Exhibition dates: 31st May – 24th July 2016

National Gallery of Australia touring exhibition

Curator: Shaune Lakin

Installation view of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne.

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

An independent vision

Pictorialism, Surrealism and Modernism: Light, geometry and atmosphere

This is the quintessential hung “on the line” exhibition from the National Gallery of Australia which features the work of two well respected Australian photographers, Max Dupain and Olive Cotton, showing over three gallery spaces at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne. Of its type, it is a superb exhibition which rewards repeated viewing and contemplation of the many superb photographs it contains.

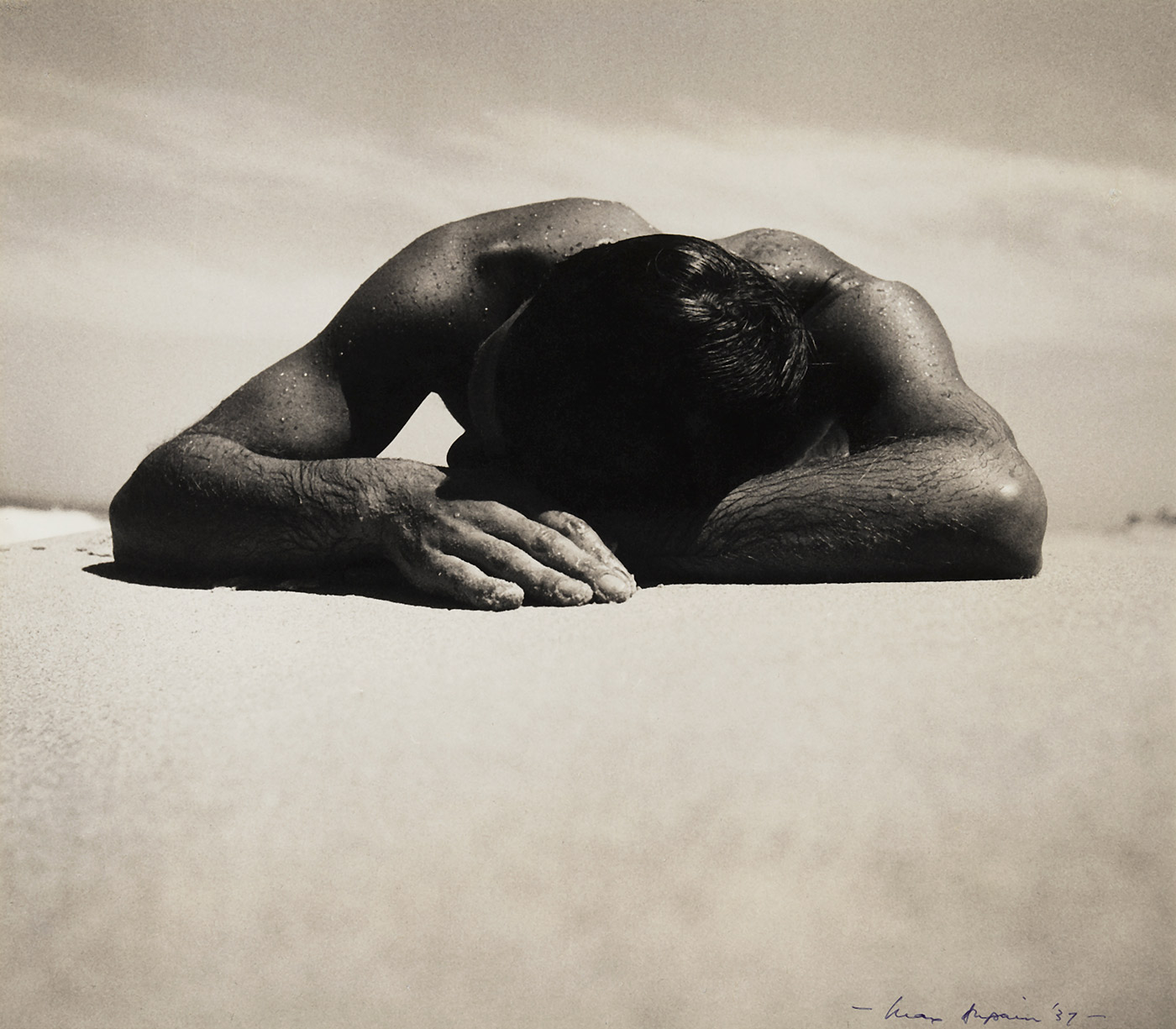

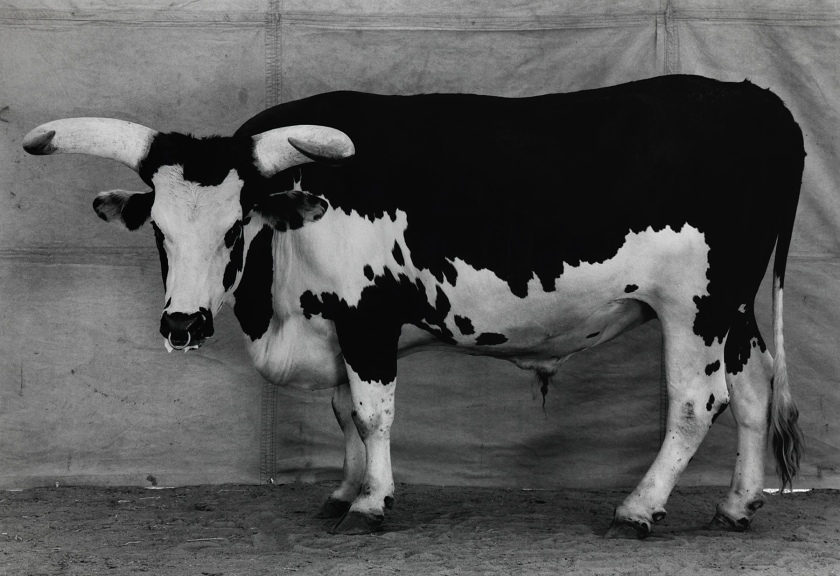

While Dupain may be the more illustrious of the two featured artists – notable for taking the most famous photograph in Australian photographic history (Sunbaker, 1937, below); for being the first Australian photographer to embrace Modernism; and for bringing a distinctly Australian style to photography (sun, sea, sand) – it is the artist Olive Cotton’s work that steals almost every facet of this exhibition through her atmospheric images.

