Exhibition dates: 6th December 2014 – 15th March 2015

Curator: Dr Christopher Chapman

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

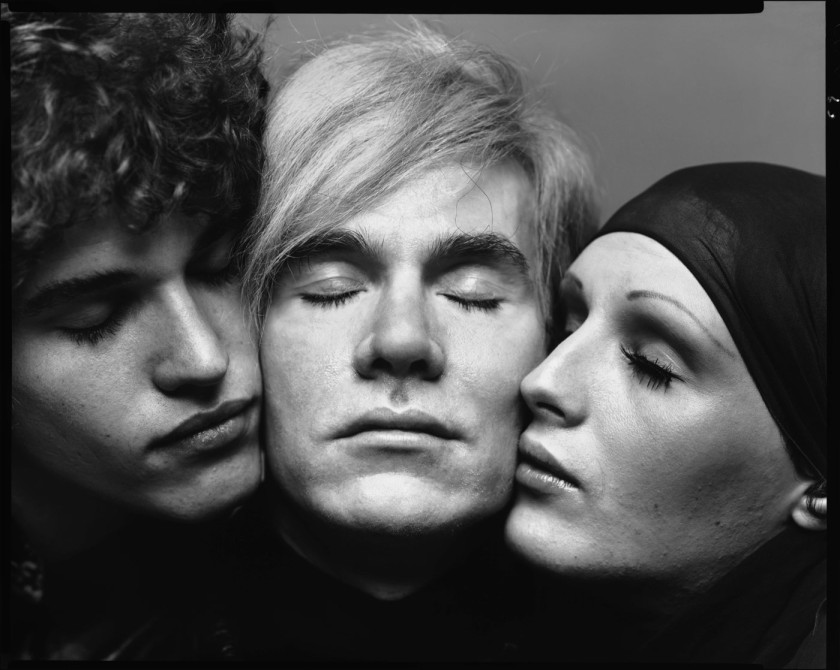

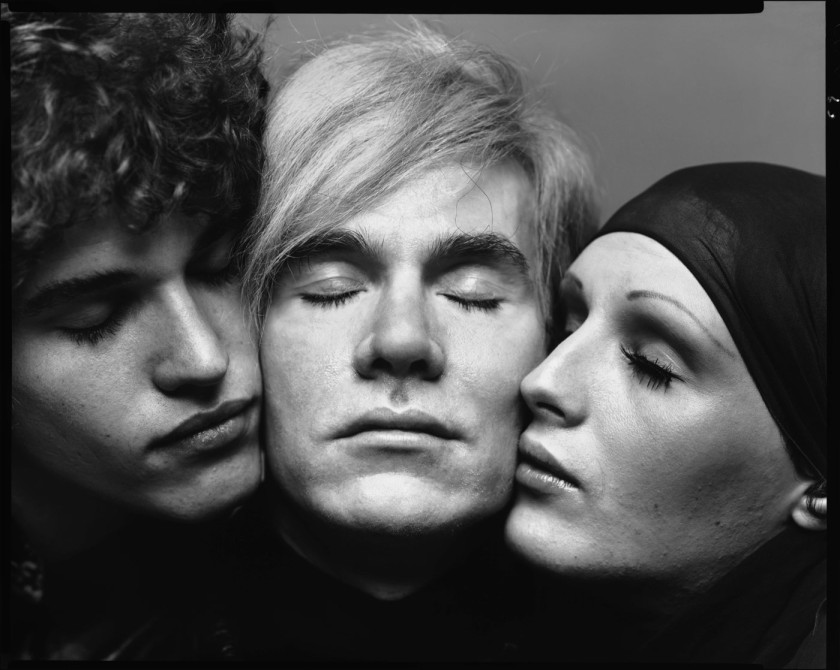

Andy Warhol, artist, Candy Darling and Jay Johnson, actors, New York, August 20, 1969

1969

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

You can tell a lot about a person from their self-portrait. In the case of Richard Avedon’s self-portrait (1969, below), we see a man in high key, white shirt positioned off centre against a slightly off-white background, the face possessing an almost innocuous, vapid affectation as though the person being captured by the lens has no presence, no being at all. The same could be said of much of Avedon’s photography. You can also tell a lot about an artist by looking at their early work. In the exhibition there is a photograph of James Baldwin, writer, Harlem, New York 1945, celebrated writer and close friend of the artist, which evidences Avedon’s mature portrait style: the frontal positioning of Afro-American Baldwin against a white background will be repeated by Avedon from the start to the end of his career. This trope, this hook has become the artist’s defining signature.

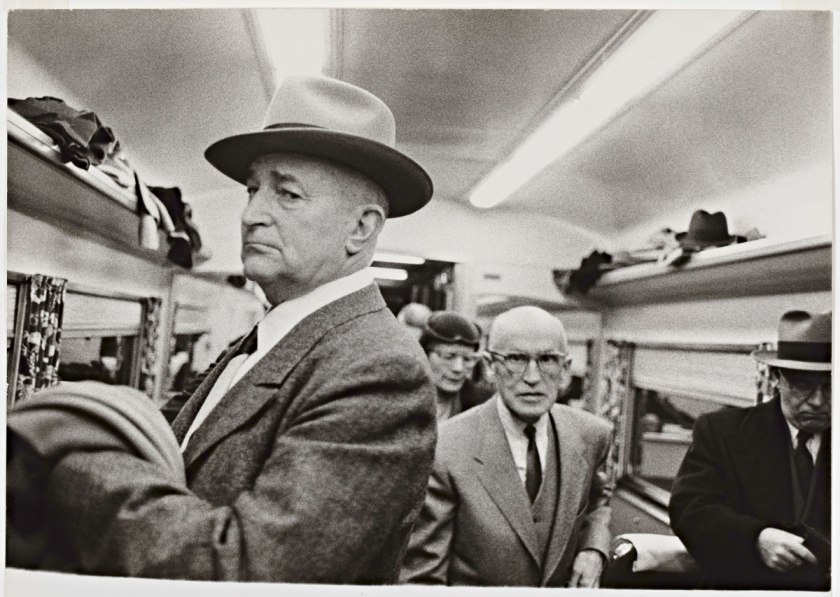

Spread across two floors of the exhibition spaces at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, the exhibition hangs well. The tonal black and white photographs in their white frames, hung above and below the line against the white gallery walls, promote a sense of serenity and minimalism to the work when viewed from afar. Up close, the photographs are clinical, clean, pin sharp and decidedly cold in attitude. Overall the selection of work in the exhibition is weak and the show does not promote the artist to best advantage. There are the usual fashion and portrait photographs, supplemented by street photographs, photographs at the beach and of mental asylums, and distorted photographs. While it is good to see a more diverse range of work from the artist to fill in his back story none of these alternate visions really work. Avedon was definitely not a street photographer (see Helen Levitt for comparison); he couldn’t photograph the mentally ill (see Diane Arbus’ last body of work in the book Diane Arbus: Untitled, 1995) and his distorted faces fail miserably in comparison to Weegee’s (Athur Fellig) fabulous distortions. These are poor images by any stretch of the imagination.

