Exhibition dates: 11th May – 25th September 2016

Curators: Dr Carol Jacobi, Curator of British Art 1850-1915 at Tate Britain, and Dr Hope Kingsley, Curator, Education and Collections, Wilson Centre for Photography, with Tim Batchelor, Assistant Curator at Tate Britain

Peter Henry Emerson (British, 1856-1936)

Haymaker with Rake

c. 1888, published 1890

From Pictures of East Anglian Life portfolio

Photogravure on paperImage: 277 x 196mm

Victoria and Albert Museum

Gift from the photographer

An interesting concept for an exhibition. I would have liked to have seen the exhibition to make a more informed comment. Parallels can be drawn, but how much import you put on the connection is up to you vis-à-vis the aesthetic feeling and formal construction of each medium. It is fascinating to note how many of the original art works are photographs with the painting following at a later date, or vice versa. Photographically, Julia Margaret Cameron and John Cimon Warburg are the stars.

Photographs have always been used by artists as aide-mémoire since the birth of photograph. Eugené Atget called his photographs of Paris “Documents pour artistes”, declaring his modest ambition to create images for other artists to use as source material … but I take that statement with a pinch of salt. Perhaps a salt print from a calotype paper negative!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Tate for allowing me to publish the art work and photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Tate Britain presents the first major exhibition to celebrate the spirited conversation between early photography and British art. It brings together photographs and paintings including Pre-Raphaelite, Aesthetic and British impressionist works. Spanning 75 years across the Victorian and Edwardian ages, the exhibition opens with the experimental beginnings of photography in dialogue with painters such as J.M.W. Turner and concludes with its flowering as an independent international art form.

Stunning works by John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, JAM Whistler, John Singer Sargent and others will for the first time be shown alongside ravishing photographs by pivotal early photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron, which they inspired and which inspired them.

John Everett Millais (English, 1829-1896)

The Woodman’s Daughter

1850-51

Oil paint on canvas

889 x 648mm

Guildhall Art Gallery, City of London

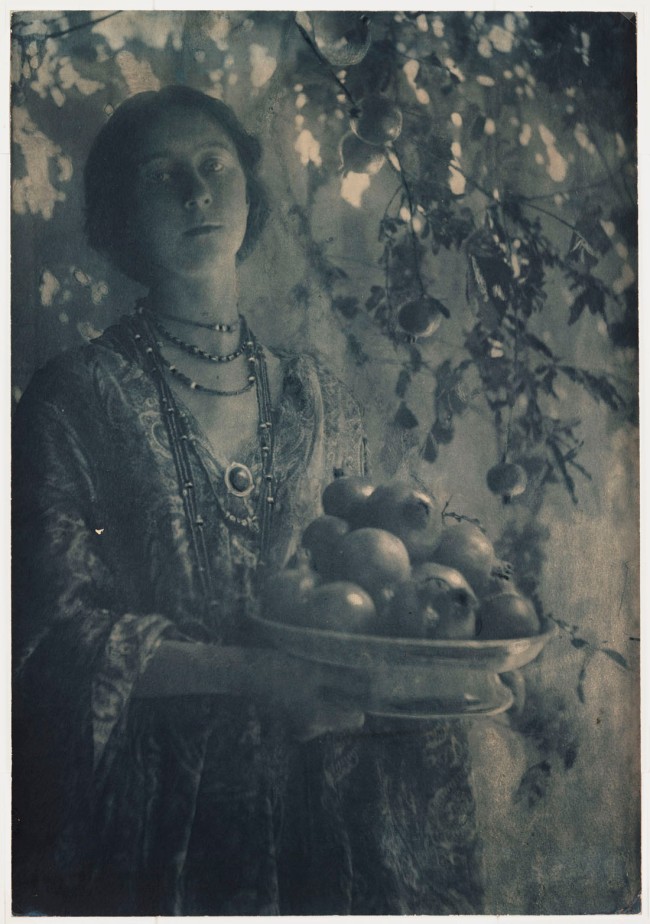

Minna Keene (Canadian born Germany, 1861-1943)

Decorative Study

c. 1906

© Royal Photographic Society / National Media Museum/ Science & Society Picture Library

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828-1882)

