Exhibition dates: 29th May 2016 – 2nd January 2017

Curators: Sarah Greenough, senior curator, department of photographs, and Philip Brookman, consulting curator, department of photographs, both National Gallery of Art, are the exhibition curators.

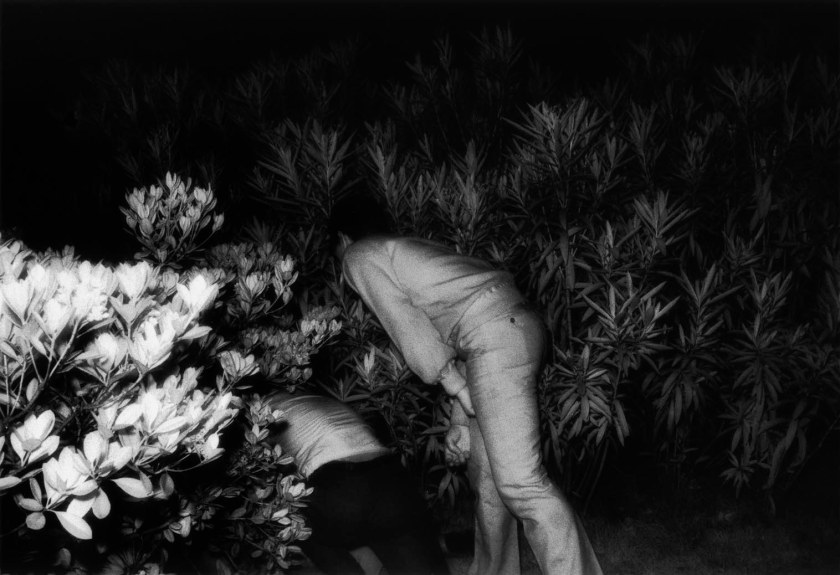

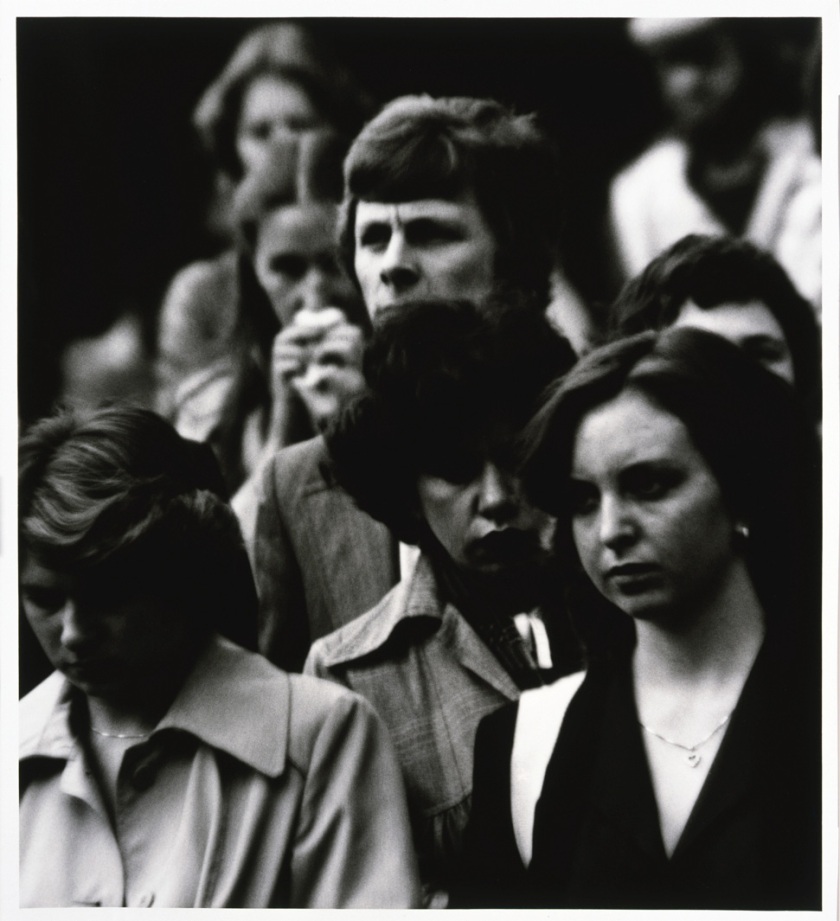

Louis Stettner (American, 1922-2016)

Times Square, New York City

1952-1954

Gelatin silver print

Sheet (trimmed to image): 42.1 x 27.5cm (16 9/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

The last posting of a fruitful year for Art Blart. I wish all the readers of Art Blart a happy and safe New Year!

The exhibition is organised around five themes – movement, sequence, narrative, studio, and identity – found in the work of Muybridge and Stieglitz, themes then developed in the work of other artists. While there is some interesting work in the posting, the conceptual rationale and stand alone nature of the themes and the work within them is a curatorial ordering of ideas that, in reality, cannot be contained within any one boundary, the single point of view.

Movement can be contained in sequences; narrative can be unfolded in a sequence (as in the work of Duane Michals); narrative and identity have a complex association which can also be told through studio work (eg. Gregory Crewdson), etc… What does Roger Mayne’s Goalie, Street Football, Brindley Road (1956, below) not have to do with identity, the young lad with his dirty hands, playing in his socks, in a poverty stricken area of London; why has Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Oscar Wilde (1999, below) been included in the studio section when it has much more to do with the construction of identity through photography – “Triply removing his portrait from reality – from Oscar Wilde himself to a portrait photograph to a wax sculpture and back to a photograph” – which confounds our expectations of the nature of photography. Photography is nefariously unstable in its depiction of an always, constructed reality, through representation(s) which reject simple causality.

To isolate and embolden the centre is to disclaim and disavow the periphery, work which crosses boundaries, is multifaceted and multitudinous; work which forms a nexus for networks of association beyond borders, beyond de/lineation – the line from here to there. The self-contained themes within this exhibition are purely illusory.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“We can no longer accept that the identity of a man can be adequately established by preserving and fixing what he looks like from a single viewpoint in one place.”

John Berger. “No More Portraits,” in New Society August 1967

“Intersections: Photographs and Videos from the National Gallery of Art and the Corcoran Gallery of Art explores the connections between the two newly joined photography collections. On view from May 29, 2016, through January 2, 2017, the exhibition is organised around themes found in the work of the two pioneers of each collection: Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904) and Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). Inspired by these two seminal artists, Intersections brings together more than 100 highlights of the recently merged collections by a range of artists from the 1840s to today.

Just as the nearly 700 photographs from Muybridge’s groundbreaking publication Animal Locomotion, acquired by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in 1887, became the foundation for the institution’s early interest in photography, the Key Set of more than 1,600 works by Stieglitz, donated by Georgia O’Keeffe and the Alfred Stieglitz Estate, launched the photography collection at the National Gallery of Art in 1949.”

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

Exhibition highlights

The exhibition is organised around five themes – movement, sequence, narrative, studio, and identity – found in the work of Muybridge and Stieglitz.

Movement

Works by Muybridge, who is best known for creating photographic technologies to stop and record motion, anchor the opening section devoted to movement. Photographs by Berenice Abbott and Harold Eugene Edgerton, which study how objects move through space, are included, as are works by Roger Mayne, Alexey Brodovitch, and other who employed the camera to isolate an instant from the flux of time.

Wall text

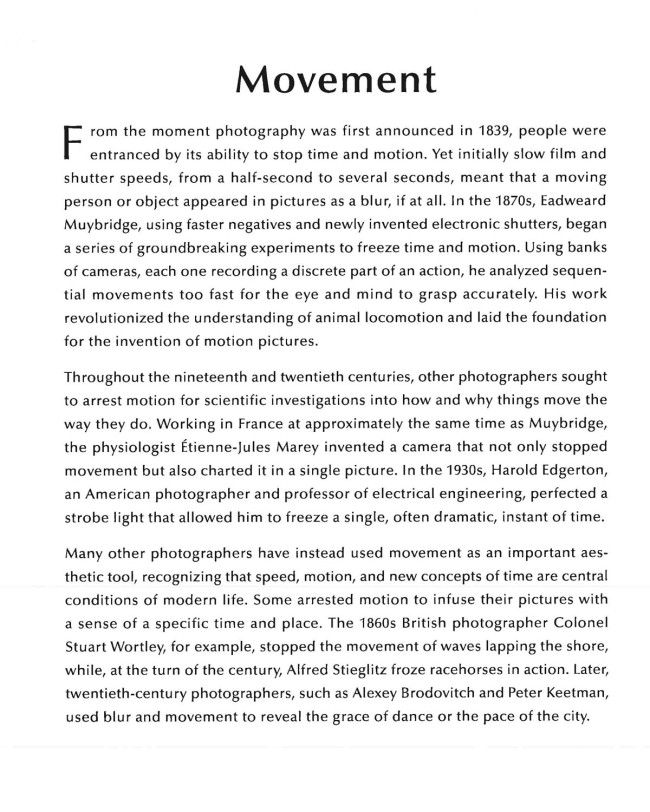

Eadweard Muybridge (English, 1830-1904)

Horses. Running. Phyrne L. No. 40, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion

1879

Albumen print

Image: 16 x 22.4cm (6 5/16 x 8 13/16 in.)

Sheet: 25.7 x 32.4cm (10 1/8 x 12 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon

In order to analyse the movement of racehorses, farm animals, and acrobats, Muybridge pioneered new and innovative ways to stop motion with photography. In 1878, he started making pictures at railroad magnate Leland Stanford’s horse farm in Palo Alto, California, where he developed an electronic shutter that enabled exposures as fast as one-thousandth of a second. In this print from Muybridge’s 1881 album The Attitudes of Animals in Motion, Stanford’s prized racehorse Phryne L is shown running in a sequential grid of pictures made by 24 different cameras with electromagnetic shutters tripped by wires as the animal ran across the track. These pictures are now considered a critical step in the development of cinema.

