October 2013

Upsetting the court of public opinion…

A very interesting article, Covering their arts by John Elder (Sydney Morning Herald, October 13, 2013), examined the controversy over Bill Henson’s images of children sparked an age of censorship that is still spooking artists and galleries in Australia. At the end of the article Chris McAuliffe, ex-director of the Ian Potter Museum of Art, states that “There’s an assumption that the avant-garde tradition is a natural law as opposed to a constructed space.”

Almost everything (from the landscape to identity) is a constructed space, but that does not mean that the avant-garde cannot be deliberately transgressive, subversive, and break taboos. Artists should make art without fear nor favour, without looking over the shoulder worrying about the court of public opinion. McAuliffe’s statement may be logical but it certainly isn’t pro artist’s standing up to critique things that they see wrong in the world or expose different points of view that challenge traditional hegemonies.

While artists may not stand outside the law, if they believe in something strongly enough to challenge the status quo they must have the courage of their convictions… and just go for it.

The essay below, written in October 2010 and revised in September 2012 and published here for the first time, examines similar topics, investigating the use of photography as subversive image of reality. Download the full paper (2Mb pdf)

Transgressive Topographies, Subversive Photographies, Cultural Policies

Dr Marcus Bunyan

September 2012

Abstract

This research paper investigates the use of photography as subversive image of reality. The paper seeks to understand how photography has been used to destabilise notions of identity, body and place in order to upset normative mores and sensibilities. The paper asks what rules are in place to govern these transgressive potentialities in local, national and international arts policy and argues that prohibitions on the display of such transgressive acts are difficult to enforce.

Keywords

Topography, photography, mapping, transgression, identity, space, time, body, place, arts policy, culture, obscenity, blasphemy, defamation, nudity, shock art, transgressive art, law, censorship, free speech, morality, subversion, freedom of speech, Social Conservatism, taboo, Other.

“Through their power, institutions (such as the Arts Council of Australia) produce rituals of truth and we as artists can and must challenge this perceived truth through the use of transgressive texuality. This texuality “can become a mode of agential resistance capable of fragmenting and releasing the subject, and thereby producing a zone of invisibility where knowledge/power is no longer able ‘find its target’.”44

Only through resistance can transgressive art, including subversive photography, challenge the status quo of a conservative worldview.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan September 2012

Thomas J. Nevin (Australian, 1842-1923)

Hugh Cowan, aged 62 yrs

1878

Detail of criminal register, Sheriff’s Office, Hobart Gaol to 1890, page 120, GD6719 TAHO

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Thomas J. Nevin produced large numbers of stereographs and cartes within his commercial practice, and prisoner ID photographs on government contract and in civil service. He was one of the first photographers to work with the police in Australia, along with Charles Nettleton (Victoria) and Frazer Crawford (South Australia). His Tasmanian prisoner vignettes (“mugshots”) are the earliest to survive in public collections.

Found guilty of wilful murder in early April 1878, Hugh Cowan’s sentence of death by hanging was commuted to life imprisonment. The negative was taken and printed in the oblong format in late April 1878, and was pasted to the prisoner’s revised criminal sheet after commutation, held at the Hobart Gaol, per notes appearing on the sheet. More information can be found on the “Two mugshots of convict Hugh COHEN or Cowen / Cowan 1878” page on the Thomas J. Nevin: Tasmanian Photographer blog, Wednesday, September 11, 2013.

Andre-Adolphe Eugene Disderi (French, 1819-1889)

Communards in Their Coffins

c. 1871

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

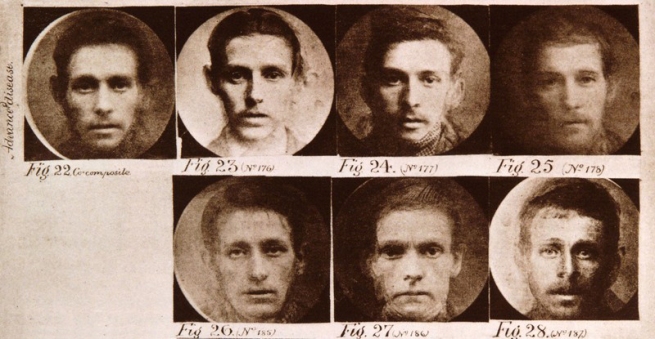

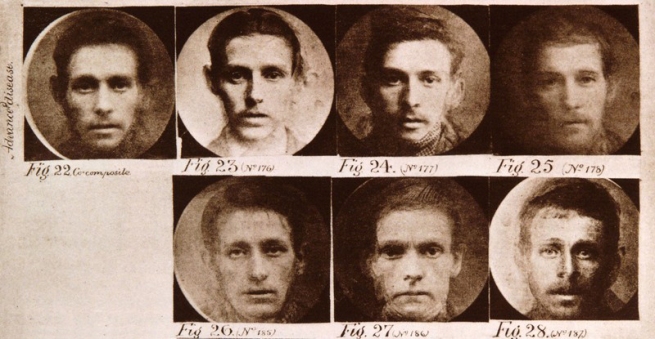

Francis Galton (British, 1822-1911)

Composite portraits of Advanced Disease

1883

From Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development 1883

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Anonymous photographer

Crowds lined up to visit Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art), Schulausstellungsgebaude, Hamburg

November – December 1938

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Anonymous photographer

Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition

1936

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Introduction

“The artist is also the mainstay of a whole social milieu – called a “scene” – which allows him to exist and which he keeps alive. A very special ecosystem: agents, press attachés, art directors, marketing agents, critics, collectors, patrons, art gallery managers, cultural mediators, consumers… birds of prey sponge off artists in the joyous horror of showbiz. A scene with its codes, norms, outcasts, favourites, ministry, exploiters and exploited, profiteers and admirers. A scene which has the monopoly on good taste, exerting aesthetic terrorism upon all that which is not profitable, or upon all that which doesn’t come from a very specific mentality within which subversion must only be superficial, of course at the risk of subverting. A milieu which is named Culture. Each regime has its official art just as each regime has its Entartete Kuntz (‘Degenerate art’).”1

