Exhibition dates: 17th February – 5th May 2013

Unknown photographer (American)

He Lost His Head

Nd

Further images from this impressive exhibition devoted to the art of photographic manipulation before the advent of digital imagery from its second stop, at The National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Marcus

.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Edward Steichen (American, 1879-1973)

The Pond – Moonrise

1904

Platinum print with applied colour

image

39.7 x 48.2cm (15 5/8 x 19 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ Permission Estate of Edward Steichen. All rights reserved

Using a painstaking technique of multiple printing, Steichen achieved prints of such painterly seductiveness they have never been equaled. This view of a pond in the woods at Mamaroneck, New York is subtly coloured as Whistler’s Nocturnes, and like them, is a tone poem of twilight, in-distinction, and suggestiveness. Commenting on such pictures in 1910, Charles Caffin wrote in Camera Work: “It is in the penumbra, between the clear visibility of things and their total extinction into darkness, when the concreteness of appearances becomes merged in half-realised, half-baffled vision, that spirit seems to disengage itself from matter to envelop it with a mystery of soul-suggestion.”

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Henry Peach Robinson (British, 1830-1901)

She Never Told Her Love

1857

Albumen silver print from glass negative

18 x 23.2cm (7 1/16 x 9 1/8in.)

Gilman Collection, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke Gift, 2005

Consumed by the passion of unrequited love, a young woman lies suspended in the dark space of her unrealised dreams in Henry Peach Robinson’s illustration of the Shakespearean verse “She never told her love, / But let concealment, like a worm i’ the bud, / Feed on her damask cheek” (Twelfth Night II, iv, 111-13). Although this picture was exhibited by Robinson as a discrete work, it also served as a study for the central figure in his most famous photograph, Fading Away, of 1858.

Purportedly showing a young consumptive surrounded by family in her final moments, Fading Away was hotly debated for years. On the one hand, Robinson was criticised for the presumed indelicacy of having invaded the death chamber at the most private of moments. On the other, those who recognised the scene as having been staged and who understood that Robinson had created the picture through combination printing (a technique that utilised several negatives to create a single printed image) accused him of dishonestly using a medium whose chief virtue was its truthfulness.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Frederick Sommer (American, 1905-1999)

Max Ernst

1946

Gelatin silver print

19.2 x 23.97cm (7 9/16 x 9 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Frederick and Frances Sommer Foundation

Wm. Notman & Son, Montreal, Eugène L’Africain, William Notman

Red Cap Snow Shoe Club, Halifax, Nova Scotia

c. 1888

Collage of albumen prints with applied media

71.1 x 83.8cm (28 x 33 in.)

McCord Museum, Montreal

Notman established his first photography studio in Montreal in 1856 and relentlessly expanded his operations over the next two decades. At its peak, his company had twenty-four branches throughout Canada and New England, making it the most successful photographic enterprise in North America at the time. Notman specialised in composite portraits of large groups, including sporting clubs, trade associations, family gatherings, clergymen, and college graduates, some featuring more than four hundred figures. Each figure in a group was photographed separately in the studio then printed at the proper scale and pasted onto a painted background, as in this portrait of a Nova Scotia snowshoe club. The entire collage was then re-photographed. The final, relatively seamless tableau could then be printed and sold in a variety of sizes and formats.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

The National Gallery of Art presents the first major exhibition devoted to the art of photographic manipulation before the advent of digital imagery. Faking It: Manipulated Photography before Photoshop will be on view in the West Building’s Ground Floor galleries from February 17 through May 5, 2013, following its debut at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (from October 11, 2012, through January 27, 2013). In June it travels to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

“Following in its tradition of exhibiting and collecting the finest examples of photography, the Gallery is pleased to present some 200 photographs from the 1840s through the 1980s demonstrating the medium’s complicated relationship to truth in representation,” said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. “We are grateful to the many lenders, both public and private, who have generously shared works from their collections – especially the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the largest lender and the organiser of this fascinating exhibition.”