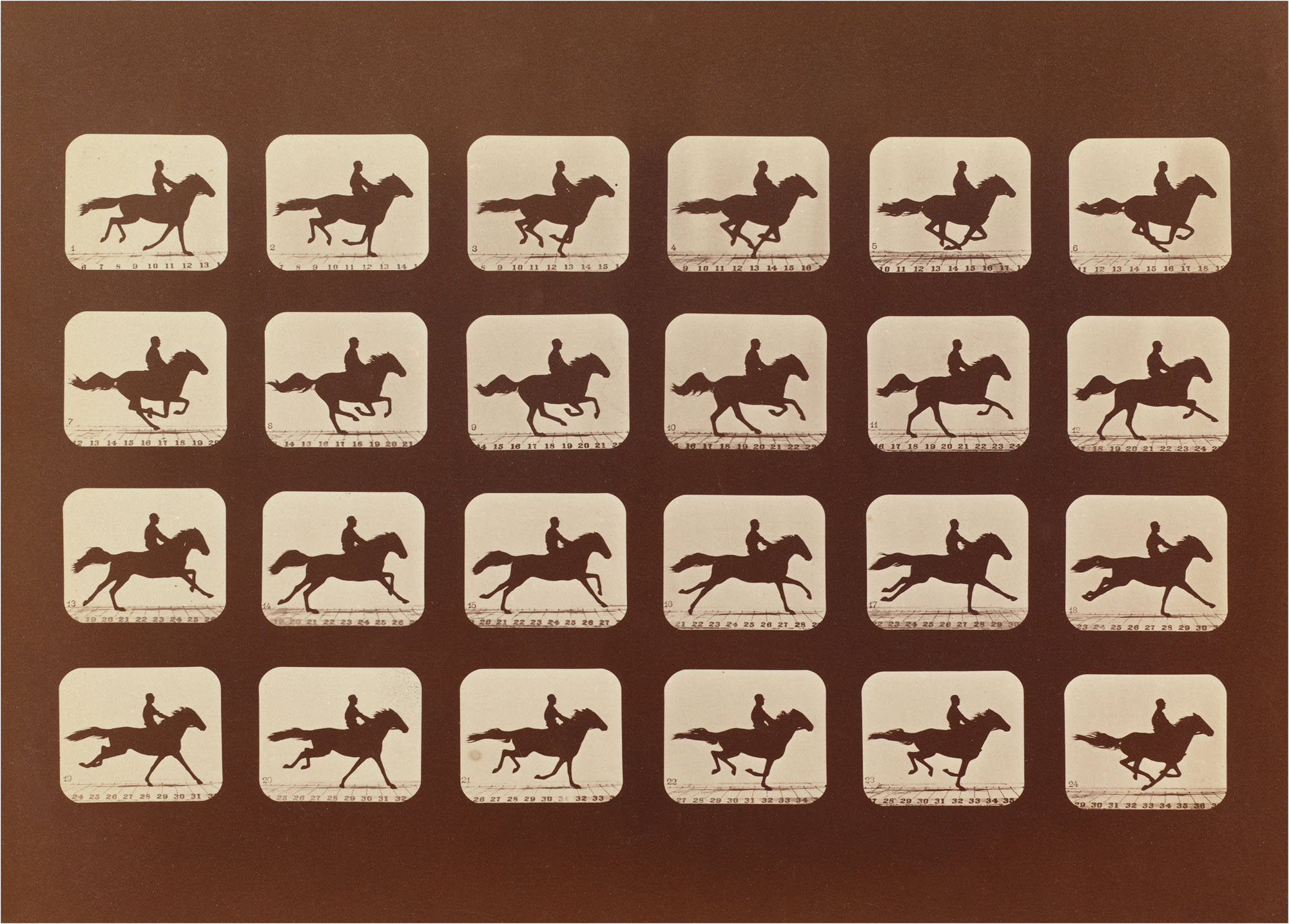

Eadweard Muybridge (English, 1830-1904)

Internegative for Horses. Trotting. Abe Edgington. No. 28, from The Attitudes of Animals in Motion

1878

Collodion negative

Overall (glass plate): 15.3 x 25.4cm (6 x 10 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon and Patrons’ Permanent Fund

This glass negative shows the sequence of Leland Stanford’s horse Abe Edgington trotting across a racetrack in Palo Alto, California – a revolutionary record of the changes in the horse’s gait in about one second. Muybridge composed the negative from photographs made by eight different cameras lined up to capture the horse’s movements. Used to print the whole sequence together onto albumen paper, this internegative served as an intermediary step in the production of Muybridge’s 1881 album The Attitudes of Animals in Motion.

Étienne Jules Marey (French, 1830-1904)

Chronophotograph of a Man on a Bicycle

c. 1885-1890

Glass lantern slide

Image: 4 x 7.5cm (1 9/16 x 2 15/16 in.)

Plate: 8.8 x 10.2cm (3 7/16 x 4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and David Robinson

A scientist and physiologist, Marey became fascinated with movement in the 1870s. Unlike Muybridge, who had already made separate pictures of animals in motion, Marey developed in 1882 a means to record several phases of movement onto one photographic plate using a rotating shutter with slots cut into it. He called this process “chronophotography,” meaning photography of time. His photographs, which he published in books and showed in lantern slide presentations, influenced 20th-century cubist, futurist, and Dada artists who examined the interdependence of time and space.

William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877)

The Boulevards of Paris

1843

Salted paper print

Image: 16.6 × 17.1cm (6 9/16 × 6 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 19 × 23.2cm (7 1/2 × 9 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, New Century Fund

As soon as Talbot announced his invention of photography in 1839, he realised that its ability to freeze time enabled him to present the visual spectacle of the world in an entirely new way. By capturing something as mundane as a fleeting moment on a busy street, he could transform life into art, creating a picture that could be savoured long after the event had transpired.

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

Colinton Manse and weir, with part of the old mill on the right

1843-1847

Salted paper print

Image: 20.7 x 14.6cm (8 1/8 x 5 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Paul Mellon Fund

In 1843, only four years after Talbot announced his negative / positive process of photography, painter David Octavius Hill teamed up with engineer Robert Adamson. Working in Scotland, they created important early portraits of the local populace and photographed Scottish architecture, rustic landscapes, and city scenes. Today a suburb southwest of Edinburgh, 19th-century Colinton was a mill town beside a river known as the Water of Leith. Because of the long exposure time required to make this photograph, the water rushing over a small dam appears as a glassy blur.

Thomas Annan (Scottish, 1829-1887)

Old Vennel, Off High Street

1868-1871

Carbon print

Image: 26.9 x 22.3cm (10 9/16 x 8 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 50.8 x 37.9cm (20 x 14 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

In 1868, Glasgow’s City Improvements Trust hired Annan to photograph the “old closes and streets of Glasgow” before the city’s tenements were demolished. Annan’s pictures constitute one of the first commissioned photographic records of living conditions in urban slums. The collodion process Annan used to make his large, glass negatives required a long exposure time. In the dim light of this narrow passage, it was impossible for the photographer to stop the motion of the restless children, who appear as ghostly blurs moving barefoot across the cobblestones.

Thomas Annan (Scottish, 1829-1887)

Old Vennel, Off High Street (detail)

1868-1871

Carbon print

Image: 26.9 x 22.3cm (10 9/16 x 8 3/4 in.)

Sheet: 50.8 x 37.9cm (20 x 14 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

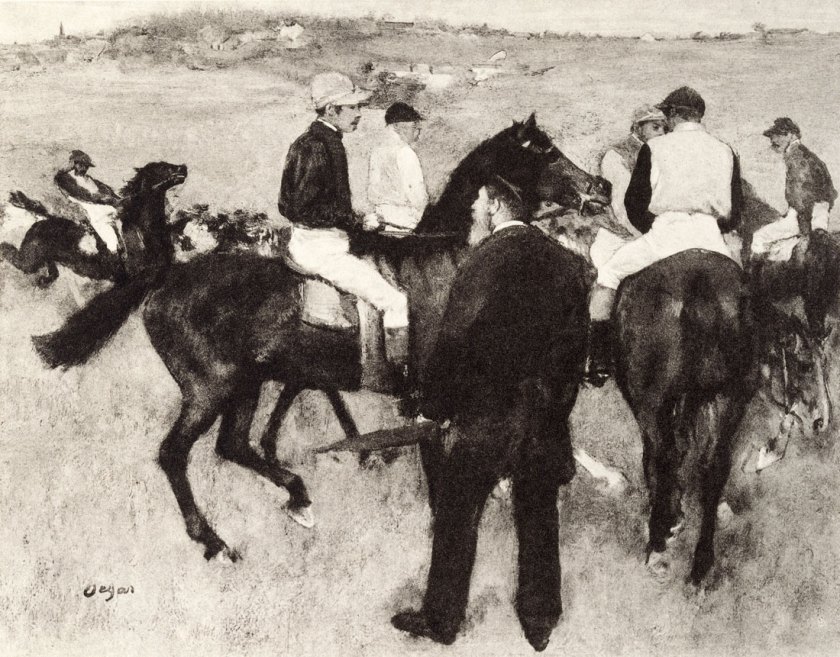

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Going to the Post, Morris Park

1904

Photogravure

Image: 30.8 x 26.4cm (12 1/8 x 10 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 38.5 x 30.3cm (15 3/16 x 11 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

In the 1880s and 1890s, improvements in photographic processes enabled manufacturers to produce small, handheld cameras that did not need to be mounted on tripods. Faster film and shutter speeds also allowed practitioners to capture rapidly moving objects. Stieglitz was one of the first fine art photographers to exploit the aesthetic potential of these new cameras and films. Around the turn of the century, he made many photographs of rapidly moving trains, horse-drawn carriages, and racetracks that capture the pace of the increasingly modern city.

Harold Eugene Edgerton (American, 1903-1990)

Wes Fesler Kicking a Football

1934

Gelatin silver print

Image: 11 1/2 x 9 5/8 in.

Sheet: 13 15/16 x 11 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with the aid of funds from the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and The Polaroid Corporation)

A professor of electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Edgerton in the early 1930s invited the stroboscope, a tube filled with gas that produced high-intensity bursts of light at regular and very brief intervals. He used it to illuminate objects in motion so that they could be captured by a camera. At first he was hired by industrial clients to reveal flaws in their production of materials, but by the mid-1930s he began to photography everyday events… Edgerton captured phenomena moving too fast for the naked eye to see, and revealed the beauty of people and objects in motion.

