Exhibition dates: 17th October 2023 – 21st January 2024

Benjamin Brecknell Turner (English, 1815-1894)

North Side of Quadrangle, Arundel Castle

1852-1854

Negative photograph on paper

29.7 x 39.6cm

BnF, department of Prints and Photography, RES PHOTO EI-6-BOITE FOL B (n° 3)

Gift of André and Marie-Thérèse Jammes, 1960

What a lovely exhibition to start the year 2024 on Art Blart.

My favourite photographs in the posting: three beautiful fashion photographs by Frères Séeberger; a stunning late Atget Parc de Sceaux, Duchess Alley (between 1925 and 1927, below) in which you can feel the crispness in the air of the early winter morning; and the glorious seascapes of Gustave Le Gray, probably the best (and most atmospheric) photographer of the sea in all time.

In this posting we observe how black and white photographs are never just black and white but full of different hues and colours. These colour variations tell us a lot about the perception of the image.

As the exhibition text notes: “The strength of the blacks and whites, the variations of hues influence our perception of the image: the more contrasted it is, the more readable it is for our eye saturated with absolute blacks and whites; the more nuanced it is, the more sensitive the distance of time becomes.”

As we enter a new year, another year further away from the origin of the light captured in these photographs, the sensitivity of early photographers and their ability to displace time continues to entrance the viewer.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Noir & Blanc: Une esthétique de la photographie

Black and white is inseparable from the history of photography: its developments, from the end of the 19th century to today, have revealed its plastic force. While the use of colour intensified from the 1970s, black and white reinvented itself as a means of assertive aesthetic expression emphasising graphics and material. Black and white photography remains less expensive and simpler, but its persistence to this day can be explained above all by the fact that it has come to embody the very essence of photography. It appears to carry a universal, timeless, even memorial dimension, where colour would be the sole translation of the contemporary world.

The National Library of France holds one of the richest photographic collections in the world with some six million prints, these are particularly representative of this abundant history of black and white photography.

Benjamin Brecknell Turner (English, 1815-1894)

Arbre le long d’une clotûre (Tree along a fence)

1852-1854

Negative photograph on paper

23.5 x 27.3cm

BnF, department of Prints and Photography, RES PHOTO EI-6-BOITE FOL B (n° 3)

Gift of André and Marie-Thérèse Jammes, 1960

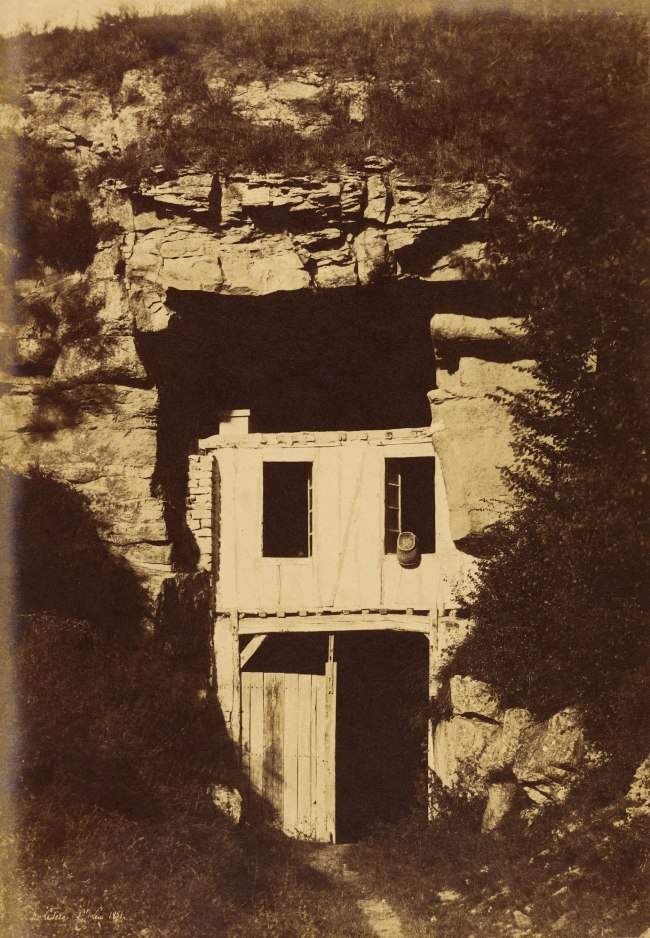

Photography on paper, with its speed and precision, revolutionised image production in the mid-19th century. The prerequisite is the production of a negative then of the same size as the print. The first negatives are on paper. Reversing the values of blacks and whites, they offer an unknown vision of the world. These oppositions, inverted or not, are the basis of the aesthetics of photography.

One of the earliest British amateur photographers, Benjamin Brecknell Turner (1815-1894) was experimenting with photography barely ten years after the invention of the medium. He exhibited widely during his lifetime and is best known for his beautiful photographs of 19th-century England, picturesque ruins and rural scenes.

A founder member of the Photographic Society of London, Turner contributed to the rapid technical and aesthetic development of photography in the 1850s. Our collection includes a unique album compiled by Turner, ‘Photographic Views from Nature’, containing some of the earliest photographs made in and around the counties of Worcestershire, Surrey, Sussex, Kent and Yorkshire, alongside the radical modern architecture of the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park.

Text from the V&A website

The origins of black and white

Before the invention of colour photography by the Lumière brothers in 1903, one might believe that all photography was black and white. The reality is more complex: the early days were more those of a varied range of values where pure blacks and whites were the exception and so-called sepia tones were the most common. The negative / positive process patented by the Englishman Fox Talbot in 1841 makes it possible to multiply the prints on paper and therefore to vary the shades.

Certain subjects play on oppositions: the mountain views of the Bisson brothers, the Great Wave by Gustave Le Gray, the portraits of the prolific amateur Blancard.

