Exhibition dates: 3rd October – 30th December 2022

Curator: Thomas O’Callaghan, Image Specialist for Spanish Art, National Gallery of Art, Department of Image Collections

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

Panorama of Ávila

c. 1870

Albumen silver photograph

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Another eclectic posting… this time, wonderful early photographs of the people and places of Spain.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Rafael Garzón Rodríguez (1863-1923, photographer)

Retablo (Altar) by F. de Borgoña, Capilla Real, Granada

c. 1890

Gelatin silver DOP photograph

Granada: Rafael Garzón (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

A distant land celebrated for its fusion of cultures, Spain in the time of John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) fascinated many. As railroads began crisscrossing the sun-drenched countryside, more visitors could reach more places. Artists like Sargent went to explore: he studied works by Spanish masters, viewed architecture and gardens – with their rich blend of influences, and encountered a land and people that fuelled his creative imagination. A craze for all things Spanish ensued, especially in the United States, where many Spanish artworks entered private collections.

A vibrant visual culture emerged in Spain as commercial photographers such as Juan Laurent established studios that catered to the influx of visitors. As this imagery was collected and dispersed, it entered the popular imagination and defined the region in ways that still influence us today. These materials – the period postcards, fine photographs, and albums – allow us to see Spain as Sargent did, from its landscapes, architecture, and art to its music, dance, and costumes.

Photography and Travel in Sargent’s Spain draws upon photographs and printed matter in the Department of Image Collections of the National Gallery of Art Library. This exhibition is held in conjunction with Sargent and Spain.

Organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington

This exhibition is curated by Thomas O’Callaghan, Image Specialist for Spanish Art, National Gallery of Art, Department of Image Collections.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

