Exhibition dates: 21st October 2017 – 28th January 2018

Curator: Martin Gasser

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

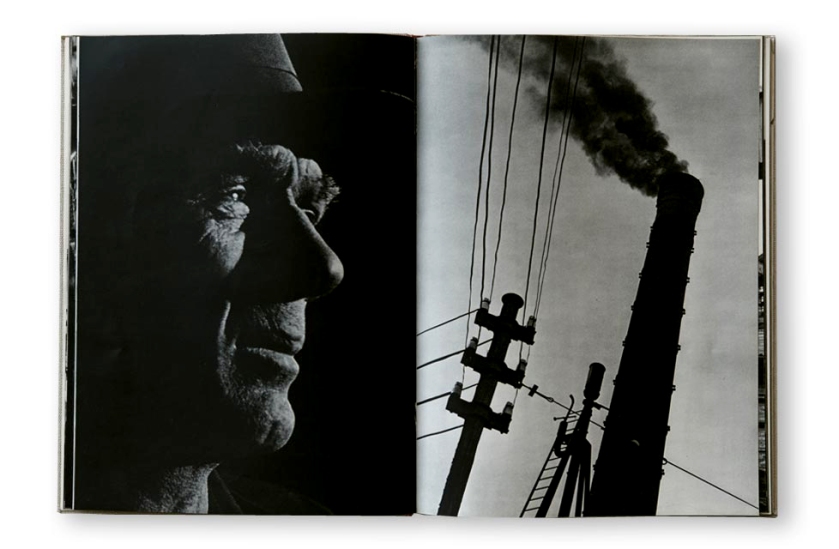

Fabrik (Factory) (book cover)

1943

Rotapfel Verlag, Erlenbach-Zurich

Rare magician, strange alchemist, tells stories through visuals

I am indebted to James McArdle’s blog posting “Work” on his excellent On This Date In Photography website for alerting me to this exhibition, and for reminding me of the work of this outstanding artist, Jakob Tuggener.

The short version: Jakob Tuggener was a draftsman before he became an artist, studying poster design, typography, photography and film. “In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, Tuggerer’s book Fabrik (Factory) appeared. At first glance, the series of 72 photographs without a text contained therein seems to depict a kind of history of industrialisation – from the rural textile industry to mechanical engineering and high-voltage electrical engineering to modern power plant construction in the mountains. An in-depth reading, however, shows that Tuggener’s film-associative series of photographs simultaneously points to the destructive potential of unrestrained technological progress, as a result of which he sees the then raging World War, and for which the Swiss arms industry produced unlimited weapons. Tuggener was ahead of his time with the book conceived according to the laws of silent film.” (Press release)

Fabrik, subtitled Ein Bildepos der Technik (“Epic of the technological image” or “A picture of technology”) pictures the world of work and industry, and “is considered a milestone in the history of the photo book.” It uses expressive visuals (actions, appearances and behaviours; movements, gestures and details – Tuggener loves the detail) to tell a subjective story, that of the relationship between human and machine. While the book was well ahead of its time, and influenced the early work of that famous Swiss photographer Robert Frank, it did not emerge out of a vacuum and is perhaps not as revolutionary as some people think. Nothing ever appears out of thin air.

“German photographer Paul Wolff, often working in collaboration with Alfred Tritschler, produced a number of exceptional photo books through the 1920s and ’30s, at a time when Constructivism and the Bauhaus influenced many with visions “of an industrialized and socialized society” that placed Germany at “the forefront of European photography” (Martin Parr and Gerry Badger. The Photobook: A History Volume I, Phaidon Press, 2005, p. 86). Arbeit! (1937) is particularly noted for its architectural framing and lighting of massive machinery, its striking portraits of factory workers, and is frequently aligned with works such as Lewis Hine’s Men at Work (1932) and Albert Renger-Patzsch’s Eisen und Stahl (Iron and Steel) (1931).” (Anonymous. “Arbeit!,” on the Bauman Rare Books website [Online] Cited 03/02/2022)

François Kollar’s project La France travail (Working France) (1931-1934), E. O. Hoppé’s Deutsche Arbeit (1930), Heinrich Hauser’s Schwarzes Revier (Black Area) (1930) and Germaine Krull’s Metal (1928) all address the profound social and economic tensions that preceded the Second World War, through an avant-garde photography in the style of “New Vision” and “New Objectivity” – that is, through objective photographs that question common rules of composition, avoiding the more obvious ways subjects would have been photographed at the time. Obscure angles and perspectives abound in these striking photobooks, making their clinical, objective fervour “the great persuaders” of the 1930s and 40s, Modernist and propaganda books of their time.

