Exhibition dates: 17th March – 25th July, 2022

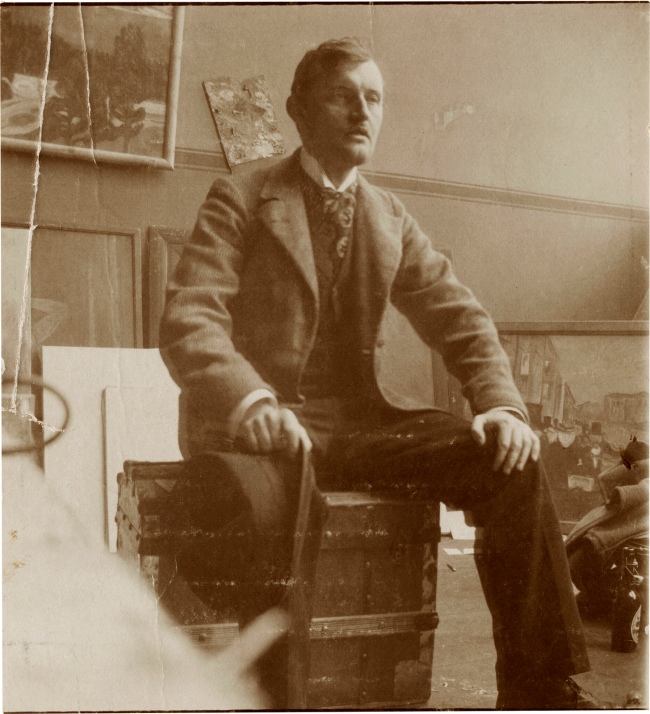

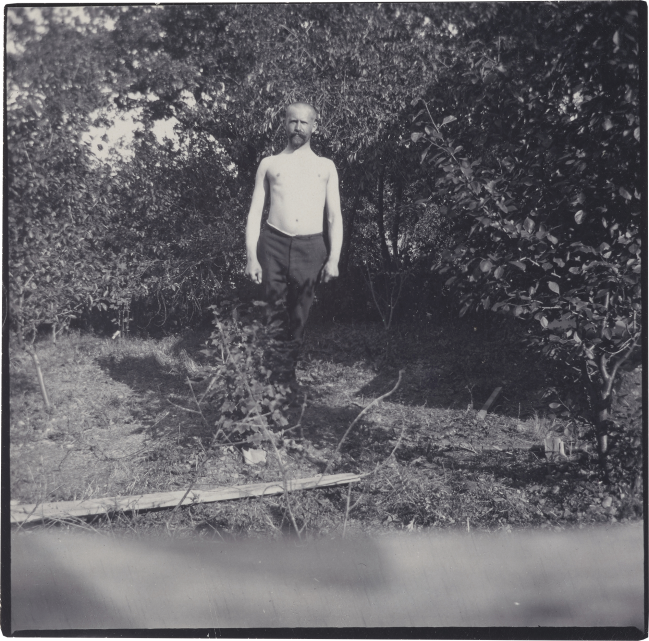

Unidentified artist (American)

Photographer in the Field

1907 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Life in all its variety!

A fascinating look at American real photo postcards and the stories they tell about the US in the early 20th century. They “reveal truths about a country that was growing and changing with the times – and experiencing the social and economic strains that came with those upheavals.”

Sometimes all is not as clear cut as the professional (vernacular) photographers would have us believe when they recorded a moment that would otherwise have been lost to posterity. For example, the Just Government League formed in 1909 – Maryland’s largest organisation advocating for women’s suffrage – was, like many suffrage organisations, predominantly white, Protestant, highly-educated, and financially well-off.

“In the early 20th century, in addition to its large African American population, Baltimore saw an influx of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe who were Jewish and Catholic. Anti-immigrant sentiment was widespread and supported by the eugenic science of the period, to which many of Baltimore’s elite subscribed.”

