Exhibition dates: 6th October 2023 – 11th February 2024

Curator: Thyago Nogueira, Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil

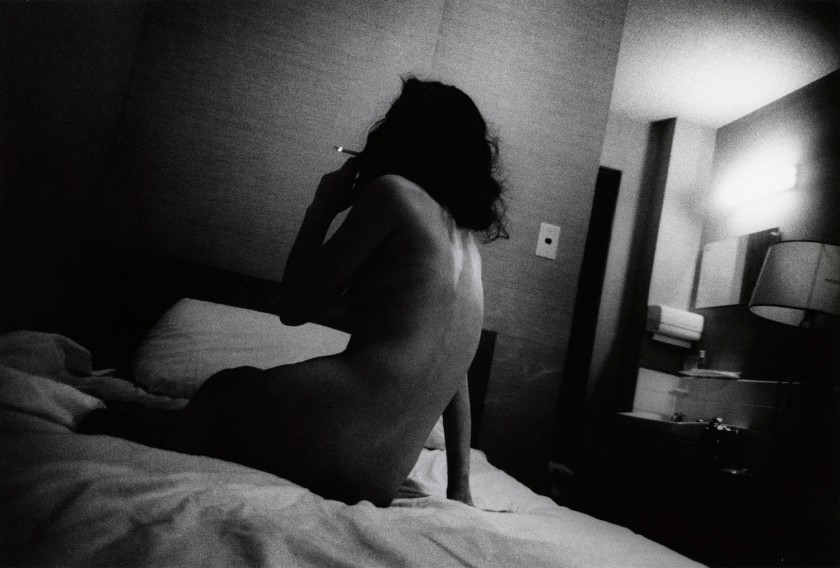

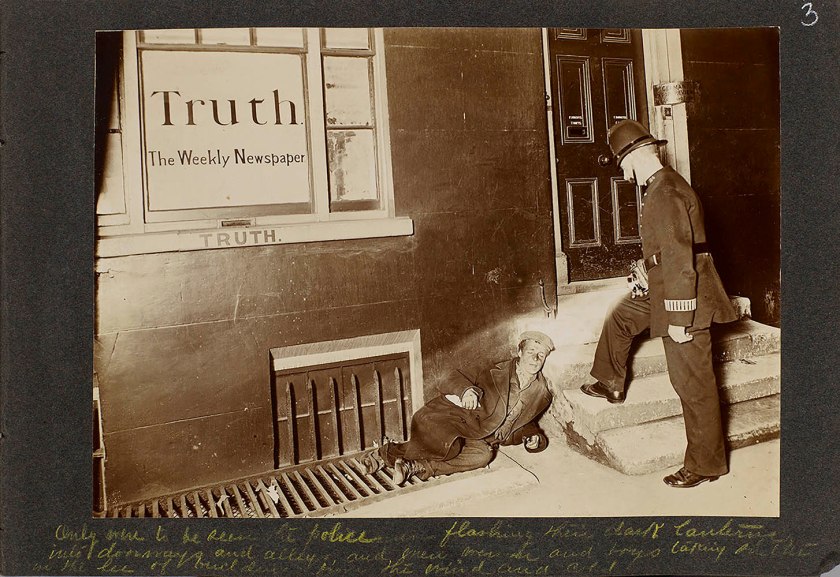

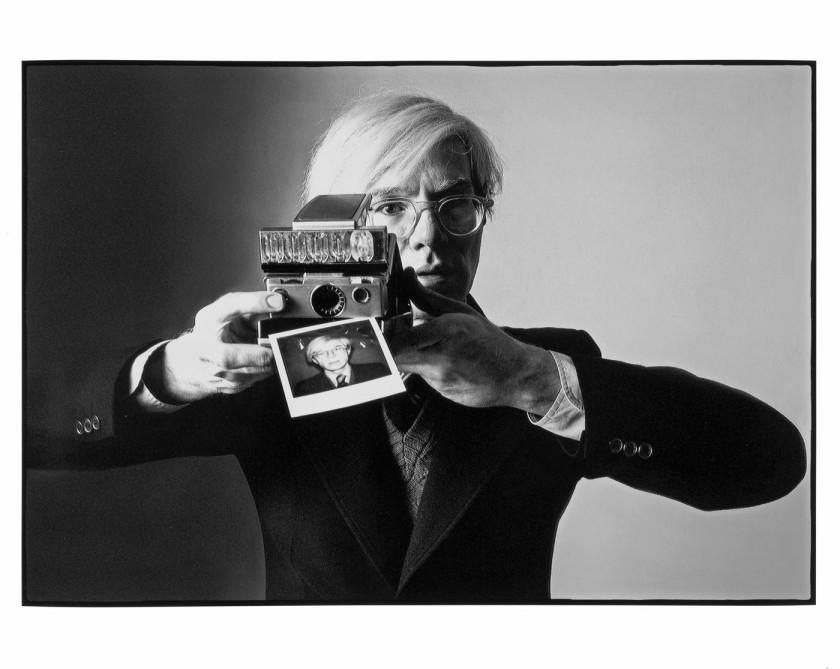

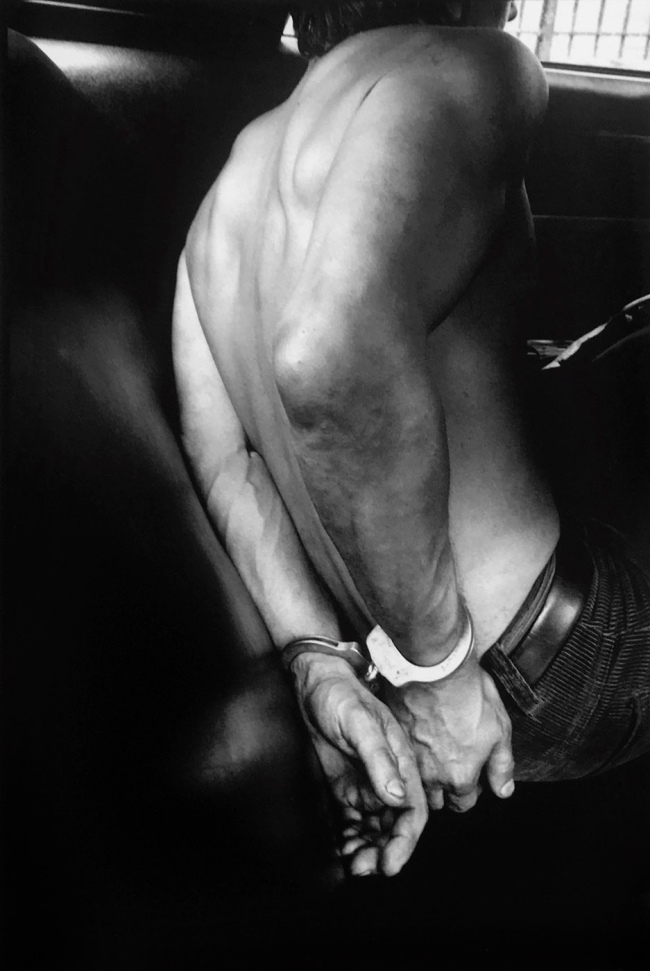

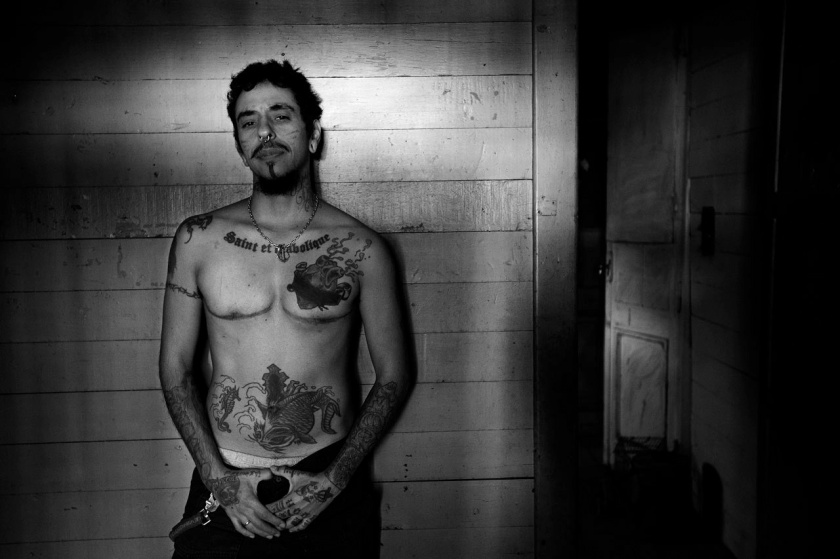

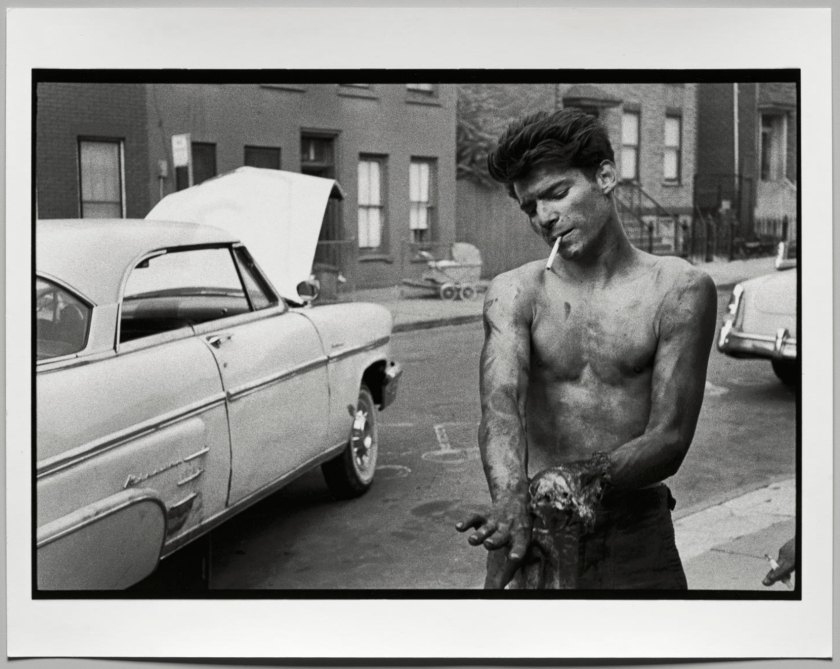

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Yokosuka

1965

From Japan, a Photo Theater

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

“We are living in a time when, to borrow a phrase and book title of Sigmund Freud’s, civilization and its discontents are becoming painfully evident to us all. Our machine age technology with its private greed, ecologically disastrous policies, crass materialism, human alienation, incessant strife and conflict, and the portent of man’s destroying himself by his own recklessness, is taking its toll in terms of our confidence and optimism about life. …

When we turn to our popular culture – which includes the arts – for diversion and meaning, we are confused, oftentimes, by the welter of contradictory impressions. We are trivialized and mesmerized by the pap that is purveyed on the television and radio, and in newspapers and magazines. We take away from our experience with these forms of entertainment a sense of having spent time but not having been taught anything or having been ennobled. We learn without understanding and visualize without seeing.”

John Anson Warner. “Introduction” to The Life & Art of the North American Indian. London: Hamlyn, 1975, p. 6.

Photography and its discontents

I love Moriyama’s early gritty, surreal, street snap style, high contrast black and white photographs. They possess a certain air, a certain essentialness, established through the artist’s unique aesthetic “famously known by the Japanese phrase ‘are, bure, boke’ (meaning ‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’).” The images are memorable and unforgettable.

