create a shared sense of understanding and solidarity.

More recently, Muholi has begun an acclaimed series of dramatic self-portraits entitled Somnyama Ngonyama (‘Hail the Dark Lioness’ in Zulu). Turning the camera on themself, the artist adopts different poses, characters and archetypes to address issues of race and representation. From scouring pads and latex gloves to rubber tires and cable ties, everyday materials are transformed into politically loaded props and costumes. The resulting images explore themes of labour, racism, Eurocentrism and sexual politics, often commenting on events in South Africa’s history and Muholi’s experiences as a South African black queer person traveling abroad. By enhancing the contrast in the photographs, Muholi also emphasises the darkness of their skin tone, reclaiming their blackness with pride and re-asserting its beauty. Muholi has created some new self-portraits for this series which are being shown at Tate Modern for the first time.

Zanele Muholi is co-curated by Yasufumi Nakamori, Senior Curator and Sarah Allen, Assistant Curator with Kerryn Greenberg, Head of International Collection Exhibitions, Tate and formerly Curator, Tate Modern. The exhibition is organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris, Gropius Bau in Berlin and Bildmuseet at Umeå University. Supported by the Zanele Muholi Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate Americas Foundation, Tate International Council, Tate Patrons and Tate Members . Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor.

About Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi was born in Umlazi, Durban and lives in Johannesburg. They studied at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, and Ryerson University, Toronto. Co-founder of the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, and founder of Inkanyiso, a forum for queer and visual media, Muholi is also an honorary professor at the University of the Arts Bremen, Germany. Solo exhibitions of Muholi’s work have been hosted around the world, including at the Goethe-Institut, Johannesburg (2012); Brooklyn Museum, New York (2015); Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (2017); Autograph ABP, London (2017-) and Museo de Arte moderno de Buenos Aires (2018). Muholi has won numerous awards, including the Lucie Humanitarian Award (2019), the 2019 ‘Best Photography Book Award’ by the Kraszna-Krausz Foundation for their book Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail, The Dark Lioness (Aperture), the Rees Visionary Award by Amref Health Africa (2019); a fellowship from the Royal Photographic Society, UK (2018); France’s Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (2017); the Mbokodo Award in the category of Visual Arts (2017);the ICP Infinity Award for Documentary and Photojournalism (2016); the Fine Prize for an emerging artist at the Carnegie International (2013); a Prince Claus Award (2013); and both the Casa África award for best female photographer and a Fondation Blachère award at Les Rencontres de Bamako biennial of African photography (2009). Somnyama Ngonyama was shown at the 58th Venice Biennale (2019); Faces and Phases was shown at dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) and the 55th Venice Biennale (2013).

Muholi’s pronouns are they, them, their.

Press release from the Tate website

Installation photographs of Room 4 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020 showing photographs from the series Brave Beauties (2014 – ongoing)

Photos © Andrew Dunkley

Room 4: Brave Beauties

Brave Beauties (2014 – ongoing) is a series of portraits of trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people. Many of them are also beauty pageant contestants. Queer beauty pageants offer a space of resistance within the Black LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. They are a place where individuals can realise and express their beauty outside heteronormative and white supremacist cultures. Muholi has commented that these participants ‘enter beauty pageants to change mind-sets in the communities they live in, the same communities where they are most likely to be harassed, or worse.’

This series is also inspired by fashion magazine covers. Muholi has questioned whether ‘South Africa as a democratic country would have an image of a trans woman on the cover of a magazine.’ These images aim to challenge queerphobic and transphobic stereotypes and stigmas.

As with all of Muholi’s images, the portraits are created through a collaborative process. Muholi and the participant determine the location, clothing and pose together, focusing on producing images that are empowering for both the participant and the audience.

Exhibition room guide text

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Sazi Jali, Durban

2020

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Somizy Sincwala, Parktown

2014

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

The series Brave Beauties, started in 2014, is “a series of portraits of trans women, gender non-conforming and non-binary people. Many of them are also beauty pageant contestants.” The queer beauty pageant is many things: a celebration – and redefinition – of beauty, a declaration of independence by contestants, a challenge to “heteronormative and white supremacist cultures,” and an attempt, as Muholi puts it, “to change mind-sets in the communities [the contestants] live in, the same communities where they are most likely to be harassed or worse.”

