Exhibition dates: 11th June – 16th October 2022

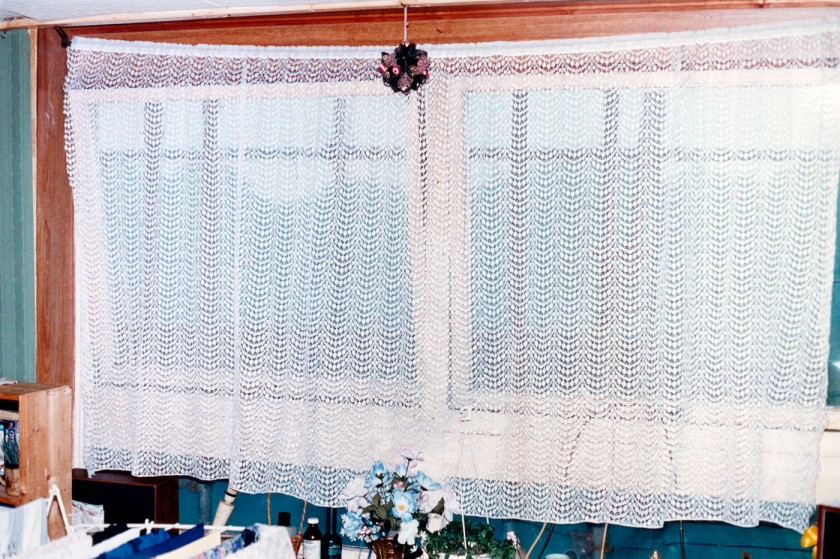

Richard Billingham (English, b. 1970)

Untitled

1990

From the series Ray’s a laugh, 1989-1996

© Richard Billingham

Blood is thicker than water (or so they say…)

Families – of whatever flavour, construction, empathy, vitriol, love, kindness, dis/affection – are depicted in photographs that shine light on photography’s treatment of the (elective) family and its representation of it as a social and cultural construct.

Today, there are so many alternatives to the “nuclear” family (what an irony that term is, although “nuclear” has links to the word “nucleus” ie, essential, long before the advent of nuclear energy) – that is a couple and their dependent children, regarded as a basic social unit – that it is a joy to celebrate the diversity of “family”, much to the annoyance and distaste of conservative, religious fundamentalists. Family can be anything that we would like to make it!

Personally, I envy those that had a blissful family childhood without the violence and abuse. I really can’t imagine what that would have been like, to have a mother and father that openly expressed love and kindness to their children. I am thankful I had a brother that I was close with, but even that was split asunder, not to be rekindled for many a year. But that upbringing has shaped who I am today. And now I surround myself with my straight and gay family.

As I say, families smamlies!

Can’t live with ’em, can’t live without them.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Fotomuseum Winterthur, Zurich for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Family means (chosen) kinship, blood ties and sometimes lifelong bonds – and the perpetual renegotiation of boundaries, regardless of how much fondness and affection are involved. Kinship has at once nothing and everything to do with points of similarity and common ground in day-to-day life and with the ideas we have about everyday realities. We are part of a family – sometimes only on paper and sometimes as a community that is made up of friends who are devoted to one another over the course of their lives. Communities play a key role in today’s world: they are crucial to our decision-making and help to mould us and shape the way we think, feel and act.

The (chosen) family is depicted in different ways in photography and art: photographers document everyday family life and use the camera to capture moments of heightened emotion. Family members can also become partners in the photographic process, contributing to the act of image-making. This finds its way into the exhibition as well as genealogical projects in which artists set out to explore their own personal histories on the basis of the lives their ancestors lived.

Just like the photographic testimony we have of them, family stories speak of diversity, individuality and collectivity, intimacy and distance. Family and chosen family imply chaos and happiness, quirky habits and the sharing of everyday banalities and powerful feelings. At best, family and community represent a familiar slice of home.