I am far lest convinced by Moriyama’s contemporary photographs. His attempts to democratise the image – where he is trying to create something more automatic and where each image becomes of equal importance and meaning – leads to the collective banality of photography. As Diane Smyth observes, “I think he clearly understands that this banality, this horizontality is an essential aspect of photography.”

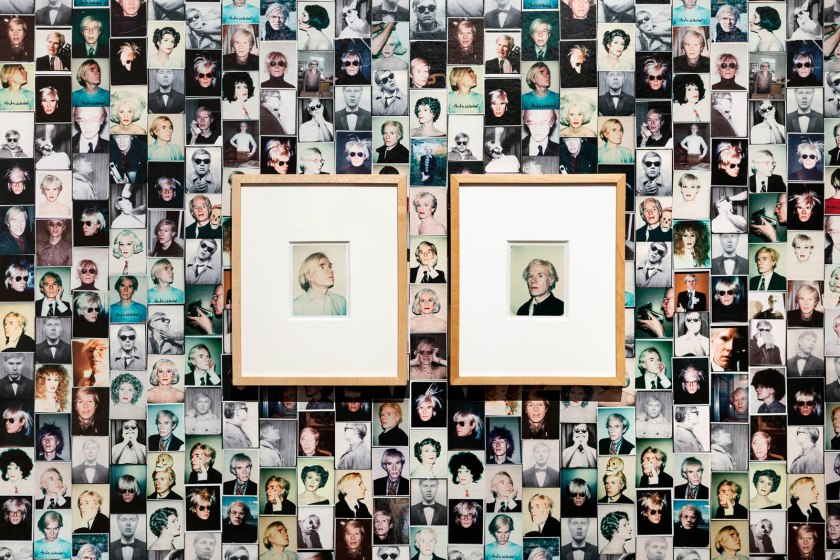

Instead of a hierarchical system of valuing significant images, Moriyama “rejected the dogmatism of art and the veneration of vintage prints, making the accessible and reproducible aspects of photography its most radical asset.” (Press release)

“Since the 1990s he has used a digital camera to make colour photographs, looking at advertisements in shopping malls and beyond. He is interested in the idea that the image is becoming more present in reality, in certain cases even substituting our reality. His work from the 2000s envelops the architecture of the gallery with vinyls, he makes huge patterns of images that go from floor to ceiling. Of course he’s anticipating our lives completely connected to screens, to these multiple virtual realities of the image which are making and in a way eliminating the real world.”2

As Paul Virlio has observed, images contaminate us like viruses. He suggests that they communicate by contamination, by infection. In our ‘media’ or ‘information’ society we now have a ‘pure seeing’; a seeing without knowing.3 Images “infiltrate our collective consciousness, touching every aspect of our lives. From the advertisements that entice us to purchase particular products, to the news coverage that shapes our understanding of current events, visual imagery surrounds us and leaves an indelible mark on our subconscious. This notion becomes particularly relevant in our increasingly digital age, where images have become the primary vehicle for communication and information dissemination… In an age where images dominate and multiply, the line between reality and its representation blurs.”4

A seeing without knowing… a democracy of the image… the banality of the photograph / photography … the line between reality and its (multiple) representations.

