Exhibition dates: 14th August – 1st November 2020

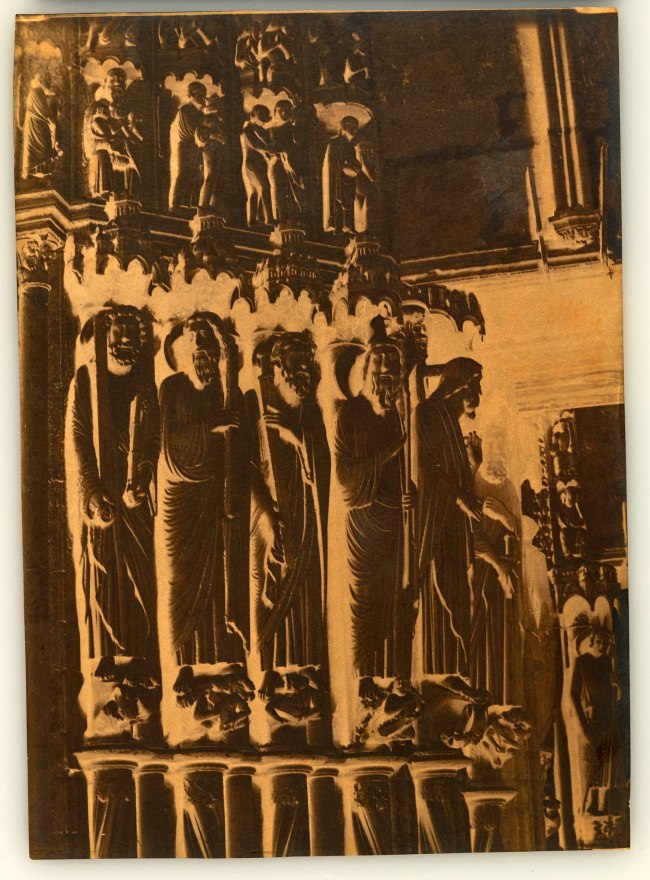

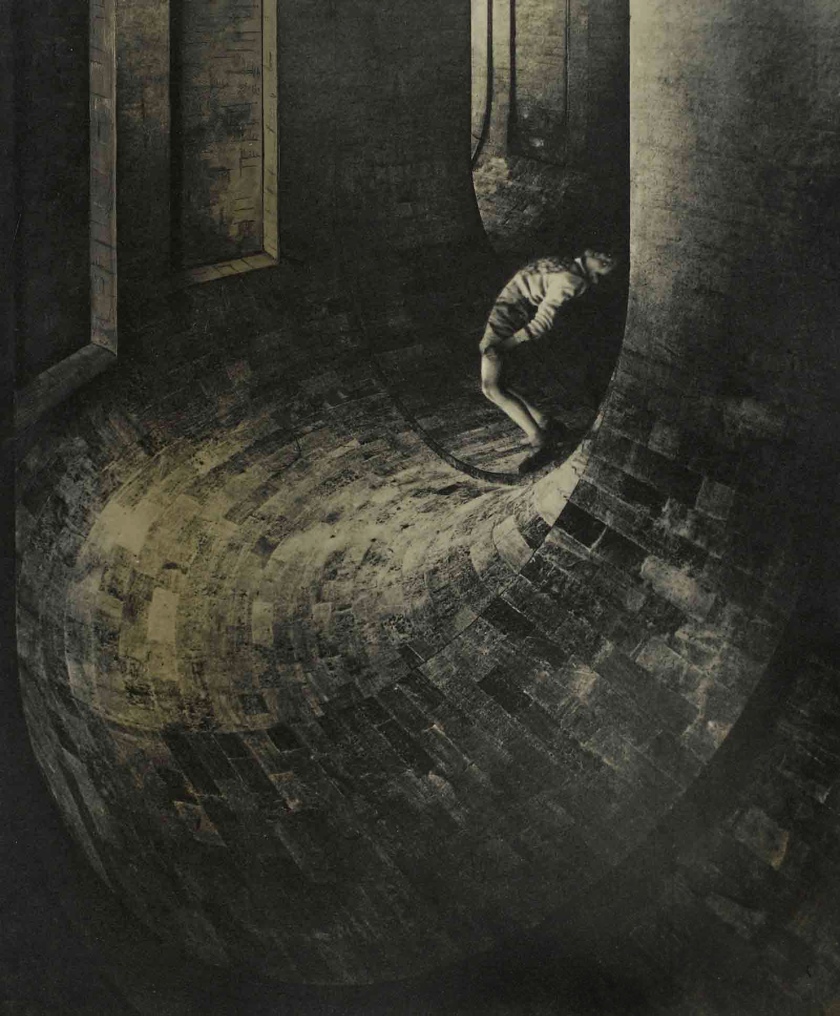

G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT

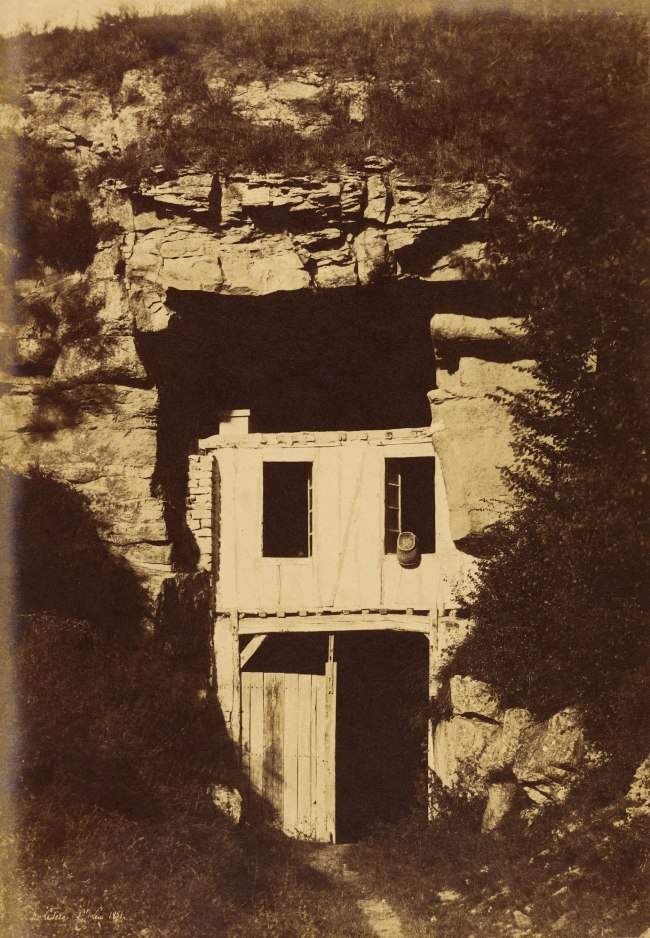

[Taking in the view]

c. 1880

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

While the premise for this exhibition is interesting – that cabinet cards acted as a “primer” for coaxing “Americans into thinking about portraiture as an informal act, forging the way for the snapshot and social media with its contemporary “selfie” culture – in reality, the notion is far fetched.

