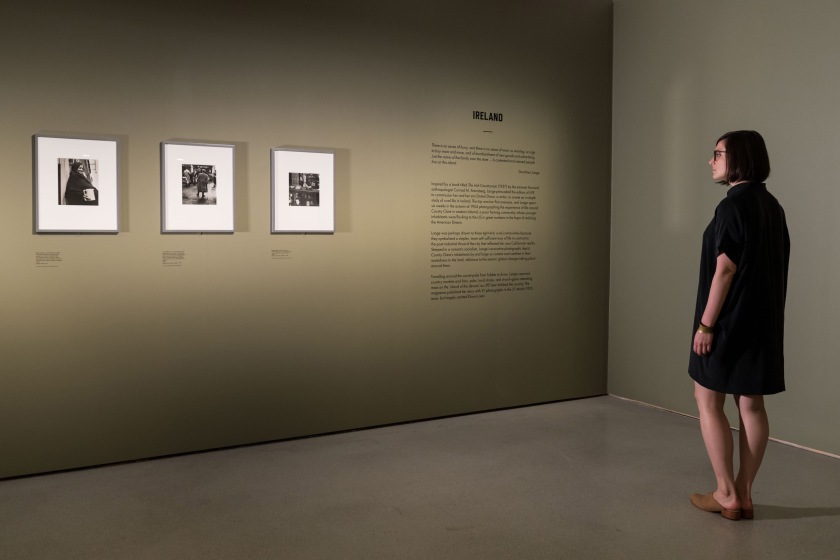

Collection 1940s-1970s, Room 409

From ‘New art from wall to wall’ ongoing

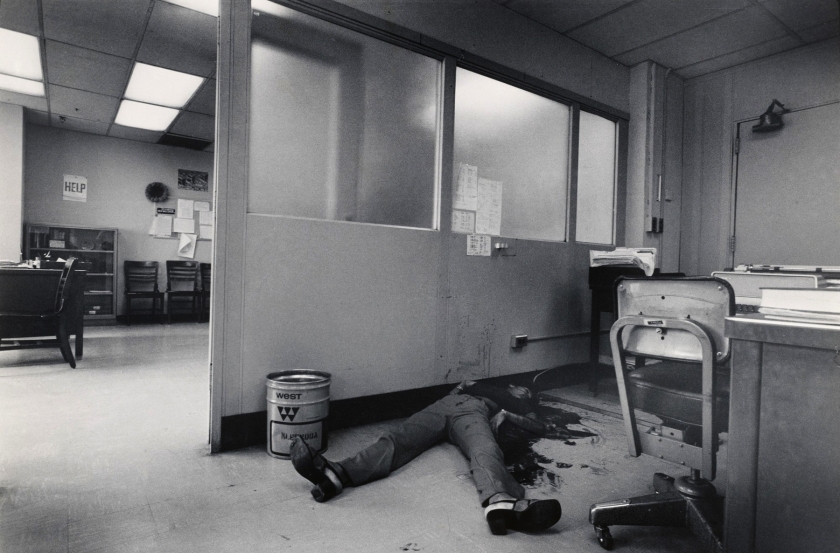

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Shooting Victim in Cook County Morgue, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

As you can imagine, with the tragic situation of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic around the world at the moment, there are few photography exhibitions on view.

This selection of images comes from the collection 1940s-1970s at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in an ongoing display. Please note that not all Gordon Parks photographs shown here are on display, but I include them to give the viewer an overview, a greater understanding of the breadth of photographs included in Parks’ cinematic photo-essay.

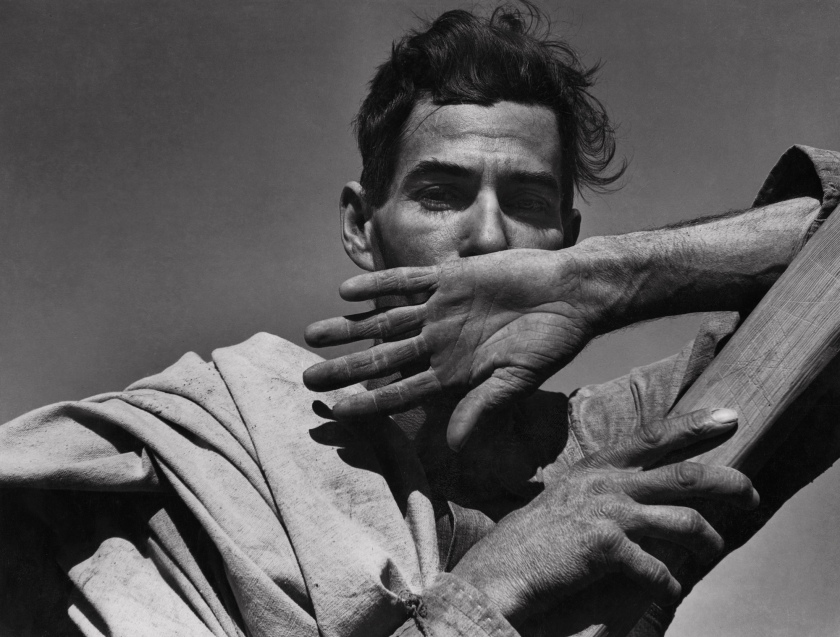

Can you imagine the fortitude of this man: “born into poverty and segregation in Fort Scott, Kansas, in 1912. An itinerant labourer, he worked as a brothel pianist and railcar porter, among other jobs, before buying a camera at a pawnshop, training himself and becoming a photographer. He evolved into a modern-day Renaissance man, finding success as a film director, writer and composer.” “The first Black member of the Farm Security Administration’s storied photo corps; the first Black photographer for the U.S. Office of War Information; the first Black photographer for Vogue; the first Black staff photographer at the weekly magazine Life; and, years later, the first Black filmmaker to direct a motion picture (Shaft) for a major Hollywood studio.” As a photographer he learnt his craft shooting dresses for department stores, taking portraits of society women in Chicago, and studying “the Depression-era images of photographers like Dorothea Lange”. Before joining them as a member of the FSA.

