Exhibition dates: 11th December 2015 – 24th April 2016

In collaboration with The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, USA

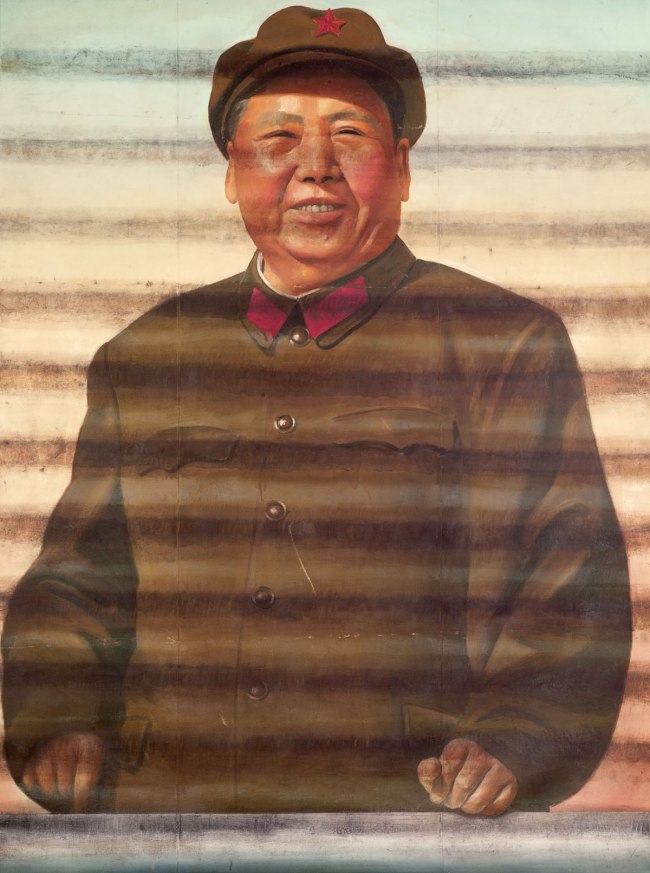

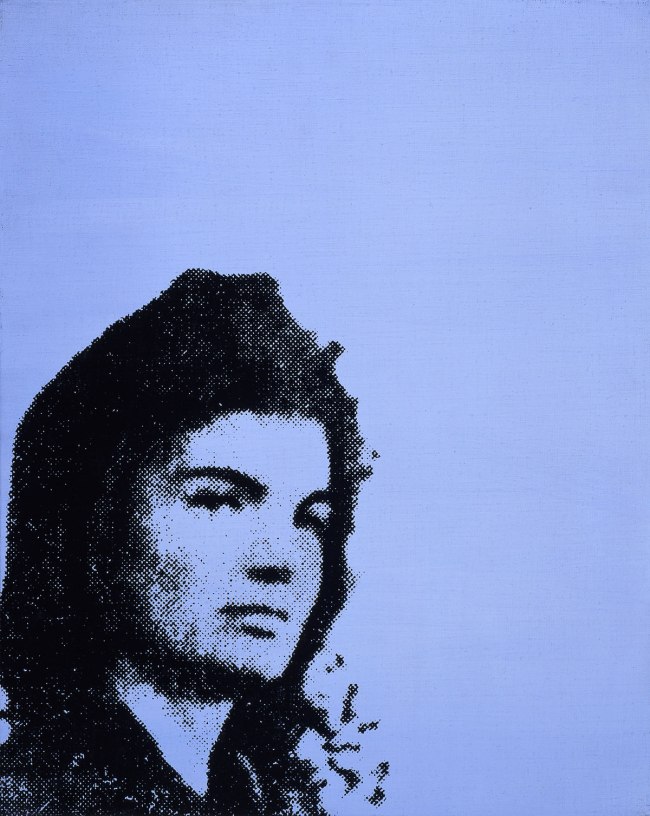

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Mao (Facing Forward)

1986

Oil on canvas

233.6 x 193.0cm

Private collection

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

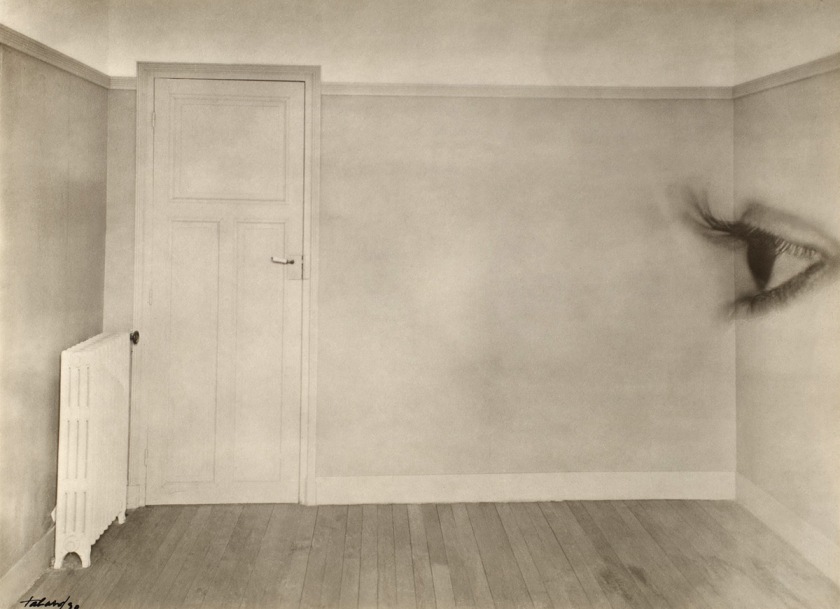

Time lapse

This mega-exhibition has been a popular success for the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, with over 300,000 visitors during its run. But does that make it an interesting, or even memorable, exhibition? Personally, I think this is an exhibition based on a curatorial concept, an interesting concept, that does not then lead to a memorable exhibition. I will explain why.

The idea behind the exhibition, to compare and contrast the work of Andy Warhol (one of the most influential artists of the twentieth century) and the work of Ai Weiewei (that denizen and superstar of contemporary art and free speech, in China and around the world) is sound but in reality, on actual viewing, the relationship between the ideas of both artists seems rather forced.

While the synergy of ideas between both artists is present – “a vocabulary which celebrates freedom of speech and, at the same time, the wisdom of pop culture” – evidenced through the symbology of popular culture and the specificity and uniqueness of the original, the installation of the work does neither of the artist’s work justice.

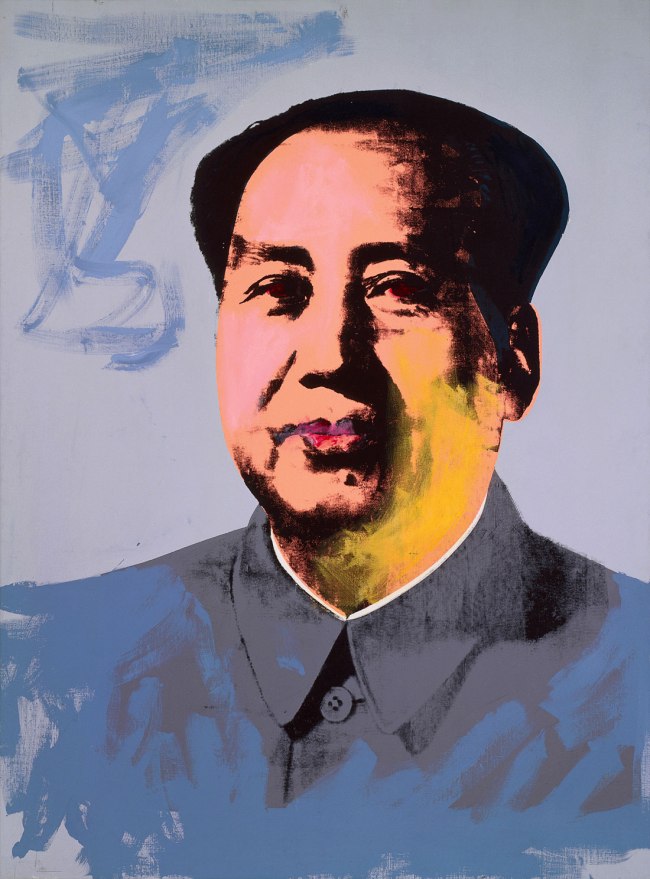

In this game of comparisons (where Andy Warhol’s photographs of New York sit opposite those of Ai Weiwei’s, where Andy Warhol’s portraits of Chairman Mao sit diagonally opposite Ai Weiwei’s) neither artist’s work can be contemplated as a whole… and it is Warhol’s work that comes out a poor second best in this artistic exchange.

Why?

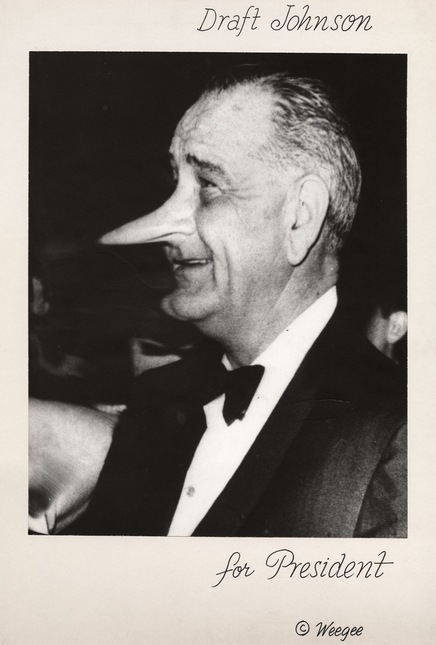

Mainly because both artist’s are talking about completely different things from completely different eras and it is Ai who dominates the conversation. As Monica Tan observes in an article on the Guardian website, “In their art, Ai aggressively engages with politics and current affairs… while Warhol was forever occupied with consumerism, pop culture iconography and celebrity.”1

With regard to the work of Ai Weiwei there is the key word, aggressively. His brazen installations simply overwhelm the sophistication of the work of Andy Warhol, and this should never have happened, should never have been allowed to happen. The exhibition does not do Warhol’s work justice.

Ai Weiwei comments, “We’re dealing with different societies, Andy Warhol and I. We are involved with very different social and political circumstances. But we’re both trying to face out reality honestly and to give a better illustration of our time.”2

While the last sentence is true, facing out reality honestly does not mean that both mens work can be understood or compared in the same breath, which is what happens in this exhibition. For each artist’s work I felt there was no space to breathe in the whole eight galleries. The visitor needs at least three hours, and a couple of visits, to get through all of the work and at the end of it all you feel is rather exhausted and only a little enlightened.

After the forced curatorial concept of the whole exhibition, this is my second major criticism of the show: the unnecessary “noise” of the installation. Everything and the art kitchen sink (preferably teamed with an ancient Chinese sink with ceramic flowers growing out of it) has been thrown at the installation of the exhibition, not necessarily to its benefit.

Susan Sontag despairs of the “ambience of distraction” that pervades contemporary museums – less room to contemplate, more rooms for noise.

The NGV seems particularly adept at this distraction and this exhibition is just another example of the phenomenon. Room after room is filled to the brim with artefacts which are then placed on more noise – busy, repetitious wallpaper!

Andy Warhol’s silkscreen portraits of Mao (1972) are hung on his Mao Wallpaper (1974, reprint 2015), on the exterior of Ai Weiwei’s Letgo room (2015) meaning that you can’t really “read” the colours of the silkscreens properly as they are subsumed amongst this mass of wallpaper noise. A similar thing happens with Warhol’s Electric Chairs (1971) silkscreens and his Electric Chair (1967) painting which are hung on Warhol’s Washington Monument Wallpaper (1974, reprint 2015). This means that the luminosity of the colours of the silkscreens and painting completely loose their impact if you were viewing the works against a plain wall. They just blend into the gallery wall.

It’s as though the curators at the NGV are frightened of empty wall space, both in the number of objects in a room and the lack of negative space (plain coloured walls) behind the art works. And this is not a singular occurrence of this phenomenon at the NGV… the exhibition David McDiarmid: When This You See Remember Me featured this installation technique while the exhibition Masterpieces from the Hermitage: The Legacy of Catherine the Great was nearly ruined by garish wall colourings and patterned floors. Less is more.