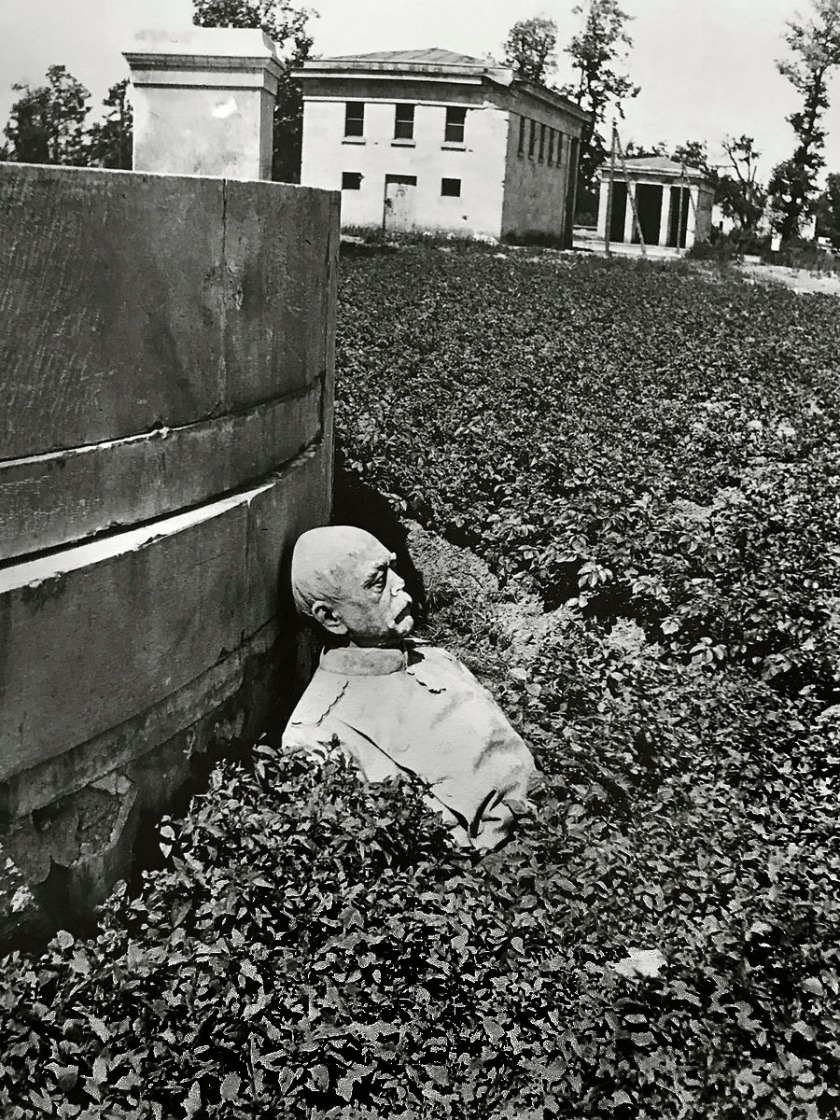

Again, I repeat that I am not convinced by Moriyama’s contemporary photographs. While I understand his investigation into contemporary photographic re/production I am not persuaded by the promiscuity nor by the profundity of his image making. If we look at the installation photographs of Moriyama’s work from Pretty Woman in this exhibition (below) where images go from floor to ceiling I struggle to make sense of this mass of information… and I will struggle to remember any of the images minutes or even seconds after seeing them. None of these photographs leaves an indelible mark on our subconscious. But perhaps that is the point (or just, my point of view).

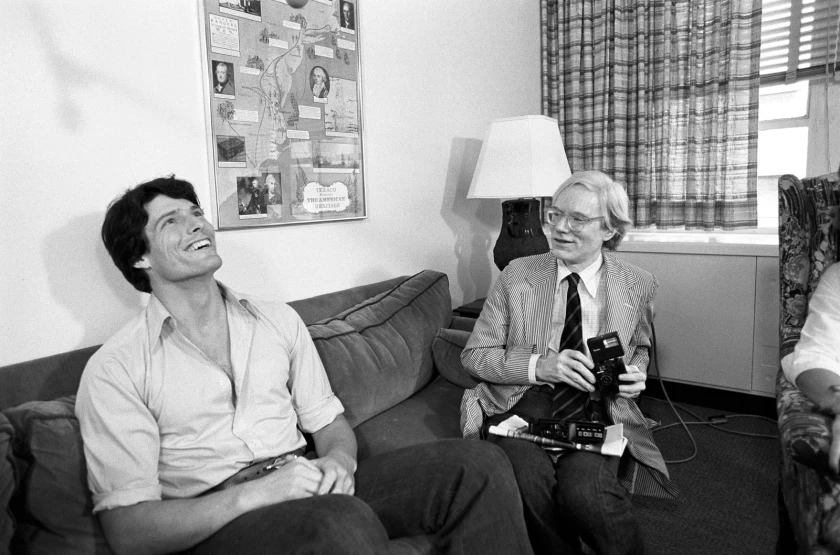

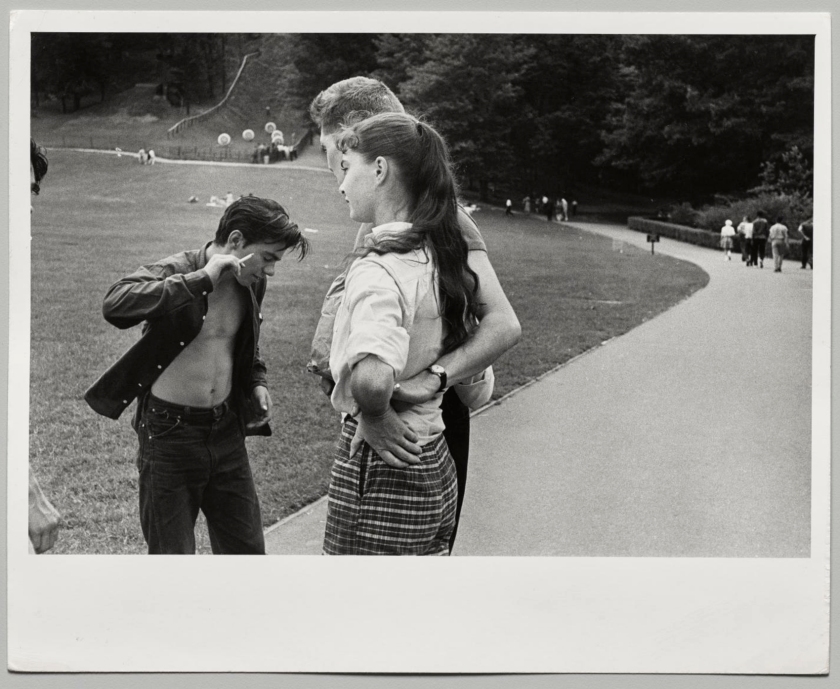

What makes Moriyama’s early photographs so remarkable is that they are memorable. We remember them because they are iconic, they have a distinctive excellence. The Stray Dog that roaming mongrel staring balefully at us; the surreal Bunuel-like opening of the eye Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, Midnight; the fleeing woman in Yokosuka (1970) so much better in black and white.