Of the many millions of cabinet cards produced during their period of proliferation (1880s-1910s), only a small percentage, perhaps as low as 3%, would ever fit the performative type illustrated in this posting. Most were of the “solemn records of likeness and stature type”, typically full-length, half-length or a head and shoulders portrait, usually of a single person, sometimes a couple or family. Even then, the performative type of cabinet card would have a limited distribution, either within the family or commercially.

The four sections of the exhibition – Caught in the Act (actors, orators and other public figures); The Trade (commercial advertising); Sharing Life: Family and Friends (family albums); and Acting Out (people at play; reality and truth) – are logical partitions of these certain types of cabinet card. But what interests me more are the psychological aspects of having ones photograph taken. Why is the person’s photograph being taken, at whose direction (the photographers, the sitters)… who is posing the individual, what do they intend to convey through the image, who decides what that message is and, of course, how does the viewer decipher the message. “The interpretation of a person’s acting out and an observer’s response varies considerably, with context and subject usually setting audience expectations.” (Wikipedia)

Here we must acknowledge that the acting out is not singular but plural, for it is as much an act on the part of the photographer as it is the sitter. How much the outcome is dependent on the “director” or the subject is an act of constant negotiation (and, of course, it is also an outcome of the ritual of production).

The curator John Rohrbach observes that, “In our current moment of ‘selfie’ culture and social media-centered interaction, understanding the history of self-presentation and portraiture is more prescient than ever…” but this statement, linking cabinet cards and selfies, is a very very long bow to draw. This is because cabinet cards are not “selfies” as we perceive them now – informal snapshots taken by the self – but posed and performed photographic studies that require inherent discipline, structure and form constructed by the photographer and the sitter to achieve their end.

I often wonder about the revelatory process of having one’s portrait taken in the early days of photography. I know from texts that I have read that some people found the process slow and irritating, the results unsatisfactory. On the other hand, imagine being made to stand still for several seconds when you are not used to being completely still. Could there possibly be a moment in time and space, of meditation and reconciliation with oneself, a revelation in the stillness of the seconds of exposure. A revelation more spiritual than performative? *Two girls (1864, below)

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Acting

The art or practice of representing a character on a stage or before cameras.

Acting serves countless purposes including the following: It reminds us of times past and forgotten, or gives us a glimpse of a possible future. It portrays our raw, unadulterated, vulnerable, emotional, and at times, ugly, horrifying humanity. It provokes emotion, thought, discussion, awareness, or even imagination.

Acting Out

A child is “acting out” when they exhibit unrestrained and improper actions. The behaviour is usually caused by suppressed or denied feelings or emotions.

Acting out reduces stress. It’s often a child’s attempt to show otherwise hidden emotions. Acting out may include fighting, throwing fits, or stealing. In severe cases, acting out is associated with antisocial behaviour and other personality disorders in teenagers and younger children. …

Acting Out a) represents in action and b) translates into action, expressing (something, such as an impulse or a fantasy) directly in overt behaviour without modification, not complying with social norms.

In the psychology of defence mechanisms and self-control, acting out is the performance of an action considered bad or anti-social. In general usage, the action performed is destructive to self or to others. The term is used in this way in sexual addiction treatment, psychotherapy, criminology and parenting. In contrast, the opposite attitude or behaviour of bearing and managing the impulse to perform one’s impulse is called acting in.

The performed action may follow impulses of an addiction (e.g. drinking, drug taking or shoplifting)[citation needed]. It may also be a means designed (often unconsciously or semi-consciously) to garner attention (e.g. throwing a tantrum or behaving promiscuously). Acting out may inhibit the development of more constructive responses to the feelings in question. …

Interpretation

The interpretation of a person’s acting out and an observer’s response varies considerably, with context and subject usually setting audience expectations.

Alternatives

Acting out painful feelings may be contrasted with expressing them in ways more helpful to the sufferer, e.g. by talking out, expressive therapy, psychodrama or mindful awareness of the feelings. Developing the ability to express one’s conflicts safely and constructively is an important part of impulse control, personal development and self-care.

Anonymous. “Acting out,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 04/10/2020

G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT

[Taking in the view] (detail)

c. 1880

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Howie, Detroit, MI

George Moore and Fred Howe

1890s

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

Fred Howe, the Fatman and George Moore, the living skeleton; they are the most comical boxers in the world. Fred Howe’s father was a carpenter at Alleghany City, Penn., and Fred started to learn the same trade, but soon became too fat. At the age of eighteen he joined the Forepaugh Circus as a “tat boy,” and there met his present sparring partner.

George Moore was born in Helena, Montana, where his father had a little dry goods shop. Until he was twenty-one years of age George worked in his father’s shop. But his greatest desire was to see the world. When the fist big circus came to Helena, the manager offered him an engagement to exhibit himself as the “living skeleton,” and he closed with the offer at once. Fred Howe, they soon became great friends. The doctors advised both to take as much exercise as possible – the one to gain flesh, and the other to get rid of it. These smart Yankee lads then resolved to combine duty with pleasure, so they went in for boxing. For a long time they practised privately. One day, however, the manager was told of the fun by some of his “freaks,” who had been allowed to see a set-to” between the two gladiators. The manager then arranged a round or two, and the moment he saw Howe and Moore face each other, he offered them a long engagement at an increased salary, if only they would do their boxing before the public. Today these funny fellows are not only expert boxers, but also perfect comedians in their “art.” Their boxing is uproariously funny.

Moore is 6ft. 3in. in height, and weighs but 97lb., Howe is only 4ft. 2in. high, and weights exactly 422lb.

