November 2019

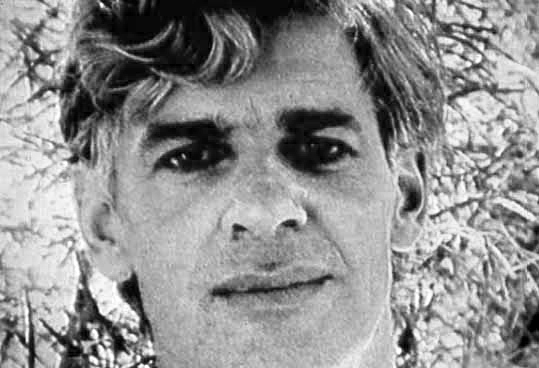

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Self-portrait with punk jacket and The Jesus and Mary Chain T-shirt

1992

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to University of Otago academics Chris Brickell and Judith Collard for inviting me to write a chapter for this important book… about my glorious punk jacket of the late 1980s (with HIV/AIDS pink triangle c. 1989). Aaah, the memories!

Please come along to the Australian launch of the book at Hares Hyenas bookshop (63 Johnston Street, Fitzroy, Melbourne) on Wednesday, November 6, 2019 at 6pm – 7.30pm. The book is to be launched by Jason Smith (Director Geelong Gallery). Click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Marcus

“Gay and lesbian identity (and, by extension, queer identity) is predicated on the idea that, as sexualities, they are invisible, because sexuality is not a visible identity in the ways that race or sex are visible. Only by means of individual expression are gay and lesbian sexualities made discernible.”

Ari Hakkarainen. “‘The Urgency of Resistance’: Rehearsals of Death in the Photography of David Wojnarowicz” 2018

Punk Jacket

I arrived in Melbourne in August 1986 after living and partying in London for 11 years. I had fallen in love with an Australian skinhead boy in 1985. After we had been together for a year and a half together his visa was going to expire and he had to leave Britain to avoid deportation. So I gave up my job, packed up my belongings and went to Australia. All for love.

We landed in Melbourne after a 23-hour flight and I was driven down Swanston Street, the main drag (which in those days was open to traffic) and I was told this was it; this was the centre of the city. Bought at a milk bar, the Australian version of the corner shop, the first thing I ever ate in this new land was a Violet Crumble, the Oz equivalent of a Crunchie. Everything was so strange: the light, the sounds, the countryside.

I felt alienated. My partner had all his friends and I was in a strange land on my own. I was homesick but stuck it out. As you could in those days, I applied for gay de facto partnership status and got my permanent residency. But it did not last and we parted ways. Strange to say, though, I did not go back to England: there was an opportunity for a better life in Australia. I began a photography course and then went to university. I became an artist, which I have now been for over 30 years.

Melbourne was totally different then from the international city of today: no café culture, no big events, no shopping on Sundays, everything shut down early. At first living there was a real culture shock. I was the only gay man in town who had tattoos and a shaved head, who wore Fred Perrys, braces and Doc Martens. All the other gay men seemed to be stuck in the New Romantics era. In 1988 I walked into the Xchange Hotel on Commercial Road, then one of the pubs on the city’s main gay drag, and said to the manager, Craig, ‘I’m hungry, I’m starving, give me a job’, or words to that effect. He thought a straight skinhead had come to rob the place, but he gave me a job, sweet man. He later died of AIDS.

I went to my first Mardi Gras in Sydney the same year, when the party after the parade was in the one pavilion, the Horden at the showgrounds, and there were only 3000 people there. I loved it. Two men, both artists who lived out in Newtown, picked me up and I spent the rest of the weekend with them, having a fine old time. I still have the gift Ian gave me from his company, Riffin Drill, the name scratched on the back of the brass belt buckle that was his present. I returned the next year and the party was bigger. I ventured out to Newtown during the day, when the area was a haven for alternatives, punks and deviants (not like it is now, all gentrified and bland) and found an old second-hand shop quite a way up from the train station. And there was the leather jacket, unadorned save for the red lapels. It fitted like a glove. Somehow it made its way back with me to Melbourne. Surprise, surprise!

