November 2022

Warning: this text contains images of male nudity

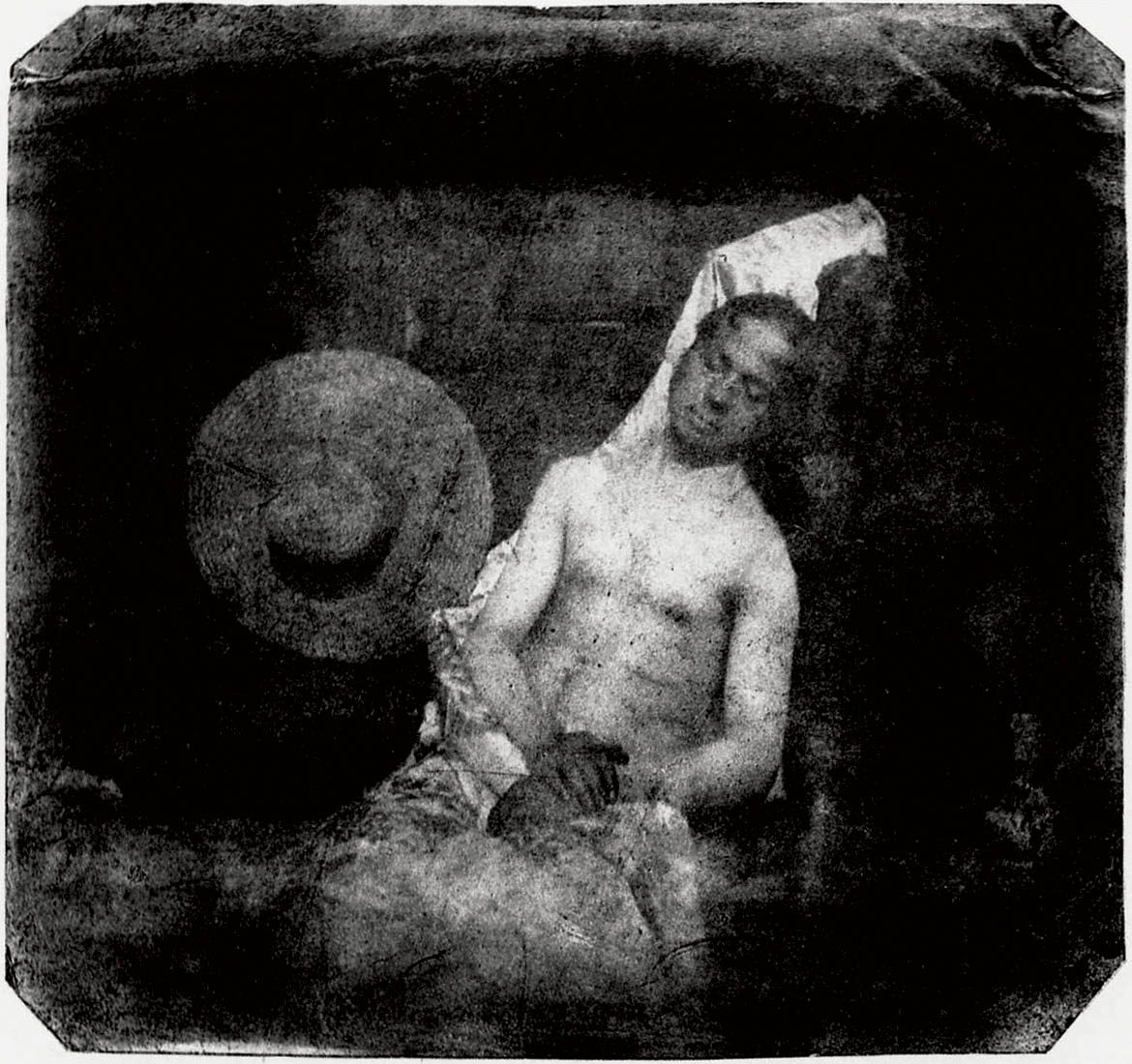

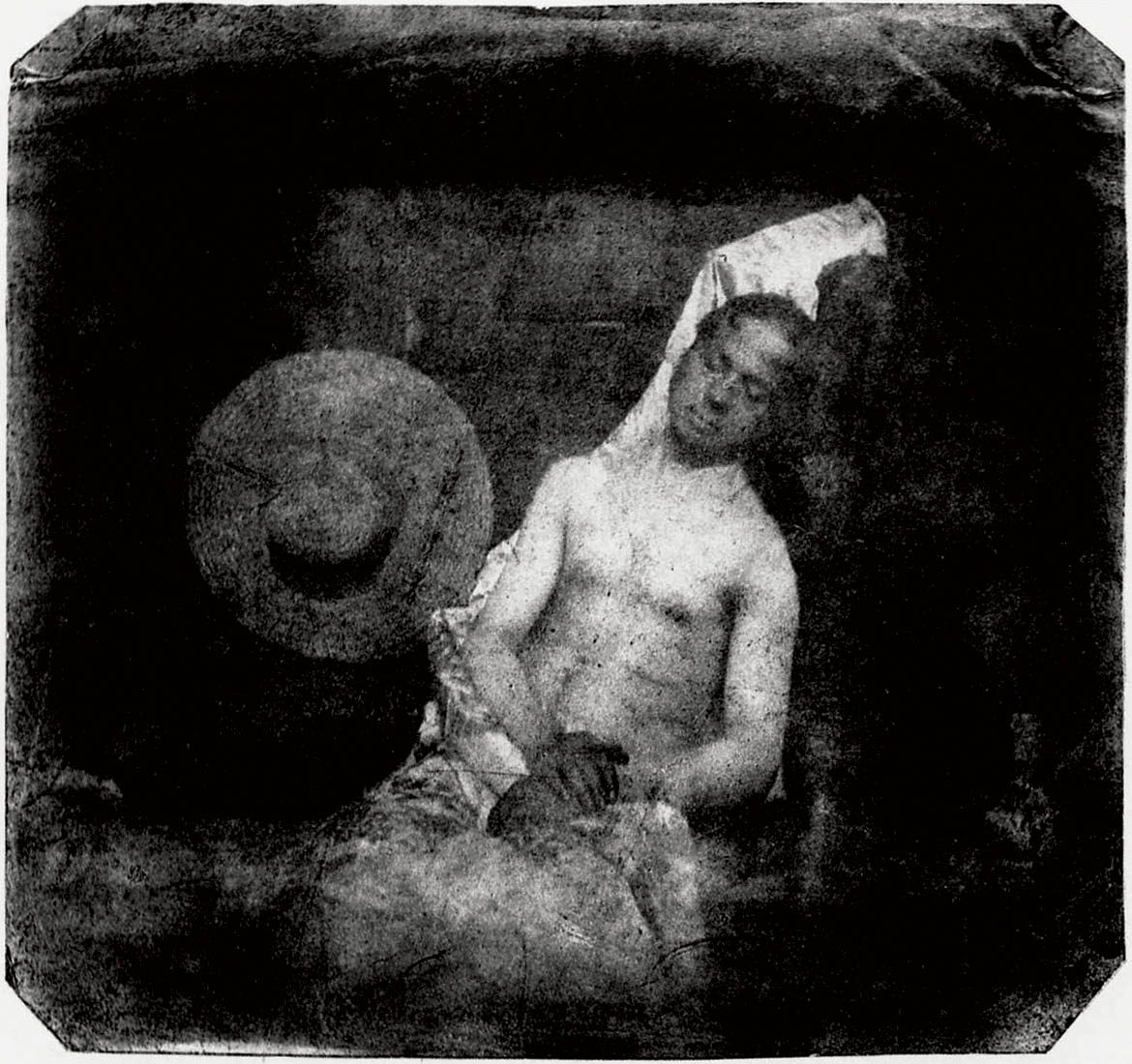

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

Self portrait as a drowned man

18 October 1840

Direct positive print

Public domain

Since the demise of my old website, my PhD research Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male (RMIT University, Melbourne, 2001) has no longer been available online.

I have now republished the first of twelve chapters, “Historical Pressings”, so that it is available to read. The chapter examines the history of photographic images of the muscular male body from the Victorian to contemporary era, as well as focusing on photographs of the gay male body and photographs of the male body that appealed to gay men. The pages are not a fully comprehensive guide to the history and context of this complex field, but may offer some insight into its development.

More chapters will be added as I get time. I hope the text is of some interest.

Other chapters of my Phd that have been published include In Press which investigates the photographic representation of the muscular male body in the (sometimes gay) media and gay male pornography; Re-pressentation which alternative investigates ways of imag(in)ing the male body and the issues surrounding the re-pressentation of different body images for gay men; and Bench Press which investigates the development of gym culture, its ‘masculinity’, ‘lifestyle’, and the images used to represent it.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

November 2022

Through plain language English (not academic speak) the text of this chapter examines the history of photographic images of the male body, including the male body as desired by gay men, and the portrayal in photography of the gay male body.

NB. This chapter should be read in conjunction with the Bench Press and Re-Pressentation chapters for a fuller overview of the development of the muscular male body. This chapter also contains descriptions of sexual activity.

Keywords

male body image, gay beauty myth, history of photographs of the male body, development of bodybuilding, queer body, gay male body, gay male body and HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS, photographic images of the male body, male2male sex, ephebe, muscular mesomorph, muscular male body, photography, art, erotic art, physique photography, Kinsey Institute, One Institute, gay pornography magazines, Physique Pictorial, Tom of Finland.

Sections

1/Beginnings

2/ Frederick Holland Day and Baron von Gloeden

3/ The Development of Bodybuilding

4/ WWI, Nature Worship, The Body and Propaganda

5/ Surrealism and the Body: George Platt Lynes

6/ 1930s Australian Body Architecture

7/ Minor White

8/ Physique Culture after WW2

9/ Tom of Finland

10/ 1950s Australia

11/ Later Physique Culture and gay pornography photographs

12/ Diane Arbus

13/ Robert Mapplethorpe

14/ Arthur Tress, Bill Henson and Bruce Weber

15/ Herb Ritts, Queer Press, Queer body

16/ And so it goes…

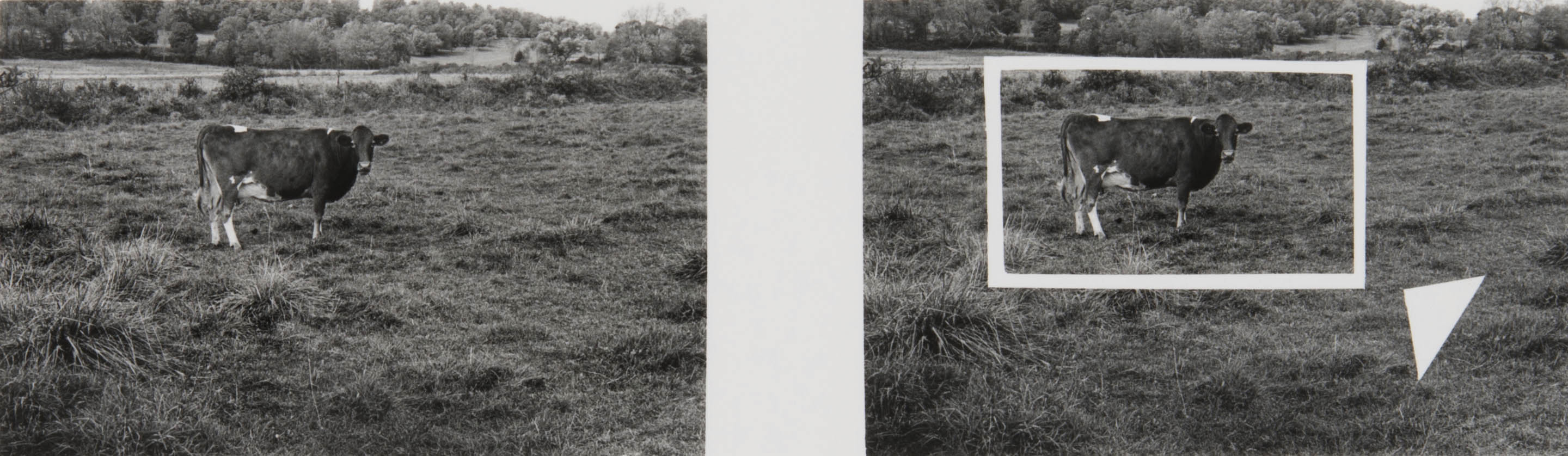

Beginnings

Since the invention of the camera people have taken photographs of the male body. The 1840 image by Hippolyte Bayard, “Self-portrait as a drowned man” is a self-portrait by the photographer depicting his fake suicide, taken in protest at being ignored as one of the inventors of photography. It is interesting because it is one of the earliest known photographic images of the unclothed male body and also a reflection of his self, an act of self-reflexivity. It is not his actual body but a reflection on how he would like to be seen by himself and others. This undercurrent of being seen, of projecting an image of the male body, has gradually been sexualised over the history of photography. The body in a photograph has become a canvas, able to mask or reveal the sexuality, identity and desires of the body and its owner. The male body in photography has become an object of desire for both the male and female viewer. The body is on display, open to the viewers gaze, possibly a desiring gaze. In the latter half of the twentieth century it is the muscular male body in particular that has become eroticised as an object of a desiring male2male gaze. In consumer society the muscular male body now acts as a sexualised marketable asset, used by ourselves and others, by the media and by companies to sell product. How has this sexual image of the muscular male body developed?

Within the history of art there is a profundity of depictions of the nude female form upon which the desiring gaze of the male could linger. With the advent of photography images of the nude male body became an accessible space for men desiring to look upon the bodies of other men. The nude male images featured in the early history of photography are endearing in their supposed lack of artifice. The bodies are of a natural type: everyday, normal run of the mill bodies reveal themselves directly to the camera as can be seen in the anonymous c. 1843 French daguerreotype, “Male Nude Study”.1 Although posed and required to hold the stance for a long period of time in order to expose the mercury plate, the model in this daguerreotype assumes a quiet confidence and comfort in his own body, staring directly at the camera whilst revealing his manhood for all to see. This period sees the first true revealing of the male body since the Renaissance, and the beginning of the eroticising of the male body as a visual ‘spectacle’ in the modern era.

Artists with an inclination towards the beauty of naked men were drawn towards the new medium. The photograph opened up the male body to the desiring gaze of the male viewer. The photograph reflected both reality and deception: the reality that these bodies existed in the flesh and the deception that they could be ‘had’, that the viewer could possess the body by looking, by eroticising, and through purchasing the photograph. Friendship between men was generally accepted up until the 18th century but in Victorian times homosexuality was named and classified as a sexual orientation in the early 1870’s. According to Michel Foucault2 this ‘friendship’ only became a problem with the rise of the powers of the police and the judiciary, who saw it as a deviant act; of course photography, as an instrument of ‘truth’, could prove the criminal activities of homosexuals and lead to their prosecution. When homosexual acts did come to the attention of the police and the medical profession it led to great scandals such as the trial and imprisonment of Oscar Wilde for sodomy.

Eadweard Muybridge (English, 1830-1904)

Nude men wrestling, lock (plate 345)

1884/1886

Public domain

Eadweard Muybridge. Animal locomotion: an electro-photographic investigation of consecutive phases of animal movements. 1872-1885 / published under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania. Plates. The plates printed by the Photo-Gravure Company. Philadelphia, 1887

On reflection there seems to have been an explosion of images around the late 1880’s to early 1890’s onwards of what we can now call homoerotic imagery; to contemporary eyes the 1887 photographs of nude wrestlers by Eadweard Muybridge have a distinct air of homo-eroticism about them. To keep such images above moral condemnation and within the bounds of propriety men where photographed in poses that were used for scientific studies (as in the case of the Muybridge photographs), as studies for other artists, or in religious poses. They appealed to the classical Greek ideal of masculinity and therefore avoided the sanctions of a society that was, on the surface, deeply conservative. For a brief moment imagine being a homosexual man in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, gazing for the first time at men in close physical proximity, touching each other in the nude, pressing each others flesh when such behaviour was thought of as subversive and illegal – what erotic desires photographs of the male body must have caused to those that appreciated such delicious pleasures, seeing them for the first time!

Frederick Holland Day and Baron von Gloeden

Two of the most famous photographers of the late Victorian and early Edwardian era who used the male body significantly in their work were Frederick Holland Day in America and Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden in Europe. Frederick Holland Day’s photographs of the male body concentrated on mythological and religious subject matter. In these photographs he tried to reveal a transcendence of spirit through an aesthetic vision of androgynous physical perfection. He revelled in the sensuous hedonistic beauty of what he saw as the perfection of the youthful male body. In the 1904 photograph “St. Sebastian,” (below) for example, the young male body is presented for our adoring gaze in the combined ecstasy and agony of suffering. In his mythological photographs Holland Day used the idealism of Ancient Greece as the basis for his directed and staged images. These are not the bodies of muscular men but of youthful boys (ephebes) in their adolescence; they seem to have an ambiguous sexuality. The models genitalia are rarely shown and when they are, the penis is usually hidden in dark shadow, imbuing the photographs with a sexual mystery. The images are suffused with an erotic beauty of the male body never seen before, a photographic reflection of a seductive utopian beauty seen through the desiring eye of a homosexual photographer.

Frederick Holland Day (American, 1864-1933)

Saint Sebastian

c. 1906

Platinum print

See Frederick Holland Day. “Saint Sebastian.” Platinum print, c. 1906, in Woody, Jack and Crump, James. F. Holland Day: Suffering The Ideal. Santa Fe: Twin Palms Publishers, 1995, Plate 53. Courtesy: Library of Congress

