Exhibition dates: 30th October, 2025 – 22nd February, 2026

Curators: Walter Moser, head of the department of photography at the Albertina, with assistant curator Nina Eisterer

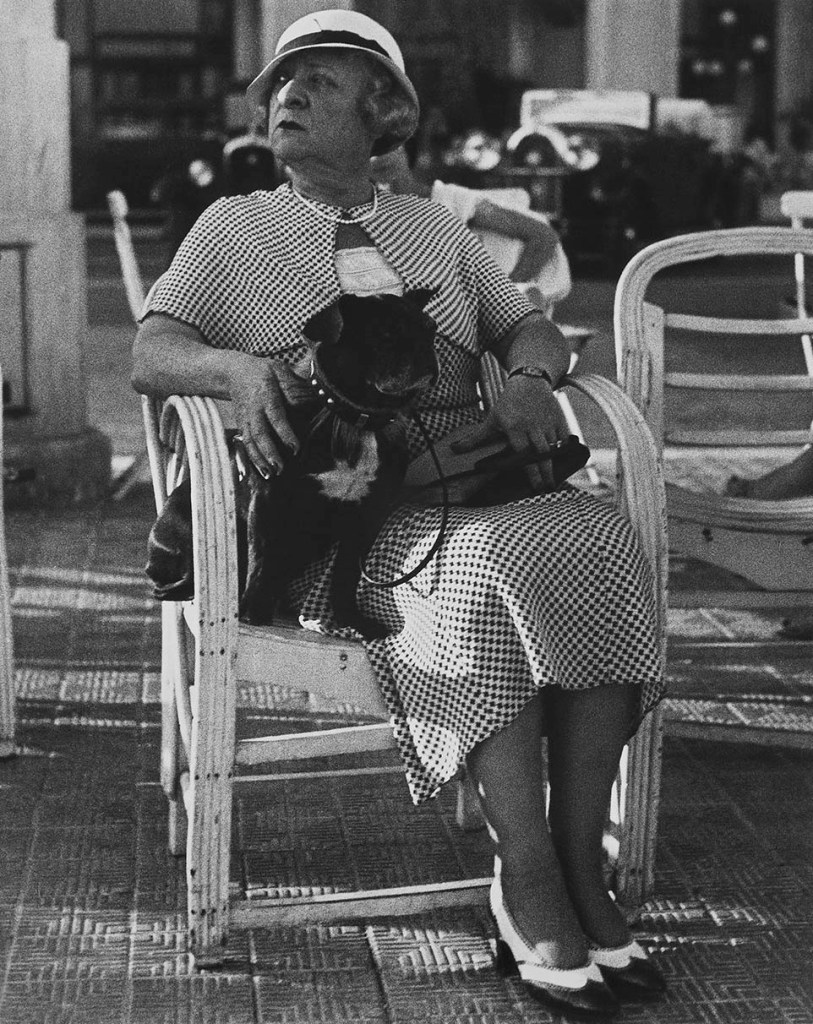

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Promenade des Anglais, Nice

1934

Gelatin silver print

50.7 x 40.4cm

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy of baudoin lebon and Avi Keitelman

From the gut

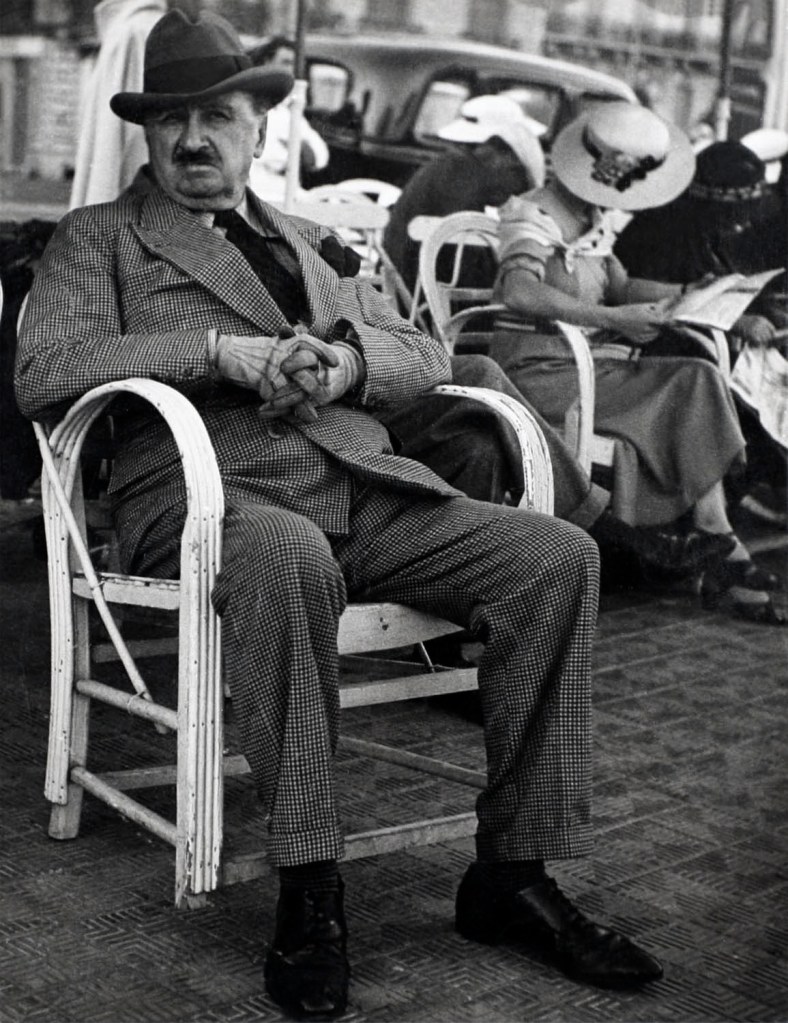

All the haughtiness of the upper-upper, lower-upper, socialites and high society in Promenade des Anglais, Nice (1934, below) versus all the “colour” and characters of Sammy’s Bar in New York, salt of the earth, dead beat party animals (1940-1944, below).

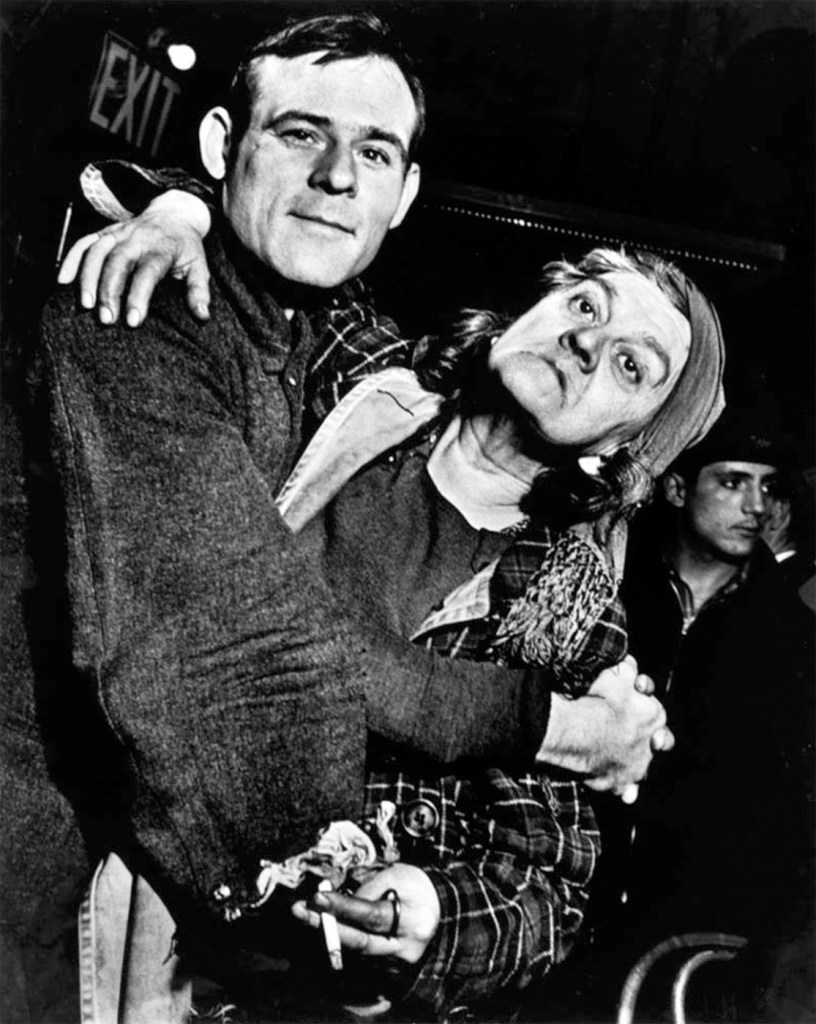

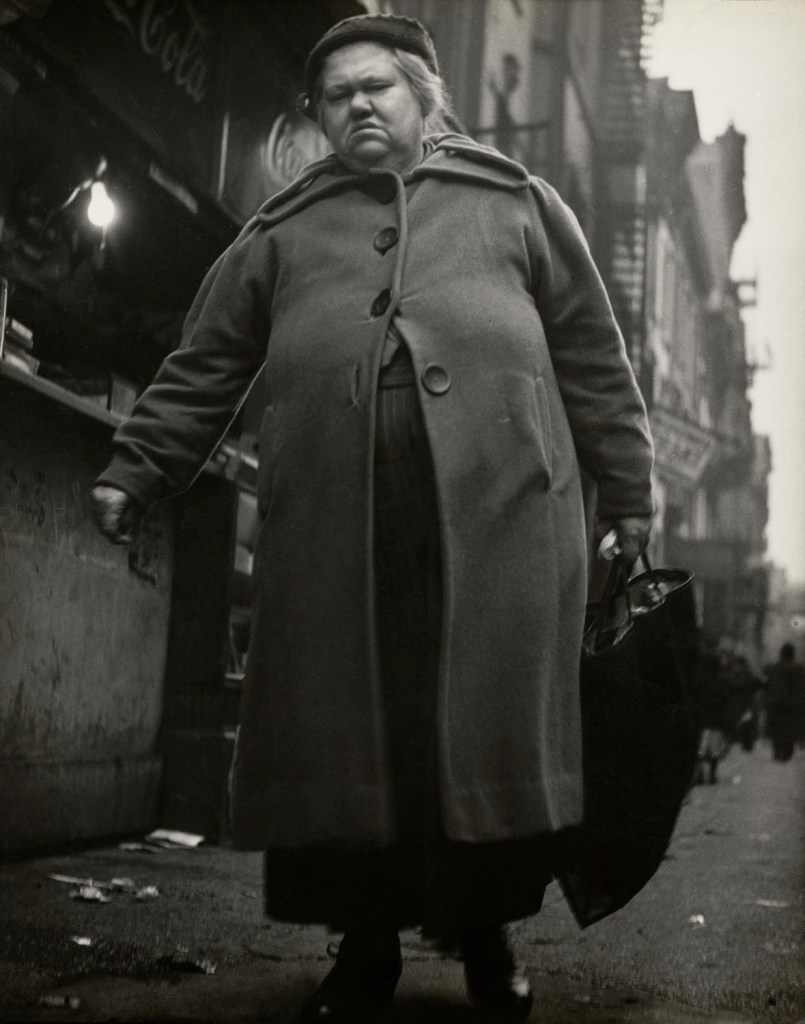

All the obsequious opulence of the women in Fashion Show, Hotel Pierre, New York (1940-1946, below) versus all the low angle, unbuttoned bulk of a New York bag lady in Lower East Side, New York (1940-1947, below)

Model sure doesn’t pull any punches and, perchance, you know which side of the fence she sits.

Combining social realism and emotional expression Model’s street-life scenes and portraits are shot with a razor sharp mind and eye, honed with emotional insight and social conviction, promoting “a fierce attack on the bourgeoisie of the time.” These images are shot from the gut, felt in the gut! Oooof! Kapow!

This philosophical, libertarian vision is grounded in the everydayness of working people, not in men “who sit at desks as large as thrones, who gather in solemn hemicycles, in splendid and severe seats…”

Her Promenade des Anglais photographs are incisive, cutting to the marrow, evidencing a piercing, core-level truth about the nature of power, money, humility, humanity. Knowing exactly the story she wanted to tell, Model cropped her negatives in the darkroom to get the desired, constructed photographs of the elite, this promenade of the privileged. That she passed on her wisdom to Diane Arbus is only to our benefit.

Model’s photographs in this series are more biting, satirical and oblique than those of Arbus. Direct in one way (in the placement of the camera in front of the subject) but oblique in another … in the asymmetrical placement of the figures within the picture plane, in the sly acknowledgement (or not) and resentment of the camera by the subject. Conversely, her photographs of people in nightclubs, jazz performers and the socially disadvantaged are humanist photographs of the highest order, unorthodox musical compositions that sing with light, movement, and life much more so than the square, formal attributes of the Arbus.

God bless Lisette Model for her glorious irreverence and musical lyricism.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to The Albertina Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“As long as man exploits man, as long as humanity is divided into masters and servants, there will be neither normality nor peace. The reason for all the evil of our time is here. Do you see these? Severe, double-breasted, elegant men who get on and off airplanes, who run in powerful cars, who sit at desks as large as thrones, who gather in solemn hemicycles, in splendid and severe seats: these men with the faces of dogs or of saints, of hyenas or eagles, these are the masters.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini

Model’s libertarian philosophy is not easy to classify… it is often stuck in the approximation of street photography… but photography, when it is great, is one! and one only!… Genres only serve to sink it into the language of commerce! The lopsided shots, the deep blacks, the stellar whites… beaded with emotional uniqueness… see the human being as an end and never as a means… they invite us to think that justice is inseparable from beauty, it is a way of doing things well, like a chair-setter, a coalman, or a bricklayer… to flee from the arrogance, imitation, and contempt that accompany social codifications… what is beautiful is naturally right… because photography is not just a linguistic quest, but precisely as a linguistic quest, it is a philosophical vision… that respects no barriers or emulates the gods… it is an original, archetypal desire, that takes precedence over everything and carries it as the absolute value of beauty and justice!

Pino Bertelli. “Lisette Model. Sulla fotografia del disinganno,” on the Phocus Magazine website Nd [Online] Cited 02/02/2026. Translated from the Italian by Google Translate. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Promenade des Anglais, Nice

1934

Gelatin silver print

43.2 x 35.4cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris /

Keitelman, Brussels

“Visiting her mother in Nice in 1934 Model took her camera out on the Promenade des Anglais and made a series of portraits which to this day are among her most widely reproduced and widely exhibited images. With them Model declared her trademark style: Close-up, biting, satirical – almost like photographic political cartoons. In a nice bit of art history sleuthing, Thomas discovered that this series was published in the communist periodical Regards, a publication led by Ehrenburg, Gide, Gorky and Malreaux in 1935. Model, she says, never denied having published her work in Europe, but neither did she ever precisely acknowledge having done so… Thomas also relates Model’s style to the style of images published in Regards and what was being shown in small galleries – that approach, almost mocking, surely exposing, with the photographer or artist clearly separate/different if not superior from the subject – was in the air. Model perfected it, but she didn’t invent it.”

Elsa Dorfman. “Ann Thomas on Lisette Model,” on the AMERICANSUBURB X: THEORY website, June 14, 2010 [Online] Cited 03/02/2026. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Promenade des Anglais, Nice

1937

Gelatin silver print

50.7 x 40.4cm

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

© Estate of Lisette Model

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Promenade des Anglais, Nice

1937

Gelatin silver print

50.7 x 40.4cm

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

© Estate of Lisette Model

Lisette Model (1901-1983), born into a Viennese Jewish family, is regarded as one of the 20th century’s most influential photographers. This ALBERTINA exhibition presents a broad retrospective covering her most important groups of works created between 1933 and 1959. Alongside iconic photographs such as Coney Island Bather and Café Metropole, the selection will also include seldom-seen works.

Model, following her emigration to New York in 1938, quickly rose to prominence with her pictures for magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar showing facets of urban life: the poverty of the Lower East Side, the upper class at their leisure pursuits, and night life at bars and jazz clubs. Model went on to become an influential teacher during the McCarthy Era. The exhibition features the first-ever public presentation of the original draft of her 1979 monograph, a classic of photo book history.