Then I started making the jacket my own. Studs were added to the red of the lapel and to the lower tail at the back of the jacket with my initials MAB (or MAD as I frequently referred to myself) as part of the design. A large, Gothic Alchemy patch with dragon and cross surrounded by hand-painted designs by my best mate and artist, Frederick White, finished the back of the jacket. Slogans such as ‘One Way System,’ ‘Oh Bondage, Up Yours!’ and ‘Anarchy’ were stencilled to both arms and the front of the jacket; cloth patches were pinned or studded to the front and sides: Doc Martens, Union Jack, Southern Cross … and Greenpeace. I added metal badges from the leather bar, The Gauntlet, and a British Skins badge with a Union Jack had pride of place on the red lapel. And then there was one very special homemade badge. Made out of a bit of strong fabric and coloured using felt-tip pens, it was attached with safety pins to the left arm. It was, and still is, a pink triangle. And in grey capital letters written in my own hand, it says, using the words of the Latin proverb, ‘SILENCE IS THE VOICE OF COMPLICITY’.

I have been unable to find this slogan anywhere else in HIV/AIDS material, but that is not to say it has not been used. This was my take on the Silence = Death Collective’s protest poster of a pink triangle with those same words, ‘Silence = Death’ underneath, one of the most iconic and lasting images that would come to symbolise the Aids activist movement. Avram Finkelstein, a member of the collective who designed the poster, comments eloquently on the weight of the meaning of ‘silence’: ‘Institutionally, silence is about control. Personally, silence is about complicity.’1 In a strange synchronicity, in 1989 I inverted the pink triangle of the ‘Silence = Death’ poster so that it resembled the pink triangle used to identify gay (male) prisoners sent to Nazi concentration camps because of their homosexuality; the Pink Triangles were considered the ‘lowest’ and ‘most insignificant’ prisoners. It is estimated that the Nazis killed up to 15,000 homosexuals in concentration camps. Only in 2018, when writing this piece, did I learn that Avram Finkelstein was a Jew. He relates both variants of the pink triangle to complicity because ‘when you see something happening and you are silent, you are participating in it, whether you want to or not, whether you know it or not’.2

Finishing the jacket was a labour of love that took several years to reach its final state of being. I usually wore it with my brown, moth-eaten punk jumper, bought off a friend who found it behind a concert stage. Chains and an eagle adorned the front of it, with safety pins holding it all together. On the back was a swastika made out of safety pins, to which I promptly added the word ‘No’ above the symbol, using more safety pins, making my political and social allegiances very clear. Both the jumper and the jacket have both been donated to the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

By 1993 I had a new boyfriend and was at the beginning of a 12-year relationship that would be the longest of my life. We were both into skinhead and punk gear, my partner having studied fashion design with Vivienne Westwood in London. We used to walk around Melbourne dressed up in our gear, including the jacket, holding hands on trams and trains, on the bus and in the street. Australia was then such a conservative country, even in the populated cities, and our undoubtedly provocative actions challenged prevailing stereotypes of masculinity. We wore our SHARP (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice) T-shirts with pride and opposed any form of racism, particularly from neo-fascists.3

Why did we like the punk and skinhead look so much? For me, it had links to my working-class roots growing up in Britain. I liked the butch masculinity of the shaved head and the Mohawk, the tattoos, braces, Docs and Perrys – but I hated the racist politics of straight skinheads. ‘SHARPs draw inspiration from the biracial origins of the skinhead subculture … [they] dress to project an image that looks hard and smart, in an evolving continuity with style ideals established in the middle-to-late 1960s. They remain true to the style’s original purpose of enjoying life, clothes, attitude and music. This does not include blanket hatred of other people based on their skin colour.’4

By the very fact of being a ‘gay’ punk and skinhead, too, I was effectively subverting the status quo: the hetero-normative, white patriarchal society much in evidence in Australia at the time. I was subverting a stereotypical masculinity, that of the straight skinhead, by turning it ‘queer’. Murray Healy’s excellent book, Gay Skins: Class, Masculinity and Queer Appropriation, was critical to my understanding of what I was doing intuitively. Healy looks into the myths and misapprehensions surrounding gay skins by exploring fascism, fetishism, class, sexuality and gender. Queer undercurrents ran through skinhead culture, and shaven heads, shiny DMs and tight Levis fed into fantasies and fetishes based on notions of hyper-masculinity. But Healy puts the boot into those myths of masculinity and challenges assumptions about class, queerness and real men. Tracing the historical development of the gay skin from 1968, he assesses what gay men have done to the hardest cult of them all. He asks how they transformed the gay scene in Britain and then around the world, and observes that the ‘previously sublimated queerness of working class youth culture was aggressively foregrounded in punk. Punk harnessed the energies of an underclass dissatisfied with a sanitised consumer youth culture, and it was from the realm of dangerous sexualities that it appropriated its shocking signifiers.’5 There is now a whole cult of gay men who like nothing better than displaying their transformative sexuality by shaving their heads and putting on their Docs to go down the pub for a few drinks. Supposedly as hard as nails and as gay as fuck, the look is more than a costume, as much leatherwear has become in recent years: it is a spiritual attitude and a way of life. It can also signify a vulnerable persona open to connection, passion, tenderness and togetherness.