Proserpine

1874

Oil on canvas

Support: 1251 x 610mm

Frame: 1605 x 930 x 85mm

Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1940

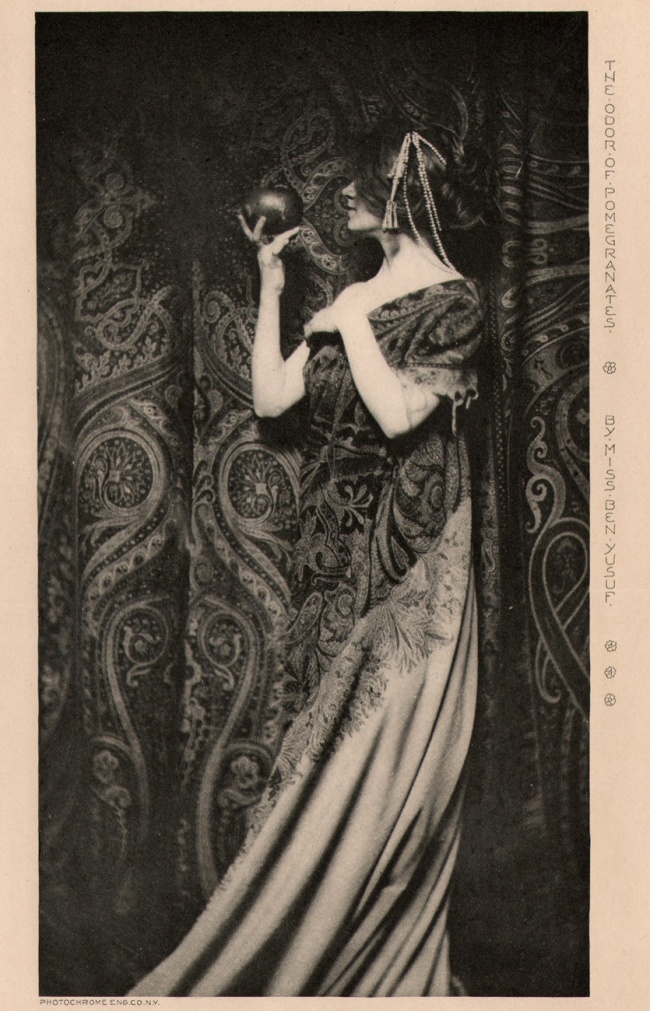

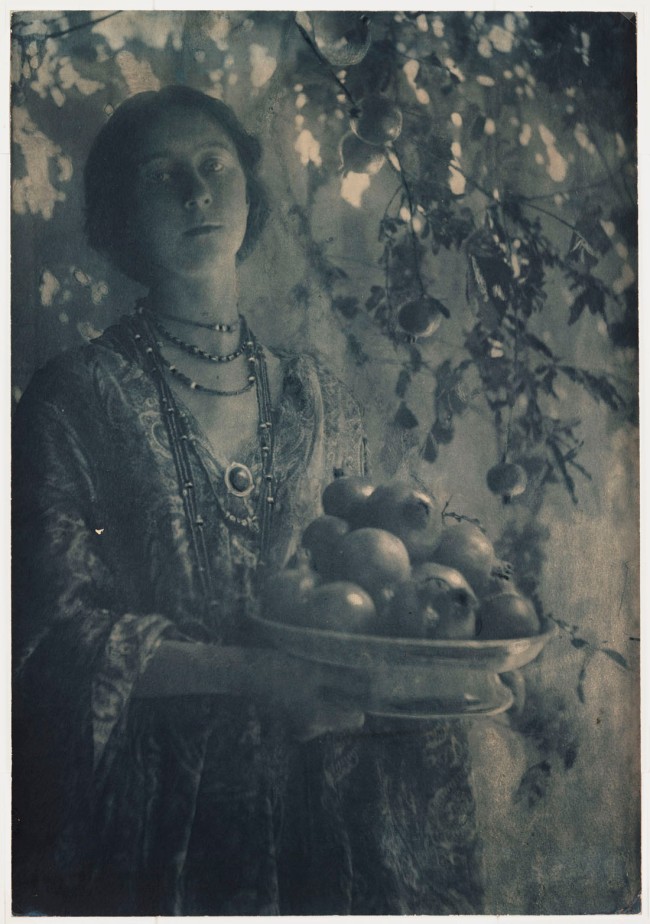

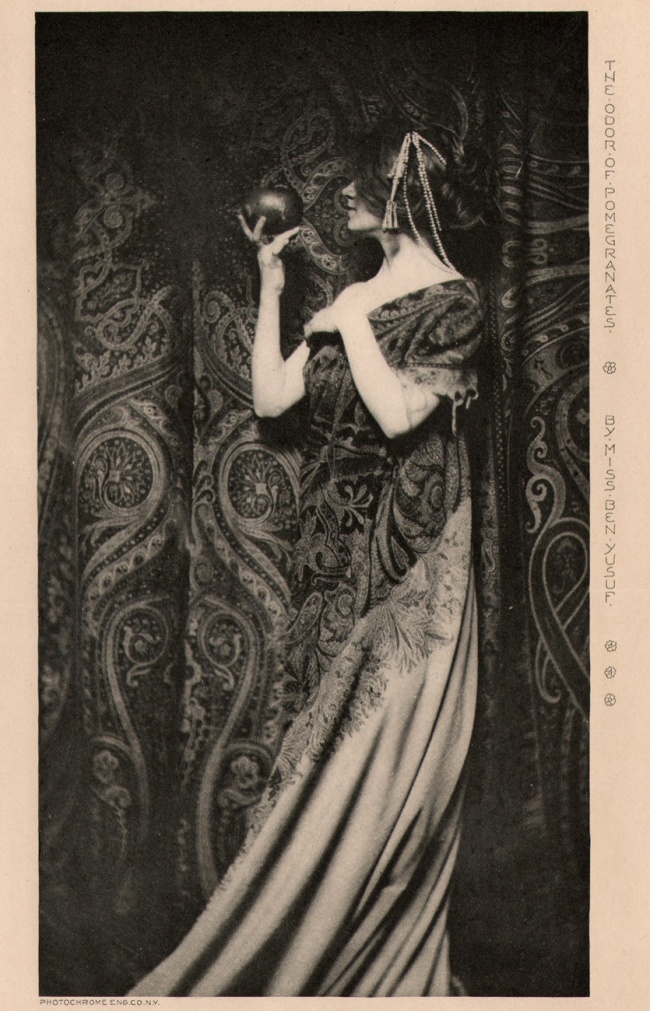

Zaida Ben-Yusuf (American born England, 1869-1933)

The Odor of Pomegranates

1899, published 1901

Photogravure on paper

Tate

Zaida Ben-Yusuf (21 November 1869 – 27 September 1933) was a New York-based portrait photographer noted for her artistic portraits of wealthy, fashionable, and famous Americans of the turn of the 19th-20th century. She was born in London to a German mother and an Algerian father, but became a naturalised American citizen later in life. In 1901 the Ladies Home Journal featured her in a group of six photographers that it dubbed, “The Foremost Women Photographers in America.” In 2008, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery mounted an exhibition dedicated solely to Ben-Yusuf’s work, re-establishing her as a key figure in the early development of fine art photography…

In 1896, Ben-Yusuf began to be known as a photographer. In April 1896, two of her pictures were reproduced in The Cosmopolitan Magazine, and another study was exhibited in London as part of an exhibition put on by The Linked Ring. She travelled to Europe later that year, where she met with George Davison, one of the co-founders of The Linked Ring, who encouraged her to continue her photography. She exhibited at their annual exhibitions until 1902.

In the spring of 1897, Ben-Yusuf opened her portrait photography studio at 124 Fifth Avenue, New York. On 7 November 1897, the New York Daily Tribune ran an article on Ben-Yusuf’s studio and her work creating advertising posters, which was followed by another profile in Frank Leslie’s Weekly on 30 December. Through 1898, she became increasingly visible as a photographer, with ten of her works in the National Academy of Design-hosted 67th Annual Fair of the American Institute, where her portrait of actress Virginia Earle won her third place in the Portraits and Groups class. During November 1898, Ben-Yusuf and Frances Benjamin Johnston held a two-woman show of their work at the Camera Club of New York.

In 1899, Ben-Yusuf met with F. Holland Day in Boston, and was photographed by him. She relocated her studio to 578 Fifth Avenue, and exhibited in a number of exhibitions, including the second Philadelphia Photographic Salon. She was also profiled in a number of publications, including an article on female photographers in The American Amateur Photographer, and a long piece in The Photographic Times in which Sadakichi Hartmann described her as an “interesting exponent of portrait photography”.

1900 saw Ben-Yusuf and Johnston assemble an exhibition on American women photographers for the Universal Exposition in Paris. Ben-Yusuf had five portraits in the exhibition, which travelled to Saint Petersburg, Moscow, and Washington, D.C. She was also exhibited in Holland Day’s exhibition, The New School of American Photography, for the Royal Photographic Society in London, and had four photographs selected by Alfred Stieglitz for the Glasgow International Exhibition of 1901, Scotland.

In 1901, Ben-Yusuf wrote an article, “Celebrities Under the Camera”, for the Sunday Evening Post, where she described her experiences with her sitters. By this stage she had photographed Grover Cleveland, Franklin Roosevelt, and Leonard Wood, amongst others. For the September issue of Metropolitan Magazine she wrote another article, “The New Photography – What It Has Done and Is Doing for Modern Portraiture”, where she described her work as being more artistic than most commercial photographers, but less radical than some of the better-known art photographers. The Ladies Home Journal that November declared her to be one of the “foremost women photographers in America”, as she began the first of a series of six illustrated articles on “Advanced Photography for Amateurs” in the Saturday Evening Post.

Ben-Yusuf was listed as a member of the first American Photographic Salon when it opened in December 1904, although her participation in exhibitions was beginning to drop off. In 1906, she showed one portrait in the third annual exhibition of photographs at Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, the last known exhibition of her work in her lifetime.

Text from the Wikipedia website

In the Studio

Many photographers trained as painters. They set up studios and employed artists’ models, skilled at holding poses for the time it took to take a picture. Later in the century, improved photographic negatives required shorter exposure times and it became easier to stage and capture difficult positions and spontaneous gestures.

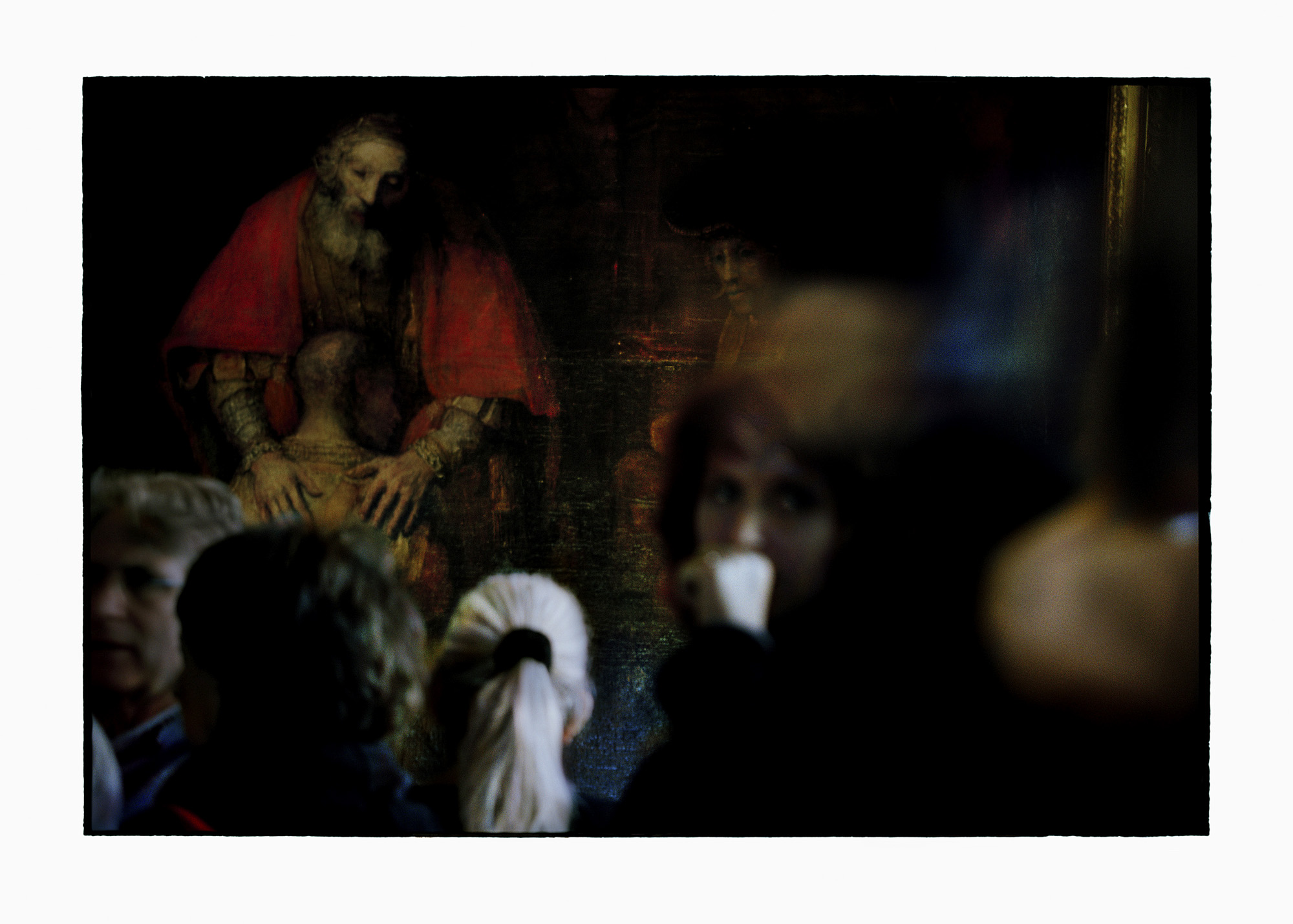

Painters and illustrators used photographs as preparatory studies and as substitutes for props, costumes and models, and art schools created photographic archives for their students. Photographs commissioned and sold by institutions such as the British Museum made classical sculpture and old master paintings more accessible, inspiring both painters and photographers.