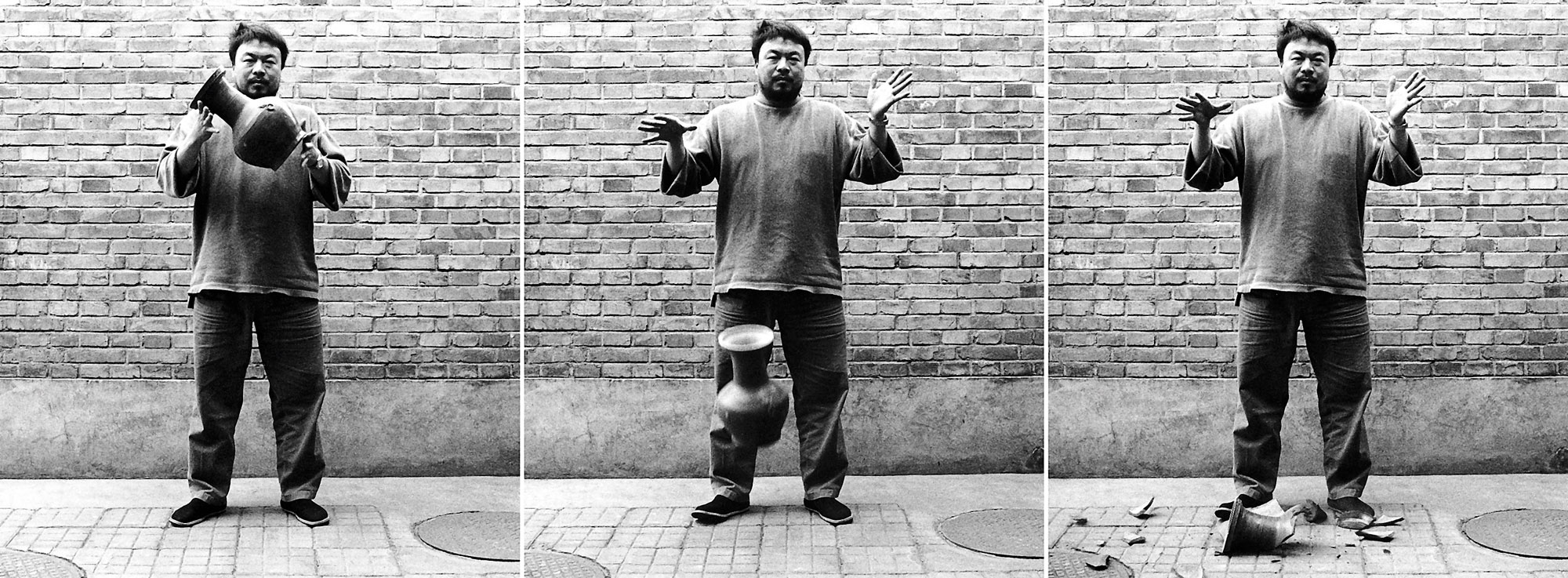

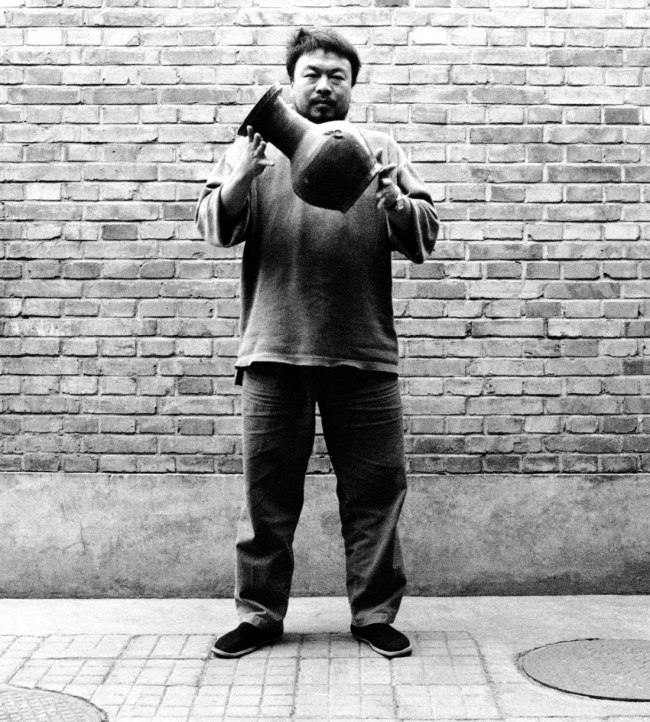

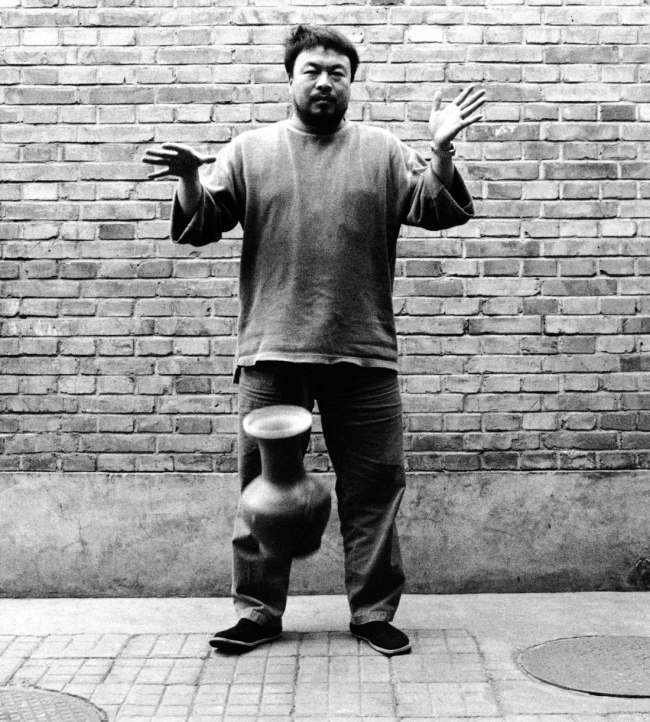

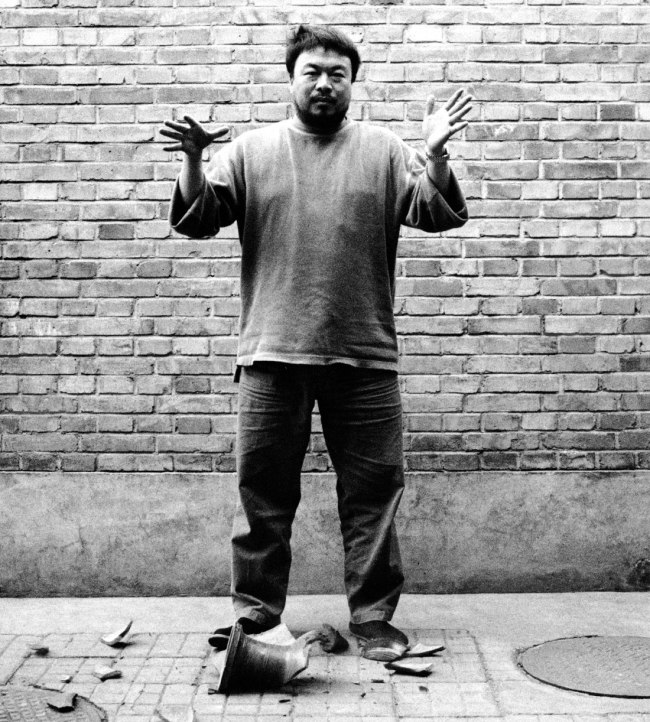

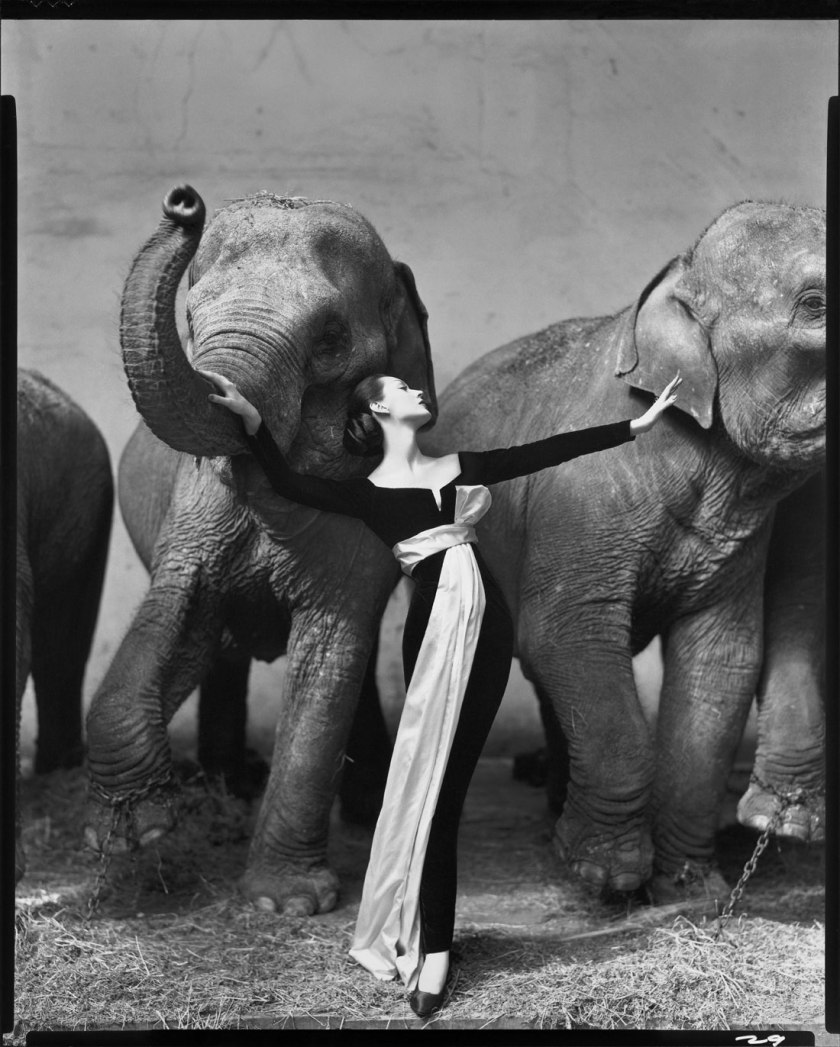

Speaking of which, some of superstar of the contemporary art world Ai Weiwei’s work was, dare I say it, woeful. When he hits the mark, such as in bodies of work like the photographic series Study of Perspective (1995-2011, below), his incisive commentary on freedom and surveillance With Flowers (2013-2015) or his installation of S.A.C.R.E.D. Maquettes (2011), which depicts scenes from the detention cell where he was held without charge by the Chinese government for eighty-one days – he is masterful as an artist, in complete control of his visual and symbolic language.

But then you have pieces of work such as the dire Letgo (2015) (focusing on Australian activists, advocates and champions of human rights and freedom of speech) made of pseudo-LEGO which is just a hideous and ugly art work that has very few redeeming features. There also seems no logical reason to remake the famous photographic triptych Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995, below) in children’s building bricks. To no particularly good effect, why is this statement, this re-imagining being made?

Similarly, when Ai remakes a pair of handcuffs in jade and wood, Handcuffs (2015), other than the historic qualities of the materials in relation to the history of China and issues of freedom of speech, where does the work actually take you? Not very far. Noise, noise and more noise, just a symptom and comment on our social media society.

The third major criticism of this exhibition and the most crucial to its failure to be a memorable exhibition: is its lack of TIME.

Lumping both Warhol and Ai Weiwei side by side, cheek by jowl, gives neither artist’s work the time to breathe and the viewer no time to contemplate, to IMAGINE, the relationship between the two artists. Two artist’s from different eras separated by time. Here, time (and space) is conflated as though the intervening period between them never existed. My idea was this: first, have the first four gallery rooms full of Warhol’s work so that you could understand the ambience of his colour and subtlety, yes subtlety, of his visual language. Then a dark passageway before emerging into four galleries of Ai Weiwei’s work. In this way, you could have understood each artist’s work independently of each other in a holistic way, and then made you own linkages between the two artist’s works… instead of, oh look, here’s Warhol’s photographs of NY and, oh, there’s Ai Weiwei’s photographs of NY!

This simplistic, popularist, comparative curatorial strategy never allows these major artists work room to breathe or the time and space to exist in the sphere and realm of each other. Warhol’s work is denuded by Ai’s aggressive, contemporary take on politics and freedom of speech. Warhol did not deserve that. A sense of TIME and SPACE is what this exhibition needed in its installation in order for the viewer to be able to fully contemplate and IMAGINE the relationship between the two artists. To trust the intelligence of the viewer to make the connections, not treat them as some number walking through the door. Less noise and more imagination.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,313

Footnotes

1/ Monica Tan. “Ai Weiwei interview: ‘In human history, there’s never been a moment like this’,” on The Guardian website, 10th December 2015 [Online] Cited 23/03/2016.

2/ “Max Delany in conversation with Ai Weiwei,” in Gallery magazine, January-February 2016. National Gallery of Victoria, 2016, p. 29.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

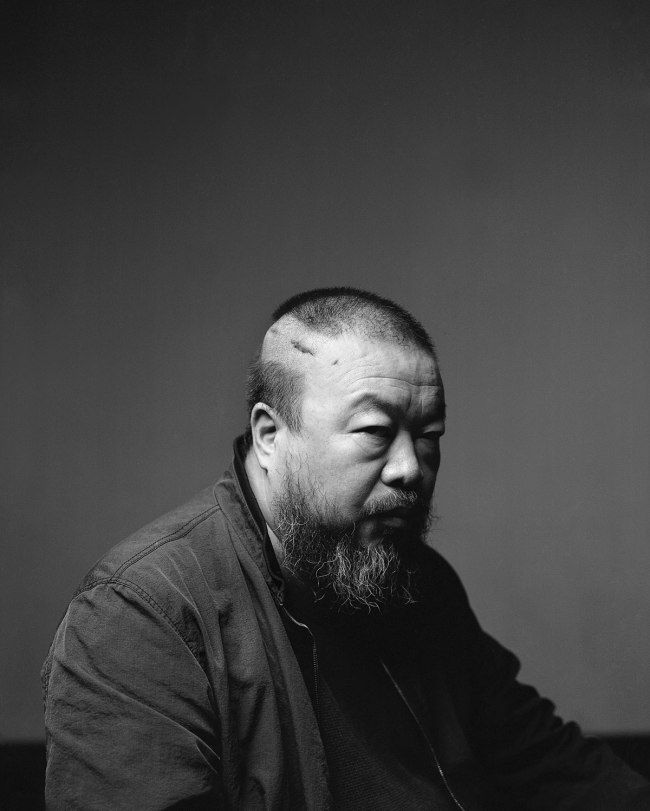

Gao Yuan

Ai Weiwei

2012

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

This major international exhibition features two of the most significant artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei.

