May 2021

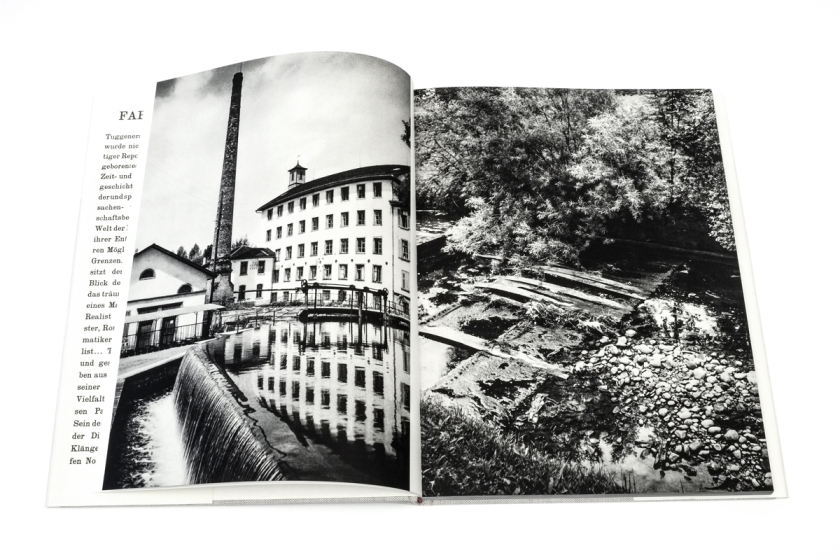

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men are parked in the stands upstairs]

May 14, 1941

Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men are parked in the stands upstairs. The centre of the gymnasium is emptied. Only police officers circulate. The first stage of the roundup has already taken place: the summoned Jews have entered the mousetrap. We see for the first time the interior of Japy and the hundreds of Jewish men crowded together.

Death, duplicity and dishonour

Recently discovered at a Normandy flea market, these photographs by German photographer Harry Croner are taken from 5 contact sheets of 35mm negatives (probably taken on a Leica or similar). These documentary photographs are efficient, well seen, silent and in light of subsequent events… eloquent and emotional. They depict the first roundup of French Jews in Paris on May 14, 1941 at the Japy Gymnasium and a day later at the internment camps into which they were placed.

Lured to several places across the city in a pre-planned trap, Jews were “summoned to town halls across the city for what was billed as routine registration. Instead, the 3,747 men who showed up were arrested by the French authorities… As far as the Japy gymnasium is concerned, 1,061 Jews are summoned at 7.00 am; 800 respond to the summons. When they arrive, they are checked and detained inside the gymnasium. The person accompanying them is asked to go to their home and return with a suitcase containing their personal belongings.”

Today, we know that these images are probably the last photographs of these men alive that were ever taken. They were held in the internment camps for a year before being deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. A year later during the “during the Vel’ d’Hiv’ Roundup of July 16 and 17, 1942, it is the families’ turn to be arrested and detained in these same camps before their deportation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp”

In collusion with and at the behest of their Nazi overlords, this was not the French government’s finest hour.

The roundup – overseen by the Germans, supervised by government officials (through the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, created by the Vichy State in March 1941 and run by fascist and anti-Semite Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, Commissioner-General for Jewish Affairs), enforced by the French police – was undertaken with alacrity, complicity and a ruthless efficiency.

The ironic aspect of these photographs is that Harry Croner, the German Army photographer, was soon after kicked out of the German Army after it was discovered that his father was Jewish. “In 1940 Croner was drafted and came to the Western Front as a war correspondent, but was then dismissed as “unfit for military service” because of his Jewish father. Back in Berlin, he worked in his shop for a while. In 1944, Croner was sent to a labour camp and in March 1945 was taken prisoner by the Americans, from which he was not released until April 1946.” So Croner ended up in the very place, a concentration camp, which he depicted so efficiently a few years earlier.

The head of the museum’s photography department Lior Lalieu-Smadja has wondered whether this knowledge of his Jewish father made Croner capture these Jewish men in a more humane light than other propaganda photographs of the same event. In an emotional sense I would say “yes” to this question, but in a technical sense, I do not think so. I don’t think the knowledge of his heritage would have influenced the aesthetic and pictorial construction of the images. In the photographs we can observe a wonderful balance within the picture frame – the use of strong intersectional points, the use of diagonals (the angle of the buses in Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station), the use of near to far, the massing of bodies in crowd scenes, the use of flash, evidence of the decisive moment (Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station) as the gendarme and the man turn to look at the camera coupled with the attitude of the man’s leg as he kisses his partner goodbye, and the use of the punctum in the image… the couple sitting on the stairs at top right in Inside the Japy Gymnasium, Paris XI, place of arrest of foreign Jews on May 14, 1941; the boy with his hands in his pockets in Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons; and the women staring out of the window of the Boutique à Louer at far right in Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station, reminiscent of the ghostly faces of men pictured by Eugène Atget staring out of the windows of Parisian bars and cafés.

But above all these are now, today, emotional photographs, ultimately a memorialisation of the soon to be dead, photographs of people that we know are soon to be dead. They are gut wrenching in their simplicity, heart wrenching in their emotional power – the anguish of the women, that last kiss, the stoicism and calm of the men – as we trace the journey of the condemned. We can literally follow the route of one unknown man (see the first three images below) to his known fate.

A final thought enters my head… would Croner have still been in the German Army for the rest of the war, part of the Nazi war machine, if it was not discovered that his father was Jewish? Would he have hidden that fact in order to survive while at the same time serving the fascists even as they killed his own kind? The paradox of this seemingly absurd and contradictory proposition, might have been undeniable.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

All photographs digitally cleaned and balanced by Dr Marcus Bunyan. Many thankx to the Memorial de la Shoah for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

5 contact sheets were recently discovered by the Shoah Memorial, retracing photo after photo of the fate of the Jews summoned by the “green ticket round-up”, the context of the raid, the German and French sponsors and especially the families excluded until now from the known propaganda photos of this roundup. While the press echoed it at the time, the official images were intended to be dehumanising and humiliating for these foreign Jews. The emotion and the dismay of these families, shown in these photos, are a rare illustration of the Shoah in France.

“Pure evil operates tidily, silently and seems so stylish.”

Jane Silberman

“The French gendarmes had licence to slap, beat, kick, whip, or insult any prisoner who broke the [Drancy] camp rules, but since these rules were never published it meant that they could ill-treat whomever they wanted whenever they wanted – and, with one or two honourable exceptions, this is just what they did. In 1942, when there were female and male prisoners in the camp, the French commandant of the camp, Marcelin Vieux, was seen whipping a woman for being too slow to move away from the middle of the yard. Another inmate remembered Vieux punching inmates and beating them with his truncheon. He also vividly recalled his two violently anti-Semitic French subordinates, who never went on patrol without their truncheons at the ready. Dr. Falkenstein, another prisoner, saw one of these men hit a four-year-old girl so hard that he knocked her unconscious.”

David Drake. ‘Paris at War: 1939-1944’. Harvard University Press, 2015, p. 209.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men peer outside the upper windows of the gymnasium] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Never-before-seen photos going on display in Paris this week shine a light on a dark moment in France’s role in rounding up Jews to send to Nazi death camps during World War II. The “green ticket round-up” was first carried out in Paris on May 14 and 15, 1941, with more than 6,000 foreign-born Jews summoned to town halls across the city for what was billed as routine registration. Instead, the 3,747 men who showed up were arrested by the French authorities and shipped to camps south of Paris. Thousands more were rounded up in the following months.

They were held there for a year before being deported to the Auschwitz death camp.

By chance, a stash of 98 photos from the first green ticket round-up, taken by a German soldier on propaganda duty, were recently discovered by the Memorial de la Shoah, the Holocaust Museum of Paris.

