Exhibition dates: 20th November 2019 – 15th March 2020

Curators: Dora Maar is curated by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, Curator, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Damarice Amao, Assistant Curator, Centre Pompidou, Paris and Amanda Maddox, Associate Curator, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles with Emma Lewis, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The Tate Modern presentation is curated by Emma Lewis, Assistant Curator with Emma Jones, Curatorial Assistant, Tate Modern.

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled (Hand-Shell)

1934

Gelatin silver print on paper

401 x 289 mm

Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

What a creative woman. But yet another abused by the ego of a male, that of her lover, Picasso.

Beth Gersh-Nesic observes, “Was Dora Maar’s brilliant career cut short by the typical conflicts facing professional women in the 1930s, and even today? Or was she a victim of Picasso’s psychological abuse, which chipped away at her original confidence? Was she compromised to the point that she only wanted to please the man she loved? According to art historian John Richardson, Dora Maar sacrificed her gifts on the altar of her art god, her idol, Picasso. Based on the early Surrealist photographs we see in her retrospective, one can only wish she hadn’t taken up with Picasso, for it seems she might have achieved far more in her lifetime without him.”

What we can say is that Maar left behind a strong body of photographic work – from fashion and commercial, to restrained, classical formalism with surrealist inflections; from street photography to “the stuff of delirium and nightmare, [which] taps into the unconscious, internalised sublime”, her Portrait of Ubu (1936, below) reminding me strongly of William Blake’s painting The Ghost of a Flea (c. 1819). Ubu is “a ghastly being of indeterminate origin and melancholy aspect… [an idea] something like l’informe, the concept Maar’s lover Georges Bataille coined to describe his fellow-Surrealists’ admiration for all things larval and grotesquely about-to-be.” Ubu is a her dark notion of a street “urchin”.

Her warped photomontages are technical marvels. “”She captures the mysterious,” Caws wrote, “in a combination of the unresolved and the sharply angled. This frequently creates a sense of ambiguity, even menace.” Caws notes that Dora Maar responded to Louis Aragon’s invocation “for each person there is one image to find that will disturb the whole universe.” Maar’s images managed to “disturb and reveal” with a bit of the macabre mixed in.”

But her images are more than a bit of this and a bit of that. They possess a utilitarian feeling in the enunciation of their menace, which makes them all the more effective when impinging on our waking dreams. Susan Sontag notes, “Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognise as modern” (Sontag, On Photography, p. 2). Thicken is the critical word. Maar’s photographs thicken our atmospheric (and mental) miasma, prescient of our modern world full of dark passages: pitch black sewers, fatbergs, drone strikes, bush fire skies, virus, murder and mayhem. In the back of my head. My eyes. Roll, roll, roll. Skewered. Roasted.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