Anonymous. “Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern,” on the Something I’m Working On website Wednesday 30th December 2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Dimpho Tsotetsi, Parktown

2014

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

What I really want to talk about is beauty. Because I think for Muholi, that’s kind of where it all stems from, is recognising beauty in things that you might not expect. Muholi has said “All I want to see is beauty. And that doesn’t mean you have to smile, or try harder. Just be.”

I think that’s very much linked to the history of Apartheid, of course […] As a Black person being told constantly ‘your hair isn’t straight enough’, ‘you should look like this’, ‘you should look like that’ and that being legislated under Apartheid. But it’s also what is in the magazines, this idea of the perfect beauty. Muholi’s counteracting them, saying actually, none of that is relevant. It’s about being the beauty that you want to be.

There’s a really great series called Brave Beauties, which […] pictures trans women and gender non-binary individuals, many of whom have been in beauty pageants, occupying space. Demanding attention. And being absolutely stunningly beautiful. And you kind think, ‘yeah, what are our notions of beauty, what are these kind of constructions that are absolutely false?’

Kerryn Greenberg

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Eva Mofokeng II, Parktown, Johannesburg

2014

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Installation photograph of Room 5 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020

Photo © Andrew Dunkley

Room 5: Collectivity

Collectivity lies at the heart of Muholi’s work. Many of Muholi’s large network of collaborators are members of their collective, Inkanyiso. This means ‘light’ in isiZulu, Muholi’s first language and one of 11 official languages in South Africa. Inkanyiso’s mission is to ‘Produce, educate and disseminate information to many audiences, especially those who are often marginalised or sensationalised by the mainstream media.’ Queer Activism = Queer Media, is the collective’s motto.

Self-organisation, mentorship and skill sharing are central to Muholi’s collaborative activity. This room features images that are collaboratively made. Whether documenting public events such as Pride marches and protests, or private events such as marriages and funerals, these images form an ever-expanding visual archive. By recording the existence of the Black LGBTQIA+ community, they resist erasure.

Exhibition room guide text

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Lerato Dumse, Muntu Masombuka’s Funeral, Johannesburg

2014

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Room 6: Faces and Phases

Muholi began their ongoing series Faces and Phases in 2006. The project currently totals 500+ works. As a collective portrait, it celebrates, commemorates and archives the lives of Black lesbians, transgender and gender non-conforming individuals.

It is important to mark, map and preserve our mo(ve)ments through visual histories for reference and posterity so that future generations will note that we were here.

Many of these portraits are the result of a long and sustained relationship and collaboration. Muholi often returns to photograph the same person over time. Faces refers to the person being photographed. Phases signifies a transition from one stage of sexuality or gender expression and identity to another. It also marks the changes in the participants’ daily lives, including ageing, education, work experience and marriage. The gaps in the grid indicate individuals that are no longer present in the project, or a portrait yet to be taken. One wall in the exhibition is dedicated to the participants who have passed away.

Faces and Phases forms a living archive that visualises Muholi’s belief that ‘we express our gendered, radicalised, and classed selves in rich and diverse ways.’

Exhibition room guide text

Installation photographs of Room 6 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020 showing Muholi’s series Faces and Phases (2006 – ongoing)

Photos © Andrew Dunkley

Faces and Phases is an ongoing series whereby the artist was seeking to document and photograph Black lesbians, trans men and gender non-conforming individuals. There’s now a mass of these incredibly beautiful portraits, which generally are presented in a grid, to show that, actually […] giving visibility to these people is a life’s work. There are many portraits of the same individuals over the course of a number of years. So you can see how people age, how they transition, sometimes, and how the way they present themselves, alters.

It is about acknowledging pain and trauma, and trying to heal people, and heal oneself through those images. Images that Muholi wants their community, to be proud of, and feel well represented by.

