Exhibition dates: 16th November 2022 – 27th February 2023

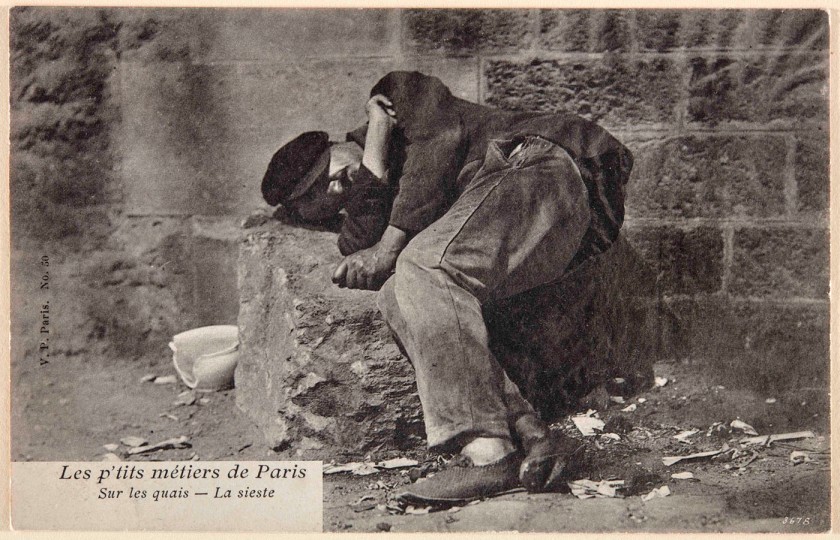

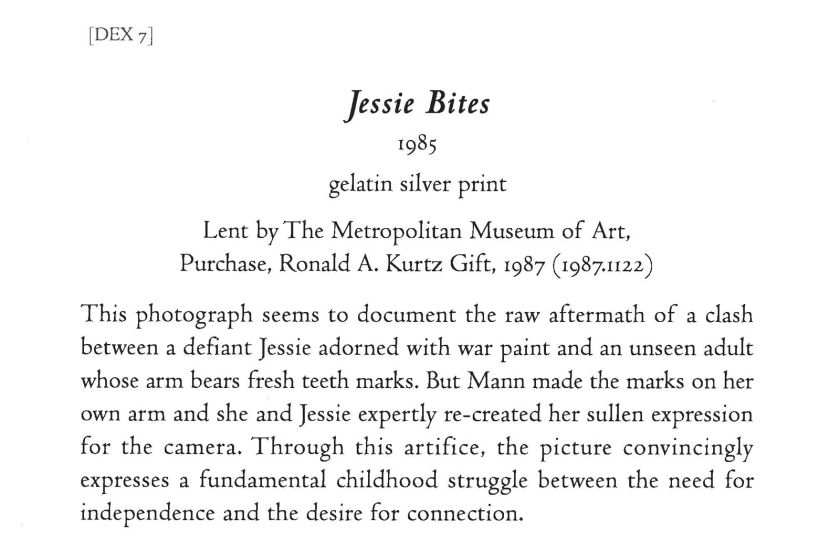

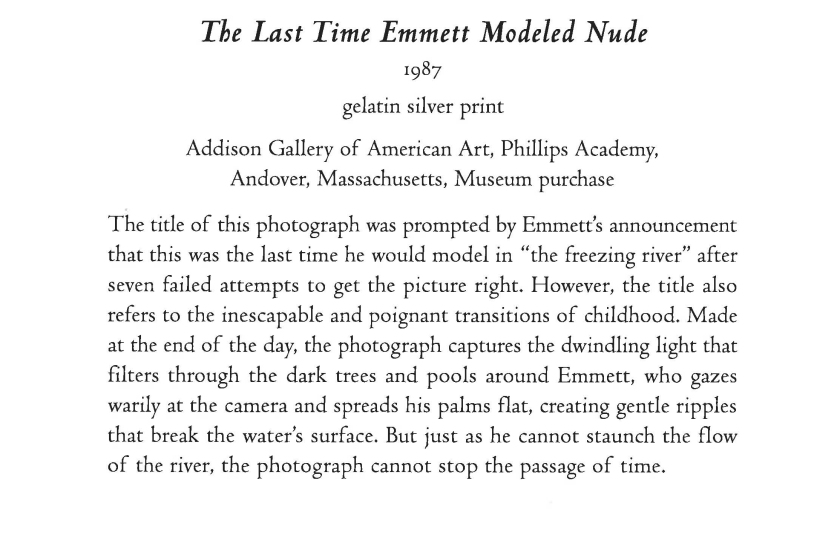

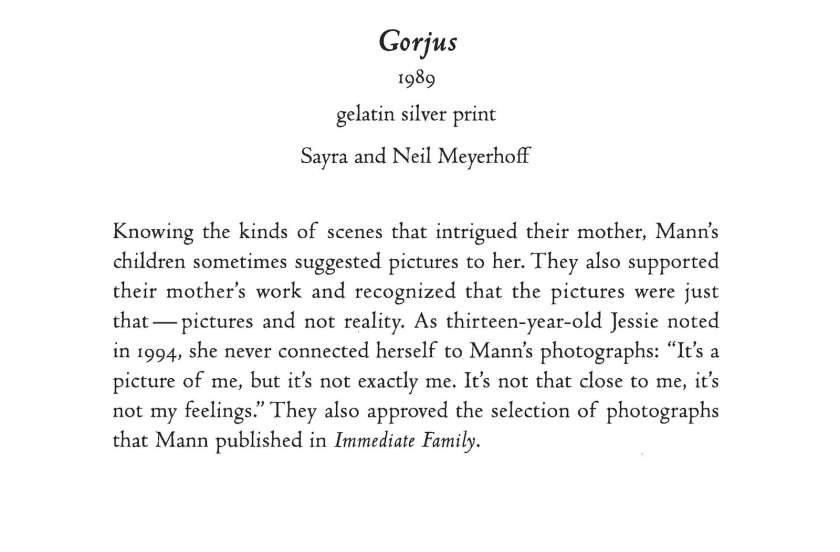

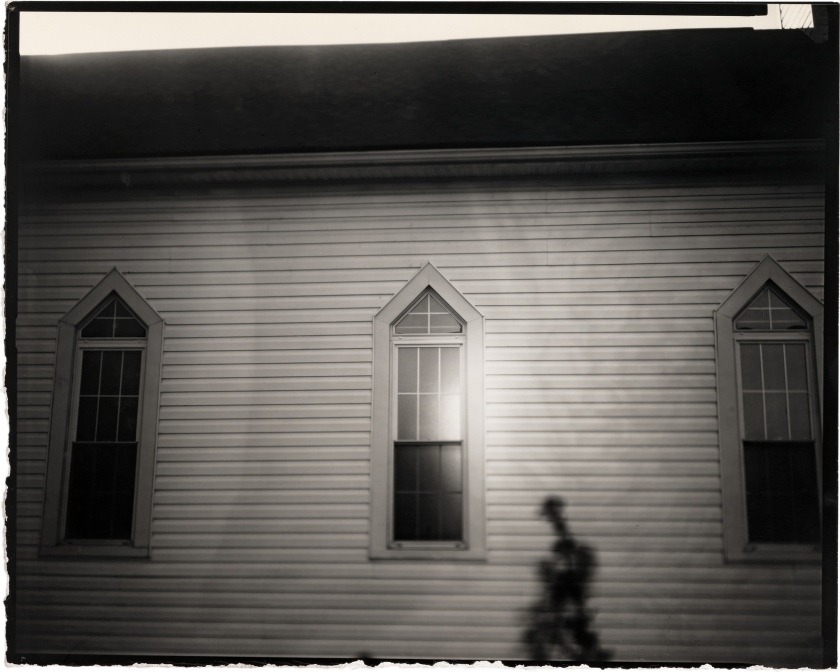

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Sur les quais – La sieste / Les p’tits métiers de Paris

On the quays – The siesta / The little jobs in Paris

c. 1898-1900, printed 1904

Collotype

8.8 x 13.7cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

“While human truth may be ephemeral qualities like justice are not; the struggle is to define justice and to live it. And for artists to display it.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Another fascinating exhibition that extends the remit of “documentary” photography back to the earliest days of the medium and the “the empire of photography”: the rise of a new visual regime that became an instrument for the system of bourgeois, industrial and colonial culture in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In other words in the hands of the powerful (both national and personal) photography became an instrument which reinforced the entitlement and social position of the privileged while depriving the disenfranchised of a visual voice, and thus legitimacy and recognition of their plight. Photography also became the means to form a taxonomic ordering of supposed genetic deficiencies, ethnicities, criminals, homosexuals and revolutionaries, amongst others.

“The democratic promise of photography was long unfulfilled and remained, for over almost a century, an instrument in the hands of bourgeois culture and its means of representation. Thus, the portraits of the working and subaltern classes were an accidental and marginal incursion, an involuntary presence inside pictures with another intention.” (Press release)

Here I would disagree with the assertion that portraits of the working classes were an accidental and marginal incursion, an involuntary presence inside pictures with another intention. “Incursion” means an invasion or attack. “Involuntary” means done without will or conscious control. So images of the poor appear, without any conscious control, as an attack inside / against images that reinforce their prerogative meaning?

Perhaps the poor are just human beings that lived and breathed the same air as the photographer, that perchance appeared through serendipity in the images with no ulterior motive attached to their being … other than those that have been attached to their representation at a later date. Interpretations of photographs change over time and we have to think how these photographs would have been read when they were first taken.

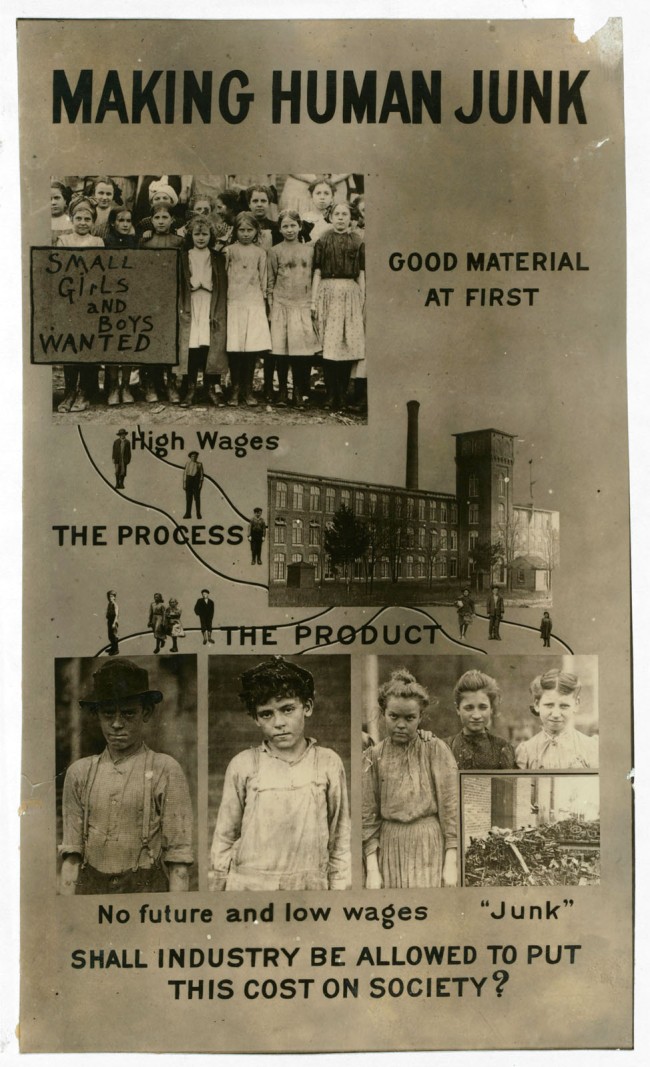

The terms accidental and marginal are critical. In the work of politically engaged now called social documentary photographers – for example Lewis Hine, Jacob Riis, John Thomson, Hill and Adamson, O.G. Rejlander and Paul Martin – these artists captured photographs of the working classes that are neither accidental nor marginal. They are deliberate and provocative photographs taken to raise awareness of social conditions and injustice in order to bring about a change in the law (such as the anti-slavery laws and child labor laws in the United States) or a change in social conditions of the poor such as the state of slum housing or tenement house evils for example.

