Exhibition dates: 29th November 2022 – 30th April 2023

Curators: Konstantin Akinsha, Katia Denysova and Olena Kashuba-Volvach

Davyd Burliuk (Ukrainian, 1882-1967)

Landscape

1912

Oil on canvas

33 x 46, 3cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

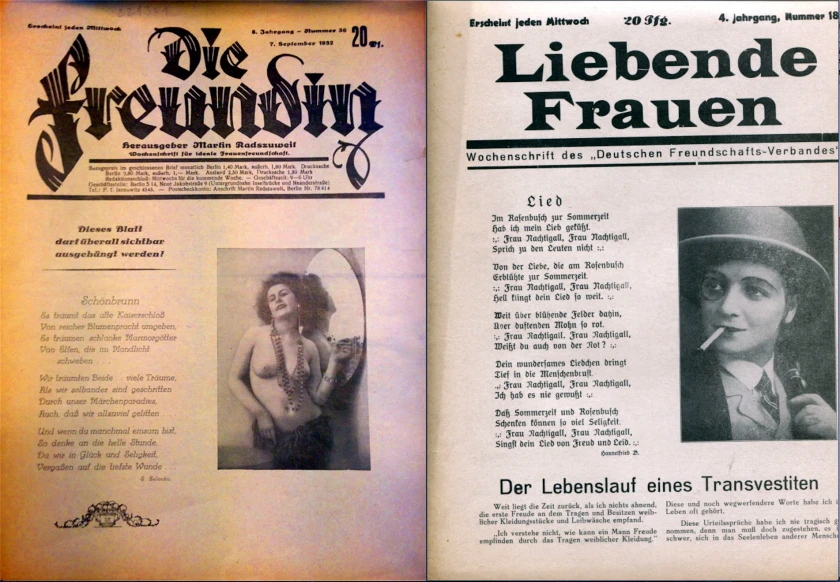

Revelation and resistance

This exhibition presents ground-breaking art produced in Ukraine in the first decades of the 20th century… in an act of ‘revelatio’, or pulling aside of the curtain to reveal what has been hidden from view in Europe for too many years.

The brief flowering of modern Ukrainian art that took place from roughly 1910s to 1933 was savagely cut short by Stalin’s purges of artists and intellectuals “in the length and breadth of the USSR, but in Ukraine repression started earlier and had a character all its own. In Russia at large, repressed artists and writers were classified as ‘enemies of people’, a broad and generic term. In Ukraine, they were accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism’, an altogether more emotive and destructive appellation. The scene was set, and the destruction of Ukrainian literature and art from 1931 onwards amounted to nothing less than mass cultural genocide.”

Many artists were either sent to the Gulag (labour camps), executed (such as the followers of Mykhalio Boichuk known as Boichukists with most of their public art subsequently destroyed) or had to adapt and tow the party line, their artistic activity cut short by a radical change in the political climate. “Art was increasingly viewed through a prism of ‘class consciousness’ and Soviet subject matter came to dominate all spheres of artistic output. In 1932, Socialist Realism was introduced as the only official artistic style to be practiced in the Soviet Union, with more value subsequently placed on the rally-like qualities in art rather than the merits of modernist experimentation.”

But as history shows us, dictatorships don’t last. As much as Stalin wanted to destroy the expression of a nascent Ukrainian modernism, a true renaissance of creative experimentation, he failed… for Stalin died and the USSR crumbled. This magnificent art remains.

And so a modern day dictator who has invaded a free Ukraine, who suppresses all opposition in his own country so ruthlessly and cruelly, will be washed with the tide of history. His secular power is vain compared to the desire for freedom… and the creativity and imagination needed to express that freedom.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“We wanted to do something in terms of showing Ukrainian art, but also taking Ukrainian art out of Ukraine and bringing it to Europe and to safety.”

Katia Denysova (curator)

Cubo-Futurism

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at right, Davyd Burliuk’s Ukrainian Peasant Woman 1910-1911

Davyd Burliuk (Ukrainian, 1882-1967)

Ukrainian Peasant Woman

1910-1911

Oil on canvas

132 x 70cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at left, Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné’s Adam and Eve 1912; and at second right, El Lissitzky’s Composition 1918-1920s

Installation views of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing in the top image, three paintings by Alexandra Exter including at left, Three Female Figures (1910) and at right Still Life (1915); and at centre in the bottom image, El Lissitzky’s Composition 1918-1920s

Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné (Ukrainian, 1888-1944)

Adam and Eve

1912

Oil on canvas

155 x 219.7cm

Colección Carmen Thyssen

Vladimir Davidovich Baranov-Rossiné (Ukrainian: Володимир Давидович Баранов-Росіне, Russian: Владимир Давидович Баранов-Россине) (13 January 1888, Velyka Lepetykha – 1944, Auschwitz) was a Ukrainian painter and sculptor active in France. Baranov-Rossiné was of Jewish origin. His work belonged to the avant-garde movement of Cubo-Futurism. He was also an inventor.