Henry Wallis (British, 1830-1916)

Chatterton

1856

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 622 x 933mm

Frame: 905 x 1205 x 132mm

Tate

Bequeathed by Charles Gent Clement 1899

Chatterton is Wallis’s earliest and most famous work. The picture created a sensation when it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1856, accompanied by the following quotation from Marlowe:

Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight

And burned is Apollo’s laurel bough.

Ruskin described the work in his Academy Notes as ‘faultless and wonderful’.

Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) was an 18th Century poet, a Romantic figure whose melancholy temperament and early suicide captured the imagination of numerous artists and writers. He is best known for a collection of poems, written in the name of Thomas Rowley, a 15th Century monk, which he copied onto parchment and passed off as mediaeval manuscripts. Having abandoned his first job working in a scrivener’s office he struggled to earn a living as a poet. In June 1770 he moved to an attic room at 39 Brooke Street, where he lived on the verge of starvation until, in August of that year, at the age of only seventeen, he poisoned himself with arsenic. Condemned in his lifetime as a forger by influential figures such as the writer Horace Walpole (1717-1797), he was later elevated to the status of tragic hero by the French poet Alfred de Vigny (1797-1863).

Wallis may have intended the picture as a criticism of society’s treatment of artists, since his next picture of note, The Stonebreaker (1858, Birmingham City Museum and Art Gallery), is one of the most forceful examples of social realism in Pre-Raphaelite art. The painting alludes to the idea of the artist as a martyr of society through the Christ-like pose and the torn sheets of poetry on the floor. The pale light of dawn shines through the casement window, illuminating the poet’s serene features and livid flesh. The harsh lighting, vibrant colours and lifeless hand and arm increase the emotional impact of the scene. A phial of poison on the floor indicates the method of suicide. Following the Pre-Raphaelite credo of truth to nature, Wallis has attempted to recreate the same attic room in Gray’s Inn where Chatterton had killed himself. The model for the figure was the novelist George Meredith (1828-1909), then aged about 28. Two years later Wallis eloped with Meredith’s wife, a daughter of the novelist Thomas Love Peacock (1785-1866).

Frances Fowle. “Chatterton,” on the Tate website December 2000 [Online] Cited 16/02/2023

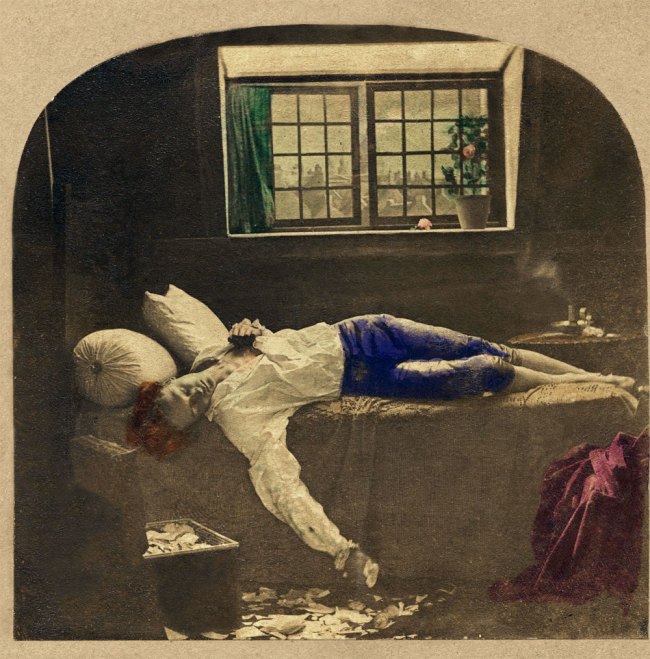

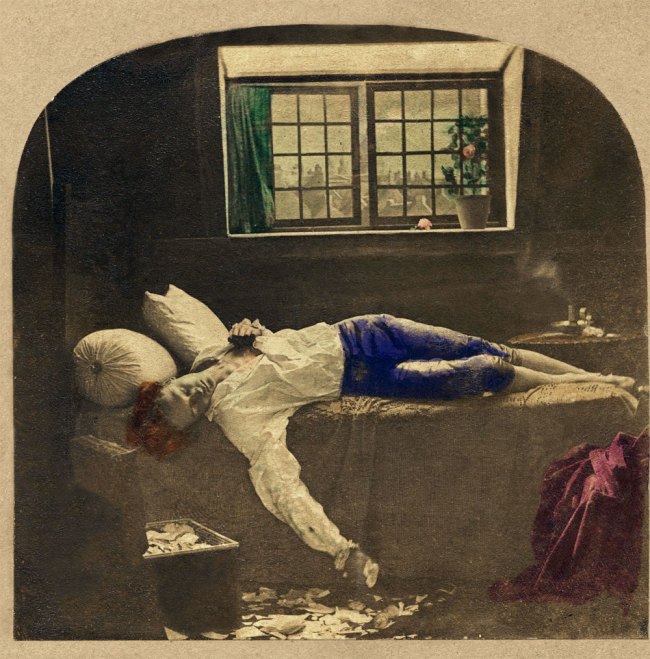

James Robinson

The Death of Chatterton

1859

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

James Robinson

The Death of Chatterton (detail)

1859

Two photographs, hand-tinted albumen prints on paper mounted on card

Collection Dr Brian May

THIS STEREOCARD IS NOT IN THE EXHIBITION

One of the most famous paintings of Victorian times was Chatterton, 1856 (Tate) by the young Pre-Raphaelite-style artist, Henry Wallis (1830-1916). Again, the tale of the suicide of the poor poet, Thomas Chatterton, exposed as a fraud for faking medieval histories and poems to get by, had broad appeal. Chatterton was also an 18th-century figure, but Wallis set his picture in a bare attic overlooking the City of London which evoked the urban poverty of his own age. The picture toured the British Isles and hundreds of thousands flocked to pay a shilling to view it. One of these was James Robinson, who saw the painting when it was in Dublin. He immediately conceived a stereographic series of Chatterton’s life. Unfortunately Robinson started with Wallis’s scene (The Death of Chatterton, 1859). Within days of its publication, legal procedures began, claiming his picture threatened the income of the printmaker who had the lucrative copyright to publish engravings of the painting. The ensuing court battles were the first notorious copyright cases. Robinson lost, but strangely, in 1861, Birmingham photographer Michael Burr published variations of Death of Chatterton with no problems. No other photographer was ever prosecuted for staging a stereoscopic picture after a painting and the market continued to thrive…

Robinson’s The Death of Chatterton illustrates the way this uncanny quality [the ability to record reality in detail] distinguishes the stereograph from even the immaculate Pre-Raphaelite style of Wallis’s painting of the same subject. The stereograph represented a young man in 18th-century costume on a bed. The backdrop was painted, but the chest, discarded coat and candle were real. Again, the light and colour appear crude in comparison with the painting but the stereoscope records ‘every stick, straw, scratch’ in a manner that the painting cannot. The torn paper pieces, animated by their three-dimensionality, trace the poet’s recent agitation, while the candle smoke, representing his extinguished life, is different in each photograph due to their being taken at separate moments. The haphazard creases of the bed sheet are more suggestive of restless movement, now stilled, than Wallis’s elegant drapery. Even the individuality of the boy adds potency to his death.

Extract from the essay by Carol Jacobi. “Tate Painting and the Art of Stereoscopic Photography,” on the Tate website 17th October, 2014 [Online] Cited 14/02/2015

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828-1882)

Beata Beatrix

c. 1864-1870

Oil on canvas

Support: 864 x 660mm

Frame: 1212 x 1015 x 104mm

Presented by Georgiana, Baroness Mount-Temple in memory of her husband, Francis, Baron Mount-Temple 1889

Rossetti draws a parallel in this picture between the Italian poet Dante’s despair at the death of his beloved Beatrice and his own grief at the death of his wife Elizabeth Siddal, who died on 11 February 1862. Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) recounted the story of his unrequited love and subsequent mourning for Beatrice Portinari in the Vita Nuova. This was Rossetti’s first English translation and appeared in 1864 as part of his own publication, The Early Italian Poets.