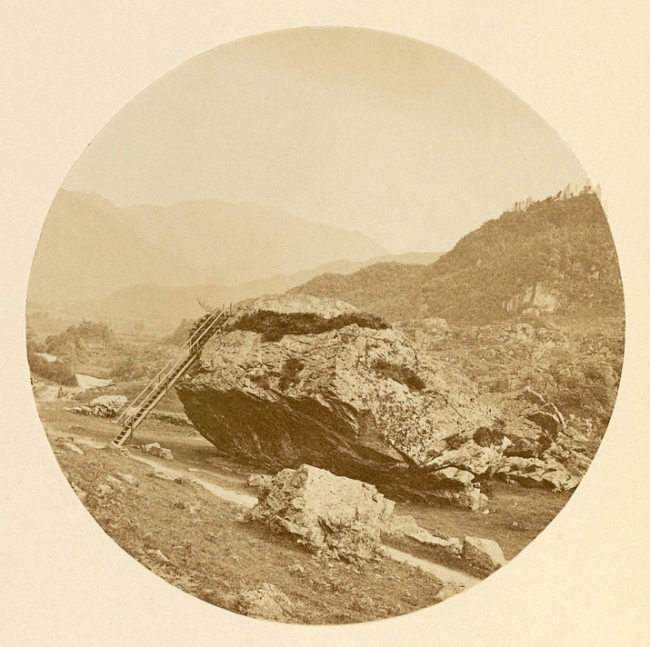

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

Tudela to Bilbao: Logroño Railway Station

1865

Albumen silver photograph

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

The Compañia de Ferrocarril de Tudela a Bilbao began construction of this railway line in northern Spain in 1857 and finished it in 1863. Two years later, the company commissioned Juan Laurent to document the newly completed line. Laurent photographed the iron tracks, viaducts and rural stations, including this view of the Logroño station, during the two-month-long project that culminated in a final presentation album for the company. With the arrival of the first railroads in Spain in 1848, the Spanish writer Modesto Lafuente (1806-1866) observed: “There is poetry in the little stations where a slow train stops for a long time, on a scorching summer morning; the sun fills everything and blinds the distances; everything is still; some birds sing in the acacias in front of the station; down the lonely, dusty road, a solitary carriage makes for the town, which stands out for its pointed bell tower with a black slate roof. Those other stations near the old cities have poetry, to which on Sunday afternoons, during the twilight, the girls go out for a walk and wander slowly along the platform, arm in arm, peering curiously at the passengers from other places inside the cars. Finally, the arrival of the train, at dawn, at a station in the provincial capital has poetry; after the first moment of arrival, the travellers who were waiting comfortably amid a profound silence, the snort of the locomotive is once again heard; a long voice sounds; the train starts moving again; and there, in the distance, in the darkness of the night, in these dense and deep hours of the morning, the dim, mysterious flicker of the little lights that shine in the sleeping city can be glimpsed: an old city, with narrow alleys, with a vast cathedral, with a dilapidated inn, into which now, rousing the waiter from his drowsiness, a newly arrived traveler is about to enter, while we ride the train away through the black countryside, contemplating the flickering of those little lights that lose themselves and arise anew, and end up completely disappearing.” (quoted in José Martínez Ruiz (Azorín), Castilla, Editorial Biblioteca Nueva, 1912, pp. 37-38)

Juan Laurent, noted French photographer, established a studio in Madrid in 1856. He is recognised for his architectural and landscape scenes of Spain and Portugal as well as his extensive documentation of the collections of the Prado Museum and the Royal Armory in Madrid. By the 1860s he was the proprietor of Laurent y Cia, the largest photographic publishing house in Spain. Laurent’s prints and albums were marketed to a wealthy clientele through his gallery in Paris and distributed in England by Marion & Co. of London. (Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 2, pp. 829-830).

This mounted photograph may have been sold from one of Laurent’s sales outlets for inclusion in an album. Laurent later commercialised this image in stereoscopic view and large format.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Joseph Lacoste (1872 – c. 1930, photographer)

Albumen silver photograph of Diego Velázquez’s Prince Baltasar Carlos on Horseback (1635-1636)

1900/1915

Madrid: J. Lacoste (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Baltasar Carlos gallops through the rolling Guadarrama mountain landscape near Madrid with an aristocratic bearing befitting a crown prince of the Spanish empire. Starting with the shocks of the empire’s dissolution, however, Spanish intellectuals of the 1860s and 1890s embraced Velázquez and Goya for being the first artists to paint the natural landscape of Castille. For these scholars, the arid landscape revealed the very heart of Spanish identity. Moreover, it was the key to Spain’s revitalisation, especially after the heartbreaking losses of the Spanish-American War of 1898. As a result of the newfound reclamation, the Spanish reformed Free Institution of Education (ILE) began emphasising the study of landscape painting and scientific disciplines like geography and geology. In addition, it encouraged the students to make excursions into nature. Likewise, it offered new art history courses that celebrated Velázquez and Goya for significantly including the Guadarrama mountains of central Spain in their paintings.

Joseph Jean Marie Lacoste y Borde was a French-born photographer who moved to Spain in 1894. He took over Laurent y Cía. from Juan Laurent’s stepdaughter Catalina Dosch de Roswag in 1900, and ran it up to the First World War, when he was drafted by the French armed forces. During the time he ran the company, he was, like Juan Laurent before him, an important photographer at the Museo del Prado. Many early Prado catalogues are printed with Lacoste images. Though he now controlled all the old Laurent negatives of the museum’s collections, Lacoste photographed the collections again, using the new gelatin dry plate process for his negatives. The dry plate process more faithfully rendered the true colours of the paintings in the scale of grey values than the old collodion wet plate process. The collodion process reproduced reds in nature, for example, as dark grey, even black. The smaller scale of this photograph as well as the more faithful reproduction of grey values suggest that it was printed from a gelatin negative made by Lacoste sometime after 1900.

Juan Laurent, noted French photographer who resided in Spain for 43 years, established a studio in Madrid in 1856. He is recognised for his architectural and landscape scenes of Spain and Portugal as well as his extensive documentation of the collections of the Prado Museum and the Royal Armory in Madrid. By the 1860s he was the proprietor of Laurent y Cia, the largest photographic publishing house in Spain. Laurent’s prints and albums were marketed to a wealthy clientele through his gallery in Paris and distributed in England by Marion & Co. of London. (Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 2, pp. 829-830).