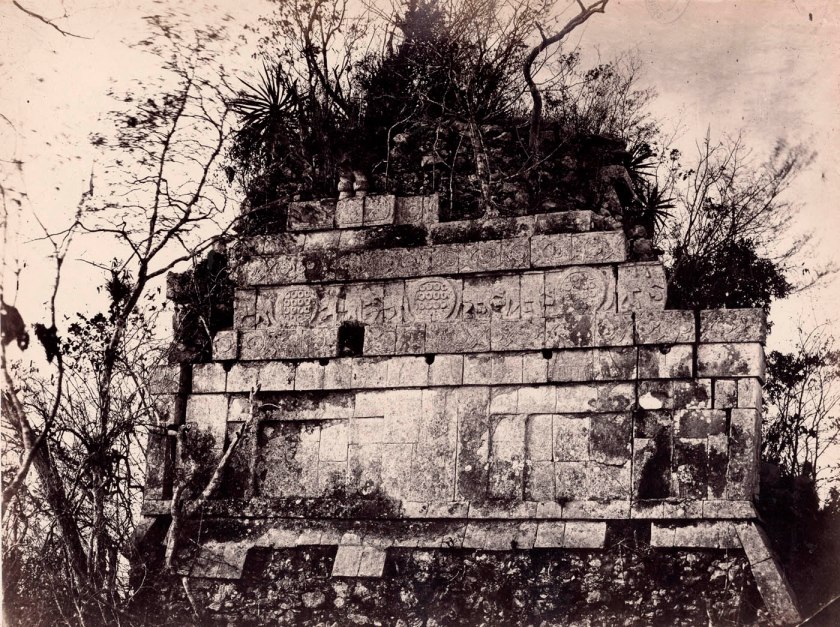

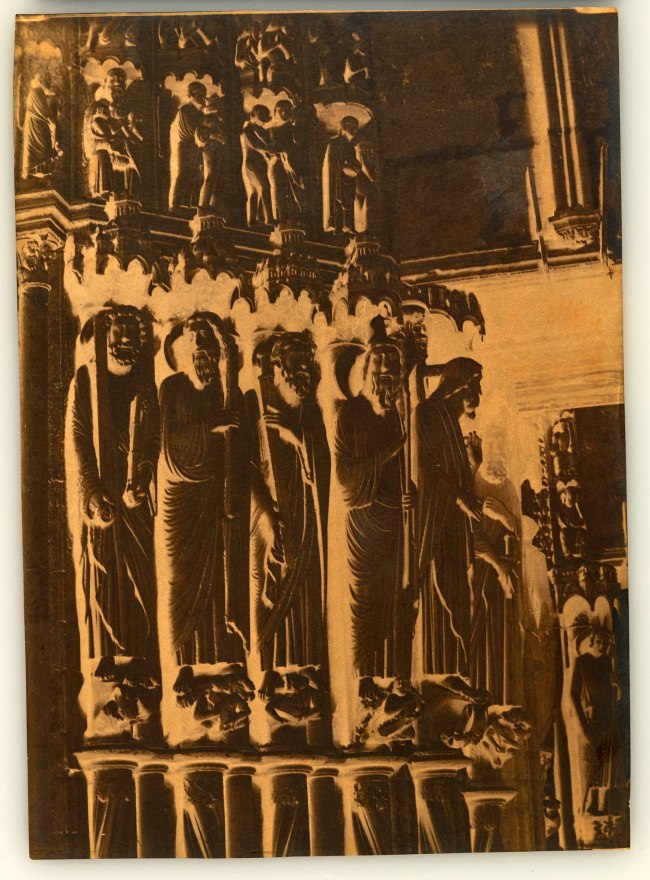

Désiré Charnay (French, 1828-1915)

Chichen Itza: Bas-relief des Tigres, Palais du Cirque (Chichen Itza: Bas-relief of the Tigers, Circus Palace)

1859-1861

Print on gold-toned albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RES PHOTO VZ-940-FT4

In 1861, Charnay gave Napoleon III a copy of the album American Ruins composed for the Emperor of expensive proofs on albumen paper toned with gold, in an exceptional format, the miraculous result of his Mexican epic. The shift to gold accentuates the vigour of the contrasts and brings a cold tone to the blacks.

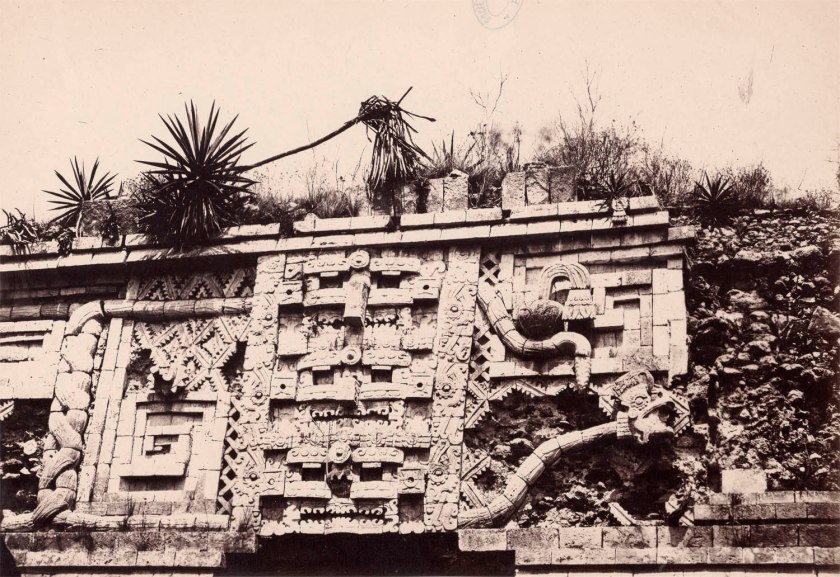

Désiré Charnay (French, 1828-1915)

Uxmal: détail de la façade dite de la couleuvre (Uxmal: detail of the so-called snake facade)

1859-1861

From the album American Ruins

Print on gold-toned albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

59 x 78.2cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RES PHOTO VZ-940-FT4

The forty-nine views of the ruins of Yucatan, Chiapas, Tabasco and the province of Oaxaca constitute the first set of photographs entered into the collections of the Geographical Society, in 1861. During the general assembly of November 29 , Charnay presents his collection of photographs exhibited in the meeting room. The same day, at the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles Lettres, Jomard returns to the quality of Charnay’s photographs, which allow us to conclude that American art – the Egyptologist’s supreme tribute – “deserves a place alongside Assyrian art, and even alongside the art of the Egyptians.”

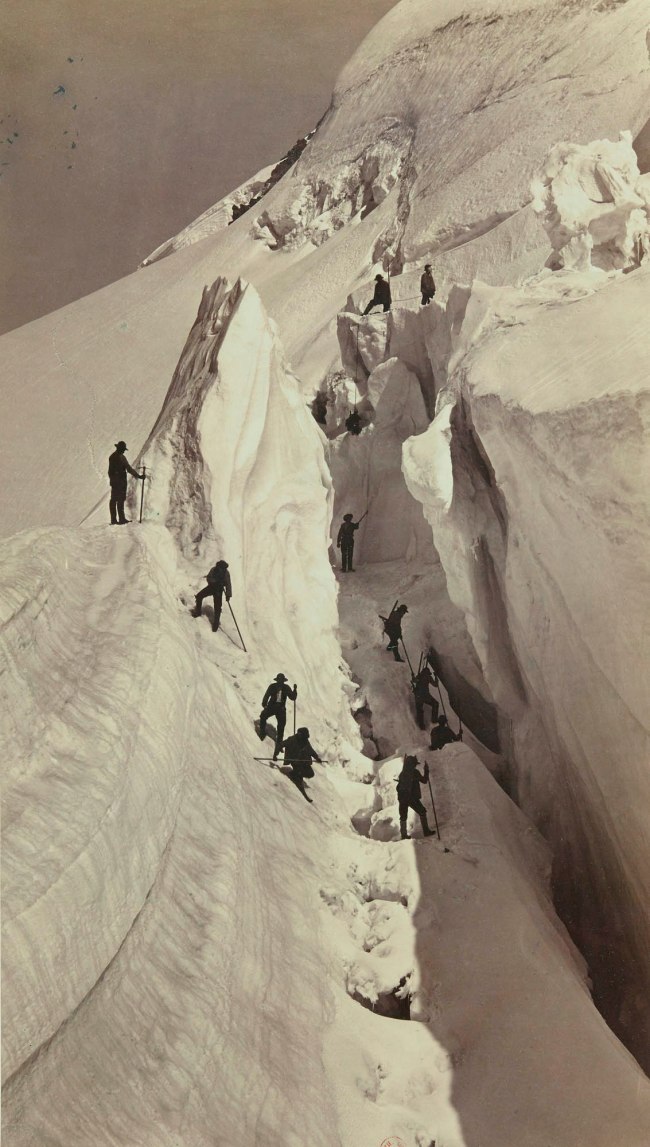

Bisson frères. Louis-Auguste (French, 1814-1876) and Auguste-Rosalie (French, 1826-1900)

La crevasse (départ) sur le chemin du grand plateau, ascension du Mont-Blanc (The crevasse (departure) on the way to the grand plateau, ascent of Mont-Blanc)

1862

Print on albumen paper from a wet collodion glass negative

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-14 (3)-FOL

In 1861, the Bisson brothers managed to hoist their photographic equipment to the summit of Mont Blanc. Mountaineering feat, photographic feat: in these extreme conditions, the plate must be sensitised just before use and developed as soon as possible. The violence of the contrasts, when the brightness of the snow juxtaposes the black of the rocks, redoubles this technical challenge. This conquest of the limit is crowned by the harmony of the print, carried by a site with spectacular aesthetic qualities.