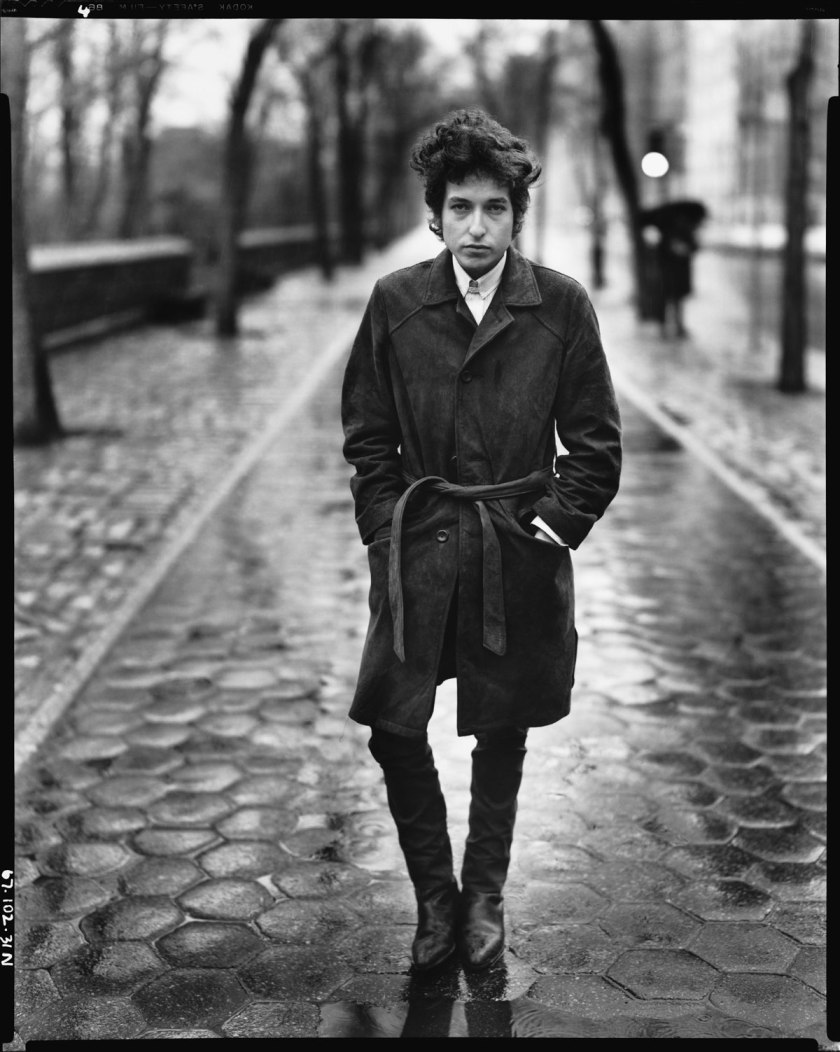

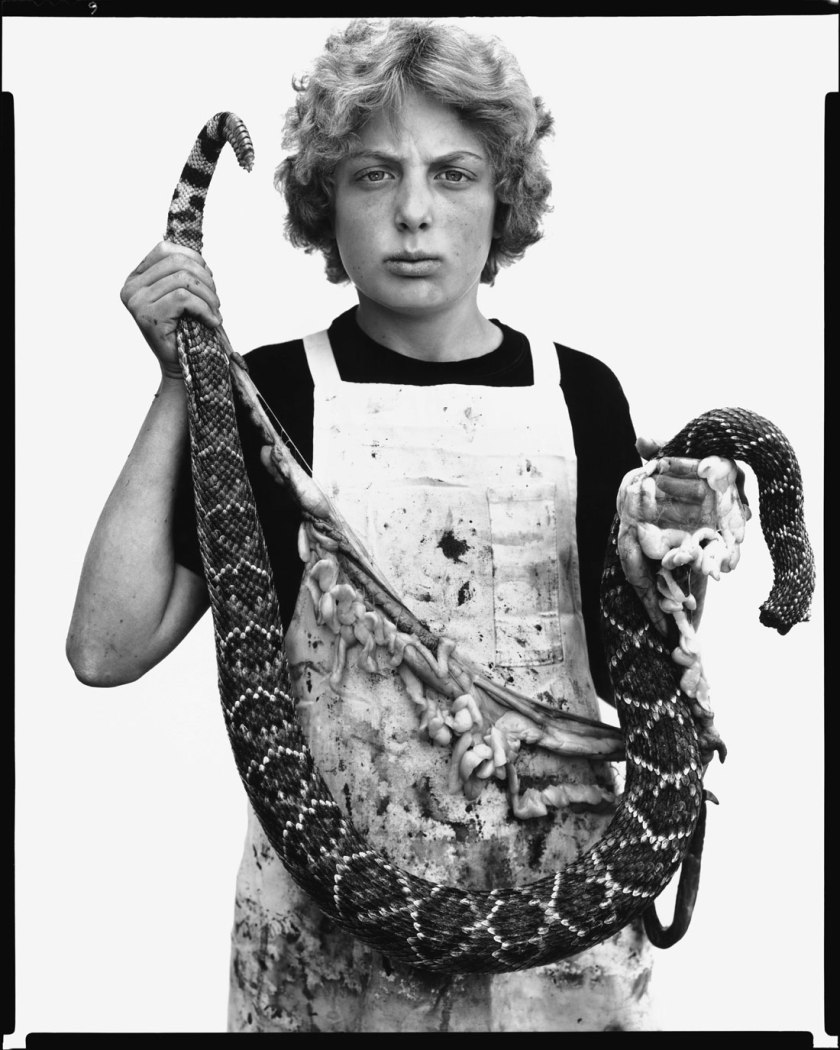

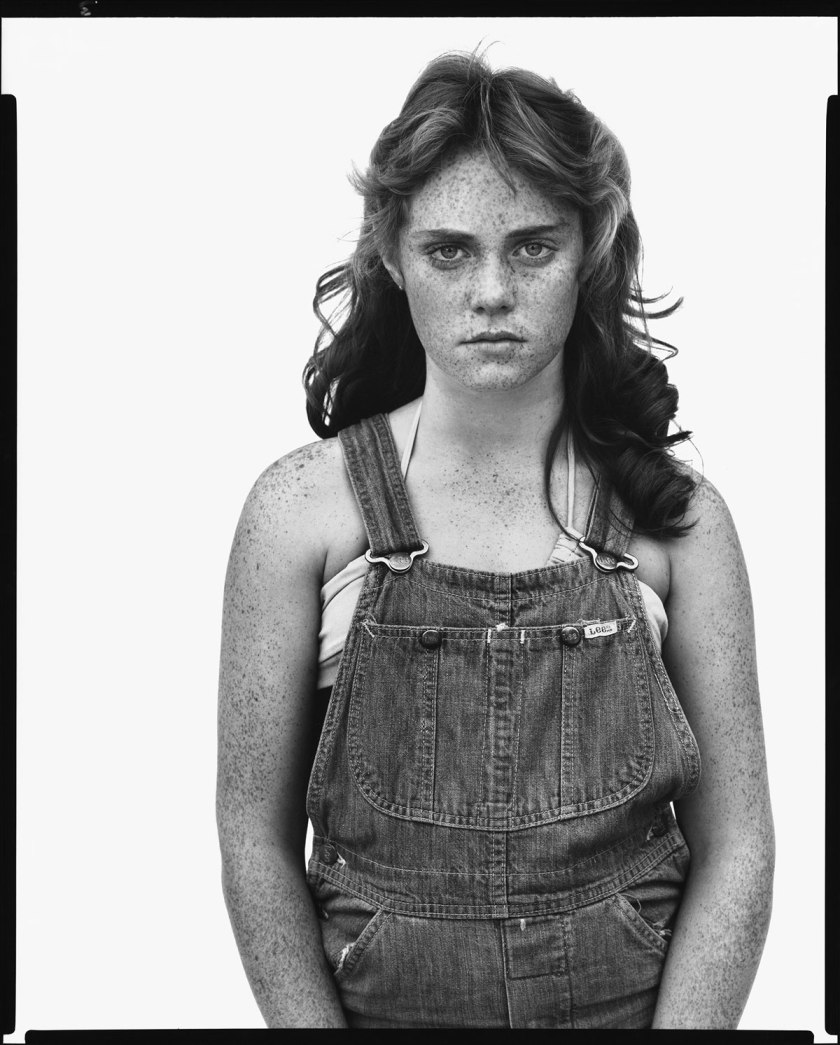

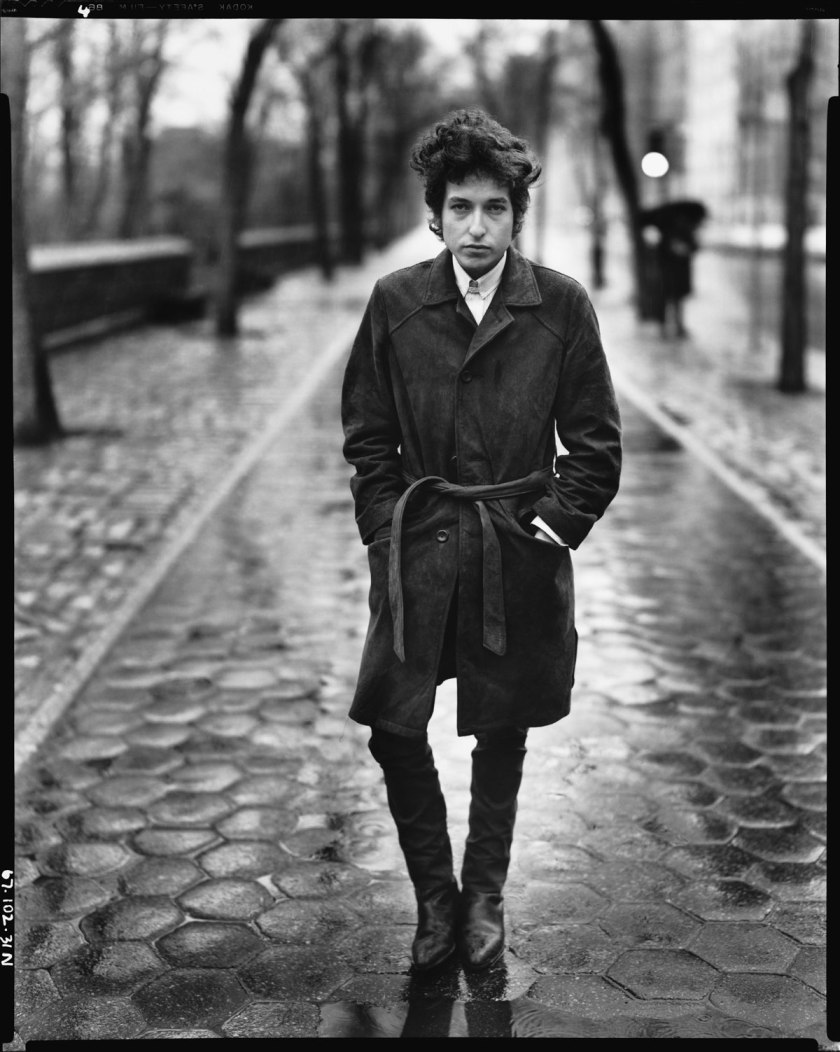

That being said there are some arresting individual images. There is a magical photograph of Truman Capote, writer, 1955 which works because of the attitude of the sitter; an outdoors image of Bob Dylan, musician, Central Park, New York, February 20, 1965 (below) in which the musician has this glorious presence when you stand in front of the image – emanating an almost metaphysical aura – due to the light, low depth of field and stance of the proponent. Also top notch is a portrait of the dancer Rudolf Nureyev, Paris, France, July 25, 1961, in which (for once), the slightly off-white background and the pallid colour of the dancer’s lithe body play off of each other, his placement allowing him to float in the contextless space of the image, his striking pose and the enormousness of his member drawing the eyes of the viewer. All combine to make a memorable, iconic image. Another stunning image is a portrait of the artist Pablo Picasso, artist, Beaulieu, France, April 16, 1958, where the artist’s large, round face fills the picture plane, his craggy features lit by strong side lighting, illuminating the whites of his eyes and just a couple of his eyebrow hairs. Magnificent. And then there are just two images (see below) from the artist’s seminal book In the American West. More on those later.