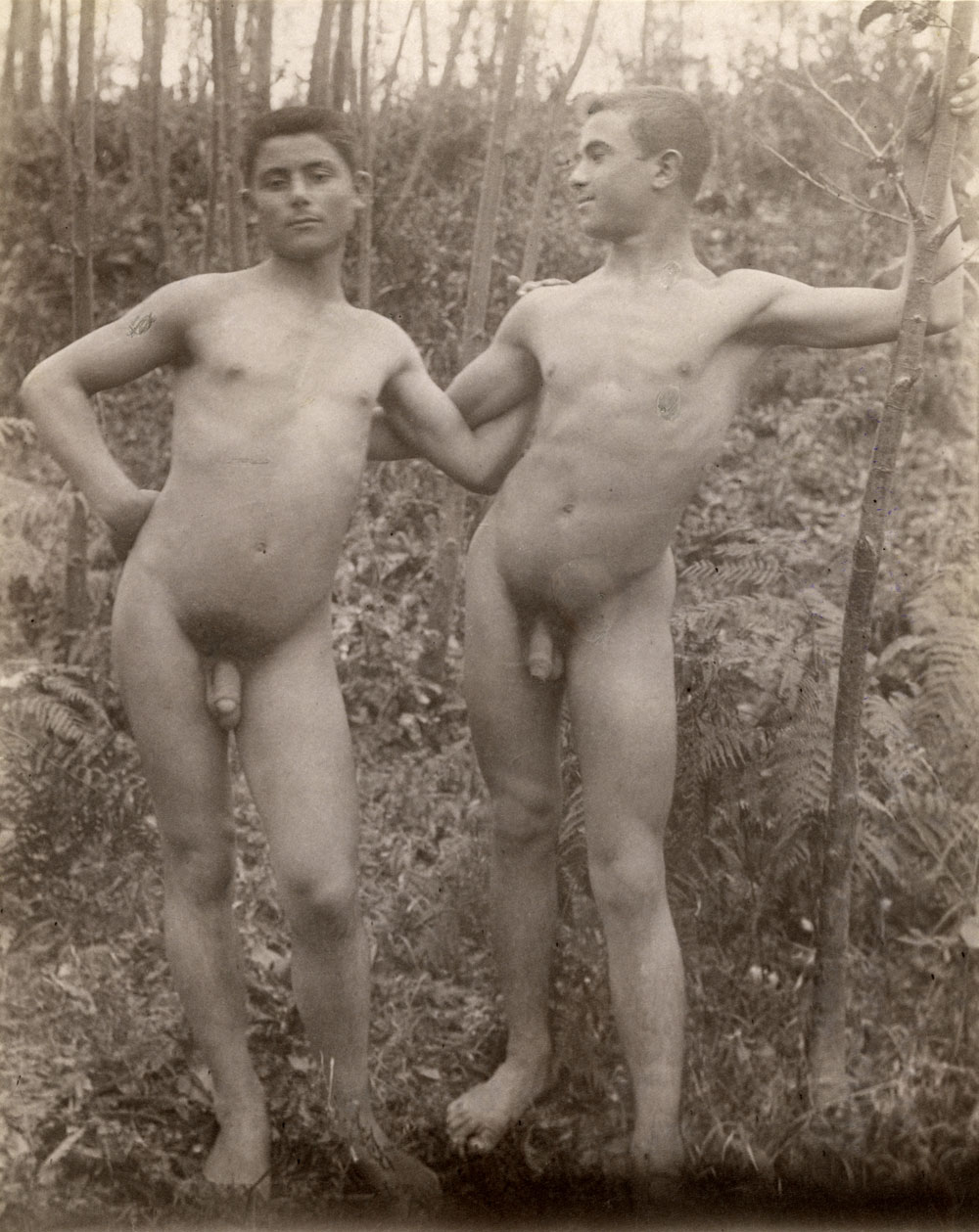

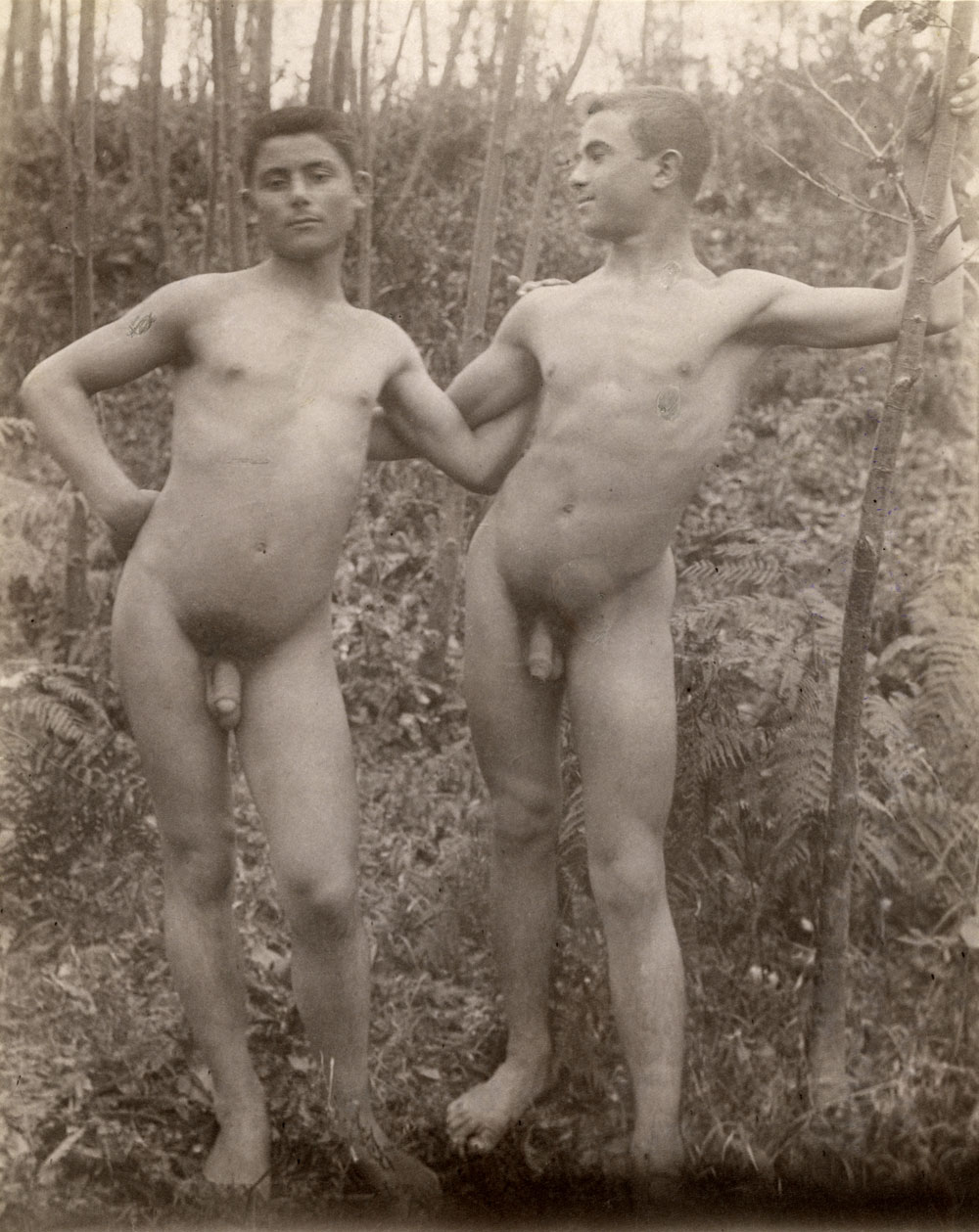

In Europe Wilhelm von Gloeden’s photographs of young ephebes (males between boy and man) have a much more open and confronting sexual presence. Using heavily set Sicilian peasant youths with rough hands and feet von Gloeden turned some of these bodies into heroic images of Grecian legend, usually photographing his nude figures in their entirety. In undertaking research into von Gloedens’ photographs at The Kinsey Institute, I was quite surprised at how little von Gloeden used classical props such as togas and vases in his photographs, relying instead on just the form of the body with perhaps a ribbon in the hair. His photographs depict the penis and the male rump quite openly and he hints at possible erotic sexual encounters between models through their intimate gaze and physical contact.

The photographs were collected by some people for their chaste and idyllic nature but for others, such as homosexual men, there is a subtext of latent homo-eroticism present in the positioning and presentation of the youthful male body. The imagery of the penis and the male rump can be seen as totally innocent, but to homosexual men desire can be aroused by the depiction of such erogenous zones within these photographs.

In both photographers work there is a reliance on the ‘natural’ body. In von Gloeden’s case it is the smooth peasant body with rough hands and feet; in Holland Day’s it is the smooth sinuous body of the adolescent. At the same time in both Europe and America, however, there began to emerge a new form for the body of a man, that of the muscular mesomorph, the V-shaped masculine ‘ideal’ expressed through the image of the bodybuilder, photographed in all his muscular splendour!

Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931)

Two nude men standing in a forest

Taormina, Sicily, 1899

Albumen print

The Development of Bodybuilding

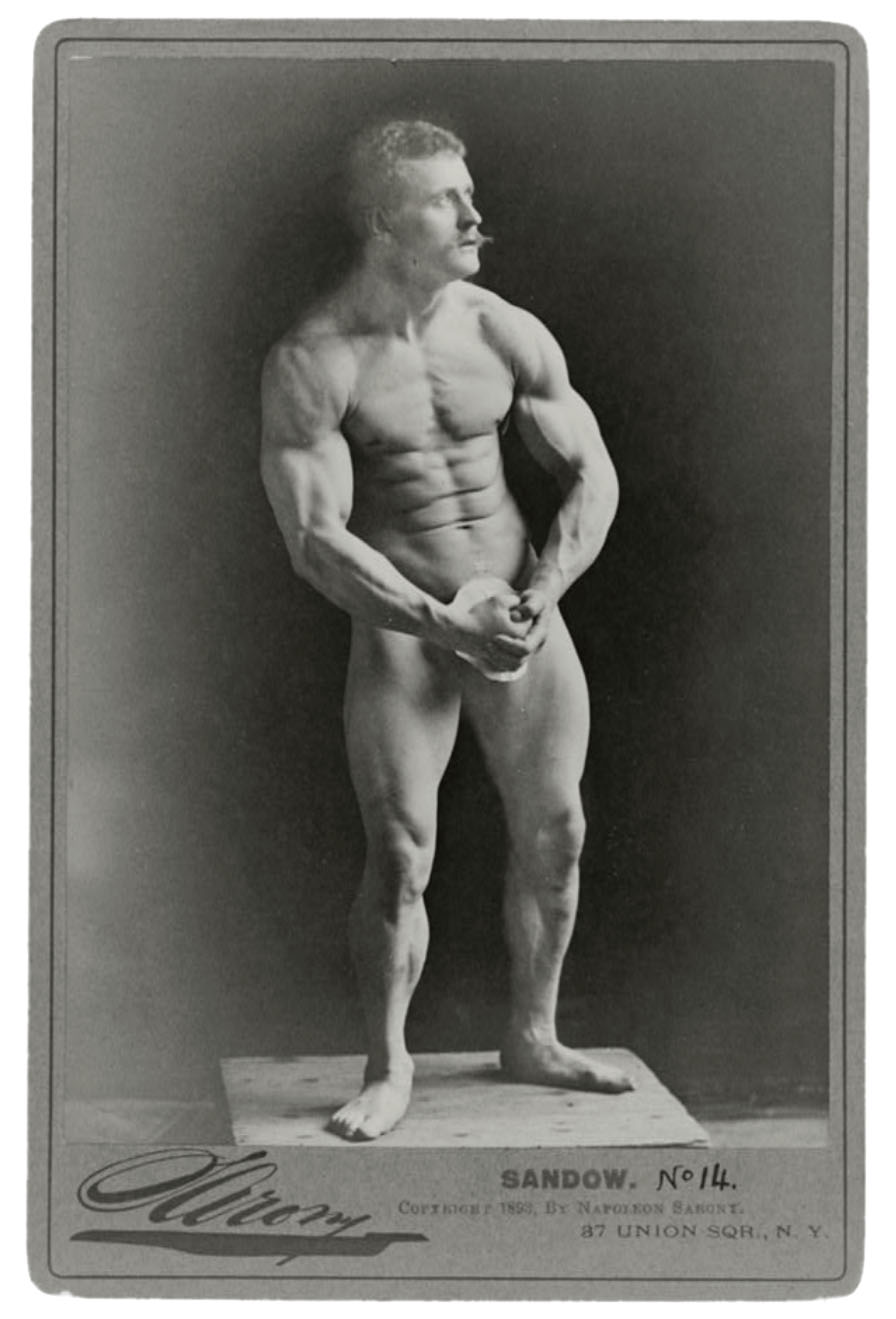

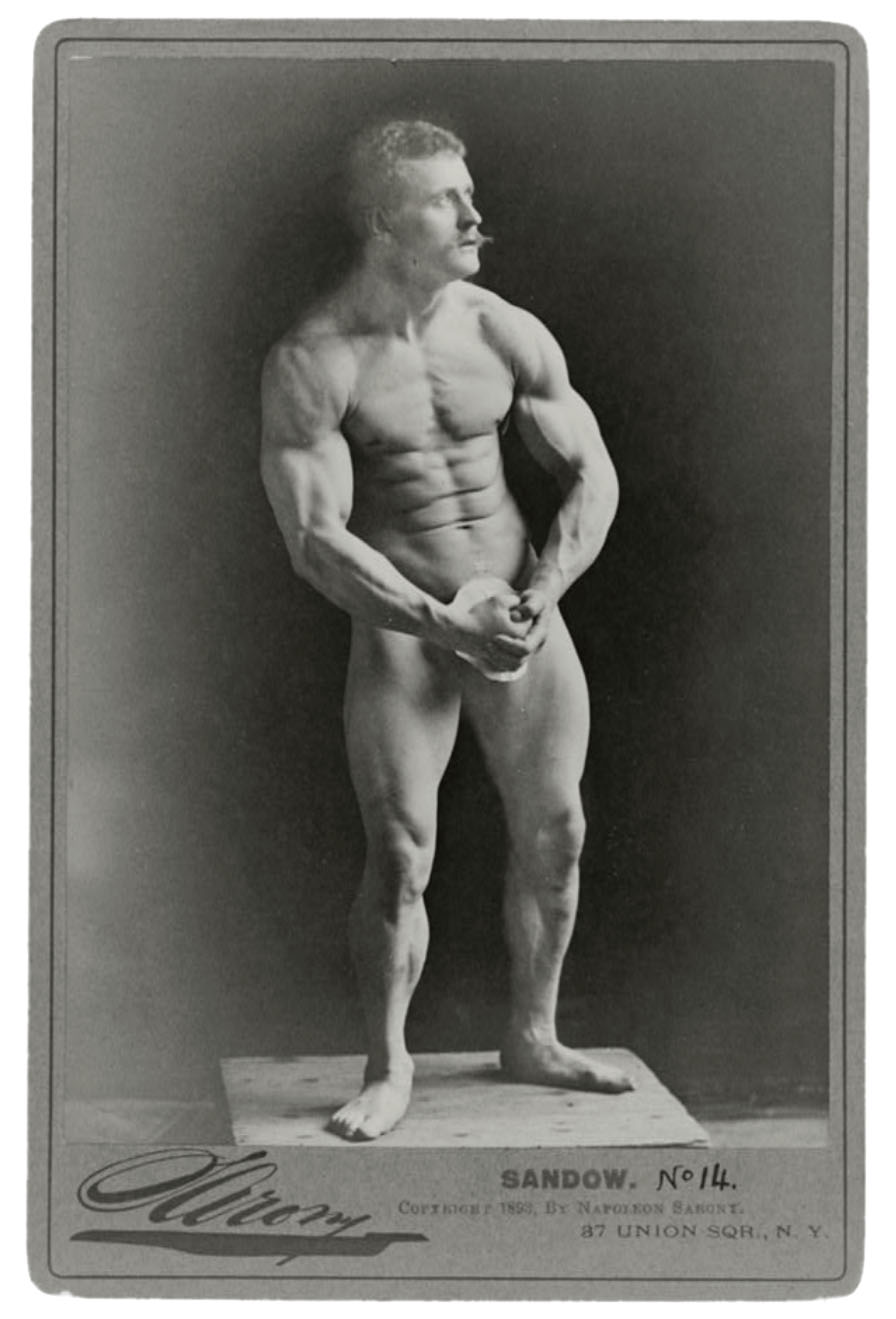

Frederick Mueller, better known to the world as the Prussian bodybuilder Eugen Sandow, was launched on the public at the World’s Colombian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. He was the world’s first true bodybuilder and he had a thick set muscular body with an outstanding back and abdominal muscles.

Bodybuilding came into existence as a result of the perceived effeminization of men brought on by the effects of the industrial revolution – boxing, gymnastics and weightlifting were undertaken to combat slothfulness, lack of exercise and unmanliness. This led to the formation of what Elliott Gorn in his book The Manly Art (Robson Books, 1986) has called ‘The Cult of Muscularity’,3 where the ‘ideal’ of the perfect masculine body can be linked to a concern for the position and power of men in an industrialised world. Sandow promoted himself not as the strongest man in the world but as the man with the most perfect physique, the first time this had ever happened in the history of the male body. He projected an ideal of physical perfection. He used photography of his muscular torso to promote himself and his products such as books, dumbbells and a brand of cocoa. He often performed and was photographed in the nude by leading photographers in Europe and America and was not at all bashful about exposing his naked body to the admiring gaze of both men and women.

His torso appeared on numerous cartes de visite, inspiring other young men to take up bodybuilding and gradually the muscular male body became an object of adulation for middle-class men and boys. The popularity of the image of his perfect body encouraged other men to purchase images of such muscular edifices and allowed them to desire to have a body like Sandow’s themselves. It also allowed homosexual men to eroticise the body of the male through their desiring gaze. But the ‘normal’ standards of heterosexual masculinity had to be defended. A desiring male gaze (men looking at the bodies of other men) could not be allowed to be homosexual; homosexuals were portrayed by the popular press and society as effete and feminine in order to deny the fact that a ‘real’ man could desire other men.4 (See the Femi-nancy Press chapter of the CD ROM for more details on how homosexuals were portrayed as feminine). A man had to be a ‘real’ man otherwise he could be queer, an arse bandit!

Napoleon Sarony (French, 1821-1896)

Eugen Sandow

1893

Photographic print on cabinet card

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Still, photographs of Greco-Roman wrestling continued to offer the opportunity for homosexual men to look upon the muscular bodies of other men in close physical proximity and intimacy. A classical wrestling style and classical props legitimised the subject matter. In static poses, which most photographs were at this time because of the length of the exposure, the genitalia were usually covered with a discreetly placed fig leaf or loin cloth, or the fig leaf / posing pouch were added later by retouching the photograph (as can be seen in the anonymous undated image of two wrestlers, “Otto Arco and Adrian Deraiz”).5 People such as Bernard MacFadden, publisher of Physical Culture, said these images were not at all erotic when viewed by other men. I think I would have found these images very horny (if a little illicit), if I had been a poof back in those days.

The physique of the muscular body had appeal across all class boundaries and bodybuilding was one of the first social activities that could be undertaken by any man no matter what his social position. Bodybuilding reinforced the power of traditional heterosexual behaviour – to be the breadwinner and provider for women, men had to see themselves as strong, tough and masculine. A fit, strong body is a productive body able to do more work through its shear physical bulk and endurance. Unlike the anonymous bodies in the photographs of Holland Day and von Gloeden here the bodies are named as individuals, men proud of their masculine bodies. It is the photographers that are anonymous, as though they are of little consequence in comparison to the flesh that is placed before their lenses.

I suggest that the impression the muscular body made on individual men was also linked to developments in other areas (art, construction and architecture for example), which were themselves influenced by industrialisation and its affect on social structure. In her book Space, Time and Perversion: Essays on the Politics of Bodies (Routledge, 1995), Elizabeth Grosz says that the city is an important element in the social production of sexually active bodies. As the cities became further industrialised and the population of cities increased in the Victorian era, space to build new buildings was at a premium. The 1890s saw the building of the first skyscrapers in America, impressive pieces of engineering that towered above the city skyline. Their object was to get more internal volume and external surface area into the same amount of space so that the building held more and was more visible to the human eye. I believe this construction has parallels in the similar development of the muscular male body, a facade with more surface area than other men’s bodies, which makes that man more visible, admired and (secretly) desired.

Further, in art the Futurists believed in the ultimate power of the machine and portrayed both the machine and the body in a blur of speed and motion. In the Age of the Machine the construction of the body became industrialised, the body becoming armoured against the outside world and the difficulty of living in it. The body became a machine, indestructible, superhuman. Within this demanding world men sought to confirm their dominance over women (especially after women achieved the ability to vote), and other men. Domination was affirmed partially through images of the muscular male (as can be seen in the image Charles Atlas and Tony Sansone in “The Slave” below), although viewed through contemporary eyes a definite homo-erotic element is also present.

Charles Atlas and Tony Sansone in “The Slave” also presents us with a man who challenged the fame of Eugen Sandow. His name was Tony Sansone and he emerged as the new hero of bodybuilding around the year 1925. Graced with a perfect physique for a taller man, Sansone was more lithe than the stocky, muscular Sandow and can be seen to represent a classical heroic Grecian body, perfect in it’s form. He had Valentino like features, perfect bone structure and was very photogenic, always a useful asset when selling a book of photographs of yourself.

Grace Salon of Art

Charles Atlas and Tony Sansone in “The Slave”

1930s

Edwin F. Townsend (American, 1877-1948)

Portrait of Tony Sansone

Nd (1930s)

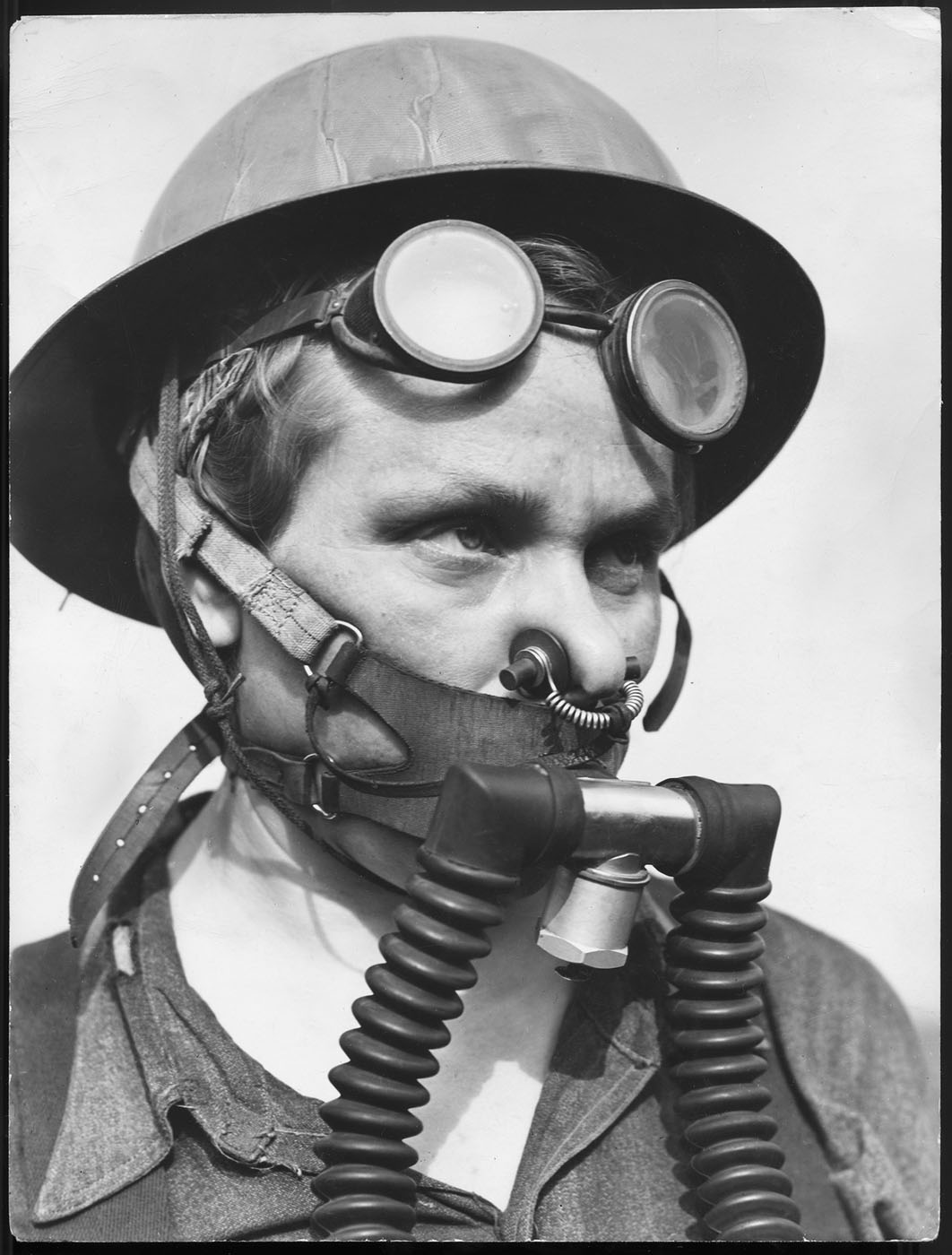

WWI, Nature Worship, The Body and Propaganda

The First World War caused a huge amount of devastation to the morale and confidence of the male population of Europe and America. Millions of young men were slaughtered on the killing fields of Flanders and Galipolli as the reality of trench warfare set in. Here it did not matter what kind of body a man had – every body was fodder for the machine guns that constantly ranged the lines of advancing men during an assault. A bullet or nerve gas kills a strong, muscular body just as well as a thin, natural body. The war created anxieties and conflicts in men and undermined their confidence and ability to cope in the world after peace came. During the war images of men were used to reinforce the patriotic message of fighting for your country. After the war the Surrealist and German Expressionist movements made use of photography of the body to depict the dreams, deprivations and abuse that men were suffering as a result of it. In opposition to this avant-garde art and to reinforce the message of the strong, omnipotent male – images of muscular bodies were again used to shore up traditional ‘masculine’ values. They were used to advertise sporting events such as boxing and wrestling matches and sporting heroes appeared on cigarette cards emphasising skills and achievements. These images and events ensured that masculinity was kept at the forefront of human endeavour and social cognisance.