The Strand Magazine

Howie, Detroit, MI

George Moore and Fred Howe (detail)

1890s

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

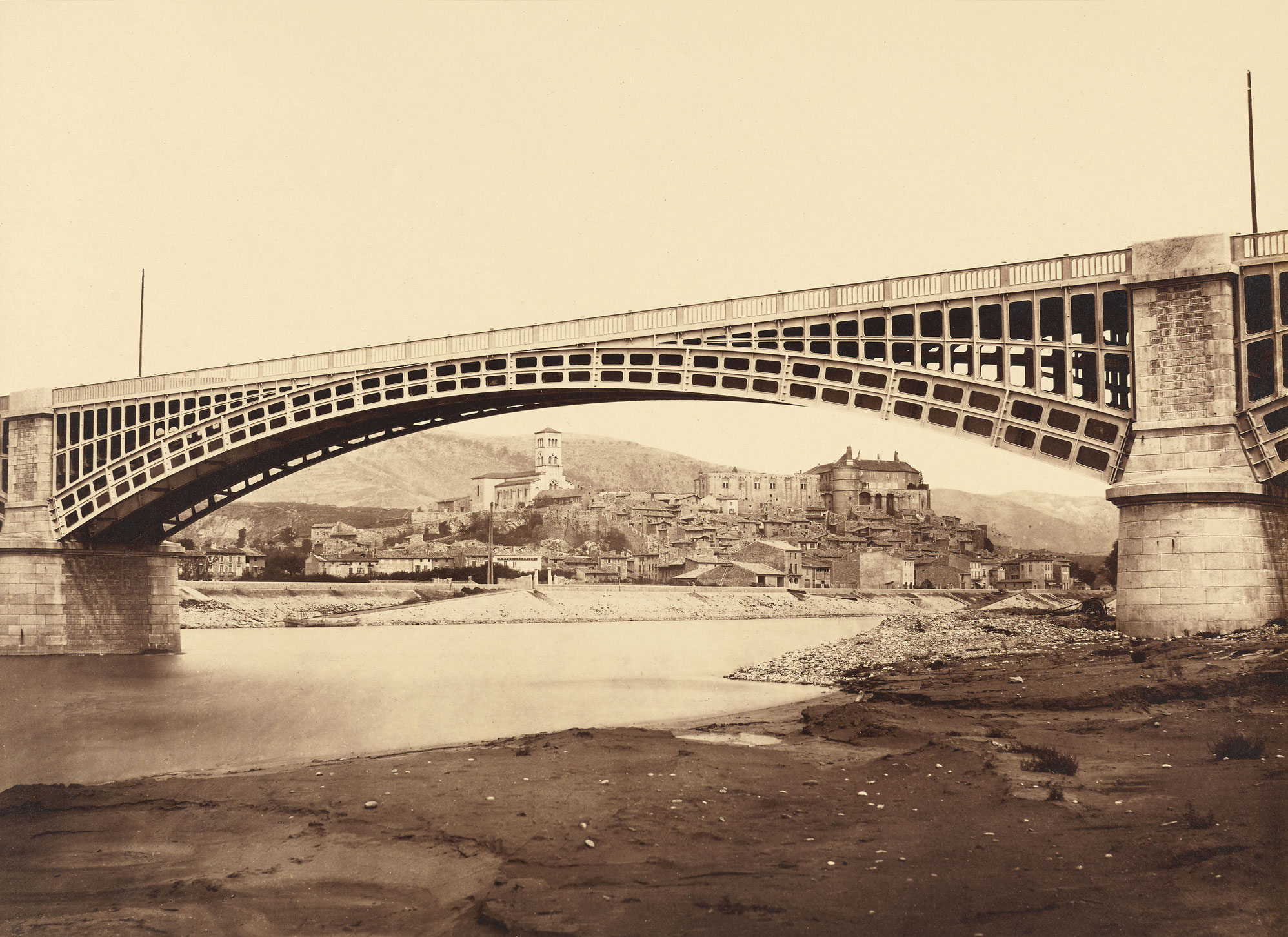

Alfred U. Palmquist (Swedish, 1850-1922) and Peder T. Jurgens, St. Paul, MN

[Skater]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

The Swede Alfred U. Palmquist (1850-1922) immigrated to America in 1872. In 1874, together with the Norwegian Peder T. Jurgens he opened the photo studio Palmquist & Jurgens in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Alfred Palmquist was born in Finland to Swedish parents on June 21, 1850. We know nothing about his childhood and upbringing except that he emigrated to Minnesota in the United States at the age of twenty-two. A year later, he and a colleague started a photo studio in Saint Paul, Minnesota, which was named Palmquist & Lake.

Ten years later, in 1883, Palmquist entered into a collaboration with Peder T. Jurgens. We only know about his partner Jurgens that he was Norwegian and had previously supported himself as an economist. Peder Jurgens worked in the company between the years 1882 to 1888. The new company was then of course named Palmquist & Jurgens and lived on until the beginning of the 20th century. During the 1870s and 1880s, most photographers worked in their studios… Palmquist & Jurgens was such a typical photography company that preferred people to come to their studio to be photographed. The company had specialised in photographing famous families in Saint Paul.

M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT

[Getting the cleaver]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT

[Getting the cleaver] (detail)

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT

[Getting the cleaver] (detail)

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT

[Getting the saw]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography offers the first-ever in-depth examination of the photographic phenomenon of cabinet cards. Cabinet cards were America’s main format for photographic portraiture through the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Inexpensive and sold by the dozen, they transformed getting one’s portrait made from a formal event taken up once or twice in a lifetime into a commonplace practice shared with family and friends.

Building on the museum’s history as a leader in American photography, this exhibition reveals how photography studios and their sitters across the United States introduced immediacy to studio portraiture and transformed their sessions into avenues of fun and personal expression. Sections will trace the cabinet card’s development and evolution, from its beginnings in celebrity culture through the marketing and advertising innovations of practitioners to the diversity of what people brought to their sittings. Not only did Americans embrace photography as a commonplace fact of life during these years, they openly played with the medium’s believability. In short, cabinet cards made photography modern.

This August, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art will present Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography, an exhibition offering the first in-depth examination of the nineteenth-century photographic phenomenon of cabinet cards. Charting the proliferation of this under appreciated photographic format, Acting Out reveals that cabinet cards coaxed Americans into thinking about portraiture as an informal act, forging the way for the snapshot and social media with its contemporary “selfie” culture. Acting Out presents hundreds of photographs – many on view publicly for the first time – from collections nationwide, including examples from the Carter’s own extensive photography collection. On view August 18 through November 1, 2020, the exhibition is organised by the Carter and will travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, cabinet cards gave birth to the golden age of photographic portraiture in America. Measuring 6 1/2 by 4 1/4 inches, roughly the size of the modern-day smartphone screen, they were three times larger than the period’s leading photographic format. This larger size revealed previously obscured details in the images captured, encouraging action-ready gestures and the introduction of an astonishing array of props. Where photographs had once functioned as solemn records of likeness and stature, cabinet cards offered a new outlet for entertainment and remembering life’s everyday moments.