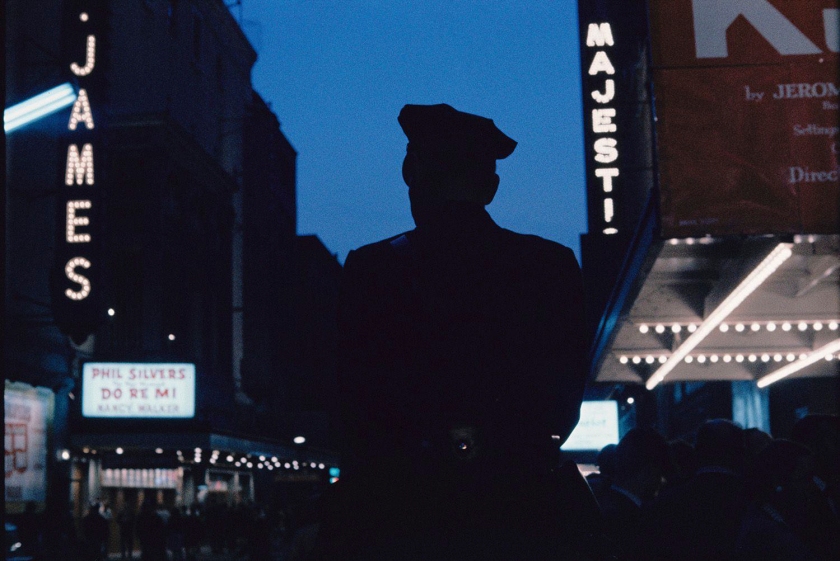

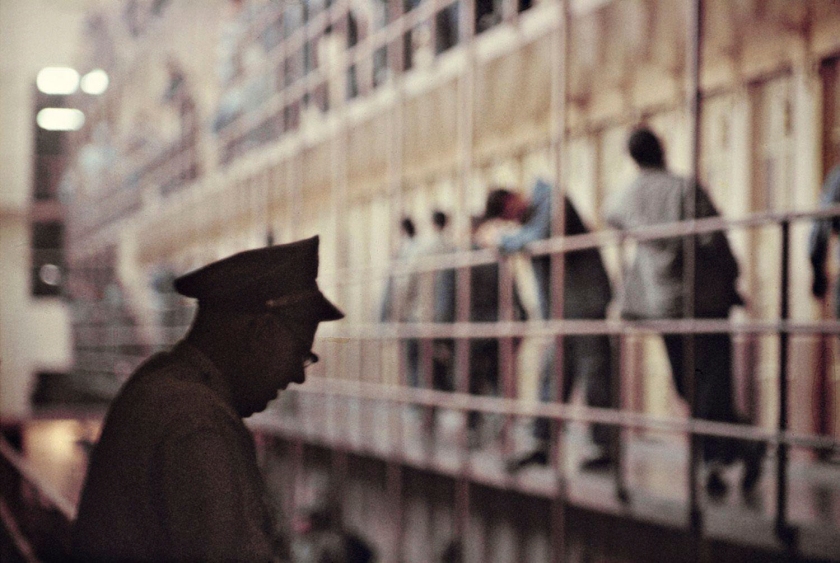

This body of work is remarkable for its non-judgemental gaze, a felt response to a subject which was an assignment for LIFE magazine: an objective reporter with a subjective heart as Parks proclaimed, one who had a certain kind of empathy, “expressing things for people who can’t speak for themselves… the underdogs… in that way I speak for myself.” Park’s photographic strategy was to use colour (rare and expensive in those days), and to close in on detail. Rarely if at all are there any mid to long shots in the photo-essay, placing the photograph in a particular location, the exception being the Untitled street scene under the Chicago “L” (short for “elevated”) rapid transit system and the night-time shot of an illuminated Alcatraz Island – remote, forbidding, isolated.

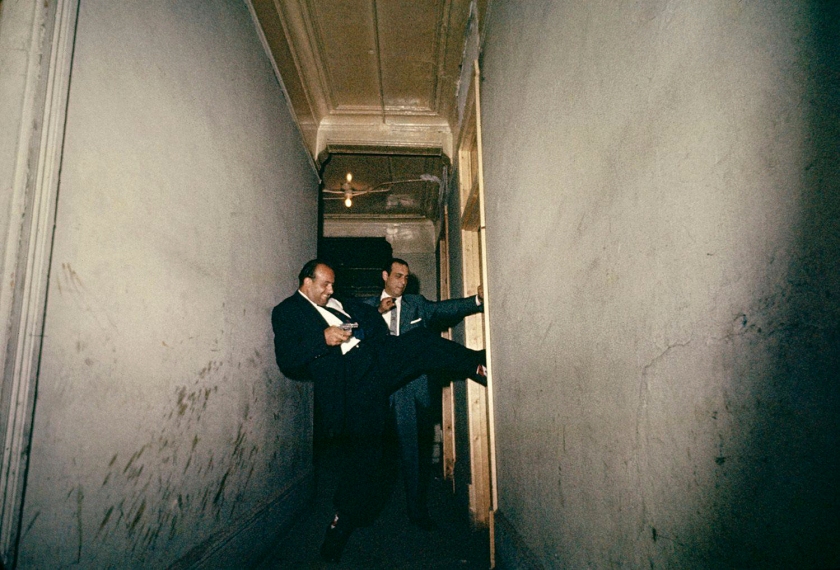

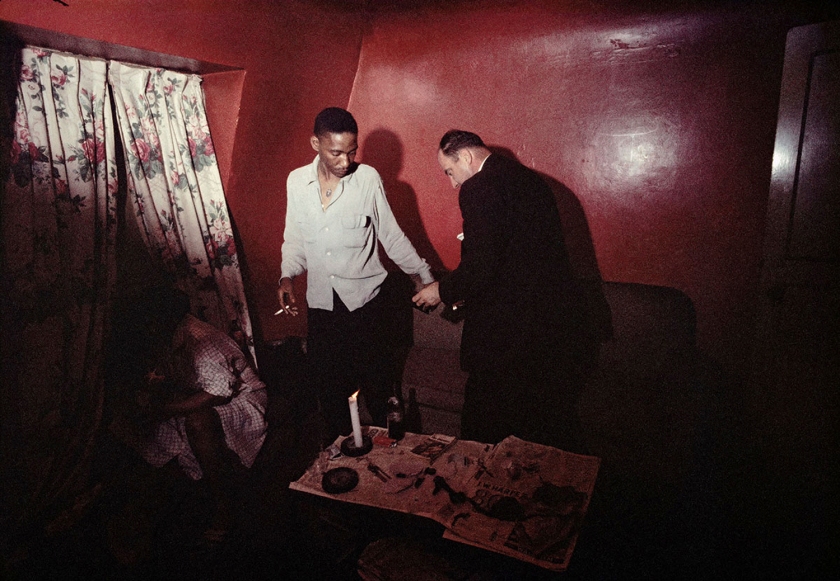

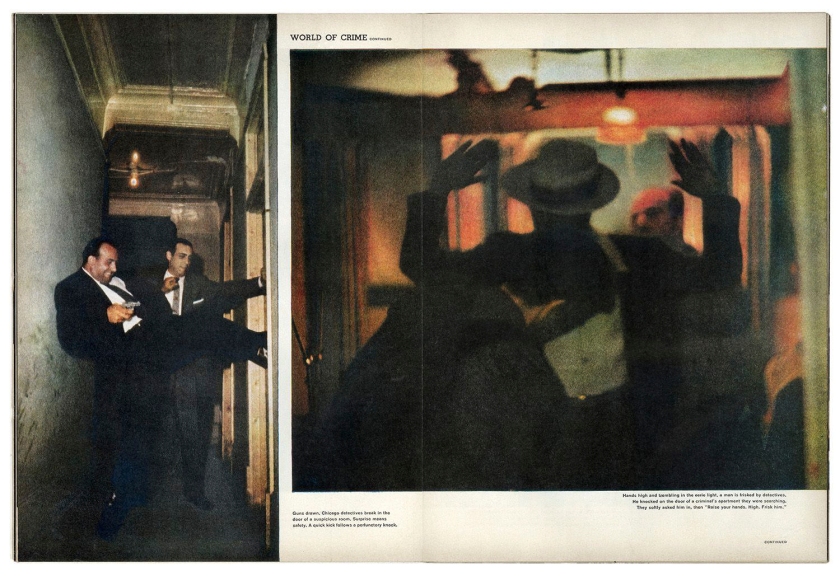

Photographed with candour – using low depth of field, silhouette, chiaroscuro, natural light, low light, night photography, no blur, little flash and challenging perspective, aesthetically a mixture of Dorothea Lange, Weegee and the colour images of Saul Leiter – other intimate images in the series create an “atmosphere” of everyday life on the streets and in the prisons, capturing how the disenfranchised, the desperate and the destitute are controlled and processed by force. “Parks coaxed his camera to record reality so vividly and compellingly that it would allow Life’s readers to see the complexity of these chronically oversimplified situations.” In Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois (1957) we see two detectives of Italian descent raiding a dingy run-down tenement, busting the door open unannounced, guns drawn. In the photograph underneath in the posting, taken inside the oh so red room with floral curtains, one of the detectives questions a black suspect smoking a cigarette, while on the table covered with newspapers sits a burning candle probably providing the only illumination. Cowering in the shadows is a black women, almost unnoticed until you really look at the photograph. This is what abject poverty looks like. In another photograph, Untitled, New York, New York (1957), black and white men emerge from a police van – about the only time black and white men would have sat together in the segregated society of the time (other than being in prison). Can you imagine the atmosphere inside the paddy wagon, the looks, the conversation or lack of it?