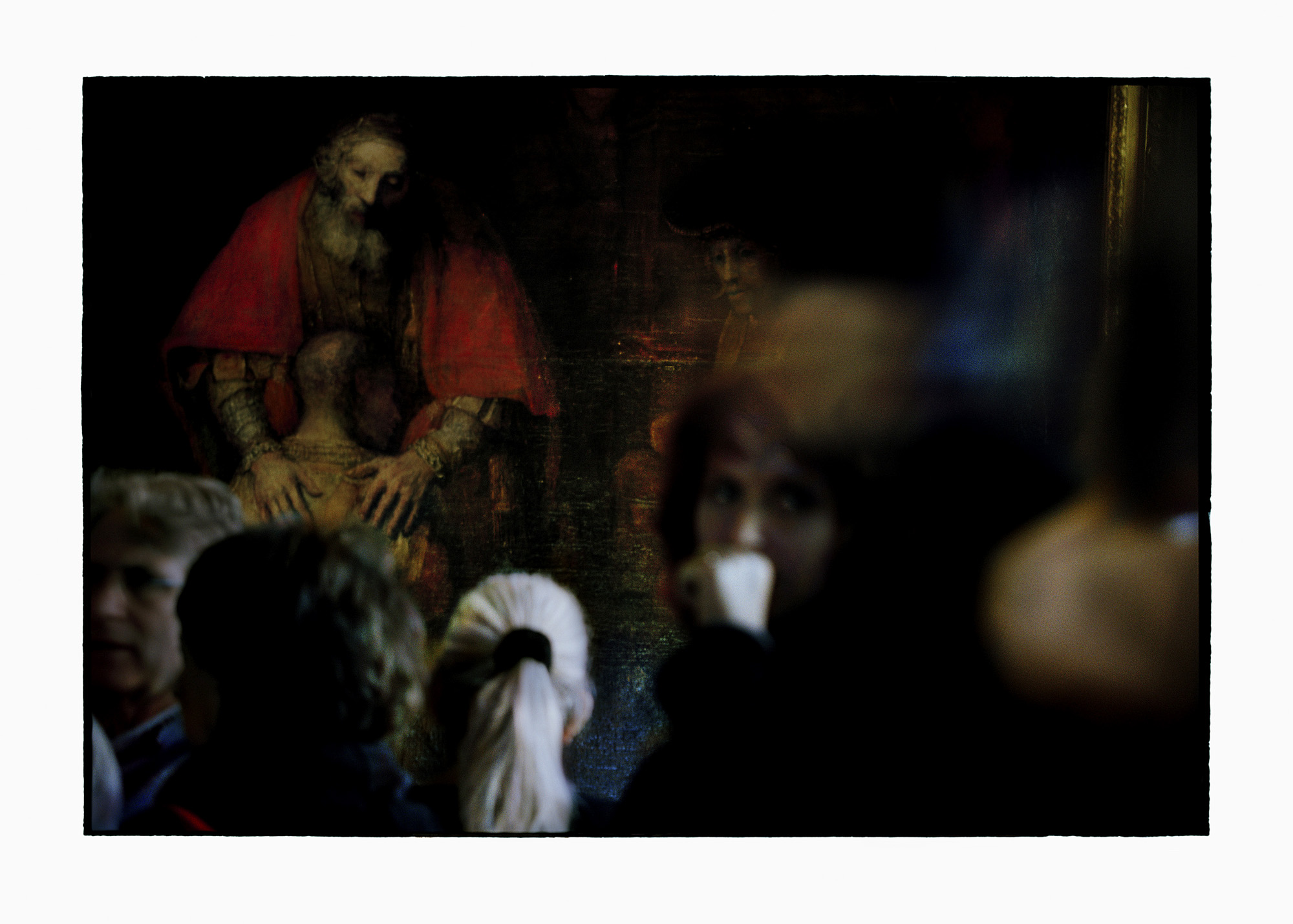

Throughout its history photography has been used to record and document the world that surrounds us, producing an image of a verifiable truth that visually maps identity, body and place. This is the topography of the essay title: literally, the photographic mapping of the world, whether it be the mapping of the Earth, the mapping of the body or the visualisation of identities as distinct from one person to another, one nation or ethnic group to another. At the very beginning of the history of photography the first photographs astounded viewers by showing the world that surrounded them. This ability of photography to map a visual truth was used in the mid-Victorian period by the law to document the faces of criminals (such as in the “mugshot” by Tasmanian photographer Thomas J. Nevin, above): “Photography became a modern tool of criminal investigation in the late nineteenth century, allowing police to identify repeat offenders,”2 and through the pseudo-science of physiognomy to identify born criminals solely from photographs of their faces (see the “composite” photograph Francis Galton, above), this topography used by the Nazis in their particular form of eugenics.3 In the Victorian era photography was also used by science to document medical conditions4 and by governments to document civil unrest (such as the death of the Communards in Paris, above).5

Paradoxically, photography always lies for the photograph only depicts one version of reality, one version of a truth depending on what the camera is pointed at, what it excludes, who is pointing the camera and for what reasons, the context of the event or person being photographed (which is fluid from moment to moment) and the place and reason for displaying the photograph. In other words all photographs are, by the very nature, transgressive because they have only one visual perspective, only one line of sight – they exclude as much as they document and this exclusion can be seen as a volition (a choice of the photographer) and a violation of a visual ordering of the world (in the sense of the taxonomy of the subject, an upsetting of the normal order or hierarchy of the subject).6 Of course this line of sight may be interpreted in many ways and photography problematises the notion of a definitive reading of the image due to different contexts and the “possibilities of dislocation in time and space.”7 As Brian Wallis has observed, “The notion of an autonomous image is a fiction”8 as the photograph can be displaced from its original context and assimilated into other contexts where they can be exploited to various ends. In a sense this is also a form of autonomy because a photograph can be assimilated into an infinite number of contexts. “This de and re-contextualisation is itself transgressive of any “integrity” the photograph itself may have as a contextualised artefact.”9 As John Schwartz has insightfully noted, “[Photographs] carry important social consequences and that the facts they transmit in visual form must be understood in social space and real time,”10 “facts” that are constructions of reality that are interpreted differently by each viewer in each context of viewing.

Early examples of the break down of the indexical nature of photography (the link between referent and photograph as a form of ‘truth’) – the subversion of the order of photography – are the Victorian photographs of children at the Dr Barnados’ homes (in this case to support the authority of an institution, not to undermine it as in the case of subverting cultural hegemony – see next section). “In the 1870s Dr. Barnardo had photographs taken that showed rough, dirty, and dishevelled children arriving at his homes, and then paired them with photographs of the same children bright as a new pin, happy and working in the homes afterwards. These photographs were used to sell the story of children saved from poverty and oppression and happy in the homes; they appeared on cards which were sold to raise money to support the work of these homes. Dr. Barnardo was taken to court when one such pair of photographs was found to be a fabrication, an ‘artistic fiction’.”11

Here the photographs offered one interpretation of the image (that of the happy child) that supports the authority of Dr Barnardo, the power of his institution in the pantheon of cultural forces. The power of truth that is vested in these photographs is validated because people know the key to interpret the coded ‘sign’ language, the semiotic language through which photographs, and indeed all images, speak. But these photographs only portray one supposed form of ‘truth’ as viewed from one perspective, not the many subjective and objective truths viewed from many positions. Conversely, two examples can be cited of the use of photography to undermine dominant hegemonic cultural power – one while being officially accepted because of references to classical Greek antiquity, the other seemingly innocuous photographic documentary reportage of the genetic makeup of the German people being rejected as subversive by the Nazis because it did not represent their view of what the idealised Aryan race should look like.

Baron von Gloeden’s photographs of nude Sicilian ephebes (males between boy and man) in the late 19th and early 20th century were legitimised by the use of classically inspired props such as statues, columns, vases and togas. “The photographs were collected by some people for their chaste and idyllic nature but for others, such as homosexual men, there is a subtext of latent homo-eroticism present in the positioning and presentation of the youthful male body. The imagery of the penis and the male rump can be seen as totally innocent, but to homosexual men desire can be aroused by the depiction of such erogenous zones within these photographs.”12 Such photographs were distributed through what was known as the “postcard trade” that reached its zenith between the years 1900-1925.13