Kerryn Greenberg

Death is a constant presence in Muholi’s community and work. The largest space in this exhibition is given to Faces and Phases (2006 – ongoing), a collection of portraits – 500, and counting. The images “celebrate, commemorate and archive the lives of Black lesbians, transgender and gender non-conforming individuals.” People appear more than once. Some spots on the walls are empty, marking a portrait yet to be taken or a participant no longer there. One wall is dedicated to those who have passed away.

Anonymous. “Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern,” on the Something I’m Working On website Wednesday 30th December 2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Tumi Mokgosi, Yeoville, Johannesburg

2007

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Nosipho Solundwana, Parktown, Johannesburg

2007

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Manucha, Muizenberg, Cape-Town

2010

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Nokuthula Dhladhla, Berea, Johannesburg

2007

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

TK Tekanyo, Gaborone, Botswana

2010

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Zukiswa Gaca Makhaza, Khayelitsha, Cape-Town

2010

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Marcel Kutumela, Alexandra, Johannesburg

2008

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Lungile Cleo Dladla, KwaThema, Community Hall, Springs, Johannesburg

2011

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Installation photograph of Room 7 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020

Photo © Andrew Dunkley

Room 7: Sharing Stories

From their earliest days as an activist, Muholi sought to record first-hand testimonies and experiences of Black LGBTQIA+ people. Giving participants a platform to tell their own story, in their own words, has been an enduring goal. They have said:

Each and every person in the photos has a story to tell but many of us come from spaces in which most Black people never had that opportunity. If they had it at all, their voices were told by other people. Nobody can tell our story better than ourselves.

In this room, eight participants share stories of their lives and experiences as members of the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa. Some of them feature in the Faces and Phases project in the previous room. The interviews have been conducted and produced by Muholi’s collaborators, some of whom are members of Inkanyiso. Some testimonies do not use Muholi’s preferred gender pronouns they, them, theirs.

Exhibition room guide text

Installation photographs of Room 8 of the Zanele Muholi exhibition, Tate Modern, November 2020 showing Muholi’s series Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness

Photos © Andrew Dunkley

Room 8: Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness

Somnyama Ngonyama (2012 – ongoing) is a series in which Muholi turns the camera on themself to explore the politics of race and representation. The portraits are photographed in different locations around the world. They are made using materials and objects that Muholi sources from their surroundings.The images refer to personal reflections, colonial and apartheid histories of exclusion and displacement, as well as ongoing racism. They question acts of violence and harmful representations of Black people. Muholi’s aim is to draw out these histories in order to educate people about them and to facilitate the processing of these traumas both personally and collectively.

Muholi considers how the gaze is constructed in their photographs. In some images they look away. In others they stare the camera down, asking what it means for ‘a Black person to look back’. When exhibited together the viewer is surrounded by a network of gazes. Muholi increases the contrast of the images in this series, which has the effect of darkening their skin tone.

I’m reclaiming my Blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other.

The titles of the works in the series remain in isiZulu, Muholi’s first language. This is part of their activism, taking ownership of and pride in their language and identity. It encourages a Western audience to understand and pronounce the names. This critiques what happened during colonialism and apartheid. Then, Black people were often given English names by their employers or teachers who refused to remember or pronounce their real names.

Exhibition room guide text

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Fisani, Parktown

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Thulani II, Parktown

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Ziphelele, Parktown

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

MaID-IV, New York

2018

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Yaya Mavundla, Parktown, Johannesburg

2014

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Roxy Msizi Dlamini, Parktown, Johannesburg

2017

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Ntozakhe II, Parktown

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Sebenzile, Parktown

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

As Muholi’s career started to take off internationally, they were traveling a huge amount in hotel rooms. They were exposed to the usual hassles of border immigration and airports, where racial profiling is still a reality, and entering spaces that are historically white. [They were] very conscious of the feeling that perhaps they were not quite wanted there, despite having been invited.