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, developed by the NGV and The Andy Warhol Museum, with the participation of Ai Weiwei, explores the significant influence of these two exemplary artists on modern art and contemporary life, focusing on the parallels, intersections and points of difference between the two artists’ practices. Surveying the scope of both artists’ careers, the exhibition at the NGV presents more than 300 works, including major new commissions, immersive installations and a wide representation of paintings, sculpture, film, photography, publishing and social media.

Presenting the work of both artists, the exhibition explores modern and contemporary art, life and cultural politics through the activities of two exemplary figures – one of whom represents twentieth century modernity and the ‘American century’; and the other contemporary life in the twenty-first century and what has been heralded as the ‘Chinese century’ to come.

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei premieres a suite of major new commissions from Ai Weiwei, including an installation from the Forever Bicycles series, composed from almost 1500 bicycles; a major five-metre-tall work from Ai’s Chandelier series of crystal and light; Blossom 2015, a spectacular installation in the form of a large bed of thousands of delicate, intricately designed white porcelain flowers; and a room-scale installation featuring portraits of Australian advocates for human rights and freedom of speech and information.

Text from the National Gallery of Victoria website

“Marilyn Monroe, the electric chair, Mickey Mouse, Mao Zedong, wallpaper, disasters, comic books, the Empire State Building, dollar bills, Coca-Cola, Einstein – no one knows how many works he left behind; they are varied and miscellaneous, touching upon almost all the important personalities and things of his time, and encompassing almost any possible means of expression: design, painting, sculpture, installation, recordings, photography, video, texts, advertising … Andy Warhol’s creations have rebelled against traditional, commercial, consumerist, plebeian, capitalist and globalised art… no matter when or where he was he was always taking photographs and recording; he was several decades ahead of his time. …

Andy Warhol was a self-created product, and the transmission of that product was a characteristic of his identity, including all of his activities and his life itself. He was a complicated composite of interests and actions; he practiced the passions, desires, ambitions and imaginations of his era. He shaped a broad perception of the world, an experimental world, a popular world, and a non-traditional, anti-elitist world. This is the true significance of Andy Warhol that people aren’t willing to accept, and the reason that he is still not recognised as a true artist by everyone.”

Ai Weiwei. “Ai Weiwei: A tribute to Andy Warhol,” in Gallery magazine, January-February 2016. National Gallery of Victoria, 2016, pp. 31-32.

“Warhol is someone I think of as a unique treasure from the past century, which I call the ‘American Century’. His work has all the qualities of that time and reflects all its mythologies. Warhol’s value has always been underrated. He was many evades ahead of his time. I think, even today, he is still one of the most important figures in contemporary art.”

Ai Weiwei quoted in “Max Delany in conversation with Ai Weiwei,” in Gallery magazine, January-February 2016. National Gallery of Victoria, 2016, p. 27.

Ai Weiwei in conversation with Virginia Trioli

Icons and iconoclasm

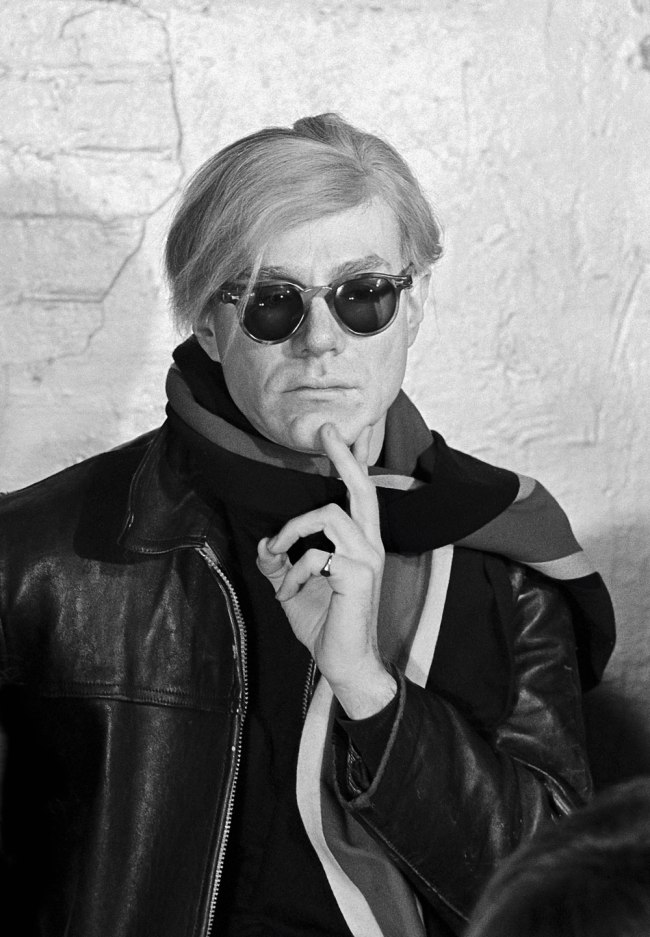

Andy Warhol is among the most influential artists of the twentieth century. He was a leading figure in the development of Pop Art, and his influence extended to the worlds of film, music, television and popular culture. Warhol created some of the most defining iconography of the late twentieth century through his exploration of consumer society, fame and celebrity, media and advertising, politics and capital.

Ai Weiwei is a Chinese artist, social activist and one of today’s most renowned contemporary artists. His provocative work encompasses diverse fields, including visual art, architecture, curatorial practice, cultural criticism, social media and activism. Ai’s practice addresses some of the most critical global issues of the early twenty-first century, such as the relationship between tradition and modernity, the role of the individual and the state, questions of human rights and the value of freedom of expression.

In this gallery we are introduced to the artists through their engagement with self-portraiture and self-representation, and through some of their most iconic, performative and iconoclastic works. These works not only attest to both artists’ transformation of aesthetic value through artistic innovation and experimentation, but also reference their shared interest in cultural heritage and vernacular expression in the United States and China, respectively.

Text from exhibition wall panel

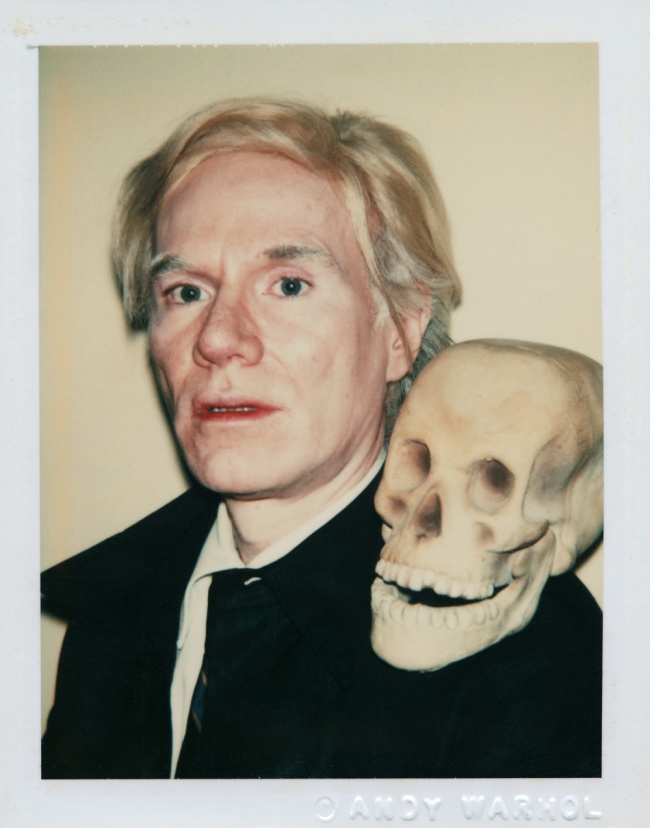

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Mao

1972

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

208.3 x 154.9cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution Dia Center for the Arts

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

The source image for Warhol’s numerous portraits of Mao Zedong is the frontispiece to the Chairman’s famous Little Red Book of quotations. Mao’s image was in the media spotlight in 1972, the year US President Richard Nixon travelled to China, and his official portrait could be seen on the walls of homes, businesses and government buildings throughout the country. It was also extremely popular among literary and intellectual circles in the West. Warhol’s repetition of the image as pop-cultural icon underlines the cult of celebrity surrounding Mao, and the ways in which the proliferation of images in media and advertising promotes consumer desire and identification.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Cultural revolutions

Andy Warhol’s Mao paintings, based on a photograph of Mao Zedong taken from his famous Little Red Book of quotations (1964-1976), adopt the subject matter of totalitarian propaganda to create pop portraits of the communist leader. Created in 1972, the year US President Richard Nixon travelled to China – signalling a thawing of relations between the two nations after almost three decades of intense political rivalry – Warhol’s paintings address the cult of personality surrounding Mao. Warhol’s Mao paintings, prints and wallpaper highlight not only the status and influence of the Chinese leader at the height of the Cold War, but also the instrumental role the repetition of images played in establishing his fame.

In the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, avant-garde artists in China embraced a wide range of aesthetic positions, including Pop and postmodern critiques of Socialist Realism, sometimes known as cynical realism, to recalibrate historical Chinese images and propaganda. These deadpan critiques of official state imagery are apparent in Ai Weiwei’s large-scale, hand-painted images of Mao produced in the mid 1980s in New York. Ai’s representations of Mao subject the communist leader to various distortions familiar from television signals and screens and painterly gestural abstraction.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Self-Portrait with Skull

1977

Polaroid™ Polacolor Type 108

10.8 x 8.6cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Gao Yuan

Ai Weiwei

2009

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei studio

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Illuminations

2014

Digital lambda print

126 x 168cm

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

This self-portrait was shot by Ai in an elevator while being taken into police custody in 2009. On the night before the trial of a fellow political activist in Chengdu Ai was preparing for, Chinese police officers forced their way into his hotel room around 3 am and arrested him. This candid, documentary-style snap plays on the tradition of the ‘selfie’ in contemporary social media, transforming the form into a political tool. Illumination is a defiant expression of personal autonomy.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Gun

1981-1982

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

177.8 x 228.6 x 3.2cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Images of death and disaster were a recurrent theme for Warhol from the early 1960s onwards – a preoccupation fatefully realised at a personal level in 1968 when he was shot and seriously injured by the radical feminist writer Valerie Solanas. The gun in the painting is similar to the .22 pistol that Solanas used. While it may be read as autobiographical, Warhol’s Gun series can also be considered in the tradition of still life. It reflects on the ubiquity of violence in popular culture and the media, as well as the role of guns in US culture.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Jackie