As with everything in life and photography, nothing is ever black and white. While the photograph captures one moment, one time freeze, the hidden stories embedded in light and language can be excavated with patience and understanding to reveal the many truths of life – that is, the hopes and fears, the discriminations and freedoms of fallible human beings.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museum of Fine Arts Boston for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Unidentified artist (American)

Lumberjacks

1907 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

The Lions, Scio, Oregon

1907

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Telephone Operator

1907 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Through occupational portraits as well as workplace snapshots, real photo postcards served as means of visually representing women’s work outside the home. Snapshot photography’s aesthetic norms may have privileged domesticity, but the same cannot be said for real photo postcards, which illustrate a broad gamut of jobs that women undertook outside of the domestic realm. In this way, real photo postcards both captured women’s participation in public life and, through the cards’ subsequent distribution, visually reinforced it.

Women’s work as shown in real photo postcards includes representations of both exceptional forms of labor and quotidian but under acknowledged ones. Some postcards illustrate the degree to which women were beginning to enter lines of work widely considered too hazardous for their participation. One card, for example, depicts a female lion tamer named Holmes, brandishing a whip as she poses flanked by four lions who sit neatly on pedestals (187). Others show an early female truck driver, Luella Bates (193), and the race car driver Irene Dare (194).

In other fields of work outside the home, women constituted a more expected class of labourers. Postcards depicting telephone exchanges featured women operators, who quickly came to dominate this field of work, owing in part to employers’ belief that they had better telephone manners than men, and in part to the fact that they could be paid considerably less than men.11 On the back of one postcard (188), which depicts an Elmira, New York, roomful of telephone exchange operators clad in shirtwaists and skirts, the sender identifies herself as one of those pictured: “This is where I hold forth,” she writes. Another operator (195), this one pictured solo at the switchboard as she offers a smile to the camera…

Annie Rudd. “Between Private and Public,” in Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss (eds.,). Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation. MFA Publications, 2022, p. 177.

Unidentified artist (American)

Street paving, Wyalusing, Pennsylvania

1907 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

This postcard depicts street layers working outside the Wyalusing Hotel in the town of Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, in 1907. According to the book, real estate development provided good opportunities for photo postcard photographers.

Unidentified artist (American)

Photographer and Sitter with Dog

1907

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Votes for Women

1907 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

In 1903, at the height of the worldwide craze for postcards, the Eastman Kodak Company unveiled a new product: the postcard camera. The device exposed a postcard-sized negative that could print directly onto a blank card, capturing scenes in extraordinary detail. Portable and easy to use, the camera heralded a new way of making postcards. Suddenly almost anyone could make photo postcards, as a hobby or as a business. Other companies quickly followed in Kodak’s wake, and soon photographic postcards joined the billions upon billions of printed cards in circulation before World War II.

Real photo postcards, as such photographic cards are called today, captured aspects of the world that their commercially published cousins never could. Big postcard publishers tended to play it safe, issuing sets that showed celebrated sites from towns across the United States like town halls, historic mills, and post offices. But the photographers who walked the streets or set up temporary studios worked fast and cheap. They could take a risk on a scene that might appeal to only a few, or capture a moment that would otherwise have been lost to posterity. As the Victorian formality of earlier photography fell away, shop interiors, construction sites, train wrecks, and people acting silly all began to appear on real photo postcards, capturing everyday life on film like never before.

Featuring more than 300 works drawn from the MFA’s Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive, this exhibition takes an in-depth look at real photo postcards and the stories they tell about the US in the early 20th century. The cards range from the dramatic and tragic to the inexplicable, funny, and just plain weird. Along the way, they also reveal truths about a country that was growing and changing with the times – and experiencing the social and economic strains that came with those upheavals.

Today, real photo postcards open up the past in ways that can surprise and puzzle. Few of them come with explanations, so over and over again even the most striking images leave only questions: “why?” and sometimes even “what?” “Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation” is a forceful reminder that memory and historical understanding are evanescent.

Text from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston website [Online] Cited 06/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

A man poses in an Uncle Sam costume in Patchogue, Long Island, New York

c. 1908

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

A man poses for a studio photo in an Uncle Sam costume in Patchogue – a village in Long Island, New York – circa 1908. The author writes: ‘Uncle Sam as a symbol for the U.S. was ensured not only by the works of nineteenth-century cartoonists like Thomas Nast and James Montgomery Flagg’s “I Want You” recruiting poster during WWI, but also because of everymen like this one, who emulated Sam’s long white whiskers and stars-and-stripes suit.’