What made Tuggener so different was the uncompromising subjectiveness of his work, “photographing the two worlds, privilege and labour.” His direct, strong images of factories and high society use wonderful form, light, and shadow to convey their message, never loosing sight of the human dimension, for they shift “our angle from the boss’ POV [point of view] to those unable to get any respite or distance from the situation,” that of the workers. They are a piece of time and human history, which gets closer to the lived reality of the factory floor, than much of the work of his predecessors. Tuggener portrays the mundanity of the “operational sequence” (la chaîne opératoire) of the machine, where the human becomes the oil used to grease the cogs of the ever-demanding “mechanical monsters.” (See Evan Calder Williams’ “Rattling Devils” quotations below)

Tuggener then adds to this new way of seeing which recorded the multiplicity of his points of view – “a modern new style of photography showing not just how things looked, but how it felt to be there” – through the sequencing of the images, which can be seen in the wonderfully combined double pages of the Fabrik book layouts below. Take for example, the photograph that is on the dust jacket, a portrait of a middle-aged worker with a grave look on his face that says, “why the hell are you taking my photograph, why don’t you just f… off.” In the book, Tuggener pairs this image with a whistle letting off steam, a metaphor for the man’s state of being. Tuggener creates these most alien worlds from the inside out, worlds which are grounded in actual lived experience – the little screws lying in the palm of a blackened hand; Navy Cut cigarettes amongst steel artefacts; man being consumed by machine; man being dwarfed by machine; man as machine (the girl paired opposite the counting machine); the Frankenstein scenario of the laboratory (man as monster, machine as man); the intense, feverish eyes of the worker in Heater on electric furnace (the machine human as the devil); and the surrealism of a small doll among the serried ranks of mass destruction, facing the opposition, the opposing lined face of an older worker. This is the stuff of alchemy, the place where art challenges life.

“As Arnold Burgaurer cogently states in his introduction, Tuggener is a jack-of-all-trades: he exhibits, ‘the sharp eye of the hunter, the dreamy eye of the painter; he can be a realist, a formalist, romantic, theatrical, surreal.’ Tuggener’s moves effortlessly between large-format lucidity and grainy, blurred impressionism, in a book that is a decade ahead of its time.” (Martin Parr and Gerry Badger. The Photobook: A History Volume I, Phaidon Press, 2005, p. 144.)

James McCardle observes that, “the meaning of Fabrik is left to the viewer to discover between its pictures, its glimpses of an overwhelming industrial whole; it is essentially filmic on a cryptic film-noir level, a revelation to Frank.” Tuggener’s influence on the early work of Robert Frank can be seen in a sequence from the book Portfolio: 40 Photos 1941/1946 by Robert Frank that was republished by Steidl in 2009 (see below). “Like Tuggener, Frank tackles the task of seemingly incongruous subject matter and finds a harmony through edit and assembly. Again and again throughout this portfolio, Frank is not just trying to show his prowess in making images but in pairing them. They define conflicts in life.” Pace Tuggener. At Frank’s suggestion, Tuggener’s work appeared in both Edward Steichen’s Post-War European Photography and in The Museum of Modern Art’s seminal exhibition, The Family of Man, the latter an essentially humanist exhibition which took the form of a photo essay celebrating the universal aspects of the human experience.