Moriyama’s black and white photographs provide “a raw, restless vision of city life and the chaos of everyday existence, strange worlds, and unusual characters.” More than that, they plunge us into a mesmerising, hypnotic world where the viewer is immersed in a fractured dream / scape / space… Strange, haunting and evocative, Moriyama’s black and white photographs project the derangement of the world onto the psyche of the viewer, producing an abnormal condition of the mind that promotes a loss of contact with reality.5 This derangement of the world, this re/arrangement of the world and the mind resonates within our subconscious, like harmonics in music. Something that a thousand thousand thousand irrelevant, inconsiderate (not examined, not remembered) photographs can never do.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Diane Smyth. “Behind the scenes of Moriyama’s London takeover,” on the British Journal of Photography website 17 October 2023 [Online] Cited 19/12/2023

2/ Paul Virilio. “The Work of Art in the Electronic Age,” in Block No. 14, Autumn, 1988, pp. 4-7 quoted in McGrath, Roberta. “Medical Police,” in Ten.8 No. 14, 1984 quoted in Watney, Simon and Gupta, Sunil. “The Rhetoric of AIDS,” in Boffin, Tessa and Gupta, Sunil (eds.,). Ecstatic Antibodies: Resisting the AIDS Mythology. London: Rivers Osram Press, 1990, p. 143

3/ Herod. “Paul Virilio: ‘Images contaminate us like viruses,” on The Socratic Method website January 2020 [Online] Cited 08/02/2024

4/ Marcus Bunyan commenting on the exhibition Fracture: Daido Moriyama at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) on the Art Blart website July 20, 2012 [Online] Cited 08/02/2024

Many thankx to The Photographers’ Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The world is a reality,

not because of the way it is,

but because

of the possibilities it presents.

Frederick Sommer

“Forget everything you’ve learned on the subject of photography for the moment, and just shoot. Take photographs – of anything and everything, whatever catches your eye. Don’t pause to think.”

“There may remain some fragments of memory still lying in the depths of my experience waiting to be awakened, and they are ready to evoke new memories at any time. Of course, I need to interpose a camera into that place.”

“To focus on reality or be concerned with memory, choices that, at first glance, seem opposite are, in fact, identical twins for me.”

Daido Moriyama

The retrospective focuses on different moments of Moriyama’s vast and productive career – beginning with his early works for Japanese magazines, interest in the American occupation, and engagement with photorealism. During this time Moriyama also established his unique aesthetic, famously known by the Japanese phrase are, bure, boke (meaning ‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’).

The second part of the exhibition picks up his work from the self-reflexive period in the 1980s and 1990s. In the decades which followed, he explored the essence of photography and of his own self, developing a visual lyricism with which he reflected on reality, memory and cities through tireless documentation and the reinvention of his own archive.

Fittingly, Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective, brings together more than 200 works and large-scale installations, as well as many of Moriyama’s rare photobooks and magazines, for the first time in the UK. One floor of the gallery has been transformed into a reading room – a dedicated space offering a rare opportunity to spend time with his legendary publications.

Text from The Photographers’ Gallery website

For more than sixty years, Daido Moriyama (森山 大道 b. 1938) has used his camera to interrogate and revolutionise the way we look at the world with his dense, grainy images. Even today, Moriyama’s pioneering artistic spirit and visual intensity remain groundbreaking.

The exhibition traces the path of a photographer who transformed the way we see photography and questioned the very nature of photography itself.

Installation views of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing at left in the bottom image, work from Farewell Photography (1972).

His 1972 photobook Farewell Photography highlights photography itself, showing edges of discarded film, flecks of dust, and sprocket holes and questioning its role as a medium.

Installation views of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing at left in the bottom image, work from Farewell Photography (1972).

Installation views of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing work from Provoke (1968-1970)

Installation view of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing work from Japan, a Photo Theater

Installation view of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024

Installation views of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing work from A Hunter

Installation view of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing covers of Record magazine top to bottom No’s 1-53

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

From Pretty Woman

Tokyo, 2017

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Installation views of the exhibition Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective at The Photographers’ Gallery, London October 2023 – February 2024 showing work from Pretty Woman

Curator Thyago Nogueira spent three years working with Moriyama on The Photographers’ Gallery retrospective

What Moriyama is really saying is that it’s in the nature of photography to be reproducible and replicable. He’s against and not interested in the veneration of artworks, he wants photography to be disseminated. It’s one of his most radical ideas. So we’re presenting plenty of pages from the magazines and books, printed, on the gallery walls and for visitors to browse, and have made videos flipping through each of his really rare books. There’s also a whole section dedicated to seeing the original books. It is going to be a very dense show. But we also wanted to break the hierarchy between a framed picture, a printed image, a wallpaper, and a vinyl. So there are all these different and very interesting kinds of images. …

In the 1960s and 70s, he was making extraordinary, beautiful images, capturing Japanese society and this ambiguous feeling towards Westernisation and the erosion of traditional Japanese culture. He was also a very interested in the nature of the language of photography, and all the possibilities that that language could offer. He started to struggle with the idea of photography being a window to the world, and started testing the materiality and the flatness of the image. He worked as a conceptual artist. He was saying, ‘There’s nothing beyond an image, this is just an image’, and to accept that was radically original and beautiful.

But he has continued to move and has become, if anything, more in tune with the times. Since the 1990s he has used a digital camera to make colour photographs, looking at advertisements in shopping malls and beyond. He is interested in the idea that the image is becoming more present in reality, in certain cases even substituting our reality. His work from the 2000s envelops the architecture of the gallery with vinyls, he makes huge patterns of images that go from floor to ceiling. Of course he’s anticipating our lives completely connected to screens, to these multiple virtual realities of the image which are making and in a way eliminating the real world.

Since 2006 he has also published a magazine called Record, where he is photographing every day non-stop, looking at his own neighbourhood and daily life. He’s addressing issues of ego, saying ‘I don’t think artists are more special than anyone else’ and trying to produce something more automatic, and thus democratic. I think he clearly understands that this banality, this horizontality is an essential aspect of photography.