Text from the Fotomuseum Winterthur website

Richard Billingham (English, b. 1970)

Untitled

1995

From the series Ray’s a laugh, 1989-1996

© Richard Billingham

Richard Billingham (English, b. 1970)

Untitled

1995

From the series Ray’s a laugh, 1989-1996

© Richard Billingham

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

From the series MOM, 2009- (installation view)

© Charlie Engman

Photo: © Fotomuseum Winterthur / Conradin Frei

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

Baseball Mom

2017

From the series MOM, 2009-

© Charlie Engman

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

Blue Mom

2017

From the series MOM, 2009-

© Charlie Engman

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

Mom calling

2019

From the series MOM, 2009-

© Charlie Engman

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

Mom in the Fields

2014

From the series MOM, 2009-

© Charlie Engman

Charlie Engman (American, b. 1987)

Mom with Kage

2013

From the series MOM, 2009-

© Charlie Engman

Seiichi Furuya (Japanese, b. 1950)

Wien

1983

From the series Portrait of Christine Furuya, Graz/Wien, 1978-1984

© Seiichi Furuya and Galerie Thomas Fischer

Seiichi Furuya (Japanese, b. 1950)

Graz

1979

From the series Portrait of Christine Furuya, Graz/Wien, 1978-1984

© Seiichi Furuya and Galerie Thomas Fischer

Pixy Liao (Chinese, b. 1979)

Some Words Are Just Between Us

2013

From the series Experimental Relationship, 2007-

© Pixy Liao

Pixy Liao (Chinese, b. 1979)

Things We Talked About

2013

From the series Experimental Relationship, 2007-

© Pixy Liao

Pixy Liao (Chinese, b. 1979)

It’s Never Been Easy to Carry You

2013

From the series Experimental Relationship, 2007-

© Pixy Liao

Installation view of the exhibition Chosen Family – Less Alone Together at the Fotomuseum Winterthur showing at left, Pixy Liao’s work from the series Experimental Relationship (2007-, above); and at right, Dayanita Singh’s work from the series The Third Sex Portfolio (1989-1999, below)

Photo: © Winterthur / Conradin Frei

Pixy Liao (Chinese, b. 1979)

Carry The Weight Of you

2017

From the series Experimental Relationship, 2007-

© Pixy Liao

Pixy Liao (Chinese, b. 1979)

Find A Woman You Can Rely On

2018

From the series Experimental Relationship, 2007-

© Pixy Liao

The exhibition Chosen Family – Less Alone Together draws on international positions and works from the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur to shed light on photography’s treatment of the (elective) family and its representation of it as a social and cultural construct. The artistic approaches on display are as varied as the different family stories they depict. In addition to the works of professional photographers and artists, the museum also presents personal photo albums, showing the family stories of people from Winterthur and from all over Switzerland.