There is nothing marginal about these photographs, no margin in which to ostracise, nor any accident of inclusion, for the human beings in them are placed front and centre before the public ‘in order’ to expose an immorality or injustice that was supposed to be hidden from view.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“During the 1830s, a period covered by [the novel] Middlemarch, much was changing in terms of class/social structure. During the Victorian era, the rates of people living in poverty increased drastically. This is due to many factors, including low wages, the growth of cities (and general population growth), and lack of stable employment. The poor often lived in unsanitary conditions, in cramped and unclean houses, regardless of whether they lived in a modern city or a rural town. Victorian attitudes towards the poor were rather muddled. Some believed that the poor were facing their situations because they deserved it, either because of laziness or because they were simply not worthy of fortune. However, some believed it was up to personal circumstances. It is important to note that many charities have their roots from this era in English history, because of how overwhelming the issue of poverty became at this time.”

Anonymous. “The life of the poor in Victorian England,” on the Cove website Nd [Online] Cited 23/02/2023

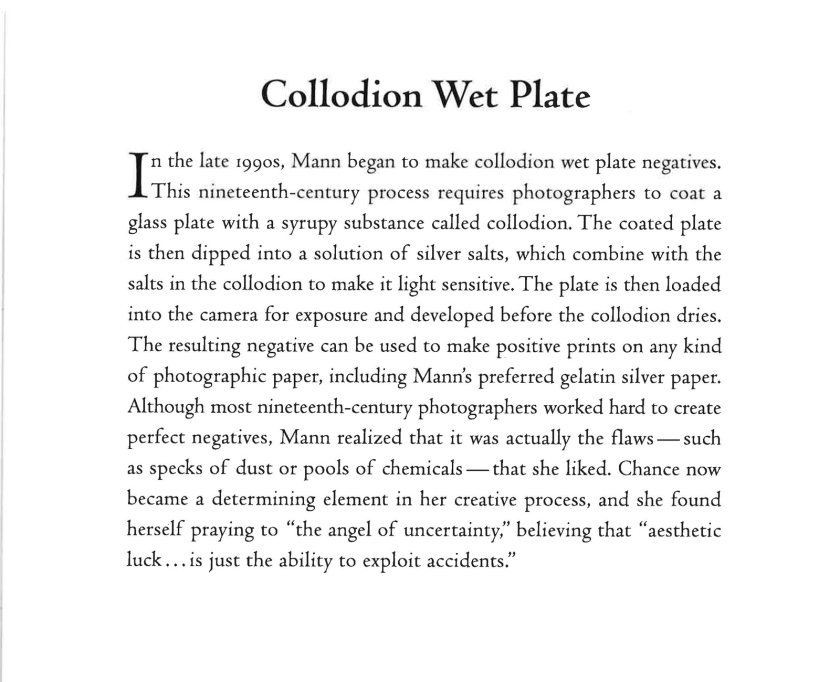

At centre, Lewis Hine exhibition panels 1913-1914 (see below)

At left rear, pages from Carl Dammann’s [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876 (see below)