Extract from Diane Smyth. “Behind the scenes of Moriyama’s London takeover,” on the British Journal of Photography website 17 October 2023 [Online] Cited 19/12/2023

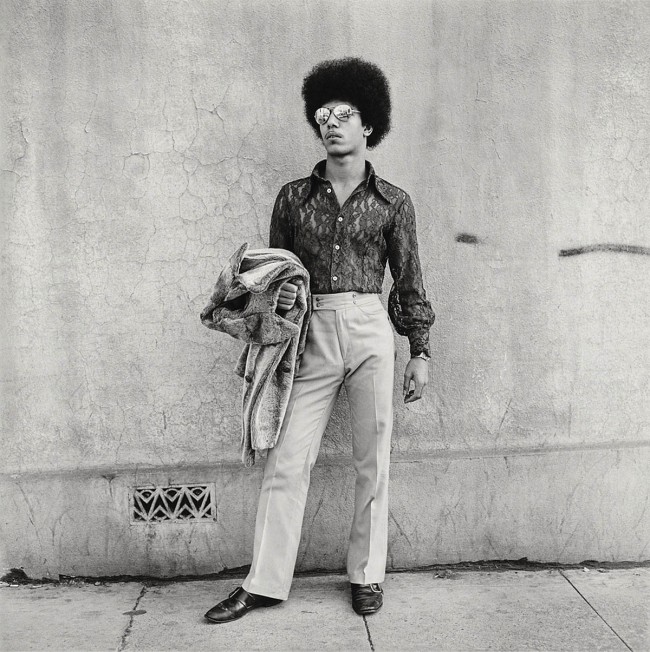

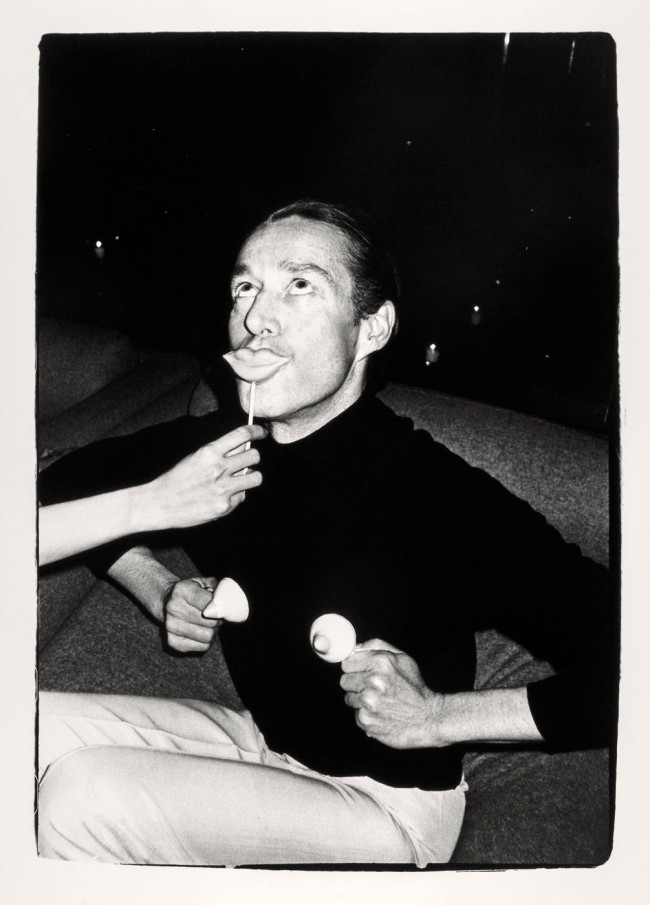

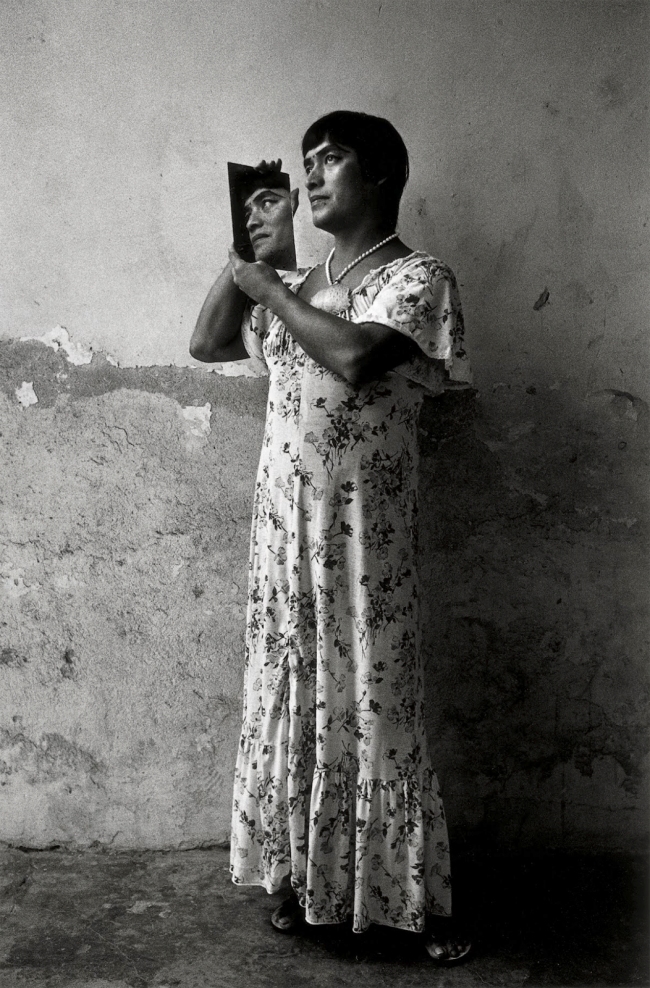

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Male actor playing a woman

Tokyo 1966

From Japan, a Photo Theater

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

His first monograph, Japan: A Photo Theatre (1968) is an edgy trip through a fast-evolving Tokyo