Acting Out investigates how this new performative medium prompted sitters to become far more comfortable with having their portrait made. By the time Eastman Kodak introduced its new affordable Brownie camera in 1900, cabinet cards had primed Americans to photograph every aspect of their lives. Though produced over 100 years ago, cabinet cards have a familiarity and a levity that resonates with our experience of photography today.

“Acting Out exemplifies the Carter’s commitment to organising exhibitions rooted in groundbreaking scholarship, a core tenet of our curatorial philosophy,” stated Andrew J. Walker, Executive Director. “This exhibition harnesses the resources of our vast photography collection and archive to show visitors the contemporary relevance of the medium’s pre-modern history.”

The exhibition is organised into four sections chronicling the birth and evolution of the cabinet card:

Caught in the Act: Actors, orators, and other public figures were among the first to embrace cabinet cards. This section examines how the creative innovations employed by New York photographer Napoleon Sarony and his cohorts built public enthusiasm for a new kind of photographic portraiture founded on a relaxed sense of immediacy that influenced studio photographers across America.

The Trade: This section looks at the entertaining and evocative ways that photographers worked to overcome low prices and fierce competition, and to stand out from their peers. Their creative solutions gave rise to the ubiquity of cabinet cards across America by the 1880s.

Sharing Life: Family and Friends: Over the last quarter of the nineteenth century, cabinet cards were often the favoured means for recording and celebrating family life. This evocative section reveals the ways in which cabinet cards established a model for family albums as channels for sharing and boasting of the joys and transits of life.

Acting Out: If portraiture was the ostensible subject of cabinet cards, play was just as important. This section examines Americans’ acceptance of the camera as a tool for shared amusement as they toyed with photography’s pretence of reality and truth.

“In our current moment of ‘selfie’ culture and social media-centered interaction, understanding the history of self-presentation and portraiture is more prescient than ever,” said John Rohrbach, Senior Curator of Photographs at the Carter. “This exhibition reveals how nineteenth-century Americans approached photography far more playfully than ever before, a transformation that forever shifted our relationship to the medium.”

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography was organised by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The exhibition is supported in part by the Alice L. Walton Foundation Temporary Exhibitions Endowment and accompanied by a 232-page catalogue co-published with the University of California Press, Berkeley. The book is the first dedicated to the history of the cabinet card and features colour plates of 100 cards at their actual size. Contributors include Dr. John Rohrbach, Senior Curator of Photographs at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art; Dr. Erin Pauwels, Assistant Professor of American Art at Temple University; Dr. Britt Salvesen, Department Head and Curator of the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and Fernanda Valverde, Conservator of Photographs at the Carter.

Press release from the Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Unknown photographer

[Chess against myself]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Unknown photographer

[Chess against myself] (detail)

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Hatch and White, Burlington, WI

[Man in woman’s clothing]