The picture is a portrait of Elizabeth Siddall in the character of Beatrice. It has a hazy, transcendental quality, giving the sensation of a dream or vision, and is filled with symbolic references. Rossetti intended to represent her, not at the moment of death, but transformed by a ‘sudden spiritual transfiguration’ (Rossetti, in a letter of 1873, quoted in Wilson, p.86). She is posed in an attitude of ecstasy, with her hands before her and her lips parted, as if she is about to receive Communion. According to Rossetti’s friend F.G. Stephens, the grey and green of her dress signify ‘the colours of hope and sorrow as well as of love and life’ (‘Beata Beatrix by Dante Gabriel Rossetti’, Portfolio, vol. 22, 1891, p. 46).

In the background of the picture the shadowy figure of Dante looks across at Love, portrayed as an angel and holding in her palm the flickering flame of Beatrice’s life. In the distance the Ponte Vecchio signifies the city of Florence, the setting for Dante’s story. Beatrice’s impending death is evoked by the dove – symbol of the holy spirit – which descends towards her, an opium poppy in its beak. This is also a reference to the death of Elizabeth Siddall, known affectionately by Rossetti as ‘The Dove’, and who took her own life with an overdose of laudanum. Both the dove and the figure of Love are red, the colour of passion, yet Rossetti envisaged the bird as a messenger, not of love, but of death. Beatrice’s death, which occurred at nine o’clock on 9th June 1290, is foreseen in the sundial which casts its shadow over the number nine. The picture frame, which was designed by Rossetti, has further references to death and mourning, including the date of Beatrice’s death and a phrase from Lamentations 1:1, quoted by Dante in the Vita Nuova: ‘Quomodo sedet sola civitas’ (‘how doth the city sit solitary’), referring to the mourning of Beatrice’s death throughout the city of Florence.

Frances Fowle. “Beata Beatrix,” on the Tate website December 2000 [Online] Cited 16/02/2023

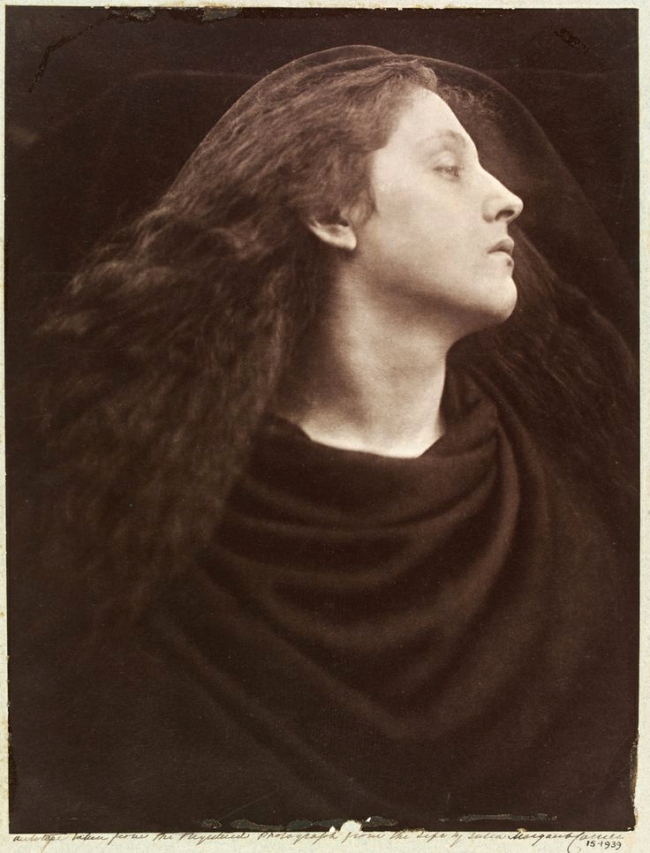

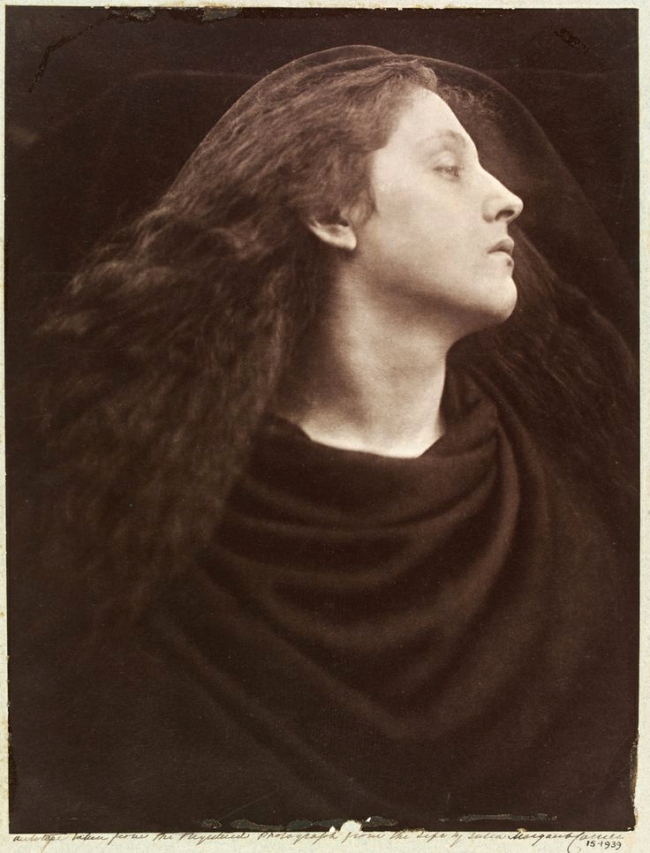

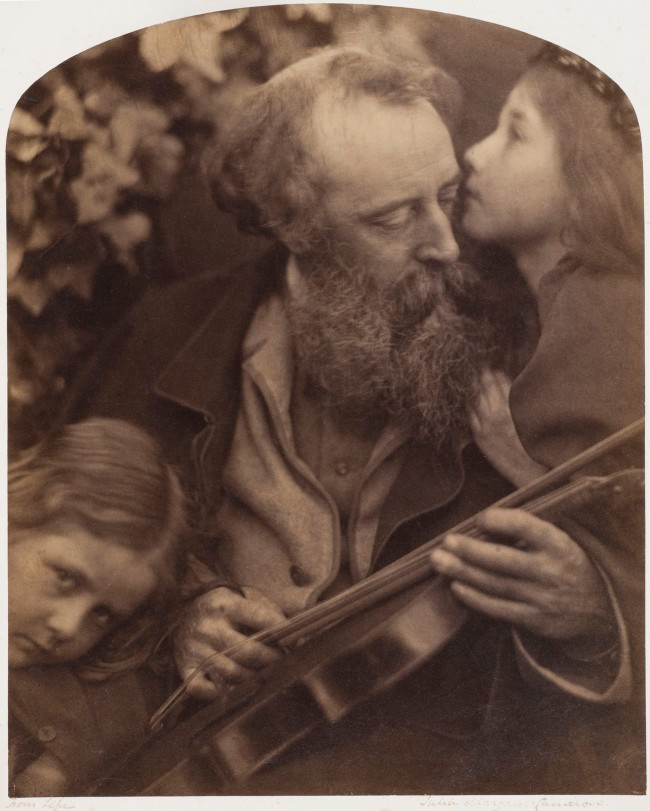

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die!

1867

© Royal Photographic Society / National Media Museum / Science & Society Picture Library

