Exhibition dates: 30th January – 19th May, 2024

Exhibition curator: Clément Chéroux, director, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Self-Portrait, Weegee with Speed Graphic Camera

1950

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Collection Friedsam

To see ourselves as others see us

This exhibition attempts to reconcile the two sides of the work of American photographer Weegee (Arthur Felig, 1899-1968) – “First are his stories for the New York press from 1935-1945. Then, photo-caricatures of public personalities developed during his Hollywood period, between 1948-1951, which he continued to produce for the rest of his life” – by showing that, beyond formal differences, the photographer’s approach is a critically coherent investigation into the omnipresence of the spectacle in modern society.

The spectacle is a central notion in the Situationist theory, developed by Guy Debord in his 1967 book The Society of the Spectacle:

“Debord traces the development of a modern society in which authentic social life has been replaced with its representation… The spectacle is the inverted image of society in which relations between commodities have supplanted relations between people, in which “passive identification with the spectacle supplants genuine activity”. “The spectacle is not a collection of images,” Debord writes, “rather, it is a social relation among people, mediated by images.””1

While both halves of Weegee’s photographic work picture the spectacle, I believe that they are a different but connected order of being. Like yin and yang, Weegee’s scenes of chaos “Murder is my business” and “photo-caricatures” emerge from the same psyche but image equal opposites which both repel, attract and complement each other.

Weegee’s photographs which tell stories for the New York press are external representations or emanations captured from the world around us, whereas his later photo-caricatures of public personalities feel to me to be internalised, dream-like representations of his own feelings towards the celebrity people he observed and photographed as much as they are offer insights into their personality.2 Thus, Weegee’s photographs are an examination of a body (an autopsy) both external and internal.

Personally I don’t think that it is necessary to reconcile both halves of Weegee’s work. The bodies exist for what they are: perceptive insights into the existence and spirit of the world and the human race, spec(tac)ular images that mirror a social relation among people which don’t necessarily have to be conflated one with the other.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Debord, Guy (1994)[1967] The Society of the Spectacle, translation by Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books), p. 4 quoted in “The Society of the Spectacle,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 10/05/2024

2/ “external exaggeration high-lights internal character and distortion offers surprising insights into personality”

“How your TV heroes look to Weegee’s magic camera” in Look magazine

Many thank to the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“The curious […], they’re always in a hurry […], but they still find the time to stop and look.

Weegee

“Crime was my oyster,” Weegee wrote in his 1961 memoir, Weegee by Weegee. “I was friend and confidant to them all. The bookies, madams, gamblers, call girls, pimps, con men, burglars and jewel fencers.” … Weegee’s photos from the 1930s and ’40s defined Manhattan as a film noir nightscape of gangsters, bums, slumming swells and tenement dwellers.”

John Strausbaugh. “Crime Was Weegee’s Oyster,” on The New York Times website June 20, 2008 [Online] Cited 13/04/2024

“Weegee is not the first nor the only person to have taken interest in people watching. Not long before him, in 1937, Henri Cartier-Bresson photographed spectators at the Coronation of George VI for Ce Soir. And a quarter century prior, in 1912, Eugène Atget photographed passers-by observing a solar eclipse at Place de la Bastille. But Weegee took the idea even further. He systematised it. He made it a principle he never shied from applying at the first opportunity. It’s a way of placing things at a distance, pushing the viewers to ask themselves about the manner in which they look, making them aware of the fact that they themselves, like the people watching in the photo, are in a voyeuristic position. It’s also a critique of how American society transforms news into spectacle.”

Clément Chéroux

The specular image, then, is accompanied by anxiety-anxiety that it will “soon dissolve like a cloud.” It is the nature of visions (apparitions) to dissolve before our very eyes without disclosing their secrets, just as dream-images are quickly forgotten upon awakening.

Craig Owens. “Posing,” in Difference: On Representation and Sexuality. New York: The New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1985, p. 12

There’s still a mystery to Weegee. The American photographer’s career seems to be split in two. First are his stories for the New York press from 1935-1945. Then, photo-caricatures of public personalities developed during his Hollywood period, between 1948-1951, which he continued to produce for the rest of his life. How can these diametrically opposed bodies of work coexist? Critics have enjoyed highlighting the opposition between the two periods, praising the former and disparaging the latter. This project seeks to reconcile the two parts of Weegee by showing that, beyond formal differences, the photographer’s approach is critically coherent.

The spectacle is omnipresent in Weegee’s work. In the first part of his career, coinciding with the rise of the tabloid press, he was an active participant in transforming news into spectacle. To show this, he often included spectators or other photographers in the foreground of his images. In the second half of his career, Weegee mocked the Hollywood spectacular, its ephemeral glory, adoring crowds, and social scenes. Some years before the Situationist International, his photography presented an incisive critique of the Society of the Spectacle.

Curator Clément Chéroux

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at left, Self-Portrait, Weegee with Speed Graphic Camera (1950, above); at second left, “Chevrolet”. Weegee in front of his typewriter, installed in the trunk of a 1938 Chevrolet, New York (c. 1943, below); at third left bottom, Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York (c. 1939, below); at fourth left, Self-portrait (1950,below); at fifth left, Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide (1944, below); at sixth left, Charles Sodokoff and Arthur Webber Use Their Top Hats to Hide Their Faces (1942, below); and at eighth left, Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver) (1939, below)

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

“Chevrolet”. Weegee in front of his typewriter, installed in the trunk of a 1938 Chevrolet, New York

c. 1943

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive / International Center of Photography, New York / Collection Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Weegee Himself: “I have always been a doer and not a thinker.” Weegee enjoyed putting himself in front of the camera, re-enacting circumstances he was confronted with in his daily work. In the name of pedagogy, and probably a little out of narcissism and self-advertisement, he took pictures of himself writing captions for his photographs in the back of his car, in police wagons and behind bars, never without his camera.

Wall text from the exhibition

Unidentified photographer

Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]

c. 1939

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Self-portrait

1950

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee Tells How

Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, was a New York city freelance news photographer from the 1930s to the 1950s. Here he talks about his career and gives advice to those wanting to become news photographers.

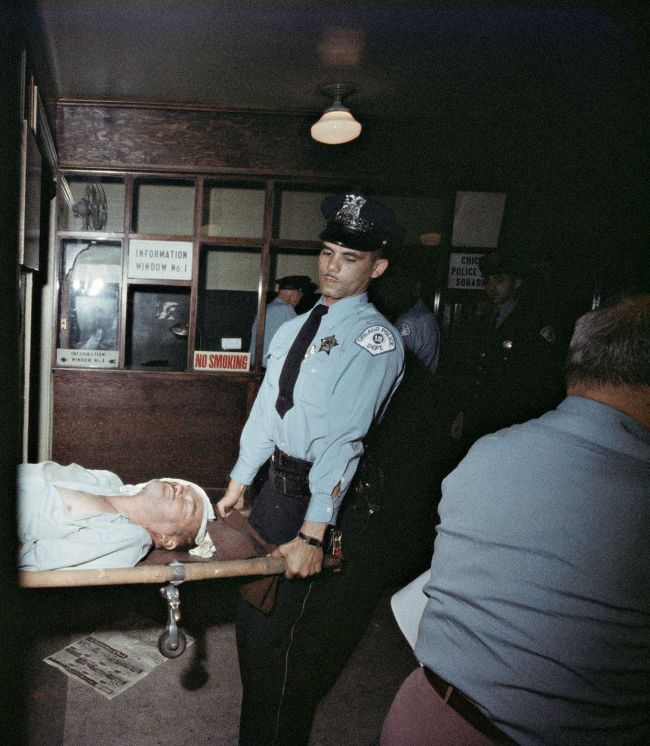

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Frank Pape, Arrested for Homicide

1944

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Charles Sodokoff and Arthur Webber Use Their Top Hats to Hide Their Faces

1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)

1939

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee’s Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver) (1939, above); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York] (1941, below)

Off Road: “Sudden death for one… sudden shock for the other.” American culture is fascinated by twisted metal. In the 19th century, a railroad company staged public collisions between locomotives destined for the junkyard. Weegee photographed many traffic accidents introducing the “car crash” genre, later adopted by other figures, such as Andy Warhol, J.G. Ballard, David Cronenberg, etc.

