Exhibition dates: 13th July – 30th September 2018

Curators: This exhibition is co-curated by David Kiehl, Curator Emeritus, and David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection.

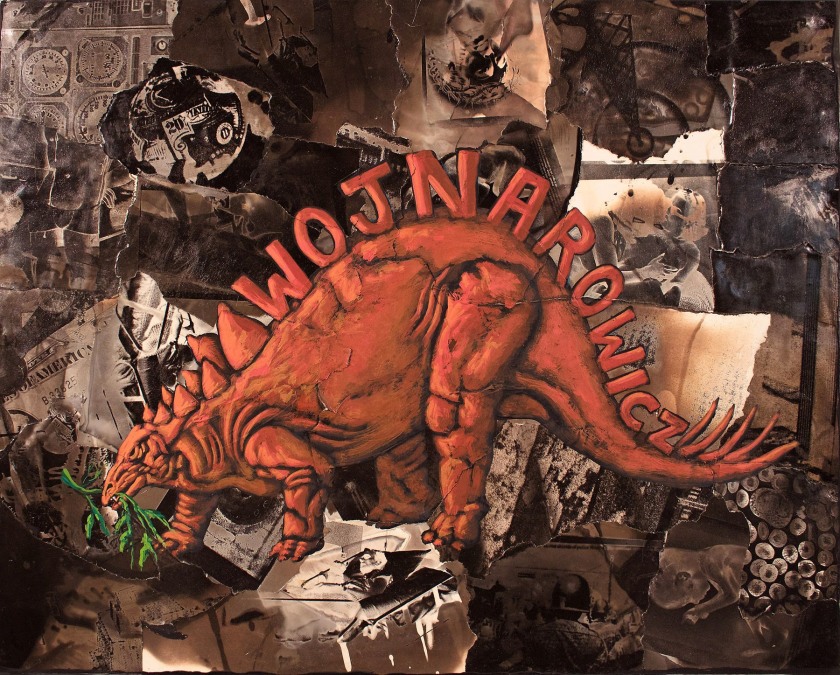

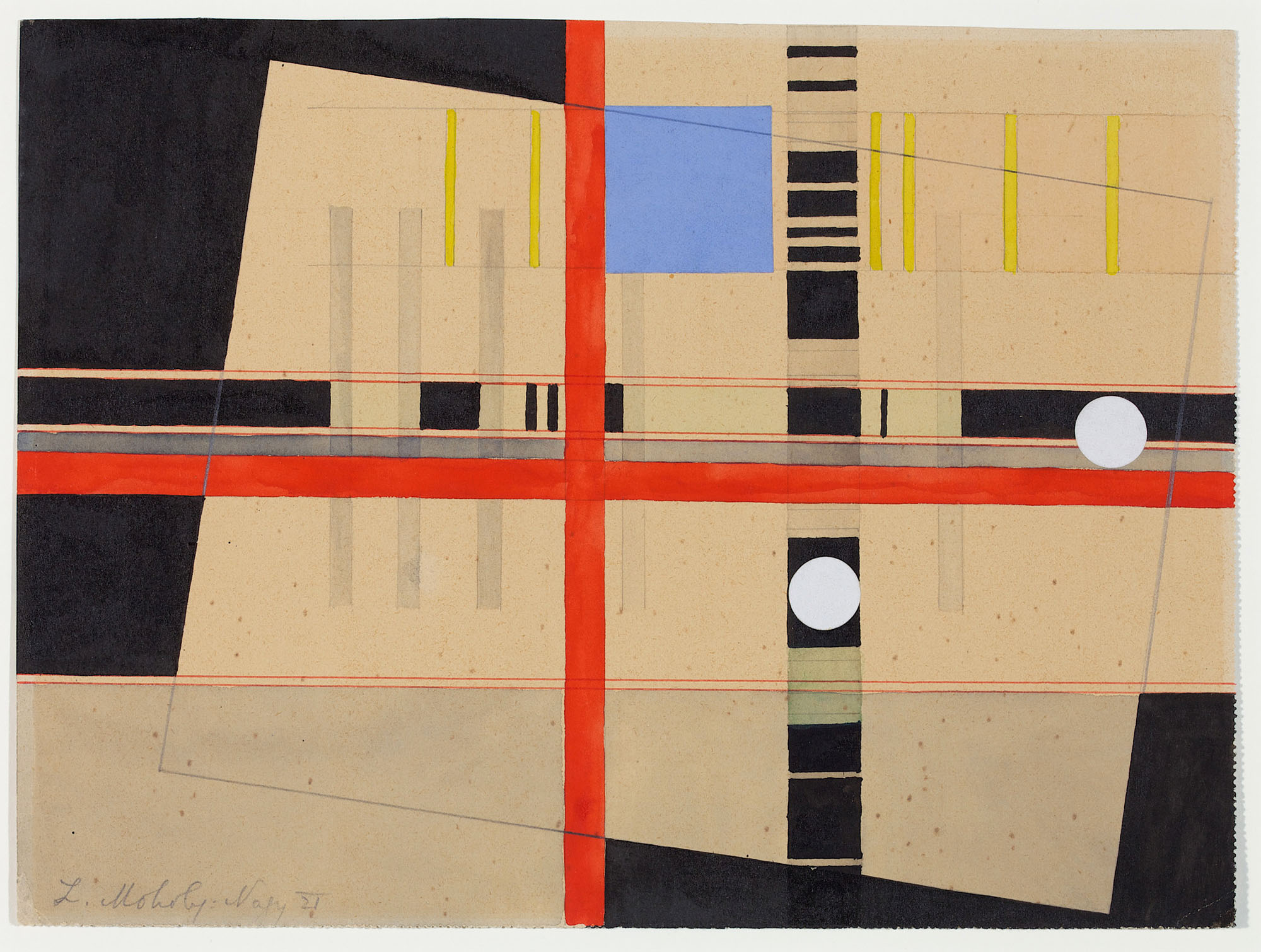

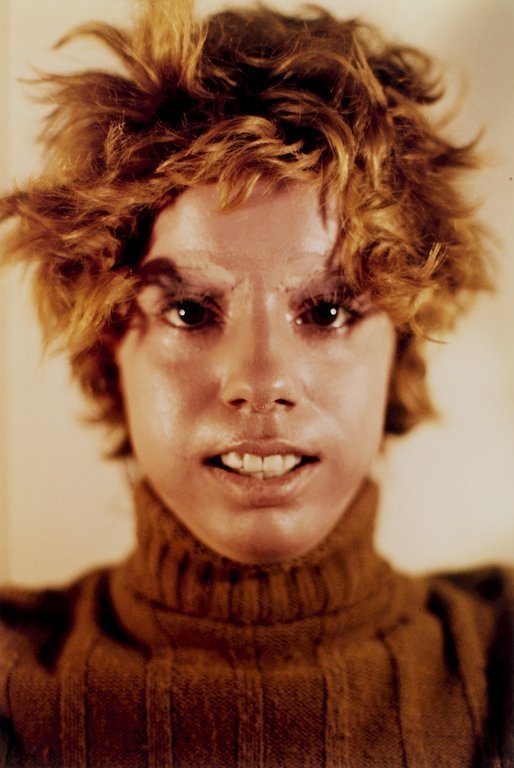

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992) with Tom Warren

Self-Portrait of David Wojnarowicz

1983-1984

Acrylic and collaged paper on gelatin silver print

60 × 40 in. (152.4 × 101.6cm)

Collection of Brooke Garber Neidich and Daniel Neidich

Photo: Ron Amstutz

Man on fire

… and two important ones I forgot: earth and spirit!

What an unforgettable, socially aware artist.

His work, and the concepts it investigates, have lost none of their relevance. With the rise of the right, Trump, fake news, discrimination and the ongoing bigotry of religion his thoughts and ideas, his writing, and his imagination are as critical as ever to understanding the dynamics of power and oppression. As Olivia Laing observes, ” …the forces he spoke out against are as lively and malevolent as ever.”

Remember: silence is the voice of complicity.

Although in his lifetime he never achieved the grace he desired, through his art the grace of his spirit lives on. Love and respect.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Whitney Museum of American Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

This exhibition will be the first major, monographic presentation of the work of David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) in over a decade. Wojnarowicz came to prominence in the East Village art world of the 1980s, actively embracing all media and forging an expansive range of work both fiercely political and highly personal. Although largely self-taught, he worked as an artist and writer to meld a sophisticated combination of found and discarded materials with an uncanny understanding of literary influences. First displayed in raw storefront galleries, his work achieved national prominence at the same moment that the AIDS epidemic was cutting down a generation of artists, himself included. This presentation will draw upon recently-available scholarly resources and the Whitney’s extensive holdings of Wojnarowicz’s work.

“I want to throw up because we’re supposed to quietly and politely make house in this killing machine called America and pay taxes to support our own slow murder, and I’m amazed that we’re not running amok in the streets and that we can still be capable of gestures of loving after lifetimes of all this.”

“It is exhausting, living in a population where people don’t speak up if what they witness doesn’t directly threaten them…”

“When I was told that I’d contracted this virus it didn’t take me long to realise that I’d contracted a diseased society, as well.”

“I’ve always painted what I see, and what I experience, and what I perceive, so it naturally has a place in the work. I think not all the work I do is about AIDS or deals with AIDS, but I think the threads of it are in the other work as well.”

“I think what I really fear about death is the silencing of my voice… I feel this incredible pressure to leave something of myself behind.”

“To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

“I’m beginning to believe that one of the last frontiers for radical gesture is the imagination…”

“Smell the flowers while you can.”

“All I want is some kind of grace.”

David Wojnarowicz

The image of Rimbaud as a loner bad boy – shooting up, masturbating, prowling Times Square – embodied Wojnarowicz’s early view of what an artist should be: a guerrilla infiltrator, disrupter of what he called the “pre-invented world” that we’re all told is normal, a world of fake borders, gated hierarchies and controlling insider laws. …

A salon-like central gallery is lined with large-scale pictures from the mid-1980s that are basically the equivalent of the history paintings produced by Nicolas Poussin and Thomas Cole, big-thinking panoramas that addressed contemporary politics in a classical language of mythology and landscape. …

Wojnarowicz unabashedly turned, as he said, “the private into something public.” He collapsed political, cultural and personal history in a way that he hadn’t before. He took his outsider citizenship as a subject and weaponized it. The move was strategically effective: It got a lot of attention, including a barrage of right-wing attacks that have persisted into the near-present.”

Holland Cotter. “He Spoke Out During the AIDS Crisis. See Why His Art Still Matters,” on the New York Times website, July 12, 2018 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

“Wojnarowicz, the writer, painter, photographer, poet, printmaker and activist, was gay himself, and in his work addressed same-sex desire, the Aids crisis, the persecution of sexual minorities and the Reagan administration’s refusal to acknowledge their existence. But his work is really about America, a place he had described in his 1991 essay collection ‘Close to the Knives’ as an “illusion”, a “killing machine”, a “tribal nation of zombies … slowly dying beyond our grasp”.

Jake Nevins. “David Wojnarowicz: remembering the work of a trailblazing artist,” on The Guardian website 13 July 2018 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

“Long before the word intersectionality was in common currency, Wojnarowicz was alert to people whose experience was erased by what he called “the pre‑invented world” or “the one-tribe nation”. Politicised by his own sexuality, by the violence and deprivation he had been subjected to, he developed a deep empathy with others, a passionate investment in diversity.”

Olivia Laing. “David Wojnarowicz: still fighting prejudice 24 years after his death,” on The Guardian website 13 May 2016 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

“AIDS is not history. The AIDS crisis did not die with David Wojnarowicz,” reads a mission statement displayed by protesters at the museum. “We are here tonight to honor David’s art and activism by explicitly connecting them to the present day. When we talk about HIV/AIDS without acknowledging that there’s still an epidemic – including in the United States – the crisis goes quietly on and people continue to die… The danger is when you look right now at young people, they think AIDS is over with. They don’t think anyone is living with HIV. They go to the museum and they see it as art – they don’t see AIDS as an urgent problem…”

Sarah Cascone. “‘AIDS Is Not History’: ACT UP Members Protest the Whitney Museum’s David Wojnarowicz Show, Claiming It Ignores an Ongoing Crisis,” on Art News website 30 July 2018 [Online] Cited 22/02/2022

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Buffalo)

1988-1989

Marion Scemama collection

Courtesy of Estate of David Wojnarowicz and Gracie Mansion Fine Art

© The Estate of David Wojnarowicz

David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Buffalo) is one of the artist’s best-known works and perhaps one of the most haunting artistic responses to the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. The work depicts a herd of buffalo falling off a cliff to their deaths. The artist provides very little context for why and how the creatures got there. The work is in reality, a photograph of a diorama from a museum in Washington, DC depicting an early Native American hunting technique. Through appropriation of this graphic image, the artist evokes feelings of doom and hopelessness, making the work extremely powerful and provocative. Made in the wake of the artist’s HIV-positive diagnosis, Wojnarowicz’s image draws a parallel between the AIDS crisis and the mass slaughter of buffalo in America in the nineteenth century, reminding viewers of the neglect and marginalisation that characterised the politics of HIV/AIDS at the time.

Anonymous text from the Paddle 8 website Nd [Online] Cited 26/09/2022. No longer available online

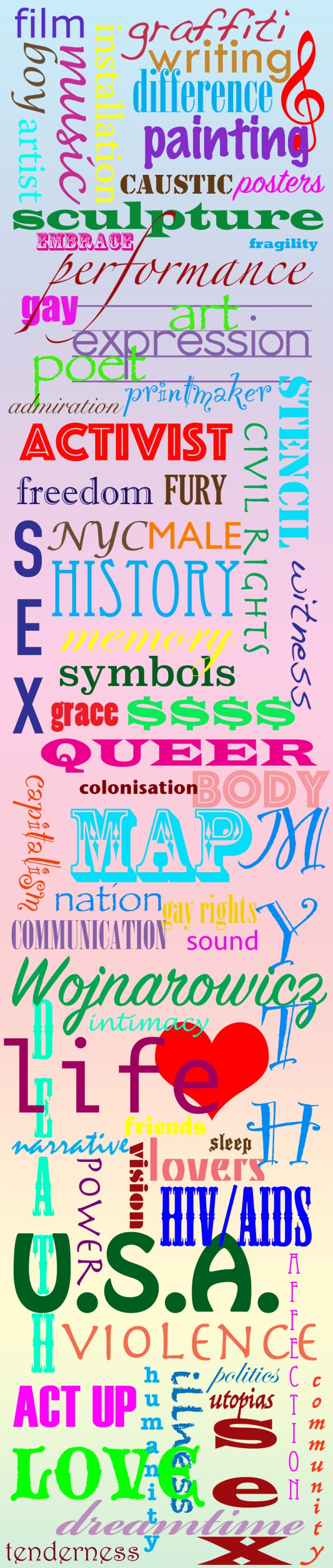

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements – graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting – made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures – a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics – he varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the prevailing culture.