Parks’ beautiful photographs, for they are that, include challenging depictions of death, drug use and nonchalantly displayed items such as guns and knuckledusters. Violence and the outcomes of it are an ever present theme in Parks’ documentation of the policing and criminalisation of marginalised people and communities. The photographs are frequently heartbreaking, such as the scars on the legs of a Black American; or devastating, such as the photograph Knifing Victim I (1957). Park’s compresses the space of the action, attacking the nitty gritty of the mise en scène but with no rush to judgement, just telling it how it is. As Sebastian Smee so eloquently observes, “If all of this were mere history – a series of episodes confined to the past – it would be one thing. But Parks’s photographs are alive to the many ways in which crime in the 1950s was a continuation of this legacy [of slavery, of lynching]. Sixty years after he took these photographs, it’s difficult to deny the conclusion that today’s crime-related inequities, from mass incarceration to police brutality, are likewise an extension of this racist legacy.”

And so it goes, both for the marginalised in America and for Indigenous Australians. “According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) in 2018 Black males accounted for 34% of the total male prison population, white males 29%, and Hispanic males 24%” (Wikipedia) while the percentage of US population that is black is 14%. “As of September 2019, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners represented 28% of the total adult prisoner population, while accounting for 3.3% of the general population.” (Wikipedia)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All photographs are used for the purposes of education and research under fair use conditions.

In 1957, Life staff photographer Gordon Parks traversed New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco capturing crime scenes, police precincts, and prisons for “The Atmosphere of Crime,” as his photo essay was titled when it appeared in the magazine. Rather than identify or label “the criminal,” Parks – a fierce advocate for civil rights and a firm believer in photography as a catalyst for change – documented the policing and criminalisation of marginalised people and communities.

Here, Parks’s series is presented in relation to a long history of picturing criminality. In the nineteenth century, mug shots relied on photography’s supposed objectivity as the basis of their value for identification and surveillance. In the twentieth, more sensational images of victims, raids, and arrests circulated in newspapers and tabloids. In contrast, Parks urges us to look beyond individual people and events, to consider the forces of state and police power that are inextricable from any history of crime – a lesson as essential now as ever.

Text from the MoMA website

“I’m an objective reporter with a subjective heart,” proclaimed Gordon Parks. “I can’t help but have a certain kind of empathy… It’s more or less expressing things for people who can’t speak for themselves… the underdogs… in that way I speak for myself.” For over half a century, from the 1940s to the 2000s, Gordon Parks captured American life with his powerful photographs. After getting his first camera at the age of 25, he used this “weapon of choice” to attack issues including racism, poverty, urban life, and injustice. He became the first African American staff photographer at Life magazine – an immensely influential platform in the golden age of photo-illustrated magazines that not only allowed his art to be seen by many but also brought a critical, nuanced and, importantly, a Black perspective to the stories and depictions that he shared. For a 1957 assignment, he crisscrossed the streets of New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, producing vivid colour images addressing the perceived rise in crime in the US. This series, “The Atmosphere of Crime,” challenged stereotypical images of delinquency, drug use, and corruption.

Text from the Gordon Parks Foundation website

“I don’t know that there is any one thing called “the Black experience,” but the way ‘Life magazine’ used Gordon Parks’ photographs for me actually reinscribed some of those notions of Black pathology, such as a story about a gang member (who was actually a pretty normal young man) or extreme poverty and social disenfranchisement. Parks was a much more complex photographer than that, as we came to fully know after his death, but that’s how we came to know him through ‘Life magazine’.”

Dawoud Bey quoted in Gail O’Neill. “Q&A: How Dawoud Bey uses photography to amplify his voice in the world,” on the ‘ARTS ATL’ website November 6, 2020 [Online] Cited 01/03/2021

Sarah Meister, curator in the Department of Photography, looks at images from Gordon Parks’s 1957 photo essay “The Atmosphere of Crime” (1957) and is moved by the power (and, sadly, continued relevance) of his ability to confront “the great social evils of his time” with an “incredible artistic sensibility.”

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Closing in on a known criminal on Chicago’s South Side, police in a scout car check tensely by radio with headquarters. City lights rainbow the storm-splattered windshield as the car approaches the hideout.

Text from LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957, p. 46.

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Raiding Detectives, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© The Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Drug Search, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Drug Search, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

13 3/4 × 21″ (35 × 53.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

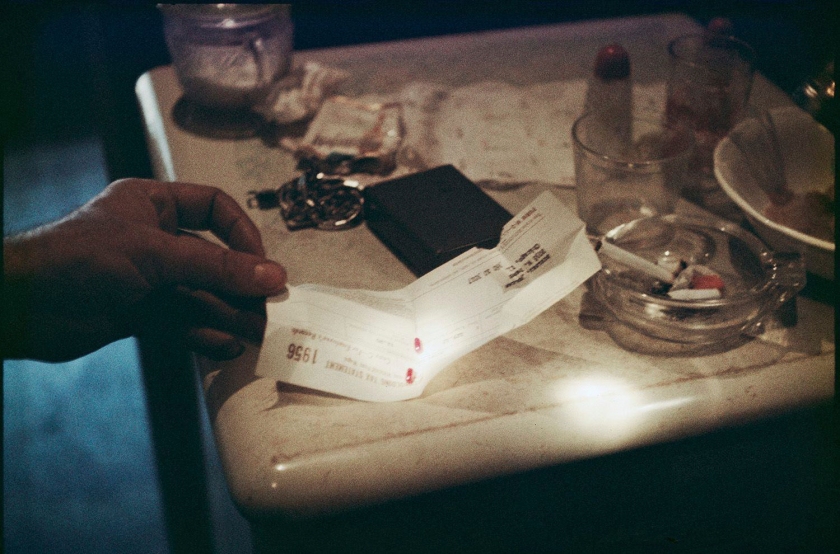

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois (detail)

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

13 3/4 × 21″ (35 × 53.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Narcotics Addict, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, New York, New York

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

13 3/4 × 21″ (35 × 53.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

San Quentin, California

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled (Alcatraz Island), San Francisco, California

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime 1957

Gordon Parks’ ethically complex depictions of crime in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, with previously unseen photographs.

When Life magazine asked Gordon Parks to illustrate a recurring series of articles on crime in the United States in 1957, he had already been a staff photographer for nearly a decade, the first African American to hold this position. Parks embarked on a six-week journey that took him and a reporter to the streets of New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.

