Exhibition dates: 11th October 2023 - 7th January 2024

Curators: Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine is curated by Hayward Gallery Director Ralph Rugoff with Assistant Curators Thomas Sutton and Gilly Fox, and Curatorial Assistant Suzanna Petot.

Please note: The (retired) WordPress theme that I have been using since Art Blart started in 2009, and which was the look of the site, decided to stop loading the posts on desktop and iPad. No support and it will not be fixed. So please bear with me as I customise and adjust the site to the new theme… a lot of work! ~ Marcus

Rachael Smith

Hiroshi Sugimoto in the Hayward Gallery with his ‘Seascapes’ series

2023

The world is a reality,

not because of the way it is,

but because

of the possibilities it presentsFrederick Sommer

Almost real

I have an ambivalent relationship with the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto.

On the one hand I truly admire the beauty and presence of Sugimoto’s photographs; how his images “contradict the medium’s conventional tasks – to record reality as precisely as possible”; and how his work, through an investigation of “fundamental questions of space and time, past and present, art and science, imagination and reality” push at the boundaries of what a photograph is and can be through an exploration of the very nature of photography.

Through this erudite, conceptual, scientific and creative investigation, Sugimoto’s staged images proffer a reorientation of the referent – of the world, in the world – unsettling the certainty of the truth of the photograph as a visual record of the world.

In my favourite series – such as the movie in a moment Theaters (1976 – ), the stuffed animal Dioramas (1974 – ), some of the wax works dead pan Portraits (1999 -) (particularly Oscar Wilde, Queen Victoria and Princess Diana), and the Seascapes (1980 -) – I feel released from the bounds of reality as we perceive it. The artist takes me out of myself and into a new plane of existence. He has reanimated the in/animate through an alchemical process, a mystery of mysteries, to create new life – a transubstantiation of the elements earth, air, water, fire.

On the other hand I am less impressed with bodies of work that simply do not work for me… that leave me feeling cold, lifeless. Series such as Revolution (1990/2012), Lightning Fields (2009), Photogenic Drawings (2009), Architecture (1997 – below) and the recent Opticks (2018 – below), while not derivative, owe a great debt to other artists that have already strode that golden path… and have done it better.

As I have observed in another review of Sugimoto’s work: “I’m not saying Sugimoto is derivative but because of these other works, they don’t have much room to move. Indeed, they hardly move at all. They are so frozen in attitude that all the daring transcendence of light, the light! of space time travel, the transition from one state to another, has been lost. The Flame of Recognition (Edward Weston) – has gone.”

Taking his work as a whole, we observe in Sugimoto’s work a slightly malevolent aura – follow my argument here – not in the sense of the work “showing a wish to do evil to others” but through the photographs unsettling ability to confound the reality of others. The artist’s work is very male/volent, very masculine and in the Latin etymology of the word “volent” (present participle of velle to will, wish) very much (reality) constructed at the will and wish of the artist.

While Sugimoto’s volition (from Latin volo ‘I wish’) creates beautiful and subversive images of true presence and power, it is the artist’s ability to will into existence images that engage with mystical forces beyond the apparent and the factual but which live as completely real and part of the total world of man and nature … that is his most impressive attribute as an artist. Through his photographs he brings to consciousness things only a small portion of which most of us experience directly.1

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Adapted from Ansel Adams’ essay for The Flame of Recognition 1964 in “Edward Weston’s The Flame of Recognition” on the Aperture website August 12, 2015 [Online] Cited 22/12/2023

Many thankx to the Hayward Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“All my life I have made a habit of never believing my eyes.”

Hiroshi Sugimoto

“Sugimoto’s unique accomplishments in his genre contradict the medium’s conventional tasks – to record reality as precisely as possible. In Sugimoto’s work, one is confronted with the formal reduction of conceptual images, in which he addresses fundamental questions of space and time, past and present, art and science, imagination and reality. “I was concerned,” noted the artist in 2002, “with revealing an ancient stage of human memory through the medium of photography. Whether it is individual memory or the cultural memory of mankind itself, my work is about returning to the past and remembering where we came from and how we came about.” His pictures, which leave a lasting impression through their beauty and their auratic effect, interweave Japanese traditions with Western ideas. This East-West dialogue remains characteristic of his work today, which is captivating in its exceptional craftsmanship and strong aesthetic presence, and can exercise an almost magical effect on viewers.”