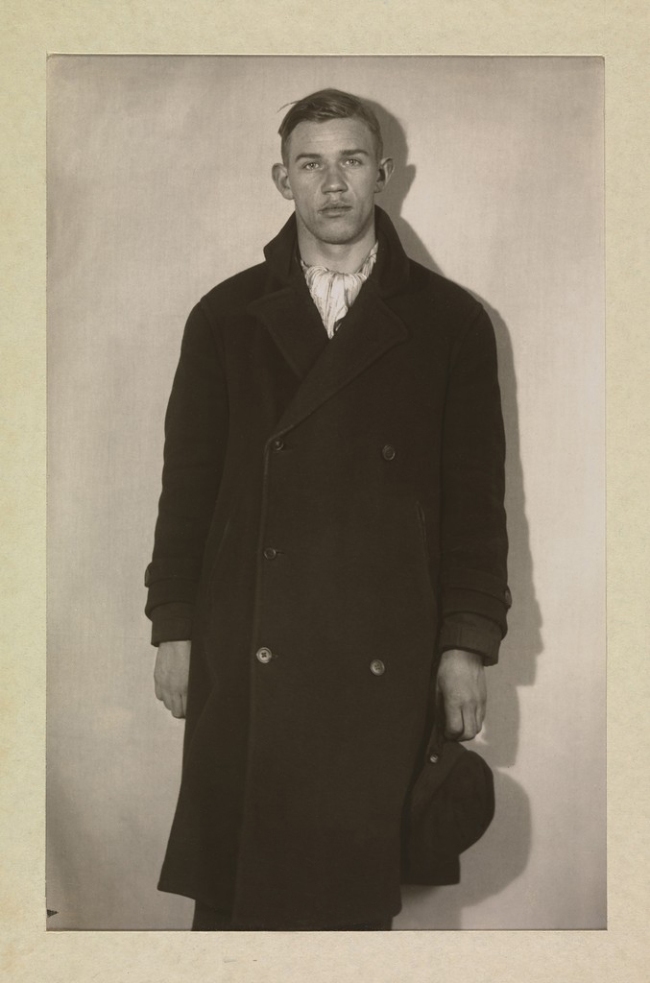

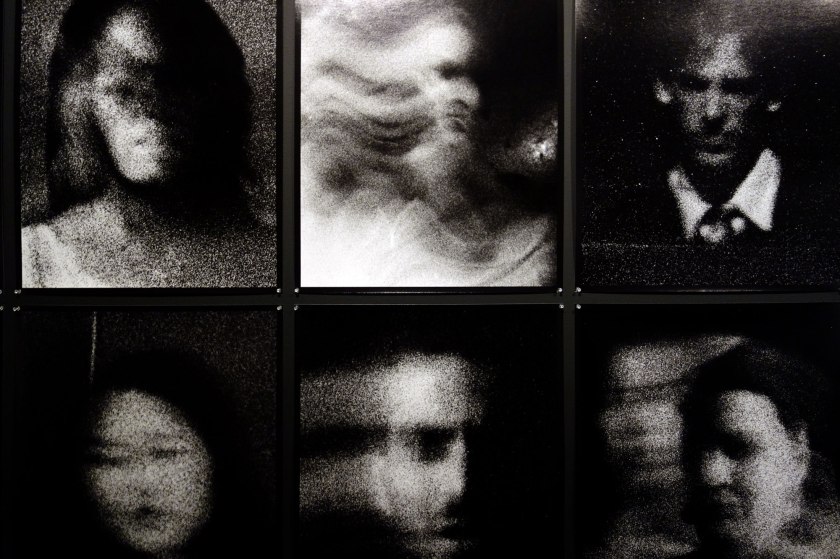

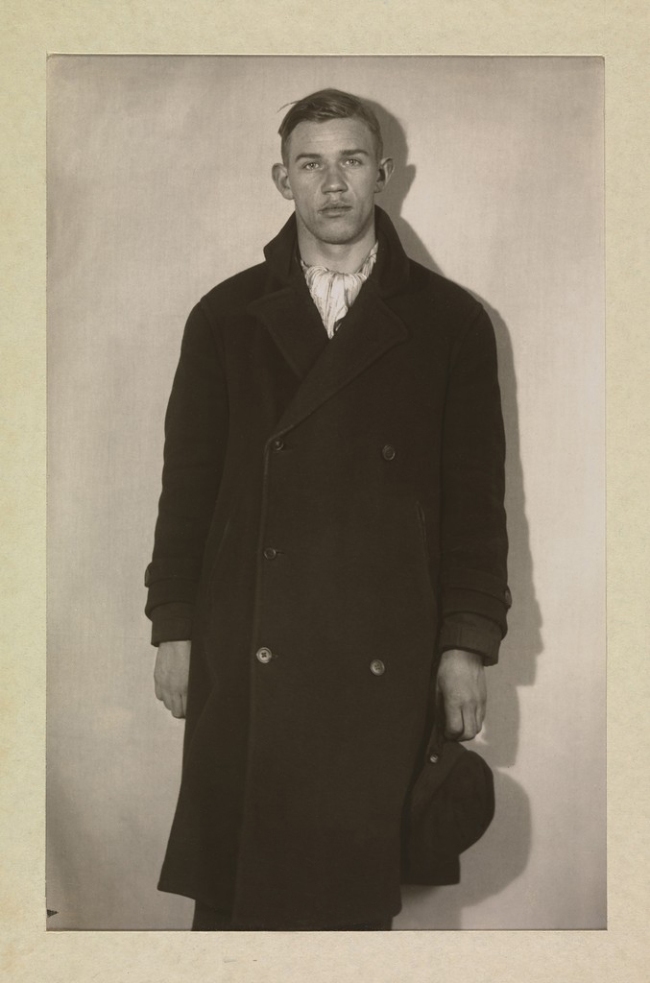

August Sander’s 1929 photo-book Face of Our Time (part of a larger unpublished project to be called Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the Twentieth Century) “included sixty portraits representing a broad cross-section of German classes, generations, and professions. Shot in an un-retouched documentary style and arranged by social groups, the portraits reflected Sander’s desire to categorise society according to social and professional types in an era when class, gender, and social boundaries had become increasingly indistinguishable.”14 Liberal critics such as Walter Benjamin and photographer Walker Evans hailed Sander as a master photographer and a documenter of human types but with the rise of National Socialism in the mid-1930s “the Reichskulturkammer ordered the destruction of Face of Our Time‘s printing plates and all remaining published copies. Various explanations for this action have been offered. Most cast Sander in the flattering role of an outspoken resistor to the regime … While it is certainly plausible that the book’s destruction was a kind of punishment for the photographer’s “subversive” activities, it is more likely that the members of the new regime disagreed with Sander’s inclusion of Jews, communists, and the unemployed.”15 After this time his work and personal life were greatly curtailed under the Nazi regime. In an excellent article by Rose-Carol Washton Long recently, the author argues that Sander’s ‘The Persecuted’ and ‘Political Prisoners’ portfolios from People of the Twentieth Century counter the characterisation that his work was politically neutral.16

Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931)

Two Male Youths Holding Palm Fronds

c. 1885-1905

Albumen silver

233mm (9.17 in) x 175mm (6.89 in)

The J. Paul Getty Museum

This work is in the public domain

Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931)

Bacchanal

c. 1890s

Catalogue number: 135 (or 74)

Gaetano Saglimbeni, Album Taormina, Flaccovio 2001, p. 18

This work is in the public domain

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand

1920

Silver gelatin photograph mounted on paper

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Victim of Persecution

1938, printed 1990

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Lent by Anthony d’Offay 2010

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2013

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Victim of Persecution

c. 1938

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Lent by Anthony d’Offay 2010

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2013

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Political Prisoner [Erich Sander]' 1943, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Political Prisoner [Erich Sander]' 1943, printed 1990](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/august-sander-political-prisoner-erich-sander-1943-photograph-gelatin-silver-print-on-paper-b.jpg?w=650&h=851)

August Sander (German, 1876-1964)

Political Prisoner [Erich Sander]

1943, printed 1990

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Lent by Anthony d’Offay 2010

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur – August Sander Archiv, Cologne; DACS, London, 2013

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

The conditions of photography leave open spaces of interpretation and transgression, in-between spaces that allow artists to subvert the normative mapping of reality. While the term ‘transgressive art’ may have only been coined in the 1980s it is my belief that photography has, to some extent, always been transgressive because of the conditions of photography: its contexts and half-truths. Photography has always opened up to artists the possibility of offering the viewer images open to interpretation, where the constructed personal narratives of the viewer are mediated through mappings of identity, body and place that challenge how the viewer sees the world and the belief systems that sustain that view. Here photography can subvert, can undertake a more surreptitious eroding of the basis of belief in the status quo. Photography can address the idea of subjective and objective truths, were there is never a single truth but many truths, many different perspectives and lines of sight, never one definitive ‘correct’ interpretation. As David Smail rightly notes of subjective and objective truths,

“Where objective knowing is passive, subjective knowing is active – rather than giving allegiance to a set of methodological rules which are designed to deliver up truth through some kind of automatic process [in this case the image], the subjective knower takes a personal risk in entering into the meaning of the phenomena to be known… Those who have some time for the validity of subjective experience but intellectual qualms about any kind of ‘truth’ which is not ‘objective’, are apt to solve their problem by appealing to some kind of relativity. For example, it might be felt that we all have our own versions of the truth about which we must tolerantly agree to differ. While in some ways this kind of approach represents an advance on the brute domination of ‘objective truth’, it in fact undercuts and betrays the reality of the world given to our subjectivity. Subjective truth has to be actively struggled for: we need the courage to differ until we can agree. Though the truth is not just a matter of personal perspective, neither is it fixed and certain, objectively ‘out there’ and independent of human knowing. ‘The truth’ changes according to, among other things, developments and alterations in our values and understandings… the ‘non-finality’ of truth is not to be confused with a simple relativity of ‘truths’.”17

The truth changes due to alterations of our values and understandings; “truth” is perhaps even constructed by our values and understandings. What an important statement this is with regard to the potential subversive nature of photography.