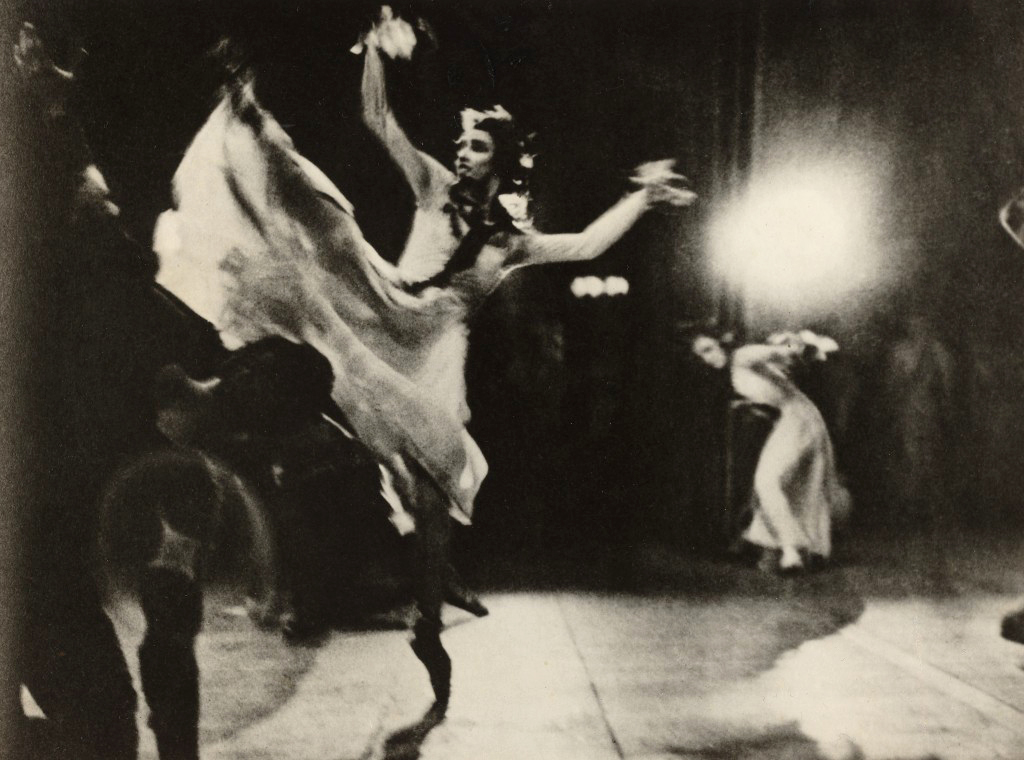

Alexey Brodovitch (American born Russia, 1898-1971)

Untitled from “Ballet” series

1938

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 20.4 x 27.5cm (8 1/16 x 10 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Diana and Mallory Walker Fund

A graphic artist, Russian-born Brodovitch moved to the United States from Paris in 1930. Known for his innovative use of photographs, illustrations, and type on the printed page, he became art director for Harper’s Bazaar in 1934, and photographed the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo during their American tours from 1935 to 1939. Using a small-format, 35 mm camera, Brodovitch worked in the backstage shadows and glaring light of the theatre to produce a series of rough, grainy pictures that convey the drama and action of the performance. This photograph employs figures in motion, a narrow field of focus, and high-contrast effects to express the stylised movements of Léonide Massine’s 1938 choreography for Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony.

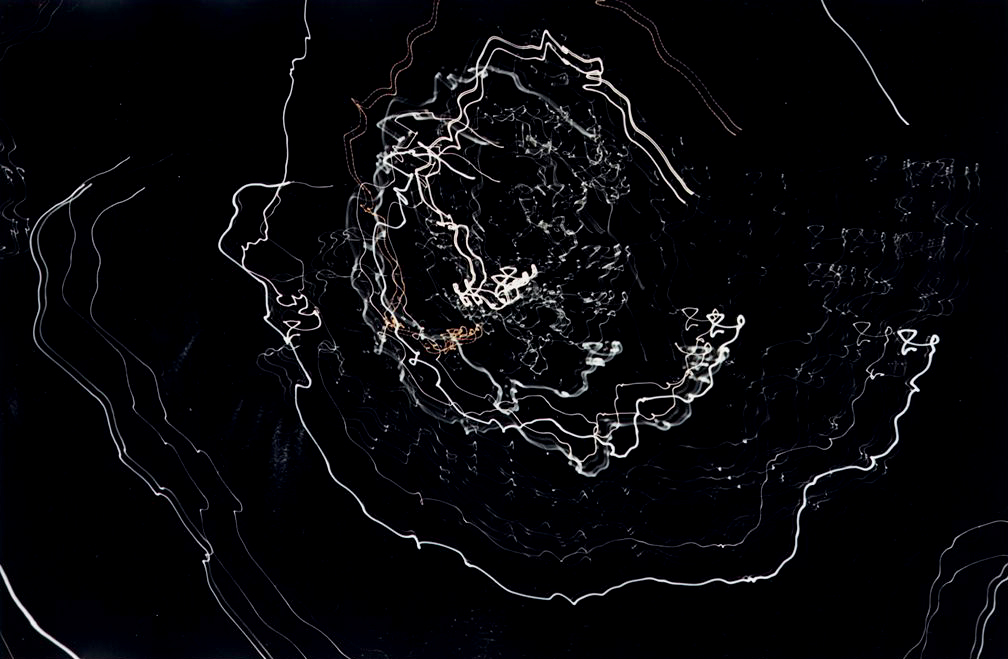

Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999)

Detroit

c. 1943

Dye imbibition print, printed c. 1980

Overall (image): 18 x 26.7cm (7 1/16 x 10 1/2 in.)

Sheet: 27.31 x 36.83cm (10 3/4 x 14 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Callahan Family

Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999)

Camera Movement on Neon Lights at Night

1946

Dye imbibition print, printed 1979

Image: 8 3/4 x 13 5/8 in.

Sheet: 10 3/8 x 13 15/16 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Richard W. and Susan R. Gessner)

Frank Horvat (Italian, 1928-2020)

Paris, Gare Saint-Lazare

1959

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 39.3 x 26.2cm (15 1/2 x 10 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

Gare Saint-Lazare is one of the principal railway stations in Paris. Because of its industrial appearance, steaming locomotives, and teeming crowds, it was a frequent subject for 19th-century French painters – including Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and Gustave Caillebotte – who used it to express the vitality of modern life. 20th-century artists such as Horvat also depicted it to address the pace and anonymity that defined their time. Using a telephoto lens and long exposure, he captured the rushing movement of travellers scattered beneath giant destination signs.

Roger Mayne (English, 1929-2014)

Goalie, Street Football, Brindley Road

1956

Gelatin silver print

Image: 34.7 × 29.1cm (13 11/16 × 11 7/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

From 1956 to 1961, Mayne photographed London’s North Kensington neighbourhood to record its emergence from the devastation and poverty caused by World War II. This dramatic photograph of a young goalie lunging for the ball during an after-school soccer game relies on the camera’s ability to freeze the fast-paced and unpredictable action. Because the boy’s daring lunge is forever suspended in time, we will never know its outcome.

Shōmei Tōmatsu (Japanese, 1930-2012)

Rush Hour, Tokyo (detail)

1981

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 11 5/16 x 9 7/16 in. (28.73 x 23.97 cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Michael D. Abrams)

Best known for his expressive documentation of World War II’s impact on Japanese culture, Tomatsu was one of Japan’s most creative and influential photographers. Starting in the early 1960s, he documented the country’s dramatic economic, political, and cultural transformation. This photograph – a long exposure made with his camera mounted on a tripod – conveys the chaotic rush of commuters on their way through downtown Tokyo. Tomatsu used this graphic description of movement, which distorts the faceless bodies of commuters dashing down a flight of stairs, to symbolise the dehumanising nature of work in the fast-paced city of the early 1980s.

Sequence

Muybridge set up banks of cameras and used electronic shutters triggered in sequence to analyse the motion of people and animals. Like a storyteller, he sometimes adjusted the order of images for visual and sequential impact. Other photographers have also investigated the medium’s capacity to record change over time, express variations on a theme, or connect seemingly disparate pictures. In the early 1920s, Stieglitz began to create poetic sequences of cloud photographs meant to evoke distinct emotional experiences. These works (later known as Equivalents) influenced Ansel Adams and Minor White – both artists created specific sequences to evoke the rhythms of nature or the poetry of time passing.

Wall text

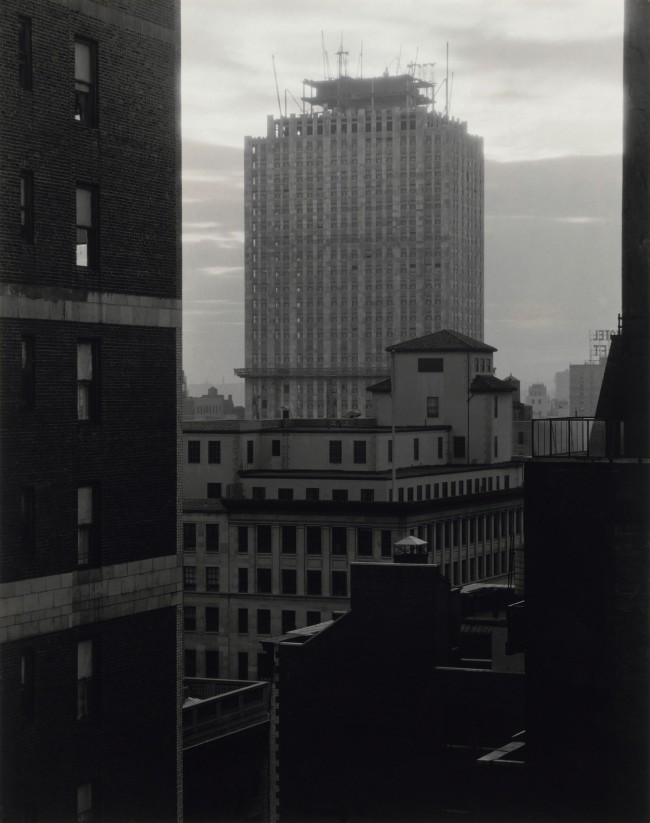

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

From My Window at An American Place, Southwest

March 1932

Gelatin silver print

Sheet (trimmed to image): 23.8 x 18.4cm (9 3/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

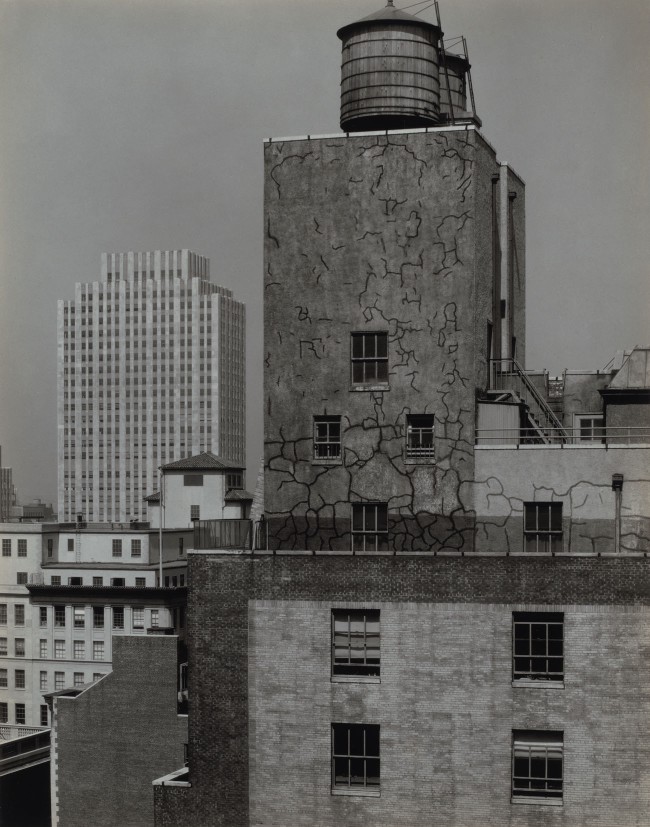

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

From My Window at An American Place, Southwest

April 1932

Gelatin silver print

Sheet (trimmed to image): 23.8 x 18.8cm (9 3/8 x 7 3/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Water Tower and Radio City, New York

1933

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 23.7 x 18.6cm (9 5/16 x 7 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Whenever Stieglitz exhibited his photographs of New York City made in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he grouped them into series that record views from the windows of his gallery, An American Place, or his apartment at the Shelton Hotel, showing the gradual growth of the buildings under construction in the background. Although he delighted in the formal beauty of the visual spectacle, he lamented that these buildings, planned in the exuberance of the late 1920s, continued to be built in the depths of the Depression, while “artists starved,” as he said at the time, and museums were “threatened with closure.”

