Exhibition dates: 22nd October – 10th December 2022

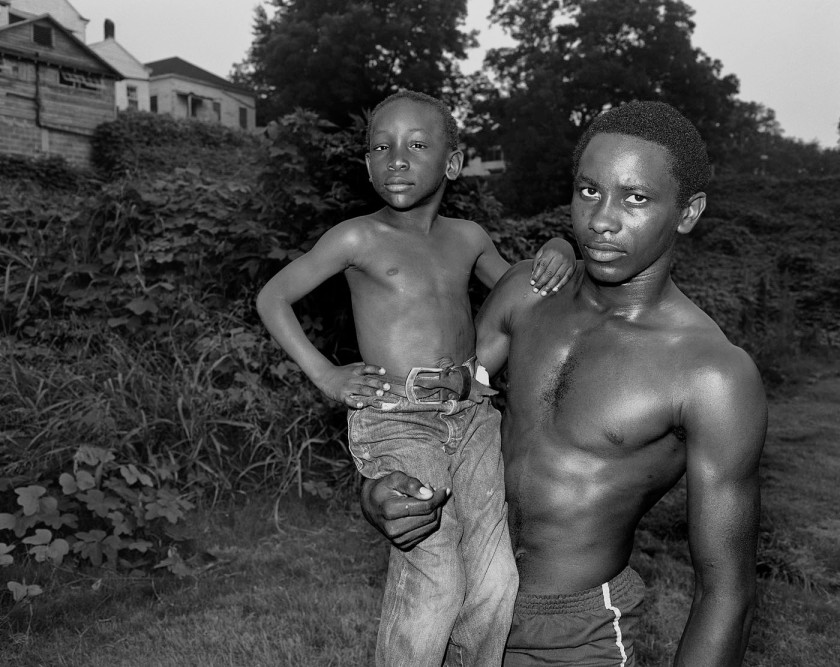

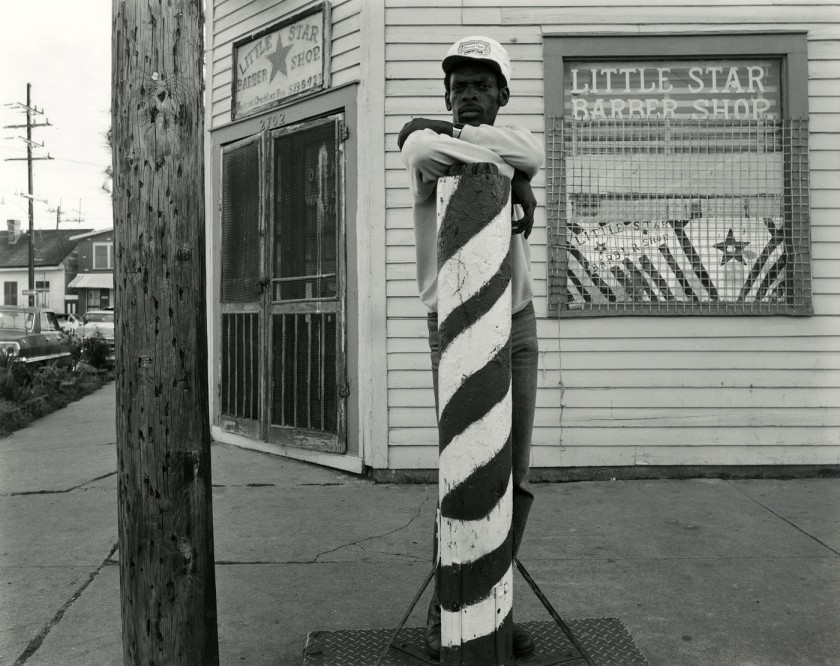

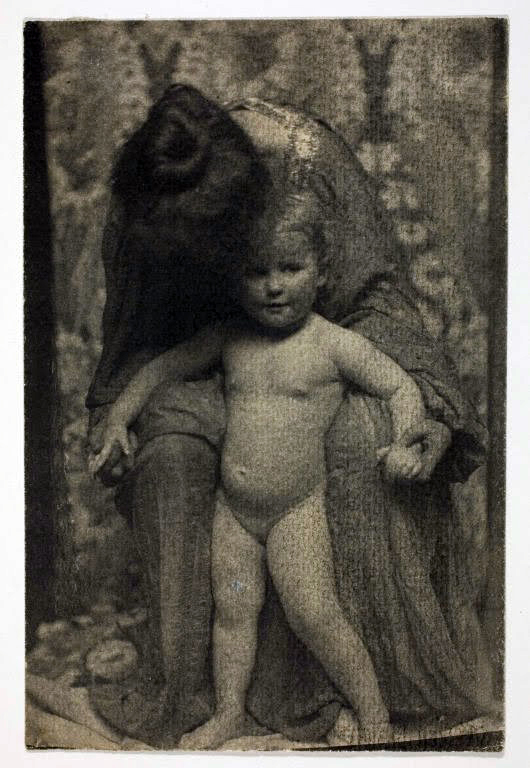

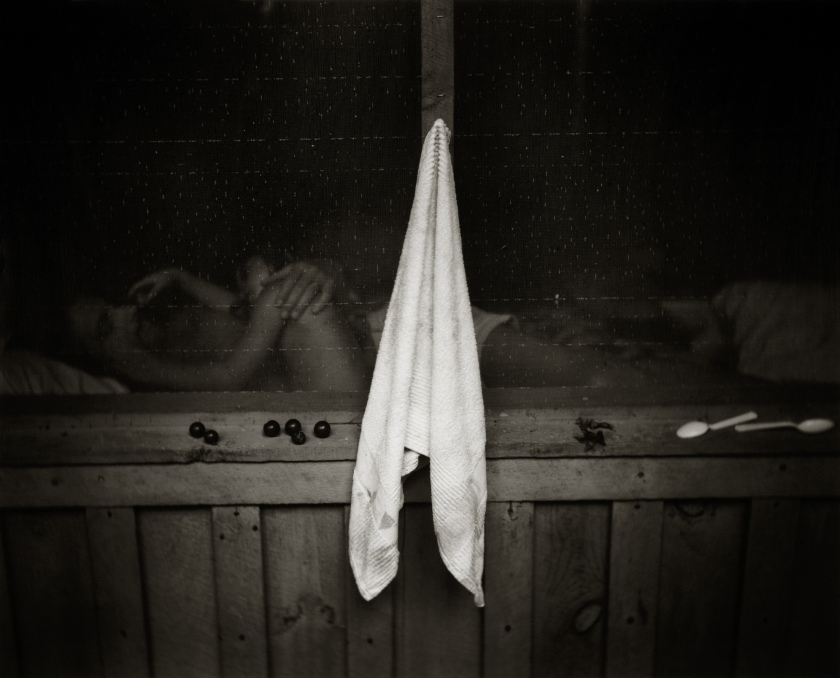

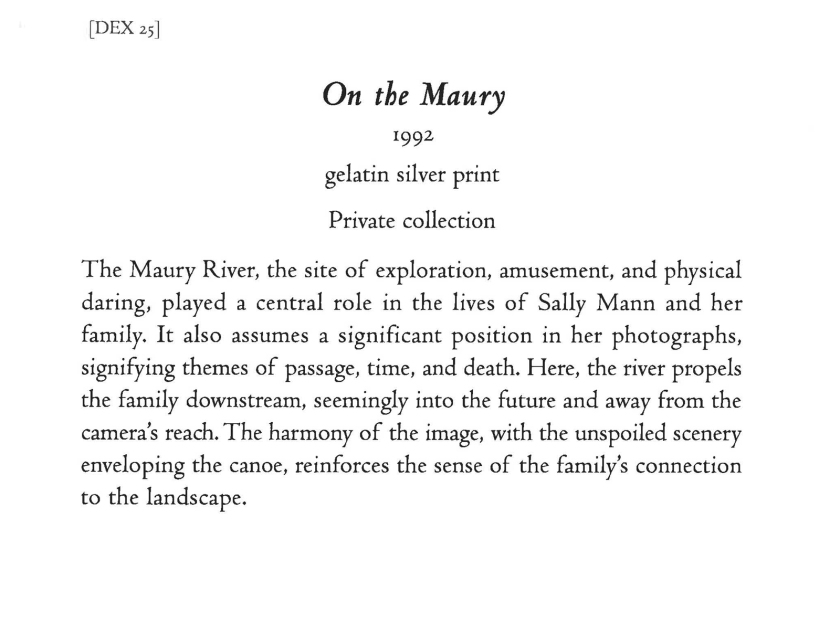

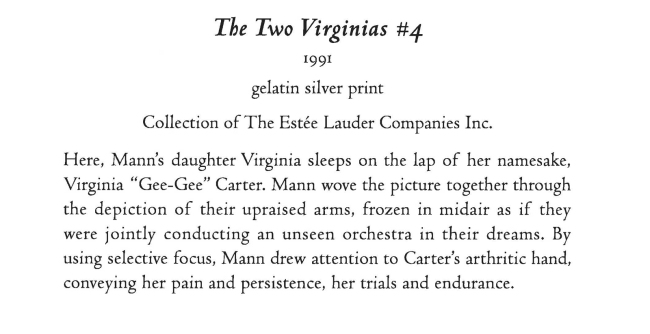

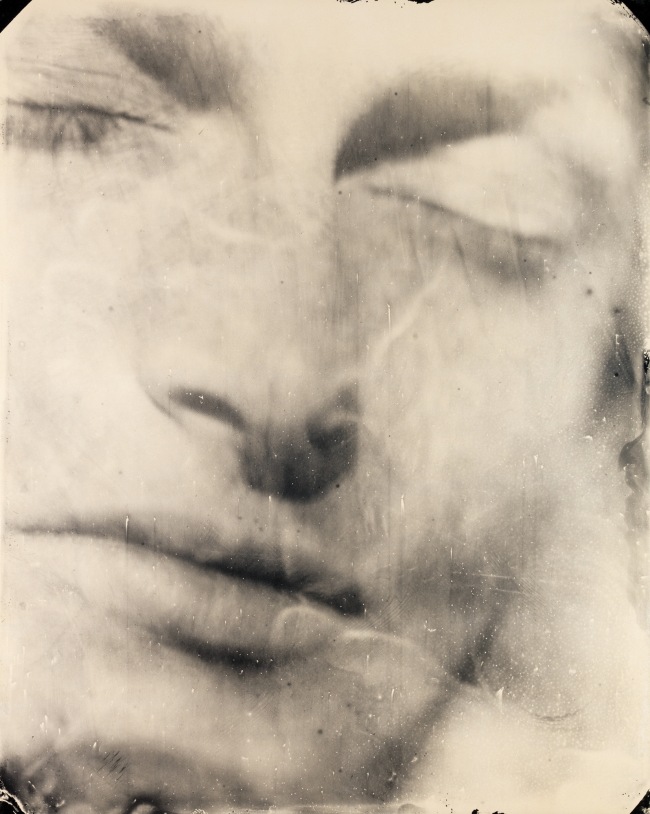

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Vicksburg, Mississippi

1983

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

“The work of two contemporary photographers, Bill Brandt of England and the American, Walker Evans, have influenced me. When I first looked at Walker Evans’ photographs, I thought of something Malraux wrote: “To transform destiny into awareness.” One is embarrassed to want so much for oneself. But, how else are you going to justify your failure and your effort?”

Robert Frank, ‘U.S. Camera Annual’, 1958, p. 115