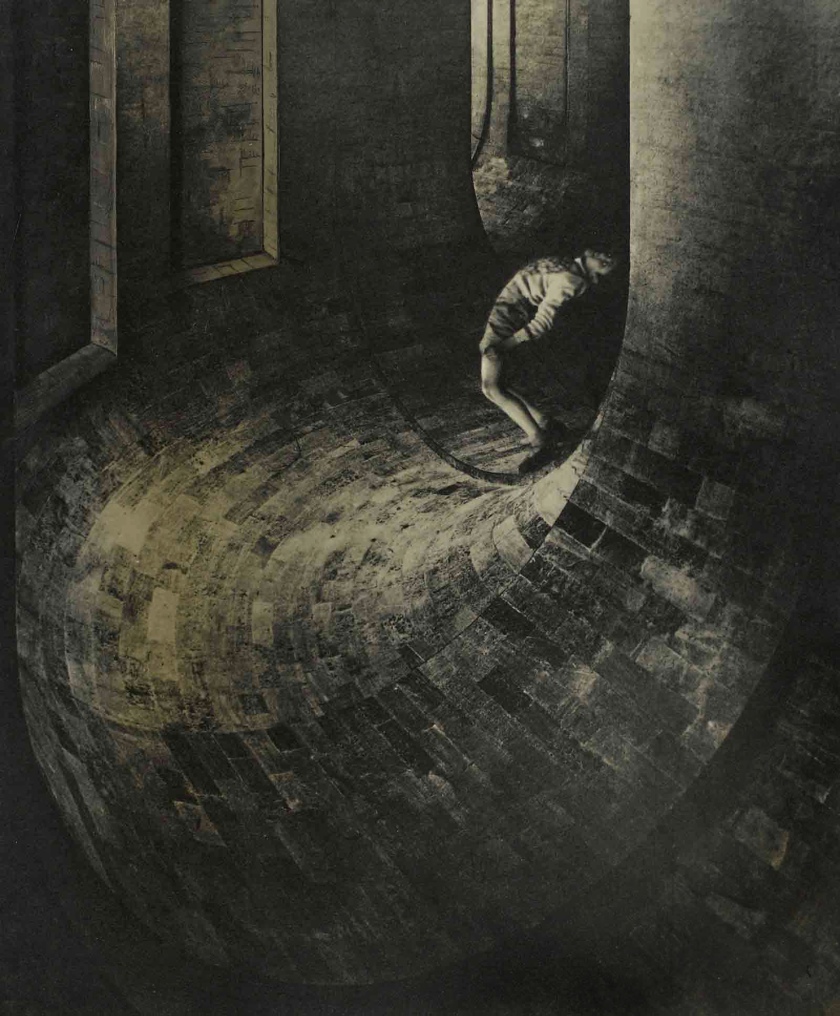

The most accomplished examples of Maar’s art are the photomontages of 1935 and 1936. There were already many vaults and arches in her Mont-Saint-Michel pictures; now she took the cloistral galleries of the Orangerie at Versailles, upended them so that they looked like sewers, and populated them with cryptic beings engaged in arcane rituals or dramas. In “The Simulator,” [below] a boy from one of her street photographs is bent backward at an obscene angle; Maar has retouched his eyes so that they roll back in his head toward us, like one of those thrashing hysterics photographed in the nineteenth century. In “29 Rue d’Astorg” (below) – of which Maar made several versions, black-and-white and hand-coloured – a human figure with a curtailed, avian head is seated beneath arches that have been subtly warped in the darkroom.

Brian Dillon. “The Voraciousness and Oddity of Dora Maar’s Pictures,” on The New Yorker website May 21, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

During the 1930s, Dora Maar’s provocative photomontages became celebrated icons of surrealism.

Her eye for the unusual also translated to her commercial photography, including fashion and advertising, as well as to her social documentary projects. In Europe’s increasingly fraught political climate, Maar signed her name to numerous left-wing manifestos – a radical gesture for a woman at that time.

Her relationship with Pablo Picasso had a profound effect on both their careers. She documented the creation of his most political work, Guernica 1937. He painted her many times, including Weeping Woman 1937. Together they made a series of portraits combining experimental photographic and printmaking techniques.

In middle and later life Maar withdrew from photography. She concentrated on painting and found stimulation and solace in poetry, religion, and philosophy, returning to her darkroom only in her seventies.

This exhibition will explore the breadth of Maar’s long career in the context of work by her contemporaries.

Text from the Tate Modern website

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Woman sitting in profile, the bust dressed in a blouse made of tattoo patterns drawn on the photograph

c. 1930

Gelatin silver print

Private Collection

© Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Child with a Beret

c. 1932

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy VEGAP / Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Barcelona, Saleswomen in the Butcher Shop

1933

Silver Gelatin Print

48.7 x 38.8cm

Private Collection

© Adagp, Paris 2019

Photo: © Fotogasull

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Blind Street Peddler, Barcelona

1933

Gelatin silver print

Image: 39.3 x 29.3cm (15 1/2 x 11 9/16 in.)

Gift of David Raymond

The Cleveland Museum of Art

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Street Boy on the Corner of the rue de Genets

1933

Gelatin silver print

Harvard Art Museums/ Fogg Museum, Richard and Ronay Menschel Fund for the Acquisition of Photographs

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Repent for the Kingdom of Heaven is at Hand

1934

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 24.3 × 18cm (9 9/16 × 7 1/16 in.)

© Dora Maar Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Gift of David and Marcia Raymond

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Stairwell and Plants in Kew Gardens

1934

Gelatin silver print, ferrotyped

Image: 28 x 24cm (11 x 9 7/16 in.)

John L. Severance Fund

The Cleveland Museum of Art

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Pearly King collecting money for the Empire Day

1935

Gelatin silver print

Tate

© Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Carousel at Night

1931-1936

Gelatin silver print, ferrotyped

Image: 25 x 19.8cm (9 13/16 x 7 13/16 in.)

John L. Severance Fund

The Cleveland Museum of Art

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Installation views of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing, in the bottom image, the photographs Untitled (Nude) 1930s (left) and Untitled (Nude) c. 1938 (right)