In 1992 I took this spiritual belonging to a tribe to a new level. For years I had suffered from depression and self-harm, cutting my arms with razor blades. Now, in an act of positive energy and self-healing, skinhead friend Glenn performed three and a half hours of cutting on my right arm as a form of tribal scarification. There was no pain: I divorced my mind from my body and went on a journey, a form of astral travel. It was the most spiritual experience of my life. Afterwards we both needed a drink, so we put on our gear and went down to the Exchange Hotel on Oxford Street in Sydney with blood still coming from my arm. I know the queens were shocked – the looks we got reflected, in part, what blood meant to the gay community in that era – but this is who I then was. The black and white photograph in this chapter (below) was taken a day later. Paraphrasing Leonard Peltier, I was letting who I was ring out and resonate in every deed. I was taking responsibility for my own being. From that day to this, I have never cut myself again.

These tribal belongings and deviant sexualities speak of a desire to explore the self and the world. They cross the prohibition of the taboo by subverting gender norms through a paradoxical masculinity that ironically eroticises the desire for traditional masculinity. As Brian Pronger observes,

“Paradoxical masculinity takes the traditional signs of patriarchal masculinity and filters them through an ironic gay lens. Signs such as muscles [and gay skinheads], which in heterosexual culture highlight masculine gender by pointing out the power men have over women and the power they have to resist other men, through gay irony emerge as enticements to homoerotic desire – a desire that is anathema to orthodox masculinity. Paradoxical masculinity invites both reverence for the traditional signs of masculinity and the violation of those signs.”6

Violation is critical here. Through violation gay men are brought closer to a physical and mental eroticism. I remember going to dance parties with my partner and holding each other at arm’s length on the pumping dance floor, rubbing our shaved heads together for what seemed like minutes on end among the sweaty crowd, and being transported to another world. I lost myself in another place of ecstatic existence. Wearing my punk jacket, being a gay skinhead and exploring different pleasures always took me out of myself into another realm – a sensitive gay man who belonged to a tribe that was as sexy and deviant as fuck.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Marcus Bunyan. “Punk Jacket,” in Chris Brickell and Judith Collard (eds.,). Queer Objects. Manchester University Press, 2019, pp. 342-349.

Word count: 2,055

Endnotes

1/ Anonymous. ‘The Artist Behind the Iconic Silence = Death Image’, University of California Press Blog, 1 June 2017: https://www.ucpress.edu/blog/27892/the-artist-behind-the-iconic-silence-death-image

2/ Silence Opens Door, ‘Avram Finkelstein: Silence=Death,’ YouTube, 4 March 2010:

https://youtu.be/7tCN9YdMRiA

3/ Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice was started in 1987 in New York as a response to the bigotry of the growing white power movement in 1982

4/ Anonymous, ‘Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice’:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skinheads_Against_Racial_Prejudice

5/ Murray Healy, Gay Skins: Class, masculinity and queer appropriation (London: Cassell, 1996), p. 397

6/ Brian Pronger, The Arena of Masculinity: Sports, homosexuality, and the meaning of sex (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1990), p. 145

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Punk Jacket

c. 1989-1991

Mixed media

Collection of the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives (ALGA)

© Marcus Bunyan and ALGA

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Self-portrait with punk jacket, flanny and 14 hole steel toe capped Docs

1991

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Marcus (after scarification), Sydney

1992

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

Other Marcus photographs in the Queer Objects book

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Two torsos

1991

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Fred and Andrew, Sherbrooke Forest, Victoria

1992

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

You must be logged in to post a comment.