Wall text from the exhibition

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]

1941

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at right, Weegee’s photograph Henry Rosen (left) and Harvey Stemmer (centre) cover their faces with handkerchiefs after their arrest for bribery and conspiracy to fix a US college basketball match (25 January 1945)

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Holiday Accident in the Bronx

1941

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Exhibition

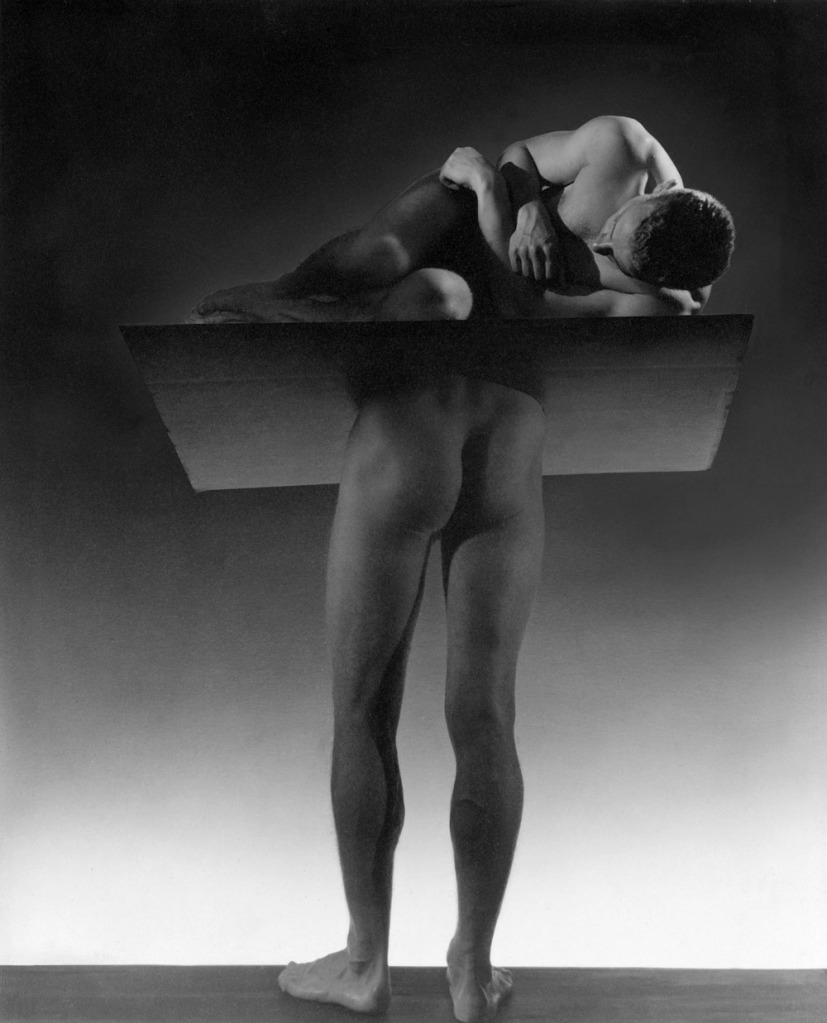

There’s a mystery to Weegee. The American photographer’s career seems to be split in two. One side includes his sensational photography printed in North American tabloids: corpses of gangsters lying in pools of their own blood, bodies trapped in battered vehicles, kingpins looking sinister behind the bars of prison wagons, dilapidated slums consumed by fire, and other harrowing documents on the lives of the underprivileged in New York from 1935 to 1945. Then come the festive photographs – glamorous parties, performances by entertainers, jubilant crowds, openings and premieres – to which we must add a vast array of portraits of public figures that Weegee delighted in distorting using a rich palette of tricks between 1948 and 1951, a practice he pursued until the end of his life.

How can these diametrically opposed bodies of work coexist? Critics have enjoyed highlighting the opposition between the two periods, praising the former and disparaging the latter. The exhibition Autopsy of the Spectacle seeks to reconcile the two parts of Weegee by showing that, beyond formal differences, the photographer’s approach is critically coherent.

The spectacle is omnipresent in Weegee’s work. In the first part of his career, which coincides with the rise of the tabloid press, he was an active participant in transforming news into spectacle. To show this, he often included spectators, or other photographers, in the foreground of his images. In the second half of his career, Weegee mocked the Hollywood spectacular: its ephemeral glory, adoring crowds and social scenes. Some years before the Situationist International, his photography presented an incisive critique of the Society of the Spectacle.

With a new perspective on Weegee’s oeuvre, Autopsy of the Spectacle presents the photographer’s iconic images beside lesser-known works, including images not-yet-exhibited in France.

Biography

Weegee was born Usher Fellig on June 12, 1899, to a Jewish family in Zolochiv, a small town in Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today in western Ukraine. At 11 years old, he joined his father who’d emigrated to the United States. At the immigration station Ellis Island, he became Arthur Fellig. Living in the slums of the Lower East Side, he left school at 14 to earn money to support his family. After working in different professions, he became a traveling photographer, worked for photographers Duckett & Adler, then in the lab of ACME Newspictures agency.

Starting in 1935, he was self-employed as photo-reporter. Towards 1937, he began using the pseudonym Weegee, and around 1941, started marking the backs of his prints with a stamp in the form of a self-fulfilling prophecy: “Weegee the Famous.” For 10 years, connected to Police radio, he took photographs, mainly at night, of crime, arrests, fires, accidents and other news items. Though the photographer most certainly had connections within the Police, without whom his work would not have been possible, he also frequented left-wing circles. He was very close to the Photo League, a group of independent photographers who firmly believed in emancipation through the image and fought for social justice. In 1945, he published his best photographs in a book entitled Naked City, which met with great success both in its reception and sales.

In the spring of 1948, he moved to Hollywood to work in cinema as a technical advisor, sometimes as an actor. He photographed the endless party and developed different photographic techniques used to create his caricatures of celebrities. In December of 1951, after four years on the West Coast, he returned to New York with no intention of resuming his former practice. Up until his death on December 26, 1968, the majority of his work involved taking advantage of his notoriety to publish other books, go on tour, and promote his photo-caricatures in newspapers.

Text from the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson website

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at left, Performer Jimmy Armstrong (c. 1943, below); at second left, Ladies keep their money in their stockings… (1944, below); and at centre, Afternoon Crowd at Coney Island, Brooklyn (1940, below)

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Performer Jimmy Armstrong

c. 1943

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Ladies keep their money in their stockings…

1944

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

“There is no cover charge nor cigarette girl, and a vending machine dispenses cigarettes. Neither is there a hat check girl. Patrons prefer to dance with their hats and coats on. But there is a lively floor show… the only saloon in the Bowery with a cabaret license.”