Unlike much of his prior work, the images made were in colour. The resulting eight-page photo-essay The Atmosphere of Crime was noteworthy not only for its bold aesthetic sophistication but also for how it challenged stereotypes about criminality then pervasive in the mainstream media. They provided a richly hued, cinematic portrayal of a largely hidden world: that of violence, police work and incarceration, seen with empathy and candour.

Parks rejected clichés of delinquency, drug use, and corruption, opting for a more nuanced view that reflected the social and economic factors tied to criminal behaviour and afforded a rare window into the working lives of those charged with preventing and prosecuting it. Transcending the romanticism of the gangster film, the suspense of the crime caper and the racially biased depictions of criminality then prevalent in American popular culture, Parks coaxed his camera to record reality so vividly and compellingly that it would allow Life‘s readers to see the complexity of these chronically oversimplified situations. The Atmosphere of Crime, 1957 includes an expansive selection of never-before-published photographs from Parks’ original reportage.

Anonymous. “Gordon Parks: The Atmosphere of Crime 1957,” on the Exibart Street website [Online] Cited 07/02/2021

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Crime Suspect with Gun, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Police Raid, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, New York, New York

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, New York, New York

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

11 7/8 × 17 15/16″ (30.1 × 45.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Checking In Suspect, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Detectives Grilling a Suspect, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Fingerprinting Addicts for Forging Prescription, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Cops Bring In Knifing Victim, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

21 × 13 3/4″ (53.3 × 35cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

A sidewalk puddle reflects a common tragedy. A police van drives up to a Chicago hospital’s emergency door with a knifing victim. Tired attendants, once compassionate, sit idly by.

Text from LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Police Bring in Victim, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, New York, New York

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

21 × 13 3/4″ (53.3 × 35cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, New York, New York

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

A prowl car halts in a New York street, a youth comes nervously to its side. “You clean?” the cop asks. “We’re watching you.”

Text from “The Atmosphere of Crime” photographed for LIFE by Gordon Parks. LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957, p. 50.

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Knifing Victim I, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Morgue Photos of Dope Peddler Killed by Cops, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, San Quentin, California [Pre-execution report]

1957

Pigmented inkjet print, printed 2019

17 15/16 × 11 7/8″ (45.6 × 30.1cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Untitled, Chicago, Illinois

1957

Pigmented inkjet print

16 × 20″ (40.6 × 50.8 cm)

Gift of The Gordon Parks Foundation

The left hand of a man who knows the ropes nonchalantly dangles a cigaret through the bars of a Chicago prison. But the man’s right hand, grasping the bars below, betrays him: he is frustrated and locked in.

Text from LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957

MoMA acquires historic Gordon Parks series The Atmosphere of Crime

The photographs will go on view in the New York museum’s permanent collection galleries in May, along with a selection of works by other artists and a clip from the classic 1971 film Shaft

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York has acquired a full set of photographs by Gordon Parks from The Atmosphere of Crime series, a photographic essay examining crime in America he created on assignment with Life magazine in 1957. Along with 55 modern colour inkjet prints created from Parks’s transparencies, selected and bought in consultation with the Gordon Parks Foundation, the foundation has gifted a vintage gelatin silver print that matches a work already in MoMA’s collection, given by the photographer in 1993. Around 15 pieces from the series will go on view in a dedicated gallery on the fourth floor in May, along with an excerpt from his classic 1971 film Shaft and works by other artists from the collection, as part of the next reinstallation of the permanent galleries.

The acquisition comes through years of conversations with the Gordon Parks Foundation, which has been organising in-depth exhibitions of the photographer’s work at major museums since his death in 2006. “When Sarah Meister [MoMA’s curator of photography] and I began speaking a few years ago about how the museum could make a major acquisition, it was about what body of work would really have the most impact to what’s going on in the current world,” says Peter Kunhardt, Jr, the foundation’s executive director. “And we both felt that The Atmosphere of Crime was so relevant, not only because so much hasn’t changed today in our criminal justice system and with police brutality and violence, but also because the work is in colour.”

Colour photography was prohibitively expensive to produce outside of commercial projects at the time Parks first shot the series, Meister explains, and only a selection of images from the series were printed in colour in Life. “The transparencies that Gordon Parks made have been held back for a number of years for the right institution to thoughtfully put together an exhibition and book,” Kunhardt adds. The catalogue, published by Steidl with essays by Meister, Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, and the art historian Nicole Fleetwood, who also wrote Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, includes all the images from the acquisition.

Extract from Helen Stoilas. “MoMA acquires historic Gordon Parks series The Atmosphere of Crime,” on The Art Newspaper website 11 February 2020 [Online] Cited 07/02/2021

Installation views of the Collection 1940s-1970s, Room 409: Gordon Parks and “The Atmosphere of Crime” at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York

None of these images is crude or cliched. A few, it’s true, are brutally direct, in the spirit of Robert Lowell (“Yet why not say what happened?”) or Walker Evans (“If the thing is there, why there it is.”). But others are oddly – and arrestingly – tentative. They’re optically blurred, obscured by visual impediments, as if filtered through the artist’s melancholy, his pity, his black-of-night bewilderment. Looking at them, you feel that something others might rush to – judgment, sentencing, finality – has been deliberately withheld. …

The presence of the word “atmosphere” in the title is apt. It captures both the cumulative impact of the imagery and the complexity of crime’s causes and effects. Park’s use of blur, his unexpected vantage points and his embrace of pooling darkness all elevate his feeling for complication and suffering over the usual simplistic story lines that crowd to the subject of crime. …

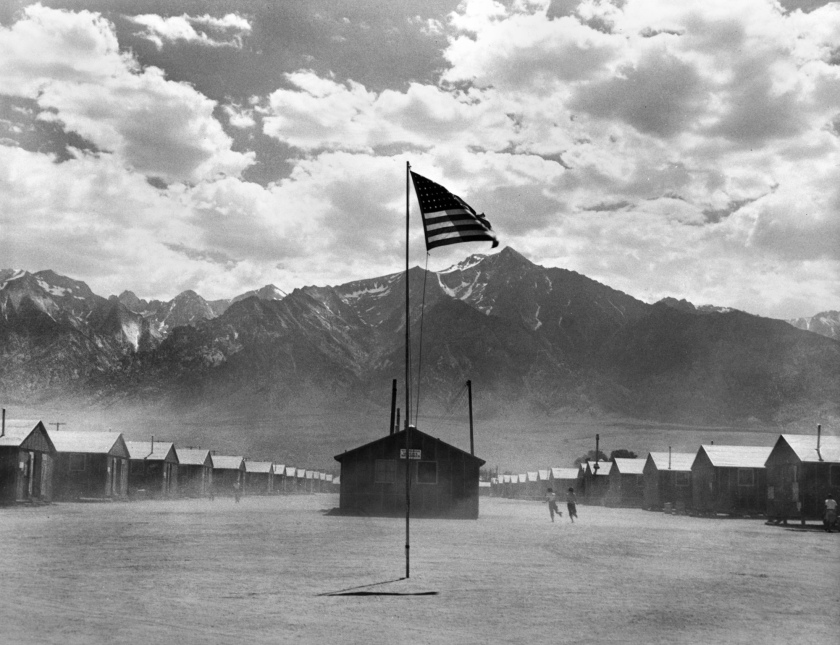

Between 1880 and 1950, lynchings were committed in open defiance of the law, terrorising a Black population that proceeded to escape to the ghettos of the North in massive numbers.