1964

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

50.8 x 40.6 x 1.9cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Cat in Front of Church

c. 1959

Ink, graphite, and Dr. Martin’s Aniline dye on Strathmore Seconds paper

57.5 x 45.1cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

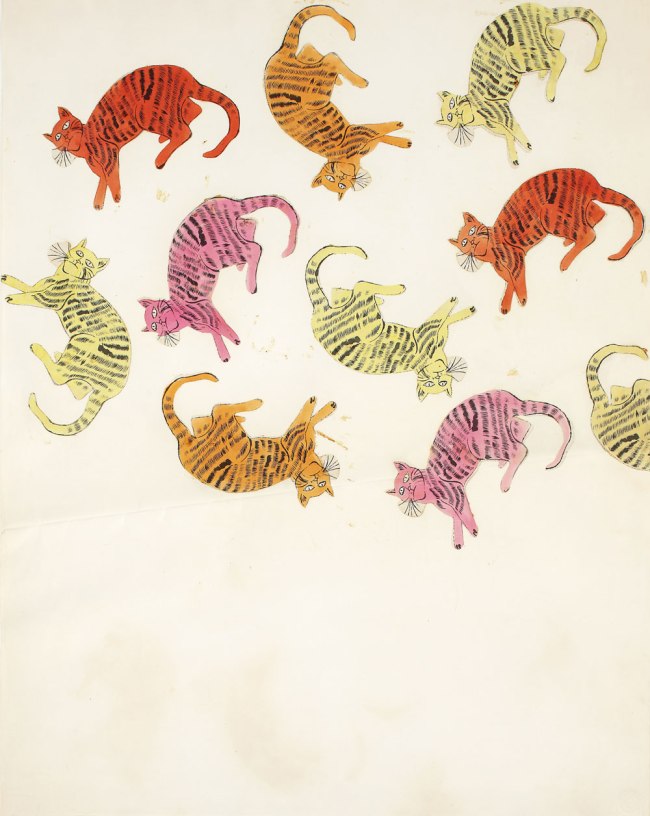

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Cat Collage (from 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy)

c. 1954

Ink, Dr. Martin’s Aniline dye, and collage on Strathmore paper

73.7 x 58.4cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

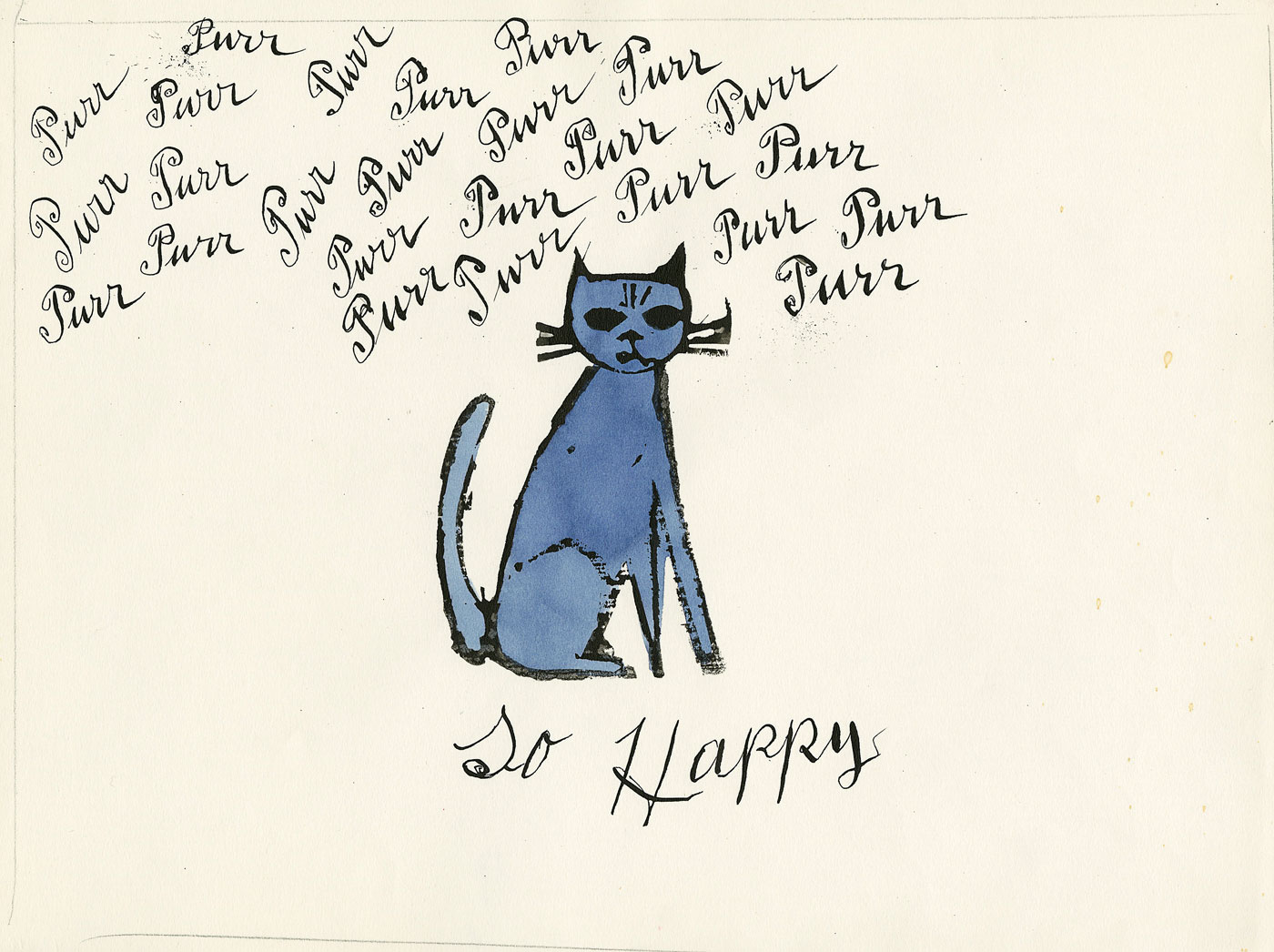

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Julia Warhola (American, 1892-1972)

So Happy

1950s

Ink, graphite and aniline dye on paper

24.8 x 31.8cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Early drawings

Andy Warhol’s and Ai Weiwei’s practices, like those of many artists, began with a strong interest in drawing. Following art school at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, Pittsburgh, Warhol relocated to New York and worked as a commercial illustrator throughout the 1950s. His professional success was largely due to a simple yet sophisticated style and his ability to create art quickly using the ‘blotted line’ technique – a signature style which combined drawing with very basic printmaking. One of his best known advertising campaigns in the 1950s was for I. Miller Shoes; other clients included book publishers, record companies and fashion magazines. These early drawings are of a more personal nature and reveal Warhol’s interest in themes explored in later paintings, screen-prints and films, such as beauty, celebrity, commodities and urban life.

Ai’s early drawings display the poetic sensibility of a young artist whose childhood was largely spent in western Xinjiang Province, a remote desert area where his father, the eminent poet and intellectual Ai Qing had been sent for manual labour and ‘re-education’ during the Cultural Revolution. Made in the late 1970s, when Ai became involved in burgeoning democracy movements and the avant-garde artists’ collective the Stars group, the drawings – while classical in appearance – are marked by an individualistic world view and artistic experimentation at odds with the officially sanctioned aesthetics of Socialist Realism.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

You’re In

1967

Spray paint on glass bottles in printed wooden crate

Crate: 20.3 x 43.2 x 30.5cm

Bottles (each): 20.3 x 5.7cm

Diameter: 18.7cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Neolithic Pottery with Coca Cola Logo

2007

Paint, Neolithic ceramic urn

27.94 x 24.89cm

Private collection

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

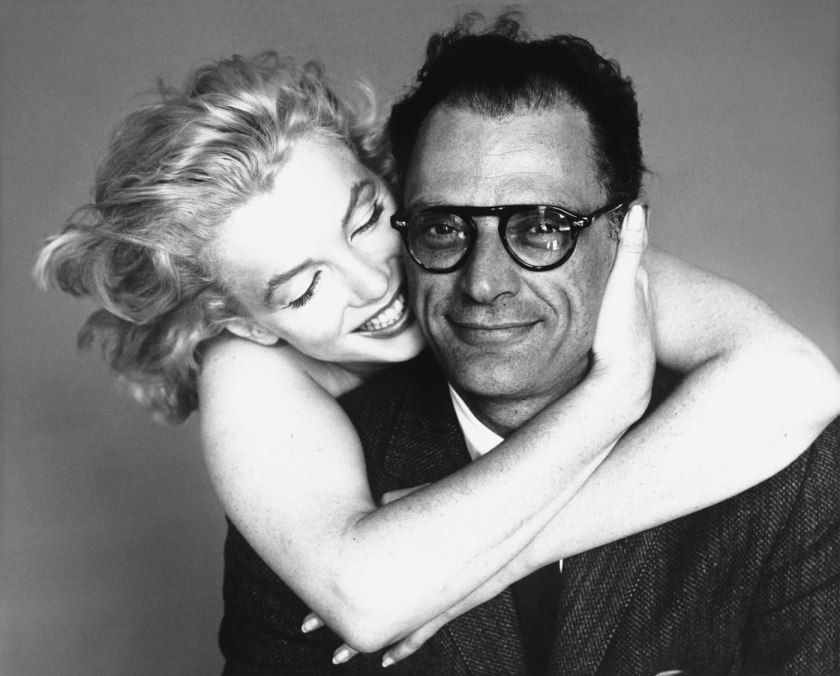

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Three Marilyns

1962

Acrylic, silkscreen ink, and graphite on linen

35.6 x 85.1cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Warhol’s paintings of Marilyn Monroe were made from a production still from the 1953 film Niagara, and are among his first photo-silkscreen works. Warhol recalls that he began using this process in August 1962: ‘When Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make silkscreens of her beautiful face – the first Marilyns’. The repetition of Monroe’s image can be read as a memorial for the deceased American icon as well as a reflection of the media’s insatiable appetite for celebrity and tragedy.

Text from exhibition wall panel

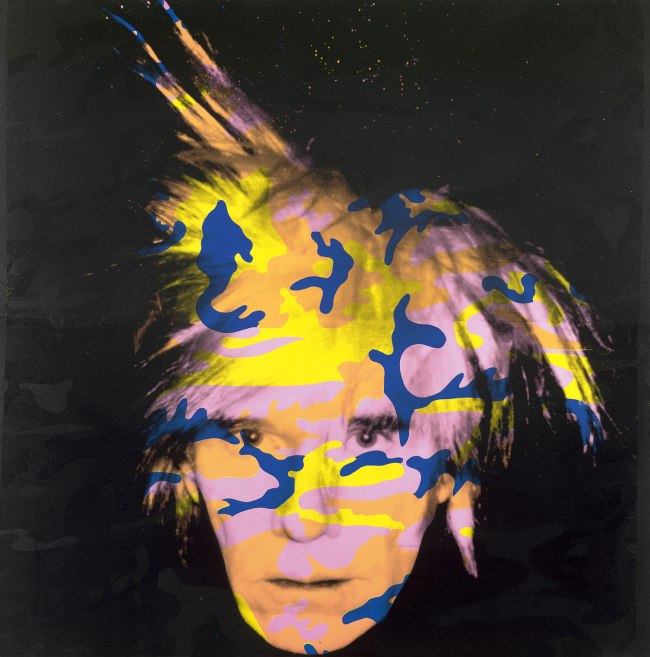

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Self-Portrait No. 9

1986

Synthetic polymer paint and screenprint on canvas

203.5 x 203.7cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of the National Gallery Women’s Association, Governor, 1987

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

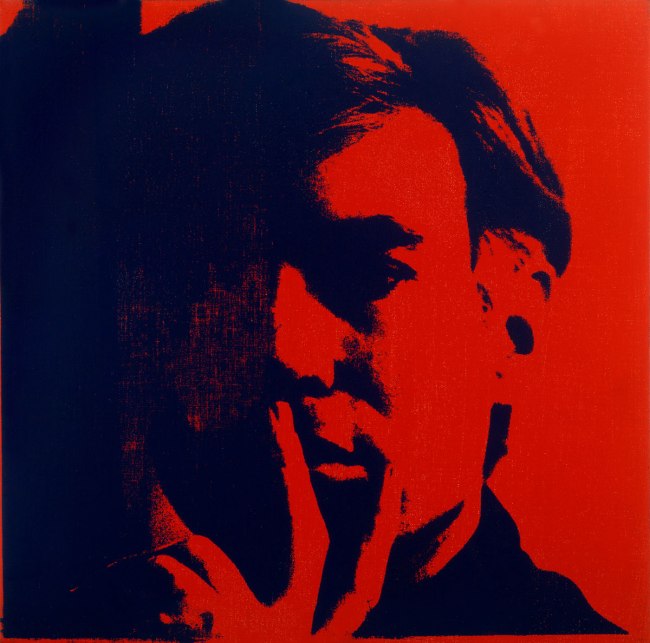

It is perhaps surprising, in view of his self-consciousness and fondness for the anonymity of silkscreen printing, that Warhol produced many self-portraits over a twenty-year period. In Self-Portrait No. 9 his gaunt, disembodied image floats against a starry black background, partially concealed by a fluorescent camouflage pattern – an eloquent reflection on the nature of fame and privacy in an age of mass media. Produced only months before Warhol’s death from surgical complications, this haunting self-portrait is sometimes interpreted as a postmodern death mask.

Nine months before his untimely death due to complications after gall bladder surgery, Warhol undertook a large series of iconic self-portrait paintings. Many viewers and critics alike regard these gaunt staring faces as memento mori, or reminders of human mortality. Each work centres on a levitating head surrounded by a halo of spiky hair. Monumental in scale, the works have a melancholic, haunting quality created in part by the use of dark tones and a dense black ground, and in part by variations across the series in the ghostlike negative photographic reproduction.