This exhibition brings together black and white masterpieces from the photographic collections of the National Library of France. Nadar, Man Ray, Ansel Adams, Willy Ronis, Helmut Newton, Diane Arbus, Mario Giacomelli, Robert Frank, William Klein, Daido Moriyama, Valérie Belin…: the big names in French and international photography are brought together in a journey which presents approximately 300 prints and embraces 150 years of history of black and white photography, from its origins in the 19th century to contemporary creation.

Black and white is inseparable from the history of photography: its developments, from the end of the 19th century to today, have revealed its plastic force. While the use of colour intensified from the 1970s, black and white reinvented itself as a means of assertive aesthetic expression emphasising graphics and material. Black and white photography remains less expensive and simpler, but its persistence to this day can be explained above all by the fact that it has come to embody the very essence of photography. It appears to carry a universal, timeless, even memorial dimension, where colour would be the sole translation of the contemporary world.

The exhibition in brief

The exhibition addresses the question of black and white from an aesthetic, formal and sensitive angle, emphasising the modes of image creation: plastic and graphic effects of contrasts, play of shadows and lights, rendering of materials in all the palette of values from black to white. The emphasis was placed on photographers who concentrated and systematised their artistic creation in black and white, experimented with its possibilities and limits or made it the very subject of their photography such as Man Ray, Ansel Adams, Ralph Gibson, Mario Giacomelli or Valérie Belin. Particular attention was paid to the quality of the prints, the variety of techniques and photographic papers, but also to the printing of black and white, books and magazines having long been the main relay to the public for photographic creation .

The exhibition thus shows the richness and extent of the BnF’s photographic collections. Among the richest in the world with some six million prints, these are particularly representative of this abundant history of black and white photography.

Exhibition co-organised with the Réunion des Musées Nationaux – Grand Palais

Commissariat

Sylvie Aubenas, director of the Prints and Photography department, BnF

Héloïse Conésa, head of the photography department, responsible for contemporary photography at the Department of Prints and Photography, BnF

Flora Triebel, curator in charge of 19th century photography at the Department of Prints and Photography, BnF

Dominique Versavel, curator in charge of modern photography at the Department of Prints and Photography, BnF

Text from the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF)

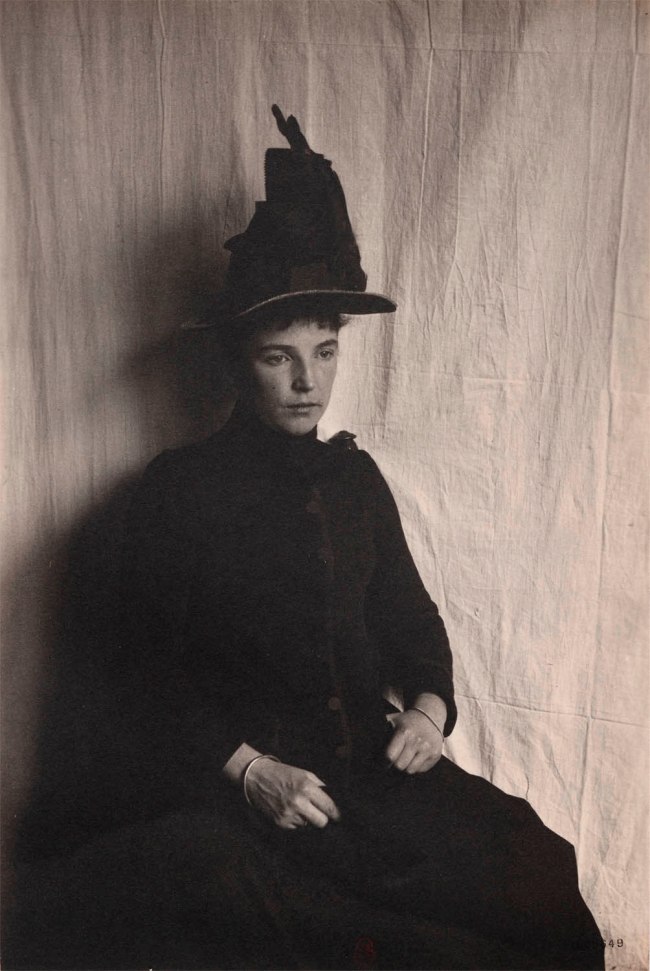

Hippolyte Blancard (French, 1843-1924)

Mademoiselle L. Vulliemin, à mi-corps, la tête couverte d’un chapeau (Miss L. Vulliemin, half-length, head covered with a hat)

1889

Platinum print from a gelatin-silver bromide glass negative

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-508-PET FOL

Gift of print dealer Maurice Rousseau, 1944

Amateur photographer, wealthy pharmacist enriched by the sale of digestive pills, Blancard creates a prolific and picturesque work in a superb contrast of black and white thanks to the use of platinum. This expensive process, patented in 1873, ensures stable prints with marked contrasts which do not stifle the rendering of halftones.

Émile Zola (French, 1840-1902)

Denise et Jacques, les enfants d’Émile Zola (Denise and Jacques, the children of Émile Zola)

1898 or 1899

Gelatin aristotype, gelatin aristotype on matte velvety paper with toning, cyanotype, silver print, gelatin aristotype toned with gold, collodion aristotype with toning

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, NZ-214-8

Purchase at public sale, 2017

From 1894, the novelist devoted himself with passion to photography, in an intimate vein. Here he tests the effects of his shooting by varying the papers, the processes, the tones based on the same negative on a glass plate. We see that black and white is a monochromy among others (brown, orange, blue). Very few of these test prints created in the privacy of the photographer’s laboratory have reached us; the collection of these six prints is exceptional.

Frères Séeberger. Jules, Louis and Henri Séeberger (French, 1872-1932; 1874-1946; 1876-1956)

Untitled

1909-1912

Silver print on baryta paper

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, OA-38 (1)-BOITE FOL

Acquisition-donation from the family, 1976

Frères Séeberger. Jules, Louis and Henri Séeberger (French, 1872-1932; 1874-1946; 1876-1956)

Untitled

1909-1912

Silver print on baryta paper

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, OA-38 (1)-BOITE FOL

Acquisition-donation from the family, 1976

For almost half a century, the Séeberger brothers, specialising in fashion reporting, captured elegant women in their natural settings, racecourses, palaces, upscale beaches. The print on baryta paper, used here, marks a technical breakthrough. A layer of pure white barium sulfate is now interposed between the print support and the binder layer, where the image is formed. Manufactured industrially from the 1890s, chemically developed baryta papers and their characteristic cold tone would dominate silver production until the 1970s.

Frères Séeberger. Jules, Louis and Henri Séeberger (French, 1872-1932; 1874-1946; 1876-1956)

Untitled

1909-1912

Silver print on baryta paper

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, OA-38 (1)-BOITE FOL

Acquisition-donation from the family, 1976

In Black and White

Entirely designed from the Library’s rich collections, Black & White: An aesthetic of photography presents more than 300 works from the 19th century to the present day which bear witness to the use black and white from more than 200 photographers from around the world.