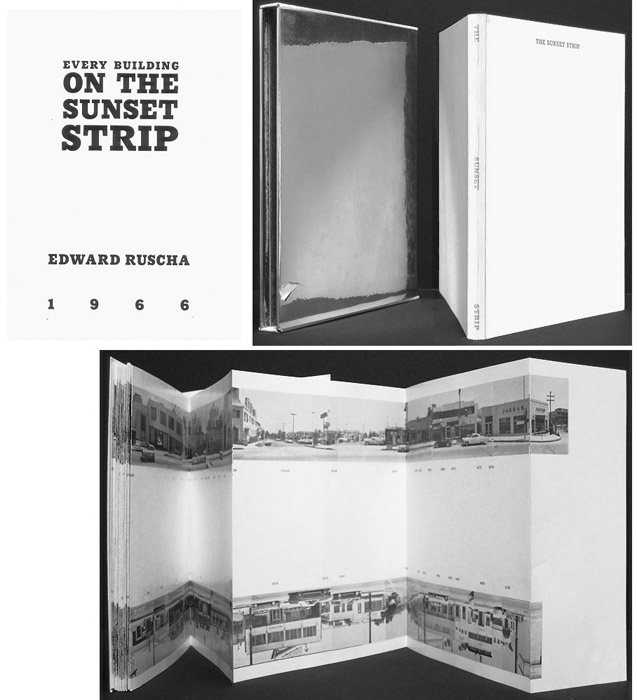

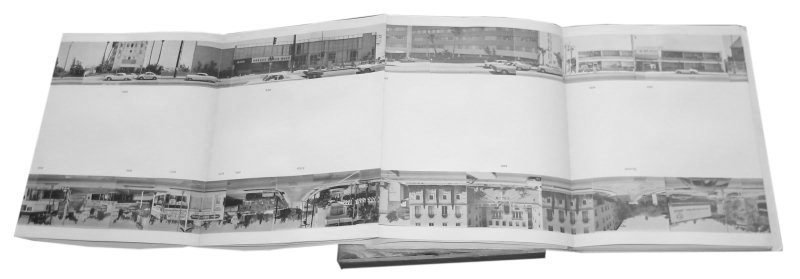

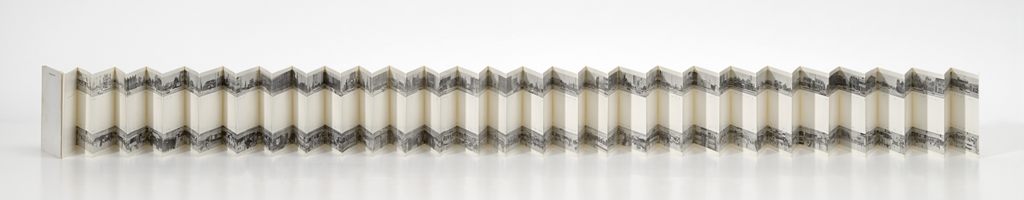

Ed Ruscha (American, b. 1937)

Every Building on the Sunset Strip

1966

Offset lithography book: 7 x 5 3/4 in. (17.78 x 14.61cm)

Unfolded (open flat): 7 x 276 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Philip Brookman and Amy Brookman)

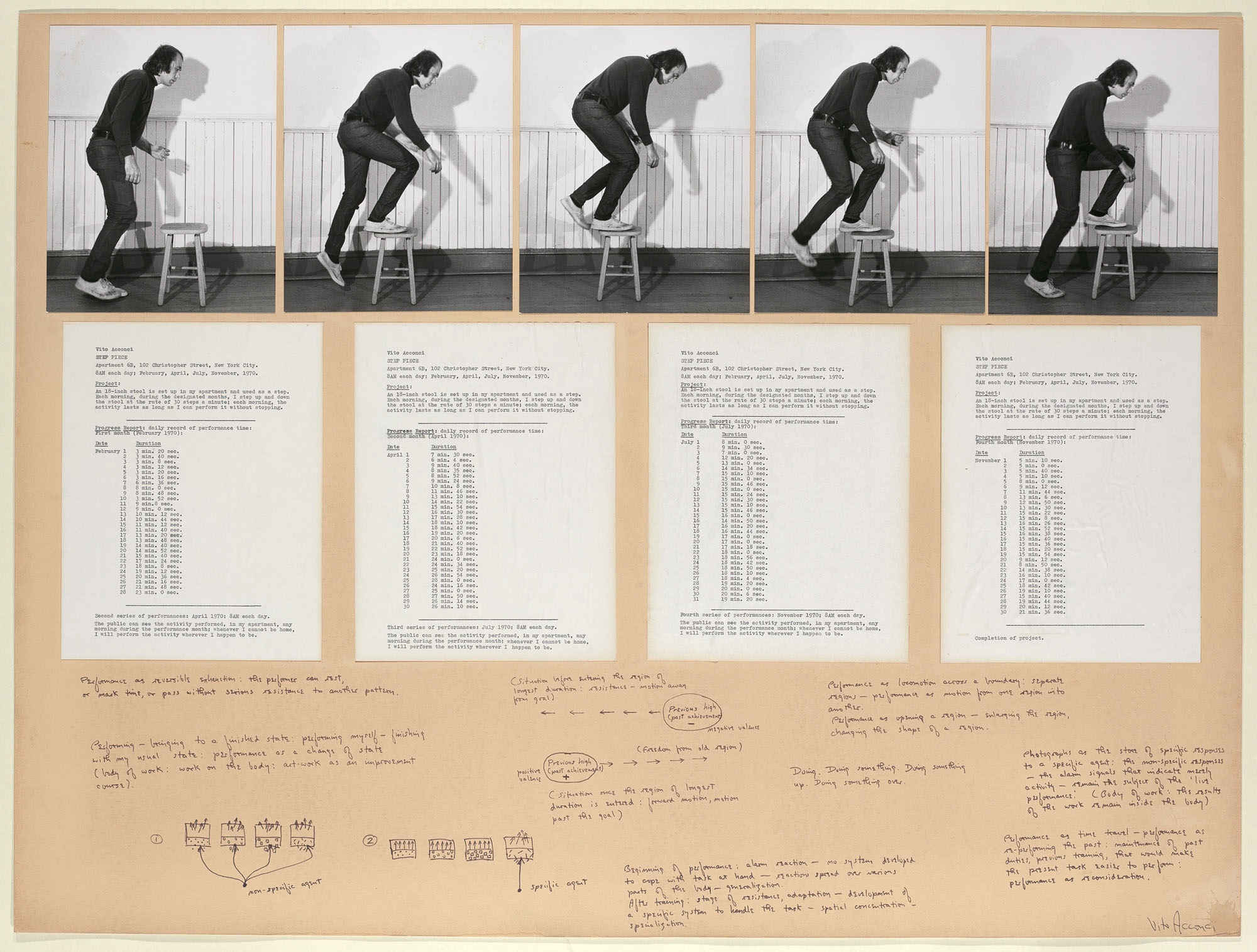

Vito Acconci (American, 1940-2017)

Step Piece

1970

Five gelatin silver prints and four sheets of type-written paper, mounted on board with annotations in black ink

Sheet: 76.2 x 101.6cm (30 x 40 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Dorothy and Herbert Vogel Collection

Acconci’s Step Piece is made up of equal parts photography, drawing, performance, and quantitative analysis. It documents a test of endurance: stepping on and off a stool for as long as possible every day. This performance-based conceptual work is rooted in the idea that the body itself can be a medium for making art. To record his activity, Acconci made a series of five photographs spanning one complete action. Like the background grid in many of Muybridge’s motion studies, vertical panels in Acconci’s studio help delineate the space. His handwritten notes and sketches suggest the patterns of order and chaos associated with the performance, while typewritten sheets, which record his daily progress, were given to people who were invited to observe.

Narrative

The exhibition also explores the narrative possibilities of photography found in the interplay of image and text in the work of Robert Frank, Larry Sultan, and Jim Goldberg; the emotional drama of personal crisis in Nan Goldin’s image grids; or the expansion of photographic description into experimental video and film by Victor Burgin and Judy Fiskin.

Wall text

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Judith Being Carted from Oaklawn to the Hill. The Way Art Moves

1920

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 18.8cm (9 1/2 x 7 3/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.2 x 20.1cm (9 15/16 x 7 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

In 1920, Stieglitz’s family sold their Victorian summerhouse on the shore of Lake George, New York, and moved to a farmhouse on a hill above it. This photograph shows three sculptures his father had collected – two 19th-century replicas of ancient statues and a circa 1880 bust by Moses Ezekiel depicting the Old Testament heroine Judith – as they were being moved in a wooden cart from one house to another. Stieglitz titled it The Way Art Moves, wryly commenting on the low status of art in American society. With her masculine face and bared breast, Judith was much maligned by Georgia O’Keeffe and other younger family members. In a playful summer prank, they later buried her somewhere near the farmhouse, where she remained lost, despite many subsequent efforts by the perpetrators themselves to find her.

Dan Graham (American, b. 1942)

Homes for America

1966-1967

Two chromogenic prints

Image (top): 23 x 34cm (9 1/16 x 13 3/8 in.)

Image (bottom): 27.8 x 34cm (10 15/16 x 13 3/8 in.)

Mount: 101 x 75cm (39 3/4 x 29 1/2 in.)

Framed: 102 x 76.2 x 2.8cm (40 3/16 x 30 x 1 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Glenstone in honour of Eileen and Michael Cohen

Beginning in the mid-1960s, conceptual artist Dan Graham created several works of art for magazine pages and slide shows. When Homes for America was designed for Arts magazine in 1966, his accompanying text critiqued the mass production of cookie-cutter homes, while his photographs – made with an inexpensive Kodak Instamatic camera – described a suburban world of offices, houses, restaurants, highways, and truck stops. With their haphazard composition and amateur technique, Graham’s pictures ironically scrutinised the aesthetics of America’s postwar housing and inspired other conceptual artists to incorporate photographs into their work. Together, these two photographs link a middle-class family at the opening of a Jersey City highway restaurant with the soulless industrial landscape seen through the window.