This rare photograph is from A222, vol. 6. (loose photographs only). The six volumes comprising A222 have photographs of paintings, sculpture, architecture, archeological sites, streetscapes and landscapes of Italy and elsewhere on the “Grand Tour.” 514 are mounted in albums, and 59 are individually matted. Of these 59, many, like this albumen silver print of the Velázquez painting in the Prado, are dry-stamped “J. Lacoste – Madrid”, and two (of Murillo paintings) are dry-stamped with an interlaced J L & C monogram, which was an earlier iteration used by the Lacoste company.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Charles Mauzaisse (1823-1885, photographer)

The Court of the Lions, Alhambra, Granada

1862

Albumen silver photograph

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

The Nasrid sultan Muhammad V (died 1391) conceived the Court of the Lions in his Garden Palace in the Alhambra as a paradisal garden, with sunken flowerbeds and waterways symbolising the rivers of Paradise, and pillars representing palm trees growing in an oasis. The court with its alabaster fountain supported by twelve stone lions taken from a Caliphal palace in Córdoba has become synonymous with the Alhambra.

Charles Mauzaisse was a French painter and the son of a painter. He emigrated to Spain in 1857 and signed the visitors’ log at the Alhambra on the 29th of January. After a peripatetic period traveling through southern Spain, he settled in Granada permanently, becoming one of the city’s few foreigners to become a local professional photographer. As a portrait photographer, he offered his clientele their likenesses on oilcloth, paper, glass, and ivory. He soon expanded his repertoire to views of the city and its architectural monuments, especially the Alhambra, catering to foreign visitors’ whims and custom requests and the booming tourist trade. In 1862, he returned from a visit to France with the latest advances in the photographic field.

From this date to the beginning of the 1880s, he made many photographs. However, their dispersal has left scant remnants in public collections. The Royal Palace in Madrid owns an album with 40 of Mauzaisse’s photos. He dedicated it to María de las Mercedes de Orleans y Bórbon on her marriage in 1878 to King Alfonso XII of Spain. Mauzaisse’s photography conjoined with his activity as a painter. Art deeply entered him as the son of Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse (1784-1844), a prolific if minor French artist. By 1870, Charles established himself as a painter as well as a photographer in the Alhambra. He reportedly maintained close contact with French artists like Henry Regnault (1843-1871), whom he entertained on his way to Morocco. Recent research has shown that Gustave Doré used photos by Mauzaisse as the basis for his engraved illustrations in several publications.

In July 1871, Mauzaisse photographed the Fortuny-Madrazo family in the Alhambra when they gathered in Granada to celebrate the birth of Fortuny’s son, Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo. Unfortunately, Charles Mauzaisse may have died in the cholera epidemic that swept through Andalucía in 1885.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

The Palace of Monserrate, Sintra, Portugal

1869

Albumen silver photograph

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

“Sargent swept over America in a cloud of glory, and the dust never settled; it was stirred up even more, eagerly anticipating his return when he left for Spain. He wrote to Mrs. Gardner from Madrid (16 June [1903]), ‘I am leaving Madrid for Portugal and out of the way places and am not likely to be back for three weeks or a month’.” (Stanley Olson, John Singer Sargent: His Portrait, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2001, p. 227)

Architect James Knowles designed this eclectic palace in 1858 for Francis Cook, the 1st Viscount of Monserrate, a wealthy British textile merchant, industrialist, and great art collector. Knowles modified an existing Neo-Gothic mansion built in the late 18th century on the ruins of an ancient chapel and added a curious mixture of Neo-Manueline, Neo-Mudéjar, Neo-Mughal, and Neo-Renaissance design elements. The result is an example of the innovative Romantic architecture that thrived in Sintra. The Portuguese court established a luxurious summer retreat in Sintra with views of the Atlantic from the cool foothills north of Lisbon. In 1809, the poet Byron visited the site of the future palatial villa and published his impressions of its natural beauty in his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Francis Cook installed a large botanical garden on the property that is still renowned for its diverse and exotic plants and trees. In the Laurent photo, the tops of Araucaria conifers native to Chile rise in the lower left corner.