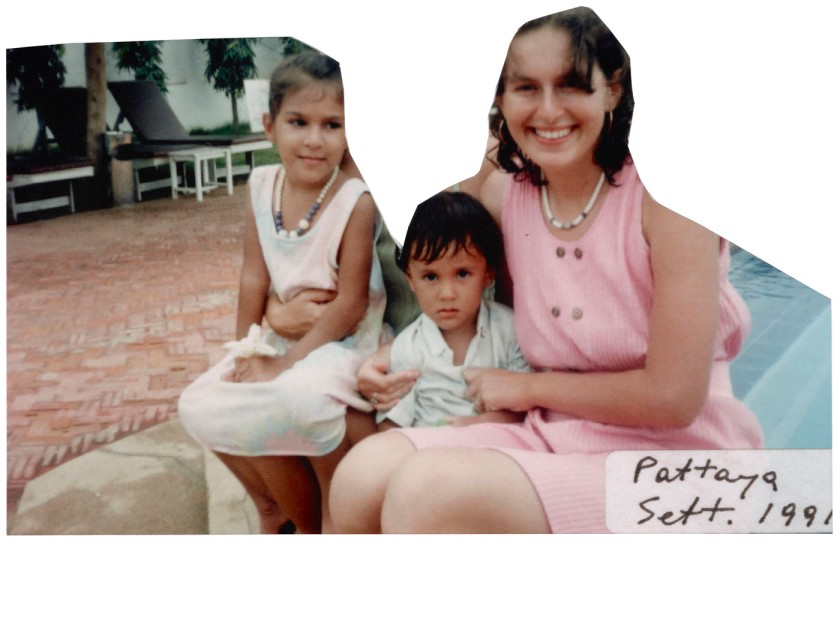

The exhibition Chosen Family – Less Alone Together presents works by contemporary photographers who delve into their own family history, examining and exploring their past. Alba Zari‘s work involves a reappraisal of her own family history mediated by pictures from her family archive and contemporary photographic documents. The artist – who was born into a fundamentalist Christian sect – uses scraps of text and image fragments to investigate the history of her family and explore her own identity in the process. The photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa also uses pictures to reconstruct events from the past. When he was just seven, his sister, who was six years older than him, disappeared without a trace and did not return until ten years later. With the help of a documentary photo book, Sobekwa attempts to create a picture – quite literally – of this formative point in his life, a time he knows very little about and which no one has spoken about for ages. Richard Billingham, meanwhile, grapples with his own history and biography by making a loving yet unsparing record of his parents’ life and day-to-day reality, in the process showing a domestic world shaped by poverty and addiction. Diana Markosian processes her family history in a short film featuring actors she cast in their roles and clever set photography. Her narrative video sequences re-enact her own childhood memories, which she stages as cinematic imagery. The film’s perspective is shaped by the experience of migration undergone by her mother, who left her husband after the break-up of the Soviet Union and moved with her children to the US to marry an American.

Other artists present themselves and members of their family in sometimes elaborately staged settings. By breaking open and re-enacting the family structures, their work reflects on the roles played by the individual family members and the photographers’ own position within this constellation. This way of exploring family dynamics turns members of the family into collaborative partners in the image-making process. Charlie Engman, for example, presents his ‘mom’ in settings that have little in common with our conception of a mother’s everyday reality: we may see her posing in a hydrogen-blonde wig, with blue eyeshadow and a fierce, challenging look, or climbing up a rope ladder fixed to a tree, wearing white knickers. Engman’s work playfully calls into question the one-dimensional image of the caring mother. Pixie Liao also takes a playful approach as she bucks classic role models: her portraits of herself together with her partner subtly subvert stereotypical ideas of men and women. The photographs show her partner resting his head on her shoulder or being held in her arms. Photographer Leonard Suryajaya, meanwhile, stages his parents and extended family using symbolically charged props in elaborately arranged environments fitted out with rugs and fabrics. The at times quirky interactions between individual members of the family are at odds with our idea of a conventional family portrait.

Other artistic explorations focus on the fact that family can be defined by much more than just (blood) kinship and is experienced via community constellations with deep bonds. These works show how photography can be a means of creating new ‘images of family’ that offer an alternative to middle-class notions of it. Their depictions of communities that exist outside traditional constellations challenge our concept of how a conventional family looks. Dayanita Singh, for example, took pictures of Mona Ahmed and her adopted daughter Ayesha during the 1990s. Ahmed identifies as a hijra, as part, that is, of a community that rejects a binary view of gender and the norms it imposes. Members of the community, which has existed for thousands of years, were criminalised under British colonial rule and they are still exposed to discrimination and violence today. As viewers of Singh’s work, we are confronted with images that challenge our idea of traditional families and communities. Photographer Mark Morrisroe also depicts a sense of cohesiveness apart from kinship in portraits of his friends and lovers – his gang – who were the hub of his daily activities and a pivotal element in his life. The pictures reveal the deep emotional connection between the protagonists, expressing complicity and a sense of belonging, an embodiment of the idea of elective family.

In addition to the works of international artists, Fotomuseum Winterthur is also exhibiting photo albums and presenting the stories of families from Winterthur and Switzerland in association with the pictures. As part of an open call, the museum is offering people the opportunity to share their personal family stories with visitors and to display their family photos in one of the exhibition spaces.

An exhibition of international loans and items from the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur, curated by Nadine Wietlisbach with the support of Katrin Bauer. With works by Aarati Akkapeddi, Richard Billingham, Larry Clark, Charlie Engman, Seiichi Furuya, Nan Goldin, Pixy Liao, Diana Markosian, Anne Morgenstern, Mark Morrisroe, Dayanita Singh, Lindokuhle Sobekwa, Annelies Štrba, Leonard Suryajaya and Alba Zari. Christoph Merian Verlag will publish the book ChosenFamily – Less alone together as an adjunct to the exhibition.

Selection of Artists

Alba Zari (b. 1987) embarks on a forensic photographic search in her ongoing work Occult, which sets out to explore her family history. The Italian artist was born into the fundamentalist Christian sect The Children of God (now known as The Family International) after her grandmother and mother fell into its clutches at the ages of 33 and 13 respectively. The cult was discredited because it encouraged sex with minors and forced women into prostitution as a way to ‘recruit’ new members. Using her family archive as well as texts and visuals of the sect, archive images of other members and found material from the internet, Zari explores her own family history, while also reflecting on the propaganda tools and mechanisms deployed by the Children of God. The photographs in Zari’s work function both as source materials and as a medium in themselves. Her compilation of these different images not only indicates how photographs are used to spread untruths but also helps to reveal and expose them to critical view. The artist’s multimedia research thus renders an overall sense of the categories and symbols we use to define and represent family, yielding a picture that is at once self-reflexive and charged with social criticism.