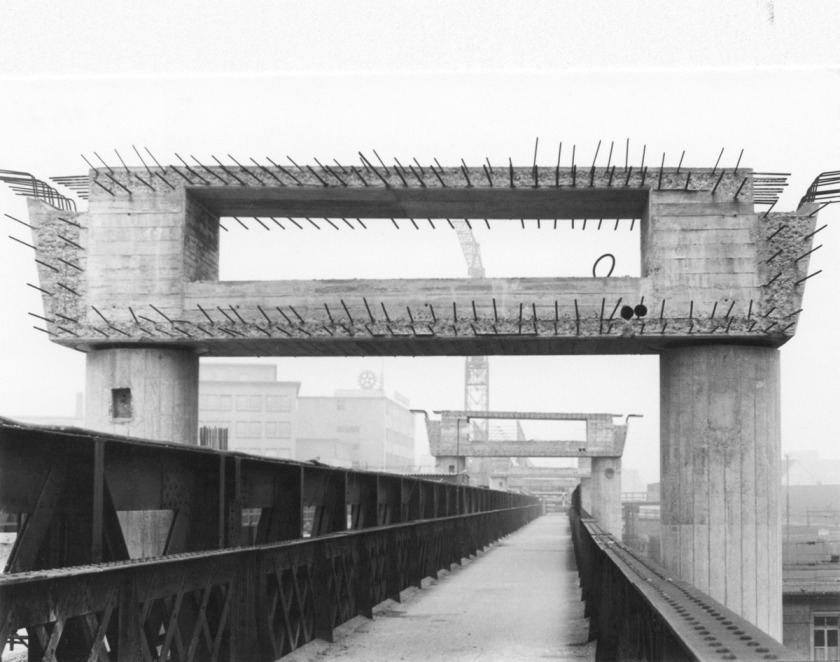

Dupain’s importance in the history of Australian photography cannot be underestimated. He dragged Australian photography from Pictorialism to Modernism in a few short years and met fierce resistance from the conservative camera clubs, stuck in the age of Pictorialism, because of it. He was the first to understand what Modernism meant for the medium in Australia, and how photographers would in future picture the country. He wanted to see the world through ‘modern’ eyes. As he observed, ‘(photography) belongs to the new age … it is part and parcel of the terrific and thrilling panorama opening out before us today – of clean concrete buildings, steel radio masts, and the wings of the air line. But its beauty is only for those who themselves are aware of the ‘zeitgeist’ – who belong consciously and proudly to this age, and have not their eyes forever wistfully fixed on the past.’ Dupain’s awareness of the ‘zeitgeist’ of modernity was coupled with a keen eye for composition, light and form (what Dupain later termed ‘passing movement and changing form’), and an understanding of photography’s expressive potential. Over the next 50 years he captured many memorable images, some of the most famous images ever taken of this sun burnt country.

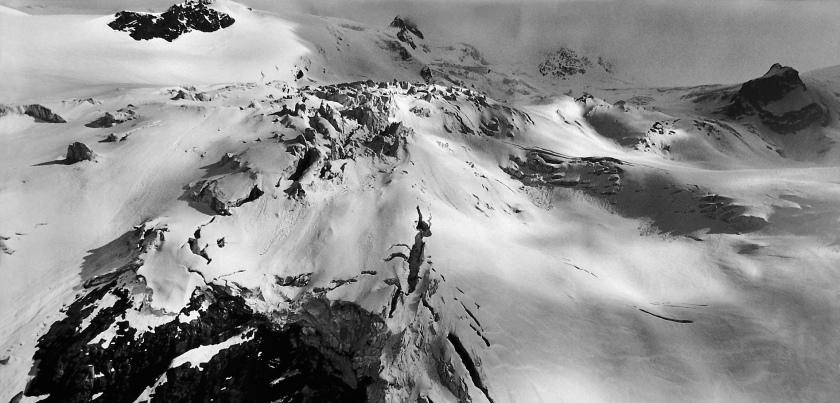

Dupain started to hit his straps with his early cross-over images which contained elements of both Pictorialism and Modernism. His 1930s series of three photographs of Fire Stairs at Bond Street Studio (one of which is feature in the exhibition), and images such as Design – suburbia (1933, below) and Still life (1935, below) still possess that soft, raking light that was so beloved by Pictorialists, coupled with an implicit understanding of form, geometry and light. As fellow photographer David Moore observes, by the time of photographs such as Pyrmont silos (1935, below) and Through the Windscreen (1935), ‘any return to sentimental Pictorialism was precluded’. That sense of the European avant-garde, the aesthetics of contemporary European photography, the strength of industrial forms, imbues Dupain’s photographs with a crisp, clean decisiveness, that ‘symphony of forms and textures’. Whether it be the monumentalism of silos, or the monumentalism of bodies (such as in the classic Bondi, 1939), Dupain relished the opportunity to merge aesthetics with representation, pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible within the medium, believing that both representation and aesthetics could exist within the same frame. Evidence of this merging of can be seen in photographs such as Untitled [Factory chimney stacks] (1940, below) and Backyard, Forster, New South Wales (1940, below). These images are silent in their formalism… they are very quiet, and still, and rather haunting, beautiful in their tonality (with lots of yellow in the 8 x 10 and perhaps even small prints).

Dupain and Cotton both revel “in photography’s great capacity to make sense of the relations of light, texture and form as they exist in the present,” and evidence “a modernist concern with line, form and space; documentary photography’s interest in realism and ‘the living moment’; and the pictorial and formal attributes of commercial photography.” But as the press release insightfully observes, “Comparisons articulate and make apparent Dupain’s more structured – even abstracted – approach to art and to the world; similarly, comparisons highlight Cotton’s more immersive relationship to place, with a particularly deep and instinctual love of light and its ephemeral effects.” And this is where the photographs of Olive Cotton are so much more engaging, and alive, than those of Max Dupain.