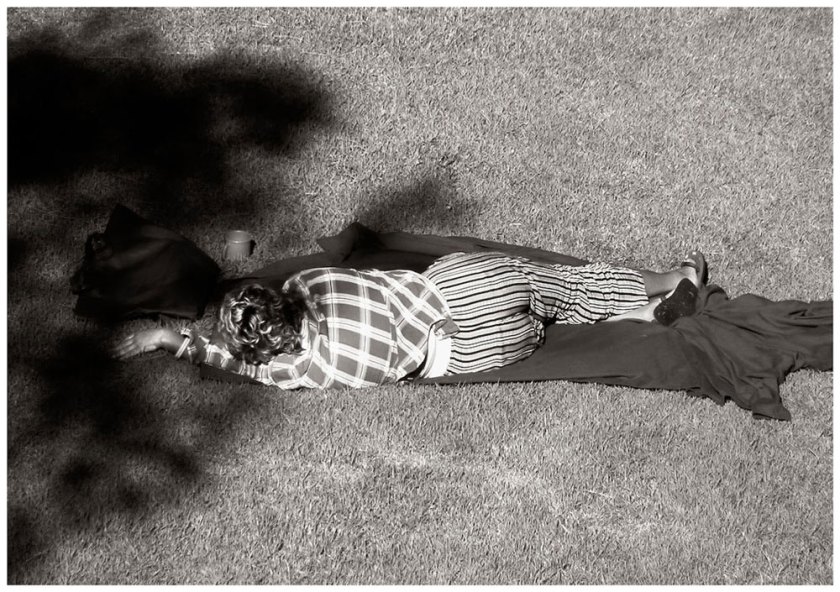

Larry Sultan (American, 1946-2009)

Thanksgiving Turkey/Newspaper (detail)

1985-1992

Two plexiglass panels with screen printing

Framed (Thanksgiving Turkey): 76 × 91cm (29 15/16 × 35 13/16 in.)

Framed (Newspaper): 76 × 91cm (29 15/16 × 35 13/16 in.)

Other (2 text panels): 50.8 × 76.2cm (20 × 30 in.)

Overall: 30 x 117 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the FRIENDS of the Corcoran Gallery of Art)

From 1983 to 1992, Sultan photographed his parents in retirement at their Southern California house. His innovative book, Pictures from Home, combines his photographs and text with family album snapshots and stills from home movies, mining the family’s memories and archives to create a universal narrative about the American dream of work, home, and family. Thanksgiving Turkey/Newspaper juxtaposes photographs of his mother and father, each with their face hidden and with adjacent texts where they complain about each other’s shortcomings. “I realise that beyond the rolls of film and the few good pictures … is the wish to take photography literally,” Sultan wrote. “To stop time. I want my parents to live forever.”

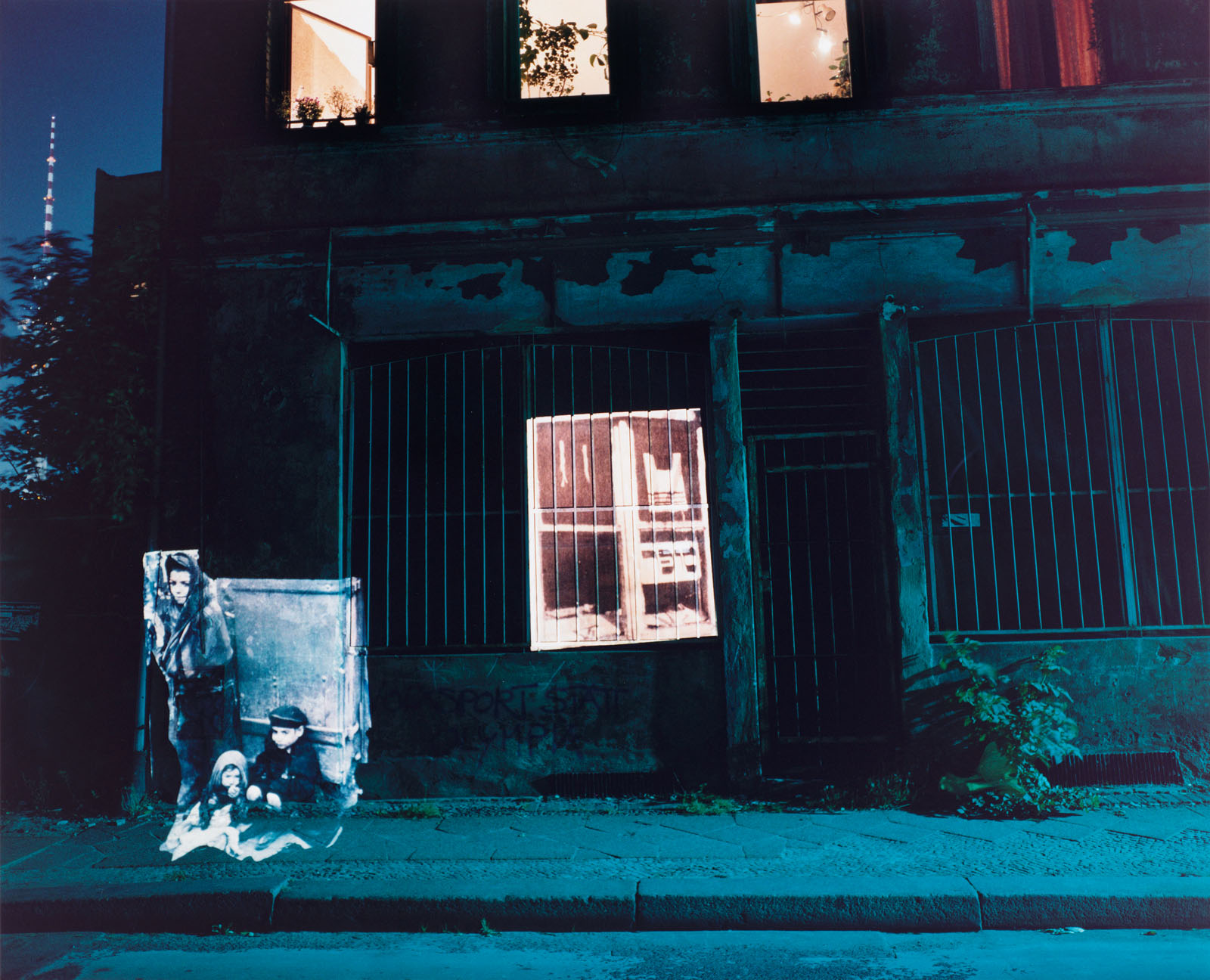

Shimon Attie (American, b. 1957)

Mulackstrasse 32: Slide Projections of Former Jewish Residents and Hebrew Reading Room, 1932, Berlin

1992

Chromogenic print

Unframed: 20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 60.96cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Julia J. Norrell in honor of Hilary Allard and Lauren Harry)

Attie projected historical photographs made in 1932 onto the sides of a building at Mulackstrasse 32, the site of a Hebrew reading room in a Jewish neighbourhood in Berlin during the 1930s. Fusing pictures made before Jews were removed from their homes and killed during World War II with photographs of the same dark, empty street made in 1992, Attie has created a haunting picture of wartime loss.

Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953)

Relapse/Detox Grid

1998-2000

Nine silver dye bleach prints

Overall: 42 1/2 x 62 1/8 in. (107.95 x 157.8cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with funds donated by the FRIENDS of the Corcoran Gallery of Art)

Goldin has unsparingly chronicled her own community of friends by photographing their struggles, hopes, and dreams through years of camaraderie, abuse, addiction, illness, loss, and redemption. Relapse/Detox Grid presents nine colourful yet plaintive pictures in a slide show-like narrative, offering glimpses of a life rooted in struggle, along with Goldin’s own recovery at a detox center, seen in the bottom row.

Nan Goldin (American, b. 1953)

Relapse/Detox Grid (detail)

1998-2000

Nine silver dye bleach prints

Overall: 42 1/2 x 62 1/8 in. (107.95 x 157.8cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with funds donated by the FRIENDS of the Corcoran Gallery of Art)

Victor Burgin (British, b. 1941)

Watergate

2000

Video with sound, 9:58 minutes

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, with funds from the bequest of Betty Battle to the Women’s Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of Art)

An early advocate of conceptual art, Burgin is an artist and writer whose work spans photographs, text, and video. Watergate shows how the meaning of art can change depending on the context in which it is seen. Burgin animated digital, 160-degree panoramic photographs of nineteenth-century American art hanging in the Corcoran Gallery of Art and in a hotel room. While the camera circles the gallery, an actor reads from Jean-Paul Satre’s Being and Nothingness, which questions the relationship between presence and absence. Then a dreamlike pan around a hotel room overlooking the nearby Watergate complex mysteriously reveals Niagara, the Corcoran’s 1859 landscape by Frederic Church, having on the wall. In 1859, Niagara Falls was seen as a symbol of the glory and promise of the American nation, yet when Church’s painting is placed in the context of the Watergate, an icon of the scandal that led to Richard Nixon’s resignation, it assumes a different meaning and suggests an ominous sense of disillusionment.

Studio

Intersections also examines the studio as a locus of creativity, from Stieglitz’s photographs of his gallery, 291, and James Van Der Zee’s commercial studio portraits, to the manipulated images of Wallace Berman, Robert Heinecken, and Martha Rosler. Works by Laurie Simmons, David Levinthal, and Vik Muniz also highlight the postmodern strategy of staging images created in the studio.

Wall text

Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

Self-Portrait with Wife Ernestine in a Balloon Gondola

c. 1865

Gelatin silver print, printed c. 1890

8.6 × 7.7cm (3 3/8 × 3 1/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation through Robert and Joyce Menschel

Nadar (a pseudonym for Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) was not only a celebrated portrait photographer, but also a journalist, caricaturist, and early proponent of manned flight. In 1863, he commissioned a prominent balloonist to build an enormous balloon 196 feet high, which he named The Giant. The ascents he made from 1863 to 1867 were widely covered in the press and celebrated by the cartoonist Honoré Daumier, who depicted Nadar soaring above Paris, its buildings festooned with signs for photography studios. Nadar made and sold small prints like this self-portrait to promote his ballooning ventures. The obviously artificial construction of this picture – Nadar and his wife sit in a basket far too small for a real ascent and are posed in front of a painted backdrop – and its untrimmed edges showing assistants at either side make it less of the self-aggrandising statement that Nadar wished and more of an amusing behind-the-scenes look at studio practice.

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Self-Portrait

probably 1911

Platinum print

Image: 24.2 x 19.3cm (9 1/2 x 7 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.3 x 20.3cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

Unlike many other photographers, Stieglitz made few self-portraits. He created this one shortly before he embarked on a series of portraits of the artists who frequented his New York gallery, 291. Focusing only on his face and leaving all else in shadow, he presents himself not as an artist at work or play, but as a charismatic leader who would guide American art and culture into the 20th century.