In 2012, they began to make a series of self-portraits, which actually I think are more accurately presented as self-projections, rather than self-portraits. In them, there is this sense of unapologetic selfhood. The sense that actually, you can be Black, you can encompass many histories, and projecting that in a really powerful way.

These photographs are often taken in situations, as I said, away from home, where Muholi might not have access to the same camera each time. And the light conditions are very variable. So, you’ll see that when they’re printed, they’re at very different scales, and that is representative of the fact that they’ve been made on the hop.

The itineracy of the lifestyle is very much evident in the pictures themselves, but also in the titles. They’re often titled in isiZulu, the artist’s home language. But then there will be the place in which they’ve been made, and that could be New York, that could be Norway, you know, a whole range of different locations.

Kerryn Greenberg

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Zazi II, Boston

2019

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Xiniwe at Cassilhaus

2016

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

The unforgettable works in Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness are a divine ode to Black women past and present, in Africa and beyond. In this series of black and white self portraits, Muholi becomes the participant, encouraging viewers to question what they were taught to find beautiful, and why. Often adorning themselves with different domestic materials as a tribute to their mother, who was a domestic worker for a white family (and resultantly absent from Muholi’s childhood), Muholi alludes to the broader history of colonisation and enslavement. Muholi also uses symbolically loaded poses and props which both summon and challenge visual stereotypes of African women and oppressive white beauty standards. By drawing on familiar aesthetic tropes, like fashion magazine covers and advertisements, Muholi dismantles the Western narrative by replacing the typically white bodies and faces that fill these frames with depictions of radical, queer, Black beauty.

Cassidy George. “Zanele Muholi’s Photographs Celebrate Radical, Queer, Black Beauty,” on the W Magazine website 11/03/2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Vile, Gothenburg, Sweden

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Somnyama Ngonyama II, Oslo

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Bona, Charlottesville

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Bester VIII, Philadelphia

2018

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

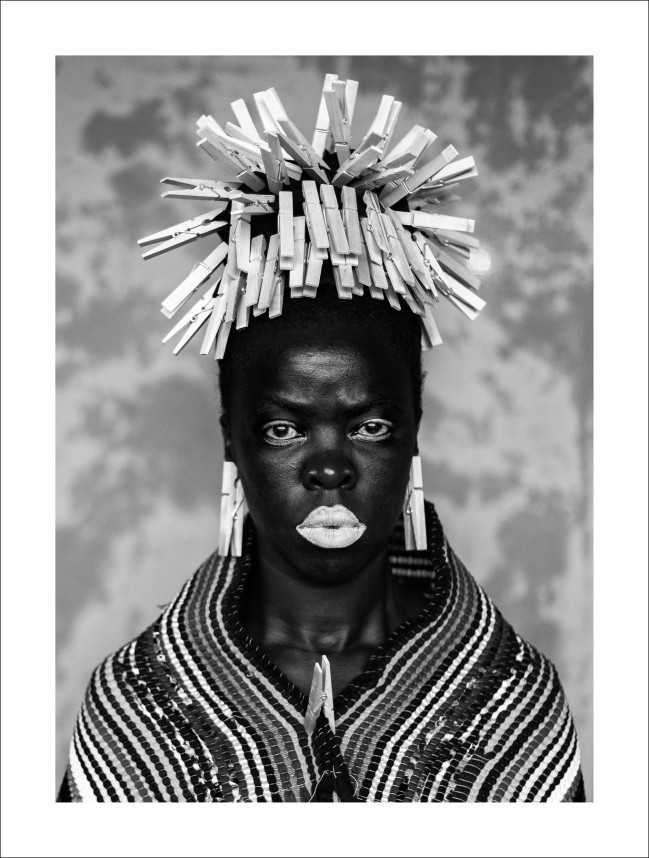

Bester I

“This self-portrait is a special tribute to my late mother who passed on in 2009. She worked as a domestic worker for 42 years and was forced to retire due to ill health. After retirement she never lived long enough to enjoy her life at home with her family and grandchildren.

This photo is also a dedication to all the domestic workers around the globe who are able to fend for their families despite meagre salaries and make ends meet.