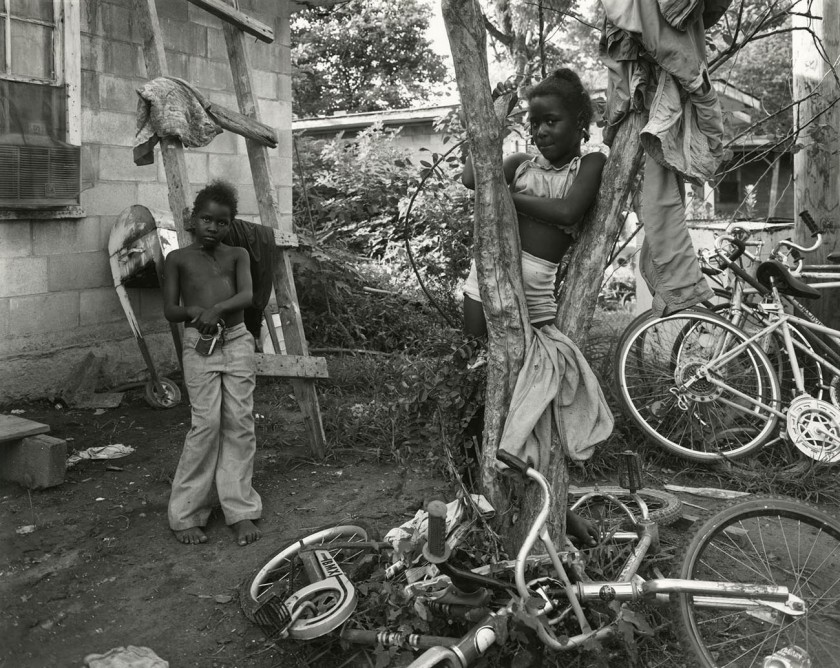

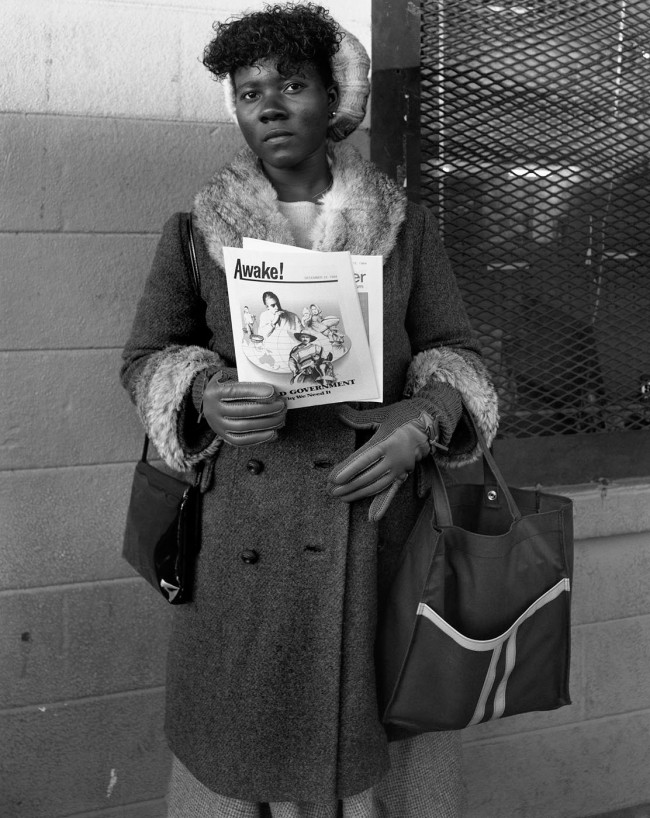

In terms of training as a photographer, Baldwin Lee couldn’t have done much better than study with those two photographic greats, Minor White and Walker Evans. His work is suffused with their glow, especially the influence of Walker Evans. Lee’s works continues that wonderful tradition of documenting with frankness, things that are placed before the lens. In his photographs of “Black Americans: at home, at work, and at play, in the street, and among nature”, Lee responds with understanding and a “a sensitive eye for both poverty and dignity” to the plight of the lower echelons of American society, in work that “exposes the violence of poverty inherited from the plantation-economy past.” And though his photographs he tries to transform the destiny (of a race) into awareness (of their plight).