Weegee

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Afternoon Crowd at Coney Island, Brooklyn

1940

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Courtesy Galerie Berinson, Berlin

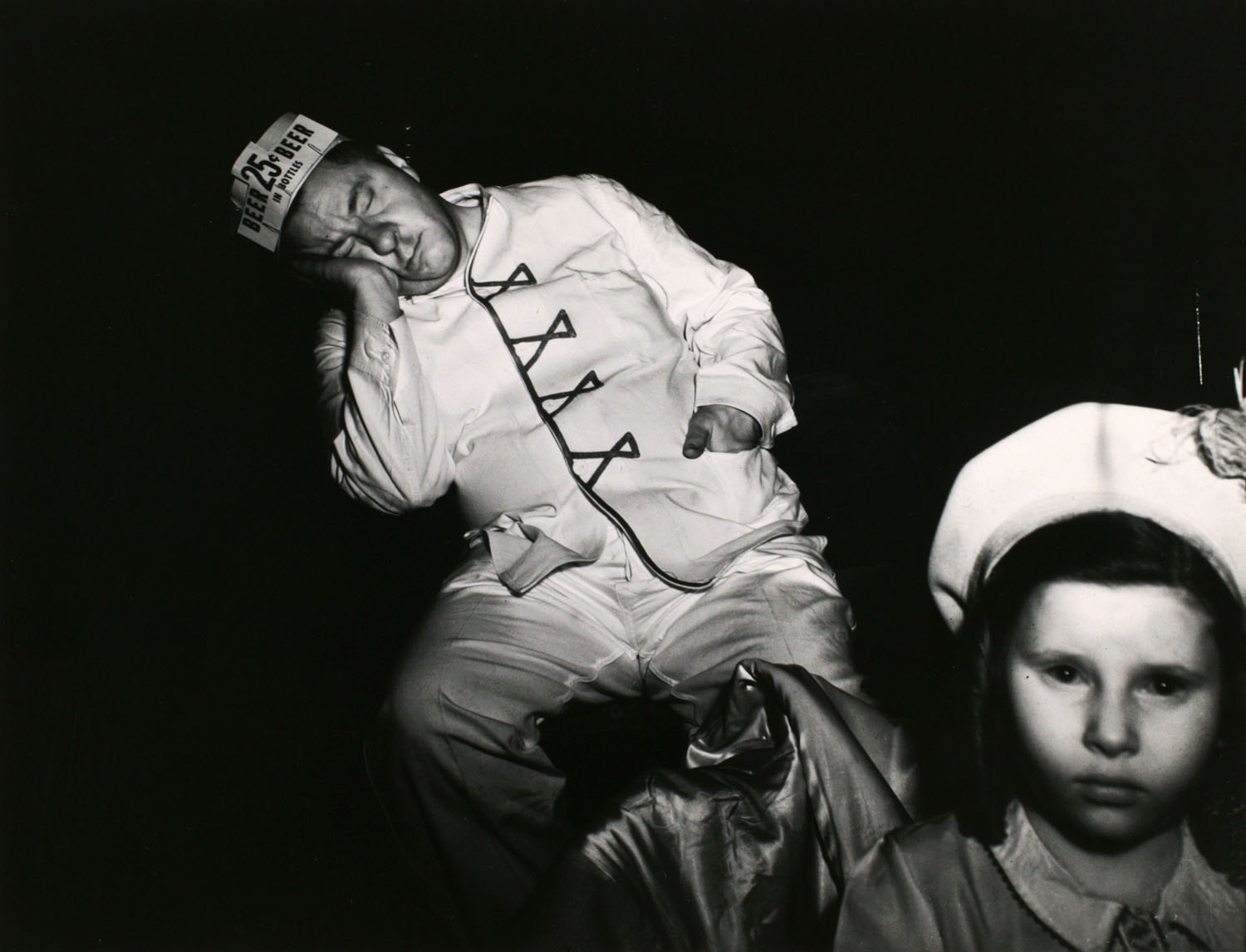

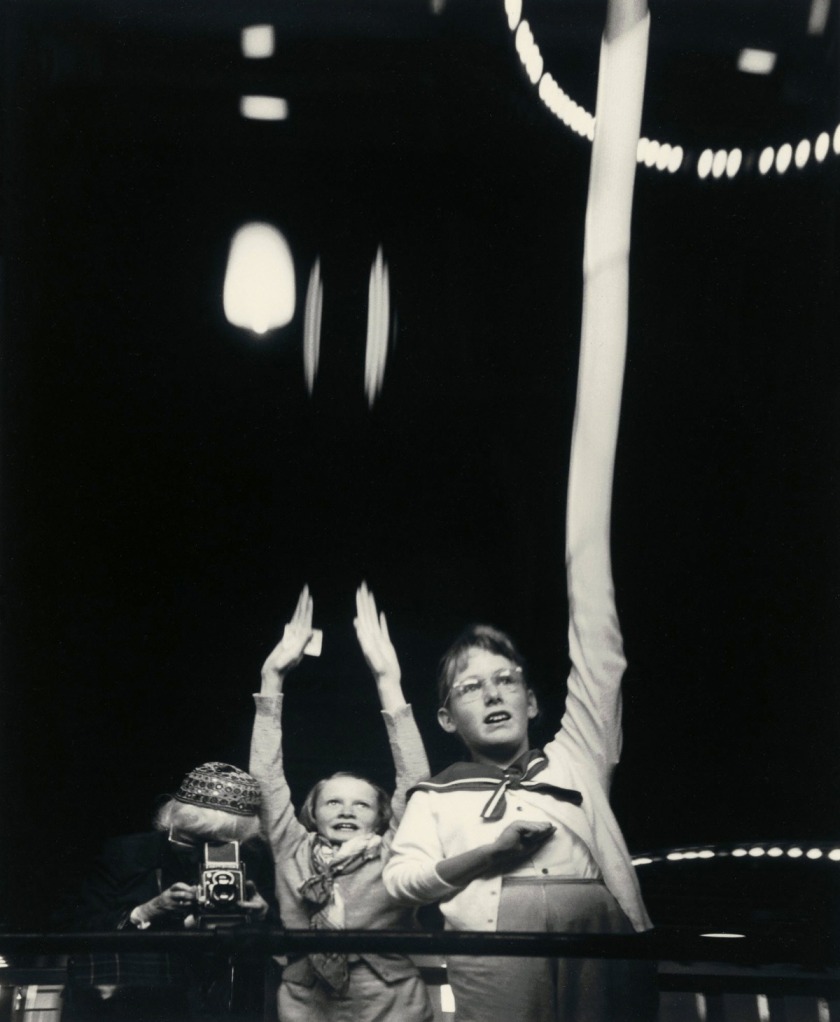

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Sleeping at the Circus, Madison Square Garden, New York

1943

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at centre left, Opening night at the Metropolitan Opera (1943); In the Lobby at the Metropolitan Opera, Opening Night (1943); and at centre right, The Critic (1943, below)

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

The Critic

November 22, 1942

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Collection Friedsam

Even his most popular photograph was a set-up, says Wallis: “The Critic, which was taken in 1943, was surely staged and shows the wealthy Mrs George Washington Cavanaugh and Lady Decies arriving at the opera, greeted by a staggering drunk who seems to be mocking them and who Weegee reportedly rounded up at Sammy’s bar on the Bowery.