Seiichi Furuya (b. 1950) took portrait pictures of his wife Christine Gössler over a period of several years. Furuya was fascinated by his partner from the moment they met and was deeply attached to her. For him, photography was a way to capture the numerous facets of the woman who was both his wife and the mother of his child. What was key here was not so much the finished picture but rather the brief, rapt moment of being face to face with one another. His photographs were not just an observation of his subject but also an act of self-discovery. The relationship between the couple came to a tragic end when Christine took her own life in 1985. Furuya’s hundreds of photographs of her are still an important element in his work today and, over the decades, he has repeatedly made new compilations of them. His preoccupation with them entails grief work. As he puts it, it is a way for him to pursue the ‘truth’, even if, in the end, he only ever finds himself back with his own version of the story.

What does a modern romantic relationship look like? How is its shape determined by the expectations of the individuals involved and by social preconceptions? Pixy Liao (b. 1979) focuses on these questions in her long-term photographic project Experimental Relationship, in which the artist presents herself with her partner in a range of staged situations. The couple switch between different modes at different times and may be serious or humorous, vulnerable or self-assured. When Liao met her partner in 2005, she quickly realised that he did not fit in with the conservative ideas that had informed her socialisation, and her received sense of gender roles began to unravel. Liao used this as an opportunity to examine their relationship – along with the cultural and social dynamics inscribed in it. In her photographs, it is Liao, then, who supports her partner as he lies across her shoulders or shows him stripped down to his underpants as she – herself fully clothed, it should be noted – tweaks his nipple. It is Liao who lays the man’s naked body across a table, using it as a serving dish from which to eat a papaya. Not only are gender stereotypes and clichés inverted in Liao’s work but their power dynamics are questioned and probed in a shared performative act in front of the camera.