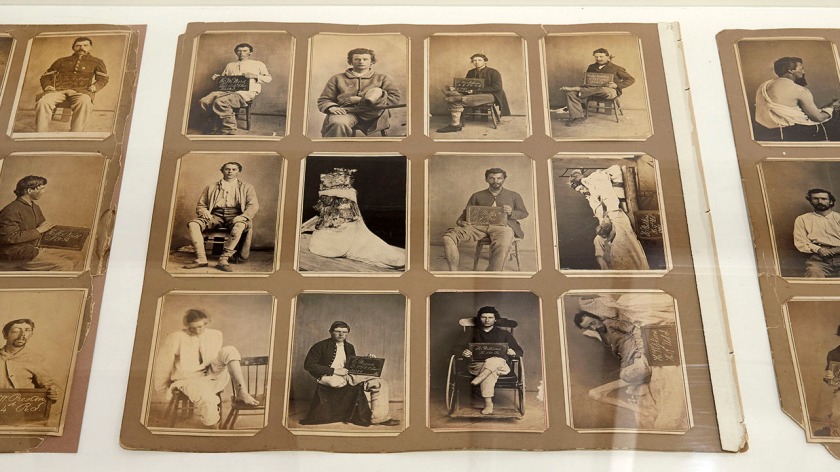

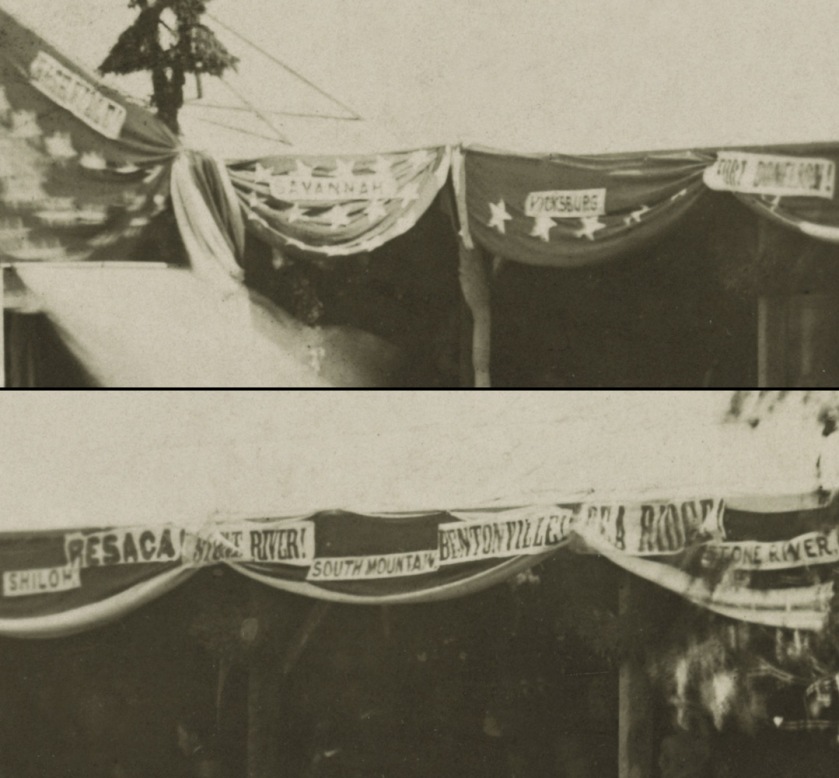

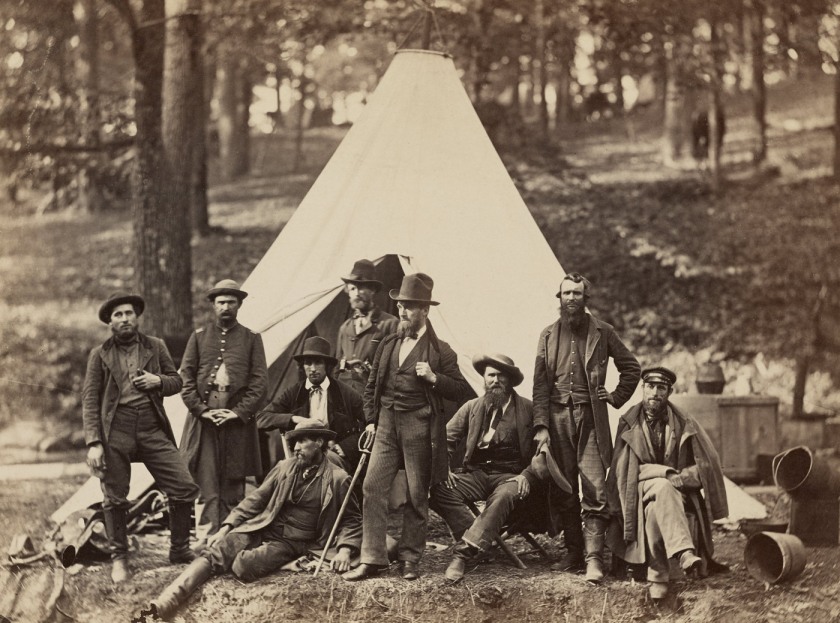

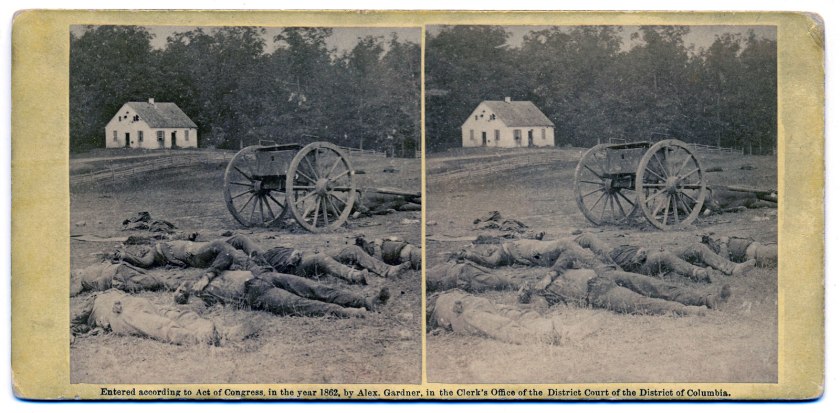

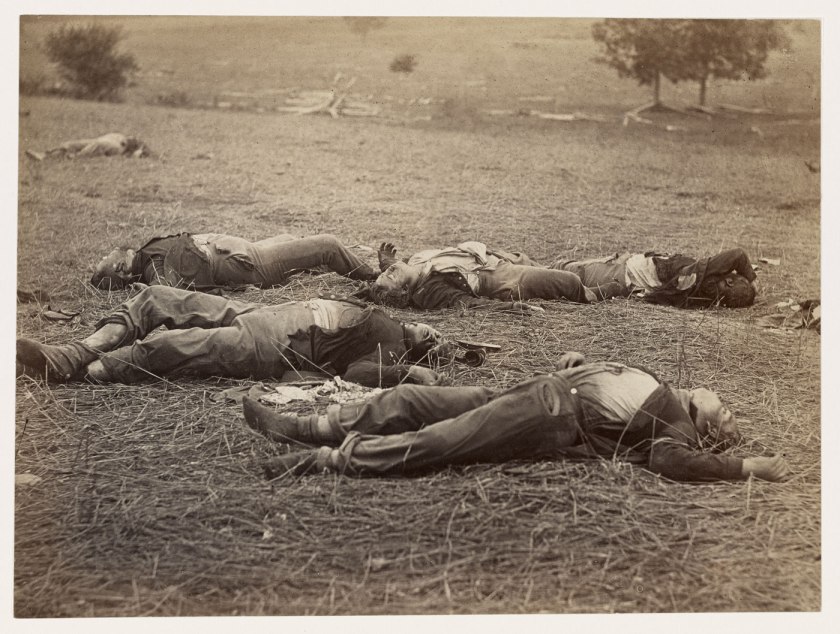

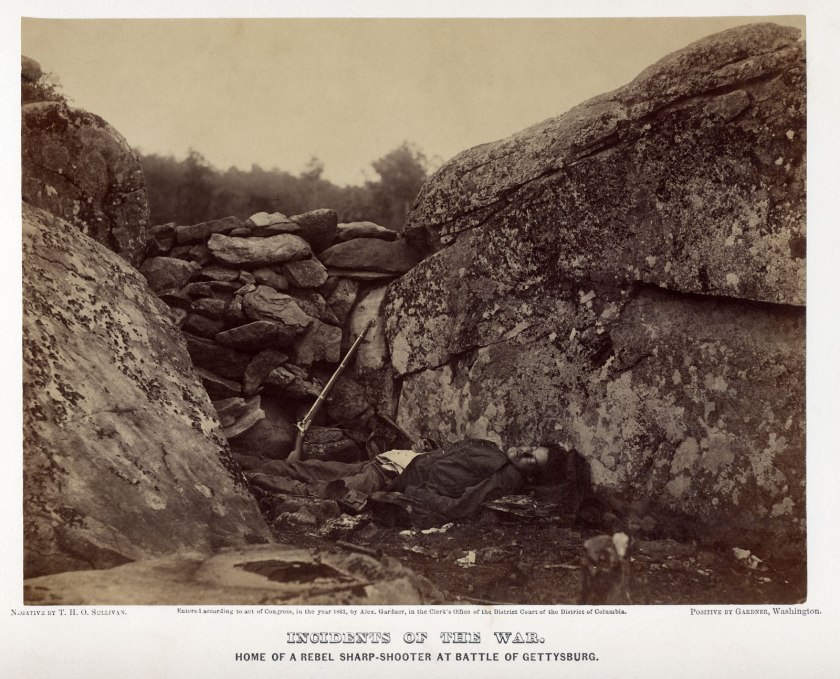

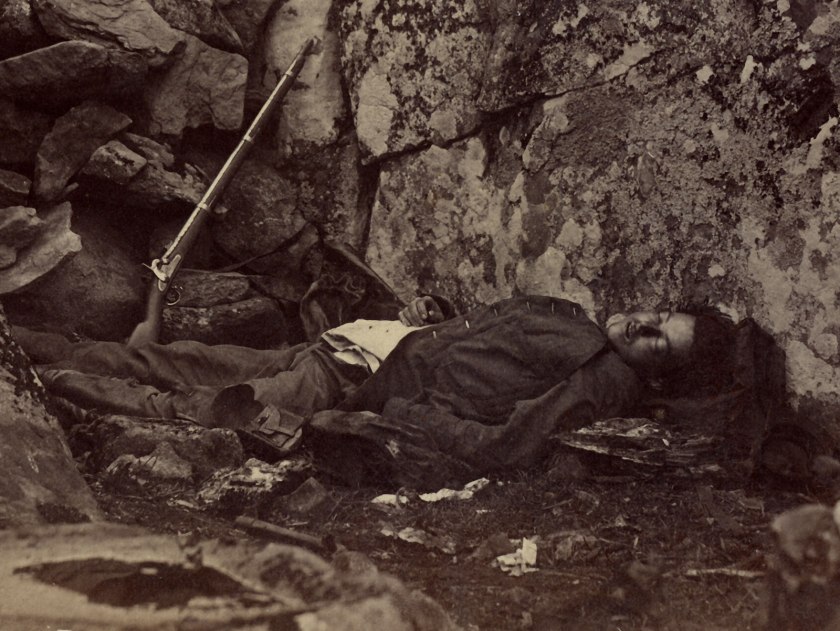

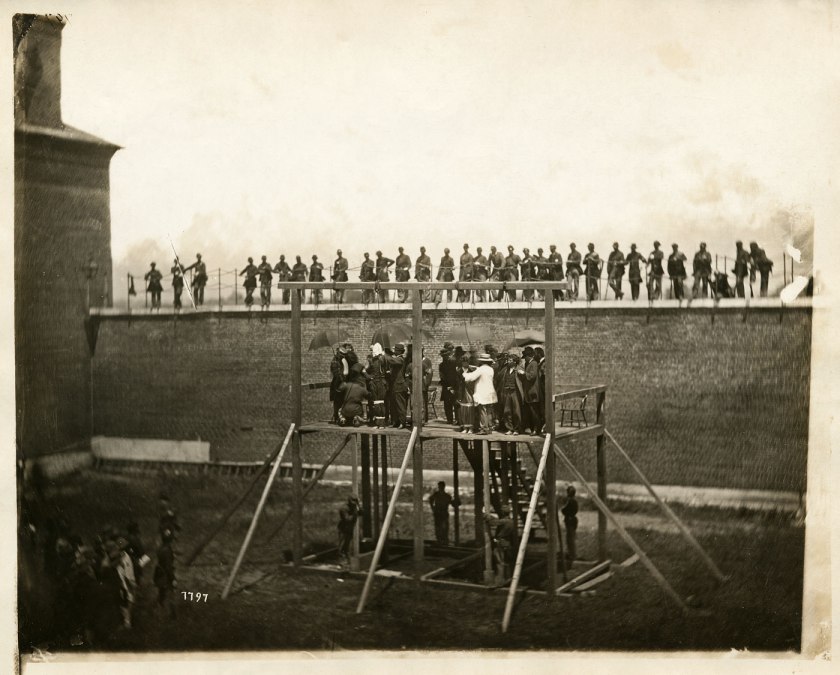

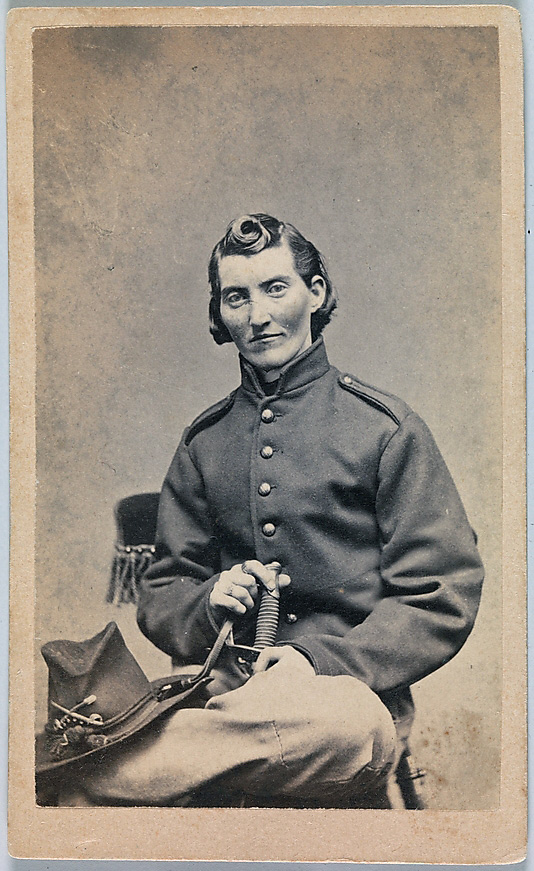

Wounded men from the American Civil War

Pages from the book Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance by N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894, photographs by unknown artists, with at centre left an image of Bachibonzouk, a Greek wearing traditional Turkish needlework and embroidery reminiscent of the uniforms worn by the Sultan’s officers, as seen at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, 1893 (see below)

Installation views of the exhibition Documentary Genealogies: Photography 1848-1917 at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