Considering black and white photographic creation from the 19th century to the most contemporary works, the exhibition presented at the François-Mitterrand affirms an ambition commensurate with the historical and geographical scope of the BnF’s collections and their immense variety technical and stylistic. The Department of Prints and photography has been a high place of conservation and emulation for monochrome photographic expression, under the impetus in particular of Jean-Claude Lemagny. Recently deceased, this very first curator of photography contemporary, in office from 1968 to 1996, was a fervent defender of black and white aesthetics.

In the 19th century, the powerlessness of photography to reproduce colours do not reduce it only to black and white and the tonal variations (blue, sepia, etc.) are in fact multiple. The exhibition opens with a spectacular monochrome of prints by Émile Zola, alongside luxurious prints by Gustave Le Gray, by Désiré Charnay and the Bisson brothers. It is at the turn of the 20th century that black and white became the tonality of photography par excellence, with the generalisation of the gelatin-silver bromide process.

An artistic and aesthetic approach

The rest of the journey deliberately interweaves creations of the 20th and 21st centuries, without chronological consideration. According to a primarily artistic and aesthetic approach to black and white, works of authors, decades, styles, schools and various origins interact, in order to highlight visual constants and graphics observable in use by black and white by photographers from 37 countries. That the photographers either suffered lack of colour or – from the 1950s-1970s – preferred to it, black and white is appreciated by artists for its numerous graphic, material and symbolic, which allow them to obtain certain effects features.

Write in black and white

These are these different ways of writing in black and white that the exhibition shows, starting with the contrasts: prints by Imogen Cunningham and André Kertész at the sculptural portraits of black women by Valérie Belin, in passing through the photograms of Man Ray, the books of William Klein or the fashion photographs of Helmut Newton, the contrast is deliberately sought by certain artists. By accentuating blacks and whites, or even making them disappear to any intermediate shade of grey, they bring out the essential lines of their subjects, retrace the design of the world,

gain visual and graphic expressiveness.

The play of shadows and light, at the origins of the photographic act, forms another part of the exhibition highlights. Bringing together the works of photographers as varied as Brassaï, Alexandre Rodtchenko, Henri CartierBresson, Willy Ronis, Flor Garduño, Daido Moriyama, Arthur Tress or Ann Mandelbaum, this part emphasises the dazzling effects or shadows cast, explored by these artists in their portrait practice, of the street snapshot, of the nocturnal shooting or in their laboratory experiments.

The exhibition continues with a chart of tests deployed in ribbon, from the blackest to the whitest. These prints signed Jun Shiraoka, Emmanuel Sougez, Edward Weston, Barbara Crane or Israel Ariño recall the ability of black and white to render effects of matter by its infinite variations of grey or, conversely, suggest the overflow or disappearance of all matter.

A sensory experience

The journey ends with a paradox with the works of photographers who, like Patrick Tosani, Marina Gadonneix or Laurent Cammal, disturbing the visitor’s perception by using colour processes to represent a black and white subject – an ultimate game with codes inherited from their art. Designed to show the historical depth and the richness of the BnF collections, this exhibition is intended to be educational and sensitive: emphasising certain technical aspects linked to printing practices, while insisting also on the irreducible material part of this art. By the high quality of prints presented, the exhibition offers to the public a sensory experience that will make them perceive the nuances hidden behind this apparently monolithic notion black and white.

Flora Triebel and Dominique Versavel. “En Noir et Blanc,” in Une saison en photographie, Chroniques No. 98, BnF, September – December 2023

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Parc de Sceaux, Duchess Alley

Between 1925 and 1927

Print on matte albumen paper from gelatin-bromide glass negative

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-109 (16)-BOITE FOL B

Eugène Atget claimed a humble, artisanal practice of photography. He used the same old camera and printing paper for decades. Only the disappearance of his usual supplies forced him to change. There is therefore no aesthetic research, yet these colour variations tell us a lot about the perception of the image.

The photographer artist can choose the colours of his prints by playing on the chemistry of the fixing baths or on the nature of the papers.

Gold toning, known since the 1850s, produces deep blacks but is very expensive. Baryta or platinum papers appeared at the end of the century and made it possible to further accentuate contrasts.

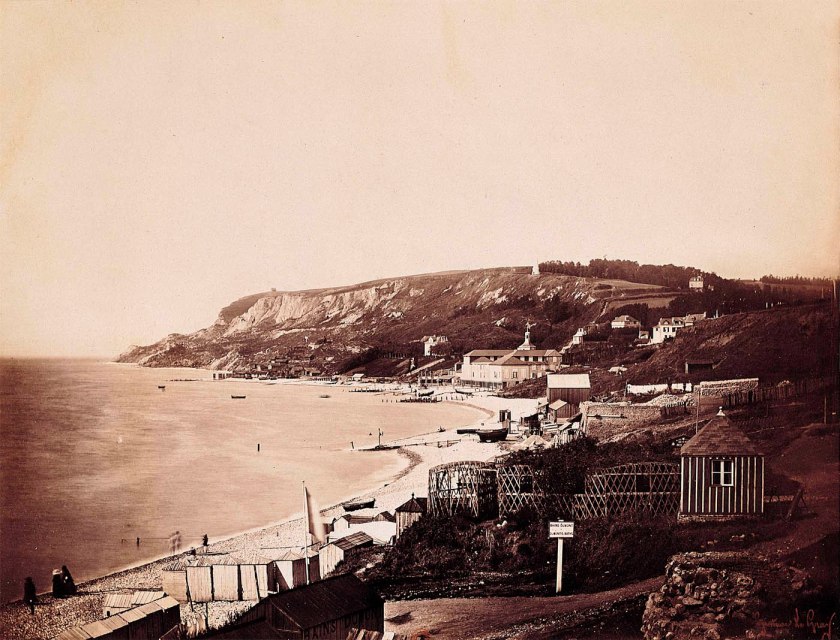

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Plage de Sainte-Adresse avec les bains Dumont (Sainte-Adresse beach with Dumont baths)

1856

Print on albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

31.3 x 41.3cm

Former Alfred Armand collection

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

The strength of the blacks and whites, the variations of hues influence our perception of the image: the more contrasted it is, the more readable it is for our eye saturated with absolute blacks and whites; the more nuanced it is, the more sensitive the distance of time becomes.

Provenance

This article was designed as part of the exhibition “Black & White – An aesthetic of photography” presented at the BnF from October 17, 2023 to January 21, 2024.