The Subversion of Cultural Hegemony: Cultural Policy, Photography and Problems of Interpretation

Some of the most common themes that transgressive art may address are the power of institutions (such as governments), the portrayal of sex as art (which may address the notion of when is pornography art and not obscenity),18 issues of faith, religion and belief, of nationalism, war, of death, of gender, of drug use, of culturally suppressed minorities, ‘Others’ that have been socially excluded (see definition of ‘Other’ above). Conversely, art that lies (another form of transgression) can be used to uphold institutions that wish to reinforce the perception of their social position through the verification of truth in reality. An example of this are photographs which purport to tell the ‘truth’ about an event but are in fact constructions of reality, emphasising the link between the referent and the photograph that is the basis of photography while subverting it (through faking it, through manipulation of the image) to the benefit of the ruling social class.19

Transgressive art that subverts cultural hegemony (the philosophical and sociological concept whereby a culturally-diverse society can be ruled or dominated by one of its social classes)20 by upsetting predominant cultural forces such as patriarchy,21 individualism (which promotes individual moral choice),22 family values,23 and resisting social norms24 (institutions, practices, beliefs) that impose universal (if sometimes hidden) public moral25 and ethical26 values, has, seemingly, free rein in terms of local and centralised art policy in Australia because the responsibility for the outcomes of transgression rests in the hands of the artists and the galleries that display this art. This is in itself a cultural policy statement, a statement by abrogation rather than action. The statement below on the Australia Council for the Arts website, the Australian Government’s arts funding and advisory body is, believe it or not, the only statement giving advice to artists about defamation and obscenity laws in Australia. The website then refers artists to the Arts Law Centre of Australia Online for more information, of which there is very little, about issues such as defamation, obscenity, blasphemy, sedition and the morals and ethics of producing and exhibiting art that challenges dominant cultural stereotypes, images and beliefs.

“Defamation and obscenity laws in Australia can be very tough and vary substantially from state to state. If you have any doubts discuss them with others and try and assess the level of risk involved. Unfortunately, these are highly subjective areas and obscenity laws are driven by current community standards that are constantly shifting. Defaming someone in Australia can be a very serious offence. Don’t think that just because your project is small it won’t be noticed. Sometimes controversy can bring a project to public attention. (Not that that’s necessarily a bad thing!) And just because your project is small, this does not protect you from potential prosecution in the courts. Although not advised, if you do take risks in these areas make sure your project team are all equally aware of them and all in favour of doing so.”27