Wojnarowicz saw the outsider as his true subject. Queer and later diagnosed as HIV-positive, he became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction. Wojnarowicz’s work documents and illuminates a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explore American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence. Like theirs, his work deals directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss. Wojnarowicz, who was thirty-seven when he died from AIDS-related complications, wrote: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

Text from the Whitney Museum of American Art

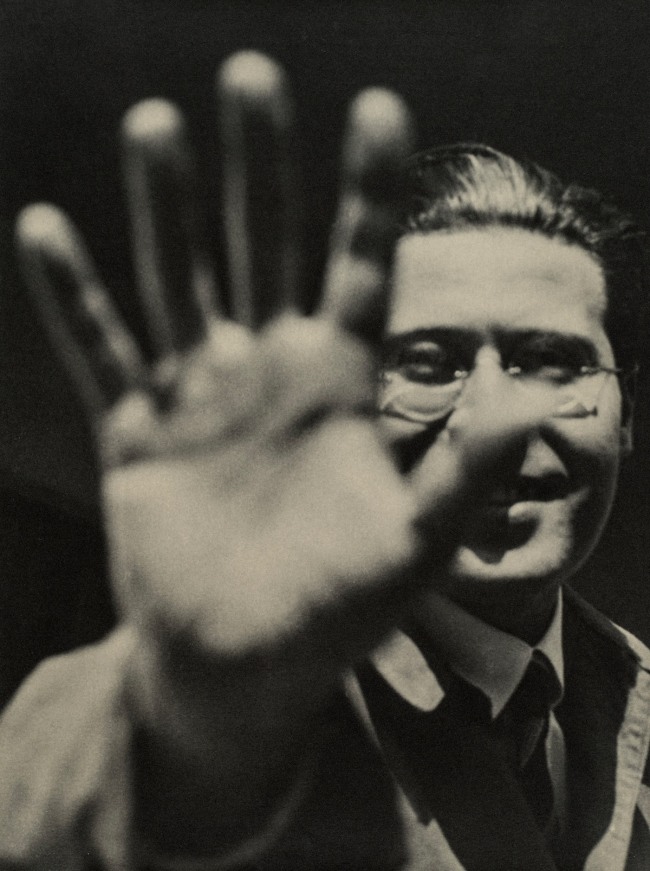

David Wojnarowicz in 1988

David Wojnarowicz (History Keeps Me Awake at Night) Whitney Museum of American Art

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements – graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting – made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. He saw the outsider as his true subject. Queer and later diagnosed as HIV-positive, he became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction.

Whitney Museum of American Art

This summer, the most complete presentation to date of the work of artist, writer, and activist David Wojnarowicz will be on view in a full-scale retrospective organised by the Whitney Museum of American Art. David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is the first major re-evaluation since 1999 of one of the most fervent and essential voices of his generation.

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, performance, and activism. Joining a lineage of iconoclasts, Wojnarowicz (pronounced Voyna-ROW-vich) saw the outsider as his true subject. His mature period began with a series of photographs and collages that honoured – and placed himself among – consummate countercultural figures like Arthur Rimbaud, William Burroughs, and Jean Genet. Even as he became well-known in the East Village art scene for his mythological paintings, Wojnarowicz remained committed to writing personal essays. Queer and HIV-positive, Wojnarowicz became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS at a time when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers – disproportionately gay men – were dying from the disease and from government inaction.

Scott Rothkopf, Deputy Director for Programs and Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator, remarked, “Since his death more than twenty-five years ago, David Wojnarowicz has become an almost mythic figure, haunting, inspiring, and calling to arms subsequent generations through his inseparable artistic and political examples. This retrospective will enable so many to confront for the first time, or anew, the groundbreaking multidisciplinary body of work on which his legacy actually stands.”

David Breslin noted, “With rage and beauty, David Wojnarowicz made art that questioned power, particularly why some lives are visible and others are hidden. Wojnarowicz wrote, ‘To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.’ Present throughout his work and this exhibition is the will to show the desires, dreams, and politics of outsiders – like him – queer, economically marginalised, sick, vulnerable, and vibrantly idiosyncratic.”

Largely self-taught, Wojnarowicz came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by great creative energy and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements – graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, neo-expressionist painting – made New York a laboratory for innovation. Unlike many artists, Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures, a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics, Wojnarowicz varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the culture.

Wojnarowicz was a poet before he was a visual artist. His mature period began with Rimbaud in New York (1978-1979), in which he photographed friends wearing a mask of the nineteenth-century French poet’s face and posing throughout New York City. He became, in the 1980s, a figure in the East Village art scene, showing his paintings, photographs, and installations at galleries like Civilian Warfare, Gracie Mansion, and P.P.O.W. During a time when AIDS was ravaging the artistic community of New York, Wojnarowicz emerged as a powerful activist and advocate for the rights of people with AIDS and the queer community, becoming deeply entangled in the culture wars.

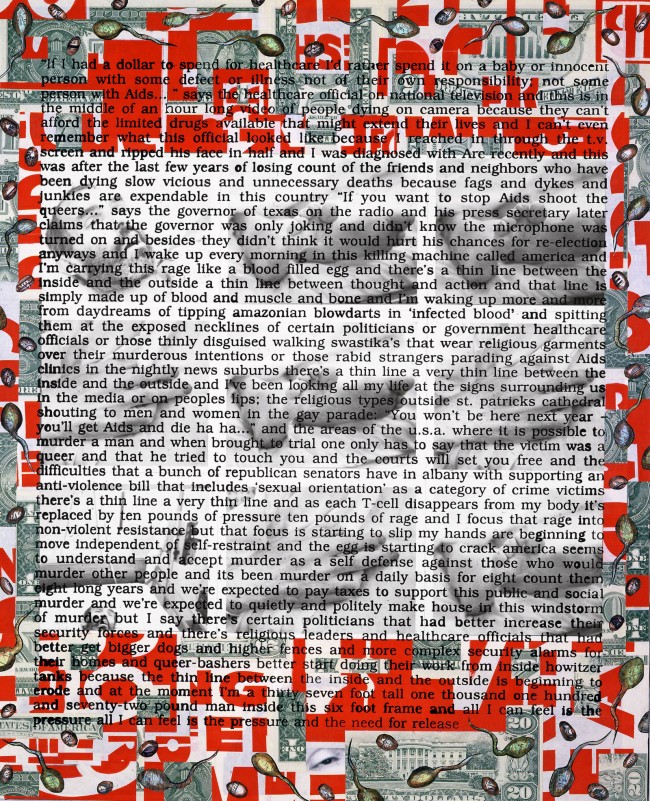

His essay for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (curated by Nan Goldin at Artists Space in 1989-1990) came under fire for its vitriolic attack on politicians and leaders who were preventing AIDS treatment and awareness. The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) threatened to defund the exhibition, and Wojnarowicz fought against this and for the first amendment rights of artists.

The Whitney retrospective will include an excerpt of footage shot by Phil Zwickler, a filmmaker, fellow activist, and friend of Wojnarowicz who also died of AIDS, in which Wojnarowicz is seen preparing to talk to the press in the wake of the NEA controversy. Important text-photo works from this period, which incorporated writings from Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration, a collection of essays published a year prior to Wojnarowicz’s death, will also be in the Whitney show, including When I Put My Hands on Your Body (1990), Untitled (One day this kid…) (1989), and the iconic photograph Untitled (Falling Buffalo) (1988-1989).

The Whitney exhibition begins with the artist’s early experiments in collage and photography that were contemporaneous with the Rimbaud in New York series and features three of Wojnarowicz’s original journals that he kept during the time he was living in Paris and conceiving the Rimbaud photographs. Also on view will be the original Rimbaud mask the artist had his friends wear to pose for the photographs.

Wojnarowicz’s early stencil works first appeared on the streets of downtown Manhattan. These show him developing an iconographic language that he also used on the walls of the abandoned piers on the Hudson River and would figure in the more complex studio paintings that characterise his art later in the decade. An important group of spray and collage paintings in 1982 focus on an image of the artist Peter Hujar, his great friend and mentor. A group of Hujar’s photographs of Wojnarowicz will be shown in conversation with these paintings. By the mid-1980s, Wojnarowicz’s paintings combined mythological subject matter with elements that explored urbanism, technology, religion, and industry.

His masterful suite of four paintings from 1987, each named for one of the four elements, will be shown in their own gallery both to emphasise the centrality of painting and image-making during this moment and to mark the beginning of a period of mourning, rage, and action (both aesthetic and activist) marked by the death of Hujar and others to AIDS-related complications. His never-completed film, Fire in My Belly, will be shown among other unfinished film work that later would become the source for much of his photographic work from 1988-89: the Ant Series, The Weight of the World, and Spirituality (for Paul Thek). A gallery will be devoted to a recording of Wojnarowicz reading from his own writings in 1992 at The Drawing Center in Soho.

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). Clockwise, from top left: Andreas Sterzing, Something Possible Everywhere: Pier 34, NYC, 1983-1984; David Wojnarowicz, Fuck You Faggot Fucker, 1984; Peter Hujar, Untitled (Pier), 1983; Peter Hujar, Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall (by David Wojnarowicz), 1983; David Wojnarowicz, Untitled, 1982; David Wojnarowicz, Untitled (Slam Click), 1983

Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018)

Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018)

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 13-September 30, 2018). From left to right: He Kept Following Me, 1990; I Feel A Vague Nausea, 1990; Americans Can’t Deal with Death, 1990; We Are Born into a Preinvented Existence, 1990.

Photograph by Ron Amstutz

About the Artist

After hitchhiking across the U.S. and living for several months in San Francisco, and then in Paris, David Wojnarowicz settled in New York in 1978 and soon after began to exhibit his work in East Village galleries. He was included in the 1985 and 1991 Whitney Biennials, and was shown in numerous museum and gallery exhibitions throughout the United States and Europe. Previous exhibitions to focus on Wojnarowicz include “Tongues of Flame” at the University Galleries of Illinois State University (1990) and “Fever: The Art of David Wojnarowicz” at the New Museum (1999). Wojnarowicz was the author of a number of books, including Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991). His artwork is in numerous private and public collections including the Whitney Museum of American Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Art Institute of Chicago; the Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles; and Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain.

Press release from the Whitney Museum of American Art

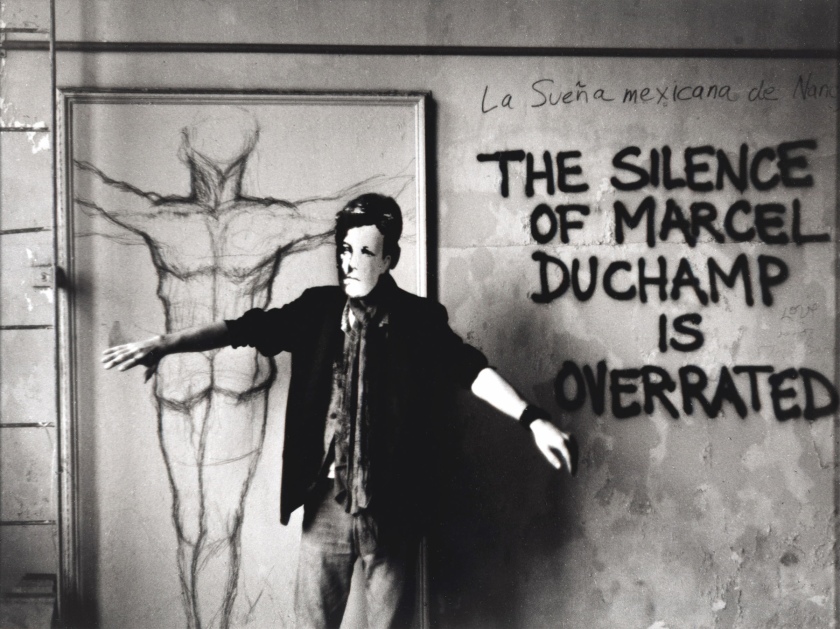

Gallery 1

Wojnarowicz, who aspired to be a writer in the 1970s, immersed himself in the work of William S. Burroughs and Jean Genet – two collages here feature them – but he felt a particular kinship to the iconoclastic nineteenth-century French poet Arthur Rimbaud. In the summer of 1979, just back from a stay in Paris with his sister, the twenty-four-year-old Wojnarowicz photographed three of his friends roaming the streets of New York wearing life-size masks of Rimbaud. Using a borrowed camera, Wojnarowicz staged the images in places important to his own story: the subway, Times Square, Coney Island, all-night diners, the Hudson River piers, and the loading docks in the Meatpacking District, just steps away from the Whitney Museum. Born one hundred years, almost to the month, before Wojnarowicz, Rimbaud rejected established categories and wanted to create new and sensuous ways to participate in the world. He, like Wojnarowicz, was the forsaken son of a sailor father, made his queerness a subject of his work, and knowingly acknowledged his status as an outsider (“Je est un autre” – “I is an other” – is perhaps Rimbaud’s most famous formulation).

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Arthur Rimbaud in New York

1978-1979 (printed 1990)

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (On Subway)

1978-1979 (printed 1990)

Gelatin silver print

8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4cm)

Collection of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz

Courtesy P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Arthur Rimbaud in New York (Duchamp, Pier)

1978-1979 (printed 2004)

Gelatin silver print

10 × 8 in. (25.4 × 20.3cm)

Collection of Philip E. Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W., New York

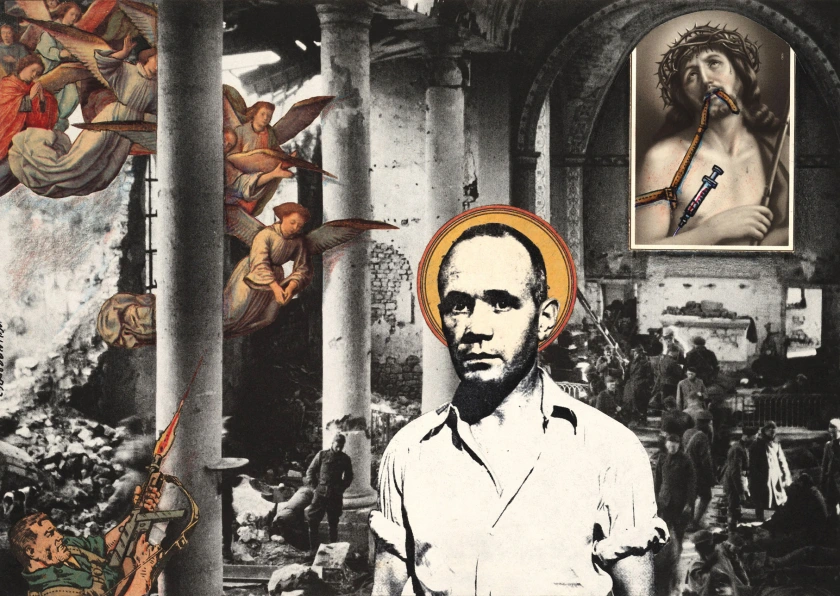

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Genet after Brassaï)

1979

Collage of offset-lithographs and coloured pencil

12 × 15 in. (30.5 × 38.1cm)

Private collection

Photo: Carson Zullinger

At the same time as he conceived the Rimbaud series, Wojnarowicz created homages to other personal heroes, including Jean Genet (1910-1986), the French novelist, poet, and political activist. Genet resonated with Wojnarowicz for his erotic vision of the universe, his embrace of the outsider, and his frank writing on gay sex. For Untitled (Genet after Brassaï), Wojnarowicz transforms the iconoclast writer into a saint; in the background, a Christ figure appears to be shooting up with a syringe. When later criticised by religious conservatives, Wojnarowicz explained that he saw drug addiction as a contemporary struggle that an empathetic Christ would identify with and forgive.