c. 1891

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

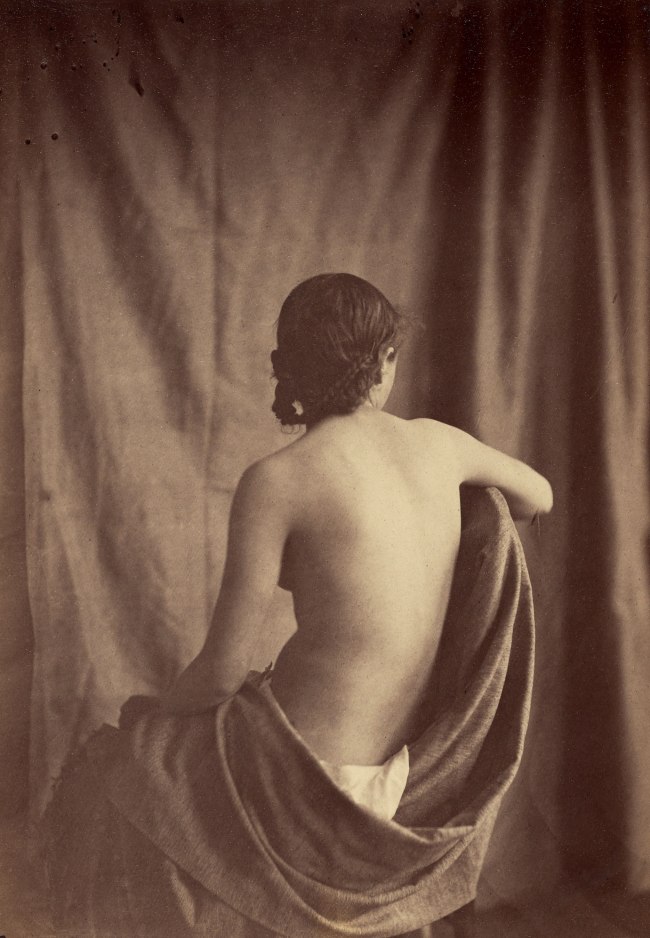

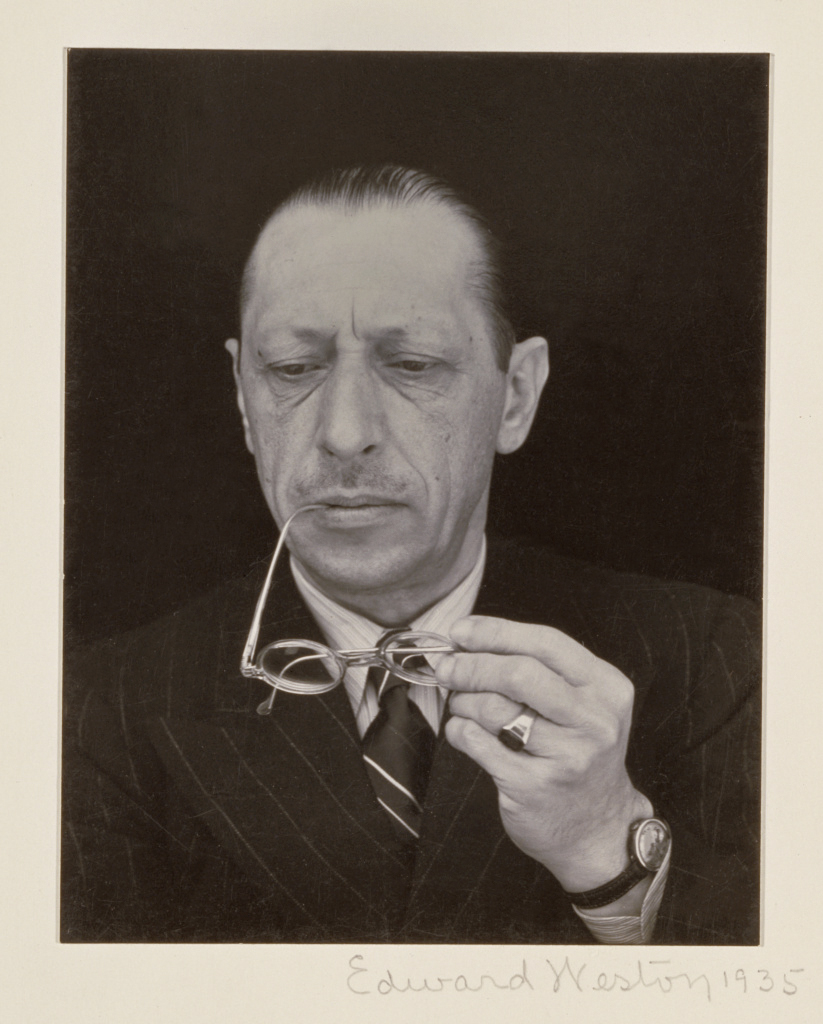

Benjamin J. Falk, New York, NY

Helena Luy

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Benjamin J. Falk (American, 1853-1925)

When Napoleon Sarony died in 1896, Benjamin J. Falk ascended to the first place in the world of performing arts photography…

Falk’s contemporaries, who spoke primarily of the clarity, verisimilitude, and composure of his images, never recognised his greatest power as a portraitist. Falk was a man of extraordinary erotic engagement with his sitters, and the intensity of his attention becomes visible only when one sees the entirety of his work envisioning one of the several women – Belle Archer, Mrs. James Brown Potter, Cleo De Merode, Cissy Fitzgerald, Amy Busby, the Barrison Sisters – who capture his imagination. He was capable of refracting the sitter’s beauty in a tremendous array of scenes, costumes, and attitudes, doing so without making the images seem artificial.

When asked in 1893 what was most important in creating effective portraits, he replied matter of factly, “I name expression, posing and lighting in the order as they appear to be most important. The technique of the profession being absolutely under the control of the operator since the introduction of the dry plates, there is no excuse now for any but perfect photographic results. I have always made my price high enough, so that I did not have to consider the cost of material while doing my work.” The camera, in the proper hands, is, in many ways, a finer art tool to-day than the chisel or the brush, although, like them, it has its limitations.

Specialty

The first strong adherent of artificial light sources in the studio, Benjamin Falk created portraits that were among the most dramatically sculptural looking images of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Possessed of a playful visual wit, he often experimented with his images, using curious juxtapositions, unusual poses, and lighting highlights to convey distinctiveness of personality. Increasingly indifferent to painted backdrops, he did many portraits against blank walls or bleached out backcloths. He began the fashion for faces and figures suspended in a milky white ground that became ubiquitous shortly after 1900.

Anonymous. “Benjamin J. Falk,” on the Broadway Photographers website [Online] Cited 05/09/2020

Benjamin J. Falk, New York, NY

Helena Luy (detail)

1880s

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

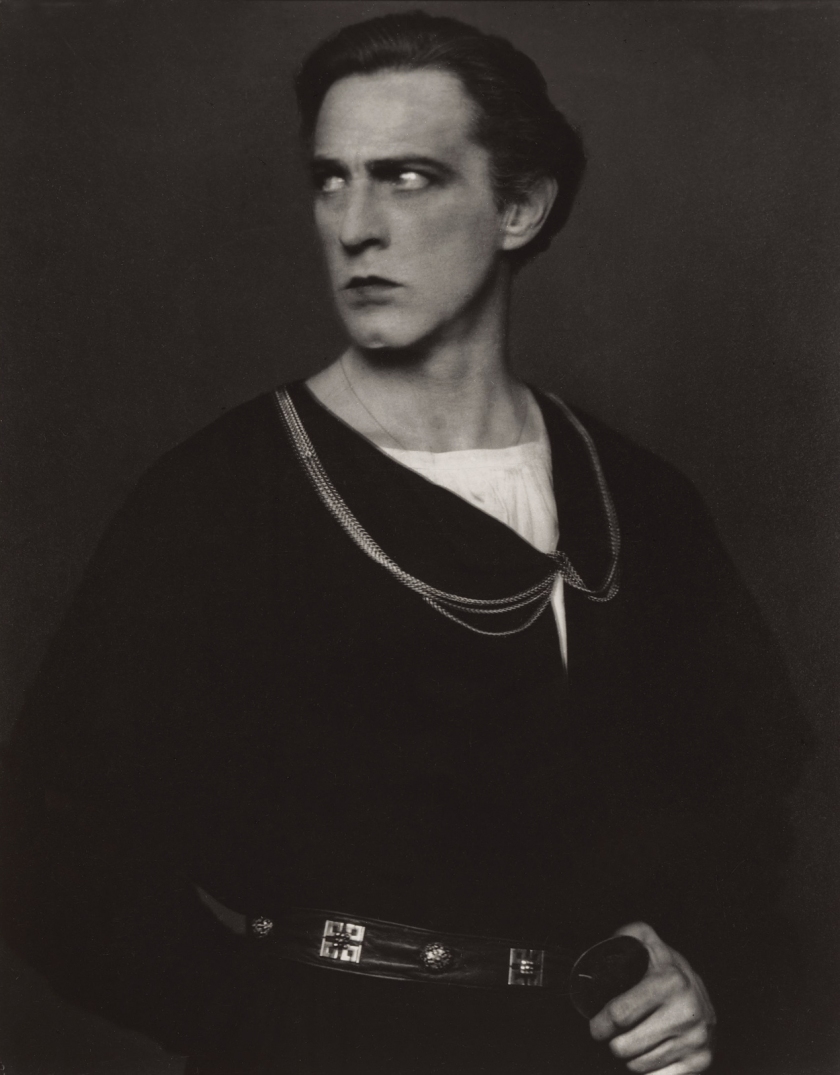

Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY

[Fanny Davenport]

c. 1870

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Napoleon Sarony (American, 1821-1896)

Napoleon Sarony (March 9, 1821 – November 9, 1896) was an American lithographer and photographer. He was a highly popular portrait photographer, best known for his portraits of the stars of late-19th-century American theatre. His son, Otto Sarony, continued the family business as a theatre and film star photographer.