After the devastation of The First World War, the 1920’s saw the development in Germany, America and England of the cult of ‘nature worship’ – a love of the outdoors, the sun and the naturalness of the body that would eventually lead to the formation of the nudist movement. This movement was exploited by governments and integrated into the training regimes of their armies in the search for a fitter more professional soldier. But the nudity aspect was frowned upon because of its homo-erotic overtones: Hitler banned all naturist clubs in Germany in 1933 and the obvious eroticism of training in the nude would not have been overlooked. Physical training had been introduced into the armies and navies of the Western world at the end of the 19th century and as the new century progressed physical fitness was seen as an integral part of the discipline and efficiency of such bodies. As fascist states started to emerge during the latter half of the 1920’s and the beginning of the 1930’s they started making use of the muscular male body as a symbol of physical perfection.

The idealised muscularity of the body was used by the state to encourage its aims. The use of classical images of muscular bodies reflected a nostalgia for the past and an appeal to nationalism. Heroic statues were recreated in stadiums in Italy and Germany, symbols that represented the power, strength and virility of the state and its leaders. In a totalitarian regime the body becomes the property of the state, and is used as a tool in collusion with the state’s moral and political agendas. Propaganda became a major tool of the state. During the decade leading up to the Second World War and during the war itself images of the body were used to help support the policies of the government, to encourage enlistment and bolster the morale of soldiers and public. Such images appealed to the patriotic nature of the population but could still include suspicions of homo-erotic activity, such as in the (probably Russian) poster from 1935 (below).

Anonymous photographer

The Ball Throwers

c. 1925

Army Training

Germany

“The training methods of Major Hans Suren, Chief of the German Army School of Physical Exercise in the 1920’s, involved training naked – pursuing ideals of physical perfection which were later promoted by Hitler as a sign of Aryan racial superiority.”

Anonymous photographer. “The Ball Throwers.” Army Training. Germany. c. 1925, in Dutton, Kenneth. The Perfectible Body. London: Cassell, 1995, p. 208

Unknown photographer

Josef Thorak “Comradeship”

1937

German Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Internationale

“Comradeship”, at the entrance to the German pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition 1937, by Josef Thorak, who was one of two “official sculptors” of the 3rd Reich. Nazi era statues were often strangely homoerotic.6

Here comradeship should not be confused with friendship which was discussed at the beginning of this chapter.

Anonymous artist

Propaganda poster

1935

Surrealism and the Body: George Platt Lynes

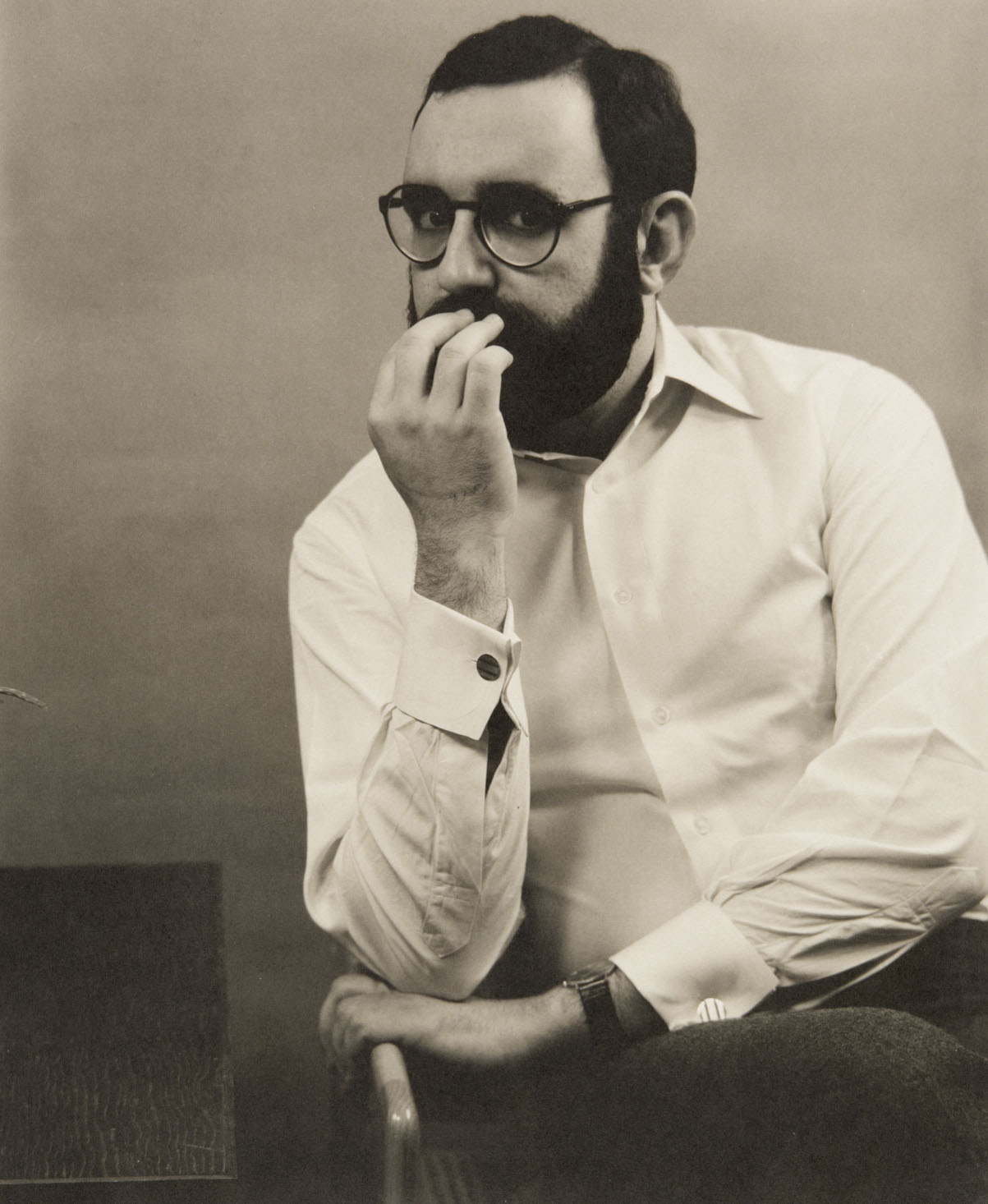

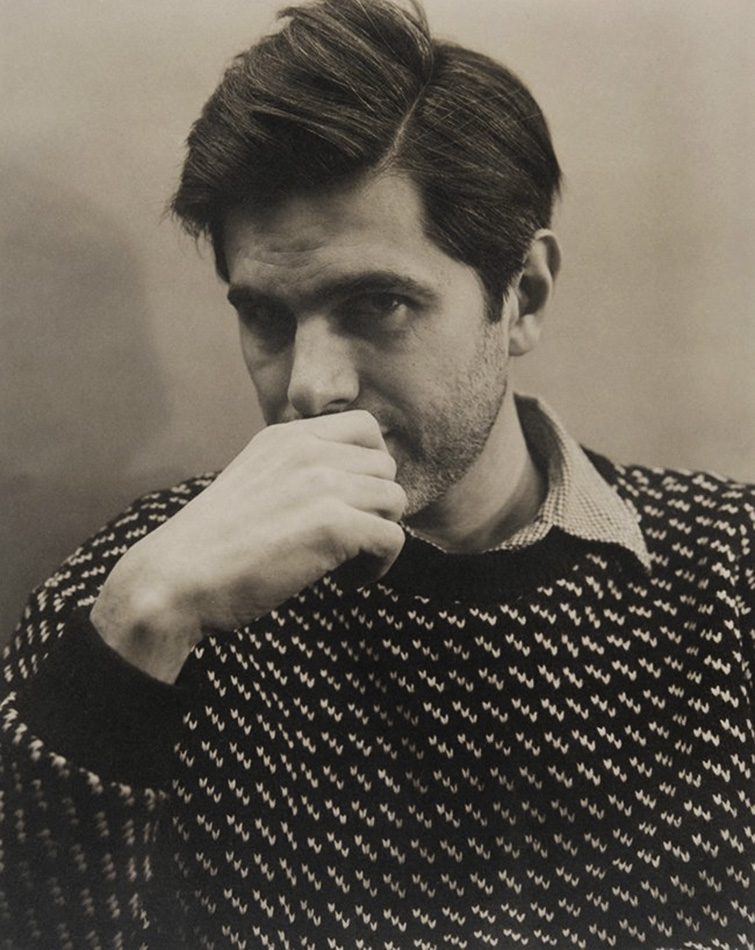

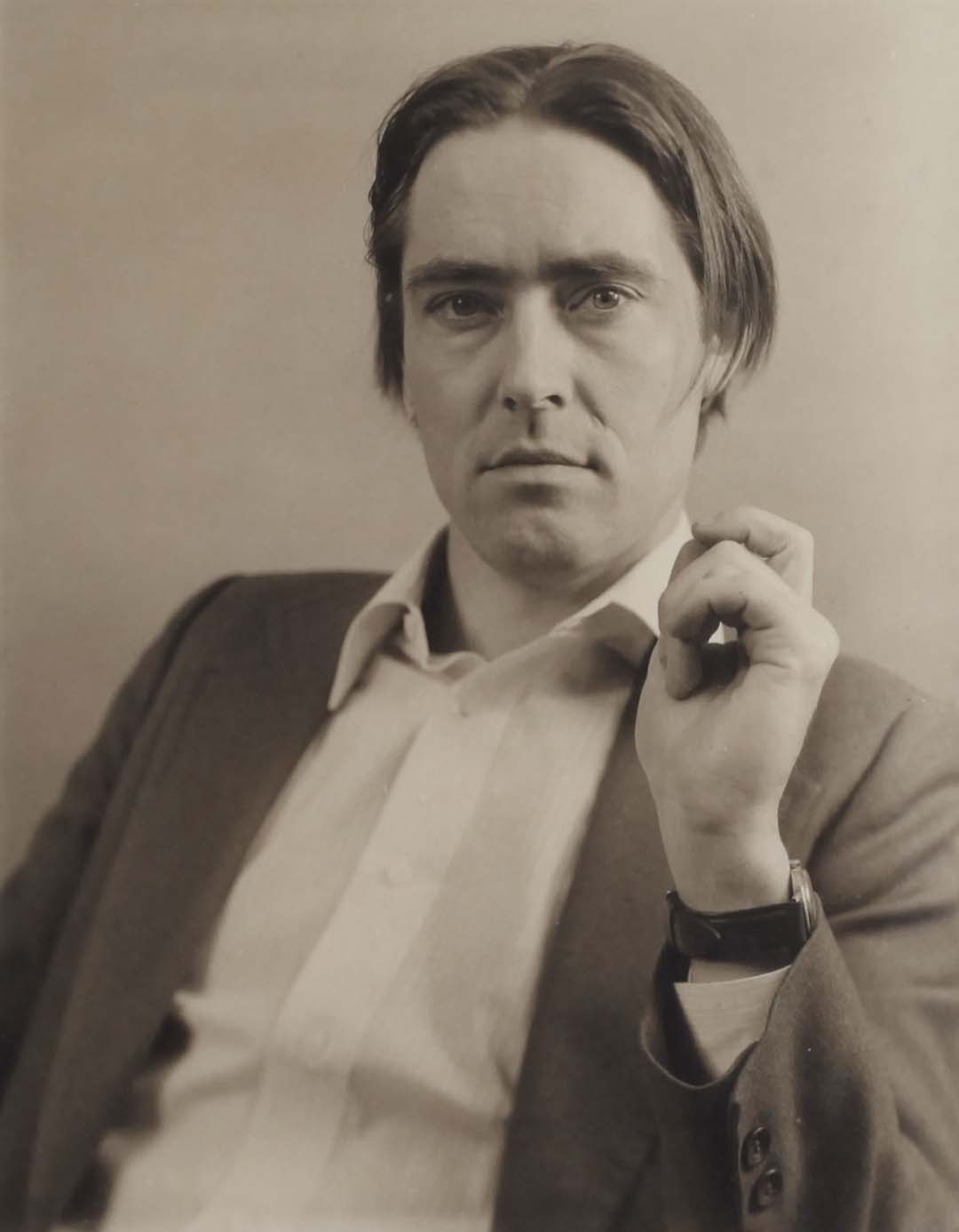

In contrast to the fascistic depictions of the male body used for propaganda, Surrealism (formed in the 1920s) was adapted by several influential gay photographers in the 1930s to express their own artistic interest in the male body. Although Surrealism was heavily anti-feminine and anti-homosexual, these gay male photographers, the Germans Herbert List, Horst P. Horst, and George Hoyningen-Huene and the American George Platt Lynes, made extensive use of the liberation of fantasies that Surrealism offered. Although the open depiction of homosexuality was still not possible in the 1930s there is an intuitive awareness on the part of the photographers and the viewer of the presence of sexual rituals and interactions. There is also the knowledge that there is a ready audience for these photographs, not only in the close circle of friends that surrounded the photographers, but also from gay men that instinctively recognise the homo-erotic quality of these images when shown them. The bodies in the images of the above photographers tend to be of two distinct types, the ephebe and the muscular mesomorphic body.

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

A Forgotten Model

c. 1937

Gelatin silver print

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

The Sleepwalker

1935

Gelatin silver print

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Names Withheld

1952

Gelatin silver print

Herbert List (German, 1903-1975)

Armor II

1934

Gelatin silver print

15 7/10 × 11 4/5 in (40 × 30cm)

Herbert List (German, 1903-1975)

Young men on Naxos

1937

Gelatin silver print

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled

1936

Gelatin silver print

In America George Platt Lynes was working as a fashion photographer. George Platt Lynes had his own studio in New York where he photographed dancers, artists and celebrities amongst others. He undertook a series of mythological photographs on classical themes (which are amazing for their composition which features Surrealist motifs). Privately he photographed male nudes but was reluctant to show them in public for fear of the harm that they could do to his reputation and business with the fashion magazines. Generally his earlier nude photographs concentrate on the idealised youthful body or ‘ephebe’. The 1936 photograph “Untitled” (above) is an exception. Here we gaze upon a smooth, defined muscular torso, the man (too old to be an ephebe) both in agony and ecstasy, his head thrown back, his eyes covered by one of his arms. Sightless he does not see the ‘other’ male hand that encloses his genitals, hiding them but also possibly about to molest them / release them at the same time. (NB. See my research notes on George Platt Lynes photographs in the Collection at the Kinsey Institute).

We can relate this photograph to Fred Holland Day’s photograph of “St. Sebastian” discussed earlier, this image stripped bare of most of the religious iconography of the previous image. The body is displayed for our adoration in all its muscularity, the lighting picking up the definition of diaphragm, ribs and chest, the hand hiding and perhaps, in the future, offering release to a suppressed sexuality. Here an-‘other’ hand is much closer to the origin of male2male sexual desire. Looking at this photograph you can visualise a sexual fantasy, so I imagine that it would have had the same effect on homosexual men when they looked at it in the 1930s.

In the slightly later nude photographs by George Platt Lynes the latent homo-eroticism evident in his earlier work becomes even more apparent.

In his image from 1942 “Untitled” we observe three young men in bare surroundings, likely to be Platt Lynes studio. The faces of the three men are not visible at all, evoking a sexual anonymity (According to David Leddick the models are Charles ‘Tex’ Smutney, Charles ‘Buddy’ Stanley, and Bradbury Ball.7 The image comes from a series of 30 photographs of these three boys undressing and lying on a bed together; please see my notes on Image 483 and others from this series in the Collection at The Kinsey Institute).

![George Platt Lynes. 'Untitled [Charles 'Tex' Smutney, Charles 'Buddy' Stanley, and Bradbury Ball]' c. 1942 George Platt Lynes. 'Untitled [Charles 'Tex' Smutney, Charles 'Buddy' Stanley, and Bradbury Ball]' c. 1942](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/lynes-c-1942.jpg)

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled [Charles ‘Tex’ Smutney, Charles ‘Buddy’ Stanley, and Bradbury Ball]

c. 1942

Gelatin silver print

On a chair sits a pile of discarded clothes and in the background a man is removing the clothing of another man. The bulge of the man’s penis is quite visible through the material of the underpants. On the bed lies another man, face down, passive, unresisting, head turned away from us, the curve of his arse signalling a site of erotic activity for a gay man. Our gaze is directed to the arse of the man lying on the bed as a site of sexual desire and although nothing is actually happening in the photograph, there is a sexual ‘frisson’ in its composition.

As Lynes became more despondent with his career as a fashion photographer his private photographs of male nudes tended to take on a darker and sharper edge. After a period of residence in Hollywood he returned to New York nearly penniless. His style of photographing the male nude underwent a revision. While the photographs of his European colleagues still relied on the sun drenched bodies of young adolescent males evoking memories of classical beauty and the mythology of Ancient Greece the later nudes of Platt Lynes feature a mixture of youthful ephebes and heavier set bodies which appear to be more sexually knowing. The compositional style of dramatically lit photographs of muscular torsos of older men shot in close up (see the undated image “Untitled,” Frontal Male Nude, for example; see also my notes on this image, Image 144, in the Collection at The Kinsey Institute), were possibly influenced by a number of things – his time in Hollywood with its images of handsome, swash-buckling movie stars with broad chests and magnificent physiques; the images of bodybuilders by physique photographers that George Platt Lynes visited; the fact that his lover George Tichenor had been killed during WWII; and the knowledge that he was penniless and had cancer. There is, I think, a certain perhaps not desperation but sadness and strength in much of his later photographs of the male nude that harnesses the inherent sexual power embedded within their subject matter.