Juan Laurent, noted French photographer, established a studio in Madrid in 1856. He is recognised for his architectural and landscape scenes of Spain and Portugal as well as his extensive documentation of the collections of the Prado Museum and the Royal Armory in Madrid. By the 1860s he was the proprietor of Laurent y Cia, the largest photographic publishing house in Spain. Laurent’s prints and albums were marketed to a wealthy clientele through his gallery in Paris and distributed in England by Marion & Co. of London. (Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 2, pp. 829-830).

The collodion glass negative used to print this photograph is in the Ruiz Vernacci photo archive in the Spanish Culture Ministry in Madrid; VN-06923.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

The Fountain of Narcissus, Garden of the Prince, Palace of Aranjuez

c. 1880s

Albumen silver photograph printed from a Gramstorff collodion negative

Boston: Soule later Gramstorff Art Publishing (firm) copying 1863 photograph by J. Laurent

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

This small nineteenth-century albumen print is from the Gramstorff Collection. The department of image collections also has the collodion glass plate negative used to print it (Gramstorff 5754). The Soule (later Gramstorff) Art Publishing Company of Boston (active 1859 – c. 1906) was a purveyor of art, architecture, and topographical photographs specialising in Europe and the American West. The Soule Company acquired original photos from American and European art publishers and then copied them in their Boston workrooms for distribution in the United States. This small-format photograph is a copy by Soule of a larger albumen photograph by the Juan Laurent company of Madrid and Paris. However, the Madrid company may not have authorised Soule’s copies of original Laurent photographs for sale in the United States.

Photographers during this period followed murky standards, and John Soule appears to have been no exception, publishing images by other American photographers without crediting them. The Laurent company found it necessary to file a legal injunction to remedy a piracy case in Cádiz in 1883. Glass negative 5754, like many others in the Gramstorff Collection, is double printed with the same image.

Juan Laurent, noted French photographer who resided in Spain for 43 years, established a studio in Madrid in 1856. He is recognised for his architectural and landscape scenes of Spain and Portugal as well as his extensive documentation of the collections of the Prado Museum and the Royal Armory in Madrid. By the 1860s he was the proprietor of Laurent y Cia., the largest photographic publishing house in Spain. Laurent’s prints and albums were marketed to a wealthy clientele through his gallery in Paris and distributed in England by Marion & Co. of London. (Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, vol. 2, pp. 829-830).

During Laurent’s 1863 photographic campaign in Aranjuez, he remembered that earlier French travel writers had considered the gardens of the royal palace there particularly lovely. In 1855, author Antoine de Latour described the palace as the ‘Versailles of Madrid’ and its gardens as spring oases. In his photo of the Garden of the Prince, Laurent seems to signal its similarity with French palace gardens.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

Patio of the Acequia in the Generalife, Granada

c. 1881

Albumen silver photograph

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

The narrow rectangular canal (acequia) with water jets pictured in this photograph was one of the primary conduits for the Alhambra’s water supply. The Nasrids, after diverting water from the Darro River six kilometres away, brought it by aqueduct to the Generalife, the summer palace in the cool woods above the Alhambra. From its entry point in the Generalife, the water fell to the main complex of palaces, buildings, and gardens below. The system was a marvel of Arab hydraulic engineering.