Gallery 2

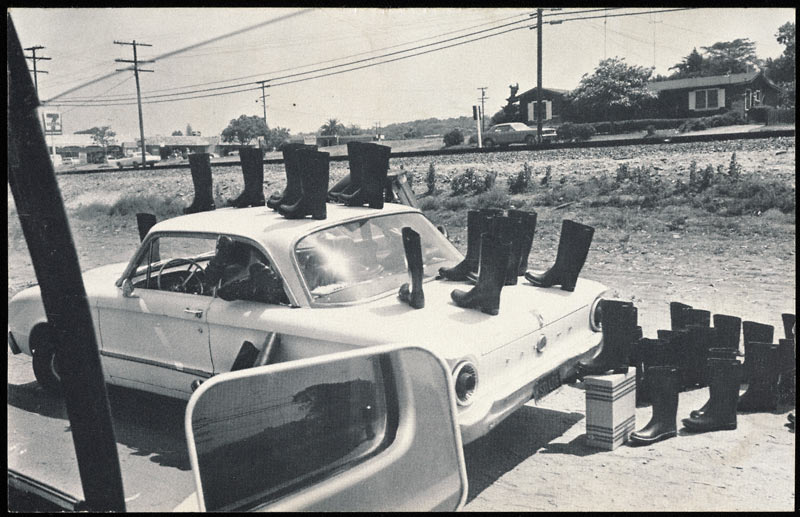

In the early 1980s Wojnarowicz had no real income. He scavenged materials like supermarket posters and trashcan lids as well as cheap printed materials available in his Lower East Side neighbourhood. Incorporating them in his art, Wojnarowicz found radical possibilities in these discarded, forgotten artefacts and in the city itself. He embraced the abandoned piers on the Hudson River, particularly Pier 34 just off Canal Street, for the freedom they offered. He cruised for sex there, and he also wrote and made art on site. He appreciated their proximity to nature and the solitude he could find there.

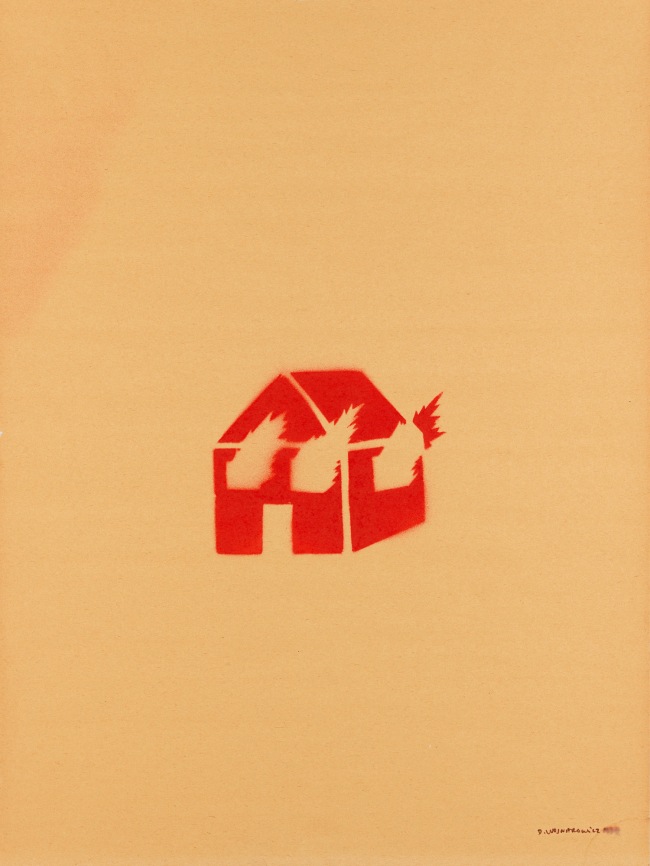

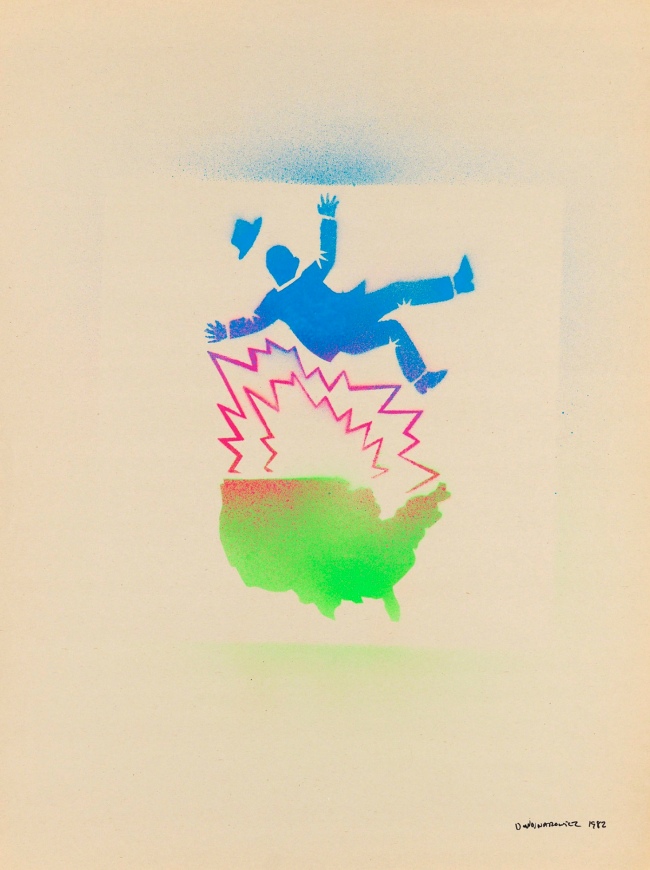

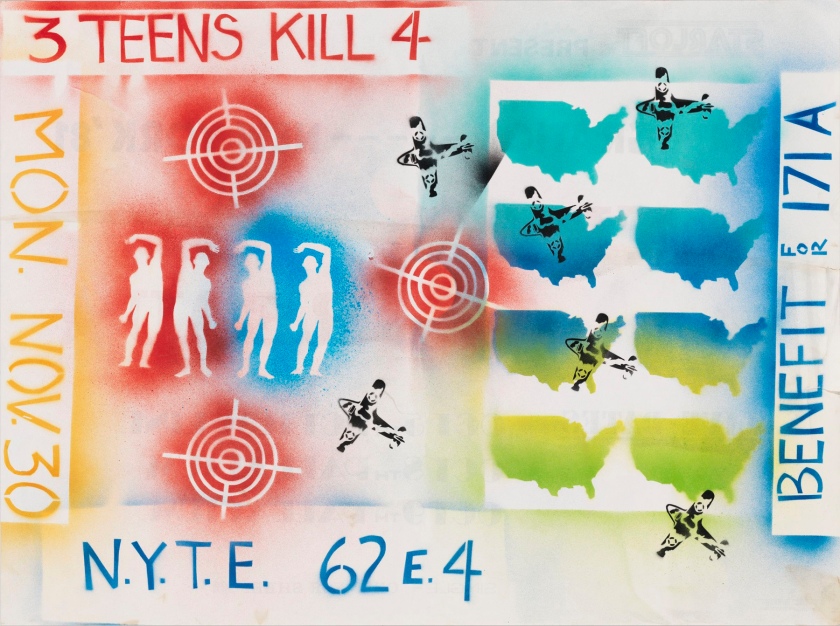

Wojnarowicz began using stencils out of necessity. He was a member of the band, 3 Teens Kill 4, whose album, No Motive, can be played on the website. He produced posters for their shows, and to prevent their removal started making templates to spray-paint his designs on buildings, walls, and sidewalks. These images – the burning house, a falling man, a map outline of the continental United States, a dive-bombing aircraft, a dancing figure – became signature elements in his visual vocabulary, creating an iconography of crisis and vulnerability. Wojnarowicz frequently railed against what he called the “pre-invented world”: a world colonised and corporatised to such an extent that it seems to foreclose any alternatives. For him, using found objects, working at the abandoned piers for an audience of friends and strangers, and creating a language of his own were ways to shatter the illusion of the pre-invented world and make his own reality.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Burning House)

1982

Spray paint on paper

23 15/16 × 17 7/8 in. (60.8 × 45.4cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Print Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Falling man and map of the U.S.A.)

1982

Spray paint on paper

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase with funds from the Print Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

“3 Teens Kill 4 – No Motive Poster”

1982-1983

Spray paint on paper

30 × 40 1/8 in. (76.2 × 101.9cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase with funds from the Print Committee

© The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

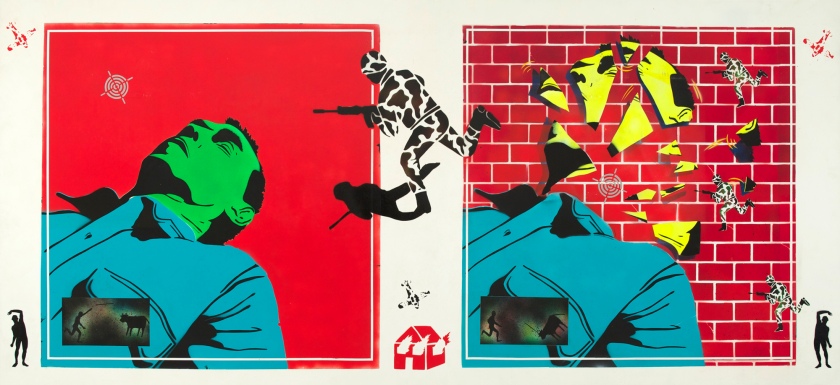

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Diptych II

1982

Spray paint with acrylic on composition board

48 × 96 in. (121.9 × 243.8cm)

Collection of Raymond J. Learsy

Image courtesy Raymond J. Learsy

Photo: Brian Wilcox

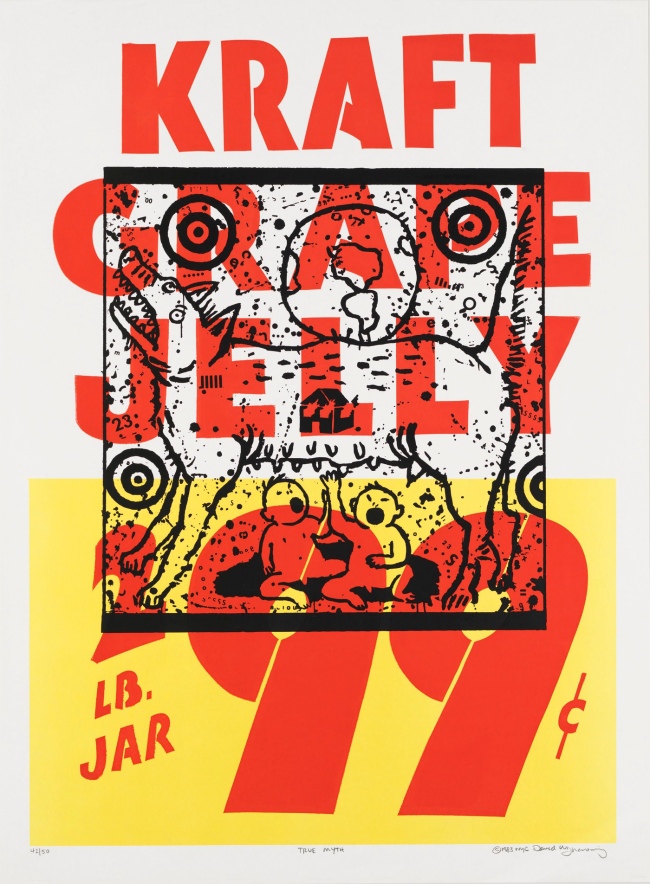

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

True Myth (Kraft Grape Jelly)

1983

Screenprint, edition 42/50

31 1/4 × 22 1/2 in. (79.4 × 57.2cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase with funds from the Print Committee

© The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Jean Genet Masturbating in Metteray Prison (London Broil)

1983

Screenprint on supermarket poster

34 × 25 in. (86.4 × 63.5cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Print Committee

Photo: Mark-Woods.com

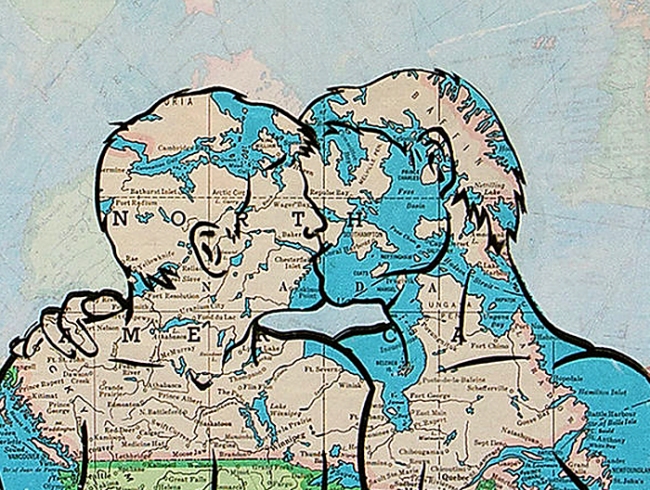

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Fuck You Faggot Fucker

1984

Four black-and-white photographs, acrylic, and collaged paper on Masonite

48 × 48 in. (121.9 × 121.9cm)

Collection of Barry Blinderman

Image courtesy Barry Blinderman, Normal, Illinois

Photo: Jason Judd

This work was one of Wojnarowicz’s first to directly tackle homophobia and gay bashing and to embrace same-sex love. Its title comes from a scrap of paper containing a homophobic slur that Wojnarowicz found and affixed below the central image of two men kissing. Made with one of his stencils, these anonymous men are archetypes, stand-ins for a multitude of personal stories. Using photographs taken at the piers and in an abandoned building on Avenue B, Wojnarowicz also includes himself and his friends John Hall and Brian Butterick in this constellation. Maps like those in the background here often appear in Wojnarowicz’s work; for him, they represented a version of reality that society deemed orderly and acceptable. He often cut and reconfigured the maps to gesture toward the groundlessness, chaos, and arbitrariness of both man-made borders and the divisions between “civilisation” and nature.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Fuck You Faggot Fucker (details)