Anonymous. “Hiroshi Sugimoto. Revolution,” on the Museum Brandhorst website February 8, 2013

Hiroshi Sugimoto | curator tour with Ralph Rugoff | Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto: ‘My camera works as a time machine’ | Hayward Gallery

‘A camera can be able to stop the world, in that we stop the world and then investigate what is there, carefully.’

~ Hiroshi Sugimoto

Ahead of the opening of Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine at the Hayward Gallery – the largest survey to date of the Sugimoto’s works – we travelled to meet the photographer at the Enoura Observatory in Japan. Situated against the outer rim of the country’s Hakone Mountains, the observatory was designed by Sugimoto as a forum for disseminating art and culture.

In this short video interview Sugimoto considers the impact of the invention of the camera – with this new ability to pause the world around us – and explains how his own photography, such as his Seascapes series, draws on this idea of the camera’s ability to distort linear time.

Dioramas (1974 – )

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Dioramas (1974 – ) Silver gelatin prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

‘My life as an artist began the moment I saw that I had succeeded in bringing the bear back to life on film,’ said Sugimoto about his 1976 work Polar Bear. The image is of an Arctic diorama in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, but through clever use of framing and exposure, Sugimoto was able to make the scene appear real. As well as revisiting the museum, and others across the US, to expand his Dioramas series, Sugimoto later took a similar approach to the waxworks of Madame Tussauds in his Portraits. By removing the figures from their staged displays, and photographing them against a black backdrop with sympathetic lighting, the artist gave the impression that these famous faces had themselves modelled for his portraiture.

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Polar Bear, 1976. Silver gelatin print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Polar Bear

1976

From the Dioramas series

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

“Polar Bear” (1976) shows the majestic white animal roaring over a fresh kill: the bloodied body of a seal whose inert form is bulky and dark against an Arctic white background that stretches into the distance. Look closely and behind the bear – with its luscious coat of fur, its big paws so heavy in the snow you can almost hear it crunch – the line between two and three dimensions is just visible: a jagged crevasse in the ice floe beneath the two animals merges almost seamlessly with a painted backdrop of receding icy peaks.

The eye judders between these realities. The dead bear, momentarily brought to life by the vividness of the photograph, dies again, and is preserved again, a copy of a copy, frozen between past and present. Similar fates await a pair of ostriches defending their new hatchlings against a family of wart hogs (“Ostrich-Wart Hog,” 1980) and a placidly floating mother manatee and her calf (“Manatee,” 1994).

Emily LaBarge. “What Is Photography? (No Need to Answer That),” on the New York Times website Nov. 21, 2023 [Online] Cited 23/11/2023

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Manatee

1994

From the Dioramas series

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

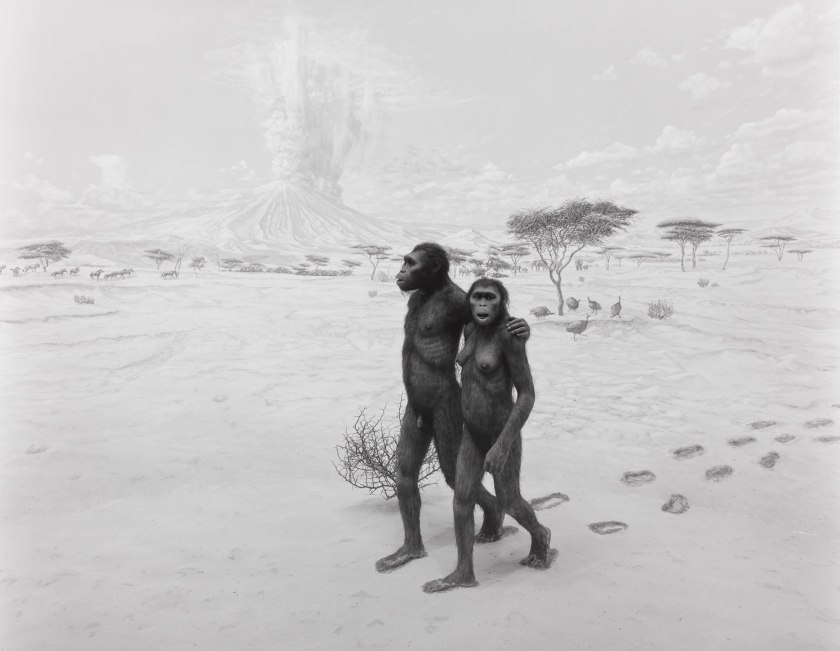

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Earliest Human Relatives

1994

From the Dioramas series

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of Marian Goodman Gallery

Theaters (1976 – ) and Abandoned Theaters (2015 – )