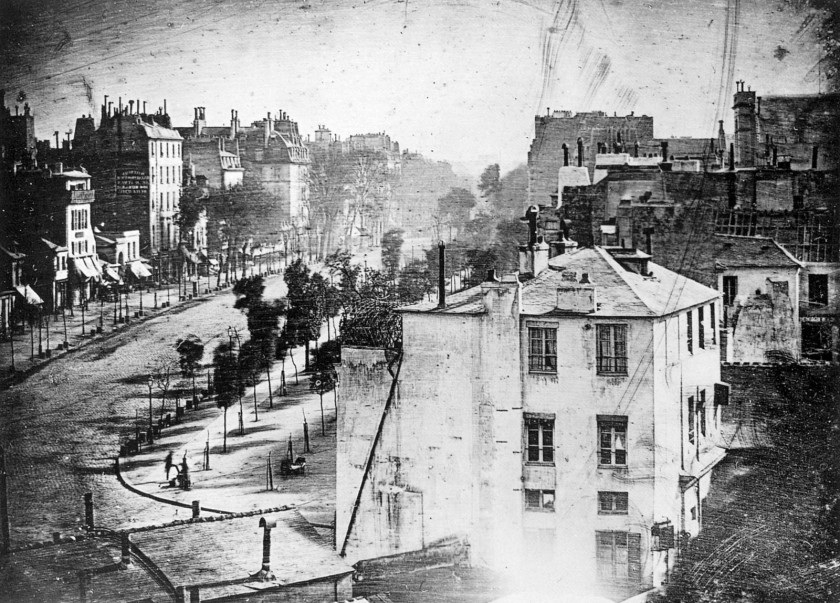

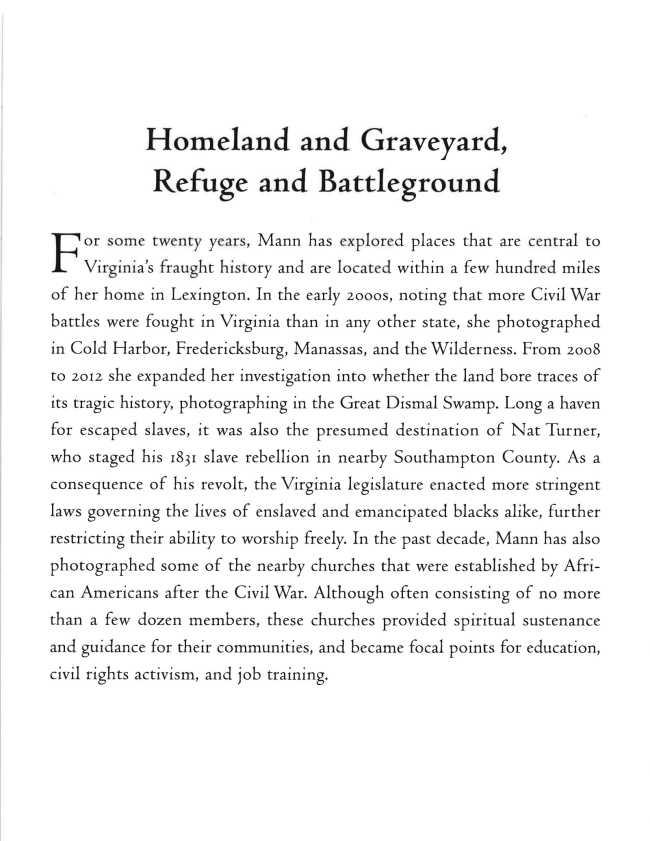

Documentary Genealogies. Photography 1848-1917 starts from Walter Benjamin’s remark in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility (1936) on the parallel emergence of photography and of socialism. Following such parallel allows the hypothesis that the ideas and iconographies used to represent the everyday life of the working class – which is the constitutive impulse for the rise of documentary discourse and practices in the 1920s, as a specific form of filmic and photographic poetics – were already latent or active in 1840s visual culture. The seminal figure of the bootblack on Boulevard du Temple [Boulevard of the Temple, 1838], one of Louis Daguerre’s first daguerreotypes, is the first appearance of the worker in photography: the root of the historical narrative around class relations and conflicts, an axis for the documentary discourse to come.

This exhibition presents a cartography of practices related to the appearance and evolution of representations of subaltern identities – workers, servants, proletarians, beggars, the deprived – stretching from the rise of photography to the turn of the century (more specifically, between the European revolutionary cycle of 1848 and the Russian Revolution in 1917), and inside the framework termed by historian André Rouillé as “the empire of photography”: the rise of a new visual regime that became an instrument for the system of bourgeois, industrial and colonial culture in the second half of the nineteenth century. Such subaltern figures can also be understood as metaphors of Charles Baudelaire’s famous and seminal condemnation to photography which he consigned to a subordinate position, as “the servant of the arts”. The democratic promise of photography was long unfulfilled and remained, for over almost a century, an instrument in the hands of bourgeois culture and its means of representation. Thus, the portraits of the working and subaltern classes were an accidental and marginal incursion, an involuntary presence inside pictures with another intention.

Documentary Genealogies. Photography 1848-1917 closes a series that began in 2011 in the Museo Reina Sofía with the exhibitions A Hard, Merciless Light. The Worker Photography Movement, 1926-1939 and continued in 2015 with Not Yet. On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism, both of which offered an alternative narrative of the rise and evolution of documentary discourse in the history of photography, based on case studies at key moments in the twentieth century. This final exhibition contributes to this narrative from a different, proto-historical perspective: an observation of the early promises and potential of photography contained in the fact that the documentary idea and function are as old as photography itself.

Text from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía website

Louis Daguerre (French, 1787-1851)

Boulevard du Temple

Between 24 April 1838 and 4 May 1838

Daguerreotype

Public domain

This image is not in the exhibition

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3rd arrondissement, Daguerreotype. Made in 1838 by inventor Louis Daguerre, this is believed to be the earliest photograph showing a living person. It is a view of a busy street, but because the exposure lasted for 4 to 5 minutes (see shutter speed Daguerre photo explained) the moving traffic left no trace. Only the two men near the bottom left corner, one apparently having his boots polished by the other, stayed in one place long enough to be visible. As with most daguerreotypes, the image is a mirror image.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

Rahlo Jammele. (Jewish Dancing Girl.)

c. 1894

From the book Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance

N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894

Unknown photographer

Jeanette Le Barre. (French Peasant Girl.)

c. 1894

From the book Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance

N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894

Unknown photographer

William. (Samoan.)

c. 1894

From the book Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance

N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894

Oriental and Occidental Northern and Southern Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance

N.D. Thompson Publishing Company, 1894

Putnam, F. W. (Frederic Ward), 1839-1915/ Oriental and occidental, northern and southern portrait types of the Midway Plaisance: a collection of photographs of individual types of various nations from all parts of the world who represented, in the Department of Ethnology, the manners, customs, dress, religions, music and other distinctive traits and peculiarities of their race: with interesting and instructive descriptions accompanying each portrait, together with an introduction. St. Louis : N.D. Thompson, 1894.

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Blind Woman

Camera Work 49/50, July 1917

Photoengraving on paper

23.3 x 16.7cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

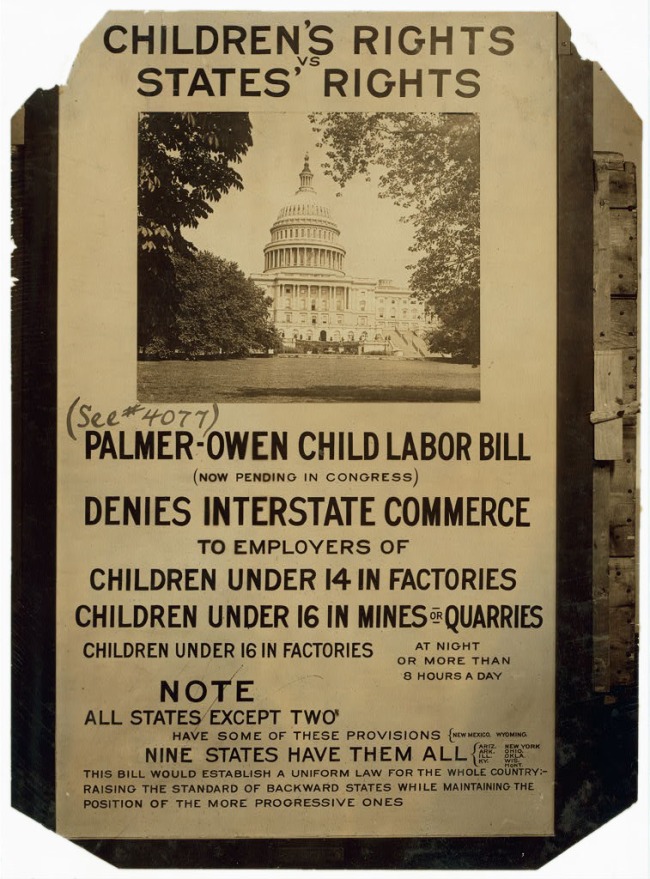

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Making Human Junk

Exhibition panel from the National Child Labor Committee Facsimile reconstruction

1913-1914

Image courtesy of Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Lewis Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Children’s Rights vs States’ Rights

Exhibition panel from the National Child Labor Committee Facsimile reconstruction

1913-1914

Image courtesy of Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

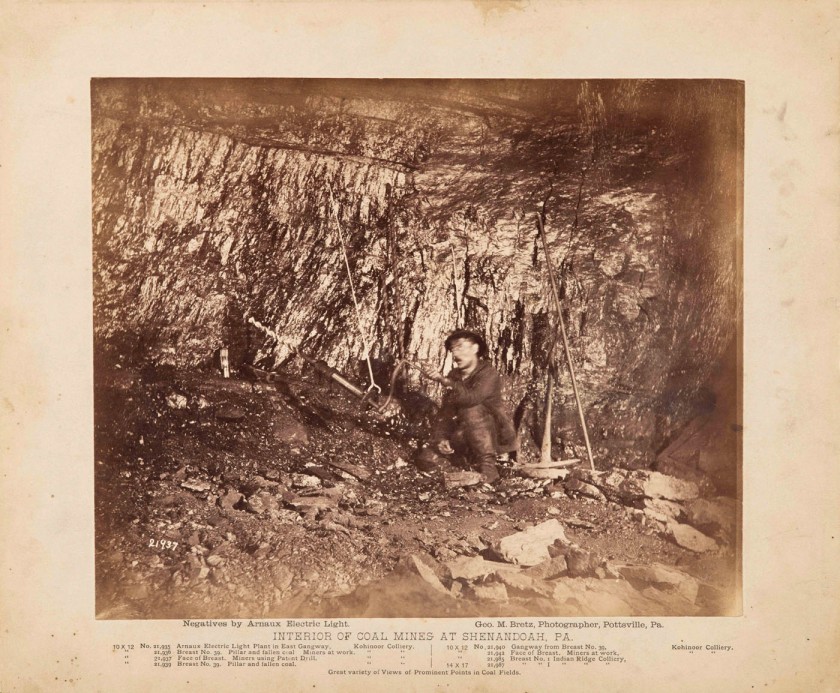

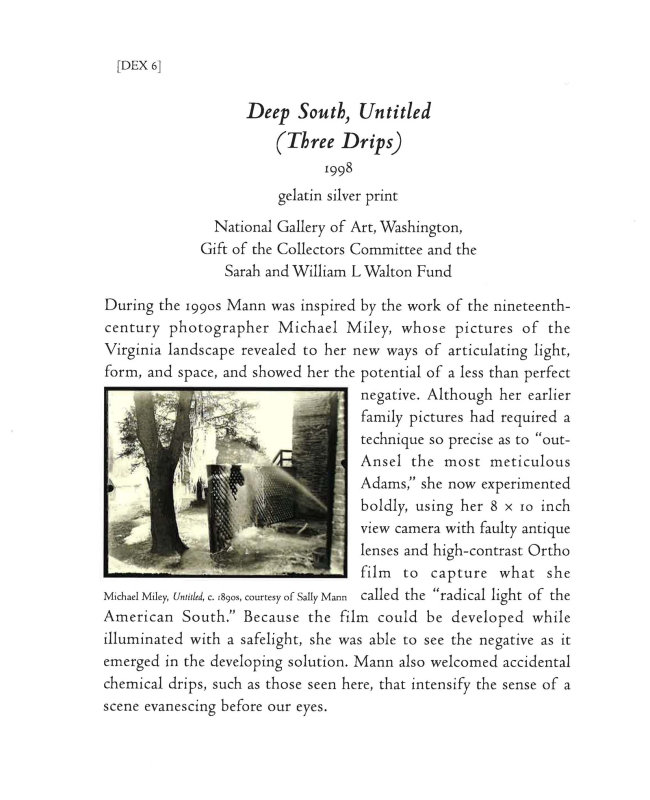

George Bretz (American, 1842-1895)

Miner using coal auger, Kohinoor Colliery, Eastern Pennsylvania

c. 1884

Albumen paper

19.5 x 23cm

Photography Collection, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

George M. Bretz (1842-1895) was an American photographer who is best known for his photographs of the Northeastern Pennsylvania Coal Region and its coal miners.

