Exhibition dates: 29th October 2020 – 31st January 2021

Curator: Dr Patricia Berman

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

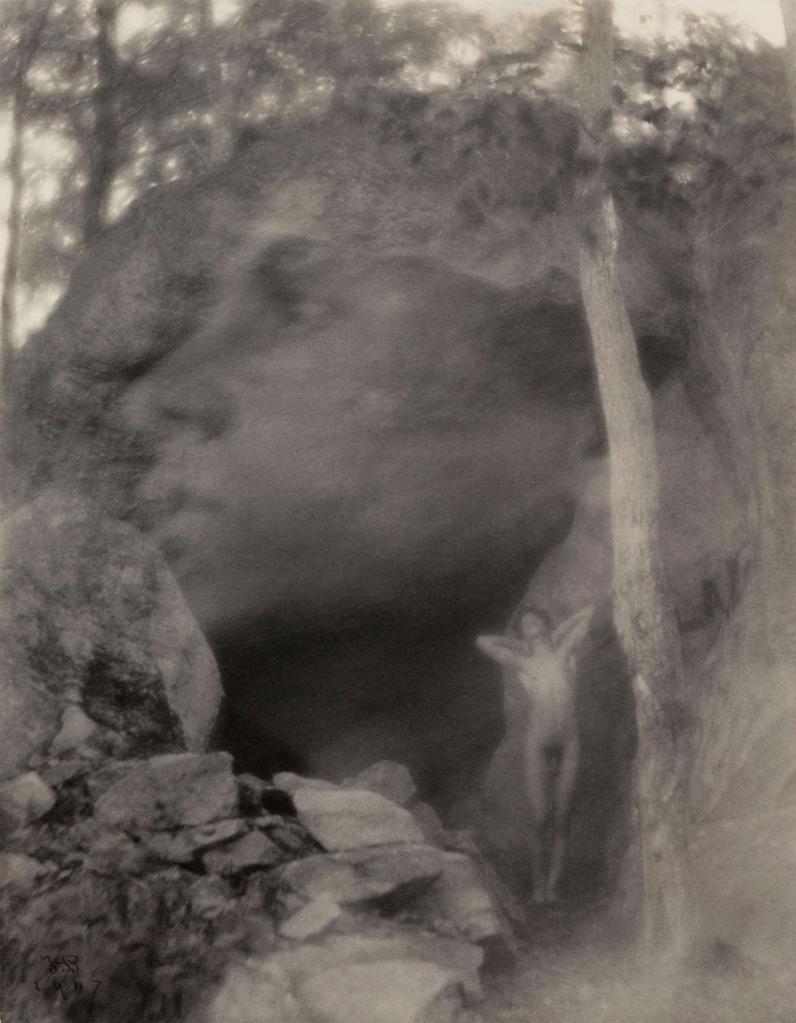

Self-Portrait in Åsgårdstrand

1904

Silver gelatin contact print

The camera is located so close to Munch that his looming head is out of focus. Reversing photographic norms, the background is in sharp focus, revealing a chest that had been given to the artist by his on-and-off-girlfriend Tulla Larsen, and a lithograph tacked to the wallpaper above it – a bitterly satirical commentary on their relationship.

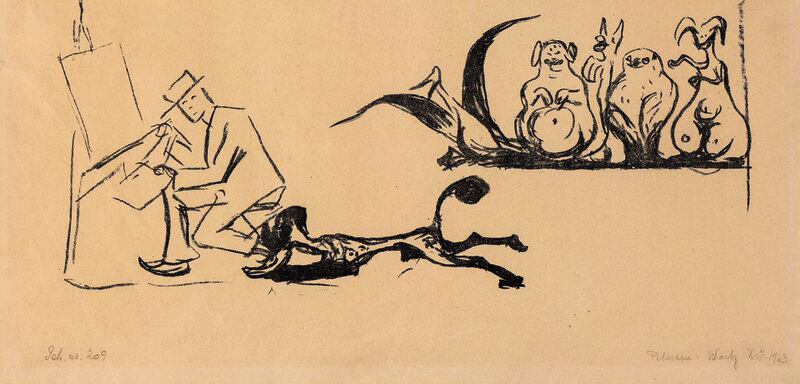

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Caricature: The Assault

1903

Lithograph printed in black on medium heavy cream paper

Sheet: 237 x 487mm

Image: 180 x 415mm

Munch says to a woman friend – “What do you think of me?”

She says, “I think you are the Christ”

Peter Watkins (director) Edvard Munch (film) 1974

The semi-transparent self

What a fascinating study of an artist in motion – physically and spiritually.

Through his informal, experimental photographs, Munch explores issues of identity and self-representation, friendship, work and location. In his photographs, he “assumes a range of personalities, from the vulnerable patient at the clinic to the vital, naked artist on the beach”, many of which undermine “the function of a camera as a straight-forward documentary tool.”

