Exhibition dates: 16th April – 2nd October 2022

Organised by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator of Photography, with Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, and Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, MoMA

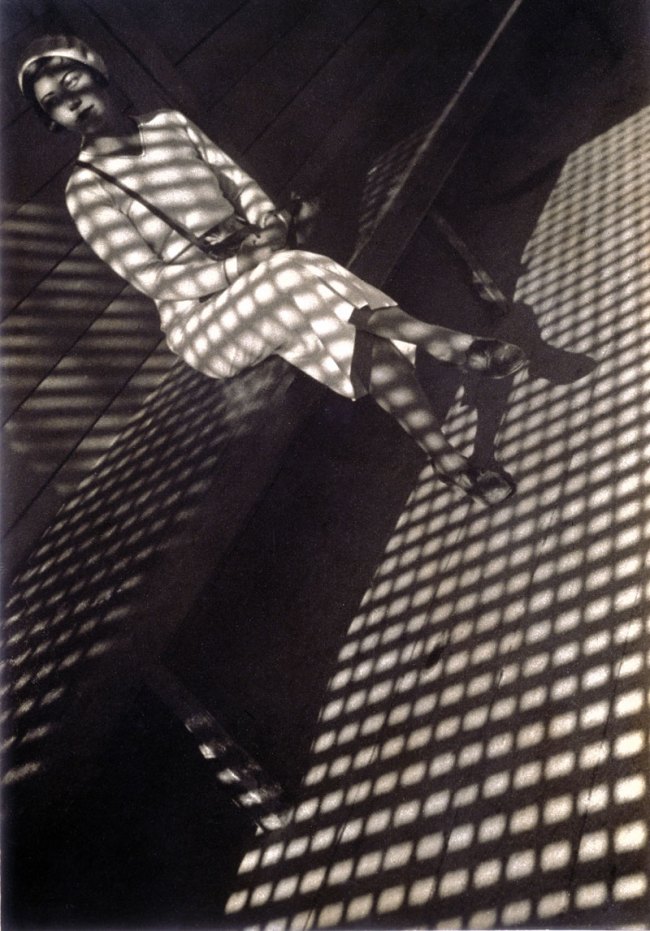

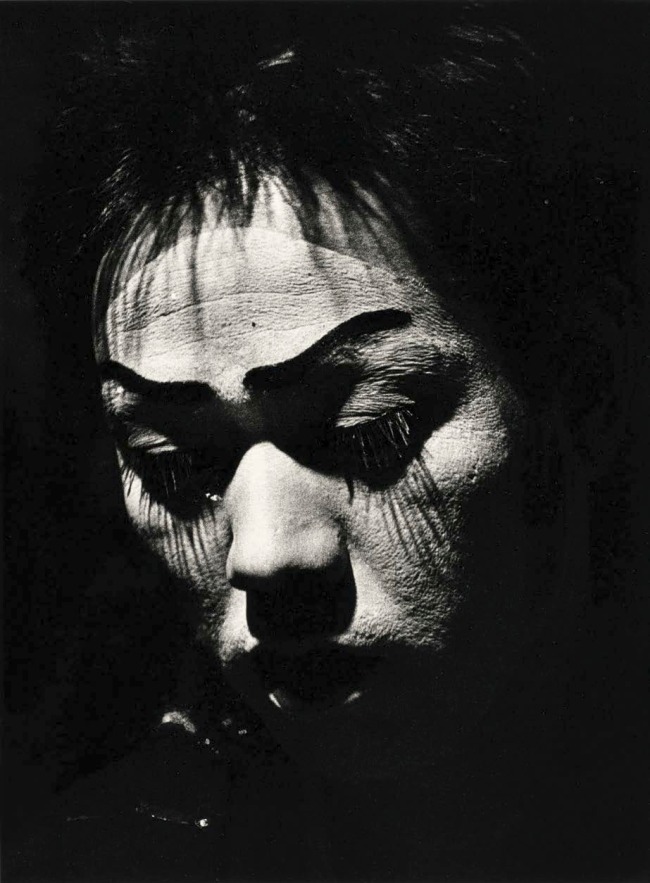

Lotte Jacobi (American, 1896-1990)

Head of the Dancer Niura Norskaya

1929

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 × 9 3/8″ (19.1 × 23.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

With a focus on people, this is a challenging exhibition that can only scratch the surface of the importance of the photographic work of women artists to the many investigations critical to the promotion of equality and diversity in a complex and male orientated world.

Germaine Krull is always a favourite, as is the work of neutered genius (and my hero), Claude Cahun. Susan Meiselas’s immersive work is also impressive in its “understanding of social, political and global issues and of the potentially complex ethical relationship between photographer and subject”, especially in her early work Carnival Strippers (1972-1975). I also particularly like the sensibility of the Mexican women photographers: sensitive portraits of strong women.

The most cringe worthy photograph that illustrates some of the ills associated with a male-orientated society is Ruth Orkin’s staged but spontaneous photograph, American Girl in Florence, Italy (1951, below) which was “an instant conversation starter about feminism and street harassment long… [and which is] more relevant now than ever for what it truly represents: independence, freedom and self-determination.”

“The photos ran in Cosmopolitan magazine in 1952 in a photo essay, “When You Travel Alone…”, offering tips on “money, men and morals to see you through a gay trip and a safe one.” The article encourages readers to buy ship and train tickets ahead of time. It reminds them to bring their birth certificate and check in with the State Department. The caption on the photo of Craig walking down the street reflects cultural mores of the era.

“Public admiration … shouldn’t fluster you. Ogling the ladies is a popular, harmless and flattering pastime you’ll run into in many foreign countries. The gentlemen are usually louder and more demonstrative than American men, but they mean no harm.”

It’s a far cry from what we tell women these days, but for its time the mere notion of encouraging women to travel alone was progressive. That’s what made the photos so special, Craig says. They offered a rare glimpse of two women – behind and in front of the camera – challenging the era’s gender roles and loving every minute of it.”1

Talking of challenging gender roles, I’m rather surprised there aren’t any photographs by Diane Arbus, Cindy Sherman or Francesca Woodman for example, critical women photographers who challenge our orientation towards our selves and the world. Many others could have been included as well. But that is the joy and paradox of collecting: what do you collect and what do you leave out. You have to focus on what you like and what is available.

“Rather than presenting a chronological history of women photographers or a linear account of feminist photography, the exhibition prompts new appraisals and compelling dialogues from a contemporary, intersectional feminist perspective. African-diasporic, queer, and postcolonial / Indigenous artists have brought new mindsets and questions to the canonical narratives of art history. Our Selves will reexamine a host of topics, countering racial and gender invisibility, systemic racial injustice, and colonialism, through a diversity of photographic practices, including portraiture, photojournalism, social documentary, advertising, avant-garde experimentation, and conceptual photography.” (Press release)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Emanuella Grinberg. “The real story behind ‘An American Girl in Italy’,” on the CNN website March 30, 2017 [Online] Cited 28/08/2022

Many thankx to the Museum of Modern Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The Museum of Modern Art announces Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum, an exhibition that will present 90 photographic works by female artists from the last 100 years, on view from April 16 to October 2, 2022. Drawn exclusively from the Museum’s collection, thanks to a transformative gift of photographs from Helen Kornblum in 2021, the exhibition takes as a starting point the idea that the histories of feminism and photography have been intertwined.

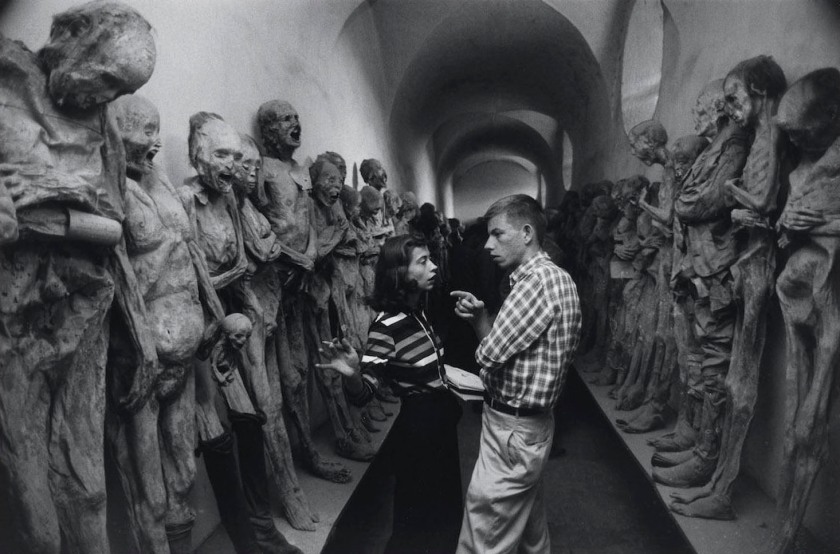

Installation views of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

How have women artists used photography as a tool of resistance? Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum reframes restrictive notions of womanhood, exploring the connections between photography, feminism, civil rights, Indigenous sovereignty, and queer liberation. “Society consumes both the good girl and the bad girl,” wrote artist Silvia Kolbowski in 1984. “But somewhere between those two polarities, space must be made for criticality.”

Spanning more than 100 years of photography, the works in this exhibition range from Frances Benjamin Johnston’s early documentary photographs of racially segregated education in turn-of-the-century United States, to a contemporary portrait by Chemehuevi artist Cara Romero that celebrates the specificity of Indigenous art forms. A tribute to the generosity of collector Helen Kornblum, Our Selves features women’s contributions to a diversity of practices, including portraiture, photojournalism, social documentary, avant-garde experimentation, advertising, and performance.

As we continue to reckon with equity and diversity, Our Selves invites viewers to meditate on the artist Carrie Mae Weems’s evocative question: “In one way or another, my work endlessly explodes the limits of tradition. I’m determined to find new models to live by. Aren’t you?”