Text from exhibition wall panels

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Silver Liz [Ferus Type]

1963

Silkscreen ink, acrylic, and spray paint on linen

101.6 x 101.6cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

The first series of Warhol paintings on a silver background – the Electric Chairs and Tunafish Disasters of 1963 – suggest that the artist’s silver paintings are related to death. Even in the Liz paintings, which appear to highlight Elizabeth Taylor’s Hollywood career, there is an underlying theme of mortality. Warhol created this portrait when Taylor was at the height of stardom, but also very ill with pneumonia. He later recalled: ‘I started those a long time ago, when she was so sick and everyone said she was going to die. Now I’m doing them all over, putting bright colours on her lips and eyes’.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Fabis Statue of Liberty

1986

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

127.0 x 177.8cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Warhol returned to the Statue of Liberty image many times during his career, repeatedly adapting the iconic form from different stylistic angles. In this work, Warhol focused on Lady Liberty’s face to produce a heroic celebrity portrait. The painting was created in 1986 – 100 years after the statue arrived in New York as a gift from France. The Fabis logo in the painting’s left corner is that of a French cookie company. Warhol played with all sorts of brands and logos in large-scale paintings of this period, often juxtaposing brands on top of images in contradictory and humorous ways.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Sydney Opera House, Sydney, Australia

2006

From the Study of Perspective series 1995-2011

Type C photograph

Various dimensions

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

The Study of Perspective series of photographs depicts Ai defiantly raising his middle finger to architectural monuments symbolic of state and cultural power. Measuring the distance between the artist and his subject, the composition of these works invokes the spatial relationship between the individual and the state while also echoing the unforgettable image of a lone demonstrator blocking the path of a military tank at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Tiananmen Square, Beijing, China

1995

From the Study of Perspective series 1995-2011

Type C photograph

Various dimensions

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

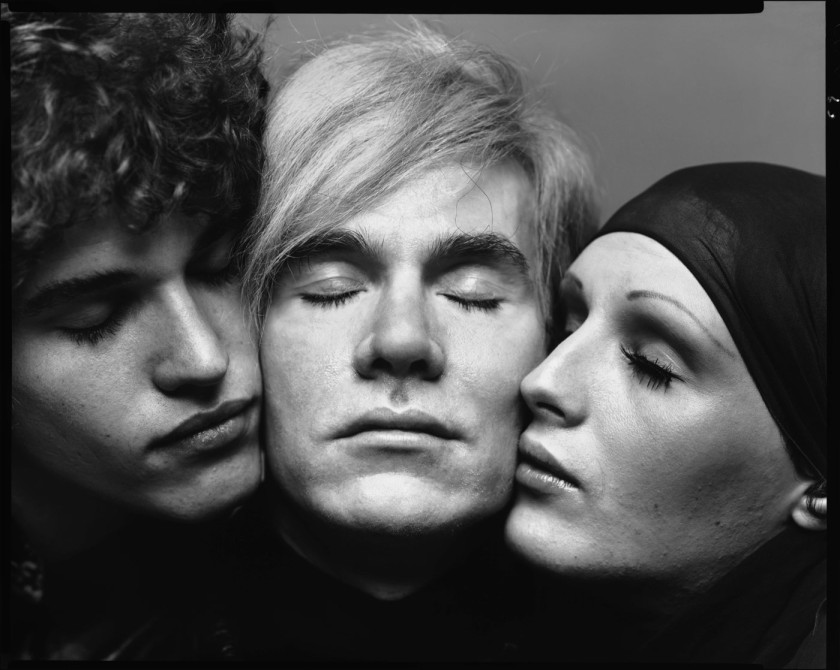

Christopher Makos (American, b. 1948)

Andy Warhol in Tiananmen Square

1982

© Christopher Makos 1982, makostudio.com

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei at the NGV maps out where the two artists intersect. Works such as Ai’s neolithic urn defaced with a Coca-Cola logo seem to echo Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans. But it would be reductive to call Ai “the Andy Warhol of 2015”. He says the show is interesting because it simultaneously highlights how close but also “so far away, so far apart” the artists are in their respective cultural backgrounds.

In their art, Ai aggressively engages with politics and current affairs (such as his moving roll call of the more than 5,000 students that died in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake) while Warhol was forever occupied with consumerism, pop culture iconography and celebrity.

A frisson is created by their respective portrayals of Mao Zedong hung in tandem. Ai says Warhol was a “very keen and very sensitive” artist, but portrayed the chairman as “no different to Marilyn Monroe or a Coca-Cola sign – purely a sign or signature of that time.”

The Chinese artist has a very different relationship to the ruthless political leader who he says was “very responsible” for damaging the nation, the destruction of so much Chinese tradition and so much personal, family crisis (Ai’s father, the notable poet Ai Qing, was exiled to Xinjiang as part of the late 1950s anti-rightist campaign).

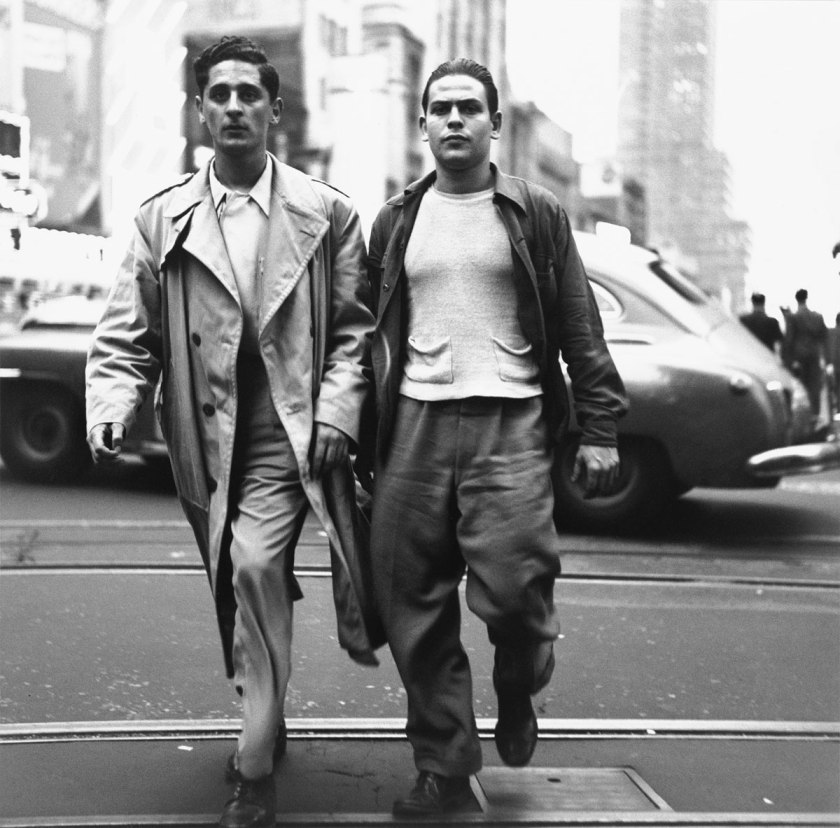

In another room Warhol’s photographic impressions of China during a 1982 visit face Ai’s photos of his life in New York. Ai finds it strange Warhol visited the country since it was “every bit” the opposite of what he believed. “He said China was not beautiful because it didn’t have McDonald’s yet.”

Extract from Monica Tan. “Ai Weiwei interview: ‘In human history, there’s never been a moment like this’,” on The Guardian website, 10th December 2015 [Online] Cited 23/03/2016.

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Self-Portrait

1981

Polaroid™ Polacolor 2

3 3/8 x 4 1/4 in. (8.6 x 10.8cm)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

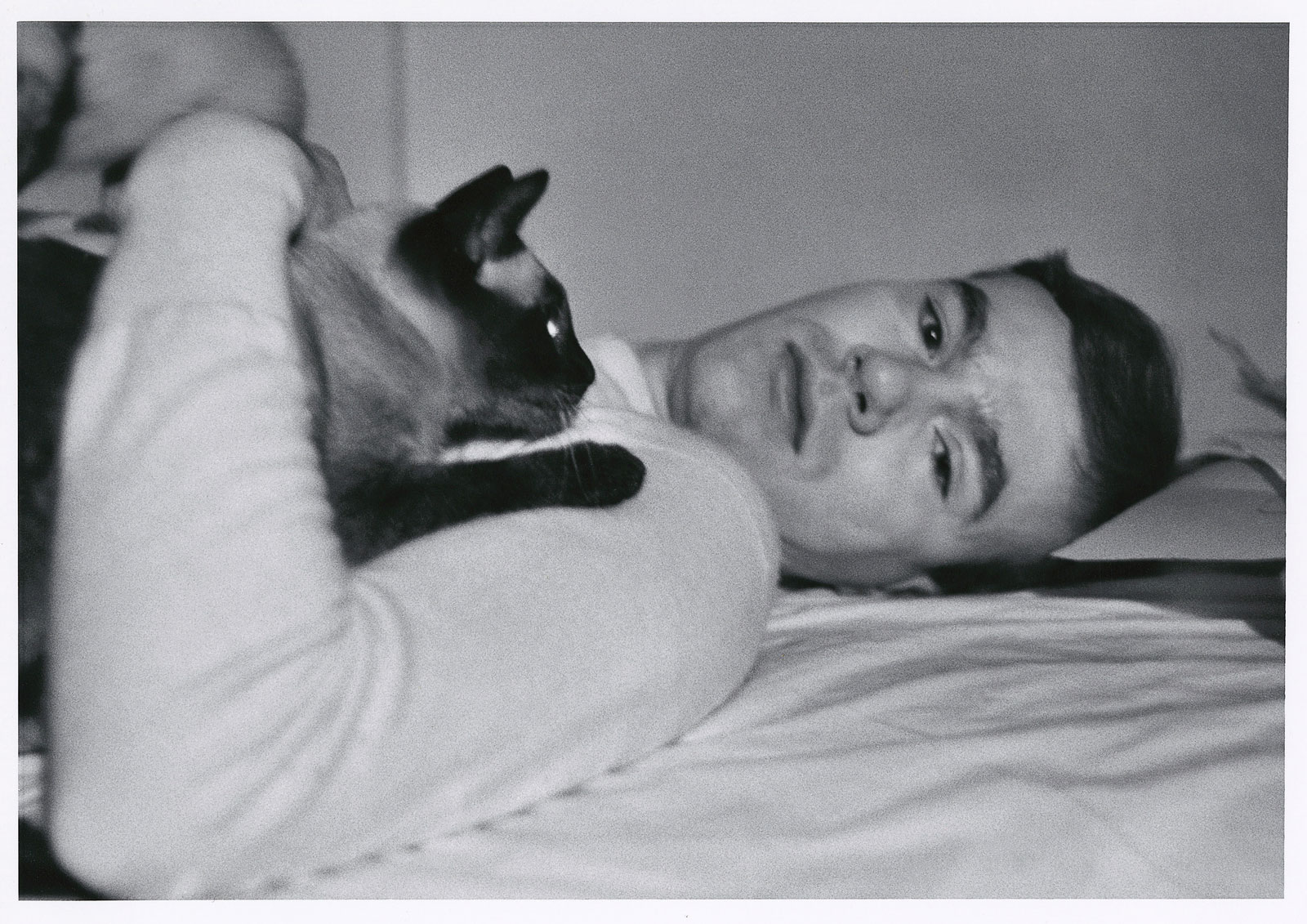

Edward Wallowitch (American, 1933-1981)

Andy Warhol Holding Kitten

1957

Gelatin silver photograph

13.3 x 17.5cm (sheet)

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh

Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. (1998.3.2810)

© 2015 Estate of Edward Wallowitch, all rights reserved

Edward Wallowitch (American, 1933-1981)

Andy Warhol with Siamese Cat

c. 1957

Gelatin silver photograph

14.9 × 21.6cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 Estate of Edward Wallowitch, all rights reserved

AW: Contemporary art always changes its own form; it is always questioning its own condition. Social media is a way to connect and, for me as an artist, it is also a way to connect to reality and search for new expressions and ways to communicate. This has become essential because contemporary art is not a series but a practice. It is connected to our inherent human need to express our inner world, and to make that association possible with others. Social media is the best for this purpose.

MD: Warhol’s Polaroids and portrait paintings not only document his social milieu but also constitute a form of history painting. You recently embarked upon two major portrait projects, including Trace, 2014, and Letgo, 2015, focusing on Australian activists, advocates and champions of human rights and freedom of speech. Can you expand on the relationship between portraiture, celebrity, dissidence and political authority?

AW: These things differ a lot and they form different sections of human expression. As humans, our feelings relate to our desires, fears, anxieties or inner needs for justice and fairness. Above all, we have the idea of right or wrong, but we also make aesthetic judgements about proportion, light, colour, shape and sound. All these aspects have to work together to express ourselves.

Our values are not abstract. They are really about out wellbeing as humanity. We’re dealing with different societies, Andy Warhol and I. We are involved with very different social and political circumstances. But we’re both trying to face out reality honestly and to give a better illustration of our time.

Ai Weiwei quoted in “Max Delany in conversation with Ai Weiwei,” in Gallery magazine, January-February 2016. National Gallery of Victoria, 2016, p. 29.