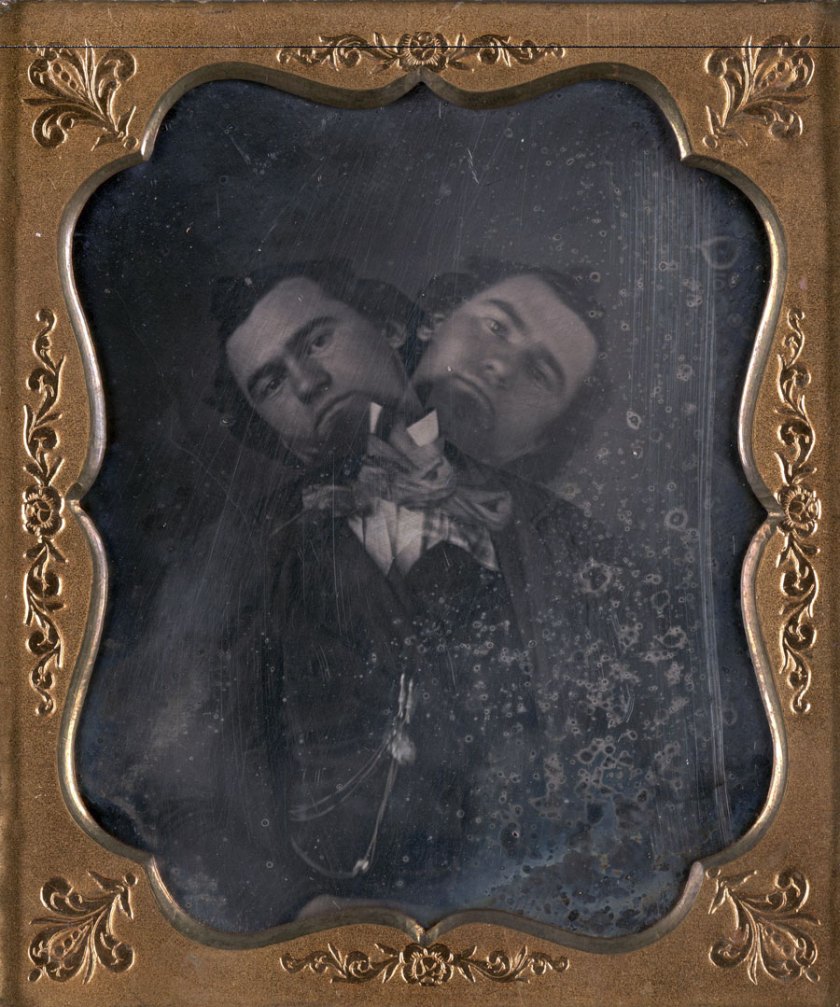

“Faulty” focus, distorted perspectives and eccentric camera angles combined with low and selective depth of field allow Munch to create a body of self-images in which “the artist himself appears in some pictures as a shadow or a smear rather than a physical presence.” There is a subtle mystery to much of the artist’s photographic work, a sense of loneliness and isolation trading off visions of heroic creatures; mirror images questioning the stability of him/self playing off the vitalism of male body culture; and variations of melancholy opposing a better life which lay in nature and good health, stages in the theatre of life.

His ghost-like, semi-transparent self-image appears as if seen in a far off dream – flickering images in light – out of space and time / asynchronous with the effects of time and motion.

What strong, e-motionless photographs of self these are. Here is observation but not self pity. Here is Munch investigating, probing, the mirror stage of “the formation of the Ego via the process of identification, the Ego being the result of identifying with one’s own specular image.”1 (Lacan). Munch explores the tension between the subject and the image, between the whole and fragmented body as revealed in psychoanalytic experience, seeking access to representations of the unified self, in order to understand the human condition, of becoming. Who am I? How am I represented to myself, and to others?

The attempt to locate a fixed subject proves ever elusive. “The mirror stage is a drama… which manufactures for the subject, caught up in the lure of spatial identification, the succession of phantasies that extends from a fragmented body-image to a form of its totality.” (Écrits 4). With its link to a belief in spiritualism (popular in his day), Munch speculates that if we had different eyes we would be able to see our external astral casing, our different shapes. The exhibition text notes, “It is easy to read his layered, flickering images in light of such speculation.” Indeed it is. But the spectres that haunt Munch’s photographs are as much grounded in the reality of the everyday struggle to live a life on earth as they are in the spirit world. They are of the order of something, something that haunts and perturbs the mind, a questioning as to the nature of the self: am I a good person, am I worthy of a good life, where does the path lead me. I have been there, I am still there, I know his joy and pain.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ The specular image refers to the reflection of one’s own body in the mirror, the image of oneself which is simultaneously oneself and other – the “little other”.

Many thankx to the National Nordic Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Internationally celebrated for his paintings, prints, and watercolours, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) also took photographs. This exhibition of his photographs, prints, and films emphasises the artist’s experimentalism, examining his exploration of the camera as an expressive medium. By probing and exploiting the dynamics of “faulty” practice, such as distortion, blurred motion, eccentric camera angles, and other photographic “mistakes,” Munch photographed himself and his immediate environment in ways that rendered them poetic. In both still images and in his few forays with a hand-held moving-picture camera, Munch not only archived images, but invented them.

On loan from the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway, the 46 copy prints in the exhibition and the continuous screening of the DVD containing Munch’s films are accompanied by a small selection of prints from private collections, as well as contextualising panels and others that examine Munch’s photographic exploration. Similar to the ways in which the artist invented techniques and approaches to painting and graphic art, Munch’s informal photography both honoured the material before his lens and transmuted it into uncommon motifs.

” … these photographic images of the artist rise to the level of what Munch called “selfscrutinies”: emotional but hard-edged, and pierced with a dread of modern life that has outlived the Modernist era.” ~ New York Times

” … an unfinished playfulness with technical manipulation and subject matter that is not as readily seen in Munch’s more well-known work” ~ Hyperallergic

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nurse at the Clinic, Copenhagen

1908-1909

Scan from negative

One of the nurses at Daniel Jacobson’s clinic in Copenhagen posed in a fontal manner that mirrors representations of women throughout Munch’s work. The slight movement of the camera blurs the figure and her surroundings, undermining the function of a camera as a straight-forward documentary tool.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nurse at the Clinic, Copenhagen

1908-09

Silver gelatin contact print

After a successful run at New York’s Scandinavia House that received great reviews from New York Times and others, the photography of Edvard Munch is currently on display at the National Nordic Museum in Seattle now through January 31, 2021. Curated by distinguished Munch scholar, Dr. Patricia Berman of Wellesley College, The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography presents works from the rich collection of Oslo’s Munch Museum and shares new research on one of the most significant artists of his day.

“After displaying the journalistic photography of Jacob Riis this spring and discussing a picture’s power to change lives, it is wonderful to host another celebrated Nordic artist whose photography reflects the artistic potential found in the camera of the late 19th and early 20th century,” said Executive Director / CEO Eric Nelson.

Internationally celebrated for his paintings, prints, and watercolours, Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) experimented with both still photography and early motion picture cameras. The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography displays his photographs and films in a way that emphasises the artist’s exploration of the camera as an expressive medium. By probing and exploiting the dynamics of “faulty” practice, such as distortion, blurred motion, eccentric camera angles, and other photographic “mistakes,” Munch photographed himself and his immediate environment in ways that rendered them poetic.

“In many ways, these works reveal an unknown Munch,” said Leslie Anne Anderson, Director of Collections, Exhibitions, and Programs at the National Nordic Museum. “The photographs were never displayed during the artist’s lifetime, and this exhibition invites visitors to peer into the keyhole of Munch’s private life.”