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

291 – Picasso-Braque Exhibition

1915

Platinum print

Image: 18.5 x 23.6 cm (7 5/16 x 9 5/16 in.)

Sheet: 20.1 x 25.3 cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Alfred Stieglitz Collection

291 was Stieglitz’s legendary gallery in New York City (its name derived from its address on Fifth Avenue), where he introduced modern European and American art and photography to the American public. He also used 291 as a studio, frequently photographing friends and colleagues there, as well as the views from its windows. This picture records what Stieglitz called a “demonstration” – a short display of no more than a few days designed to prompt a focused discussion. Including two works by Picasso, an African mask from the Kota people, a wasps’ nest, and 291’s signature brass bowl, the photograph calls into question the relationship between nature and culture, Western and African art.

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983)

Sisters

1926

Gelatin silver print

Sheet (trimmed to image): 17.6 x 12.5cm (6 15/16 x 4 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation through Robert and Joyce Menschel

James Van Der Zee was a prolific studio photographer in Harlem during a period known as the Harlem Renaissance, from the end of World War I to the middle of the 1930s. He photographed many of Harlem’s celebrities, middle-class residents, and community organisations, establishing a visual archive that remains one of the best records of the era. He stands out for his playful use of props and retouching, thereby personalising each picture and enhancing the sitter’s appearance. In this portrait of three sisters, clasped hands show the tender bond of the two youngest, one of whom holds a celebrity portrait, revealing her enthusiasm for popular culture.

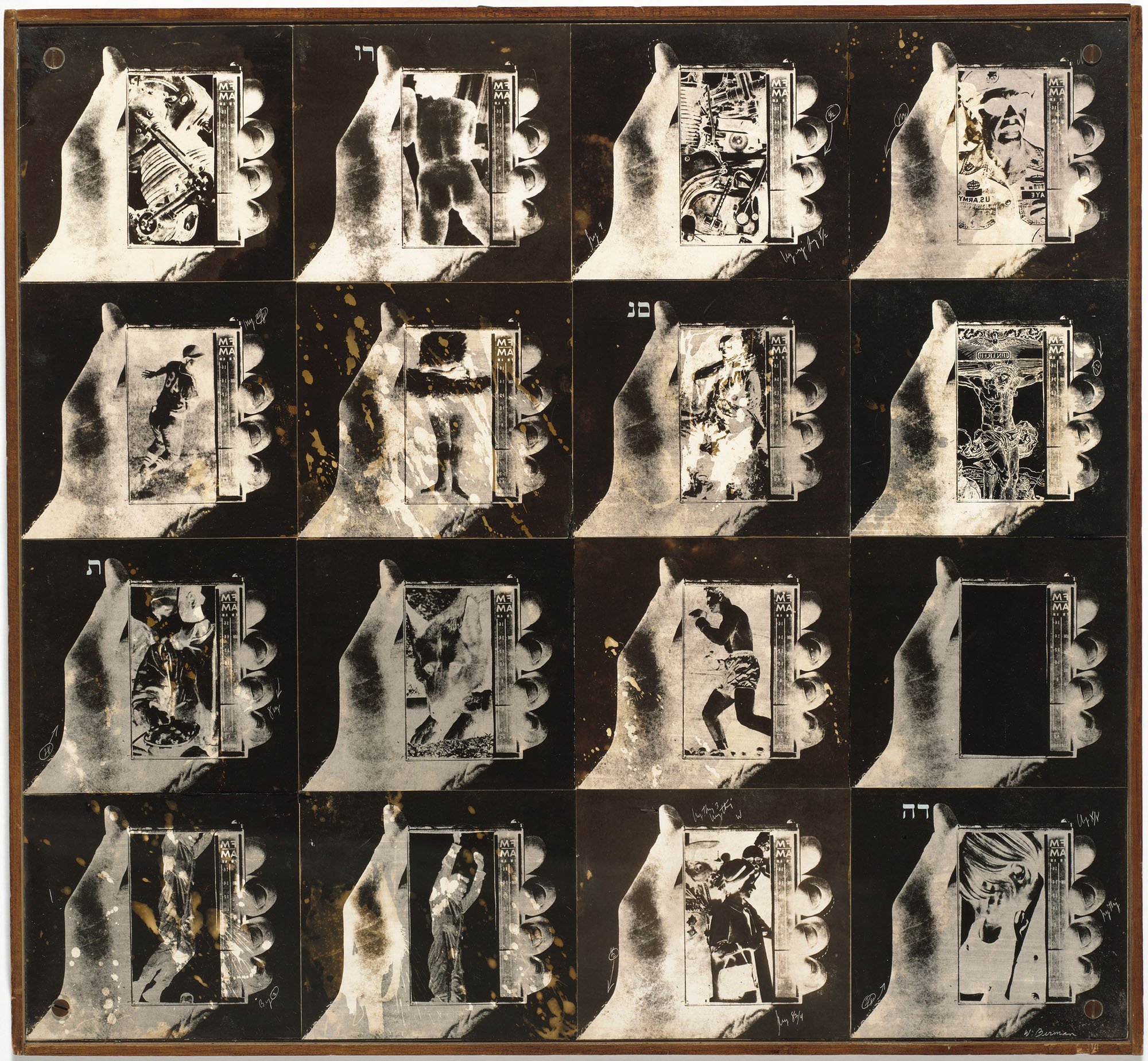

Wallace Berman (American, 1926-1976)

Silence Series #7

1965-1968

Verifax (wet process photocopy) collage

Actual: 24 1/2 x 26 1/2 in. (62.23 x 67.31cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, William A. Clark Fund)

An influential artist of California’s Beat Generation during the 1950s and 1960s, Berman was a visionary thinker and publisher of the underground magazine Semina. His mysterious and playful juxtapositions of divers objects, images, and texts were often inspired by Dada and surrealist art. Silence Series #7 presents a cinematic sequence of his trademark transistor radios, each displaying military, religious, or mechanical images along with those of athletes and cultural icons, such as Andy Warhol. Appropriated from mass media, reversed in tone, and printed backward using an early version of a photocopy machine, these found images, pieced together and recopied as photomontages, replace then ew transmitted through the radios. Beat poet Robert Duncan once called Berman’s Verify collages a “series of magic ‘TV’ lantern shows.”

Doug and Mike Starn (American)

Double Rembrandt (with steps)

1987-1991

Gelatin silver prints, ortho film, tape, wood, plexiglass, glue and silicone

2 interlocking parts:

Part 1 overall: 26 1/2 x 13 7/8 in.

Part 2 overall: 26 3/8 x 13 3/4 in.

Overall: 26 1/2 x 27 3/4 in.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Susan and Peter MacGill

Doug and Mike Starn, identical twins who have worked collaboratively since they were thirteen, have a reputation for creating unorthodox works. Using take, wood, and glue, the brothers assembles sheets of photographic film and paper to create a dynamic composition that includes an appropriated image of Rembrandt van Rijn’s Old Man with a Gold Chain (1631). Double Rembrandt (with steps) challenges the authority of the austere fine art print, as well as the aura of the original painting, while playfully invoking the twins’ own double identity.

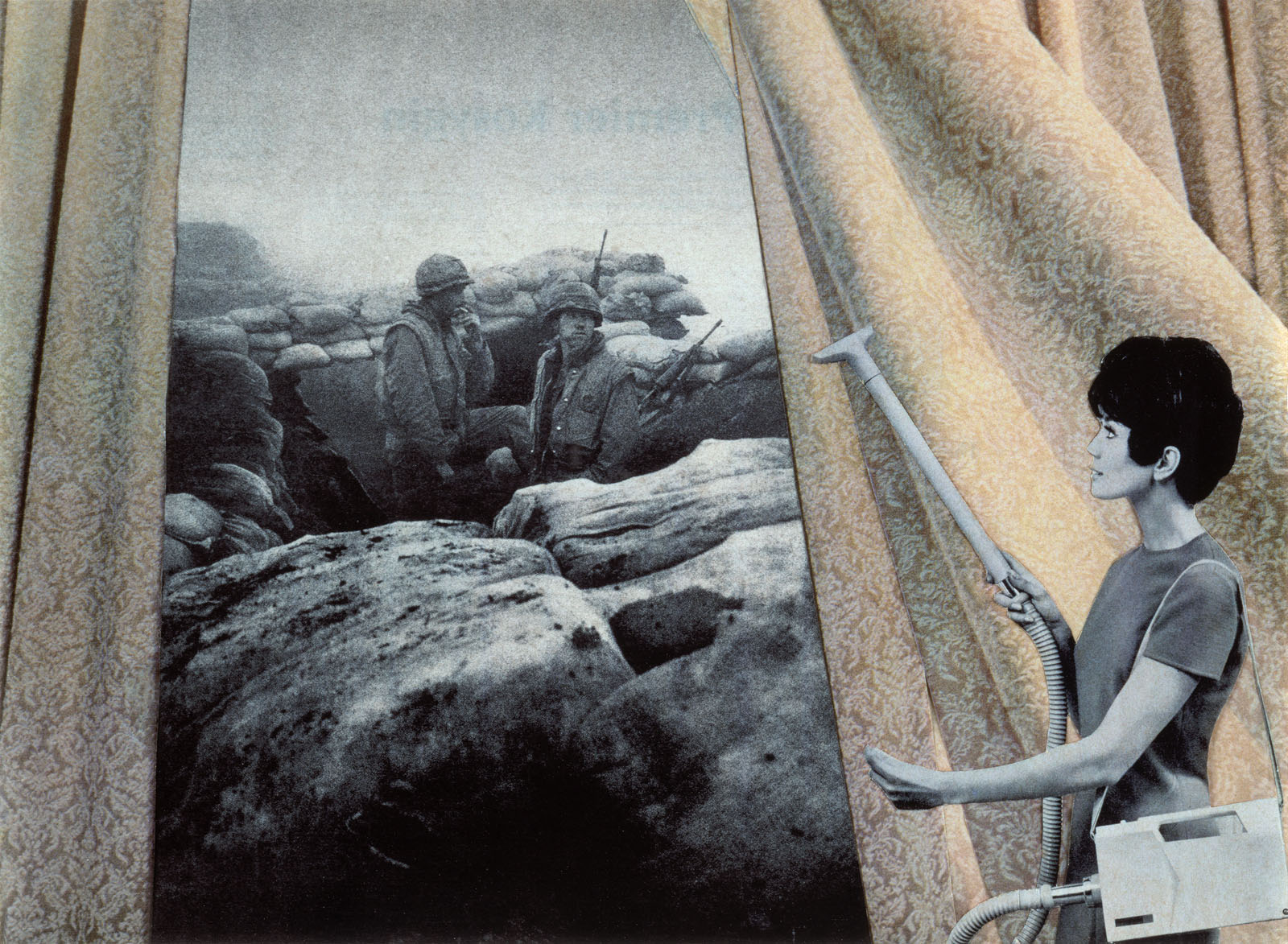

Martha Rosler (American, b. 1943)

Cleaning the Drapes, from the series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home

1967-1972

Inkjet print, printed 2007

Framed: 53.5 × 63.3cm (21 1/16 × 24 15/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee and the Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

A painter, photographer, video artist, feminist, activist writer, and teacher, Martha Rosler made this photomontage while she was a graduate student in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Frustrated by the portrayal of the Vietnam War on television and in other media, she wrote: “The images were always very far away and of a place we couldn’t imagine.” To bring “the war home,” as she announced in her title, she cut out images from Life magazine and House Beautiful to make powerfully layered collages that contrast American middle-class life with the realities of the war. She selected colour pictures of the idealised American life rich in the trappings of consumer society, and used black-and-white pictures of troops in Vietnam to heighten the contrast between here and there, while also calling attention to stereotypical views of men and women.