With this image I looked at how different people can use the materials of daily life for multiple purposes. The pegs lend an unexpected aesthetic to this photo and allow it to be read differently in the fashion world; the same goes for the striped mat. The pegs themselves can be seen as functional art in this regard. The striped doormat can also be used as shawl, but in this case it was meant for something else.

What people call a prop, I call material. The viewer is forced to rethink how they think about the materials – and their history.

I looked directly at the camera in order to create a sense of questioning or confrontation which could be read by viewers in different ways.”

~ Zanele Muholi, March 2017

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Bester I, Mayotte

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Buhlalu I, The Decks, Cape Town

2019

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Qiniso, The Sails, Durban

2019

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness

In this work, Muholi has darkened their skin and whitened their eyes, and composed the picture in the manner of a classical, perfectly-lit studio portrait, posing with found objects as “costume” – a footstool as a helmet, say. There is so much to unpick in these images – references to colonialism, Apartheid, to the politics of race and representation, to femininity and “women’s work”. Muholi presents us with a kaleidoscope of views of injustice, equal parts beautiful and brutal.

The intellectual focus of every picture is slightly different. Zamile, KwaThema (2016) shows Muholi draped in a striped blanket, as used in South African prisons during Apartheid. In Quinso, The Sails, Durban (2019) Muholi’s hair is adorned with silvery Afro combs, a symbol of African and African diaspora cultural pride. In Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy (2015) their hair is stuffed with pens – a reference to the “pencil test” whereby, under Apartheid, if a pencil pushed into a person’s hair fell out they were “classified as white”.

Anonymous. “Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern,” on the Something I’m Working On website Wednesday 30th December 2020 [Online] Cited 11/05/2021

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Nolwazi II, Nuoro, Italy

2015

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Lulamile, Room 107 Day Inn Hotel, Burlington

2017

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

Zanele Muholi (South African, b. 1972)

Untitled

Nd

Courtesy of the Artist and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

© Zanele Muholi

FEW Stop the War on Women’s Bodies poster

c. 2005

Room 9: Tracing Contexts

Muholi defines themself as a visual activist. They were born in 1972 during the height of apartheid in South Africa. Today their work celebrates LGBTQIA+ identity in the new era of democracy after apartheid was brought to an end in 1994, while also addressing the ongoing risks that the community face. Muholi has spoken about this being the very means through which they ‘claim their full citizenship’. The artist’s place within South African histories of activism, both as they relate to apartheid and the emergence of queer activism, are explored in this timeline. The timeline helps to highlight particular contexts from which Muholi’s work emerges and remains deeply rooted.

Zanele Muholi: Glossary

The terms included in this glossary are culturally complex and nuanced. Whilst the co-authors and editors of this text have attempted to reflect this, it is worth noting that the interpretations offered here are not definitive, as the meanings of many of the terms herein are deeply subjective and are consistently contested, debated and re-evaluated.

Ally

An individual who actively supports the social movements and rights of LGBTQIA+ and other marginalised identities, but who does not identify as LGBTQIA+ or as a member of said marginalised groups.

Apartheid

A former policy / oppressive system that was officially implemented in South Africa from 1948 until 1994, to enforce racial segregation and political, economic and social discrimination against people of colour or anyone who was not classified as white. The word ‘apartheid’ is an Afrikaans word meaning ‘apartness’. The term has also been used to refer to global forms of institutionalised / systemic racial and socio-economic oppression that is still prevalent in societies across the world.

Asexual

An umbrella term used to describe those with a variation of romantic and/or sexual attraction, including a lack of attraction. The term can also describe people who are emotionally, psychologically and intellectually attracted to people, or where their attraction is not limited to physical sexual expression.

Assignment

Within the dominant culture informed by Western scientific models that classify gender and sex as binary, gender and sex are commonly assigned at birth based on external biological sex characteristics (genitalia) and reproductive functions. A vulva-bearing child is typically assigned female at birth (commonly shortened to ‘AFAB’), while a penis bearing child is typically assigned male at birth (commonly shortened to ‘AMAB’). AFAB and AMAB are terms commonly used by transgender, gender-non-conforming and non-binary people to demonstrate that the sex and / or gender one was assigned at birth may not necessarily match one’s true gender identity.