“This picture is a good example of how Weegee previsualized a scene, developed a punchy satirical narrative, and staged the picture. The Critic was widely reproduced at the time, and even shown at the Museum of Modern Art.”

Boo Paterson. “Big guns to big top: Weegee at circus,” on the Boo York City website [Online] Cited 13/04/2024

In Weegee’s day similar culture clashes happened at Sammy’s Bowery Follies (267 Bowery, between East Houston and Stanton Streets), which from 1934 to 1970 attracted what The New York Times once described as a mixed crowd of “drunks and swells, drifters and celebrities, the rich and the forgotten.” …

Among the regulars, he wrote in his 1945 book, “Naked City,” was a woman they called Pruneface and a midget who walked the streets dressed as a penguin to promote cigarettes. When the midget got drunk, Weegee wrote, he “offered to fight any man his size in the house.”

Weegee held two book parties there. At the photography center Mr. George showed me silent-film footage taken in 1946 at the party for Weegee’s second book, “Weegee’s People.” Pretty uptown blondes and dowagers in pearls mingle with toothless crones and panhandlers, as models parade in their foundation garments, and a man with a flea circus puts his tiny performers through their paces.

John Strausbaugh. “Crime Was Weegee’s Oyster,” on The New York Times website June 20, 2008 [Online] Cited 13/04/2024

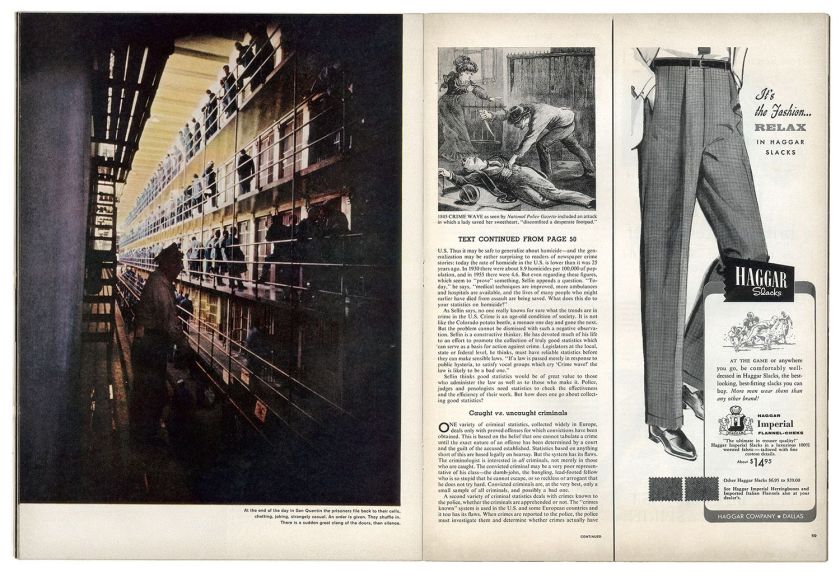

Installation view of the exhibition Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing his photographs in magazine layouts