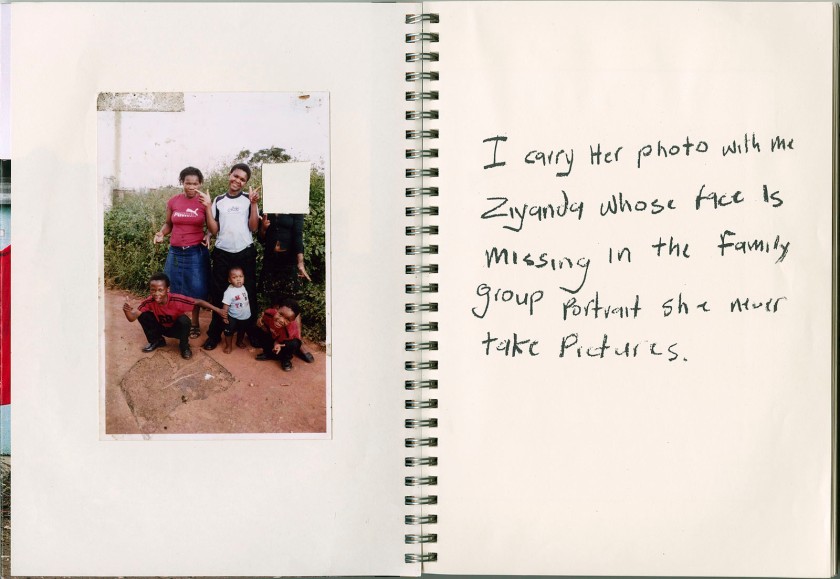

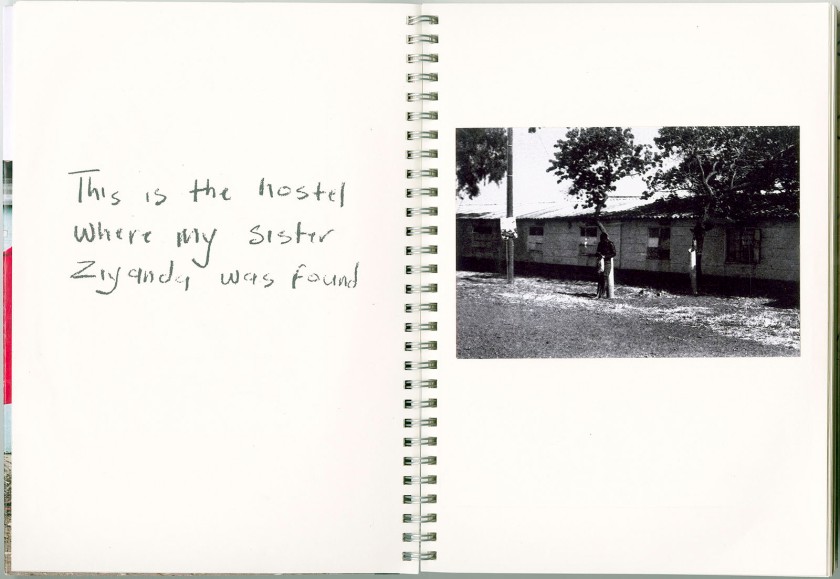

Lindokuhle Sobekwa‘s (b. 1995) handmade photo book I Carry Her Photo with Me, is an attempt on the part of the South African documentary photographer to reconstruct the life of his sister Ziyanda, who disappeared in 2002 at the age of 13. She did not return to her family until ten years later, by which time she was seriously ill and died shortly afterwards. Sobekwa’s documentary research of places where his sister stayed allows him to make artistic assumptions about her life. It is not uncommon for people in South African townships to disappear. Sobekwa’s work thus not only deals with his very personal family history but also focuses on questions affecting society as a whole. The title of the book documents Sobekwa’s desire to preserve the memory of his sister, while also standing for the effort to enshrine in the collective memory the fates of other people who have disappeared.

For all the colourful patterned wallpaper and kitschy interior decorations they show, the photographs by British artist Richard Billingham (b. 1970) are not images of a stable family in a sheltered environment. Growing up in a precarious household, affected by alcoholism, violence and his parents’ lack of prospects, Billingham began working in 1989 – at the age of 19 – on a complex photographic portrait of a dysfunctional family constellation, a project that he would continue over a period of seven years. In a bid to productively confront his day-to-day sense of powerlessness, the young artist makes his own parents’ lack of agency the tragicomic subject of his photographs. The domestic poverty in the images, which is at once tragic and sensitively portrayed, was seen by art critics as a sociopolitical comment on the upheavals of the Thatcher era. However, Billingham’s Family Album should not simply be viewed as a metaphor representing a sociopolitical crisis – it is first and foremost autobiographical in form and a means of coping with the present.

Press release from the Fotomuseum Winterthur

Diana Markosian (American-Armenian, b. 1989)

Christmas Morning

2019

From the series Santa Barbara, 2019-2020

© Diana Markosian and Galerie Les filles du Calvaire

Diana Markosian (American-Armenian, b. 1989)

Diana Markosian (born 1989) is an American artist of Armenian descent, working as a documentary photographer, writer, and filmmaker.

Markosian is known for her photo essays, including Inventing My Father, (2013-2014) about her relationship with her father, and 1915, (2015) about the lives of those who survived the Armenian genocide and the land from which they were expelled. Her most recent project, Santa Barbara, published by Aperture, reconstructs her mother’s journey from post-Soviet Russia to America, inspired by a 1980s American soap opera. Through a series of staged photographs and a narrative video, the artist reconsiders her family history from her mother’s perspective, relating to her for the first time as a woman rather than a parent, and coming to terms with the profound sacrifices her mother made to become an American.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Diana Markosian (American-Armenian, b. 1989)

The Wedding

2019

From the series Santa Barbara, 2019-2020

© Diana Markosian and Galerie Les filles du Calvaire

Diana Markosian (American-Armenian, b. 1989)

The Arrival

2019

From the series Santa Barbara, 2019-2020

© Diana Markosian and Galerie Les filles du Calvaire

My family arrived to America in 1996. My mother described it as the arrival to nowhere, with the hope of going somewhere.