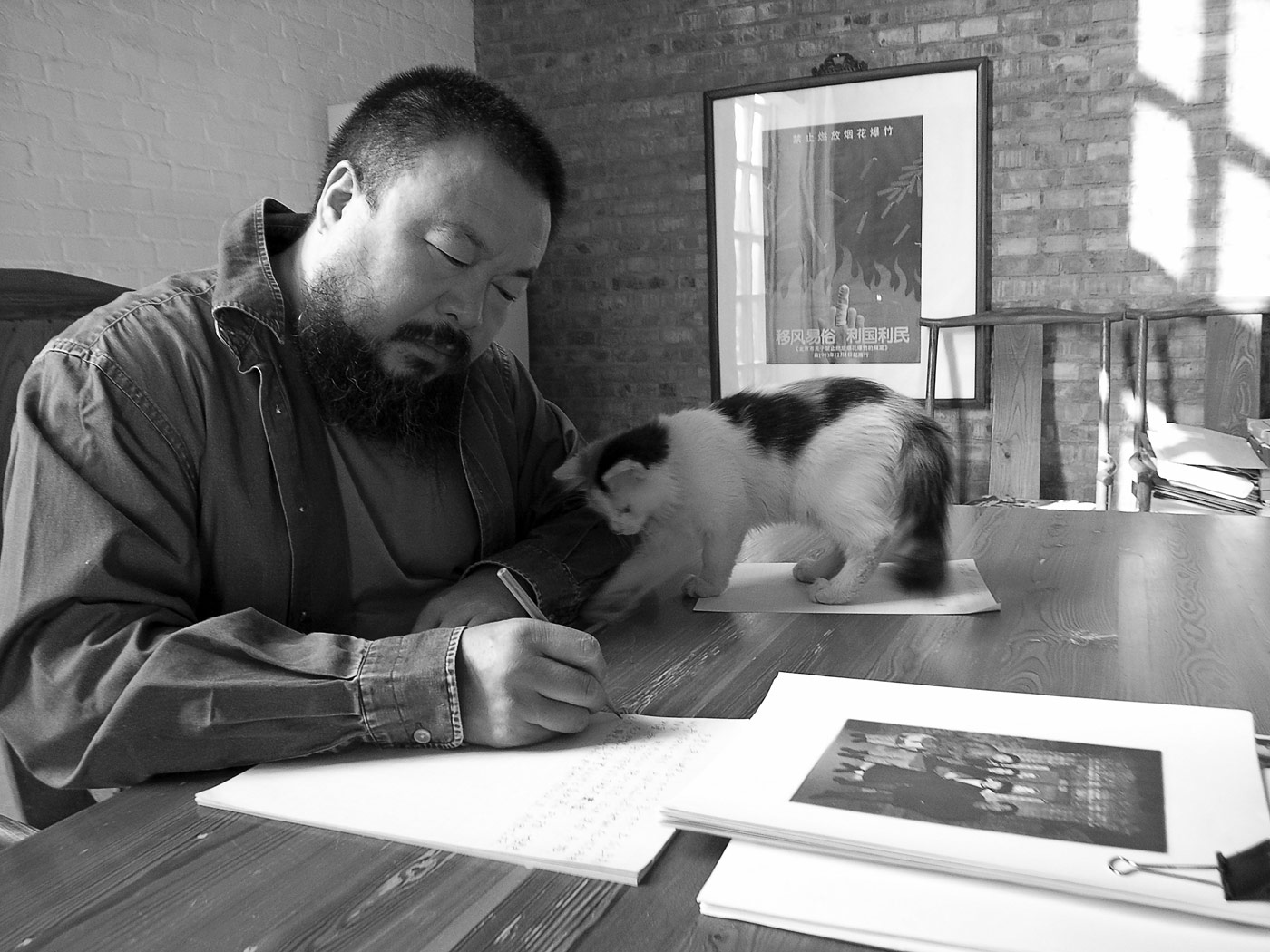

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Ai Weiwei with cat, @aiww, Instagram

2006

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]

1965

16mm film, black-and-white, silent, 4.6 minutes at 16 frames per second

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, a museum of Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved

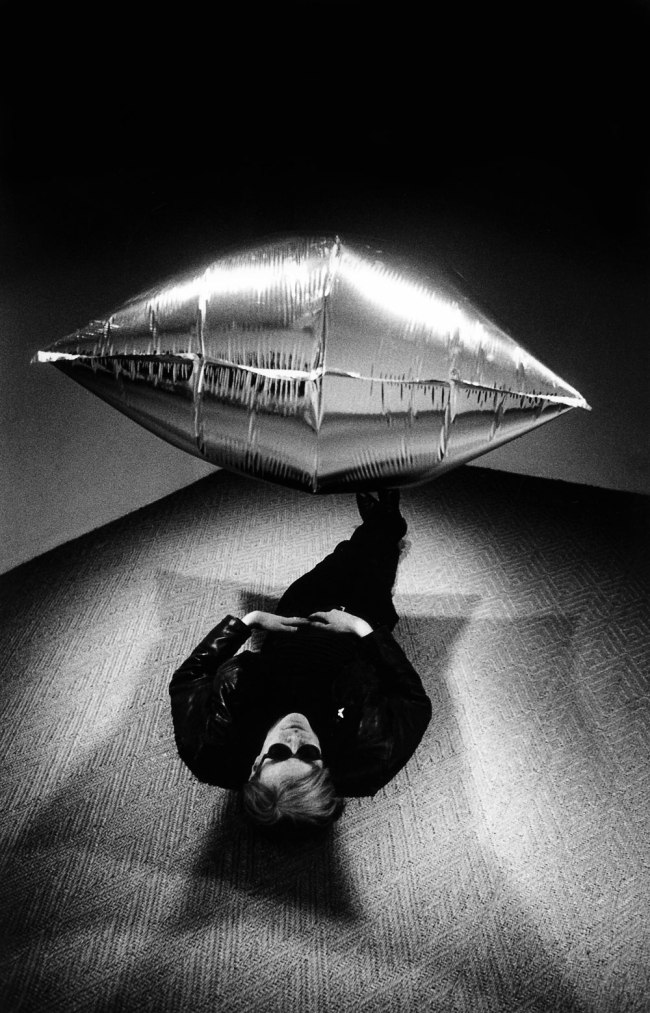

Steve Schapiro (American, 1934-2022)

Andy Warhol Under the Silver Cloud Pillow, New York

1965

© Steve Schapiro; Andy Warhol artwork

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

A major international exhibition featuring two of the most significant artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries – Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei – will open at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), Melbourne, in December 2015, and The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, in June 2016.

Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, developed by the NGV and The Warhol, with the participation of Ai Weiwei, will explore the significant influence of these two exemplary artists on modern and contemporary life, focussing on the parallels, intersections and points of difference between the two artists’ practices. Surveying the scope of both artists’ careers, the exhibition at the NGV will present over 300 works, including major new commissions, immersive installations and a wide representation of paintings, sculpture, film, photography, publishing and social media.

Presenting the work of both artists’ in dialogue and correspondence, the exhibition will explore modern and contemporary art, life and cultural politics through the activities of two exemplary figures – one of whom represents twentieth century modernity and the ‘American century’; and the other contemporary life in the twenty-first century and what has been heralded as the ‘Chinese century’ to come.

Ai Weiwei commented, “I believe this is a very interesting and important exhibition and an honour for me to have the opportunity to be exhibited alongside Andy Warhol. This is a great privilege for me as an artist.”

Ai Weiwei lived in the United States from 1981 until 1993, where he experienced the works of Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, among others. The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again) was the first book that Ai Weiwei purchased in New York, and was a significant influence upon his conceptual approach. Ai Weiwei’s relationship to Warhol is explicitly apparent in a photographic self-portrait (taken in New York in 1987) in which Ai Weiwei poses in front of Warhol’s multiple self-portrait, adopting the same gesture.

Each artist is also recognised for his unique approach to notions of artistic value and studio production. Warhol’s Factory was legendary for its bringing together of artists and poets, film-makers and musicians, bohemians and intellectuals, drag queens, superstars and socialites, and for the serial-production of silkscreen paintings, films, television, music and publishing.

The studio of Ai Weiwei is renowned for its interdisciplinary approach, post-industrial modes of production, engagement with teams of assistants and collaborators, and strategic use of communications technology and social media. Both artists have been equally critical in redefining the role of ‘the artist’ – as impresario, cultural producer, activist, and brand – and both are known for their keen observation and documentation of contemporary society and everyday life.

Andy Warhol (born Pittsburgh 1928 – died New York 1987) was a leading protagonist in the development of Pop Art, and his influence extended beyond the world of fine art to music, film, television, celebrity and popular culture. Warhol created some of the most defining iconography of the late twentieth century, through his exploration of consumer society, fame and celebrity, media, advertising, politics and capital.

The NGV will present over 200 of Warhol’s most celebrated works including portraits, paintings and silkscreens such as Campbell’s Soup, Mao, Elvis, Three Marilyns, Flowers, Electric Chairs, Skulls and Myths series; early drawings and commercial illustrations from the 1950s; sculpture and installation, including Brillo Boxes 1964, Heinz Tomato Ketchup Boxes 1964, and Silver Clouds 1968; films such as Empire 1964, Blow job 1964, and Screen Tests 1965, among others from Warhol’s extensive filmography; music and publishing; alongside a selection of previously unseen work. The exhibition will also bring together a wide range of photography including over 500 Polaroids documenting Warhol’s friends, colleagues, artistic and social milieux.

Ai Weiwei (born Beijing 1957) is an artist and social activist who is among the most renowned contemporary artists practicing today. One of China’s most provocative artists, his work encompasses diverse fields including visual art, architecture, publishing and curatorial practice, cultural criticism, social media and activism. Ai Weiwei’s work addresses some of the most critical global issues of the early twenty-first century, including the relationship between tradition and modernity, the role of the individual and the state, questions of human rights, and the value of freedom of expression.

For the NGV exhibition, a suite of major commissions will be premiered, including a new installation from the Forever bicycles series and a new monumental work from his Chandelier series, among others. These will be presented alongside key works by Ai Weiwei from his early drawings in the 1970s, readymades of the 1980s, and painting, sculpture and photography of the 1990s and 2000s. New and recent installations, including new configurations of major works such as S.A.C.R.E.D. 2013 and Trace 2014, will sit alongside a wide range of photography, film and social media from over the past four decades. It will be the most comprehensive representation of the artist’s work in Australia to date.

Three major illustrated publications

The Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei exhibition will be accompanied by a suite of three dynamic and visually-led publication formats: a deluxe collectors’ book in a presentation case, including an original limited-edition print by Ai Weiwei; a prestigious hardback edition; and sumptuous paperback volume. The major publications will explore the conceptual, formal, strategic and historical resonances between both artists’ work.

Press release from the National Gallery of Victoria

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI) gallery

© Abby Warhola

Andy Warhol’s expanded cinema and multimedia performance the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI), featuring legendary rock group The Velvet Underground and Nico, debuted in April 1966 at The Dom, a Polish meeting hall in New York City. In the context of Warhol’s own practice, the EPI evolved from his work as a filmmaker, the social environment of his studio and earlier performances known as Andy Warhol, Up-Tight, in which members of Warhol’s entourage antagonistically confronted the audience while The Velvet Underground played onstage.

The EPI was a sensory assault – an immersive sound-and-light environment involving numerous collaborators. Warhol shot new footage that was projected simultaneously with older films as part of the show. Danny Williams helped orchestrate light effects, including strobes, spotlights and assorted coloured gels and mattes; Jackie Cassen created psychedelic slides; Gerard Malanga, Mary Woronov, and Ingrid Superstar staged dance routines with sadomasochistic theatrics; and The Velvet Underground performed their proto-punk songs and avant-garde rock improvisations at ear-splitting volume.

This evocation of the EPI is the result of detailed research by The Andy Warhol Museum into the original performances. It includes films that were projected during the shows, digitised copies of the slides, mattes that were used and live recordings of the Velvet Underground and Nico.

Text from exhibition labels

Steve Schapiro (American, 1934-2022)

Andy Warhol Blowing Up Silver Cloud Pillow, Los Angeles

1966

© Steve Schapiro; Andy Warhol artwork

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Ai Weiwei at National Gallery of Victoria exhibition Andy Warhol | Ai Weiwei, 11 December 2015 – 24 April 2016

Ai Weiwei artwork © Ai Weiwei

Photo: John Gollings

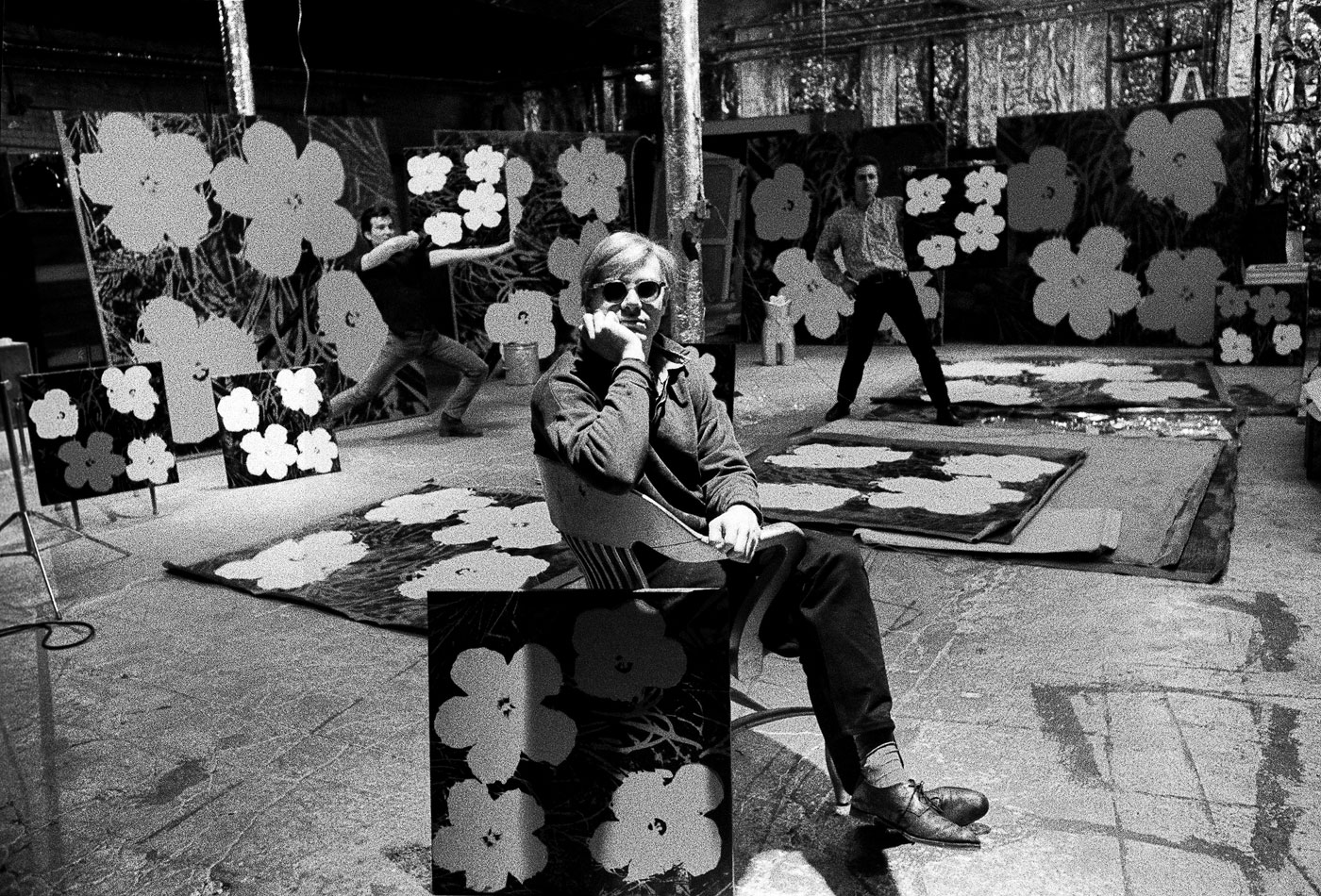

Ugo Mulas (Italian, 1928-1973)