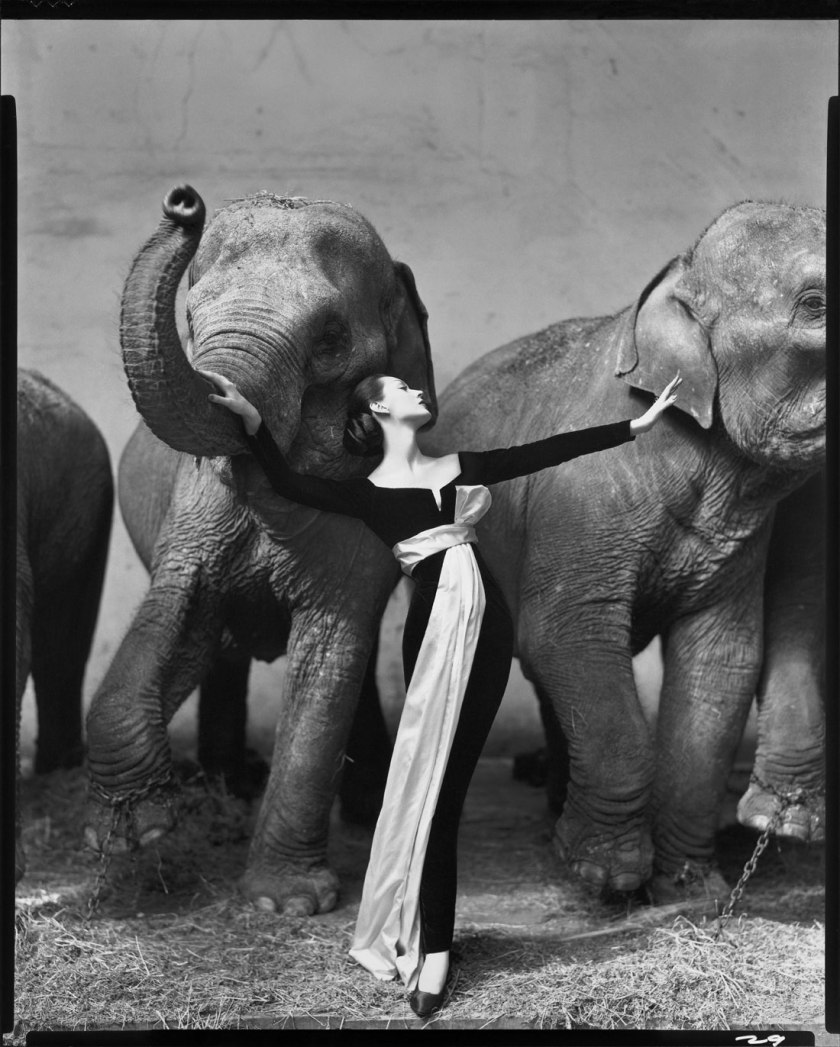

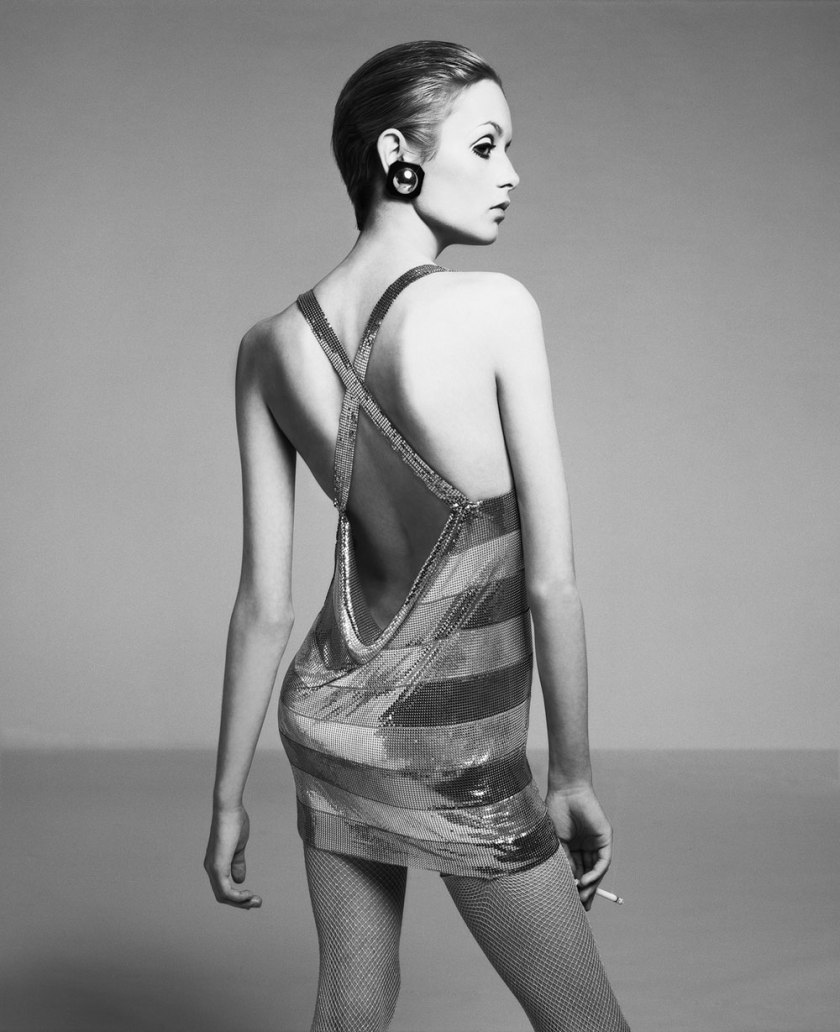

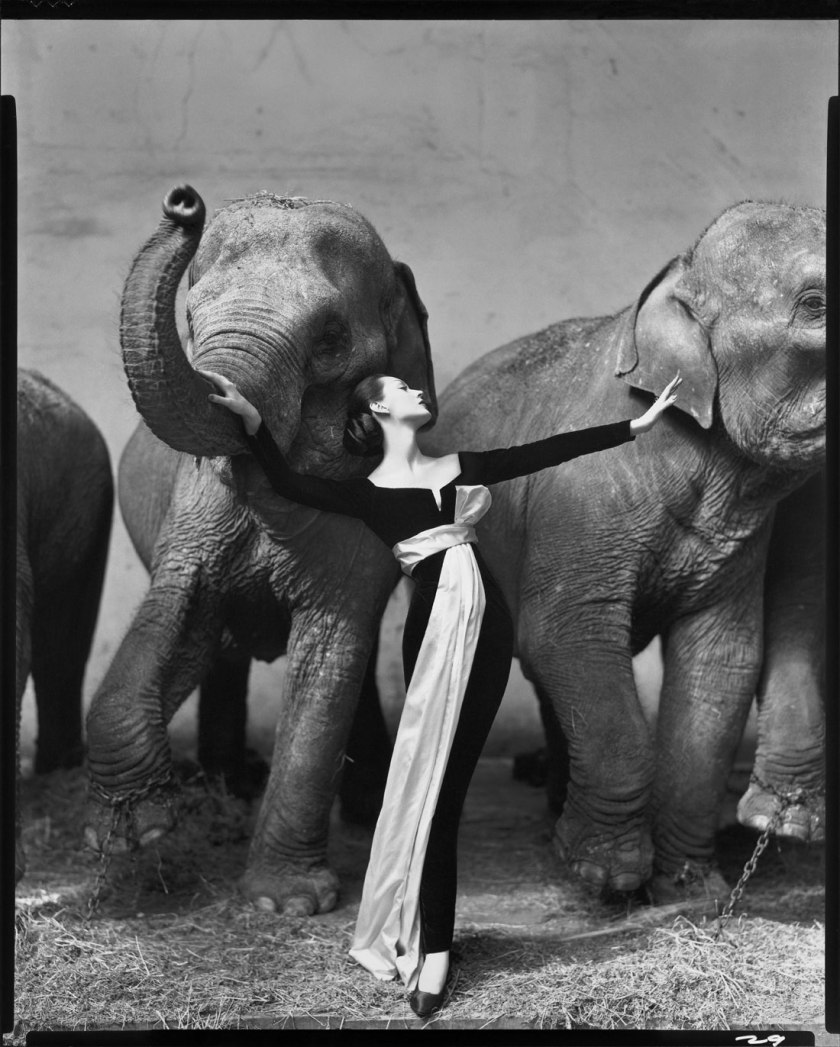

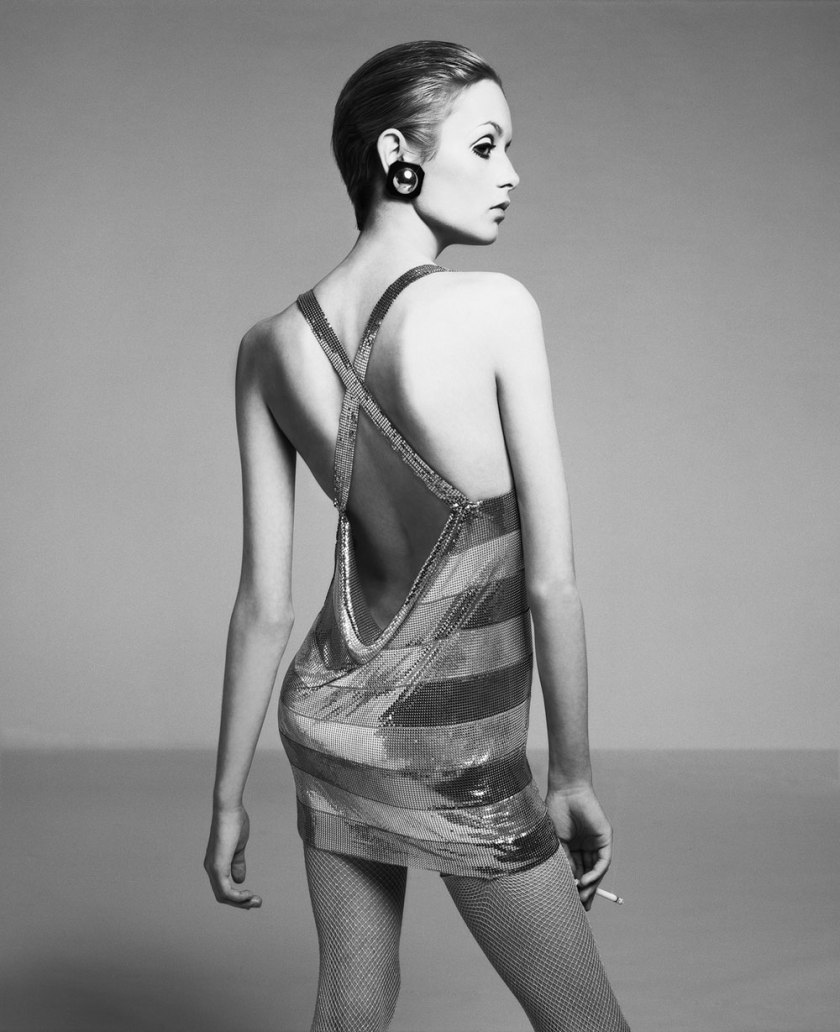

Other portraits and fashion photographs are less successful. A photograph of Twiggy, dress by Roberto Rojas, New York, April 1967 (below), high contrast, cropped close top and bottom, is a vapid portrait of the fashion/model. The image of Elizabeth Taylor, cock feathers by Anello of Emme, New York, July 1964 (below) is, as a good friend of mine said, a cruel photograph of the actress. I tend to agree, although another word, ‘bizarre’, also springs to mind. In some ways, his best known fashion photograph, Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver, Paris, August 1955 (below) is a ripper of an image… until you observe the punctum, to which my eyes were drawn like a moth to a flame, the horrible shackles around the legs of the elephants.