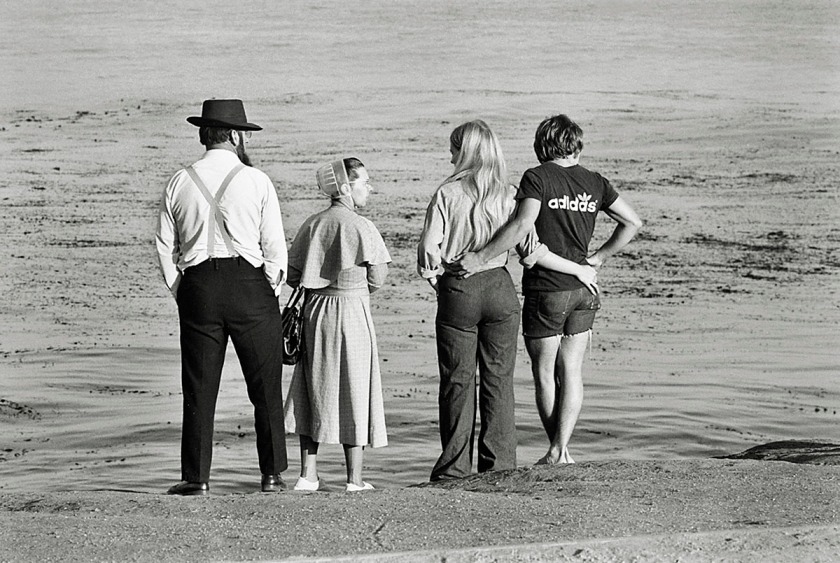

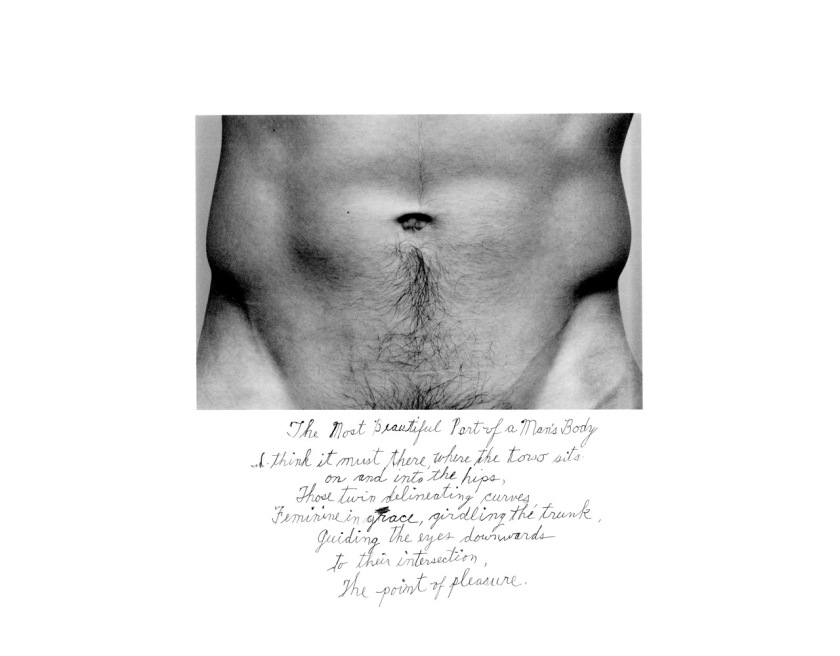

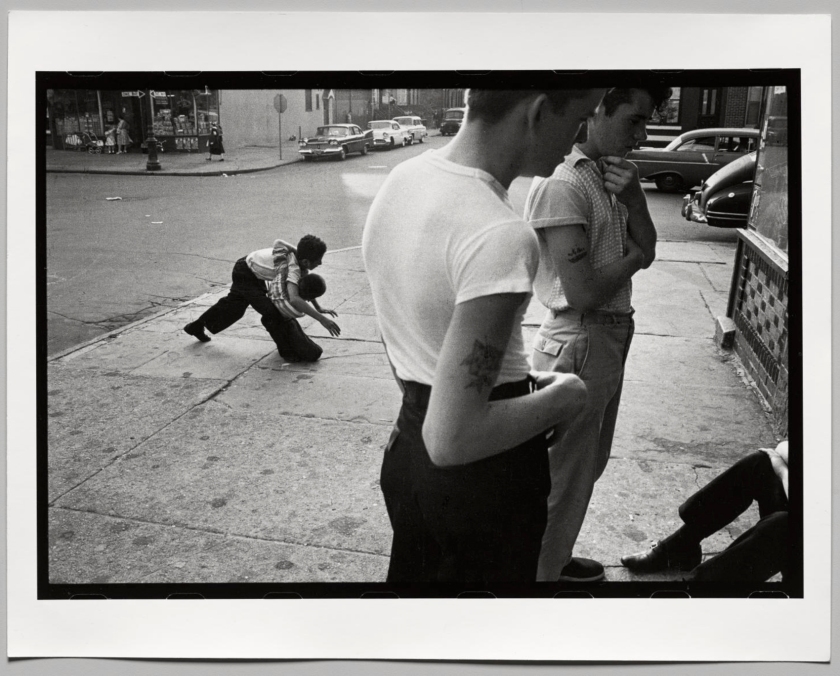

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Tokyo

1967

Asahi Graph, Apr 1967

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

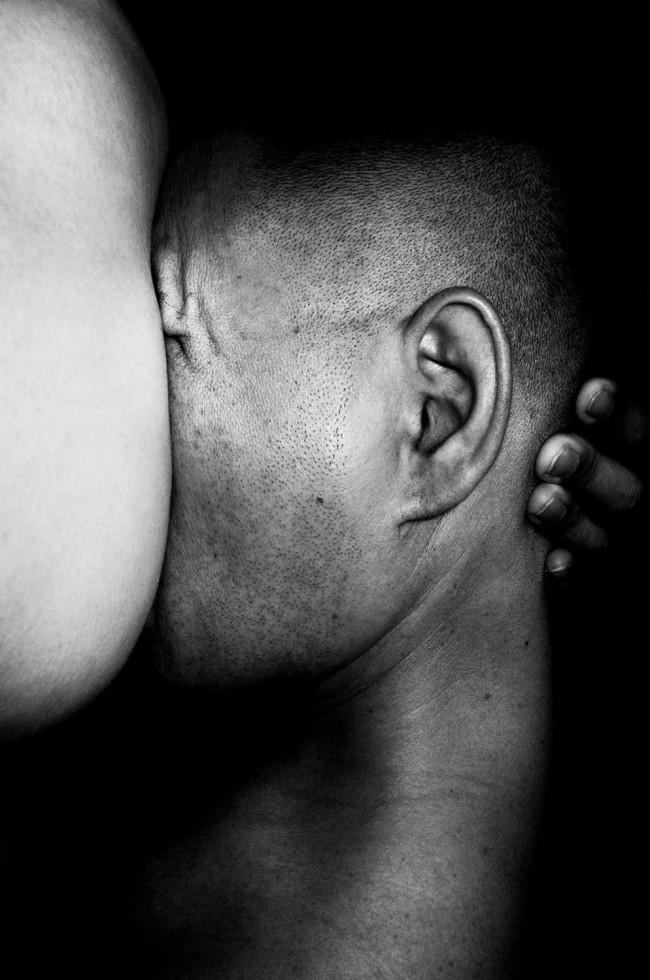

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

For Provoke #2

Tokyo, 1969

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Tokyo

1969

From Accident, Premeditated or not

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

In 1969 he started a one-year series Accident, published in the magazine Asahi Camera, in which he photographed existing images in the media.

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Tokyo

1969

From Accident, Premeditated or not

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

The Photographers’ Gallery presents the first UK retrospective of work by the acclaimed Japanese photographer, Daido Moriyama (b. 1938).

Featuring over 200 works, spanning from 1964 until the present day, Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective traverses different moments of Moriyama’s vast and productive career.

Taking over the whole Gallery, this exhibition celebrates one of the most innovative and influential artists and street photographers of our day. Championing photography as a democratic language, Moriyama inserted himself up close with Japanese society, capturing the clash of Japanese tradition with an accelerated Westernisation in post-war Japan. With his non-conformist approach and desire to challenge the medium, his work is tirelessly unpretentious, raw, blurred, radical and grainy and has defined the style of an entire generation.