1984

Four black-and-white photographs, acrylic, and collaged paper on Masonite

48 × 48 in. (121.9 × 121.9cm)

Collection of Barry Blinderman

Image courtesy Barry Blinderman, Normal, Illinois

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Prison Rape

1984

Acrylic and spray paint on posters on composition board

48 × 48 in. (121.9 × 121.9cm)

Private collection

Image courtesy Ted Bonin

Photo: Joerg Lohse

Andreas Sterzing

Something Possible Everywhere: Pier 34, NYC

[Wojnarowicz’s Gagging Cow at the Pier]

1983

Courtesy the artist and Hunter College Art Galleries, New York

“So simple, the appearance of night in a room full of strangers, the maze of hallways wandered as in films, the fracturing of bodies from darkness into light, sounds of plane engines easing into the distance.” ~ David Wojnarowicz

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall (by David Wojnarowicz)

1983

Gelatin silver print

8 x 8 inches (20.3 x 20.3cm)

Peter Hujar Archive, courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

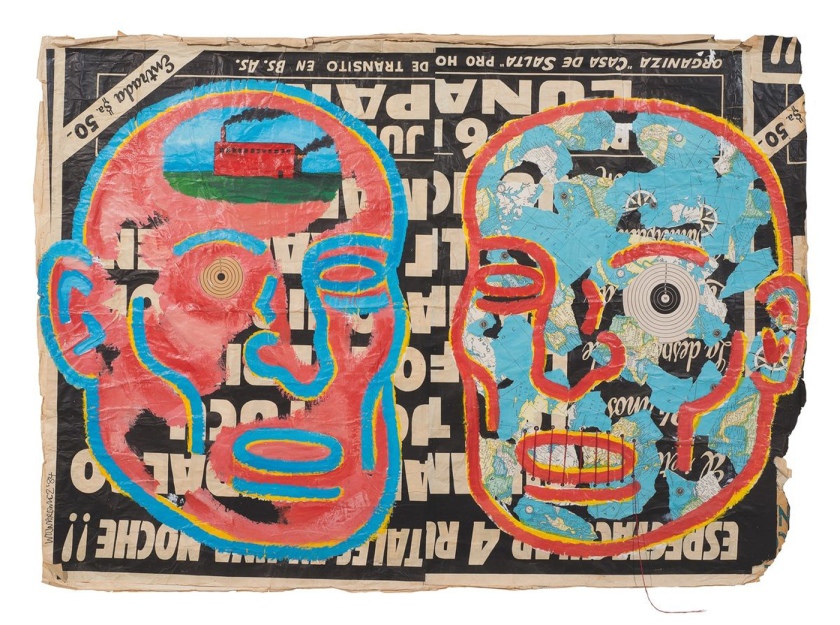

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Two Heads)

1984

Acrylic on commercial screenprint poster

41 × 47 1/2 in. (104.1 × 120.7cm)

Collection of the Ford Foundation

Image courtesy the Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Incident #2 – Government Approved

1984

Acrylic and collaged paper on composition board

51 × 51 × 7/8 in. (129.5 × 129.5 × 2.2cm) framed

Collection of Howard Bates Johnson

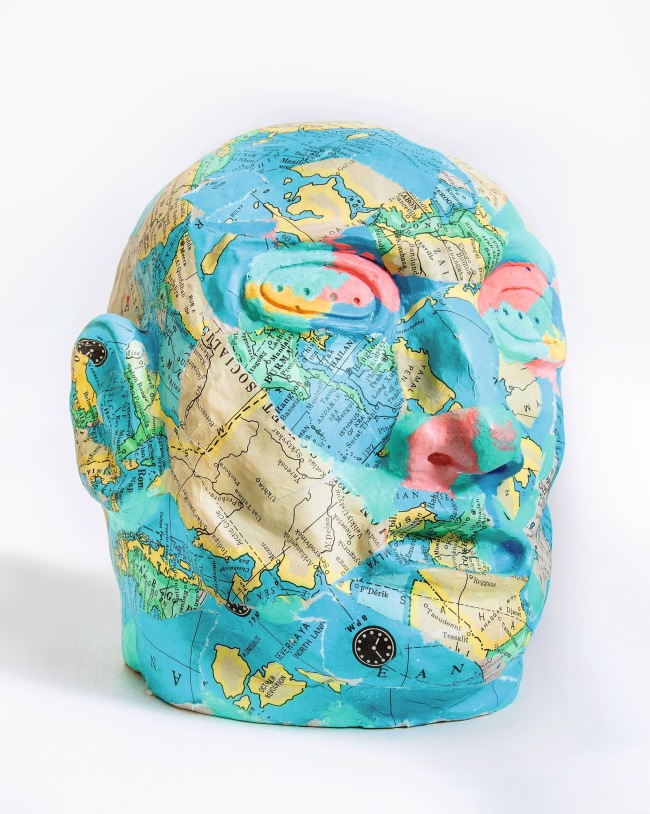

Gallery 3

For his exhibition at the East Village gallery Civilian Warfare in May 1984, Wojnarowicz created a group of cast-plaster heads that he individualised by applying torn maps and paint. He made twenty-three of them, a reference to the number of chromosome pairs in human DNA, and explained that the series was about “the evolution of consciousness.” At the gallery, he installed these “alien heads” on long shelves on a wall painted with a bull’s-eye. Suggesting a ring line, the installation evoked the conflicts then ravaging Central and South America, from the Contra War in Nicaragua to the Salvadoran Civil War to the Argentine Dirty War. The spectre of torture, disappearance, and human-rights abuses cast a shadow over all of the Americas.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1984

From the Metamorphosis series

Collaged paper and acrylic on plaster

9 1/2 × 9 1/2 × 9 1/2 in. (24.1 × 24.1 × 24.1cm)

Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody

Image courtesy Beth Rudin DeWoody

Photo: Monica McGivern

Gallery 4

Wojnarowicz met Peter Hujar in 1980. They were briefly lovers, but the relationship soon transitioned and intensified into a friendship that defied categorisation. The two frequently made artworks using the other as subject. Twenty years Wojnarowicz’s senior, Hujar was a photographer and a known figure in the New York art world, esteemed for his achingly beautiful, technically flawless portraits. At the time of their meeting, Wojnarowicz was still finding his way. It was Hujar who convinced him that he was an artist and, specifically, encouraged him to paint – something Wojnarowicz had never done. After Hujar’s death in 1987 due to complications from AIDS, Wojnarowicz would claim him as “my brother, my father, my emotional link to the world.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Peter Hujar Dreaming/Yukio Mishima: Saint Sebastian

1982

Acrylic and spray paint on Masonite

48 × 48 in. (121.9 × 121.9cm)

Collection of Matthijs Erdman

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

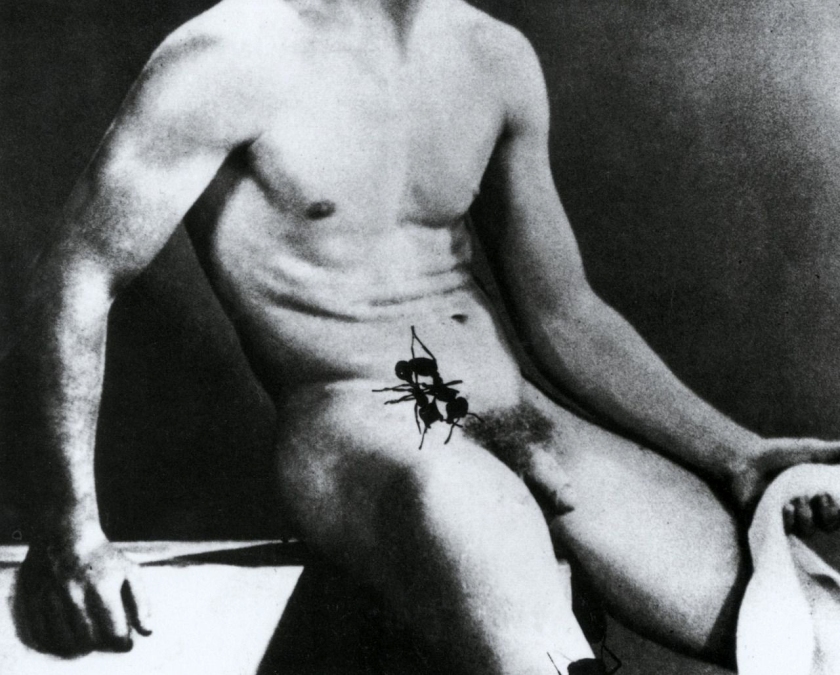

In this painting from 1982, Wojnarowicz composes a meditation on male desire. His friend and mentor Peter Hujar stretches across the bottom, reclining with his eyes closed, apparently dreaming the scene above. An image of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima (1925-1970) masturbating dominates the centre of the composition; it is inspired by the writer’s description of his first masturbatory experience, initiated by a reproduction of a Renaissance painting of Saint Sebastian. The torso of the Christian martyr – young, statuesque, and pierced with arrows – rises above, a glowing aura linking him to the night sky and offering him up as an icon of queerness.

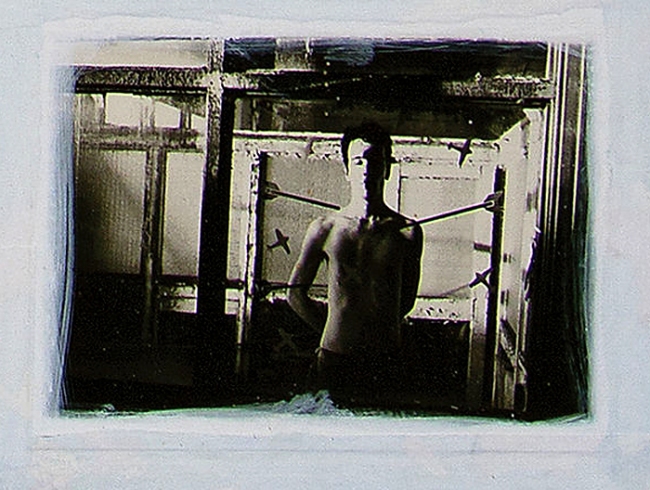

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

David Wojnarowicz (Village Voice “Heartsick: Fear and Loving in the Gay Community”)

1983

Gelatin silver print

10 7/8 × 13 5/8 in. (27.6 × 34.6cm)

Collection of Philip E. and Shelley Fox Aarons

© 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

This photograph of Wojnarowicz with his head bowed appeared on the cover of the June 28, 1983, edition of The Village Voice. It accompanied the article “Heartsick: Fear and Loving in the Gay Community” by Richard Goldstein. At the time of publication, very little was known about HIV and AIDS, including how it spread. Goldstein wrote: “If one were to devise a course of action based on incontrovertible evidence alone, there would be no conclusion to draw. Should I screen out numbers who look like they’ve been around? Should I travel to have sex? Should I look for lesions before I leap? How do I know my partner doesn’t have the illness in its (apparently protracted) dormant stage?” By the end of 1983, there were 2,118 reported AIDS-related deaths in the United States.

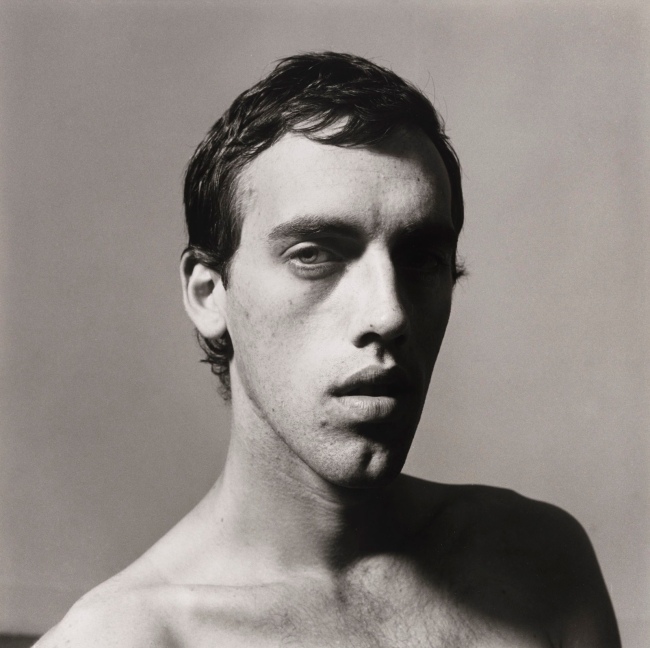

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

David Wojnarowicz

1981

Gelatin silver print

14 3/4 × 14 13/16 in. (37.5 × 37.6cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase with funds from the Photography Committee

© The Peter Hujar Archive

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

David Wojnarowicz with Hand Touching Eye

1981

Gelatin silver print

14 3/4 x 14 3/4″ (37.4 x 37.4cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Fellows of Photography Fund

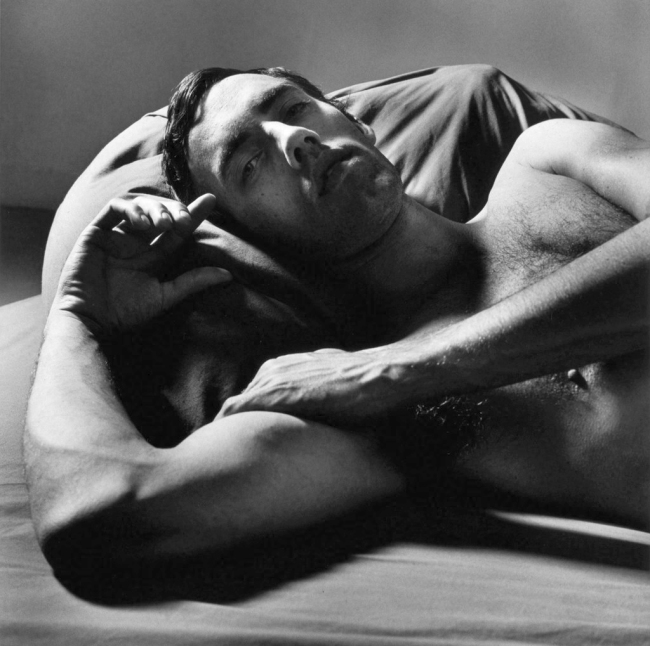

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

David Wojnarowicz Reclining (II)

1981

Gelatin silver print

14 11/16 x 14 13/16 in. (37.3 x 37.6cm)

Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ

Gift of Stephen Koch

Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992)

David Lighting Up

1985

Gelatin silver print

14 5/8 × 14 3/4 in. (37.1 × 37.5cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Promised gift of the Fisher Landau Center for Art

© 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Courtesy PaceMacGill Gallery, N.Y. and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Green Head)

1982

Acrylic on composition board

48 × 96 in. (121.9 × 243.8cm)