Most were taken at the Japy sports hall in the city’s 11th arrondissement, where close to 1,000 were arrested, and where the photos are being put on display from Friday, exactly 80 years on. One shows SS officer Theodor Dannecker, who was in charge of implementing the “Final Solution” in France, alongside French police commissioner Francois Bard in the hall. Others show couples embracing outside, unaware that they would never see each other again.

“These photos are important because we see the opposite of Nazi propaganda that tried to depict these people as sub-human ‘parasites’,” said Lior Lalieu-Smadja, who heads the museum’s photography department. Was that a deliberate move by the photographer? “One has to wonder,” said Lalieu-Smadja, not least because the photographer was identified as Harry Croner, who was soon after kicked out of the German army after it was discovered that his father was Jewish.

The photos were bought years ago by an antiques dealer in Normandy who had found them at a flea market. He pulled them out of storage recently and contacted the museum, who informed him they were the only known pictures from the infamous round-up. Little else is known about the photos’ journey.

“The only thing we know for certain is that once they were taken, they were sent directly to Berlin. The photographer himself could not keep them, which makes this discovery even more incredible,” said Lalieu-Smadja.

Press release from the Memorial de la Shoah website

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Inside the Japy Gymnasium, Paris XI, place of arrest of foreign Jews on May 14, 1941] [with Theodor Dannecker at third right]

May 14, 1941

A German delegation with SS Theodor Dannecker, responsible for Jewish affairs in France, and French led by the prefect of police François Bard, comes to inspect the operation.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men]

May 14, 1941

Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men. They are asked to come back with some things for 2 to 3 days. The reasons given are the same: “examination of the situation”.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons]

May 14, 1941

Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons and are received by the police who guard the entrance to the gymnasium. Women with children arrive with suitcases and packages. The following scenes show them standing in line and waiting their turn to hand over the suitcases.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy gymnasium: families waiting to hand over the suitcases to their loved ones]

May 14, 1941

Green Ticket roundup: The Shoah Memorial discovers a previously unpublished photo-reportage

The Shoah Memorial announces the recent acquisition of five contact sheets, totalling 98 photographs. This as yet unreleased photo-reportage accurately details every step of the first mass arrest of Jews in Paris by the French police forces on the orders of the German authorities 80 years ago, on May 14, 1941.

The discovery in detail

The Shoah Memorial has purchased five contact sheets – documenting the location of the roundup known as the “Green Ticket” on May 14, 1941 – from two specialised collectors. The contact sheets acquired by the Memorial, numbered 182 to 187 (contact sheet 185 is missing), represent 98 photographs. The photographer’s five rolls of film provide a reality that differs greatly from the photos released by the collaborationist press alone. For the first time, the location of the arrests as well as the protagonists of the roundup are captured from multiple angles. Dehumanised until then by propaganda and even completely erased from reportages, the families of the detainees are shown during their emotional farewells, before the very eyes of onlookers and neighbours. The most important element of this discovery, which is indispensable to history and to the duty of remembrance, allows us to follow the trajectory of these rounded-up men, from their arrival at the Japy gymnasium – the site of the trap, in Paris – up to their internment in the camps of the Loiret.

What the photographs reveal

The 98 photographs printed on contact sheets give a chronological, step-by-step run-down of the roundup.

1/ The first images show the protagonists of the roundup engaged in a discussion inside the Japy gymnasium. The two German and French sponsors are perfectly recognisable:

– Théodor Dannecker (1913-1945), who represents Eichmann in France and heads Section IV J of the Gestapo, in charge of Jewish affairs

– Admiral François Bard (1889-1944), the recently appointed Prefect of the Paris Police

2/ The Japy photo series: the arrested men are confined to the upper floor bleachers. The first stage of the roundup has already taken place: the Jews who have been summoned have entered the trap. These as yet unreleased photos show the interior of Japy and the hundreds of Jewish men crowded together, as well as those accompanying them, often their wives

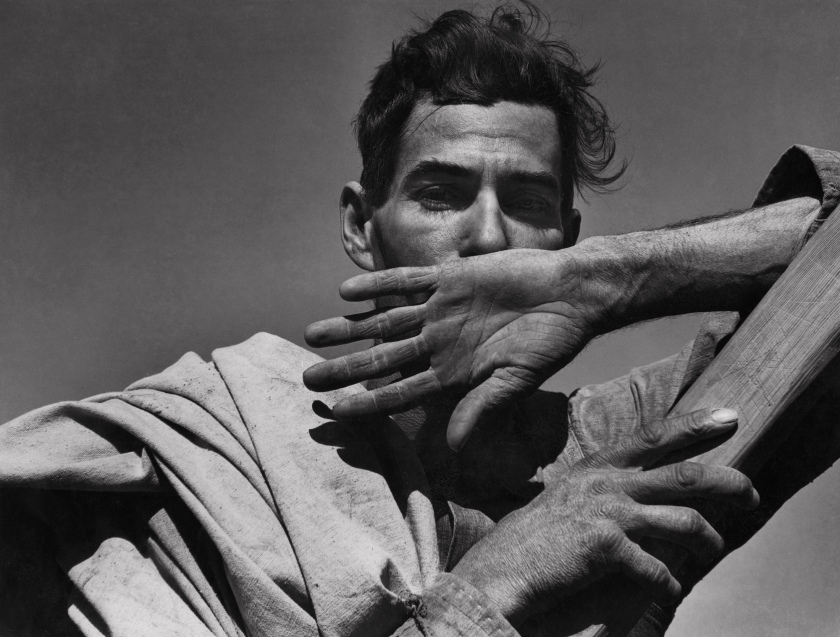

3/ The exterior of Japy: men are still arriving carrying their summons and are received by the police officers at the entrance to the gymnasium. They bid farewell to their families while a line of women and children is formed. They wait to hand over clothes to their loved ones

4/ The neighbourhood is closed off. Neighbours are at their windows. Families are pushed to the back of the street and wait to hear from their loved one. They have anguished faces. The police blocks the street, then evacuates it

5/ Men of all ages who have been arrested come out one by one, watched over by police officers and carrying their belongings, board buses parked just outside the gymnasium, rue Japy

6/ The arrival at the Paris-Austerlitz railway station through the rear entrance to the station

7/ At Pithiviers, a previously unpublished view of the black hangar – of which there were no images until now – during the internment of the Jews, which will subsequently serve as the registration centre for the Vel’ d’Hiv’ detainees and for deportations

The “Green Ticket” roundup: first roundup of Jews in France during World War II

The “Green Ticket” Roundup is the first mass arrest of Jews in Paris, and it takes place on Wednesday May 14, 1941. These unsuspecting men, mainly foreigners from Eastern Europe are summoned on Wednesday morning by the Police Prefecture with a “green ticket” for a “status review” and asked to be accompanied by a relative or friend.

The men, most of them family men who were army volunteers at the beginning of the war and therefore fought for France, expect a verification of their status. Fleeing antisemitism and persecutions in their countries of origin – Poland, USSR, Romania, Czechoslovakia – and believing that they will find refuge in the land of freedom, they are arrested chiefly because they are Jewish and foreigners.

Several assembly points are indicated on the “green tickets”: the Caserne Napoléon (in the 4th arrondissement), the Caserne des Minimes (in the 3rd arrondissement), 52 rue Edouard Pailleron (in the 19th arrondissement), 33 rue de la Grange-aux-belles (in the 10th arrondissement) and the Japy gymnasium (in the 11th arrondissement) as well as other centres in the arrondissement police stations and Paris suburbs.

As far as the Japy gymnasium is concerned, 1,061 Jews are summoned at 7.00 am; 800 respond to the summons. When they arrive, they are checked and detained inside the gymnasium. The person accompanying them is asked to go to their home and return with a suitcase containing their personal belongings.