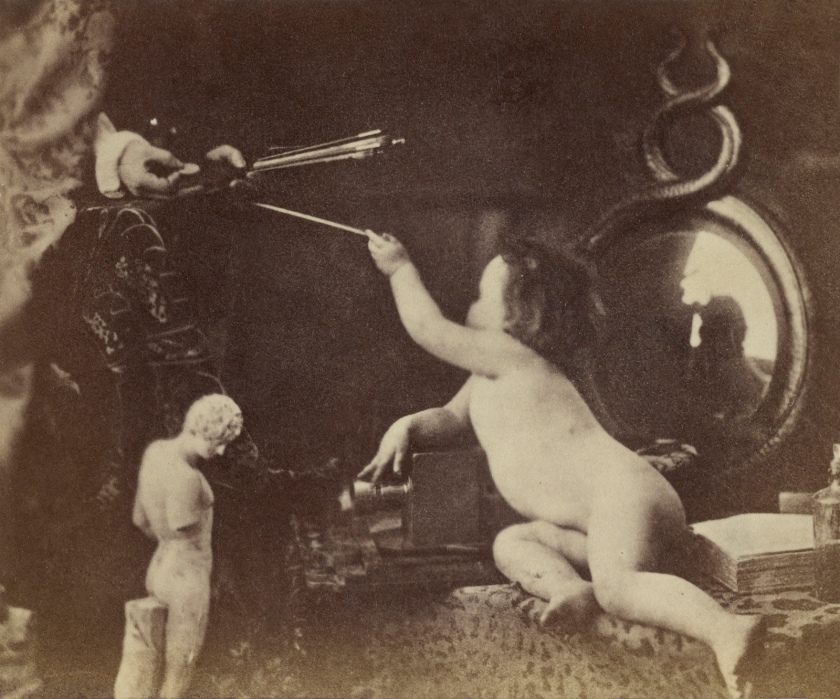

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Assia

1934

Gelatin silver print

26.4 x 19.5cm

This autumn, Tate Modern presents the first UK retrospective of the work of Dora Maar (1907-1997) whose provocative photographs and photomontages became celebrated icons of surrealism. Featuring over 200 works from a career spanning more than six decades, this exhibition shows how Maar’s eye for the unusual also translated to her commercial commissions, social documentary photographs, and paintings – key aspects of her practice which have, until now, remained little known.

Born Henriette Théodora Markovitch, Dora Maar grew up between Argentina and Paris and studied decorative arts and painting before switching her focus to photography. In doing so, Maar became part of a generation of women who seized the new professional opportunities offered by advertising and the illustrated press. Tate Modern’s exhibition will open with the most important examples of these commissioned works. Around 1931, Maar set up a studio with film set designer Pierre Kéfer specialising in portraiture, fashion photography and advertising. Works such as Untitled (Les années vous guettent) c. 1935 – believed to be an advertising project for face cream that Maar made by overlaying two negatives – will reveal Maar’s innovative approach to constructing images through staging, photomontage and collage. Striking nude studies such as that of famed model Assia Granatouroff will also reveal how women photographers like Maar were beginning to infiltrate relatively taboo genres such as erotica and nude photography.

During the 1930s, Maar was active in left-wing revolutionary groups led by artists and intellectuals. Reflecting this, her street photography from this time shot in Barcelona, Paris and London captured the reality of life during Europe’s economic depression. Maar shared these politics with the surrealists, becoming one of the few photographers to be included in the movement’s exhibitions and publications. A major highlight of the show will be outstanding examples of this area of Maar’s practice, including Portrait d’Ubu 1936, an enigmatic image thought to be an armadillo foetus, and the renowned photomontages 29, rue d’Astorg c. 1936 and Le Simulateur 1935. Collages and publications by André Breton, Georges Hugnet, Paul and Nusch Eluard, and Jacqueline Lamba will place Maar’s work in context with that of her inner circle.

In the winter of 1935-1936 Maar met Pablo Picasso and their relationship of around eight years had a profound effect on both their careers. She documented the creation of his most political work Guernica 1937, offering unprecedented insight into his working process. He in turn immortalised her in the motif of the ‘weeping woman’. Together they made a series of portraits that combined experimental photographic and printmaking techniques, anticipating her energetic return to painting in 1936. Featuring rarely seen, privately-owned canvases such as La Conversation 1937 and La Cage 1943, and never-before exhibited negatives from the Dora Maar collection at the Musée National d’art Moderne, the exhibition will shed new light on the dynamic between these two artists during the turbulent wartime years.

After the Second World War, Maar began dividing her time between Paris and the South of France. During this period, she explored diverse subject matter and styles before focusing on gestural, abstract paintings of the landscape surrounding her home. Though these works were exhibited to acclaim in London and Paris into the 1950s, Maar gradually withdrew from artistic circles. As a result, the second half of her life became shrouded in mystery and speculation. The exhibition will reunite over 20 works from this little-known – yet remarkably prolific – period. Dora Maar concludes with a substantial group of camera-less photographs that she made in the 1980s when, four decades after all but abandoning the medium, Maar returned to her darkroom.

Dora Maar is curated by Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, Curator, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Damarice Amao, Assistant Curator, Centre Pompidou, Paris and Amanda Maddox, Associate Curator, the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles with Emma Lewis, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The Tate Modern presentation is curated by Emma Lewis, Assistant Curator with Emma Jones, Curatorial Assistant, Tate Modern.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully-illustrated catalogue jointly published by Tate and the J. Paul Getty Museum and a programme of talks and events in the gallery.