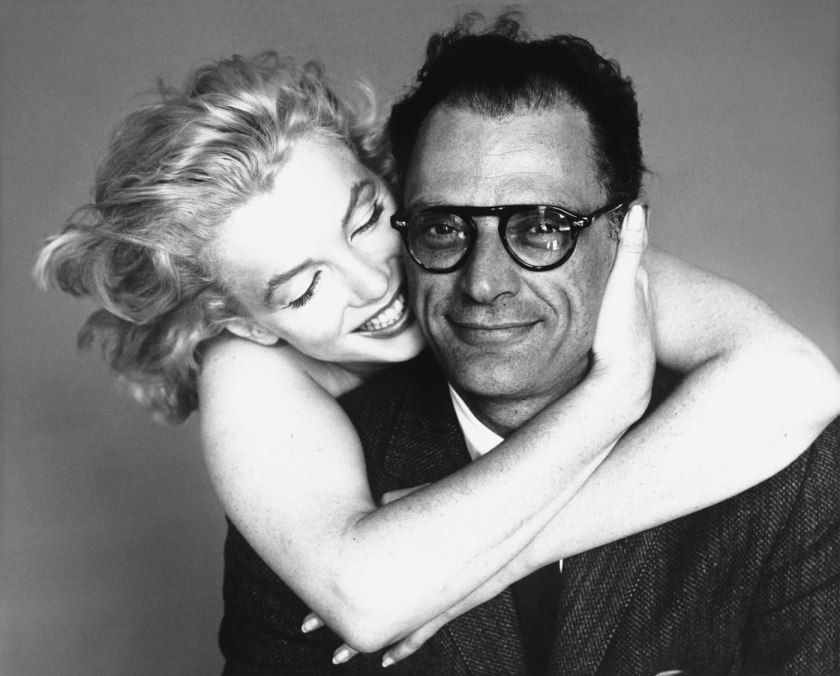

Generally, the portraiture and fashion photographs are a disappointment. If, as Robert Nelson in The Age newspaper states, “Avedon’s portraiture is a search for authenticity in the age of the fake,”1 then Avedon fails on many levels. His deadpan portraits do not revive or refresh the life of the sitter. In my eyes their inflection, the subtle expression of the sitter, is not enough to sustain the line of inquiry. I asked the curator and a representative from the Avedon Foundation what they thought Avedon’s photographs were about and both immediately said, together, it was all about surfaces. “Bullshit” rejoined I, thinking of the portrait of Marilyn Monroe, actress, New York, May 6, 1957 (below), in which the photographer pressed the shutter again and again and again as the actress gallivanted around his studio being the vivacious Marilyn, only hours later, when the mask had dropped, to get the photograph that he and everyone else wanted, the vulnerable women. This, and only this image, was then selected to be printed for public consumption, the rest “archived, protected by the Avedon Foundation, never allowed off the negative or the contact sheet.”2 You don’t do that kind of thing, and take that much time, if you are only interested in surfaces.

On reflection perhaps both of us were right, because there is a paradox that lies at the heart of Avedon’s work. There is the surface vacuousness and plasticity of the celebrity / fashion portrait; then the desire of Avedon to be taken seriously as an artist, to transcend the fakeness of the world in which he lived and operated; and also his desire to always be in control of the process – evidenced by how people had to offer themselves up to the great man in order to have their portrait taken, with no control over the results. While Avedon sought to be in touch with the fragility of humanity – the man, woman and child inside – it was also something he was afraid of. Photography gave him control of the situation. In his constructed images, Avedon is both the creator and the observer and as an artist he is always in control. This control continues today, extending to the dictions of The Richard Avedon Foundation, which was set up by Avedon during his lifetime and under his tenants to solely promote his art after he passed away.

When you look into the eyes of the sitters in Avedon’s portraits, there always seems to be a dead, cold look in the eyes. Very rarely does he attempt to reveal the ambiguity of a face that resists artistic production (see Blake Stimson’s text below). And when he does it is only when he has pushed himself to do it (MM, BD). Was he afraid, was he scared that he might have been revealing too much of himself, that he would have “lost control”? If, as he said, there is finally nothing but the face – an autograph, the signature of the face – then getting their autograph was a way to escape his mundane family life through PERFORMANCE. Unfortunately, the performance that he usually evinces from the rich and famous, this “figuring” out of himself through others through control of that performance – is sometimes bland to the point of indifference. Hence my comment on his self-portrait that I mentioned at the start of this review. It would seem to me that Avedon could not face the complex truth, that he could bring himself, through his portraits, to be both inside and outside of a character at one and the same time… to be vulnerable, to be frightened, to loose control!