After that, the 3,700 arrested Jews are taken to the Paris-Austerlitz railway station in special buses, under the supervision of French police officers, and interned in the Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande camps (in the Loiret). They spend more than a year there before being deported directly to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp by Convoy #4 on June 25, 1942, #5 on June 28, 1942 and #6 on July 17, 1942. During the Vel’ d’Hiv’ Roundup of July 16 and 17, 1942, it is the families’ turn to be arrested and detained in these same camps before their deportation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp between July and September 1942.

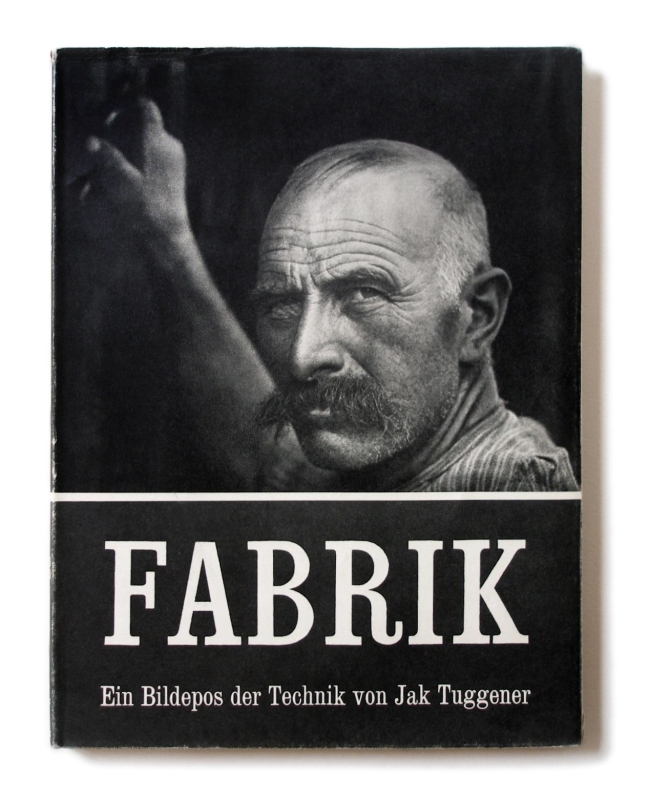

Propoganda photographs

As of the Armistice on June 25, 1940, the press is muzzled in France by the German occupier, and press photography is placed under censorship control. The Propaganda Kompanie (PK), set up within the Wehrmacht, is made up of photographers, cameramen, radio and press reporters, who are equipped with high-performance photographic material. This unit, under the direct control of Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, is in charge of documenting the historic dimension of the military effort and producing propaganda reports for foreign countries, for the press and for domestic agencies.

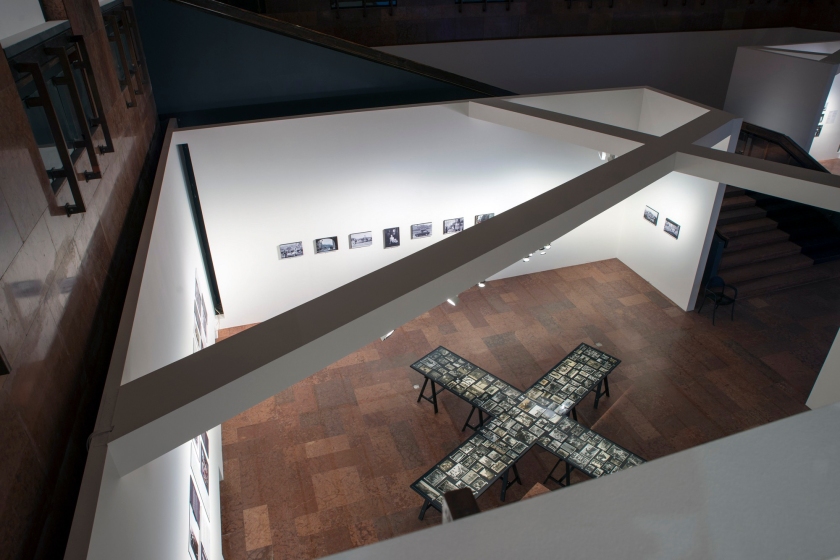

The Shoah Memorial

The Shoah Memorial, Europe’s largest archives center dedicated to the history of the Shoah, is a place of remembrance, of education and of transmission on the history of the genocide of the Jews during World War II in Europe. Today it incorporates five sites: the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the Shoah Memorial in Drancy, the Lieu de mémoire du Chambon-sur-Lignon (Haute-Loire), the CERCIL Musée – Mémorial des Enfants du Vel d’Hiv (Loiret), and the Centre culturel Jules Isaac de Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dôme).

Opened to the public on January 27, 2005 in the historic Marais district, the Paris site provides multiple spaces and an awareness program catering to all audiences: a permanent exhibition on the Holocaust and the history of the Jews in France during World War II; a temporary exhibition space; an auditorium programming screenings and symposia; The Wall of Names on which the names of 76,000 Jewish men, women and children deported from France between 1942 and 1944 as part of the “Final Solution” are engraved; the documentation center (50 million archive materials and 1,500 sound archives, 350,000 photographs, 3,900 drawings and objects, 12,000 posters and postcards, 30,000 cinema documents, 14,500 movie titles including 2,500 testimonials, and 80,000 books) and its reading room; educational spaces where children’s workshops and activities for classrooms and teachers take place; a specialty bookstore.

Better understanding the history of the Holocaust is also aimed at preventing the return of hatred and all forms of intolerance today. The Memorial has also been working for more than a decade on education programs focusing on other genocides of the 20th century, such as the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda, or the Armenian genocide.

Press release from the Shoah Memorial

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: men arrested awaiting their fate in the mousetrap that the Japy gymnasium has become]

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: men arrested awaiting their fate in the mousetrap that the Japy gymnasium has become] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours]

May 14, 1941

The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours and the unusual emotion that reigns around the Japy gymnasium.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours] (detail)