Press release from Tate Britain [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Installation views of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing at second left, Untitled (Study of Beauty) (c. 1931, below)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled (Study of Beauty)

c. 1931

Gelatin silver print

© 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled (Lee Miller) (multiple exposure)

c. 1933

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled (Mannequin sitting in profile in dress and evening jacket)

c. 1932-1935

Gelatin silver print enhanced with colours

29.9 x 23.8cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle

© ADAGP, Paris, 2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled (Fashion photograph Model star)

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

300 x 200 mm

Collection Therond

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Model in Swimsuit

1936

Gelatin silver on paper

197 x 167 mm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Portrait of Lise Deharme, chez elle devant sa cage a oiseaux

Portrait of Lise Deharme, at home in front of her birdcage

1936

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Publicity Study, Pétrole Hahn

1934-1935

Silver gelatin print on a flexible support in cellulose nitrate

17.6 x 24cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP

Associated with Pierre Kéfer from 1930 to 1934, she collaborated in 1931 on the photographic illustration of the art historian Germain Bazin’s book Le Mont Saint-Michel (1935). She then shared a studio with Brassaï, after which Emmanuel Sougez, the spokesman for the New Photography movement, became her mentor. Her work met the aesthetic criteria of the time: close-ups of flowers and objects, and photograms in the style of Man Ray. She also took portraits, original publicity shots, and fashion and erotic photographs. In 1934, while traveling alone in Spain, Paris and London, she shot a vast number of urban views (posters, shop windows, ordinary people). Both a passionate lover and committed intellectual, she became the mistress of the filmmaker Louis Chavance and of the writer Georges Bataille, whom she met in a left-wing activist group. She signed the Contre-Attaque manifesto and rubbed shoulders with the agitprop artistic group Octobre. A close friend of Jacqueline Lamba, who became Breton’s wife, she was fully involved in the surrealist group, of whose members she made many portraits. At the height of her creativity in 1935-1936, she composed strange and bold photomontages, the most famous being 29, rue d’Astorg and The Simulator (both below). Some of her compositions verge on eroticism, like the photomontage showing fingers crawling out of a shell and sensually digging into the sand (Untitled, 1933-1934, top). She also used her city photographs as backdrops for unsettling scenes: her Portrait of Ubu (1936, below) – in fact the picture of an armadillo foetus – conforms to the surrealists’ fascination for macabre and deformity.

Anne Reverseau. “Dora Maar,” from the Dictionnaire universel des créatrices on the Archives of Women Artists Research & Exhibitions website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

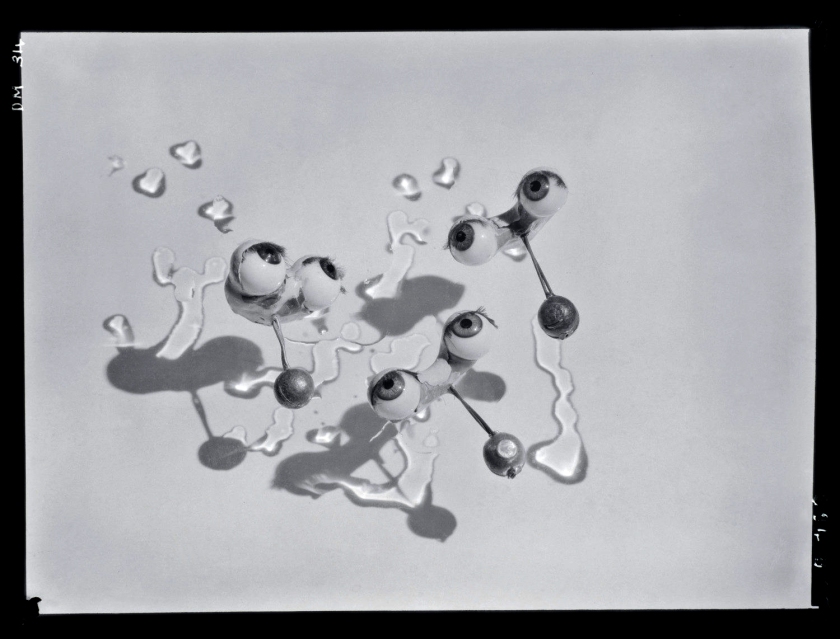

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Les yeux (The eyes)

c. 1932-1935

Silver print on flexible media

29.5 x 23.5cm

© Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, © ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

1935

Photomontage

232 x 150 mm

Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou (Paris, France)

© Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

When Maar began her career, the illustrated press was expanding quickly. This created a growing market for experimental photography. Maar embraced this opportunity, exploring the creative potential of staged images, darkroom experiments, collage and photomontage.