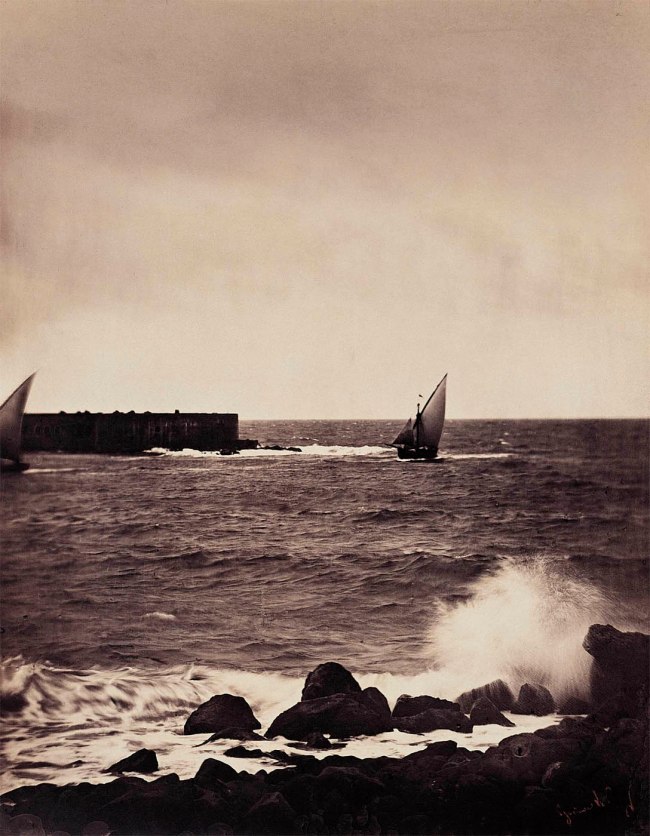

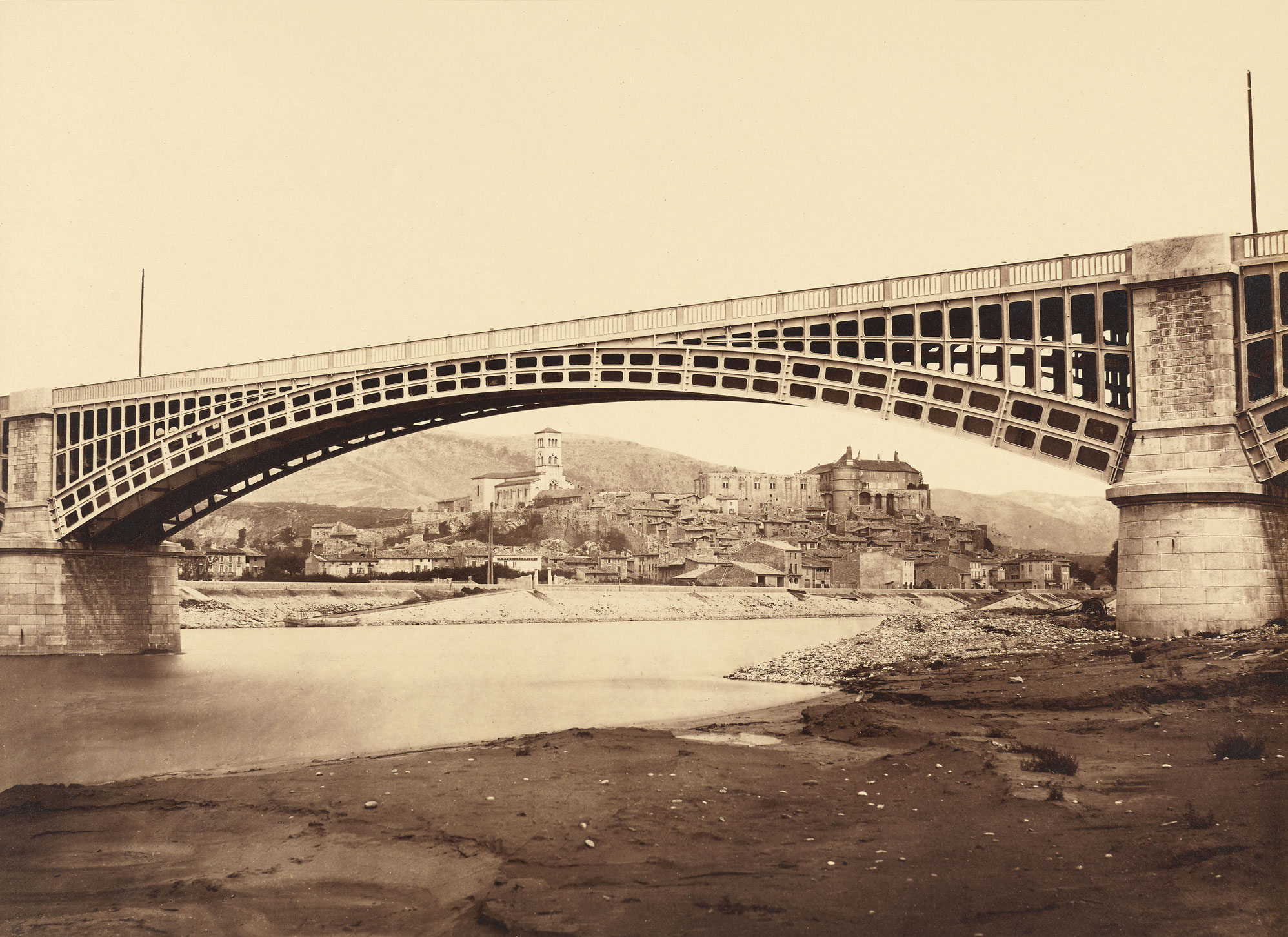

The marines of Le Gray

Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884) is a central figure in 19th century photography. A contemporary of photographers like Nadar, Charles Nègre and Henri Le Secq, he began his career by training as a painter. With great mastery of photographic technique, he developed two major inventions, the collodion glass negative in 1850 and the dry wax paper negative in 1851.

Le Gray’s seascapes mark not only a milestone in the history of photography, but also its true intrusion into a pictorial genre characteristic of the English school. Fixing the movement of the waves while the snapshot is still stammering, combining two negatives, one for the sky and one for the sea, Le Gray plays like a virtuoso with a complex technique in the service of a lyrical vision, which prefigures marine studies by Courbet in the 1860s-1870s. The success was immense in France and England: these “enchanted paintings” were acquired by crowned heads, aristocrats, artists and art collectors.

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Vapeur (Steam)

1856-1857

Print on albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

31.3 x 37.2cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, ESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Groupe de navires – Sète – Méditerranée – No. 10 (Group of ships – Sète – Mediterranean – No. 10)

1857

Print on albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

29.9 x 41.2cm

Former Alfred Armand collection

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

La Vague brisée. Mer Méditerranée No. 15 (The Broken Wave. Mediterranean Sea No. 15)

1857

Photograph, albumen paper, collodion glass negative

41.7 x 32.5cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

La Grande vague – Sète – N° 17 (The Great Wave)

1857

Photograph, albumen paper, collodion glass negative

35.7 x 41.9 cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Flotte franco-anglaise en rade de Cherbourg (Franco-English fleet in Cherbourg harbour)

August 4-8, 1858

Print on albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

31 x 39.8cm

Former Alfred Armand collection

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE FOL-EO-13 (3)

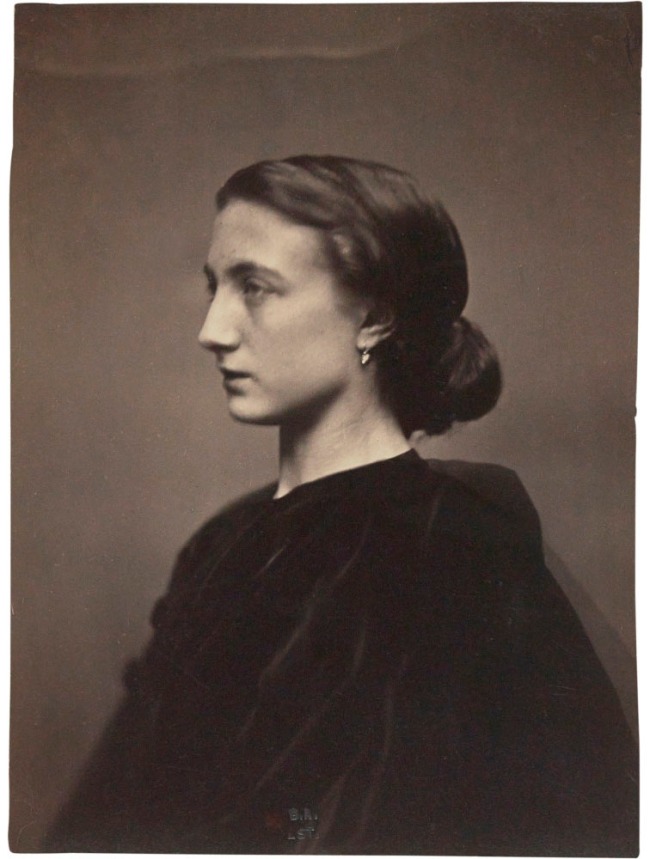

Félix Nadar (French, 1820-1910)

La Princesse Marie Cantacuzène (The Princesse Marie Cantacuzène)

around 1855-1860

Varnished salted paper print from a collodion glass negative

20.8 × 15.3cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-15 (2)-PET FOL

Nadar created two portraits of this classically beautiful young woman. It indicates on the back of one of the proofs that it is the Romanian princess, Marie Cantacuzène.