Text from the MoMA website

Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989)

Self-Portrait

1932

Gelatin silver print

9 × 11 7/8″ (22.9 × 30.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Germaine Krull (Dutch born Germany, 1897-1985)

The Hands of the Actress Jenny Burnay

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 8 5/8″ (16.5 × 21.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Germaine Krull (Dutch born Germany, 1897-1985)

Germaine Krull was a pioneer in the fields of avant-garde photomontage, the photographic book, and photojournalism, and she embraced both commercial and artistic loyalties. Born in Wilda-Poznań, East Prussia, in 1897, Krull lived an extraordinary life lasting nine decades on four continents – she was the prototype of the edgy, sexually liberated Neue Frau (New Woman), considered an icon of modernity and a close cousin of the French garçonne and the American flapper. She had a peripatetic childhood before her family settled in Munich in 1912. She studied photography from 1916 to 1918 at Bayerische Staatslehranstalt für Lichtbildwesen (Instructional and Research Institute for Photography), and in 1919 opened her own portrait studio. Her early engagement with left-wing political activism led to her expulsion from Munich. Then, on a visit to Russia in 1921, she was incarcerated for her counterrevolutionary support of the Free French cause against Hitler. In 1926, she settled in Paris, where she became friends with artists Sonia and Robert Delaunay and intellectuals André Malraux, Jean Cocteau, Colette, and André Gide, who were also subjects of her photographic portraits.

Krull’s artistic breakthrough began in 1928, when she was hired by the nascent VU magazine, the first major French illustrated weekly. Along with photographers André Kertész and Éli Lotar, she developed a new form of reportage rooted in a freedom of expression and closeness to her subjects that resulted in intimate close-ups, all facilitated by her small-format Icarette, a portable, folding bed camera. During this period, she published the portfolio, Metal (Métal) (1928), a collection of 64 pictures of modernist iron giants, including cranes, railways, power generators, the Rotterdam transporter bridge, and the Eiffel Tower, shot in muscular close-ups and from vertiginous angles. Krull participated in the influential Film und Foto, or Fifo, exhibition (1929-1930), which was accompanied by two books, Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschichold’s Foto-Auge (Photo-Eye) and Werner Gräff’s Es kommt der neue Fotograf! (Here Comes the New Photographer!). Fifo marked the emergence of a new critical theory of photography that placed Krull at the forefront of Neues Sehen or Neue Optik (New Vision) photography, a new direction rooted in exploring fully the technical possibilities of the photographic medium through a profusion of unconventional lens-based and darkroom techniques. After the end of World War II, she traveled to Southeast Asia, and then moved to India, where, after a lifetime dedicated to recording some of the major upheavals of the twentieth century, she decided to live as a recluse among Tibetan monks.

Introduction by Roxana Marcoci, Senior Curator, Department of Photography, 2016

Ruth Orkin (American, 1921-1985)

American Girl in Florence, Italy

1951

Gelatin silver print

8 1/2 × 11 15/16″ (21.6 × 30.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Although this photograph appears to be a street scene caught on the fly-an instance of what Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive moment” – it was actually staged for the camera by Orkin and her model. “The idea for this picture had been in my mind for years, ever since I had been old enough to go through the experience myself,” Orkin later wrote. While travelling alone in Italy, she met the young woman in the photograph at a hotel in Florence and together they set out to reenact scenes from their experiences as lone travellers. “We were having a hilarious time when this corner of the Piazza della Repubblica suddenly loomed on our horizon,” the photographer recalled. “Here was the perfect setting I had been waiting for all these years… And here I was, camera in hand, with the ideal model! All those fellows were positioned perfectly, there was no distracting sun, the background was harmonious, and the intersection was not jammed with traffic, which allowed me to stand in the middle of it for a moment.” The picture, with its eloquent blend of realism and theatricality, was later published in Cosmopolitan magazine as part of the story “Don’t Be Afraid to Travel Alone.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Three Harps

1935

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 × 7 1/2″ (24.4 × 19.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

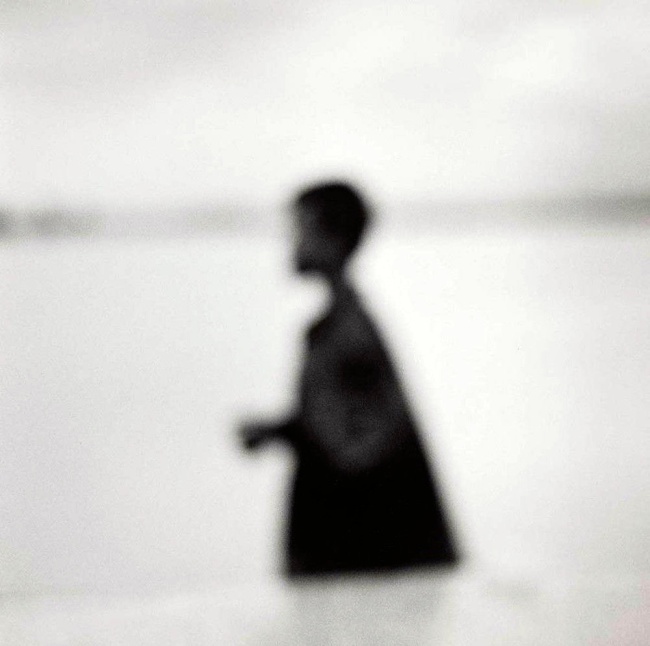

Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978)

School Girl, St. Croix

1963

Gelatin silver print

12 13/16 × 8 15/16″ (32.5 × 22.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Gertrud Arndt (German, 1903–2000)

Untitled (Masked Self-Portrait, Dessau)

1930

Gelatin silver print

9 × 5 5/8 in. (22.9 × 14.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Gertrud Arndt (German, 1903-2000)

Gertrud Arndt (born Gertrud Hantschk in Upper Silicia) set out to become an architect, beginning a three-year apprenticeship in 1919 at the architecture firm of Karl Meinhardt in Erfurt, where her family lived at the time. While there, she began teaching herself photography by taking pictures of buildings in town. She also attended courses in typography, drawing, and art history at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of design). Encouraged by Meinhardt, a friend of Walter Gropius, Arndt was awarded a scholarship to continue her studies at the Bauhaus in Weimar. Enrolled from 1923 to 1927, Arndt took the Vorkurs (foundation course) from László Moholy-Nagy, who was a chief proponent of the value of experimentation with photography. After her Vorkurs, Georg Muche, leader of the weaving workshop, persuaded her to join his course, which then became the formal focus of her studies. Upon graduation, in March 1927, she married fellow Bauhaus graduate and architect Alfred Arndt. The couple moved to Probstzella in Eastern Germany, where Arndt photographed buildings for her husband’s architecture firm.

In 1929, Hannes Meyer invited Alfred Arndt to teach at the Bauhaus, where Arndt focused her energy on photography, entering her period of greatest activity, featuring portraits of friends, still-lifes, and a series of performative self-portraits, as well as At the Masters’ Houses, which shows the influence of her studies with Moholy-Nagy as well as her keen eye for architecture. After the Bauhaus closed, in 1932, the couple left Dessau and moved back to Probstzella. Three years after the end of World War II the family moved to Darmstadt; Arndt almost completely stopped making photographs.

Introduction by Mitra Abbaspour, Associate Curator, Department of Photography, 2014