May 14, 1941

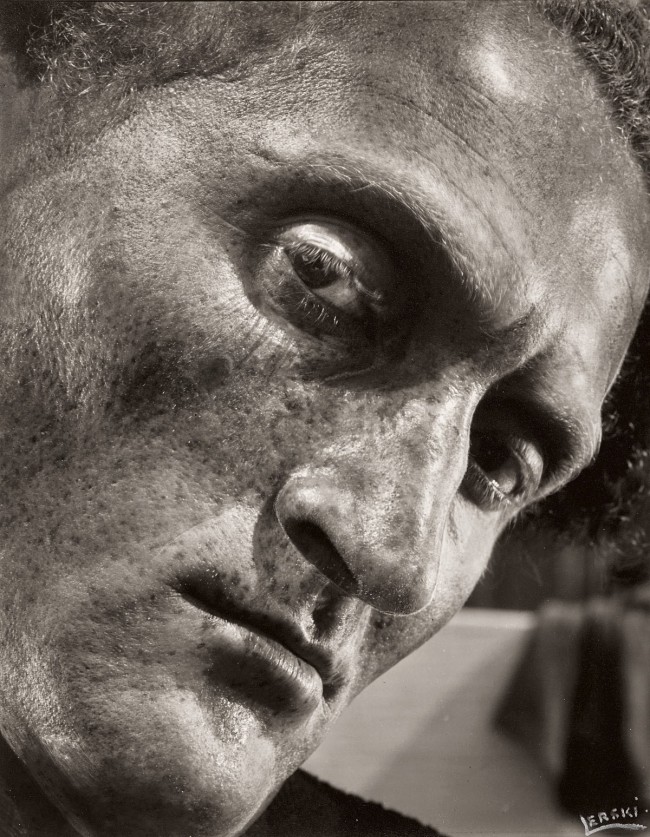

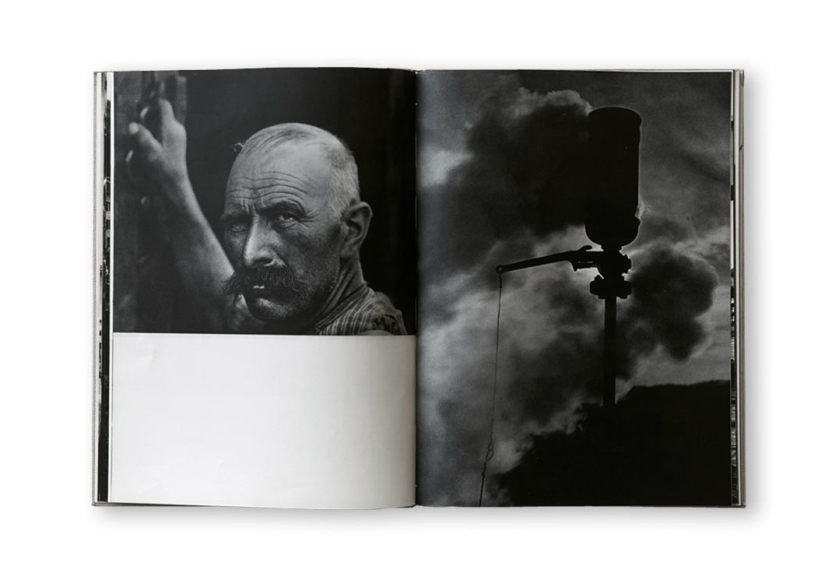

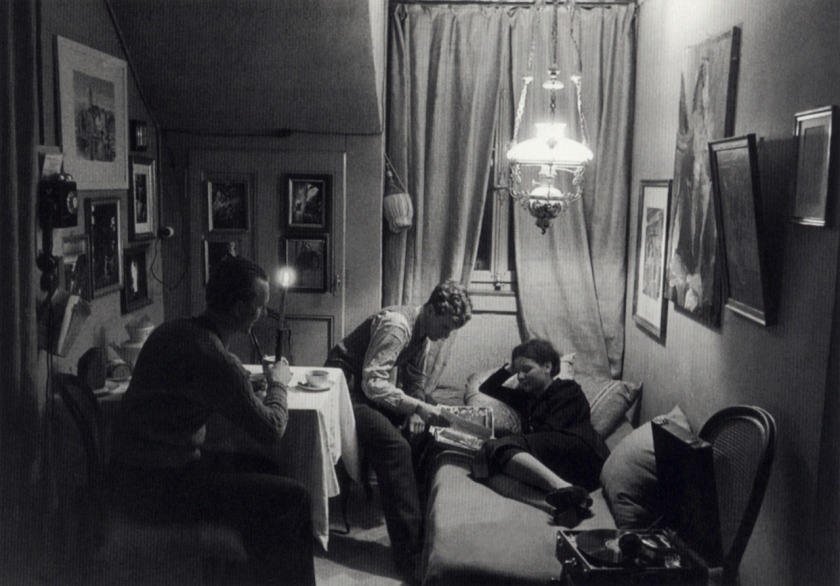

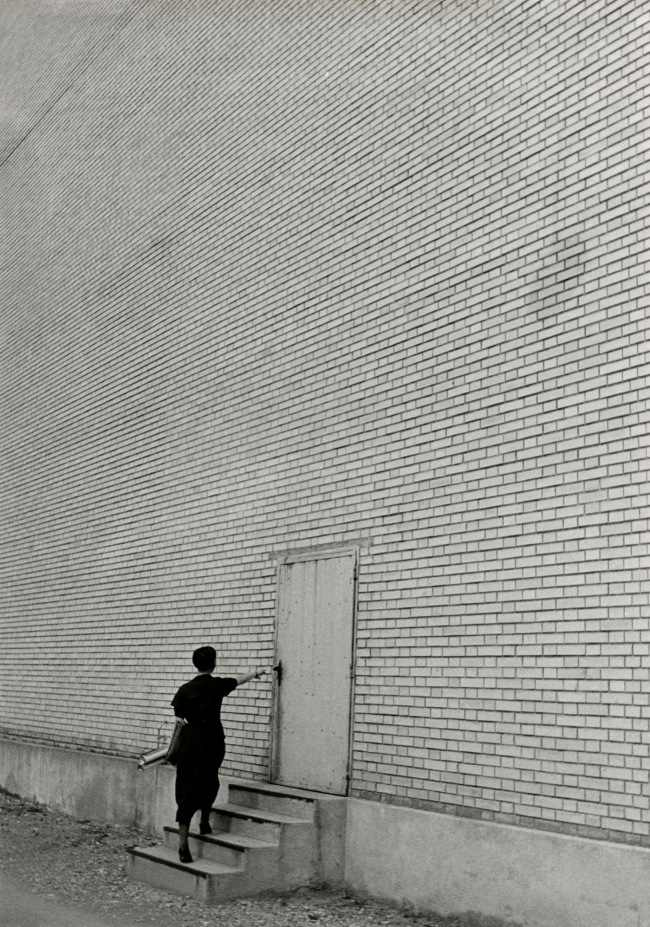

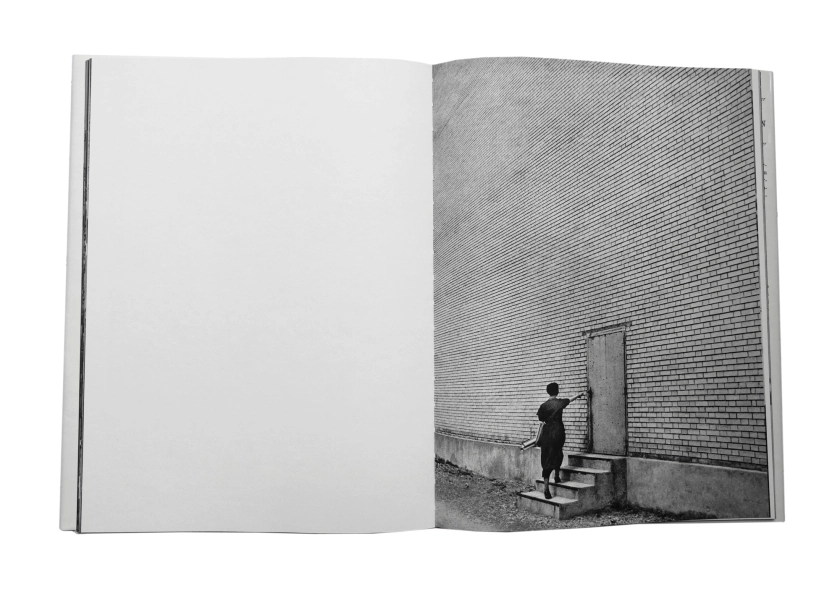

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

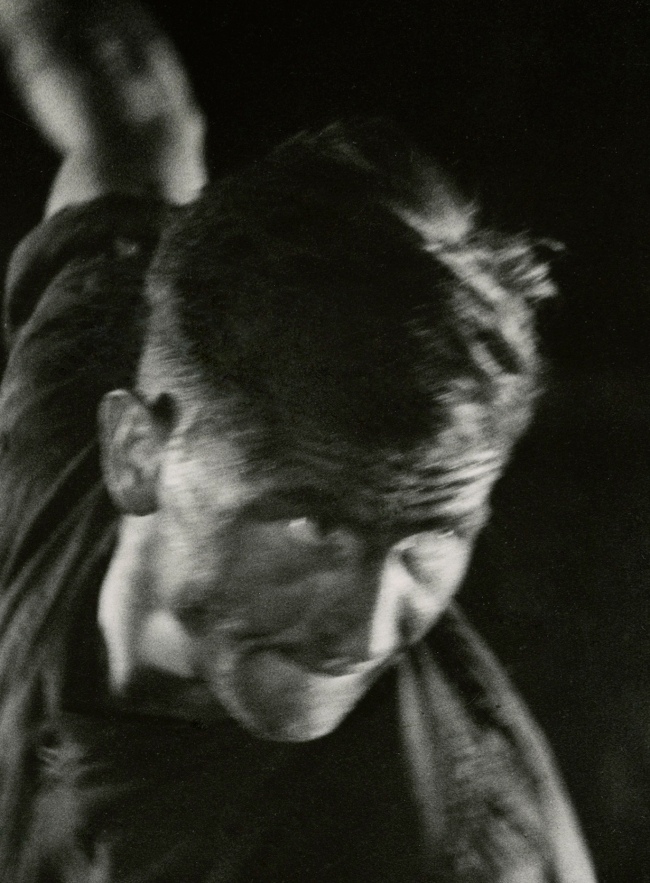

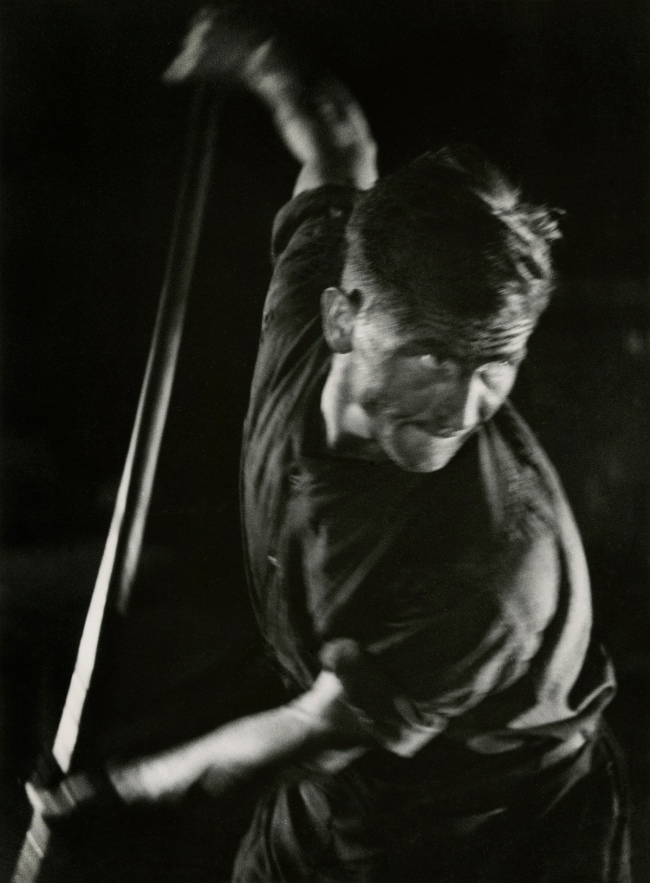

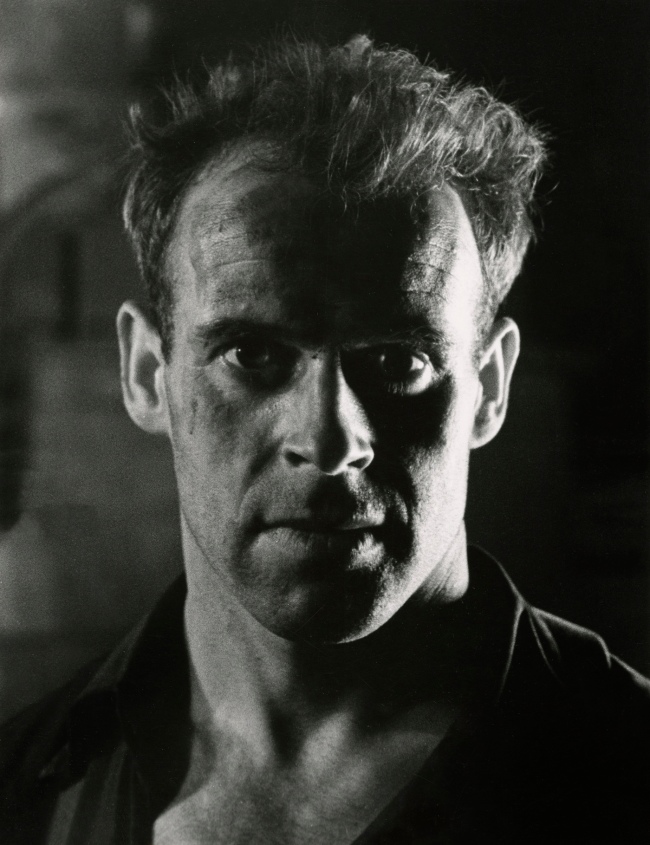

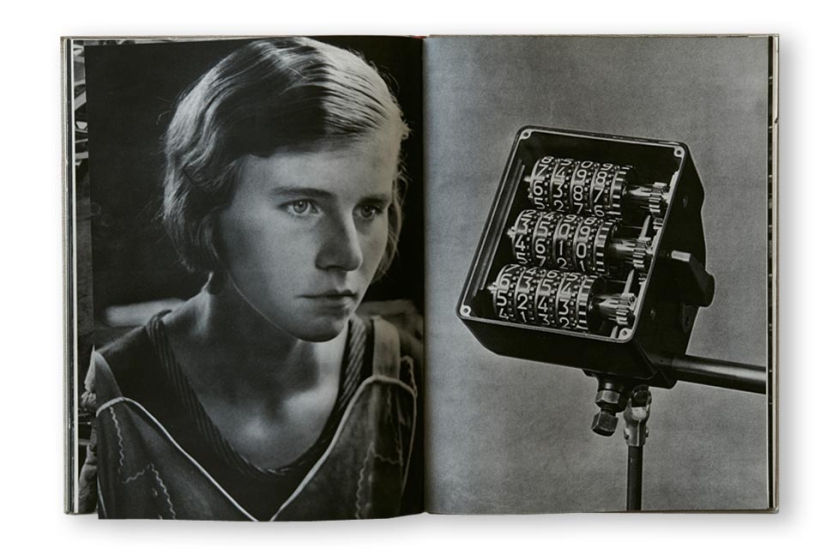

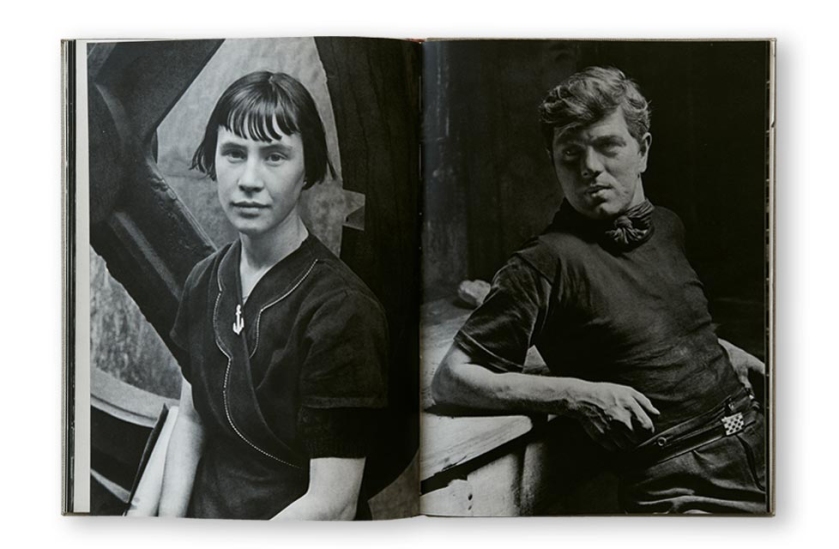

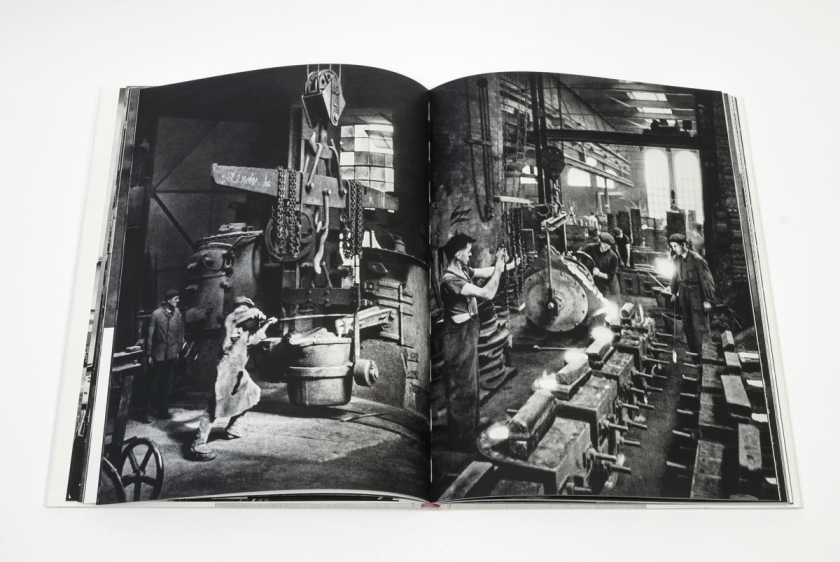

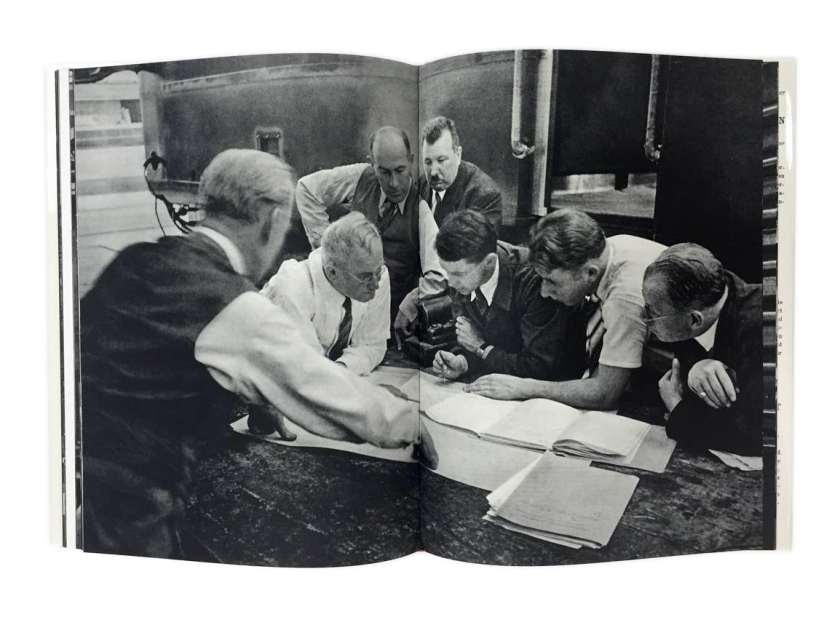

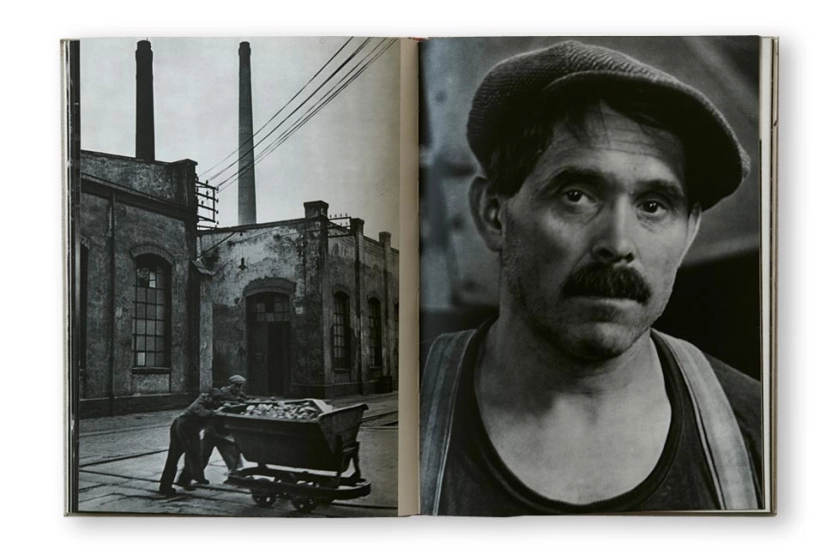

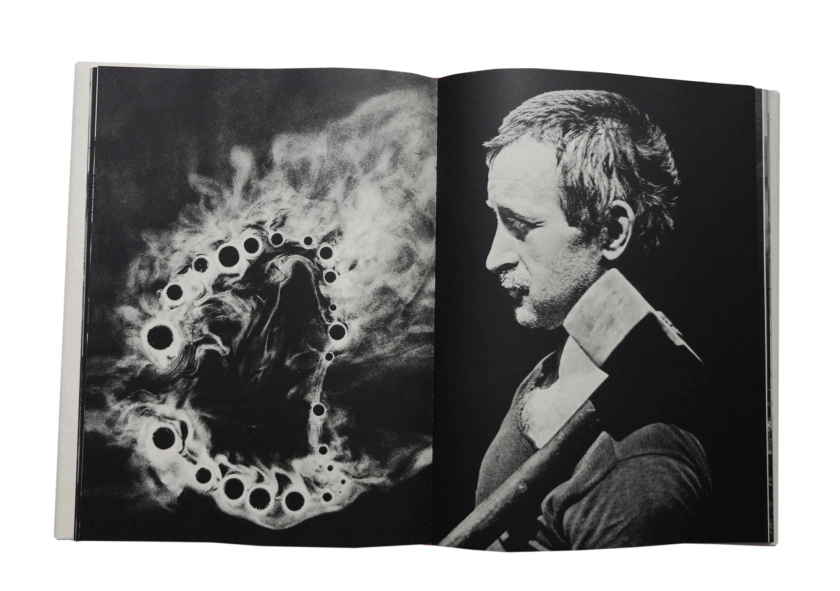

West Berlin stage: Harry Croner’s photographs from four decades

For 40 years, press photographer Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) accompanied life in Halbstadt with his camera: the reconstruction and creation of new landmarks, large and small events, celebrities from culture and politics, especially what happened on the city’s stages. His acquaintance with many artists living and visiting Berlin made it possible for him to take impressive snapshots and portraits. Croner’s photographic work, which is being presented for the first time with this selection, is the chronicle of an era and at the same time an homage to a small island of world politics, which was above all one thing, the big stage for culture.

Late career as a photographer

Harry Croner was born on March 16, 1903 in Berlin. From 1920 to 1922 he completed a commercial apprenticeship, worked for various automobile companies as an advertising manager and finally as a travel representative for Bayerische Motorenwerke. When he set up his own photo business in Berlin-Wilmersdorf in 1933, he probably already had a career as a photographer in mind. In addition to selling cameras and accessories, he also took portraits. In 1940 Croner was drafted and came to the Western Front as a war correspondent, but was then dismissed as “unfit for military service” because of his Jewish father. Back in Berlin, he worked in his shop for a while. In 1944, Croner was sent to a labour camp and in March 1945 was taken prisoner by the Americans, from which he was not released until April 1946.