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Group of men outside the post office in the city of Lenox, Iowa

1909 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Streetcar in Columbus, Ohio

around 1909 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

The Strike is On

1910

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Smith Studio (publisher)

U.S President Theodore Roosevelt speaking to a crowd at Freeport, Illinois

1910

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Look up and you’ll see former U.S President Theodore Roosevelt speaking to a crowd at Freeport, Illinois. It’s thought the picture was captured in 1910, the year after his presidency came to an end. The book reads: ‘In 1910, Roosevelt undertook a transcontinental trip that passed through Illinois, stopping in Freeport, Belvedere, and Chicago. The events in Freeport were planned for September 8, 1910’.

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Man in a fur coat

1910

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Featuring a moustachioed man in a fur coat, this postcard is from 1910. ‘Bearing a message in Norwegian, this card, addressed to Ole Flatland, of Canby, Minnesota, is testimony to the large and vibrant Scandinavian community in the upper Midwest,’ the book notes. It says in the absence of contextual information, ‘it is still possible to read images through clues offered in the physical object of the postcard itself, such as a caption on the front or message on the back, the clothes or uniforms that were worn, an object that was held, a person’s expression or body position, or the props and background chosen by the sitter to express a meaningful representation of themselves’

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Flood at H. H. Miller’s Place Sample Room, Galena, Illinois

1911

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Men huddle together outside a bar, HH Miller’s Palace Sample Room, in the small town of Galena in Illinois, during the Valentine’s Day flood of 1911. The book says that the town ‘faced flooding every spring, but the Valentine’s Day flood of 19111 was particularly bad’. It continues: ‘HH Miller, the proprietor of the bar in this postcard, used the card as a New Year’s greeting the following January: “This is my saloon, the water was to the floor. Behind poast [sic] is myself and Berne and the man with white coat is my bartender. Good night.”‘ The tome also notes that these ‘news-style’ photo postcards, documenting ‘fires, floods, explosions, political rallies, strikes, and parades’ were ‘the direct forebear to the citizen journalism of the digital age, captured by ubiquitous smartphones and disseminated through social media’.

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

R. & H. Photo (publisher)

Seen in Chinatown, San Jose, California

1912 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Electricia, the Woman Who Tames Electricity

1912

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Gensmer & Wolfram Grocery Store, Portland, Oregon

1913

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Suffragists

about 1912

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Mary F. Mitchell Feeding Chickens, Wichita, Kansas

about 1912

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Washerwomen

1913

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Long’s Place Lunch Car

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Teacher in the Classroom

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

National Woollen Mills in Wheeling, West Virginia

around 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Men Drinking

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Tourists at Mariposa Grove of Big Trees

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

T. W. Stewart (American, active early 20th century)

Members of the Just Government League of Maryland

1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Established in 1909, the Just Government League became the largest organisation in Maryland advocating for women’s suffrage. Local chapters were founded throughout the state including in Westminster in 1913. By 1915 statewide membership numbered 17,000. The League’s campaign centred on public education to affirm the social benefits of votes for women. After Congress passed the 19th Amendment in 1920, the League turned its focus to women’s civil and political rights, and won the right for women to hold public office in Maryland in 1922.

The Just Government League formed in 1909. Its leaders were Edith Houghton Hooker, a former Hopkins medical student, and her husband Donald Hooker, a Hopkins physician. They were aided by two close friends: Mabel Glover Mall, Edith’s classmate, and Florence Sabin, who completed her MD at Hopkins and became its first female senior faculty member.

Starting in 1910, suffragists began using cross-country hikes to “reach all sorts and conditions of people” outside of urban centres. The women of Maryland’s Just Government League hiked from Baltimore through Garrett County, about seventy miles, holding public meetings along the way.

Edith Hooker admired the direct-action approach of Alice Paul, and helped Paul to split the more radical National Woman’s Party from the moderate NAWSA. Though the Just Government League joined the National Woman’s Party in 1917, it remained more focused on diplomatic than on militant efforts, conducting intensive lobbying in Annapolis and Washington.

Despite their interest in reaching “all sorts” of people, the League, like many suffrage organisations, was predominantly white, Protestant, highly-educated, and financially well-off. In the early 20th century, in addition to its large African American population, Baltimore saw an influx of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe who were Jewish and Catholic. Anti-immigrant sentiment was widespread and supported by the eugenic science of the period, to which many of Baltimore’s elite subscribed.