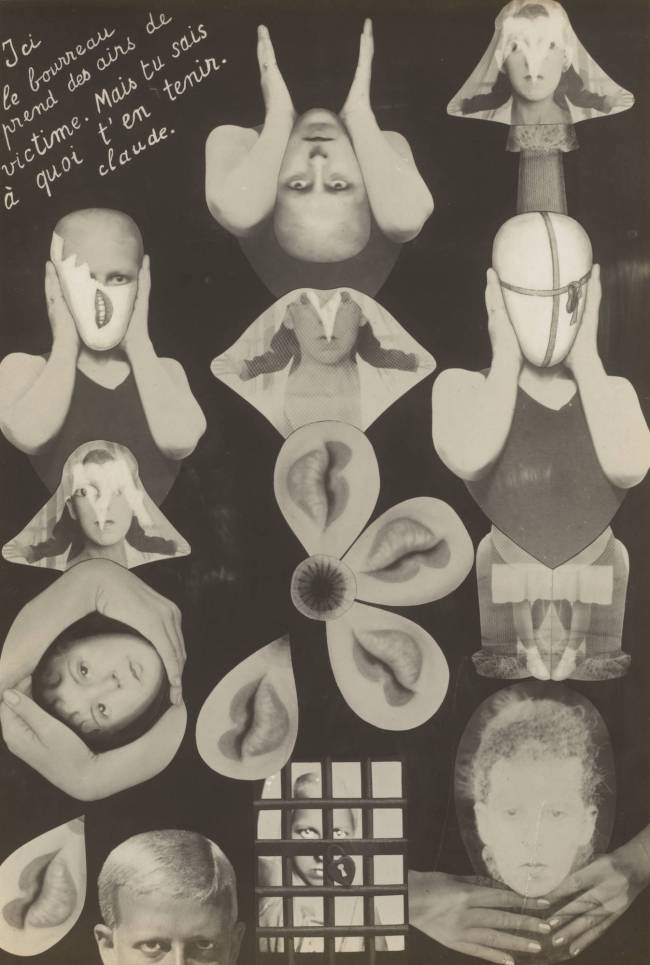

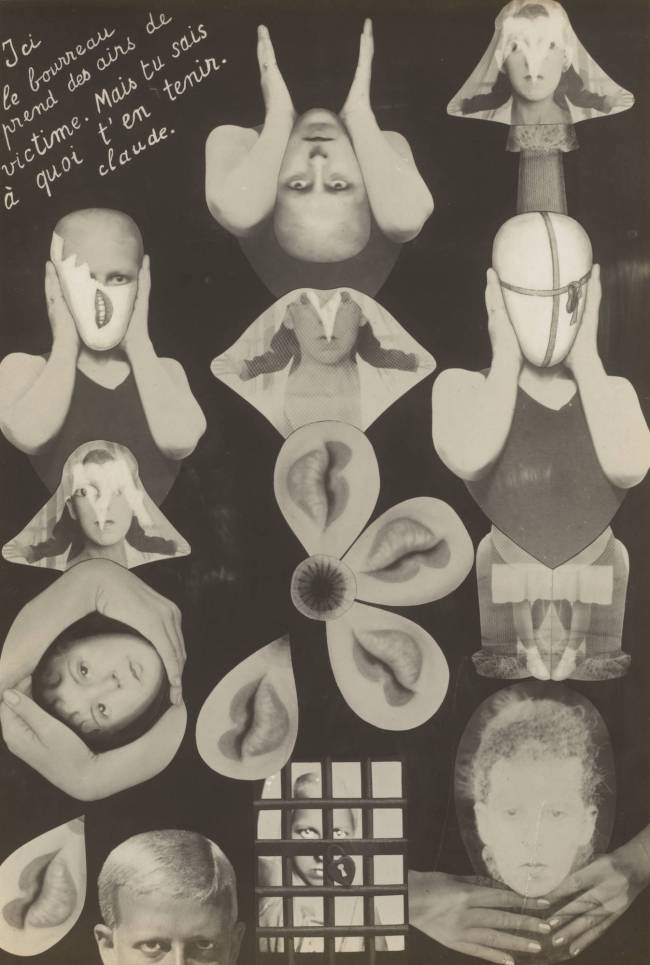

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) (French, 1894-1954)

M.R.M (Sex)

c. 1929-1930

Gelatin silver print

6 × 4 in. (15.2 × 10.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Juliet Jacques: I’m Juliet Jacques. I am a writer and filmmaker based in London. You’re looking at a photomontage by the French artist Claude Cahun, entitled M.R.M (Sex). It’s a photomontage of Cahun’s self-portraits.

Claude Cahun was born in 1894 in France into a family of prominent Jewish intellectuals and began making photomontages in 1912 when she was 18. The works were often exploring Cahun’s own identity in terms of gender and sexuality, but also this sense of a complex and fragmented personhood. Nonbinary pronouns, as we’d understand them now, weren’t officially in existence in the 1920s. Cahun actually wrote “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” So, I think either she or they is appropriate.

M.R.M was published as one of the illustrations in Cahun’s book Aveux non Avenus in 1930. Throughout the book you see this playing with the possibilities of gender expression that are kind of funny, sometimes melancholic, but are very emotionally complicated and do really speak to a sense of sometimes being trapped by the confines of gender and sometimes finding these very playful and beautiful ways to break out of it.

Artists and writers, we’re supposed to be dreamers, I think, and people who want to come up with a better world. And of course Cahun’s work is really suggesting different possibilities of free expression.

It’s hard to know how Cahun might have felt about being included in an exhibition of women artists. But, I think Cahun definitely deserves a place within this feminist canon, if not a strictly female one.

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

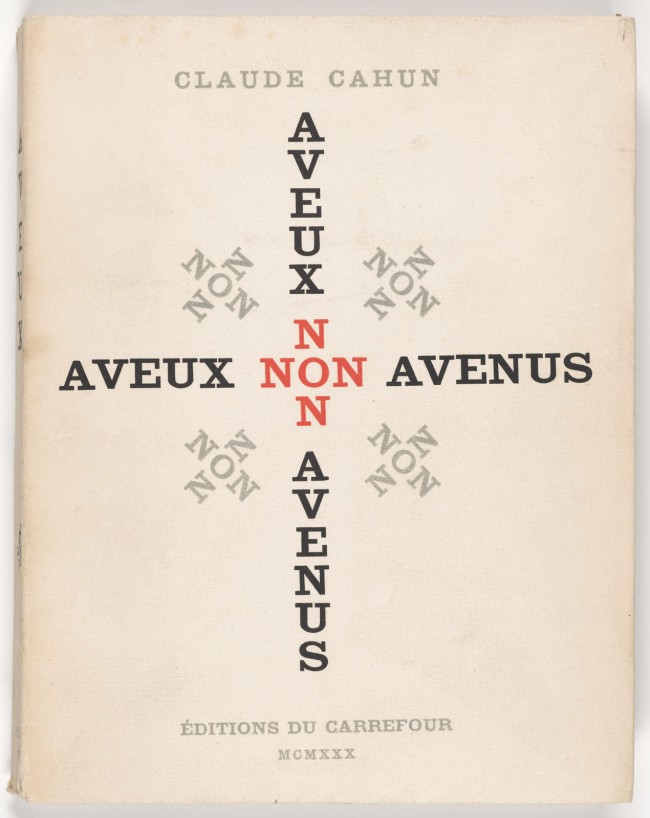

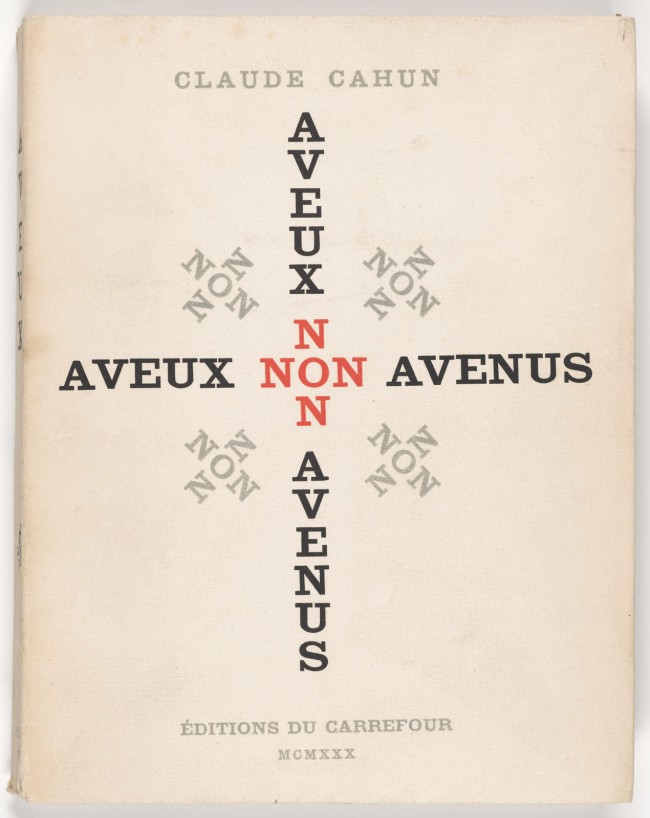

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) (French, 1894-1954)

Aveux non avenus (Disavowals or Cancelled Confessions)

1930

Illustrated book with photogravures

Cover (closed) approx. 8 11/16 × 6 11/16″ (22 × 17cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Juliet Jacques: My name is Juliet Jacques.

You’re looking at Claude Cahun’s book Aveux non Avenus, which has been translated variously as “denials” or “disavowals” or “cancelled confessions.”

It’s an autobiographical text that doesn’t just refuse the conventions of memoir, it also really refuses to open up to the reader in a clearly understandable way. It’s this mixture of photography and aphorisms and longer prose-poetic passages. It doesn’t have a formalised narrative. It’s rather just exploring the fragmented and somewhat chaotic nature of their own consciousness and what they are able to access.

I’ve just flipped to page 91. Cahun writes:

“Consciousness. The carver. My enthusiasms, my impulses, my little passions were irksome. … Come on, then. … By a process of elimination, what is necessary about me? … The material is badly cut. I want it to be straightened up. A clumsy snip with the scissors. Bach! Let’s even it up on the other side. … A stain? We’ll cover it up. Let’s trim it again. I no longer exist. Perfect. Now nothing can come between us.”

The affinity I felt with Cahun is because I ended up doing a lot of writing that got bracketed as confessional or sort of first-person autobiographical writing. You can get yourself into a situation where you’re constantly expected to give away details about your personal life. And what I have always found really interesting about Cahun is the refusal of that trap, even in the project of putting oneself on the page.

I was always looking for queer and trans writers, and Cahun’s work gave me this gender non-conforming take on art that I thought always should have been there.

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (Native American (Seminole-Muscogee-Navajo))

Vanna Brown, Azteca Style

1990

Photocollage

15 11/16 × 22 13/16″ (39.9 × 58cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Veronica Passalacqua: My name is Veronica Passalacqua, and I’m a curator at the C.N. Gorman Museum at the University of California Davis. My research focus is upon contemporary Native American art with a specialty in photography. This is a work called Vanna Brown, Azteca Style by the Navajo-Tuskegee artist Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie.

It’s a hand collage that depicts Tsinhnahjinnie’s friend, dressed in her Azteca dancing regalia within the frame of a Philco television set. It was the beginning of a series of works and videos related to a project called NTV, or Native Television. She wanted to create her own vision of what she’d like to see on television.

Curator, Roxana Marcoci: The photograph makes reference to Wheel of Fortune, a televised game show where contestants guess words and phrases one letter at a time. Vanna White has been the show’s co-host for 40 years.

Veronica Passalacqua: Vanna White was always dressed in these elaborate gowns to show the letters of the enduring game show. She was there really as a symbol of the idealised beauty that television was portraying. Tsinhnahjinnie changes the name from Vanna White to Vanna Brown, addressing the beauty that she sees in her friend. What Tsinhnahjinnie wanted to focus on was this notion that you can create these beautiful images when you have a relationship with the sitter.

I’d like to read you a quote by Tsinhnahjinnie: “No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in, the camera is held with brown hands opening familiar worlds. We document ourselves with a humanising eye, we create new visions with ease, and we can turn the camera to show how we see you.”