Press release from the National Nordic Museum

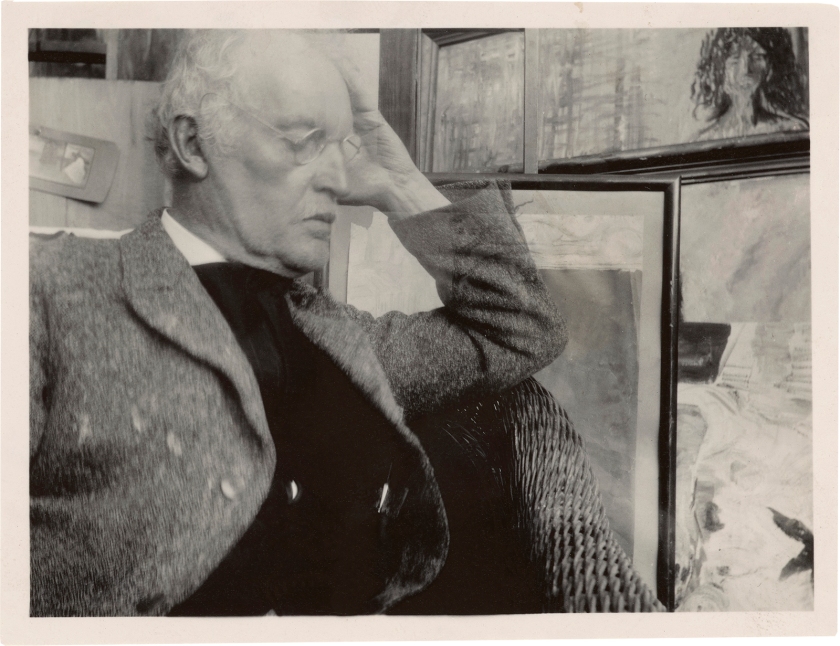

Ragnvald Vaering

Munch in his Winter Studio in Ekely on his seventy fifth birthday

1938

Silver gelatin contact print

Introduction: The Experimental Self

Edvard Munch was among the first artists in history to take “selfies.” Like his paintings, prints and writings, his amateur photographs are often about self-representation. Munch assumes a range of personalities, from the vulnerable patient at the clinic to the vital, naked artist on the beach. Sometimes he staged himself and people around him almost theatrically. Munch pursued his informal photography as an experimental medium, just like his paintings and prints. The artist himself was more than often the experimental subject. This exhibition, containing around 60 photographs and movie fragments in dialogue with graphic works, highlights the connection between Munch’s amateur photography and his more recognised work as an artist.

Munch took up photography in 1902, months before he and his lover Tulla Larsen ended a multi-year relationship with a pistol shot that mutilated one of his fingers. This event, and an accelerating career, triggered a period of increasing emotional turmoil that culminated in a rest cure in the private Copenhagen clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson in 1908-09. After a pause of almost two decades, Munch picked up the camera again in 1927. This second period of activity lasted into the mid-1930s and was bracketed by triumphant retrospective exhibitions in Berlin and Oslo but also by a haemorrhage in his right eye, temporarily impairing his vision. This was also the time that Munch tried his hand at home movies.

Unlike his prints and paintings, however, Munch did not exhibit his tiny, copy-printed photographs. Yet he wrote in 1930, “I have an old camera with which I have taken countless pictures of myself, often with amazing results … Some day when I am old, and I have nothing better to do than write my autobiography, all my self-portraits will see the light of day again.”

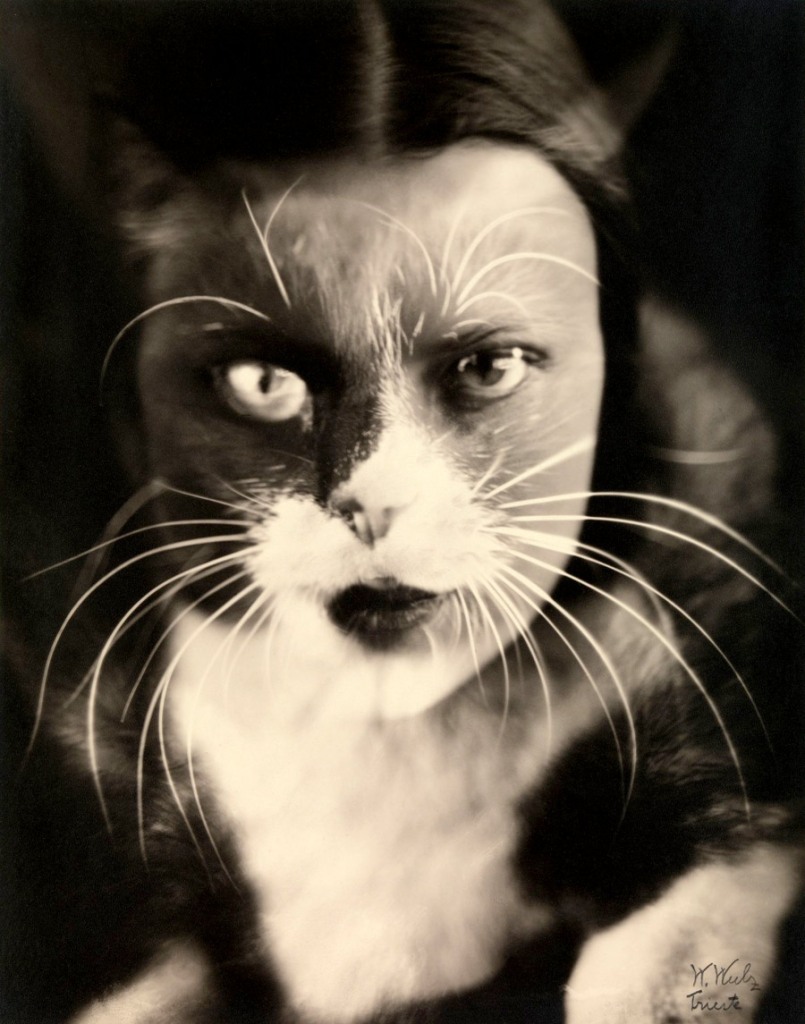

The Amateur Photographer

Munch’s photographs are often out of focus, and the artist himself appears in some pictures as a shadow or a smear rather than a physical presence. As an amateur photographer, he seems to have exploited the expressive potential in photographic “mistakes” such as “faulty” focus, distorted perspectives and eccentric camera angles. By including the platforms on which he stabilised his small, hand-held camera, he created out-of-focus, undefined areas cutting across the foreground. What may have begun as accidents, eventually became a habitual element in his work.

