November 2021

Celebration!

Recent work

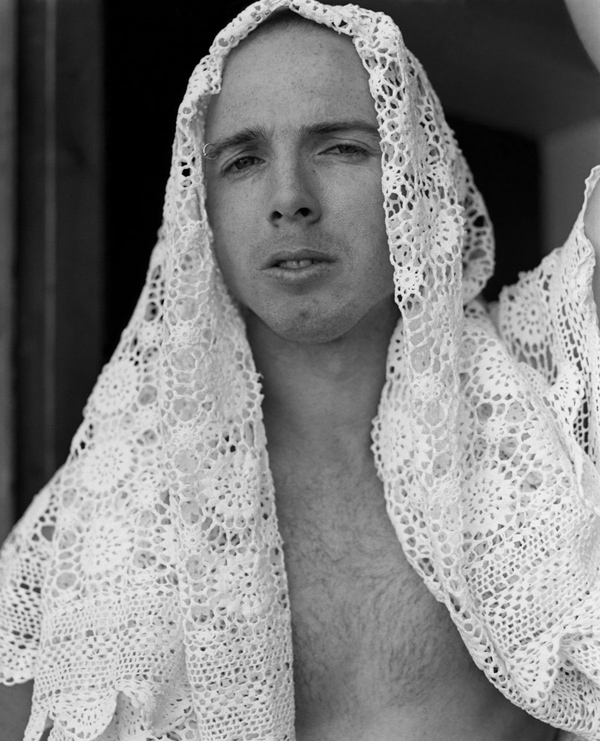

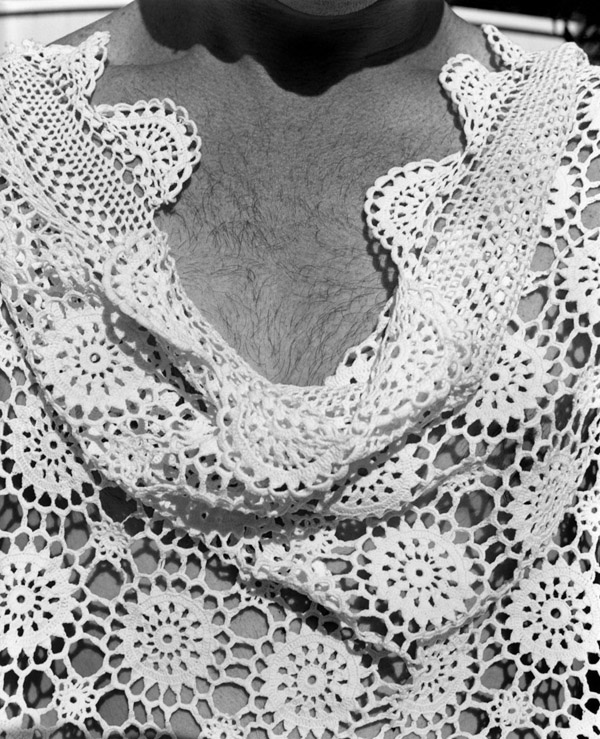

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2021

From the series Resonance

In 2021, I celebrate 30 years of art practice with the creation of a new website, the first to contain all my bodies of work since 1991 (note: more bodies of work still have to be added between 1996-1999).

My first solo exhibition was in a hair dressing salon in High Street, Prahran, Melbourne in 1991, during my second year of a Bachelor of Arts (Fine Art Photography) at RMIT University (formerly Phillip Institute out in Bundoora). Titled Of Magic, Music and Myth it featured black and white medium format photographs of the derelict Regent Theatre and the old Victorian Railway’s Newport Workshops.

The concerns that I had at the time in my art making have remained with me to this day: that is, an investigation into the boundaries between identity, space and environment. Music and “spirit” have always been an abiding influence – the intrinsic music of the world and the spirit of objects, nature, people and the cosmos … in a continuing exploration of spaces and places, using found images and digital and film cameras to record glances, meditations and movement through different environments.

30 years after I started I hope I have learnt a lot about image making … and a lot about myself. I also hope the early bodies of my work are still as valid now as they were when I made them. In the 30 years since I became an artist my concerns have remained constant but as well, my sense of exploration and joy at being creative remains undimmed and an abiding passion.

Now, with ego integrated and the marching of the years I just make art for myself, yes, but the best reason to make art is … for love and for the cosmos. For I believe any energy that we give out to the great beyond is recognised by spirit. Success is fleeting but making art gives energy to creation. We all return to the great beyond, eventually.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Each photograph in this posting links to a different body of work on my new website. Please click on the photographs to see the work.

Unknown photographer

Opening of Marcus Bunyan’s exhibition The Naked Man Fears No Pickpockets at The Photographers’ Gallery and Workshop, Melbourne, 1993 showing at left (behind the crowd) the photograph Richmond Steps 1993

1993

Polaroid

Ian Lobb (Australian, b. 1948)

Marcus 31/8/92 Taken by Ian Lobb at Phillip [Institute]

1992

Polaroid

Jeff Whitehead (Australian)

Marcus in his Fred Perry and Doc Martens with his Mamiya RZ67 on tripod with Pelican case on Jeff’s car, Studley Park, Melbourne

1991-1992

Colour photograph

The only photograph of me with my camera 30 years ago!