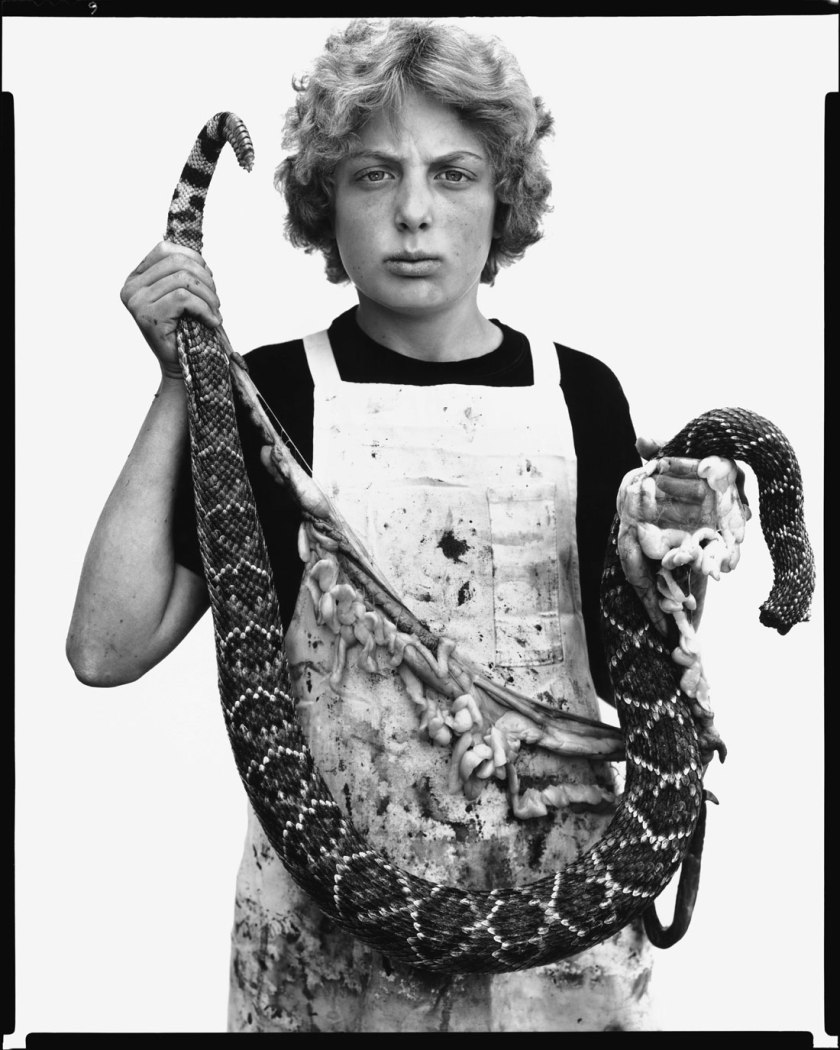

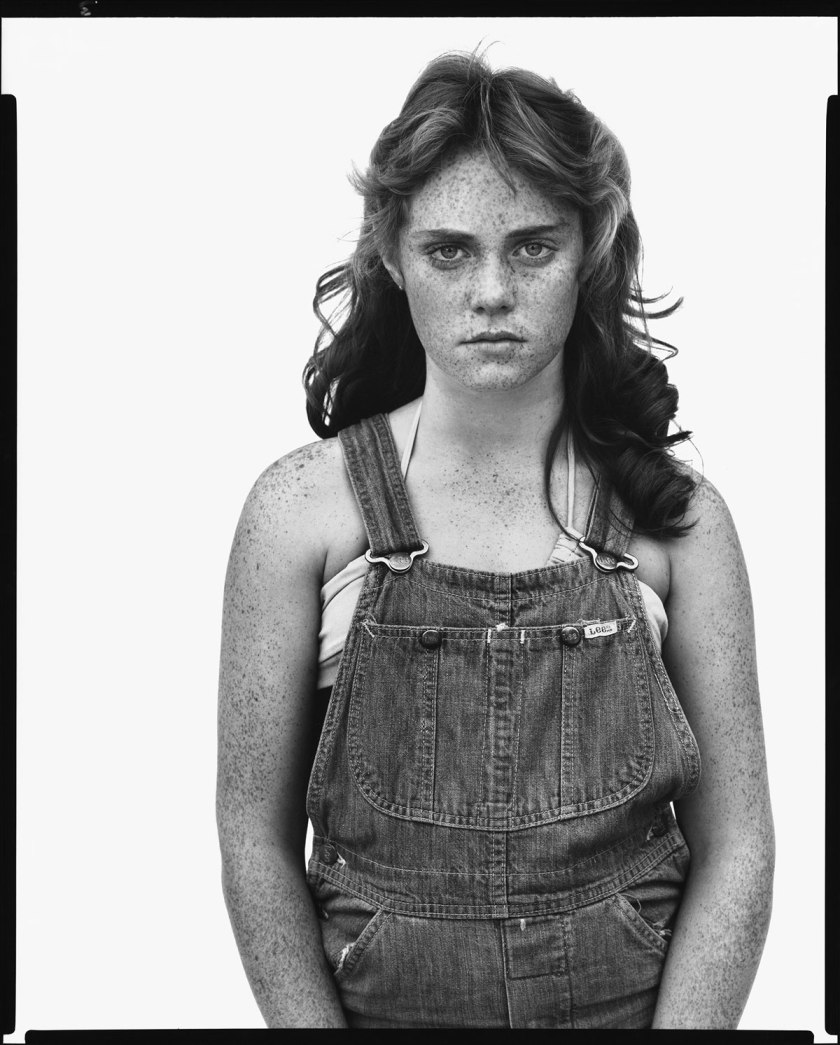

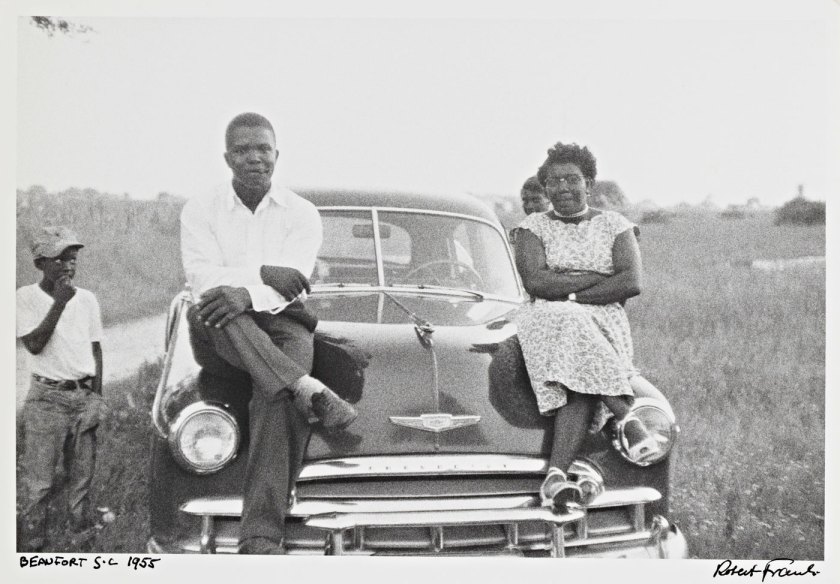

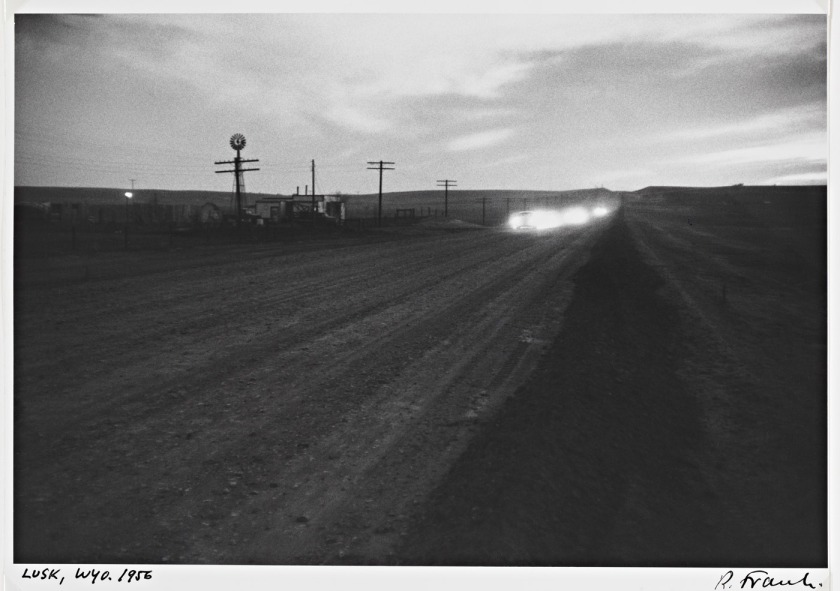

If he shines himself as a self-portrait onto others, in a quest or search for the human predicament, then his search is for his own frightened face. Only in the Western Project which formed the basis for his seminal book In the American West – only two of which are in the exhibition – does Avedon achieve a degree of insight, humanity and serenity that his other photographs lack and, perhaps, a degree of quietude within himself. Created after serious heart inflammations hindered Avedon’s health in 1974, he was commissioned in 1979 “by Mitchell A. Wilder (1913-1979), the director of the Amon Carter Museum to complete the “Western Project.” Wilder envisioned the project to portray Avedon’s take on the American West. It became a turning point in Avedon’s career when he focused on everyday working class subjects such as miners soiled in their work clothes, housewives, farmers and drifters on larger-than-life prints instead of a more traditional options with famous public figures… The project itself lasted five years concluding with an exhibition and a catalogue. It allowed Avedon and his crew to photograph 762 people and expose approximately 17,000 sheets of 8 x 10 Tri-X Pan film.”3

In his photographs of drifters, miners, beekeepers, oil rig workers, truckers, slaughterhouse workers, carneys and alike the figure is more frontally placed within the image space, pulled more towards the viewer. The images are about the body and the picture plane, about the minutiae of dress and existence and the presence and dignity of his subjects, more than any of his other work. In this work the control of the sitter works to the artist’s advantage (none of these people had ever had their portrait taken before and therefore had to be coached) and, for once, Avedon is not relying on the ego of celebrity of the transience of fashion but on the everyday attitudes of human beings. Through his portrayal of their ordinariness and individuality, he finally reveals his open, exposed self. The project was embedded with Avedon’s goal to discover new dimensions within himself… “from a Jewish photographer from out East who celebrated the lives of famous public figures to an ageing man at one of the last chapters of his life to discovering the inner-worlds, and untold stories of his Western rural subjects… The collection identified a story within his subjects of their innermost self, a connection Avedon admits would not have happened if his new sense of mortality through severe heart conditions and ageing hadn’t occurred.”4 Definitively, this is his best body of work. Finally he got there.

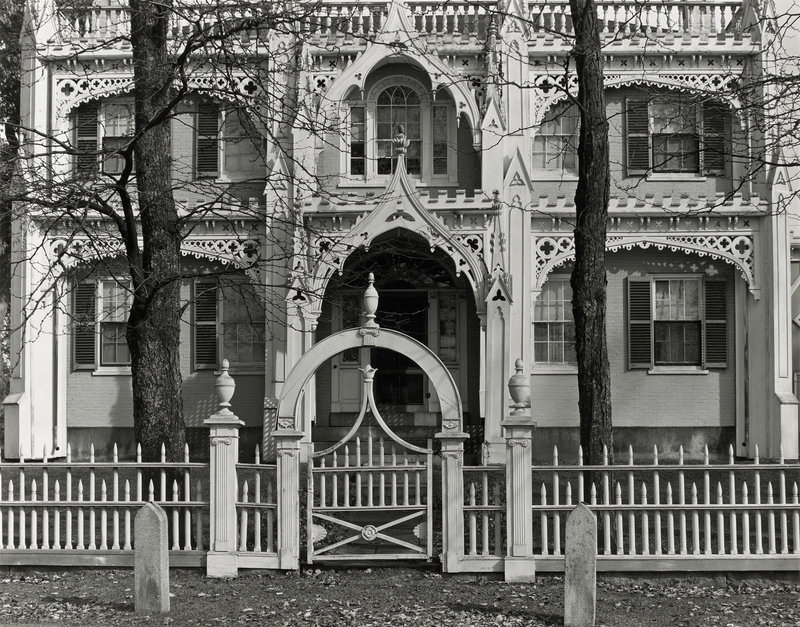

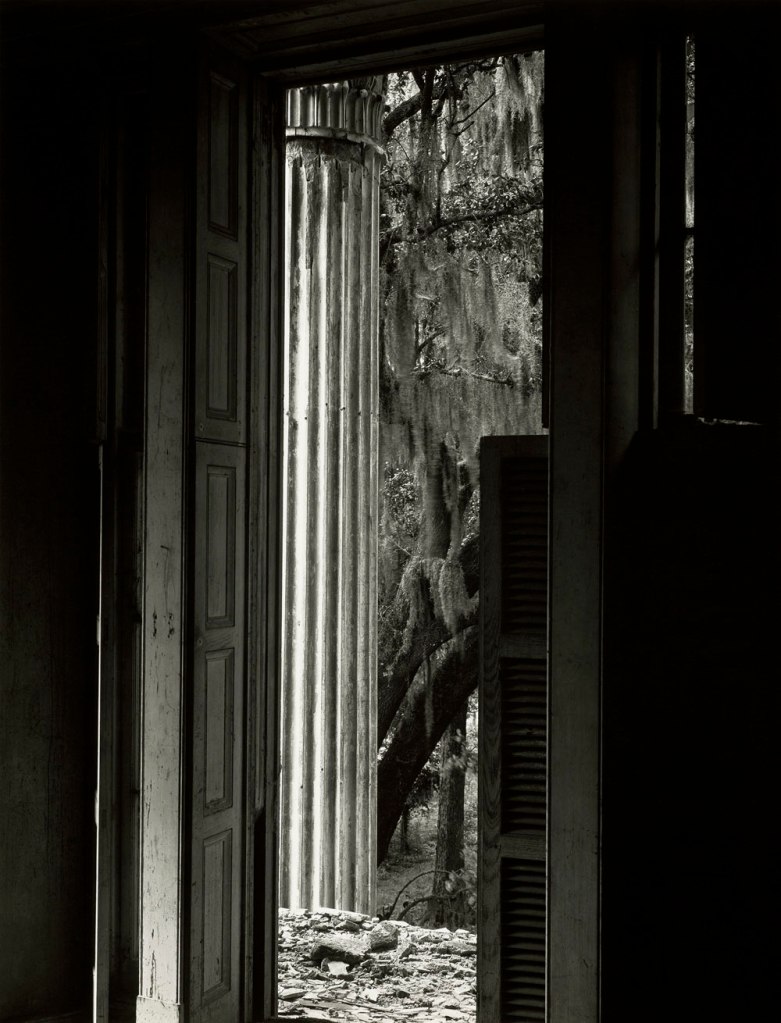

Printed on Agfa’s luscious Portriga Rapid, a double-weight, fibre-based gelatin silver paper which has a warm (brown) colouration for the shadow areas and lovely soft cream highlights, the prints in the exhibition are over six-feet high. The presence of Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980 – freckles highlighted by the light, folds of skin under the armpit – and Boyd Fortin, thirteen-year-old, Sweetwater, Texas, March 10, 1979 – visceral innards of the rattlesnake and the look in his eyes – are simply stunning. Both are beautiful prints. In the American West has often been criticised for its voyeuristic themes, for exploiting its subjects and for evoking condescending emotions from the audience such as pity while studying the portraits, but these magnificent photographs are not about that: they are about the exchange of trust between the photographer and a human being, about the dignity of that portrayal, and about the revelation of a “true-self” as much as possible through a photograph – the face of the sitter mirroring the face of the photographer.

While it is fantastic to see these images in Victoria, the first time any Avedon photographs have been seen in this state (well done The Ian Potter Museum of Art!), the exhibition could have been so much more if it had only been more focused on a particular outcome, instead of a patchy, broad brush approach in which everything has been included. I would have been SO happy to see the whole exhibition devoted to Avendon’s most notable and influential work (think Thomas Ruff portraits) – In the American West. The exhibition climaxes (if you like) with three huge, mural-scale portraits of Merce Cunningham (1993, printed 2002), Doon Arbus, writer, New York, 2002 and Harold Bloom, literary critic, New York City, October 28, 2001 (printed 202), big-statement art that enlarges Avedon’s work to sit alongside other sizeable contemporary art works. Spanning floor to ceiling in the gallery space these overblown edifices, Avedon’s reaction to the ever expanding size of postmodern ‘gigantic’ photography, fall as flat as a tack. At this scale the images simply do not work. As Robert Nelson insightfully observes, “To turn Avedon’s portraiture into contemporary art is technically and commercially understandable, but from an artistic point of view, the conflation of familiarity to bombast seems to be faking it one time to many.”5

Finally we have to ask what do artists Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Robert Mapplethorpe and Richard Avedon have in common? Well, they were all based in New York; they are all white, middle class, and reasonably affluent; they were either gay, Jewish or Catholic or a mixture of each; they all liked mixing with celebrities and fashion gurus; and they all have foundations set up in their honour. Only in New York. It seems a strange state of affairs to set up a foundation as an artist, purely to promote, sustain, expand, and protect the legacy and control of your art after you are gone. This is the ultimate in control, about controlling the image of the artist from the afterlife.