“In 1983, Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951) left his home in Knoxville, Tennessee, with his 4 × 5 view camera and set out on the first of a series of road trips to photograph the American South.” Lee received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1984, and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in 1984 and 1987 to continue his project until the end of the decade. The resultant photographs show “attentiveness to the composure of his subjects that is echoed masterfully in the composition of his shots” … “Lee’s graceful pictures from this project perfectly balance the photographer’s presence and the subject’s will, honouring both through the resulting, beautifully printed 16 x 20-inch black-and-white photographs.”

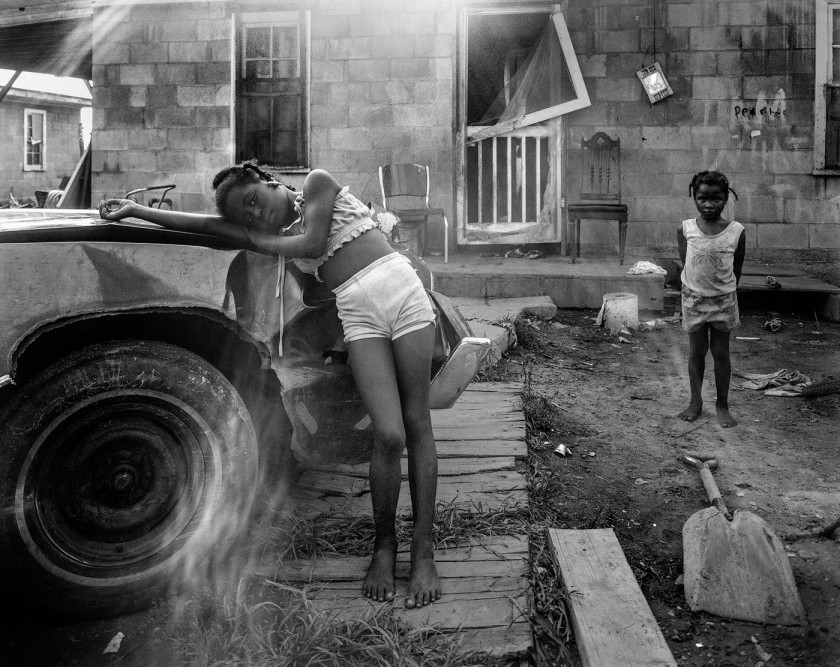

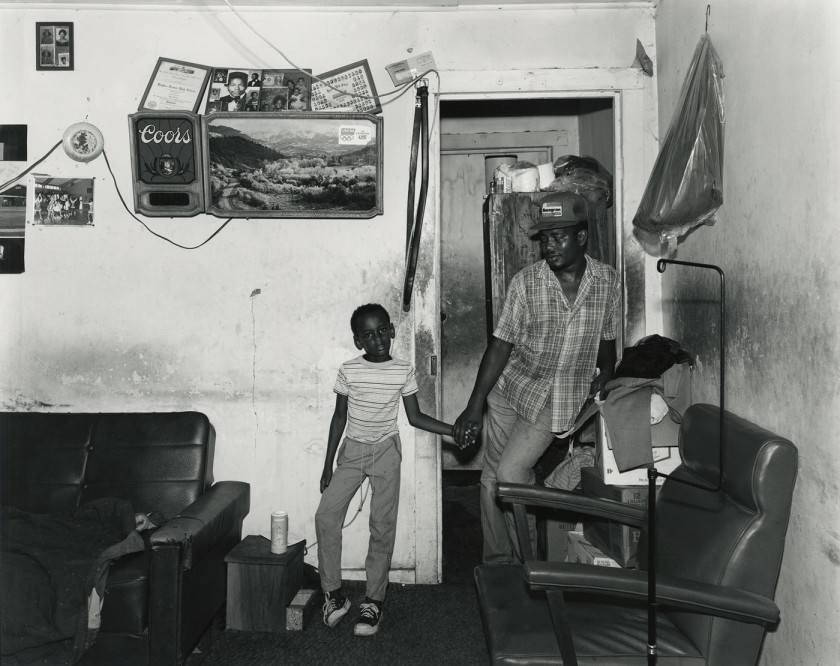

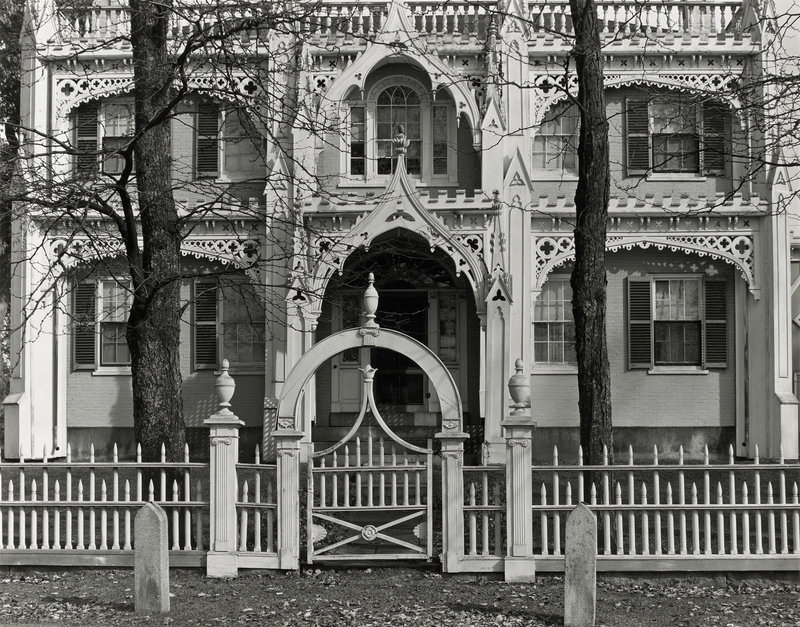

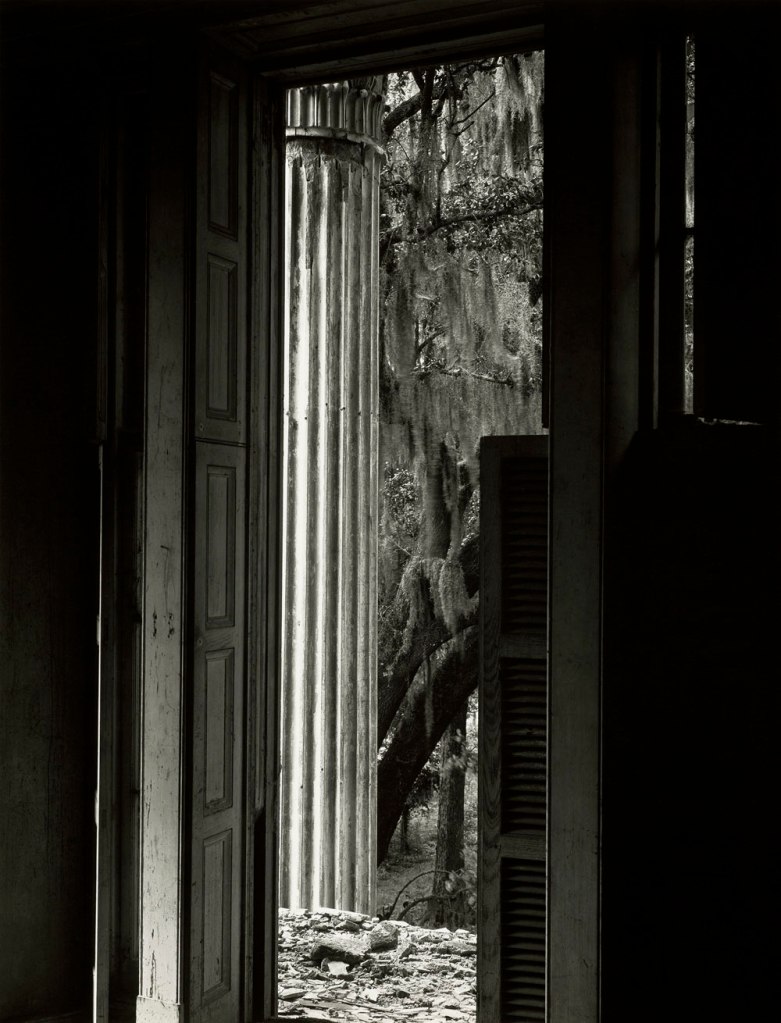

At their best, Lee’s photographs (such as Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1983 above) have an incisive presence which illuminates the human condition through a revelation of spirit, the spirit of a people with the strength to survive and flourish against the forces of tyranny, discrimination and oppression. The proud stare of the child, the placement in of his hands, his large belt buckle, and the attitude of the father make this photograph a masterpiece of observation and composition. Other powerful photographs such as New Orleans, Louisiana (1984, below), Columbia, South Carolina (1984, below), Valdosta, Georgia (1984, below) and Valdosta, Georgia (1986, below) intimately capture the inter-generational strength that courses through generations of survivors – survivors of life, of hardship, of disenfranchisement. And then we must place those portraits in a historical context for their wider import to be understood: Vicksburg, Mississippi and its political and racial unrest after the Civil War; Montgomery, Alabama and the bus boycott that changed a nation; Mobile, Alabama and its race riots during the Second World War and the desegregation of the school system in 1964. And so it still goes…

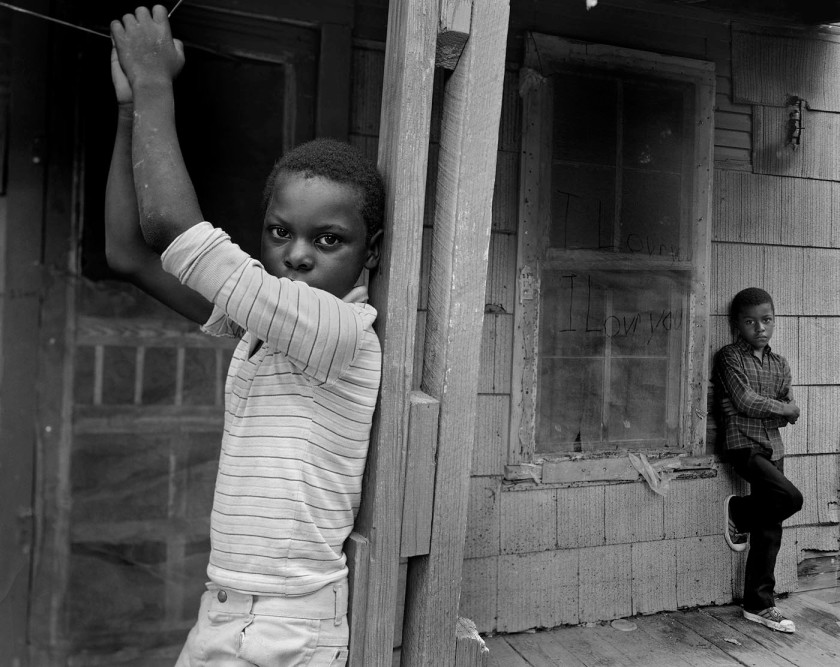