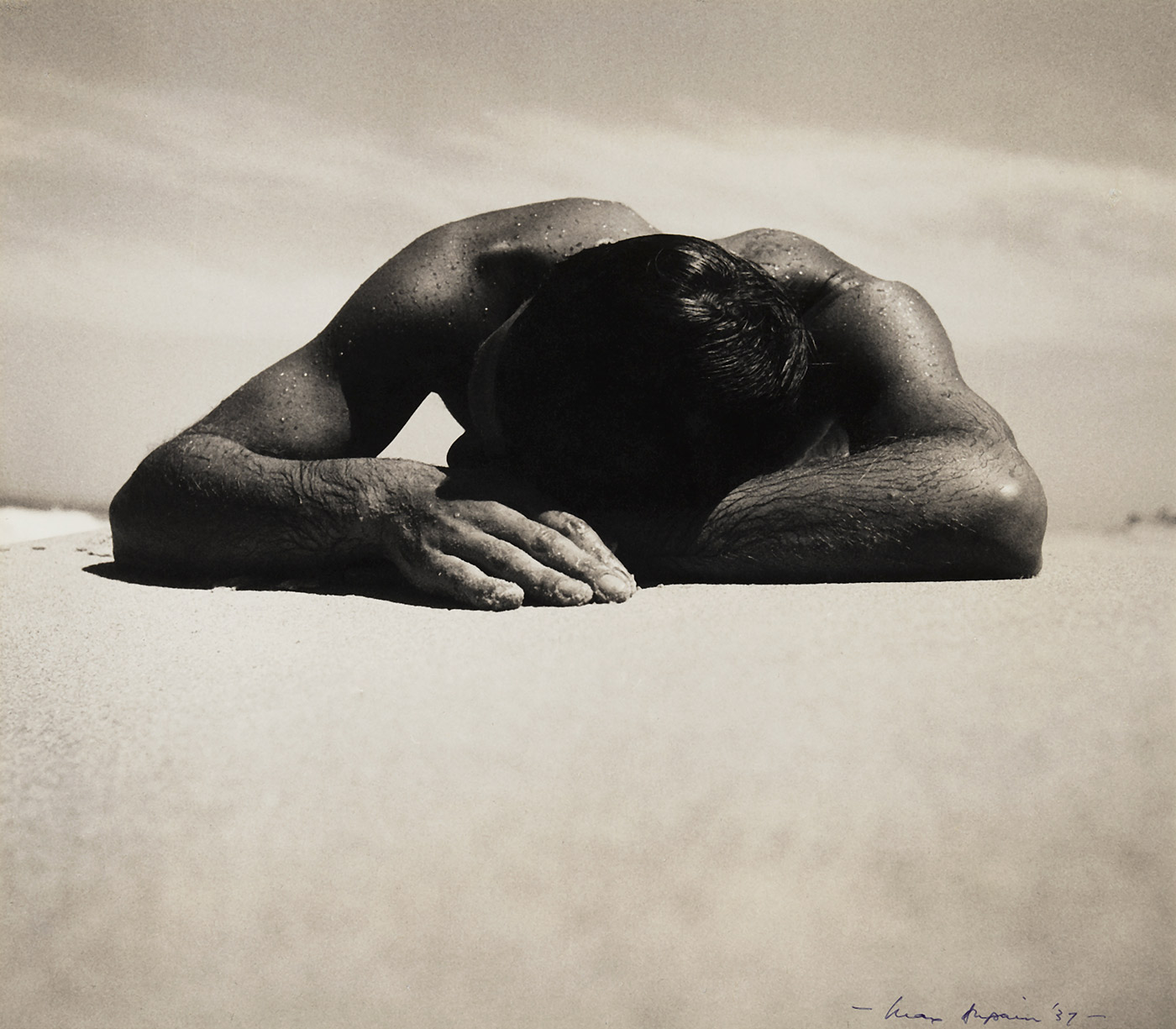

While Dupain was busy running a commercial studio (with Cotton his assistant and for a couple of years his wife), Olive seems to have had more freedom to experiment, to express herself in a less structured way than her erstwhile husband. Walking around this exhibition my initial thoughts were wow, Olive Cotton, you are an absolute star. Photographs such as The way through the trees (1938, below), while not possessing the technical brilliance of a Dupain, possess something inherently more appealing – a sensitivity and feeling for subject that nearly overwhelms the senses. Truly here is a symphony of texture, light and form. The composition is a subtle paean, a song of praise to the natural and modern world – a world of geometry, textures, light and form. The rendition of this image, a performance of interpretation, is simply magnificent in its sensitivity to subject matter. The print is also glorious in its delicacy and colour. For me, this is what is so appealing about the work of Olive Cotton, an innate sensitivity that all of her photographs seem to possess – in composition, in proportion, in printing and in colour. Cotton maintained an independent vision forged out of experimentation, creating spaces for erotic imaginings, spaces for action and spaces for quiet contemplation. Her use of light and shade, of body and shadow, of classical and modernist motifs … is superlative. While Dupain’s photographs are more structured and more dazzling in a technical sense, Cotton’s photographs possess more “atmosphere”, a complex and insightful way of seeing and imaging the world which has few equals in the annals of Australian photography.

Below is a short transcription of a voice memo I made on my phone as I toured around the exhibition for the third time:

“What a great show this is, the photographs of Max Dupain and Olive Cotton. But it is the photographs of Olive Cotton that are the wonder of this exhibition. Photographs such as Orchestration in light (1937, below), Sky submerged (c. 1937) and especially The way through the trees (1938, below) are just masterpieces of complex seeing. A sort of… mmmm … an intimate previsualisation where there are hints of Pictorialism – dappled light, moss on the trees – and yet there is a geometric form to the composition that marks it as definitively Modernist. As the wall text states, “this exceptional landscape appears at first glance like a classic Pictorialist view of the Australian bush but typical of Cotton’s best pictures, this landscape merges Pictorialism’s stylistic and formal codes with those of a cosmopolitan modernist sensibility. Cotton pays particular attention to the similarly angled tree trunks, as well as the all over pattern of the spotted gums and the dapples of light, not bound or hemmed in dogma, Cotton created a view of being completely immersed in the landscape.” The colour of the print, there are hints of pinks and greens and beiges. When was it taken and printed, it must have been an early one, 1938 … and then again the beautiful tonality of it. Wow!

As with all of her best work Cotton is constructing her environment – through music, through geometry, through light. Over the city (1940, below), the light over the city, the shadow of the city, the silhouette of the city in outline, followed by Grass at sundown (1939, below) shooting contre jour, into the light. In Max after surfing (1937, below) there is evidence of Cotton’s understanding of the play of form, of light, of shadow and the composition of the pictorial plane into triangles, horizontals and verticals. This creates a sense of mystery within the four walls of the photograph. As art historian Tim Bonyhady observes, it ‘is not just one of the most erotic Australian photographs, but possibly the first sexually charged Australian photograph by a woman of a man’. The sensuality and atmosphere of the Cotton’s are just gorgeous. Olive Cotton just has such a marvellous grasp of the construction of the picture plane using form, texture and shadow… and feeling. If had a choice I would take away most of the Cotton’s (laughs), because I think they are just amazing…”

There are so many great images in this exhibition, from both Cotton and Dupain, that is hard to know where to start. I haven’t even mentioned images such as Dupain’s sensual but commercial Jean with wire mesh (c. 1935, below), his seminal Street at Central (1939, below) with its raking light and abstraction, or Cotton’s most famous image Teacup ballet (1935, below). I could go on and on. The only disappointment with the exhibition is that, for the uninitiated, there is little to place both photographers works in the context of their time and place, other than a few The Home magazines in a couple of display cases and the wall text. There is little sense of what a tumultuous period this was in Australian history – between two world wars, during a depression, with the advent of modernity, freedom of movement through cars, White Australia policy in full swing, meat and four veg on the table, women’s place in the home, the rise of vitalism and the cult of the bronzed Aussie body and the worship of nature and the outdoors, mateship and the beach as a place of socialisation. But that is the nature of such a classic, hung “on the line” exhibition. It would have been great to see some large photographs, floor to ceiling, of the environment from which all these nearly contextless (as in a particular time and place) images emerged but this is a minor quibble. In the end, I restate that this is a stunning exhibition that is a must see for any aficionado of great Australian photography. Go see it before it closes.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,685

Many thankx to The Ian Potter Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation images © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art.

“I like few people … to go into a room of strangers is a chore for me … I can effect a relationship, but afterwards, I think: was it worth it?”

Max Dupain

“Looking at the work of these two great Australian photographers together is enlightening; they were often shooting the same subjects, or pursuing subjects and pictorial effects in similar ways. Rarely do we get to see two great Australian artists working side-by-side in this way. And while Max Dupain’s reputation might now stand well above most other Australian photographers, this exhibition shows that Olive Cotton had a significant role to play in his development as a photographer, and was in many ways his equal.”

Shaune Lakin

Gallery one

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain' at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing at left, Max Dupain's 'Bawley Point landscape' (1938) and at middle, Dupain's 'Untitled [Factory chimney stacks]', 1940 Installation view of the exhibition 'Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain' at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing at left, Max Dupain's 'Bawley Point landscape' (1938) and at middle, Dupain's 'Untitled [Factory chimney stacks]', 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/installation-h.jpg)

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing at left in the bottom image, Max Dupain’s Bawley Point landscape (1938) and at middle, Dupain’s Untitled [Factory chimney stacks], 1940

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing in the bottom image, Max Dupain’s famous Sunbaker (1937) at second right

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing in the bottom image Olive Cotton’s most famous photograph, Teacup ballet (1935) at left

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Installation view of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing Max Dupain’s Jean with wire mesh (c. 1935) at right

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Gallery two

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing in the bottom image, a cabinet with view of The Home magazine (April 1st 1933 right) which feature the photographs of Max Dupain

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Gallery three

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing in the bottom image, Max Dupain’s Street at Central (1939) left, followed by his Thin man (1936) and Olive Cotton’s Fashion shot, Cronulla sandhills (Max Dupain photographing model) (1937) at right

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Installation views of the exhibition Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne. Photos: © Marcus Bunyan, The National Gallery of Australia and The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Olive Cotton (1911-2003) and Max Dupain OBE (1911-1992) were pioneering modernist photographers. Cotton’s lifelong obsession with photography began at age eleven with the gift of a Kodak Box Brownie. She was a childhood friend of Dupain’s and in 1934 she joined his fledgling photographic studio, where she made her best-known work, Teacup Ballet, in about 1935. Throughout the 1930s, Dupain established his reputation with portraiture and advertising work and gained exposure in the lifestyle magazine The Home. Between 1939 and 1941, Dupain and Cotton were married and she photographed him often; her Max After Surfing is frequently cited as one of the most sensuous Australian portrait photographs. While Dupain was on service during World War II Cotton ran his studio, one of very few professional women photographers in Australia. Cotton remarried in 1944 and moved to her husband’s property near Cowra, New South Wales. Although busy with a farm, a family, and a teaching position at the local high school, Cotton continued to take photographs and opened a studio in Cowra in 1964. In the 1950s, Dupain turned increasingly to architectural photography, collaborating with architects and recording projects such as the construction of the Sydney Opera House. Dupain continued to operate his studio on Sydney’s Lower North Shore until he died at the age of 81. Cotton was in her seventies when her work again became the subject of attention. In 1983, she was awarded a Visual Arts Board grant to reprint negatives that she had taken over a period of forty years or more. The resulting retrospective exhibition in Sydney in 1985 drew critical acclaim and has since assured her reputation.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind

c. 1939

Gelatin silver photograph

PHOTOGRAPH NOT IN EXHIBITION

Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind appears to have been the only print Cotton made of this image. It was found in the late 1990s and has been shown only once, in an exhibition at the AGNSW in 2000 where it was also used on the catalogue cover. It was unusual for Cotton to print so large, yet it is entirely fitting that this monumental head and shoulder shot of a beautiful young woman should be presented in this way. The subject was a model on a fashion shoot at which Cotton was probably assisting. Cotton often took her own photographs while on such shoots and used them for her private portfolio. The photograph transcends portraiture, fashion and time to become a remarkable image of harmony with the elements.