Text from the National Gallery of Art Library

Casiano Alguacil Blázquez (1832-1914, photographer)

Inhabitants of Toledo

c. 1880s

in Spain: Toledo, Cordova, Granada, Seville, Valencia, Barcelona (1879/1894?), plate 23 from first of two albums of 189 albumen silver photographs

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Casiano Alguacil Blázquez (1832-1914, photographer)

Inhabitants of Toledo

c. 1880s

in Spain: Toledo, Cordova, Granada, Seville, Valencia, Barcelona (1879/1894?), plate 24 from first of two albums of 189 albumen silver photographs

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Casiano Alguacil Blázquez (1832-1914, photographer)

Inhabitants of Toledo

c. 1880s

in Spain: Toledo, Cordova, Granada, Seville, Valencia, Barcelona (1879/1894?), plate 25 from first of two albums of 189 albumen silver photographs

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Casiano Alguacil Blázquez (1832-1914, photographer)

Inhabitants of Toledo

c. 1880s

in Spain: Toledo, Cordova, Granada, Seville, Valencia, Barcelona (1879/1894?), plate 58 from first of two albums of 189 albumen silver photographs

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Juan Laurent (1816-1886, photographer)

Inhabitants of Quero, Toledo Province

1878

in Burgos, Madrid, Toledo, Escorial, Cordoba y Sevilla (1878/1890), plate 58 from album of 103 albumen silver photographs

Madrid: J. Laurent (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

T. E. Mott (active 1910s – 1920s, photographer)

John Singer Sargent’s “El Jaleo” (1882) in the Spanish Cloister, Fenway Court

c. 1922

Gelatin silver DOP photograph from an album of 55 views of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Boston: Thomas E. Mott & Son (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

J. E. Purdy (1859-1933, photographer)

John Singer Sargent

1903

Cabinet card-mounted gelatin silver DOP photograph

Boston: J. E. Purdy (firm)

National Gallery of Art Library, Department of Image Collections

Hertzmann Collection of Photographs of American Artists

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nude-models-posing-for-a-painting-class-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-photographing-olga-in-a-garden-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-amida-buddah-web.jpg?w=650&h=858)

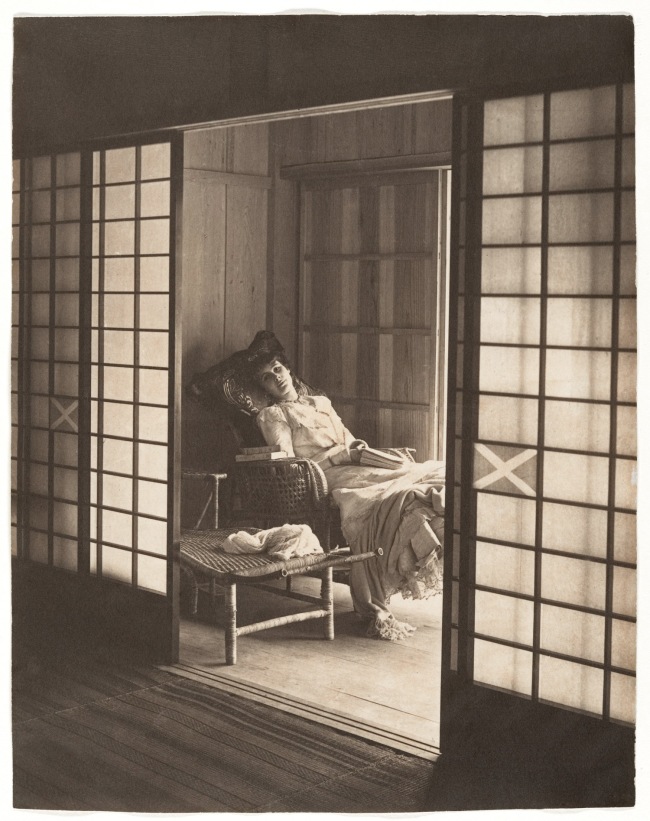

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-view-through-the-window-of-a-garden-web.jpg?w=840)