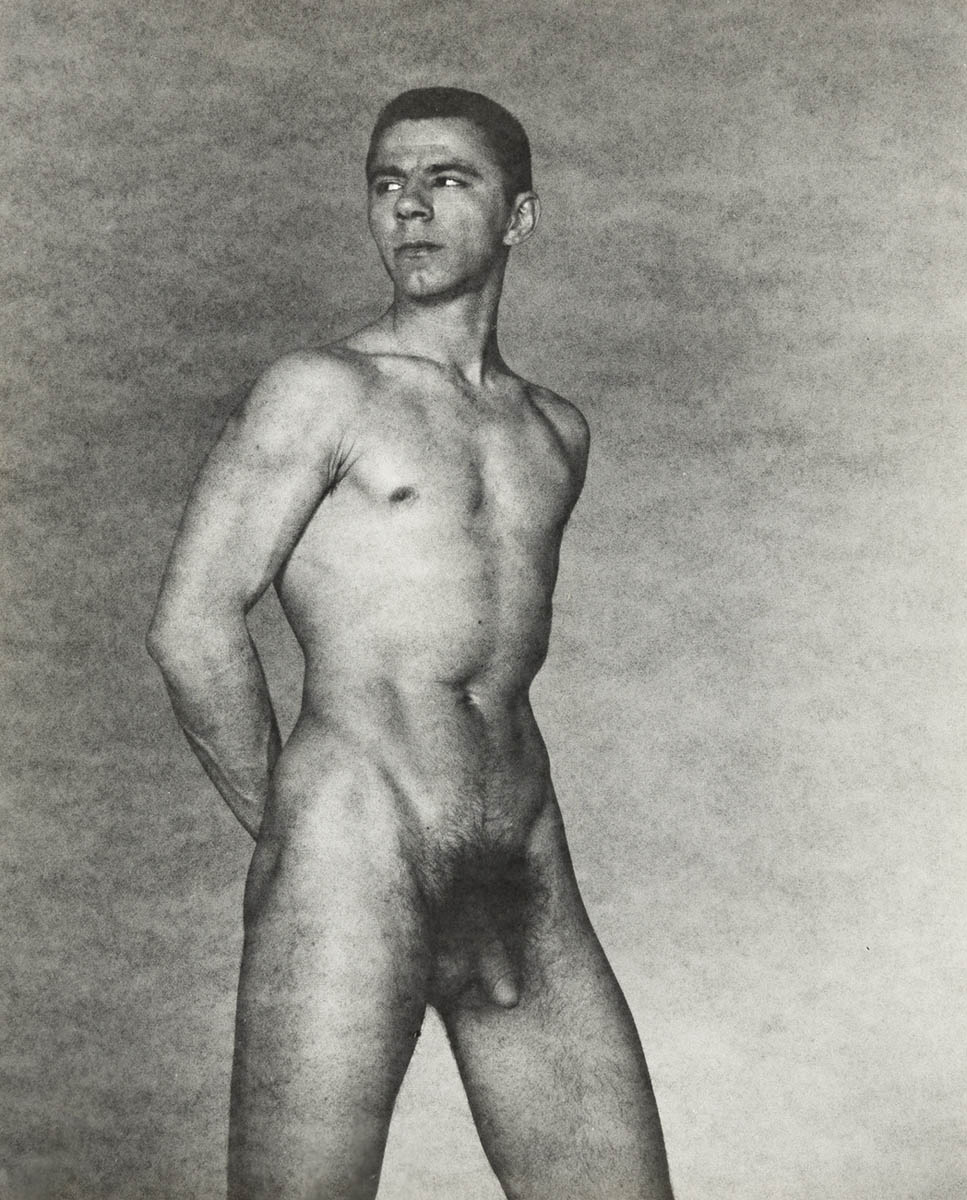

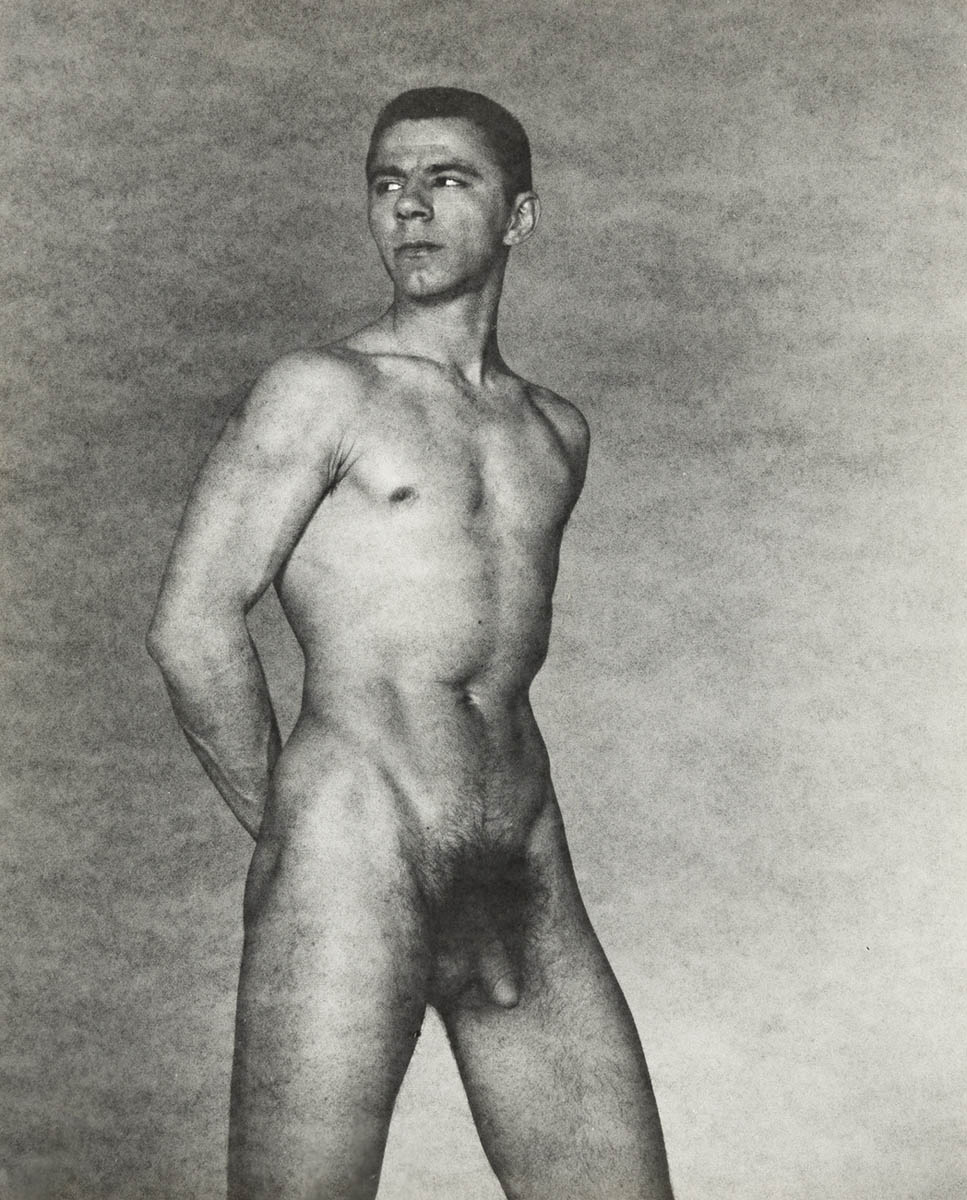

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled [Frontal Male Nude]

Nd

Gelatin silver print

Platt Lynes, George. “Untitled,” Nd in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 103.

Courtesy: Estate of George Platt Lynes.

“The depth and commitment he had in photographing the male nude, from the start of his career to the end, was astonishing. There was absolutely no commercial impulse involved – he couldn’t exhibit it, he couldn’t publish it.”

Allen Ellenzweig. Introduction to George Platt Lynes: The Male Nudes. Rizzoli, 2011.

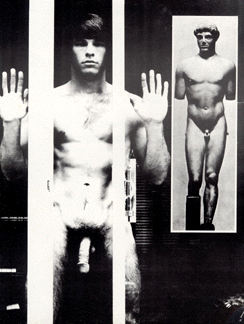

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled

Date unknown (early 1950s)

Gelatin silver print

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled

1953

Gelatin silver print

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Ted Starkowski (standing, arms behind back)

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print from a paper negative

The monumentality of body and form was matched by a new openness in the representation of sexuality. There are intimate photographs of men in what seem to be post-coital revere, in unmade beds, genitalia showing or face down showing their butts off (See my description of Untitled Nude, 1946, in the Collection at The Kinsey Institute). Some of the faces in these later photographs remain hidden, as though disclosure of identity would be detrimental for fear of persecution. The “Untitled,” Frontal Male Nude photograph (above) is very ‘in your face’ for the conservative time from which it emerges, remembering it was the era of witch hunts against communists and subversives (including homosexuals).

This photograph is quite restrained compared to one of the most striking series of GPL’s photographs that I saw at The Kinsey Institute which involves an exploration the male anal area. A photograph from the 1951 series can be found in the book titled George Platt Lynes: Photographs from The Kinsey Institute.8 This image is far less explicit than other images of the same model from the same series that I saw during my research into GPL’s photographs at The Kinsey Institute,9 in particular one which depicts the model with his buttocks in the air pulling his arse cheeks apart (See my description of Images 186-194 in the Collection at The Kinsey Institute). After Lynes found out he had cancer he started to send his photographs to the German homoerotic magazine Der Kries under the pseudonym Roberto Rolf,10 and in the last years of his life he experimented with paper negatives, which made his images of the male body even more grainy and mysterious (See the photograph Ted Starkowski (1950, above), and see my notes on Male Nude 1951, in the Collection at The Kinsey Institute).

Personally I believe that Lynes understood, intimately, the different physical body types that gay men find desirable and used them in his photographs. He visited Lon of New York (a photographer of beefcake men) in his studio and purchased photographs of bodybuilders for himself, as did the German photographer George Hoyningen-Huene, another artist who was gay. It is likely that these images of bodybuilders did influence his later compositional style of images of men; it is also possible that he detected the emergence of this iconic male body type as a potent sexual symbol, one that that was becoming more visible and sexually available to gay men.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

Sunbaker

1937

Gelatin silver print

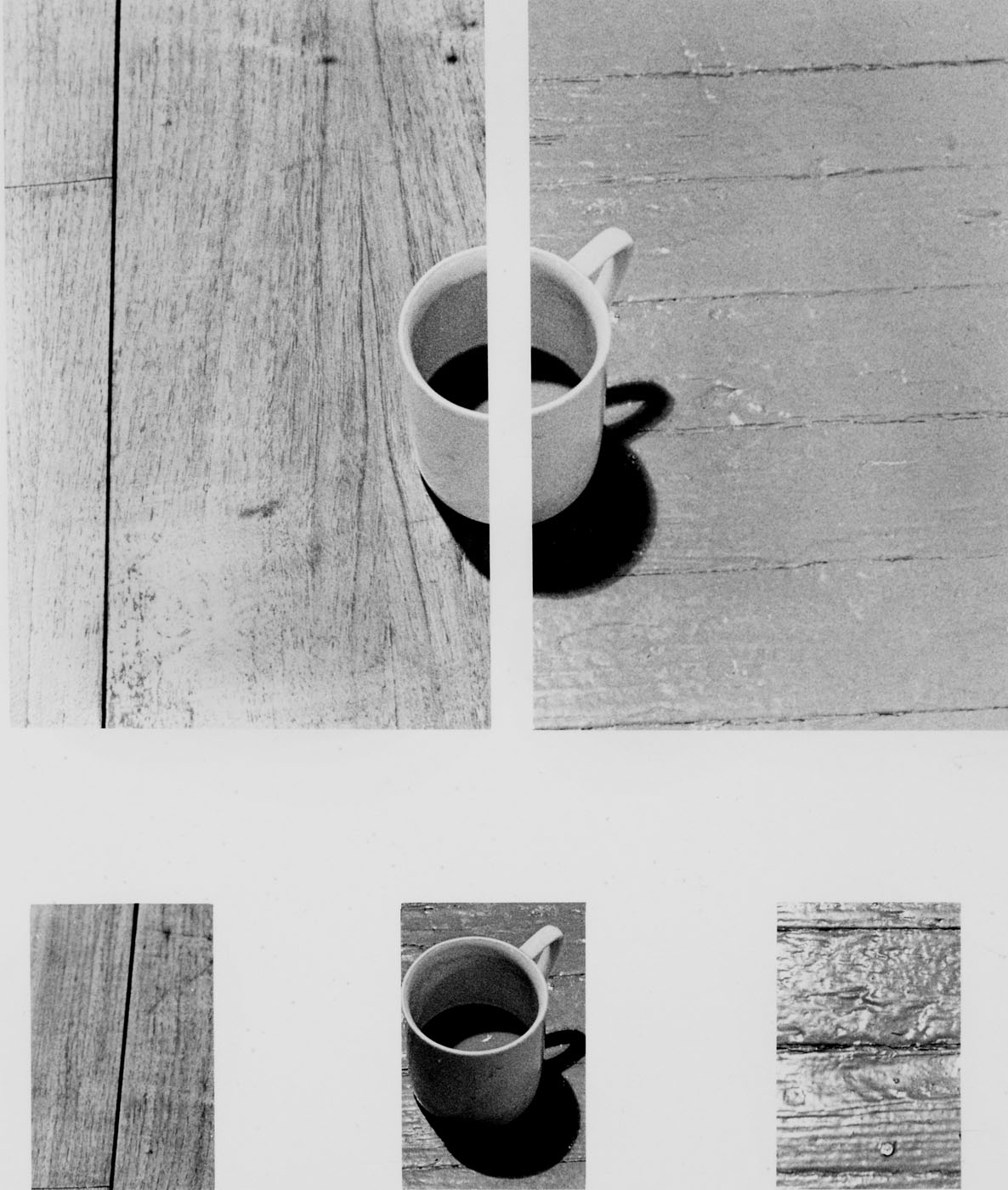

1930s Australian Body Architecture

Around the time that George Platt Lynes was photographing his earlier male nudes Max Dupain took what is seen to be an archetypal photograph of the Australian way of life. Called Sunbaker (1937, above), the photograph expresses the bronzed form of man lying prone on the ground, the man pressing his flesh into the warm sand as the sun beats down on a hot summers day. His hand touches the earth and his head rests, egg-like, on his arm. His shoulders remind me of the outline of Uluru (or Ayres Rock) in the centre of Australia, sculptural, almost cathedral like in their geometry and outline, soaring into the sky. Here the male body is a massive edifice, towering above the eye line, his body wet from the sea expressing the essence of Australian beach culture. In this photograph can be seen evidence of an Australian tradition of photographing hunky lifesavers and surfies to the delight of a gay audience which reached a peak in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, although I’m not sure that Max Dupain would have realised the homoerotic overtones of the photograph at the time.

Minor White

Another photographer haunted by his sexuality was the American Minor White. Disturbed by having been in battle in the Second World War and seeing some of his best male friends killed, White’s early photographs of men (in their uniforms) depict the suffering and anguish that the mental and physical stress of war can cause. He was even more upset than most because he was battling his own inner sexual demons at the same time, his shame and disgust at being a homosexual and attracted to men, a difficulty compounded by his religious upbringing. In his photographs White both denied his attraction to men and expressed it. His photographs of the male body are suffused with both sexual mystery and a celebration of his sexuality despite his bouts of guilt. After the war he started to use the normal everyday bodies of his friends to form sequences of photographs, sometimes using the body as a metaphor for the landscape and vice versa. Based on a religious theme the 1948 photograph Tom Murphy (San Francisco) (1948, below) from The Temptation of Saint Anthony is Mirrors, 1948, presents us with a dismembered hairy body front on, the hands clutching and caressing the body at the same time, the lower hand hovering near the exposed genitalia. As in the photographs of Platt Lynes we see the agony and ecstasy of a homo-erotic desire wrapped up in a religious or mythological theme.

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Tom Murphy (San Francisco)

1948

From The Temptation of Saint Anthony is Mirrors 1948

Gelatin silver print

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Nude Foot, San Francisco

1947

Gelatin silver print

Other images (such as Nude Foot 1947, above) seem to have an aura of desire, mysticism, vulnerability and inner spirituality. White photographed when he was in a state of meditation, hoping for a “revelation,” a revealing of spirit in the subsequent negative and finally print. Perhaps this is why the young men in his photographs always seem vulnerable, alone, available, and have an air of mystery – they reflect his inner state of mind, and consequently express feelings about his own sexuality. In reading through my research notes on his photographs at The Minor White Archive, I notice that I found them a very intense, rich and rewarding experience. It was amazing to find Minor White photographs of erect penises dating from the 1940s amongst the archive but even more amazing was the presence that these photographs had for me. The other overriding feeling was one of perhaps loneliness, sadness, anguish(?), for the bodies seemed to be just observed and not partaken of. As with Platt Lynes photographs of men, very few of Minor White’s male portraits were ever exhibited in his lifetime because of his fear of being exposed as a homosexual.

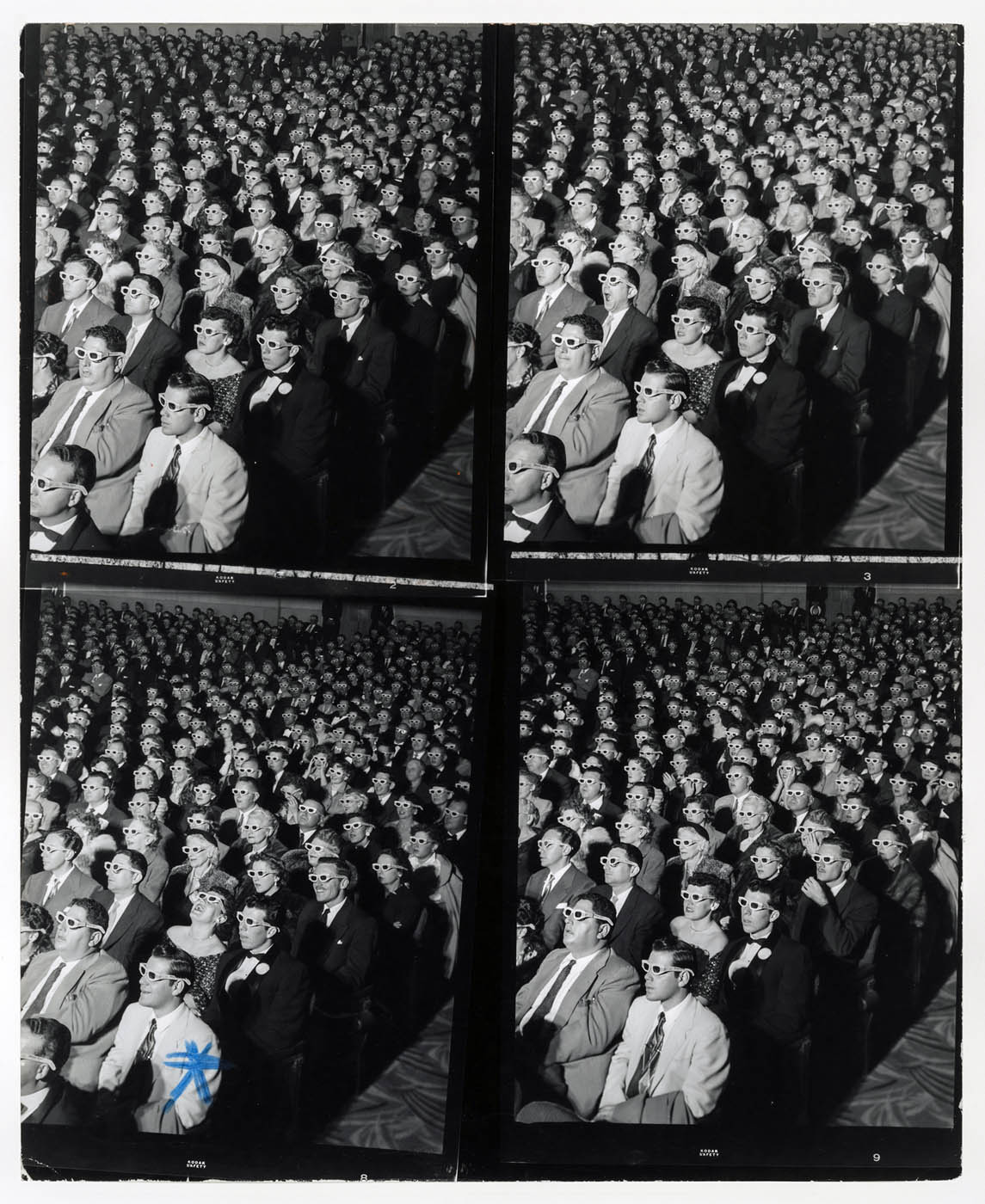

Physique Culture after WW2

At the same time that Minor White was exploring anxieties surrounding his sexuality and his war experiences, many other American men were returning home from WWII to America to find that they had to reaffirm the traditional place of the male as the breadwinner within the family unit. Masculinity and a muscular body image was critical in this reaffirmation. Powerful in build and strong in image it was used to counter the threat of newly independent females, females who had taken over the jobs of men while they were away at war. Conversely, many gay men returned home to America after the war knowing that they were not as alone as they had previously thought, having socialised, associated, fought and had sex with others of their kind. There were other gay men out there in the world and the beginnings of contemporary gay society started to be formed. A desire by some gay men for the masculine body image found expression in the publications of body-building books and magazines that continued to be produced within the boundaries of social acceptability after the Second World War.

Photographers such as Russ Warner, Al Urban, Lon of New York (who began their careers in the late 1930’s), Bob Mizer (started Physique Pictorial in 1945), Charles Renslow (started Kris studio in 1954), and Bruce of Los Angeles, sought out models on both sides of the Atlantic (See my notes on the images of some of these photographers held in the Collection at the Kinsey Institute). Models appeared in posing pouches or the negatives were again airbrushed to hide offending genitalia. Some unpublished images from 1942-1950 by Bruce of Los Angeles show an older man sucking off a stiff younger man (See my notes on Images No. 52001-52004 from the link above) but this is the rare exception rather than the rule.