Most of Maar’s work had one thing in common: an uncanny atmosphere. Her connection to the surrealists led her to create fantastical images. This included using photomontage to bring together contrasting images and reflect the workings of the unconscious mind.

Unlike many other photomontage creators of this time, Maar did not use photographs taken from illustrated newspapers or magazines. Instead the images often came from her own work, including both street and landscape photography. This experimentation and obvious construction became a defining feature of Maar’s work.

Anonymous text from “Seven Things to Know: Dora Maar,” on the Tate website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing at second left, Arcade (1934, see below)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Arcade

1934

Photomontage

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Danger

1936

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

29 rue d’Astorg

c. 1936

Photograph, hand-coloured gelatin silver print on paper

294 x 244 mm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

The Simulator

1936

Silver gelatin print printed on a carton

27 x 22.2cm (excluding the margin)

Gift from Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach in 1973

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Maar’s early photomontages look almost as modish and styled as her fashion work. From a shell resting on sand, a dummy hand protrudes, with delicate fingers and painted nails, just like Maar’s own (see top image). In a way, the image could be by one of many photographers of the period – Cecil Beaton, say, or Angus McBean – who politely surrealised their pictures, as if the artistic movement were merely a visual style. Except: there is something ominously self-involved about this hybrid thing. The shell and hand recall Bataille’s obsessions with crustaceans, mollusks, and orphaned or butchered body parts. The hand rhymes with similar ones in the photographs of Claude Cahun, where they sometimes have masturbatory implications. And what are we to make of the storm-lit, gothic sky that looms over this auto-curious object?

The most accomplished examples of Maar’s art are the photomontages of 1935 and 1936. There were already many vaults and arches in her Mont-Saint-Michel pictures; now she took the cloistral galleries of the Orangerie at Versailles, upended them so that they looked like sewers, and populated them with cryptic beings engaged in arcane rituals or dramas. In “The Simulator,” (above) a boy from one of her street photographs is bent backward at an obscene angle; Maar has retouched his eyes so that they roll back in his head toward us, like one of those thrashing hysterics photographed in the nineteenth century. In “29 Rue d’Astorg” (above) – of which Maar made several versions, black-and-white and hand-coloured – a human figure with a curtailed, avian head is seated beneath arches that have been subtly warped in the darkroom.

Brian Dillon. “The Voraciousness and Oddity of Dora Maar’s Pictures,” on The New Yorker website May 21, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Dora Maar also participated in the Surrealists’ group exhibitions, such as the one at Charles Ratton’s Gallery in 1936, wherein her Portrait of Ubu became the “icon of Surrealism,” according to her biographer Mary Ann Caws in her exceptional book Picasso’s Weeping Woman: The Life and Art of Dora Maar (2000). “She captures the mysterious,” Caws wrote, “in a combination of the unresolved and the sharply angled. This frequently creates a sense of ambiguity, even menace.” (p. 20) Caws notes that Dora Maar responded to Louis Aragon’s invocation “for each person there is one image to find that will disturb the whole universe.” Maar’s images managed to “disturb and reveal” with a bit of the macabre mixed in. (p. 71)

Beth Gersh-Nesic. “Picasso’s Weeping Woman as Artist Instead of Muse: Dora Maar’s Retrospective at Centre Pompidou,” on the Bonjour Paris website July 24, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing Maar’s photographs Portrait of Ubu (1936, left), Untitled (Hand-Shell) (1934, top middle) and Danger (1936, bottom right) Photo: Tate (Andrew Dunkley)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Portrait of Ubu

1936

Silver gelatin print

24 x 18cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

In 1936, at the summit of her celebrity as a photographic artist, Dora Maar showed her picture “Portrait of Ubu” in the International Surrealist Exhibition, at the New Burlington Galleries, London. Named after a scatological, ur-Surrealist play by Alfred Jarry, from 1896, the black-and-white photograph shows a ghastly being of indeterminate origin and melancholy aspect. Maar would never say what the clawed, scaly creature was, nor where she had come across it. Her Ubu has elements of Jarry’s porcine, louse-like original, and, with its doleful eye and drooping ears, it also resembles an ass or an elephant. Scholars generally agree that the monster is in fact an armadillo foetus, preserved in a specimen jar. It is also an idea: something like l’informe, the concept Maar’s lover Georges Bataille coined to describe his fellow-Surrealists’ admiration for all things larval and grotesquely about-to-be.

Brian Dillon. “The Voraciousness and Oddity of Dora Maar’s Pictures,” on The New Yorker website May 21, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing her series of portrait photomontages from the mid-1930s (see below)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Double Portrait with Hat

c. 1936-37

Gelatin silver print, montage with handwork on negative

Image: 29.8 x 23.8cm (11 3/4 x 9 3/8 in.)