Cotton took the title for this photograph from an 1895 poem by English poet Laurence Binyon, ‘O summer sun’:

O summer sun, O moving trees!

O cheerful human noise, O busy glittering street!

What hour shall Fate in all the future find,

Or what delights, ever to equal these:

Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind,

Only to be alive, and feel that life is sweet?1

A photographer whose work straddles pictorialism, modernism and documentary, Cotton maintained an independent vision throughout her working life, based on the close observation of nature. Her understanding of the medium of photography was not to do with capture, but rather ‘drawing with light’.

1. 1915, ‘Poems of today’, English Association, London p 96

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Max

c. 1935

Gelatin silver photograph

14.8 x 14.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1998

In this highly abstracted portrait, Cotton seems to present Dupain as an athlete – perhaps, with his strangely extended arms, a hammer thrower, in an image that predates by at least two years Dupain’s own photographs of athletes outdoors. It is likely that Cotton photographed her friend in this way because of the graphic pictorial effect she wished to achieve. Cotton exploits the shape of the Rolleiflex camera’s square-format film: Dupain’s body cuts across the right-hand corner of the picture, from which his overstretched forearms (the shape and tone of which were the result of much dodging and burning in the darkroom) create a diagonal oblique angle that is classically modernist. A similar conflation of diagonal lines, which was common to the ways that modern life in Australia at the time was represented in advertising and architectural photography, can also be seen in pictures such as Surf’s edge and Teacup ballet.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Max Dupain put his lack of clannishness down to a temperament which inclined to the stoic and an early life as an only child. He relished the solitude of his darkroom, familiar places and routines and the early morning calm of Sydney Harbour, where he rowed his scull until prevented by ill health in the early 1990s. He was not a joiner or follower of teams; he was republican in politics and agnostic. Philosophically, Dupain mixed rationalism and a less defined alliance with the passionate exhortation to live directly in one’s environment, body and heart. This philosophy was espoused by poets and writers such as D.H Lawrence, from the movement known in the 1920s and 1930s as Vitalism.

Although he acknowledged that he was a bit of a loner by temperament, portraiture was a significant part of Max Dupain’s personal and professional work. He included some dozen or so portraits in his selection for his 1948 monograph, fifty plates showing ‘my best work since 1935’. Dupain’s images, including many portraits especially of the 1930s to 1960s, have stamped the public image of this era of rapid progress and increasing cultural sophistication in Australia. Portraiture was at the top stratum of Dupain’s first three decades of work but volume decreased markedly from the 1960s, when Max Dupain and Associates, his business, began to specialise in architectural and industrial commissions.

‘Vintage Max’ by Gael Newton, 1 June 2003

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Sunbaker

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

37.7 x 43.2cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

The photographer’s shadow (Olive Cotton and Max Dupain)

c. 1935

Gelatin silver photograph

16.6 x 15.2cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

The sleeper

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

29.2 x 25.0cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1987

The sleeper 1939, Olive Cotton’s graceful study of her friend Olga Sharp resting while on a bush picnic, made around the same time as Max Dupain’s Sunbaker, presents a different take upon the enjoyment of life in Australia. The woman is relaxed, nestled within the environment. The mood is one of secluded reverie.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

![Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled [Olive Cotton in Wheat Fields]' Nd (probably late 1930s) Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled [Olive Cotton in Wheat Fields]' Nd (probably late 1930s)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/dupain-olive-cotton-in-wheat-fields-nd-web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Untitled [Olive Cotton in Wheat Fields]

Nd (probably late 1930s)

Gelatin silver photograph

PHOTOGRAPH NOT IN EXHIBITION

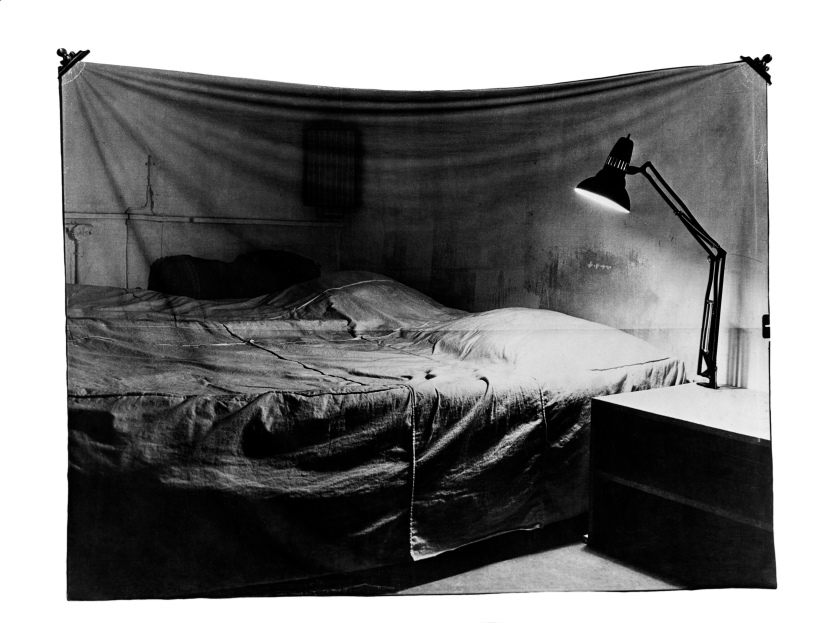

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Max

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Cotton shot this portrait of fellow Australian photographer, Max Dupain during their brief marriage at their home in Longueville on Sydney’s lower north shore. Dupain is captured affectionately in the portrait, represented as at once casual through pose and, as industrious on account of his rolled up sleeves and the Rolleiflex TLR camera which hangs from his neck. It is indicative of the combination of a working and personal relationship Cotton and Dupain shared during the late 1930s when they operated a commercial studio together. The couple separated in 1941 but Cotton went on to manage the Dupain Studio while Max was away serving as a camouflage officer during the Second World War 1.

1. Ennis H 2005, ‘Olive Cotton: photographer’, National Library of Australia, p. 6

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Max after surfing

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 2006

This intimate study of Dupain, who Cotton was romantically involved with at the time, first appeared in the mid-1990s; Cotton did not include it in her reassessment of her oeuvre in the mid-1980s that involved making prints of her best images. For many commentators, this remains a radical image in the history of Australian photography. For the art historian Tim Bonyhady, it ‘is not just one of the most erotic Australian photographs, but possibly the first sexually charged Australian photograph by a woman of a man’. This is the only known vintage print of the image, which inexplicably carries the signature and a message from the fashion photographer George Hoyningen‑Huene, who visited Sydney in December 1937 and spent time with Dupain. It suggests perhaps that Hoyningen-Huene was present when Cotton made the print.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Max after surfing is a portrait of Dupain taken in 1939, around the time of their brief marriage. While the photograph was taken indoors, the sharply delineated contrast and the dramatic interplay between light and shade evoke harsh sunlight. The work is loaded with suggestion and emotional intimacy. As art historian and curator Helen Ennis noted in 2000, the close vantage point and the tension between visible form and dense shadow ‘creates a space for erotic imaginings’.