In many of his self-portrait photographs, Munch moved during the camera’s exposure time, transforming his own body into a ghost-like figure. In the photographs from his studio, Munch and his work seem to exist out of space and time with one another. He often experimented with such effects: “Had we different, stronger eyes,” wrote Munch, “we would be able, like X-rays … to see our external astral casing – and we would have different shapes.” It is easy to read his layered, flickering images in light of such speculation. On the other hand, Munch also regarded his self-images with humour. Writing to his relative Ludvig Ravensberg in June 1904, he confessed: “When I saw my body photographed in profile, I decided, after consulting with my vanity, to dedicate more time to throwing stones, throwing the javelin, and swimming.”

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait on a Valise in the Studio, Berlin

1902

Collodion contact print

Munch took up photography in 1902, the same year that this picture was taken. There are three preserved versions of the motif, with subtle variations. Munch sent two of the images to his aunt Karen in Norway with the description: “Here are two photographs taken with a little camera I procured. You can see that I have just shaved off my moustache.”

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait on a Valise in the Studio, Berlin

1902

Collodion contact print

The artist stages himself amidst his paintings (see below) in the studio he rented in Berlin at the time. The valise doubles as furniture and a symbol of Munch’s restless nature – he was often on the move.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Evening on Karl Johan

1892

Oil on canvas

84.5cm (33.2 in) x 121cm (47.6 in)

KODE, Rasmus Beyers samlinger

Public domain

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

The Back Yard at 30B Pilestredet, Kristiania

1902(?)

Silver gelatin contact print

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nude Self-Portrait, Åsgårdstrand

1903

Collodion contact print

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

The Courtyard at 30B Pilestredet, Kristiania

1902(?)

Silver gelatin contact print

This is assumed to be one of Munch’s earliest photographs, taken in one of his childhood homes. An inscription on the back reads “Outhouse window. 30-40 years old. Photograph of Pilestredet 30. A swan on the wall.” The swan that Munch refers to is actually a stain on the wall by the door. Can you see it? In moving the camera during the exposure, Munch erased the communal outhouse of his childhood and transformed it into a kind of dream image. This effect was later explored in avant-garde photography.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Karen Bjølstad and Inger Munch on the steps of 2 & 4 Olaf Ryes Plass, Kristiania

1902(?)

Silver gelatin contact print

Munch has photographed his aunt Karen and his sister Inger on the steps of one of his childhood homes in Oslo. The camera is stabilised on a flat surface that dominates the foreground of the image. This is the case in several of Munch’s photographs, perhaps to mark the camera’s position, create a sense of distance and frame the subjects. What likely began as the accident of an amateur eventually became an aesthetic choice.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nude Self-Portrait, Åsgårdstrand

1904(?)

Collodion contact print

In the summer of 1904, Munch organised an informal “health vacation” for several of his friends in Åsgårdstrand by the Oslo fjord. Munch had owned a small fisherman’s cabin there since 1898. In that period, he worked on the painting Bathing Young Men. Munch described to his relative and close associate Ludvig Ravensberg “a huge canvas … ready to be populated by the strong men wandering among the waters. Here we train our muscles by swimming, boxing, and throwing rocks.”

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Ludvig Ravensberg in Åsgårdstrand

1904

Collodion contact print

Ludvig Ravensberg was Munch’s close friend and relative who helped him organise exhibitions and get other practical work done. He also assisted Munch when the artist took some of his self-portraits in Åsgårdstrand. Here Ravensberg gets to pose in front of the camera himself.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait in the Garden, Åsgårdstrand

1904

Collodion contact print

Was this picture taken by Munch himself or another person? The filtered light, the human shadow projected onto Munch’s body and the dynamics of his pose help set the stage for the subtle mystery.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

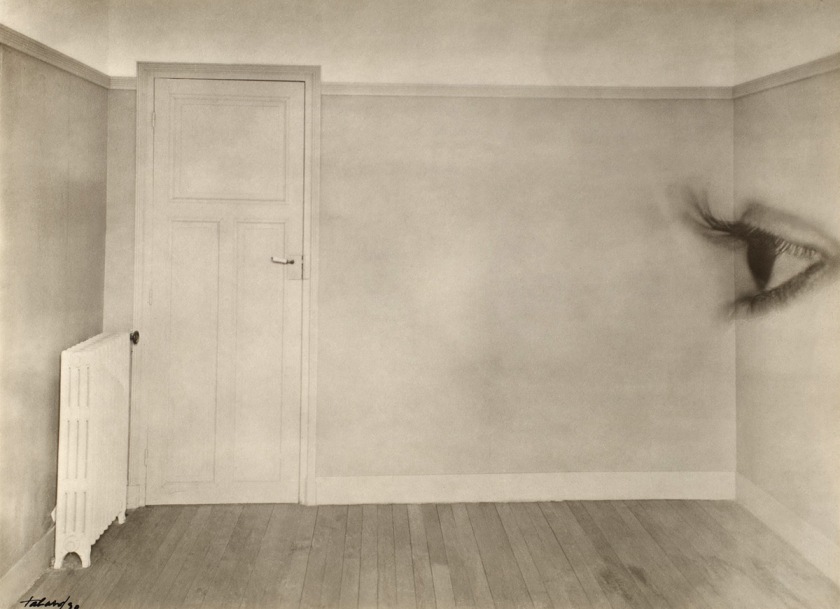

Self-Portrait in a Room on the Continent

1906(?)

Silver gelatin contact print

This photograph exists in two versions. One mirrors the other, probably a result of Munch flopping the negative as he developed the picture. The mirroring of motifs is something Munch often explored in his graphic work, such as the woodcuts Evening. Melancholy and Melancholy III – perhaps a dynamic he wanted to emulate in his photography. Chemical stains on the print testify to Munch’s hands-on approach to development and printing. In contrast to the products of a commercial printing house, he was not terribly concerned with a perfect print.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait in a Room on the Continent (mirrored)

1906(?)