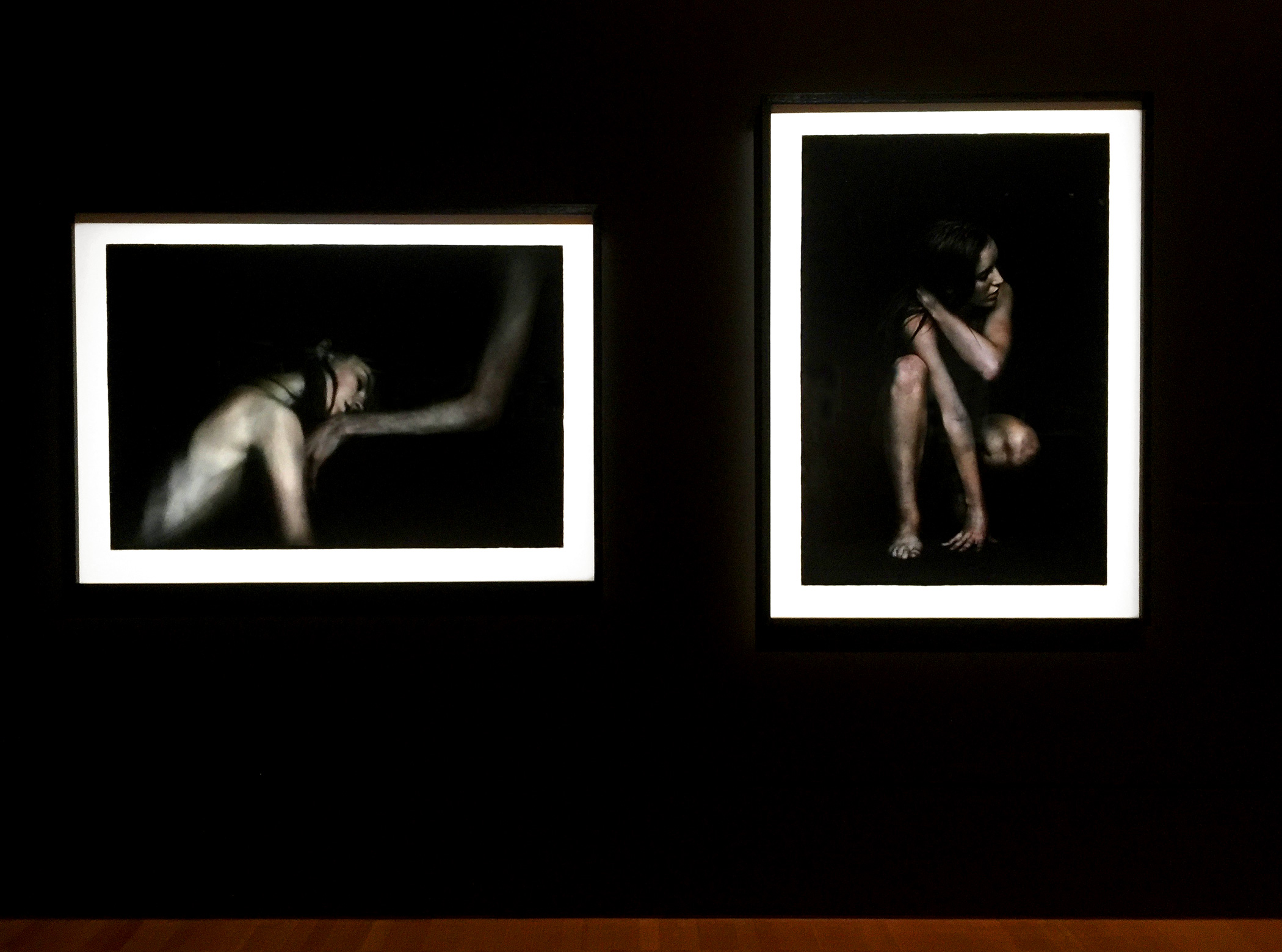

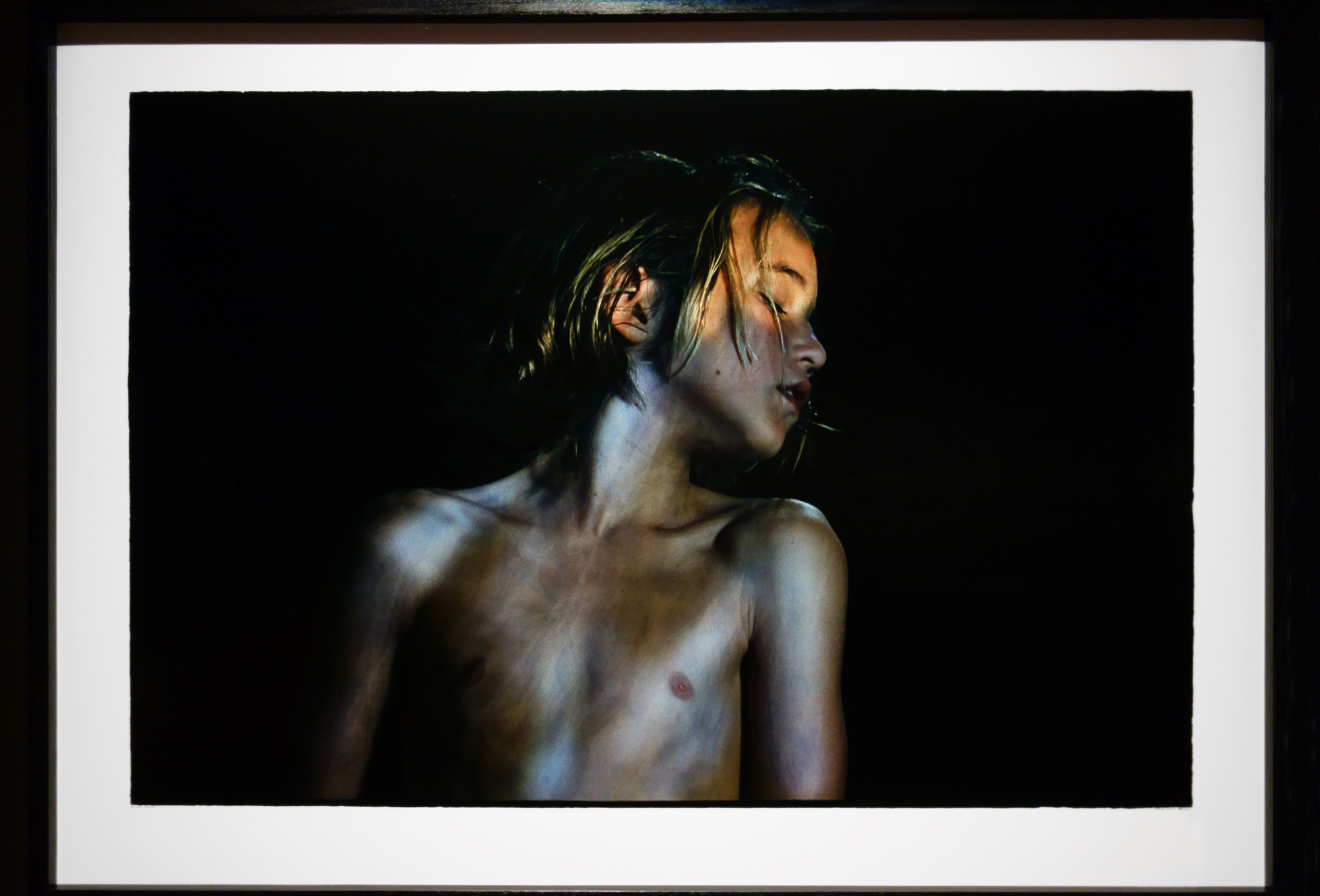

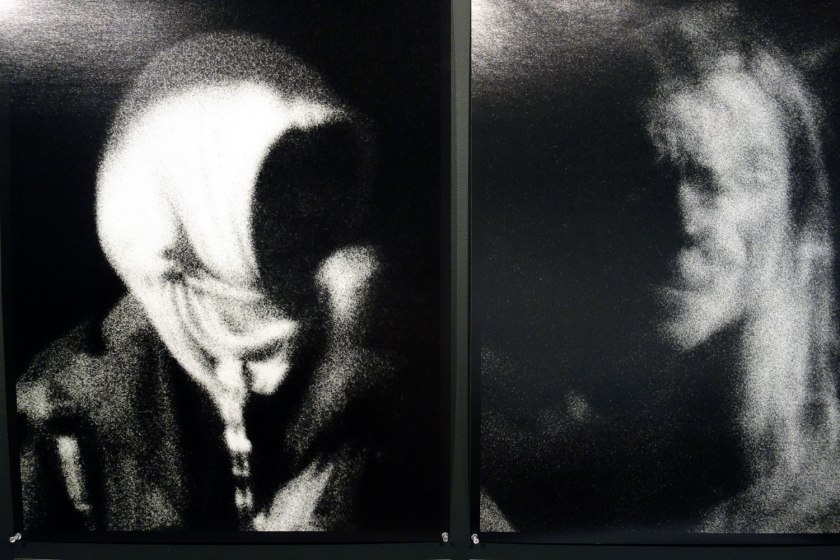

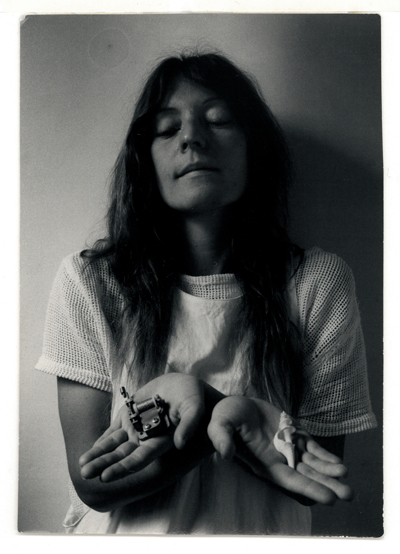

While challenging the dominant paradigm (through the use of shock art28 for example) might raise the profile of the artist and gallery concerned, the risks can be high. Even when artistic work is seemingly innocuous (for example the media and family values furore over the work of Australian artist Bill Henson29 that eventually led the Australia Council for the Arts to issue protocols for working with children in art,)30 – forces opposed to the relaxing of social and political morals and ethics (such as governments, religious authorities and family groups) can ramp up public sentiment against provocative and, what is in their opinion, licentious art (art that lacks moral discipline) because they believe that it is art that is not “in the public interest” or is considered offensive to a “common sense of decency.” The ideology of social conservatism31 is ever present in our society but this ideology is never fixed and is forever changing; the same can be said of what is deemed to be transgressive as the above quotation by the Australia Council notes. For example George Platt Lynes photographs of homosexual men associating together taken in the 1940s were never shown in his lifetime in a gallery for fear of the moral backlash and the damage this would cause his career as a fashion photographer in America. Some of these photographs now reside in The Kinsey Institute (see my research into these images on my PhD website).32 Today these photographs would not even raise a whisper of condemnation such is their chaste imagery.33

.

During my research I have been unable to find a definition of the theoretical role of arts policy in dealing with transgression in art. Perhaps this is acceptable for surely the purpose of an arts policy is primarily to facilitate artistic activity of any variety, whether is be transgressive or not, as long as that artistic activity challenges people to look at the world in a new light. The various effects, or impacts, of the arts and artistic activities can include, “social impacts, social effects, value, benefits, participation, social cohesion, social capital, social exclusion or inclusion, community development, quality of life, and well-being. There are two main discernable approaches in this research. Some tackle the issues ‘top-down’, by exploring the social impacts of the arts, where ‘social’ means non-economic impacts, or impacts that relate to social policies. Others, and in the USA in particular, approach effects from the ‘bottom up’, by exploring individual motivations for and experiences of arts participation, and evaluating the impacts of particular arts programs.”34

Personally I believe that the purpose of a cultural arts policy is to promote open artistic inquiry into topics that challenge the notion of self and the formation of national and personal identity. Whether this inquiry fits in with the socio-political imperative of nation building or the economic rationalism of arts as a cultural industry and how censorship and free speech fit in with this economic modelling is an interesting topic for research. Berys Gaut questions what role, if any, “ought the state to play in the regulation and promotion of art? The spectre of censorship has cast a long shadow over the debate … And wherever charges of film’s and popular music’s ethically corrupting tendencies are heard, calls for censorship or self-restraint are generally not far behind. Such a position is in a way the converse side of the humanistic tradition’s espousal of state subsidies for art, because of art’s purported powers to enhance the enjoyment of life and promote the spread of civilisation.”35

In terms of art and ethics the immoralist approach, “has as its most enduring motivation the idea of art as transgression. It acknowledges that ethical merits or demerits of works do condition their aesthetic value.”36 Often the definition of the ethical merits or demerits of an artwork come down to the contextualisation of the work of art: who is looking and from what perspective. “When you look at the history of censorship, it becomes clear that what is regarded as obscene in one era is often regarded as culturally valuable in another. Whether something is pornography or art, in other words, depends a lot on who’s looking, and the cultural and historical viewing point from which they’re looking.”37

The ideal political system of arts policy is an arms length policy free from political interference; the reality may be something entirely different for bureaucracy may seek to control an artist’s freedom of expression through censorship and control of economic stimulus while preserving bureaucracy itself as a self-referential self-reproducing system:

“The balance of power between the different systems of rationalities in a given society in a given historical is decisive for which forms of rationality will be dominating. For example, the rationality of the economic market forces, the political media and bureaucracies, the intrinsic values of the aesthetic rationality and of the anthropological conceptualisation of culture are all different rationalities in play in the cultural field … in a broader sense cultural policy, however, is also about the clash of ideas, institutional struggles and power relations in the production, dissemination and reception of arts and symbolic meaning in society.