The Exhibition

This is the first major exhibition devoted to the history of manipulated photography before the digital age. While the widespread use of Adobe® Photoshop® software has brought about an increased awareness of the degree to which photographs can be doctored, photographers – including such major artists as Gustave Le Gray, Edward Steichen, Weegee, and Richard Avedon – have been fabricating, modifying, and otherwise manipulating camera images since the medium was first invented. This exhibition demonstrates that today’s digitally manipulated images are part of a continuum that extends back to photography’s first decades. Through visually captivating pictures created in the service of art, politics, news, entertainment, and commerce, Faking It not only traces the medium’s complex and changing relationship to visual truth, but also significantly revises our understanding of photographic history.

Organised thematically, the exhibition begins with some of the earliest instances of photographic manipulation – those attempting to compensate for the new medium’s technical limitations. In the 19th century, many photographers hand tinted portraits to make them appear more vivid and lifelike. Others composed large group portraits by photographing individuals separately in the studio and creating a collage by pasting them onto painted backgrounds depicting outdoor scenes. As the art and craft of photography grew increasingly sophisticated, photographers devised a staggering array of techniques with which to manipulate their images, including combination printing, photomontage, overpainting, ink and airbrush retouching, sandwiched negatives, multiple exposures, and other darkroom magic.

The exhibition presents a superb selection of manually altered photographs created under the mantle of art, including 19th-century genre scenes composed of multiple negatives, stunning Pictorialist landscapes from the turn of the 19th century, and the pre-digital dreamscapes of surrealist photographers in the 1920s and 1930s. A section of doctored images made for political or ideological ends includes faked composite photographs of the 1871 Paris Commune massacres, anti-Nazi photomontages by John Heartfield, and falsified images from Stalin-era Soviet Russia. The show also explores popular uses of photographic manipulation such as spirit photography, tall-tale and fantasy postcards, advertising and fashion spreads, and doctored news images.

The final section features the work of contemporary artists – including Duane Michals, Jerry Uelsmann, and Yves Klein – who have reclaimed earlier techniques of image manipulation to creatively question photography’s presumed objectivity. By tracing the history of photographic manipulation from the 1840s to the present, Faking It vividly demonstrates that photography is – and always has been – a medium of fabricated truths and artful lies.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art website

Weegee (Arthur Felig) (American born Hungary, 1899-1968)

Times Square, New York

1952-1959

Gelatin silver print

20.3 x 17.8cm (8 x 7 in.)

© International Center of Photography, Bequest of Wilma Wilcox, 1993

Famous for his gritty tabloid crime photographs, Weegee devoted the last twenty years of his life to what he called his “creative work.” He experimented prolifically with distorting lenses and comparable darkroom techniques, producing photo caricatures of politicians and Hollywood celebrities, novel variations on the man-in-the-bottle motif, and uncanny doublings and reflections, such as this striking image, which he described as “Times Square under 10 feet of water on a sunny afternoon.”