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

UA Playhouse, New York

1978

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Theaters series (1976 – ) Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Goshen Indiana, 1980. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Cabot Street Cinema, Beverly, Massachusetts 1978. Gelatin silver print

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Abandoned Theaters series (2015 – ). Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Kenosha Theater, Kenosha

2015

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Union City Drive-in, Union City, 1993. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

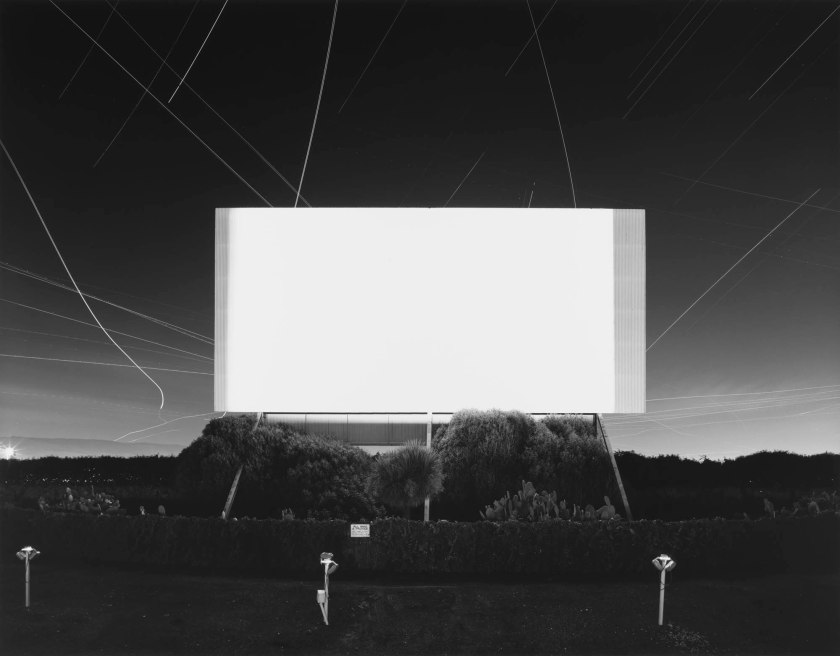

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Union City Drive-in, Union City

1993

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

The largest survey to date of Hiroshi Sugimoto, an artist renowned for creating some of the most alluringly enigmatic photographs of our time. Over the past 50 years, Sugimoto has created pictures which are meticulously crafted, deeply thought-provoking and quietly subversive.

Featuring key works from all of the artist’s major photographic series, this survey highlights Sugimoto’s philosophical yet playful inquiry into our understanding of time and memory, and photography’s ability to both document and invent.

The exhibition also includes lesser-known works that reveal the artist’s interest in the history of photography, as well as in mathematics and optical sciences.

Often employing a large-format wooden camera and mixing his own darkroom chemicals, Sugimoto has repeatedly re-explored ideas and practices from 19th century photography while capturing subjects including dioramas, wax figures and architecture. His work has stretched and rearranged concepts of time, space and light that are integral to the medium.

Born and raised in Tokyo, Japan, Hiroshi Sugimoto divides his time between Tokyo and New York City. Over the past five decades, his photographs have received international acclaim and have been presented in major institutions across the globe.

While best known as a photographer, Sugimoto has more recently added architecture and sculpture to his multidisciplinary practice, as well as being artistic director on performing arts productions.

Text from the Hayward Gallery website

Seascapes (1980 -)

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Seascapes series. Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Seascapes series. Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Bay of Sagami, Atami

1997

From the Seascapes series

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Architecture (1997 – )

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Chrysler Building 1997. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Chrysler Building 1997. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Chrysler Building

1997

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

World Trade Center

1997

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Eiffel Tower

1998

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Over the past 50 years, Hiroshi Sugimoto has created some of the most alluringly enigmatic photographs of our time: pictures that are precisely crafted and deeply thought-provoking, familiar yet tantalisingly ambiguous. Featuring key works from all of the artist’s major photographic series, this survey highlights the artist’s philosophical yet playful inquiry into our understanding of time and memory, and the ambiguous character of photography as a medium suited to both documentation and invention.