Moriyama has spent his sixty-year career asking a fundamental question: what is photography? He rejected the dogmatism of art and the veneration of vintage prints, making the accessible and reproducible aspects of photography its most radical asset. Over and over, he reused his photographs in different contexts, experimenting with enlargements, crops and printing. Most of his work was made for printed pages rather than gallery walls. Fittingly, Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is the first UK exhibition to showcase many of his rare photobooks and magazines.

These publications, dating from early rare editions and out-of-print Japanese magazines to more recent titles, are on show alongside large-scale works and installations. The magazines and photobooks will give visitors unrivalled access to abundant archival and visual material to view, read and discover.

Presented in two phases of Moriyama’s work, Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective starts with Moriyama’s early work for Japanese magazines, his challenging of photojournalism, his experiments in Provoke magazine and the conceptual radicalisation of his photobook Farewell Photography (1972). During this period, he established his unique aesthetic, famously known as, buke, boke (meaning ‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’).

The second part of the exhibition starts in the 1980s, when Moriyama overcame a creative and personal crisis. In the following decades, he explored the essence of photography and of his own self, developing a visual lyricism with which he reflected on reality, memory and history.

Moriyama renewed street photography inside and outside Japan. His wanderings led him to cover miles in Tokyo, Osaka and Hokkaido, but also New York, Paris, São Paulo and Cologne. His work and travels are showcased in Record magazine, which the photographer continues to publish today.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is the product of a three-year research period, and is one of the most comprehensive exhibitions ever mounted of this artist’s work. It is organised by Instituto Moreira Salles in cooperation with the Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation.

The accompanying catalogue Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is published by Prestel, £45.

Press release from The Photographers’ Gallery

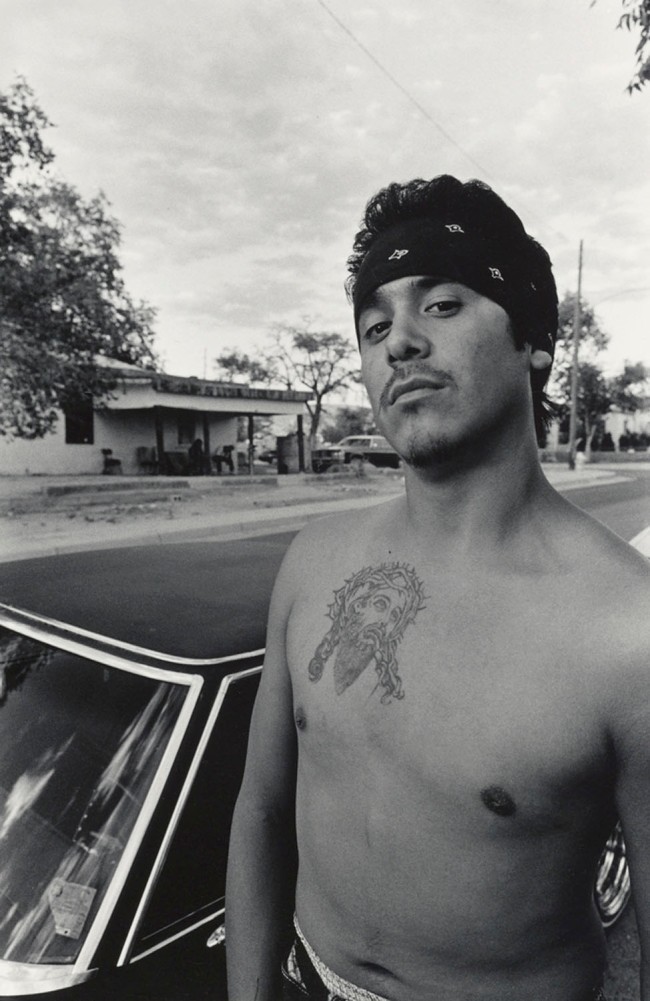

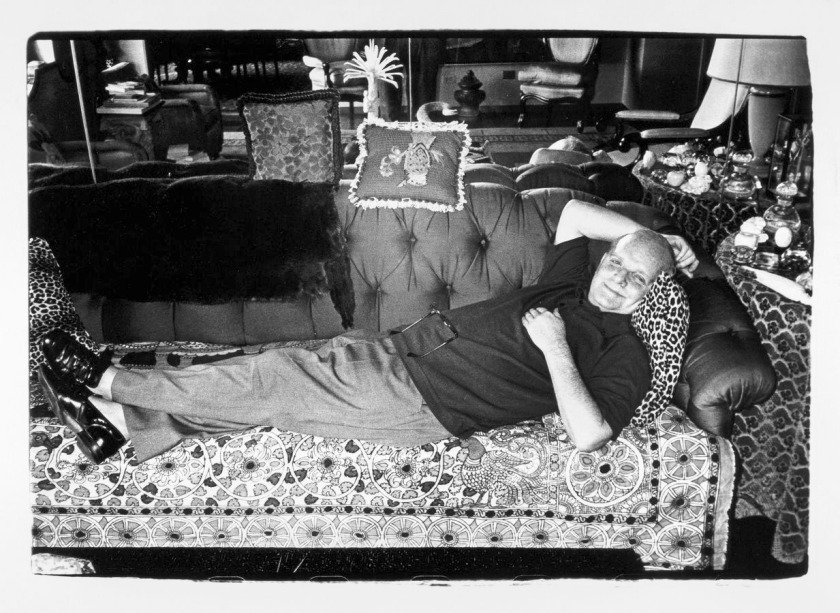

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Kanagawa

1967

From A Hunter

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Stray Dog, Misawa

1971

From A Hunter

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

7 things to know about Daido Moriyama

Learn more about Moriyama, a name synonymous with avant-garde photography, in this quick guide

Born in 1938 in Osaka, Japan, Moriyama’s photographic journey has been one of constant reinvention, testament to his unrelenting pursuit of the unexpected, chaotic, and the intensely personal.

Here we delve into seven things to know about Moriyama, the subject of the first retrospective of his work in the UK, now on at The Photographers’ Gallery:

1. A lens on post-war Japan

Born in post-war Japan, Daido Moriyama embraced photography as a democratic language, promoted by the mass media industry. His work encapsulates the clash between Japanese tradition and Westernisation, following the US military occupation of Japan after the end of World War II. He saw his camera as a tool for capturing not just images but also the essence of an evolving society, making his photographs a mirror to an era of rapid transformation.