Sarony was born in 1821 in Quebec, then in the British colony of Lower Canada, and moved to New York City around 1836. He worked as an illustrator for Currier and Ives before joining with James Major and starting his own lithography business, Sarony & Major, in 1843. In 1845, James Major was replaced in Sarony & Major by Henry B. Major, and the firm continued operating under that name until 1853. From 1853 to 1857, the firm was known as Sarony and Company, and from 1857 to 1867, as Sarony, Major & Knapp. Sarony left the firm in 1867 and established a photography studio at 37 Union Square, during a time when celebrity portraiture was a popular fad. Photographers would pay their famous subjects to sit for them, and then retain full rights to sell the pictures. Sarony reportedly paid the internationally famous stage actress Sarah Bernhardt $1,500 to pose for his camera, equivalent to $42,683 in 2019. In 1894, he published a portfolio of prints entitled “Sarony’s Living Pictures”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY

[Fanny Davenport] (detail)

c. 1870

Albumen silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Fanny Lily Gipsey Davenport (English-American, 1850-1898)

Fanny Lily Gipsey Davenport (April 10, 1850 – September 26, 1898) was an English-American stage actress. The eldest child of Edward Loomis Davenport and Fanny Elizabeth (Vining) Gill Davenport, Fanny Lily Gypsey Davenport was born on April 10, 1850 in London.

Most of her siblings were actors, including Harry Davenport. She was brought to the United States in 1854 and educated in the Boston public schools. At age 7, she appeared at Boston’s Howard Athenæum as Metamora’s child, but her real debut occurred in February 1862 when she portrayed King Charles in Faint Heart Never Won Fair Lady at Niblo’s Garden.

In February 1862, she appeared in New York City at Niblo’s Garden at the age of 12 as the King of Spain in Faint Heart Never Won Fair Lady. From 1869 to 1877, she performed in Augustin Daly’s company; and afterwards, with a company of her own, acted with especial success in Sardou’s Fédora (1883) her leading man being Robert B. Mantell, Cleopatra (1890), and similar plays. She took over emotional Sardou roles that had been originated in Europe by Sarah Bernhardt. Her last appearance was at the Grand Opera House in Chicago on March 25, 1898, shortly before her death.

Her first husband was Edwin B. Price, an actor. They married on July 30, 1879, and divorced on June 8, 1888. On May 18, 1889, she married her leading man, Melbourne MacDowell. Both marriages were childless. Davenport died September 26, 1898, from an enlarged heart, at her summer home in Duxbury, Massachusetts.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown photographer

[Two girls]

1864

Albumen silver print (carte de visite)

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Unknown photographer

[Two girls] (detail)

1864

Albumen silver print (carte de visite)

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

A. M. Nikodem, Chicago, IL

[Cat]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

A.M. Nikodem

According to Origin, Growth, and Usefulness of the Chicago Board of Trade: Its Leading Members, and Representative Business Men in other Branches of Trade (1885): “Miss A.M. Nikodem, Photographic Artist. No. 701 West Madison Street. – One of the most popular and finely appointed photographic studios in Chicago is that conducted by Miss A.M. Nikodem, who succeeded Mr. M. T. Baldwin one year ago. This lady, who is regarded as one of the most skilful and accomplished photographic artists in the city, occupies an entire two-storied building completely equipped with all modern improvements and appliances and her elegantly furnished parlours are the resort of the élite of Chicago. Miss Nikodem is the only lady in the city who give personal attention to the taking of pictures, etc., and having had an extended practical and theoretical training she has attained a marked perfection in her art. In social circles Miss Nikodem occupies a prominent position both as a skilful artist and estimable lady, while in the business world she is held in high esteem as an enterprising and capable woman.”

Nikodem occupied the studio at this address from 1885-1891, and then moved to another location. 1895 is the last year in which she seems to be listed in Chicago city guides. Despite her prominence, photographs from her studio are exceptionally uncommon. Nikodem’s skill is fully on display in this portrait. The three or four other examples of her work we could find, all in library special collections, are all of women or girls, and they display a uniform artistic excellence and technical photographic skill.

W. A. White, Wilson, KS

My first baby friend Tompie and his pet

1896

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

W. A. White, Wilson, KS

My first baby friend Tompie and his pet (detail)

1896

Collodion silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, IA

[Baby]

1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Unknown photographer

[Painter]

1890s

Albumen silver print

William L. Schaeffer Collection

Unknown photographer

[Painter] (detail)

1890s

Albumen silver print

William L. Schaeffer Collection

Charles L. Griffin, Scranton, PA

[Toddler with dog]

c. 1892

Gelatin silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

F. J. Nelson, Anoka, MN

Domestic Bread

c. 1890s

Collodion silver print

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Gilbert G. Oyloe (American, 1851-1927) Ossian, IA

[Woman]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson Collection

Oyloe had a studio in Ossian during the 1880’s and 1890’s.

James F. Ryder, Cleveland, OH

Verso

1880s

Planographic print

Gift of Robert E. Jackson

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Charles Quartley, Baltimore, MD

[Church woman]

1880s

Albumen silver print

Robert E. Jackson

Caroline Bergman, Louisville, KY

Untitled [Bergman’s Photograph Gallery]

c. 1890

Relief print

Gift of Robert E. Jackson

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Louise and Caroline Bergman

Louis Bergman opened a Louisville photo studio in 1872 on W Market. After 1885, however, Caroline Bergman (his wife) is listed as the proprietor and photographer, and Louis is listed only as “manager”. This very successful studio was in operation until 1896.

Louis Bergman’s … studio was located at 56 & 58 Market Street, in Louisville, Kentucky. Perusal of Louisville business directories reveals that Bergman began business with a partner. Bergman & Flexner; the firm was listed in the 1868 and 1869 directories. He was reported to be the sole proprietor of a studio from 1872 until 1886. Bergman was listed at a number of different addresses over these years. Using these addresses, it appears that this particular photograph was taken between 1873 and 1881. From 1886 through 1894 the proprietor of the studio became Caroline Bergman. The Photographic Times and American Photographer (1883) reported that Bergman was Vice President of the Photographers Mutual Benefit Society of Louisville. Louis Bergman (c. 1838 -?) was born in Hanover, Germany to Prussian parents. His wife, Carrie (1845 -?) was born in Louisiana to German parents. The couple married in about 1865. The Bergman’s had a daughter, Lillie, who was 12 years-old at the time of the 1880 census. The census listed Louis as a photographer and Carrie as a homemaker. It is interesting to note that when the couples daughter reached 18 years of age, Carrie became the studio’s proprietor / photographer.