McCardle goes onto suggest that Fabrik, as a photo book, was a model for Frank’s Les Américains: The Americans published fifteen years later in Paris by Delpire, 1958. On this point, we disagree. While his early work as seen in Portfolio: 40 Photos 1941/1946 may have been heavily influenced by Tuggener’s photo book, by the time Frank came to compose Les Américains (for that is what The Americans is, a composition) his point of view had changed, as had that of his camera. While The Americans has many formal elements that can be seen in the construction of the photographs, they also have an element of jazz that would have been inconceivable to Tuggener at that time. Grainy film, strange angles, lighting flare, street lights, night time photography, jukeboxes and American flags portray the American dream not so much from the vantage point of a knowing insider (as Tuggener was) but as a visitor from another planet. Not so much alienating world (man as machine) as alien world, picturing something that has never been recognised before. These are two different models of being. While both are photo books and both pair images together in sequences, Frank had moved on to another point of view, that of an “invalid” outsider, and his photo book has a completely different nature to that of Tuggener’s Fabrik.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,366

Many thankx to Fotostiftung Schweiz for allowing me to publish some of the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

For Jakob Tuggener, whose works can be seen within the context of social documentary photography, the individual and the industrial boom of the 19th and 20th centuries were central themes. His often somber, black and white photographs seem to confront this new world with a sense of fear as well as admiration. Will technology help relieve us of physically hard labour or replace us altogether? Tuggener owes his renown to his photo book Fabrik (Factory) that was published in 1943. With an aesthetic approach that was unique for his time, Tuggener explores in his photographic essay the relationship between humans and the perceived threat as well as progress of technology. The labourers depicted are grave, their faces worn marked by deep folds, while a factory building in the background stands strong, enveloped in a vaporous cloud. This “Pictorial Epic of Technology,” as Tuggener himself described it, is today considered a milestone in the history of photography books.