Sally Mann (American, b. 1951)

Self-Portrait

1974

Gelatin silver print

Image: 17 × 14.9cm (6 11/16 × 5 7/8 in.)

Sheet: 35 × 27.2cm (13 3/4 × 10 11/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Olga Hirshhorn)

Sally Mann, who is best known for the pictures of her children she made in the 1980s and 1990s, began to photograph when she was a teenager. In this rare, early, and intimate self-portrait, the artist is reflected in a mirror, clasping her loose shirt as she stands in a friend’s bathroom. Her thoughtful, expectant expression, coupled with her finger pointing directly at the lens of the large view camera that towers above her, foreshadows the commanding presence photography would have in her life.

David Levinthal (American, b. 1949)

Untitled (from the series Hitler Moves East)

1975

Gelatin silver print

Sheet: 15 15/16 x 20 in. (40.48 x 50.8cm)

Image: 10 9/16 x 13 7/16 in. (26.83 x 34.13cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the artist)

Levinthal’s series of photographs Hitler Moves East was made not during World War II, but in 1975, when the news media was saturated with images of the end of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. In this series, he appropriates the grainy look of photojournalism and uses toy soldiers and fabricated environments to stage scenes from Germany’s brutal campaign on the Eastern Front during World War II. His pictures are often based on scenes found in television and movies, further distancing them from the actual events. A small stick was used to prop up the falling soldier and the explosion was made with puffs of flour. Hitler Moves East casts doubt on the implied authenticity of photojournalism and calls attention to the power of the media to define public understanding of events.

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Oscar Wilde

1999

Gelatin silver print

Image: 148.59 × 119.6cm (58 1/2 × 47 1/16 in.)

Framed: 182.25 × 152.4cm (71 3/4 × 60 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of The Heather and Tony Podesta Collection)

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Oscar Wilde (detail)

1999

Gelatin silver print

Image: 148.59 × 119.6cm (58 1/2 × 47 1/16 in.)

Framed: 182.25 × 152.4cm (71 3/4 × 60 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of The Heather and Tony Podesta Collection)

While most traditional portrait photographers worked in studios, Sugimoto upended this practice in a series of pictures he made at Madame Tussaud’s wax museums in London and Amsterdam, where lifelike wax figures, based on paintings or photographs, as is the case with Oscar Wilde, are displayed in staged vignettes. By isolating the figure from its setting, posing it in a three-quarter-length view, illuminating it to convey the impression of a carefully lit studio portrait, and making his final print almost six feet tall, Sugimoto renders the artificial as real. Triply removing his portrait from reality – from Oscar Wilde himself to a portrait photograph to a wax sculpture and back to a photograph – Sugimoto collapses time and confounds our expectations of the nature of photography.

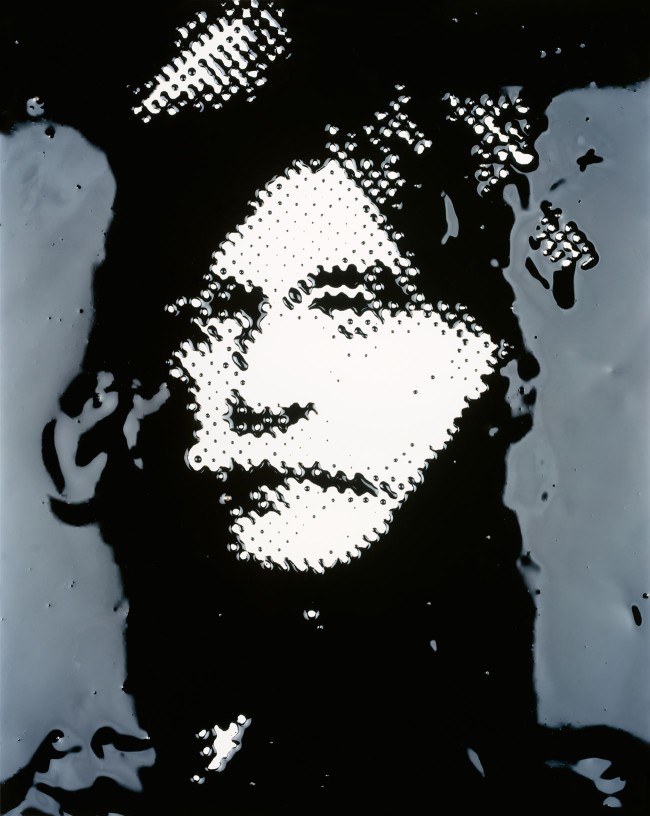

Vik Muniz (Brazilian, b. 1961)

Alfred Stieglitz (from the series Pictures of Ink)

2000

Silver dye bleach print

Image: 152.4 × 121.92cm (60 × 48 in.)

Framed: 161.29 × 130.81 × 5.08cm (63 1/2 × 51 1/2 × 2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase with funds provided by the FRIENDS of the Corcoran Gallery of Art)

Muniz has spent his career remaking works of art by artists as varied as Botticelli and Warhol using unusual materials – sugar, diamonds, and even junk. He has been especially interested in Stieglitz and has re-created his photographs using chocolate syrup and cotton. Here, he refashioned Stieglitz’s celebrated self-portrait using wet ink and mimicking the dot matrix of a halftone reproduction. He then photographed his drawing and greatly enlarged it so that the dot matrix itself becomes as important as the picture it replicates.

Identity

Historic and contemporary works by August Sander, Diane Arbus, Lorna Simpson, and Hank Willis Thomas, among others, make up the final section, which explores the role of photography in the construction of identity.”

Wall text

Witkacy (Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz) (Polish, 1885-1939)

Self-Portrait (Collapse by the Lamp/Kolaps przy lampie)

c. 1913

Gelatin silver print

12.86 x 17.78cm (5 1/16 x 7 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Foto Fund and Robert Menschel and the Vital Projects Fund

A writer, painter, and philosopher, Witkiewicz began to photograph while he was a teenager. From 1911 to 1914, while undergoing psychoanalysis and involved in two tumultuous relationships (one ending when his pregnant fiancée killed herself in 1914), he made a series of startling self-portraits. Close-up, confrontational, and searching, they are pictures in which the artist seems to seek understanding of himself by scrutinising his visage.

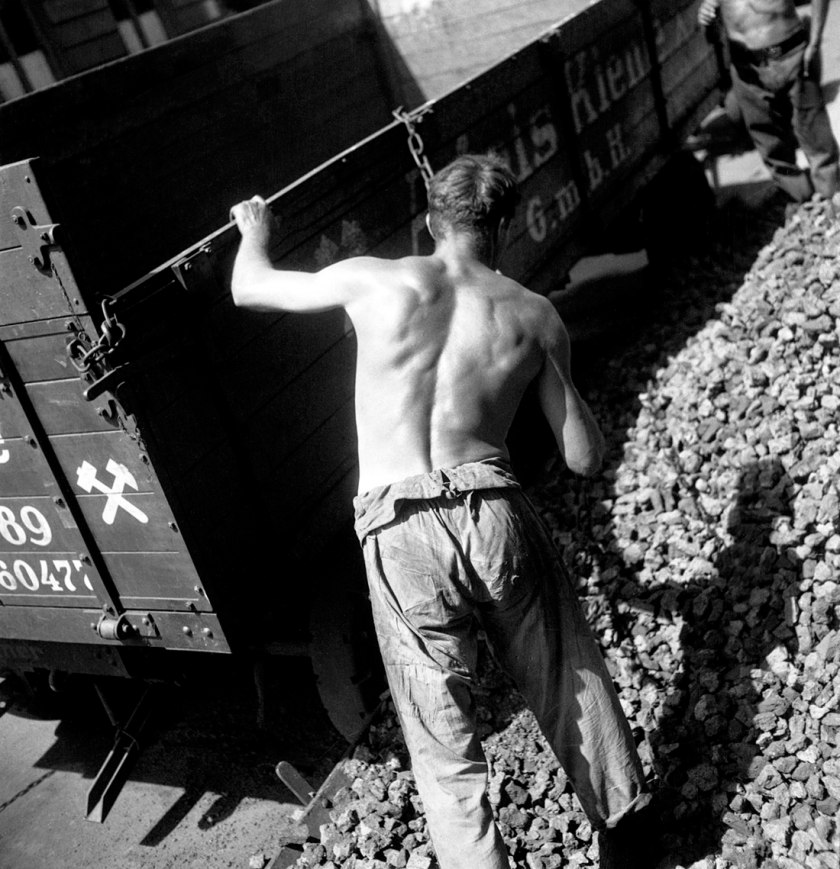

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

The Bricklayer

1929, printed c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

Sheet (trimmed to image): 50.4 x 37.5cm (19 13/16 x 14 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Gerhard and Christine Sander, in honour of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art

In 1911, Sander began a massive project to document “people of the twentieth century.” Identifying them by their professions, not their names, he aimed to create a typological record of citizens of the Weimar Republic. He photographed people from all walks of life – from bakers, bankers, and businessmen to soldiers, students, and tradesmen, as well as gypsies, the unemployed, and the homeless. The Nazis banned his project in the 1930s because his pictures did not conform to the ideal Aryan type. Although he stopped working after World War II, he made this rare enlargement of a bricklayer for an exhibition of his photographs in the early 1950s.