The exhibition also includes lesser-known works that illuminate the artist’s interest in the history of photography as well as in mathematics and optical sciences. Often employing a large-format wooden camera, mixing his own darkroom chemicals and developing his black-and-white prints by hand, Sugimoto has repeatedly re-explored ideas and practices from 19th century photography, including subjects such as dioramas, wax figures and architecture. In the process, his work has stretched and rearranged concepts of time, space and light that are integral to the medium.

Hiroshi Sugimoto says: “The camera is a time machine capable of representing the sense of time… The camera can capture more than a single moment, it can capture history, geological time, the concept of eternity, the essence of time itself… The more I think about that sense of time, the more I think this is probably one of the key factors of how humans became humans.”

Ralph Rugoff, Director of the Hayward Gallery, says: “Hiroshi Sugimoto is a brilliant visual poet of paradox, a polymath postmodern who embraces meticulous old school craftsmanship to produce exquisite, uncanny pictures that reference science and maths as well as abstract art and Renaissance portraits. Juggling different conceptions of time, and evoking visions ranging from primordial prehistory to the end of civilisation, his photographs ingeniously recalibrate our basic assumptions about the medium, and alter our sense of history, time and existence itself. Amidst all his peers, his work stands apart for its depth and striking originality of thought.”

Time Machine commences with a selection of Sugimoto’s black-and-white photographs of natural history dioramas, a series he began in the mid-1970s. The Dioramas photos draw attention less to the natural world than to its theatrical representation in museums, whilst at the same time conjuring what the artist has called the ‘fragility of existence’.

The subject of time is also explored in two subsequent bodies of work featured in the exhibition: shot in movie palaces as well as drive-ins, Sugimoto’s Theaters (1976 – ) capture entire films with a single long exposure, thus compressing all the dramatic action that appeared on screen into a single image of radiant whiteness. His renowned Seascapes (1980 -), which depict evenly divided expanses of sea and sky unmarked by any trace of human existence, are equally beguiling in their temporal reference, evoking the immediacy of abstract painting even as they speak to Sugimoto’s interest in focusing on vistas that, as he remarks, “are before human beings and after human beings.”

For Architecture (1997 – ), a series of deliberately out-of-focus studies of iconic modernist buildings – ranging from the Eiffel Tower to the Twin Towers – Sugimoto displays the expansive ambiguity that informs his art, at the same time conveying a sense of the visual germ of an idea in an architect’s imagination, as well as fashioning ghostly images of what he has described as “architecture after the end of the world.” For his subsequent Portraits (1999) series, meanwhile, the artist focused his camera on wax models of famous historical figures from Madame Tussauds; rendered more life-like in black-and-white, figures ranging from Queen Elizabeth II to Oscar Wilde and Salvador Dali take on a disarmingly lively appearance, underscoring the camera’s potential for altering our perception. As the artist has noted, “However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real.”

A final section of Hiroshi Sugimoto: Time Machine focuses on photographs that evoke different notions of timelessness, including his Sea of Buddha (1995) series, which portrays an installation in a 12th century Kyoto temple featuring 1001 gilded wooden statues of Buddha; and Lightning Fields (2006 – ), spectacular camera-less photographs created by exposing sensitised paper to electrical impulses produced by a Van der Graaf generator.

The exhibition comes to a stunning conclusion with a gallery dedicated to Sugimoto’s Opticks (2018 – ), intensely coloured photographs of prism-refracted light. Taking inspiration from Newton’s research into the properties of light whilst calling to mind colour field painting and artists like Mark Rothko, Opticks presents deeply immersive fields of subtly varying hues.

Alongside his photographs, two of Sugimoto’s elegantly contoured and polished aluminium sculptural models are presented, alluding to both mathematical equations and the abstract forms favoured by modernists such as Constantin Brâncuși.

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully-illustrated, 216pp catalogue with newly commissioned essays and an illustrated chronology, co-published with Hatje Cantz. Texts by Ralph Rugoff (on Dioramas), James Attlee (on Theaters), Mami Kataoka (on Seascapes), Lara Strongman (on Portraits), Geoffrey Batchen (on Lightning Fields), Edmund de Waal (on Sea of Buddha), Margaret Wertheim (on Conceptual Forms), Allie Biswas (on Opticks) and David Chipperfield (in conversation, on Architecture).

The show is set to tour internationally in 2024, at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art (23 March – 23 June 2024) and The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (2 August – 27 October 2024).