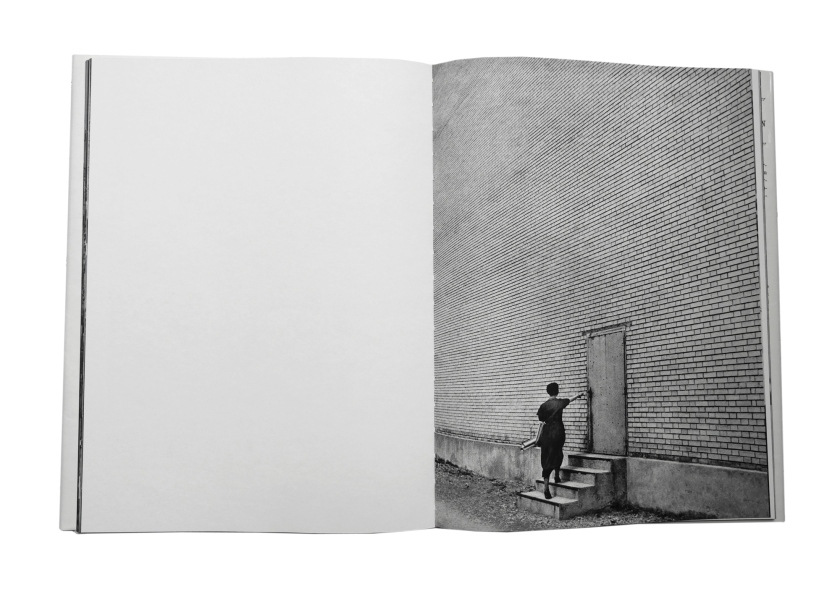

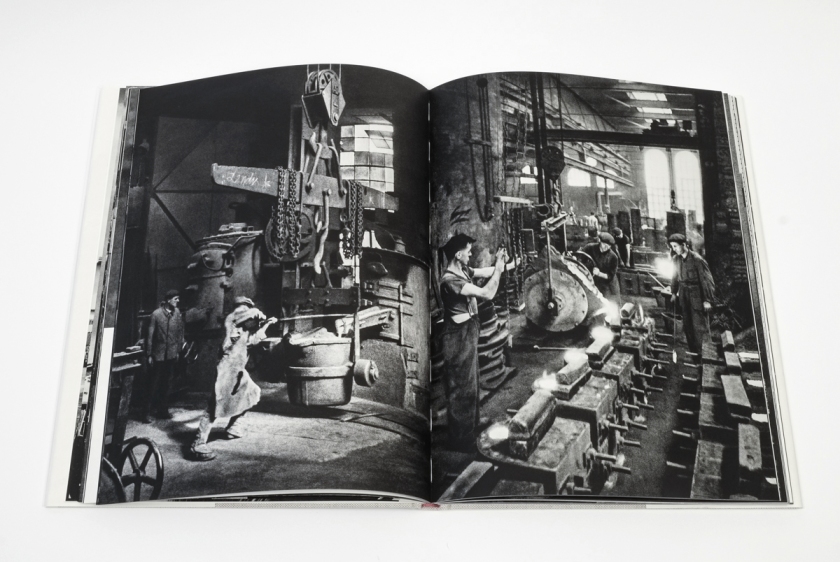

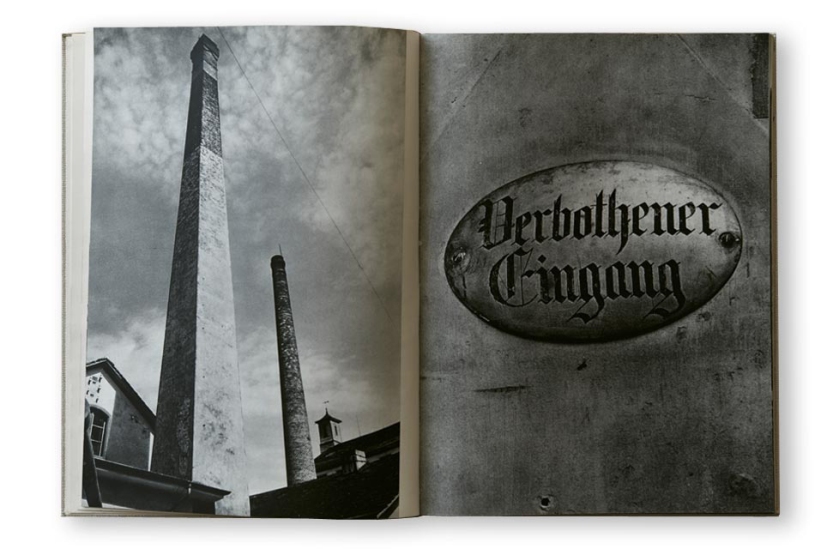

Jakob Tuggener (1904-1988) Page layout from the book Fabrik 1943

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Steam whistle, Steckborn artificial silk factory

1938

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Selection from the book Portfolio: 40 Photos 1941/1946 by Robert Frank (Steidl, 2009)

The ‘weightless’ and the ‘grounded’ are two opposing themes that Frank repeatedly uses to move us through this sequence. Three radio transistors in a product shot float into the sky while a music conductor, his band and a church steeple succumb to gravity on the facing page. Even in this image Frank shifts focus to the sky and beyond – the weightless. When he photographs rural life, the farmers heft whole pigs into the air and another carries a huge bale of freshly cut grain which seems featherlight but for the woman trailing behind with hands ready to assist.

Considering this work was made while fascism was on the move through Europe, external politics is felt through metaphor. A painted portrait of men in uniform among a display of pots and pans for sale faces a brightly polished cog from a machine – its teeth sharp and precise. In another pairing, demonstrators waving flags in the streets of Zurich face a street sign covered with snow and frost, a Swiss flag blows in the background. in yet another of a crowd of spectators face the illuminated march of a piece of machinery – its illusory shadow filling in the ranks. These pairings feel under the influence of Jakob Tuggener, whose work Frank certainly knew. Like Tuggener, Frank tackles the task of seemingly incongruous subject matter and finds a harmony through edit and assembly.

Again and again throughout this portfolio, Frank is not just trying to show his prowess in making images but in pairing them. They define conflicts in life. One boy struggles to climb a rope while a ski jumper is frozen in flight. Fisherman bask in sunlight while two pedestrians are caught in blinding snowfall.