Text from The Albertina Museum website

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

First Reflection, New York

1939-1940, printed 1976-1981

Gelatin silver print

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

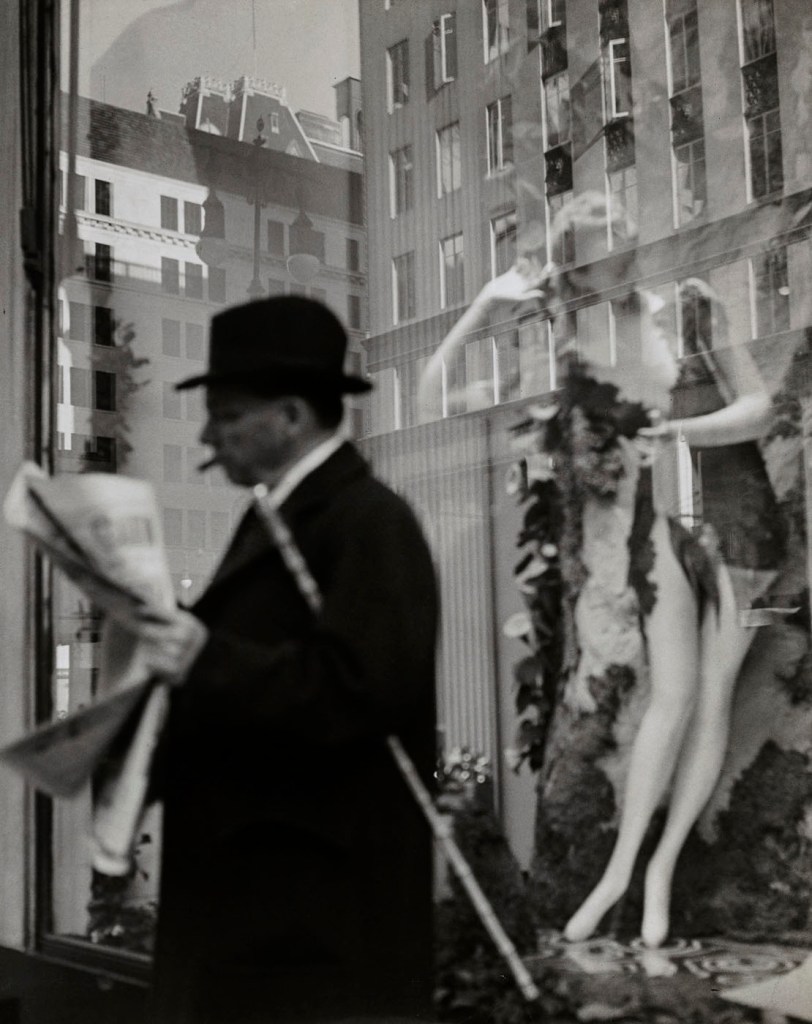

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Window, Bonwit Teller, New York

1939-1940, printed 1976-1981

Gelatin silver print

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Reflections, New York

1939-1945

Gelatin silver print

26.5 x 33.4cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris / Keitelman, Brussels

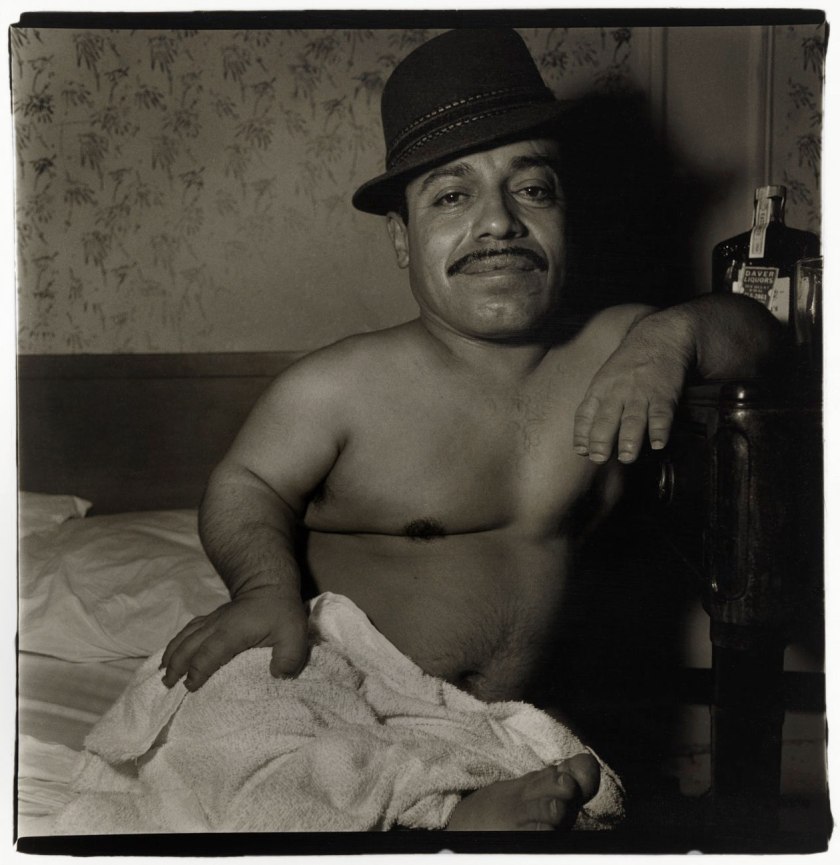

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Singer, Sammy’s Bar, New York

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of Lisette Model

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Couple Dancing

1940

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of Lisette Model

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Sammy’s Bar, New York

1940-1944

Gelatin silver print

37.8 x 49cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna – Permanent Loan Austrian Ludwig Foundation for Arts and Science

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris / Keitelman, Brussels

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Sammy’s

1940-1944

Gelatin silver print

© Estate of Lisette Model

Born into a Viennese family with Jewish roots, Lisette Model (1901-1983) is considered one of the most internationally influential female photographers. The exhibition at the ALBERTINA Museum is the most comprehensive presentation of the artist in Austria to date and brings together her most important groups of works from 1933 to 1959. In addition to iconic photographs such as Coney Island Bather and Singer at the Metropole Café, the exhibition also includes lesser-known works that have never been shown before.

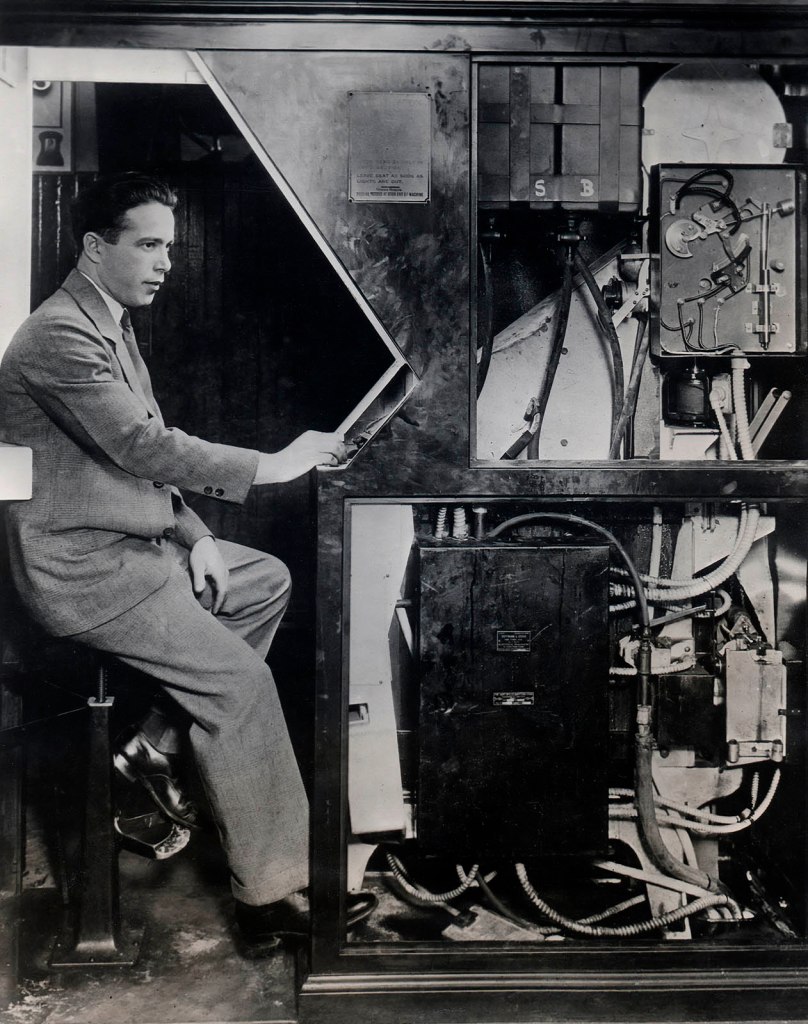

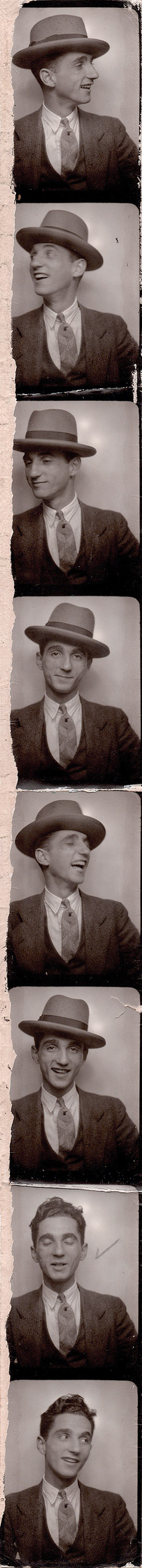

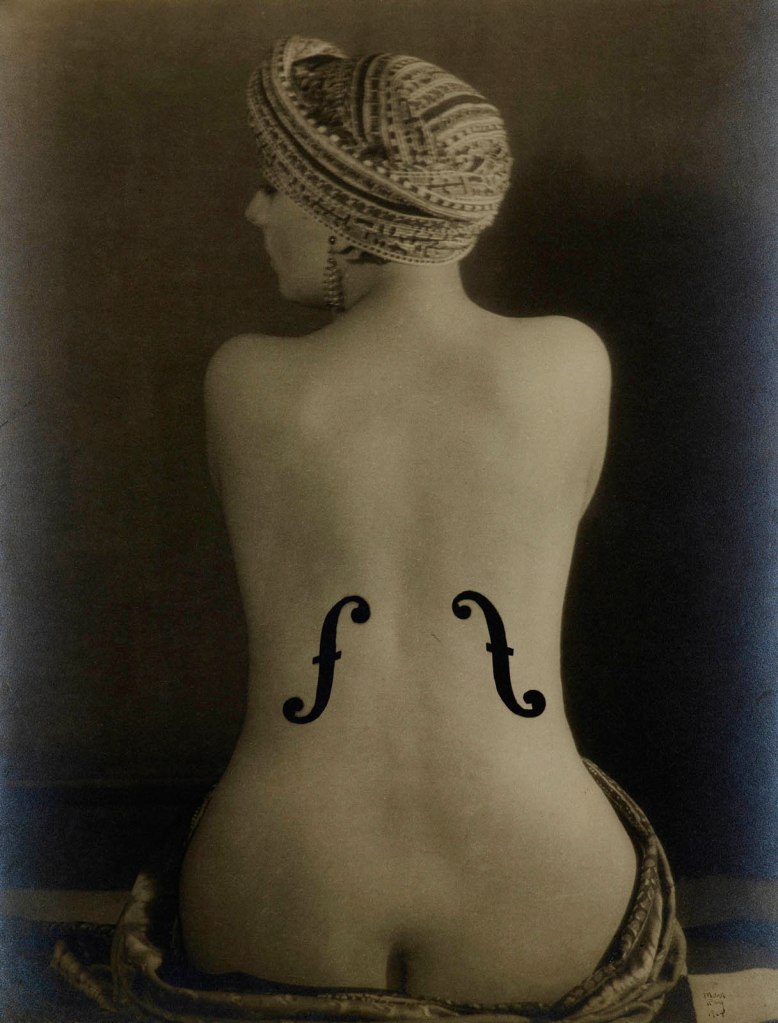

While Lisette Model initially pursued a musical education, it was only in France, where she lived from the mid-1920s, that she found her way to photography: in 1934, the self-taught photographer took her revealing series of portraits of rich idlers in Nice, which caused a sensation as a biting social critique in the heated political climate of the time. After Model emigrated to New York in 1938, she quickly made a name for herself in the vibrant art scene as a freelance photographer for style-setting magazines such as Harper’s Bazaar. She photographed the diverse and contradictory facets of urban life: Model showed the poor population of the Lower East Side district in unsparing shots, the upper class at their pleasures in confrontational portraits and the vibrant nightlife in bars and jazz clubs in dynamic series. In the late 1940s and 1950s, she created extensive groups of works outside New York.

The photos of the west coast of the USA or Venezuela are characterised by a melancholy and gloomy mood without Model losing sight of social conditions. Due to political reprisals during the McCarthy era, Model began her second, enormously influential career as a teacher. After decades of effort, the publishing house Aperture published her first monograph in 1979. The exhibition Lisette Model presents the original design of this publication, which is now a classic among photo books, for the first time.

Lisette Model

Lisette Model (1901-1983) brought about a sudden change in photography with her spectacularly direct pictures. Her immediate, humorous, frequently confrontational, yet sometimes also empathetic style of representation revolutionised traditional documentary photography. Her pictures of street-life scenes and portraits combine social realism and emotional expression: “Shoot from the gut!” was her famous credo. This retrospective brings together Model’s most important groups of works from her nearly thirty-year career, from 1933 to 1959, including works that have never been on view before.

Lisette Model was born as Elise Amelie Felicie Stern (Seybert) into an upper class Viennese family with Jewish roots in 1901. She initially pursued a musical education and from 1919 to 1921 attended courses taught by composer Arnold Schönberg at the progressive Schwarzwald School, which had been founded by Eugenie Schwarzwald. Her contact with Schönberg proved formative for Model’s artistic work. After her father’s death, Lisette Model, together with her mother and sister, moved to France in 1926, where she discovered photography. In 1934 she shot her first extensive portrait series of wealthy idlers in Nice, which caused a furor for betraying social criticism in the heated political climate of the time.

Having emigrated to New York in 1938, Model quickly made a name for herself in the art scene as a freelance photographer for such influential magazines as Harper’s Bazaar. She photographed the contrasts of urban life: in unsparing images, Model presented the impoverished population of the Lower East Side; in scathing portraits, she depicted the upper classes indulging in their pleasures; and in a number of dynamic series, she captured the pulsating nightlife of the metropolis. In the late 1940s and 1950s she created her first series of works outside New York. Due to political reprisals during the McCarthy era, Model’s artistic work stagnated. She embarked on an influential career as a teacher, shaping an entire generation of photographers, including Larry Fink, Diane Arbus, and others.

France

In 1926, Lisette Model moved to France, where she continued her vocal training, which she was forced to discontinue abruptly due to voice problems. In 1933 she turned to photography instead. The threatening political situation in Europe made it necessary for her to learn a profession, and photography offered itself as a modern field of activity especially for women. Model’s sister Olga, a trained photographer, and the artist Rogi André provided important inspiration, including the momentous advice to photograph only what aroused her passionate interest.