Gift of David Raymond

The Cleveland Museum of Art

© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

To produce this complex image, Maar sandwiched together two negatives of the same model, one frontal and one profile, scavenged from a magazine assignment on springtime hats, and painted the background and hat (or decomposing halo?) onto the negative. Softening the emulsion, she scraped and lifted it off, techniques that involve destruction and suggest disintegration. The face evokes Picasso’s depictions of female faces, especially his 1938 paintings of weeping women for which Maar was the model. Although the divided face is not Maar’s, it is tempting to interpret it as a reflection of her emotional state at the time, torn between her career and independence and Picasso’s demands and potent personality. frontal and one profile, scavenged from a magazine assignment on springtime hats, and painted the background and hat (or decomposing halo?) onto the negative. Softening the emulsion, she scraped and lifted it off, techniques that involve destruction and suggest disintegration. The face evokes Picasso’s depictions of female faces, especially his 1938 paintings of weeping women for which Maar was the model. Although the divided face is not Maar’s, it is tempting to interpret it as a reflection of her emotional state at the time, torn between her career and independence and Picasso’s demands and potent personality.

Text from The Cleveland Museum of Art website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Profile portrait with glasses and hat

1930-1935

Gelatin silver print

© Dora Maar Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Man looking inside a sidewalk inspection door, London

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Michael Mattis and Judith Hochberg, New York

Courtesy art2art Circulating Exhibitions

© Estate of Dora Maar / DACS 2019, All Rights Reserved

Maar became involved with the surrealists from 1933 and was one of the few artists – and even fewer women – to be included in the surrealists’ exhibitions. She became close to the group because of their shared left-wing politics at a time of social and civil unrest in France.

Maar’s photography and photomontages explore surrealist themes such as eroticism, sleep, the unconscious and the relationship between art and reality. Cropped frames, dramatic angles, unexpected juxtapositions and extreme close-ups are used to create surreal images. Contrasting with the idea of a photograph as a factual record, Maar’s scenes disorientate the viewer and create new worlds altogether.

Anonymous text from “Seven Things to Know: Dora Maar,” on the Tate website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing Maar’s photographs Portrait of Nusch Éluard (1935, left) and Les années vous guettent (The Years are Waiting for You) (1932, right)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Portrait of Nusch Éluard

1935

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Les années vous guettent (The Years are Waiting for You)

1932

Gelatin silver print

© Dora Maar Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

Eileen Agar (British-Argentinian, 1899-1991)

Photograph of Dora Maar and Pablo Picasso on the beach

September 1937

Gelatin silver print

68 x 60 mm

Taken in Juan-les-pins, France

Tate Archive

Presented to Tate Archive by Eileen Agar in 1989 and transferred from the photograph collection in 2012

Eileen Agar (British-Argentinian, 1899-1991)

Photograph of Dora Maar, Nusch Éluard, Pablo Picasso and Paul Éluard on the beach

September 1937

Gelatin silver print

66 x 66 mm

Taken in Juan-les-pins, France

Tate Archive

Presented to Tate Archive by Eileen Agar in 1989 and transferred from the photograph collection in 2012

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Portrait of Picasso, Paris, studio 29, rue d’Astorg

Winter, 1935

Silver gelatin negative on flexible support in cellulose nitrate

12 x 9cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Portrait of Pablo Picasso

1936

Pastel on paper

57.5 x 45cm

Private collection, Yann Panier

Courtesy Galerie Brame and Lorenceau

© Adagp, Paris 2019

© The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973)

Portrait of Dora Maar

1937

Musée National Picasso-Paris

Copyright RMN-Grand Palais, Mathieu Rabeau and Succession Picasso, 2018

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Guernica

May-June, 1937

Gelatin silver print

Musée National Picasso-Paris

Copyright RMN-Grand Palais, Mathieu Rabeau and Succession Picasso, 2018

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Picasso working on “Guernica”

1937

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy VEGAP / Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Picasso working on “Guernica”

1937

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy VEGAP / Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing Maar’s painting The Conversation 1937

Photo: Tate (Andrew Dunkley)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

The Conversation

1937

Oil on canvas

162 x 130cm

Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, Madrid

© FABA © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2019

Photo: Marc Domage

“I must dwell apart in the desert,” the artist and surrealist photographer Dora Maar once said. “I want to create an aura of mystery about my work. People must long to see it.

“I’m still too famous as Picasso’s mistress to be accepted as a painter.”