A photographer whose work straddles Pictorialism, modernism and documentary, Cotton maintained an independent vision throughout her working life, based on the close observation of nature. Her understanding of the medium of photography was not to do with capture, but rather ‘drawing with light’.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Jean with wire mesh

c. 1935

Gelatin silver photograph

46.0 x 34.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 2006

This portrait of Jean Lorraine, a close friend of Cotton, was one of many taken of her by Cotton and Dupain. This photograph is notable for its technical virtuosity – Dupain’s control of the variegated light across Jean’s body, beautifully lyrical and sensuous, is masterful. It also reflects Dupain’s active interest in the work of Man Ray, whose earlier Shadow patterns on Lee Miller’s torso (1930) was no doubt an influence. Like Man Ray’s image of his lover, Dupain’s portrait of Jean is also notable for its eroticism. While Dupain might have argued that this photograph was a study of light falling on surfaces, the light and shade take particular pleasure in the form of Jean’s naked torso. This eroticism has been underplayed throughout the history of the picture, not surprising given the nature of the relationships involved: when it was published in The Home in February 1936, Jean with wire mesh was known simply as a Photographic study. Dupain printed at least two versions of this shot, another with Jean’s eyes open.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Girl with mirror

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

Image 31.7 x 29.9cm

Sheet 32.6 x 30.6cm

Purchased 1987

The photographs Cotton took while attending Dupain’s fashion shoots often focussed on the graphic effects created by light rather than fashion or the dynamics of the shoot itself. Cotton’s role as assistant left her free to explore personal interests, without the imperative of getting a shot for the assignment. This image of a model attending to her make-up, seemingly absorbed in her own image, is primarily concerned with the patterns created by light falling on sand dunes and the way they contrast with the decorative print of her clothing. It is notable that the image we see in the mirror is not the model’s face, but the patterns created by light hitting the sand. As Cotton later remembered, ‘I took it mostly because I really liked the pattern in the sand and the contrasting pattern in the left-hand corner’, which includes a series of diagonal shadows cast by Dupain’s tripod.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

The floater

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia

Purchased 1976

Two versions of this image of a woman floating in water were printed by Dupain, so like Sunbaker it held particular interest for him. It acknowledges one of the great moments in avant-garde photography, André Kertész’s iconic study of underwater distortion Underwater swimmer (1917). As with Kertész, Dupain’s interest was with the visual effects created by light hitting the water and the impact of this on the contours of the swimmer. In his personal copy of the anthology Modern Photography (1931), Dupain highlighted the writer G.H. Saxon Mills’ claim that photography’s value existed in both its capacity to record the world and the optical effects it found or created – ‘its … symphony of forms and textures.’

Wall text

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Fashion shot, Cronulla sandhills (Max Dupain photographing model)

1937

Cronulla, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Gelatin silver photograph

Image 30.4 x 38.5cm

Sheet 40.2 x 48.7cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1988

As the studio assistant, Cotton accompanied Dupain on fashion shoots to attend to models, doing their make-up and helping with costume changes. She often used these opportunities to take her own photographs, including this wonderful image of Dupain photographing the model Noreen Hallard for David Jones. As well as producing a striking image of Dupain and Hallard at work, Cotton was interested in the landscape in which they operated, paying particular attention to the pattern created by their footsteps in the sand.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

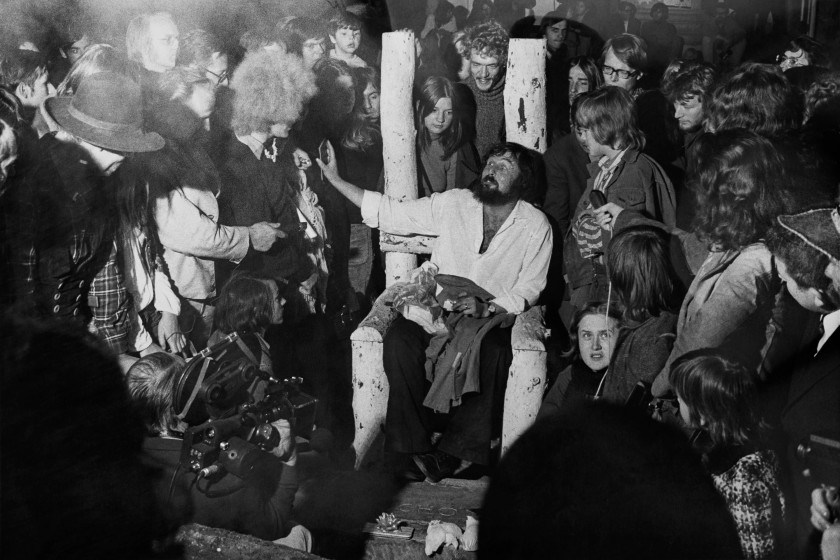

Olive Cotton and Max Dupain are key figures in Australian visual culture. They shared a long and close personal and professional relationship. This exhibition looks at their work made between 1934 and 1945, the period of their professional association; this was an exciting period of experimentation and growth in Australian photography, and Cotton and Dupain were at the centre of these developments.

This is the first exhibition to look at the work of these two photographers as they shared their lives, studio and professional practice. Looking at their work together is instructive; they were often shooting the same subjects, or pursuing subjects and pictorial effects in similar ways. Comparisons articulate and make apparent Dupain’s more structured – even abstracted – approach to art and to the world; similarly, comparisons highlight Cotton’s more immersive relationship to place, with a particularly deep and instinctual love of light and its ephemeral effects.

This exhibition focuses on the key period in each of their careers, when they made many of their most memorable images. Keenly aware of international developments in photography, Cotton and Dupain experimented with the forms and strategies of modernist photography, especially Surrealism and the Bauhaus, and drew upon the sophisticated lighting and compositions of contemporary advertising and Hollywood glamour photography.

They brought to these influences their own, close association with the rich context of Australian life and culture during the 1930s and ’40s. Their achievement can be characterised, borrowing terms they used in discussions of their work, as the development of a ‘contemporary Australian photography’: a modern photographic practice that reflected their own, very particular relationships to the world and to each other.

Lives

Cotton and Dupain’s friendship stretched back to childhood summers spent at Newport Beach, NSW, where their families spent summer holidays. They were both given their first cameras – Kodak Box Brownies – by relatives as young teenagers, and spent days together wandering around taking photographs. They shared a similar commitment to photography as teenagers and young adults: both made and published or exhibited photographs while at school, and in 1929 they became members of the Photographic Society of New South Wales. But their approach to achieving the ‘professional life’ of a photographer took different paths: Dupain undertook a formal apprenticeship with the Pictorialist master Cecil Bostock between 1930-33, while Cotton studied arts at Sydney University with the idea of becoming a teacher and photographed after hours.

Cotton and Dupain became romantically involved in 1928 and married in 1939; they separated in 1941 and eventually divorced in 1944. In spite of these personal vicissitudes, Cotton and Dupain remained professionally connected. Cotton managed the Dupain studio from late 1941-45, while he worked with the Department of Home Security’s Camouflage Unit during the Second World War. On his return, Cotton left Sydney and spent the rest of her life in relative isolation near Cowra, NSW, where she raised her family of two with husband Ross McInerney and, between 1964 and 1983, operated a small studio. And while Dupain returned from the war to develop his reputation and significance as Australia’s most recognised twentieth-century photographer, his work was deeply affected by his experience of the war and took on a completely different complexion to his work from the previous decade.