In democratic societies governed by law, cultural policy according to this argumentation is the outcome of the debate about which values (forms of recognition) are considered important for the individuals and collectives a given society. Is it the instrumental rationality of the economic and political medias or the communicative rationality of art and culture, which shall be dominating in society?”38

This is an ongoing debate. In the United States of America grants from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to artists including Robert Mapplethorpe and Andres Serrano led to the culture wars of the 1990s. Their work was described as indecent and in 1998 the Supreme Court determined that the statute mandating the NEA to consider “general standards of decency and respect for the diverse beliefs and values of the American public” in awarding grants was constitutional.39 In Australia there was the furore over the presentation of the photograph “Piss Christ” by Andres Serrano at the National Gallery of Victoria in 1997 that led to it’s attack by a vandal and the closing of the exhibition of which it was a part, as well as other incidents of cultural vandalism.40 In consideration of these culture wars, it would be an interesting research project to analyse the grants received by artists from the Australia Council for the Arts and Arts Victoria, for example, to see how many artists receive grants for transgressive art projects. My belief would be that, while the ideal is for the “arms length” principle of art funding, very few transgressive art projects that challenge the norm of cultural sensibilities and mores in Australia would achieve a level of funding. Australia is at heart a very conservative country and arts funding policies, while not specifically stating this, still support the status quo and their self-referential position within this system of power and control.

![George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955) 'Tex Smutley and Buddy Stanley [no title (two sleeping boys)]' 1941 George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955) 'Tex Smutley and Buddy Stanley [no title (two sleeping boys)]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/george-platt-lynes-united-states-of-america-1907-e28093-1955-tex-smutley-and-buddy-stanley-no-title-two-sleeping-boys-1941-gelatin-silver-photograph-printed-image-19-2-h-x-24-4-w-cm.jpg)

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Tex Smutley and Buddy Stanley [no title (two sleeping boys)]

1941

Gelatin silver photograph

19.2 x 24.4cm

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955)

Untitled

Date unknown (probably early 1950s)

Vintage gelatin silver print

9 x 7 1/2 in. (22.9 x 19.1cm)

Collection of Steven Kasher Gallery

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

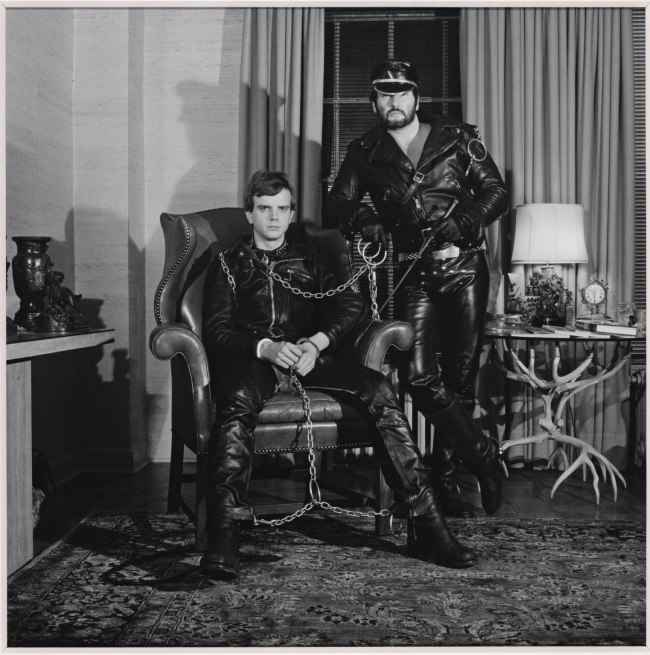

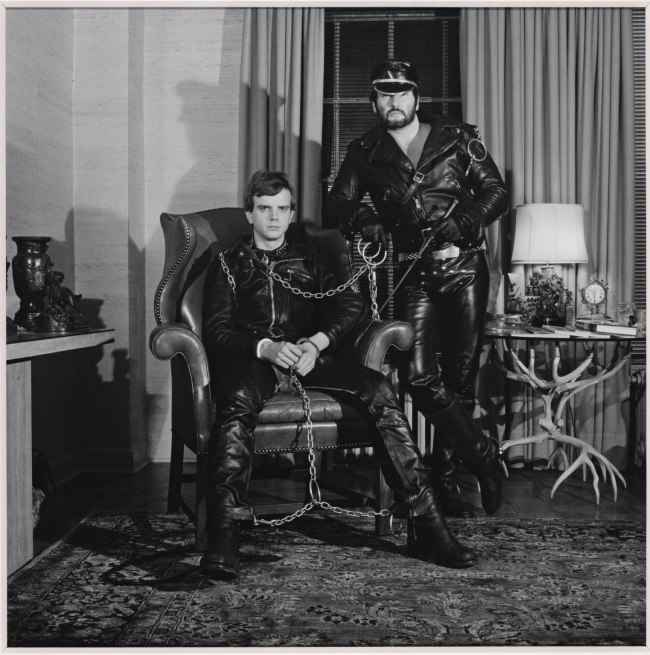

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Joe

1978

Silver gelatin photograph

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

Brian Ridley and Lyle Heeter

1979

Silver gelatin photograph

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Mapplethorpe’s photos of gay and leather subcultures were at the center of a controversy over NEA funding at the end of the ’80s. Sen. Jesse Helms proposed banning grants for any work treating “homoerotic” or “sado-masochistic” themes. When Helms showed the photos to his colleagues, he asked “all the pages and all the ladies to leave the floor.”

Bill Henson (Australian, b. 1955)

Untitled #8

2007/08

Type C photograph

127 × 180cm

Edition of 5 + 2 A/Ps

© Bill Henson/Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Andres Serrano (American, b. 1950)

Immersion (Piss Christ)

1987

Cibachrome print

60 x 40 in.

© Andres Serrano

Used for literary criticism under fair use, fair dealing

Conclusion

“Policy in Australia aspires to achieve a high-level of consistency – if not to say universality – and so struggles with concepts as amorphous as mores, norms or sensibilities.”41 Hence there is no local or centralised public arts policy with regard to photography, or any art form, that transgresses and violates basic mores and sensibilities, usually associated with social conservatism. Implementing national guidelines for transgressive art would be impossible because of the number of artists producing work, the number of galleries showing that work, the number of exhibitions that take place every week throughout Australia (including artist and gallery online web presences) and the commensurate task of enforcing and policing such guidelines. These guidelines would also be impossible to establish due to a lack of agreement in the definition of what transgressive art is for the meaning of transgressive art, or any art for that matter, depends on who is looking, at what time and place, from what perspective and in what context. Photography opens up to artists the possibility of offering the viewer personal narratives and constructions of worlds that they have never seen before, transgressive text(ur)al mappings of identity, body and place that challenge how the viewer sees the world and the belief systems that sustain that view and that is at it should be. Art should challenge human beings to be more open, to see further up the road without the fear of a cultural arts policy or any institutional policy for that matter dictating what can or cannot be said.

Brain Long has suggested that arts policy is primarily to facilitate artistic activity and questions of public morality are best left to the legal system with its juries, judges, checks and balances42 but I believe that this position is only partially correct. I believe that it is not just the legal system but the hidden agendas of committees that decide grants and the hypocritical workings of the institutions that enforce a prejudiced world view that govern censorship and free speech in Australia. Freedom of expression in Australia is not just governed by the laws of defamation, obscenity and blasphemy that vary from state to state but by hidden disciplinary forces, systems of control that seek to create a reality of their own making.