These words form part of a conversation recorded by Maar’s friend, the art writer James Lord, in his memoir “Picasso and Dora.” During the exchange, the French artist also explains how she rationalised the work of her later years, given that she rarely exhibited and was not in demand. …

With its deliberate focus on their art, the exhibition doesn’t address certain troubling questions about the pair’s unequal personal relationship. In her memoirs, Picasso’s later lover, Françoise Gilot, recounted the brutal bullying to which the artist subjected Maar. Picasso once described the time that Maar and a previous lover, Marie-Thérèse Walter, came to blows in his studio as one of his “choicest memories.”

It’s a subject Maar didn’t shy away from in her art, painting herself alongside Walter in “The Conversation,” one of the works on show at the Tate Modern. Maar is depicted facing away while Walter looks directly at the viewer.

During the aforementioned exchange with James Lord, Maar told the writer that Picasso’s portraits of her were “lies.” But the struggle for recognition she went on to describe is more insightful – that she had to survive in the “desert” to be celebrated on her own terms.

Max Ramsay. “Dora Maar is no longer Picasso’s ‘Weeping Woman’,” on the CNN website 20th November 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973)

Dora Maar seated

1938

Ink, gouache and oil paint on paper on canvas

Support: 689 x 625 mm

Frame: 925 x 685 x 120 mm

Tate

Purchased 1960

In late 1935 or early 1936, Maar met Pablo Picasso. They became lovers soon afterwards. She was at the height of her career, while he was emerging from what he described as ‘the worst time of my life’. He had not sculpted or painted for months.

Their relationship had a huge affect on both their careers. Maar documented the creation of Picasso’s most political work, Guernica 1937, encouraged his political awareness and educated him in photography. Specifically, Maar taught Picasso the cliché verre technique – a complex method combining photography and printmaking.

Picasso painted Maar in numerous portraits, including Weeping Woman 1937. However, Maar explained that she felt this wasn’t a portrait of her. Instead it was a metaphor for the tragedy of the Spanish people. Picasso also encouraged Maar to return to painting. The flattened features and bold outlines of the cubist-style portraits Maar made at this time suggest Picasso’s influence. By 1940 her passport listed her profession as ‘photographer-painter’.

Anonymous text from “Seven Things to Know: Dora Maar,” on the Tate website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing portraits of the artist by numerous artists, some of which you can see below

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Self-portrait with Fan

1930

Gelatin silver print

Emmanuel Sougez (French, 1889-1972)

Dora Maar

Paris, 1934

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar considered the French commercial photographer Emmanuel Sougez (1889-1972) her mentor. Her first commission was a book on Mont-Saint-Michel written by art critic Germain Bazin. She collaborated with the stage-set designer Pierre Kéfer in 1931. From that experience they formed a business partnership, set up at first in his parents’ garden in Neuilly and then moving to their own studio at 9 rue Campagne-Première, lent by the Polish photographer Harry Ossip Meerson (1910-1991), younger brother of the cinema art director Lazare Meerson (1900-1938), who had worked with Kéber at Film Albatros studio in the mid-1920s. Harry Meerson also lent out his darkroom to the Hungarian photographer Brassai (Gyula Halász, 1899-1984), who became Dora Maar’s close friend. Her contact with Brassai brought her into the Surrealist circle.

The Kéfer-Dora Maar studio produced glamorous, innovative images for advertising and portraits, becoming part of the booming industry of commercial photography in glossy magazines. It was a fertile context for Dora Maar’s imagination. Her perspective on the modern women of the 1930s produced models oozing with elegant sensuality. Cool, natural, sometimes athletic, sometimes aristocratic, the Kéfer-Dora Maar female gave off a whiff of eroticise insouciance that emanated from Dora’s own disposition. This conceptualisation of contemporary beauty fed the appetite for luxury and leisure time activities, despite the Great Depression. It was a fantasy for some, a reality for others. During this period of working intensely with Pierre Kéfer, Dora had affairs with the filmmaker Louis Chavance (c. 1932-1933) and the erotically transgressive writer Georges Bataille (late 1933-1934). The Kéfer-Dora Maar studio closed in 1934.

Beth Gersh-Nesic. “Picasso’s Weeping Woman as Artist Instead of Muse: Dora Maar’s Retrospective at Centre Pompidou,” on the Bonjour Paris website July 24, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Portrait of Dora Maar

1936

Gelatin silver print

Rogi André (née Rosa Klein) (French born Hungary, 1900-1970)

Dora Maar, Paris

1941

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 x 4 1/2 in. (16.5 x 11.4cm)

Brassaï (French-Hungarian, 1899-1984)

Dora Maar dans son atelier rue de Savoie (Dora Maar in her workshop rue de Savoie)

1943

Gelatin silver print

© Adagp, Paris 2019 / Estate Brassaï – RMN-Grand Palais

Izis (Israel Bidermanas) (Lithuanian-Jewish, 1911-1980)

Dora Maar

1946

Gelatin silver print

Izis (Israel Bidermanas) (Lithuanian-Jewish, 1911-1980)

Israëlis Bidermanas (17 January 1911 in Marijampolė – 16 May 1980 in Paris), who worked under the name of Izis, was a Lithuanian-Jewish photographer who worked in France and is best known for his photographs of French circuses and of Paris.