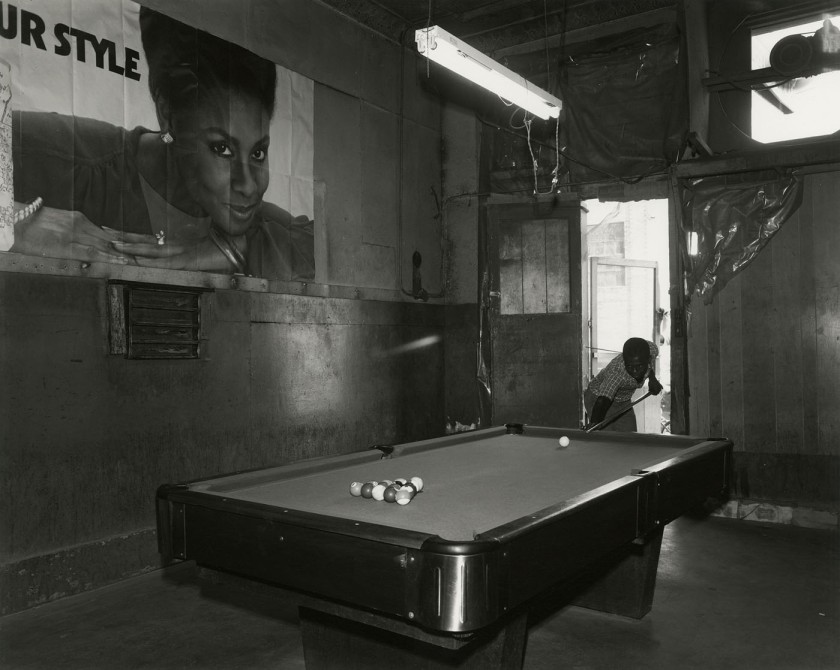

Other photographs, such as Montgomery, Alabama (1984, below), Lula, Mississippi (1984, below), Natchez, Mississippi (1984, below) and Garnett, South Carolina (1985, below) are an extension of the work of Walker Evans. They really have no signature of the individual artist but continue the tradition, the story, of documentary photography in America. In the camera magazines of the mid- 60s to mid- 70s the photographer who was published would also have a small image check-list in the last pages of the magazine with technical information – aperture / developer / paper etc… Instead, for these pages, Minor White would say: “For technical information, the camera was faithfully used.” And one could imagine this artist saying the same thing, for there are no attempts at obfuscation or anything that would alter the intensity of his vision.

Of the remaining photographs in the posting… I have rather ambivalent feelings about them. All of the photographs possess a calmness and quietness to them, have balanced (perhaps too balanced) composition, but some leave me feeling rather cold. It’s almost as if I am looking at a “scene” from reality, rather than reality itself. Much like Edward S. Curtis and his storytelling of the First Nations peoples, that is, the myth that he wanted to tell of a “vanishing race” – some of Lee’s photographs are too staged, to constructed by the photographer that real life gets put in the deep freeze. A good example of this is the photograph Canton, Mississippi (1985, below). Imagine the time it would have taken Lee to set up his large format camera, to check the light, to focus the ground glass, and then to place the figures in such a deliberate arrangement. Did the subjects have a say in how they wanted to be portrayed? With this arrangement, especially the figure at left with her hand in the air, I suspect not… it’s all just so stilted and unmoving, particularly the spacing between the figures. Certainly, in this one particular photograph, the image does not balance photographer’s presence and the subject’s will. It’s a story that the photographer wants to tell in a particular way.