Silver gelatin contact print

Edvard Munch, Berlin (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

M.W. Lassally, Berlin (printer)

Evening. Melancholy I (Aften. Melankoli I)

1896

Woodcut

Composition: 16 1/4 x 18″ (41.2 x 45.7cm)

Sheet: 16 15/16 x 21″ (43 x 53.3cm)

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Melancholy III (Melankoli III)

1902

Woodcut with gouache additions

Composition: 14 3/4 x 18 9/16″ (37.5 x 47.2cm)

Sheet: 20 1/2 x 25 7/8″ (52 x 65.8cm)

Variations of Melancholy

Edvard Munch made his first woodcuts and lithographs in 1896. He mastered an innovative technique in which he used the wood grain to emphasise his own lines. Using this technique, he created a number of related woodcuts on the theme of melancholy, including Evening. Melancholy I (1896), in which the brooding figure sits facing right, under an imposing crimson sky.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch and Ludvig Ravensberg, Åsgårdstrand

1904

Collodion contact print

Munch used himself and his friends as models for his canvas Bathing Men. Here is a description by his friend Christian Gierløff: “The sun baked us all day and we let it do so. Munch worked a little on a painting of bathers, but for most of the day, we lay, overcome by the sun, in the sand by the water’s edge, between the large boulders, and we let our bodies drink in all of the sun they could. No one asked for a bathing suit.”

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

The Painting “Bathing Young Men” in the Garden, Åsgårdstrand

1904

Collodion contact print

Several photographs from the summer of 1904 picture Munch’s painting Bathing Young Men. Shadows cast by leaves at the upper left of the painting seem integral to canvas and have the effect of linking the painting to its natural surroundings. Ludvig Ravensberg stands on the extreme right, seemingly holding the painting. The out-of-focus foreground, the painted figures, and the living man holding the canvas aloft document not only the painting but, playfully, photographic representation itself.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Bathing Young Men

1904

Oil on canvas

Munch Museum

Public domain

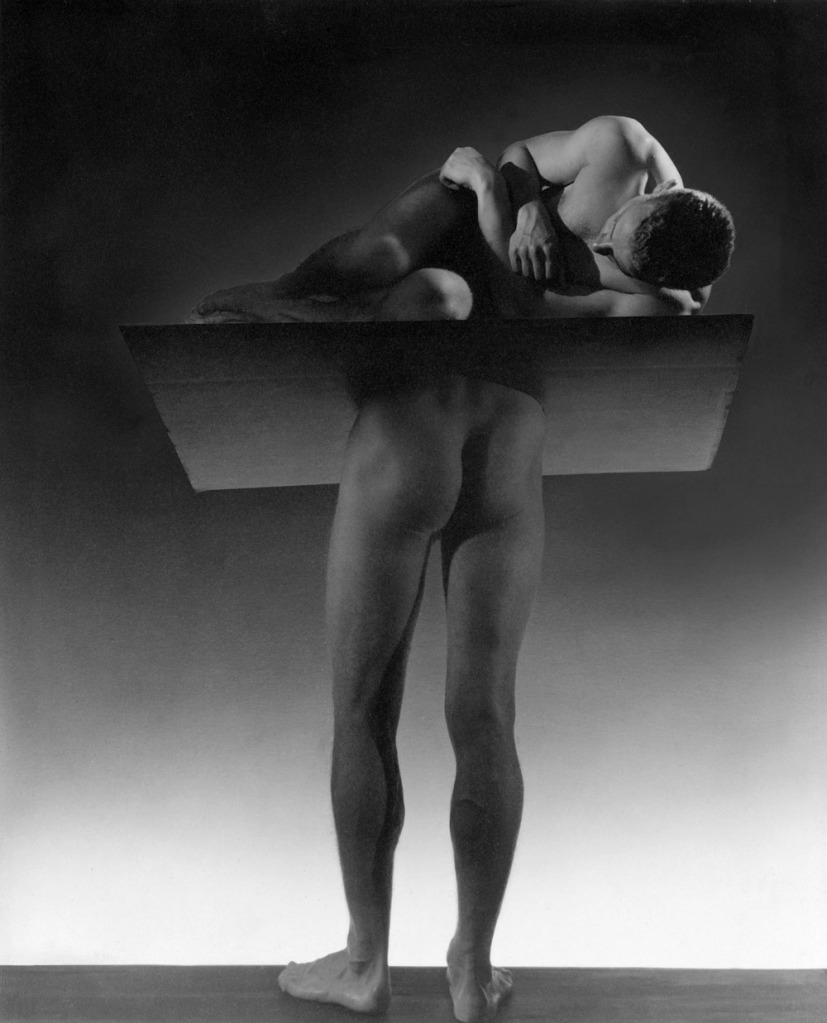

Bathers were a popular subject around the turn of the last century. Sojourns at health spas were fashionable and people pursued sports, nudism and the healthful effects of the natural environment. It was seen as cleansing to bathe in the sea, while the sun constituted a rejuvenating force of life.

In this painting we see a virile, muscular, naked man emerging from the cool, turquoise sea after a swim. The picture can be read as a reflection of the period’s “vitalism” – a world view that assumed all living things to be suffused with a magical life force. This philosophy found its pictorial expression in particular in dynamic motifs of naked men and youths.

As a cultural phenomenon, vitalism was a reaction against the decadence of the period, and against industrialism, with the great cities and ways of life it brought with it. Instead of cool-headed rationalism and scientific technology, vitalism preferred to emphasise instinct and intuition – and believed the key to a better life lay in nature and good health.

Text from the National Museum website

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Exhibition at Blomqvist, Kristiania

1902

Collodion contact print

Munch took this image of his one-man exhibition at the influential art dealer Blomqvist in 1902. He also recorded himself, standing in the background, out of focus, hands in his pockets, facing directly into the camera.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Model in the Studio, Berlin

1902

Collodion contact print

This is among the few photographs that directly relate to Munch’s work in paint and graphic media. There are two versions of the motif, and subtle variations suggest that the photographer himself might have offered some instructions.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nude with Long Red Hair

1902

Oil on canvas

A Record of Healing

Munch often photographed in times and places where he struggled with his health and sought new energy. The pictures from the town of Warnemünde on Germany’s Baltic Coast show him as part of male body culture and include images of the artist naked and semi-naked on the beach. Munch also took tourist shots with his female models on the sand during the summers he spent there in 1907 and 1908.