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Laura Gilpin (American, 1881-1979)

Navajo Weaver

1933

Platinum print

13 1/8 × 9 3/8 in. (33.3 × 23.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Lola Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1907-1993)

Frida Kahlo

c. 1945

Gelatin silver print

8 3/8 × 6 1/4″ (21.3 × 15.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Lucia Moholy (British born Prague, 1894-1989)

Frau Finsler

1926

Gelatin silver print

7 7/8 × 10″ (20 × 25.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Woman, Locket, Georgia

1936

Gelatin silver print

13 × 9 3/4″ (33 × 24.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Margrethe Mather (American, 1885-1952)

Buffie Johnson, Painter

1933

Gelatin silver print

3 3/4 × 2 7/8″ (9.5 × 7.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Meridel Rubenstein (American, b. 1948)

Fatman with Edith

1993

Palladium print

18 1/2 × 22 1/2″ (47 × 57.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Helen Kornblum: I’m Helen Kornblum. If there’s a theme in my collection, I’d say it’s people. My interest in people, meeting people, knowing people, learning about people.

I have felt about my photographs almost like a third child. Each one actually has its own story for me. Where I found them, who led me to them. I’ve just attached myself in different ways to each one.

One, for instance, is Fatman with Edith by Meridel Rubenstein. With this photograph she conflates war with the feminine. She has the inhumanly destructive warhead, the plutonium bomb, called Fatman, dropped on Nagasaki, juxtaposed with a portrait of a woman, Edith Warner, and a nurturing, warm cup of tea.

Curator, Roxana Marcoci: In the early 1940s Robert Oppenheimer, a physicist in charge of The Manhattan Project developed the first atomic bomb.This photograph belongs to a series that explores encounters in New Mexico between indigenous communities and the scientists who created the bomb. These two worlds collided in the home of Edith Warner, who ran a tearoom in Los Alamos.

Helen Kornblum: Oppenheimer knew Edith Warner, who lived near Santa Fe. And when he came to create the bomb at Los Alamos, he asked Edith if he could bring scientists to her home for a place away from the creation of this bomb, and he would come with them for dinner, all during the Manhattan Project.

Roxana Marcoci: By pairing two seemingly dissimilar images, Rubenstein said she hopes “to enlarge the lives of ordinary people, and strip the mythic characters of history down to their ordinariness.”

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Edith Warner (1893-1951), also known by the nickname “The Woman at Otowi Crossing”, was an American tea room owner in Los Alamos, New Mexico, who is best known for serving various scientists and military officers working at the Los Alamos National Laboratory during the original creation of the atomic bomb as a part of the Manhattan Project. Warner’s influence on the morale and overall attitude of the people there has been noted and written about by various journalists and historians, including several books about her life, a stage play, a photography exhibition, an opera, and a dance.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Rosemarie Trockel (German, b. 1952)

Untitled

2004

Chromogenic print

20 3/4 × 19″ (52.7 × 48.3 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Tatiana Parcero (Mexican, b. 1967)

Interior Cartography #35

1996

Chromogenic print and acetate

9 3/8 × 6 3/16 in. (23.8 × 15.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Artist, Tatiana Parcero

My name is Tatiana Parcero. I’m from Mexico and I’m a visual artist and a psychologist. The work is called Interior Cartography #35, and belongs to the series of the same name.

Cartography is a science that deals with maps. I am interested in working with the body as a territory, where I can explore different paths at a physical and also in a symbolic level.

I am the one that appears in all the photographs. When I did this specific shot, I wanted to show a moment of introspection and calm. And when you see my hands near my cheeks, I wanted to represent a way to be in touch with myself, not just in a physical way, but in a more spiritual way.

The image superimposed on the face is from the Codex Tudela of the 16th century. The codices are documents that were created by ancient civilisations, like Mayans, Aztecs, that represent the pre-Columbian cultures of Mexico, their amazing universe, and the way that they lived.

When I moved to New York from Mexico, I was feeling a little bit out of place and I wanted to recreate a sense of belonging. The work is a way to connect myself with my country and the ancient cultures that are before me.

I decided to study psychology because I wanted to help people. I wanted to be able to understand emotions and be able to translate personal experiences into images and make them more accessible. It’s important for me to give the viewer several layers so that you can really explore the image and make your own interpretations and reflections. I think art can transform you and take you to a parallel universe. That is where I feel that you can be able to heal and to cure.

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Lorie Novak (American, b. 1954)

Self-Portraits

1987

Chromogenic print

22 1/2 × 18 9/16″ (57.2 × 47.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

The Museum of Modern Art announces Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum, an exhibition that will present 90 photographic works by female artists from the last 100 years, on view from April 16 to October 2, 2022. Drawn exclusively from the Museum’s collection, thanks to a transformative gift of photographs from Helen Kornblum in 2021, the exhibition takes as a starting point the idea that the histories of feminism and photography have been intertwined. Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum is organised by Roxana Marcoci, The David Dechman Senior Curator, with Dana Ostrander, Curatorial Assistant, and Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, MoMA.

Rather than presenting a chronological history of women photographers or a linear account of feminist photography, the exhibition prompts new appraisals and compelling dialogues from a contemporary, intersectional feminist perspective. African-diasporic, queer, and postcolonial / Indigenous artists have brought new mindsets and questions to the canonical narratives of art history. Our Selves will reexamine a host of topics, countering racial and gender invisibility, systemic racial injustice, and colonialism, through a diversity of photographic practices, including portraiture, photojournalism, social documentary, advertising, avant-garde experimentation, and conceptual photography. Highlighting both iconic and rare or lesser-known images, the exhibition’s groupings and juxtapositions of modern and contemporary works will encourage unexpected connections in the Museum’s fifth-floor collection galleries, which are typically devoted to art from the 1880s through the 1940s.

Our Selves will open with a wall of self-portraits and portraits of female artists by such modernist photographers as Lola Álvarez Bravo, Gertrud Arndt, Lotte Jacobi, and Lucia Moholy, alongside contemporary practitioners including Tatiana Parcero, Rosemarie Trockel, and Lorie Novak. Inviting viewers to consider the structural relationship between knowledge and power, Frances Benjamin Johnston’s Penmanship Class (1899) – a depiction of racially segregated education at the turn of the 20th century in the United States – will hang near Candida Höfer’s Deutsche Bucherei Leipzig IX (1997) – a part of Höfer’s series documenting library interiors weighted by forms of social inequality and colonial supremacy. Lorna Simpson’s Details (1996), a portfolio of 21 found photographs, signals how both the camera and language can culturally inscribe the body and reinforce racial and gender stereotypes.

Works by Native artists including Cara Romero and Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, and non-Native practitioners such as Sharon Lockhart and Graciela Iturbide, explore indigeneity and its relationship to colonial history. Photographs by Flor Garduño, Ana Mendieta, Marta María Pérez Bravo, and Mariana Yampolsky attest to the overlapping histories of colonialism, ethnographic practice, and patriarchy in Latin America.

Our Selves is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue that features more than 100 colour and black-and-white photographs. A critical essay by curator Roxana Marcoci asks the question, “What is a Feminist Picture?” and a series of 12 focused essays by Dana Ostrander, Caitlin Ryan, and Phil Taylor address a range of themes, from dance to ecology to perception. The catalogue offers both historical context and critical interpretation, exploring the myriad ways in which different photographic practices can be viewed when looking through a feminist lens.

Press release from the MoMA website

Installation view of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

The images below before the next installation image are left to right in the above installation image.

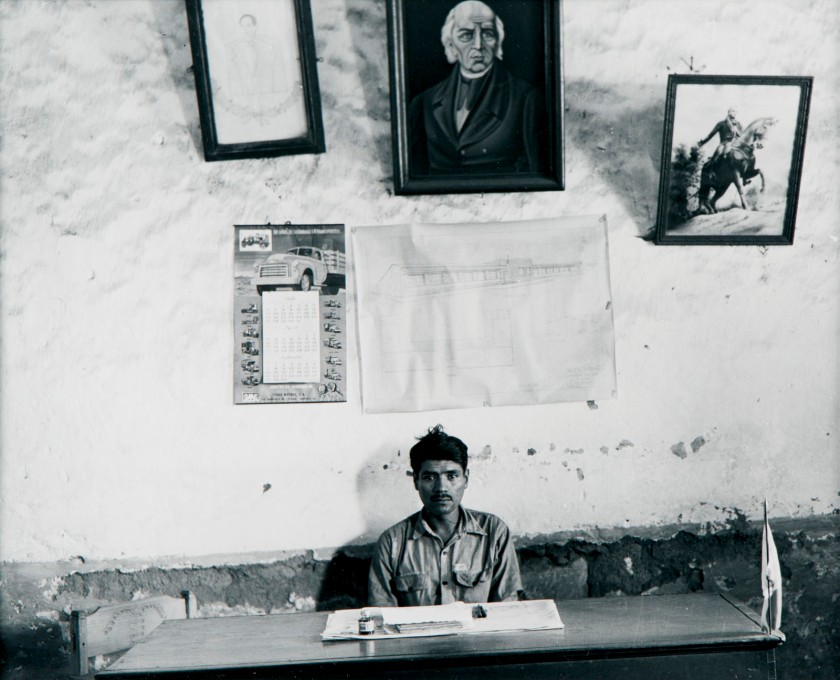

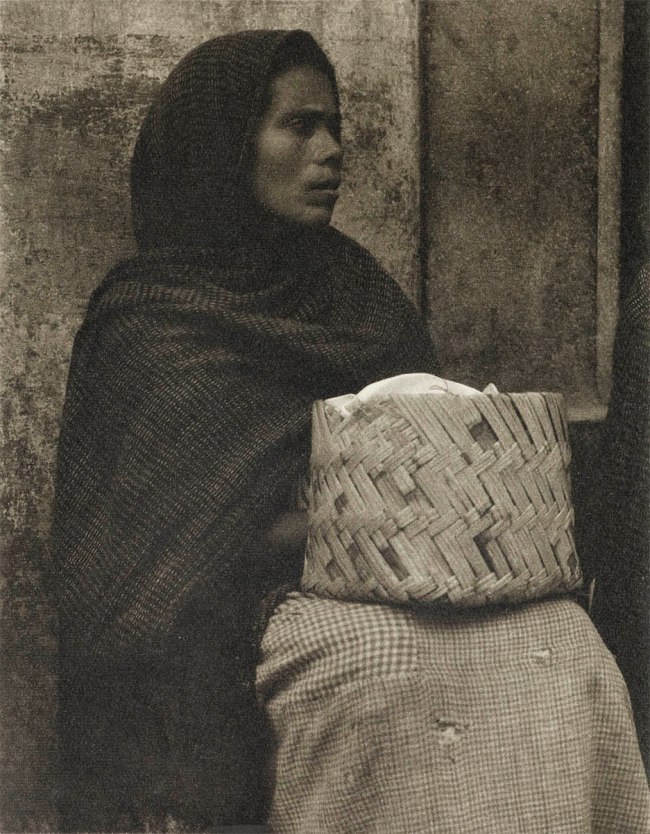

Graciela Iturbide (Mexican, b. 1943)