Anne Morgenstern (German, b. 1976)

From the series Whatever the Fuck You Want

2018-2020

© Anne Morgenstern

Anne Morgenstern (German, b. 1976)

From the series Whatever the Fuck You Want

2018-2020

© Anne Morgenstern

Anne Morgenstern (German, b. 1976)

From the series Whatever the Fuck You Want

2018-2020

© Anne Morgenstern

Anne Morgenstern (German, b. 1976)

From the series Whatever the Fuck You Want 2018-2020 (installation view)

© Anne Morgenstern

Photo: © Fotomuseum Winterthur / Conradin Frei

Installation view of the exhibition Chosen Family – Less Alone Together at the Fotomuseum Winterthur showing at left the work of Mark Morrisroe (below), and at right, the work of Alba Zari (below)

Photo: © Winterthur / Conradin Frei

Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989)

Untitled (Lynelle)

c. 1985

Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989)

Mark Morrisroe (January 10, 1959 – July 24, 1989) was an American performance artist and photographer. He is known for his performances and photographs, which were germane in the development of the punk scene in Boston in the 1970s and the art world boom of the mid- to late 1980s in New York City. By the time of his death he had created some 2,000 pieces of work…

His career as a photographer began when he was given a Polaroid Model 195 Land Camera. He experimented with unusual development techniques, receiving generous support of supplies, film, and chemicals from the Polaroid Corporation. Within his close circle of friends he soon laid claim to the “invention” of what are called “sandwich” prints – enlargements of double negatives of the same subject mounted on top of one another – which yielded an elaborate pictorial quality, producing a very iconic painterly impression in the final result, which over time he learned to use in an increasingly controlled way.

Early on, the artist recognised the intrinsic value of prints – irrespective of the medium used to produce them – as pictorial objects that he could manipulate, colour, paint and write on at will. Thus, Morrisroe scrawled comments, biographical notes and dedications on the side of his pictures, which made them very personal pieces of art. His photographs were mostly portraits, and his subjects included lovers, friends, hustlers, and people who visited his apartment. He also often incorporated stills from Super 8 films. There are a few photographs which incorporate landscapes and external shots.

Morrisroe died on July 24, 1989, aged 30, in Jersey City, New Jersey from complications of AIDS. His ashes are scattered in McMinnville, Oregon on the farm of his last boyfriend, Ramsey McPhillips. He is considered a member of the Boston School of Photography and his work is found in many important collections including that of the Whitney and MOCA of Los Angeles. The estate of Mark Morrisroe (Collection Ringier) is currently located at the Fotomuseum Winterthur.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Mark Morrisroe (American, 1959-1989)

Ramsey (Lake Oswego)

1986

Chromogenic print

What’s most amazing about this work is that much of it was executed in impromptu darkrooms the artist rigged up in his hospital bathrooms. Morrisroe’s courageous, unrelenting drive to keep making art is inspiring. The catalogue essayists clarify a body of work done in considerable isolation; there were no longer cute friends around to get naked with (except, perhaps, the artist’s last partner, Ramsey McPhillips). Very often Morrisroe was by himself. The black-and-white Polaroids of the artist nude, lying in the sunlight, his body wasted to a bony apparition of his former saturnine self, are among the most moving in the show.

Morrisroe died, but his spirit lives on – not only in the additional prints that will no doubt now come on the market in increasing numbers, but as the avatar of young video and performance artists, like Kalup Linzy and Ryan Trecartin, who wreak havoc with gender and identity. There’s also a renewed fervor over ’80s homoerotic work and its role in the American culture wars. The recent censorship of David Wojnarowicz’s video A Fire in My Belly (1986), removed from the exhibition “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. (then screened at a dozen museums and acquired by New York’s Museum of Modern Art), provoked memories of the first fracas over Wojnarowicz’s work and NEA funding. Back then, in 1989, the controversial show was “Against Our Vanishing,” curated by Nan Goldin for Artists Space, and it included, posthumously, photographs by Morrisroe.

Brooks Adams. “Beautiful, Dangerous People,” on the Art in American website February 28, 2011 [Online] Cited 10/10/2022

Dayanita Singh (Indian, b. 1961)

On his arrival each eunuch was greeted by me with garland of jasmine flowers. Ayesha’s first birthday

1990

From the series The Third Sex Portfolio, 1989-1999

© Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh (Indian, b. 1961)

Dayanita Singh (born 18 March 1961) is an Indian photographer whose primary format is the book. She has published fourteen books.

Singh’s art reflects and expands on the ways in which people relate to photographic images. Her later works, drawn from her extensive photographic oeuvre, are a series of mobile museums allowing her images to be endlessly edited, sequenced, archived and displayed. Stemming from her interest in the archive, the museums present her photographs as interconnected bodies of work that are full of both poetic and narrative possibilities.