Anonymous. “Man with a Great Beard in Louisville, Kentucky,” on The Cabinet Card Gallery website 03/01/2012 [Online] Cited 05/09/2020

R. O. Helsom, Menomonie, WI

Verso

1880s

Relief print

Gift of Robert E. Jackson

Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Cabinets

c. 1880s

Celluloid-covered album

Robert E. Jackson Collection

Amon Carter Museum of American Art

3501 Camp Bowie Boulevard

Fort Worth, TX 76107-2695

Opening hours:

Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday:

10am – 5pm

Thursday: 10am – 8pm

Sunday: 12am – 5pm

Closed Mondays and major holidays

![G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT. '[Taking in the view]' c. 1880 G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT. '[Taking in the view]' c. 1880](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/g.-s.-smith-salt-lake-city-ut-taking-in-the-view-ca.-1880-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas.jpg?w=650&h=985)

![G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT. '[Taking in the view]' c. 1880 (detail) G. S. Smith, Salt Lake City, UT. '[Taking in the view]' c. 1880 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/g.-s.-smith-salt-lake-city-ut-taking-in-the-view-ca.-1880-albumen-silver-print-detail.jpg?w=650&h=750)

![Alfred U. Palmquist and Peder T. Jurgens, St. Paul, MN. '[Skater]' 1880s Alfred U. Palmquist and Peder T. Jurgens, St. Paul, MN. '[Skater]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/alfred-u.-palmquist-and-peder-t.-jurgens-st.-paul-mn-skater-1880s-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth.jpg?w=650&h=980)

![M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/m.-c.-hosford-west-rutland-vt-getting-the-cleaver-1880s-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p.jpg?w=650&h=976)

![M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s (detail) M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/m.-c.-hosford-west-rutland-vt-getting-the-cleaver-1880s-detail1.jpg?w=840)

![M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s (detail) M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the cleaver]' 1880s (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/m.-c.-hosford-west-rutland-vt-getting-the-cleaver-1880s-detail2.jpg?w=840)

![M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the saw]' 1880s M. C. Hosford, West Rutland, VT. '[Getting the saw]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/m.-c.-hosford-west-rutland-vt-getting-the-saw-1880s-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p2016.jpg?w=650&h=979)

![Unknown photographer. '[Chess against myself]' 1880s Unknown photographer. '[Chess against myself]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-chess-against-myself-1880s-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p2016.101.jpg?w=650&h=961)

![Unknown photographer. '[Chess against myself]' 1880s (detail) Unknown photographer. '[Chess against myself]' 1880s (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-chess-against-myself-1880s-detail.jpg?w=650&h=725)

![Hatch and White, Burlington, WI. '[Man in woman's clothing]' c. 1891 Hatch and White, Burlington, WI. '[Man in woman's clothing]' c. 1891](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/hatch-and-white-burlington-wi-man-in-womans-clothing-ca.-1891-collodion-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth.jpg?w=650&h=972)

![Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY. '[Fanny Davenport]' c. 1870 Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY. '[Fanny Davenport]' c. 1870](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/napoleon-sarony-new-york-ny-fanny-davenport-ca.-1870-albumen-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p201.jpg?w=650&h=973)

![Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY. '[Fanny Davenport]' c. 1870 (detail) Napoleon Sarony, New York, NY. '[Fanny Davenport]' c. 1870 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/napoleon-sarony-new-york-ny-fanny-davenport-c.-1870-detail.jpg?w=650&h=636)

![Unknown photographer. '[Two girls]' 1864 Unknown photographer. '[Two girls]' 1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-two-girls-1864-albumen-silver-print-carte-de-visite-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p1976.jpg?w=650&h=1021)

![Unknown photographer. '[Two girls]' 1864 (detail) Unknown photographer. '[Two girls]' 1864 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-two-girls-1864-albumen-silver-print-carte-de-visite-detail.jpg?w=650&h=631)

![A. M. Nikodem, Chicago, IL. '[Cat]' 1880s A. M. Nikodem, Chicago, IL. '[Cat]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/a.-m.-nikodem-chicago-il-cat-1880s-albumen-silver-print-robert-e.-jackson-collection.jpg?w=650&h=987)

![W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, IA. '[Baby]' 1890s W. A. Wilcoxon, Bonaparte, IA. '[Baby]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/w.-a.-wilcoxon-bonaparte-ia-baby-1890s-collodion-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p2019.11.jpg?w=650&h=982)

![Unknown photographer. '[Painter]' 1890s Unknown photographer. '[Painter]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-painter-1890s-albumen-silver-print-william-l.-schaeffer-collection.jpg?w=650&h=977)

![Unknown photographer. '[Painter]' 1890s (detail) Unknown photographer. '[Painter]' 1890s (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/unknown-photographer-painter-1890s-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Charles L. Griffin, Scranton, PA. '[Toddler with dog]' c. 1892 Charles L. Griffin, Scranton, PA. '[Toddler with dog]' c. 1892](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/charles-l.-griffin-scranton-pa-toddler-with-dog-ca.-1892-gelatin-silver-print-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas.jpg?w=650&h=973)

![Gilbert G. Oyloe (American, 1851-1927) Ossian, IA. '[Woman]' 1880s Gilbert G. Oyloe (American, 1851-1927) Ossian, IA. '[Woman]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/gilbert-g.-oyloe-ossian-ia-woman-1880s-albumen-silver-print-robert-e.-jackson-collection.jpg?w=650&h=977)

![Charles Quartley, Baltimore, MD. '[Church woman]' 1880s Charles Quartley, Baltimore, MD. '[Church woman]' 1880s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/charles-quartley-baltimore-md-church-woman-1880s-albumen-silver-print-robert-e.-jackson-collection.jpg?w=650&h=988)

![Caroline Bergman, Louisville, KY. 'Untitled [Bergman's Photograph Gallery]' c. 1890 Caroline Bergman, Louisville, KY. 'Untitled [Bergman's Photograph Gallery]' c. 1890](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/09/caroline-bergman-louisville-ky-ca.-1890-relief-print-gift-of-robert-e.-jackson-amon-carter-museum-of-american-art-fort-worth-texas-p.jpg?w=650&h=981)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal12-web.jpg?w=650&h=800)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal21-web.jpg?w=650&h=821)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

![Unknown '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' 1861-63](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-web.jpg?w=840&h=719)

![Unknown '[The Pattillo Brothers (Benjamin, George, James, and John), Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry]' (detail) 1861-63](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/patillo-brothers-close-up-detail.jpg?w=840&h=640)

![Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-web.jpg?w=840&h=573)

![Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s Maker: Unknown '[Civil War Portrait Lockets]' (detail) 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp273827-lockets-detail.jpg?w=840&h=900)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' October 4, 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-web.jpg?w=826&h=1024)

![Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' (detail) October 4, 1862 Alexander Gardner (American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821-1882 Washington, D.C.;) '[President Abraham Lincoln, Major General John A. McClernand (right), and E. J. Allen (Allan Pinkerton, left), Chief of the Secret Service of the United States, at Secret Service Department, Headquarters Army of the Potomac, near Antietam, Maryland]' (detail) October 4, 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp248329-abraham-lincoln-detail.jpg?w=840&h=611)

![Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/lincoln-mourning.jpg?w=768&h=1024)

![Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865 Maker: Unknown, American; Photography Studio: After, Brady & Co., American, active 1840s–1880s '[Mourning Corsage with Portrait of Abraham Lincoln]' (detail) Photograph, corsage April 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp265063-lincoln-memorial-button-web.jpg?w=768&h=1024)

![Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862 Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-web.jpg?w=840&h=827)

![Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' (detail) 1862 Maker: Unknown '[Game Board with Portraits of President Abraham Lincoln and Union Generals]' (detail) 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp269309-chess-board-detail.jpg?w=840&h=503)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[Confederate Sergeant in Slouch Hat]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/confederate-with-clown-like-chevrons-closeup-web.jpg?w=840&h=890)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862 Unknown photographer (American) '[James A. Holeman, Company A, "Roxboro Grays," Twenty-fourth North Carolina Infantry Regiment, Army of Northern Virginia]' 1861-1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/james-holeman-closeup-web.jpg?w=840&h=975)

![Maker: Unknown (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821–1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865 Maker: Unknown (American; Alexander Gardner, American, Glasgow, Scotland 1821–1882 Washington, D.C.; Photography Studio: Silsbee, Case & Company, American, active Boston) '[Broadside for the Capture of John Wilkes Booth, John Surratt, and David Herold]' April 20, 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/dp274835-murder-web.jpg?w=544&h=1024)

![Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865 Unknown, American. '[Decapitated Man with Head on a Platter]' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/unknown-american-decapitated-man-with-head-on-a-platter-c-1865.jpg?w=840)

![Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-59 Franck-François-Genès Chauvassaignes (French, 1831 - after 1900) 'Untitled [Female Nude in Studio]' 1856-59](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/chauvassaignes_seated-nude-web.jpg?w=838&h=1024)

![Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-54 Eugène Durieu (French, 1800-1874) 'Untitled [Seated Female Nude]' 1853-54](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/durieu_nude_ph8976-web.jpg?w=704&h=1024)

![Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855 Charles Alphonse Marlé (French, 1821 - after 1867) 'Untitled [Standing Male Nude]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/marle_standing-male-nude-web.jpg?w=701&h=1024)

![Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850 Félix-Jacques-Antoine Moulin (French, 1800 - after 1875) 'Untitled [Two Standing Female Nudes]' c. 1850](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/moulin_two-nudes-standing-web.jpg?w=811&h=1024)

![Julien Vallou de Villeneuve (French, 1795-1866) '[Reclining Female Nude]' c. 1853](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/julien-vallou-de-villeneuve-reclining-female-nude.jpg?w=840)

![Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959 - 1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987 Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959 - 1989) 'Untitled [Two Men in Silhouette]' c. 1987](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/16_morrisroe_untitled-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

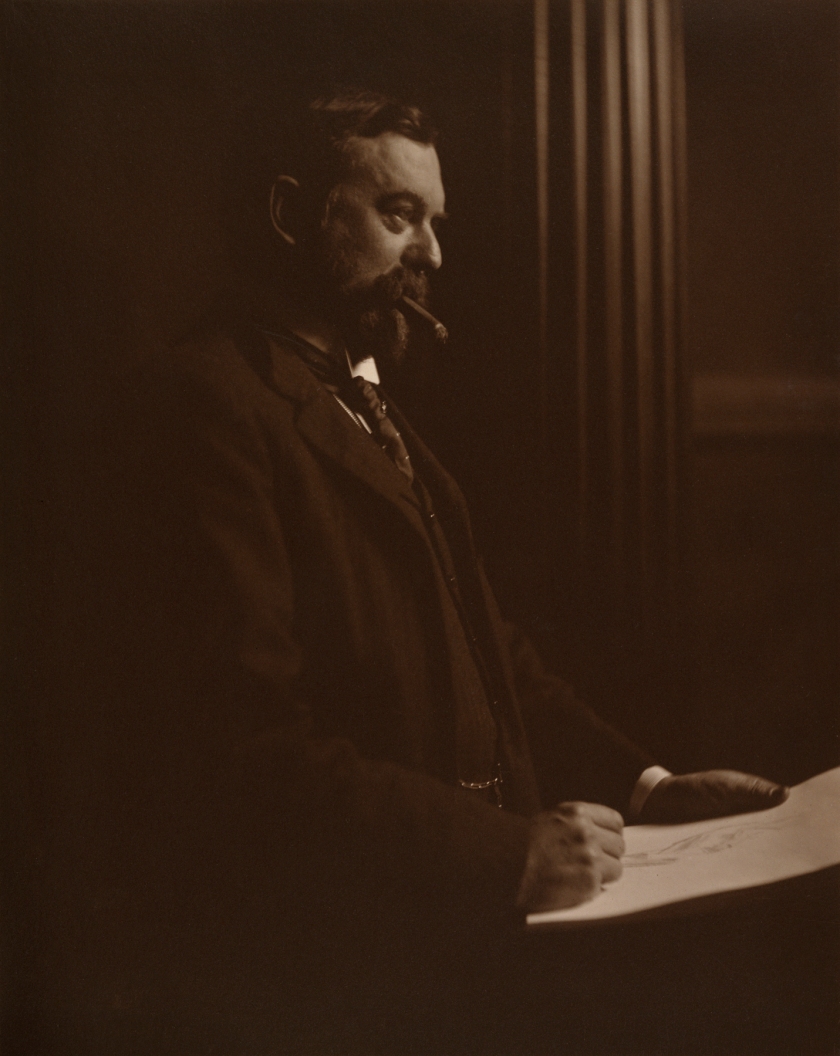

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=840)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=807&h=1024)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=840)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=840)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=840)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=840&h=1007)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=840)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=840)

![Carleton Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[Solar Eclipse]' January 1, 1889](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/carleton-watkins-solar-eclipse.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.