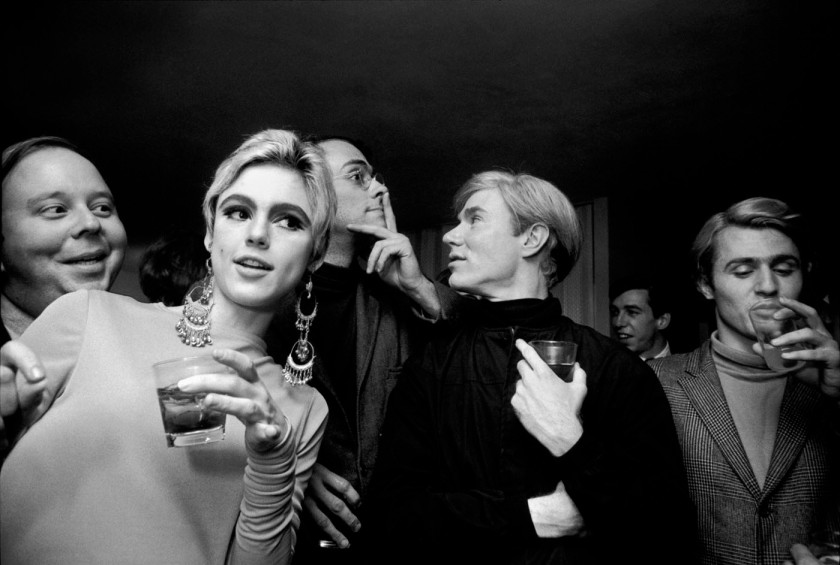

2. Influence of American artists

Moriyama was profoundly influenced by American artists like Andy Warhol and William Klein, as well as novelist and poet Jack Kerouac. Their bold and unconventional styles left a mark on his work. This influence can be seen in his daring approach to photography.

3. Provoke era

Provoke was a Japanese magazine which rejected the glossy commercial imagery and the style of documentary photography. Provoke was part of the photographic movement that arose out of the late 1960s and was motivated by the opposition artists had felt towards the traditional powers of Japan.

Moriyama played a pivotal role in the Provoke era, which saw a radical departure from conventional photography. He, along with other like-minded artists, aimed to free photography from its traditional confines. They believed in creating images that didn’t rely on words for interpretation.

4. Unique aesthetic

Moriyama’s work is known for its distinct style characterised in Japanese by ‘are, bure, boke,’ which translates as ‘grainy, blurry, out of focus’. This unique style challenges the conventional notion of photography and invites us to experience images in a new way.

5. Raw, radical, real approach to photography

Moriyama is a trailblazer in the world of photography, effectively reinventing street photography. He challenged the status quo by rejecting traditional norms and embracing the accessible and reproducible nature of photography as its most radical asset – something he continues to do to this day.

6. Farewell Photography and Record

Photobooks play a critical role in Moriyama’s work – one of his most radical works is Farewell Photography (Shashin yo Sayonara) – a book that pushes the boundaries of photographic reality. Moriyama collected rejected images, discarded photos, and even odd negatives to create a chaotic yet thought-provoking sequence of grainy, cropped, solarised, and scratched images. This work is a rebellion against conventional photography.

Magazines were also Moriyama’s fertile ground for photographic production and debates. His journey through photography can be seen in his ongoing publication, Record magazine. It’s a diary of his life in cities, a place where he explores his obsessions, insecurities, and memories. Flip through its pages, and you’ll experience an intimate glimpse into Moriyama’s life.

7. What is Photography?

Moriyama has spent his career asking a fundamental question: “What is photography?”

He rejected the dogmatism of art and the fetishisation of vintage prints, instead embracing the accessible and reproducible aspects of photography as its most radical asset.

Text from The Photographers’ Gallery website

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Harumi, Chūō

Tokyo, 1970

Weekly Playboy, Oct 1970

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Yokosuka

1970

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Setagaya-ku, Tokyo, Midnight

1986

From Letter to St-Loup 1990

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Labyrinth

2012

© Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Cover of Record No. 8

Published 2007

Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa Publishing

“It was 34 years ago, back in 1972, that I came out with the self-published photo journal ‘Kiroku.’ At the time, I was busy with all sorts of work for magazines. Partly because of a daily feeling inside that I shouldn’t let myself get carried away by it all, I came up with the idea of a small, self-published personal photo journal. Without any ties to work or any fixed topic, I just wanted to continue publishing a 16-page booklet with an arbitrary selection of favourite photos among the pictures I snapped from day to day. By nature, it was directed first and foremost to myself rather than other people. I wanted a simple, basic title, so I called it ‘Kiroku’ (record). However, the publication of ‘Kiroku’ sadly ended with issue number five. Now, thanks to the willpower and efforts of Akio Nagasawa, ‘Kiroku’ the magazine has resumed publication. Or rather, we should call it a fresh publication. With the hope that it will continue this time, I am selfishly thinking of asking Mr. Nagasawa to publish ‘Kiroku’ at a pace of four issues per year. I happily accept his proposal and look forward now to embarking on a new ‘voyage of recording.'”

~ Daido Moriyama

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Cover of Record No. 48

Published September, 2021

Tokyo: Akio Nagasawa Publishing

A few days ago in the evening, I suddenly felt the urge to take a train to Yokosuka. It was already after 8 PM when I arrived in the “Wakamatsu Market” entertainment district behind Yokosuka Chuo Station on the Keihin Line, but due to the ongoing pandemic, the lights of the normally crowded shops were all switched off. The streets at night had turned into a bleak, dimly lit place, with the usual drunken crowd nowhere in sight. I eventually held my camera into the darkness and shot a dozen or so pictures, while walking quite naturally down the main street toward the “Dobuita-dori” district. However, most of the shops here were closed as well, and only a few people passed by. It was a truly sad and lonely sight.

“Little wonder,” I muttered to myself, considering that more than half a century had passed since the time I wandered with the camera in my hand around Yokosuka, right in the middle of the Vietnam War.

It was here in Yokosuka that I decided to devote myself to the street snap style, so the way I captured the Yokosuka cityscape defined the future direction of my photographic work altogether. I was 25 at the time, and was still in my first year as an independent photographer. I remember how determined and ambitious I was when I started shooting, eager to carry my pictures into the Camera Mainichi office and get them published in the magazine. It was a time when I spent my days just clicking away while walking around with the camera in my hand, from Yokosuka out into the suburbs, from the main streets into the back alleys.

I had been familiar with the fact that Yokosuka was a US military base since I was a kid, and it also somehow seemed to suit my own constitution, so I think my dedication helped me overcome the fearfulness that came on the flip side of the fun that was taking photos in Yokosuka.

These are the results of a mere two days of shooting, but somewhere between the changing faces of Yokosuka, and my own response from the position of a somewhat cold and distant observer in the present, I think they are reflecting the passage of time, and the transformations of the times.

~ Afterword by Daido Moriyama

The Photographers’ Gallery

16-18 Ramillies Street

London

W1F 7LW

Opening hours:

Mon – Wed: 10.00 – 18.00

Thursday – Friday: 10.00 – 20.00

Saturday: 10.00 – 18.00

Sunday: 11.00 – 18.00

![Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984) 'Untitled [Liberace with his mother]' New York, 1954 Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984) 'Untitled [Liberace with his mother]' New York, 1954](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2023/09/83204a.jpg?w=840)

![Max Yavno (American, 1911-1985) 'Untitled [Opening Night at the San Francisco Opera]' 1947 Max Yavno (American, 1911-1985) 'Untitled [Opening Night at the San Francisco Opera]' 1947](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2023/09/92143117.jpg?w=650&h=547)

You must be logged in to post a comment.