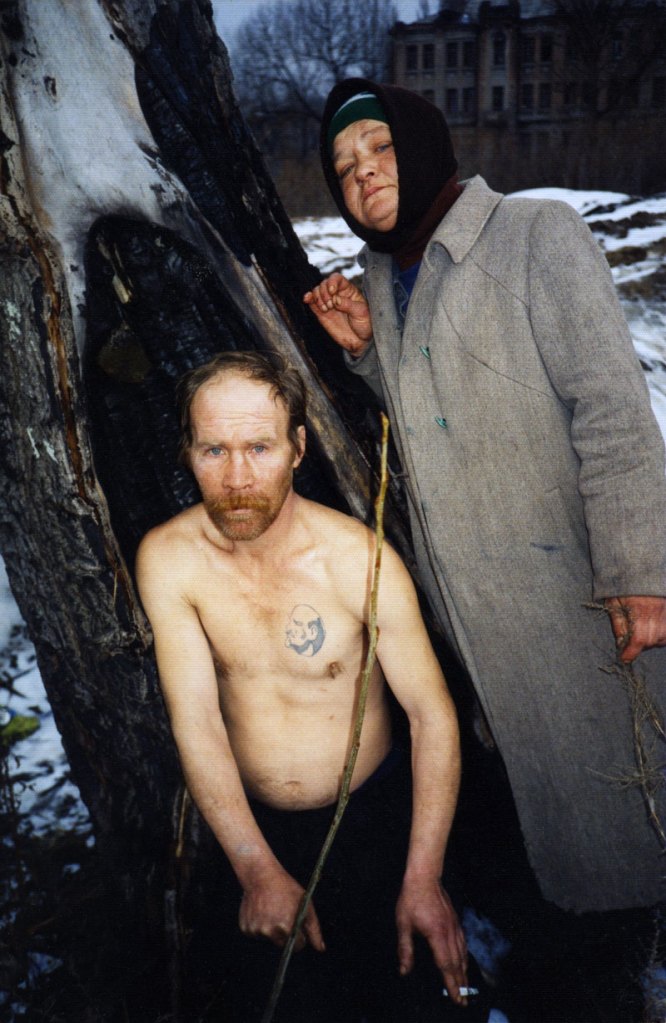

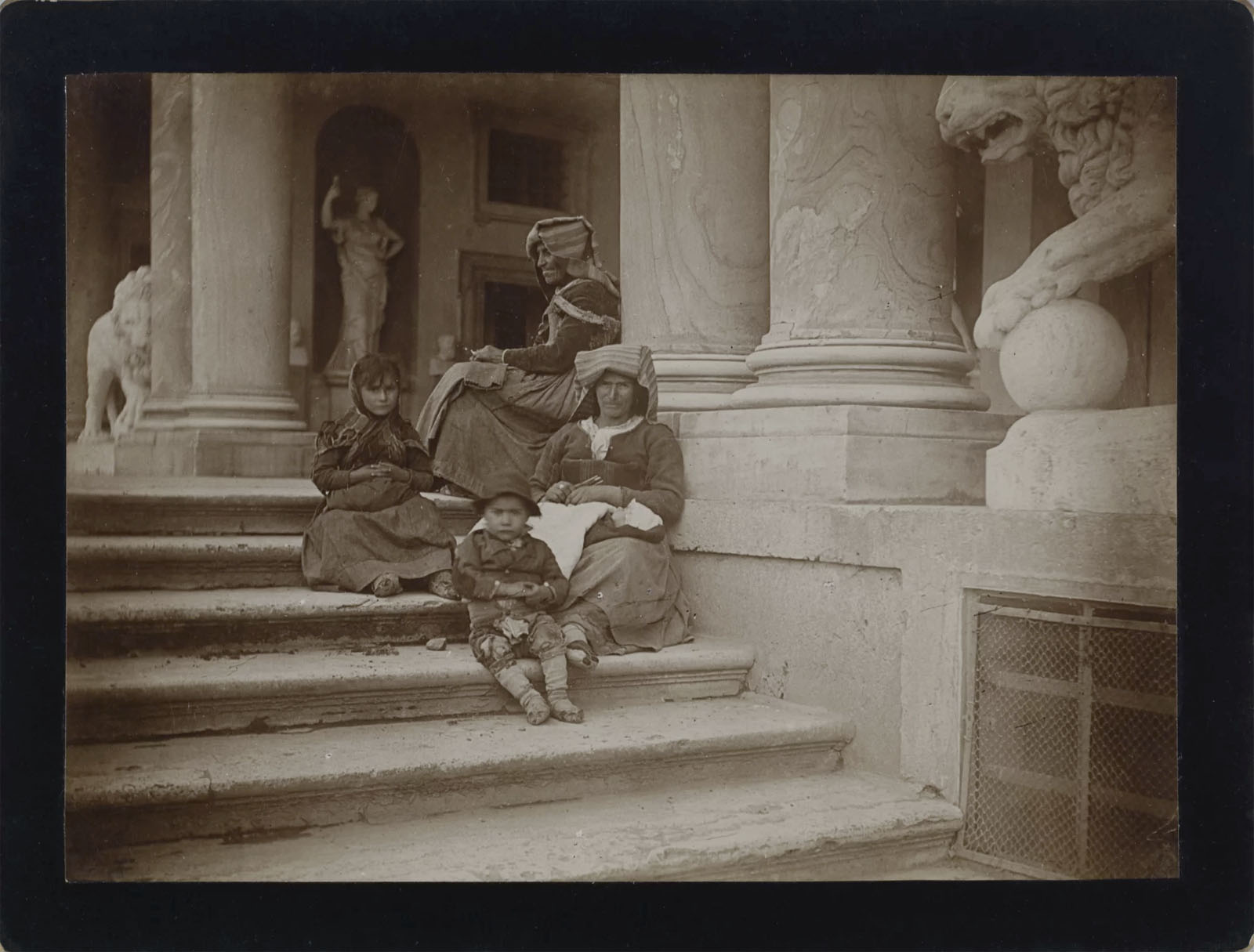

The economic crisis and the rise of fascism went hand in hand with a debate among committed left-wing artists about documentary photography. The central question was to what extent photography could expose social injustices and serve as a weapon in social conflicts. It is unclear how closely Model followed these debates; in later years, she remained persistently silent on the subject. Her early photographs from Paris clearly reveal a socially critical approach. Going about her work with distinct directness, she photographed sleeping homeless people and blind beggars, whom she characterised as victims of social circumstances through their bent bodies.

In July 1934, Lisette Model used a Rolleiflex to photograph a series of portraits of wealthy idlers on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. It was synonymous with glamour and elite tourism and a popular motif at the time. Yet Model portrayed her subjects as caricatures through their facial expressions, postures, and gestures. The narrow cropping of the motifs suggests that the photographer was in close proximity to her subjects, who look condescendingly into the camera. In fact, however, Model achieved this effect in the darkroom, where she selected radically novel perspectives from the negatives.

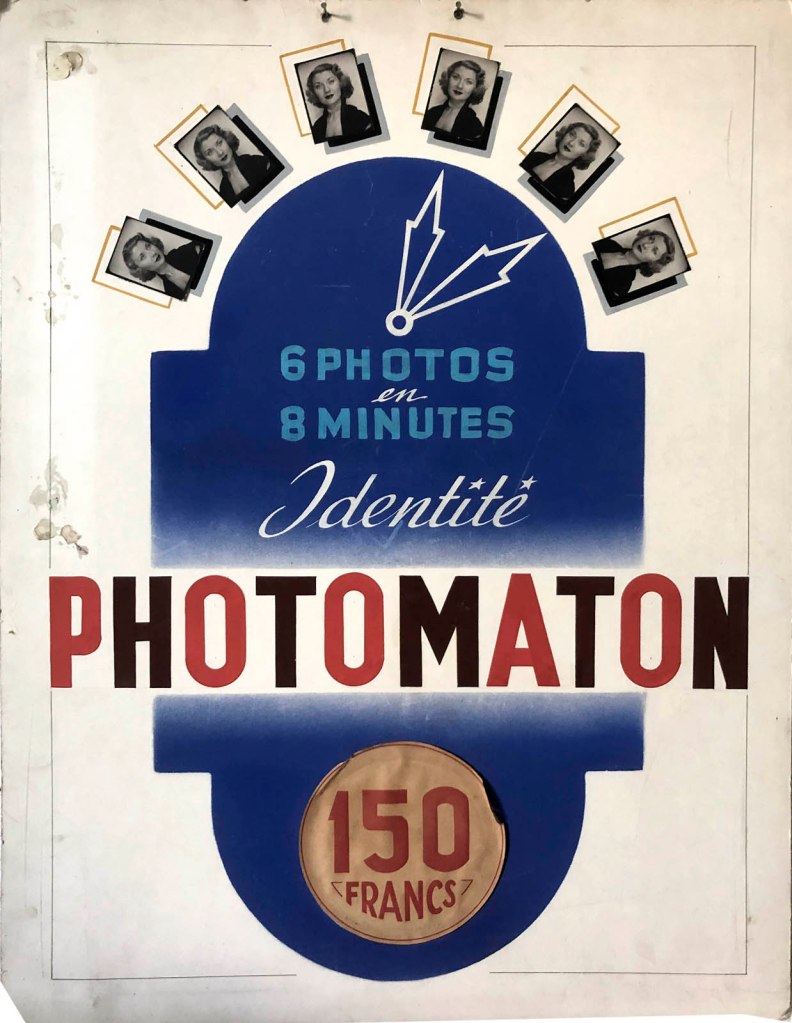

Regards

Although Lisette Model was only at the beginning of her career, the respected communist magazine Regards published her photographs from the series Promenade des Anglais in 1935. The layout of the article juxtaposed Model’s portraits with an image of a female worker with a fishing net. The accompanying text also embeds the photographs in the ideological rhetoric of class struggle: “The Promenade des Anglais is a zoological garden where the most abominable specimens of the human species lounge in white armchairs. Their faces betray boredom, condescension, impertinent stupidity, and at times malice. These rich people, who spend most of their time dressing, adorning themselves, manicuring their nails, and applying makeup, fail to conceal the decadence and immeasurable emptiness of bourgeois thinking.”

Against the backdrop of the repressive climate of the McCarthy era in the 1950s, Lisette Model would later tone down the political content of her images from Nice. Instead, she emphasised the humour and her intuitive approach to portraiture in public spaces.

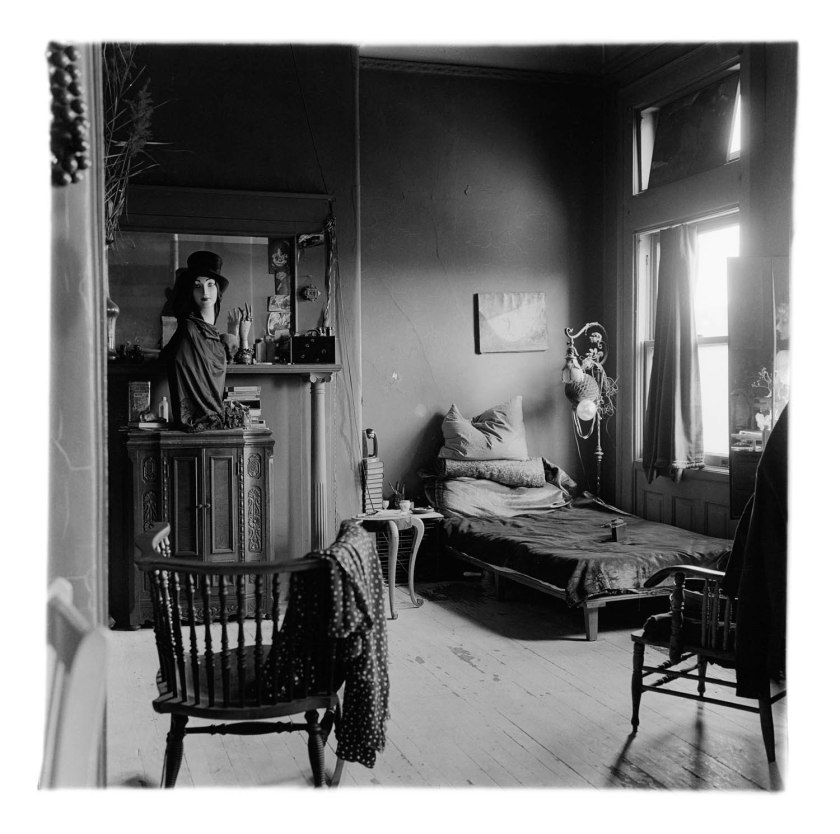

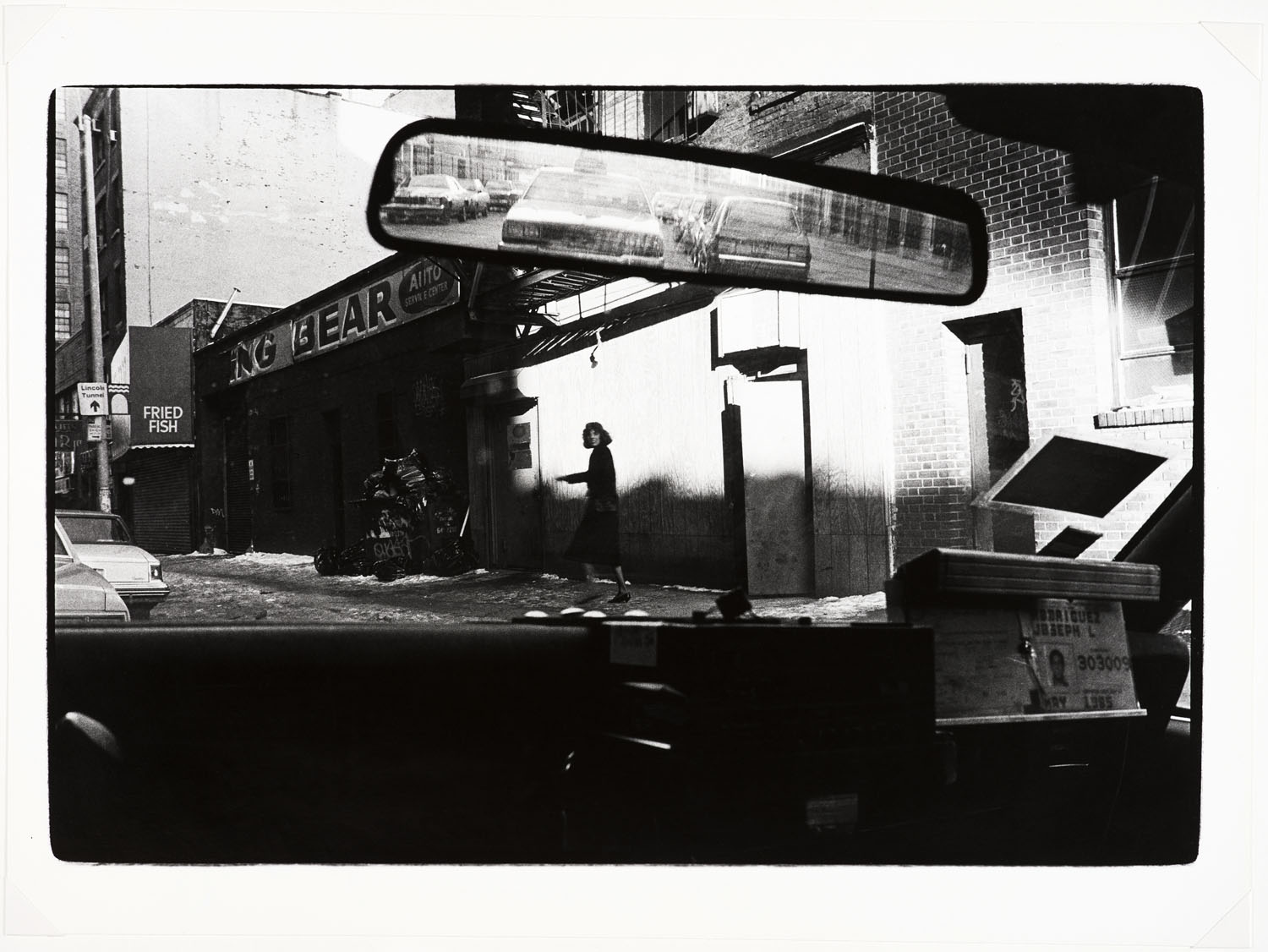

New York

In October 1938, Lisette Model emigrated to New York with her husband Evsa Model, a Jewish-Russian painter. Her first series shot there reveal her great fascination with the metropolis. The work Reflection, which makes use of reflections in shop windows, merges motifs and spaces to create an enigmatic collage. For the Running Legs photographs, Model did not point her camera upwards at the skyscrapers as usual, but looked at the feet of passersby at street level. Model experienced New York’s hectic and consumer-oriented culture as ambivalent: the dark shadows in the windows of the department stores seem threatening, and the dense crowds of legs have a claustrophobic effect. In portraits of people on Fifth Avenue and Wall Street photographed from below, Model highlights the arrogance of the pedestrians rushing by.

Shortly after her arrival in New York, Lisette Model attracted the attention of several key figures in the art and media world. Her contacts with Ralph Steiner, editor of the magazine PM’s Weekly, and Alexey Brodovitch, the legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar, proved momentous. In 1941, Steiner published Model’s biting photographs of the Promenade des Anglais in Nice under the provocative title “Why France Fell” as an explanation for the country’s defeat in World War II. Model’s first commission for Harper’s Bazaar took her to the popular leisure destination of Coney Island, where she shot her iconic photographs of a bather with an empathetic eye. As early as 1940, the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired one of Model’s pictures and continued to show her works in exhibitions in the following years.