Andy Warhol, Gerard Malanga and Philip Fagan in New York

1964

Image courtesy Ugo Mulas Archive

© Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved. Courtesy Archivio Ugo Mulas, Milano – Galleria Lia Rumma, Milano/Napoli; Andy Warhol artwork

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Coloured Vases

2006

Neolithic vases (5000-3000 BC) and industrial paint

Dimensions variable

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

In Ai’s series of Coloured Vases, ongoing since 2006, Neolithic and Han dynasty urns are plunged into tubs of industrial paint to create an uneasy confrontation between tradition and modernity. In what might be considered an iconoclastic form of action painting, Ai gives ancient vessels a new glaze and painterly glow, appealing to new beginnings and cultural change through transformative acts of obliteration, renovation and renewal.

Text from exhibition wall panel

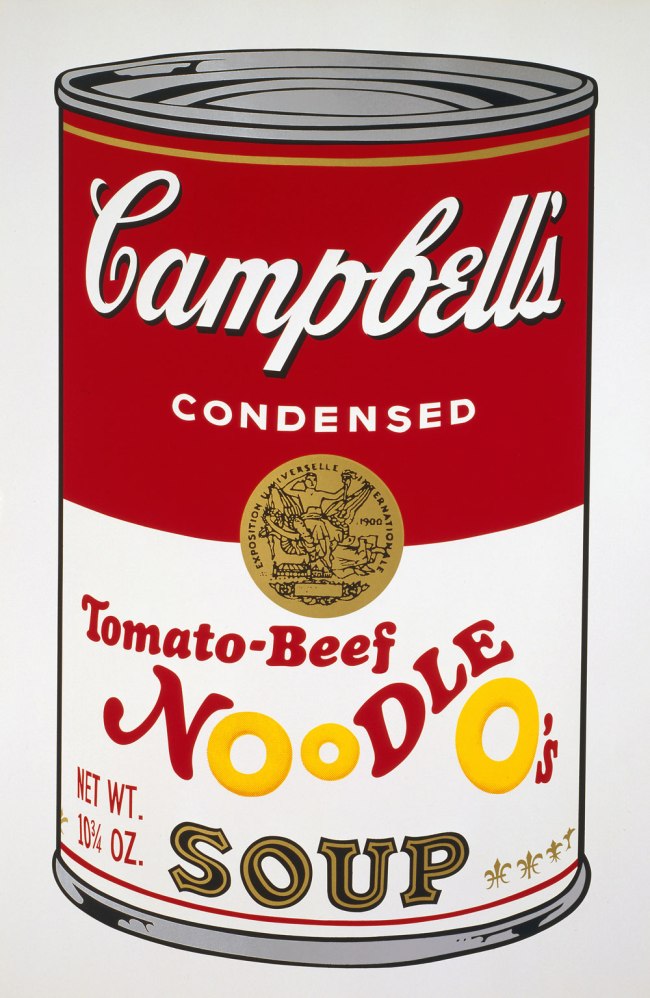

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Campbell’s Soup II: Tomato-Beef Noodle O’s

1969

Screen print on paper

88.9 x 58.4cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Warhol’s paintings of Campbell’s Soup Cans were first exhibited at the Ferus Gallery, Los Angeles, in 1962, and he returned to the subject repeatedly throughout his career. The works’ readymade commercial imagery, mechanical manufacture and serial production ran counter to prevailing artistic tendencies, offering a comment on notions of artistic originality, uniqueness and authenticity. The familiar red-and-white label of a Campbell’s Soup can was immediately recognisable to most Americans, regardless of their social or economic status, and eating Campbell’s Soup was a widely shared experience. This quintessential American product represented modern ideals: it was inexpensive, easily prepared and available in any supermarket.

Text from exhibition wall panel

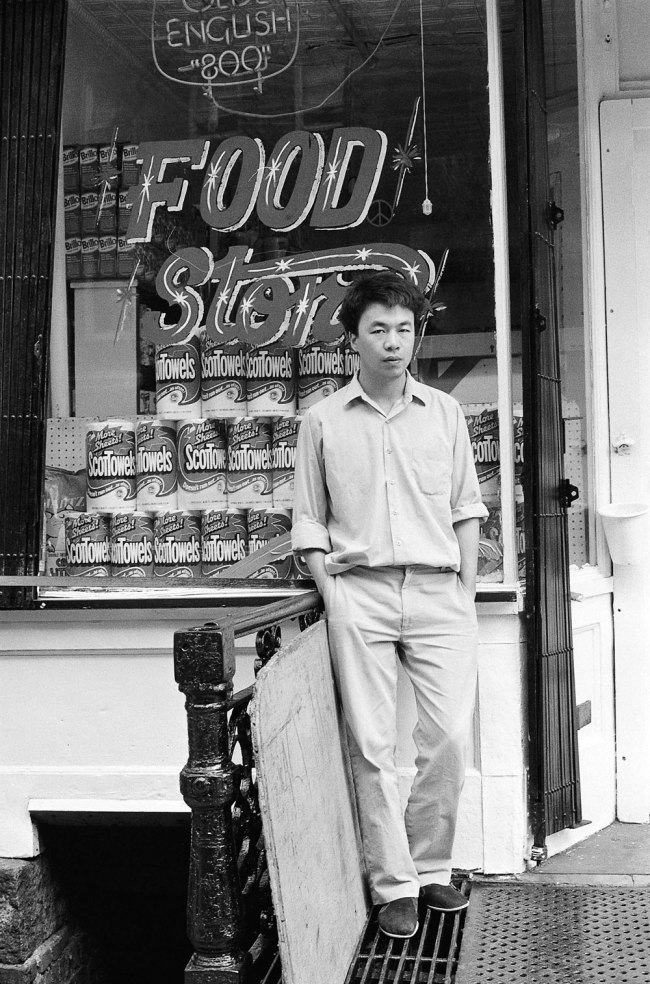

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Williamsburg, Brooklyn

1983

From the New York Photographs series 1983-93

Silver gelatin photograph

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Brillo Soap Pads Box

1964

Silkscreen ink and house paint on plywood

43.2 x 43.2 x 35.6cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

First created in late 1963, Warhol’s Brillo Soap Pads Box recasts the Duchampian readymade through the lens of American popular culture. Warhol produced approximately 100 of these boxes for his exhibition at Stable Gallery, New York, in March 1964, where they were tightly packed and piled high in a display reminiscent of a grocery warehouse. Unlike Duchamp’s use of real objects as readymade works of art, Warhol’s Brillo Soap Pads Boxes are carefully painted and silkscreened to resemble everyday consumer items. For philosopher Arthur C. Danto, Warhol’s Brillo boxes marked the end of an art-historical epoch and represented a new model of how art could be produced, displayed and perceived.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Forever Bicycles

2011

Installation view at Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Image courtesy Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

The assembly and replication of readymade bicycles in Ai’s Forever Bicycles series, ongoing since 2003, promotes an intensely spectacular effect. ‘Forever’ is a popular brand of mass-produced bicycles manufactured in China since the 1940s and desired by Ai as a child. Composed from almost 1500 bicycles, this installation suggests both the individual and the multitude, with the collective energy of social progress signalled in the assemblage and perspectival rush of multiple forms.

Forever Bicycles disconnects the bicycles from their everyday function – reconfiguring them as an immense labyrinth-like network. The multi-tiered installation also achieves an architectural presence, much like a traditional arch or gateway to the exhibition.

Text from exhibition wall panel

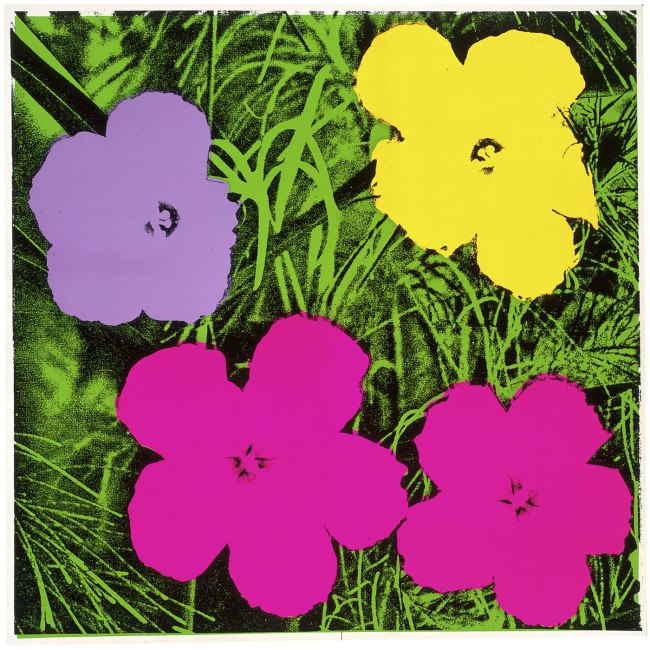

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Flowers

1970

Screen print on paper

91.4 x 91.4cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Experimenting with decoration – one of modernist painting’s most controversial subjects – Warhol’s Flowers prints were exhibited in tight grids at his first show at Leo Castelli Gallery, New York City, in 1964. A subsequent series was exhibited in Paris, where more than 100 works were hung almost edge to edge, mimicking the decorative effect of wallpaper. The source photograph, taken by Patricia Caulfield, appeared in the June 1964 issue of Modern Photography magazine. Caulfield sued to maintain ownership of the image, and while the suit was settled out of court, the issues of authorship and copyright it raised remain relevant to contemporary art debates.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Flowers

Flowers in Western art history have symbolised love, death, sexuality, nobility, sleep and transience. In Chinese culture flowers also carry rich and auspicious symbolic meanings; from wealth and social status to beauty, reflection and enlightenment. The flower is a repeated motif in Andy Warhol’s work, from his earliest drawings and commercial illustrations to his Pop paintings and prints, first shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, in 1964. While the production of Warhol’s Flower paintings and silkscreens through the 1960s and early 1970s coincided with the burgeoning Flower Power movement, their bold plasticity, mechanical reproduction and seriality also suggested a more commercial undercurrent to the counterculture.