Foundations such as the Keith Haring Foundation do good work, undertaking outreach and philanthropic programs, making “grants to not-for-profit groups that engage in charitable and educational activities. In accordance with Keith’s wishes, the Foundation concentrates its giving in two areas: The support of organisations which provide educational opportunities to underprivileged children and the support of organisations which engage in education, prevention and care with respect to AIDS and HIV infection.”6 I asked the representative of The Richard Avedon Foundation what charitable or philanthropic work they did. They offer an internship program. That’s it. For an artist so obsessed with image and surfaces, for an artist that eventually found his way to a deeper level of understanding, it’s about time The Richard Avedon Foundation offered more back to the community than just an internship. Promotion and narcissism are one thing, engagement and openness entirely another.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 2,335

Footnotes

1/ Robert Nelson. “Pin sharp portraits show us real life,” in The Age newspaper, Friday January 2, 2014, p. 22.

2/ Andrew Stephens. “Fame and falsehoods,” in Spectrum, The Age newspaper, Saturday November 29, 2014, p. 12.

3/ Anon. “Richard Avedon,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 01/03/2015

4/ Whitney, Helen. “Richard Avedon: Darkness and Light.” American Masters, Season 10, Episode 3, 1996 quoted in Anon. “Richard Avedon,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 01/03/2015.

5/ Robert Nelson op cit.,

6/ Anon. “About” on The Keith Haring Foundation website [Online] Cited 01/03/2015

.

Many thankx to The Ian Potter Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. All installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan and The Ian Potter Museum of Art. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

American photographer Richard Avedon (1923-2004) produced portrait photographs that defined the twentieth century. Richard Avedon People explores his iconic portrait making practice, which was distinctive for its honesty, candour and frankness.

One of the world’s great photographers, Avedon is best known for transforming fashion photography from the late 1940s onwards. The full breadth of Avedon’s renowned work is revealed in this stunning exhibition of 80 black and white photographs dating from 1949 to 2002. Avedon’s instantly recognisable iconic portraits of artists, celebrities, and countercultural leaders feature alongside his less familiar portraiture works that capture ordinary New Yorkers going about their daily lives, and the people of America’s West. With uncompromising rawness and tenderness, Avedon’s photographs capture the character of individuals extraordinary in their uniqueness and united in their shared experience of humanity.

Richard Avedon People pays close attention to the dynamic relationship between the photographer and his sitters and focuses on Avedon’s portraits across social strata, particularly his interest in counter-culture. At the core of his artistic work was a profound concern with the emotional and social freedom of the individual in society. The exhibition reveals Avedon’s sensitivity of observation, empathy of identification and clear vision that characterise these portraits.

Text from The Ian Potter Museum of Art website

“There is no truth in photography. There is no truth about anyone’s person.”

“There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is truth.”

“Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me. My concern is… the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may simply be my own.”

.

Richard Avedon

Installation photographs of the exhibition Richard Avedon People at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, Melbourne, February 2015

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

“Photography has had its place in the pas de deux between humanism and anti-humanism, of course, and with two complementary qualities of its own. In the main, we have thought for a long time now, it is photography’s capacity for technological reproduction that defines its greater meaning, both by indexing the world and through its expanded and accelerated means of semiosis. This emphasis on the proliferation of signs and indices has been part of our posthumanism, and it has turned us away consistently from readings that emphasise photography’s second, humanist quality, its capacity to produce recognition through the power of judgment and thus realise the experience of solidarity or common cause.

In keeping with the framing for this collection of writings, we might call the first of these two qualities photography’s ‘either / and’ impulse and the second its ‘either / or’. Where the first impulse draws its structuring ideal from deferring the moment of judgment as it moves laterally from one iteration to the next, one photograph to the next, the second develops its philosophical ground by seeing more than meets the eye in any given photograph or image as the basis of judgment. For example, this is how Kierkegaard described the experience of a ‘shadowgraph’ (or ‘an inward picture which does not become perceptible until I see it through the external’) in his Either/Or:

Sometimes when you have scrutinised a face long and persistently, you seem to discover a second face hidden behind the one you see. This is generally an unmistakable sign that this soul harbours an emigrant who has withdrawn from the world in order to watch over secret treasure, and the path for the investigator is indicated by the fact that one face lies beneath the other, as it were, from which he understands that he must attempt to penetrate within if he wishes to discover anything. The face, which ordinarily is the mirror of the soul, here takes on, though it be but for an instant, an ambiguity that resists artistic production. An exceptional eye is needed to see it, and trained powers of observation to follow this infallible index of a secret grief. … The present is forgotten, the external is broken through, the past is resurrected, grief breathes easily. The sorrowing soul finds relief, and sorrow’s sympathetic knight errant rejoices that he has found the object of his search; for we seek not the present, but sorrow whose nature is to pass by. In the present it manifests itself only for a fleeting instant, like the glimpse one may have of a man turning a corner and vanishing from sight. (Either/Or, Volume 1, 171, 173)

.

Roland Barthes was trying to describe a similar experience with his account of the punctum just as Walter Benjamin did with his figure of the angel of history: ‘His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events [in the same way we experience photography’s ‘either / and’ iteration of images], he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet’. As Kierkegaard, Barthes, and Benjamin suggest, the old humanist experience of struggle with the singular experience of on-going failure to realise its hallowed ideals only ever arose in photography or anywhere else fleetingly, but it is all but invisible to us now.”

Søren Kierkegaard. Either/Or, volume I, 1843, 171, 173 quoted in Blake Stimson. “What was Humanism?” on the Either/And website [Online] Cited 01/03/2015

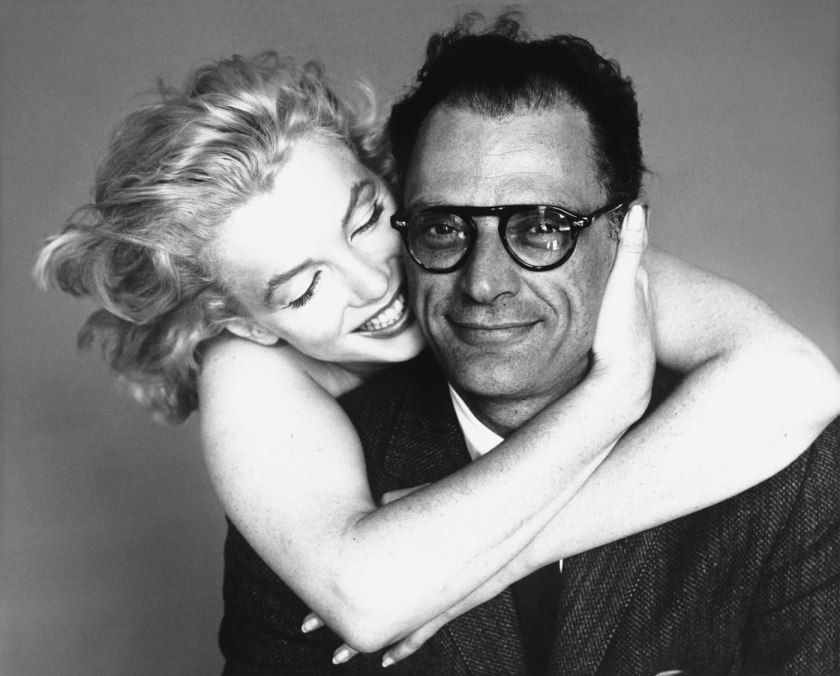

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller, New York, May 8, 1957

1957

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

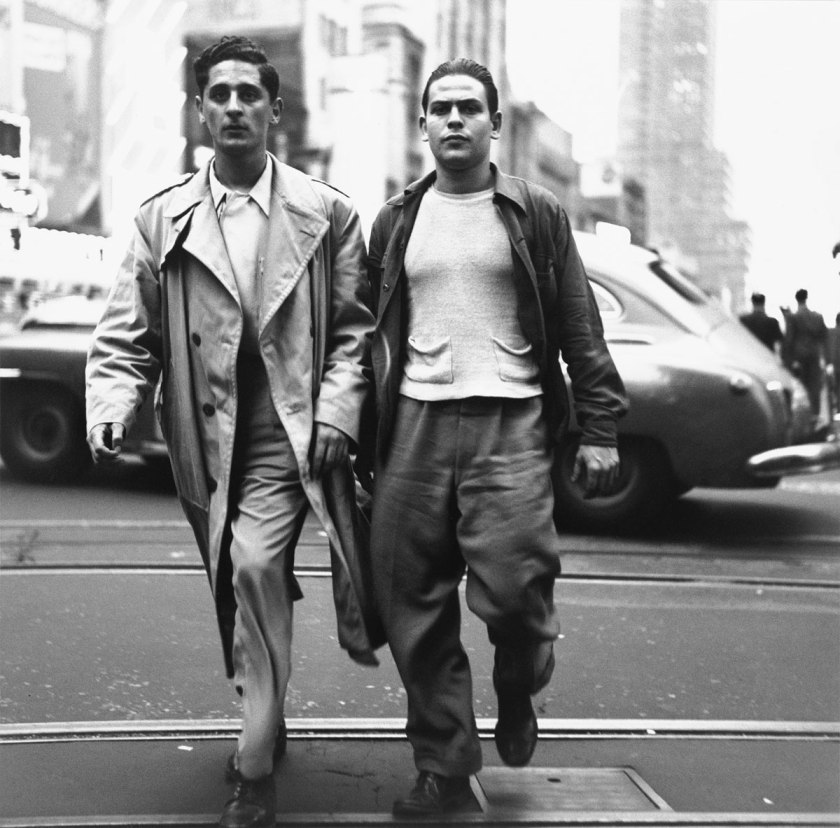

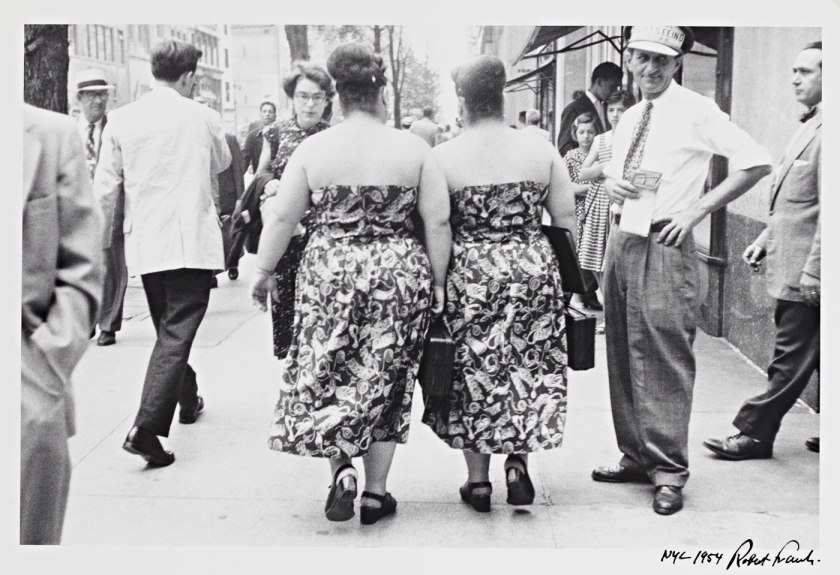

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Mae West, actor, with Mr. America, New York