Press release from the Hayward Gallery

Sea of Buddha (1995)

Installation views of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Sea of Buddha series. Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Sea of Buddha 049 (Triptych) 1995. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Sea of Buddha 049 (Triptych)

1995

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Chamber of Horrors (1994 – ) and Portraits (1999 -)

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Chamber of Horrors series. Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, The Garrote 1994. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, The Electric Chair 1994. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

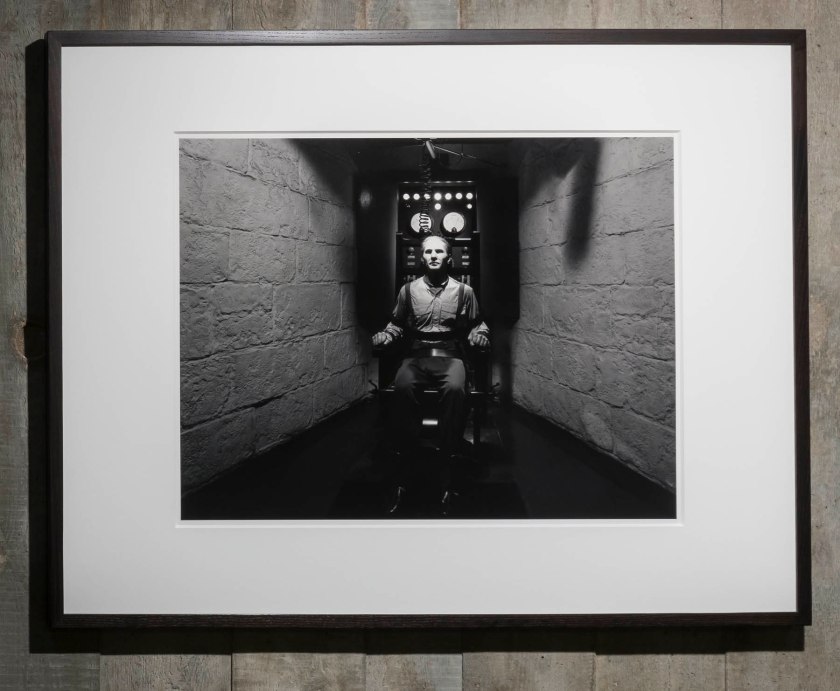

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

The Electric Chair

1994

From the series The Chamber of Horrors

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, The Plague, 1994. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Portraits series. Gelatin silver prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Anne Boleyn 1999. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Anne Boleyn

1999

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Queen Victoria 1999. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Queen Victoria

1999

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Salvador Dali

1999

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Oscar Wilde

1999

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation views of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Diana, Princess of Wales 1999. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Diana, Princess of Wales

1999

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Lightning Fields (2006 – )

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields 163 2009. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields 163 2009. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Lightning Fields 225

2009

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto: formative years and significant works

For five decades the work of photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto has received international acclaim, whilst being presented in major galleries and institutions the world over.

Sugimoto’s photographs are meticulously crafted, often stretching and rearranging the concept of time, and our understanding of the world around us, and he has often re-explored ideas and practices from photography’s earliest exponents. Over the past 50 years, he has often revisited and expanded upon his own ideas, and series, which we take a closer look at, along with the artist’s formative years, here.

Hiroshi Sugimito: early years

Hiroshi Sugimoto was born in Tokyo in 1948 to a family of merchants. Among the young Sugimoto’s interests were trains, electronics, carpentry and photography, with his early fascination with the latter further enhanced by one of his elementary school science teachers, who showed Sugimoto and his classmates how to use photosensitive paper to make photograms. ‘He used spoons and forks and other items and he exposed the paper under the light for five or six minutes.’ explained Sugimoto, looking back. ‘When he removed it, the shapes of the spoons and forks remained on the paper. It was an amazing experience for me that left a lasting impression’.

At the age of 12 Sugimoto was given his first camera, a Mamiya 6 medium-format, by his father, which he would use to take photographs of trains and gather reference material for model-making. When he moved on to high school, Sugimoto joined the photography club and also began developing an interest in the cinema, which he would visit regularly. It wasn’t long before his love of film and photography combined, as he recalls, ‘Audrey Hepburn was beautiful and I fell in love with her on the screen. I wanted her portrait so I brought my Minolta SR7 camera into a movie theatre, and I studied how to stop the image on the screen. I found that one-fifteenth and one-thirteenth of a second stops the image’.