Flowers feature repeatedly in the work of Ai Weiwei, from his celebrated Sunflower Seeds, 2010, to a new installation, Blossom, 2015, composed of thousands of delicate white flowers created in the finest traditions of Chinese porcelain production. Along with poetic ideals of beauty, remembrance and renewal Ai directs the symbolism of flowers towards political ends in projects such as With Flowers, 2013-15, a daily act of placing fresh flowers in the basket of a bicycle outside Ai’s studio, for the benefit of surveillance cameras trained upon it. The act was a form of protest against the Chinese authorities’ confiscation of the artist’s passport and restriction of his right to travel freely.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Debbie Harry

1980

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen

106.7 x 106.7cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Self-Portrait

1966-67

Acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas

55.9 x 55.9cm

The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

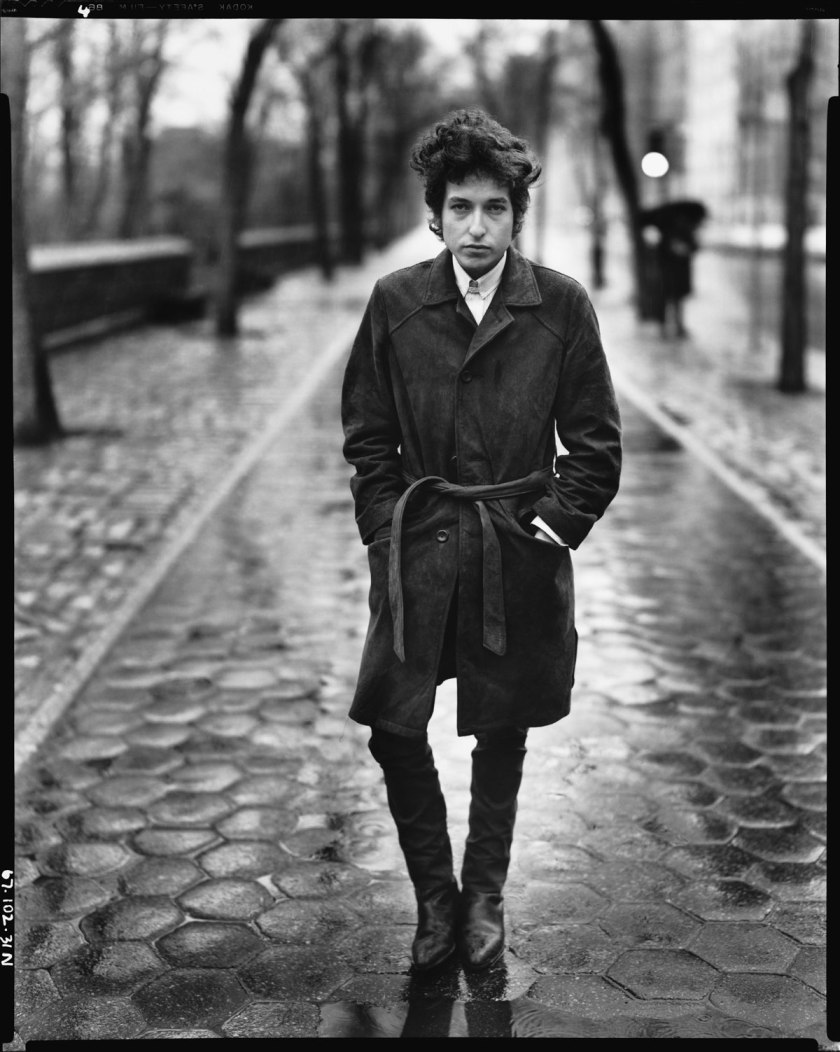

Ai Weiwei (Chinese 1957- )

At the Museum of Modern Art

1987

From the New York Photographs series 1983-93

Silver gelatin photograph

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei; Andy Warhol artwork © 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

New York / Beijing

Andy Warhol fanatically recorded his everyday life on audiotape, celluloid and photographic film. He moved effortlessly between underground, avant-garde and glamorous social circles and his photographs of the 1970s and 1980s provide an intimate insight into his social world. They also show his keen observation of the urban life, architecture, advertising, popular culture and personalities of his adopted New York City. When Warhol visited China in 1982, he turned his photographic gaze to the people and significant sites of a culture in transition.

Ai Weiwei lived in New York for a decade from 1983 onwards, and his New York Photographs document the young artist’s social context as part of the city’s Chinese artistic and intellectual diaspora community. The images also show his participation on the margins of the New York art world; his commitment to social activism; his involvement with influential poets, such as Allen Ginsberg; and his identification with the work of Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns and Warhol.

In one photograph, taken at the Museum of Modern Art in 1987 – the year of Warhol’s death – Ai, in his late twenties, identifies himself explicitly with Warhol by adopting a Warholian pose in front of the Pop artist’s multiple Self-Portrait of 1966.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Steve Schapiro (American, 1934-2022)

Andy Warhol Factory Portrait, New York

1963

© Steve Schapiro

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Electric Chair

1967

Synthetic polymer paint screenprinted onto canvas

137.2 x 185.1cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1977

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

This stark, singular image of an empty electric chair is one of Warhol’s most austere works. It is based on a 1953 death chamber photograph taken at New York’s notorious Sing Sing Prison, where the convicted Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been executed in January 1953 at the height of the Cold War. Warhol used this image for all of his Electric Chair paintings and prints, varying the cropping and background colours. As Warhol noted: ‘You’d be surprised how many people want to hang an electric chair on their living-room wall. Specially if the background colour matches the drapes’.

The Electric Chairs series of prints from 1971 employ imagery first developed in Warhol’s paintings of 1967. The repeated single image derives from a photograph of the electric chair in New York’s Sing Sing Penitentiary released by the press service Wide World Photo on the day two Soviet spies were executed in 1953, at the height of the Cold War. Warhol’s treatment, using pastel decorator colours applied in a painterly manner, contrasts with the macabre scene devoid of human presence.

Text from exhibition wall panels

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

S.A.C.R.E.D. (detail)

2011-13

6 dioramas; fibreglass, iron

377.0 x 197.0 x 148.4cm (each)

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

Ai’s major installation S.A.C.R.E.D., [is] a series of architecturally scaled dioramas depicting scenes from the detention cell where he was held without charge by the Chinese government for eighty-one days in 2011. The work consists of six parts to which its acronymic title refers: Supper, Accusers, Cleansing, Ritual, Entropy and Doubt. The maquettes serve as archaeological evidence of the denial of personal freedom and dignity that Ai and many other dissidents have experienced, and cast him in the dual roles of rebel and victim of oppression.

Text from exhibition wall panel

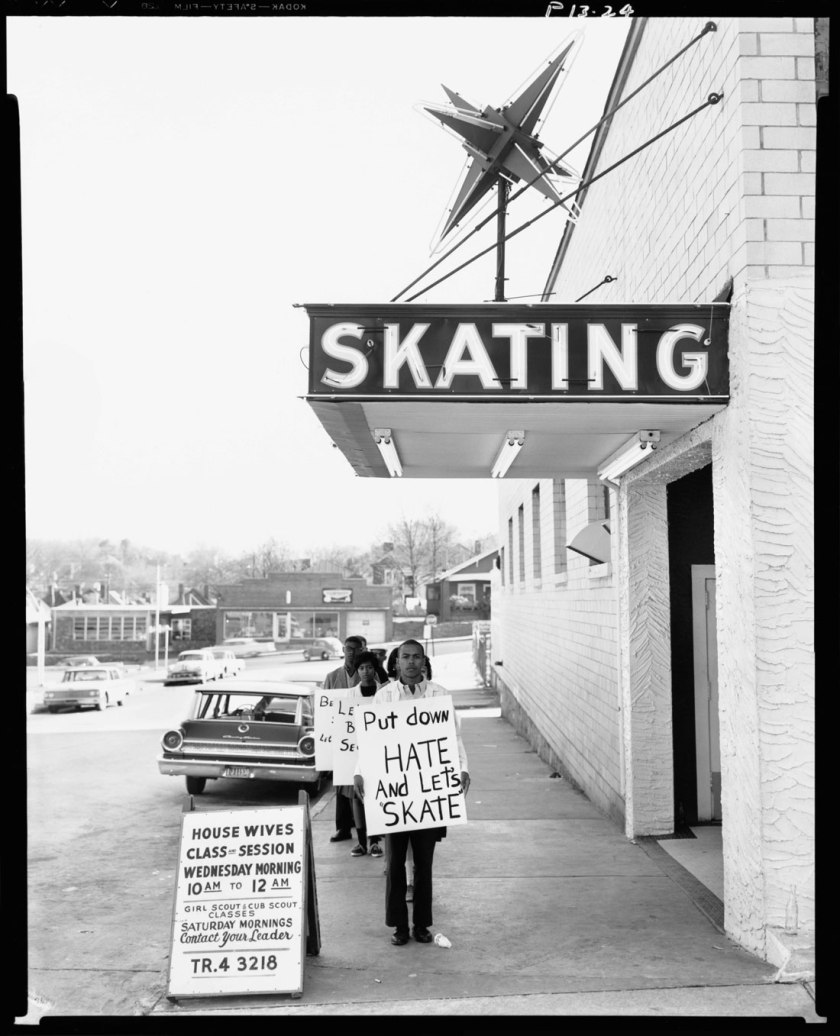

The individual and the state

The relationship between individual freedom and state power is a relevant subject for both Andy Warhol and Ai Weiwei. Warhol began exploring the electric chair as a motif in 1963, and the image remains a potent symbol of state disciplinary power. The artist’s celebrated Death and Disaster series – including representations of political assassinations, guns and knives, the hammer and sickle and most-wanted men – also explores the glamorisation of violence in the United States. These works, as well as the spectacular images of capital itself in Warhol’s Dollar Signs series, might be seen as a grand narrative of his time.

As an artist and human rights activist committed to freedom of expression, Ai Weiwei has been a longstanding advocate of individual acts of resistance against state, political or corporate power. Ai’s irrepressible impulse to defy the authority of the state is illustrated through his art and political activism. Vocal criticisms of Chinese government policy made by Ai on his blog led to its shutdown by authorities in 2009, and he was detained without charge for eighty-one days in 2011. Ai regained the right to travel only recently, in July 2015, when his passport was reinstated.

Text from exhibition wall panel

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn

1995

3 silver gelatin photographs

148.0 x 120.0cm each (triptych)

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei (Chinese, b. 1957)

Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (details)

1995

3 silver gelatin photographs

148.0 x 120.0cm each (triptych)

Ai Weiwei Studio

© Ai Weiwei

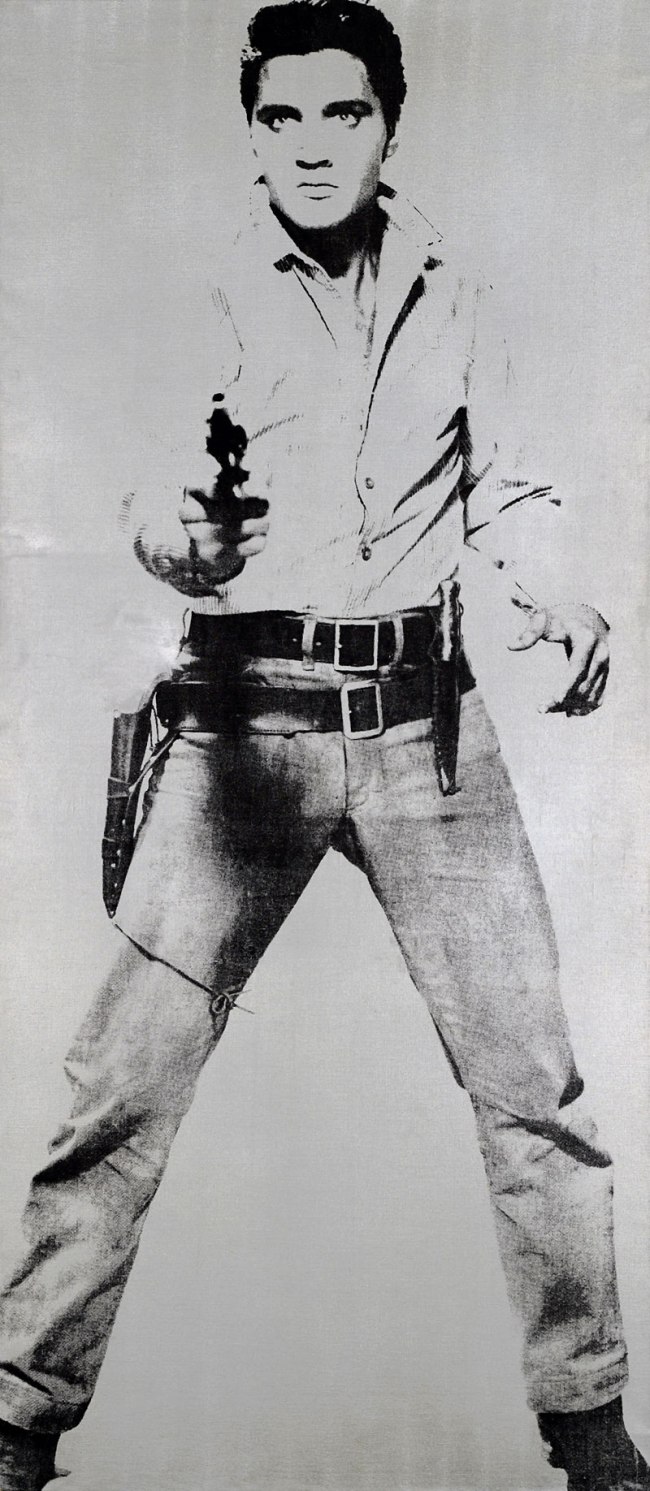

Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987)

Elvis

1963

Synthetic polymer paint screenprinted onto canvas

208 x 91cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1973

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS, New York. Licensed by Viscopy, Sydney

Warhol’s full-length portraits of Elvis Presley were first shown in 1963, accompanied by a series of portraits of film star Elizabeth Taylor. These large-scale screen-printed paintings show Warhol’s innovative painterly approach in the early 1960s. The image of popular American singer and actor Elvis Presley – derived from a publicity still for the film Flaming Star (1960) – captures him at the height of his acting career. The painting references the power and transience of fame while also highlighting violence in the cultural mythology of America.

Text from exhibition wall panel

NGV International

180 St Kilda Road

Opening hours for exhibition

10am – 5pm daily

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/exhi032777-web.jpg?w=650&h=652)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/exhi037605-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.