Bisexual

An umbrella term used to describe a romantic and / or sexual orientation towards more than one gender. Bisexual people may describe themselves using one or more of a variety of terms, including (but not limited to) pansexual and queer.

Black

Capitalise when used to describe someone’s race, ethnicity or culture, unless the individual or group self-identifies otherwise.

Black Lesbian Feminism

A political identity, movement and school of thought that incorporates perspectives, experiences and politics around race, gender, class and sexual orientation, and surfaces the inextricable links between them.

Butch

A term used in queer culture to describe someone who often (but not always) expresses themselves in a typically masculine way. This term should not be used to describe someone unless they expressly identify as such.

Cis / Cisgender

A term used to describe someone whose gender identity matches the sex and gender they were assigned at birth.

Civil Union

Also known as a civil partnership, a civil union is a legally recognised arrangement which grants most or all of the rights, responsibilities and legal consequences of a marriage except the title itself. Civil unions were created primarily to provide recognition in law for same-sex couples and partnerships.

‘Corrective Rape’

A term used to describe a hate crime in which a person is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The intended consequence of such acts is to enforce heterosexuality and gender conformity.

Family

A term widely used by queer and trans people to identify other queer and trans people. Also known as ‘chosen family’.

Femme

A term used in LGBTQIA+ culture to describe someone who often (but not always) expresses themselves in a typically feminine way. This term should not be used to describe someone unless they expressly identify as such.

Gay

A term used to refer to a man, trans person or non-binary person who tends to have a romantic and / or sexual orientation towards men. The term can also be used more broadly and colloquially to describe a same-sex or queer orientation.

Gender

Often expressed in terms of masculinity and femininity, gender is culturally determined and is assumed from the sex assigned at birth. One’s gender is made up of one’s gender identity (a person’s innate sense of their own gender) and gender expression (how a person outwardly expresses their gender).

Gender Binary

The system of dividing gender into two distinct categories – man and woman – thus excluding non-binary and gender-nonconforming individuals.

Gender Dysphoria

Used to describe a person’s discomfort or distress because there is a mismatch between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity.

Gender Non-conforming / Non-conformity

A person who does not conform to the binary gender categories that society prescribes (man and woman) through their gender identity/expression.

Hate Crime

Any incident that may or may not constitute a criminal offence, perceived as being motivated by prejudice or hate. The perpetrators seek to demean and dehumanise their victims, whom they consider different from them based on actual or perceived race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation, disability, health status, nationality, social origin, religious convictions, culture, language or other characteristics.

Heteronormativity

A socio-political system that, predicated on the gender binary, upholds heterosexuality as the norm or default sexual orientation.

Heteronormativity encompasses a belief that people fall into distinct and ‘complementary’ genders (men and women) with natural roles in life. It assumes that sexual, romantic and marital relations are most fitting between a cisgender man and a cisgender woman, positioning all other sexual orientations as ‘deviations’.

Homonationalism

A form of LGBTQIA+ advocacy that frames LGBTQIA+ rights in nationalistic terms that privilege North American and European expressions over those of the Middle East and the Global South, particularly Africa.

Homonationalism sees the conceptual realignment of LGBTQIA+ activism to fit the goals and ideologies of both neoliberalism and the far right in order to justify racist, classist, Islamophobic and xenophobic perspectives. This framing is based on prejudices that migrant people are supposedly homophobic, and that western society is egalitarian.

Homophobia

The fear or dislike of someone based on prejudice or negative attitudes, beliefs or views about LGBTQIA+ people.

Homosexual

A person who has a romantic and / or sexual orientation towards someone of the same gender. ‘Homosexual’ is often considered a more medical term. The terms ‘lesbian’ and ‘gay’ are now more generally used.