Publishing is also a significant part of Singh’s practice. She has created multiple “book-objects” – works that are concurrently books, art objects, exhibitions, and catalogues – often with the publisher Steidl. Museum Bhavan has been shown at the Hayward Gallery, London (2013), the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt (2014), the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (2014) and the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi (2016).

Text from the Wikipedia website

Dayanita Singh (Indian, b. 1961)

I get this strong urge to dance from within. Ayesha’s second birthday

1991

From the series The Third Sex Portfolio, 1989-1999

© Dayanita Singh

Dayanita Singh (Indian, b. 1961)

Shalu dances on Ayesha’s second birthday

1991

From the series The Third Sex Portfolio, 1989-1999

© Dayanita Singh

Lindokuhle Sobekwa (South African, b. 1995)

From the artist book I Carry Her Photo with Me

2017

Baryta paper

Artist book scan p. 3-4. 2014/2018

40cm x 60cm

Magnum Photo, Magnum Foundation, Gerhard Steidl, Subotzky Studios, David Krut Studios, Josh Ginsburg, Mark Sealy

© Lindokuhle Sobekwa and Magnum Photos

Lindokuhle Sobekwa (South African, b. 1995)

From the artist book I Carry Her Photo with Me

2017

Baryta paper

Artist book scan p. 9-10. 2014/2018

40cm x 60cm

Magnum Photo, Magnum Foundation, Gerhard Steidl, Subotzky Studios, David Krut Studios, Josh Ginsburg, Mark Sealy

© Lindokuhle Sobekwa and Magnum Photos

Annelies Štrba (Swiss, b. 1947)

Ån 22

From the series Filmstills aus Dawa-Video, 2001

C-Print

40 x 50cm

© Annelies Štrba

Annelies Štrba (Swiss, b. 1947)

Annelies Štrba is a Swiss multimedia artist, who lives in the Zurich metropolitan area. She works with video, photography, and digital media to approach her subjects, which range from domestically themed images, portraiture, and both urban and natural landscapes.

Štrba combines photography, digital media, and film to chronicle her physical and emotional life. A mother of three, she has been documenting her family environment through her work for over four decades. Her best-known bodies of work, Shades of Time, AYA, NYIMA, and her most recent publication, Noonday, depict her immediate family including her three children, and five grandchildren. Although she is working with subject matter that is very personal and quite literally close to home, Štrba constructs a quality of fantastical narrative in her pictures, utilising combinations of the different mediums in her repertoire. While creating images that evoke fantastical emotion using technological processes, she simultaneously embraces a sense from 19th-century romanticism while addressing themes of domesticity and nature.

Štrba uses a digital camera to capture moments and figures in film and still, which she then colours with the aid of computer programs. This digital manipulation provides Štrba’s images with a sense of painterliness and allows her to abandon naturalism and realist details in favour of complex visual textures. She often photographs around the family homes just outside of Zurich or in the Swiss mountains, where they spend many weekends and holidays. The product is a personal and poetically abstract documentation of the life around her, capturing her subjects at the dining room table, grooming, in the chaos of untidy rooms, or surrounded by nature. Overall, a personal story is told of the intertwined lives and relationships, speaking to memories, reactions, and nostalgic realisation.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Annelies Štrba (Swiss, b. 1947)

Ån 36

From the series Filmstills aus Dawa-Video, 2001

C-Print

40 x 50cm

© Annelies Štrba

Annelies Štrba (Swiss, b. 1947)

Ån 34

From the series Filmstills aus Dawa-Video, 2001

© Annelies Štrba

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Dad Duck

2020

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Good Neighbors

2018

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Hoda

2018

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Virtual Reality

2017

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Little Sissy

2017

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

Two Bodies

2017

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020

© Leonard Suryajaya

Leonard Suryajaya (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1988)

From the series False Idol, 2016-2020 (installation view)

© Leonard Suryajaya

Photo: © Fotomuseum Winterthur / Conradin Frei

Alba Zari (Thailand, b. 1987)

Family Archive

From the series Occult, 2019-

© Alba Zari

Alba Zari (Thailand, b. 1987)

Family Archive

From the series Occult, 2019-

© Alba Zari

Poster for the exhibition Chosen Family – Less Alone Together at the Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland

Fotomuseum Winterthur

Grüzenstrasse 44 + 45

CH-8400

Winterthur (Zürich)

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 8pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.