If all of this were mere history – a series of episodes confined to the past – it would be one thing. But Parks’s photographs are alive to the many ways in which crime in the 1950s was a continuation of this legacy. Sixty years after he took these photographs, it’s difficult to deny the conclusion that today’s crime-related inequities, from mass incarceration to police brutality, are likewise an extension of this racist legacy.

Big-city street crime has been in steady decline for three decades now. And yet the complexities and inequities of American crime still hinge on race and are still crudely narrated in the media.

Extract from Sebastian Smee. “With his camera, Gordon Parks humanized the Black people others saw as simply criminals,” on The Washington Post website August 5, 2020 [Online] Cited 07/02/2021

LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957 front cover

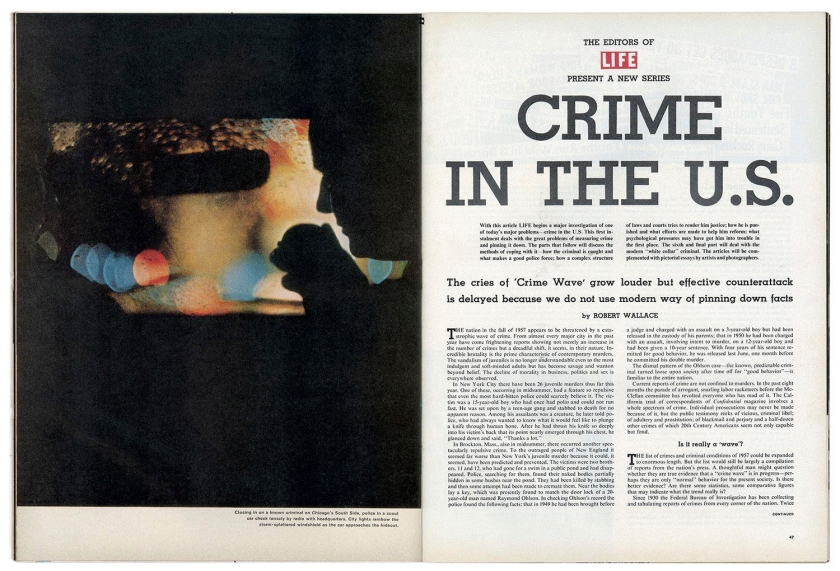

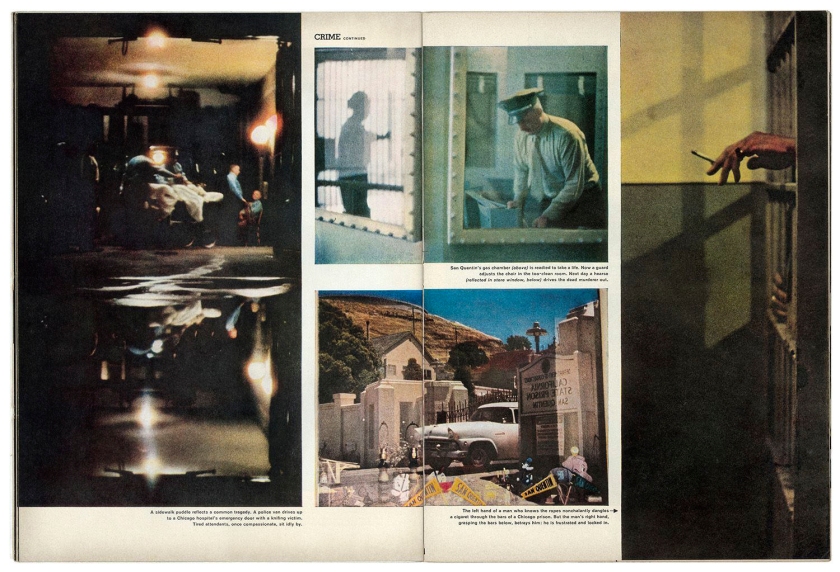

Robert Wallace. “Crime in the U.S.” LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957, pp. 46-47. Photograph by Gordon Parks.