Anonymous text. “The Just Government League,” on the John Hopkins Library website Nd [Online] Cited 03/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Rose Studio (publisher)

Railroad worker, Portland, Oregon

1911 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Butcher and his Son

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Woman with Flowers

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

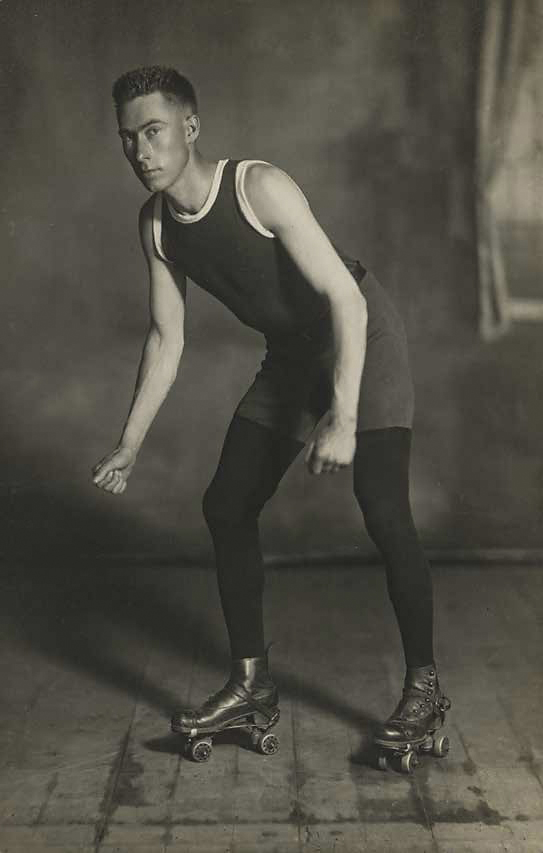

Unidentified artist (American)

Roller skater, Frankfort, Michigan

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Featuring more than 300 works drawn from the Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive, a promised gift to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation takes an in-depth look at the innovative early-20th-century medium that enabled both professional and amateur photographers to capture everyday life in U.S. towns big and small. The photographs on these cards, which range from the dramatic and tragic to the inexplicable and funny, show this moment in history with striking immediacy – revealing truths about a country experiencing rapid industrialisation, mass immigration, technological change, and social and economic uncertainty. The exhibition is on view from March 17 through July 25, 2022 in the Herb Ritts Gallery and Clementine Brown Gallery. It is accompanied by an illustrated volume, Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation, produced by MFA Publications and authored by Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss, the MFA’s Leonard A. Lauder Senior Curator of Visual Culture, with contributions by Eric Moskowitz, Jeff. L Rosenheim, Annie Rudd, Christopher B. Steiner and Anna Tome.

In 1903, at the height of the worldwide craze for postcards, the Eastman Kodak Company unveiled a new product: the postcard camera. The device exposed a postcard-sized negative that could print directly onto a blank card, capturing scenes in extraordinary detail. Portable and easy to use, the camera heralded a new way of making postcards. Suddenly almost anyone could make photo postcards, as a hobby or as a business. Other companies quickly followed in Kodak’s wake, and soon photographic postcards joined the billions upon billions of printed cards in circulation before World War II.

“Real photo postcards bring us back to the exciting early years of photojournalism. The new flexibility and mobility of this medium created citizen photographers who captured life on the ground around them. These cards particularly excite me because we learn from them both the grand historical narrative and the smaller events that made up the daily lives of those who participated in that history,” said Leonard A. Lauder.

Real photo postcards, as such photographic cards are called today, caught aspects of the world that their commercially published cousins never could. Big postcard publishers tended to play it safe, issuing sets that showed celebrated sites from towns across the U.S. like town halls, historic sites and post offices. But the photographers who walked the streets or set up temporary studios worked fast and cheap. They could take a risk on a scene that might appeal to only a few, or record a moment that would otherwise have been lost to posterity. As the Victorian formality of earlier photography fell away, shop interiors, constructions sites, train wrecks and people being silly all began to appear on real photo postcards – capturing everyday life on film like never before.

Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation is organised thematically, with groupings of postcards centred around various events and activities that captivated both professional and amateur photographers at the time – from public festivities and organised sports to people at work in professions ranging from telephone operators to farmers. Many of the cards convey local spot news – fires, floods, explosions, political rallies, strikes and parades – presaging the digital journalism of our own age. The exhibition also features a wide array of postcard portraits, which were inexpensive and affordable to people from most walks of life. Popular categories of postcard portraits included workers posing with the tools of their trade or people posing with studio props or backgrounds, sitting on paper moons or “flying” in a fake airplane or hot-air balloon. Collectively, these portraits offer a rare view of a modern America in the making – one constructed by the people, for themselves.

“The postcards in this exhibition are precious, intricately detailed windows into life a century ago. In exploring the Lauder Archive, we selected and arranged the cards with the hope of conveying a measure of the intimacy and serendipity that might come from walking the streets of a town of that time,” said Weiss.

“Some of those cards reveal their history in great detail, while others are resolutely mute about who made them and why. That is one of the pleasures of working with postcards, and one of the things that makes the Lauder Archive such an inexhaustible mine of stories and mysteries,” added Klich.

Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation is the third exhibition at the MFA drawn from the Leonard A. Lauder Archive, following The Art of Influence: Propaganda Postcards from the Era of World Wars (2018-2019) and The Postcard Age: Selections from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection (2012-2013).

Press release from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Unidentified artist (American)

Circus at Bi-County Fair, Union City, Indiana

1917 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

An image taken at Union City Bi-County Fair in Indiana around 1917. The book says of the photo postcard industry: ‘Just as postcard studios could flourish in the quieter corners of the country, away from the commercial photo studios of the big cities, so could postcard photographers find success close to home. They just needed to make sure that their products were tailored to local tastes: local celebrities, local sports teams, champion livestock and vegetables, the midway at the county fairgrounds, or the local quack–medicine salesmen’.

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Man and Woman in an Automobile

1918

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Thank you to Varun Coutinho for letting me know that the automobile is a 1917 Crow-Elkhart 20Hp Model 33 Cloverleaf De Luxe Roadster

Unidentified artist (American)

Swimmers at Saltair, Utah Levene

1918

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

The Northern Photo Company (publisher)

Advanced Room, Indian School, Wittenberg Wisconsin

1919

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Harbaugh Photo (publisher)

Paper Moon Portrait of a Barber

about 1914

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Paper Moon Portrait of a Young Woman

1917 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Amish market in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

1925

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Unidentified artist (American)

Assembly line, Ford Motor Company factory, Dearborn, Michigan

mid-1920s

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

An assembly line of the Ford Motor Company factory photographed in the mid-1920s in Dearborn, Michigan. The authors write: ‘The photographs on these cards capture the United States in the early twentieth century with a striking immediacy. It was a time of rapid industrialisation, mass immigration, technological change, and social uncertainty – in other words, a time much like our own’.

Unidentified artist (American)

Alma Mae Bradley

1926 or later

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

Sometime in the early 1930s, a young Black woman posed for a portrait in what appears to be a makeshift photo studio, set up perhaps on the grounds of her high school campus (144). Affixed to the wall behind her is a cloth banner, its creases still visible from where it had been neatly pressed prior to being unfolded as a backdrop. Although the felt letters on the banner are mostly cut off from the image’s frame, there are enough letters visible to make out that the photograph was taken at Downingtown Industrial and Agricultural School, a vocational high school established in 1905 to educate Black children in and around Chester County, Pennsylvania. The young woman is dressed in the uniform of her school team, and she is wearing a pair of Ball-Band high-top canvas rubber-soled sneakers, the latest innovation in competitive athletic footwear. She stands with one foot in front of the other, her left knee slightly bent, and she appears ready to throw a basketball while looking off somewhere into the distance. Although the photograph represents a unique likeness or portrait of this individual, the image closely follows the stylistic conventions of this period – photographing athletes in the artificial surroundings of a photo studio while presenting them as if caught in a frozen moment of action during a game or sporting event. On the back of the postcard is written: “When you look at this, think of me. Keep this to remember me by. Love Alma Mae Bradley.” Beyond the small clues presented in the brief handwritten text and in the image, virtually nothing else is known about this young woman – who she was, whom she was writing to, and how exactly she would want to be remembered.1 Like so many other portraits on photo postcards produced in the early twentieth century, this one has been separated from its original context and from its intended recipient. What had started as a personal memento from a life being lived, is now a public document detached from individual experience and meaning.