Bob Mizer (American, 1922-1992) / Athletic Model Guild

Irwin Kosewski and Jerry Ross

Nd

Mizer, Bob/Athletic Model Guild. “Irwin Kosewski and Jerry Ross,” Nd, in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography. Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. 19.

Joe Corey

Bill Henry and Bob Baker

Nd

Corey, Joe. “Bill Henry and Bob Baker,” Nd, in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography. Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. 27.

Appealing to a closeted homosexual clientele the published images seem, on reflection, to have had a more open, homo-erotic quality to them than earlier physique photographs. This can be observed in the two undated images, “Irwin Kosewski and Jerry Ross,” by Bob Mizer / Athletic Model Guild and “Bill Henry and Bob Baker,” by Joe Carey (both above). The first image carries on the tradition of the Sansone image “The Slave,” but further develops the sado-masochistic overtones; such wrestling photographs became popular just because the models were shown touching each other, which could provide sexual arousal for gay men looking at the photographs.

Some photographs were taken out of doors instead of always in the studio, possibly an expression of a more open attitude to ways of depicting the nude male body. The bodies in the ‘beefcake’ magazines of the 1950’s tend to be bigger than that of the ephebe, even when the models were quite young in some cases. As the name ‘beefcake’ implies, the muscular mesomorphic shape was the attraction of these bodies – perfectly proportioned Adonis’s with bulging pectorals, large biceps, hard as rock abdomens and small waists. The 1950’s saw the beginning of the fixation of gay men with the muscular mesomorph as the ultimate ideal image of a male body. The lithe bodies of young dancers and swimmers now gives way to muscle – a built body, large in its construction, solid and dependable, sculpted like a piece of rock. These bodies are usually smooth and it is difficult to find a hirsute body11 in any of the photographs from the physique magazines of this time. According to Alan Berube in his book, Coming Out Under Fire,

“The post-war growth and commercialization of gay male erotica in the form of mail-order 8 mm films, photographic stills, and physique magazines were developed in part by veterans and drew heavily on World War II uniforms and iconography for erotic imagery.”12

Looking through images from the 1940s in the collection at The Kinsey Institute, I did find that uniforms were used as a fetish in some of the explicitly erotic photographs as a form of sexual iconography. These photographs of male2male sex were for private consumption only. I found little evidence of the use of uniforms as sexual iconography in the published photographs of the physique magazines. Here image composition mainly featured classical themes, beach scenes, outdoor and studio settings.

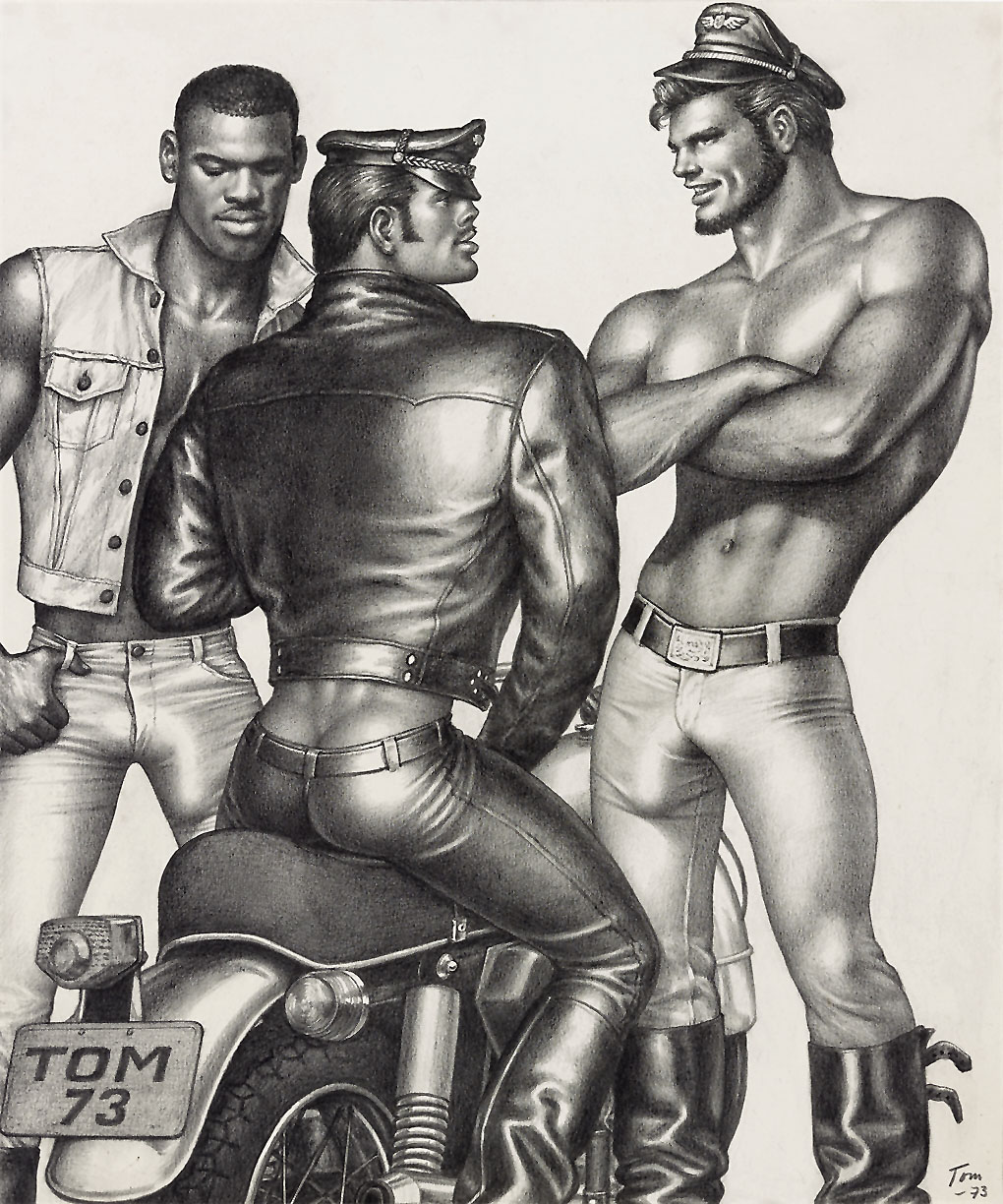

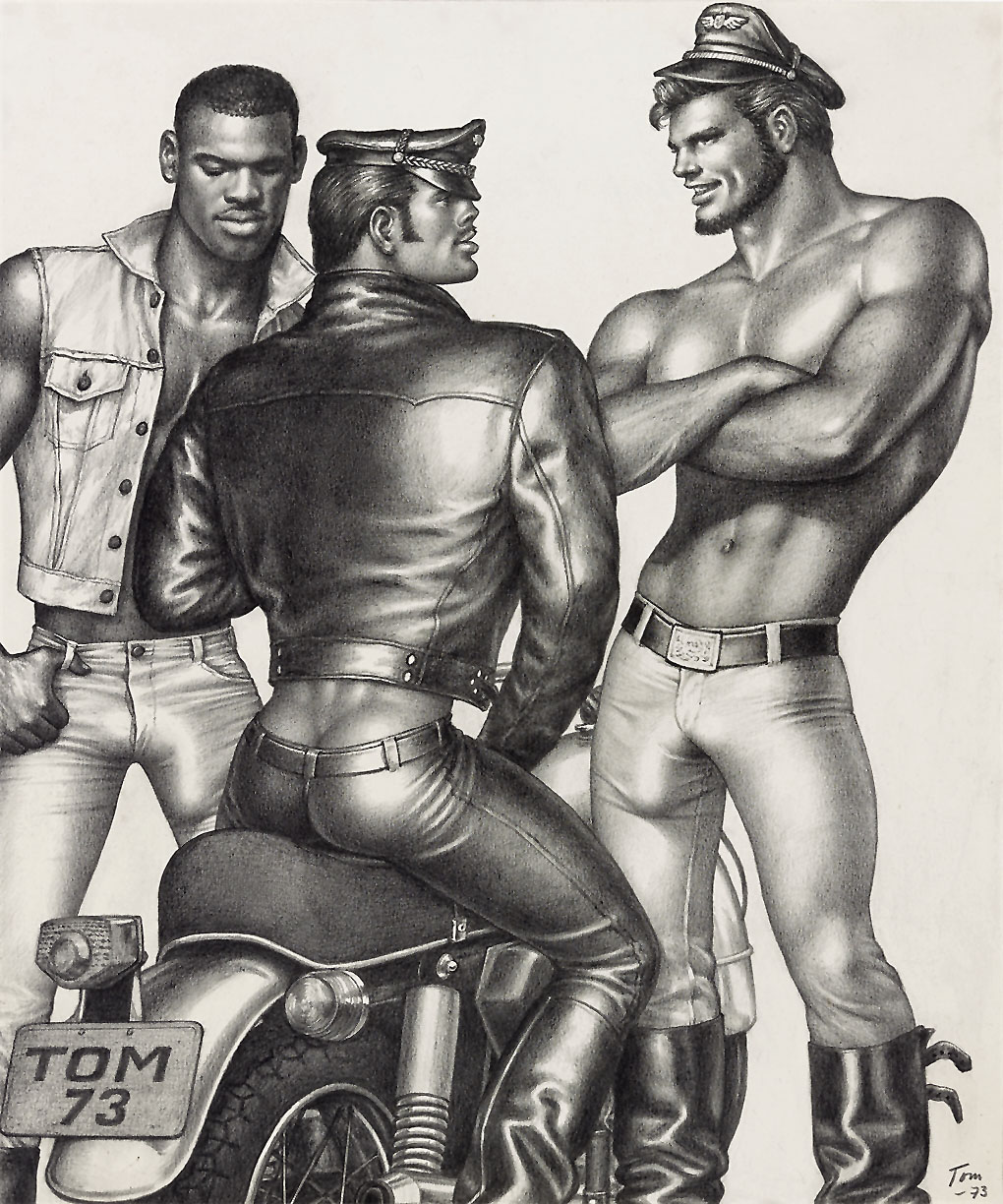

Touko Valio Laaksonen (Tom of Finland) (Finnish, 1920-1991)

Untitled

1973

Physique Pictorial Volume 7, Number 1, Spring 1957. Tom of Finland, Touko Laaksonen (cover)

This issue features the debut American appearance of “Tom, a Finnish artist,” a.k.a. Tom of Finland who produced both the cover illustration of loggers and an interior companion shot.

Bob Mizer (American, 1922-1992) / Athletic Model Guild

Cover of Physique Pictorial Vol. 14, No. 2, 1964

32 pages, black and white illustrations

Illustrated saddle-stapled self-wrappers

21cm x 13cm

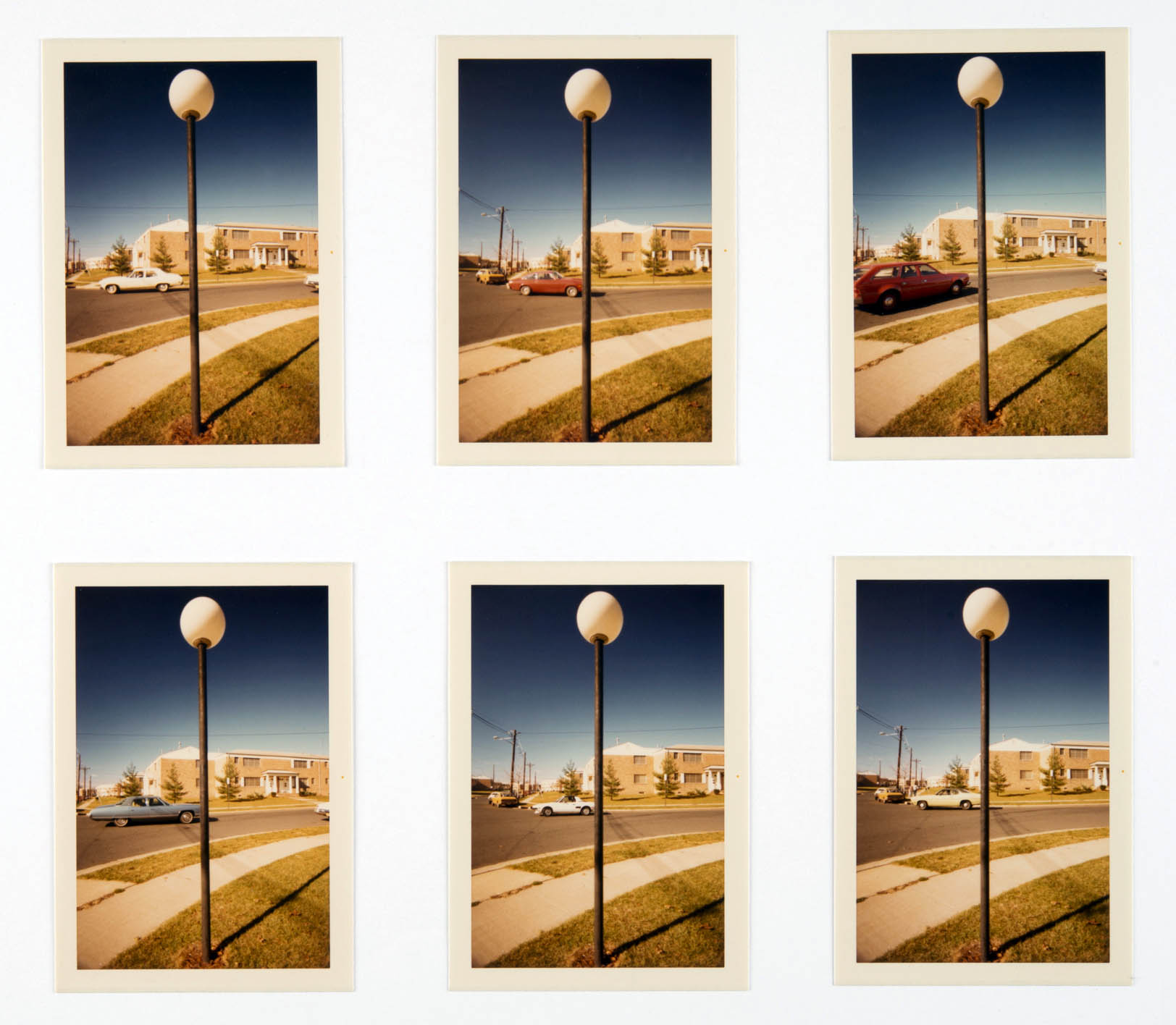

Tom of Finland

Although not a photographer one gay artist who was heavily influenced by the uniforms and muscularity of soldiers he lusted after and had sex with during the war was Touko Laaksonen, known as ‘Tom of Finland’. His images featured hunky, leather clad bikers, sailors, and rough trade ploughing their enlarged, engorged penises up the rears of chunky men in graphic scenes of male2male sex. His images portrayed gay men as the hard-bodied epitome of masculinity, contrary to the nancy boy image of the limp wristed poof that was the stereotype in the hetero / homosexual community up until the 1960s and even later. His early images were again only for private consumption. His first success was a (non-sexual) drawing of a well built male body that he sent to America. It appeared on the cover of the spring 1957 issue of Physique Pictorial (above). Here we see a link between the drawings of Tom of Finland and the construction of a body engineered towards selling to a homosexual market, the male body as marketable commodity. His drawings of muscular men were influenced by the bodies in the beefcake magazines and the bodies of the soldiers he desired. Tom of Finland, in an exaggerated way, portrayed the desirability of this type of body for gay men by emphasising that, for him, gay sex and gay bodies are ultimately ‘masculine’.

1950s Australia

Very little of this iconography of the muscular male was available to gay men in Australia throughout the 1950’s. The few publications that became available were likely to have come from America or the United Kingdom. Instead heterosexual photographers such as Max Dupain took images of Australian beach culture such as the 1952 image At Newport, Australia, 1952 (below). Dupain took a series of photographs of this beautiful young man, ‘the lad’ as he calls him,13 climbing out of the pool. Elegant in its structural form ‘the lad’ is oblivious to the camera’s and our gaze. Although the body is toned and tanned this body image is a much more ‘natural’ representation of the male body than the photographs in the physique magazines, with all their posing and preening for the camera.

Max Dupain (Australian, 1911-1992)

At Newport, Australia, 1952

1952

Gelatin silver print

Dupain, Max. “At Newport, Australia, 1952.” 1952, in Bilson, Amanda (ed.,). Max Dupain’s Australia. Ringwood: Viking, 1986, p. 157.

John Graham

Clive Norman

Nd

Graham, John. “Clive Norman,” Nd in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. 38.

John Graham

Detail from Parthenon Frieze

Elgin Marble Friezes, British Museum

Nd

Lon of New York in London

Jim Stevens

Nd

Graham, John. “Detail from Parthenon Frieze.” Elgin Marble Friezes, British Museum, Nd in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography. Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. vi.

Lon of New York in London. “Jim Stevens,” Nd in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography. Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. 13.

Later Physique Culture and gay pornography photographs

Images of the body in the physique magazines of the 1940s-1960s are invariably smooth, muscular and defined. A perfect example of the type can be seen in the undated image Clive Norman by John Graham (above). The images rely heavily on the iconography of classical Rome and Greece to legitimise their homo-erotic overtones. Use was made of columns, drapery, and sets that presented the male body as the contemporary equivalent of idealised male beauty of ancient times.

As the 1950s turned into the 1960s other stereotypes became available to the photographers – for example the imagery of the marine, the sailor, the biker, the boy on a tropical island, the wrestler, the boxer, the mechanic. The photographs become more raunchy in their depiction of male nudity. In the 1950s, however, classical aspirations were never far from the photographers minds when composing the images as can be seen in the undated photograph Jim Stevens by Lon of New York in London (above) taken from a book called Art in Physique Photography.14 This book, illustrated with drawings of classical warrior figures by David Angelo, is subtitled: ‘An Album of the world’s finest photographs of the male physique’.

Here we observe a link between art and the body. This connection was used to confirm the social acceptability of physique photographs of the male body while still leaving them open to other alternative readings. One alternative reading was made by gay men who could buy these socially acceptable physique magazines to gaze with desire upon the naked form of the male body. It is interesting to note that with the advent of the first openly gay pornography magazines after the ruling on obscenity by the Supreme Court in America in the late 1960s (See my research notes on this subject from The One Institute),15 classical figures were still used to justify the desiring gaze of the camera and viewer upon the bodies of men. Another reason used by early gay pornography magazines to justify photographs of men having sex together was that the images were only for educational purposes!

Even in the mid 1970s companies such as Colt Studios, which has built a reputation for photographing hunky, very well built masculine men, used classical themes in their photography of muscular young men. Most of the early Colt magazines have photographs of naked young men that are accompanied by photographs and illustrations based on classical themes as can be seen in the image below. In their early magazines quite a proportion of the bodies were hirsute or had moustaches as was popular with the clone image at the time. Later models of the early 1980s tend towards the buff, tanned, stereotypical muscular mesomorph in even greater numbers. Sometimes sexual acts are portrayed in Colt magazines but mainly they are not. It is the “look” of the body and the face that the viewers desiring gaze is directed towards – not the sexual act itself. As the Colt magazine says,

“Our aim in Olympus is to wed the classic elegance of ancient Greece and Rome to the contemporary look of the ’70s. With some models that takes some doing: they may have one or two exceptional features, but the overall picture doesn’t make it … Erron, our current subject, comes closer to the ideal – in his own way … Erron stands 5’10”. He is 22 years old and is the spirit of the free-wheeling, unhampered single stud … And to many the morning after, he is ‘the man that got away’.”16

Anonymous photographer

Erron

Olympus from Colt Studios Vol. 1. No 2.

1973

Erron does attempt to come closer to the ‘ideal’ but not, I think, in his own way for it is an ‘ideal’ based on a stereotypical masculine image from a past culture. Is he doing his own thing or someone else’s thing, based on an image already prescribed from the past?

As social morals relaxed in the age of ‘free love’, physique photographers such as Bob Mizer from Athletic Model Guild produced more openly homo-erotic images. In his work from the 1970s full erections are not prevalent but semi-erect penises do feature, as do revealing “moon” shots from the rear focusing on the arsehole as a site for male libidinal desires. A less closeted, more open expression of homosexual desire can be seen in the photographs of the male body in the 1970s.17 What can also be seen in the images of gay pornography magazines from the mid 1970s onwards is the continued development of the dominant stereotypical ‘ideal’ body image that is present in contemporary gay male society – that of the smooth, white, tanned, muscular mesomorphic body image.

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

Muscle Man in his dressing room with trophy, Brooklyn, N.Y.