Upon the liberation of France at the end of World War II, Izis had a series of portraits of maquisards (rural resistance fighters who operated mainly in southern France) published to considerable acclaim. He returned to Paris where he became friends with French poet Jacques Prévert and other artists. Izis became a major figure in the mid-century French movement of humanist photography – also exemplified by Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Sabine Weiss and Ronis – with “work that often displayed a wistfully poetic image of the city and its people.”

For his first book, Paris des rêves (Paris of Dreams), Izis asked writers and poets to contribute short texts to accompany his photographs, many of which showed Parisians and others apparently asleep or daydreaming. The book, which Izis designed, was a success. Izis joined Paris Match in 1950 and remained with it for twenty years, during which time he could choose his assignments.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Irving Penn (American, 1917-2009)

Dora Maar

France 1948

Gelatin silver print

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Still life

1941

Oil on canvas

© Adagp, Paris, 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Still Life with Jar and Cup

1945

Oil on canvas

45.5 x 50cm

Private Collection

© Adagp, Paris, 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Landscape in Lubéron

1950’s

Private collection of Nancy B. Negley

© Adagp © Brice Toul

Although the late works are not as significant contributions to the history of art as her Surrealist photomontages, they inform our knowledge of this Parisian artist’s accomplishments in general and beg the question: Was Dora Maar’s brilliant career cut short by the typical conflicts facing professional women in the 1930s, and even today? Or was she a victim of Picasso’s psychological abuse, which chipped away at her original confidence? Was she compromised to the point that she only wanted to please the man she loved? According to art historian John Richardson, Dora Maar sacrificed her gifts on the altar of her art god, her idol, Picasso. Based on the early Surrealist photographs we see in her retrospective, one can only wish she hadn’t taken up with Picasso, for it seems she might have achieved far more in her lifetime without him.

Beth Gersh-Nesic. “Picasso’s Weeping Woman as Artist Instead of Muse: Dora Maar’s Retrospective at Centre Pompidou,” on the Bonjour Paris website July 24, 2019 [Online] Cited 23/11/2019

Installation view of the exhibition Dora Maar at Tate Modern, 2019 showing Maar’s paintings and photograms from the 1950s-1980s (see below)

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

c. 1957

Watercolour

© Adagp, Paris 2019

Photo: © Centre Pompidou

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

1980s

Gelatin silver print

23.5 × 17.4cm (9 1/4 × 6 7/8 in.)

© Dora Maar Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Abstract photogram

The 1940s brought a series of traumas. Maar’s father left Paris for Argentina, her mother and best friend Nusch Eluard both died suddenly, her relationship with Picasso ended, and friends went into exile. The difficulty of this time is reflected in some of her work from this period.

Maar was included in many group and solo exhibitions in the 1940s and 1950s. In the mid-1940s she began to spend more time in rural surroundings of Ménerbes in the south of France. Here she regained her confidence as a painter and developed her own style of abstract landscapes. Exhibited across Europe, this work received very positive reviews.

In the 1980s, Maar returned to photography. However, she was no longer interested in photographing life on the street. Instead, Maar was interested in what she could create in the darkroom and experimented with hundreds of photograms (camera-less photographs).

Dora Maar died on July 16, 1997, at 89 years old. Throughout her life she created a vast and varied range of work, much of which was only discovered after her death.

Anonymous text from “Seven Things to Know: Dora Maar,” on the Tate website [Online] Cited 16/11/2019

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

c. 1980

Gelatin silver print

23.5 × 30cm (9 1/4 × 11 13/16 in.)

© Dora Maar Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

1980s

Silver gelatin print

9 x 6cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Untitled

c. 1980

Silver gelatin print

9 x 6cm

Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. Musée national d’art moderne Centre de création industrielle

© Adagp, Paris

Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI / P. Migeat / Dist. RMN-GP

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

United Kingdom

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00 – 18.00

![Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865 Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/unknown-american-decapitated-man-with-head-on-a-platter-c-1865.jpg?w=840)

![Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1848) '[Lane and Peddie as Afghans]' 1843](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/hill-and-adamson-lane-and-peddie-as-afghans-web.jpg?w=840)

![Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931) 'Untitled [Two Male Youths Holding Palm Fronds]' c. 1885 - 1905](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/gloeden-two-male-youths-holding-palm-fronds-web.jpg?w=840)

![Guido Rey (Italian, 1861-1935) '[The Letter]' 1908](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/guido-rey-the-letter-1908-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.