Studio

In 1934, Dupain opened a studio in a rented room at 24 Bond Street, Sydney; Cotton joined him as his assistant soon after. By 1936, the Dupain studio’s business had expanded to the extent that it moved into larger premises in the same building, before relocating in early 1941 to a whole floor of a building at 49 Clarence Street.

Their positions at the Dupain studio were clearly defined – he was the photographer, she the studio assistant. Even so, Cotton and Dupain each maintained distinct but in some ways closely aligned practices, both in and out of the studio. Cotton did not tend to take photographs commercially until after she took over the management of the Dupain studio in late 1941, when photographs were circulated in her name. Before then, she made use of the studio’s equipment after hours, including Dupain’s large Thornton Pickard camera; her work was exhibited and published on occasion, both locally and internationally.

At the same time, Dupain’s photographs became increasingly widely-seen and influential. Sydney Ure Smith’s iconic monthly magazine The Home regularly published Dupain’s portraits, documentary work, social photographs (often actually taken by Cotton), and fashion and product photographs made for clients such as David Jones. When Dupain went to war, the studio continued to operate successfully under Cotton’s management. While some long-standing clients such as David Jones took their business elsewhere, Cotton took some of her most important pictures in the early 1940s, and her increasing confidence at this time can be identified across images of the city, industry and labour.

Dialogue

Cotton and Dupain were active members of Sydney’s network of young artists and photographers, of which the Dupain studio was a centre. Along with their contemporaries, including figures like Geoffrey Powell, Damien Parer and Lawrence Le Guay, they staked a claim for photography as a vital part of contemporary culture, exhibiting photographs alongside other artworks at venues like Sydney’s David Jones Gallery.

Their networks included members of Sydney’s progressive architectural, design, publishing and advertising communities, with whom they often collaborated. The threads of influence within this complex network of making, exhibiting, publishing and commissions were intricate. It is possible, for example, to see Dupain’s strong visual style affect those around him. His interest in surrealist style, which really took hold in 1935, can be identified in work by other, often lesser photographers working at the time, and indeed in the design of The Home, which published his work in editorial and advertisements. There were also times when Cotton indicated certain directions for Dupain. For example, her images of bodies outdoors, which cleverly pulled together classical and modernist motifs, predate similar images by Dupain.

It is clear also that Cotton and Dupain were engaging in dialogue within their own work. Their shared interest in photographing form, texture and shadow is seen across many pictures throughout the mid- to late 1930s. Their pictures also engage critically with photography as a medium, in images that draw attention to the photograph as a double of its subject, and in pictures that seem to play with photograph’s stillness. As Dupain later remembered, together they ‘shared the problems of photography’.

Contemporary Australian Photography

What were ‘the problems of photography’ that Dupain and Cotton sought to settle? In the most straightforward sense, they involved the assumption that Australian photographers were yet to completely embrace or realise the medium’s potential, which rested in careful attention to its aesthetic possibilities, recognition of its mechanical origins, and negotiation of the particular way the medium engaged notions of objectivity and subjectivity. Their solution to these problems involved a progressive photographic practice that intended to release photography from the shackles of history and orthodoxy, and to revel in photography’s great capacity to make sense of the relations of light, texture and form as they exist in the present.

Cotton’s and Dupain’s solution to ‘the problems of photography’ was to make work that made a feature of the medium’s modernity, and the strange way that mechanics, physics and aesthetics come together in modern photography to look at the world and to find beauty in it. They did this in a way that remained firmly footed in their own, very particular place in the world and history. In terms of style, their solution integrated legacies of Pictorialism – especially its interest in the atmospheric effects found in landscape – with a range of other, often competing modes and styles: a modernist concern with line, form and space; documentary photography’s interest in realism and ‘the living moment’; and the pictorial and formal attributes of commercial photography.

It is possible that, for the first time, Australian photography found in the work of Cotton and Dupain a contemporary expression: a photographic practice that emerged from, responded to and expressed the mood, ambitions and sensibility of its time.

Press release from The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Street at Central

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

45.6 x 37.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1976

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Street at Central

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

45.6 x 37.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1976

Two different versions of this photograph. Notice the different cropping and colour of each image, and how it adds emphasis to the light and to the shadows of the people.

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Teacup ballet

1935

Gelatin silver photograph

37.5 x 29.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1983

‘This picture evolved after I had bought some inexpensive cups and saucers from Woolworths for our studio coffee breaks to replace our rather worn old mugs. The angular handles reminded me of arms akimbo, and that led to the idea of making a photograph to express a dance theme.

When the day’s work was over I tried several arrangements of the cups and saucers to convey this idea, without success, until I used a spotlight and realised how important the shadows were. Using the studio camera, which had a 6 ½ x 4 ½ inch ground glass focusing screen, I moved the cups about until they and their shadows made a ballet-like composition and then photographed them on a cut film negative. The title of the photograph suggested itself.

This was my first photograph to be shown overseas, being exhibited, to my delight, in the London Salon of Photography in 1935.’ Olive Cotton 1995 1

Olive Cotton and Max Dupain were childhood friends and, although she graduated in English and mathematics from the University of Sydney in 1934, her interest in photography led her to work in Dupain’s studio from this year. Cotton was employed as a photographer’s assistant in the studio, however she worked assiduously on her own work and continued to exhibit in photography salon exhibitions. Tea cup ballet is one of Cotton’s most well-known photographs and yet it is somewhat eccentric to her main practice, being at first glance typically modernist with its dramatic lighting and angular shapes. Her longstanding interest in organic forms provides a deeper reading. The abstraction of form by the lighting and the placement of the cups and saucers enables the relationship to dancers on a stage to become clear.

1. Ennis H 1995, ‘Olive Cotton: photographer’, National Library of Australia, Canberra p. 25

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Among Cotton’s most famous photographs, Teacup ballet has very humble origins. It was taken after hours in the Dupain studio and used a set of cheap cups and saucers Cotton had earlier bought from a Woolworths store for use around the studio. As she later recounted: ‘Their angular handles suggested to me the position of “arms akimbo” and that led to the idea of a dance pattern’. The picture uses a range of formal devices that became common to Cotton’s work, especially the strong backlighting used to create dramatic tonal contrasts and shadows. The picture achieved instant success, and was selected for exhibition in the London Salon of Photography for 1935.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Shasta daisies

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1987

Celebrated Australian photographer Olive Cotton was given her first Box Brownie by her family for her eleventh birthday (1922) and continued to experiment with taking and developing pictures throughout the 1920s. By the early 1930s Cotton had mastered the Pictorialist style so popular at the time and was on her way to establishing her own approach which also incorporated Modernist principles. The recurrent themes of landscape and plant-life are important to the photographer’s approach, which photography scholar Helen Ennis describes as Cotton’s concern for the ‘potential for pattern-making’.