Born in Kherson, Ukraine, in 1888, Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné spent his life and career between imperial Russia and Paris. After studying in Odesa and St Petersburg, he exhibited in early avant-garde exhibitions held in Moscow and St Petersburg, alongside Mijaíl Lariónov, Natalia Goncharova, Alexandra Exter and the Burliuk brothers, among others. He also participated in an important exhibition in Kyiv in 1908 devoted to the synthesis between painting, sculpture, poetry and music. An intense interest in the idea of a synthesis of the arts, a legacy of Russian Symbolism, would remain with Baranoff-Rossiné all his life.

In 1910, he left for Paris where, aside from frequenting the circles of artists from the Russian empire, he was particularly friendly with Hans Arp and Robert and Sonia Delaunay. His colourful paintings of the period show an assimilation of Cubism, Futurism and Orphism, and he exhibited regularly at the Salon des Indépendants. At the same time, he experimented with sculpture, executing two large openwork assemblage sculptures created from fragments of painted metal, wood and found objects. One of these sculptures, exhibited at the 1914 Salon des Indépendants, provoked such consternation and ridicule that he later threw it into the Seine. Only the French critic Guillaume Apollinaire understood its radical and prescient expressive idiom, comparable to the early ‘sculpto-paintings’ produced by fellow Ukrainian Alexander Archipenko.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Baranoff-Rossiné moved to Norway, where he would remain until 1917, when he went back to Russia. Between 1917 and 1925, his production was prolific; he exhibited alongside Marc Chagall, Nathan Altman, Yurii Annenkov and other representatives of the Soviet avant-garde, and taught painting. At the same time, he explored his earlier interest in a synthesis of the arts, inventing a ‘colour-clavier’ and presenting ‘optophonic’ concerts in Moscow theatres, in which, as the piano’s keys were played, the music was ‘translated’ by coloured disks projected on a screen.

Baranoff-Rossiné returned to settle in Paris in 1925. He continued to paint in a more Surrealist manner, made a few sculptures, and experimented with materials, colours and sounds, exhibiting regularly in the Parisian Salons. His works may be found in many public collections, including those of the Russian Museum in St Petersburg, the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow, the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1943 he was arrested in France by the Gestapo and deported. He died in the Auschwitz concentration camp (Poland) in 1944.

Margit Rowell. “Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné,” on the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza website Nd [Online] Cited 23/03/2023

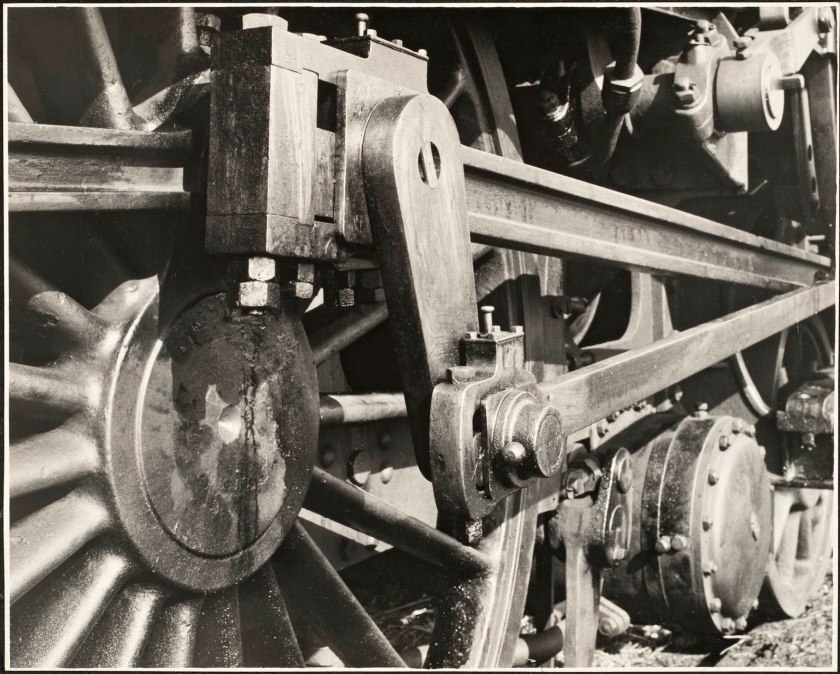

Oleksandr Bohomazov (Ukrainian, 1880-1930)