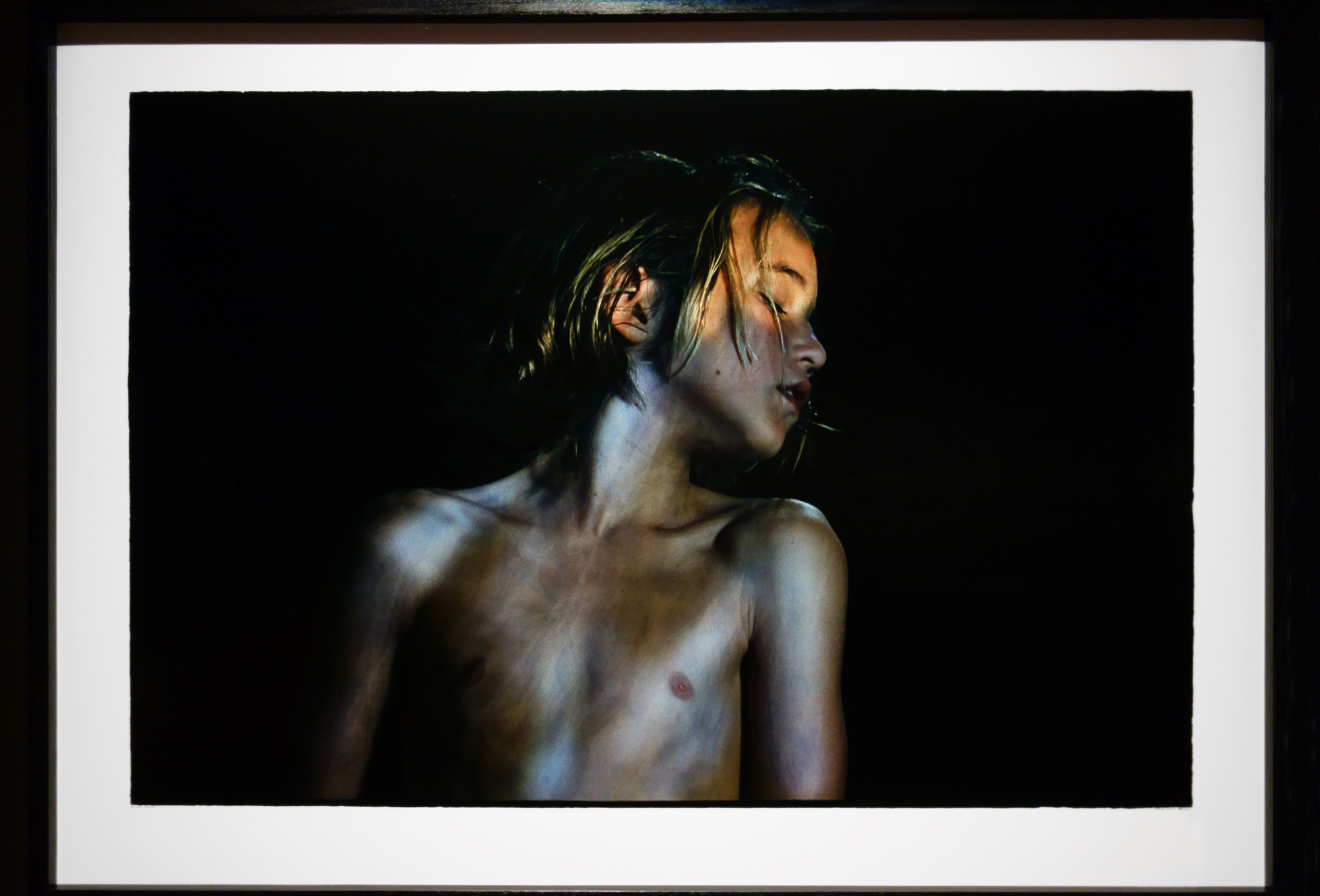

In late 1865, Julia Margaret Cameron began using a larger camera. It held a 15 x 12 inch glass negative, rather than the 12 x 10 inch negative of her first camera. Early the next year she wrote to Henry Cole with great enthusiasm – but little modesty – about the new turn she had taken in her work. Cameron initiated a series of large-scale, closeup heads that fulfilled her photographic vision. She saw them as a rejection of ‘mere conventional topographic photography – map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form’ in favour of a less precise but more emotionally penetrating form of portraiture. Cameron also continued to make narrative and allegorical tableaux, which were larger and bolder than her previous efforts.

In this image, Cameron concentrates upon the head of her maid Mary Hillier by using a darkened background and draping her in simple dark cloth. The lack of surrounding detail or context obscures references to narrative, identity or historical context. The flowing hair, lightly parted lips and exposed neck suggest sensuality. The title, taken from a line in the poem ‘Lancelot and Elaine’ from Alfred Tennyson’s ‘Idylls of the King’, transforms the subject into a tragic heroine.

Anonymous. “Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die!,” on the V&A website [Online] Cited 16/02/2023

New truths

Mid-nineteenth century innovations in science and the arts became part of intense debates about ‘truth’ – variously defined as objective observation and as individual artistic vision. Inspired by artist and critic John Ruskin, the Pre-Raphaelite circle took a new approach to nature, discovering meaning in details previously overlooked, ‘rejecting nothing, selecting nothing’.

As the quality of paints and lenses improved, painters and photographers tested the bounds of perception and representation. They moved out of the studio, to explore light and other atmospheric effects as well as geological subjects, landscape and architecture. New photographic materials like glass plate negatives and coated printed papers offered greater accuracy and photography became a valuable aid for painters.

John Brett (British, 1831-1902)

Glacier of Rosenlaui

1856

Oil on canvas

Height: 445 mm (17.52 in)

Width: 419 mm (16.5 in)

Tate Britain

Purchased 1946

Photo: Tate, London, 2011

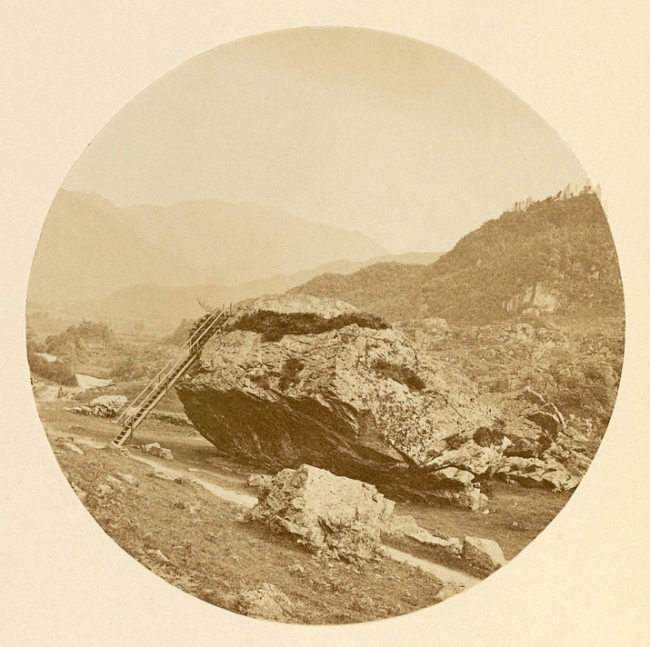

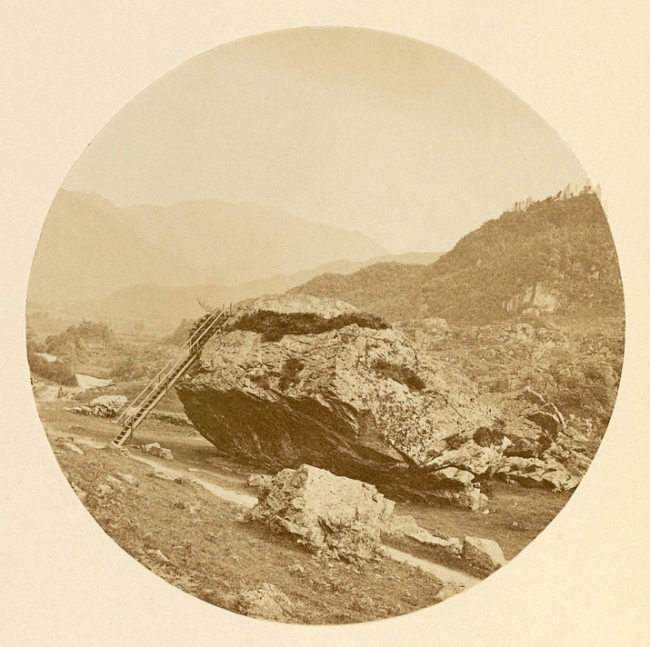

Thomas Ogle (British, 1813 – about 1882)

The Bowder Stone in Our English Lakes, Mountains and Waterfalls as seen by William Wordsworth by A.W. Bennett

Published 1864

Tate

View taken by Thomas Ogle of the Bowder Stone in Borrowdale, Cumbria, illustrating Our English Lakes, Mountains, And Waterfalls, as seen by William Wordsworth (1864). The book juxtaposes photographs of the Lake District with poems by the English Romantic poet. The Bowder Stone, an enormous boulder, was probably deposited by glaciation during the last Ice Age. It rests in Borrowdale, a valley of woods and crags in the Lake District whose scenic beauty inspired artists, writers and poets of the Romantic Movement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Wordsworth (1770-1850) was among them, and the photograph of the Bowder Stone accompanies his poem, Yew-Trees (1803), from which the following passage is taken:

“…But worthier still of note

Are those fraternal four of Borrowdale,

Joined in one solemn and capacious grove;

Huge trunks! – and each particular trunk a growth

Of intertwined fibres serpentine

Up-coiling, and inveterately convolved, –

Nor uninformed with phantasy, and looks

That threaten the profane; – a pillared shade,

Upon whose grassless floor of red-brown hue,

By sheddings from the pining umbrage tinged

Perenially – beneath whole sable roof

Of boughs, as if for festal purpose, decked

With unrejoicing berries, ghostly shapes

May meet at noontide – Fear and trembling Hope,

Silence and Foresight – Death the skeleton

And Time the shadow…”

Text from the British Library website [Online] Cited 18/09/2016

Atkinson Grimshaw (English, 1836-1893)

Bowder Stone, Borrowdale

c. 1863-1868

Oil on canvas

Support: 400 x 536mm

Frame: 662 x 709 x 100mm

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1983

Tate Britain uncovers the dynamic dialogue between British painters and photographers; from the birth of the modern medium to the blossoming of art photography. Spanning over 70 years, the exhibition brings together nearly 200 works – many for the first time – to reveal their mutual influences. From the first explorations of movement and illumination by David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848) to artful compositions at the turn-of-the-century, the show discovers how painters and photographers redefined notions of beauty and art itself.