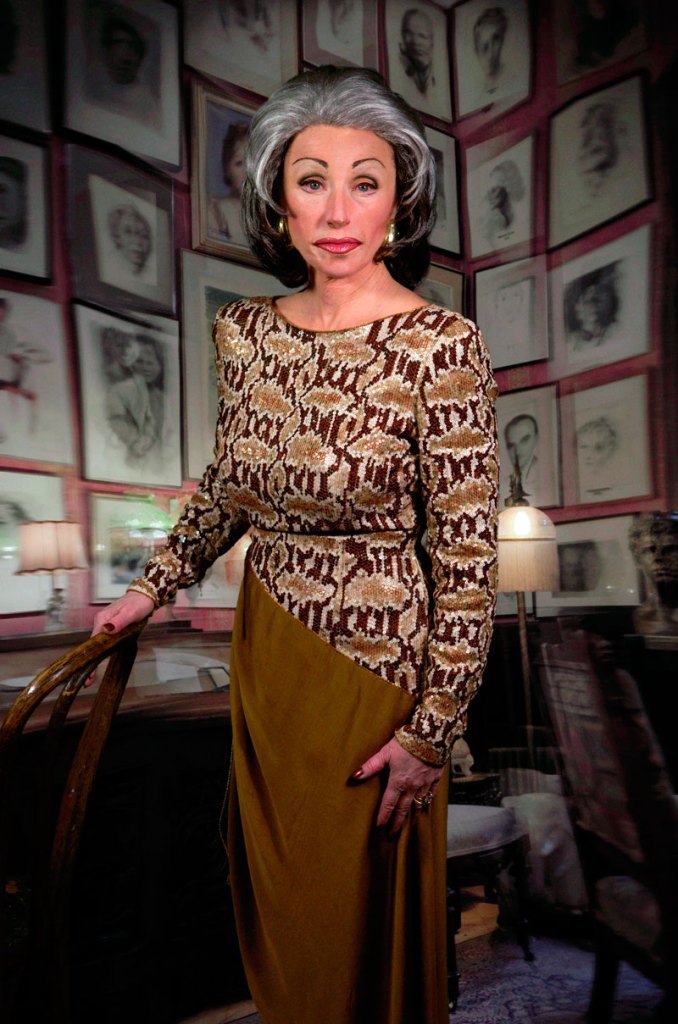

Kathy Grove (American, b. 1948)

The Other Series (After Kertész)

1989-1990

Gelatin silver print

19.7 x 15.2cm (7 3/4 x 6 in.)

Purchase, Charina Foundation Inc. Gift, 2010

© Kathy Grove

In the late 1980s Grove, an artist who supports herself as a professional photo retoucher, began seamlessly altering images of famous works of art, using bleach, dyes, and airbrush to remove the female figure from each image and leaving the rest of the scene intact. Her cunning excisions mimic the process by which art historians, echoing the culture at large, have erased the achievements of actual women while enshrining Woman as a blank screen upon which the ideas and desires of both artist and viewer are projected. If photographs are presumed to represent the truth, Grove’s pictures remind us to ask: Whose truth?

Unknown (American)

[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]

c. 1865

Tintype with applied colour

8.4 x 6cm (3 5/16 x 2 3/8 in.)

© International Center of Photography, Gift of Steven Kasher and Susan Spungen Kasher, 2008

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

Cape Horn, Columbia River, Oregon

1867, printed 1880-1890

Albumen silver print from glass negatives

52.3 x 40.4cm (20 9/16 x 15 7/8 in.)

© George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester

Watkins, the consummate photographer of the American West, combined a virtuoso mastery of the difficult wet plate negative process with a rigorous sense of pictorial structure. For large-format landscape work such as Watkins produced along the Columbia River in Oregon, the physical demands were great. Since there was as yet no practical means of enlarging, Watkins’s glass negatives had to be as large as he wished the prints to be, and his camera large enough to accommodate them. Furthermore, the glass negatives had to be coated, exposed, and developed while the collodion remained tacky, requiring the photographer to transport a traveling darkroom as he explored the rugged virgin terrain of the American West. The crystalline clarity of Watkins’s remarkable “mammoth” prints is unmatched in the work of any of his contemporaries and is approached by few artists working today. (Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website). Here the clouds have been printed in (compare to the work on the Metropolitan Museum of Art website)