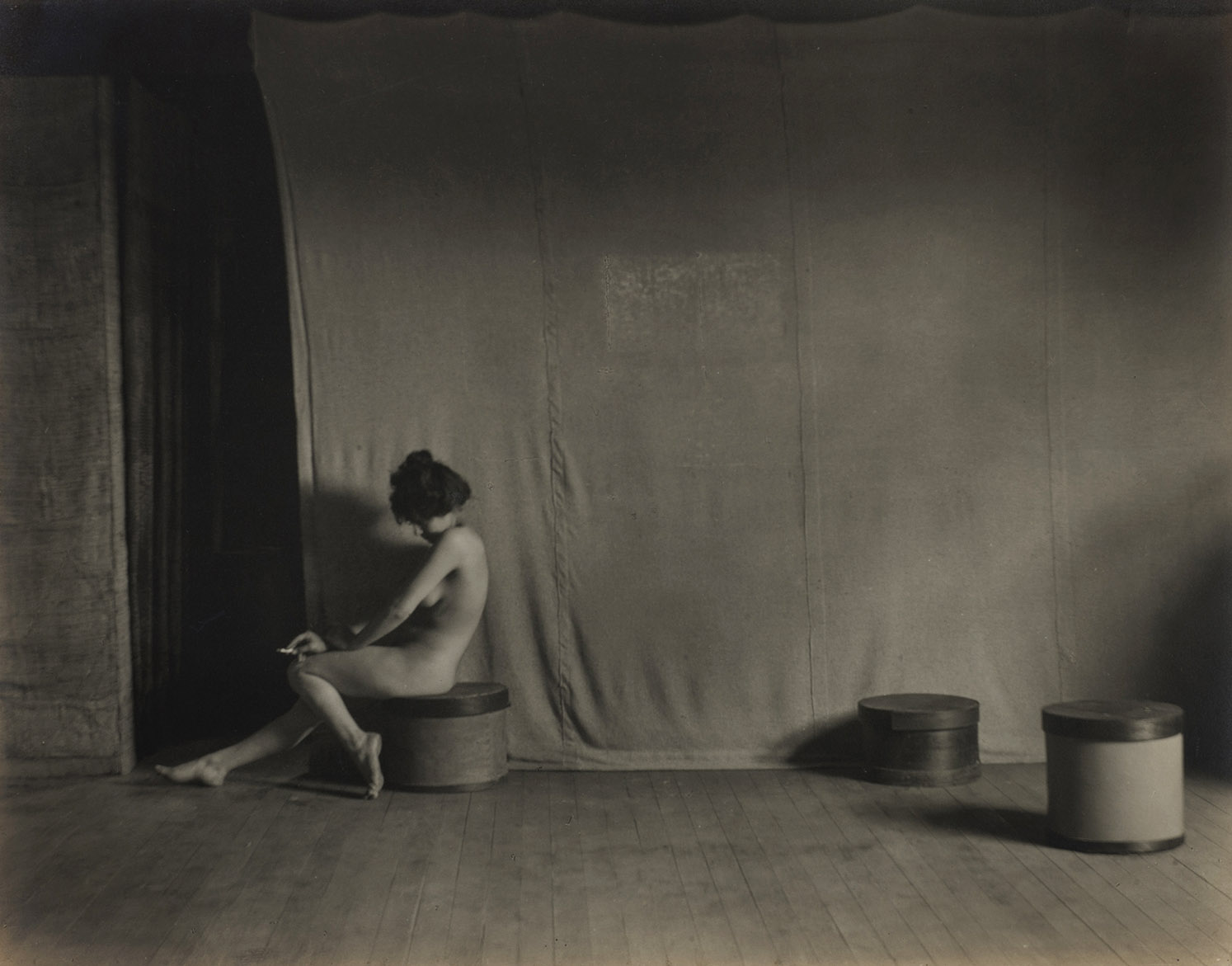

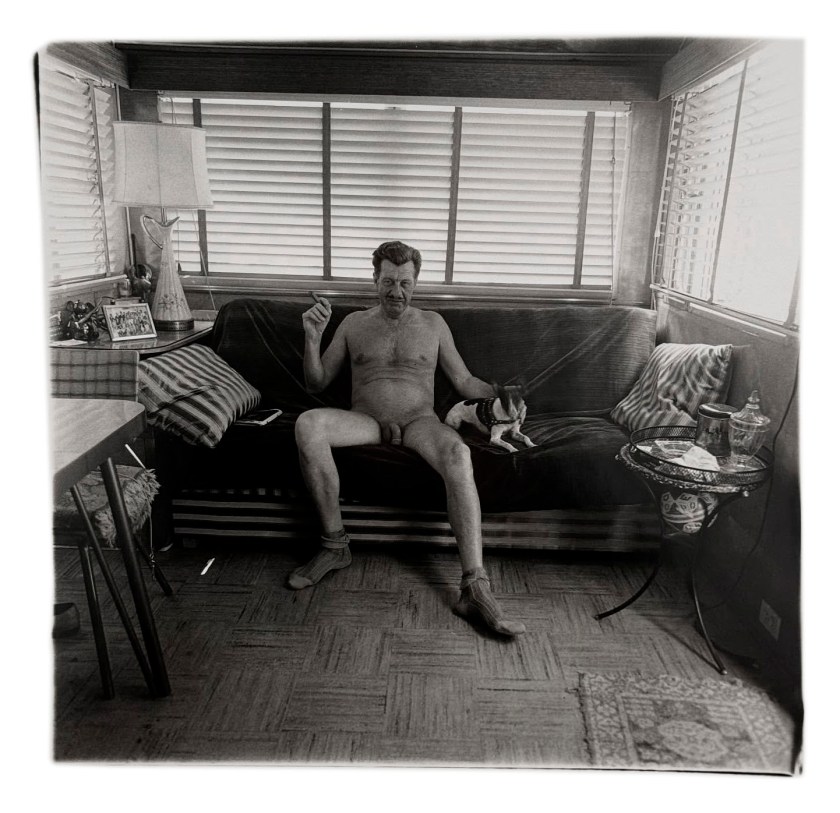

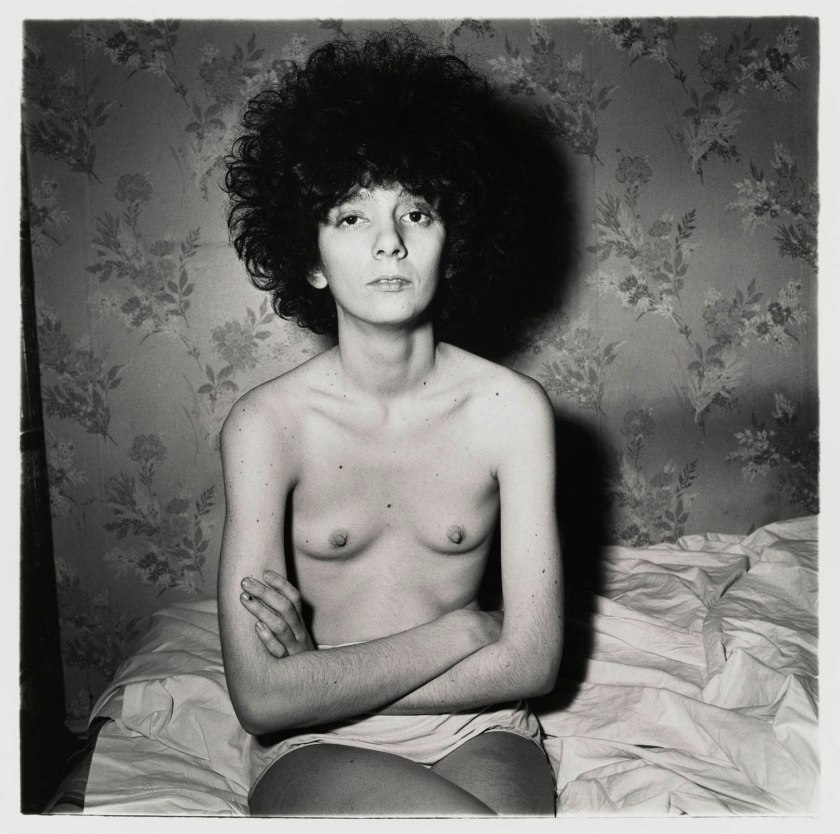

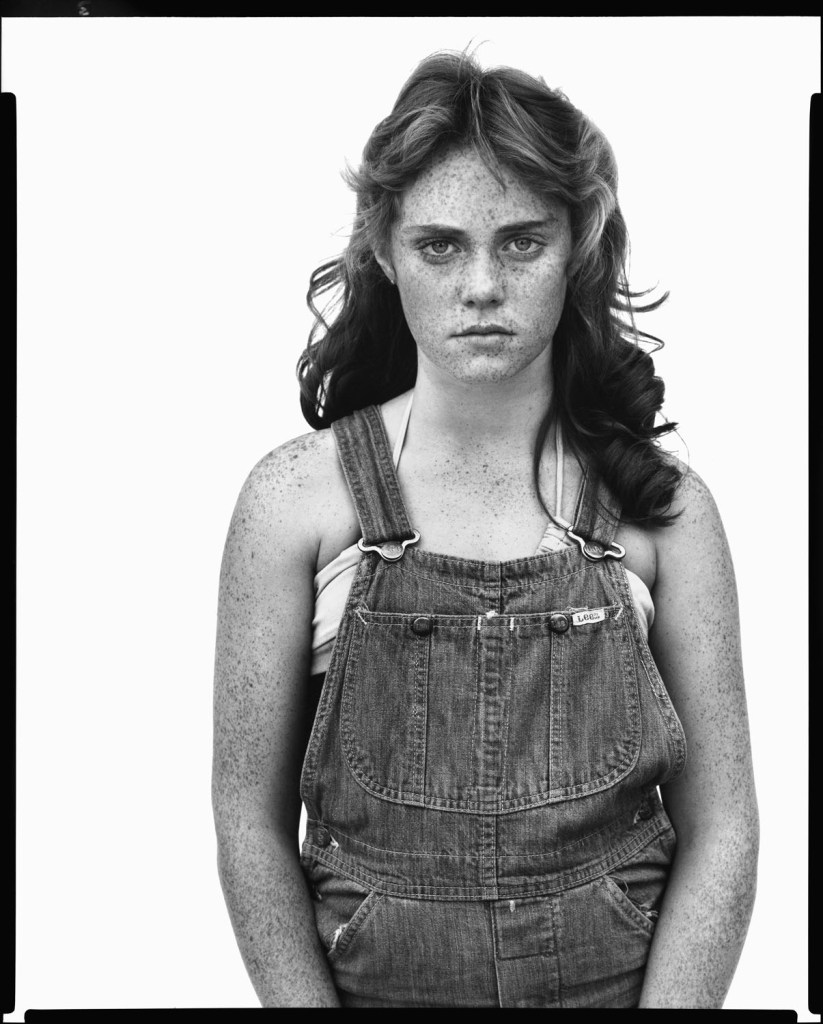

Lower East Side

In one of her most extensive groups of works, Lisette Model focuses on the residents of the Lower East Side. Model’s attention to physical peculiarities and extremes becomes particularly apparent in it. Retrospectively defined cropping detaches the people from their spatial surroundings and emphasises the sitters’ statuesque monumentality.

Lisette Model shared her interest in the socially disadvantaged with photographers from the New York Photo League, an influential left-wing political association dedicated to socially committed photography. Becoming a member, Model actively participated in Photo League events and exhibited on its premises. And yet she distanced herself from her photography being categorised as political or social documentary. She also rejected accusations of portraying her models overly sarcastically, arguing instead for a humanist point-of-view that focuses on the strength and personality of her subjects. Emotional expression and social realism are inextricably linked in these photographs: the expressive bodies clearly display the burden of tough living conditions.

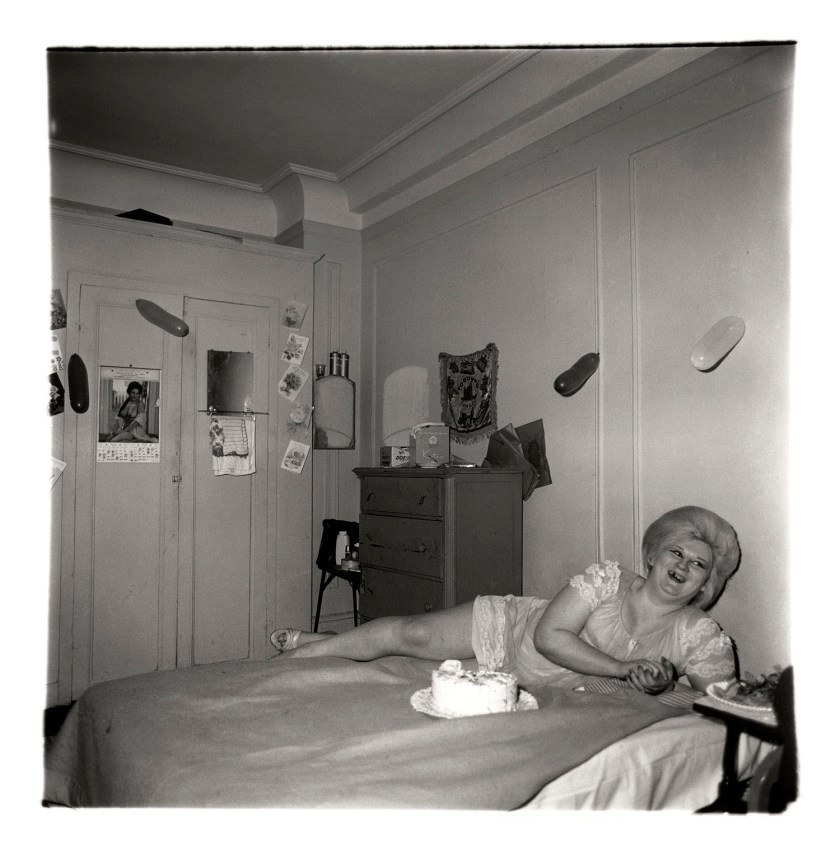

Entertainment

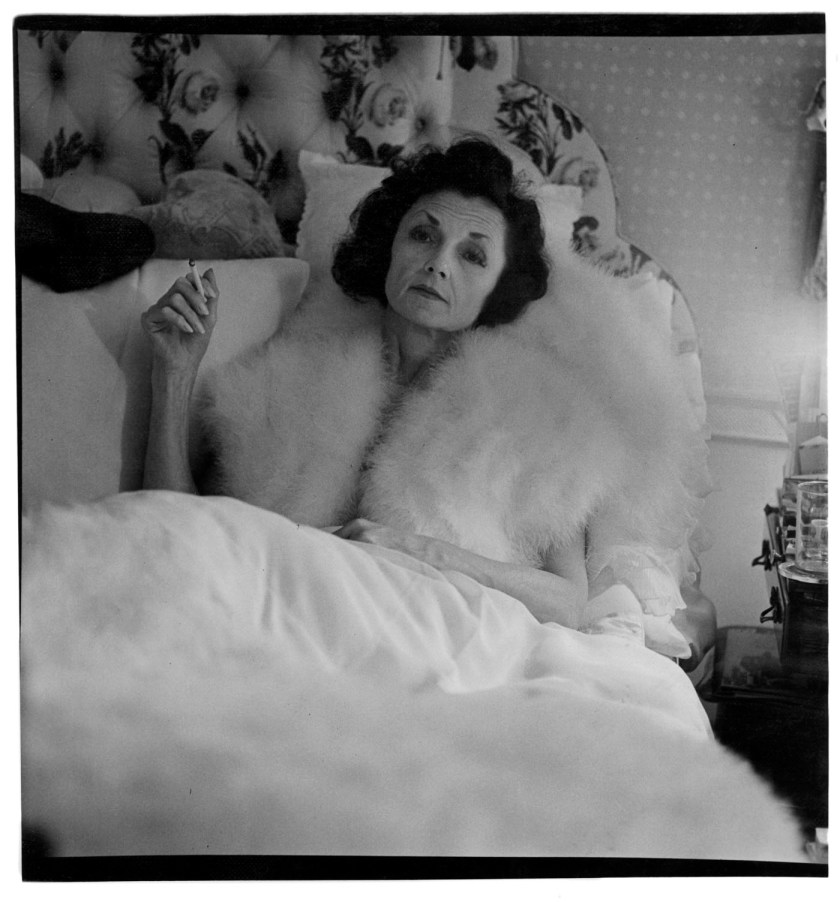

Similar to her photographs from France, Model also explored disparities in urban life in New York. The harsh images of the Lower East Side are juxtaposed with photographs of people indulging in leisure activities and amusing themselves at all kinds of shows. Model captured these scenes with a keen eye for human contradictions and bizarre moments: dressed-up ladies at a fashion show are just as much a part of this as participants in a dog show bearing a striking resemblance to their four-legged friends. Photographs taken in museums do not focus on the artworks intently viewed by visitors, but rather on the act of vision itself. With a few exceptions, the series Dog Show and Museum have only survived as negatives. They can now be presented here in digital form for the first time.

Nightlife

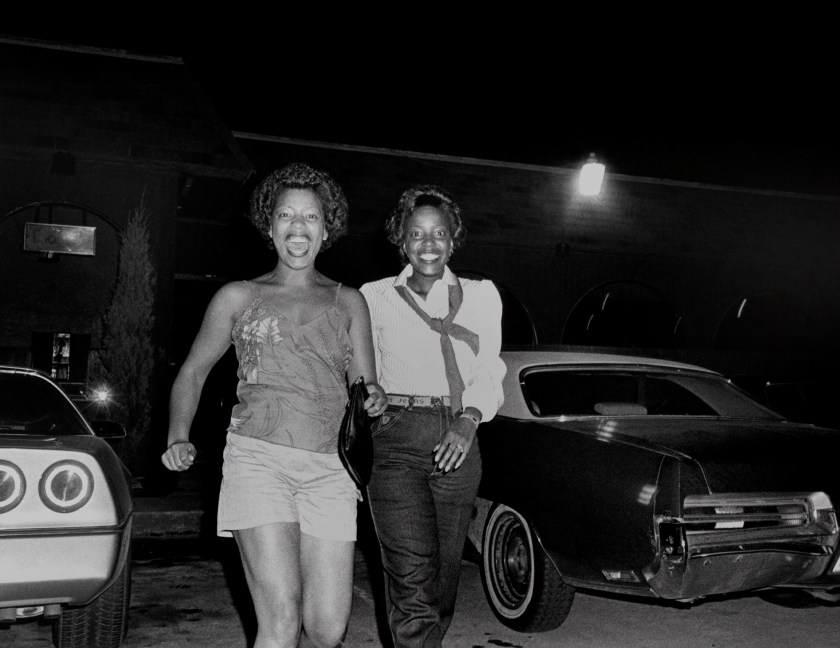

Lisette Model’s intuitive approach to photography reached its peak in her pictures of nightclubs. Using bright flashes, she snatched the celebrating guests and energetic performers from the darkness and in the subsequent post-editing of the images tilted the motifs to render the compositions more dynamic. The depiction of expressive gestures and people in moments of emotional tension recalls the body images of the early Viennese Expressionists, whom Model got to know through her contact with Arnold Schönberg. Model, who always vehemently denied the influence of other artists, acknowledged solely Schönberg’s impact on her work. His theory of the “emancipation of dissonance,” which expands on classical harmony, is echoed both in Model’s unorthodox compositions and in her caricatures.

The traumatic experience of exile left deep traces in Lisette Model’s work. Like the Lower East Side before, nightclubs were places populated by immigrants. They evoked a sense of social belonging and cultural familiarity in the artist.

West Coast

In 1946, Lisette Model accompanied her husband Evsa to San Francisco on an invitation from the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA). She quickly established connections with the lively photography scene on the US West Coast, where famous photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston were active. Model returned several times and in 1949 taught a course on documentary photography at the CSFA’s photography department; she continued with her teaching in New York from 1951 onward.

Model did her first major groups of works outside New York. The photographs of visitors to the opera of San Francisco rank among her most striking portraits and illustrate her strategy of bringing out individual characters by exaggerating physical peculiarities.