In autumn 1908, Munch checked into a private clinic in Copenhagen managed by the physician Daniel Jacobson and his nurses. Munch was broken down by exhaustion, distress and alcoholism. The clinic became his home for over half a year. Within its walls, he painted, drew, created graphic motifs, organised exhibitions and took photographs in which he consistently appears semi-transparent. In the pictures of Munch’s room at the clinic we often get a glimpse of his paintings and prints. Sometimes he seems to have staged his body in postures that echo these paintings.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Rosa Meissner at Hotel Rohn, Warnemünde

1907

Silver gelatin contact print

Most of Munch’s photographs cannot be firmly associated with specific artworks. This photograph is however closely related to the motif Weeping Woman, which Munch rendered in several oil versions, a lithograph and a sculpture. While the foreground figure has remained static, the figure in the background has moved. Blurred movement is specific to photography and film, a phenomenon that Munch exploited repeatedly in his photographs. The effect of motion reproduces the appearance of spirit photographs – the spectral bodies of the departed allegedly registered on photographic plates and film. Munch expressed interest in such photographs in the 1890s. Ghosts and spectres also began to appear in cinema in the medium’s infancy.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch and his Housekeeper, Warnemünde

1907

Collodion contact print

In this picture, Munch has exploited the effects of movement and time. His housekeeper in Warnemünde has moved during exposure and is out of focus. Munch himself is sharply rendered in the background, and at the same time barely present. He has perched on a dark sofa long enough to be registered in detail and then moved out of the camera’s range. He now appears almost as a ghost where both the couch and the back wall are visible through his body. This effect mirrors his experimentation with layered woodblock printing in his graphic work, in which figures appear embedded in wood graining.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch with Model on the Beach, Warnemünde

1907

Collodion contact print

This photograph stages the beach at Warnemünde as Munch’s outdoor studio. The painter is strategically covered beside his monumental canvas Bathing Men. The naked man is one of Munch’s models holding a pose depicted in the painting.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Bathing Men

1907-1908

Oil on canvas

206 x 227cm

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Nude Self-Portrait, Warnemünde

1907

Collodion contact print

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Canal in Warnemünde

1907

Collodion contact print

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait with a Valise

c. 1906

Collodion contact print

Back lit and smudged with chemicals, this photograph deviates from the instructions that accompanied the popular Kodak cameras intended for amateur use. Munch’s bodily envelopment by darkness and the light that dissolves the window in the background make this a staged image of isolation and longing. It echoes the mood and composition of the woodcut Evening. Melancholy I (above).

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch and Rosa Meissner on the Beach, Warnemünde

1907

Collodion contact print

Munch posed for this photograph with Rosa Meissner, a model with whom he had worked in Berlin and later in in Warnemünde. Rosa’s sister Olga Meissner, who appears in another photograph in the same location, may have taken the image. A similar picture exists with double exposure, perhaps as a result of instructions given by Munch himself.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch and Rosa Meissner, Warnemünde (mirrored)

1907

Collodion contact print

By flopping the negative Munch demonstrated a curiosity with the dynamics of motif. This is something he explored over many years when he translated one of his painted motifs into a graphic image – the result was always mirrored. Sometimes Munch went even further and mirrored the motif itself on the printing stone or block – just as he did with this negative.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait at the Clinic, Copenhagen

1908-09

Silver gelatin contact print

In the autumn of 1908 Munch suffered a psychological and physical collapse and sought treatment at the private Copenhagen clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson. He remained there for over half a year. Some years earlier, he had been wounded by a shot from his own pistol in a quarrel with his then lover Tulla Larsen. Munch’s voluminous writings attribute this event to the beginning of the decline for which he sought treatment. Here, the wounded hand is sharply focused in the foreground. Towards the end of his stay at the clinic, Munch painted a self-portrait which is related in posture and gesture, if not in mood, with this photograph.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait in the Clinic

1909

Oil on canvas

KODE, Rasmus Meyers samlinger

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch à la Marat at the Clinic, Copenhagen

1908-09

Silver gelatin contact print

Munch has staged himself semi-naked next to a bathtub, suggesting a reference to Jacques-Louis David’s canonical painting of the murdered French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat. Munch made several paintings with the title The Death of Marat. The photograph can also be seen in relation to Munch’s painting On the operating table, which he made following the accident that wounded his hand. Unlike in his heroically staged nude self-portraits from Åsgårdstrand and Warnemünde, Munch appears softened and vulnerable. Whether this is a homage or satire, we can only imagine.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

The Death of Marat

1907

Oil on canvas

The starting point for The Death of Marat was the harrowing break-up with Tulla Larsen, who Munch was engaged to from 1898 to 1902. During a huge quarrel at his summer house at Aagaardsstrand in 1902, a revolver went off by accident, injuring Munch’s left hand. Munch laid the lame on Tulla Larsen and the engagement was broken off. The episode developed into a trauma which was to haunt Munch for many years, and which he worked on in several paintings, such as The Death of Marat I and The Death of Marat II, also called The Murderess.

The title Death of Marat refers to the murder of the French revolutionary Jean Paul Marat who, in 1793, was murdered by Charlotte Corday when he was lying in the bathtub. This was a motif many artists had treated up through the years. Marat was often presented as a hero, whilst Corday was regarded as a traitor.

Text from the Google Arts and Culture website

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-portrait on the Operating Table

1902-03

Oil on canvas

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait with a Sculpture Draft, Kragerø

1909-10

Silver gelatin contact print

Following his return to Norway in 1909, Munch tried his hand at designing a monument for the centennial of Norway’s constitution. He identified this composition as “Old Mother Norway and Her Son.” It is one of the few informal images that picture the artist at work, or posing as though in the process of making his art.

Munch’s Selfies

When Munch picked up the camera again in 1927, after a pause of over fifteen years, he often posed in and around his life’s work at his home. The small size and flexibility of the popular camera models that he had chosen – about the size of a smartphone – made it easy to hold the apparatus in one hand and take a picture. Munch’s “selfies”, sometimes playful and always self-analytical, reveal a public life lived in private. They show us the artist outside of public scrutiny, as his camera recorded both staged and spontaneous moments of his everyday life. In his many self-portraits, we might recognise our own daily practices as we turn the camera back on ourselves.