A collection of Bretz’s original glass plate negatives from the Kohinoor Mine at the Shenandoah Colliery were recently rediscovered at the National Museum of American History. Taken circa 1884, this was one of the earliest fully illuminated photo shoots in an underground mine. These photographs were displayed at the 1884 World Cotton Centennial in New Orleans, and again at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Bretz is also known for his photos of alleged Molly Maguires, radical coal miners who fought against unfair labor practices in the coal fields. For the rest of his life, Bretz was considered an authority on coal mining, and articles about his photography were widely published.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Coal mining was central to the lives of the people in Eastern Pennsylvania especially during the era of 1870 to 1895 when photographer George M. Bretz (1842-1895) lived and worked in Pottsville, the gateway to the Anthracite Coal Mining Region. Bretz achieved distinction if not fame for his photographs related to coal mining and the people who depended upon coal for their livelihood.

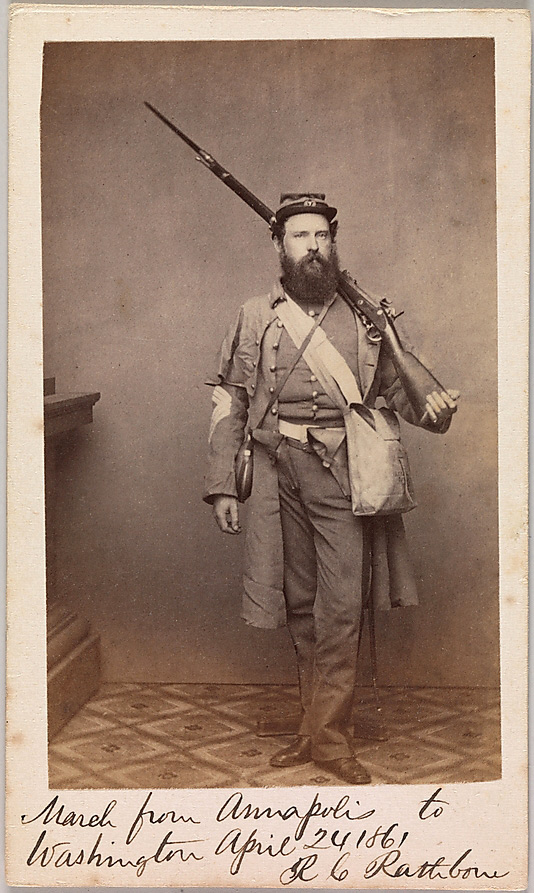

Born in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Bretz worked at local businesses in Carlisle before heading to New York City where he worked successively for two companies in 1859. Letters of reference indicated that he had become a fine young businessman. He worked briefly in 1862 for a photographer before receiving an appointment as a clerk in the quartermaster’s department of the Union Army in Tennessee during the Civil War. Although he was not on the front lines, he was close enough to the war that being captured was often on his mind. He even wrote a will describing the disposition of his body in case he was killed. Serious illness rather than capture or death took him away from the war in 1863. He was sent home to Carlisle to recuperate, and did not rejoin the service until the next year when he became a clerk in the provost marshal’s office, a job that he held until the end of the war.

Photography became Bretz’s focus after the war. He and a friend opened a studio in Newville, Pennsylvania, and continued in operation until 1867 when Bretz went to work in the studio of A.M. Allen in Pottsville. In 1870, Bretz opened his own studio in Pottsville, and made sculptures as well as photographic portraits and landscape views. Among the portraits that Bretz made were images of the alleged Molly Maguires, radical coal miners who turned to violence against unfair labor practices in the coal fields. Bretz made portraits of the alleged Mollies in 1877 on the day before the ten men were to be hanged. Such iconic photographs became the rule rather than the exception for Bretz. In 1884 at the request of the Smithsonian Institution, Bretz descended into a coal mine to photograph miners at work. Using a dynamo that had been set up in the mine, electric light was generated to provide illumination. One critic at the time wrote: “Even in direct sunshine one would hardly undertake to photograph a heap of anthracite coal.” So successful were Bretz’s photographs in the mines, that he gained notoriety for his accomplishment. The photographs were displayed at the New Orleans World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in 1884, and again with additional images at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. For the rest of his life, Bretz was considered an authority on coal mining and articles about him were periodically published in newspapers and photography magazines.

Anonymous. “George Bretz Collection,” on the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) website Nd [Online] Cited 02/02/2023

Unknown photographer

Work scenes from the Krupp Works at Essen: wheel tire transport

Nd

Silver chloride gelatin

22 x 18cm

Historisches Archiv Krupp, Essen

This exhibition presents a specific cartography within the set of practices that André Rouillé termed “the empire of photography”: the new visual regime created by the rise of photography in the bourgeois, industrial, and colonial cultural system in the mid-nineteenth century. Within this new visual regime, the exhibit traces the appearance and early evolution of the representations of subaltern subjectivities: hired-hands, beggars, workers, the unemployed, slaves, prison inmates, the sick, the ill and so on. The representation of the working classes will be the emancipatory impulse for the rise of documentary discourse in the 1920s, but it appears early on as an accidental or marginal interruption, a presence running against the grain in images that have another intention altogether.

1848

The historical narrative begins with the earliest photographic images of a revolution, namely the European revolutionary cycle of 1848. Contemporary historiography cites this “Springtime of the Peoples” as the moment when the proletariat acquired class consciousness, and as the starting point of working-class political struggles. A contradictory starting point, indeed. In January 1848, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels released The Communist Manifesto with the famous diagnosis that the specter of communism was haunting Europe – to be confirmed a month later with the uprisings in Paris. However, shortly after in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), Marx would offer a critical interpretation of 1848 as a parody of the 1789 French Revolution: great world-historic events happen twice, first as tragedy, then as farce.

Image of the People

Beginning in the 1850s, photographic campaigns documenting national monuments, such as the Heliographic Mission in France, were one of the defining drives behind the rise of the “empire of photography”. The Heliographic Mission is a paradigm of how the discourse of national historic monuments was instrumental for the ideology of the nation-state and for nationalist discourses throughout Europe. Several European countries launched their own such campaigns, the pioneer in Spain being Charles Clifford. Clifford retraced Queen Isabella II’s travels in album form, which constitute the earliest photographic statement on the Spanish nation and its heritage. However, the bourgeois nationalist ideology underlying these campaigns and albums was countered by the appearance of certain figures of alterity around the periphery of these images: servants in palaces, the Roma in the Alhambra, small trade and work scenes, beggars, and picturesque street characters who appear spontaneously alongside the architecture.

The Other Half

A second catalyst for the “empire of photography” was the spatial reorganisation of historic urban centres according to the logic and demands of industrialisation. The expansions and reforms, undertaken around 1860 in cities such as Paris, Vienna, Barcelona, and Madrid, gave rise to photography campaigns of both the old streets and medieval city walls that were being demolished, as well as of the new avenues and urban infrastructure. Most emblematic of this process was Charles Marville’s documentation of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s renovation of Paris, which also included images of construction workers and labourers.

As a counterpoint to these photographs of grand urban redevelopments, we find the first images of the urban proletariat. In the New York of the 1880s, muckraking journalist Jacob Riis photographed the miserable conditions of the Lower East Side working-class tenements. He used the images as slides in his public lectures and published the foundational book How the Other Half Lives (1890). With a similar focus and use at public slide lectures, in 1904 Hermann Drawe photographed the Viennese underworld of vagrants and the poor, in collaboration with journalist Emil Kläger. Their reportage was also published as a book. The turn-of-the-century urban peripheries, the terrains vagues [The French term ‘terrain vague’ is used by architects and urban planners to describe forgotten spaces which are left behind as a result of post-industrial urbanisation] created by the razing of the old city walls, and their poor inhabitants, or subproletarians, were photographed by Eugène Atget in Paris, by Heinrich Zille in Berlin, and by Ferdinand Ritter von Staudenheim in Vienna.

Men at Work

The promotion of the new industrial processes, and the grand feats of engineering and infrastructure – another facet of the mid-nineteenth-century construction of the modern nation-state – were also the target of the nascent photographic visual regime. World’s fairs were the mass events that closely followed and helped spread industrialisation. They were also a means for photography to burst into the public sphere. The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London was, in this sense, a key moment. In Spain, Charles Clifford was once again a pioneer, documenting such works as the Isabella II Canal – inaugurated in 1858 to definitely solve the issue of Madrid’s water supply. It is also in this context that the first images of factory labor and industrial workers appeared. The 1890 photographic studies of workers and machinery in the Krupp steelworks in Essen are possibly the pioneering images of the kind. They laid the basis for the most influential iconographies of industrial labor of the twentieth century.

Forced labour was often employed in the grand infrastructure projects, which attests to how industrial capitalism prospered upon the radical exploitation of the working class. In fact, some images of public works and penal colonies may easily be mistaken for one another. In the daguerreotypes of the works led by engineer Lucio del Valle, a pioneer in Spain for photographic documentation of public works, we see prison labourers in chains. Convicts and enslaved labourers are to be found, as well, in images of railroad construction and other work sites during the Civil War period in the United States, and also at the turn of the century in the mines of the Russian penal colony on Sakhalin Island. As part of his production for the Fortieth Parallel Survey, Timothy O’Sullivan reported underground mining using an innovative system of lighting. It is interesting to relate these images to the enigmatic scenes of the Paris catacombs taken by Nadar, souvenirs from a hellish underworld.

The Body and the Archive

Another subtext in photography’s rise during the colonial era is its inscription in modern technologies of social discipline and governance. Photography as a technology of industrialisation was part of a new episteme in the natural and social sciences, and contributed to a new archival unconscious that was symptomatic of the hegemony of positivism. While photography in service of geological exploration had its early golden age in the surveys of the US Western territories that began in the late 1860s after the Civil War. The first such survey was of the Fortieth Parallel, led by geologist Clarence King, with Timothy O’Sullivan as lead photographer.