“Il Fotografo cattivo”, Epoca, Vol. XIII, No. 636, December 1962

© International Center of Photography. Collection privée Paris

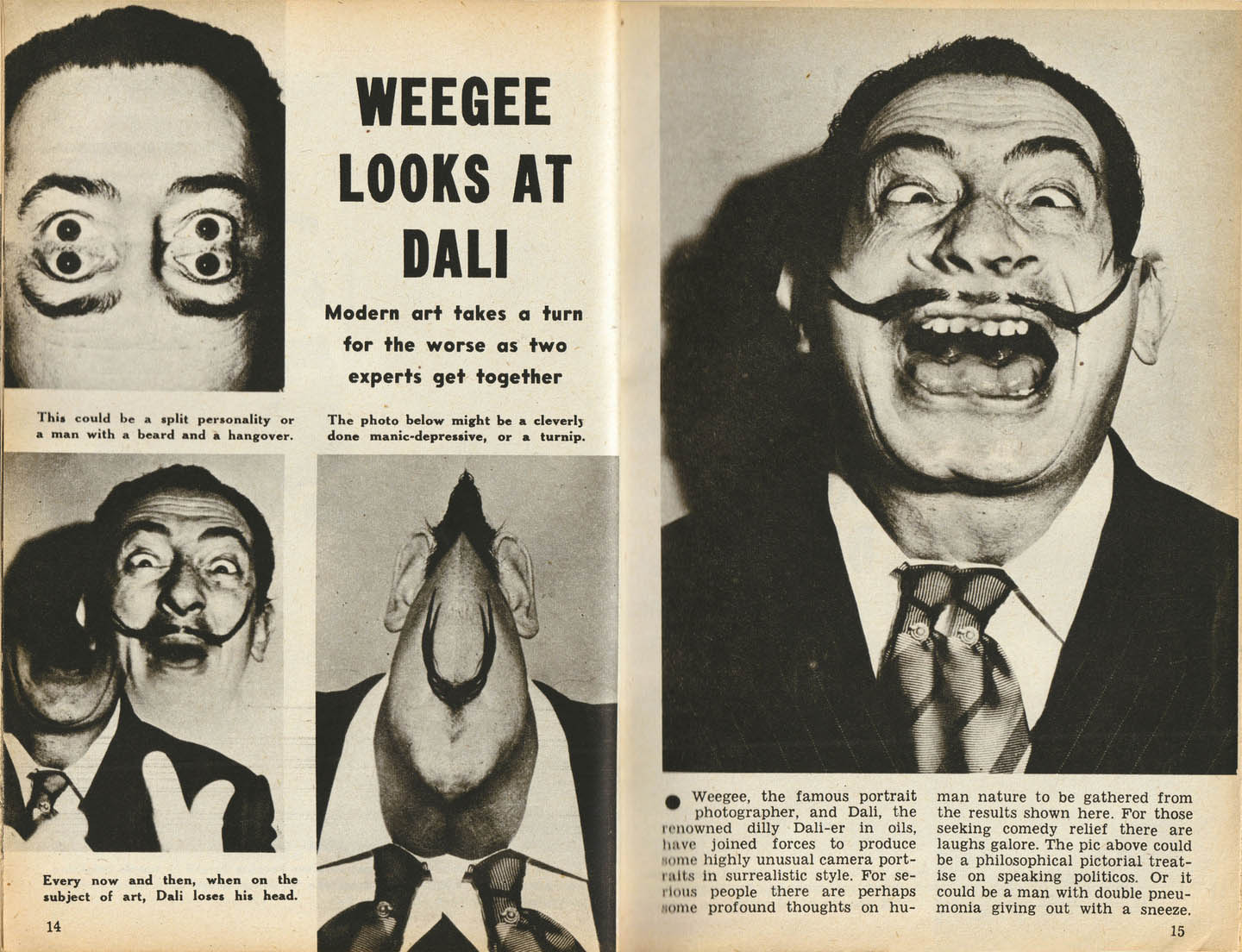

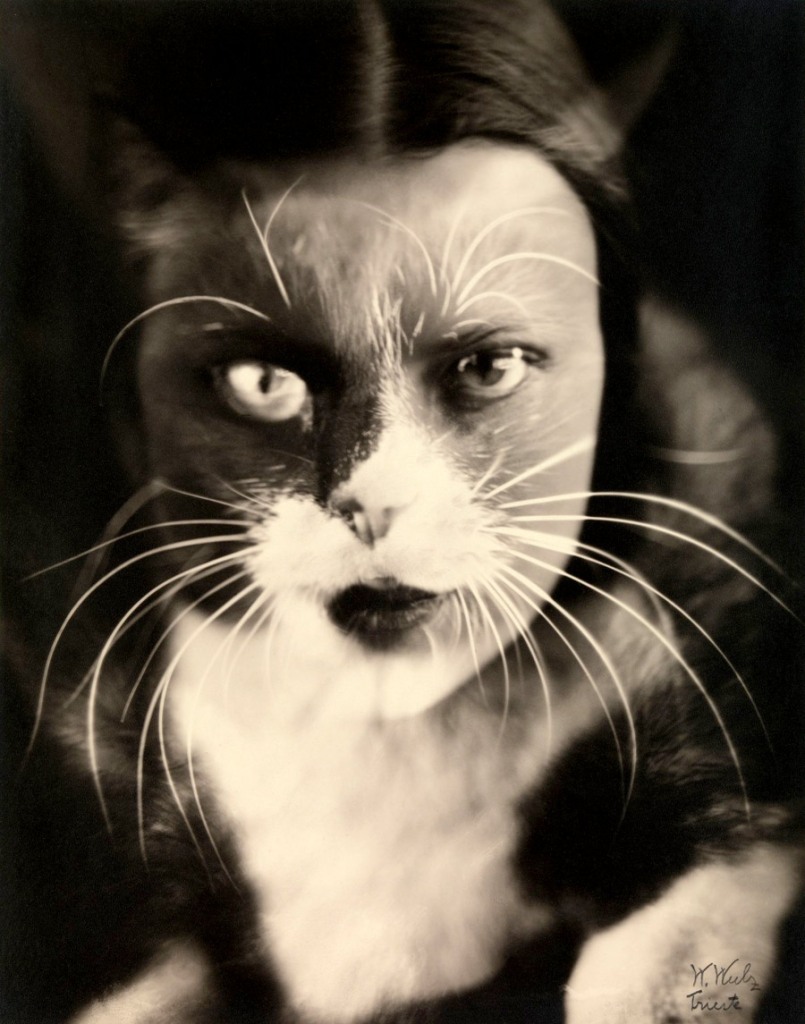

Weegee Looks At Dali

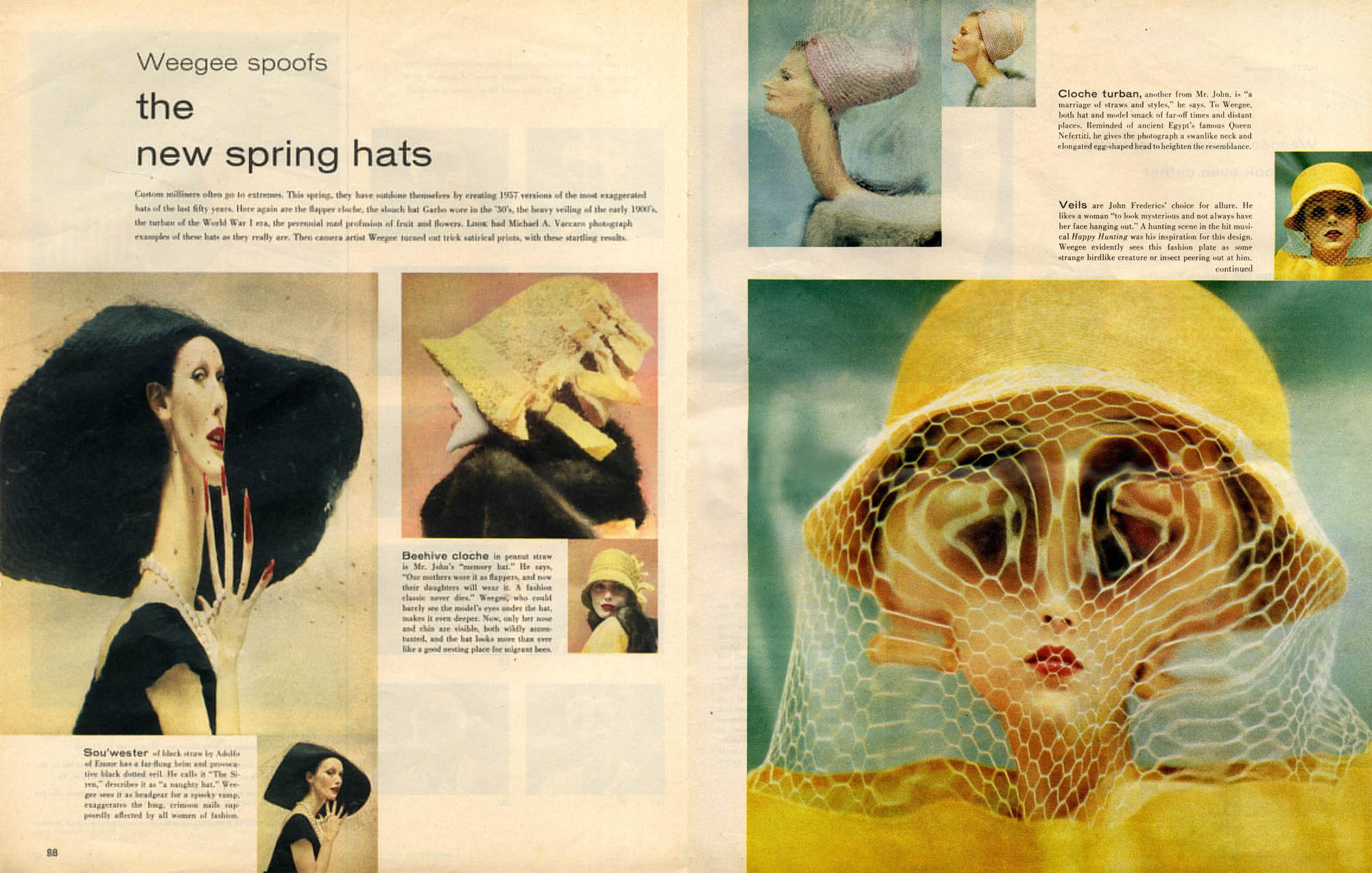

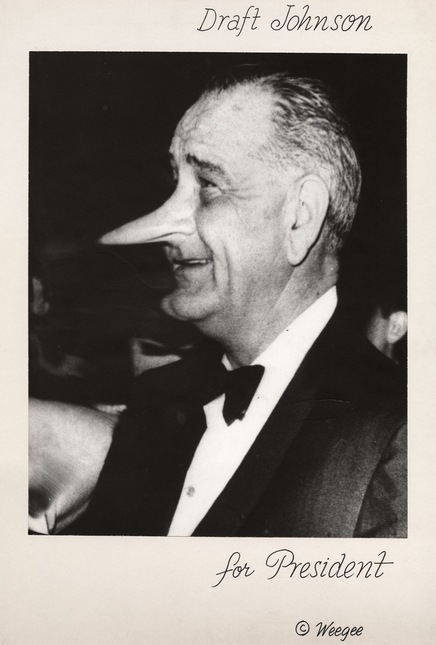

Weegee spoofs

the

new spring hats

Custom milliners often go to extremes. This spring, the have outdone themselves by creating 1957 version of the most exaggerated hats of the last fifty years. Here again are the flapper cloche, the slouch had Garbo wore in the ’30’s, the heavy veiling of the early 1900’s, the turban of the World War I era, the perennial mad profusion of fruit and flowers. Look had Michael A. Vaccaro photograph examples of these hats as they really are. Then camera artist Weegee turned out satirical prints, with these startling results.