The portrait by Félix Nadar

Until the beginning of the 1880s, Félix Nadar’s portraits were distinguished by their neutral backgrounds.

The merit of Mr. Nadar’s portraits does not consist only in the skill of the pose, which is entirely artistic, there is a learned and reasoned arrangement of the light, which attenuates or increases the daylight depending on the character of the head. and the operator’s instinct. We also find in the printing of the proofs a delicate search for harmony and slightly faded tones which soften the edges of the contours with their darkness.

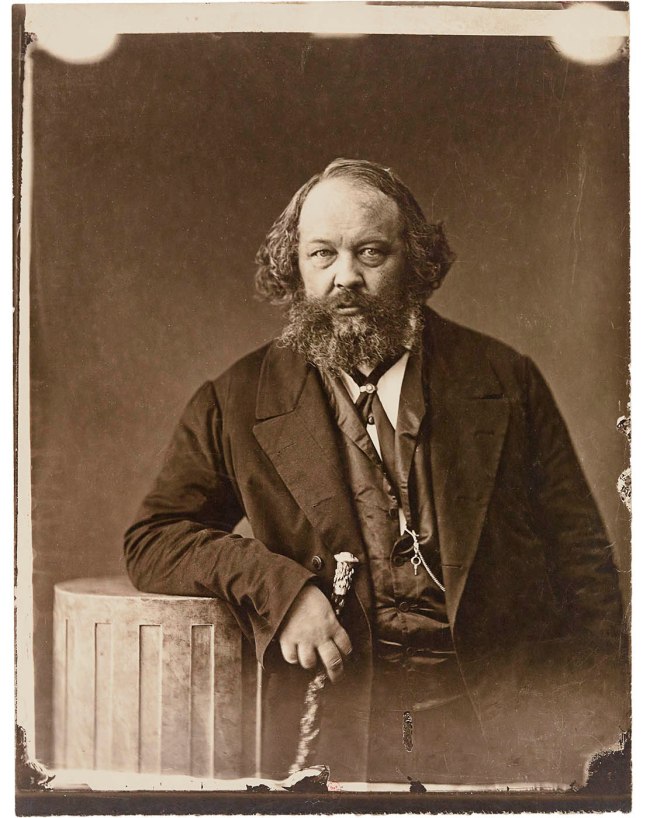

Félix Nadar (French, 1820-1910)

Bakounine

About 1862

Silver print from the original negative on collodion glass

27.1 × 20.6cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-15 (4)-FOL

The revolutionary, philosopher and theoretician of socialism Mikhail Bakunin is one of the immense personalities that Nadar photographed during his career and offered to clients in his constantly enriched portrait gallery. We see here a print from 1862, contemporary with the shooting, but there is also a print made twenty years later and finally a print around 1900, brought up to date after heavy retouching. Thus until the end of the activity of the Nadar workshop, the oldest portraits of celebrities were always offered to customers.

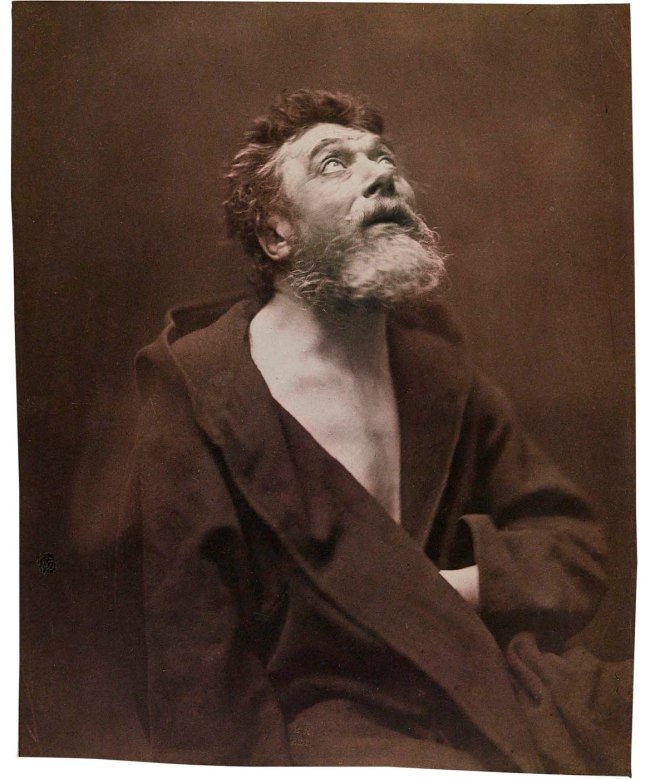

Félix Nadar (French, 1820-1910)

Jean Journet (1799-1861)

1857

Salted paper print from collodion glass negative

27.4 x 21.8cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-15 (9)-PET FOL

Jean Journet, nicknamed the Apostle, was a picturesque and eccentric Parisian figure, often ridiculed by his contemporaries. Former carbonaro, pharmacist in Limoux, he discovered the philosophy of Fourier and decided to spread his doctrine by abandoning his family and taking his pilgrim’s staff. His humanitarian evangelism, advocating fraternity and association, led him to write numerous pamphlets which he distributed in an untimely manner: by throwing them from “paradise” into theatres or by laying siege to famous writers and editorial offices. Interned several times in Bicêtre, Journet found upon his death a defender in Nadar who published an article in Le Figaro on October 27, 1861, concluding: “Ah my dear fools! that I love you much better than all these wise men.”

Nadar draws inspiration from Spanish painting from the Golden Age to render “this dazzling head of Saint Peter”.

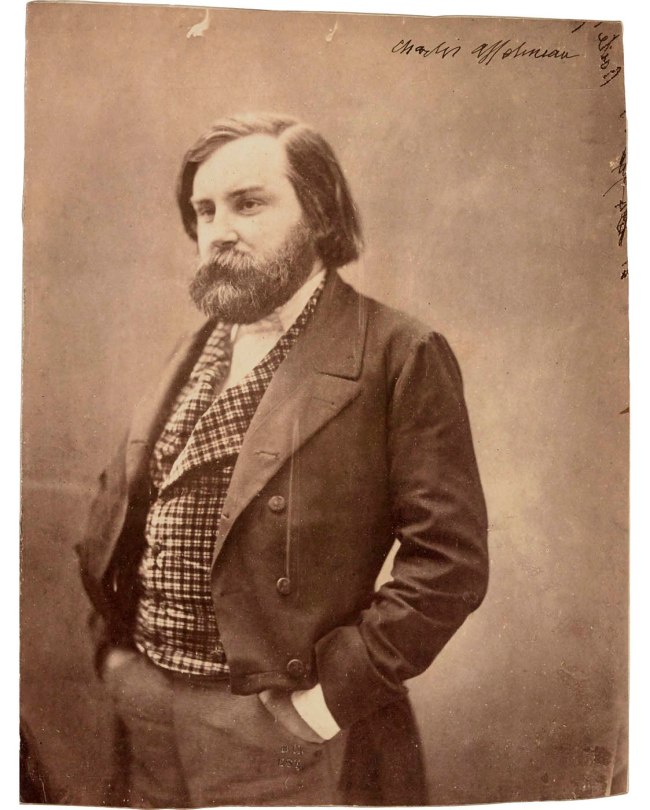

Félix Nadar (French, 1820-1910)

Charles Asselineau (1820-1874)

Between 1854 and 1870

Print on albumen paper from a collodion glass negative

23.8 x 18.1cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EO-15 (1)-PET FOL

Charles Asselineau is one of Nadar’s oldest friends. They became friends at the Collège Bourbon and were both close friends of Baudelaire. A fine scholar and supernumerary librarian at Mazarine, Charles Asselineau, author of, among other things, Paradis des gens de lettres and L’Enfer du Bibliophile, was close to the publisher Poulet-Malassis, nicknamed by Baudelaire “Coco-mal-perché”. He collaborated with Nadar on two short stories published in April and August 1846: “The Healed Dead” and “The Found Paradise”, reprinted in When I Was a Student. He belonged to the small circle of editors who documented the Pantheon-Nadar to which biographies of each character were originally to be annexed.