Text from the SB4 Photography and Books website December 14, 2009

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Autoritratto, Zurigo (Self-portrait, Zurich)

1927

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Budenzauber (Charm of the Attic Room) Jakob Tuggener with friends

1935

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Plant entrance, Oerlikon Machine Factory

1934

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Work in the boiler

1935

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Running girl in the Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon

1934

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Façade, Oerlikon Machine Factory

1936

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (1904-1988) Page layout from the book Fabrik 1943

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Nell’ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon (In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory)

1937

From Fabrik 1933-1953

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

“Above all, the contrast between the brilliantly lit ballroom and the dark factory hall influenced the perception of his artistic oeuvre,” [curator] Martin Gasser explains. “Tuggener also positioned himself between these two extremes when he stated: ‘Silk and machines, that’s Tuggener’. In reality, he loved both: the wasteful luxury and the dirty work, the enchanting women and the sweaty labourers. For him, they were both of equal value and he resisted being categorised as a social critic who pitted one world against the other. On the contrary, these contrasts belonged to his conception of life and he relished experiencing the extremes – and the shades of tones in between – to the most intense degree.”

“Jakob Tuggener’s ‘Fabrik’, published in Zurich in 1943, is a milestone in the history of the photography book. Its 72 images, in the expressionist aesthetic of a silent movie, impart a skeptical view of technological progress: at the time the Swiss military industry was producing weapons for World War II. Tuggener, who was born in 1904, had an uncompromisingly critical view of the military-industrial complex that did not suit his era. His images of rural life and high-society parties had been easy to sell, but ‘Fabrik’ found no publisher. And when the book did come out, it was not a commercial success. Copies were sold at a loss and some are believed to have been pulped. Now this seminal work, which has since become a sought-after classic, is being reissued with a contemporary afterword. In his lifetime, Tuggener’s work appeared – at Robert Frank’s suggestion – in Edward Steichen’s ‘Post-War European Photography’ and in The Museum of Modern Art’s seminal exhibition, ‘The Family of Man’, in whose catalogue it remains in print. Tuggener’s death in 1988 left an immense catalogue of his life’s work, much of which has yet to be shown: more than 60 maquettes, thousands of photographs, drawings, watercolours, oil paintings and silent films.”

Book description on Amazon. The book has been republished by Steidl in January, 2012.

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Tornos Machine-tool Factory, Moutier

1942

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO) [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)]

1940

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Pressure pipe, Vernayaz

1938

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

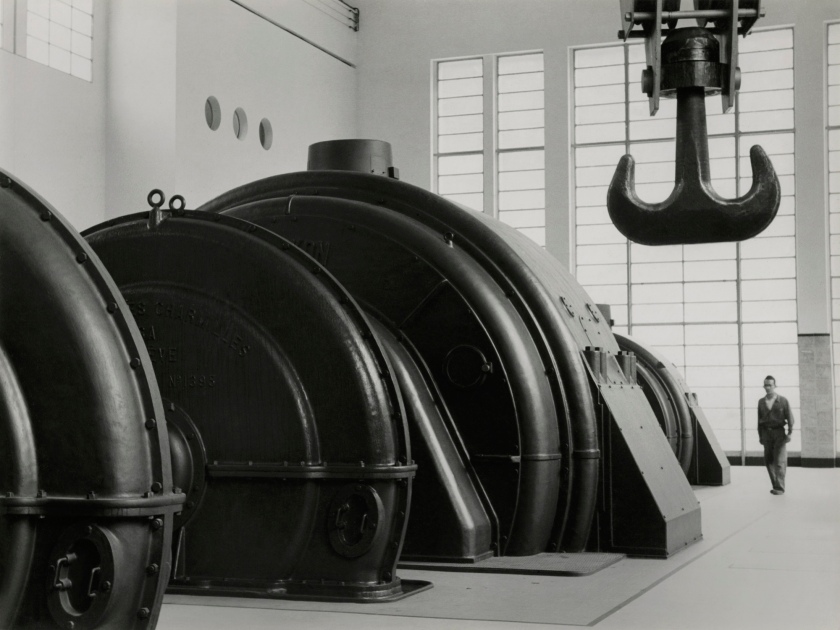

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Grande Dixence power station

1942

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener Foundation

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon (Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory)