Shasta daisies is an interesting and rare combination of natural form and a highly-constructed scenario, the flowers having been photographed in Cotton’s studio and carefully arranged for the camera. Cotton, in the 1995 book, wrote of the photograph: “I chose to photograph these in the studio because out of doors I would have had less control of the lighting and background. I examined the composition very carefully through the studio camera’s large ground glass focussing screen and – the view from the camera’s position being slightly different to my own – made as many rearrangements to the flowers as seemed necessary. I then used (apart from a background light) one source of light to try and convey a feeling of outdoors.” Shasta daisies is important within Cotton’s oeuvre for uniting her interest in plants in their natural ‘outdoors’ environment with her enquiry into photographic form and space.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Homage to D.H. Lawrence

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

45.8 x 33.9cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

Dupain admired vitalist philosophies, which argued that modern identity had become fragmented and asserted the importance of the integration of body and emotion, of sensual and emotional experience. He was attracted to the work of British writer D.H. Lawrence, especially his insistence on the ‘thingness’ of things as a way of embodying a properly integrated mind and body. This photograph uses surrealist juxtaposition to draw together a copy of Lawrence’s Selected poems, a flywheel (representing the modern world) and a classical bust, recalling the idealised relationship of natural and sensual worlds in ancient Greece and Rome. Other images incorporating classical busts appeared in the pages of the Modern Photography annuals, but Dupain makes them his own, lifted above mere pastiche.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911 – 2003)

Orchestration in light

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

Image 24.1 x 27.4cm

Sheet 25.4 x 28.2cm

Purchased with assistance from the Helen Ennis Fund

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Cotton took this landscape early one morning at Wullumbi Gorge in the New England tablelands, during a camping trip with Dupain. It is remarkable for both the way the light transforms the landscape into quivering energy and the way Cotton makes sense of that enigmatic experience in pictorial form. As its title suggests, the photograph recalled for Cotton – who trained as a musician as a girl – a musical composition, particularly ‘the beautiful graduation in tone going from a bass tone to a high treble at the top of the picture’.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

The patterned road

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

24.6 x 28.8cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1983

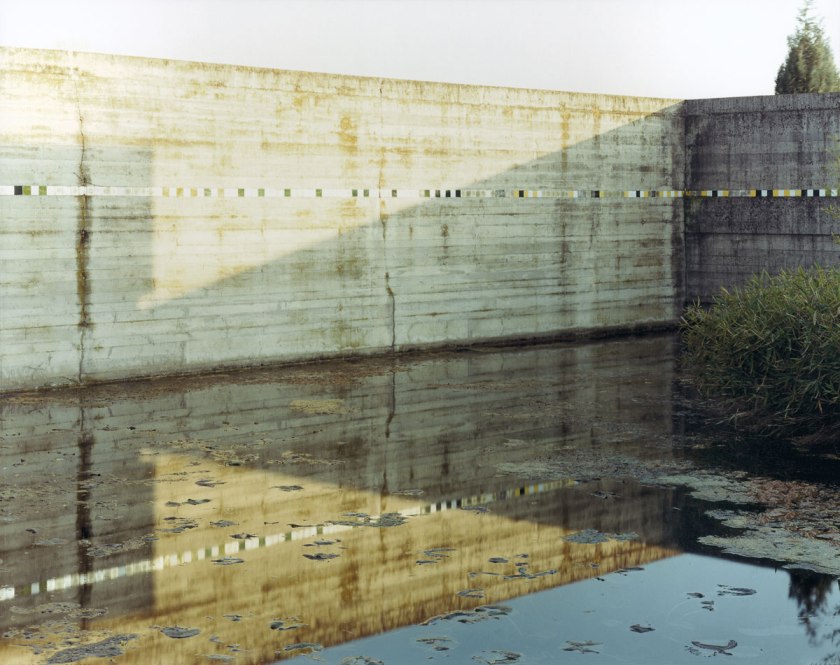

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Bawley Point landscape

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

29 x 26.6cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

This landscape, one of many taken by Dupain on the south coast of New South Wales, was made in the same year as Cotton’s similar study of shadow and landscape, The patterned road (above). These two landscapes share an interest in what Dupain later termed ‘passing movement and changing form’. Although Dupain rarely published or circulated his landscapes at this time, pictures such as Bawley Point landscape certainly relate to a broad range of other images, perhaps most notably still lifes and nudes, that articulated an Australian modernist photography through the interplay of light passing through openings. These images find monumental stillness in movement and strong shadows, which quite literally ‘double’ their subject.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Over the city

1940

Gelatin silver photograph

32.2 x 30.3cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1987

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Grass at sundown

1939

Gelatin silver photograph

Primary Insc: Signed and dated l.l. pencil, “Olive Cotton ’39”. Titled l.r. pencil, “Grass at sundown”.

Printed image 28.9 x 30.8cm

Sheet 30.0 x 31.6cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the artist 1987

Max Dupain (Australia, 1911-1992)

Design – suburbia

1933

Gelatin silver photograph

29.4 x 23.6cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1982

This early image proudly displays the influence of the work of pictorialist photographers that Dupain knew well, most notably the Sydney-based photographer, Harold Cazneaux. At the time Dupain made this image, he was serving an apprenticeship in the commercial studio of Cecil Bostock, a Pictorialist and founding member with Cazneaux of the Sydney Camera Circle in 1916. Dupain’s interest in the pictorial effects created by light passing through apertures (here, the posts and beams of a suburban fence) seems to remember similar images of light streaming through blinds and pergolas by Cazneaux, who Dupain called ‘the father of modern Australian photography’. The fascination with capturing light as it passes through openings will stay with Dupain throughout his life, though the focus will sharpen as he moves away from the diffused effects favoured by art photographers in the early decades of the century.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Max Dupain (Australia, 1911-1992)

Still life

1935

Gelatin silver photograph

29.0 x 20.8cm

Purchased 1982

While the subject of this photograph seems to be a simple, lidded pail (which featured in a number of Dupain’s still lifes) seen in morning light, it is actually an exercise in abstraction. Of most interest to Dupain is the complex network of diagonal lines created by light, shadow and timber boards. The picture reflects the pleasure Dupain took in the pictorial effects created by light (he was fond of quoting the Belgian photographer Léonard Misonne’s dictum, ‘the subject is nothing, light is everything’), and at the same time expresses the fundamental principle upon which his photographic practice was always based. While the image of light passing through apertures is an analogy for the way the camera operates, the still life also embodies photography’s expressive potential. As Dupain later stated, ‘with still-life you can arrange or rearrange or do what you like, it becomes a very, very personal exercise that you have total control over’.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Pyrmont silos

1935

Gelatin silver photograph

Printed image 25.2 x 19.2cm

Sheet 31.2 x 26.2cm

Mount 42.4 x 32.0

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1976

Max Dupain was the first Australian photographer to embrace Modernism, and took a number of photographs of Pyrmont silos in the 1930s. There were no skyscrapers in Sydney until the late 1930s so the silos, Walter Burley Griffin’s incinerators and the Sydney Harbour Bridge were the major points of reference for those interested in depicting modern expressions of engineering and industrial power. Olive Cotton’s Drainpipes 1937 shows the precisely formed circles and curves of the pipes, interspersed with slivers of light and long shadows.

In almost text-book fashion, this image reflects Dupain’s assimilation of the aesthetics of contemporary European photography, which he encountered in publications such as the Das Deutsche Lichtbild [The German photograph] and Modern Photography annuals, the 1932 edition of which was edited by Man Ray. While Dupain’s relationship to the contemporary world was complicated, he nonetheless advocated for the latest photographic trends out of Europe and America, and for photographing modern, industrial subjects; as he asserted in 1938, ‘great art has always been contemporary in spirit’. Writing in 1975 about this image for Dupain’s retrospective at the Australian Centre for Photography, fellow photographer David Moore, who had worked with Dupain in the late 1940s, saw it as a turning point in Dupain’s career, believing that here ‘his awareness of the strength of industrial forms was confirmed with confident authority … From this moment any return to sentimental Pictorialism was precluded’.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Pyrmont silos is one of a number of photographs that Dupain took of these constructions in the 1930s. In all cases Dupain examined the silos from a modernist perspective, emphasising their monumentality from low viewpoints under a bright cloudless sky. Additionally, his use of strong shadows to emphasise the forms of the silos and the lack of human figures celebrates the built structure as well as providing no sense of scale. Another photograph by Dupain in the AGNSW collection was taken through a car windscreen so that the machinery of transport merges explicitly with industrialisation into a complex hard-edge image of views and mirror reflections. There were no skyscrapers in Sydney until the late 1930s so the silos, Walter Burley Griffin’s incinerators and the Sydney Harbour Bridge were the major points of reference for those interested in depicting modern expressions of engineering and industrial power.