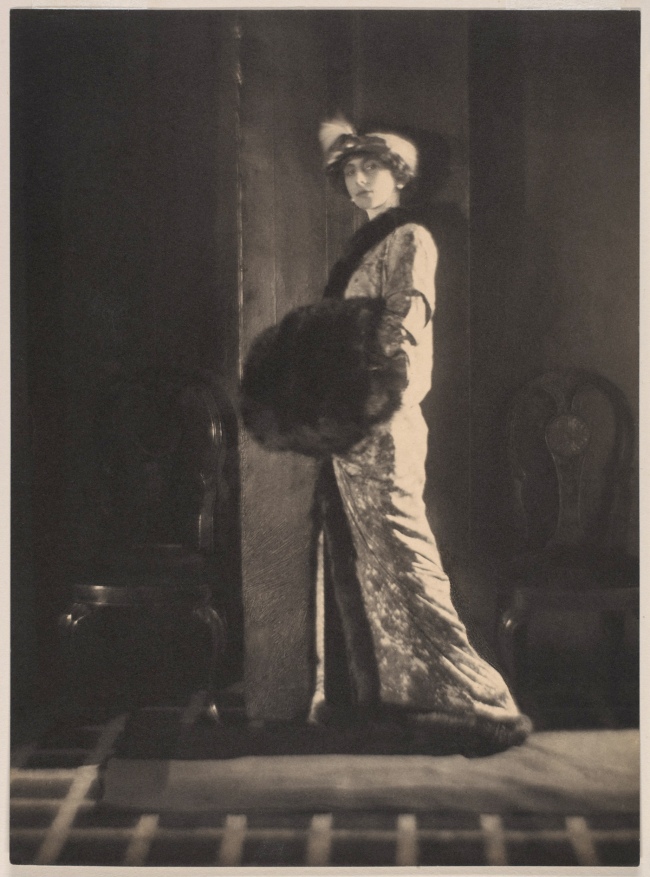

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-lady-ottoline-morrell-web.jpg?w=650&h=871)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-dance-study-web.jpg?w=840)