“To reiterate the point, it should be clear that when Foucault examines power he is not just examining a negative force operating through a series of prohibitions… We must cease once and for all to describe the effects of power in negative terms – as exclusion, censorship, concealment, eradication. In fact, power produces. It produces reality. It produces domains of objects, institutions of language, rituals of truth.”43

Through their power, institutions (such as the Arts Council of Australia) produce rituals of truth and we as artists can and must challenge this perceived truth through the use of transgressive texuality. This texuality “can become a mode of agential resistance capable of fragmenting and releasing the subject, and thereby producing a zone of invisibility where knowledge/power is no longer able ‘find its target’.”44

Only through resistance can transgressive art, including subversive photography, challenge the status quo of a conservative worldview.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

September 2013

Word count: 3,933

Glossary of terms

Transgressive art refers to art forms that aim to transgress; ie. to outrage or violate basic mores and sensibilities. The term transgressive was first used by American filmmaker Nick Zedd and his Cinema of Transgression in 1985.45

Subversion refers to an attempt to overthrow the established order of a society, its structures of power, authority, exploitation, servitude, and hierarchy… The term has taken over from ‘sedition’ as the name for illicit rebellion, though the connotations of the two words are rather different, sedition suggesting overt attacks on institutions, subversion something much more surreptitious, such as eroding the basis of belief in the status quo or setting people against each other.46.

Blasphemy is irreverence toward holy personages, religious artefacts, customs, and beliefs.47 The Commonwealth of Australia does not recognise blasphemy as an offence although someone who is offended by someone else’s attitude toward religion or toward one religion can seek redress under legislation which prohibits hate speech.48.

Defamation – also called calumny, vilification, slander (for transitory statements), and libel (for written, broadcast, or otherwise published words) – is the communication of a statement that makes a claim, expressly stated or implied to be factual, that may give an individual, business, product, group, government, or nation a negative image. In common law jurisdictions, slander refers to a malicious, false and defamatory spoken statement or report, while libel refers to any other form of communication such as written words or images… Defamation laws may come into tension with freedom of speech, leading to censorship.49

An obscenity is any statement or act which strongly offends the prevalent morality of the time, is a profanity, or is otherwise taboo, indecent, abhorrent, or disgusting, or is especially inauspicious. The term is also applied to an object that incorporates such a statement or displays such an act. In a legal context, the term obscenity is most often used to describe expressions (words, images, actions) of an explicitly sexual nature.50

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship or limitation, or both. The synonymous term freedom of expression is sometimes used to indicate not only freedom of verbal speech but any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used. In practice, the right to freedom of speech is not absolute in any country and the right is commonly subject to limitations, such as on “hate speech”… Freedom of speech is understood as a multi-faceted right that includes not only the right to express, or disseminate, information and ideas, but three further distinct aspects:

~ the right to seek information and ideas

~ the right to receive information and ideas

~ the right to impart information and ideas51

Censorship is the suppression of speech or other communication which may be considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or inconvenient to the general body of people as determined by a government, media outlet, or other controlling body.

~ Moral censorship is the removal of materials that are obscene or otherwise considered morally questionable52

A taboo is a strong social prohibition (or ban) relating to any area of human activity or social custom that is sacred and forbidden based on moral judgment and sometimes even religious beliefs. Breaking the taboo is usually considered objectionable or abhorrent by society… Some taboo activities or customs are prohibited under law and transgressions may lead to severe penalties… Although critics and/or dissenters may oppose taboos, they are put into place to avoid disrespect to any given authority, be it legal, moral and/or religious.53

Topography as the study of place, distinguished… by focusing not on the physical shape of the surface, but on all details that distinguish a place. It includes both textual and graphic descriptions… New Topography, [is] a movement in photographic art in which the landscape is depicted complete with the alterations of humans54 … New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape was an exhibition that epitomised a key moment in American landscape photography at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in January 1975.55

Morality is a sense of behavioural conduct that differentiates intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good (or right) and bad (or wrong)… Morality has two principal meanings:

~ In its “descriptive” sense, morality refers to personal or cultural values, codes of conduct or social mores that distinguish between right and wrong in the human society. Describing morality in this way is not making a claim about what is objectively right or wrong, but only referring to what is considered right or wrong by people

~ In its “normative” sense, morality refers directly to what is right and wrong, regardless of what specific individuals think… It is often challenged by a moral skepticism, in which the unchanging existence of a rigid, universal, objective moral “truth” is rejected…”56

Other: A person’s definition of the ‘Other’ is part of what defines or even constitutes the self and other phenomena and cultural units. It has been used in social science to understand the processes by which societies and groups exclude ‘Others’ whom they want to subordinate or who do not fit into their society… Othering is imperative to national identities, where practices of admittance and segregation can form and sustain boundaries and national character. Othering helps distinguish between home and away, the uncertain or certain. It often involves the demonisation and dehumanisation of groups, which further justifies attempts to civilise and exploit these ‘inferior’ others.

De Beauvoir calls the Other the minority, the least favoured one and often a woman, when compared to a man… Edward Said applied the feminist notion of the Other to colonised peoples.57

Endnotes

1. Anon. “Escapism has its price, The artist has his income,” on Non Fides website. [Online] Cited 28/09/2012. No longer available online

2. Editors note in Lombroso, Cesare, Gibson, Mary and Rafter, Nicole Hahn. “Photographs of Born Criminals,” chapter in Criminal man. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006, p. 203

3. See Maxwell, Anne. Picture Imperfect: Photography and Eugenics, 1870-1940. Sussex Academic Press, 2010

“The book looks at eugenics from the standpoint of its most significant cultural data – racial-type photography, investigating the techniques, media forms, and styles of photography used by eugenicists, and relating these to their racial theories and their social policies and goals. It demonstrates how the visual archive was crucially constitutive of eugenic racial science because it helped make many of its concepts appear both intuitive as well as scientifically legitimate.”

4. See Mifflin, Jeffrey. “Visual Archives in Perspective: Enlarging on Historical Medical Photographs,” in The American Archivist Vol. 70, No. 1 Spring/Summer 2007, pp. 32-69 [Online] 17/09/2012.

5. See Anon. “Andre Adolphe Eugene Disderi: Dead Communards,” on History of Art: History of Photography website [Online] Cited 17/09/2012. www.all-art.org/history658_photography13-8.html

6. Anon. “Taxonomy,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 17/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxonomy

7. Mifflin, Jeffrey p. 35

8. Wallis, Brian. “Black Bodies, White Science,” in American Art 9 (Summer 1995), p. 40 quoted in Mifflin, Jeffrey p. 35. He goes on to explain that photographs that once circulated out of family albums, desk drawers, etc., have often been “displaced” to the “unifying context of the art museum.”

9. Long, Brian. Notes on marking of short transgressive essay. 31/10/2010

10. Schwartz, Joan M. “Negotiating the Visual Turn: New Perspectives on Images and Archives,” in American Archivist 67 (Spring/Summer 2004), p. 110 quoted in Mifflin, Jeffrey p. 35

11. Bunyan, Marcus. “Science, Body and Photography,” in Bench Press chapter of Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male. Melbourne: RMIT University, 2001 [Online] Cited 17/09/2013. No longer available online

See also Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988, p. 85

12. Bunyan, Marcus. “Baron von Gloeden,” in ‘Historical Pressings’ chapter of Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male. Melbourne: RMIT University, 2001 [Online] Cited 02/09/2012.

13. Smalls, James. The homoerotic photography of Carl Van Vechten: public face, private thoughts. Philadeplhia: Temple University Press, 2006, p.32

14. Rittelmann, Leesa. “Facing Off: Photography, Physiognomy, and National Identity in the Modern German Photobook,” in Radical History Review Issue 106 (Winter 2010), p. 148

15. Ibid., p. 155

16. Long, Rose-Carol Washton. “August Sander’s Portraits of Persecuted Jews,” on the Tate website, 4 April 2013 [Online] Cited 26/10/2013. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/19/august-sanders-portraits-of-persecuted-jews

17. Smail, David. Illusion and Reality: The Meaning of Anxiety. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1984, pp. 152-153

18. Manchester, Colin. “Obscenity, Pornography and Art,” on Media & Arts Law Review website [Online] Cited 21/09/2012.

19. Hall, Alan. “Famous Hitler photograph declared a fake,” on The Age newspaper website. October 20th, 2010 [Online] Cited 21/09/2012. www.theage.com.au/world/famous-hitler-photograph-declared-a-fake-20101019-16sfv.html

“A historian claims the Nazi Party doctored a photo to drum up support. Allan Hall reports from Berlin.

It is one of the most iconic photographs of all time, the image that showed a monster-in-waiting clamouring with his countrymen for glory in the war meant to end all wars. Adolf Hitler waving his straw boater with the masses in Munich the day before Germany declared war on France in August 1914 is world famous… and now declared to be a fake.