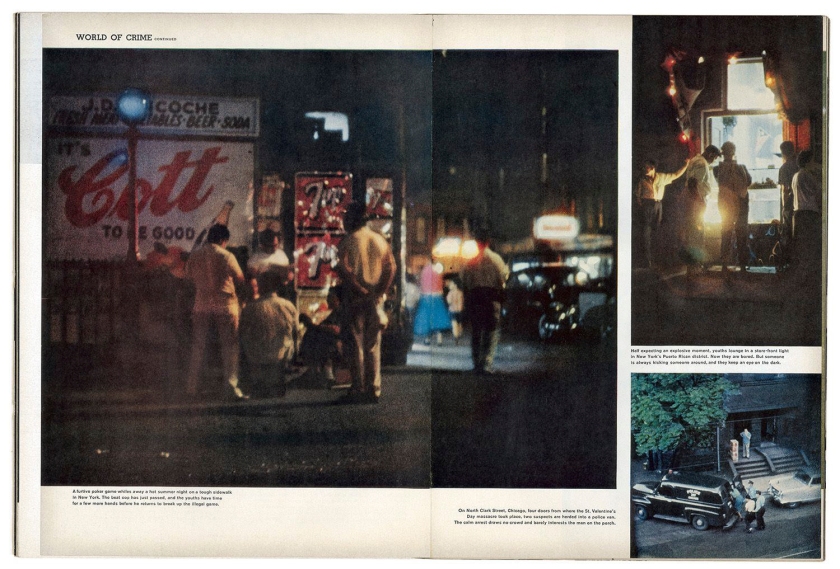

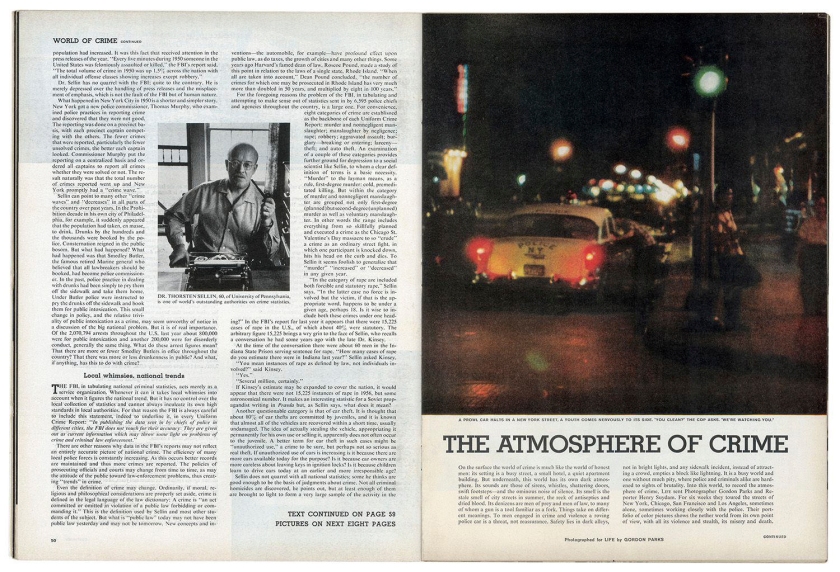

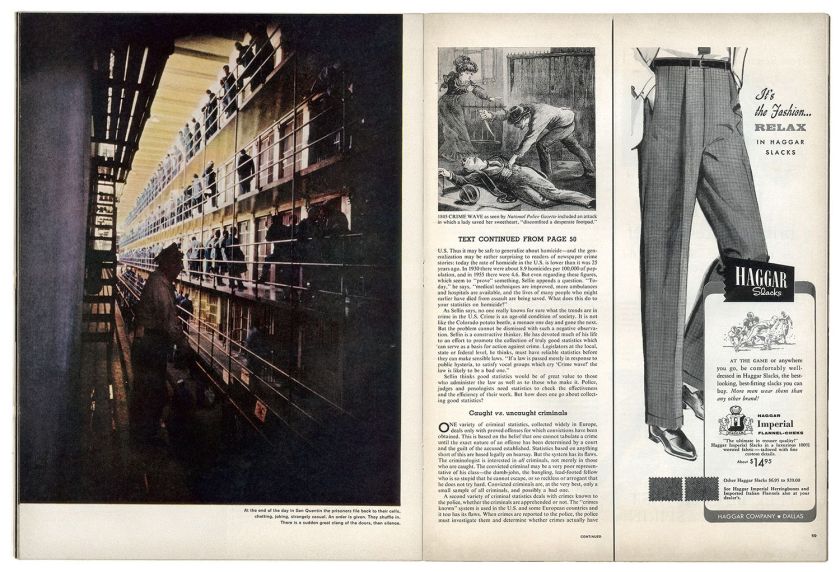

Robert Wallace. “Crime in the U.S.” LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957. Photographs by Gordon Parks.

Robert Wallace. “Crime in the U.S.” LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957, pp. 68-69.

“BANDIT’S ROOST” in New York’s Mulberry Street in 1890s housed Italians who, like most economically exploited immigrant groups, had a high incidence of crime. As Sellin explains, this dropped as they prospered.

Unattributed photograph by Jacob Riis (see below).

Jacob Riis (American born Denmark, 1849-1914)

Bandit’s Roost at 59½ Mulberry Street

1888

From How the Other Half Lives

This image is Bandit’s Roost at 59½ Mulberry Street, considered the most crime-ridden, dangerous part of New York City.

Jacob Riis (American born Denmark, 1849-1914)

Jacob August Riis (1849-1914) was a Danish-American social reformer, “muckraking” journalist and social documentary photographer. He contributed significantly to the cause of urban reform in America at the turn of the twentieth century. He is known for using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the impoverished in New York City; those impoverished New Yorkers were the subject of most of his prolific writings and photography. He endorsed the implementation of “model tenements” in New York with the help of humanitarian Lawrence Veiller. Additionally, as one of the most famous proponents of the newly practicable casual photography, he is considered one of the fathers of photography due to his very early adoption of flash in photography.

While living in New York, Riis experienced poverty and became a police reporter writing about the quality of life in the slums. He attempted to alleviate the bad living conditions of poor people by exposing their living conditions to the middle and upper classes. …

Photography

Bandit’s Roost (1888) by Jacob Riis, from How the Other Half Lives. This image is Bandit’s Roost at 59½ Mulberry Street, considered the most crime-ridden, dangerous part of New York City. Riis had for some time been wondering how to show the squalor of which he wrote more vividly than his words could express. He tried sketching, but was incompetent at this. Camera lenses of the 1880s were slow as was the emulsion of photographic plates; photography thus did not seem to be of any use for reporting about conditions of life in dark interiors. In early 1887, however, Riis was startled to read that “a way had been discovered to take pictures by flashlight. The darkest corner might be photographed that way.” The German innovation, by Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke, flash powder was a mixture of magnesium with potassium chlorate and some antimony sulfide for added stability; the powder was used in a pistol-like device that fired cartridges. This was the introduction of flash photography.

Recognising the potential of the flash, Riis informed a friend, Dr. John Nagle, chief of the Bureau of Vital Statistics in the City Health Department who was also a keen amateur photographer. Nagle found two more photographer friends, Henry Piffard and Richard Hoe Lawrence, and the four of them began to photograph the slums. Their first report was published in the New York newspaper The Sun on February 12, 1888; it was an unsigned article by Riis which described its author as “an energetic gentleman, who combines in his person, though not in practice, the two dignities of deacon in a Long Island church and a police reporter in New York”. The “pictures of Gotham’s crime and misery by night and day” are described as “a foundation for a lecture called ‘The Other Half: How It Lives and Dies in New York.’ to give at church and Sunday school exhibitions, and the like.” The article was illustrated by twelve line drawings based on the photographs.

Riis and his photographers were among the first Americans to use flash photography. Pistol lamps were dangerous and looked threatening, and would soon be replaced by another method for which Riis lit magnesium powder on a frying pan. The process involved removing the lens cap, igniting the flash powder and replacing the lens cap; the time taken to ignite the flash powder sometimes allowed a visible image blurring created by the flash.

Riis’s first team soon tired of the late hours, and Riis had to find other help. Both his assistants were lazy and one was dishonest, selling plates for which Riis had paid. Riis sued him in court successfully. Nagle suggested that Riis should become self-sufficient, so in January 1888 Riis paid $25 for a 4×5 box camera, plate holders, a tripod and equipment for developing and printing. He took the equipment to the potter’s field cemetery on Hart Island to practice, making two exposures. The result was seriously overexposed but successful.

For three years, Riis combined his own photographs with others commissioned of professionals, donations by amateurs and purchased lantern slides, all of which formed the basis for his photographic archive.

Because of the nighttime work, he was able to photograph the worst elements of the New York slums, the dark streets, tenement apartments, and “stale-beer” dives, and documented the hardships faced by the poor and criminal, especially in the vicinity of notorious Mulberry Street. …

Social attitudes

Riis’s concern for the poor and destitute often caused people to assume he disliked the rich. However, Riis showed no sign of discomfort among the affluent, often asking them for their support. Although seldom involved with party politics, Riis was sufficiently disgusted by the corruption of Tammany Hall to change from being an endorser of the Democratic Party to endorse the Republican Party. The period just before the Spanish-American War was difficult for Riis. He was approached by liberals who suspected that protests of alleged Spanish mistreatment of the Cubans was merely a ruse intended to provide a pretext for US expansionism; perhaps to avoid offending his friend Roosevelt, Riis refused the offer of good payment to investigate this and made nationalist statements.

Riis emphatically supported the spread of wealth to lower classes through improved social programs and philanthropy, but his personal opinion of the natural causes for poor immigrants’ situations tended to display the trappings of a racist ideology. Several chapters of How the Other Half Lives, for example, open with Riis’ observations of the economic and social situations of different ethnic and racial groups via indictments of their perceived natural flaws; often prejudices that may well have been informed by scientific racism.

Criticism

Riis’s sincerity for social reform has seldom been questioned, but critics have questioned his right to interfere with the lives and choices of others. His audience comprised middle-class reformers, and critics say that he had no love for the traditional lifestyles of the people he portrayed. Stange (1989) argues that Riis “recoiled from workers and working-class culture” and appealed primarily to the anxieties and fears of his middle-class audience. Swienty (2008) says, “Riis was quite impatient with most of his fellow immigrants; he was quick to judge and condemn those who failed to assimilate, and he did not refrain from expressing his contempt.” Gurock (1981) says Riis was insensitive to the needs and fears of East European Jewish immigrants who flooded into New York at this time.