Collection of Hal Bromm and Doneley Meris

Gallery 5

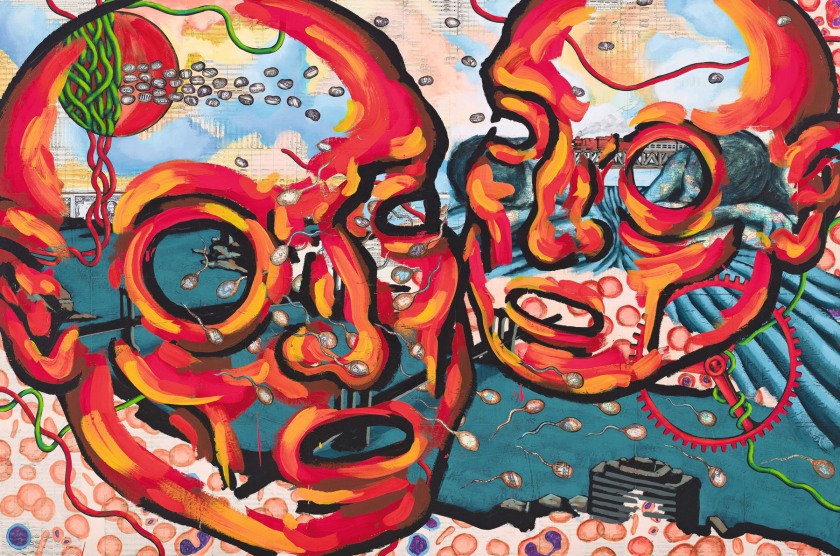

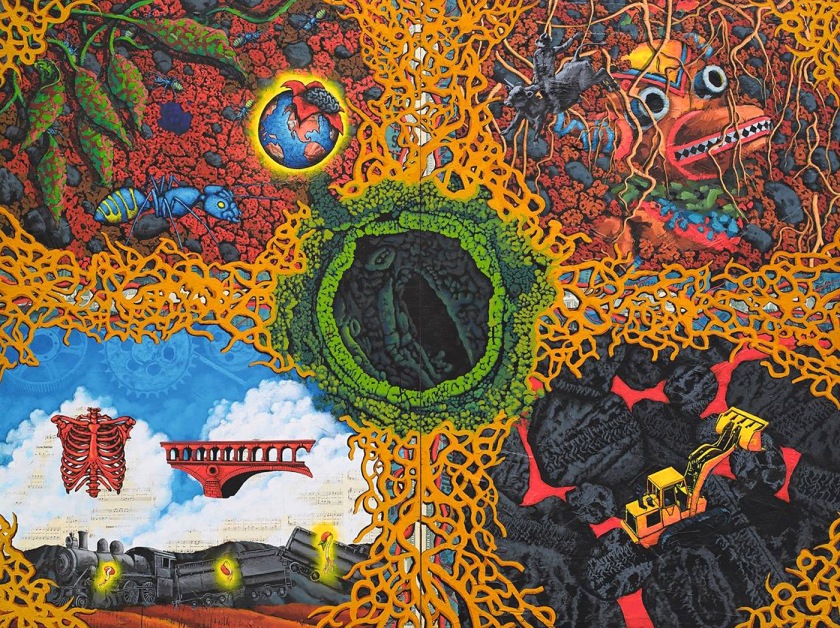

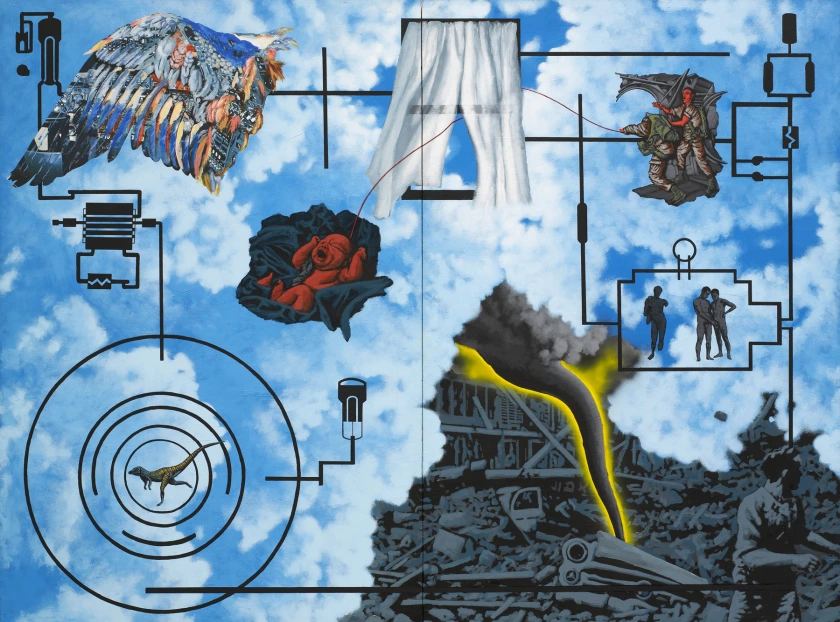

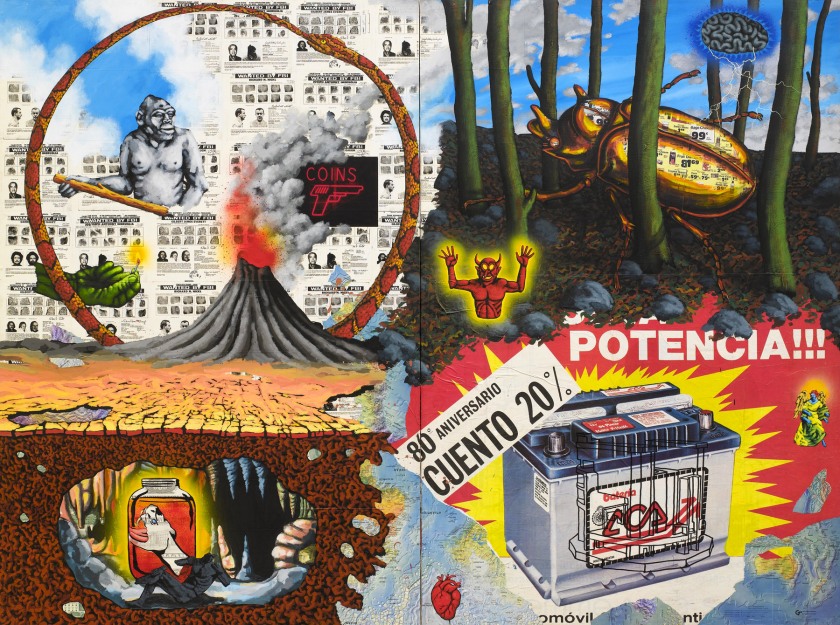

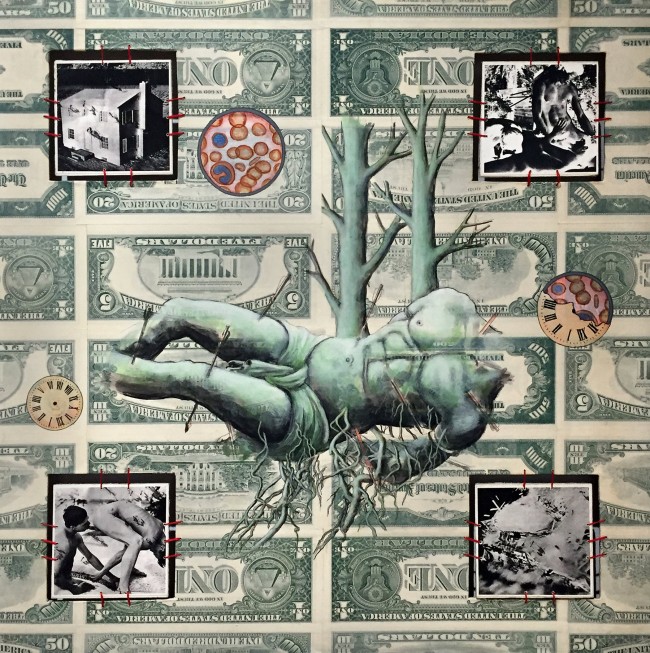

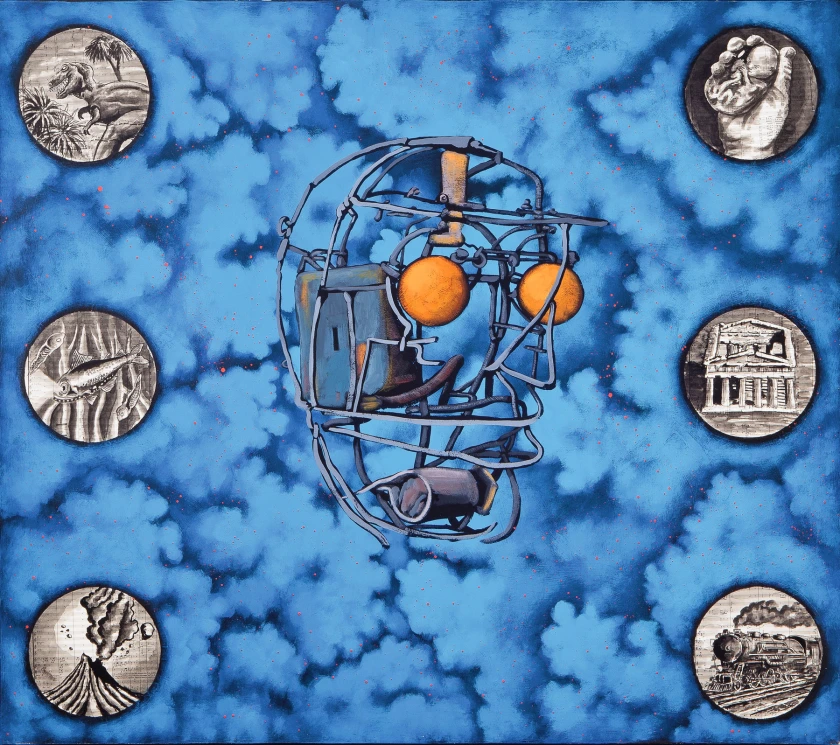

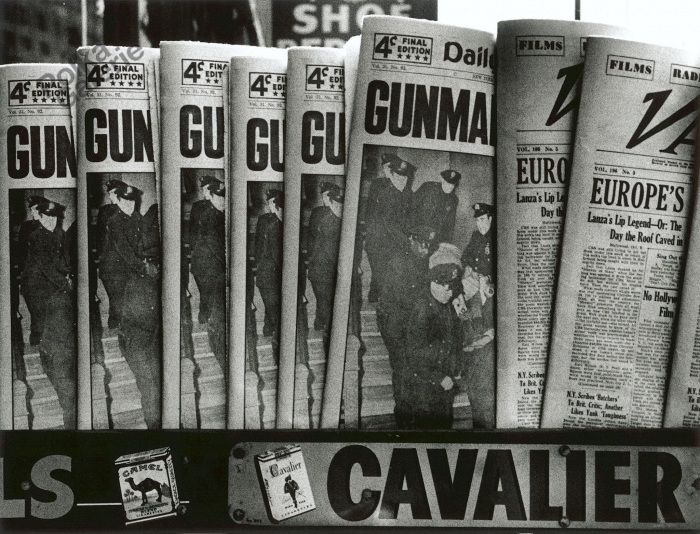

In the mid-1980s Wojnarowicz began to incorporate his disparate signs and symbols into complex paintings. A fierce critic of a society he saw degrading the environment and ostracising the outsider, Wojnarowicz made compositions that were dense with markers of industrial and colonised life. These include railroad tracks and highways, sprawling cities and factory buildings, maps and currency, nuclear power diagrams and crumbling monuments. Interspersed among them are symbols that he connected to fragility, such as blood cells, animals and insects, and the natural world. Wojnarowicz used these depictions as metaphors for a culture that devalues the lives of those on the periphery of mainstream culture. He made these paintings at a time when AIDS was ravaging New York, particularly the gay community. Although AIDS was first identified in 1981, President Ronald Reagan did not mention it publicly until 1985. By the end of that year, in New York alone there already had been 3,766 AIDS-related deaths.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

History Keeps Me Awake at Night (For Rilo Chmielorz)

1986

Acrylic, spray paint, and collaged paper on composition board

72 x 84 in. (170.2 x 200cm)

Collection of John P. Axelrod

Photo: Ron Cowie

In History Keeps Me Awake at Night (for Rilo Chmielorz) Wojnarowicz presents a dystopic vision of American life. Presenting simulated American currency and bureaucratic emblems alongside symbols of crime, monstrosity, and chaos, the painting’s threatening imagery runs counter to the apparently placid sleep of the man below. If the painting is about fear, perhaps the fear of staring down AIDS, Wojnarowicz presents it as an endemic condition in which new fears are built upon historical ones.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Das Reingold: New York Schism

1987

Acrylic and collaged paper on board

48 1/4 × 72 in. (122.6 × 182.9cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Promised gift of Emily Fisher Landau

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

A nightmarish allegory of violence and capitalism, Das Reingold: New York Schism makes reference to Richard Wagner’s opera Das Rheingold (1854), in which the holder of a magical ring will gain the power to rule the world should he renounce love. This narrative assumed particular power at a moment when artists were joining the group ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) to protest the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies and government mismanagement of the AIDS crisis.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

The Death of American Spirituality

1987

Spray paint, acrylic, and collage on plywood, two panels

81 × 88 in. (205.7 × 223.5cm) overall

Private collection

© 1987 The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York.