In 1949 an assignment for the Ladies Home Journal took Lisette Model to Reno, Nevada. She photographed women staying at so-called “divorce ranches,” waiting for their divorces to be finalised. Thanks to more liberal laws, divorce was possible in Nevada after a waiting period of just a few weeks – compared to the patriarchal rules of other states, this was an uncomplicated way for women in particular to separate from their spouses. Lisette Model’s sympathy for her sitters becomes palpable. Unlike the pictures taken in San Francisco, these portraits are less expressive, but more melancholic instead.

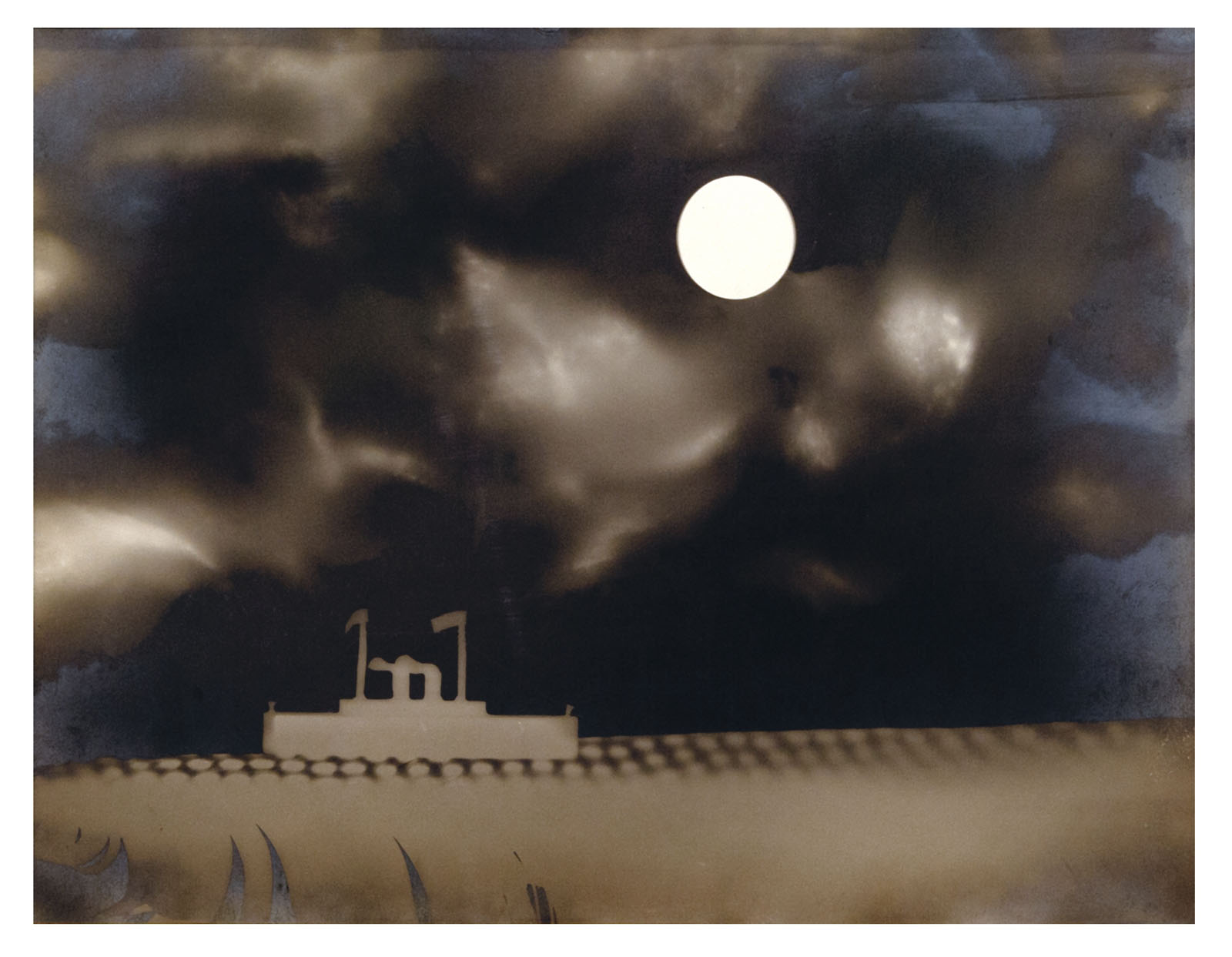

Venezuela

In the 1950s, in the wake of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s communist witch hunt, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) inquired into Lisette Model’s activities. Neighbours and even her grocer were questioned about the artist. In February 1954 two FBI agents finally interrogated Lisette Model and accused her of alleged membership in the communist party and of her actual affiliation with the Photo League, which had already disbanded in 1951 due to political pressure. The agents were unable to prove any wrongdoing on Model’s part, but classified her as uncooperative and recommended that she be placed on the security watch list. As a result of these accusations, Model lost some of her most important clients and was forced to supplement her income by working as a teacher.

Plagued by financial difficulties, she travelled to Caracas in 1954, accepting an invitation extended by the Venezuelan government. By then, Venezuela had been under the presidency of Marcos Evangelista Pérez Jiménez for two years – a military officer and dictator who modernised Caracas and exploited the country’s rich oil reserves. In photographs that were unusual for her in terms of motif and style, Model captured the technical infrastructure for oil production around Lake Maracaibo. Because of their gloomy atmosphere, the images were unsuitable for use in advertising and propaganda. Unsettled by the paranoia of the McCarthy era, the photographer often found it difficult to relate to her surroundings.

Jazz

As a result of the reprisals during the McCarthy era, Lisette Model photographed significantly less in the 1950s than in the promising decades before. One exception were the photographs she took during a horserace in New York in 1956, where she directed her attention at the audience instead of the competition. Her preoccupation with the subject of jazz was most intense. It is Model’s largest body of work, which developed from her photographs of New York nightclubs in the 1940s. Model was one of the few women to photograph jazz events such as the Newport Jazz Festival or concerts of the Lenox School of Jazz at the Berkshire Music Barn in Massachusetts. Highly musical herself, Model knew how to use her straightforward approach to convey the passion and intensity of the musicians’ playing as an immediate experience. No musician was photographed by her as often as Billie Holiday. One of Lisette Model’s last pictures, taken in 1959, shows the singer lying in her coffin.

In the 1950s, Model planned to publish her jazz photographs. It would have been the first monographic jazz book in history, but the project failed when her former client at Harper’s Bazaar discredited Model as a “troublemaker” and, due to her “political unreliability,” dissuaded potential financial backers.

Starting in the 1970s, Lisette Model was rediscovered in exhibitions and interviews. After years of effort, the first monograph on her work, with an introduction by Berenice Abbott, came out in 1979 with the renowned publisher Aperture. It is now considered an incunabulum within the photo book genre. The Albertina owns the hitherto unpublished dummy with original prints. Originally, the book was to be printed with a comprehensive biography of the artist penned by author Phillip Lopate. Dissatisfied with the text, Model had the manuscript withdrawn and commented on it with scathing remarks: “I thought an introduction was to be written – not that I was to be put on trial,” she noted down on the title page.

Model’s behaviour was indicative of the protective shield she had built around her private life as a result of her threatening encounter with the paranoia of the McCarthy era. In her public statements and interviews she obscured facts and details of her biography. She resisted simplistic interpretations of her work, but also concealed and marginalised references to politically explosive works, such as the publication of her photographs from Nice in the communist publication Regards in the mid-1930s.

Press release from The Albertina Museum

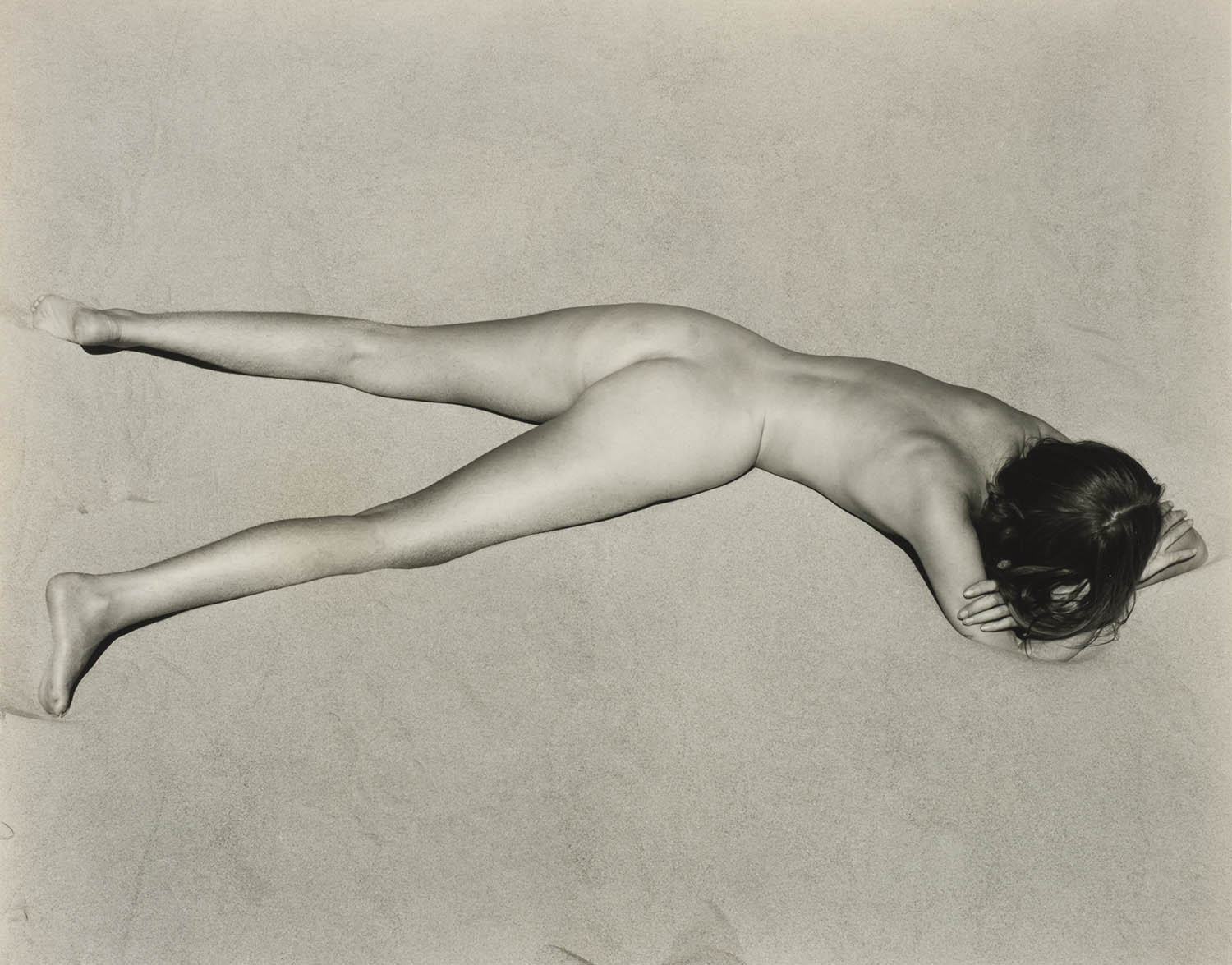

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Coney Island Bather, New York

1939-1941

Gelatin silver print

49.5 × 39.3cm

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

©️ Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy of baudoin lebon and Avi Keitelman

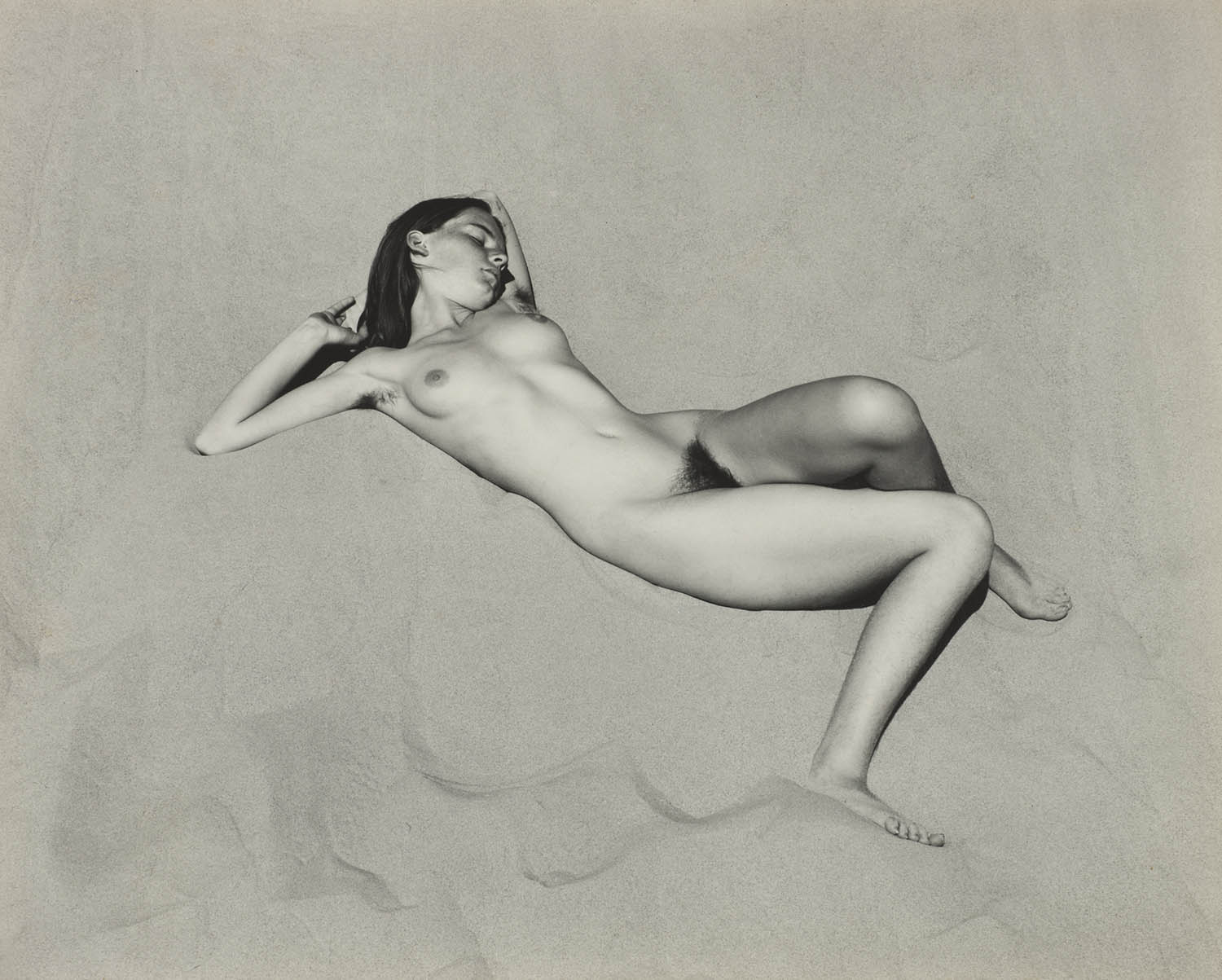

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Fashion Show, Hotel Pierre, New York

1940-1946

Gelatin silver print

39.3 x 49.2 cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna, Permanent Loan Austrian Ludwig Foundation for Arts and Science

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris / Keitelman, Brussels

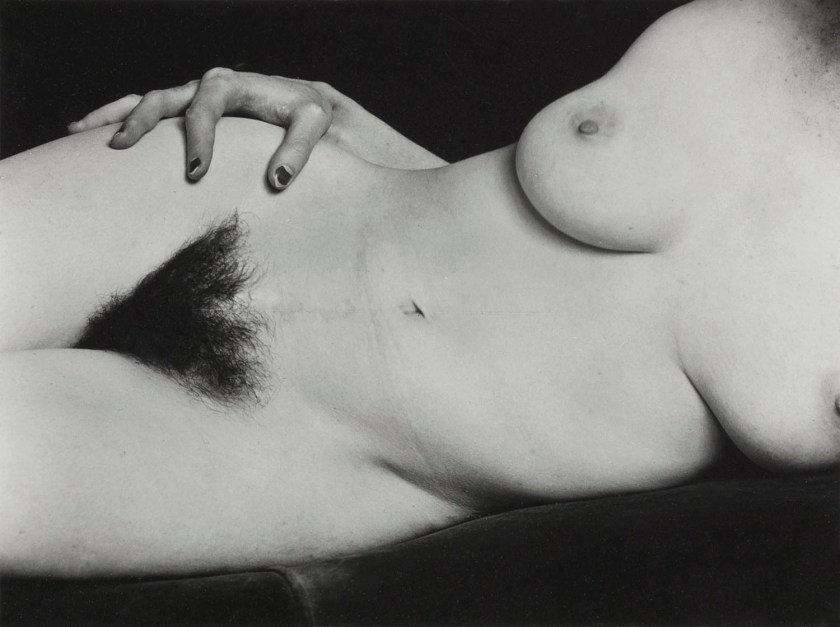

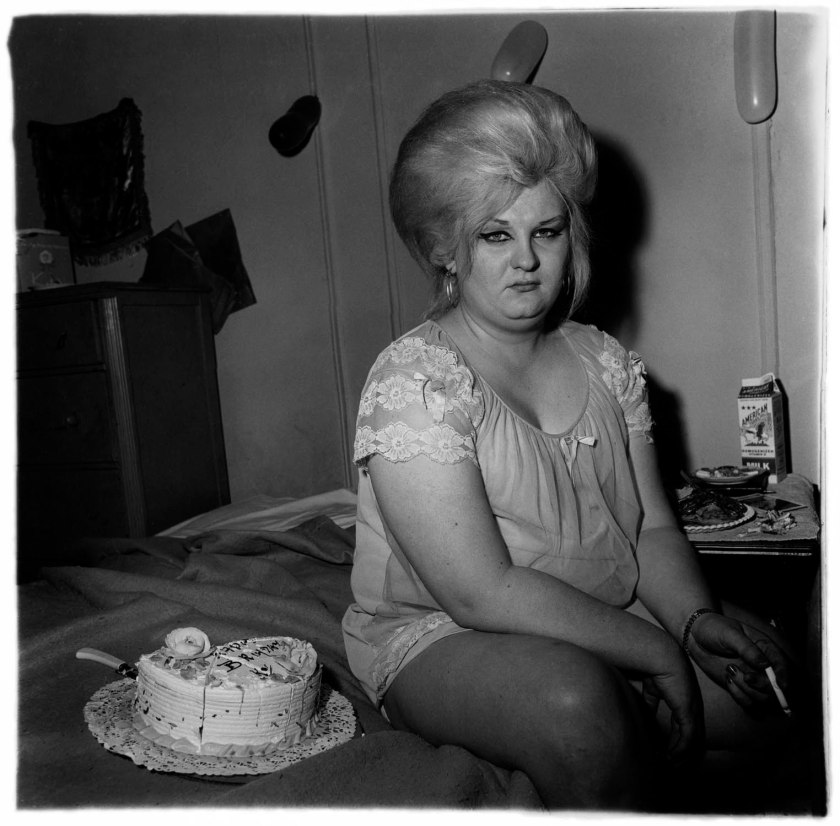

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Lower East Side, New York

1940-1947

34.6 × 27.1cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris / Keitelman, Brussels