Landscape, Locomotive

1914-1915

Oil on canvas

33 x 41cm

European private collection

Alexander Bogomazov or Oleksandr Bohomazov (Ukrainian: Олександр Костянтинович Богомазов; March 27, 1880 – June 3, 1930) was a Ukrainian painter, cubo-futurist, modern art theoretician and is recognised as one of the key figures of the Ukrainian avant-garde scene. In 1914, Oleksandr wrote his treatise The Art of Painting and the Elements. In it he analyzed the interaction between Object, Artist, Picture, and Spectator and sets the theoretical foundation of modern art. During his artistic life Oleksandr Bohomazov mastered several art styles. The most known are Cubo-Futurism (1913-1917) and Spectralism (1920-1930). …

Cubo-Futurism Period, 1913-1915

Years of 1913-14 became a time of the artist’s intense search for ways to develop “new art”. In September 1914, Bohomazov finished the theoretical work “Painting and Its Elements”, which summarised his reflections on the nature of creativity and its components. The works belonging to the year 1913 were created by Bohomazov, when the main provisions included in his theoretical work had not yet been thought out and formulated, but the style and form-creating elements of these works testify that the master was already familiar with various artistic directions of avant-garde art, in particular and with the futuristic concept of displaying the state of the environment through the demonstration of the movement of the objects that made it.

In the works of this time, he intuitively, rather than consciously, uses a number of techniques that enhance the feeling of movement and convey the dynamism of the depicted object. So, for example, he actively uses a bundle of straight lines that converge and, in turn, form certain ray- and fan-like forms that create a powerful effect of movement. At the same time, the artist often uses such a technique as extending straight lines along their entire length and turning them into needle-like guides, as, for example, in the work “Train”.

The alternation of saturated sharp spots with unfilled empty spaces became for him another means of enriching the artistic language of the works. In a number of works, the artist arranges the forms he uses diagonally and at an angle to the borders of the picture plane. This technique is clearly visible in his painting “Train. Boyarka”. This method of constructing the picture plane makes it possible to create the impression of intense dynamic tension and convey the feeling of movement, regardless of whether it is connected to a specific object or insinuates itself. In the works of 1913, the artist pays a lot of attention to a straight line or a group of straight lines, which together create irregular dynamic impulses.

1914 can be considered a turning point in the artist’s work. And not only because the artist finally formulated his ideas about the art of the “New Age” in a theoretical treatise, but also because this year he established himself as an original artist. In 1914, Bohomazov began to consciously use all techniques in the reproduction of nature and its state, which had intuitively matured in previous works. He actively implements the new principles declared in ‘Painting and Its Elements’.

In the works of this year, we observe the artist’s interest in combining simple flat forms into more complex spatial objects. Bohomazov begins to understand: the planes and straight lines that form them limit the possibility of conveying the dynamism of the object – and he introduces new elements into his artistic lexicon, including various arc-shaped lines.

He also resorts to another new technique – mosaic toning of individual components, that is, fragmentary strengthening of forms, and this gives them a stronger sense of dynamism. At the same time, the structure of the picture alternates with forms with a mass of different saturation. Here we can note that this technique reflects the concept of interval formulated by the artist.

In 1914, he organised the exhibition Kiltse (“The Ring”) in Kyiv, where the works of 21 artists were exposed, among others Oleksandra Ekster, Eugène Konopatzky among others. For Bohomazov, this was the first significant exhibition, 88 of his works, mostly graphics, were presented there. Like Kandinsky during the second “Salon”, Bohomazov presented his theoretical work “The Essence of Four Elements”, in which he explained the principle of the new Cubo-Futurist art: the combination of line, colour, form and plane of the picture.