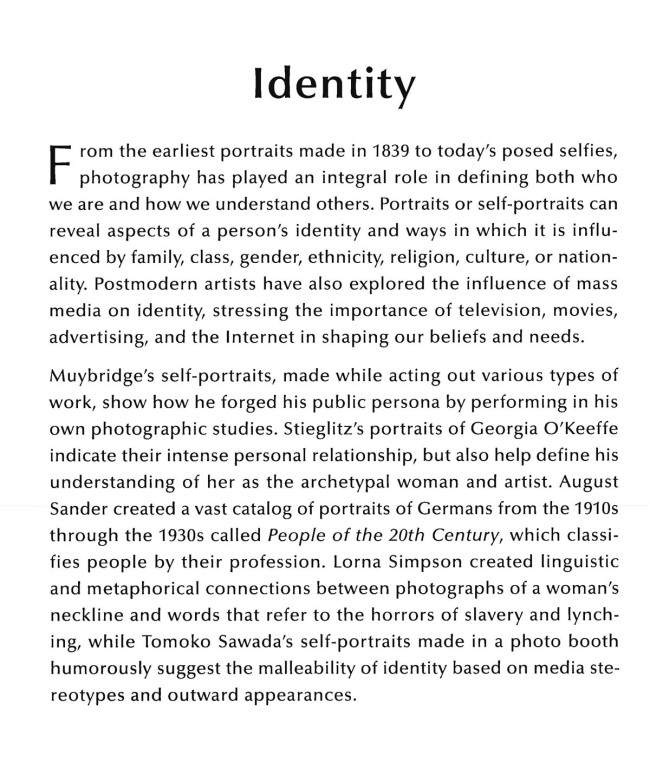

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Photographer’s Display Window, Birmingham, Alabama

1936

Gelatin silver print

Image: 24.1 x 19.3cm (9 1/2 x 7 5/8 in.)

Sheet: 25.2 x 20.3cm (9 15/16 x 8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harry H. Lunn, Jr. in honor of Jacob Kainen and in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National Gallery of Art

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971)

Triplets in their Bedroom, N.J.,

1963

Gelatin silver print

Image: 37.7 x 37.8cm (14 13/16 x 14 7/8 in.)

Sheet: 50.4 x 40.4cm (19 13/16 x 15 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, R. K. Mellon Family Foundation

Celebrated for her portraits of people traditionally on the margins of society – dwarfs and giants – as well as those on the inside – society matrons and crying babies – Arbus was fascinated with the relationship between appearance and identity. Many of her subjects, such as these triplets, face the camera, tacitly aware of their collaboration in her art. Rendering the familiar strange and the strange familiar, her carefully composed pictures compel us to look at the world in new ways. “We’ve all got an identity,” she said. “You can’t avoid it. It’s what’s left when you take away everything else.”

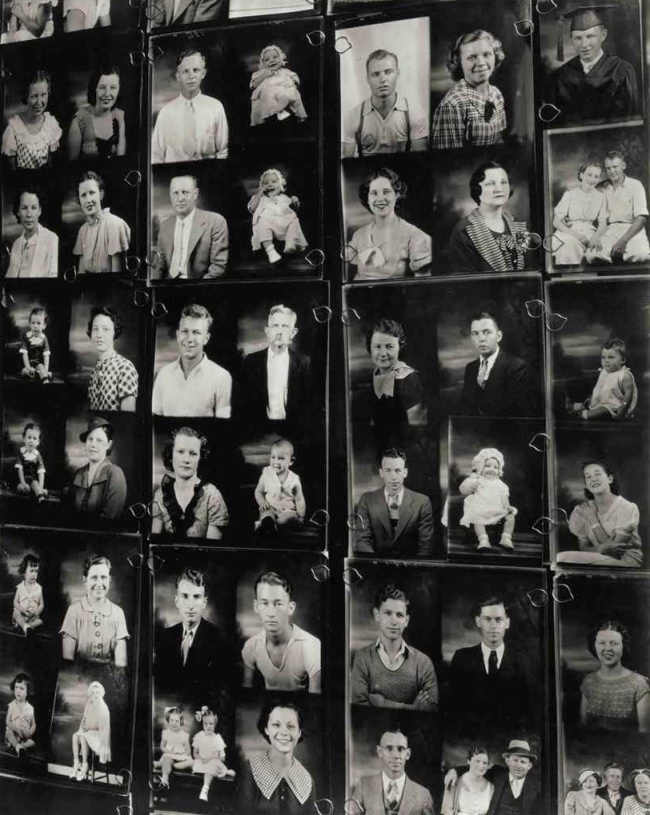

Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960)

Untitled (Two Necklines)

1989

Two gelatin silver prints with 11 plastic plaques

Overall: 101.6 x 254 cm (40 x 100 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of the Collectors Committee

From the mid-1980s to the present, Simpson has created provocative works that question stereotypes of gender, identity, history, and culture, often by combining photographs and words. Two Necklines shows two circular and identical photographs of an African American woman’s mouth, chin, neck, and collarbone, as well as the bodice of her simple shift. Set in between are black plaques, each inscribed with a single word: “ring, surround, lasso, noose, eye, areola, halo, cuffs, collar, loop.” The words connote things that bind and conjure a sense of menace, yet when placed between the two calm, elegant photographs, their meaning is at first uncertain. But when we read the red plaque inscribed “feel the ground sliding from under you” and note the location of the word “noose” adjacent to the two necklines, we realise that Simpson is quietly but chillingly referring to the act of lynching.

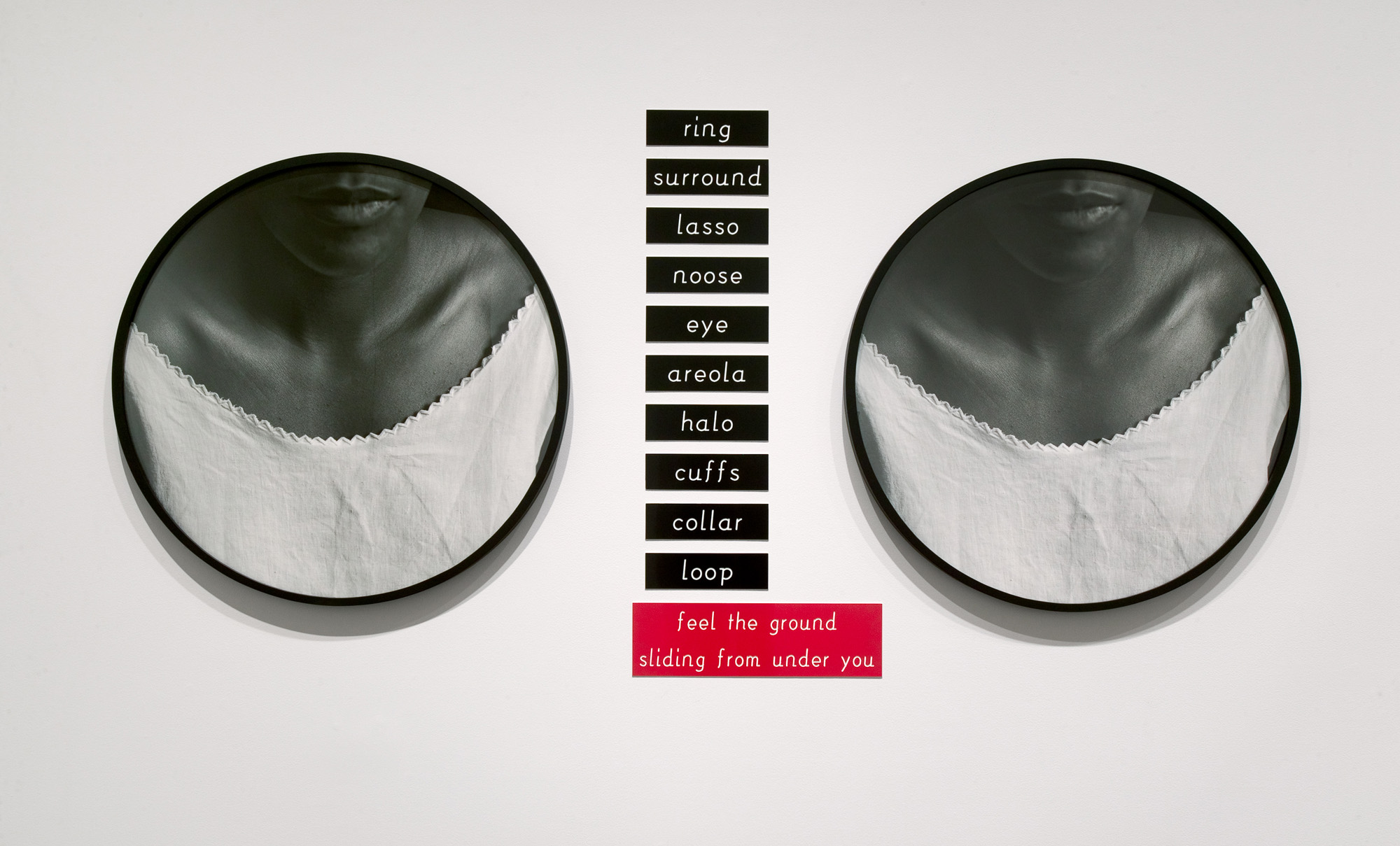

Hank Willis Thomas (American, b. 1976)

And One

2011

Digital chromogenic print

Framed: 248.29 × 125.73 × 6.35cm (97 3/4 × 49 1/2 × 2 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York)

And One is from Thomas’s Strange Fruit series, which explores the concepts of spectacle and display as they relate to modern African American identity. Popularised by singer Billie Holiday, the series title Strange Fruit comes from a poem by Abel Meeropol, who wrote the infamous words “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze; Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees” after seeing a photograph of a lynching in 1936. In And One, a contemporary African American artist reflects on how black bodies have been represented in two different contexts: lynching and professional sports. Thomas ponders the connections between these disparate forms through his dramatic photograph of two basketball players frozen in midair, one dunking a ball through a hanging noose.

National Gallery of Art

National Mall between 3rd and 7th Streets

Constitution Avenue NW, Washington

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00am – 5.00pm

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled Untitled [boy with a violoncello, Balaton, Hungary]' 1931](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eva_besnyo_gypsy_boy-web.jpg?w=655&h=644)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Shadow play]' Hungary 1931](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eva_besnyo_shadow_play-web.jpg?w=840&h=842)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [dockers on the Spree]' Berlin, 1931](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eva_besnyo_docks-web.jpg?w=840&h=1000)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Vertigo #3]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/photo_by_eva_besnyo_vertigo3-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Summer house in Groet, North Holland. Architects Merkelbach & Karsten]' 1934](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eb18-web.jpg?w=840&h=601)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Lieshout, The Netherlands]' 1954](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eb15-web.jpg?w=826&h=1024)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [The shadow of John Fernhout, Westkapelle, Zeeland, Netherlands]' 1933](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eb13-web.jpg?w=840&h=838)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [John Fernout with Rolleiflex at the Baltic seaside]' 1932](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eb02-web.jpg?w=840&h=939)

![Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932 Eva Besnyö. 'Untitled [Magda, Balaton, Hungary]' 1932](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/09/eb04-web.jpg?w=766&h=1024)

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

![Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–3 Sue Ford (1943-2009) 'Untitled [Bliss at Yellow House, King's Cross, Sydney]' c. 1972–3](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/06/008.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.