The dawn of photography coincided with a tide of revolutionary ideas in the arts, which questioned how pictures should be created and seen. Photography adapted the Old Master traditions within which many photographers had been trained, and engaged with the radical naturalism of JMW Turner (1775-1851), the Pre-Raphaelites, and their Realist and Impressionist successors. Turner inspired the first photographic panoramic views, and, in the years that followed his death, photographers and painters followed in his footsteps and composed novel landscapes evoking meaning and emotion. The exhibition includes examples such as John Everett Millais’s (1829-1896) nostalgic The Woodman’s Daughter and John Brett’s (1831-1902) awe inspiring Glacier Rosenlaui. Later in the century, PH Emerson (1856-1936) and TF Goodall’s (c. 1856-1944) images of rural river life allied photography to Impressionist painting, while JAM Whistler (1834-1903) and Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882-1966) created smoky Thames nocturnes in both media.

The exhibition celebrates the role of women photographers, such as Zaida Ben-Yusuf (1869-1933) and the renowned Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). Cameron’s artistic friendships with George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1830-94) are recognised in a room devoted to their beautiful, enigmatic portraits of each other and shared models, where works including Cameron’s Call, I Follow, I Follow, Let Me Die and Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix are on display.

Highlights of the show include examples of three-dimensional photography, which incorporated the use of models and props to stage dramatic tableaux from popular works of the time, re-envisioning well-known pictures such as Henry Wallis’s (1830-1916) Chatterton. Such stereographs were widely disseminated and made art more accessible to the public, often being used as a form of after-dinner entertainment for middle class Victorian families. A previously unseen private album in which the Royal family painstakingly re-enacted famous paintings is also exhibited, as well as rare examples of early colour photography.

Carol Jacobi, Curator British Art 1850-1915, Tate Britain says: “Painting with Light offers new insights into Britain’s most popular artists and reveals just how vital painting and photography were to one another. Their conversations were at the heart of the artistic achievements of the Victorian and Edwardian era.”

Painting with Light: Art and Photography from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Modern Age is curated by Dr Carol Jacobi, Curator of British Art 1850-1915 at Tate Britain, and Dr Hope Kingsley, Curator, Education and Collections, Wilson Centre for Photography, with Tim Batchelor, Assistant Curator at Tate Britain. The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue from Tate Publishing and a programme of talks and events in the gallery.”

Press release from Tate Britain

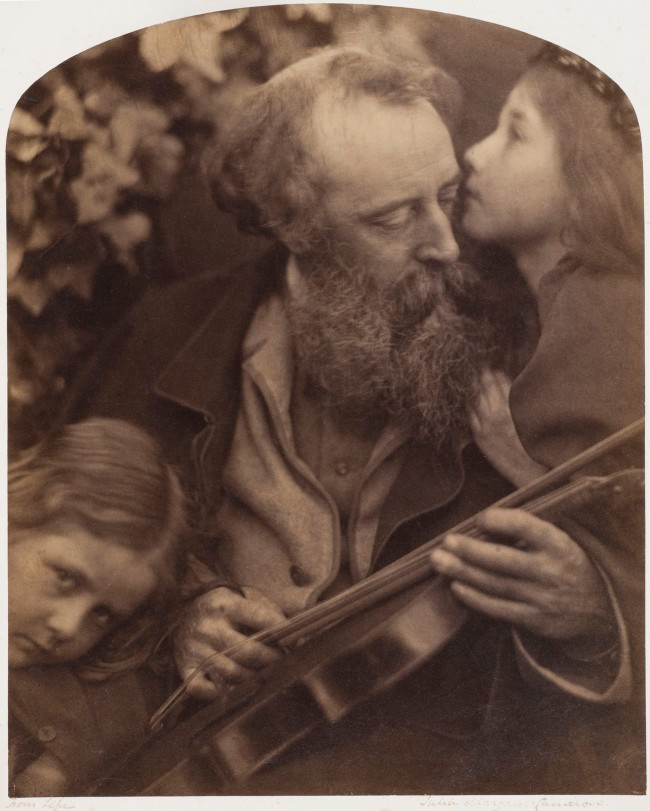

‘Whisper of the Muse’

As the nineteenth century progressed, some artists moved away from the clarity and detail that had been the aim of earlier Pre-Raphaelite art, turning instead to a search for pure beauty. The aesthetic movement, as this tendency came to be known, emphasised the sensual qualities of art and design and explored imaginative themes and effects.

In London and on the Isle of Wight, a community of artists forged closer links between the visual arts, music and literature. This circle included the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, painters George Frederic Watts and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and the poet Alfred Tennyson. Rossetti and Cameron worked with similar subjects, many inspired by Tennyson’s poetry. Together with Watts they developed a newly-intimate form of portraiture, exploring emotional and psychological states. They also shared models, whose striking looks introduced new types of modern beauty.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Whisper of the Muse

1865

Photograph, albumen print on paper

325 x 238mm

Wilson Centre for Photography

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828-1882)

Mariana

1870

Oil on canvas

Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museum Collection

Into Light and Colour

In the second half of the nineteenth century Japanese culture became an important influence in Britain. Japanese goods were sold in London in new department stores such as Liberty, while the Japanese Village, established in Knightsbridge in 1885, attracted more than a million visitors.

Japanese props and motifs appeared in art and design and the vogue for Japanese prints inspired painters and photographers. Painters experimented with new colour palettes, flattened picture planes and condensed, cropped formats, innovations also important to later British impressionist works. Such experiments in light and colour were paralleled in photography with the 1907 introduction of the autochrome, the first practical colour photographic process.

John Cimon Warburg (British, 1867-1931)

Peggy in the Garden

1909, printed 2016

Photograph, transparency on lightbox from autochrome

Royal Photographic Society / National Media Museum / Science and Society Picture Library

John Cimon Warburg (1867-1931) British photographer born to a wealthy family dedicated his whole life to photography. In 1897, he joined the Royal Photographic Society. During his photographic career, John Cimon Warburg used a wide range of photographic processes, but excelled especially in autochromes. Best known for his atmospheric landscapes and its fascinating studies of his children, Warburg lectured and written about the process and explained his autochromes the annual exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society.

Text from the Autochrome website [Online] Cited 18/09/2016. No longer available online

Patented by the Lumière brothers in 1903, Autochrome produced a colour transparency using a layer of potato starch grains dyed red, green and blue, along with a complex development process. Autochromes required longer exposure times than traditional black-and-white photos, resulting in images with a hazy, blurred atmosphere filled with pointillist dots of colour.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925)

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose

1885-1886

Oil paint on canvas

1740 x 1537 mm

Tate. Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey

Bequest 1887

The inspiration for Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose came during a boating expedition Sargent took on the Thames at Pangbourne in September 1885, with the American artist Edwin Austin Abbey, during which he saw Chinese lanterns hanging among trees and lilies. He began the picture while staying at the home of the painter F.D. Millet at Broadway, Worcestershire, shortly after his move to Britain from Paris. At first he used the Millets’s five-year-old daughter Katharine as his model, but she was soon replaced by Polly and Dorothy (Dolly) Barnard, the daughters of the illustrator Frederick Barnard, because they had the exact hair-colour Sargent was seeking.

He worked on the picture, one of the few figure compositions he ever made out of doors in the impressionist manner, from September to early November 1885, and again at the Millets’s new home, Russell House, Broadway, during the summer of 1886, completing it some time in October. Sargent was able to work for only a few minutes each evening when the light was exactly right. He would place his easel and paints beforehand, and pose his models in anticipation of the few moments when he could paint the mauvish light of dusk.

As autumn came and the flowers died, he was forced to replace the blossoms with artificial flowers. The picture was both acclaimed and decried at the 1887 Royal Academy exhibition. The title comes from the song The Wreath, by the eighteenth-century composer of operas Joseph Mazzinghi, which was popular in the 1880s. Sargent and his circle frequently sang around the piano at Broadway. The refrain of the song asks the question ‘Have you seen my Flora pass this way?’ to which the answer is ‘Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose’.