The Death of American Spirituality contains a number of Wojnarowicz’s recurring symbols and imagery densely layered in a single composition. With its radically juxtaposed motifs that suggest different temporalities – from geologic landforms to emblems of the American West and the Industrial Revolution – the mythical tableau depicts destruction proliferating alongside technological advancement and geographic conquest.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

I Use Maps Because I Don’t Know How to Paint

1984

Acrylic and collaged paper on composition board

48 x 48 in. (121.9 x 121.9cm)

Rubell Family Collection, Miami

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

The Birth of Language II

1986

Acrylic, spray paint, and collaged paper on wood

67 x 79 in. (170.2 x 200.7cm)

Collection of Matthijs Erdman

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Earth, Wind, Fire, and Water

1986

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

78 3/4 in. × 157 1/2 in. (200 × 400cm)

Private collection

Image courtesy Daniel Buchholz and Christopher Müller, Cologne

Photo: Nick Ash

Gallery 6

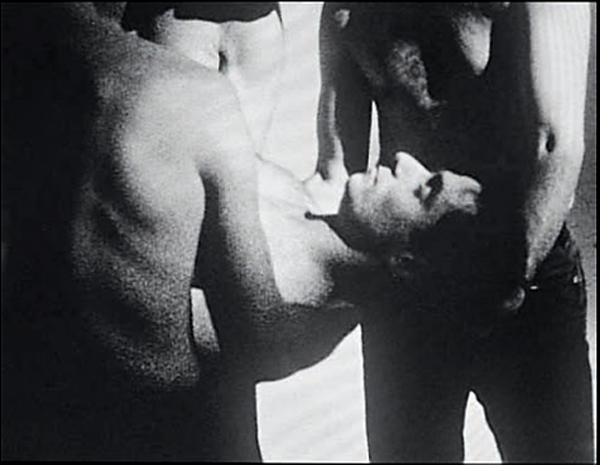

Wojnarowicz filmed constantly during this period, bringing his Super 8 camera with him on his frequent travels. At the end of October 1986, he went to Mexico where he filmed the Day of the Dead festivities and other scenes at Teotihuacán. This footage includes fire ants climbing on objects such as clocks, currency, and a crucifix that Wojnarowicz brought with him. Wojnarowicz, who was raised Roman Catholic, would later speak of Jesus Christ as one who “took on the suffering of all people.” As the AIDS crisis intensified, he sought to find a symbolic language that encapsulated ideas of spirituality, mortality, vulnerability, and violence. He began to edit the Mexican footage into a film entitled A Fire in My Belly, but it was never finished. Ravenous for the world and its offerings, Wojnarowicz used film as form of second sight, a visual notebook, and a record for us to see the world – at least in ashes – as he did.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Still from an unfinished film

Super 8 film, black and white, silent, 3 minutes

Courtesy the Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Unfinished Film (A Fire in My Belly)

1986-1987

Super 8 film transferred to digital video, black-and-white and colour, silent; 20:56 min.

Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University

Original Silent Version of “A Fire in My Belly” by the late David Wojnarowicz. This film was censored by The National Portrait Gallery in early December, 2010.

Gallery 7

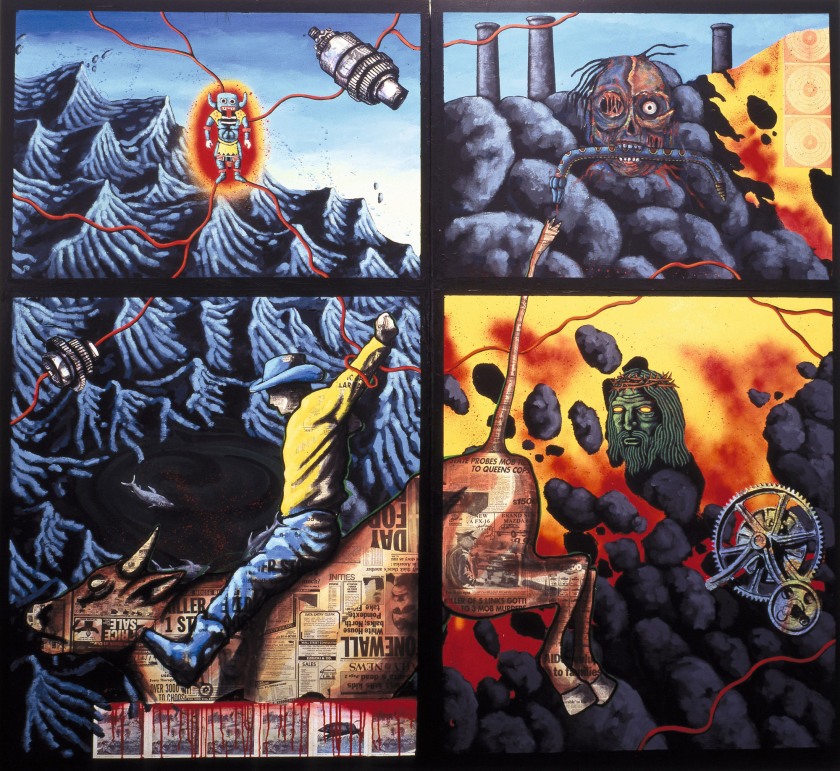

On September 17, 1987, Gracie Mansion Gallery opened an exhibition of Wojnarowicz’s work called The Four Elements. These symbolically and technically dense paintings – allegorical representations of earth, water, fire, and wind – are Wojnarowicz’s take on a theme with a long history in European art. By linking his contemporary moment to a historical subject, he claims a lineage for his work as he suggests the particularity – and particular violence – of his time.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Water

1987

Acrylic, ink, and collaged paper on composition board

72 × 96 in. (182.9 × 243.8cm)

Second Ward Foundation

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Water (details)

1987

Acrylic, ink, and collaged paper on composition board

72 × 96 in. (182.9 × 243.8cm)

Second Ward Foundation

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Earth

1987

Acrylic and collaged paper on wood, two panels

72 × 96 in. (182.9 × 243.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Agnes Gund

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Wind (For Peter Hujar)

1987

Acrylic and collaged paper on composition board, two panels

72 × 96 in. (182.9 × 243.8cm)

Collection of the Second Ward Foundation

Wind (For Peter Hujar) is the most personal and self-referential of Wojnarowicz’s Four Elements paintings. A red line running through an open window connects a baby – based on a photograph of his brother Steven’s newborn – to a headless paratrooper. Wojnarowicz, in his only painted self-portrait, stands behind. The bird’s wing dominating the upper left quarter of the painting is a copy of one of Hujar’s favorite works – a 1512 drawing by the German artist Albrecht Dürer. Hujar would die less than two months after this painting was first exhibited and Wojnarowicz later had the wing carved into his friend’s tombstone. Three days after Hujar’s death, Wojnarowicz wrote in his journal after visiting his grave: “He sees me, I know he sees me. He’s in the wind in the air all around me.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Fire

1987

Acrylic and collaged paper on wood, two panels

72 x 96 in. (182.9 x 243.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Agnes Gund and Barbara Jakobson Fund

Gallery 8: Sound Gallery

Writing and engaging in readings was an important part of David Wojnarowicz’s practice. The transcript on the website is text from audio recordings of Wojnarowicz reading his own work in 1992 at the Drawing Center, New York, at a benefit for Needle Exchange. He read excerpts from his books Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration (1991) and Memories That Smell Like Gasoline (1992); a short work, “Spiral,” which appeared in Artforum in 1992; and another brief piece that begins with the phrase “When I put my hands on your body,” which also appears in one of his photo-based works.

Gallery 9

Wojnarowicz was in the hospital room when Peter Hujar died from complications related to AIDS. He asked the others who were there to leave so that he could film and photograph his friend for the last time. The three tender images of Hujar’s head, hands, and feet installed here come from this final encounter. While Wojnarowicz would continue to draw and paint after Hujar’s death, photography and writing would preoccupy him until the end of his life. He moved into Hujar’s loft, which had a darkroom, enabling him to reconsider – and experiment with – the vast number of negatives he had accumulated over the years.

Wojnarowicz found himself at the centre of political debates involving the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). In a newsletter that the American Family Association distributed to criticise NEA funding of exhibitions with gay content, the religious lobby group excerpted Wojnarowicz’s work out of context. He sued for copyright infringement and won. Wojnarowicz’s hand-edited affdavit and related materials are included here. The searing essay he contributed to the catalogue for Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, an exhibition curated by artist Nan Goldin in 1989, triggered the NEA to withdraw its funding. In it Wojnarowicz strenuously criticised – and personally demonised conservative policy-makers for failing to halt the spread of AIDS by discouraging education about safe sex practices. One of its most memorable passages is the pronouncement: “WHEN I WAS TOLD THAT I’D CONTRACTED THIS VIRUS IT DIDN’T TAKE ME LONG TO REALIZE THAT I’D CONTRACTED A DISEASED SOCIETY AS WELL.”

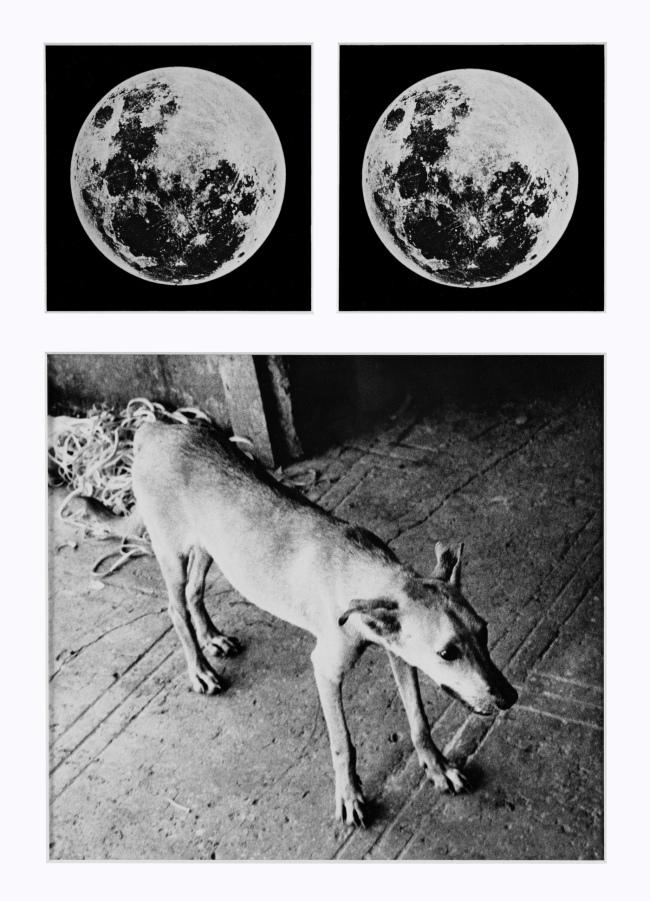

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Bad Moon Rising

1989

Four gelatin silver prints, acrylic, string, and collage on composition board

36 3/4 x 36 5/8 x 2 1/4 in. (93.3 x 93 x 5.7cm)

Collection of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

Phil Zwickler (b. 1954; Alexandria, VA; d. 1991; New York, NY)

Footage of Wojnarowicz speaking about the National Endowment for the Arts controversy (extract)

1989

Video transferred to digital video, color, sound; 7:23 min.

Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University; courtesy the

Estate of Phil Zwickler

Artist David Wojnarowicz discusses right-wing backlash against the NEA and arts funding (circa 1989).

This 1989 video by Phil Zwickler, a filmmaker, journalist, and AIDS activist, was shot in Wojnarowicz’s apartment days before the opening of Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, an exhibition that presented artists’ responses to the AIDS crisis. John Frohnmayer, the chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), withdrew the NEA’s $10,000 grant to the exhibition in response to the essay that Wojnarowicz wrote for the catalogue. The grant was later partially reinstated, but with the stipulation that no money was to be used to support the catalogue. Zwickler filmed Wojnarowicz while the controversy was unfolding.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1987 (printed 1988)

Gelatin silver print

10 1/8 x 14 1/2 in. (25.7 x 36.8cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation and the Photography Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1987 (printed 1988)

Gelatin silver print

10 1/8 x 14 1/2 in. (25.7 x 36.8cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation and the Photography Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1987 (printed 1988)

Gelatin silver print

10 1/8 x 14 1/2 in. (25.7 x 36.8cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation and the Photography Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Hujar Dead)

1988-1989

Black-and-white photograph, acrylic, screenprint, and collaged paper on Masonite

39 × 32 in. (99.1 × 81.3cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Gift of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol in memory of David Wojnarowicz

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

This painting presents an urgent condemnation of systemic homophobia and government inattention to people with AIDS – including, by that point, Wojnarowicz himself – and expresses the artist’s extreme anger at being at the mercy of those in power. The nine photographs at the centre of the painting are of Peter Hujar, taken shortly after his death. The painting was included in Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at New York’s Artists Space from November 16, 1989, to January 6, 1990. Curated by Nan Goldin, the exhibition also included work by other artists responding to the AIDS crisis: David Armstrong, Tom Chesley, Dorit Cypris, Jane Dickson, Philip-Lorca DiCorcia, Darrel Ellis, Allen Frame, Peter Hujar, Greer Lankton, Siobhan Liddel, James Nares, Perico Pastor, Margo Pelletier, Clarence Elie Rivera, Vittorio Scarpati, Jo Shane, Kiki Smith, Janet Stein, Stephen Tashjian, Shellburne Thurber, and Ken Tisa.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Childhood

1988

Acrylic, watercolour, and collaged paper on canvas

42 × 47 1/2 in. (106.7 × 120.7cm)

Collection of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams

Photo: Michael Tropea

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Something from Sleep III (For Tom Rauffenbart)

1989

Acrylic and spray paint on canvas

48 1/2 x 39 x 1 5/8 in. (123.2 x 99.1 x 4.1cm)

Collection of Tom Rauffenbart

Installation view of David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York showing some of the Ant series

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Time and Money)

1988-1989

From the Ant Series

Gelatin silver print

16 × 20 in. (40.6 × 50.8cm)

Collection of Steve Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Desire)

1988-1989

From the Ant Series

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 in. (40.6 x 50.8cm)

Collection of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Violence)

1988-1989

From the Ant Series

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 in. (40.6 x 50.8cm)

Collection of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

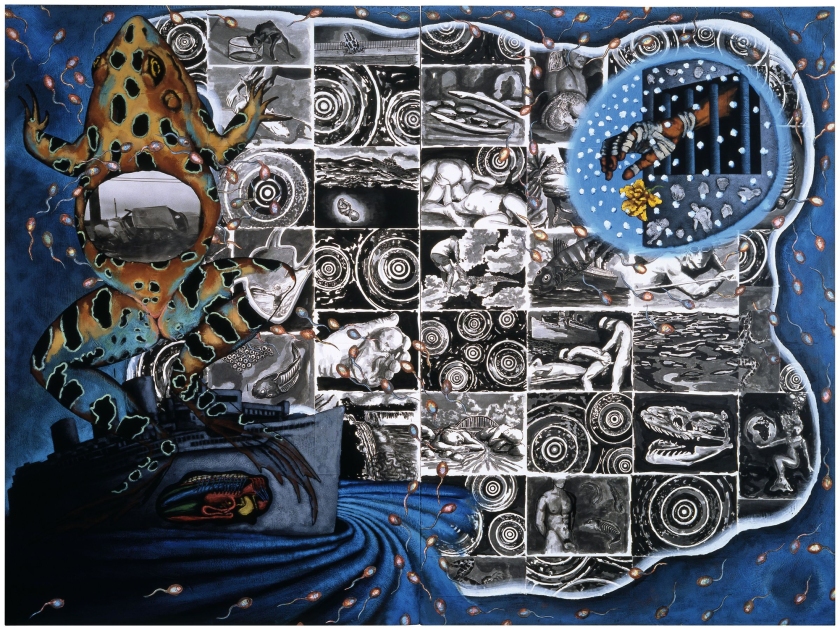

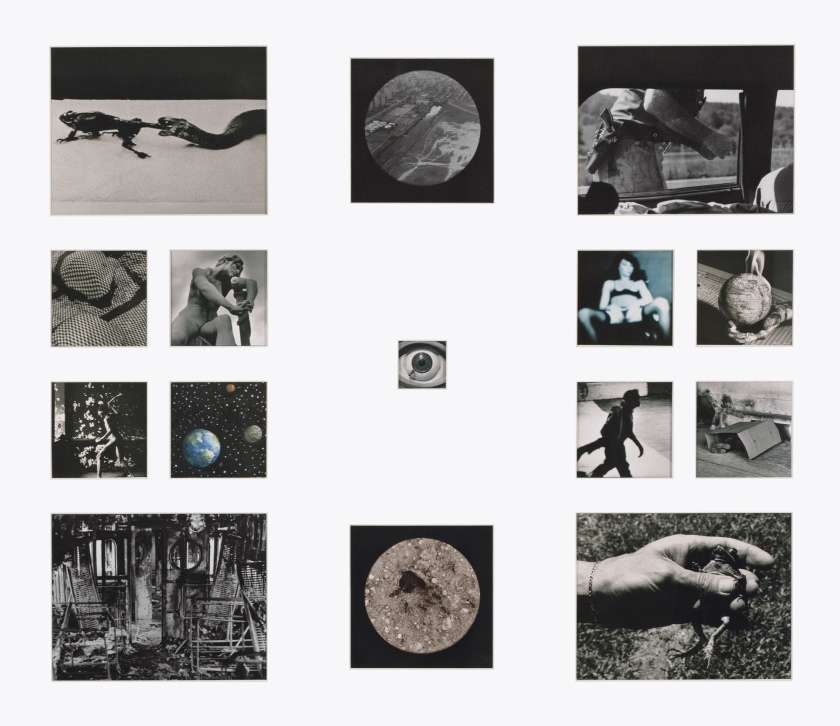

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Spirituality (For Paul Thek)