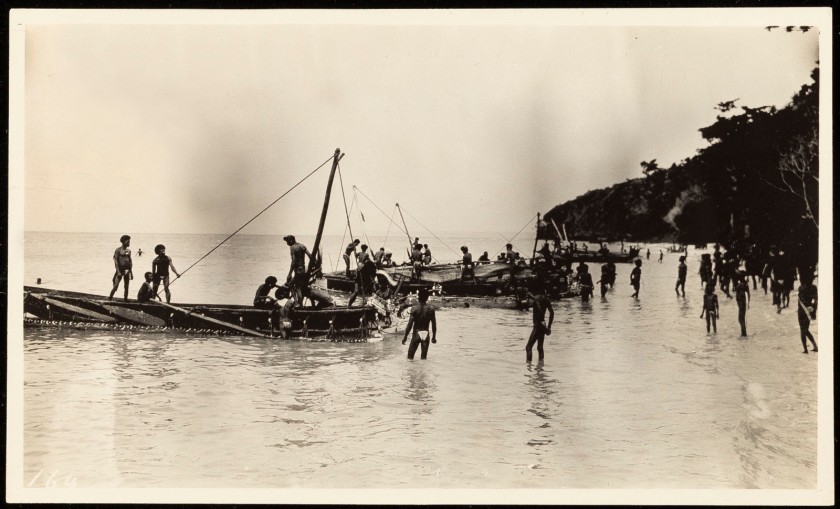

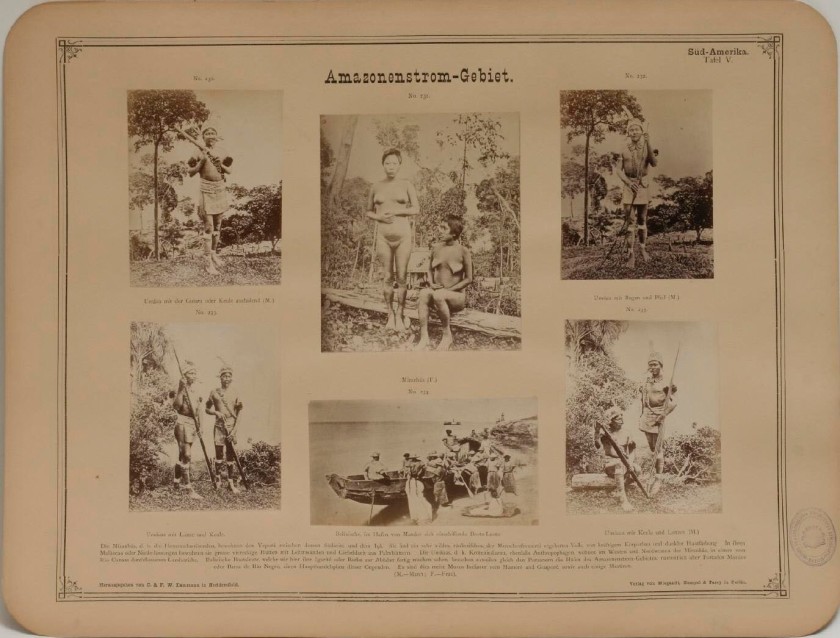

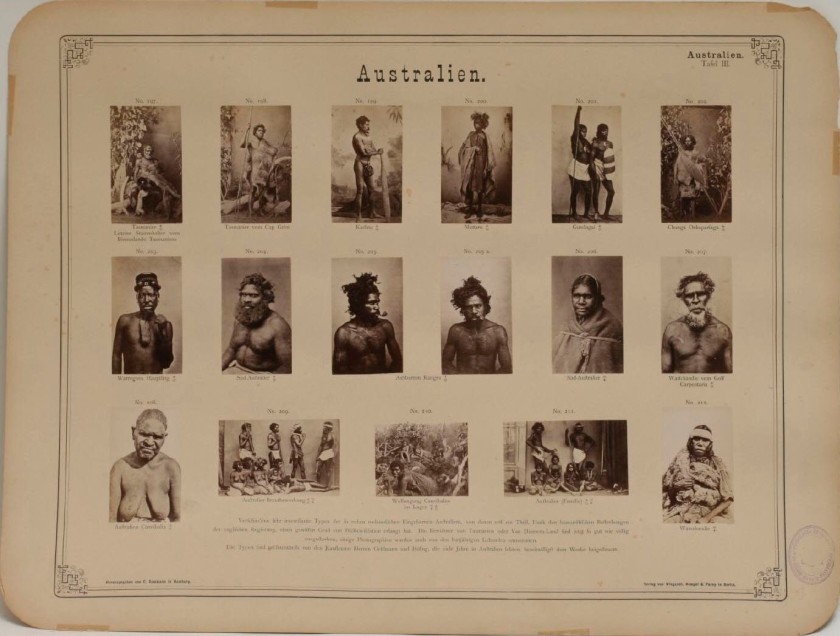

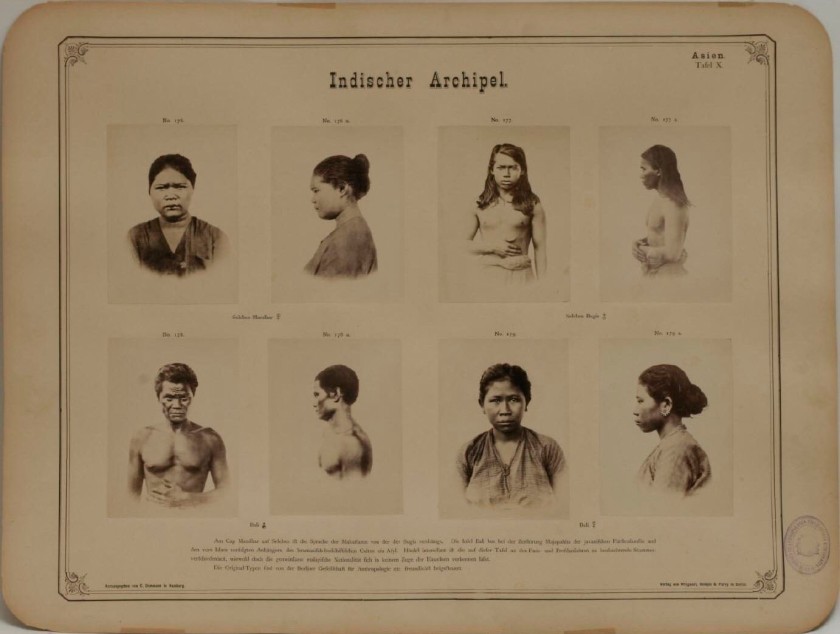

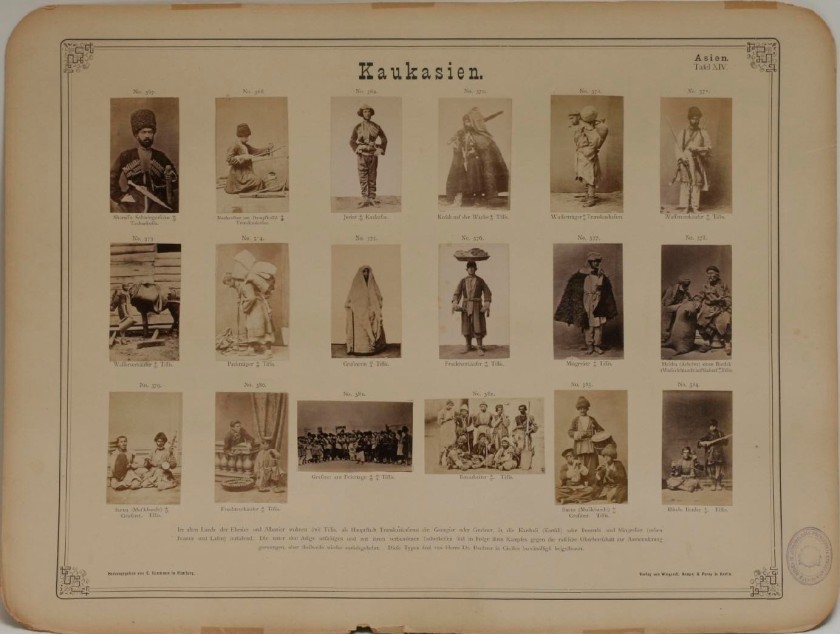

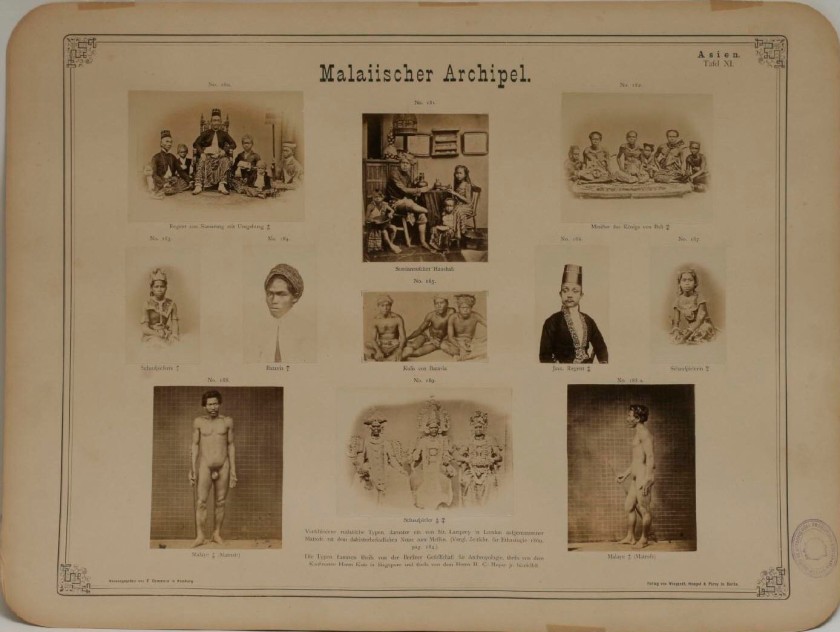

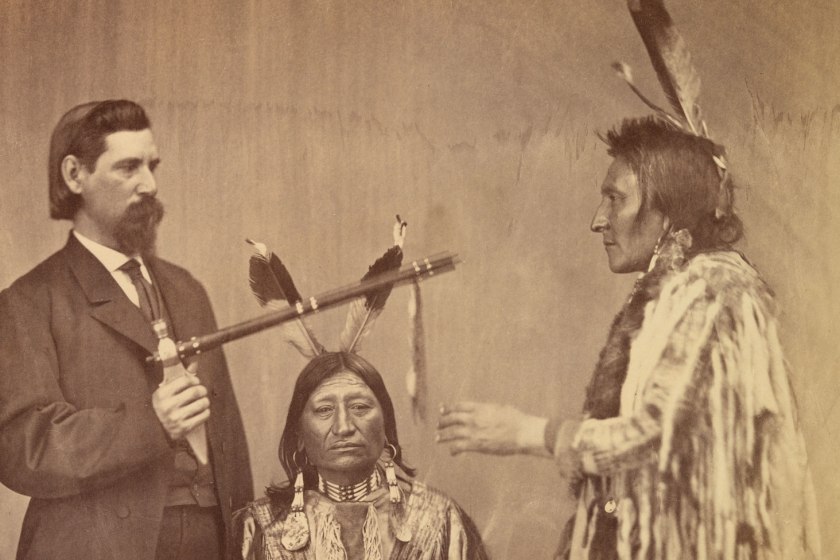

The immense encyclopaedic catalog of human races by German photographer Carl Dammann, published from 1874 onward, is one of the great monuments to the aspirations of positivism in the study of human diversity. Photography changed the methodology of the human sciences. Another example is the art historian Aby Warburg’s study of Hopi Indians in the US southwest in 1895, which he thought of as a journey into the ancient pagan world and led to a famous slide conference in 1923. The trip and conference were instrumental for the emergence of Warburg’s iconological method, which would change the historiography of art by introducing a cultural or anthropological approach. However, it was the work on the Trobriand Islands, by Bronisław Malinowski and his collaborators around 1900, when the use of photography in fieldwork would finally reach maturity. A series of the Trobriand people photographs would later be published, in 1922, in a book that would be essential for modern ethnography, Argonauts of the Western Pacific.