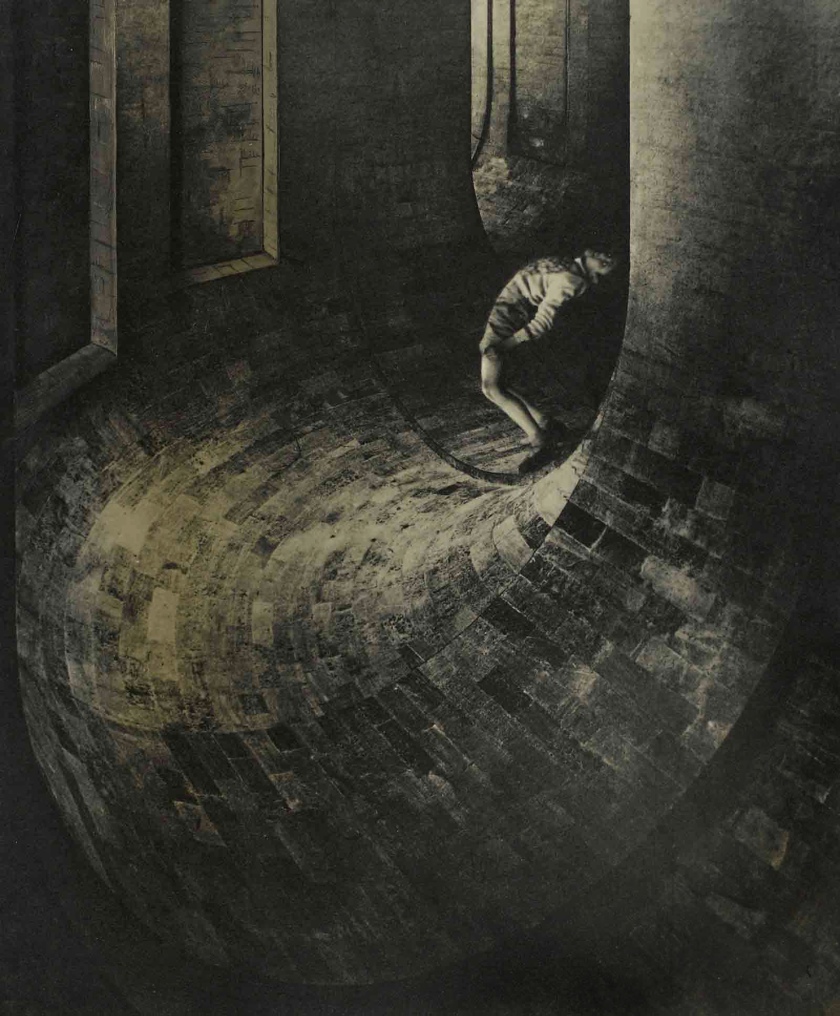

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Le simulateur

1936

Gelatin silver print

29.2 x 22.9cm (11 1/2 x 9 in.)

Collection of The Sack Photographic Trust for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Maar’s haunting photomontages of the mid-1930s evoke a mood of oneiric ambiguity. Here, the world is turned literally upside-down: a boy bends sharply backward, echoing the curve of the vaulted ceiling on which he stands. On the print, Maar scratched out the figure’s eyes, exploiting Surrealism’s strong association of blindness with inner sight.

Albert Sands Southworth (American, 1811-1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (American, 1808-1901)

Seated man with Brattle Street Church seen through window

1850s

Daguerreotype

21.6 x 16.5cm (8 1/2 x 6 1/2 in.)

The Isenburg Collection at AMC Toronto

J.C. Higgins and Son (American)

Man in bottle

c. 1888

Albumen print

13.5 x 10cm (5 5/16 x 3 15/16 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Susan and Thomas Dunn Gift, 2011

Jerry N. Uelsmann (American, b. 1934)

Untitled

1976

Gelatin silver print

49.3 x 36cm (19 7/16 x 14 3/16 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, David Hunter McAlpin Fund, 1981

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/ © Jerry N. Uelsmann

Unknown Photographer (German)

Ein kräftiger Zusammenstoss (A Powerfull Collision)

1914

Gelatin silver print

8.7 x 13.7cm (3 7/16 x 5 3/8 in.)

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Twentieth-Century Photography Fund, 2010

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865 Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/unknown-american-decapitated-man-with-head-on-a-platter-c-1865.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.