1941

From Fabrik 1933-1953

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Heater on electric furnace (detail)

1943

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Heater on electric furnace

1943

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Worker, Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon

1940s

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener Foundation

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

“Amore”, Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon

1940s

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener Foundation

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Weaving mill, Glattfelden

1940s

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener Foundation

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Lathe, Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon

1949

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Lathe, Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (detail)

1949

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Jacob Tuggener at the popular pavillion Montpellier manufactures an epic of industrial photographs of workers’ portraits

Montpellier magazine

1943

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory]

1949

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Untitled (Arms of work)

c. 1947

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (1904-1988) is one of the exceptional phenomena of Swiss photography. His personal and expressive recordings of glittering celebrations of better society are legendary, and his 1943 book Fabrik (Factory) is considered a milestone in the history of the photo book. At the centre of the exhibition “Machine time” are photographs and films from the world of work and industry. They not only reflect the technical development from the textile industry in the Zurich Oberland to power plant construction in the Alps, but also testify to Tuggener’s lifelong fascination with all sorts of machines: from looms to smelting furnaces and turbines to locomotives, steamers and racing cars. He loved her noise, her dynamic movements and her unruly power, and he artistically transposed them. At the same time, he observed the men and women who keep up the motor of progress with their work – not without hinting that one day machines might dominate people.

Machine time

Jakob Tuggener knew the world of factories like no other photographer of his time, having completed an apprenticeship as a draftsman at Maag Zahnräder AG in Zurich and then worked in their design department. Through the photographer Gustav Maag he was also introduced to the technique of photography. However, as a result of the economic crisis in the late 1920s, he was dismissed, after which he fulfilled his childhood dream of becoming an artist by studying at the Reimannschule in Berlin. For almost a year he dealt intensively with poster design, typography and film and let himself be carried away with his camera by the dynamics of the big city.

After returning to Switzerland in 1932, he began working as a freelancer for the Maschinenfabrik Oerlikon (MFO), especially for their house newspaper with the programmatic title Der Gleichrichter (The Rectifier). Although the company already employed its own photographer, he was entrusted with the task of developing a kind of photographic interior view of the company. This was intended to bridge the gap between workers and office workers on the one hand and management on the other. By the end of the 1930s, in addition to multi-part reports from the production halls, as well as portraits of “members of the MFO family”, one-sided, album-like series of unnoticed scenes from everyday factory life appeared. From 1937 Tuggener also created a series of 16mm short films – always black and white, silent, and representing the tension between fiction and documentation. This includes, for example, the drama about death and transience (Die Seemühle (The Sea mill), 1944), which was influenced by surrealism and staged by Tuggener with amateur actors in a vacant factory on the shores of Lake Zurich. or the cinematic exploration of the subject of man and machine (Die Maschinenzeit (The Machine Time), 1938-1970). This ties in with the earlier book maquette of the same name and transforms it into a moving, immediately perceptible, but also fleeting vision of the Tuggenean machine age.

In 1943, in the middle of the Second World War, Tuggerer’s book Fabrik (Factory) appeared. At first glance, the series of 72 photographs without a text contained therein seems to depict a kind of history of industrialisation – from the rural textile industry to mechanical engineering and high-voltage electrical engineering to modern power plant construction in the mountains. An in-depth reading, however, shows that Tuggener’s film-associative series of photographs simultaneously points to the destructive potential of unrestrained technological progress, as a result of which he sees the then raging World War, and for which the Swiss arms industry produced unlimited weapons. Tuggener was ahead of his time with the book conceived according to the laws of silent film.1 Neither his uncompromisingly subjective photography nor his critical attitude matched the threatening situation in which Switzerland was called to unity and strength under the slogan “Spiritual Defense”.