Libertarian economist Thomas Sowell (2001) argues that immigrants during Riis’s time were typically willing to live in cramped, unpleasant circumstances as a deliberate short-term strategy that allowed them to save more than half their earnings to help family members come to America, with every intention of relocating to more comfortable lodgings eventually. Many tenement renters physically resisted the well-intentioned relocation efforts of reformers like Riis, states Sowell, because other lodgings were too costly to allow for the high rate of savings possible in the tenements. Moreover, according to Sowell, Riis’s own personal experiences were the rule rather than the exception during his era: like most immigrants and low-income persons, he lived in the tenements only temporarily before gradually earning more income and relocating to different lodgings.

Riis’s depictions of various ethnic groups can be harsh. In Riis’s books, according to some historians, “The Jews are nervous and inquisitive, the Orientals are sinister, the Italians are unsanitary.”

Riis was also criticised for his depiction of African Americans. He was said to portray them as falsely happy with their lives in the “slums” of New York City. This criticism didn’t come until much later after Riis had died. His writing was overlooked because his photography was so revolutionary in his early books.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“The Atmosphere of Crime” photographed for LIFE by Gordon Parks. LIFE magazine, September 9, 1957, p. 50.

Gordon Parks’ photo essay “The Atmosphere of Crime” in Life Magazine, September 9, 1957, pp. 58-59.

Because this year marks the 50th anniversary of his groundbreaking 1971 film, “Shaft”; because two fine shows of his pioneering photojournalism are on view at the Jack Shainman galleries in Chelsea; because a suite from his influential 1957 series, “The Atmosphere of Crime,” is a highlight of “In and Around Harlem,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art; and because, somehow, despite the long shadow cast by a man widely considered the preeminent Black American photographer of the 20th century, he is too little known, the time seems right to revisit some elements of the remarkable life, style and undimmed relevance of Gordon Parks.

Last born of 15 children, he made a career of firsts

Born Gordon Roger Alexander Buchanan Parks in Fort Scott, Kansas, on Nov. 30, 1912, he attended segregated schools where he was prohibited from playing sports and was advised not to aim for college because higher education was pointless for people destined to be porters and maids.

Once, he was beaten up for walking with a light-skinned cousin. Once, he was tossed into the Marmaton River by three white boys fully aware that he could not swim. Once, he was thrown out of a brother-in-law’s house where he was sent to live after his mother’s death. This was in St. Paul, at Christmas. He rode a trolley all night to keep warm.

The road to fame had plenty of detours

At various points in his early years, Parks played the piano in a brothel, was a janitor in a flophouse and was a dining car waiter on the cross-country railroad. He survived these travails to become, following a route that was anything but direct, the first Black member of the Farm Security Administration’s storied photo corps; the first Black photographer for the U.S. Office of War Information; the first Black photographer for Vogue; the first Black staff photographer at the weekly magazine Life; and, years later, the first Black filmmaker to direct a motion picture for a major Hollywood studio. By the standards of a Jim Crow era, Parks’ perseverance rose to the level of the biblical.

He got his break shooting dresses

As passengers have done everywhere and always, those on the North Coast Limited between Chicago and Seattle tossed their onboard reading when they were done. Parks scavenged the well-thumbed magazines and, taking them home, discovered both the Depression-era images of photographers like Dorothea Lange and the exotic spheres depicted in Vogue.

He bought his first camera at a pawnshop in Seattle in 1937 and taught himself how to use it. Returning to the Minneapolis area where he had lived for a time, he scouted work shooting for local department stores. All except one rebuffed him.

This, as it happened, was Frank Murphy, the most fashionable boutique in the city, a shop with a running fountain, a resident parrot and a clientele that ran to women from the Pillsbury, Ordway and Dayton dynasties and who relied on the buyers there to supply them with things like “telephone dresses,” for those who considered it unseemly to take calls in dishabille.

By legend, it was the owner’s wife, Madeleine, who insisted that her husband hire the fledgling photographer despite his inexperience, for reasons never made clear. The bet paid off, though, since the images Parks produced promptly resulted in more work, a local exhibition and a telephone call from Marva Louis, then the wife of the world heavyweight boxing champion, Joe Louis, who encouraged him to relocate to Chicago, where he began taking portraits of society women. It was a career transit compressed in a sequence of events so implausible as to seem cinematic. Yet, for Parks, it was just a beginning.

“From the start, Parks knew how to make a beautiful picture,” photography critic Vince Aletti said. And it is true that, long after Parks established his reputation with unflinching photographic series on the civil rights movement, Harlem gangs, the Black Panthers, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam, he continued to move easily between photojournalism and the fashion work for which he maintained a lifelong regard – and which, along with his access to elements of Black life largely invisible to white readers, was among the reasons he was hired in the first place by Life.

© 2021 The New York Times Company

Unknown photographer

Untitled (Pages from an album of mugshots)

1870s-80s

Albumen silver prints

Each 9 1/8 × 4 7/16″ (23.2 × 11.2cm)

Times Wide World Photos

“Ms. Ruth Snyder as She Looks Today”

April 1927

Gelatin silver print

9 7/8 × 7 1/2″ (25.1 × 19.1cm)

The New York Times Collection

© 2021 Times Wide World Photos

Ruth Brown Snyder (March 27, 1895 – January 12, 1928) was an American murderer. Her execution in the electric chair at New York’s Sing Sing Prison in 1928 for the murder of her husband, Albert Snyder, was recorded in a well-publicised photograph.

Associated Press

“Mob Foiled in Attempted Lynching”

1934

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 8 3/8″ (16.5 × 21.3cm)

The New York Times Collection

© 2021 Associated Press

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968)

Charles Sodokoff and Arthur Webber Use Their Top Hats to Hide Their Faces

1942

Gelatin silver print

10 5/16 × 13 3/16″ (26.2 × 33.5cm)

The Family of Man Fund

© 2021 Weegee/ICP/Getty Images

Associated Press, Roger Higgins

Ethel and Julius Rosenberg on Their Way to Jail in New York

March 29, 1951

Gelatin silver print

6 1/2 × 8 7/16″ (16.5 × 21.4cm)

The New York Times Collection

© 2021 Associated Press

Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The couple was accused of providing top-secret information about radar, sonar, jet propulsion engines, and valuable nuclear weapon designs; at that time the United States was the only country in the world with nuclear weapons. Convicted of espionage in 1951, they were executed by the federal government of the United States in 1953 in the Sing Sing correctional facility in Ossining, New York, becoming the first American civilians to be executed for such charges and the first to suffer that penalty during peacetime.

Other convicted co-conspirators were sentenced to prison, including Ethel’s brother, David Greenglass (who had made a plea agreement), Harry Gold, and Morton Sobell. Klaus Fuchs, a German scientist working in Los Alamos, was convicted in the United Kingdom.