In 1970, after graduating in Economics from Tokyo’s Rikkyo University, Sugimoto backpacked across Russia and Europe. Influenced by communist ideology, and the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as a student, he had wanted to experience Russian society, but disillusioned by what he found, he duly continued on to Europe. ‘I kept moving westwards. I stayed in Moscow for a few weeks and took another train to Poland, and then to Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and other Eastern European countries. After several weeks I arrived in Vienna for my first taste of Western civilization’.

Hiroshi Sugimoto in America

Later in 1970 Sugimoto would get another taste of Western civilisation as he travelled to the US, and California. Here he studied at Los Angeles’ ArtCentre College of Design, specialising in photography. Speaking of his studies here, Sugimoto has said ‘ArtCenter College was more like a training school for technicians: car design and advertising. For photography you trained to be a commercial photographer, which is what I wanted. I wasn’t interested in academic study at all’.

After completing his study in Los Angeles Sugimoto moved to New York in 1974 in order to pursue a full-time career in photography. Here, Sugimoto soon became part of the city’s hippy counter-culture. ‘I got serious about using photography as a tool in my art after I moved to New York’, says Sugimoto. ‘I saw many good shows, mainly minimalist shows: Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd. When I moved to the East Coast I found so many interesting people that I decided to stay. I’d just finished my photographic studies and was hungry to work. Since photography was considered a second-class citizen in the art world then why not use photography? It was more interesting for me to start with something a step down and bring it up’.

Dioramas

In 1974, Sugimoto made his first visit to the American Museum of Natural History in New York, it was a visit that would inspire his first major breakthrough in photography. ‘I made a curious discovery while at the exhibition of animal dioramas,’ the artist explains. ‘The stuffed animals positioned before painted backdrops looked utterly fake, yet by taking a quick peek with one eye closed, all perspective vanished, and suddenly they looked very real. I had found a way to see the world as a camera does. However fake the subject, once photographed, it’s as good as real’.

Inspired by these taxidermy dioramas, he went on to commence his Dioramas series, which among its initial works included Polar Bear (1976) and Hyena – Jackal – Vulture (1976). Sugimoto would return to this idea two decades on, adding more works to Dioramas in the 1990s including 1994’s Earliest Human Relatives. In 1978 Polar Bear was acquired by The Museum of Modern Art, representing Sugimoto’s first photographic sale. The work was also exhibited in the museum’s Recent Acquisitions show, that same year.

Theaters

It was whilst working on his Dioramas series, that Sugimoto also found the inspiration for his next series, Theaters, as he would later detail. ‘I am a habitual self-interlocutor. One evening while taking photographs at the American Museum of Natural History, I had a near-hallucinatory vision. My internal question-and-answer session leading up to this vision went something like this: ‘Suppose you shoot a whole movie in a single frame?’ The answer: ‘You get a shining screen.’ Immediately I began experimenting in order to realise this vision’.

He began this series in 1976, by photographing St. Marks Cinema in Manhattan’s East Village, and the first group of works would also see Sugimoto capture other movie theatres and cinemas in the Northeast and Midwest of the US. It was an approach that the photographer has returned to again and again over the course of his career, firstly in 1993 when he broadened the Theaters series to include depictions of Drive-Ins across the US. The photographer later travelled to Europe, primarily Italy, to replicate the approach with Opera Houses in 2014, and then in 2015 began photographing Abandoned Theaters.

Seascapes

The seeds for Sugimoto’s Seascapes series were sown in 1980. ‘One New York night, during another of my internal question-and-answer sessions I pictured two great mountains’, the photographer has explained. ‘One, today’s Mount Fuji, and the other, Mount Hakone in the days before its summit collapsed, creating the Ashinoko crater lake. When hiking up from the foothills of Hakone, one would see a second freestanding peak as tall as Mount Fuji. Two rivals in height – what a magnificent sight that must have been! Unfortunately, the topography has changed. Although the land is forever changing its form, the sea, I thought, is immutable. Thus began my travels back through time to the ancient seas of the world’.

Sugimoto began the series that same year with a photograph of the Caribbean Sea, taken from a bluff in Jamaica while on a family holiday to the island. Seascapes would subsequently lead Sugimoto across the globe, photographing bodies of water from the Ligurian Sea viewed from Italy to the North Pacific Ocean viewed from Japan.