1954

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

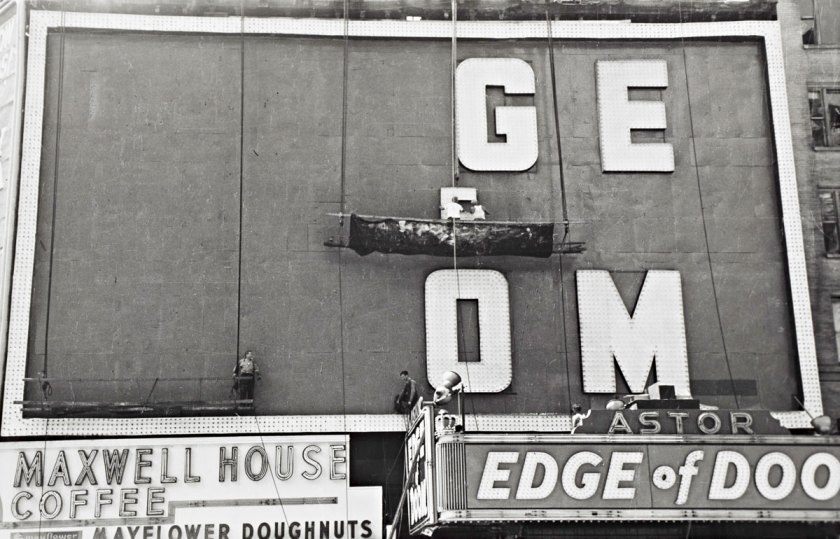

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

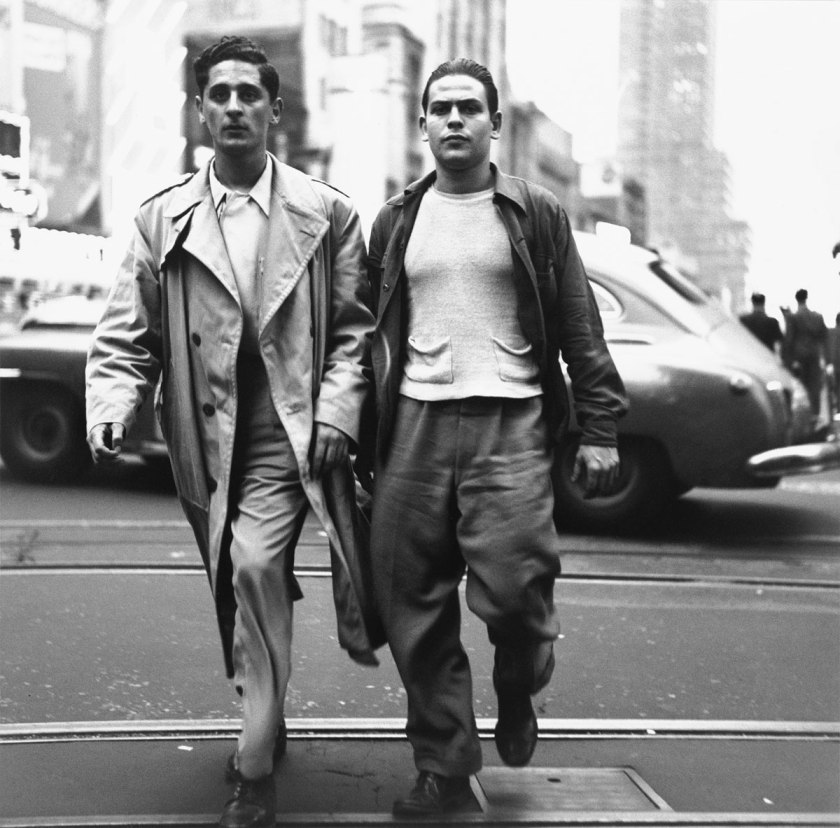

New York Life #5, Lower West Side, New York City, September 9, 1949

1949

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon People celebrates the work of American photographer Richard Avedon (1923 to 2004), renowned for his achievements in the art of black and white portraiture. Avedon’s masterful work in this medium will be revealed in an in-depth overview of 80 photographs from 1949 to 2002, to be displayed at The Ian Potter Museum of Art, University of Melbourne from 6 December 2014 to 15 March 2015.

Known for his exquisitely simple compositions, Avedon’s images express the essence of his subjects in charming and disarming ways. His work is also a catalogue of the who’s who of twentieth-century American culture. In the show, instantly recognisable and influential artists, celebrities, and countercultural leaders including Bob Dylan, Truman Capote, Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Malcolm X, are presented alongside portraits of the unknown. Always accessible, they convey his profound concern with the emotional and social freedom of the individual.

Ian Potter Museum of Art Director, Kelly Gellatly said, “Richard Avedon was one of the world’s great photographers. He is known for transforming fashion photography from the late 1940s onwards, and his revealing portraits of celebrities, artists and political identities.

“People may be less familiar, however, with his portraiture works that capture ordinary New Yorkers going about their daily lives, and the people of America’s West,” Gellatly continued. “Richard Avedon People brings these lesser-known yet compelling portraits together with his always captivating iconic images. In doing so, the exhibition provides a rounded and truly inspiring insight into Avedon’s extraordinary practice.”

Avedon changed the face of fashion photography through his exploration of motion and emotion. From the outset, he was fascinated by photography’s capacity for suggesting the personality and evoking the life of his subjects. This is evidenced across the works in the exhibition, which span Avedon’s career from his influential fashion photography and minimalist portraiture of well-known identities, to his depictions of America’s working class.

Avedon’s practice entered the public imagination through his long association with seminal American publications. He commenced his career photographing for Harper’s Bazaar, followed by a 20-year partnership with Vogue. Later, he established strong collaborations with Egoiste and The New Yorker, becoming staff photographer for The New Yorker in 1992.

Richard Avedon People is the first solo exhibition of Avedon’s work to be displayed in Victoria following showings in Perth and Canberra. The exhibition was curated by the National Portrait Gallery’s Senior Curator, Dr Christopher Chapman, in partnership with the Richard Avedon Foundation over the course of two years. The Foundation was established by Avedon in his lifetime and encourages the study and appreciation of the artist’s photography through exhibitions, publications and outreach programs.

Dr Christopher Chapman

Dr Christopher Chapman is Senior Curator at the National Portrait Gallery where he has produced major exhibitions exploring diverse experiences of selfhood and identity. He joined the Gallery in 2008 and was promoted to Senior Curator in 2011. He works closely with the Gallery’s management team to drive collection and exhibition strategy. Working in the visual arts field since the late 1980s, Christopher has held curatorial roles at the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of South Australia. He has lectured in visual arts and culture for the Australian National University and his PhD thesis examined youth masculinity and themes of self-sacrifice in photography and film.

A National Portrait Gallery of Australia exhibition presented in partnership with the Richard Avedon Foundation, New York.

Press release from The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Bob Dylan, musician, Central Park, New York, February 20, 1965

1965

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver, Paris, August 1955

1955

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Marilyn Monroe, actress, New York, May 6, 1957