A prominent historian in Germany says the Nazi Party doctored the image shortly before a pivotal election to show the Führer was a patriot. Gerd Krumeich, recognised as Germany’s greatest authority on World War I, says he has spent years studying the photo and has come to the conclusion that the man who took it – Heinrich Hoffmann – was also the man who doctored it. The photograph first appeared on the pages of the German Illustrated Observer on March 12, 1932 – the day before the crucial election of the German president.

“Adolf Hitler, the German patriot is seen in the middle of the crowd. He stands with blazing eyes – Adolf Hitler,” was the breathless caption. Professor Krumeich found different versions of Hitler as he appeared in the Odeonsplatz photo in the Hoffmann archive held by the Bavarian state. He told a German newspaper:

“The lock of hair over his forehead in some looked different. Furthermore, I searched in archives of the same rally and looked at numerous different photos from different angles at the spot where Hitler was supposed to have been. And I cannot find Hitler in any of them. It is my judgement that the photo is a falsification.”

Professor Krumeich’s doubt caused curators at the groundbreaking new exhibition in Berlin about the cult of Hitler to insert a notice by the photo saying they could not verify its authenticity.”

20. Anon. “Cultural Hegemony,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_hegemony. See the work of Antonio Gramsci and his theory of cultural hegemony.

21. Anon. “Patriarchy,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patriarchy

22. Anon. “Individualism,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Individualism

23. Anon. “Family values,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_values

“Family values are political and social beliefs that hold the nuclear family to be the essential ethical and moral unit of society.”

24. Anon. “Norm (sociology),” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norm_(sociology)

“Social norms are the behaviours and cues within a society or group. This sociological term has been defined as “the rules that a group uses for appropriate and inappropriate values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours. These rules may be explicit or implicit. Failure to follow the rules can result in severe punishments, including exclusion from the group.””

25. See Anon. “Morality,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality

26. See Anon. “Ethics,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethics

27. Anon. “Part Four: More Legal Issues in Creative Projects,” in How2Where2. Australia Council for the Arts website [Online] Cited 17/09/2012.

28. See Anon. “Shock art,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shock_art

29. Anon. “More harm in sport than nudes: Henson,” on 9 News website. Posted 02/08/2010. [Online] Cited 22/10/2010. No longer available.

See also AAP. “Stars back controversial photographer Bill Henson,” on News.com.au website. Posted 27/05/2008. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. No longer available online. A good summary of the events can be found at the Slackbastard blog with attendant links to newspaper articles. Anon. “Bill Henson: Art or pornography?” on Slackbastard blog. Posted 25/08/2010. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012. slackbastard.anarchobase.com/?p=1174

More recently see Hunt, Nigel. “Bill Henson pulls controversial exhibition at Art Gallery after call from detective to Jay Weatherill,” on The Advertiser website September 18, 2013 [Online] Cited 22/10/2013.

www.adelaidenow.com.au/entertainment/arts/bill-henson-pulls-controversial-exhibition-at-art-gallery-after-call-from-detective-to-jay-weatherill/news-story/e34f5e45bdd4b8d3aac9bc7cc0edf0b6

30. Australia Council for the Arts. “Protocols for working with children in art,” on the Australia Council for the Arts website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012.

31. See Anon. “Social Conservatism,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 22/09/2012.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_conservatism

“Social conservatism is a political or moral ideology that believes government and/or society have a role in encouraging or enforcing what they consider traditional values or behaviours… Social conservatives in many countries generally: favor the pro-life position in the abortion controversy; oppose all forms of and wish to ban embryonic stem cell research; oppose both Eugenics (inheritable genetic modification) and human enhancement (Transhumanism) while supporting Bioconservatism; support a traditional definition of marriage as being one man and one woman; view the nuclear family model as society’s foundational unit; oppose expansion of civil marriage and child adoption rights to couples in same-sex relationships; promote public morality and traditional family values; oppose secularism and privatisation of religious belief; support the prohibition of drugs, prostitution, premarital sex, non-marital sex and euthanasia; and support the censorship of pornography and what they consider to be obscenity or indecency.”

32. Bunyan, Marcus. “Research notes on George Platt Lynes Photographs from the Collection at the Kinsey Institute, Bloomington, Indiana,” in Pressing the Flesh: Sex, Body Image and the Gay Male. Melbourne: RMIT University, 2001 [Online] Cited 02/09/2012. No longer available online

33. “It seems hard to believe now, in 2009, that many of these images were once considered vulgar and obscene, and a violation of common decency. Even more difficult to wrap our heads around is the fact that people went to jail for merely possessing them, rather than producing them. One thinks of the noted critic Newton Arvin, a professor at Smith College, and lover of Truman Capote’s, who was disgraced when a collection of relatively innocent physique photography was found in his apartment. Today he’d be on Charlie Rose talking about the joys of the art form. We’ve come a long way. But perhaps not far enough. I’m not able to post some of the more explicit images from this book here on my blog without risking its being banished to the adult section of Google’s blog services.”

Peters, Brook. “Renaissance Men,” on An Open Book blog, June 19th 2009. [Online] Cited 05/11/2010. No longer available online

34. International Federation of Arts Councils and Culture Agencies (IFACCA). “Statistical Indicators for Arts Policy,” on the IFACCA website, Sydney, 2005, p. 7 [Online] Cited 05/11/2010. No longer available

35. Gaut, Berys. Art, emotion and ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 1 The Long Debate, 2007, p. 7

36. Ibid., p. 11

37. Anon. “Is it art or is it porn?” in The Australian. February 23rd 2008 [Online] Cited 07/09/2012.

38. Duelund, Peter. “The rationalities of cultural policy: Approach to a critical model of analysing cultural policy,” in Nordic Cultural Institute Papers 2005 [Online] Cited 05/09/2012.

39. Johnson, Denise. “Politics,” on Slide Projector website [Online] Cited 05/11/2010. No longer available

40. Gilchrist, Kate. “God does not live in Victoria,” on ‘Does Blasphemy Exist?’ web page of the Arts Law Centre of Australia Online website [Online] Cited 06/10/2010. No longer available

41. Long, Brian. Notes on marking of short transgressive essay. 31/10/2010

42. Long, Brian. Notes on marking of short transgressive essay. 31/10/2010

43. Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988, p. 87

44. Hayles, Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999, pp. 30-33

45. Anon. “Transgressive Art,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transgressive_art

46. Anon. “Subversion,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. /en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subversion

47. Anon. “Blasphemy,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy

48. Anon. “Blasphemy law in Australia,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blasphemy_law_in_Australia

49. Anon. “Defamation,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamation

50. Anon. “Obscenity,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obscenity

51. Anon. “Freedom of Speech,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedom_of_speech

52. Anon. “Censorship,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Censorship

53. Anon. “Taboo,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taboo

54. Anon. “Topography (disambiguation),” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Topography_(disambiguation)

55. Anon. “New Topographics,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Topography

56. Anon. “Morality,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morality

57. Anon. “Other,” on Wikipedia website. [Online] Cited 11/09/2012. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Other

LIKE ART BLART ON FACBEOOK

Back to top

0.000000

0.000000

![Michael Riley (Australian, 1960-2004) 'Untitled' from the series 'Cloud [Feather]' 2000 Michael Riley (Australian, 1960-2004) 'Untitled' from the series 'Cloud [Feather]' 2000](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/riley-web.jpg)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Political Prisoner [Erich Sander]' 1943, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Political Prisoner [Erich Sander]' 1943, printed 1990](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/august-sander-political-prisoner-erich-sander-1943-photograph-gelatin-silver-print-on-paper-b.jpg?w=650&h=851)

![George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955) 'Tex Smutley and Buddy Stanley [no title (two sleeping boys)]' 1941 George Platt Lynes (American, 1907-1955) 'Tex Smutley and Buddy Stanley [no title (two sleeping boys)]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/george-platt-lynes-united-states-of-america-1907-e28093-1955-tex-smutley-and-buddy-stanley-no-title-two-sleeping-boys-1941-gelatin-silver-photograph-printed-image-19-2-h-x-24-4-w-cm.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.