Chamber of Horrors and Portraits

In 1994 Sugimoto made his first visit to Madame Tussaud’s in London, where he photographed his Chamber of Horrors series on location. ‘I saw the blade that guillotined Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and the electric chair that executed the Lindbergh baby’s kidnapper, among other exhibits. They all looked very real to me’, Sugimoto said. ‘To corroborate these various murderous instruments invented by civilised men, I took the requisite eye-witness photographs: thus did people in times past face death head on’.

Sugimoto would return to the wax museum five years later to photograph his Portraits series, for which he was given special permission to remove selected figures from the display to photograph individually, among them Diana, Princess of Wales (1999), Fidel Castro (1999) and Anne of Cleeves (1999). However, he found that the exhibits he had previously captured for Chamber of Horrors had now been removed from the museum. ‘When I asked why,’ he said ‘I was told they’d been removed in a gesture to political correctness. Must we moderns be so sheltered from death?’

Opticks

In 2018 Sugimoto began printing his Opticks series, which was inspired by an 1704 work of the same name by Isaac Newton, in which Newton, through his experiments with prisms presented proof that natural light was not purely white. Drawing on Newton’s approach, Sugimoto used a batch of Polaroid film he had been gifted – one of the last batches of film Polaroid ever produced – along with a glass prism and a mirror to create condensed vivid compositions of pure colour. Sugimoto then enlarged these works into chromogenic prints. Opticks was presented for the first time in 2020 at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art in Japan, and received its first UK presentation here at the Hayward Gallery.

Anonymous. “Hiroshi Sugimoto: formative years and significant works,” on the Hayward Gallery website Fri Nov 17, 2023 [Online] Cited 19/11/2023

Opticks (2018 – )

Installation views of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series. Chromogenic prints

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Opticks isn’t the only series in which Sugimoto has experimented with historic techniques. In his 2006 series Lightning Fields, informed by the work of 19th century photography pioneer Henry Fox Talbot, Sugimoto captured the lightning-like shapes of electrical currents as they passed across a negatively-charged metal plate.

In his commitment to historic approaches the artist had initially attempted to supply the current to the plates using a hand-operated 18th century Wimshurst Electrostatic Machine, before switching to a more consistent Van de Graaff Generator.

In 2009, Sugimoto was gifted a batch of colour Polaroid film to see how a photographer who worked primarily in black and white might use it. This proved to be one of the last batches of the film ever produced (Polaroid went out of business in that same year) and would eventually find use in Sugimoto’s 2018 series, Opticks.

The images in Opticks – Sugimoto’s newest series, which has yet to be featured in any surveys of the artist’s work – are inspired by Isaac Newton’s seminal 1704 work of the same name, in which he presented proof that natural light was not purely white. Taking his cue from Newton’s experiments with prisms, Sugimoto used the Polaroid, along with glass and a mirror, to create condensed yet vivid compositions of colour in its purest form, before later enlarging these works into chromogenic prints.

Installation views of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series. Chromogenic print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation views of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series. Chromogenic print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series. Chromogenic print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Opticks series. Chromogenic print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Rachael Smith

Hiroshi Sugimoto in the Hayward Gallery with his ‘Opticks’ series

2023

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Conceptual Forms 0003 and Mathematical Model 002. Gelatin silver print, aluminium and steel

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Conceptual Forms 0003 2004. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Conceptual Forms 0003 Dini’s surface – a surface of constant negative curvature obtained by twisting a pseudosphere

2004

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Mathematical Model 002 Dini’s Surface

2005

Aluminium and steel

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Conceptual Forms and Mathematical Model 006. Gelatin silver print, aluminium and steel

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Installation view of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Conceptual Form Surface 0001 Helicoid: Minimal Surface 2004. Gelatin silver print

Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery

Hiroshi Sugimoto (Japanese, b. 1948)

Conceptual Form Surface 0001 Helicoid: Minimal Surface

2004

Gelatin silver print

© Hiroshi Sugimoto, courtesy of the artist

Hiroshi Sugimoto

Photo credit: Sugimoto Studio

Hayward Gallery

Southbank Centre, Belvedere Road,

London SE1 8XX

Wed – Fri 10am – 6pm

Sat 10am – 8pm

Sun 10am – 6pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday

![Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997 Oliver Boberg (German, b. 1965) 'Unterführung' [Underpass] 1997](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/r_p_oliver-boberg-unterfuehrungdruckbar-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

You must be logged in to post a comment.