In the late spring of 1930, Munch suffered a haemorrhage in his right eye, seriously compromising his vision. In that year, he created a series of “selfies.” In one photograph of great pathos, Munch closed his eyes, transforming his camera into both mirror and eye. “The camera cannot compete with brush and palette as long as it cannot be used in Heaven or in Hell,” Munch had written. With Munch’s eye closed and his aperture open, his own camera – disclosing both humour and pain – surely came close.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch’s Housekeeper, Ekely

1932

Silver Gelatin

In the years 1927-1932, during Munch’s second period of photographic activity, the artist almost exclusively took photographs of himself and his work. This is a rare exception. Munch’s housekeeper is posing in a doorway and is doubled as a reflection on the shiny table on which the artist placed the camera. In fact, the woman is tripled, as a light, located behind her, throws her shadow onto the door to her left. The shadowing and expressive use of the foreground seem to have been strategic – an electrical plug and cord, snaking around the door jamb, appear to lead to a light source behind the model.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait with Paintings, Ekely

1930

Silver gelatin contact print

In several of Munch’s pictures, his body is transparent or ghosted as he moved his body during a time exposure. The images in the background (below), on the other hand, are rendered sharply. Perhaps the photograph tells us something about how volatile a human life is, while art endures.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Woman with a Samoyed

1929-30

Watercolour

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait with Paintings, Ekely

1930

Silver gelatin contact print

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Fips on the Veranda, Ekely

1930

Silver gelatin contact print

This “self-portrait” with the artist’s dog together with his own shadow exploits the effects of architectural space and direct and reflected light. Charmingly, Fips’s head and right paw are perfectly aligned with the shadow of a wall and light thrown through its mullioned window. Munch often photographed motifs with his back to the sun, causing his shadow to fall into the frame. A similar exploration of shadows appears in his painting and prints, sometimes with foreboding or pathos, and sometimes, as seen here, with humour.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Double Exposure of “Charlotte Corday”, Ekely

c. 1930

Silver gelatin contact print

In this photograph of the painting Charlotte Corday, Munch appears almost as a ghost. To achieve this affect, he used double exposure, taking two pictures on top of each other. Shadow figures such as this were emblematic of an absent presence, a kind of haunting, in Munch’s work. What began as a “mistake” in amateur snapshot photography became a common motif in experimental photography of the 1920s and ’30s as well as macabre effects in horror films from the same period.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Charlotte Corday

1930

Oil on canvas

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait at Ekely

1930

Silver gelatin contact print

This is one of several prints that carries the words: “Photo: E. Munch 1931. After the eye disease.”

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait at Ekely

1930

Silver gelatin contact print

In this image Munch is a spectral presence through which his well-lit paintings materialise. A similar union of body and material is found in the paintings and graphics, where figures become enmeshed in paint drips or wood grain patterning. Here the artist seems to stage himself as a figure in Evening. Melancholy (see above), embodying the contemplative state of mind conveyed by the title.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Still Life with Cabbage and other Vegetables

1926-30

Oil on wooden panel

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Self-Portrait in front of “Metabolism”, Ekely

1931-32

Silver gelatin contact print

Munch stretches his arm outward and moves slightly to render himself out-of-focus. He appears almost transparent in this self-portrait at the feet of the figures in the painting Metabolism.

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Metabolism

1898-99

Oil on canvas

Munch’s Films

Munch’s short films can best be described as the charming experiments of an amateur. This was, however, an amateur with a long-term exploration of motion in art and photography. Electrified by cinema, Munch had even announced his intention of opening his own movie house. The short sequences he shot both mirror popular cinema, such as the films of Charlie Chaplin, and explore the industrial aesthetic of Dziga Vertov’s silent documentary Man with a Movie Camera from 1929.

Munch shot his “home movies” in the summer of 1927 using a Pathé-Baby camera that he had purchased in Paris. The portable device, which had come on the market in 1922, had helped to spark a surge of amateur home movies all over the world. The 9.5 mm projector that accommodated the film, and which Munch also owned, was likewise inexpensive and marketed for home projection. “Every decade extends the influence of cinema, enlarges its domain and multiplies its applications,” stated the Pathé promotional literature, ” …Today, in order to enter our home, it has made itself small, simple, affordable.”

Munch’s camera had a spring-loaded drive, rather than a hand-driven crank, allowing for a uniform recording speed and simplifying his act of filming. His fascination with the effects of time and motion are played out with humour and deliberation in his few forays into motion pictures. The artist peering into his own lens is a performance knowingly looking at a self that will be projected later, an actor in his large body of self-images.

Munch’s Films

1927

3:40

Munch’s short amateur films, stitched together in this video, were shot in Dresden, Oslo and on his property Ekely. One segment, a panning shot in a park, includes a man and woman seated on a bench, echoing Munch’s 1904 painting Kissing Couples in the Park. The high-angle shot of the boys looking through a fence, as we watch them, points to the artist’s canny and humorous analysis of point of view. Munch’s fragmentary films share the experimental camerawork with the genre of “city symphony” films of the 1920s.

Munch’s cameras

Munch purchased his first camera in Berlin in February 1902. This was most likely a Kodak Bulls-Eye No. 2, a simple and hugely popular amateur’s model. Because his later prints exist in three additional formats, he probably owned or borrowed other cameras. The first Kodak hand-held film camera was marketed in 1888. Successive innovations by Kodak made picture taking increasingly simple and inexpensive, establishing a mass market of amateur photographers. Early amateur photography was marketed as “fun” and “sport.” Munch was an early and eccentric practitioner.

The photographic manuals instructed amateurs to avoid mistakes such as out-of-focus or tilted images, ghosted figures, or shadows laid across the subjects. These were the very photographic elements that Munch repeated, turning the rules of good picture taking upside down.

Munch likely made his own contact prints using an Eastman Kodak-marketed kit outfitted for home use. There are both fingerprints and chemical spills on some of the images. He occasionally double-exposed his photographs or flopped the negative to achieve mirror-image prints, demonstrating a curiosity about the printing process itself. Munch’s exploration of the means and materials of amateur photography extends his groundbreaking strategies in lithography and woodcut.