Mujercita

1981

Gelatin silver print

10 1/8 × 6 3/4″ (25.7 × 17.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

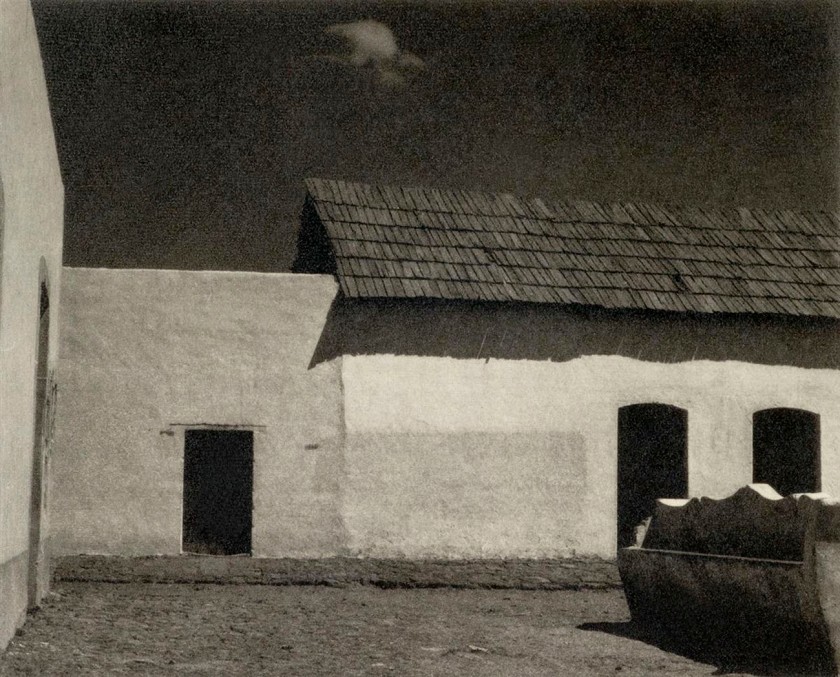

Mariana Yampolsky (Mexican, 1925-2002)

Mujeres Mazahua

1989

Gelatin silver print

13 5/8 × 18 1/2″ (34.6 × 47cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

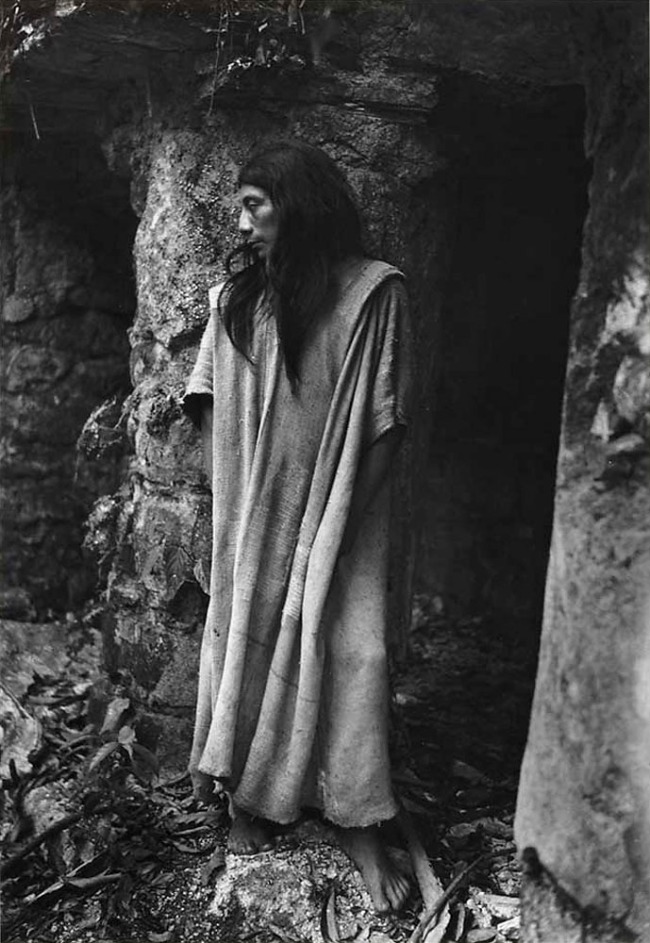

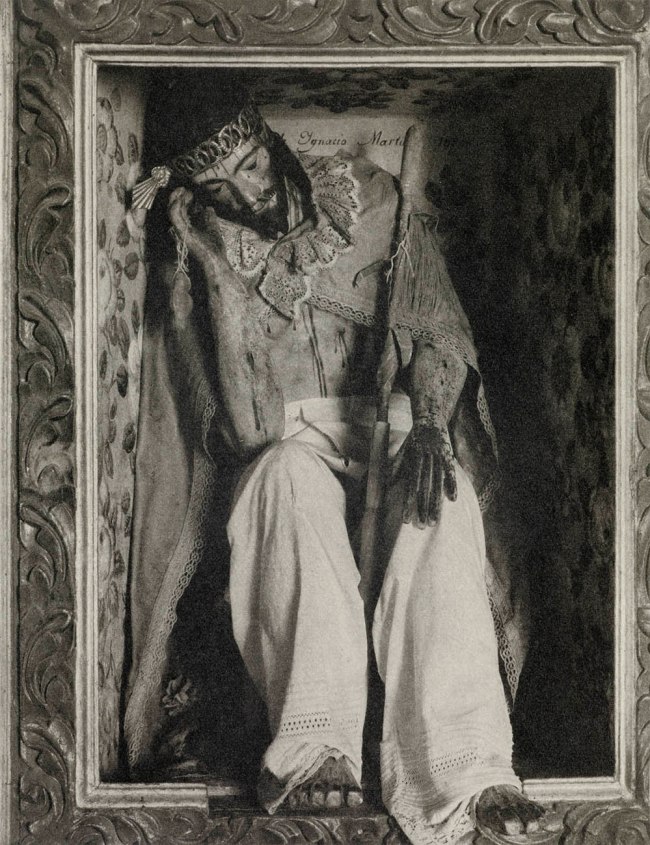

Flor Garduño (Mexican, b. 1957)

Reina (Queen)

1989

Gelatin silver print

12 1/4 × 8 3/4″ (31.1 × 22.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Barbara Morgan (American, 1900-1992)

Corn Stalks Growing

1945

Gelatin silver print

12 3/16 × 9″ (31 × 22.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Sonya Noskowiak (American born Germany, 1900-1975)

Plant Detail

1931

Gelatin silver print

9 11/16 × 7 1/2″ (24.6 × 19.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976)

Agave Design I

1920

Gelatin silver print

12 7/8 × 9 13/16″ (32.7 × 24.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Florence Henri (Swiss born United States, 1893-1982)

Composition Nature Morte

1931

Gelatin silver print

3 3/8 × 4 1/2″ (8.6 × 11.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989)

Eucalyptus Leaves

1933

Gelatin silver print

12 × 9″ (30.5 × 22.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

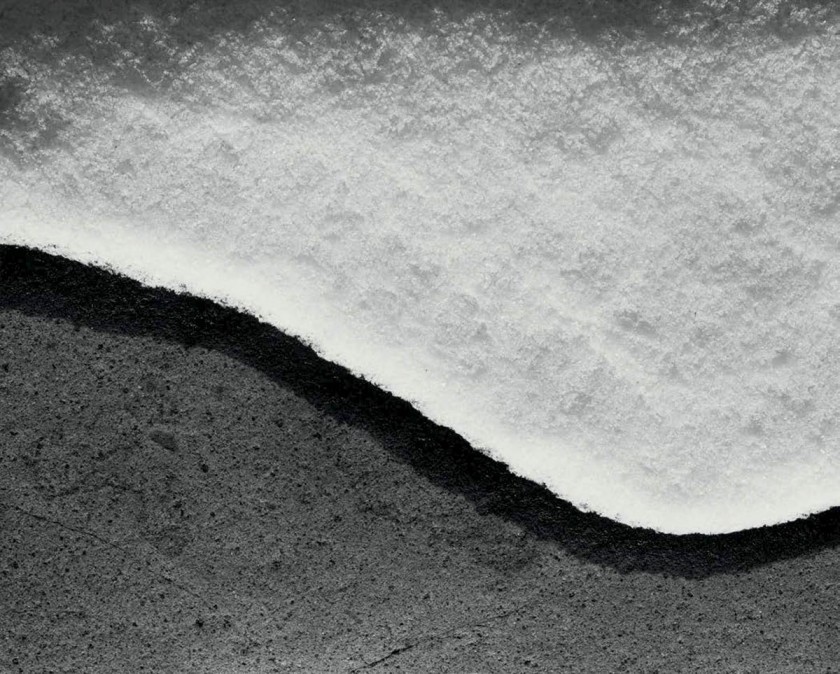

Ruth Bernhard (American born Germany, 1905-2006)

Angel Wings

1943

Gelatin silver print

9 5/8 × 6 1/4″ (24.4 × 15.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Nelly (Elli Sougioultzoglou-Seraidari) (Greek born Turkey, 1899-1998)

Elizaveta “Lila” Nikolska in the Parthenon, Athens, Greece

November 1930

Gelatin silver print

6 × 8 1/2″ (15.2 × 21.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Installation view of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The images below before the next installation image are left to right in the above installation image.