Terry Riggs. “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose,” on the Tate website February 1998 [Online] Cited 16/02/2023

Unknown photographer

H.R.H. Princess Alexandra, H.R.H. Princess Victoria & Mr. Savile, “Two’s company and three’s none” in Tableaux Vivants Devonport

c. 1892-1893

Bound volume. Displayed open at Marcus C. Stone’s ‘Two’s Company, Three’s None”

Photograph, albumen print on paper

360 x 480 x 58mm – book closed

Wilson Centre for Photography

Unknown photographer

H.R.H. Princess Alexandra, H.R.H. Princess Victoria & Mr. Savile, “Two’s company and three’s none” in Tableaux Vivants Devonport (detail)

c. 1892-1893

Bound volume. Displayed open at Marcus C. Stone’s ‘Two’s Company, Three’s None”

Photograph, albumen print on paper

360 x 480 x 58mm – book closed

Wilson Centre for Photography

Thomas Armstrong (English, 1832-1911)

The Hay Field

1869

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

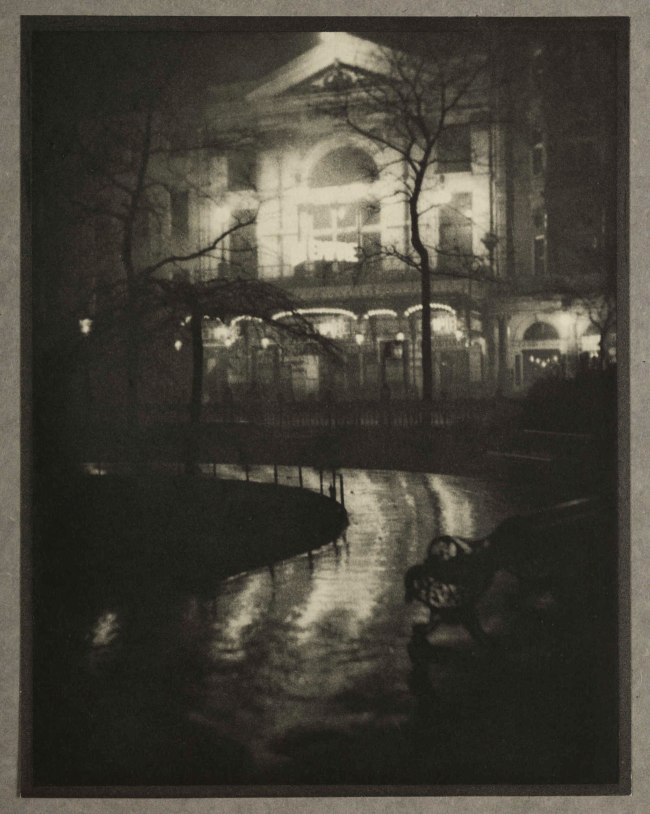

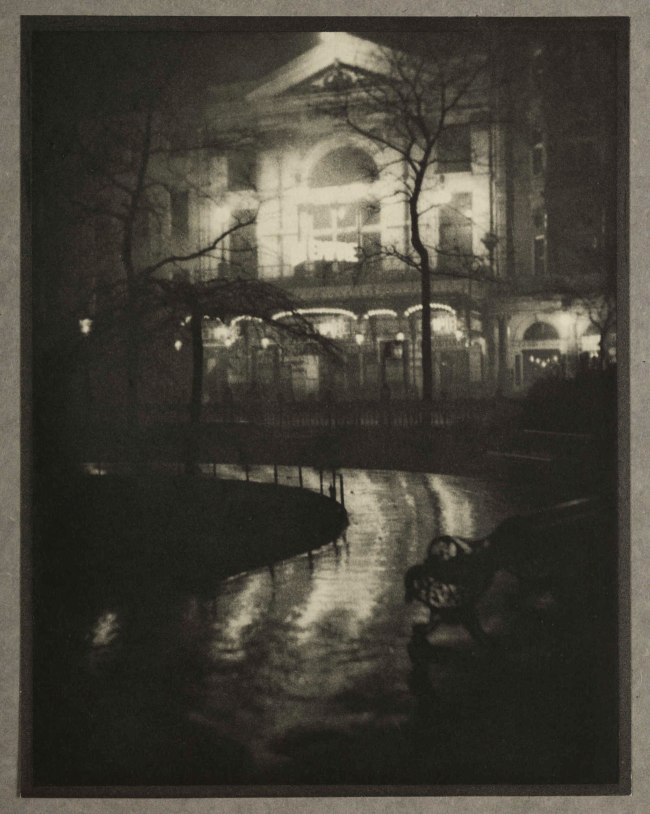

Atmosphere and Effect

The relationship between landscape painting and photography continued to develop into the twentieth century. The etchings and nocturnes of James Abbott McNeill Whistler inspired photographers, who adopted his atmospheric subjects and aesthetics. While photography had achieved a technical sophistication that allowed photographers to produce highly resolved, realistic images, many chose to pursue soft-focus effects rather than detail and precision. Such photographs paralleled the unpeopled landscapes of painters like John Everett Millais and the gas-lit cityscapes of John Atkinson Grimshaw.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, 1834-1903)

Three Figures Pink and Grey

1868-1878

Oil paint on canvas

Support: 1391 x 1854mm

Frame: 1701 x 2158 x 75mm

Tate

Purchased with the aid of contributions from the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers as a Memorial to Whistler, and from Francis Howard 1950

This picture derives from one of six oil sketches that Whistler produced in 1868 as part of a plan for a frieze, commissioned by the businessman F.R. Leyland (1831-1892), founder of the Leyland shipping line. Known as the ‘Six Projects’, the sketches (now in the Freer Art Gallery, Washington) were all scenes with women and flowers, and all six were strongly influenced by his admiration for Japanese art. Another precedent for these works was The Story of St George, a frieze that Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898) executed for the artist and illustrator Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) in 1865-1867. The series of large pictures was destined for Leyland’s house at Prince’s Gate, but never produced, and only one – The White Symphony: Three Girls (1867) was finished, but was later lost. Whistler embarked on a new version, Three Figures: Pink and Grey, but was never satisfied with this later painting, and described it as, ‘a picture in no way representative, and in its actual condition absolutely worthless’ (quoted in Wilton and Upstone, p. 117). He followed the original sketch closely, but made a number of pentimenti which suggest that the picture is not simply a copy of the lost work. In spite of Whistler’s dissatisfaction, it has some brilliant touches and a startlingly original composition.

Although the three figures are clearly engaged in tending a flowering cherry tree, Whistler’s aim in this picture is to create a mood or atmosphere, rather than to suggest any kind of theme. Parallels have been drawn with the work of Albert Moore, whose work of this period is equally devoid of narrative meaning. The design is economical and the picture space is partitioned like a Japanese interior. The shallow, frieze-like arrangement, the blossoming plant and the right-hand figure’s parasol are also signs of deliberate Japonisme. Whistler has suppressed some of the details in the oil sketch, effectively disrobing the young girls by depicting them in diaphanous robes. The painting is characterised by pastel shades, a ‘harmony’ of pink and grey, punctuated by the brighter reds of the flower pot and the girls’ bandannas, and the turquoise wall behind. It has been suggested that Whistler derived his colour schemes, and even the figures themselves, in their rhythmically flowing drapery, from polychrome Tanagra figures in the British Museum, which was opposite his studio in Great Russell Street.

Frances Fowle. “Three Figures: Pink and Grey,” on the Tate website December 2000 [Online] Cited 16/02/2023

John Cimon Warburg (British, 1867-1931)

The Japanese Parasol

c. 1906

Autochrome

711 x 559mm

© Royal Photographic Society / National Media

Museum/ Science & Society Picture Library

Life and Landscape

The 1880s brought a renewed interest in landscape. Rural scenes provided common ground for British painters and photographers. Their distinctive style derived from French realism and impressionism, which had been introduced by independent galleries, and by artists such as George Clausen and Henry La Thangue who studied in Paris. This new approach was shared by their friend and fellow painter Thomas Goodall, and influenced his collaboration with the photographer Peter Henry Emerson. Emerson and Goodall’s first project, a photographic series on the Norfolk Broads, focused on the life of working people, as described in their album Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, published in 1887.

Sir George Clausen (British, 1852-1944)

Winter Work

1883-1884

Oil on canvas

Frame: 1075 x 1212 x 115mm

Support: 775 x 921mm

Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1983

© The estate of Sir George Clausen

In the 1880s Clausen devoted himself to painting realistic scenes of rural work after seeing such pictures by the French artist Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884). In this picture he shows a family of field workers topping and tailing swedes for sheep fodder. It was painted at Chilwick Green near St Albans, where the artist had moved in 1881. He uses subdued colouring to capture the dull light and cold of winter, and manages to convey the hard reality of country work. Such unromanticised scenes of country life were often rejected by the selectors of the Royal Academy annual exhibitions.