The expansion of anthropological uses of photography in the last decades of the nineteenth century ran parallel to its rise in the medical and judiciary practices. The Civil War in the US yielded a notable corpus of anatomical photographs and various catalogs of the wounded, amputees, and deceased. In Europe, Nadar had already carried out some photographic experiments on medical issues around 1860, such as his research on “hermaphroditism.” Yet the great pioneer of photography in medical experimentation would be neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who studied the then so-called hysteria in women and other neuropsychiatric pathologies in the Parisian Hospital de Pitié-Salpêtrière, beginning in the 1870s. His illustrated publications from the following decade had a huge influence on modern neurology. These practices emerged at the same time as the judiciary and police use of photography, and the standardisation of modern methods of photographic identification, based on the work of Alphonse Bertillon in France, Cesare Lombroso in Italy, and Francis Galton in England. Just as medical photography is inextricable from discourses on health versus pathology or on deviations from the norm, police photography produces typologies of criminal and deviant personalities.

Revolution

The 1871 Paris Commune stands as a foundational experiment in working class self-government. It would become a legendary reference for the political culture of the workers’ movement. The Commune was also the first event to generate an extensive photographic market of a revolution, one which grew from the seeds of the 1848 Parisian daguerreotypes. As a consequence, a visual grammar for the future of revolutionary iconography was set – even if the multiple images of the uprising, produced industrially as albums and souvenirs, had in fact a counterrevolutionary focus. The visual catalog of the barricades, the destruction of monuments such as the Vendôme Column, and the burning of major institutional buildings such as the Paris city hall creates a dystopian, undisciplined image of the city in ruins – as corresponds to the time of uncertainty following the dissolution of the established governmental order.

Social Photography

Following the different revolutionary outbursts and the organisation of the workers’ movement throughout the nineteenth century, some improvements in social rights came about, as well as new public policies to ease the living conditions of the working class within a fledgling welfare state. Lewis Hine was a pioneer in the articulation of photography and social reform politics. Begun in 1907, his photographic work for the National Child Labor Committee “(NCLC)” makes him a founding figure.

Lewis Hine was a professor of photography at the Ethical Culture School in New York City. One of his students was Paul Strand, rendered the founder of photographic modernism because of his work begun in 1916. Influenced by the reception in New York of the Paris pictorial avant-garde, Strand published two portfolios in the modernist magazine Camera Work (1916 and 1917), jointly shaping a sort of manifesto for the future of photography. The 1930s were a time of ideological awakening for Strand, and he would become involved with the Photo League, the New York branch of the international Worker’s Photography Movement. His role as a link between an era that was coming to an end and another that was about to begin make him both the symbol and the most significant symptom of the ambiguity between factuality and idealisation that the documentary idea will carry throughout twentieth-century photography.

Text from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Charles François Thibault (French)

Barricade de la Rue de la Faubourg du Temple

25 June 1848

Daguerreotype, facsimile copy (original from 1848)

Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

CCO Paris Musées / Musee Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

This daguerreotype is part of a series of two exceptional views of the barricades taken during the popular insurrection of June 1848. Disseminated in the form of woodcuts in the newspaper L’Illustration at the beginning of the following July, these photographs were realised by an amateur named Thibault, from a point of view overlooking the Rue Saint-Maur-Popincourt, June 25 and 26, before and after the assault. The first photographs reproduced in the press, they show the value of proof given to the medium in the processing of information since the middle of the nineteenth century, well before the development of photomechanical reproduction techniques. The inaccuracies and ghostly traces caused by a long exposure time limit the accuracy lent to the medium. Also the engraver allowed himself to “rectify” the views for the newspaper, adding clouds here and there and specifying the posture or the detail of the silhouettes. The remarkable interest of these daguerreotypes, however, resides in their indeterminate aspect. In fact, they reveal the singular temporality of these events: both short (since each second counts during the confrontations) and at the same time extended (in the moments of preparation and waiting). The temporalities proper to events and photography are thus combined in order to offer the perennial image of an invisible uprising and therefore always in potentiality.

Text from the Jeu de Paume website translated by Google translate

The first photo of an insurrectionary barricade

This photo was taken by a young photographer, by the name of Charles-François Thibault, at the level of no. 92 of the current rue du Faubourg-du-Temple on the morning of Sunday June 25, 1848. The insurrection is coming to an end, and only the last defences of the working-class districts of eastern Paris resist.

Thibault used twice, probably between 7 am and 8 am, his daguerreotype, a primitive process of photography which fixed the image on a metal plate. These two pictures are visible in Parisian museums, the first at the Carnavalet museum, the second (featured image) at the Musée d’Orsay. One distinguishes there in particular a flag planted in the axle of a wheel on the first barricade (which according to the researches of Olivier Ilh [La Barricade reversed, history of a photograph, Paris 1848, Editions du Croquant, 2016] carried the inscription “Democratic and social Republic”) as well as silhouettes of back.

These are the first pictures showing an insurrection and complete barricades. This scene is also regarded as the first photographic illustration of a report in the newspapers, since it was published a few days later in the form of engraving (one could not reproduce at the time directly the daguerreotype in a printed document) in the newspaper L’Illustration, with the caption “The barricade on rue Saint-Maur Popincourt on Sunday morning, from a plate daguerreotyped by M.Thibault.”

Anonymous text. “The first photo of a barricade,” on the Un Jour de Plus a Paris website [Online] Cited 11/11/2021.

On the Rue du Faubourg du Temple in June 1848. The shot is said to be the first photographic illustration of a newspaper report. The scene captured by this famous daguerreotype is the Rue du Faubourg du Temple during the bloody days of June 1848. The picture shows a barricade on an empty street at 7.30am, Sunday 25 June. On the following 8 July the newspaper L’Illustration published two of these shots as woodcuts. Against the backdrop of insurrection, they celebrated the return to order. Yet even though two of Thibault’s plates have been kept at the Orsay Museum, and another at the Carnavalet Museum, little is known about their author. The plates are nevertheless considered to be one of the founding events of the history of photography. Manifestly, the place photographed, the operator’s identity, the motive behind the shot: everything here is indeed enigmatic.

Olivier Ihl. “In the Eye of The Daguerreotype. On the Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple in June 1848.” Abstract. August 2018 on the Researchgate website [Online] Cited 03/02/2023

Unknown photographer (French)

Barricade de la Rue de la Roquette, Place de Bastille

18 March 1871

Albumen print

Album de photographies et d’articles de journaux sur la guerre Franco-Prussienne et la Commune de Paris

Album of photographs and newspaper articles on the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune

1870-1871

Musée Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

CCO Paris Musées / Musee Carnavalet – Histoire de Paris

Commune of Paris

Commune of Paris, also called Paris Commune, French Commune de Paris, (1871), was an insurrection of Paris against the French government from March 18 to May 28, 1871. It occurred in the wake of France’s defeat in the Franco-German War and the collapse of Napoleon III’s Second Empire (1852-70).

The National Assembly, which was elected in February 1871 to conclude a peace with Germany, had a royalist majority, reflecting the conservative attitude of the provinces. The republican Parisians feared that the National Assembly meeting in Versailles would restore the monarchy.

To ensure order in Paris, Adolphe Thiers, executive head of the provisional national government, decided to disarm the National Guard (composed largely of workers who fought during the siege of Paris). On March 18 resistance broke out in Paris in response to an attempt to remove the cannons of the guard overlooking the city. Then, on March 26, municipal elections, organised by the central committee of the guard, resulted in victory for the revolutionaries, who formed the Commune government. Among those in the new government were the so-called Jacobins, who followed in the French Revolutionary tradition of 1793 and wanted the Paris Commune to control the Revolution; the Proudhonists, socialists who supported a federation of communes throughout the country; and the Blanquistes, socialists who demanded violent action. The program that the Commune adopted, despite its internal divisions, called for measures reminiscent of 1793 (end of support for religion, use of the Revolutionary calendar) and a limited number of social measures (10-hour workday, end of work at night for bakers).

With the quick suppression of communes that arose at Lyon, Saint-Étienne, Marseille, and Toulouse, the Commune of Paris alone faced the opposition of the Versailles government. But the Fédérés, as the insurgents were called, were unable to organize themselves militarily and take the offensive, and, on May 21, government troops entered an undefended section of Paris. During la semaine sanglante, or “bloody week,” that followed, the regular troops crushed the opposition of the Communards, who in their defense set up barricades in the streets and burned public buildings (among them the Tuileries Palace and the City Hall [Hôtel de Ville]). About 20,000 insurrectionists were killed, along with about 750 government troops. In the aftermath of the Commune, the government took harsh repressive action: about 38,000 were arrested and more than 7,000 were deported.

“Commune of Paris” 1871 on the Britannica website [Online] Cited 03/02/2023

Bronislaw Malinowski (Polish-British, 1884-1942)

The tasasoria on the beach of Kaulukuba: stepping the masts and getting the sails for the run

Plate from the book Argonauts of the Western Pacific

1915-1916

Gelatin silver print

LSE Library, The British Library of Political and Economic Science

Frederic Ballell (Spanish born Puerto Rico, 1864-1951)

La Rambla. Enllustrador de sabates (La Rambla. Shoeshiner)

1907-1908

© Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona

Federico Ballell Maymí (Spanish, 1864-1951)

Federico Ballell Maymí (Guayama, 1864 – Barcelona, 1951) was a Spanish photojournalist, born in Puerto Rico. …

Work

Photo of the Garcia-Bravo couple April 12, 1913 published in Mundo Gráfico on April 30, 1913 as an advertisement for Capilar Americano distributed at the American Clinic in Barcelona by Juan Garcia-Bravo Menéndez.

Ballell’s photographic work is important due to its volume, the quality of his photographs and the wide range of topics covered. He was one of the founding members of the Barcelona Daily Press Association, where he participated until 1940. The work he did after the 1920s is little known. Reliable information on Ballell is not available again until 1944, when he contacted the Barcelona City Council , concerned about the future of his collection of negatives, which, in July 1945, would end up in the Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona.

His work has been exhibited on various occasions: thus, in April 2000 his first anthology was presented with the title “Frederic Ballell, photojournalist” at the Palacio de la Virreina. The figure of the photographer was presented with a selection of copies of the time to show the different photographic procedures used, in addition a thematic selection was presented again in large enlargements, which allowed showing the great thematic diversity treated by the photographer throughout of his trajectory. The same year a part of his production related to marine disasters was exhibited in the exhibition hall of the Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona with the title “Disaster”, organised by the Photographic Archive of Barcelona. These exhibitions were later exhibited in other places outside of Barcelona.

In 2010, an exhibition of a unique set of photographs was held at the headquarters of the Barcelona Photographic Archive, entitled “Frederic Ballell. La Rambla 1907-1908”. In this exhibition it was possible to see more than one hundred original photographs that offered a vision of La Rambla and the different characters that made it up. In this set of images, Ballell captured the daily evolution of one of the most important communication centres of the early 20th century.