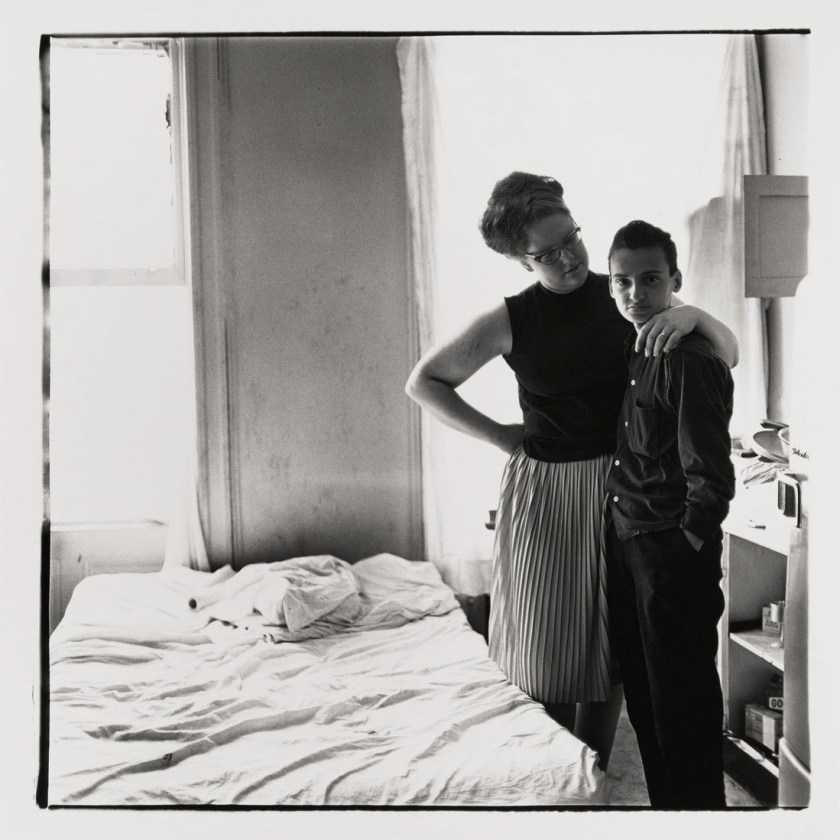

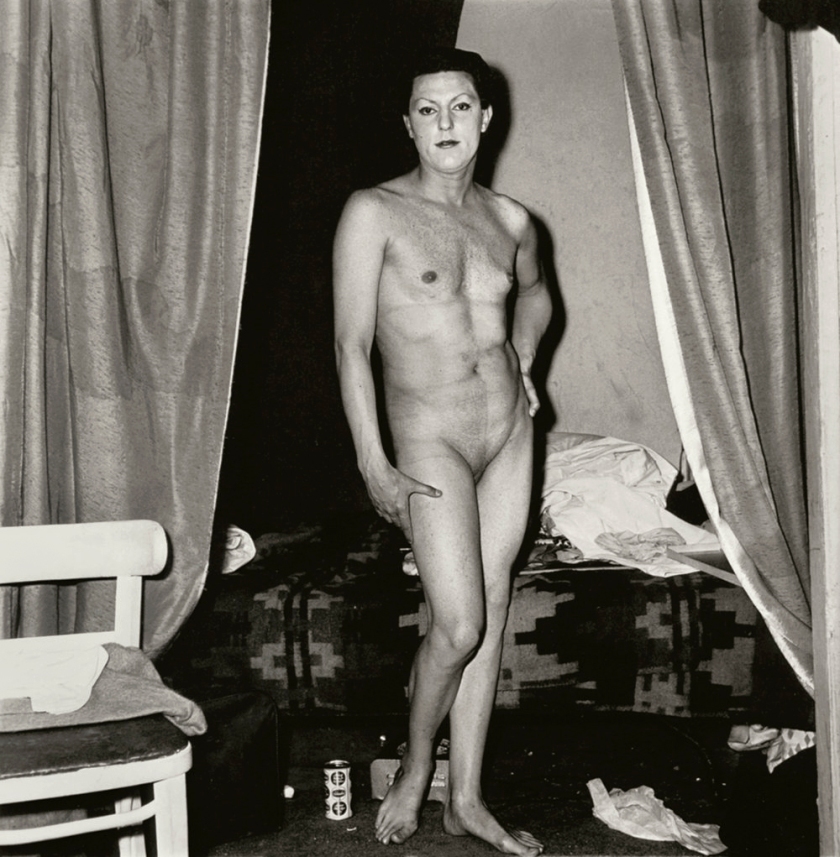

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Albert-Alberta, Hubert’s Forty-second Street Flea Circus, New York

1945, printed 1980s

Gelatin silver print

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Female impersonator

c. 1945

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Opera, San Francisco

1949

Gelatin silver print

34 × 26.6cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris / Keitelman, Brussels

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Opera, San Francisco

1949

Gelatin silver print

© The Lisette Model Foundation

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Lisette Model (Vienna, 1901 – New York, 1983) was one of the main practitioners of North American direct photography. Born into a Jewish bourgeois family in Vienna, she studied piano and singing with Arnold Schönberg. In 1926 she moved to Paris where she became interested in painting and photography. Due to the oncoming war in Europe and growing anti-Semitism spreading throughout the continent, Model moved to New York in 1938 and began to work as a photographer for the magazine Harper’s Bazaar under the guidance of Alexey Brodovitch. She became a member of the Photo League.

Free of any sort of indoctrination, Model’s work stands out for her use of direct portraiture and for focusing on the peculiarities of the people she portrayed. Her images are full of low-angle shots, radical framings, and powerful black and white contrasts, making them greatly expressive. Some of her most renowned series – Promenade des Anglais, Reflections, and Running Legs – were produced in the French Côte d’Azur and in New York.

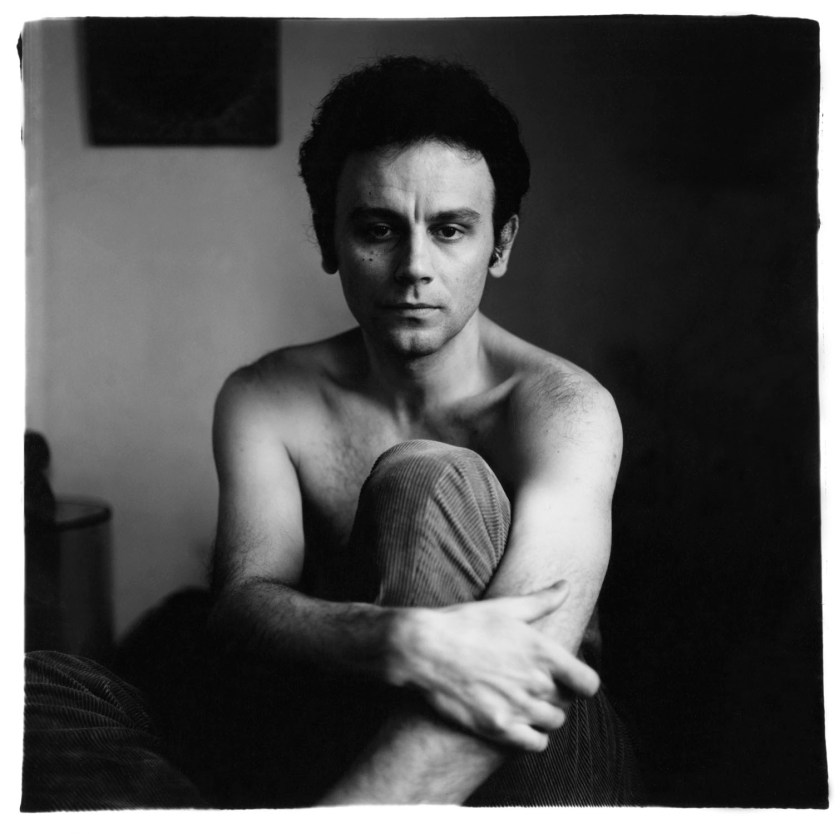

At the end of her career Model worked with Gerhard Sander, grandson of the photographer August Sander, who became her art dealer and lab assistant. Her work as an instructor was also notable. She began teaching in 1949 at the California School of Fine Arts and continued to teach throughout her life at other institutions such as the New School for Social Research. Her role as a professor would leave a mark on some of the most important photographers of the following generation, such as Diane Arbus, Larry Fink, and Peter Hujar, to name a few.

Text from the Fundacion MAPFRE website

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Singer at the Metropole Café, New York

1946

Gelatin silver print

49.6 x 39.8 cm

The ALBERTINA Museum, Vienna

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy Lebon, Paris /

Keitelman, Brussels

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Woman with Veil, San Francisco

1949

Gelatin silver print

49.8 x 10.1 cm

Estate of Gerd Sander, Julian Sander Gallery, Cologne

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy of baudoin lebon and Avi Keitelman

Closeness that does not comfort

Model’s photographs are close. Uncomfortably close. Faces, bodies, gestures fill the frame, often to the limit of what is bearable. The famous tight cropping, often decided only in the darkroom, frees the people from their surroundings and confronts the viewer with full presence. There is no escaping. No decorative surroundings.

And yet there is no voyeurism. No mockery. Despite all the harshness, these images carry a form of respect, often with a good dose of humor or, depending on the subject, social criticism. You sense that someone is looking here, not looking down. There is tension hanging in the air – between ruthlessness and empathy – and it keeps the work relevant to this day.

Anonymous. “Zeit hinzusehen: Lisette Model in der Albertina,” on the ViennaCultgram website Nd [online] Cited 02/02/2026. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Ollie McLaughlin, Hotel Viking, Newport Jazz Festival, Rhode Island

1956

Gelatin silver print

27.5 × 34.9cm

© Estate of Lisette Model, courtesy of baudoin lebon and Avi Keitelman

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Ella Fitzgerald

1954

Gelatin silver print

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Dizzy Gillespie, New York Jazz Festival