1957

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

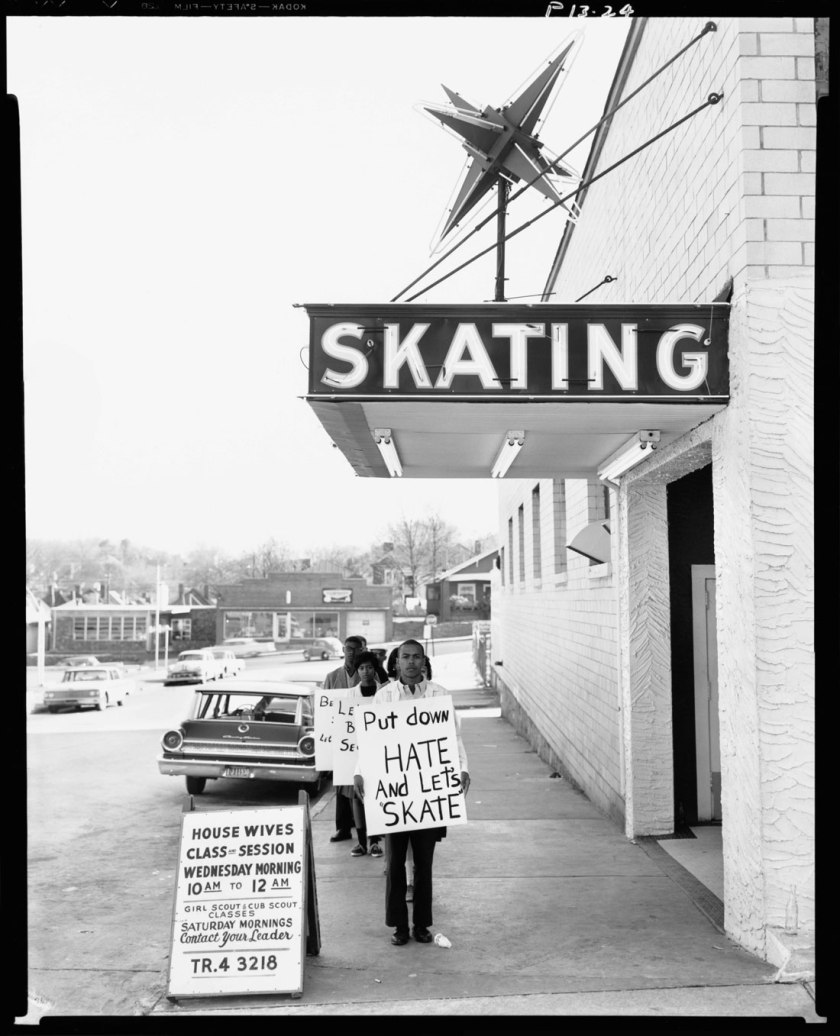

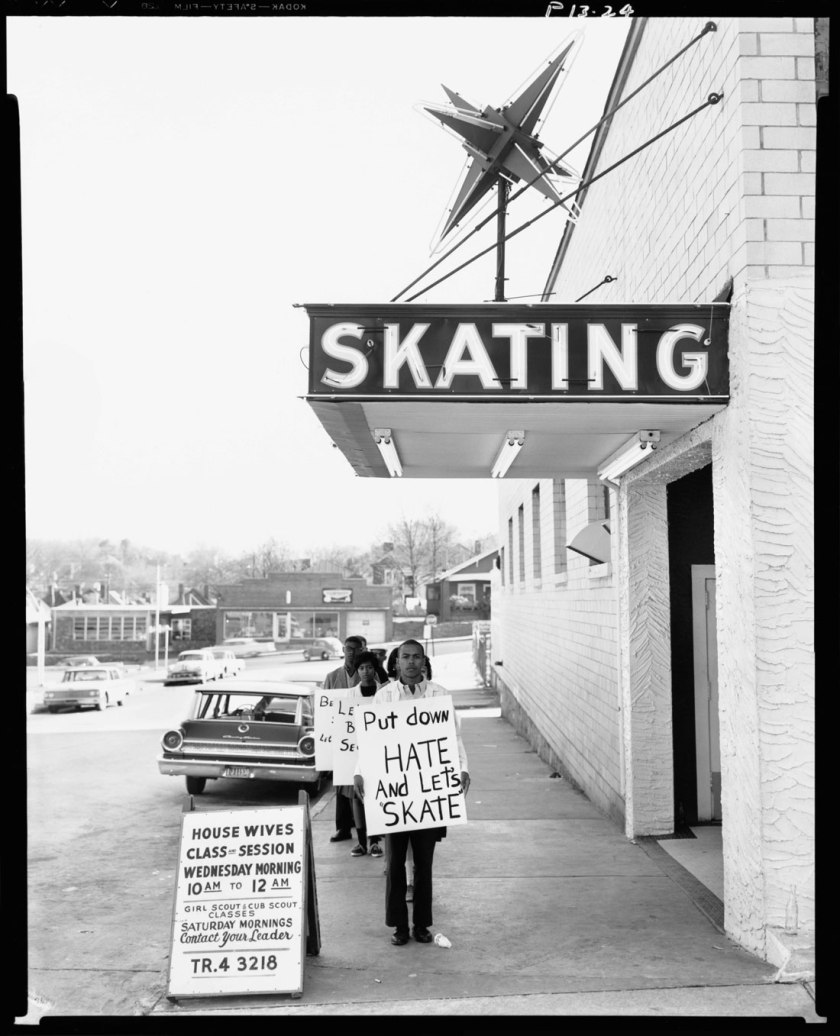

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Civil rights demonstration, Atlanta, Georgia

c. 1963

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Self portrait, New York City, July 23, 1969

1969

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

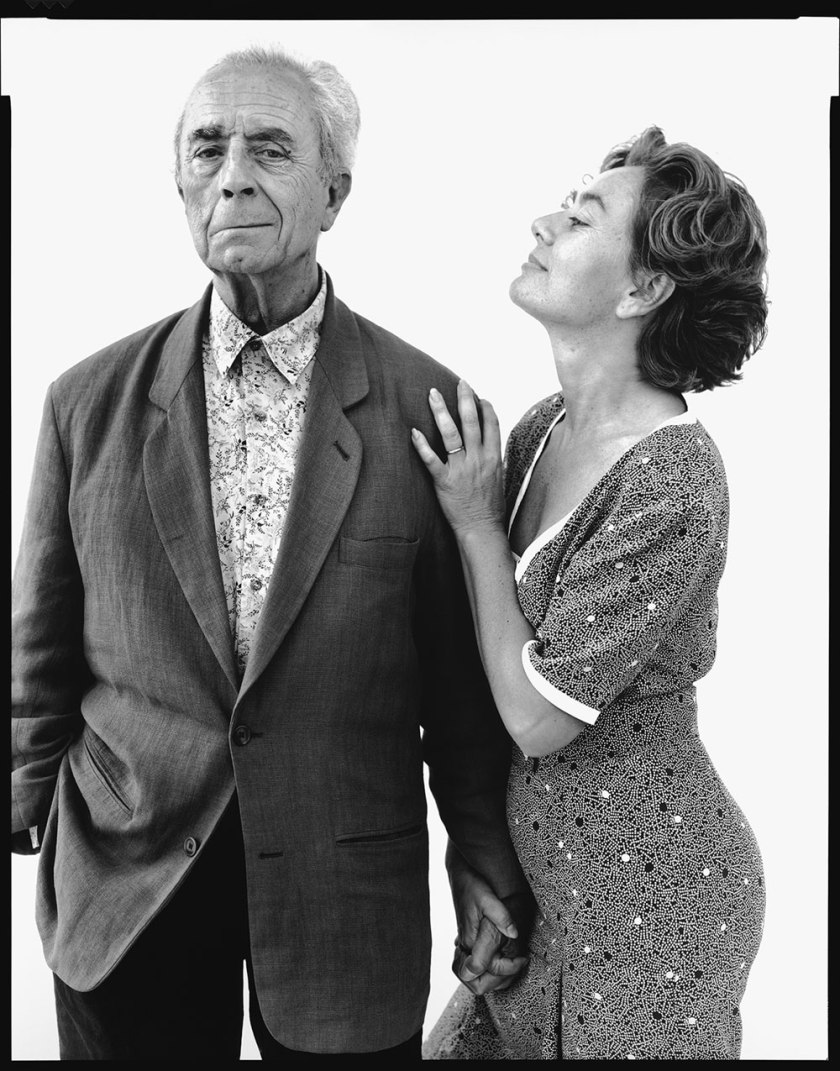

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

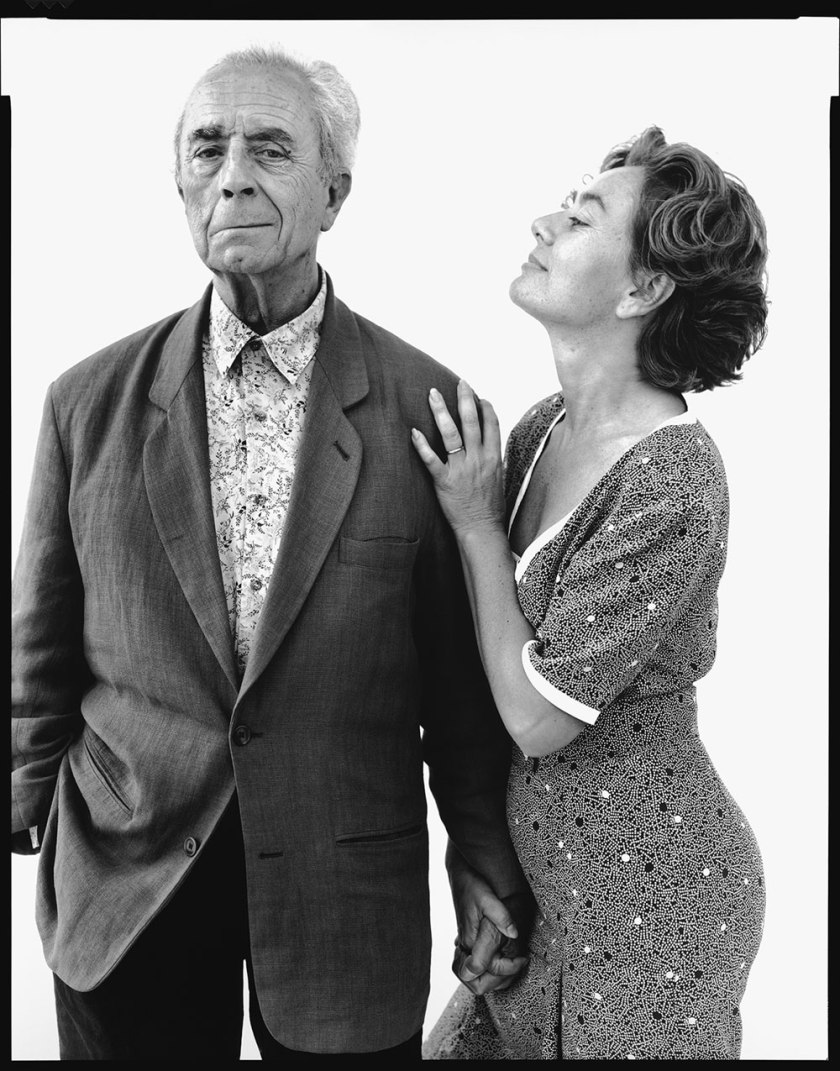

Michelangelo Antonioni, film director, with his wife Enrica, Rome, 1993

1993

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

“Insights into the crossover of genres and the convergence of modern media gave Avedon’s work its extra combustive push. He got fame as someone who projected accents of notoriety and even scandal within a decorous field. By not going too far in exceeding known limits, he attained the highest rank at Vogue. In American popular culture, this was where Avedon mattered, and mattered a lot. But it was not enough.

In fact, Avedon’s increasingly parodistic magazine work often left – or maybe fed – an impression that its author was living beneath his creative means. In the more permanent form of his books, of which there have been five so far, he has visualised another career that would rise above fashion. Here Avedon demonstrates a link between what he hopes is social insight and artistic depth, choosing as a vehicle the straight portrait. Supremacy as a fashion photographer did not grant him status in his enterprise – quite the contrary – but it did provide him access to notable sitters. Their presence before his camera confirmed the mutual attraction of the well-connected.”

Max Kozloff. “Richard Avedon’s “In the American West”,” on the ASX website, January 24, 2011 [Online] Cited 01/03/2015

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Elizabeth Taylor, cock feathers by Anello of Emme, New York, July 1964

1964

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Twiggy, dress by Roberto Rojas, New York, April 1967

1967

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Boyd Fortin, thirteen-year-old, Sweetwater, Texas, March 10, 1979

1979, printed 1984-1985

From the project the Western Project and the book In the American West

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Richard Avedon (American, 1923-2004)

Sandra Bennett, twelve year old, Rocky Ford, Colorado, August 23, 1980

1980, printed 1984-1985

From the project the Western Project and the book In the American West

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

The Ian Potter Museum of Art

Closed for redevelopment

The Ian Potter Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.