Thomas Frederick Goodall (British, 1856-1944) and Peter Henry Emerson (British, 1856-1936)

Setting the Bow-Net, in Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads

1885, published 1887

Book – open at The Bow Net

Photograph, platinum print on paper

300 x 420mm (book closed)

Private collection

Thomas Frederick Goodall (British, 1856-1944)

The Bow Net

1886

Oil paint on canvas

838 x 1270mm

National Museums Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery

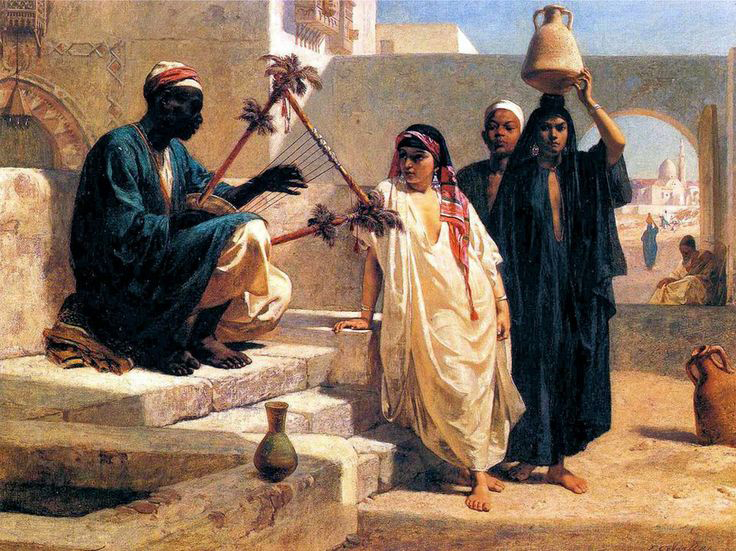

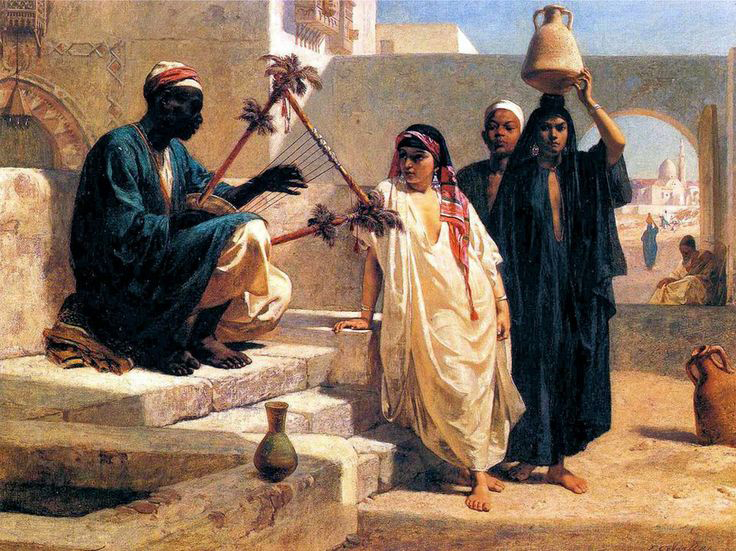

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

The Water Carrier

1858

Albumen Print, Wilson Center for Photography

Frederick Goodall (English, 1822-1904), R.A.

The Song of the Nubian Slave

1863

Diploma Work, accepted 1863

71.2 x 92 x 2.3cm

Oil on canvas

Photo credit: © Royal Academy of Arts, London; Photographer: John Hammond

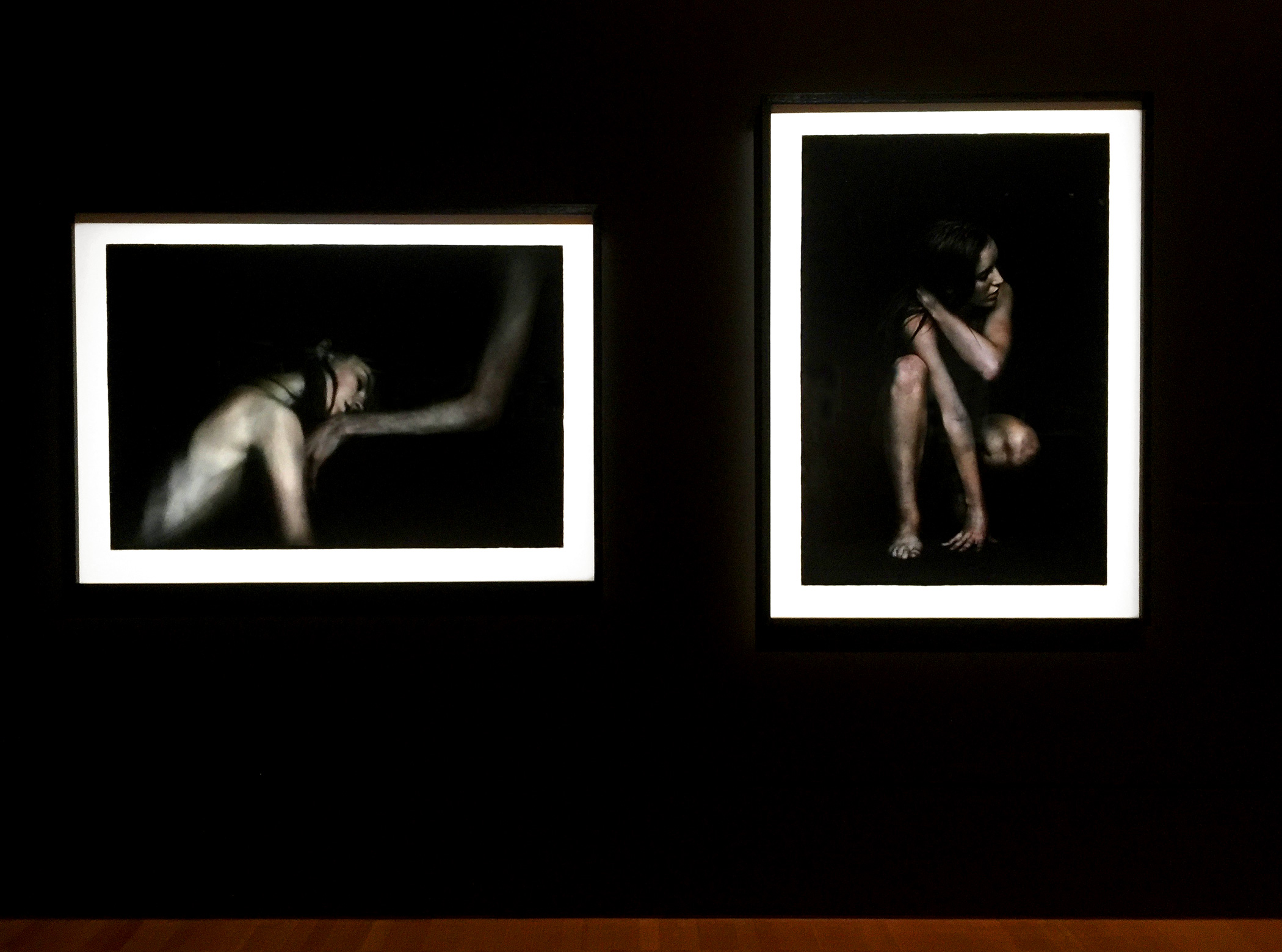

Out of the Shadows

In the late nineteenth century, painters and photographers pursued the representation of an idealised beauty, inspired by Italian Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. Themes of allegory and myth were widely explored in the arts at this time, particularly in Britain in the writings of Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde.

At the turn of the century painting and photography were part of a wider artistic search for harmony between subject matter and expression. Artists found inspiration in each other’s practice and continued to share ideas through illustrated books and journals. This spirit of collaboration and interchange led photographer Fred Holland Day to claim that ‘the photographer no longer speaks the language of chemistry, but that of poetry’.

Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882-1966)

Regent’s Canal

c. 1904-1905, published 1909

Photogravure on paper

Image: 206 x 161 mm

Frame: 508 x 406 mm

Wilson Centre for Photography

Arthur Hacker (English, 1858-1919)

A Wet Night at Piccadilly Circus

1910

Oil on canvas

710 x 915mm

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Alvin Langdon Coburn (American, 1882-1966)

Leicester Square (The Old Empire Theatre)

1908, published 1909

Photogravure on paper

Image: 206 x 172mm

Frame: 508 x 406mm

Wilson Centre for Photography

Edward Linley Sambourne (English, 1844-1910)

Ethel Warwick, Camera Club, 2 August 1900

Photograph, cyanotype on paper

Dimensions

Image: 165 x 120mm

Frame: 507 x 855mm

18 Stafford Terrace, The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Tate Britain

Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

United Kingdom

Phone: +44 20 7887 8888

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00am – 18.00pm

Tate Britain website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Oscar Muñoz. 'El juego de las probabilidades' [The Game of Probabilities] 2007](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/el-juego-de-las-probabilidades-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994 Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/ambulatorio-web.jpg?w=840&h=555)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986 Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/cortinas-de-bac3b1o-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narcisos (en proceso)' [Narcissi (in process)] 1995-2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/narcisos-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001 Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/narciso-web.jpg?w=840&h=878)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004 Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/re_trato-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995 Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/aliento-web.jpg?w=840&h=687)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002 Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/la-mirada-del-cc3adclope-web.jpg?w=840&h=525)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011 Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/horizonte-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Fundido a blanco (dos retratos)' [Fade to White (Two Portraits)] 2010](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/fade-to-white-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Sedimentaciones' [Sedimentations] 2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/sedimentaciones-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-b-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-c-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

You must be logged in to post a comment.