1962

Gelatin silver print

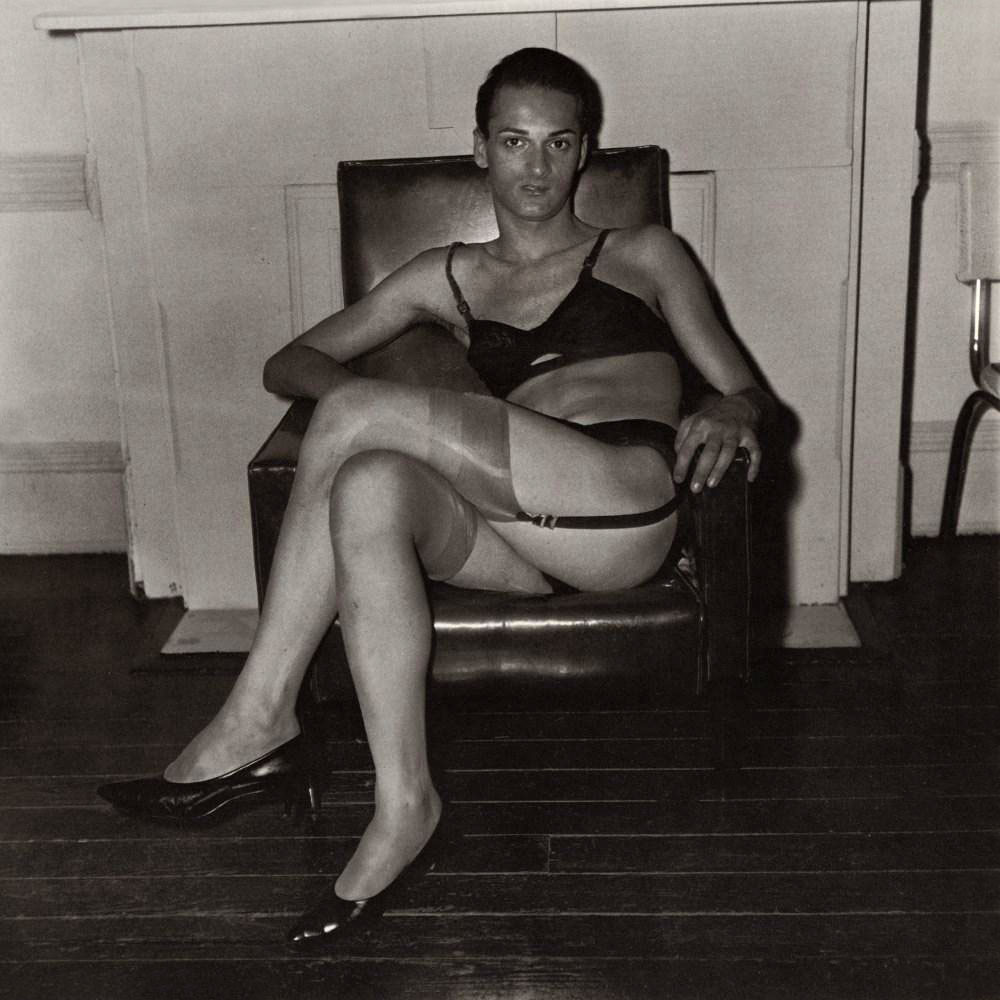

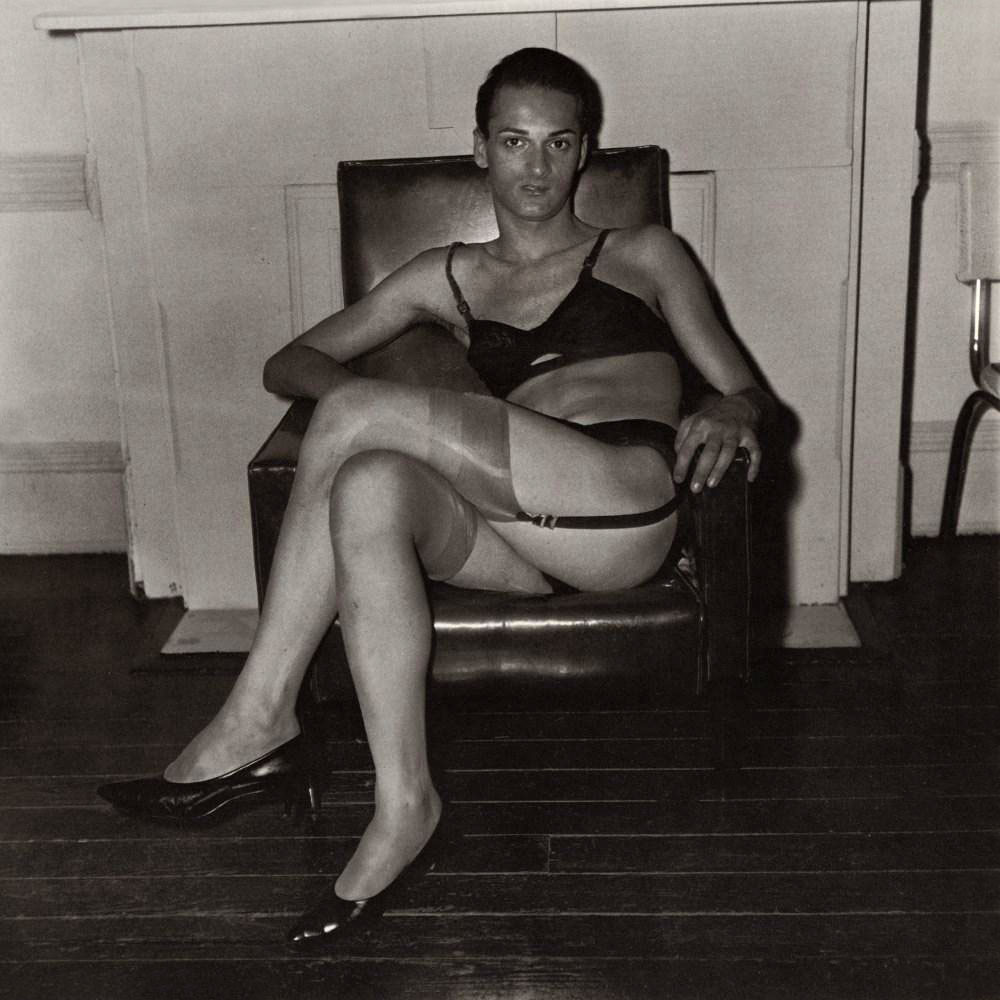

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

Seated man in a bra and stockings, N.Y.C., 1967

1967

Gelatin silver print

Diane Arbus

In the 1960s and 1970s other photographers were also interested in alternative representations of the male body, notably Diane Arbus. Arbus was renowned for ‘in your face’ photographs of the supposed oddities and freaks of society. She photographed body-builders with their trophies, dwarfs, giants, and all sorts of interesting people she found fascinating because of their sexual orientation, hobbies and fetishes. She photographed gay men, lesbians and transsexuals in their homes and hangouts.

I think the image Seated man in a bra and stockings, N.Y.C., 1967 (above), reveals a different side of masculinity, not conforming to the stereotypical depiction of ‘masculinity’ proposed by the form of the muscular body. Yes, the subject is wary of the camera, hand gripping the chair arm, legs crossed in a protective manner. But I think that the important significance of this photograph lies in the fact that the subject allowed himself to be photographed at all, with his face visible, prepared to reveal this portion of his life to the probing of Arbus’ lens. In the closeted and conservative era of the 1960s (remember this is before Gay Liberation), to allow himself to be photographed in this way would have taken an act of courage, because of the fear of discrimination and persecution including the possible loss of job, home, friends, family and even life if this photograph ever came to the attention of employers, landlords and bigots.

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Charles and Jim

1974

Gelatin silver prints

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Charles and Jim, 1974, in Holborn, Mark and Levas, Dimitri. Mapplethorpe Altars. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995, pp. 26-27.

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

White Sheet (detail)

1974

Gelatin silver print

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Detail of White Sheet, 1974, in Holborn, Mark and Levas, Dimitri. Mapplethorpe Altars. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995, p. 74.

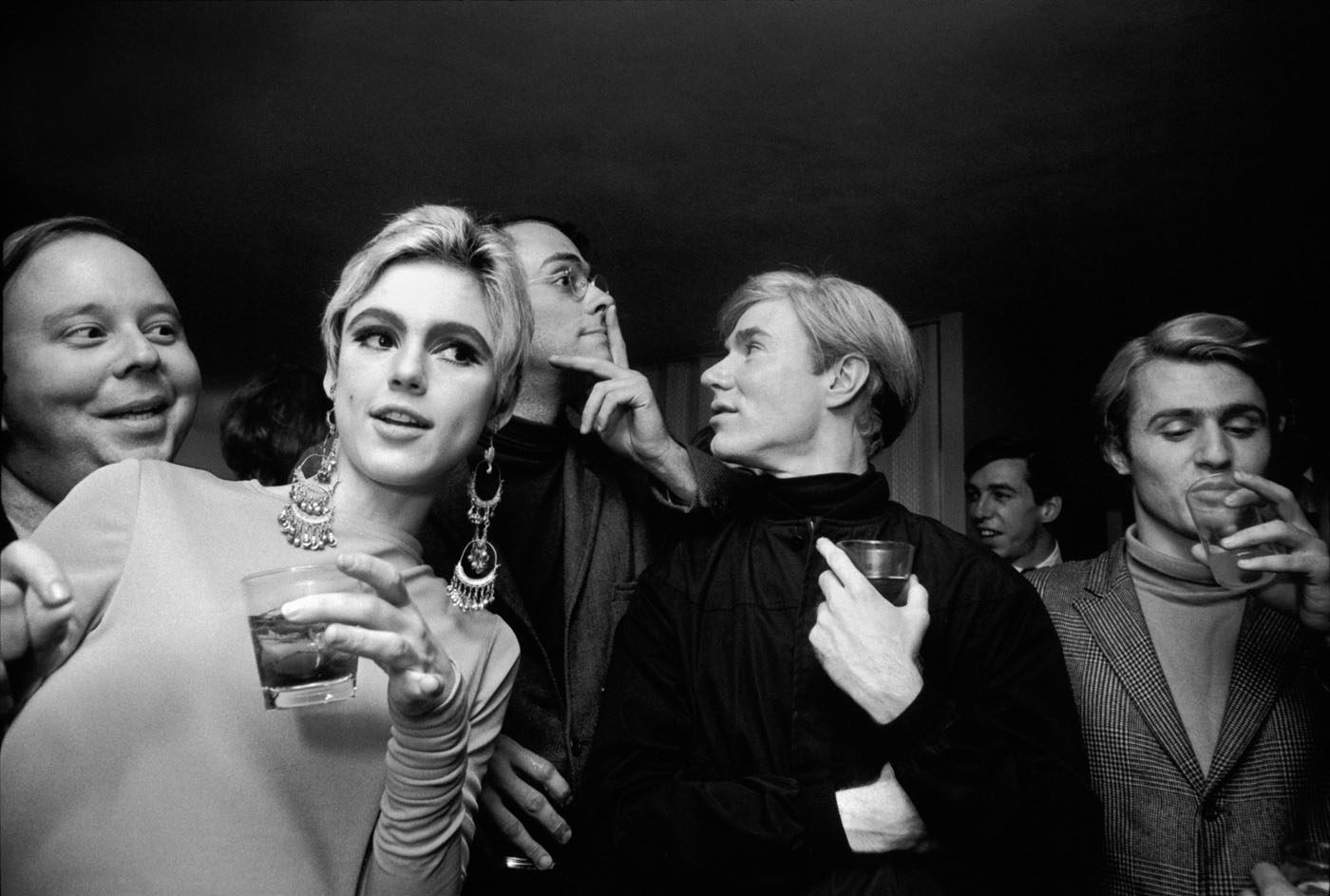

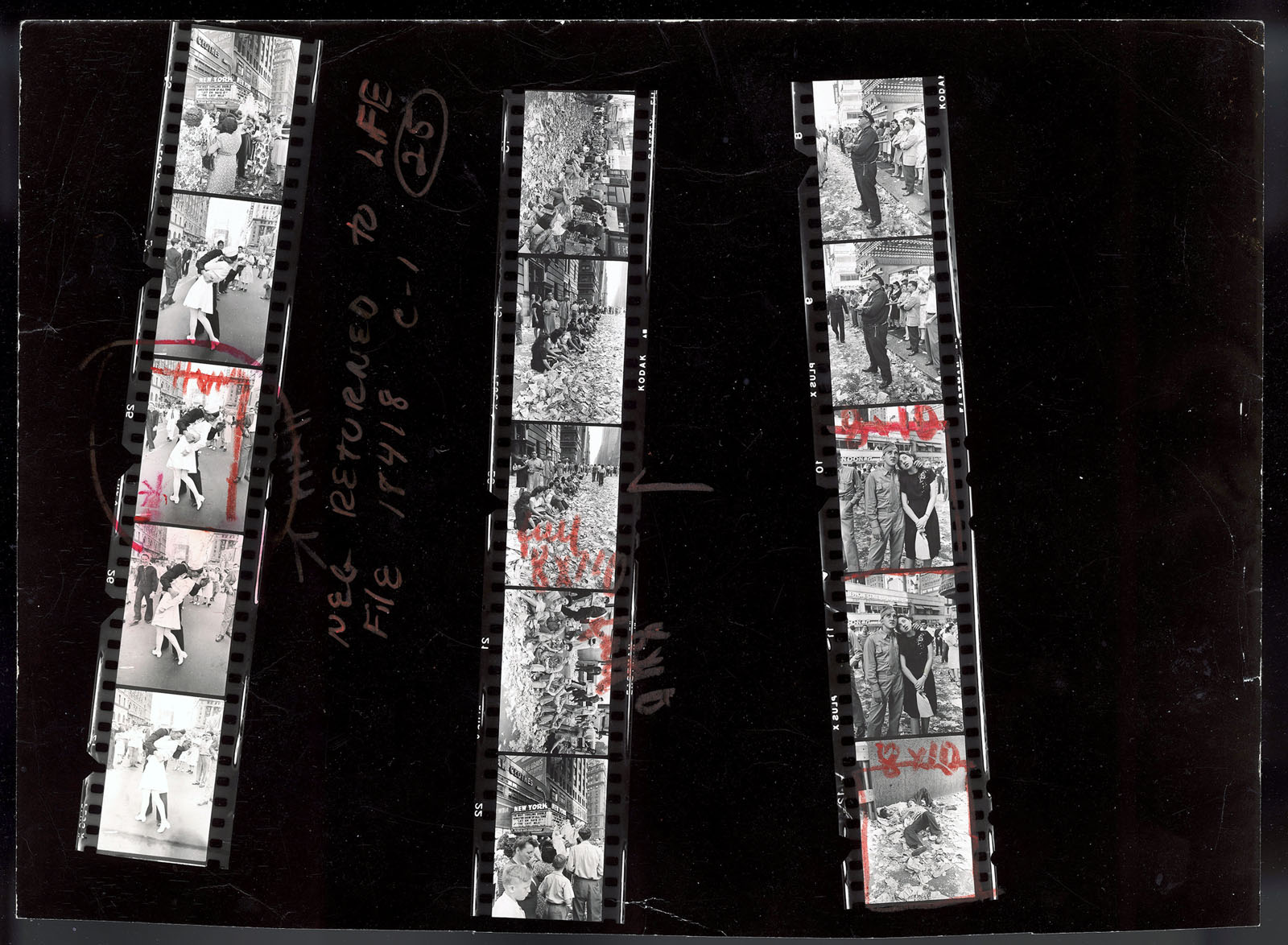

Robert Mapplethorpe

Robert Mapplethorpe. The name of one of the most controversial photographers of the 20th century. Well known to gay men around the world for his ground breaking depiction of sexuality and the body through his photographs of black men and the sadomasochistic acts within the leather scene in gay community. The exhibiting of his images was only possible after the liberation of sexualities brought about by Stonewall and the start of the fight for Gay Liberation in 1969. Early images, such as three from the sequence of photographs Charles and Jim (1974, above) feature ‘natural’ bodies – hairy, scrawny, thin – in close physical proximity with each other, engaged in gay sex, sucking each others dicks in other photographs from this sequence. There is a tenderness and affection to the whole sequence, as the couple undress, suck, kiss and embrace. Compare the photographs with the photograph by Minor White of Tom Murphy (San Francisco) (1948, above) Gone is the religious agony, loneliness and isolation of a man (the photographer), who fears an open expression of his sexuality, replaced by the gaze and touch of a man comfortable with his sexuality and the object of his desire.

Although Mapplethorpe used the bodies of his friends and himself in the early photographs he was still drawn to images of muscular men that had a definite homoerotic quality to them, as can be seen in the detail of the 1974 work White Sheet. Blatant in its hard muscularity the boys stare at each other, flexing their muscles, one arm around the back of the others neck. This attraction to the perfect muscular body became more obvious in the later work of Mapplethorpe, especially in his depiction of black men and their hard, graphic bodies. Mapplethorpe even used to coat his black models in graphite so that the skin took on a grey lustre, adding to the feeling that the skin was made of marble and was impenetrable. Mapplethorpe’s photographs of black men come from a lineage that can be traced back through Frederick Holland Day (see below) to Herbert List and George Platt Lynes who all photographed black men. In the 1979 image of Bob Love (below), Mapplethorpe worships the body and the penis of Bob Love, placing him on a pedestal reminiscent of those used in the physique magazines of an earlier era.

F. Holland Day (American, 1864-1933)

Ebony and Ivory

1899

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Bob Love

1979

Gelatin silver print

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Bob Love, 1979, in Holborn, Mark and Levas, Dimitri. Mapplethorpe Altars. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995, p. 71.

Around the same time that Mapplethorpe was photographing the first of his black nudes he was also portraying acts of sexual pleasure in his photographs of the gay S/M scene. In these photographs the bodies are usually shielded from scrutiny by leather and rubber but are more revealing of the intentions and personalities of the people depicted in them, perhaps because Mapplethorpe was taking part in these activities himself as well as just depicting them. There is a sense of connection with the people and the situations that occur before his lens in the S/M photographs. In the photograph of Bob, however, Bob stares out at the viewer in a passive way, revealing nothing of his own personality, directed by the photographer, portrayed like a trophy. I believe this isolation, this objectivity becomes one of the undeniable criticisms of most of Mapplethorpe’s later photographs of the body – they reveal nothing but the clarity of perfect formalised beauty and aesthetic design, sometimes fragmented into surfaces. Mapplethorpe liked to view the body as though cut up into pieces, into different libidinal zones, much as in the reclaimed artefacts of classical sculpture. The viewer is seduced by the sensuous nature of the bodies surfaces, the body objectified for the viewers pleasure. The photographs reveal very little of the inner self of the person being photographed. This surface quality can also be seen in earlier work such as the 1976 photograph of bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger (1976, below).

Lorenzo Lotto (Italian, c. 1480 – 1556/1557)

Young Man Before a White Curtain

c. 1506/1508

Oil on canvas

Lotto, Lorenzo. Young Man Before a White Curtain, Oil on Canvas. c. 1506/1508, in Schneider, Norbert. The Art of the Portrait. Koln: Benedikt Taschen, 1994, p. 66.

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Arnold Schwarzenegger

1976

Gelatin silver print

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Arnold Schwarzenegger, 1976, in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 139.

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. 1968

1968

Gelatin silver print

Arbus, Diane. A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. 1968, 1968, in An Aperture Monograph. Diane Arbus. New York: Millerton, 1972.

In the photograph Schwarzenegger is placed on bare floorboards with a heavy curtain pulled back to reveal a white wall. We can see connections to an oil painting by the Italian Lorenzo Lotto. According to Norbert Schneider in his book The Art of the Portrait the curtain motif is adapted from devotional painting and was used as a symbolic, majestical backdrop for saints.18 The curtain may be seen as a ‘velum’ to veil whatever was behind it, or by an act of ‘re-velatio’, or pulling aside of the curtain, reveal what is behind. In both the painting and the photograph very little is revealed about the person’s inner self, despite the fact that in Mapplethorpe’s photograph the curtain has been tied back. Schwarzenegger stands before a barren white wall, on bare floorboards. The photograph reveals nothing about his inner self or his state of mind; it is a barren landscape. Nothing is revealed about his personality or identity save that he is a bodybuilder with a body made up of large muscles that has been posed for the camera; his facial expression and look are blank much like the wall behind him. The body becomes a marketable product, the polished surface fetishised in its perfection.

Compare this photograph with the A naked man being a woman, N.Y.C. 1968, by Diane Arbus taken six years earlier (above). Again a figure stands before parted curtains in a room. Here we see an androgynous figure of a man being a woman surrounded by the physical evidence of his/her existence. The body is not muscular but of a ‘natural’ type, one leg slightly bent in quite a feminine gesture, a hand on the hip. Behind the figure is a bed, covered in a blanket. On the chair in front of the curtains and on the bed behind lies discarded clothing and the detritus of human existence. We can also see a suitcase behind the chair leg, an open beer or soft drink can on the floor and what looks like an electrical heater behind the figures legs. We are made aware we are looking at the persons place of living, of sleeping, of the bed where the person sleeps and possibly has sex. Framed by the open curtains the painted face with the plucked eyebrows stares back at us with a much more engaging openness, the body placed within the context of its lived surroundings, unlike the photograph of Schwarzenegger. Much is revealed about the psychological state of the owner and how he lives and what he likes to do. The black and white shading behind the curtains reveals the yin/yang dichotomy, the opposite and the same of his personality far better than the blank white wall that stands behind Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Arnold Schwarzenegger.