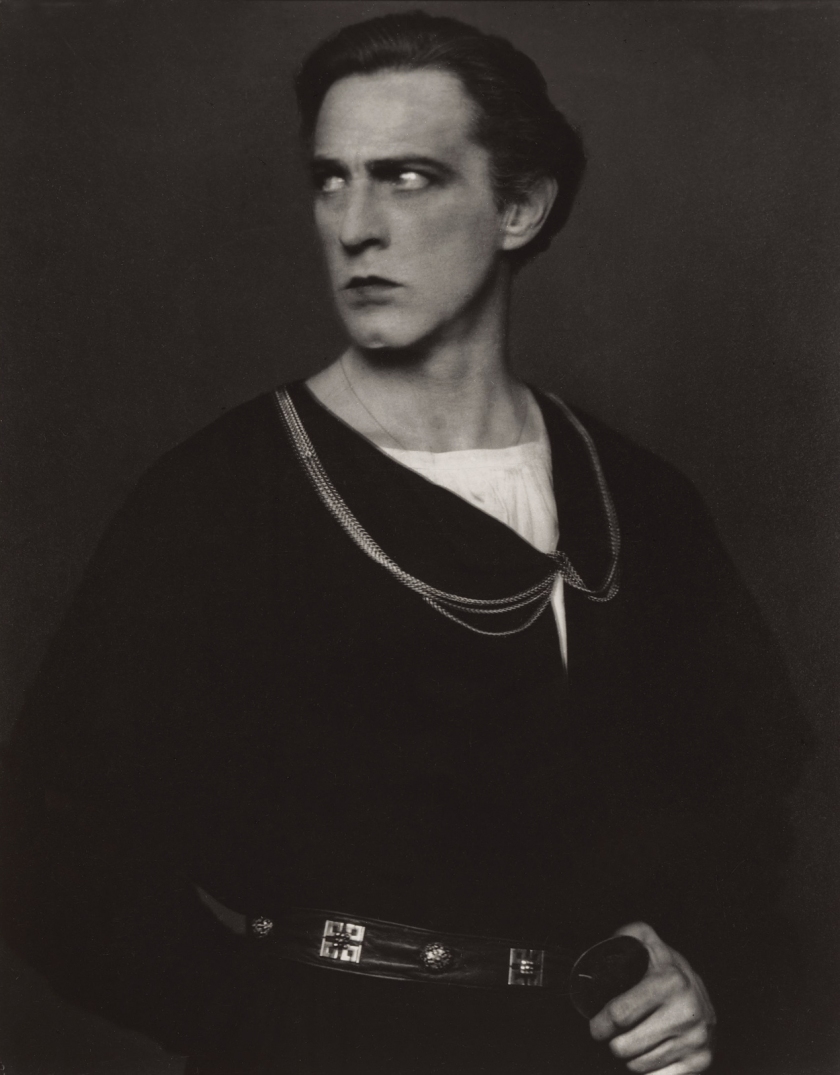

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-portrait-of-vaslav-nijinski-1912-web.jpg?w=650&h=847)

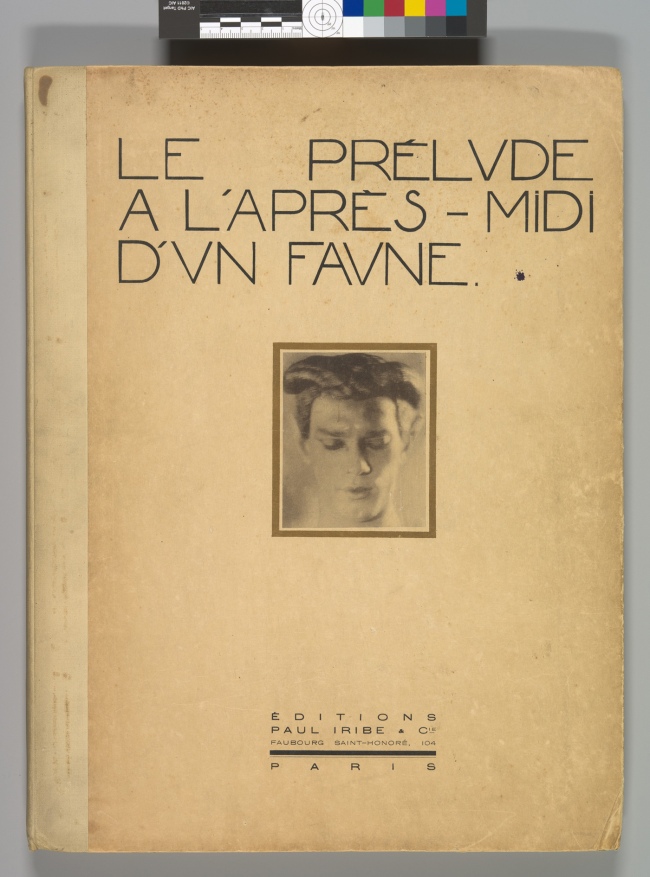

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nijinsky-plate-from-le-prelude-acc80-laprecc80s-midi-dun-faune-web.jpg?w=650&h=1045)