Laurie Simmons (American, b. 1949)

Three Red Petit-Fours

1990

Chromogenic print

23 × 35″ (58.4 × 88.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Kati Horna (Mexican, 1912-2000)

Figurines

c. 1933

Gelatin silver print

8 1/2 × 8″ (21.6 × 20.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Dora Maar (French 1907-1997)

Mannequin in Window

1935

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 × 6″ (24.1 × 15.2 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Inge Morath (Austrian, 1923-2002)

Siesta of a Lottery Ticket Vendor, Plaza Mayor, Madrid

1955

Gelatin silver print

7 3/16 × 4 3/4″ (18.3 × 12.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Ringl + Pit (German)

Grete Stern (Argentine born Germany, 1904-1999)

Ellen Auerbach (German, 1906-2004)

Columbus’ Egg

1930

Gelatin silver print

8 3/4 × 7 1/2″ (22.2 × 19.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Yva (Else Ernestine Neuländer) (German, 1900-1942)

Untitled

1935

Gelatin silver print

9 1/16 × 6 11/16″ (23 × 17cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Marie Cosindas (American, 1923-2017)

Masks, Boston

1966

Dye transfer print

10 × 7″ (25.4 × 17.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Kati Horna (Mexican, 1912-2000)

Man and Candlesticks

c. 1933

Gelatin silver print

8 × 7 3/4″ (20.3 × 19.7cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Barbara Probst (German, b. 1964)

Exposure #78, NYC, Collister and Hubert St.

2010

Two inkjet prints (diptych)

18 3/4 × 28″ (47.6 × 71.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Barbara Probst (German, b. 1964)

Artist, Barbara Probst: I am Barbara Probst. I’m an artist working with photography. I’m born in Munich, in Germany, and I live in New York.

I’m interested in photography as a phenomenon that seemingly and supposedly depicts reality. But maybe it is the subjectivity of the photographer, which determines the image. And not the objectivity of the world.

I get a set of pictures from the same moment. By comparing these pictures, it becomes quite clear that the link between reality and photography is very thin and fragile because every picture from this moment gives a different take of this moment.

None of these images is more true or more false than any others. They are equally truthful. The viewpoints and angles and settings of the cameras and the framing and all these things determine the picture.

It’s not what is in front of the camera that determines the picture. It’s the photographer behind the camera that decides how reality is translated into an image.

Audio of Barbara Probst from the video “Elles X Paris Photo: Barbara Probst.” © Fisheye l’Agence 2021

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Installation view of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The images below before the next installation image are left to right in the above installation image.

Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953)

Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Makeup)

1990

Gelatin silver print

27 3/16 × 27 3/16″ (69.1 × 69.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

“My work endlessly explodes the limits of tradition.”

Carrie Mae Weems

What does it mean to bear witness to history? The artist Carrie Mae Weems has asked this question for decades through photography, video, performance, installation, and social practice. For Weems, to examine the past is to imagine a different future. “In one way or another, my work endlessly explodes the limits of tradition,” she declared in an interview with her friend, the photographer Dawoud Bey. “I’m determined to find new models to live by. Aren’t you?”1

Weems was trained as both a dancer and a photographer before enrolling in the folklore studies program at the University of California, Berkeley, in the mid-1980s, where she became interested in the observation methods used in the social sciences. In the early 1990s, she began placing herself in her photographic compositions in an “attempt to create in the work the simultaneous feeling of being in it and of it.”2 She has since called this recurring figure an “alter-ego,” “muse,” and “witness to history” who can stand in for both the artist and audience. “I think it’s very important that as a Black woman she’s engaged with the world around her,” Weems has said, “she’s engaged with history, she’s engaged with looking, with being. She’s a guide into circumstances seldom seen.”3

In her 1990 Kitchen Table series – 20 gelatin silver prints and 14 texts on silkscreen panels – Weems uses her own persona to “respond to a number of issues: woman’s subjectivity, woman’s capacity to revel in her body, and the woman’s construction of herself, and her own image.”4 Weems, or rather her protagonist, inhabits the same intimate domestic interior throughout the series. Anchored around a wooden table illuminated by an overhead light, scenes such as Untitled (Man smoking) and Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Makeup) portray the protagonist alongside a rotating cast of characters (friends, children, lovers) and props (posters, books, playing cards, a birdcage). In Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Makeup), for example, the woman sits at the table with a young girl; they gaze into mirrors at their own reflections, applying lipstick in parallel gestures. The photograph shows that gender is a learned performance, at the same time tenderly centering its Black women subjects.

With projects such as From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995), the act of witnessing is suggested in the first-person title. The J. Paul Getty Museum commissioned the work in 1994, inviting the artist to respond to 19th-century photographs of African American subjects collected by the lawyer Jackie Napoleon Wilson. In 28 chromogenic photographic prints overlaid with text on glass, Weems appropriated images from a variety of sources: Wilson’s collection, museum and university archives, The National Geographic, and the work of photographers like Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Garry Winogrand. The artist cropped and reformatted these photographs, adding blue and red tints, text, and circular mats resembling a camera lens. Through this reframing, Weems poses a question about power: Who is doing the looking, and for what reasons?

Among the rephotographed images are four daguerreotypes by photographer J. T. Zealy of enslaved men and women – two father-and-daughter pairs, named Renty, Delia, Jack, and Drana – commissioned as racial types by Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz in 1850. Weems exposes Agassiz’s racist pseudoscience and the violence of the white Anglo-American gaze through the addition of texts that address the subjects: “You became a scientific profile,” “a negroid type,” “an anthropological debate,” “& a photographic subject.” Discussing the daguerreotypes, the artist has described the sitters as agents of resistance and refusal: “In their anthropological way, most of these photographs were meant to strip the subjects of their humanity. But if you look closely, what you see is the evidence of a contest of wills over contested territory, contested terrain – contested by the by the owner of the Black body and the photographer’s attempt to conquer it vis-à-vis the camera.”5

Caitlin Ryan, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, 2021

1/ “Carrie Mae Weems by Dawoud Bey,” BOMB, July 1, 2009, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/carrie-mae-weems/

2/ Ibid.

3/ Ibid.

4/ Weems, quoted in Carrie Mae Weems: The Kitchen Table Series (Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, 1996), 6.

5/ Weems to Deborah Willis, “In Conversation with Carrie Mae Weems,” in To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes, eds. Ilisa Barbash, Molly Rogers, and Deborah Willis (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum Press; New York, NY: Aperture, 2020), 397.

Curator, Roxana Marcocci: We’re looking at a photograph from Carrie Mae Weems’s larger body of work, the Kitchen Table series.

Artist, Carrie Mae Weems: About 1990, I think, I had been really thinking a lot about what it meant to develop your own voice. And so I made this body of work.

It started as a kind of response to my sense of what needed to happen, what needed to be and these ideas about the sort of spaces of domesticity that have historically belonged to women.

Roxana Marcoci: In this image, Weems applies makeup in front of a mirror while a young girl seated in front of another mirror, puts on lipstick and looks at her own reflection. The two enact beauty in a synchronised performance, through posing, mirroring, and self-empowerment.

Carrie Mae Weems: I made them all in my own kitchen, using a single light source hanging over the kitchen table. It just swung open this door of what I could actually do in my own environment. What I’m suggesting really is that the battle around the family, the battle around monogamy, the battle around polygamy, the social dynamics that happens between men and women, that war gets carried on in that space.

The Kitchen Table series would not be simply a voice for African-American women, but more generally for women.

Audio of Carrie Mae Weems in the Art21 digital series Extended Play, “Carrie Mae Weems / ‘The Kitchen Table Series.'” © Art21, Inc. 2011

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Cara Romero (Native American (Chemehuevi), b. 1977)

Wakeah

2018

Inkjet print

52 × 44″ (132.1 × 111.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Artist, Cara Romero: My name is Cara Romero, and this photograph is called Wakeah.

The inspiration for the First American Girl series was a lifetime of seeing Native American people represented in a dehumanised way. My daughter was born in 2006 and I really wanted her self image to be different. But all of the dolls that depict Native American girls were inaccurate. They lacked the detail. They lacked the love. They lacked the historical accuracy. So the series began with Wakeah.

Wakeah is Wakeah Jhane Myers and she is an incredible artist in her own right. She descends from both the Kiowa and Comanche tribes of Oklahoma. We posed Wakeah in the doll box much like you would find on the store shelves, placing all of her cultural accoutrement around her. She is wearing a traditional Southern Buckskin dress. She has a change of moccasins and her fan that she uses in dance. A lot of people ask me about the suitcase, and this is an inside joke between Native people, many of us carry our regalia in a suitcase as a way to keep it safe.

It took five family members over a year to make her regalia that she wears to compete at the pow wow dance. These contemporary pieces of regalia are really here against all odds. They exist through activism, through resistance.

A lot of what I’m doing is constructing these stories about resisting these ideas of being powerless, of being gone. Instead, I’m constructing a story of power and of knowledge and of presence. I want the viewer to fall in love. I want them to see how much I love the people that I’m working with.