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2017-2020

From the series Stones, Vaults, Flowers: Père Lachaise

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2019-2020

From the series A Day in the Tiergarten

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2019

From the series The Night Journey

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2019

From the series Oblique

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Parc de Sceaux

2018

From the series Paris in film

War dreams 2007-2017

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2013-2017

From the series The Shape of Dreams

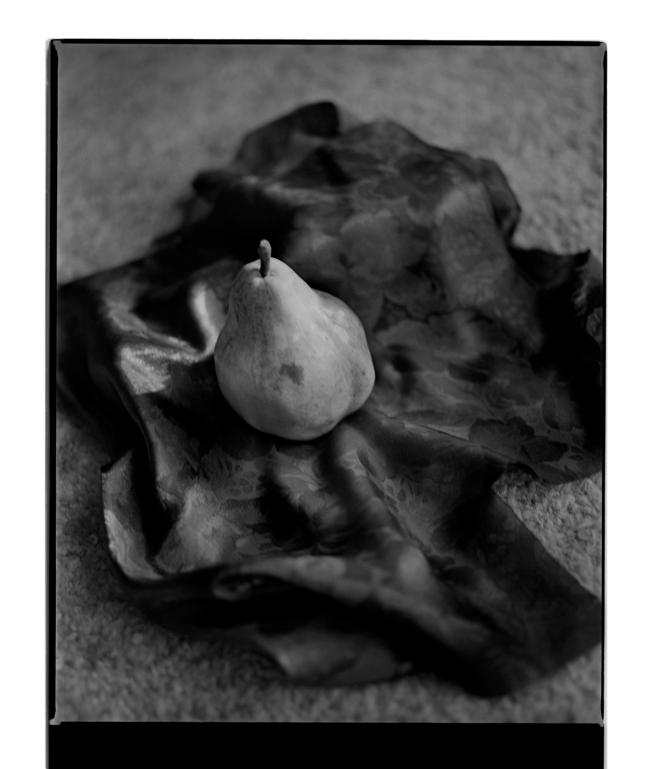

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2015

From the series Too Much of the Air

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2013

From the series upside down

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2011

From the series Vertical

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2011

From the series The Symbolic Order (cartes de visite)

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2010

From the series Missing in Action (red kenosis)

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2010

From the series Missing in Action (dark kenosis)

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2010

From the series Missing in Action (horizontal kenosis)

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2009

From the series There but for the Grace of You Go I

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2009

From the series The Shape of Dreams

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2009

From the series Momentum

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2008

From the series Cut and Thrust

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2007

From the series Drone

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2007

From the series Nebula

Transformations 1996-2008

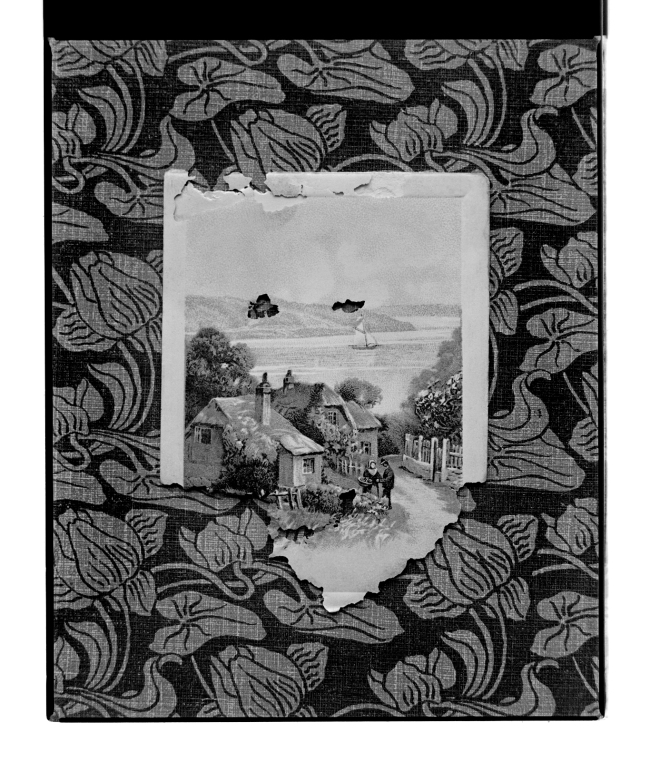

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2008

From the series Discarded Views

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2008

From the series Last Stand

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2007

From the series Wonders Never Cease

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2007

From the series Unearth

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2006

From the series Aporia

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2005

From the series Photos My Mother Sent Me

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2005

From the series No Man’s Land

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2005

From the series Tokern

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2005

From the series Inurtia

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

VV – 09GI and NV – 17EP during a thunderstorm, Albury

2005

From the series Enclosure

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Bedtime

2004

From the series Neo_mort

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2003

From the series Desideratum

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2002

From the series Last Days at Karngara

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2001

From the series The Wrestlers

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Button 2B

2001

From the series D O < R >

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Plane 6

2001

From the series Throw High and Hard

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Untitled

2000

From the series Thirdspace

Black and white archive 1991-1997

PLEASE VIEW THE BLACK AND WHITE ARCHIVE POSTINGS

Marcus Bunyan black and white archive 1991-1997

PLEASE VIEW THE BLACK AND WHITE ARCHIVE POSTINGS

Back to top

![Ian Lobb (Australian, b. 1948) 'Marcus 31/8/92 Taken by Ian Lobb at Phillip [Institute]' 1992 Ian Lobb (Australian, b. 1948) 'Marcus 31/8/92 Taken by Ian Lobb at Phillip [Institute]' 1992](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/11/ian-lobb-marcus-phillip-institute-1992.jpg?w=650&h=649)

You must be logged in to post a comment.