Intersectionality

Emerging from the traditions of critical race theory, womanism and Black feminist thought, intersectionality encompasses the study of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination or discrimination. The term was formalised by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 in a discussion around Black women’s employment in the US. Intersectionality rejects the notion of universal experiences of womanhood in favour of a more holistic assessment of how one’s race, class, ethnicity, age, ability, sexuality, nationality and religion can impact one’s experience of womanhood or gender, but also how these social inequalities intertwine with and shape one another.

Intersex

A term used to describe a person who may have biological attributes that do not fit with societal assumptions about what constitutes ‘male’ or ‘female’. These biological variations may manifest in different ways and at different stages throughout an individual’s life. Being intersex relates to biological sex characteristics and is distinct from a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

isiNgqumo

A type of language used amongst the LGBTQIA+ community in South Africa, mostly among the Nguni people.

isiStabane / Stabane

A slur or derogatory isiZulu term used in vernacular language to refer to a person who is from the LGBTQIA+ community in the Southern African context. Translated into English, the term means a person who is born with both male and female ‘parts’.

Lesbian

A term used to refer to a woman, trans person or non-binary person who tends to have a romantic and / or sexual orientation towards women or non-binary femmes.

LGBTQIA+

An acronym standing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual. This is not an exhaustive list, as denoted by the inclusion of the plus symbol, which nods to the varying sexual orientations and gender identities that exist around the world.

Lobola

Also known as lobolo, lobola is a customary practice of marriage whereby the bridegroom’s family and kin transfer certain goods to the bride’s family in order to validate a customary marriage. Historically this was in the form of cattle, but today monetary payment is preferred, depending on the bride’s family.

MSM

An acronym standing for men who have sex with men. MSM may or may not identify as gay, queer or bisexual.

Necklacing

A practice of extrajudicial torture and execution whereby a burning rubber tyre is forced around a person’s neck. Under apartheid, necklacing was sometimes used within the Black community to punish those who were perceived to have collaborated with the apartheid government.

Non-binary

An umbrella term for people whose gender identity does not sit comfortably with ‘man’ or ‘woman’ (also often referred to as genderqueer). Non-binary identities are varied and can include people who identify with some aspects of binary identities, while others reject them entirely.

Outed

When an LGBTQIA+ person’s sexual orientation or gender identity is disclosed without their consent.

Pansexual

A term that refers to a person whose romantic and/or sexual attraction towards others is not limited by sex or gender.

Passbook (dompas) / Reference book

An identification book or document that every person of colour or anyone who was not classified as white had to carry under the pass laws of apartheid. The book was made up of two parts. One part had a laminated identity card that featured the name of the bearer, their ethnic affiliation, the date the card was issued, the signature of an official and a black and white portrait photograph. The other part included five sections which listed information on permissions to enter urban areas, record of required medical examinations, names and addresses of employers, work status and receipts for tax payments. Colloquially, among the Black South African population, these passes were often referred to derogatorily as the dompas, an Afrikaans term literally meaning ‘dumb’ / ‘stupid pass’.

Patriarchy

A social hierarchy that privileges and prioritises men over women and other gender identities.

Pencil Test

A racist, dehumanising test that was devised to assist authorities in racial classification under apartheid. When officials were unsure if a person should be classified as white or of colour, a pencil would be pushed into their hair. If the pencil fell out, signalling that their hair was straight rather than curly, kinky or coily, the person ‘passed’ and was ‘classified’ as white.

People / Person of Colour (POC)

A term used to denote someone who is not considered white. The term is used to emphasise the common experiences of systemic racism amongst people of colour.

Pinkwashing

A term with multiple meanings, but that commonly refers to the appropriation of the LGBTQIA+ movement in order to promote some corporate or political agenda. The term is used to describe the practices of entities who market themselves as ‘gay-friendly’ to gain favour with progressives, while simultaneously masking aspects of their practices that are violent and undemocratic.

Pronouns

Words we use to refer to people’s gender in conversation – for example, ‘he’ or ‘she’, or gender-neutral pronouns such as ‘they’.