Dupain was the first Australian photographer to embrace modernism. One of his photographs of the silos was roundly criticised when shown to the New South Wales Photographic Society but Dupain forged on regardless with his reading, thinking and experimentation. Some Australian painting and writing had embraced modernist principles in the 1920s, but as late as 1938 Dupain was writing to the Sydney Morning Herald:

“Great art has always been contemporary in spirit. Today we feel the surge of aesthetic exploration along abstract lines, the social economic order impinging itself on art, the repudiation of the ‘truth to nature criterion’ … We sadly need the creative courage of Man Ray, the original thought of Moholy-Nagy, and the dynamic realism of Edouard [sic] Steichen.”1

1. Dupain, M 1938, “Letter to the editor,” in Sydney Morning Herald, 30 March

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website © Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Backyard, Forster, New South Wales

1940

Gelatin silver photograph

30.5 x 30.5cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1983

This highly formal view of the backyard of a hotel in the coastal town of Forster embodies Dupain’s sense of Australian modernist photography. The picture’s frontalism and overriding use of horizontals and verticals acknowledge that the camera faced its subject face-to-face and that the view has been consciously framed. But as the title of the photograph makes clear, it is also a record of a particular place. In his personal copy of G.H. Saxon Mills’ essay ‘Modern photography’, which greatly assisted Dupain to conceptualise his own sense of a contemporary photographic practice, Dupain highlighted and annotated with a question mark the following statement: ‘”modern” photography means photography whose aim is partly or wholly aesthetic, as opposed to photography which is merely documentary or representational.’ Dupain believed that both were possible within the same frame.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

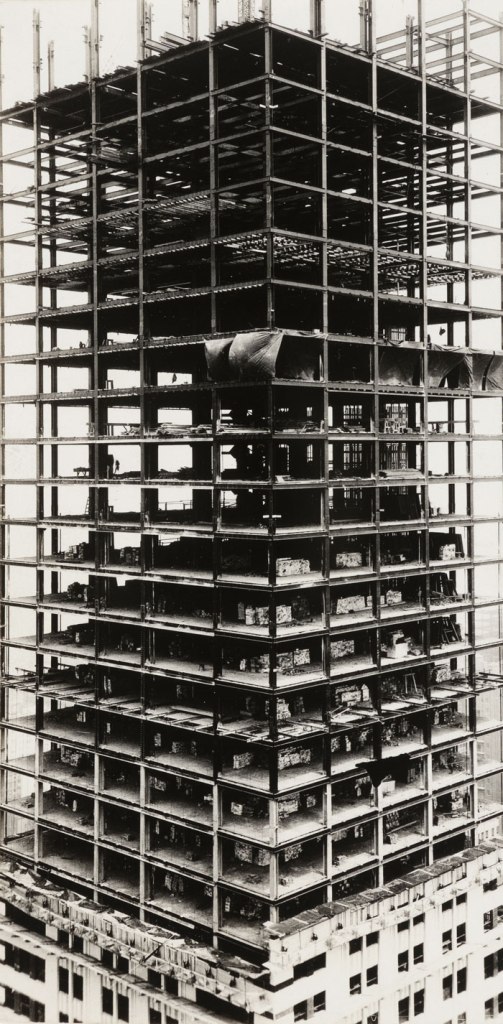

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

[Factory chimney stacks]

1940

Gelatin silver photograph

49.0 x 38.4cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1983

Dupain highlighted the writer G.H. Saxon Mills’ claim that photography’s value existed in both its capacity to record the world and the optical effects it found or created – ‘its … symphony of forms and textures.’

These factory chimney stacks are reduced to their most simple and direct form, which is shown free of any distraction. As Dupain noted, borrowing from the great American architectural historian Lewis Mumford, the ‘mission of the photograph is to clarify the subject’. The choice of subject matter was influenced by an essay by the English journalist, G.H. Saxon Mills, written in 1931 and read by Dupain soon after: ‘(photography) belongs to the new age … it is part and parcel of the terrific and thrilling panorama opening out before us today – of clean concrete buildings, steel radio masts, and the wings of the air line. But its beauty is only for those who themselves are aware of the ‘zeitgeist’ – who belong consciously and proudly to this age, and have not their eyes forever wistfully fixed on the past.’

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

The way through the trees

1938

Gelatin silver photograph

29.6 x 29.0cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the artist 1987

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

An old country homestead, Western Australia

1946

Gelatin silver photograph

PHOTOGRAPH NOT IN EXHIBITION

The Ian Potter Museum of Art

The University of Melbourne,

Swanston Street (between Elgin and Faraday Streets)

Parkville, Melbourne, Victoria

Phone: +61 3 8344 5148

Opening hours:

Closed for redevelopment

The Ian Potter Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Doges' Palace and the Piazzetta]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Doges' Palace and the Piazzetta]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/3-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [St Mark's Basilica]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [St Mark's Basilica]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/5-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Bridge of Sighs]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Bridge of Sighs]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/9-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Courtyard of the Doge's Palace looking towards the Torricella]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Courtyard of the Doge's Palace looking towards the Torricella]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/10-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. '230 [Interior of the Doges Palace]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. '230 [Interior of the Doges Palace]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/14-230-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Entry to the presbytery of St Mark's Basilica]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Entry to the presbytery of St Mark's Basilica]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/20-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Bridge of Sighs]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Bridge of Sighs]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/21-untitled.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Torre del Orologio]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Torre del Orologio]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/24-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Doge's Palace]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [The Doge's Palace]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/25-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Statue of King Vittorio Emanuel II by the sculptor Ettore Ferrari 1887]' c. 1887 Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia. 'Untitled [Statue of King Vittorio Emanuel II by the sculptor Ettore Ferrari 1887]' c. 1887](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/28-untitled.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia 'Untitled [Rialto Bridge]' 1880s Fratelli Gajo – Piazza S.Marco 139 – Venezia 'Untitled [Rialto Bridge]' 1880s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/30-untitled.jpg?w=840)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain' at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing at left, Max Dupain's 'Bawley Point landscape' (1938) and at middle, Dupain's 'Untitled [Factory chimney stacks]', 1940 Installation view of the exhibition 'Max and Olive: The photographic life of Olive Cotton and Max Dupain' at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne showing at left, Max Dupain's 'Bawley Point landscape' (1938) and at middle, Dupain's 'Untitled [Factory chimney stacks]', 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/installation-h.jpg)

![Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled [Olive Cotton in Wheat Fields]' Nd (probably late 1930s) Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992) 'Untitled [Olive Cotton in Wheat Fields]' Nd (probably late 1930s)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/dupain-olive-cotton-in-wheat-fields-nd-web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Zoë Croggon. 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [7] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014 Zoë Croggon. 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [7] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/installation-h.jpg?w=840&h=827)

![Zoë Croggon. 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [18] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014 Zoë Croggon. 'Comalco Aluminium Used in the Construction of the National Gallery of Victoria [18] (after Wolfgang Sievers)' 2014](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/installation-i.jpg?w=710&h=1024)

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857-1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atgets-work-room-web1.jpg?w=840&h=1012)

![Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail) Eugène Atget (French, Libourne 1857–1927 Paris) 'Untitled [Atget's Work Room with Contact Printing Frames]' c. 1910 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/atget-workroom-detail-web.jpg?w=840&h=525)

![Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849 Marie-Charles-Isidore Choiselat (French, 1815-1858) Stanislas Ratel (French, 1824-1904) 'Untitled [The Pavillon de Flore and the Tuileries Gardens]' 1849](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/the-pavillon-de-flore-web.jpg?w=840&h=680)

![Edward J. Steichen (American (born Luxembourg), Bivange 1879-1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920 Edward J. Steichen (American (born Luxembourg), Bivange 1879-1973 West Redding, Connecticut) 'Untitled [Brancusi's Studio]' c. 1920](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/edward_steichen_brancusis_studio_1920-web.jpg?w=816&h=1024)

You must be logged in to post a comment.