1956

Gelatin silver print

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

Bud Powell, New York Jazz Festival

1957

Gelatin silver print

The Albertina Museum

Albertinaplatz 1

1010 Vienna

Phone: +43 (0)1 534 83 0

Daily 10am – 6pm

Except Wednesday and Friday 10am – 9pm

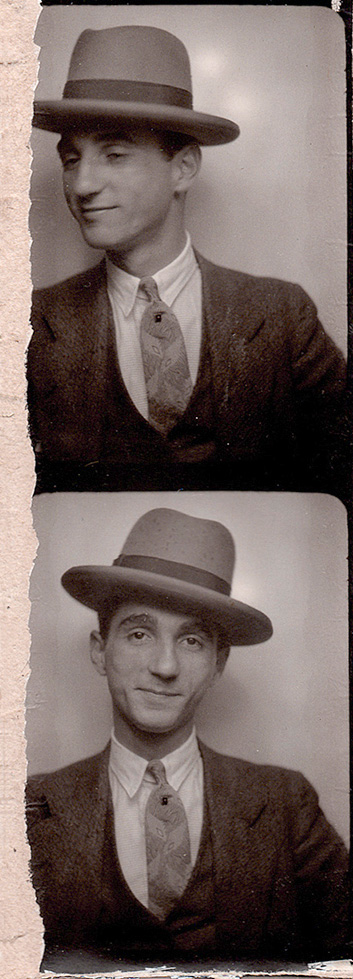

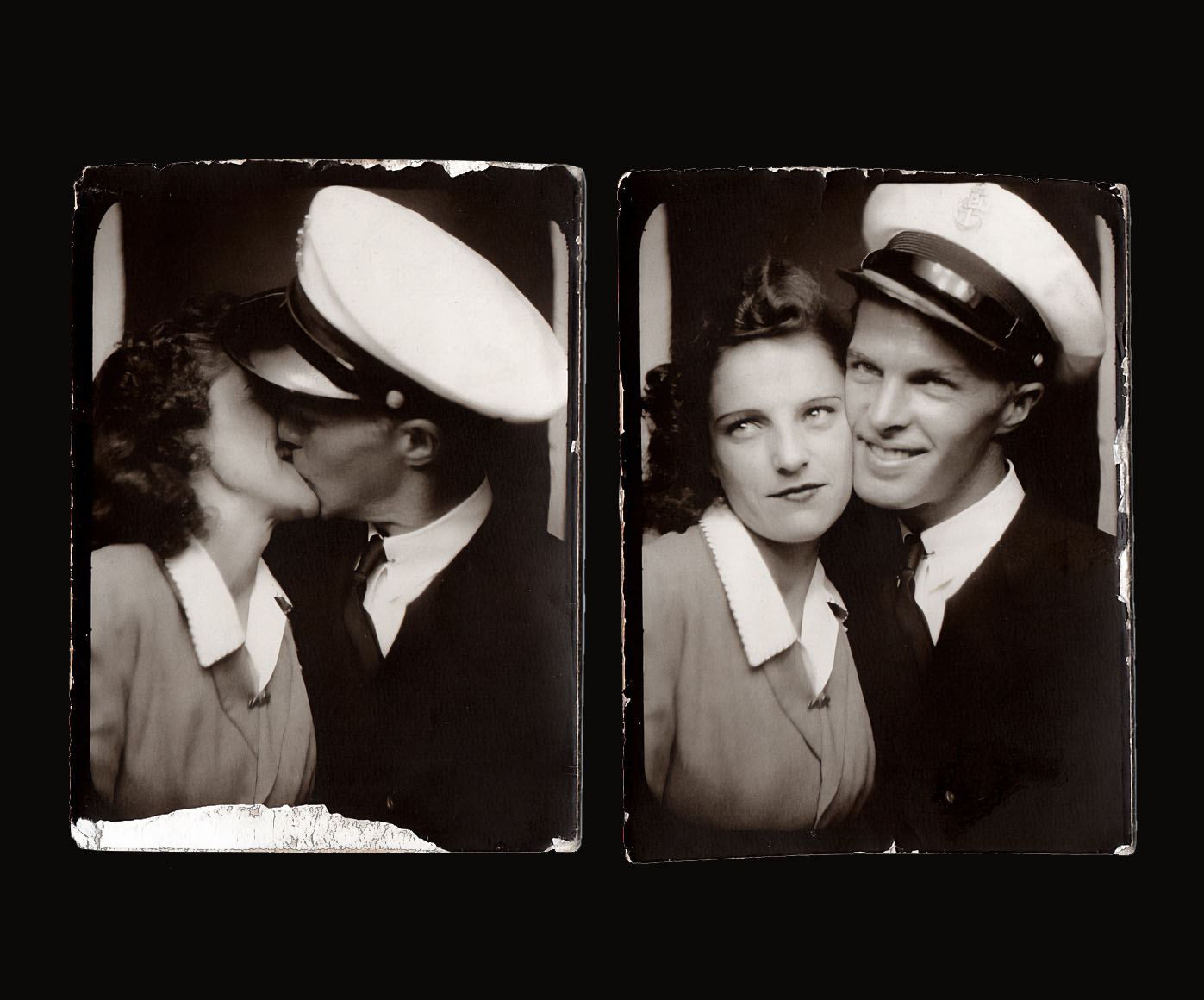

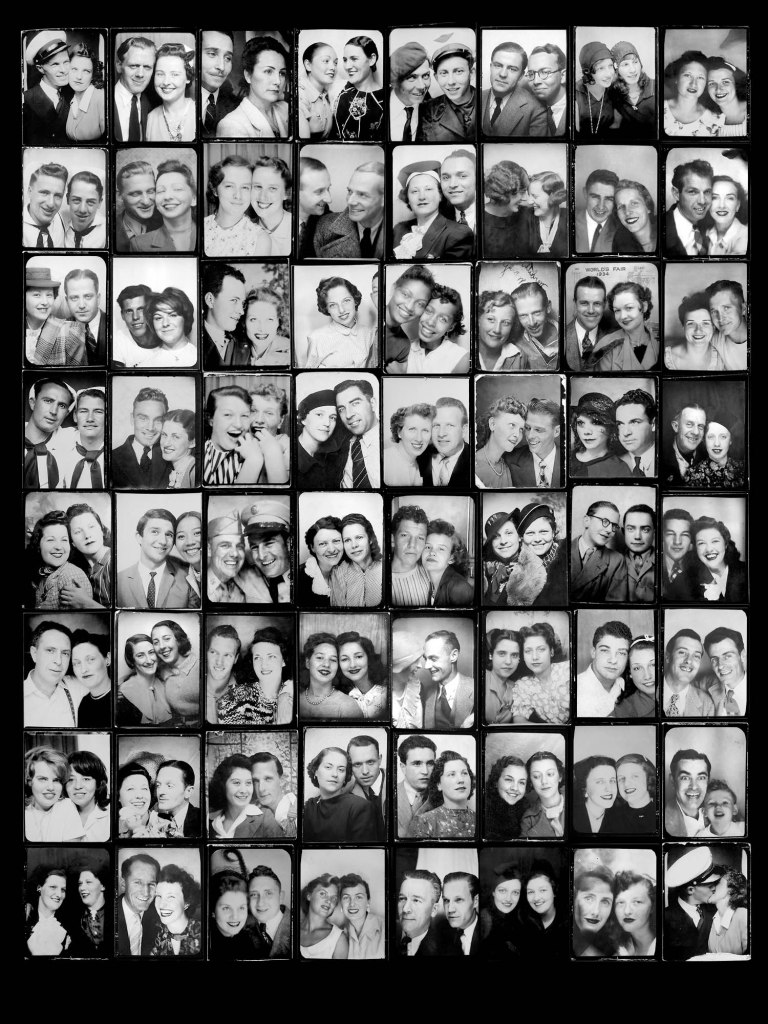

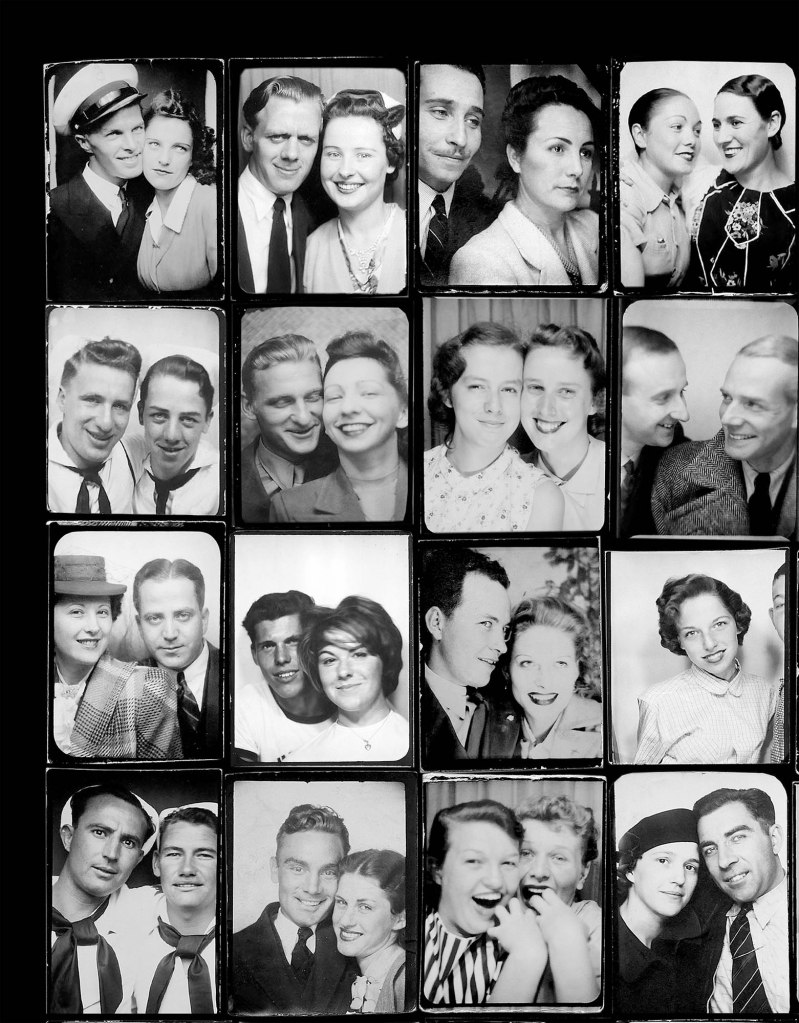

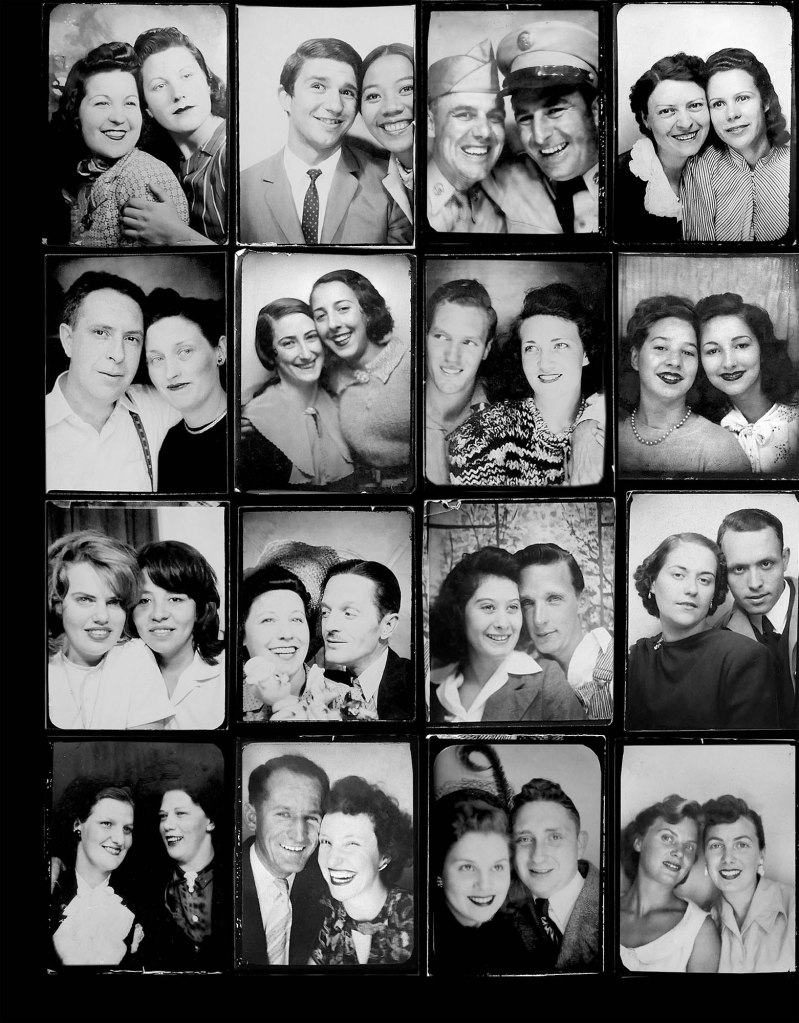

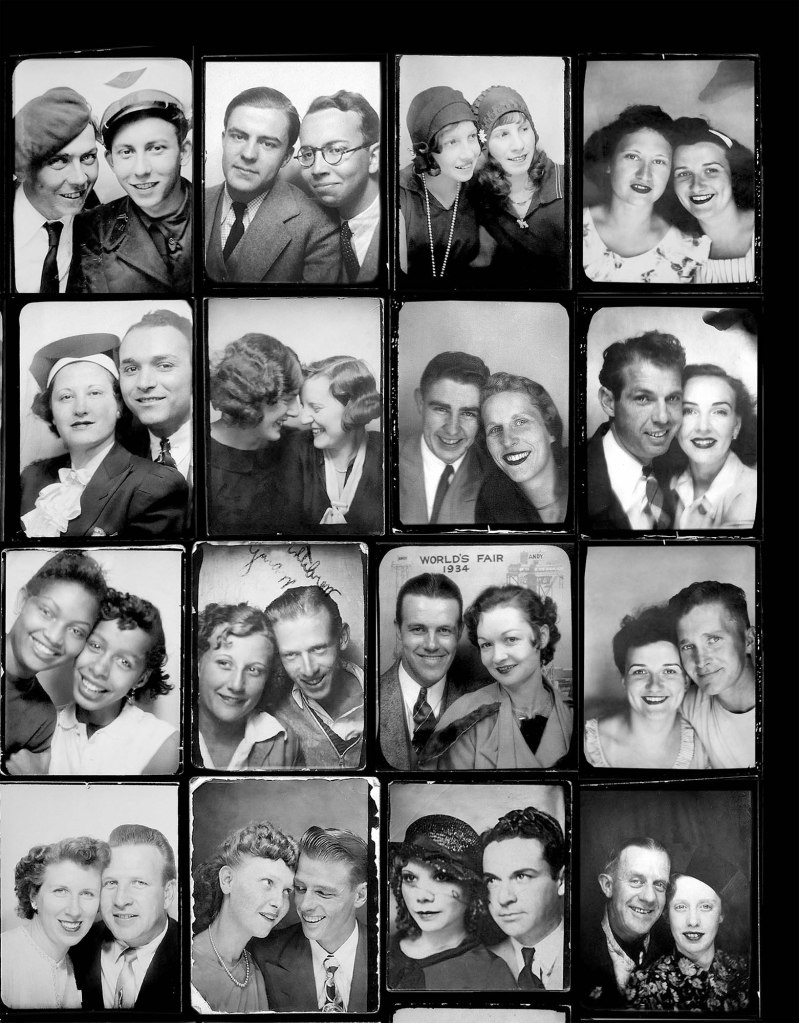

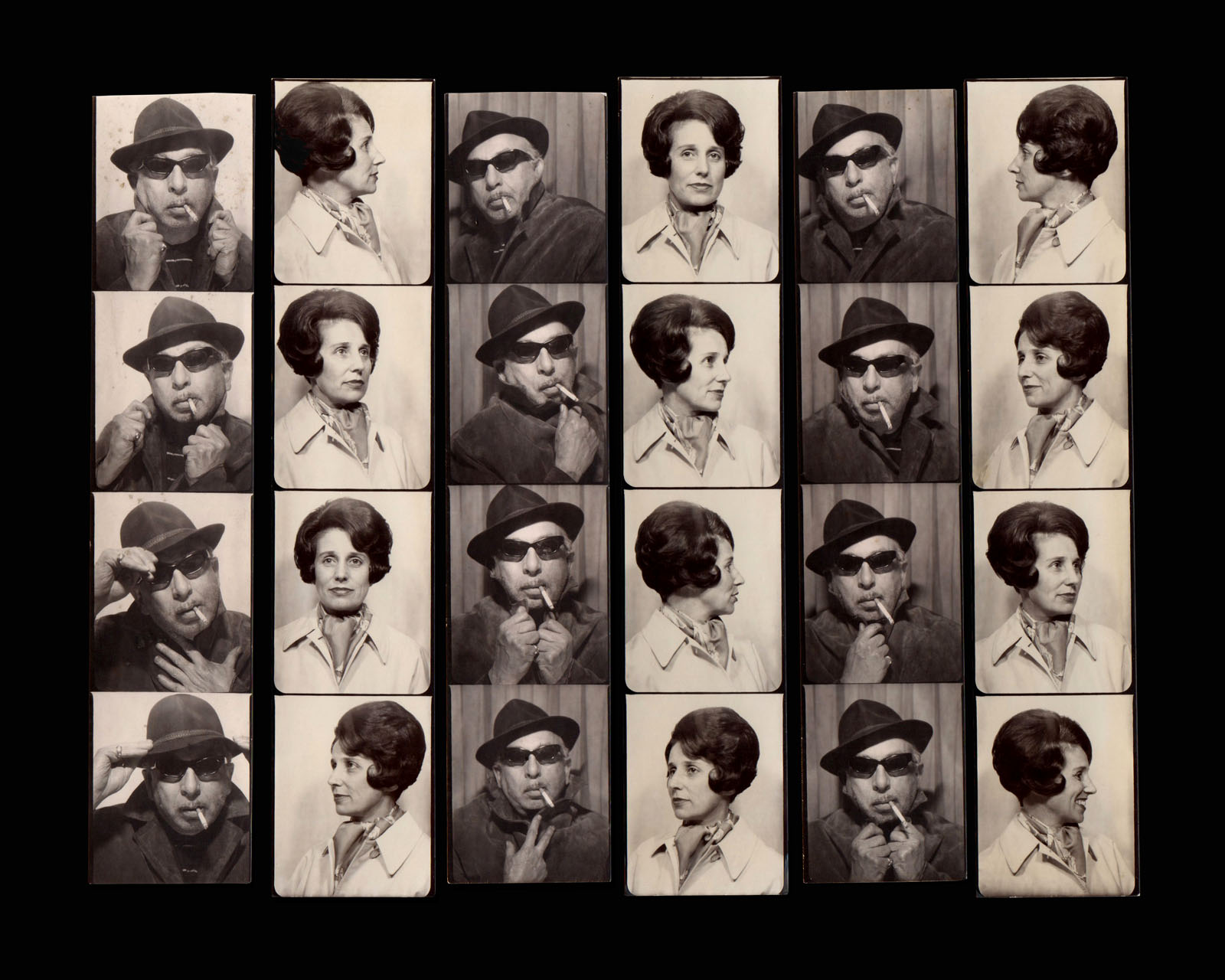

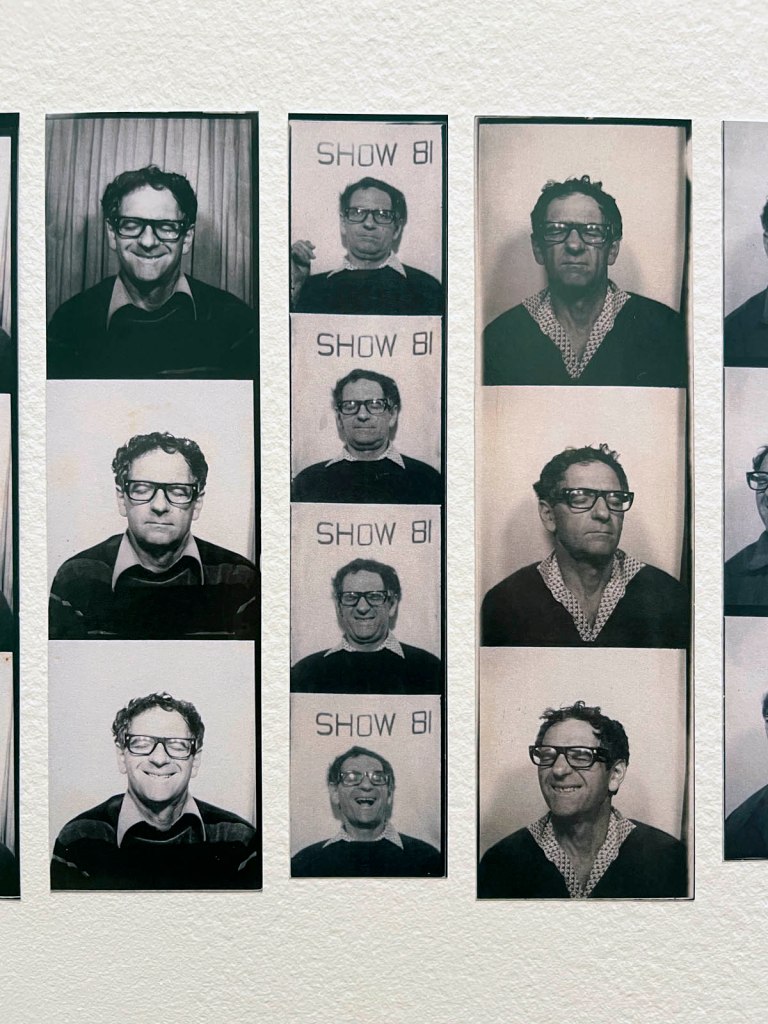

!['Untitled [Women Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s from the exhibition 'Strike a Pose! 100 Years of the Photobooth' at The Photographers' Gallery, London, October 2025 - February 2026 'Untitled [Women Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s from the exhibition 'Strike a Pose! 100 Years of the Photobooth' at The Photographers' Gallery, London, October 2025 - February 2026](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/women-photobooth-portraits.jpg)