Look magazine 1957

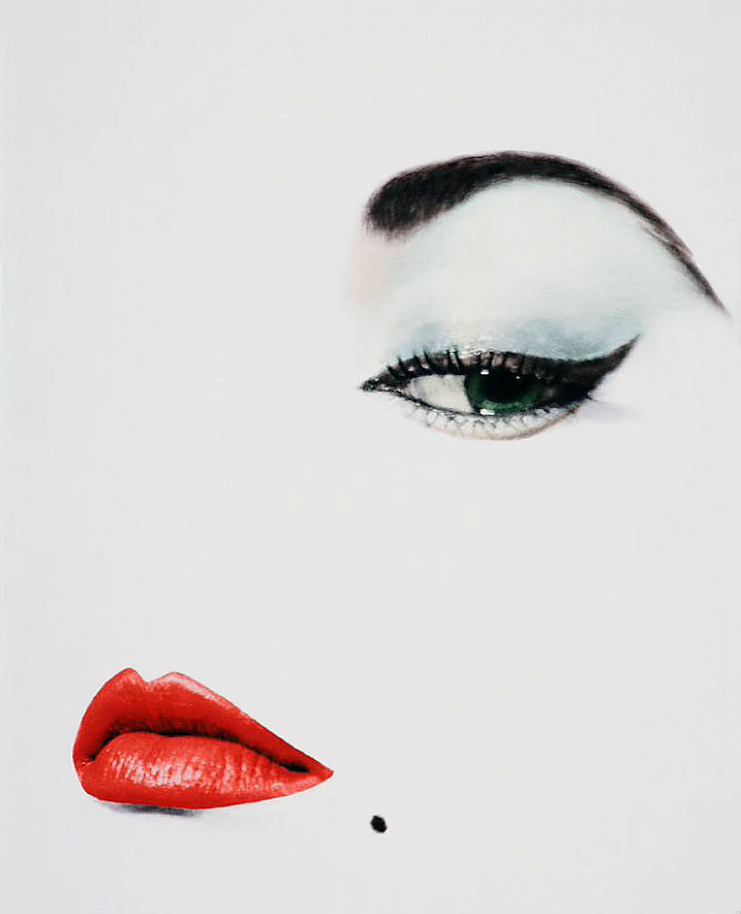

WAIT. Don’t reach for a drink. Don’t reach for your glasses. And don’t – please don’t – write us an indignant letter. What you think you see on these pages is there, all right. It’s the work of a zany photographer named Weegee (few know his first name) who has a wicked sense of caricature and an outrageous sense of humor.

The subjects were not photographed under water. Wedge simply prints his negatives through bubbles glass, wire screens, press, kaleidoscopes or whatever gives him the characterization he is after. It’s a sort of three-way-stretch technique in which Weegee is assisted by photographic color expert Mike Lavelle.

The results of Weegee’s impudent manipulation of reality are both perceptive and astonishing: Faces take on a certain ga-ga verity; external exaggeration high-lights internal character and distortion offers surprising insights into personality. Weegee calls this “Photo-Caricature.” There was a man who might have enjoyed revelations like these. His name was Bobbie Burns and he wrote in one of his poems: “O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us to see oursels as others see us.”

“How your TV heroes look to Weegee’s magic camera” in Look magazine

“”Modern Women Aren’t Human!’ … If You Don’t Believe It … This Man Tells Why” in the National Enquirer, 1967

There’s a mystery to Weegee. The American photographer’s career seems to be split in two. One side includes his sensational photography printed in North American tabloids: corpses of gangsters lying in pools of their own blood, bodies trapped in battered vehicles, kingpins looking sinister behind the bars of prison wagons, dilapidated slums consumed by fire, and other harrowing documents on the lives of the underprivileged in New York from 1935 to 1945. Then come the festive photographs – glamorous parties, performances by entertainers, jubilant crowds, openings and premieres – to which we must add a vast array of portraits of public figures that Weegee delighted in distorting using a rich palette of tricks between 1948 and 1951, a practice he pursued until the end of his life. How can these diametrically opposed bodies of work coexist? Critics have enjoyed highlighting the opposition between the two periods, praising the former and disparaging the latter. The exhibition Autopsy of the Spectacle seeks to reconcile the two parts of Weegee by showing that, beyond formal differences, the photographer’s approach is critically coherent.

The spectacle is omnipresent in Weegee’s work. In the first part of his career, which coincides with the rise of the tabloid press, he was an active participant in transforming news into spectacle. To show this, he often included spectators, or other photographers, in the foreground of his images. In the second half of his career, Weegee mocked the Hollywood spectacular: its ephemeral glory, adoring crowds and social scenes. Some years before the Situationist International, his photography presented an incisive critique of the Society of the Spectacle.

With a new perspective on Weegee’s oeuvre, Autopsy of the Spectacle presents the photographer’s iconic images beside lesser-known works, including images not-yet-exhibited in France.

Curator Clément Chéroux

Press release from the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Their First Murder

c. 1936

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive / International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Drowning victim, Coney Island

c. 1940

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive / International Center of Photography, New York / Collection Galerie Berinson, Berlin

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Mrs Bernice Lythcott and her son Leonard looking through a window broken by stones thrown by thugs, Harlem, New York

October 18, 1943

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]

May 23, 1941

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Son of a Jewish immigrant from Ukraine, Weegee knew the slums, like those children seeking coolness on the fire escape ladder. He produced “real social documents” on the living conditions of the poor.

“In Central Park the lawns were crowded before darkness with family groups,” reported the July 10, 1936 New York Times; the temperature had reached an astounding 106 degrees the day before. “On the Lower East Side traffic was seriously impeded as small armies of persons emerged from tenement houses with chairs, boxes and even beds which they set up in the streets.”

And from the Times on August 4, 1938, when the mercury hit 93 degrees:

“More than 3,000 persons slept on the sand at Coney Island and Brighton Beach to escape the heat last night, the police estimated. Ten additional patrolmen were assigned to the area to prevent molestation of the sleepers, many of whom brought blankets and sheets.”