Photographic background

Frederic Ballell’s photographic collection contains a wealth of information on life in Barcelona, mainly in the first quarter of the 20th century. His participation in the important public acts of the moment make him a faithful follower of the evolution of citizen events, both urban and social. His constant presence led him to generate a corpus of some 2,600 photographs published only in Ilustració Catalana and Feminal between 1903 and 1917. Also in the magazine Actualidades since its creation in 1908.

He was a correspondent for Blanco y Negro, Nuevo Mundo, 1 ABC and La Esfera, where we found many images also published in this period.

His collection was acquired between June and July 1945 and the set of negatives entered the Historical Archive of the City of Barcelona. Subsequently, a selection of negatives was made that was taken to be printed in Francisco Fazio’s photographic workshop and made available to the public, those that were not printed were stored in the Archive depository. In 2000, after documentary research and physical conditioning of the negatives and positives, the entire collection was left for public consultation at the Photographic Archive of Barcelona .

Text translated from the Spanish Wikipedia website by Google Translate

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Amazonenstrom-Gebiet (Amazon River area)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4325

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Australian

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4350

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Brazilian Neger

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4324

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Indischer Archipel (Indian archipelago)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4340

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Kaukasien (Caucasian)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4344

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Malaischer Archipel (Malay Archipelago)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4341

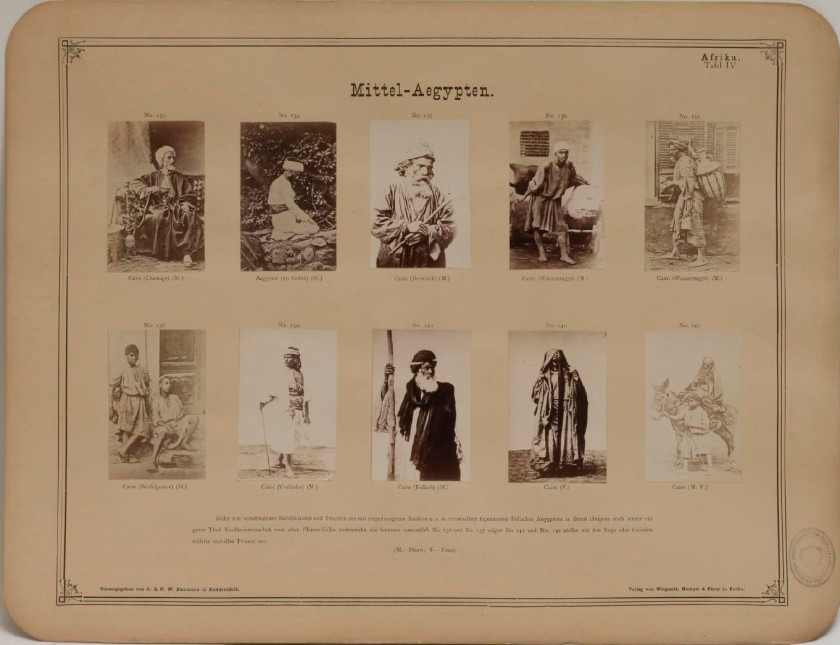

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Mittel-Aegypten (Central Egypt)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4310

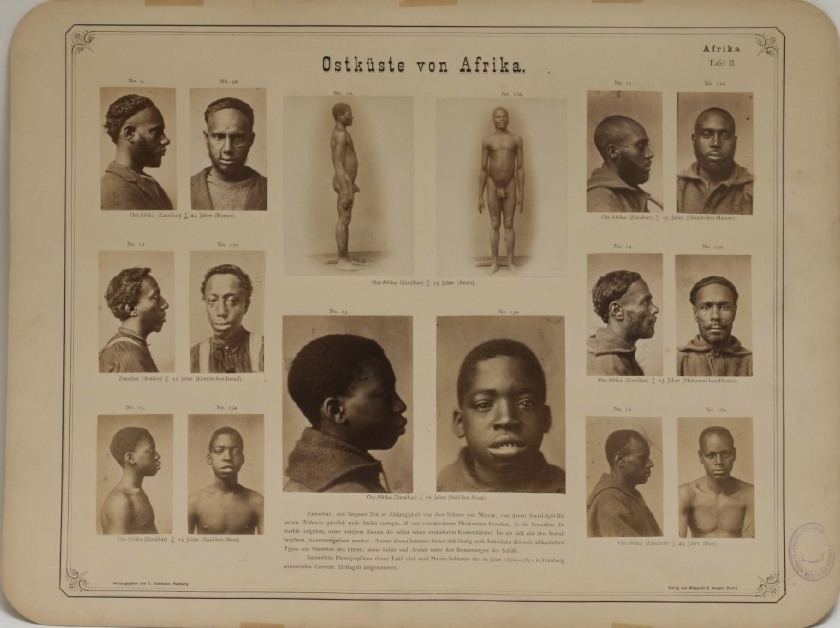

Carl Dammann (German, 1819-1874) publisher

Ostkuste von Afrika (Eastern coast of Africa)

1873-1876

From [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men 1876

Albumen, paper, cardboard

Museo Nacional de Antropologia MNA FD 4308

Carl Dammann

Photographer based in Hamburg

Author of “Ethnological photographic gallery of the various races of men.”

C. Dammann

F.W. Dammann

Collectors of anthropological photographs and some were published in C. & F.W. Dammann, 1876, [Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men, (London: Trubner).

24 pages of plates: illustrations, portraits; 32 x 43cm

Cover title: Races of mankind

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Sabatini Building

Santa Isabel, 52

Nouvel Building

Ronda de Atocha (with plaza del Emperador Carlos V)

28012 Madrid

Phone: (34) 91 774 10 00

Opening hours:

Monday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Tuesday Closed

Wednesday – Saturday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Sunday 12.30am – 2.30pm

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Documentary Genealogies: Photography 1848-1917' at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid showing at left rear, pages from Carl Dammann's '[Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men' 1876 Installation view of the exhibition 'Documentary Genealogies: Photography 1848-1917' at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid showing at left rear, pages from Carl Dammann's '[Races of Mankind]: Ethnological Photographic Gallery of the Various Races of Men' 1876](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2023/02/documentary-genealogies-installation-d.jpg?w=840)

![Mathew B. Brady. 'Untitled [Spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln]' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/matthew-brady-captured-spectators-massing-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand]," from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-b-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. "Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand and mounted cavalry]," in the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-c-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-d-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-e-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-e-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-detail.jpg?w=650&h=464)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-f-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-g-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-g-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-h-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-h-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-i-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-i-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-i-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-j-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-j-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-k-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-k-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner. 'Untitled [Gand Review, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-k-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-l-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-l-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-web.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-whole.jpg?w=840)

![Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail) Alexander Gardner (Scottish-American, 1821-1882) 'Untitled [Gand Review, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' from the folio 'Memories of the War. Illustrations of the Grand Review' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/memories-of-the-war-alexander-gardner-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865 Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/reviewing-stand-web.jpg?w=650&h=644)

![Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865 (detail) Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/reviewing-stand-detail.jpg?w=650&h=644)

![Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865 Mathew B. Brady (born Lake George, NY 1823 - died New York City 1896) 'Untitled [Presidential reviewing stand, Washington, D.C., May, 1865]' 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/07/brady-reviewing-stand.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-63](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-web.jpg?w=840&h=719)

![Unknown '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-63](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-detail.jpg?w=840&h=640)

![Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-web.jpg?w=840&h=573)

![Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-detail.jpg?w=840&h=900)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-web.jpg?w=826&h=1024)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' (detail) October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' (detail) October 4, 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-detail.jpg?w=840&h=611)

![Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/lincoln-mourning.jpg?w=768&h=1024)

![Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp265063-lincoln-memorial-button-web.jpg?w=768&h=1024)

![Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-web.jpg?w=840&h=827)

![Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' (detail) 1862 Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' (detail) 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-detail.jpg?w=840&h=503)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/confederate-with-clown-like-chevrons-closeup-web.jpg?w=840&h=890)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/james-holeman-closeup-web.jpg?w=840&h=975)

![Maker: Unknown (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821–1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Maker: Unknown (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821–1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp274835-murder-web.jpg?w=544&h=1024)

![Unknown, American. '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Unknown, American. '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/broadside-for-the-capture-of-john-wilkes-booth-web.jpg?w=534&h=1016)

![Unknown. '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-62? Unknown. '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-62?](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/39-james-house-web.jpg?w=840&h=975)

![Unknown. '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-62? (detail) Unknown. '[Private James House with Fighting Knife, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee]' 1861-62? (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/39-james-house-detail.jpg?w=840&h=974)

![Unknown. '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861 Unknown. '[Private Thomas Gaston Wood, Drummer, Company H, "Walton Infantry," Eleventh Regiment Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/private-thomas-gaston-wood-web.jpg?w=840&h=921)

![Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Dead Confederate sharpshooter in "The devil's den."]' July 1863 Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Dead Confederate sharpshooter in "The devil's den."]' July 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/gardner-sharpshooter-web.jpg?w=840&h=678)

![Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Antietam, Md. President Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers]' 3rd October 1862 Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Antietam, Md. President Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers]' 3rd October 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/abraham-lincoln-and-generals-web.jpg?w=840&h=673)

![Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Antietam, Md. President Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers]' (detail) 3rd October 1862 Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Antietam, Md. President Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers]' (detail) 3rd October 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/abraham-lincoln-and-generals-detail.jpg?w=840&h=972)

![Timothy H. O'Sullivan (1840-1882). '[Fort Pulaski, Ga. The "Beauregard" gun]' April 1862 Timothy H. O'Sullivan (1840-1882). '[Fort Pulaski, Ga. The "Beauregard" gun]' April 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/big-gun-web.jpg?w=840&h=870)

![Alexander Gardner (1821-1882). '[Richmond, Va. Grave of Gen. J. E. B. Stuart in Hollywood Cemetery, with temporary marker]' Richmond, April-June 1865 Alexander Gardner (1821-1882). '[Richmond, Va. Grave of Gen. J. E. B. Stuart in Hollywood Cemetery, with temporary marker]' Richmond, April-June 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/general-stuart-web.jpg?w=840&h=822)

![James F. Gibson. '[James River, Va. Deck and turret of U.S.S. Monitor seen from the bow (ie. stern)]' 9th July, 1862 James F. Gibson. '[James River, Va. Deck and turret of U.S.S. Monitor seen from the bow (ie. stern)]' 9th July, 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/james-river-va-deck-and-turret-of-uss-monitor-seen-from-the-bow-web.jpg?w=840&h=838)

![Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Washington Navy Yard, D.C. Lewis Payne, the conspirator who attacked Secretary Seward, standing in overcoat and hat]' April 1865 Alexander Gardner (1821-1882) '[Washington Navy Yard, D.C. Lewis Payne, the conspirator who attacked Secretary Seward, standing in overcoat and hat]' April 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/payne-a-web1.jpg?w=834&h=1024)

You must be logged in to post a comment.