He was Nadar’s best man at his wedding… warned, however, two weeks after the ceremony. The groom explained this in a letter: “It’s quite funny that my first witness learned of my marriage 15 days after the consummation and through an announcement letter. This, my good friend, will be explained to you by me on our first trip. I will limit myself to telling you for the present that I went to your house the day before, a Sunday and that on Monday morning at noon time fixed for the ceremony I did not know at 11 o’clock if I was getting married.” (NAF 25007, fol. 8).

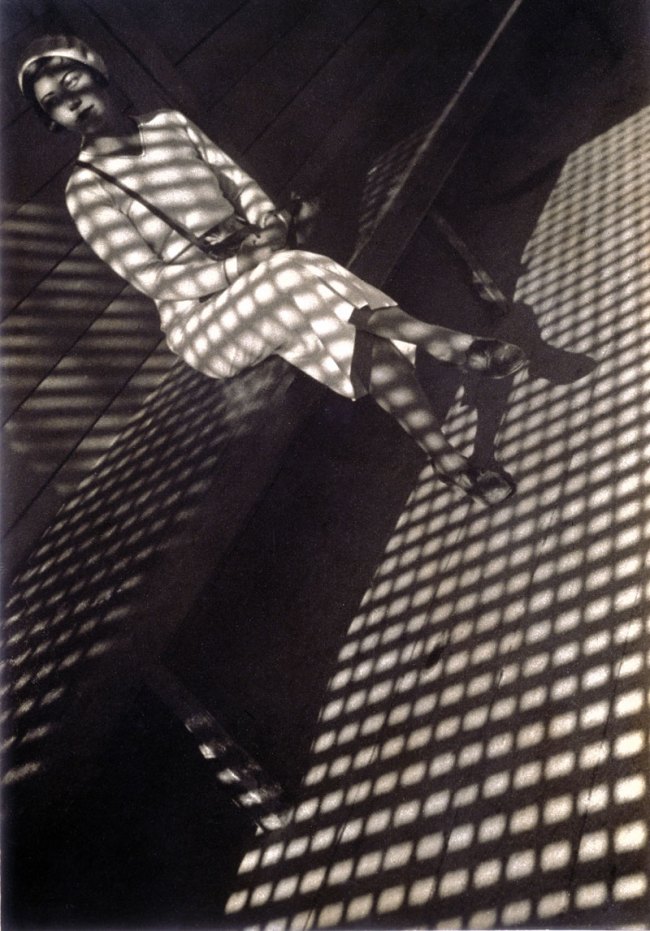

Alexandre Rodtchenko (Russian, 1891-1956)

Jeune fille au Leica (Young girl with Leica)

1934

BnF, prints and photography

Piergiorgio Branzi (Italian, 1928-2022)

Bar sur la plage, Adriatique (Beach bar, Adriatic)

1957

BnF, prints and photography

Willy Ronis (French, 1910-2009)

Venise (Venice)

1959

BnF, prints and photography

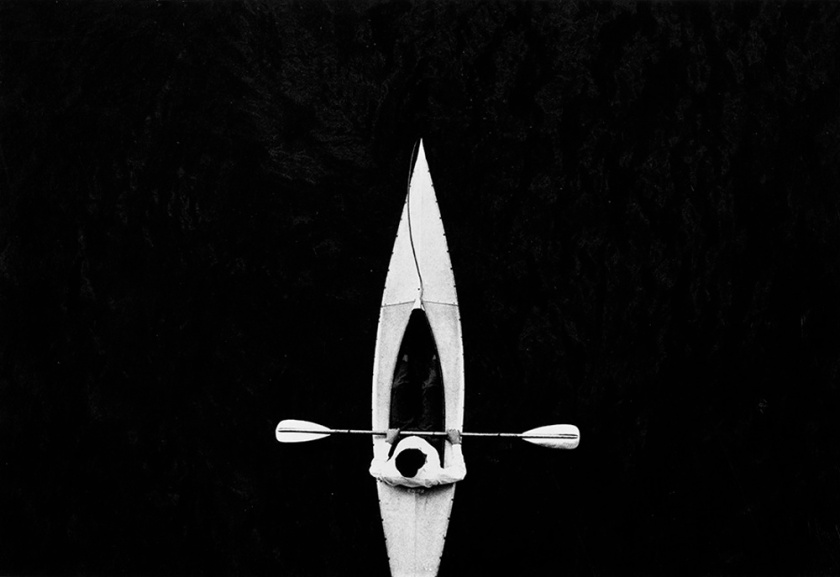

Ray K. Metzker (American, 1931-2014)

Kayak, Frankfurt

1961, printed around 1970

Silver gelatin print

20 x 25.1cm

BnF, Department of Prints and Photography, EP-91 (1)-FOL

Purchase from the author, 1970

Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

© Estate of Ray K. Metzker

A student of Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind at the Institute of Design in Chicago, Metzker sublimates the formal particularities of this school through exceptional mastery black and white: he excels at stylising reality by constructing his images in direct opposition to dark and light flat areas.

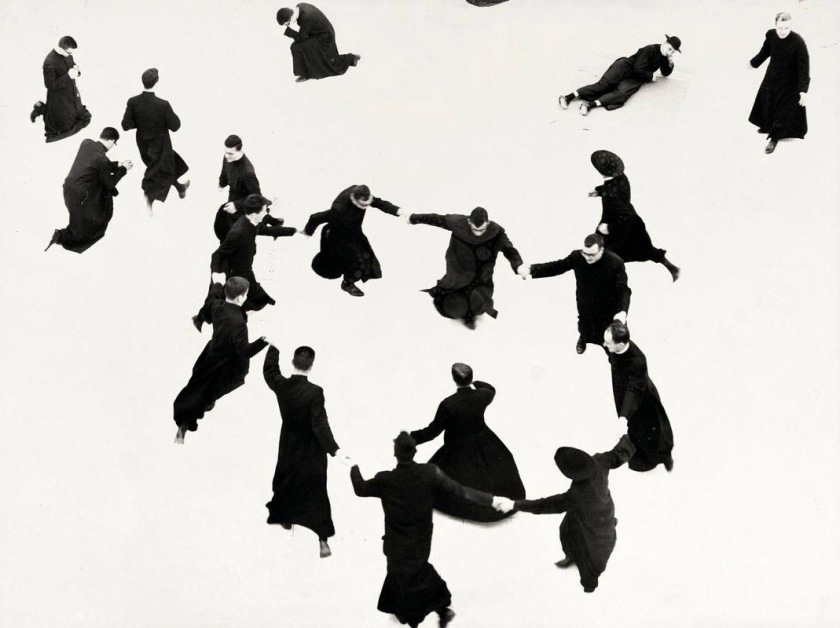

Mario Giacomelli (Italian, 1925-2000)