Although the book was not commercially successful, Tuggener’s Fabrik was a great artistic success and continued to explore the issues of work and industry. He produced two more book maquettes: Schwarzes Eisen (Black Iron) (1950) and Die Maschinenzeit (The Machine Time) (1952). They can be understood as a kind of continuation of the published book, which the journalist Arnold Burgauer described as a “glowing and sparkling factual and accountable report of the world of the machine, of its development, its possibilities and limitations.” In the mid-1950s, on the threshold of the computer age, Tuggener’s classic “machine time” came to an end. On the one hand, the mechanical processes that had so fascinated Tuggener evaded his eyes. On the other hand, he could not or did not want to make friends with the idea that one day even a human heart could be replaced by a machine.

Portrayer of opposites

As early as 1930 in Berlin, Tuggener had begun to take pictures of the then famous Reimannschule balls. He was fascinated by the tingling erotic atmosphere of these occasions, and he found photography in sparsely lit rooms a great challenge. Back in Zurich, he immediately plunged into local nightlife to surrender to the splendour and luxury of mask, artist and New Year’s balls. Again and again he let himself be abducted by elegant ladies with their silk dresses, their necklines, bare back or shoulders in a glittering fairytale world, whose mysterious facets he sought to fathom with his Leica. Although Tuggener’s ball recordings were only perceived by a small insider audience for a long time, many quickly saw him as a “masterful portrayer of our world of stark contrasts,” a world torn between a brightly lit ballroom and gloomy factory hall. Tuggener also positioned himself between these extremes when he stated, “Silk and machines, that’s Tuggener.” Because he loved both the lavish luxury and the dirty work, the jewelled women and the sweaty men. He felt that he was equal and resisted being classified as a social critic.

In whatever world he moved, Jakob Tuggener did it with the elegance of a grand seigneur [a man whose rank or position allows him to command others]. He was an eye man with a casual, loving look for the inconspicuous, the superficial incident; not just a sensitive picture-poet, but the “photographische Dichter römisch I,” as he used to call himself self-confidently. Critic Max Eichenberger wrote of the Fabrik photographs: “Tuggener is able to make factory photographs that reveal not only a painter, but also a poet, and a rare magician and strange alchemist – lead, albeit modestly turned into gold.”

The exhibition Jakob Tuggener – Maschinenzeit includes vintage and later prints from the early 1930s to the late 1950s, which for the most part come from the photographers estate. In an adjoining room the exhibition will also feature a selection of his 16mm short films from the years 1937-1970, which revolve around the topic of “man and machine” in various ways. These films were newly digitised specifically for the exhibition (in collaboration with Lichtspiel / Cinematheque Bern).

Press release from Fotostiftung Schweiz

1/ The story in silent film is best told through visuals (such as actions, appearances and behaviours). Focus on movements and gestures, and borrow from dance and mime. Large, exaggerated motions translate well to silent films, but balance these also with subtlety (ie. a raised eyebrow, a quivering lip – especially when paired with a close-up shot).

Karlanna Lewis. “8 Tips for Making Silent Movies,” on the Raindance website June 1, 2014 [Online] Cited 03/02/2022

Jakob Tuggener (1904-1988) Page layouts from the book Fabrik 1943

Extracts from Shard Cinema by Evan Calder Williams London: Repeater Books, 2017

“All gestures are perhaps inhuman, because they enact that hinge with the world, forging a bridge and buffer that can’t be navigated by words or by actions that feel like purely one’s own. In Vilém Flusser’s definition, a gesture is “a movement of the body or of a tool connected to the body for which there is no satisfactory causal explanation” – that is, it can’t be explained on its own isolated terms.26 The factory will massively extend this tendency, because the “explanation” lies not in the literal circuit of production but in the social abstraction of value driving the entire process yet nowhere immediately visible. We might frame the difficulty of this imagining with the concept of “operational sequence” (la chaîne opératoire), posed by French archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan, which designates a “succession of mental operations and technical gestures, in order to satisfy a need (immediate or not), according to a preexisting project.”25

26. Vilém Flusser, Gestures (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), p. 2.

27. Catherine Perlès, Les Industries Lithiques Taillées de Franchthi, Argolide: Presentation Generate et Industries Paleolithiques (Terre Haute: Indiana University Press, 1987), p. 23.