Christopher B. Steiner. “When You Look at This, Think of Me,” in Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss (eds.,). Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation. MFA Publications, 2022, p. 138.

Mitchell (American, photographer)

Birger and his gang

October 1926

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

This incredible photograph was taken in Harrisburg, Illinois, by local resident and photographer Alvis Michael Mitchell and shows notorious gangster Charlie Birger and his gun-toting gang. Birger, reveals the book, was ‘as notorious as any gangster anywhere from 1926 to 1928’, with one newspaper story at the time describing Al Capone as ‘the Charlie Birger of Cook County’. Birger’s gang, we learn in the tome, ‘controlled bootlegging and “adult entertainment” across Southern Illinois’, with Birger eventually convicted of orchestrating the murder of a small-town mayor and becoming the last man publicly hanged in Illinois on April 19, 1928. He can be seen in the picture sitting sidesaddle on the porch rail at back-right in a bulletproof vest, the book reveals. Adding further insight, it says: ‘The inscription on [this] card, “Birger and His Gang”, vaults the viewer from quietly eyeing a band of outlaws to considering what photographer Mitchell might have felt as he steadied his camera before all that brandished firepower… though Mitchell suggested to a reporter years later that he had arranged the photo, family lore has it the other way: Birger’s gang enlisted the reluctant photographer, knocking on the door and spooking his wife.’ Despite the 1927 notation on the card, the book’s authors say the date ‘can be narrowed down to within a few days in October 1926, based on the movements, arrests, and deaths of the pictured gang members’.

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Unidentified artist (American)

Two elegantly dressed women at the Grand Canyon

January 14, 1929

Gelatin silver print on card stock

Leonard A. Lauder Postcard Archive

This photo, taken on January 14, 1929, shows two elegantly dressed women at the Grand Canyon. The book says of the shot: ‘The women stand before what is today a hackneyed tourist view… but what was then remarkable, a novelty. Their heeled shoes and clutches indicate that they did not rough it to get there, but were neatly dropped, likely by a driver, in a predetermined location designed to ensure that they could procure a photograph that would communicate, in effect, that they had “been there, done that”‘.

Sarah Holt and Sadie Whitelocks. “Step back in time to yesteryear America: Fascinating new book of vintage photo postcards reveals life in the U.S during the early 20th century, from gun gangs to Grand Canyon visits,” on the Mailonline website 14 April 2022 [Online] Cited 02/05/2022

Real Photo Postcards: Pictures from a Changing Nation book cover. The cover picture shows tourists at the Wawona Tree in California’s Yosemite National Park in 1908.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Avenue of the Arts

465 Huntington Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts

Opening hours:

Monday and Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Wednesday – Friday 10am – 10pm

Saturday and Sunday 10am – 5pm

![John F. Collins (American, 1888-1990, active 1904-1974) '[Kodak Ektra Camera]' c. 1930 John F. Collins (American, 1888-1990, active 1904-1974) '[Kodak Ektra Camera]' c. 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/collins-camera.jpg?w=840)

![Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Self-portrait preparing a Collodion plate]' 1856-1859 Capt. Horatio Ross (British, 1801-1886) '[Self-portrait preparing a Collodion plate]' 1856-1859](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ifthecamera2.jpg?w=650&h=802)

![George Watson (American, 1892-1977) '[Camera on 12-foot Tripod]' 1920s George Watson (American, 1892-1977) '[Camera on 12-foot Tripod]' 1920s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ifthecamera7.jpg?w=650&h=811)

![Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) '[Self-Portrait with Camera]' 1932 Man Ray (American, 1890-1976) '[Self-Portrait with Camera]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ifthecamera3.jpg?w=650&h=834)

![Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989) '[Self-Portrait]' 1932 Alma Lavenson (American, 1897-1989) '[Self-Portrait]' 1932](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/alma-lavenson.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Portrait of Dorothea Lange]' 1937 Unknown photographer (American) '[Portrait of Dorothea Lange]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/dorothea-lange.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.