The estate

With the support of the Prussian Sea Trade Foundation, the extensive archive (around 100,000 black and white photographs and over 1.3 million negatives) was acquired in February 1989. A representative part of the estate was digitised in 2013, supported by the Digitalization Service of the State of Berlin. Around 8,000 photos are already accessible online.

Text from the Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin website [Online] Cited 20/05/2021 translated from the German by Google Translate

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]

May 14, 1941

After a few hours, the men left the scene under police custody and had to board requisitioned buses for transfer to the Austerlitz station.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

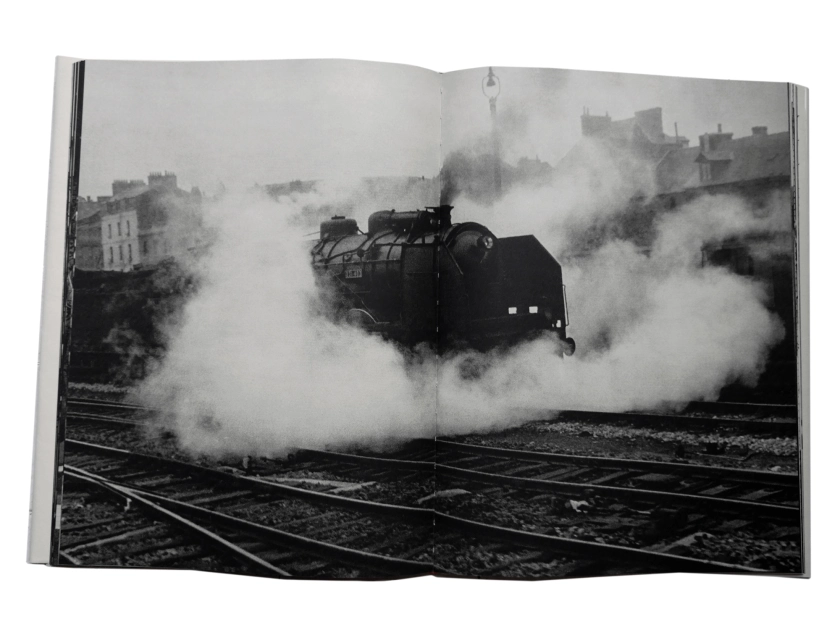

Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps]

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps] (detail)

May 14, 1941

The 3,710 men arrested in Paris at the various summons were transferred to the Austerlitz station to be interned in the Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande camps. Four convoys of passenger wagons are formed, two convoys with 2140 men to the camp of Beaune-la-Rolande and two convoys with 1570 men to that of Pithiviers. These convoys arrive on the afternoon of May 14.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]

May 14, 1941

Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station. His presence in the photos in this roundup shows that he followed and supervised the entire roundup.

Theodor Dannecker (German, 1913-1945)

Theodor Dannecker (German, 27 March 1913 – 10 December 1945) was an SS-captain (Hauptsturmführer), and an associate of Adolf Eichmann. As a specialist on Nazi anti-Jewish policies (Judenberater), he was one of those who orchestrated the Final Solution in several countries during the World War II genocide of European Jews in what became known as the Holocaust … In December 1945, Dannecker was arrested by the United States Army, and, on 10 December, he committed suicide in Bad Tölz. …

From September 1940 until July 1942, Dannecker was leader of the Judenreferat at the SD office in Paris, where he ordered and oversaw round ups by French Police. More than 13,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp where most died in the Final Solution. …

Dannecker developed under Eichmann into one of the SS’s most ruthless and experienced experts on the “Jewish Question”, and his involvement in the genocide of European Jewry was one of primary responsibility. A passage from a 1942 report by Dannecker illustrates how the “Jewish Question” was handled in France:

“Subject: Points for the discussion with the French State Secretary for Police, Bousquet… The recent operation for arresting stateless Jews in Paris has yielded only about 8,000 adults and about 4,000 children. But trains for the deportation of 40,000 Jews, for the moment, have been put in readiness by the Reich Ministry of Transport. Since the deportation of the children is not possible for the time being, the number of Jews ready for removal is quite insufficient. A further Jewish operation must therefore be started immediately. For this purpose Jews of Belgian and Dutch nationality may be taken into consideration, in addition to the former German, Austrian, Czech, Polish and Russian Jews who have so far been considered as being stateless. It must be expected, however, that this category will not yield sufficient numbers, and thus the French have no choice but to include those Jews who were naturalised in France after 1927, or even after 1919.”1

Text from the Wikipedia website

1/ “Eichmann trial – The District Court Sessions”. Nizkor Project. 9 May 1961. Retrieved 23 December 2013

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station] (detail)

May 14, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The photos were taken the day after the raid at the Pithiviers and Beaune-la Rolande camps]

May 15, 1941

The photos were taken the day after the raid at the Pithiviers and Beaune-la Rolande camps. The men had to settle in cold and unsanitary barracks under construction. The straw that will serve as mattresses in the bedsteads is still outside the barracks.

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp]

May 15, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp] (detail)

May 15, 1941

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

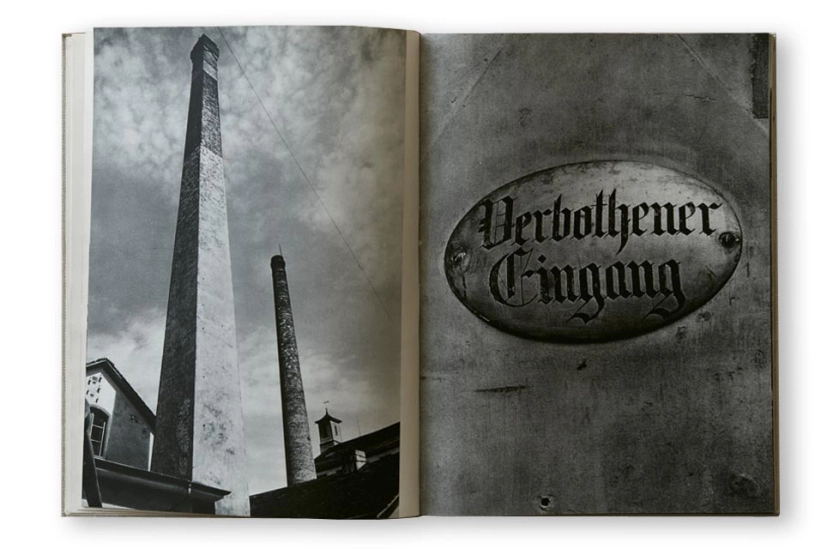

Untitled [Green Ticket Roundup, the next day at the Pithiviers camp. The black hut can be seen where the Vel d’Hiv raids will be recorded in 1942]

May 15, 1941

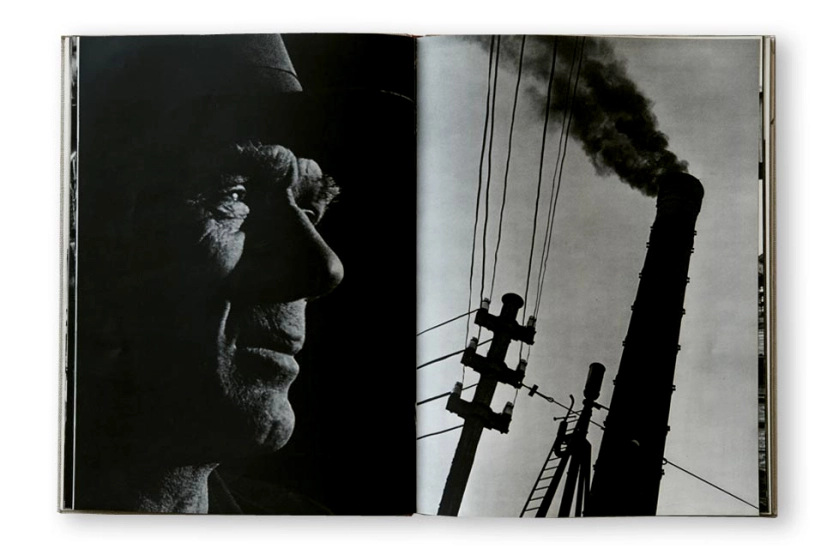

Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992)

Untitled [The day after the roundup of the Billet Vert, a French gendarme posted on a watchtower in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp]

May 15, 1941

The gendarme to the left of the photo, posted in a watchtower, monitoring the Beaune-la-Rolande camp, is the emblematic photo from the film Nuit et Brouillard, censored when it was released in 1955.