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

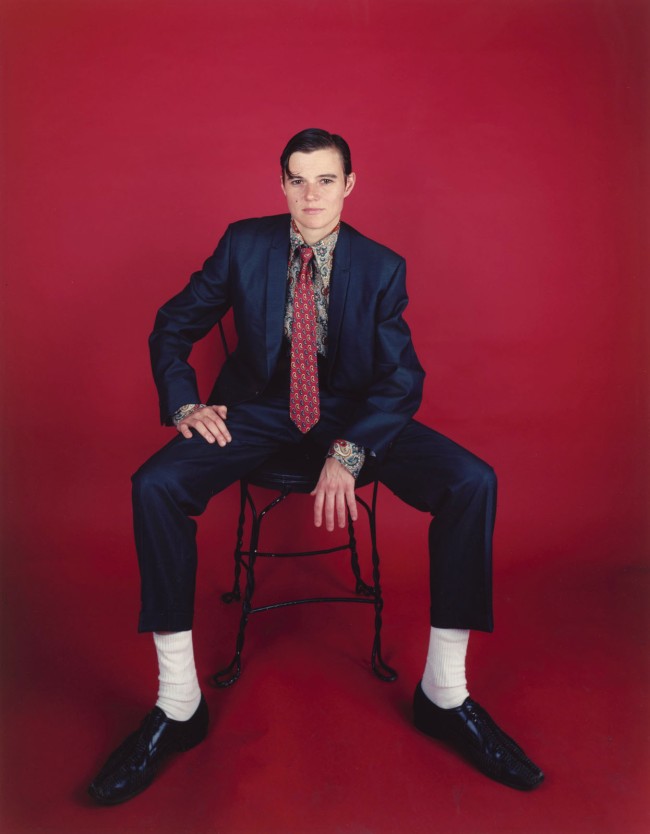

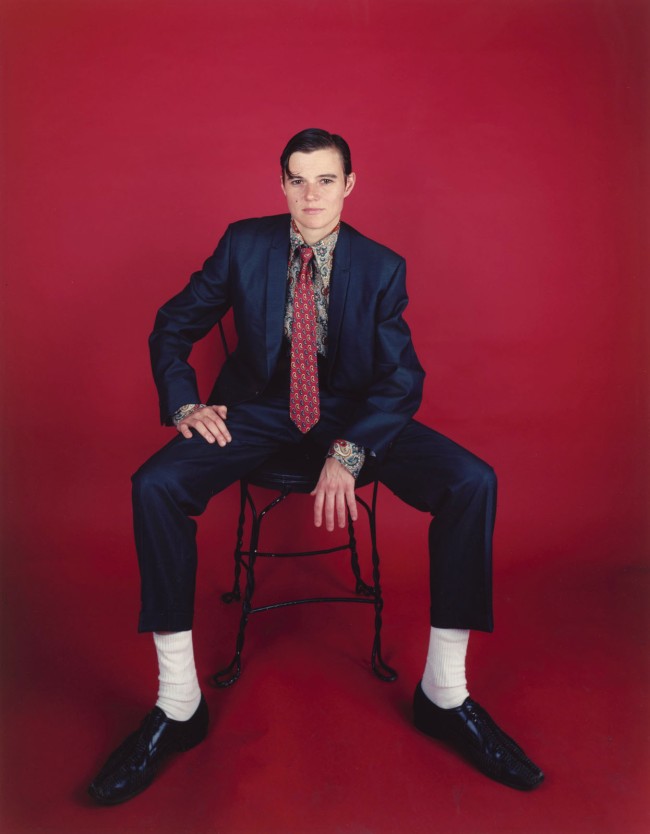

Catherine Opie (American, b. 1961)

Angela Scheirl

1993

Silver dye bleach print

19 5/16 × 15″ (49.1 × 38.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Louise Lawler (American, b. 1947)

Sappho and Patriarch

1984

Silver dye bleach print

39 3/4 × 27 1/2″ (101 × 69.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Installation view of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The images below before the next installation image are left to right in the above installation image.

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Deutsche Bücherei Leipzig IX

1997

C-print

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Sharon Lockhart (American, b. 1964)

Untitled

2010

Chromogenic print

37 × 49″ (94 × 124.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Installation view of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The images below are left to right in the above installation image.

Mary Ellen Mark (American, 1940-2015)

Tiny, Halloween, Seattle

1983

Gelatin silver print

Image: 13 5/16 × 9″ (33.8 × 22.9cm)

Sheet: 14 × 11″ (35.6 × 27.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Mother and Child, San Joaquin Valley

1938

Gelatin silver print

7 × 9 1/2″ (17.8 × 24.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Anne Noggle (American, 1922-2005)

Shirley Condit de Gonzales

1986

Gelatin silver print

18 1/8 × 13″ (46 × 33cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Nell Dorr (American, 1893-1988)

Mother and Child

1940

Gelatin silver print

13 15/16 × 10 13/16″ (35.4 × 27.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

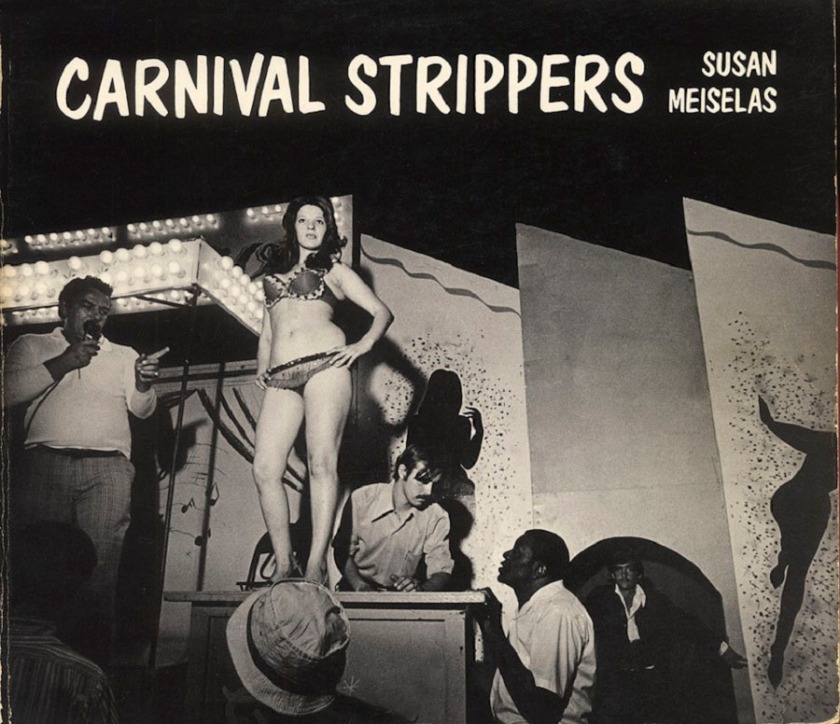

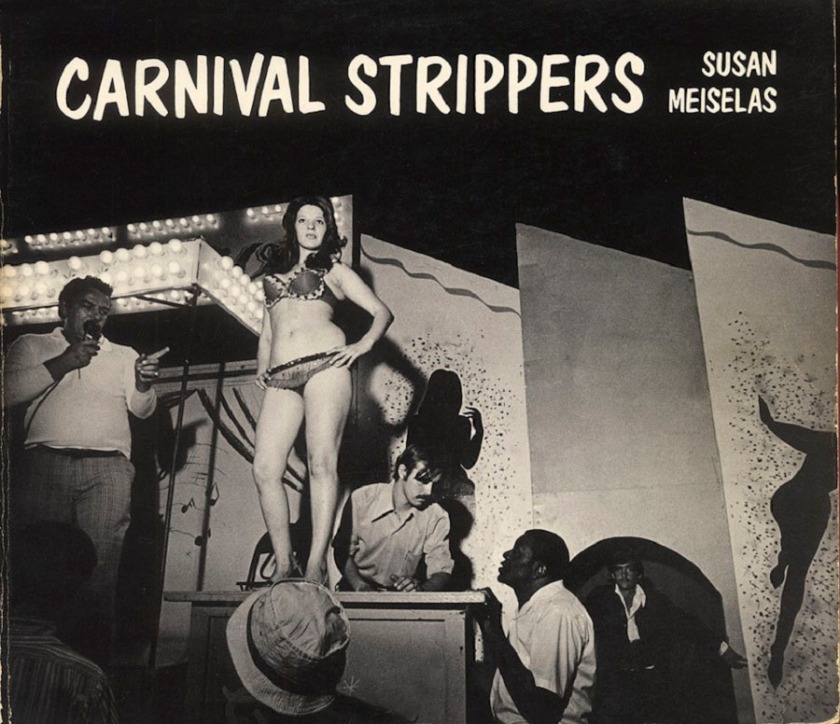

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Carnival Strippers

1976

New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Tentful of Marks, Tunbridge, Vermont

1974, printed c. 2000

Gelatin silver print

7 11/16 × 11 3/4″ (19.5 × 29.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Wary of photography’s power to shape our understanding of social, political and global issues and of the potentially complex ethical relationship between photographer and subject, Susan Meiselas has developed an immersive approach through which she gets to know her subjects intimately. Carnival Strippers is among her earliest projects and the first in which she became accepted by the community she was documenting. Over the summers of 1972 to 1975, she followed an itinerant, small-town carnival, photographing the women who performed in the striptease shows. She captured not only their public performances, but also their private lives. To more fully contextualise these images, Meiselas presents them with audio recordings of interviews with the dancers, giving them voice and a measure of control over the way they are presented.

Additional text from “Seeing Through Photographs online course”, Coursera, 2016

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Artist, Susan Meiselas: My name is Susan Meiselas. I’m a photographer based in New York.

Carnival Strippers is my first real body of work. The idea of projecting a self to attract a male gaze was completely counter to my sense of culture, what I wanted for myself. So I was fascinated by women who were choosing to do that. I just felt, magnetically, I need to know more.

The feminists of that period were perceiving the girl shows as exploitative institutions that should be closed down. I actually was positioned in the place of feeling these voices should be heard. They should self-define as to who they are and what their economic realities are.