1988-1989

Gelatin silver prints on museum board

41 × 32 1/2 in. (104.1 × 82.6cm)

Collection of Steve Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

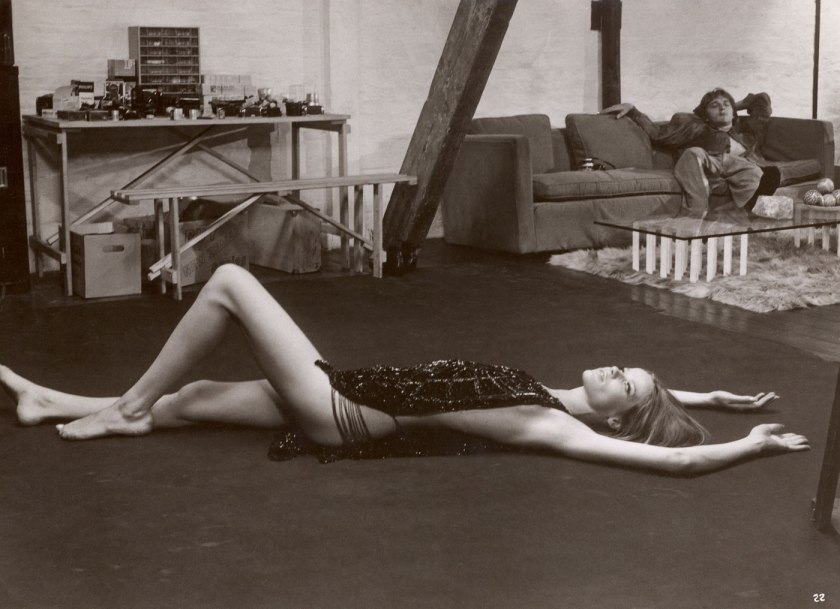

Wojnarowicz often presented a series of photographs as a single composition, as he does with Spirituality (For Paul Thek). This method allows the images to retain their singularity as they merge into one entity, and to serve as potent metaphors for the role – and importance – of the individual in the larger society. The central image of the crucifix was taken while Wojnarwicz was in Teotihuacán, north of Mexico City. He wanted to stage an image that suggested the eternal conflict between nature and man-made culture. Wojnarowicz considered ants to be evolved beings, writing in a 1989 text that they “are the only insects to keep pets, use tools, make war, and capture slaves.” The photograph of the reclining man was taken in 1980 and depicts Wojnarowicz’s friend Iola Carew, then a coworker at the nightclub Danceteria. Carew was the first person Wojnarowicz knew to be diagnosed with AIDS. The work is dedicated to the artist Paul Thek, who died of AIDS-related complications in 1988.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Spirituality (For Paul Thek) (details)

1988-1989

Gelatin silver prints on museum board

41 × 32 1/2 in. (104.1 × 82.6cm)

Collection of Steve Johnson and Walter Sudol

Courtesy Second Ward Foundation

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

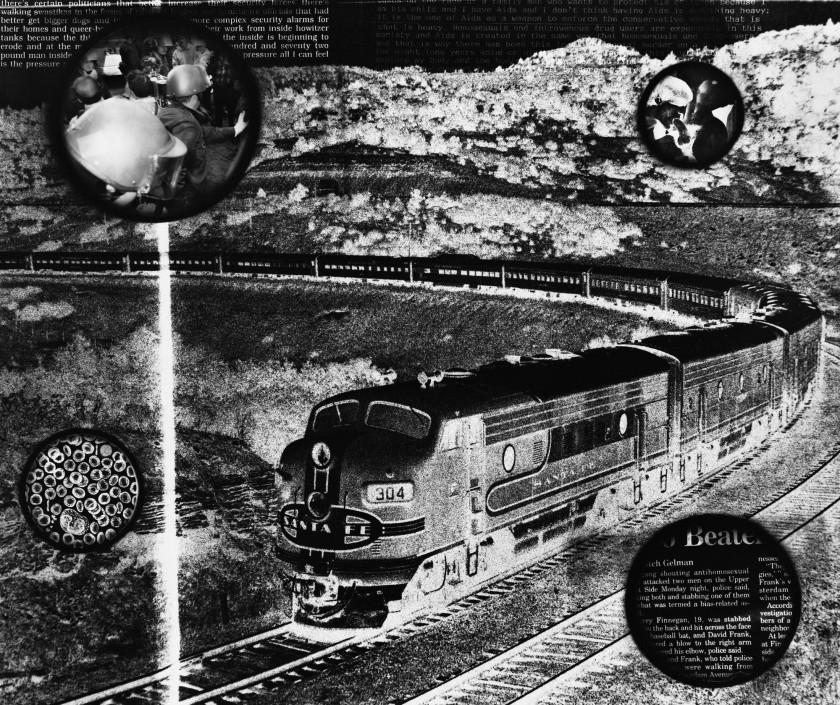

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1989

From the Sex Series (For Marion Scemama)

Gelatin silver print

16 × 19 13/16 in. (40.6 × 50.3cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from The Sondra and Charles Gilman Jr. Foundation, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc., and the Richard and Dorothy Rodgers Fund

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

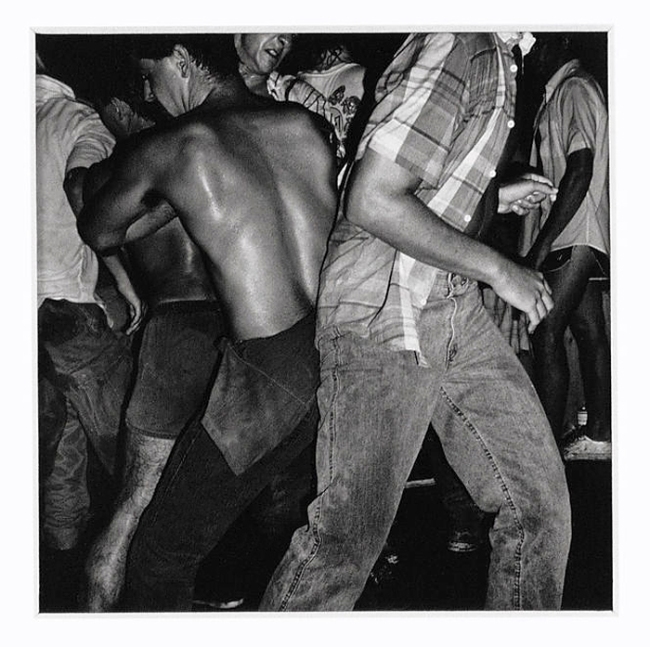

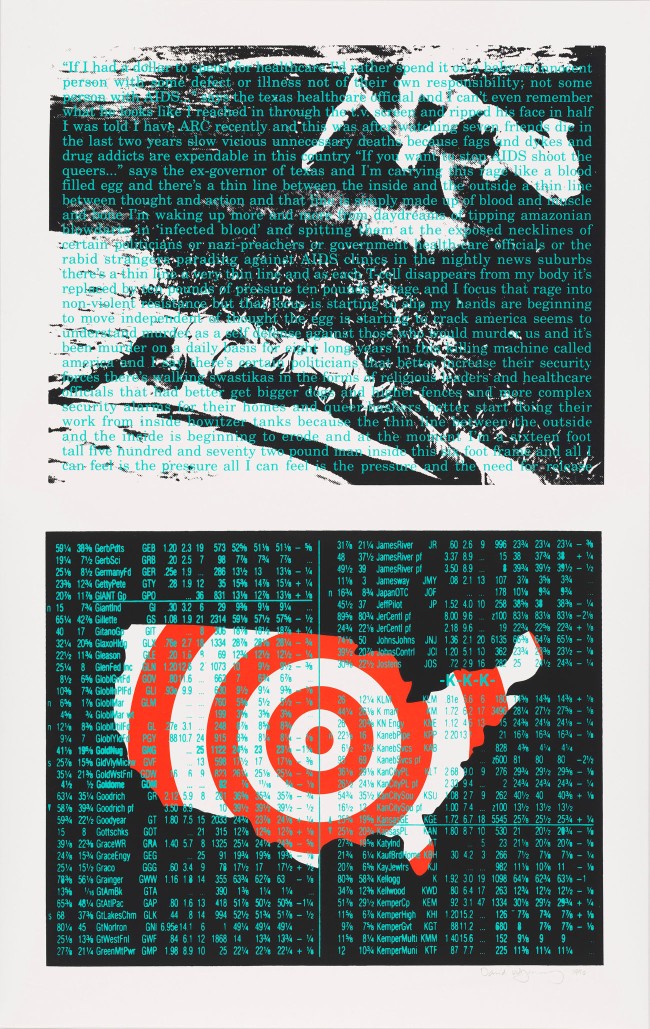

The works in Wojnarowicz’s Sex Series are punctuated with circular insets containing an array of cropped details, including pornographic imagery. For Wojnarowicz, these voyeuristic “peepholes” evoked surveillance photos or objects under a microscope. This was one of his first projects after Hujar’s death and Wojnarowicz’s own diagnosis with HIV. “It came out of loss,” he said. “I mean every time I opened a magazine there was the face of somebody else who died. It was so overwhelming and there was this huge backlash about sex, even within the activist community… And it essentially came out of wanting some sexy images on the wall – for me. To keep me company. To make me feel better.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1989

From the Sex Series (For Marion Scemama)

Gelatin silver print

16 × 19 13/16 in. (40.6 × 50.3cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from The Sondra and Charles Gilman Jr. Foundation, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc., and the Richard and Dorothy Rodgers Fund

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled

1989

From the Sex Series (For Marion Scemama)

Gelatin silver print

16 × 19 13/16 in. (40.6 × 50.3cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from The Sondra and Charles Gilman Jr. Foundation, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc., and the Richard and Dorothy Rodgers Fund

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

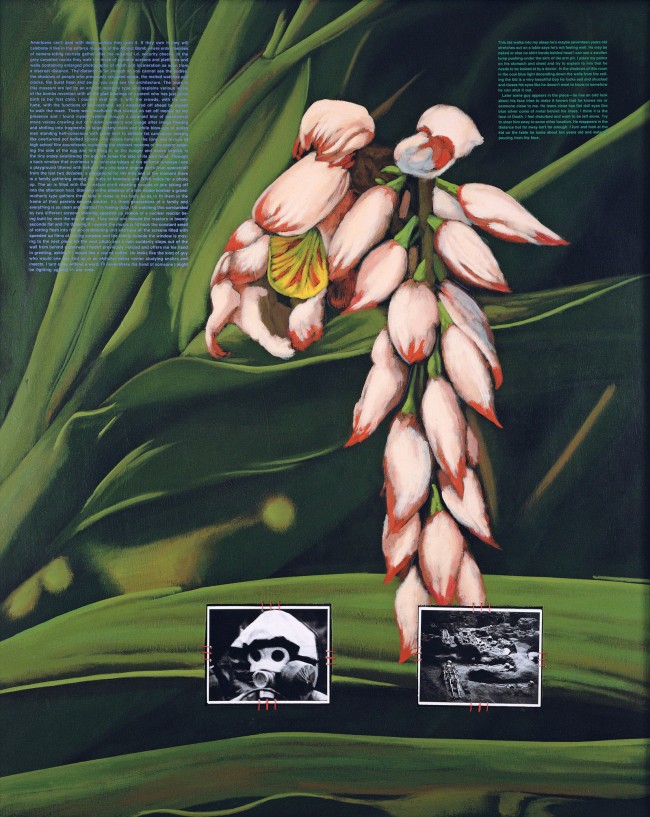

Galery 10: World Made Flesh

The sole survey of Wojnarowicz’s work during his lifetime, David Wojnarowicz: Tongues of Flame, was held in 1990 at Illinois State University in Normal. In the lead-up to the exhibition, he began work on the four large-scale paintings of exotic flowers. Equating the beauty of the body with its very fragility, Wojnarowicz uses the flower as an allusion to the AIDS crisis, his own illness, and a continuum of loss. Importantly, the flower also suggests the possibility and necessity of beauty. The artist Zoe Leonard recalls showing Wojnarowicz, at the height of the AIDS crisis, her small work prints of clouds. Leonard, also an activist, recalls: “I felt guilty and torn. I felt detached – my work was so subtle and abstract, so apolitical on the surface. I remember showing those pictures to David and talking things over with him and he said – I’m paraphrasing – Don’t ever give up beauty. We’re fighting so that we can have things like this, so that we can have beauty again.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Weight of the Earth I

1988

Fourteen gelatin silver prints and watercolour on paper on board

39 x 41 1/4 in. (99.1 x 104.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Family of Man Fund

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Weight of the Earth II

1988-1989

Fourteen gelatin silver prints and watercolor on paper on board

39 x 41 1/4 in. (99.1 x 104.8cm)

Collection of Dunja Siegel

Through compositions like these Wojnarowicz sought to create a language out of images. To him, the combination of images described something painful but also mysterious about the experience of being alive – “about captivity in all that surrounds us,” in his words, and the “heaviness of the pre-invented experience we are thrust into.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Fever

1988-1989

Three gelatin silver prints on museum board

31 × 25 in. (78.7 × 63.5cm)

Collection of Michael Hoeh

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Something from Sleep IV (Dream)