Nuit Et Brouillard (Night and Fog)

Alain Resnais

1955

Holocaust, Hebrew Sho’ah, Yiddish and Hebrew Ḥurban (“Destruction”), the systematic state-sponsored killing of six million Jewish men, women, and children and millions of others by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II. The Germans called this “the final solution to the Jewish question.” The word Holocaust is derived from the Greek holokauston, a translation of the Hebrew word ‘olah, meaning a burnt sacrifice offered whole to God. This word was chosen because in the ultimate manifestation of the Nazi killing program – the extermination camps – the bodies of the victims were consumed whole in crematoria and open fires.

Memorial de la Shoah

17, rue Geoffroy l’Asnier

75004 Paris

Phone: + 33 (0)1 42 77 44 72

Opening hours:

Sunday – Friday 10am – 6pm

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men are parked in the stands upstairs]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men are parked in the stands upstairs]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.3.rafle-billet-vert_intccca7rieur-du-gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men peer outside the upper windows of the gymnasium]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men peer outside the upper windows of the gymnasium]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.4.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.28.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/184.5.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail1.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Inside the Japy Gymnasium, Paris XI, place of arrest of foreign Jews on May 14, 1941]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Inside the Japy Gymnasium, Paris XI, place of arrest of foreign Jews on May 14, 1941]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.1.rafle-billet-ver_intccca7rieur-du-gymnase-japy.jpg?w=650&h=941)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.10.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=650&h=963)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: relatives, often wives and their children, are asked to separate from the summoned men]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.10.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=650&h=427)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.14.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: some men still arrive carrying their summons]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.14.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail-1.jpg?w=650&h=829)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: families waiting to hand over the suitcases to their loved ones]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy gymnasium: families waiting to hand over the suitcases to their loved ones]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/182.23.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men peer outside the upper windows of the gymnasium]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Japy Gymnasium: the arrested men peer outside the upper windows of the gymnasium]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.4.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.7.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=650&h=967)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The inhabitants of the district discover the fate of their now captive neighbours]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.7.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=650&h=967)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.9.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.11.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=650&h=964)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.11.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=650&h=677)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.25.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Arrested men leave the gymnasium by bus for Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.25.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Men boarding a train at Austerlitz station for the Loiret camps]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/183.28.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/184.5.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Theodor Dannecker oversees the transfer of the rounded up Jews to the Austerlitz station]' May 14, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/184.5.rafle-billet-vert_gymnase-japy-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The photos were taken the day after the raid at the Pithiviers and Beaune-la Rolande camps]' May 15, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The photos were taken the day after the raid at the Pithiviers and Beaune-la Rolande camps]' May 15, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/186.1.rafle-billet-vert_lendemain-de-la-rafle-au-camp.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp]' May 15, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp]' May 15, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/186.7.rafle-billet-vert_lendemain-de-la-rafle.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp]' May 15, 1941 (detail) Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the raid, the men arrested at the Pithiviers camp]' May 15, 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/186.7.rafle-billet-vert_lendemain-de-la-rafle-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Green Ticket Roundup, the next day at the Pithiviers camp. The black hut can be seen where the Vel d'Hiv raids will be recorded in 1942]' May 15, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [Green Ticket Roundup, the next day at the Pithiviers camp. The black hut can be seen where the Vel d'Hiv raids will be recorded in 1942]' May 15, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/186_10.rafle-du-billet-vert_lendemain-au-camp-pithiviers_vue-baraque-noire-oocc81-seront-enregistrccca7s-en-1942-raflccca7s-du-vel-dhiv-c-mccca7morial-de.jpg?w=840)

![Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the roundup of the Billet Vert, a French gendarme posted on a watchtower in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp]' May 15, 1941 Harry Croner (German, 1903-1992) 'Untitled [The day after the roundup of the Billet Vert, a French gendarme posted on a watchtower in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp]' May 15, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/05/187_1.rafle-du-billet-vert_lendemain-de-la-rafle_gendarme-francais-postccca7-sur-un-mirador-du-camp-de-beaune-la-rolande-c-mccca7morial-de-la-shoah-2.jpg?w=840)

![Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-h.jpg?w=840)

![Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-c.jpg?w=650&h=634)

![Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-d.jpg?w=650&h=620)

![Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 (detail) Andrew Rumann. 'Untitled [Departure from Circular Quay, Sydney for Fremantle and Singapore]' 1941 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-d-detail.jpg?w=650&h=620)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Encampment]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Encampment]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-j.jpg?w=840)

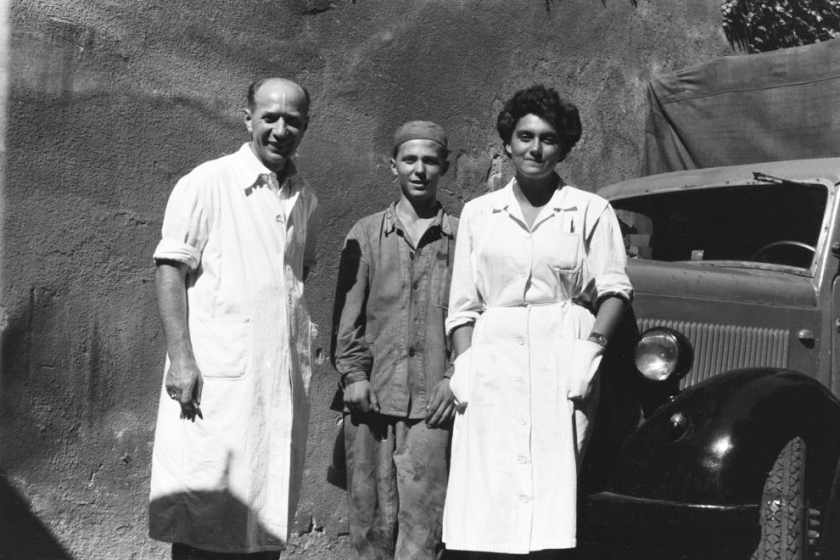

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Women standing in front of an American Red Cross sign]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Women standing in front of an American Red Cross sign]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-i.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-k.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Post Exchange No. 2]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-k-detail.jpg?w=650&h=651)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Taking out the rubbish]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Taking out the rubbish]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-e.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-f.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-f-detail.jpg?w=650&h=626)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-g.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Transportation Corps US Army BKC*23]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-g-detail.jpg?w=650&h=637)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-a.jpg?w=840)

![Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 (detail) Anonymous photographer (Australian) 'Untitled [Embarkation]' 1942-45 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/embarkation-a-detail.jpg?w=650&h=635)

![Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019) 'Untitled [Budapest crowd]' 1949 Joyce Evans (Australian, 1929-2019) 'Untitled [Budapest crowd]' 1949](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/08/joyce-evans-budapest-crowd-1949-web.jpg?w=650&h=586)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-autoritratto-zurigo-1927-web.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-nellufficio-della-fonderia-web.jpg?w=650&h=869)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/tuggener-navy-cut-web.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-laboratorio-di-ricerca-web.jpg?w=650&h=939)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/tuggener-forgeron-dans-une-fabrique-de-wagons-web.jpg?w=650&h=898)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=650&h=879)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=650&h=953)

You must be logged in to post a comment.