Getting to know the women was very much one by one, obviously I’m in the public fairgrounds making this photograph so there are many other people surrounding me. There weren’t many other cameras. I mean, if we were making this picture today, it’s interesting the differences of how many people would have been with cameras, iPhones, etc. So I don’t think she’s performing for me. She’s performing for the public.

The girl show moves around from town to town. My working process was to be somewhere on a weekend, go back to Boston, which at the time was my base, and process the work and bring back the contact sheets and show whoever was there the following weekend, what the pictures were. And they left little initials saying, I like this one, I don’t like that one.

This negotiated or collaborative space with photography really still fascinates me. It’s a kind of offering, it’s a moment in which someone says, I want you to be here with us. The challenge of making that moment, creating that moment, that’s what still intrigues me, I think, and keeps me engaged with photography.

Transcript of audio from the MoMA website

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

Traditional mask used in the popular insurrection, Monimbo, Nicaragua

1978

Chromogenic print

23 1/2 × 15 3/4″ (59.7 × 40cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Traditional Indian dance mask from the town of Monimbó, adopted by the rebels during the fight against Somoza to conceal identity, Nicaragua

Susan Meiselas (American, b. 1948)

A Funeral Procession in Jinotepe for Assassinated Student Leaders. Demonstrators Carry a Photograph of Arlen Siu, an FSLN Guerilla Fighter Killed in the Mountains Three Years Earlier

1978

Chromogenic print

15 3/8 × 23 1/4″ (39.1 × 59.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

“The camera…gives me both a point of connection and a point of separation.”

Susan Meiselas

“The camera is an excuse to be someplace you otherwise don’t belong,” said the photographer Susan Meiselas. “It gives me both a point of connection and a point of separation.” Meiselas studied anthropology before turning to teaching and photography, and her photographic work has remained firmly rooted in those early interests.

Beginning in 1972, Meiselas spent three consecutive summers documenting women who performed stripteases as part of itinerant, small-town carnivals throughout New England. She not only photographed them at work and during their down time, but she made audio recordings of interviews she conducted with the dancers (and the men who surrounded them), to add context and give her subjects a voice. Meiselas later reflected, “The feminists of that period were perceiving the girls’ shows as exploitative institutions that should be closed down, and so I actually was positioned in the place of feeling these voices should be heard, they should self-define as to who they are and what their economic realities are.”1 Meiselas travelled with the dancers from town to town, eventually becoming accepted by the community of women. This personal connection comes across in the intimacy of the scenes. Her photo book Carnival Strippers2 was published in 1976, the same year that Meiselas was invited to join the international photographic cooperative Magnum Photos.

Over the last 50 years, Meiselas has remained dedicated to getting to know her subjects, and she maintains relationships with them, sometimes returning to photograph them decades after the initial project. One place she has photographed again and again is Nicaragua, starting with the burgeoning Sandinista revolution. From June 1978 to July 1979, she documented the violent end of the regime of dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. In 1990 she returned to the country with her book of photographs made at that time, Nicaragua3, and used it as a tool to track down as many subjects of those photographs as she could: “Now I want to retrace my steps, to go back to the photos I took at the time of the insurrection, and search for the people in them. What brought them to cross my path at the moment they did? What’s happened to them since? What do they think now? What do they remember?”4 She gathered their testimonies and co-directed a film, Pictures from a Revolution 5, that explored the Nicaraguan people’s hardships after the revolution. She went back to Nicaragua yet again in 2004, on the 25th anniversary of Somoza’s overthrow, and worked with local communities to install murals of her photographs on the sites where they were taken.6 It is the job of a photojournalist to bear witness, but Meiselas also considers ways in which she can challenge and confront future communities with the scenes she has witnessed.

In 1997, Meiselas completed a six-year-long project about the photographic history of the Kurds, working to piece together a collective memory of people who faced extreme displacement and destruction. She gathered these memories in a book – Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History7 – an exhibition and an online archive that can still be added to today. Throughout this project Meiselas worked with both forensic and historical anthropologists who added their own specialised context; the innumerable oral accounts from the Kurdish people themselves provide a perspective often left out of history books.

Referring to her early studies in anthropology, Meiselas said, “Those very primary experiences of diversity led me to be more curious about the world, putting me into a certain mode of exploration and openness to difference at a young age.” She has long understood the importance of giving a voice to her often little-known and marginalised subjects, and through her work she draws attention to a wide variety of human rights and social justice issues. Meiselas constantly considers the challenging relationship between photographer and subject, and the relationship of images to memory and history, always looking for new cross-disciplinary and collaborative ways to evolve the medium of documentary storytelling.

Jane Pierce, Carl Jacobs Foundation Research Assistant, Department of Photography

1/ The Museum of Modern Art, New York, “Seeing Through Photographs,” YouTube video, 5:03. February 13, 2019 https://youtu.be/HHQwAkPj8Bc

2/ Susan Meiselas, Carnival Strippers (New York: Noonday Press, 1976) and a revised second edition with bonus CD (New York: Steidl, 2003).

3/ Susan Meiselas, Nicaragua (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981).

4/ Susan Meiselas, Alfred Guzzetti and Richard P. Rogers, Pictures from a Revolution, DVD (New York: Kino International Corp., 1991).

5/ Susan Meiselas, Alfred Guzzetti, and Richard P. Rogers, Pictures from a Revolution, DVD (New York: Kino International Corp., 1991).

6/ Susan Meiselas, Alfred Guzzetti, and Pedro Linger Gasiglia, Reframing History, DVD (2004).

7/ Susan Meiselas, Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History (New York: Random House, 1997).

Frances Benjamin Johnston (American, 1864-1952)

Penmanship Class

1899

Platinum print

7 3/8 × 9 3/8 in. (18.7 × 23.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Helen Kornblum in honour of Roxana Marcoci

Frances Benjamin Johnston (American, 1864-1952)

After setting up her own photography studio in 1894, in Washington, D.C., Frances Benjamin Johnston was described by The Washington Times as “the only lady in the business of photography in the city.”1 Considered to be one of the first female press photographers in the United States, she took pictures of news events and architecture and made portraits of political and social leaders for over five decades. From early on, she was conscious of her role as a pioneer for women in photography, telling a reporter in 1893, “It is another pet theory with me that there are great possibilities in photography as a profitable and pleasant occupation for women, and I feel that my success helps to demonstrate this, and it is for this reason that I am glad to have other women know of my work.”2

In 1899, the principal of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia commissioned Johnston to take photographs at the school for the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The Hampton Institute was a preparatory and trade school dedicated to preparing African American and Native American students for professional careers. Johnston took more than 150 photographs and exhibited them in the Exposition Nègres d’Amerique (American Negro Exhibit) pavilion, which was meant to showcase improving race relations in America. The series won the grand prize and was lauded by both the public and the press.

Years later, writer and philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein discovered a leather-bound album of Johnston’s Hampton Institute photographs. He gave the album to The Museum of Modern Art, which reproduced 44 of its original 159 photographs in a book called The Hampton Album, published in 1966. In its preface, Kirstein acknowledged the conflict inherent in Johnston’s images, describing them as conveying the Institute’s goal of assimilating its students into Anglo-American mainstream society according to “the white Victorian ideal as criterion towards which all darker tribes and nations must perforce aspire.”3 The Hampton Institute’s most famous graduate, educator, leader, and presidential advisor Booker T. Washington, advocated for black education and accommodation of segregation policies instead of political pressure against institutionalised racism, a position criticised by anti-segregation activists such as author W. E. B. Du Bois.

Johnston’s pictures neither wholly celebrate nor condemn the Institute’s goals, but rather they reveal the complexities of the school’s value system. This is especially clear in her photographs contrasting pre- and post-Hampton ways of living, including The Old Well and The Improved Well (Three Hampton Grandchildren). In both images, black men pump water for their female family members. The old well system is represented by an aged man, a leaning fence, and a wooden pump that tilts against a desolate sky, while the new well is handled by an energetic young boy in a yard with a neat fence, a thriving tree, and two young girls dressed in starched pinafores. Johnston’s photographs have prompted the attention of artists like Carrie Mae Weems, who has incorporated the Hampton Institute photographs into her own work to explore what Weems described as “the problematic nature of assimilation, identity, and the role of education.”4

Johnston’s photographs of the Hampton Institute were only a part of her long and productive career. Having started out by taking society and political portraits, she later extensively photographed gardens and buildings, hoping to encourage the preservation of architectural structures that were quickly disappearing. Her pictures documenting the changing landscape of early-20th-century America became sources for historians and conservationists and led to her recognition by the American Institute for Architects (AIA). At a time when photography was often thought of as scientific in its straightforwardness, Johnston recognised its expressive power. As she wrote in 1897, “It is wrong to regard photography as purely mechanical. Mechanical it is, up to a certain point, but beyond that there is great scope for individual and artistic expression.”5

Introduction by Kristen Gaylord, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall Curatorial Fellow, Department of Photography, 2016

1/ “Washington Women with Brains and Business,” The Washington Times, April 21, 1895, 9.

2/ Clarence Bloomfield Moore, “Women Experts in Photography,” The Cosmopolitan XIV.5 (March 1893), 586.

3/ Lincoln Kirstein, “Introduction,” in The Hampton Album: 44 photographs by Frances B. Johnston from an album of Hampton Institute (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1966), 10.

4/ Quoted in Denise Ramzy and Katherine Fogg, “Interview: Carrie Mae Weems,” Carrie Mae Weems: The Hampton Project (New York: Aperture, 2000), 78.

5/ Frances Benjamin Johnston, “What a Woman Can Do with a Camera,” The Ladies’ Home Journal (September 1897): 6-7.

Installation views of the exhibition Our Selves: Photographs by Women Artists from Helen Kornblum at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

MoMA website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.