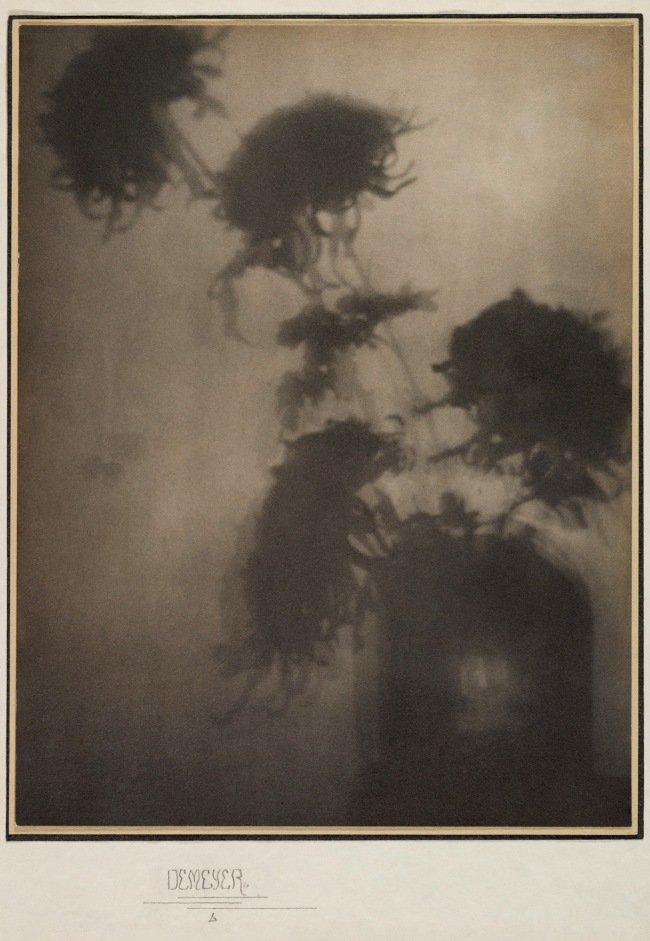

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-image-from-prelude-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-study-for-vogue-web.jpg?w=650&h=829)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-etienne-de-beaumont-web.jpg?w=650&h=824)

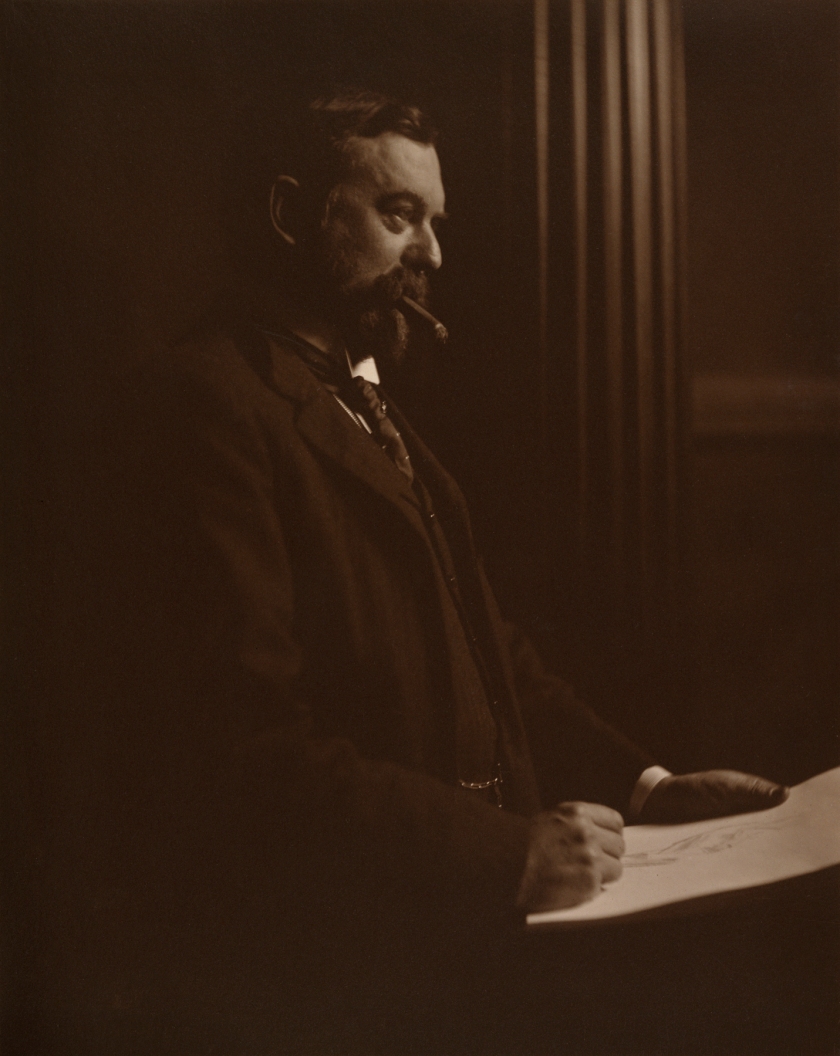

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/sears-adolf-de-meyer-web.jpg?w=650&h=824)

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=840)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=807&h=1024)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=840)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=840)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=840)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=840&h=1007)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=840)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.