For decades, the Rosenbergs’ sons (Michael and Robert Meeropol) and many other defenders maintained that Julius and Ethel were innocent of spying on their country and were victims of Cold War paranoia. After the fall of the Soviet Union, much information concerning them was declassified, including a trove of decoded Soviet cables (code-name: Venona), which detailed Julius’s role as a courier and recruiter for the Soviets. Ethel’s role was as an accessory who helped recruit her brother David into the spy ring and she worked in a secretarial manner typing up documents for her husband that were given to the Soviets. In 2008, the National Archives of the United States published most of the grand jury testimony related to the prosecution of the Rosenbergs.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Black Maria, Oakland

1957

Gelatin silver print

10 15/16 × 9 13/16″ (27.9 × 24.9cm)

Gift of the artist

Meyer Liebowitz (American, 1906-1976) / The New York Times

Umberto (Albert) Anastasia Shot to Death in Barber’s Chair

October 25, 1957

Gelatin silver print

7 5/8 × 8 7/16″ (19.4 × 21.4cm)

The New York Times Collection

© 2021 The New York Times

Umberto “Albert” Anastasia (1902-1957) was an Italian-American mobster, hitman, and crime boss. One of the founders of the modern American Mafia and a co-founder and later boss of the Murder, Inc. criminal collective, Anastasia eventually rose to the position of boss in what became the modern Gambino crime family. He was also in control of the New York waterfront for most of his criminal career, including the dockworker unions. He was murdered on October 25, 1957, on the orders of Vito Genovese and Carlo Gambino; Gambino subsequently became boss of the family.

Anastasia was one of the most ruthless and feared organised crime figures in American history; his reputation earned him the nicknames “The One-Man Army”, “Mad Hatter” and “Lord High Executioner”. …

Assassination

On the morning of October 25, 1957, Anastasia entered the barber shop of the Park Sheraton Hotel, at 56th Street and 7th Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. Anastasia’s driver parked the car in an underground garage and then took a walk outside, leaving him unprotected. As Anastasia relaxed in the barber’s chair, two men – scarves covering their faces – rushed in, shoved the barber out of the way, and fired at Anastasia. After the first volley of bullets, Anastasia reportedly lunged at his killers. However, the stunned Anastasia had actually attacked the gunmen’s reflections in the wall mirror of the barber shop. The gunmen continued firing until Anastasia finally fell dead on the floor.

The Anastasia homicide generated a tremendous amount of public interest and sparked a high-profile police investigation. Per The New York Times journalist and Five Families author Selwyn Raab, “The vivid image of a helpless victim swathed in white towels was stamped in the public memory”. However, no one was charged in the case. Speculation on who killed Anastasia has centred on Profaci crime family mobster Joe Gallo, the Patriarca crime family of Providence, Rhode Island, and certain drug dealers within the Gambino family. Initially, the NYPD concluded that Anastasia’s homicide had been arranged by Genovese and Gambino and that it was carried out by a crew led by Gallo. At one point, Gallo boasted to an associate of his part in the hit, “You can just call the five of us the barbershop quintet”. Elsewhere, Genovese had traditionally strong ties to Patriarca boss Raymond L. S. Patriarca.

Anastasia’s funeral service was conducted at a Brooklyn funeral home; the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn had refused to sanction a church burial. Anastasia was interred in Green-Wood Cemetery in Greenwood Heights, Brooklyn, attended by a handful of friends and relatives. It is marked “Anastasio”. In 1958, his family emigrated to Canada, and changed the name to “Anisio”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

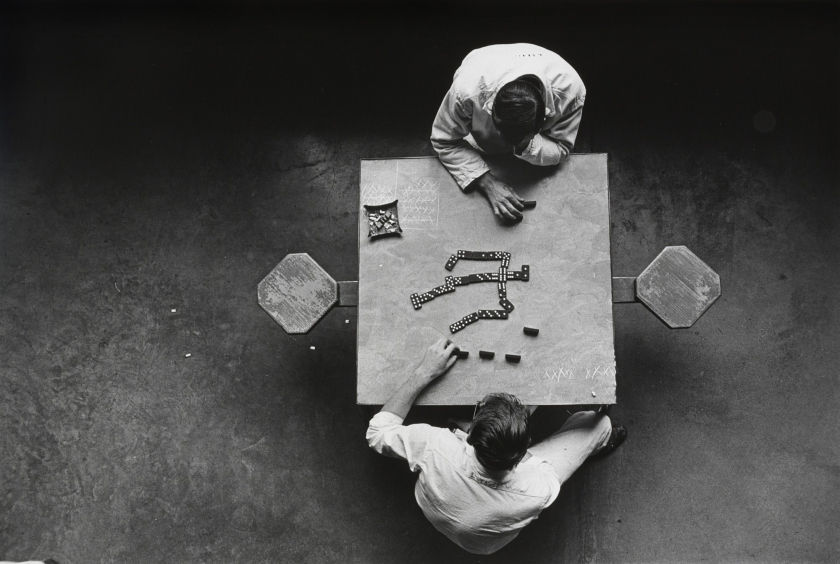

Danny Lyon (American, b. 1942)

Dominoes, Walls Unit, Texas

1967-1969

Gelatin silver print

11 × 14″ (28 × 35.6cm)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James Hunter

© 2021 Danny Lyon

John Hubbard / Black Star Publishing Company

“Kennedy Car off Bridge to Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts”

July 19, 1969

Gelatin silver print

6 13/16 × 9 15/16″ (17.3 × 25.2cm)

The New York Times Collection

© 2021 John Hubbard/Black Star Publishing Co.

The Chappaquiddick incident (popularly known as Chappaquiddick) was a single-vehicle car crash that occurred on Chappaquiddick Island in Massachusetts some time around midnight between Friday, July 18, and Saturday, July 19, 1969. The crash was caused by Senator Edward M. (Ted) Kennedy’s negligence and resulted in the death of his 28-year-old passenger Mary Jo Kopechne, who was trapped inside the vehicle.

Kennedy left a party on Chappaquiddick at 11:15 p.m. Friday, with Kopechne. He maintained his intent was to immediately take Kopechne to a ferry landing and return to Edgartown, but that he accidentally made a wrong turn onto a dirt road leading to a one-lane bridge. After his car skidded off the bridge into Poucha Pond, Kennedy swam free, and maintained he tried to rescue Kopechne from the submerged car, but he could not. Kopechne’s death could have happened any time between about 11:30 p.m. Friday and 1 a.m. Saturday, as an off-duty deputy sheriff maintained he saw a car matching Kennedy’s at 12:40 a.m. Kennedy left the scene and did not report the crash to police until after 10 a.m. Saturday. Meanwhile, a diver recovered Kopechne’s body from Kennedy’s car shortly before 9 a.m. Saturday.

At a July 25, 1969, court hearing, Kennedy pled guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident and received a two-month suspended jail sentence. In a televised statement that same evening, he said his conduct immediately after the crash “made no sense to me at all”, and that he regarded his failure to report the crash immediately as “indefensible”. A January 5, 1970, judicial inquest concluded Kennedy and Kopechne did not intend to take the ferry, and that Kennedy intentionally turned toward the bridge, operating his vehicle negligently, if not recklessly, at too high a rate of speed for the hazard which the bridge posed in the dark. The judge stopped short of recommending charges, and a grand jury convened on April 6, 1970, returning no indictments. On May 27, 1970, a Registry of Motor Vehicles hearing resulted in Kennedy’s driver’s license being suspended for a total of sixteen months after the crash.

The Chappaquiddick incident became national news that influenced Kennedy’s decision not to run for President in 1972 and 1976, and it was said to have undermined his chances of ever becoming President. Kennedy ultimately decided to enter the 1980 Democratic Party presidential primaries, but earned only 37.6% of the vote and lost the nomination to incumbent President Jimmy Carter.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

New York: Woman killed by her boyfriend at her place of employment

1972

Gelatin silver print

15 5/8 × 23 9/16″ (39.7 × 59.8cm)

Acquired through the generosity of Thomas L. Kempner, Jr.

© 2021 Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

You must be logged in to post a comment.