Anonymous. “How New Yorkers survived hot summer nights,” on the Ephemeral New York website Nd [Online] Cited 14/04/2024

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]

1947

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Simply adding boiling water

1943

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

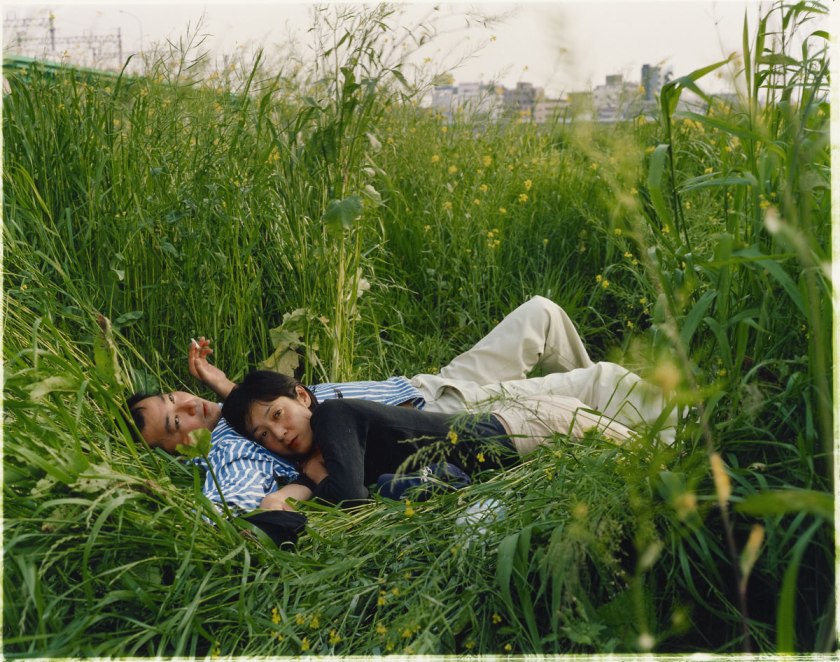

Lovers at the Palace Theater

c. 1953

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Anthony Esposito, Booked on Suspicion of Killing a Policeman

1941

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography. Louis Stettner Archives, Paris

At noon Fifth Avenue was crowded. Alfred Klausman, middle-aged office manager of a linen firm, walked across the street from his office to the bank on the corner and drew the weekly pay roll: $649.

As the genial, round-faced Klausman walked back, two men silently threaded through the crowd behind him, two strange, grey-coated creatures washed up from the depths of New York City’s criminal world. One was Anthony Esposito, 35, a long-nosed, horse-faced hoodlum who had been in & out of New York’s prisons and reformatories for 16 years, had once been deported to Italy and sneaked back in. His brother William, 29, had robbed drunks, snatched pocketbooks, done a seven-year stretch in Sing Sing. Their father had served time for forgery. Their brother was in Clinton Prison, Dannemora, N. Y. for parole violation. Their lives had been spent in squalor, petty crime, prison and torpid, hard-eyed loafing.

Klausman entered the elevator to his office. The Esposito brothers stepped in after him. Between the second and third floors they drew revolvers from their overcoat pockets, ordered the operator to stop, face the door. He heard Klausman cry “No! No! No!” – then one of the gunmen put his revolver to Klausman’s head and pulled the trigger.

They ordered the operator to take the elevator down, ducked out into the street, disappeared into B. Altman’s big department store.

Out into the street the operator yelled “Holdup! Murder!” The cry spread. Two patrolmen raced from the corner, into the store, a long way behind.

Down the crowded aisles of the store darted the Espositos, through the block-long building. At the far entrance they climbed into a cab, put a gun at the driver’s head. But Madison Avenue was jammed with traffic; they were trapped. “Get going. Make it fast. Get moving or we’ll kill you.” Back in the store panic was spreading as police with drawn revolvers moved down the aisles shouting, “Get down!” The cab stalled behind a bus. Like men leaping over a cliff, the brothers jumped out into the traffic. At sight of the two running men, waving revolvers, people flattened themselves against the buildings or ducked to the sidewalk. A taxi driver ran to Patrolman Edward Maher, directing traffic on the corner, yelled “Stick-up!” and pointed at the fleeing men. Maher raced after them, only 20 feet behind, afraid to shoot into the crowd. Motorists left their cars and joined the chase. Maher saw a clear space, shot twice, and William Esposito staggered sideways, fell face downward, one arm outstretched, one twisted under him, apparently dead.

A little crowd collected around him. Patrolman Maher held the gunman by the overcoat, started to turn him over, turned to warn the crowd away. “Back up, please,” he said, “someone’s liable to get hurt.” As he rolled William over, the gunman’s .38 came up. William Esposito pulled the trigger and Patrolman Maher slumped over, dead.

The crowd surged back, then forward. A taxi driver named Leonard Weisberg leaped on the prone gunman. He grabbed for the revolver, missed. Esposito jerked it back a few inches, fired again. Weisberg, clutching his throat, gasping for breath, fell to the sidewalk.

Esposito, still lying down, drew another gun from his overcoat pocket. Two men leaped on him. Then the crowd closed in, kicking and beating.

Anthony ran on when his brother fell. Behind him the police fired into the air. He shot a few times, wildly, apparently to clear crowds out of his way on Fifth Avenue. He ducked into Woolworth’s, bowling over the women shoppers. He plunged to the basement, put away his guns, walked up again to hide in the crowd – and met six policemen at the head of the stairs, went down with revolver butts thudding on his skull.

The Espositos went to the hospital, to the lineup, to indictment for murder. Leonard Weisberg, recovering from his throat wound, was promised a new cab of his own, and won a hero’s praise. The Nazi press gleefully played up the crime as evidence of democratic depravity.

Anonymous. “National Affairs: SLAUGHTER ON FIFTH AVENUE,” in TIME Monday, Jan. 27, 1941 on the TIME website [Online] Cited 14/04/2024

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 – 1968 New York)

[Outline of a Murder Victim]

1942

Gelatin silver print

33.9 x 27.4cm (13 3/6 x 10 13/16 in.)

Gift of Bruce A. Kirstein, in memory of Marc S. Kirstein, 1978

© Weegee / International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Harry Maxwell shot in a car

1941

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

“Hopper’s Topper” Hedda Hopper Hollywood

c. 1948

Gelatin silver print

© Photo Weegee/ICP New York

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Marilyn Monroe, Distortion

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

© Weegee Archive / International Center of Photography, New York / Friedsam Collection, Frankfurt am Main

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Charlie Chaplin, Distortion

1950

© International Center of Photography

Weegee (American, 1899-1968)

Self-Portrait

1963

Gelatin silver print

© International Center of Photography

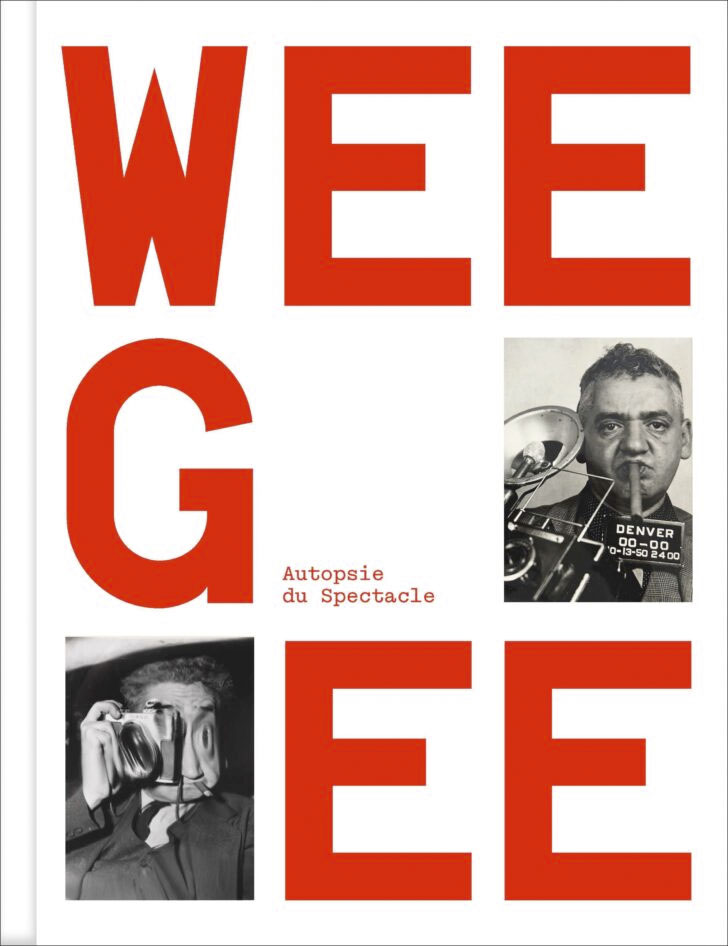

Weegee (author)

Textual, Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation (editor)

January, 2024 (release)

ISBN 9782845979901

208 pages

55 euros

This book accompanies the exhibition Weegee, Autopsie du Spectacle presented from January 30, 2024 to May 19, 2024 at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation.