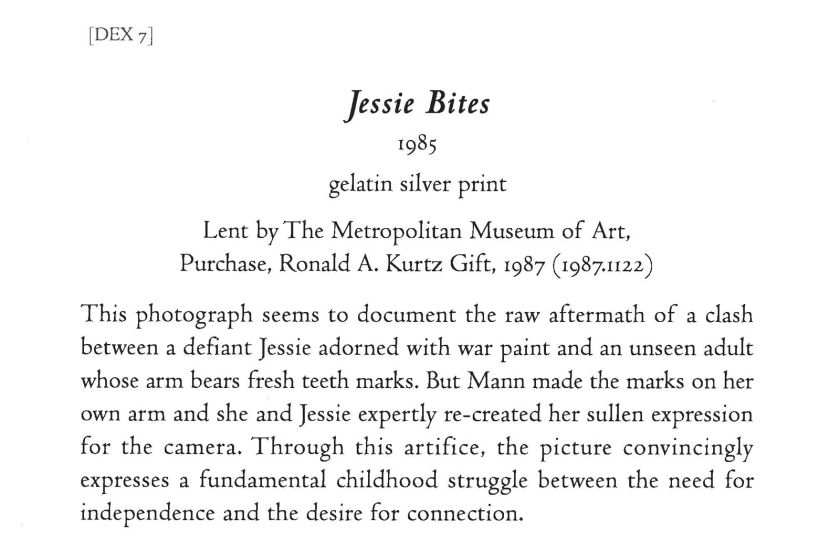

Other photographs teeter either side of this line, between seemingly spontaneous and obviously staged compositions. I don’t believe Vicksburg, Mississippi (1984, below) whereas I do feel Walls, Mississippi (1984, below), mainly because of the too stiff pose of the standing boy in the former and the languid pose and look of the girl in the latter. I believe in the direct stares of the children in Boyle, Mississippi (1985, below) and yet in the photograph below (Columbia, South Carolina 1984, below), that trust is dissolved. It is so difficult with a large format camera to stop the images becoming a facsimile of real life… something that appeals to the direction of the photographer but is a creation of their imagination, not a portrait of the real life of the subjects. In other words, the images do not go into that world with equal drama (usually the feeling is modified by Walker Evans directness), for there is a range of using this “drama” trope.

Here I am not appealing for something close to Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” for that is almost impossible with a large format camera, but rather something more akin to the work of Minor White than that of Walker Evans – more a revelation of spirit rather than a humanist “family of man”. As with any portrait, whether it is in the objective but slightly surreal portraits by August Sander or the dynamic exposures by Diane Arbus, it is the ability of the photographer to reveal the Self behind the mask that creates memorable portraits.

This is why Lee’s photograph Vicksburg, Mississippi 1983 stands head and shoulders above all the other photographs in this posting. The portrait challenges our preconceptions of what is it to live this life, to be Black in America, and with fierce resolve that echoes down through the generations, it says, we will survive and flourish… for we are whole and free.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. Sometimes we say something about an image which is “after the case” of its place in the world. Knowing the boundaries of when this stops and starts is the big challenge…

Many thankx to Joseph Bellows Gallery for allowing me to publish the photograph in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Vicksburg, Mississippi

1983

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

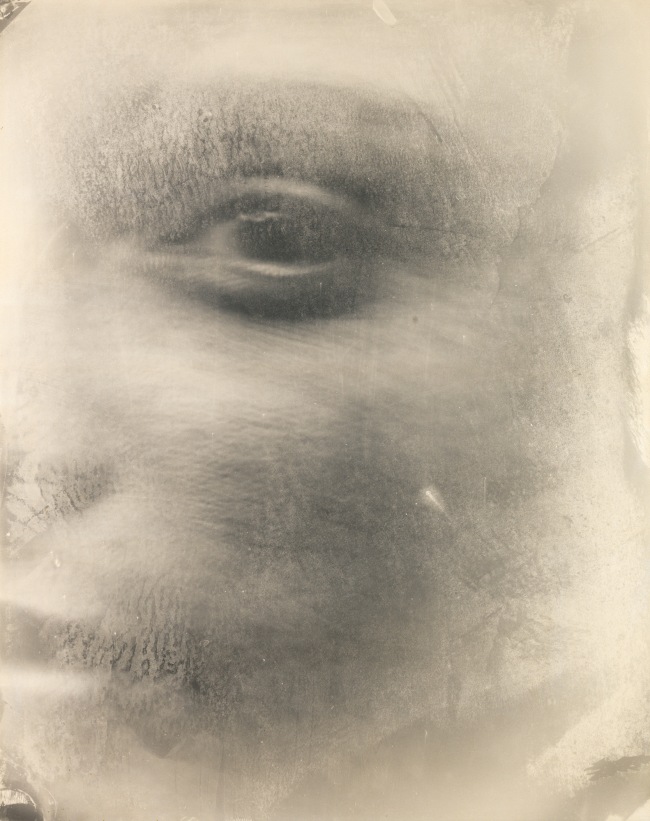

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Vicksburg, Mississippi

1984

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

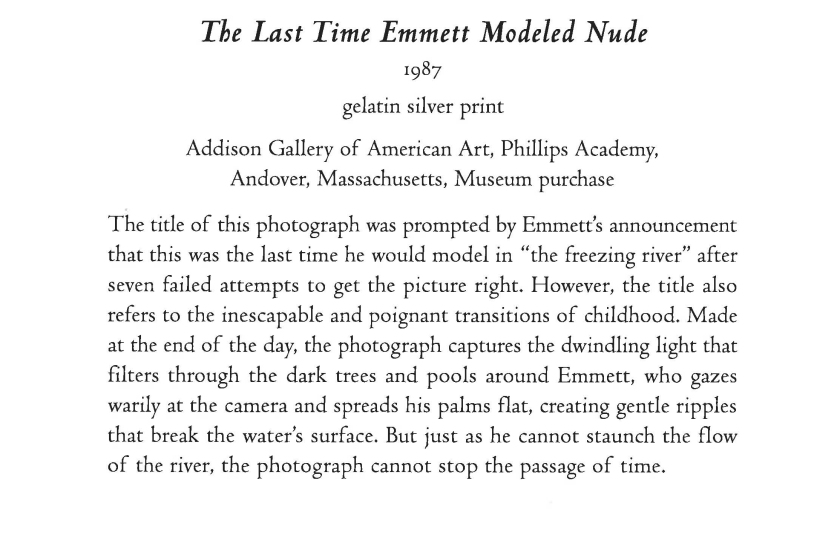

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Vicksburg, Mississippi

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

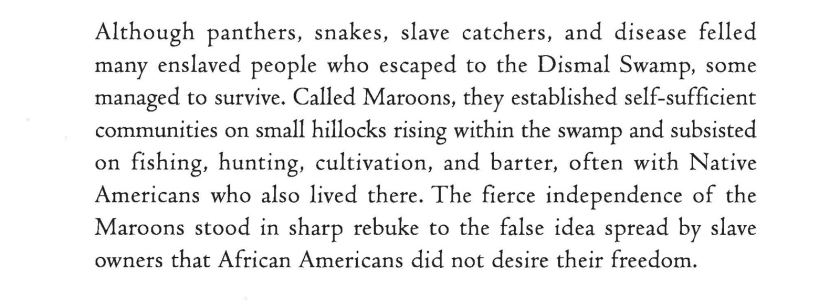

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Civil War

During the American Civil War, the city finally surrendered during the Siege of Vicksburg, after which the Union Army gained control of the entire Mississippi River. The 47-day siege was intended to starve the city into submission. Its location atop a high bluff overlooking the Mississippi River proved otherwise impregnable to assault by federal troops. The surrender of Vicksburg by Confederate General John C. Pemberton on July 4, 1863, together with the defeat of General Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg the day before, has historically marked the turning point of the Civil War in the Union’s favour.

From the surrender of Vicksburg until the end of the war in 1865, the area was under Union military occupation. The Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, was based at his family plantation at Brierfield, just south of the city.

Political and racial unrest after Civil War

In the first few years after the Civil War, white Confederate veterans developed the Ku Klux Klan, beginning in Tennessee; it had chapters throughout the South and attacked freedmen and their supporters. It was suppressed about 1870. By the mid-1870s, new white paramilitary groups had arisen in the Deep South, including the Red Shirts [white supremacist paramilitary terrorist groups that were active in the late 19th century] in Mississippi, as whites struggled to regain political and social power over the black majority. Elections were marked by violence and fraud as white Democrats worked to suppress black Republican voting.