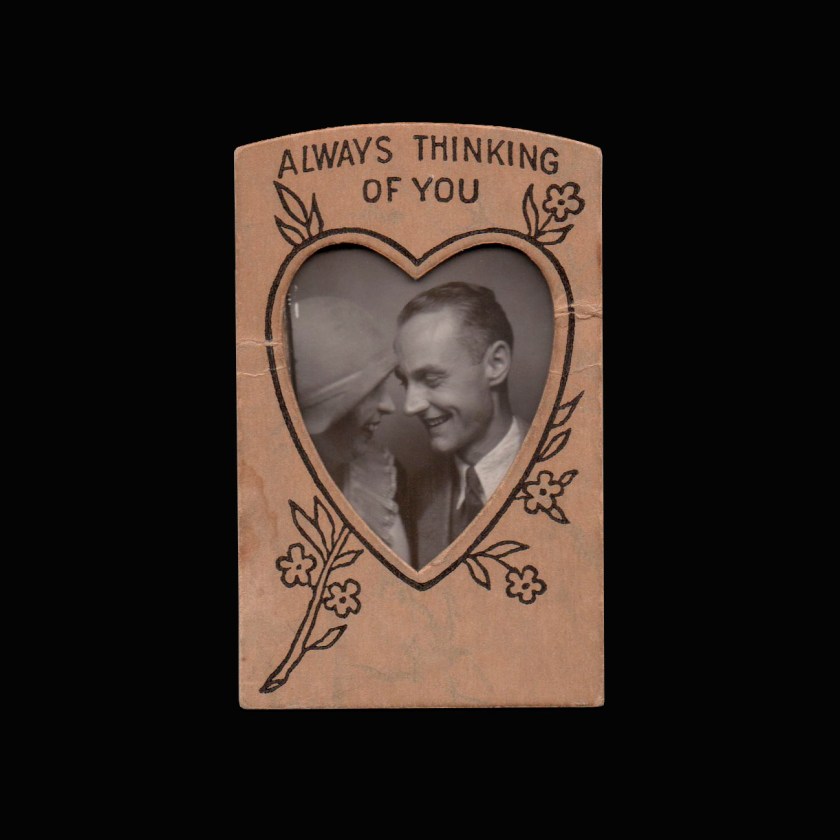

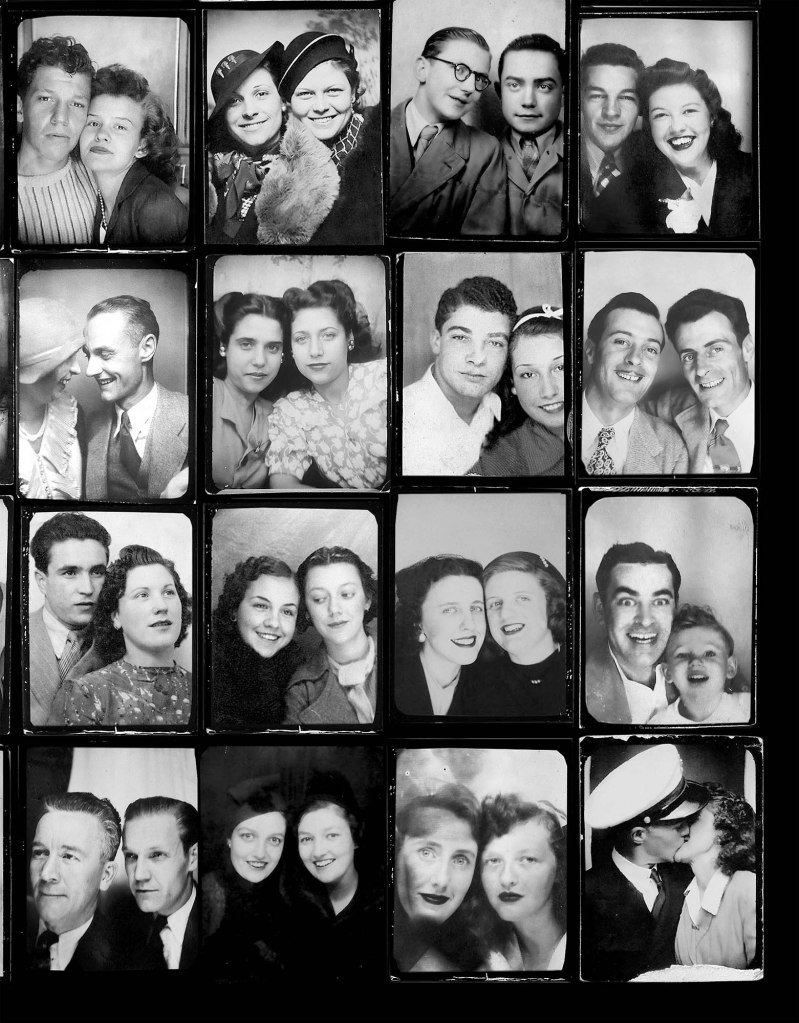

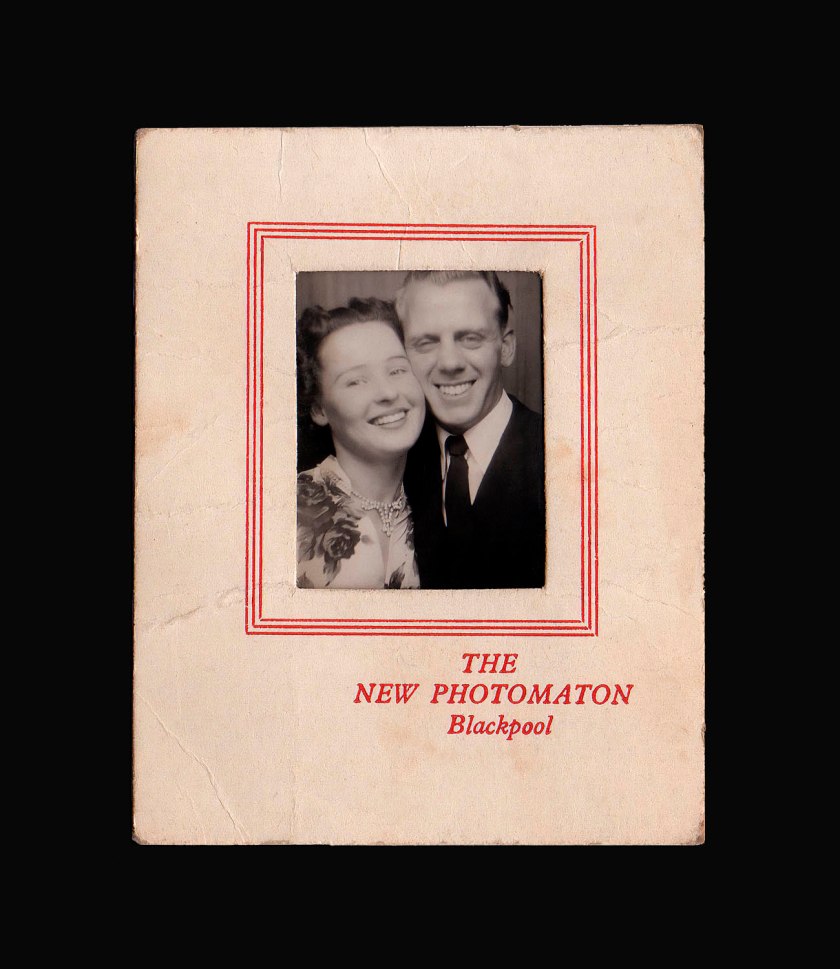

!['Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s 'Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/untitled-color-photobooth-portraits.jpg?w=801)

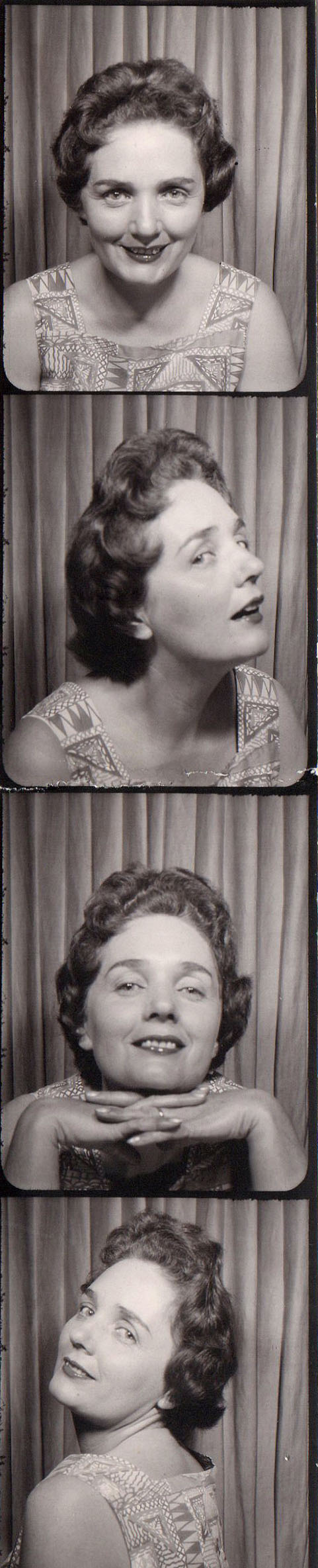

!['Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s (detail) 'Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/untitled-color-photobooth-portraits-a.jpg)

!['Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s (detail) 'Untitled [Color Photobooth Portraits]' c. 1940s-1950s (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/untitled-color-photobooth-portraits-b.jpg)

![Dennis McGuire (American) 'Untitled [Diane Arbus using her medium format Mamiya camera]' Nd Dennis McGuire (American) 'Untitled [Diane Arbus using her medium format Mamiya camera]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/dennis-mcguire-diane-arbus.jpg)

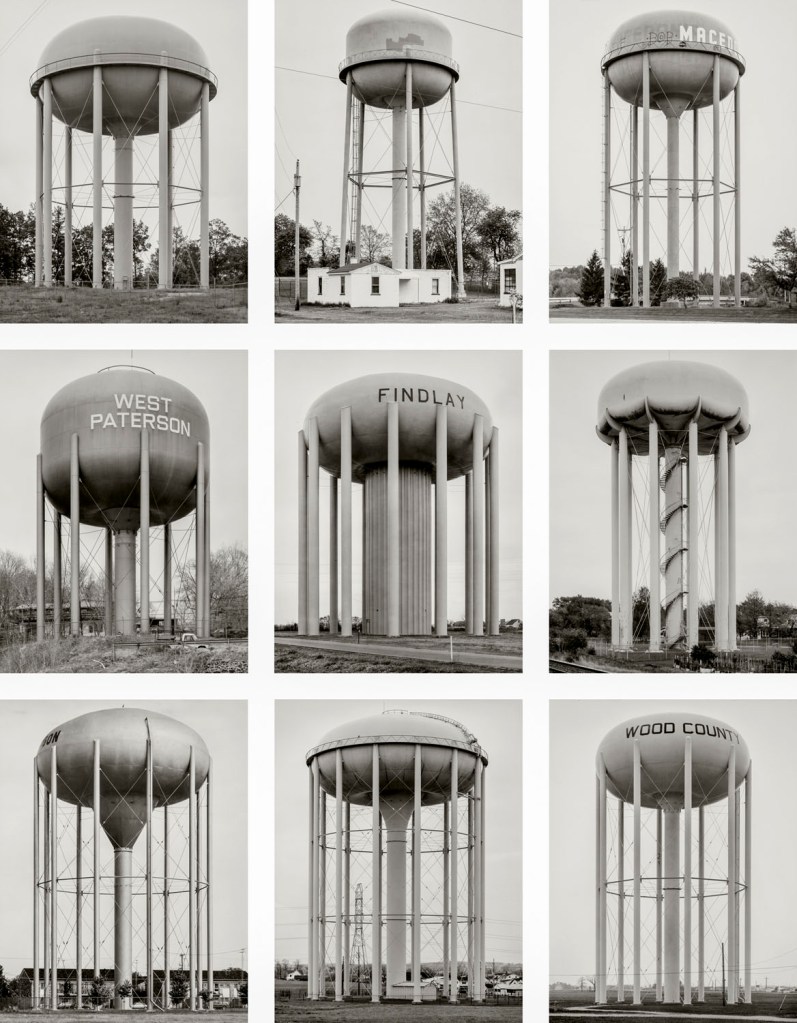

![Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969 Heinrich Riebesehl (German, 1938-2010) 'Menschen Im Fahrstuhl, 20.11.1969' [People in the Elevator, 20.11.1969] 1969](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/2-typologien_heinrich-riebesehl_siae_sm.jpg)

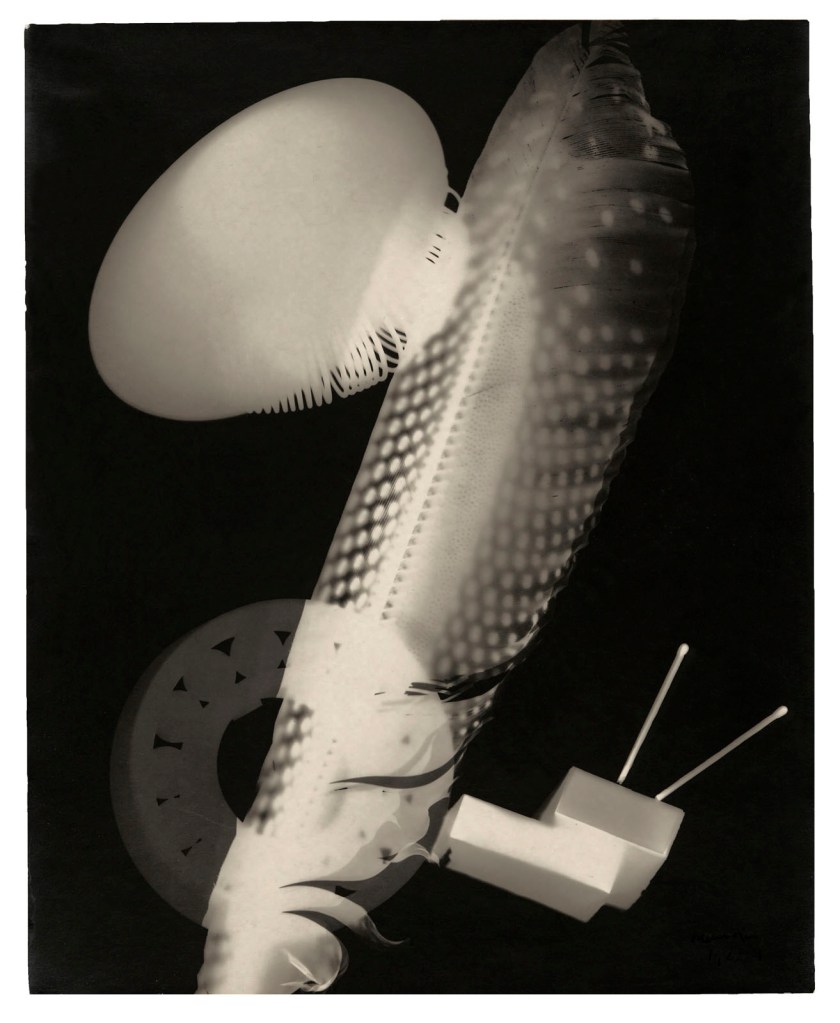

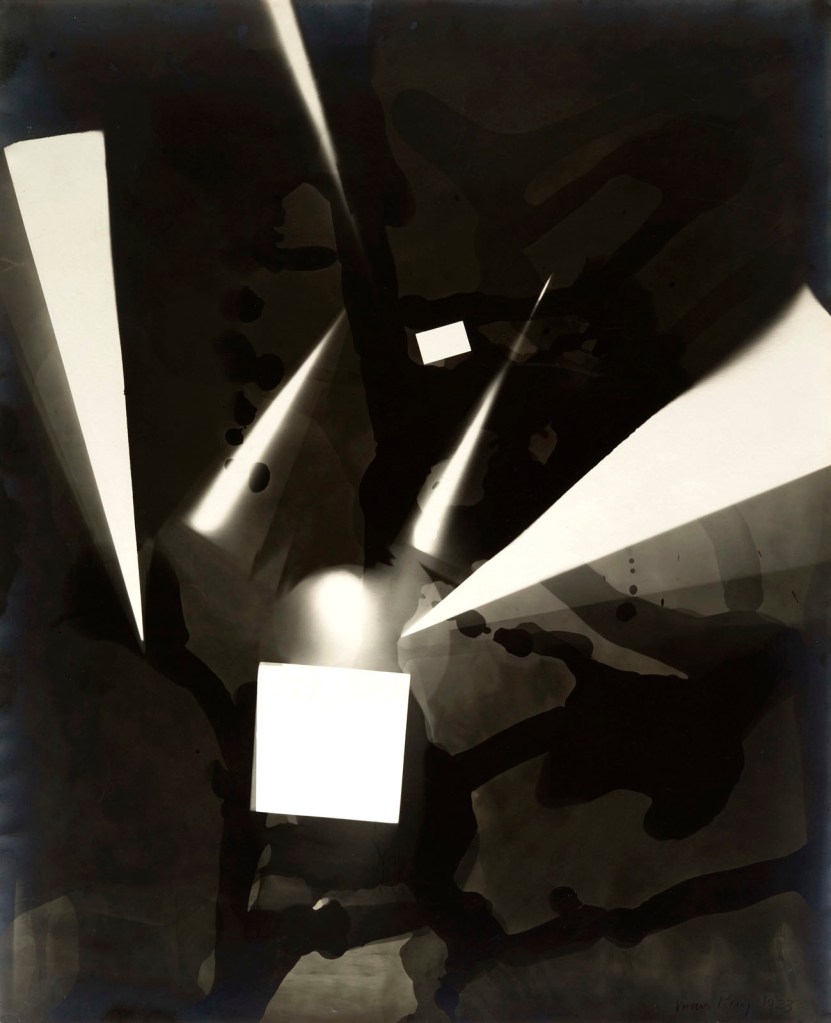

![Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) 'Torse (Retour à la raison)' (Torso [Return to Reason]) 1923, printed c. 1935 Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

'Torse (Retour à la raison)' (Torso [Return to Reason]) 1923, printed c. 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/man-ray-retour-c3a0-la-raison-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.