“Which is to say: we build factories. And in those factories, the process of the exteriorization of memory and muscle becomes almost total, as “the hand no longer intervenes except to feed or to stop” what Leroi-Gourhan, like Larcom, will call “mechanical monsters,” “machines without a nervous system of their own, constantly requiring the assistance of a human partner.”30 But along with engendering the panic of becoming caregiver to the inanimate, this also poses the problem of animation in an unprecedented way. Because if a “technical gesture is the producer of forms, deriving them from inert nature and preparing them for animation,” the factory constitutes us in a different network of the animated and animating.31 It’s a network that can be seen in those writings of factory workers, with their distinct sense of not just preparing those materials but becoming the pivot that eases, smooths, and guides the links of an operational sequence. In particular, a worker functions as the point of compression and transformation between tremendous motive force and products made whose regularity must be assured. The human becomes the regulator of this process, the assurance of an abstract standardization.”

30 André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993), p. 246

31. Ibid., p. 313

“… what I’m sketching here in this passage through scattered materials of the century prior to filmed moving images is something simpler, a small corrective to insist that by the time cinema was becoming a medium that seemed to offer a novel form of mechanical time, motion, and vision, one that historians and theorists will fixate on as the unique province and promise of film, many of its viewers had themselves already been enacting and struggling against that form for decades, day in, day out. The point is to place the human operator back in the frame, to ask after those who tended the machine before it was available as a spectacle, and to listen to how they understood what they were tangled in the midst of. But this is neither a humanist gesture of assuring the centrality of the person in the mesh that holds them nor a historical rejoinder to the forgetting and active dismissal of many of these personal accounts. Rather, it’s an effort to show how only with the operator’s experience made central can we see the real historical destruction of such illusions of centrality and, in their place, the novel construction of the human as tender and mender of a flailing inhuman net, the pivot who forms the connective tissue that enacts the lethal animation around her. In short, to see how the real subsumption of labor to capital is not only a systemic or periodizing concept that marks the historical transformation of discrete activities in accordance with the abstractions of value. It also is the granular description of a lived and bitterly contested process by which those abstractions get corporally and mechanically made and unmade, one which we can understand differently if we shift our angle from the boss’ POV to those unable to get any respite or distance from the situation.”

Excerpt from Evan Calder Williams. “Rattling Devils,” on the Viewpoint Magazine website July 13, 2017 [Online] Cited 29/12/2017

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935 (Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935)

1935

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935 (Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935)

1935

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Hotel Belvédère, Davos, 1944

1944

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Carlton hotel, St. Moritz

Nd

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Palace Hotel, St. Moritz, San Silvestro

1948-49

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Ballo Acs,Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1948

1948

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988)

Ball Nights

From the series Nuits de bal, 1934-1950

Silver gelatin print

© Jakob Tuggener-Stiftung

Fotostiftung Schweiz

Grüzenstrasse 45

CH-8400 Winterthur (Zürich)

Phone: +41 52 234 10 30

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 8pm

Closed on Mondays

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Autoritratto, Zurigo [Self-portrait, Zurich]' 1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-autoritratto-zurigo-1927-web.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Nell'ufficio della fonderia, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [In the foundry office, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-nellufficio-della-fonderia-web.jpg?w=650&h=869)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Navy Cut, Ateliers de construction mécanique Oerlikon (MFO)' [Navy Cut, Machine Shops Oerlikon (MFO)] 1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-navy-cut-web.jpg?w=650&h=872)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Laboratorio di ricerca, fabbrica di costruzioni meccaniche Oerlikon' [Research laboratory, Oerlikon mechanical engineering factory] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-laboratorio-di-ricerca-web.jpg?w=650&h=939)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Forgeron dans une fabrique de wagons de Schlieren' [Blacksmith in a Schlieren wagon factory] 1949](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-forgeron-dans-une-fabrique-de-wagons-web.jpg?w=650&h=898)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=650&h=879)

![Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935 Jakob Tuggener (Swiss, 1904-1988) 'Ballo ungherese, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurigo, 1935' [Hungarian dance, Grand Hotel Dolder, Zurich, 1935] 1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/jakob-tuggener-ballo-ungherese-web.jpg?w=650&h=953)

You must be logged in to post a comment.