1988-1989

Gelatin silver print, acrylic, and collaged paper on Masonite

16 × 20 1/2 in. (40.6 × 52.1cm)

Collection of Luis Cruz Azaceta and Sharon Jacques

Image courtesy Luis Cruz Azaceta and Sharon Jacques

Photo: by Dylan Cruz Azaceta

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

I Feel A Vague Nausea

1990

Five gelatin silver prints, acrylic, string, and screenprint on composition board

62 × 50 × 3 in. (157.5 × 127 × 7.6cm)

Collection of Michael Hoeh

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Americans Can’t Deal with Death

1990

Two black-and-white photographs, acrylic, string, and screenprint on Masonite

60 × 48 in. (152.4 × 121.9cm)

Collection of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

“Americans can’t deal with death unless they own it. If they own it they will celebrate it…”

Gallery 11

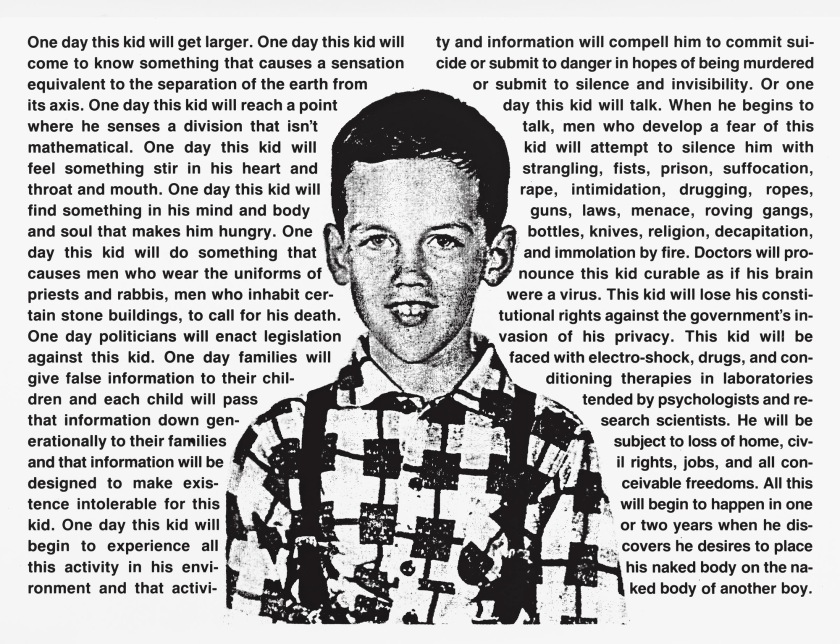

Wojnarowicz’s work concerns itself with the mechanisms, politics, and manipulations of power that make some lives visible and others not. The will to make bodies present – the compulsion to clear a space for queer representations not commonly seen through language and image – was threaded throughout his work, exacerbated by the AIDS crisis, and crystallised in his work. Untitled (One Day This Kid… ) (1990-1991) is perhaps Wojnarowicz’s best-known work. Black script shapes the boundary of a boy’s body – a boy whom we know, with his high forehead, prominent teeth, and electric eyes, is Wojnarowicz as a child. He sits for what we assume is a school picture, and he’s no older than eight. The text that surrounds him projects the child into a future scarred by abuse and homophobia. This artwork, like many by Wojnarowicz, has rightly come to embody the spirit of protest, struggle, and resistance. Wojnarowicz died on July 22, 1992. By the end of that year, 38,044 others in New York had died from AIDS-related complications. In his essay “Postcards from America: X Rays from Hell,” Wojnarowicz states what is equally true of art and protest: “With enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Sub-Species Helms Senatorius

1990

Silver dye bleach print (Cibachrome)

16 x 20 in. (40.6 x 50.8cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Gift of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol

In this work, Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina appears as a spider with a swastika on his back. In 1989, in response to the controversy regarding his essay for the Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing catalogue, Wojnarowicz drafted a press release that included a description of Helms as one of seven particularly bad actors in the fight against AIDS. It read, in part:

‘One of the more dangerous homophobes in the continental United States… Has introduced legislation that denies federal funding for any program that mentions homosexuality… Cut out any and all AIDS education funding that relates to gays and lesbians. Introduced legislation that we must now live with that prevents any HIV-positive people or PWA’s [people with AIDS] from entering any border of the U.S.A. as well as deporting people with green cards forcibly tested and found to be HIV-positive.’

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Act-Up)

1990

Screenprint

23 1/8 × 27 5/8 in. (58.7 x 70.2cm) each

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Steven Johnson and Walter Sudol

© The Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Bread Sculpture

1988-1989

Bread, string, and needle with newspaper

11 1/2 × 14 1/8 in. × 6 in. (29.2 × 35.9 × 15.2cm)

Collection of Gail and Tony Ganz

Photo: Ed Glendinning

Wojnarowicz used red string as a material throughout his practice. From his early supermarket posters to the flower paintings, he stitched red string into the surface of his compositions to suggest the seams and irreconcilable breaks in culture. In his unfinished film A Fire in My Belly (1986-1987, see above), Wojnarowicz included footage of the stitching together of a broken loaf of bread. This sculpture is a physical manifestation of that earlier idea. The film also included footage of what appeared to be a man’s lips being sewn together. A version of that image by Andreas Sterzing – picturing Wojnarowicz himself – would become one of the most galvanising images to come out of the AIDS crisis.

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (One Day This Kid…)

1990-1991

Photostat mounted on board

29 13/16 × 40 1/8 in. (75.7 × 101.9cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase, with funds from the Print Committee

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

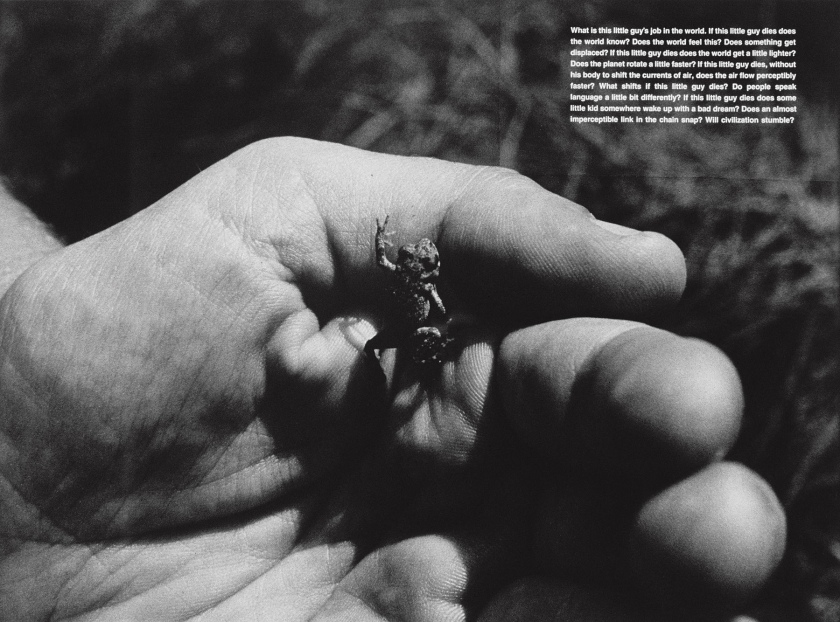

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

What Is This Little Guy’s Job in the World

1990

Gelatin silver print

13 3/4 × 19 1/8 in. (34.9 × 48.6cm)

Collection of Penelope Pilkington

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

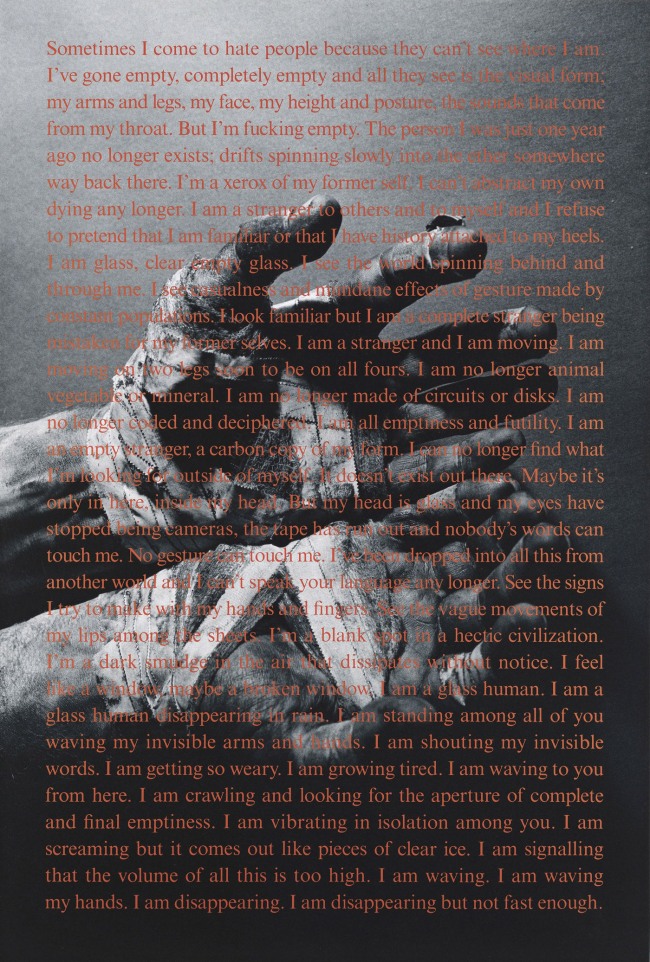

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Sometimes I Come to Hate People)

1992

Gelatin silver print and screenprint on board

39 9/16 × 26 7/8 in. (100.5 × 68.3cm)

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Purchase with funds from The Sondra and Charles Gilman, Jr. Foundation, Inc., the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation Inc., and the Richard and Dorothy Rodgers Fund

Image © Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

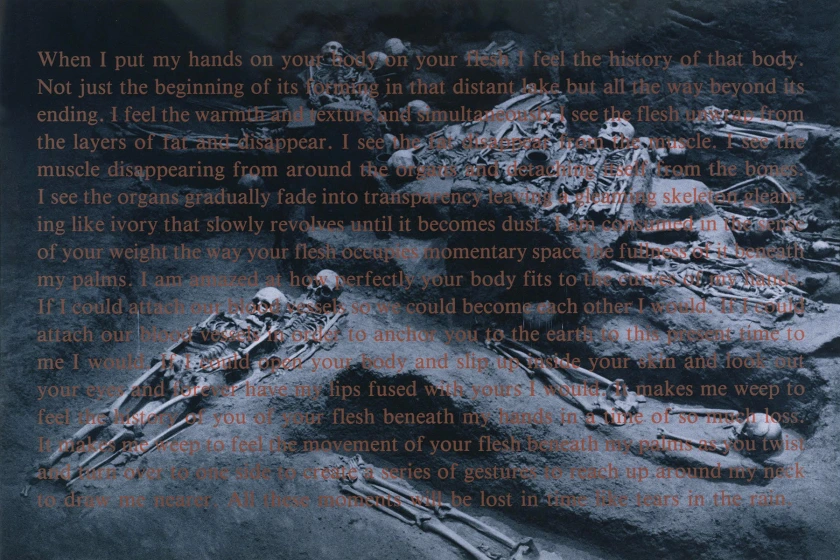

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (When I Put My Hands on Your Body)

1990

Gelatin silver print and screenprint on board

26 x 38 in. (66 x 96.5cm)

Collection of Eric Ceputis and David W. Williams

Promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago

Wojnarowicz visited Dickson Mounds, a museum on the site of an ancient Indigenous community in Lewistown, Illinois, around the time of his 1989 exhibition at Illinois State University. There, he photographed a burial site displaying skeletons and artefacts that had been excavated in 1927. Wojnarowicz, facing his own mortality and the deaths of many whom he loved, returned to the photograph a few years later and layered it with his own text about loss to create this work. The exhibit at Dickson Mounds closed in 1992 after years of protests by Native American activists and their supporters who objected to the public display of human remains. Activists also were fighting at the national level around this time for legislation affirming Indigenous peoples’ right to protect the graves and remains of their ancestors. Wojnarowicz, who frequently wrote and spoke out in support of those who had been forgotten and disenfranchised due to U.S. policies, including Native Americans, recorded the following in an audio journal from 1989: “If I’m making a painting about the American West and I want to talk about the railroad bringing culture – white culture – across the country and exploiting or destroying Indian culture… I see that there’s a certain amount of information that is totally ignored in this country. That all this is built on blood.”

David Wojnarowicz (American, 1954-1992)

Untitled (Face in Dirt)

1991 (printed 1993)

Gelatin silver print

19 × 23 in. (48.3 × 58.4cm)

Collection of Ted and Maryanne Ellison Simmons

Image courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, New York

This photograph was taken in late May 1991 at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico while Wojnarowicz and his friend Marion Scemama took a road trip around the American Southwest. Cynthia Carr, Wojnarowicz’s biographer, describes how the photograph came to be:

‘He had been there before and knew exactly where he wanted to stage this. “We’re going to dig a hole,” he told her, “and I’m going to lie down.” They began digging without saying a word, a hole for his upper body and a bit for the legs. They used their hands. The dirt was loose and dry. He lay down and closed his eyes. Marion put dirt around his face till it was halfway up his cheeks and then stood over him, photographing his half buried face first with his camera and then with hers.’

Whitney Museum of American Art

99 Gansevoort Street

New York, NY 10014

Phone: (212) 570-3600

Opening hours:

Mondays: 10.30am – 6pm

Tuesdays: Closed

Wednesdays, Thursdays 10.30am – 6pm

Friday 10.30am – 10pm

Saturdays and Sundays: 10.30am – 6pm

![Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992) 'Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall [by David Wojnarowicz]' 1983 Peter Hujar (American, 1934-1992) 'Canal Street Piers: Krazy Kat Comic on Wall [by David Wojnarowicz]' 1983](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/07/peter-hujar-canal-street-piers-krazy-kat-comic-on-wall-by-david-wojnarowicz-web.jpg?w=650&h=656)

![Ana Mendieta. 'Itiba Cahubaba (Esculturas Rupestres)' [Old Mother Blood (Rupestrian Sculptures)] 1982](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/ana-mendieta_itiba-cuhababa-web.jpg?w=840)

![Georges Hugnet (French, 1906-1974) 'Untitled [Surrealist beach collage]' c. 1935 Georges Hugnet (French, 1906-1974) 'Untitled [Surrealist beach collage]' c. 1935](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/georges-hugnet-untitled-surrealist-beach-collage.jpg?w=806&h=1024)

![Tacita Dean. 'Darmstädter Werkblock [Still]' 2007 Tacita Dean. 'Darmstädter Werkblock' 2007 (still)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/darmstadter-werkblock-still.jpg?w=840&h=559)

![Tacita Dean. 'Noir et Blanc [Still]' 2006 Tacita Dean. 'Noir et Blanc [Still]' 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2009/07/noir_et_blanc-2006.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.