There is a Weegee conundrum. His photographs fall into two distinct categories. On the one hand, there are his images of news items taken in New York during the 1940s, in a documentary, direct and raw approach. And on the other, photographs of starlets, politicians and other socialites taken in Hollywood in the following decade, for which he willingly resorted with special effects. Declaring himself “bewitched by the mystery of the murders,” Weegee stood out for his ability to arrive promptly at the crime scene or to wait for the salad baskets to arrive on the steps of the police stations to capture the defendants on the spot. Nevertheless, he strives to bring onlookers, often from the working classes, into his framework, or even to be interested only in them. Made up of around a hundred photographs – the best known, but also many images never highlighted – this book shows the coherence of Weegee’s work based on a radical and incisive critique of the Society of the Spectacle, borrowing from an unexpected empathy towards the disadvantaged.

Weegee (1899-1968) was an American photojournalist known for his images of a New York marked by crime. In 1941, New York’s Photo League dedicated an exhibition to him which was followed by that of MoMA in 1943. He published his first book Naked City in 1945 and his autobiography Weegee by Weegee in 1961.

Hardcover

20 x 26cm

Texts by Isabelle Bonnet, David Campany,

Clément Chéroux and Cynthia Young.

Texts in French

Translated from the French by Google Translate from the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson website

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson

79 rue des Archives

75003 Paris

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed Mondays

![Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939 Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-a.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941) Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2024/05/weegee-installation-hcb.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-untitled-young-man-smoking-cigarette-in-crashed-car-while-waiting-for-ambulance-new-york-1941.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-tenement-sleeping-during-heat-spell-lower-east-side-new-york.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-fire-in-loft-building.jpg)

![Weegee (American, born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 - 1968 New York) '[Outline of a Murder Victim]' 1942](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/weegee-outline-web.jpg?w=840)

![John F. Collins (American, 1888-1990, active 1904-1974) '[Kodak Ektra Camera]' c. 1930 John F. Collins (American, 1888-1990, active 1904-1974) '[Kodak Ektra Camera]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/collins-camera.jpg?w=840)

![Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Self-portrait preparing a Collodion plate]' 1856-1859 Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Self-portrait preparing a Collodion plate]' 1856-1859](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/ifthecamera2.jpg?w=650&h=802)

![George Watson (American, 1892-1977) '[Camera on 12-foot Tripod]' 1920s George Watson (American, 1892-1977) '[Camera on 12-foot Tripod]' 1920s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/ifthecamera7.jpg?w=650&h=811)

![Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) '[Self-Portrait with Camera]' 1932 Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) '[Self-Portrait with Camera]' 1932](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/ifthecamera3.jpg?w=650&h=834)

![Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989) '[Self-Portrait]' 1932 Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989) '[Self-Portrait]' 1932](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/alma-lavenson.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Portrait of Dorothea Lange]' 1937 Unknown photographer (American) '[Portrait of Dorothea Lange]' 1937](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/dorothea-lange.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web2.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web9.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 compilation of three Weegee crime scene photographs Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 compilation of three Weegee crime scene photographs](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web1-and-6b.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web6.jpg?w=650&h=841)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web1.jpg?w=650&h=866)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web3.jpg?w=650&h=876)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 compilation of two Weegee crime scene photographs Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 compilation of two Weegee crime scene photographs](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web4-and-5.jpg?w=650&h=1573)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web4.jpg?w=650&h=939)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web5.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web7.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930 Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Crime scene]' c. 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/08/weegee-a-group-of-9-crime-scene-photographs-c-1930-web8.jpg?w=840)

![Platt D. Babbitt. '[Scene at Niagara Falls]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/platt_d_babbitt_scene_at_niagara_falls-web.jpg?w=840)

![Camille Silvy. 'Group of their Royal Highnesses the Princess Clementine de Saxe Cobourg Gotha, her Sons and Daughter, the Duke d'Aumale, the Count d'Eu, the Duke d'Alencon, and the Duke de Penthievre [in England]' 1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/camille-silvy-group-of-their-royal-web.jpg?w=840)

![Camille Silvy. 'Group of their Royal Highnesses the Princess Clementine de Saxe Cobourg Gotha, her Sons and Daughter, the Duke d'Aumale, the Count d'Eu, the Duke d'Alencon, and the Duke de Penthievre [in England]' 1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/camille-silvy-group-of-their-royal-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Man Ray. '[Marcel Duchamp and Raoul de Roussy de Sales Playing Chess]' 1925](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/gm_05332701-web.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig). '[Summer, The Lower East Side, New York City]' Summer 1937](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/gm_04304601-web.jpg?w=840)

![André Kertész. '[Underwater Swimmer]' Negative 1917; print 1970s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/gm_06225401-web.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer. '[Barnum and Bailey Circus Tent in Paris, France]' 1901-1902](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/gm_05045201-web.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Anthony Esposito, booked on suspicion of killing a policeman, New York]' January 16, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/3-weegee_anthony-esposito-web.jpg?w=655&h=509)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/17-weegee_19982_1993-web.jpg?w=840&h=672)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/6-weegee_19969_1993-web.jpg?w=840&h=671)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/15-weegee_19961_1993-web.jpg?w=840&h=676)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Installation view of "Weegee: Murder Is My Business" at the Photo League, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/16-weegee_19972_1993-web.jpg?w=655&h=523)

![Weegee. 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' ca. 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled ["Ruth Snyder Murder" wax display, Eden Musée, Coney Island, New York]' ca. 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/5-weegee_7221_1993-web.jpg?w=840&h=674)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943 Weegee. 'Untitled [Hats in a pool room, Mulberry Street, New York]' c. 1943](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/14-weegee_15595_1993-web.jpg?w=840&h=669)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936 Weegee. 'Untitled [Body of Dominick Didato, Elizabeth Street, New York]' August 7, 1936](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/8-weegee_2070_1993-web.jpg?w=821&h=1024)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941 Weegee. 'Untitled [Police officer and lodge member looking at blanket-covered body of woman trampled to death in excursion-ship stampede, New York]' August 18, 1941](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/11-weegee_1016_1993-web.jpg?w=825&h=1024)

![Weegee. 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943 Weegee. 'Untitled [Police officer and assistant removing body of Reception Hospital ambulance driver Morris Linker from East River, New York]' August 24, 1943](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/9-weegee_133_1982-web.jpg?w=808&h=1024)

![Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, born Austria, 1899-1968) '[Lovers at the Movies, Times Square]' c. 1953](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/weegee-lovers-1953.jpg?w=840)

![Weegee (Arthur H. Fellig). '[Marilyn Monroe]' c. 1950s Weegee (Arthur H. Fellig). '[Marilyn Monroe]' c. 1950s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/weegee-marilyn-monroe.jpg?w=840&h=1020)

You must be logged in to post a comment.