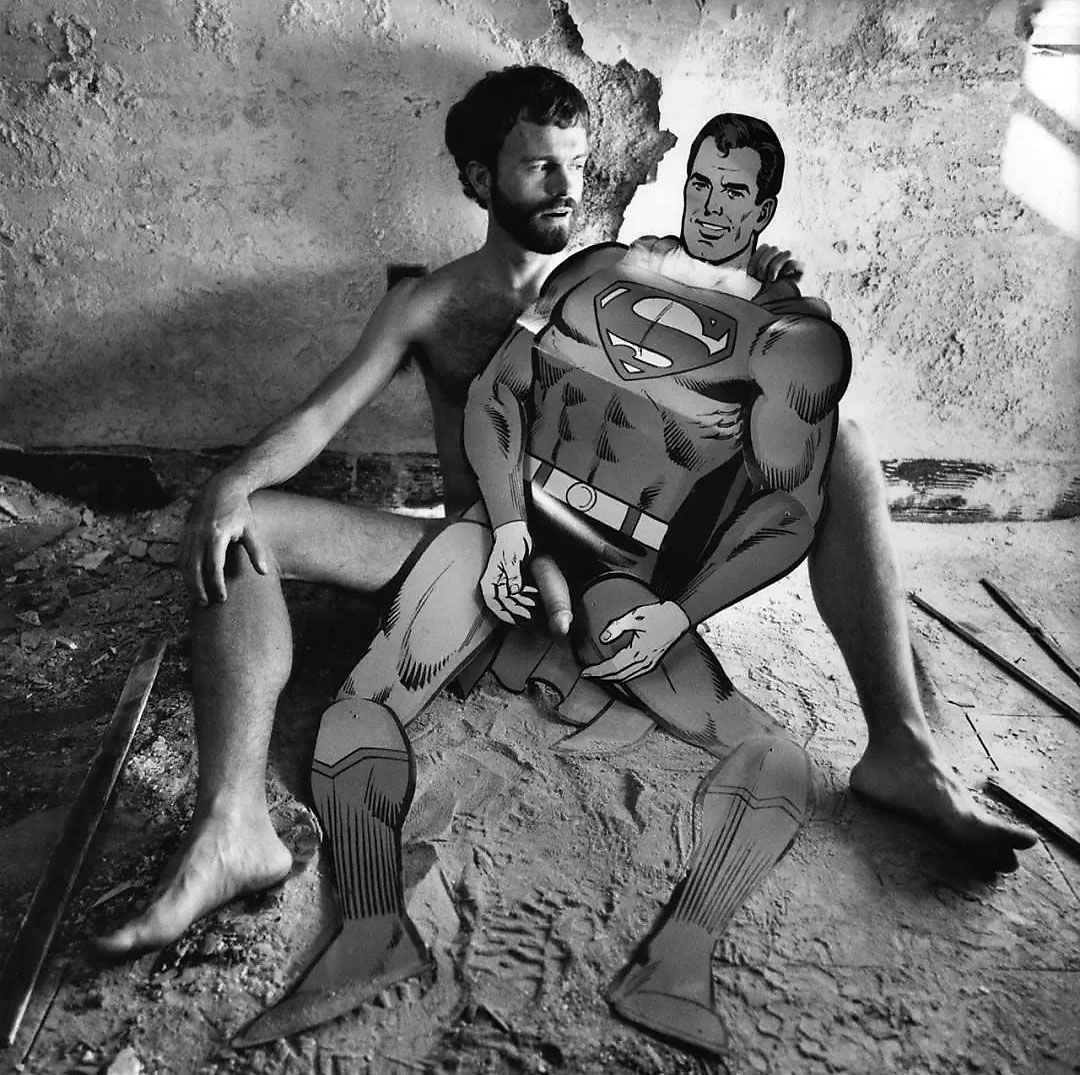

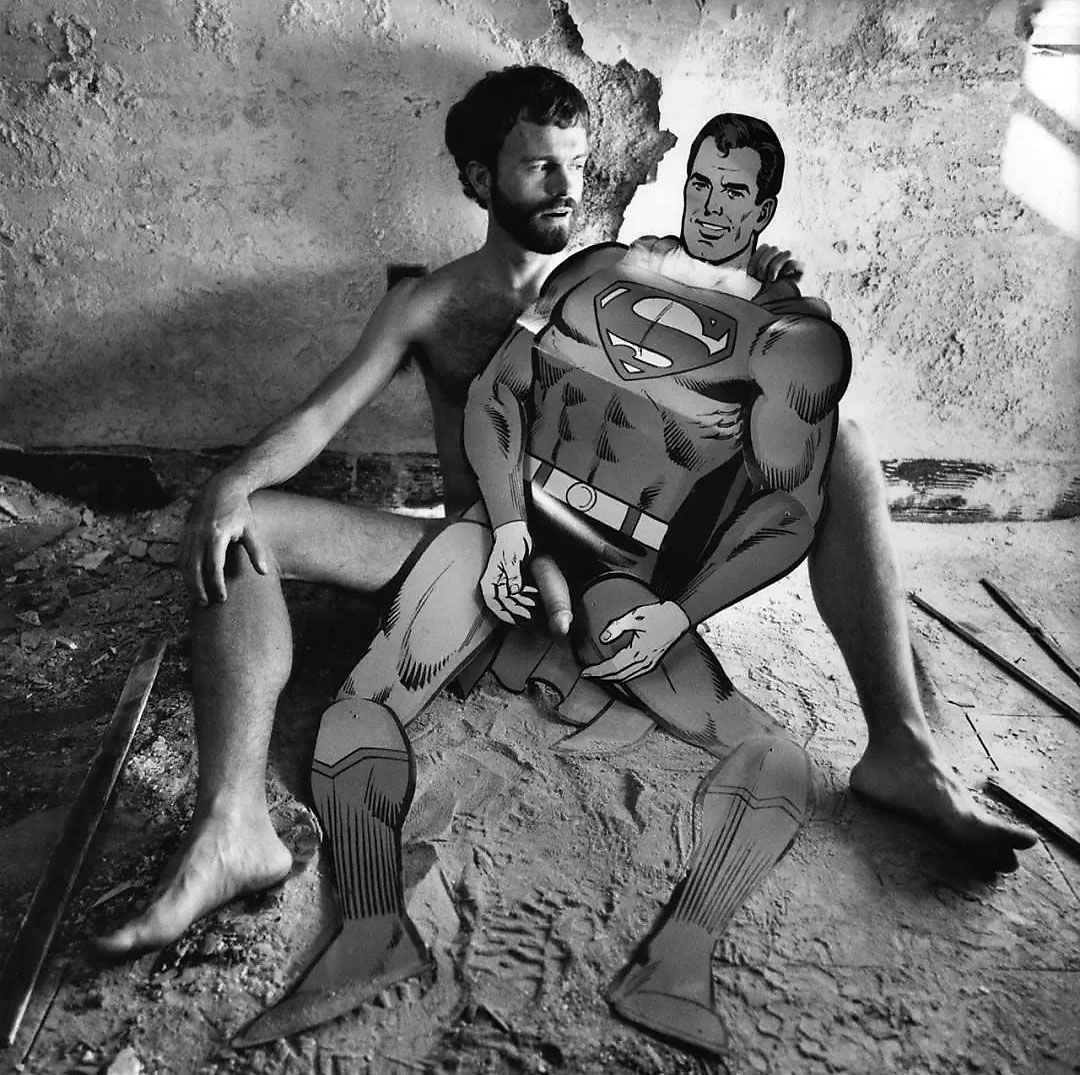

Arthur Tress (American, b. 1940)

Superman Fantasy

1977

Gelatin silver print

Arthur Tress. Superman Fantasy, 1977, in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 143.

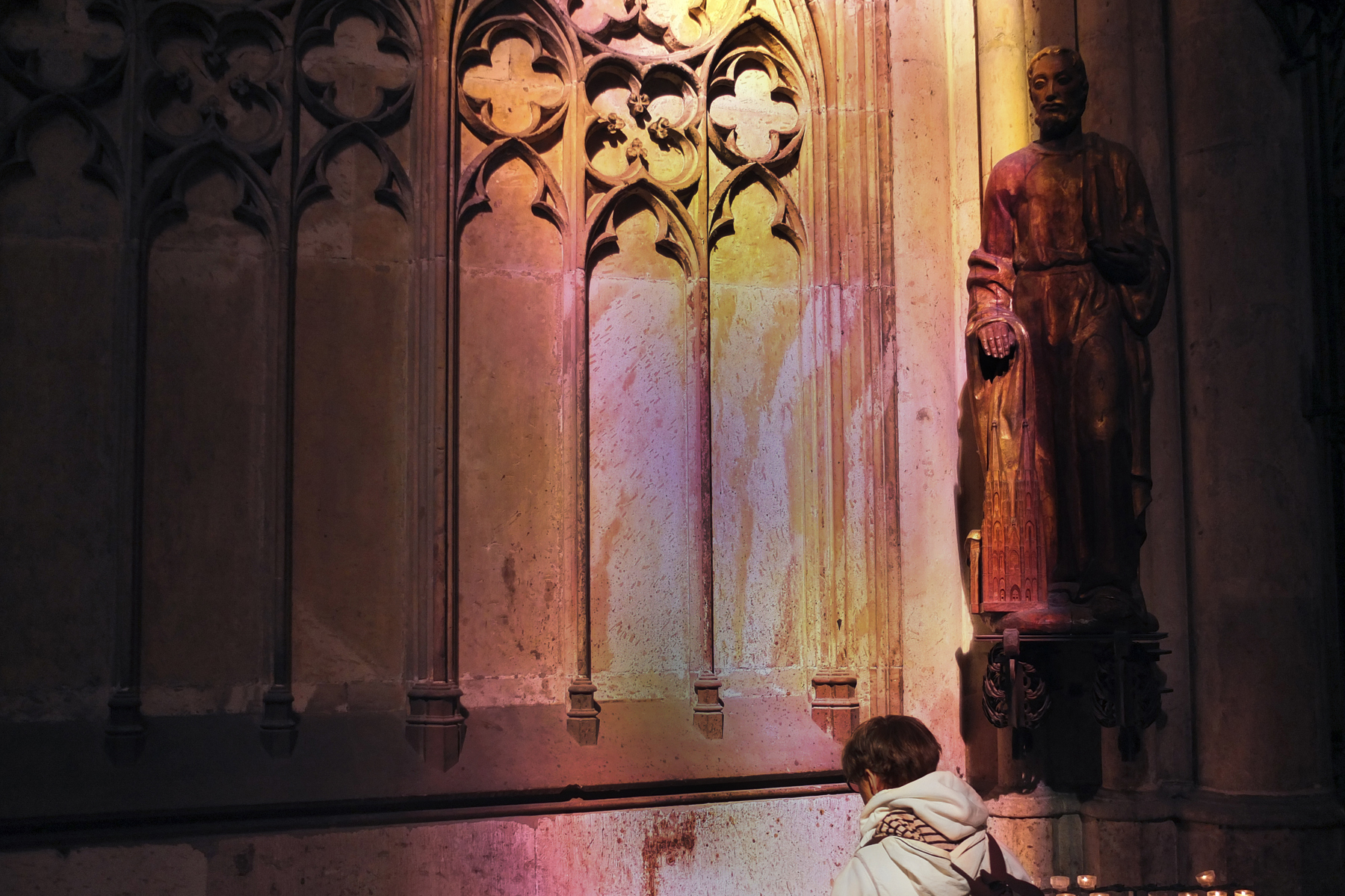

Bill Henson (Australian, b. 1955)

Image No.9 from an Untitled Sequence 1977

1977

Gelatin silver print

Henson, Bill. Image No.9 from an Untitled sequence 1977, 1977, in Henson, Bill. Bill Henson: Photographs 1974-1984. (exhibition catalogue). Melbourne: Deutscher Fine Art, 1989.

Arthur Tress, Bill Henson and Bruce Weber

Arthur Tress was not a photographer that pandered to the emerging “lifestyle” cult of gay masculinity that was beginning to formulate towards the end of the 1970’s and the early 1980’s. Borrowing elements from both a ‘camp’ aesthetic and Surrealism, his images from this time parodied the inner identity of gay men, prodding and poking beneath the surface of both the gay male psyche and their fantasies. In the 1977 image Superman Fantasy (above), Tress conveys the desire of some gay men for the ‘ideal’ of the superhero, powerful, with muscular body and large penis. But the desiree has a ‘natural’ body and it is his penis that projects between the Superman’s thighs. Superman is only a fantasy, a cut out figure with no relief, and Tress pokes fun at gay men who desire heroic masculine body images to reinforce their own sense masculinity.

At the same time in Australia there emerged the work of the photographer Bill Henson. Again, he did not use stereotypical masculine body images. In an early 1977 sequence of his work (above), we see a young man who looks emaciated (almost like a living skeleton) at rest, a moment of stasis while apparently in the act of masturbating. Here Henson links the sexual act (although never seen in the photographs) with death. Visually Henson represents Georges Bataille’s idea that the ecstasy of an orgasm is like the oblivion of death. The body in sex uses power as part of its attraction and the ultimate expression of power is death; this sequence of photographs links the two ideas together visually. With the explicit medical link between sex and death because of the HIV/AIDS virus these photographs have a powerful resonance within a contemporary social context, the emaciated body now associated in people’s minds with a person dying from AIDS.

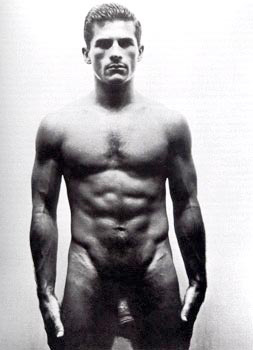

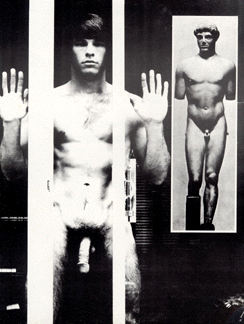

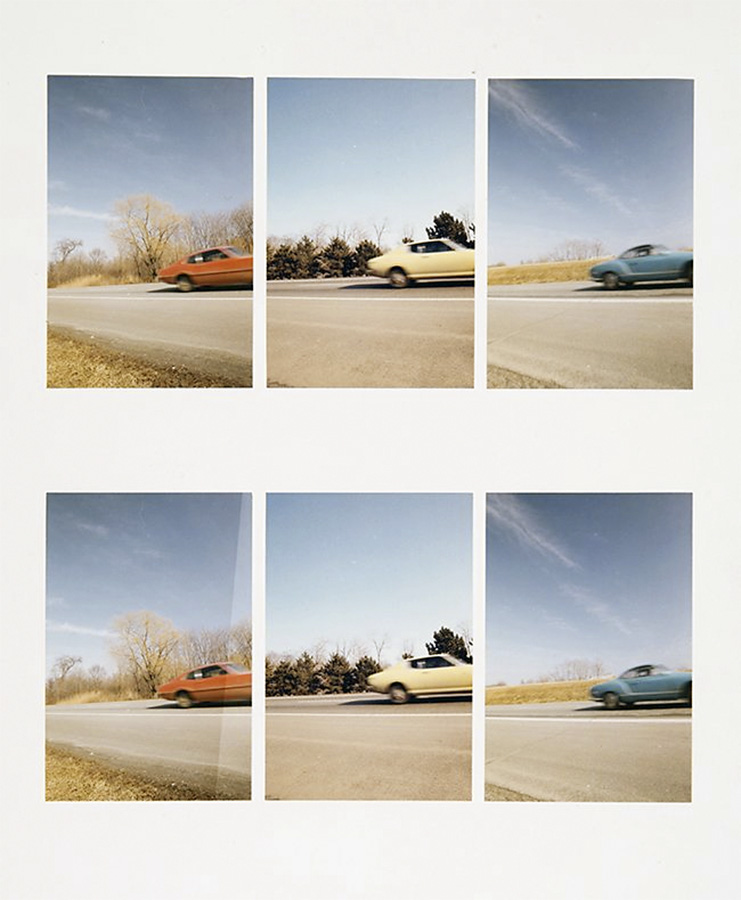

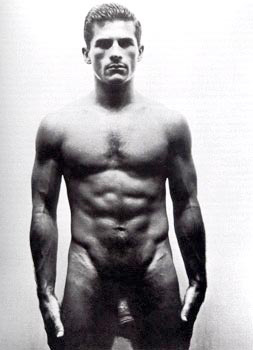

Other photographers, notably Bruce Weber, confirmed the constructed ‘ideal’ of the commodified masculine body. Body became product, became part of an overall purchased “lifestyle,” chic, beautiful and available if you have enough money. Working mainly as a fashion photographer with an aspiration to high art, Weber paraded a plethora of stunning white, buff, muscular males before his lens. Advertising companies, such as Calvin Klein swooped on this image of perfect male flesh and played with the ambiguous homo-erotic possibilities inherent within the images. Gay men fell for what they saw as the epitome of ‘masculinity’, a reflection of their own “straight-acting” masculinity. These photographs, with a genetic lineage dating from Sansone and the photographs of sportsmen by German photographer Leni Riefenstahl in the 1930’s, are almost utopian in their aesthetic idealisation of the body.

In his personal work, examples of which can be seen below, Bruce Weber maintains his interest in the perfection of the male form. These men are just All American Jocks, supposedly your everyday boy next door, possessing no sexuality other than a placid, flaccid non-threatening penis, no messy secretions or interactions being attached to the bodies at all. There is no hint of disease or dis-ease among these images or models, even though AIDS was emerging at this time as a major killer of gay men. Perhaps even the possibility of homo/sexuality/identity is denied in the perfection of their form placed, like the Mapplethorpe photograph of Schwarzenegger, against a non-descriptive background, a context-less body in a context-less photograph.

Bruce Weber (American, b. 1946)

Dan Harvey, New York Jets Trainer

1983

Gelatin silver print

Weber, Bruce. Dan Harvey, New York Jets Trainer, 1983, 1983, in Cheim, John. Bruce Weber. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1988.

Bruce Weber (American, b. 1946)

Paul Wadina, Santa Barbara California

1987

Gelatin silver print

Weber, Bruce. Paul Wadina, Santa Barbara, California, 1987, 1987, in Cheim, John. Bruce Weber. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1988.

Herb Ritts (American, 1952-2002)

Fred with Tires

1984

Gelatin silver print

24 × 20 in (61 × 50.8cm)

Ritts, Herb. Fred with Tires, 1984, in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 195.

Herb Ritts, Queer Press, Queer body

Fred with Tires (1984, above) became possibly the archetypal photograph of the male body in the 1980’s and made the world-wide reputation of its commercial photographer, Herb Ritts. Gay men flocked to buy it, including myself. I was drawn by the powerful, perfectly sculpted body, the butchness of his job, the dirty trousers, the boots and the body placed within the social context. At the time I realised that the image of this man was a constructed fantasy, ie., not the ‘real’ thing, and this feeling of having been deceived has grown ever since. His hair is teased up and beautifully styled, the grease is applied to his body just so, his body twisted to just the right degree to accentuate the muscles of the stomach and around the pelvis. You can just imagine the stylist standing off camera ready to readjust the hair if necessary, the assistants with their reflectors playing more light onto the body. This/he is the seduction of a marketable homoeroticsm, the selling of an image as sex, almost camp in its overt appeal to gay archetypal stereotypes. Herb Ritts, whether in his commercial work or in his personal images such as those of the gay bodybuilders Bob Paris and Rod Jackson, has helped increase the acceptance of the openly homo-erotic photograph in a wider sphere but this has been possible only with an increased acceptance of homosexual visibility within the general population. Openly gay bodies such as that of Australian rugby league star Ian Roberts or American diver Greg Luganis can become heroes and role models to young gay men coming out of the closet for the first time, visible evidence that gay men are everywhere in every walk of life. This is great because young gay men do need gay role models to look up to but the bodies they possess only conform to the one type, that of the muscular mesomorph and this reinforces the ideal of a traditional virile masculinity. Yes, the guy in the shower next to you might be a poofter, might be queer for heavens sake, but my God, what a body he’s got!