Je n’ai pas de main qui me caresse le visage (I have no Hands caress my face)

1961-1963

BnF, prints and photography

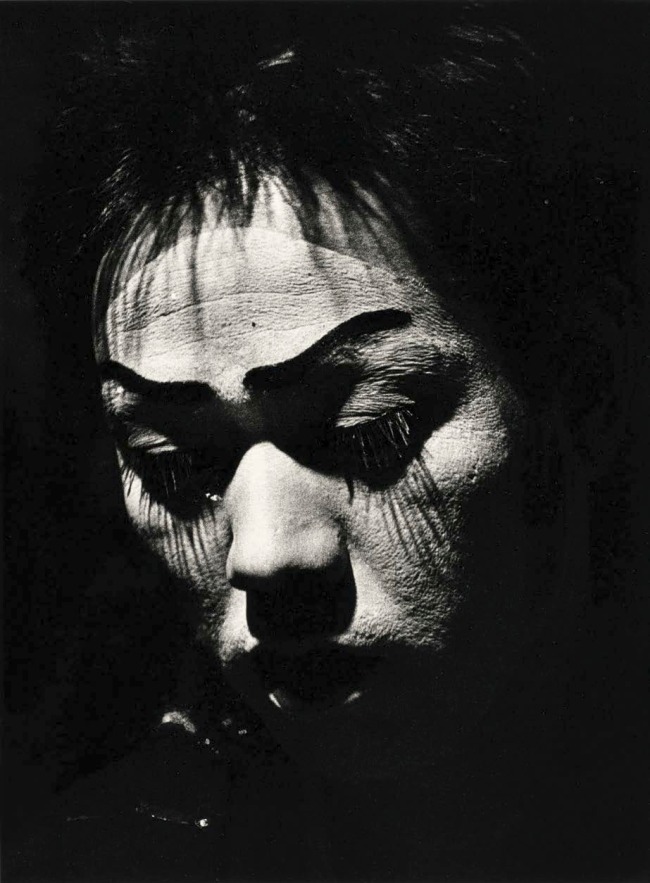

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Portrait d’acteur (Actor portrait)

1968

From the series Japanese theatre

BnF, prints and photography

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

1er janvier 1972 à la Martinique (January 1, 1972 in Martinique)

1972

BnF, prints and photography

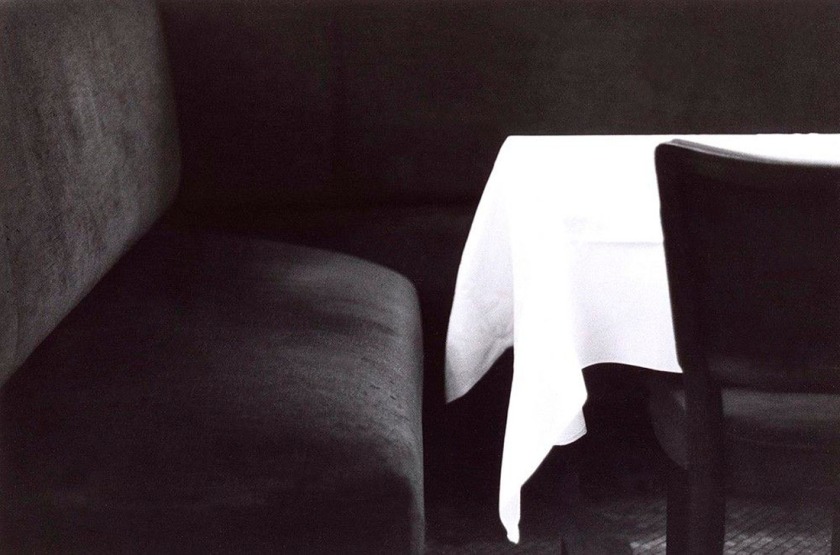

Bernard Plossu (French, b. 1945)

Paris

1973

BnF, prints and photography

Mary Ellen Mark (American, 1940-2015)

Immigrants, Istanbul, Turkey

c. 1977

BnF, prints and photography

Koichi Kurita (Japanese, b. 1962)

Melting Snow on a Rock, Nagano, Japan

1988

BnF, prints and photography

Flor Garduño (Mexican, b. 1957)

Canasta de Luz (Corbeille de lumière)(Basket of Light)

1989

BnF, prints and photography

Laurence Leblanc (French, b. 1967)

Chéa, Cambodge (Chéa, Cambodia)

2000

From the series Rithy Chéa Kim Sour and the others

BnF, prints and photography

Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand

Quai François Mauriac, 75706 Paris Cedex 13

Phone: +33(0)1 53 79 59 59

Opening hours:

Monday: 2pm – 8pm

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday: 9am – 8pm

Sunday: 1pm – 7pm

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal12-web.jpg?w=650&h=800)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal21-web.jpg?w=650&h=821)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

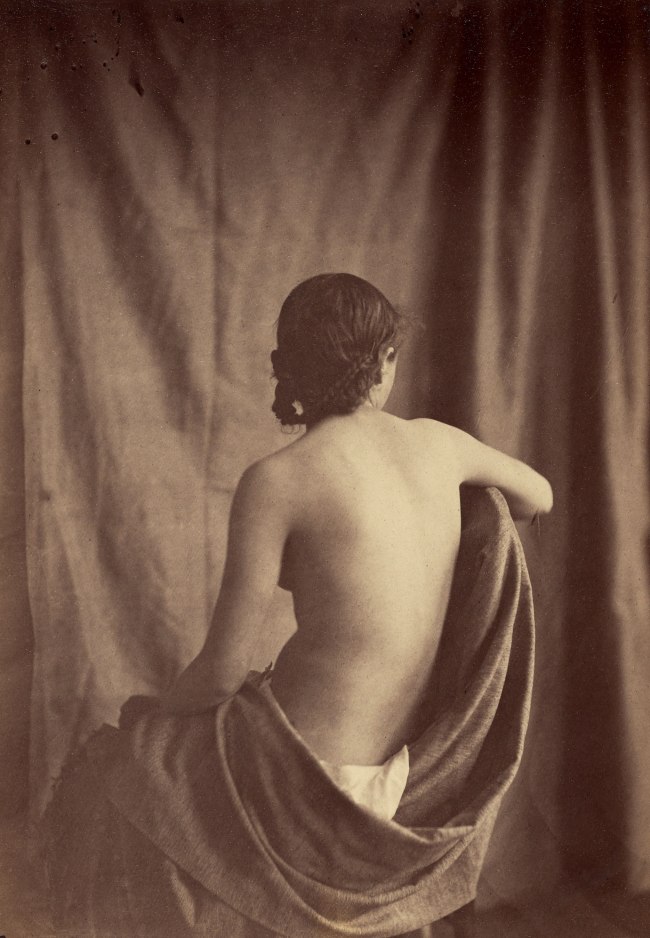

![Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-59 Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-59](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/chauvassaignes_seated-nude-web.jpg?w=838&h=1024)

![Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-54 Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-54](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/durieu_nude_ph8976-web.jpg?w=704&h=1024)

![Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855 Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/marle_standing-male-nude-web.jpg?w=701&h=1024)

![Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850 Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/moulin_two-nudes-standing-web.jpg?w=811&h=1024)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-reclining-female-nude.jpg?w=840)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959 - 1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987 Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959 - 1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/16_morrisroe_untitled-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

You must be logged in to post a comment.