Kodak Bulls-Eye No. 2

This popular portable model seems to have been the type that Munch had as his first camera. Because the camera used light-proof film cartridges, had a fixed focus lens, and a small window indicating the exposure number, Kodak advertised this model as “Easy Photography,” suitable for the unskilled amateur. An instruction manual from the Eastman Kodak Company was sold with each camera. It included helpful graphics to guide the aspiring amateur and warnings against “absolute failure” to follow instructions. These “failures” were the effects that Munch seemed to favour.

Kodak Vest-Pocket Autographic

This small, lightweight camera could be folded to fit a shirt pocket. Released during the Great War, it was advertised by Kodak to be “as accurate as a watch and as simple to use.” Requiring just a small pressure on the shutter release, the modest size and flexibility of the camera was well suited to some of the intimate images taken by Munch in the 1920s and 1930s.

Kodak No. 3A Series III

Eastman Kodak issued the No. 3A, its first postcard format camera, between 1903 and 1915. The company produced variants such as the Series III until 1943. A bellows that collapsed into a folding bed made the camera portable.

Kodak No. 3 Series III Folding Pocket Camera

Munch took most of the “selfies” at Ekely using this model. First produced from 1900 to 1915, and then with variants issued though the early 1940s, it was a camera that, like the No. 3A, could be operated by direct touch or via a pneumatic release.

Pathé Baby Ciné Camera

This is one of the first cinema cameras intended for home use. The lightweight apparatus had a built-in clockwork which enabled amateurs such as Munch to make hand-held films. Pathé’s projectors made it possible to view the results at home.

Unknown photographer

Portrait of Edvard Munch

Nd

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863-1944)

Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 12 December 1863 – 23 January 1944) was a Norwegian painter. His best known work, The Scream, has become one of the most iconic images of world art.

His childhood was overshadowed by illness, bereavement and the dread of inheriting a mental condition that ran in the family. Studying at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania (today’s Oslo), Munch began to live a bohemian life under the influence of nihilist Hans Jæger, who urged him to paint his own emotional and psychological state (‘soul painting’). From this emerged his distinctive style.

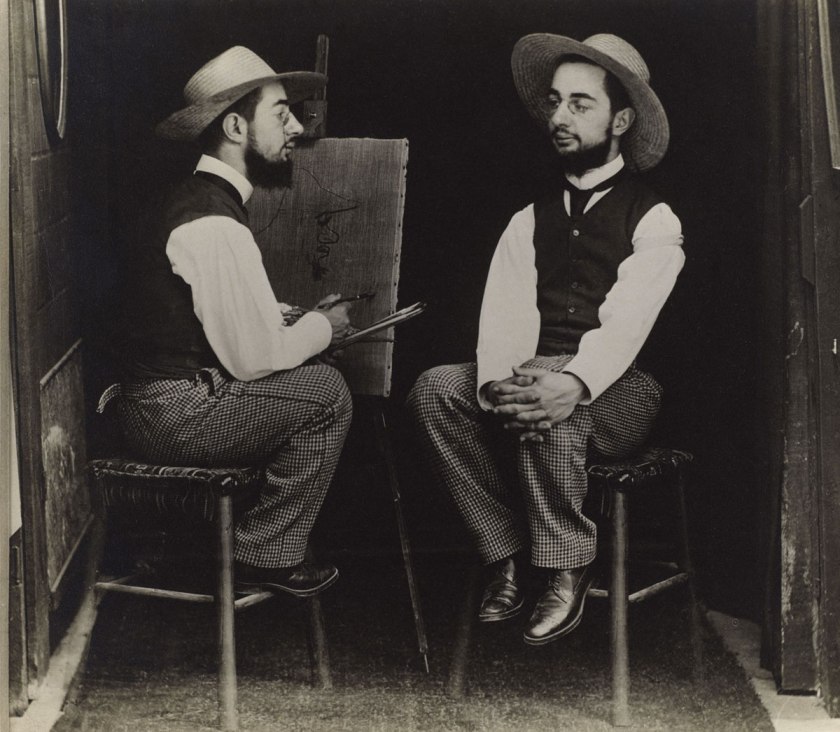

Travel brought new influences and outlets. In Paris, he learned much from Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, especially their use of colour. In Berlin, he met Swedish dramatist August Strindberg, whom he painted, as he embarked on his major canon The Frieze of Life, depicting a series of deeply-felt themes such as love, anxiety, jealousy and betrayal, steeped in atmosphere.

The Scream was conceived in Kristiania. According to Munch, he was out walking at sunset, when he ‘heard the enormous, infinite scream of nature’. The painting’s agonised face is widely identified with the angst of the modern person. Between 1893 and 1910, he made two painted versions and two in pastels, as well as a number of prints. One of the pastels would eventually command the fourth highest nominal price paid for a painting at auction.

As his fame and wealth grew, his emotional state remained insecure. He briefly considered marriage, but could not commit himself. A breakdown in 1908 forced him to give up heavy drinking, and he was cheered by his increasing acceptance by the people of Kristiania and exposure in the city’s museums. His later years were spent working in peace and privacy. Although his works were banned in Nazi Germany, most of them survived World War II, securing him a legacy.

Text from the Wikipedia website

National Nordic Museum

2655 NW Market Street,

Seattle, WA 98107

Phone: 206.789.5707

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Monday

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Street Scene, Double Exposure, Halle]' 1929-1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/street-scene-double-exposure-halle-1929-1930.jpg?w=840&h=644)

![Lucia Moholy (British, born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926 Lucia Moholy (British, born Czechoslovakia, 1894-1989) 'Untitled [Southern View of Newly Completed Bauhaus, Dessau]' 1926](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/gm_06093101.jpg?w=840)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Train Station, Dessau]' 1928-1929](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/gm_326238ex1.jpg?w=840)

![Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928 Lyonel Feininger (American, 1871-1956) 'Untitled [Night View of Trees and Street Lamp, Burgkühnauer Allee, Dessau]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/night-view-of-trees-and-streetlamp-burgkc3bchnauer-allee-dessau-1928.jpg?w=840&h=642)

You must be logged in to post a comment.