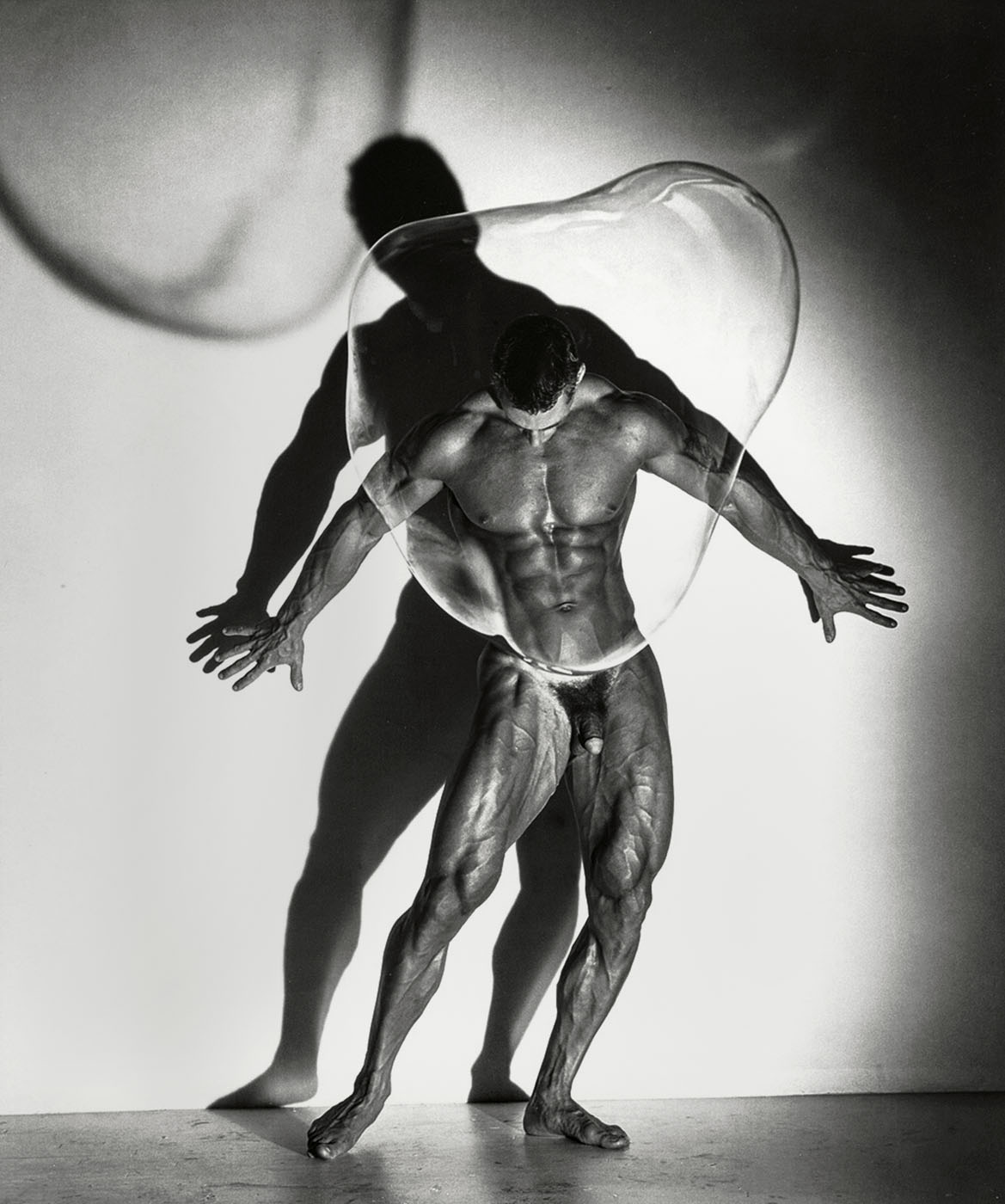

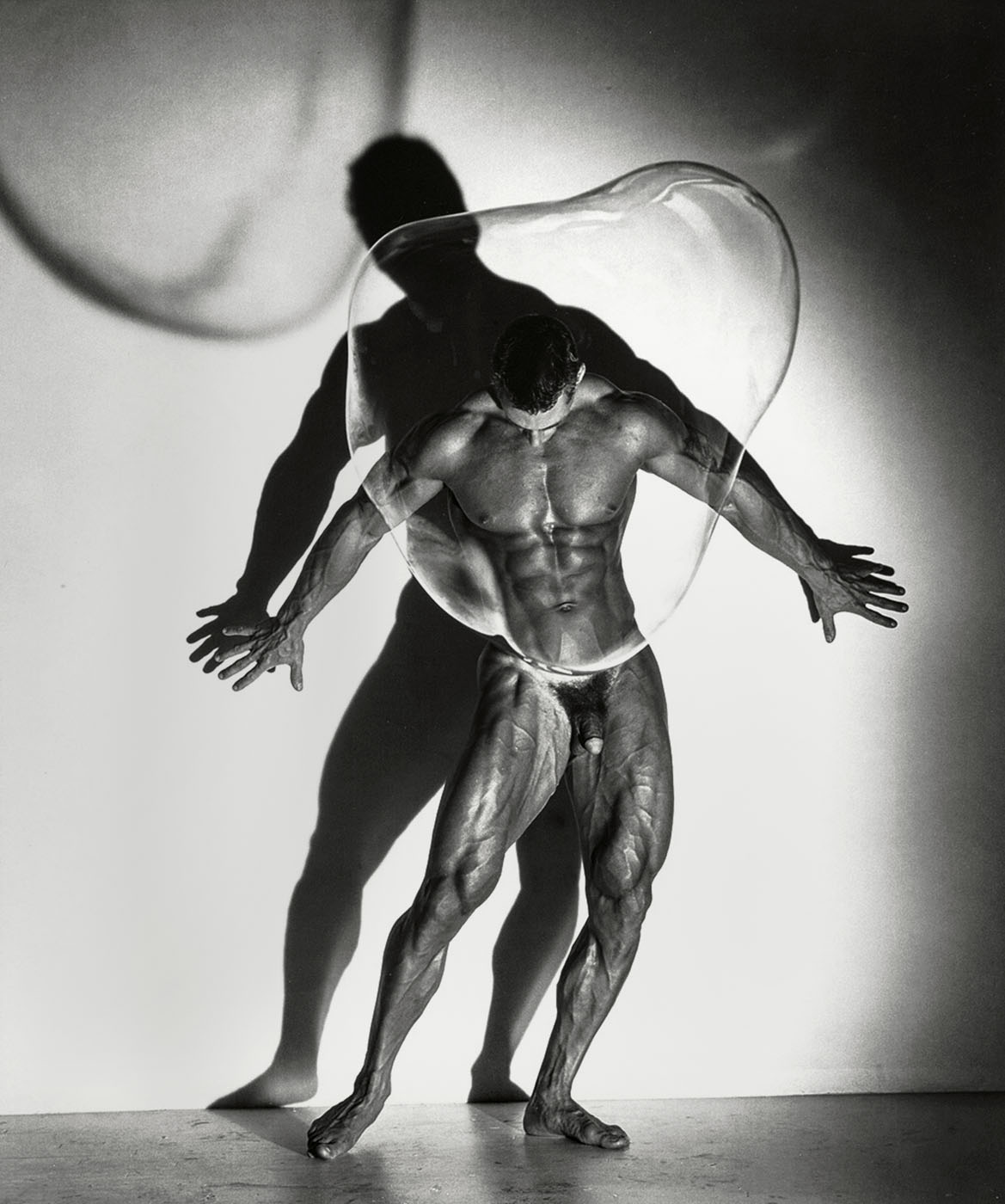

Herb Ritts photographs are still based on the traditional physique magazine style of the 1950’s as can be seen from the examples below. He also borrows heavily from the work of George Platt Lynes and the idealised perfection of Mapplethorpe. The bodies he uses construct themselves (through going to the gym) as the ‘ideal’ of what men should look like. Seduced by the perfection of his bodies gay men have rushed to the gym since the early 1980’s in an attempt to emulate the ideal that Ritts proposes, to belong to the ‘in’ crowd, to have “the look”. (This idealisation continues to this day in 2022).

From different cultures around the world other artists who are gay have also succumbed to the heroic musculature that is the modern day epitome of the representation of gay masculinity. Although he denies any linkage to the work of ‘Tom of Finland’, Sadao Hasegawa portrays the body as a demigod using traditional Japanese and Western iconography to emphasise his themes of homosexual bondage and ritual (see below). The body in his Shunga (Japanese erotic) paintings and drawings, as in most art and images of the muscular male, becomes a phallus, the armoured body being a metaphor for the hidden power of the penis, signifying the power of mesomorphic men over women and ‘other’ not so well endowed men.

Bob Delmonteque (American)

Glenn Bishop

1950s

Gelatin silver print

Delmonteque, Bob. Glenn Bishop, 1950s, in Domenique (ed.,). Art in Physique Photography. Vol. 1. Man’s World Publishing Company. Chesham: The Carlton Press, Nd, p. 8.

Herb Ritts (American, 1952-2002)

Male Nude with Bubble, Los Angeles

1987

Gelatin silver print

Ritts, Herb. Male Nude with Bubble, Los Angeles, 1987, in Ellenzweig, Allen. The Homoerotic Photograph. New York: Columbia University Press, 1992, p. 194.

Sadao Hasegawa (Japanese, 1945-1999)

Untitled

1990

Hasegawa, Sadao. Untitled, 1990, in Blue Magazine. Sydney: Studio Magazines, April 1997, p. 50.

But there are still other artists who are gay who challenge the orthodoxy of such stereotypical images, using as their springboard the ‘sensibility’ of queer theory, a theory that critiques perspectives of social and cultural ‘normality’. With the explosion of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the mid 1980’s, numerous artists started to address issues of the body: isolation, disease, death, beauty, gay sex, friendship between men, the inscription of the bodies surface, and the place of gay men in the world in a critical and valuable way. Ted Gott, commenting on Lex Middleton’s 1992 image Gay Beauty Myth (below) in the book Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS observes that the image,

“… reconsiders Bruce Weber’s luscious photography of the naked male body for Calvin Klein’s celebrated underwear advertising campaigns of the early 1980s. The proliferation of Weber / Klein glistening pectorals and smouldering body tone across the billboards of the United States was reaching its crescendo at the same time as the gay male ‘body’ came under threat from a ‘new’ disease not yet identified as HIV/AIDS. In opposing the rippling musculature and perfect visage of an athlete with the fragmented image of a Calvin Klein Y-fronted ‘ordinary’ man, Middleton questions the ‘gay beauty myth’, both as it touches gay men who do not fit the ‘look’ that advertising has decreed applicable to their sexuality, and from the projected perspective of HIV positive gay men who face the reality of the daily decay of their bodies.”19

Other artists, such as David McDiarmid in his celebrated series of safe sex posters for the AIDS Council of New South Wales (below)) critique the body as site for libidinal and deviant pleasures for both positive and negative gay men as long as this is always undertaken safely. In the example from the series “Some of Us Get Out of It, Some of Us Don’t. All of Us Fuck With a Condom, Every Time,” 1992, we see a brightly coloured body, both positive and negative, filled with parties, drugs and alcohol, spreading the arse cheeks to make the arsehole the site of gay male desire. Note however, that the body still has huge arms, strong legs, and a massive back redolent of the desire of gay men for the muscular mesomorphic body image.

Lex Middleton (Australian)

Gay Beauty Myth

1992

Gelatin silver photographs

David McDiarmid (Australian, 1952-1995)

Some of Us Get Out of It, Some of Us Don’t. All of Us Fuck With a Condom, Every Time!

1992

Colour offset print on paper

67.1 x 44.5cm

AIDS Council of New South Wales / McDiarmid, David (designer). Some of Us Get Out of It, Some of Us Don’t. All of Us Fuck With a Condom, Every Time! 1992, in Gott, Ted (ed.,). Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS. Melbourne: Thames and Hudson/NGA, 1994, p. 154.

Brenton Heath-Kerr (Australian, 1962-1995)

Homosapien

1994

Laminated photomechanical reproductions and cloth

Heath-Kerr, Brenton. “Homosapien,” 1994, in Gott, Ted (ed.,). Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS. Melbourne: Thames and Hudson/NGA, 1994, p. 75.

More revealing (literally) was the work and performance art of Brenton Heath-Kerr. Growing out of his involvement in the dance party scene in Sydney, Australia in 1991, Heath-Kerr’s combination of costume and photography made his creations come to life, and he sought to critique the narcissistic elements of this gay dance culture, such as the Mardi Gras and Sleaze Ball parties. Later work included the figure Homosapiens (1994, above) which observes the workings of the body laid bare by the ravages of HIV/AIDS and comments on the politics of governments who control funding for drugs to treat those who are infected.

Californian photographer Albert J. Winn, in his series My Life until Now (1993, below) does not seek to elicit sympathy for his incurable disease, but positions his having the disease as only a small part of his overall personality and life. Other photographs in the series feature pictures of his lover, his home, old family photographs, and texts reflecting on his childhood, sexuality, and religion. As Albert J. Winn comments,

“The pictures from My Life Until Now are a progression of thinking about identity. Now I am a gay man, a gay man with AIDS, a Jew, a lover, a person who has books on the shelf, etc., not just another naked gay man with another naked gay man, and I tried to load the photograph(s) with information. I feel I am determining my identity by making the choice to show all this stuff.”20

Personally I believe that integrating your sexuality into your overall identity is the last, most important part of ‘coming out’ as a gay man, and this phenomenon is what Albert J. Winn, in his own way, is commenting on.

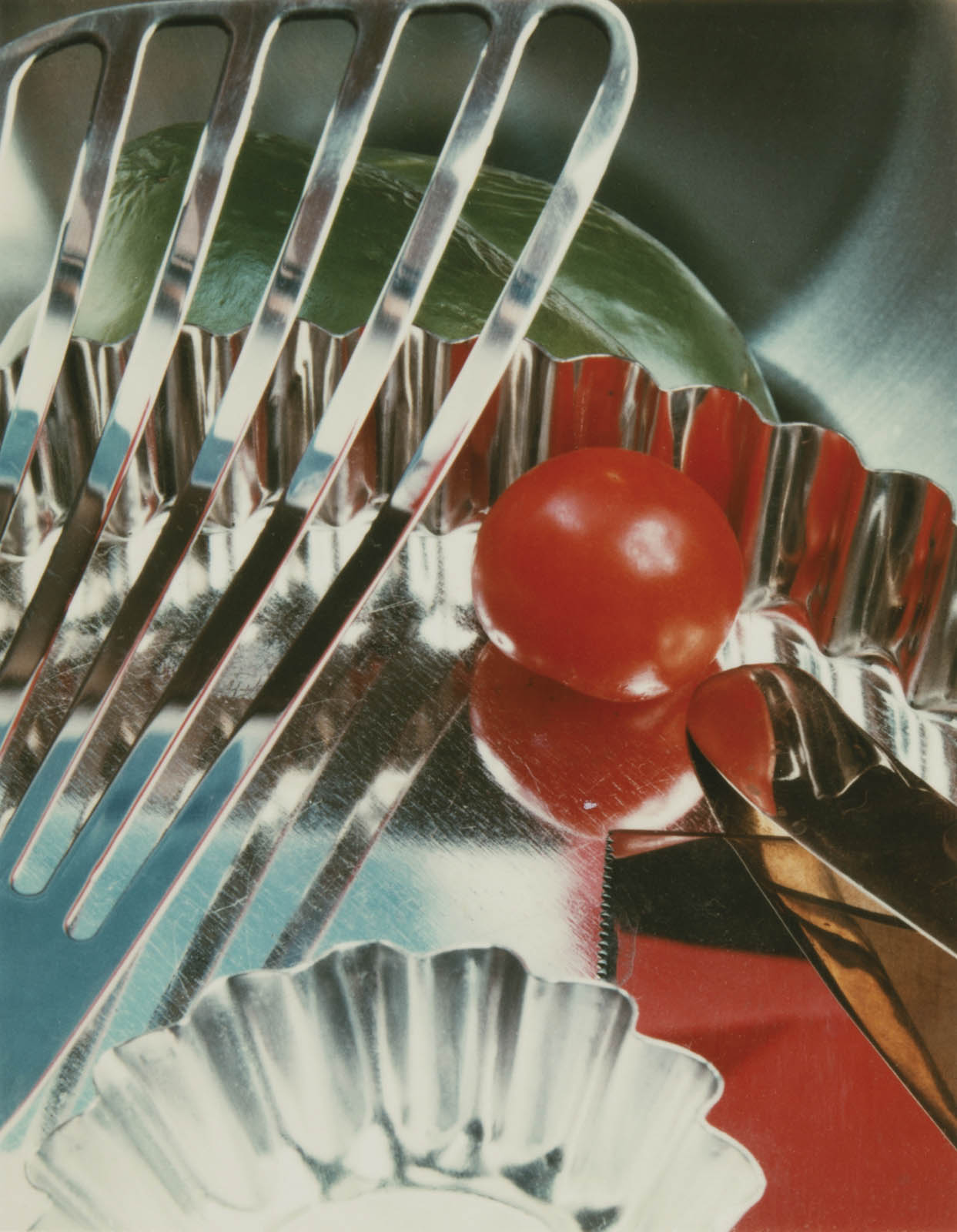

One of my favourite artists, now dead, who just happened to be gay and critiqued the social landscape was named David Wojnarowicz. Using an eclectic mix of black and white and colour photography (mainly 35mm), drawing, painting, collage, documenting of performances and sculpture, Wojnarowicz created a commentary on his world, the injustices, the sex, the politics, the brutality, the environments, and the people who inhabited them to name just a little of his subject matter. The Untitled 1988-1989 image from the Sex Series (below) is not a collage but a photomontage, two colour slides reverse printed onto black and white paper to make the negative image. Images from the series feature text, babies, all manner of different sexual persuasions, tornadoes, trains, ships, war images, and cells. Wojnarowicz himself states that,

“By mixing variation of sexual expressions there is an attempt to dismantle the structures formed by category; all are affected by laws and policies. The spherical structures embedded in the series are about examination and or surveillance. Looking through a microscope or looking through a telescope or the monitoring that takes place in looking through the lens of a set of binoculars. Its all about oppression and suppression.”

Oppression and suppression are the continuing themes in Wojnarowicz’s 1989 image, Bad Moon Rising (below). Here the wounded body of St. Sebastian, a recurring figure in gay iconography, has been impaled not just by arrows but by a tree, the mythological ‘tree of life’ growing up/down, from/into the ‘earth’ of money, the politics of consumerism and the illness of consumption. Again, in the small vignettes we observe the home, the sex, time, cells and their surveillance.

Albert J Winn (American, 1947-2014)

Drug Related Skin Rashes

1993

Silver gelatin photograph

Winn, Albert J. Drug Related Skin Rashes, from the series My Life Until Now, 1993, in Gott, Ted (ed.,). Don’t Leave Me This Way: Art in the Age of AIDS. Melbourne: Thames and Hudson/NGA, 1994, p. 224.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1989

From the Sex Series

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1989

From the Sex Series

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Bad Moon Rising

1989

Black and white photographs, acrylic, string, and collage on Masonite

Wojnarowicz, David. Bad Moon Rising, 1989, in Harris, Melissa. Brushfires in the Social Landscape. New York: Aperture Publications, 1994, p. 39.

And so it goes…

Meanwhile in Australia, the burgeoning cult of body worship was being fuelled by the more traditional homo-erotic photographs from America. This iconography was assimilated by local commercial photographers. They played with the traditions of surf, sand, sun and sea for which Australia is renowned and Dennis Maloney, in particular, concentrated his attention on the surf lifesavers that patrolled the beach during surf carnivals. He photographed the guys with their well built tanned bodies, good looks, swimming costumes pulled up between buttocks, and let the homosexual market for such images do the rest. He also photographed what I would classify as soft-core porn images such as the Untitled 1990 image from the series Sons of Beaches (below), the idyllic man in his reverie, wet bathing costume moulded to the curve of his buttocks, legs spread invitingly in a suggestive homo-erotic sexual position.

This trend of using images of the muscular, smooth male body for both commercial purposes and as the ‘ideal’ of what a gay man should look like continues unabated to this day. Pick up any local gay newspaper or magazine and they are full of adverts for chat lines or escorts that feature this body type. The news photographs from around the clubs also feature nearly naked well built men with their buffed torsos.

Most images on the Internet also feature this particular body type (below), whether they belong to commercial sites or as the images that are chosen, desired and lusted after in the galleries of private home pages. The most alternative photographs of the male body I have found on the Internet occur when they are the personal photographs of their authors, when they picture themselves (below). These images exhibit a massive variety in the shape, size, hirsuteness and colour of gay men, most of whom don’t come anywhere near to the supposed ‘ideal’. And what of the future for the male body? Perhaps you would like to read the Future Press chapter in the CD ROM to get a few ideas.

Dr Marcus Bunyan 2001

Denis Maloney (Australian)

Untitled

c. 1990

From the series Sons of Beaches

Colour photograph

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

1998

Image from a commercial Internet web page

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

1998

Image from a commercial Internet web page

Footnotes

1/ Anonymous (French). “Male Nude Study.” Daguerreotype, c. 1843, in Ewing, William. The Body. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994, p. 65. Courtesy: Stefan Richter, Reutlingen, Germany.