In August 1874, a black sheriff, Peter Crosby, was elected in Vicksburg. Letters by a white planter, Batchelor, detail the preparations of whites for what he described as a “race war,” including acquisition of the newest guns, Winchester 16 mm. On December 7, 1874, white men disrupted a black Republican meeting celebrating Crosby’s victory and held him in custody before running him out of town. He advised blacks from rural areas to return home; along the way, some were attacked by armed whites. During the next several days, armed white mobs swept through black areas, killing other men at home or out in the fields. Sources differ as to total fatalities, with 29-50 blacks and 2 whites reported dead at the time. Twenty-first-century historian Emilye Crosby estimates that 300 blacks were killed in the city and the surrounding area of Claiborne County, Mississippi. The Red Shirts were active in Vicksburg and other Mississippi areas, and black pleas to the federal government for protection were not met.

At the request of Republican Governor Adelbert Ames, who had left the state during the violence, President Ulysses S. Grant sent federal troops to Vicksburg in January 1875. In addition, a congressional committee investigated what was called the “Vicksburg Riot” at the time (and reported as the “Vicksburg Massacre” by northern newspapers.) They took testimony from both black and white residents, as reported by the New York Times, but no one was ever prosecuted for the deaths. The Red Shirts and other white insurgents suppressed Republican voting by both whites and blacks; smaller-scale riots were staged in the state up to the 1875 elections, at which time white Democrats regained control of a majority of seats in the state legislature.

Under new constitutions, amendments and laws passed between 1890 in Mississippi and 1908 in the remaining southern states, white Democrats disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites by creating barriers to voter registration, such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses. They passed laws imposing Jim Crow [laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States] and racial segregation of public facilities.

20th century to present

The exclusion of most blacks from the political system lasted for decades until after Congressional passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s. Lynchings of blacks and other forms of white racial terrorism against them continued to occur in Vicksburg after the start of the 20th century. In May 1903, for instance, two black men charged with murdering a planter were taken from jail by a mob of 200 farmers and lynched before they could go to trial. In May 1919, as many as a thousand white men broke down three sets of steel doors to abduct, hang, burn and shoot a black prisoner, Lloyd Clay, who was falsely accused of raping a white woman. From 1877 to 1950 in Warren County, 14 African Americans were lynched by whites, most in the decades near the turn of the century…

Particularly after World War II, in which many blacks served, returning veterans began to be active in the civil rights movement, wanting to have full citizenship after fighting in the war. In Mississippi, activists in the Vicksburg Movement became prominent during the 1960s.

Text from the Wikipedia website

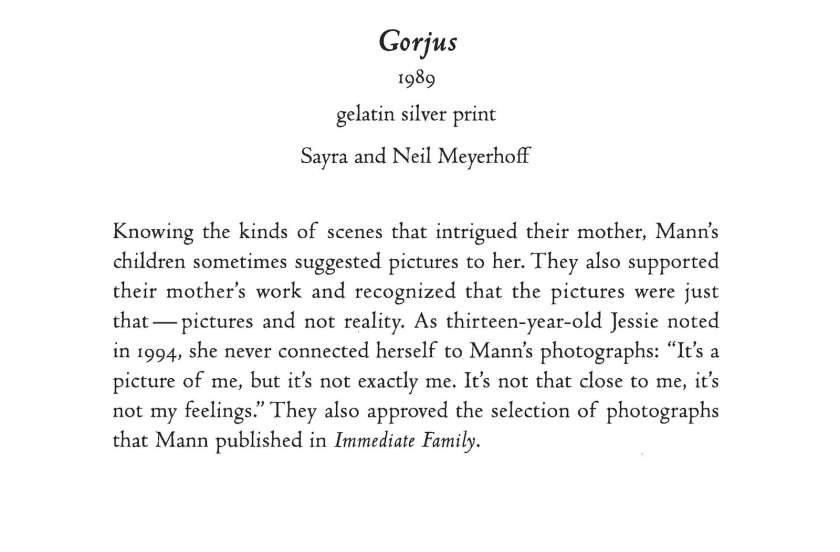

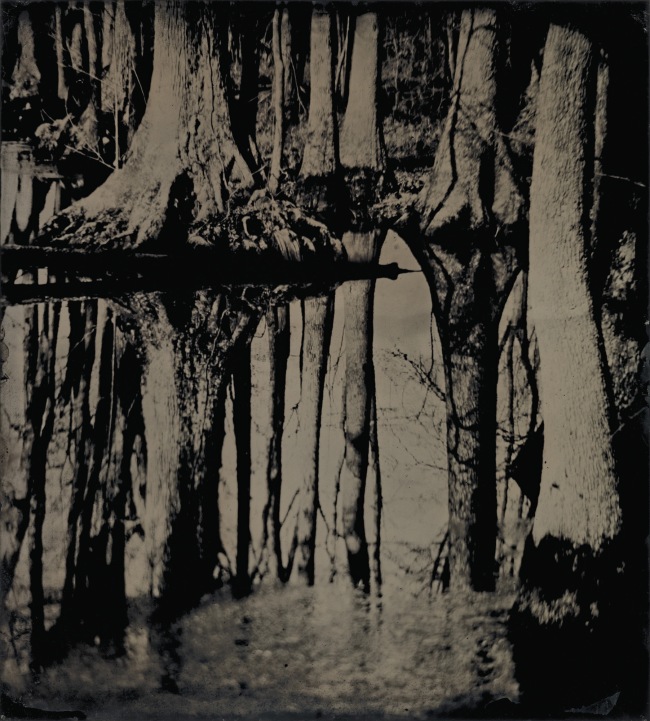

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Montgomery, Alabama

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Montgomery, Alabama

In the post-World War II era, returning African-American veterans were among those who became active in pushing to regain their civil rights in the South: to be allowed to vote and participate in politics, to freely use public places, to end segregation. According to the historian David Beito of the University of Alabama, African Americans in Montgomery “nurtured the modern civil rights movement.” African Americans comprised most of the customers on the city buses, but were forced to give up seats and even stand in order to make room for whites. On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her bus seat to a white man, sparking the Montgomery bus boycott. Martin Luther King Jr., then the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, and E.D. Nixon, a local civil rights advocate, founded the Montgomery Improvement Association to organise the boycott. In June 1956, the US District Court Judge Frank M. Johnson ruled that Montgomery’s bus racial segregation was unconstitutional. After the US Supreme Court upheld the ruling in November, the city desegregated the bus system, and the boycott was ended.

In separate action, integrated teams of Freedom Riders rode South on interstate buses. In violation of federal law and the constitution, bus companies had for decades acceded to state laws and required passengers to occupy segregated seating in Southern states. Opponents of the push for integration organised mob violence at stops along the Freedom Ride. In Montgomery, there was police collaboration when a white mob attacked Freedom Riders at the Greyhound Bus Station in May 1961. Outraged national reaction resulted in the enforcement of desegregation of interstate public transportation.

Martin Luther King Jr. returned to Montgomery in 1965. Local civil rights leaders in Selma had been protesting Jim Crow laws and practices that raised barriers to blacks registering to vote. Following the shooting of a man after a civil rights rally, the leaders decided to march to Montgomery to petition Governor George Wallace to allow free voter registration. The violence they encountered from county and state highway police outraged the country. The federal government ordered National Guard and troops to protect the marchers. Thousands more joined the marchers on the way to Montgomery, and an estimated 25,000 marchers entered the capital to press for voting rights. These actions contributed to Congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, to authorise federal supervision and enforcement of the rights of African Americans and other minorities to vote.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States. The campaign lasted from December 5, 1955 – the Monday after Rosa Parks, an African-American woman, was arrested for her refusal to surrender her seat to a white person – to December 20, 1956, when the federal ruling Browder v. Gayle took effect, and led to a United States Supreme Court decision that declared the Alabama and Montgomery laws that segregated buses were unconstitutional. …

Background

Before the bus boycott, Jim Crow laws mandated the racial segregation of the Montgomery Bus Line. As a result of this segregation, African Americans were not hired as drivers, were forced to ride in the back of the bus, and were frequently ordered to surrender their seats to white people even though black passengers made up 75% of the bus system’s riders. Many bus drivers treated their black passengers poorly beyond the law: African-Americans were assaulted, shortchanged, and left stranded after paying their fares.