QTIPOC

An acronym standing for queer, trans and intersex people of colour.

Queer

An umbrella term used by those who reject heteronormativity. Although some people view the word as a slur, it was reclaimed by the queer community, who have embraced it as an empowering and subversive identity.

Safe space

An environment that enables all persons, including sexual and gender minorities, to be free to express themselves without fear of discrimination or violation of their rights and dignity. Individual actions and reactions are key in upholding or violating a safe space.

Sangoma

A traditional African healer who specialises in treating people’s spiritual and physical diseases by looking into their past and future and connecting them with the ancestors. Healers believe that they are called by their ancestors to take on this important and respected position in society.

Sex

Sex is distinct from gender. Sex is assigned to a person at birth on the basis of biological sex characteristics (genitalia) and reproductive

functions.

Transgender

An umbrella term used to describe people whose gender is not the same as, or does not sit comfortably with, the sex they were assigned at birth. Some transgender people are binary-identified and others are not.

Transition

The steps a trans person may take to live in the gender with which they identify. Each person’s transition involves different processes. For some this involves medical intervention or gender affirming healthcare such as hormone therapy and surgeries (medical transition), but not all trans people want or are able to have this. Transitioning might also involve things such as telling friends and family, dressing differently, changing one’s pronouns (social transition) and changing official documents (legal transition).

Transmisogynoir

A term that characterises the marginalisation of Black trans women and transfeminine people and captures the intersection of transphobia, racism and misogyny. It is used to denote the fact that Black trans women experience a different, racialised form of misogyny that is compounded with transphobia.

Transmisogyny

A term capturing the interlocking discrimination of transphobia and misogyny. Transmisogyny includes negative attitudes, hate and discrimination toward transgender individuals who fall on the feminine side of the gender spectrum, particularly trans women and transfeminine people.

Transphobia

The fear or dislike of someone based on the fact that they are transgender, including the denial / refusal to accept their gender identity.

White Supremacy

A racist ideology in which people defined and perceived as white are positioned as superior to and should dominate people of other races, and the practices based on this ideology.

WSW

An acronym standing for women who have sex with women. WSW may or may not identify as lesbian, queer or bisexual.

Zulu

A Bantu ethnic group and language of Southern Africa situated within the Nguni people. They are a branch of the southern Bantu and have close ethnic, linguistic and cultural ties with the Swazi and Xhosa. The Zulu are South Africa’s largest ethnic group, with an estimated population of 10 million, residing mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

United Kingdom

Opening hours:

Sunday – Thursday 10.00 – 18.00

Friday – Saturday 10.00 – 22.00

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/renger-patzsch-bugeleisen-fur-schuhfabrikation.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Gebirgsforst im Winter (Fichtenwald im Winter)' [Mountain forest in winter (spruce forest in winter)] 1926](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/renger-patzsch-gebirgsforst-im-winter.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Max Burchartz. 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928 Max Burchartz. 'Lotte (Eye)' (Lotte [Auge]) 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/04/max-burchartz-lotte-eye-1928-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Fenêtre [Window]' 1929 Florence Henri. 'Fenêtre [Window]' 1929](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/florencehenri_06_fenetre-web.jpg?w=650&h=883)

![J. E. Bray (Australian, 1832-1891) 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880 J. E. Bray (Australian, 1832-1891) 'Untitled ["McDonnell's Tavern opposite Railway Station, remains of Dan Kelly and Hart in coffins"]' 1880](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/bray-je-mcdonnells-railway-tavern-web.jpg?w=840)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/exhi032777-web.jpg?w=650&h=652)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/exhi037605-web.jpg)

![Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903 Auguste Rodin (French, 1840-1917) 'Le Penseur [The Thinker]' 1903](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/rodin-le-penseur-web.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914 Vassily Kandinsky (Russian, 1866-1944) 'Bild mit rotem Fleck [Tableau à la tache rouge / Image with red spot]' 25 February 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/kandinsky-bild-mit-rotem-fleck-web.jpg?w=650&h=651)

You must be logged in to post a comment.