The year before the bus boycott began, the Supreme Court decided unanimously, in the case of Brown v. Board of Education, that racial segregation in schools was unconstitutional. The reaction by the white population of the Deep South was “noisy and stubborn”. Many white bus drivers joined the White Citizens’ Council as a result of the decision.

Although it is often framed as the start of the civil rights movement, the boycott occurred at the end of many black communities’ struggles in the South to protect black women, such as Recy Taylor, from racial violence. The boycott also took place within a larger statewide and national movement for civil rights, including court cases such as Morgan v. Virginia, the earlier Baton Rouge bus boycott, and the arrest of Claudette Colvin for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. …

History

Under the system of segregation used on Montgomery buses, the ten front seats were reserved for white people at all times. The ten back seats were supposed to be reserved for black people at all times. The middle section of the bus consisted of sixteen unreserved seats for white and black people on a segregated basis.[22] White people filled the middle seats from the front to back, and black people filled seats from the back to front until the bus was full. If other black people boarded the bus, they were required to stand. If another white person boarded the bus, then everyone in the black row nearest the front had to get up and stand so that a new row for white people could be created; it was illegal for white and black people to sit next to each other. When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat for a white person, she was sitting in the first row of the middle section.

Often when boarding the buses, black people were required to pay at the front, get off, and reenter the bus through a separate door at the back. Occasionally, bus drivers would drive away before black passengers were able to reboard. National City Lines owned the Montgomery Bus Line at the time of the Montgomery bus boycott. Under the leadership of Walter Reuther, the United Auto Workers donated almost $5,000 (equivalent to $51,000 in 2021) to the boycott’s organising committee.

Boycott

See the full details of the bus boycott on the Wikipedia website

Aftermath

White backlash against the court victory was quick, brutal, and, in the short term, effective. Two days after the inauguration of desegregated seating, someone fired a shotgun through the front door of Martin Luther King’s home. A day later, on Christmas Eve, white men attacked a black teenager as she exited a bus. Four days after that, two buses were fired upon by snipers. In one sniper incident, a pregnant woman was shot in both legs. On January 10, 1957, bombs destroyed five black churches and the home of Reverend Robert S. Graetz, one of the few white Montgomerians who had publicly sided with the MIA.

The City suspended bus service for several weeks on account of the violence. According to legal historian Randall Kennedy, “When the violence subsided and service was restored, many black Montgomerians enjoyed their newly recognised right only abstractly … In practically every other setting, Montgomery remained overwhelmingly segregated …” On January 23, a group of Klansmen (who would later be charged for the bombings) lynched a black man, Willie Edwards, on the pretext that he was dating a white woman.

The city’s elite moved to strengthen segregation in other areas, and in March 1957 passed an ordinance making it “unlawful for white and colored persons to play together, or, in company with each other … in any game of cards, dice, dominoes, checkers, pool, billiards, softball, basketball, baseball, football, golf, track, and at swimming pools, beaches, lakes or ponds or any other game or games or athletic contests, either indoors or outdoors.”

Later in the year, Montgomery police charged seven Klansmen with the bombings, but all of the defendants were acquitted. About the same time, the Alabama Supreme Court ruled against Martin Luther King’s appeal of his “illegal boycott” conviction. Rosa Parks left Montgomery due to death threats and employment blacklisting. According to Charles Silberman, “by 1963, most Negroes in Montgomery had returned to the old custom of riding in the back of the bus.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

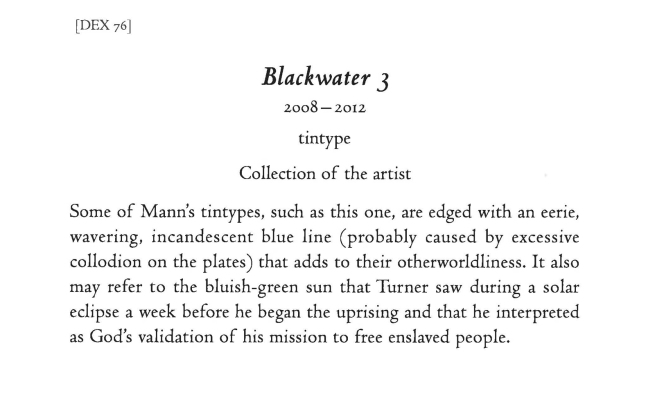

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Shreveport, Louisiana

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Walls, Mississippi

1984

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Lula, Mississippi

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Lula, Mississippi

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Helena, Arkansas

1986

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Natchez, Mississippi

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Joseph Bellows Gallery is pleased to announce its upcoming exhibition, Baldwin Lee. The exhibition will open with a reception for the artist on Saturday, the 22nd of October, from 4 – 6pm, and continue through December 10th. This will be the second solo exhibition of the photographer’s work presented by Joseph Bellows Gallery. The gallery first showcased Lee’s epic project online, from April 18th – June 26, 2020.

The upcoming show will present a remarkable selection of vintage prints from this critically acclaimed and highly celebrated body of work taken within Black communities in the South, that began in 1983, and continued throughout that decade. The resulting collection of images from this seven-year period contains nearly ten thousand black-and-white negatives taken with a 4 x 5-inch view camera. Lee’s graceful pictures from this project perfectly balance the photographer’s presence and the subject’s will, honouring both through the resulting, beautifully printed 16 x 20-inch black-and-white photographs. The esteemed photography curator Joshua Chuang has noted that, “The pictures stand apart, not because they are depictions of Black subjects by a first-generation Chinese-American, but because they were made by a photographer of rare perception and instinct.”

Baldwin Lee studied photography with Minor White at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, receiving a Bachelor of Science degree in 1972. Lee then continued his education at Yale University, where he studied with Walker Evans. He received a Master of Fine Arts in 1975. After school, Lee began teaching photography at the Massachusetts College of Art and then at Yale, while creating his own photographs, which at the time were rooted in the exploration of the contemporary built environment. Lee’s later work from the early to late-1980s entitled, Black Americans in the South (from which this exhibition is drawn), is a compelling and empathic portrait that represents its subjects within their rural environments, expressing the joys of childhood, the gravity of adult life, and the places in between. Images from Lee’s Southern work were featured in Aperture Magazine, Issue 115, ‘New Southern Photography: Between Myth and Reality’ (1989), and now form the newly published monograph, Baldwin Lee (Hunters Point Press, 2022).

Lee’s work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Chrysler Museum of Art, the Knoxville Museum of Art, the Southeast Center for Contemporary Art, and the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia. His photographs are in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the University of Michigan Museum of Art, the University of Kentucky Art Museum, the Yale University Art Gallery, The Morgan Library, and the Museum of the City of New York. He has been honoured with fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation (1984) and the National Endowment for the Arts (1984 and 1990).

Text from the Joseph Bellows Gallery website [Online] Cited 28/10/2022

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Boyle, Mississippi

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Columbia, South Carolina

1984

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Rosedale, Mississippi

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Monroe, Louisiana

1985

Gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Mobile, Alabama

1983

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Mobile, Alabama

20th century

The turn of the 20th century brought the Progressive Era to Mobile. The economic structure developed with new industries, generating new jobs and attracting a significant increase in population.[50] The population increased from around 40,000 in 1900 to 60,000 by 1920. During this time the city received $3 million in federal grants for harbour improvements to deepen the shipping channels. During and after World War I, manufacturing became increasingly vital to Mobile’s economic health, with shipbuilding and steel production being two of the most important industries.

During this time, social justice and race relations in Mobile worsened, however. The state passed a new constitution in 1901 that disenfranchised most blacks and many poor whites; and the white Democratic-dominated legislature passed other discriminatory legislation. In 1902, the city government passed Mobile’s first racial segregation ordinance, segregating the city streetcars. It legislated what had been informal practice, enforced by convention. Mobile’s African-American population responded to this with a two-month boycott, but the law was not repealed. After this, Mobile’s de facto segregation was increasingly replaced with legislated segregation as whites imposed Jim Crow laws to maintain supremacy.

In 1911 the city adopted a commission form of government, which had three members elected by at-large voting. Considered to be progressive, as it would reduce the power of ward bosses, this change resulted in the elite white majority strengthening its power, as only the majority could gain election of at-large candidates. In addition, poor whites and blacks had already been disenfranchised. Mobile was one of the last cities to retain this form of government, which prevented smaller groups from electing candidates of their choice. But Alabama’s white yeomanry had historically favoured single-member districts in order to elect candidates of their choice. …

A race riot broke out in May 1943 of whites against blacks. ADDSCO management had long maintained segregated conditions at the shipyards, although the Roosevelt administration had ordered defence contractors to integrate facilities. That year ADDSCO promoted 12 blacks to positions as welders, previously reserved for whites; and whites objected to the change by rioting on May 24. The mayor appealed to the governor to call in the National Guard to restore order, but it was weeks before officials allowed African Americans to return to work, keeping them away for their safety.

In the late 1940s, the transition to the postwar economy was hard for the city, as thousands of jobs were lost at the shipyards with the decline in the defence industry. Eventually the city’s social structure began to become more liberal. Replacing shipbuilding as a primary economic force, the paper and chemical industries began to expand. No longer needed for defence, most of the old military bases were converted to civilian uses. Following the war, in which many African Americans had served, veterans and their supporters stepped up activism to gain enforcement of their constitutional rights and social justice, especially in the Jim Crow South. During the 1950s the City of Mobile integrated its police force and Spring Hill College accepted students of all races. Unlike in the rest of the state, by the early 1960s the city buses and lunch counters voluntarily desegregated. …

In 1963, three African-American students brought a case against the Mobile County School Board for being denied admission to Murphy High School. This was nearly a decade after the United States Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. The federal district court ordered that the three students be admitted to Murphy for the 1964 school year, leading to the desegregation of Mobile County’s school system.

The civil rights movement gained congressional passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, eventually ending legal segregation and regaining effective suffrage for African Americans. But whites in the state had more than one way to reduce African Americans’ voting power. Maintaining the city commission form of government with at-large voting resulted in all positions being elected by the white majority, as African Americans could not command a majority for their candidates in the informally segregated city. …

Mobile’s city commission form of government was challenged and finally overturned in 1982 in City of Mobile v. Bolden, which was remanded by the United States Supreme Court to the district court. Finding that the city had adopted a commission form of government in 1911 and at-large positions with discriminatory intent, the court proposed that the three members of the city commission should be elected from single-member districts, likely ending their division of executive functions among them. Mobile’s state legislative delegation in 1985 finally enacted a mayor-council form of government, with seven members elected from single-member districts. This was approved by voters. As white conservatives increasingly entered the Republican Party in the late 20th century, African-American residents of the city have elected members of the Democratic Party as their candidates of choice. Since the change to single-member districts, more women and African Americans were elected to the council than under the at-large system.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

New Orleans, Louisiana

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Canton, Mississippi

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Plain Dealing, Louisiana

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Plain Dealing is a town in Bossier Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 893 in 2020.

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Columbia, South Carolina

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Quitman, Georgia

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Quitman is a city in and the county seat of Brooks County, Georgia, United States. The population was 3,850 at the 2010 census.

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Valdosta, Georgia

1984

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Valdosta, Georgia

Valdosta is a city in and the county seat of Lowndes County, Georgia, United States. As of 2019, Valdosta had an estimated population of 56,457.

On May 16, 1918, a white planter named Hampton Smith was shot and killed at his house near Morven, Georgia, by a black farm worker named Sidney Johnson who was routinely mistreated by Smith. Johnson also shot Smith’s wife but she later recovered. Johnson hid for several days in Valdosta without discovery. Lynch mobs formed in Valdosta ransacking Lowndes and Brooks counties for a week looking for Johnson and his alleged accomplices. These mobs lynched at least 13 African Americans, among them Mary Turner and her unborn eight-month-old baby who was cut from her body and murdered. Mary Turner’s husband Hazel Turner was also lynched the day before.

Sidney Johnson was turned in by an acquaintance, and on May 22 Police Chief Calvin Dampier led a shootout at the Valdosta house where he was hiding. Following his death, a crowd of more than 700 castrated Johnson’s body, then dragged it behind a vehicle down Patterson Street and all the way to Morven, Georgia, near the site of Smith’s murder. There the body of Johnson was hanged and burned on a tree. That afternoon, Governor Hugh Dorsey ordered the state militia to be dispatched to Valdosta to halt the lynch mobs, but they arrived too late for many victims. Dorsey later denounced the lynchings, but none of the participants were ever prosecuted.

Following the violence, more than 500 African Americans fled from Lowndes and Brooks counties to escape such oppressive conditions and violence. From 1880 to 1930, Brooks County had the highest number of lynchings in the state of Georgia. By 1922 local chapters of the Ku Klux Klan, which had been revived starting in 1915, were holding rallies openly in Valdosta.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Valdosta, Georgia

1986

Vintage gelatin silver print

20 x 16 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Garnett, South Carolina

1985

Vintage gelatin silver print

20 x 16 inches

In 1983, Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951) left his home in Knoxville, Tennessee, with his 4 × 5 view camera and set out on the first of a series of road trips to photograph the American South. The subject of his pictures were Black Americans: at home, at work, and at play, in the street, and among nature. This project would consume Lee – a first-generation Chinese American – for the remainder of that decade, and it would forever transform his perception of his country, its people, and himself. The resulting archive from this seven-year period contains nearly ten thousand black-and-white negatives. This monograph, Baldwin Lee, presents a selection of eighty-eight images edited by the photographer Barney Kulok, accompanied by an interview with Lee by the curator Jessica Bell Brown and an essay by the writer Casey Gerald. Arriving almost four decades after Lee began his journey, this publication reveals the artist’s unique commitment to picturing life in America and, in turn, one of the most piercing and poignant bodies of work of its time.

“A new book – the first-ever collection of [Baldwin] Lee’s work – and a solo exhibition in New York make the case that he is one of the great overlooked luminaries of American picture-making. It’s not often that a body of photography is hoisted up from obscurity and straight into the canon.”

~ Chris Wiley, The New Yorker

“The warmth and soulfulness of his work is not the result of intellectual effort; it’s grounded in understanding, a combination of intensity and restraint, and, surely, a shared sense of otherness.”

~ Vince Aletti, Photograph Magazine

“… Walker Evans was one of Lee’s teachers. Like Evans, Lee has a sensitive eye for both poverty and dignity. But Lee’s southern exposure wasn’t overwhelmingly white, as it was in Evans’s classic “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.” Quite the contrary, Lee is a witness to those at the bottom of U.S. stratification, and their refusal to swallow that status. … The work is political, because it exposes the violence of poverty inherited from the plantation-economy past. But it is most of all attentiveness to the composure of his subjects that is echoed masterfully in the composition of his shots. …We are a motley assortment of people in the United States. Our relations are not tidy, not in their beauty, nor in their disastrous disaffection and cruelty. ”

~ Imani Perry, The Atlantic

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

16 x 20 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

20 x 16 inches

Baldwin Lee (Chinese-American, b. 1951)

Untitled

1983-1989

Vintage gelatin silver print

20 x 16 inches

Joseph Bellows Gallery

7661 Girrard Avenue

La Jolla, California

Phone: 858 456 5620

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm and by appointment

You must be logged in to post a comment.