Kiltse was supposed to be the first in a series of exhibitions, but this did not go according to plan. Reviews in the press were positive (indicating the general acceptance of the “new art” in critical circles), but few. In fact, the exhibition was hardly noticed. After the failure of the “Ring”, significant avant-garde exhibitions were no longer held in Kyiv until the 20s.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Alexandra Exter (Russian, Ukrainian, French, 1882-1949)

Still Life

1913

Collage and oil on canvas

68 x 53cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© Exter-Lissim Archives, Paris

Alexandra Exter artistic periods

Kiev

Her painting studio in the attic at 27 Funduklievskaya Street, now Khmelnytsky Street, was a rallying stage for Kiev’s intellectual elite. In the attic in her studio there worked future luminaries of world decorative art Vadym Meller, Anatol Petrytsky and P. Tchelitchew. There she was visited by poets and writers, such as Anna Akhmatova, Ilia Ehrenburg, and Osip Mandelstam, choreographer Bronislava Nijinska and dancer Elsa Kruger, as well as many artists Alexander Bogomazov, Wladimir Baranoff-Rossine, and students, such as Grigori Kozintsev, Sergei Yutkevich, Aleksei Kapler and Abraham Mintchine among many others. In 1908, she participated in an exhibition together with members of the group Zveno (Link) organized by David Burliuk, Vladimir Burliuk and others in Kiev.

Paris

In Paris, Aleksandra Ekster became personally acquainted with Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, who introduced her to Gertrude Stein.

Under the name Alexandra d’Exter she exhibited six works at the Salon de la Section d’Or, Galerie La Boétie, Paris, October 1912, with Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp and others.

In 1914, Exter participated in the Salon des Indépendants exhibitions in Paris, together with Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Archipenko, Vadym Meller, Sonia Delaunay-Terk and other French and Russian artists. In that same year, she participated with the “Russians” Archipenko, Koulbine and Rozanova in the International Futurist Exhibition in Rome. In 1915, she joined the group of avant-garde artists Supremus. Her friend introduced her to the poet Apollinaire, who took her to Picasso’s workshop. According to Moscow Chamber Theatre actress Alice Coonen, “In [Ekster’s] Parisian household there was a conspicuous peculiar combination of European culture with Ukrainian life. On the walls between Picasso and Braque paintings, there was Ukrainian embroidery; on the floor was a Ukrainian carpet, at the table they served clay pots, colorful majolica plates of dumplings.”

Russian avant-garde

Under the avant-garde umbrella, Ekster has been noted to be a suprematist and constructivist painter as well as a major influencer of the Art Deco movement.

While not confined within a particular movement, Ekster was one of the most experimental women of the avant-garde. Ekster absorbed from many sources and cultures in order to develop her own original style. In 1915-1916, she worked in the peasant craft cooperatives in the villages Skoptsi and Verbovka along with Kazimir Malevich, Yevgenia Pribylskaya, Natalia Davidova, Nina Genke, Liubov Popova, Ivan Puni, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova and others. Ekster later founded a teaching and production workshop (MDI) in Kiev (1918-1920). Alexander Tyshler, Vadym Meller, Anatol Petrytsky, Kliment Red’ko, Tchelitchew, Shifrin, Nikritin worked there. Also during this period she was one of the leading stage designers of Alexander Tairov’s Chamber Theatre.

In 1919, together with other avant-garde artists Kliment Red’ko and Nina Genke-Meller, she decorated the streets and squares of Kiev and Odessa in abstract style for Revolution Festivities. She worked with Vadym Meller as a costume designer in a ballet studio of the dancer Bronislava Nijinska.

In 1921, she became a director of the elementary course Color at the Higher Artistic-Technical Workshop (VKhUTEMAS) in Moscow, a position she held until 1924. Her work was displayed alongside that of other Constructivist artists at the 5×5=25 exhibition held in Moscow in 1921.

In the spring of 1924, Alexandra Exter travelled to Venice to take part in organising the 14th Venice Biennale. Most of the Ekster’s works were not exposed, but were part of the exhiibition catalogue. Yet, she also created a special painting inspired by Venice at the entrance hall on the second floor of the Soviet Pavilion. Several researches for this painting are now in international and private collections.

Revolutionising costume design

In line with her eclectic avant-garde-like style, Ekster’s early paintings strongly influenced her costume design as well as her book illustrations, which are scarcely noted. All of Ekster’s works, no matter the medium, stick to her distinct style. Her works are vibrant, playful, dramatic, and theatrical in composition, subject matter, and color. Ekster constantly stayed true to her composition aesthetic across all mediums. Furthermore, each medium only enhanced and influenced her work in other mediums.

With her assimilation of many different genres her essential futurist and cubist ideas was always in tandem with her attention to colour and rhythm. Ekster uses many elements of geometric compositions, which reinforce the core intentions of dynamism, vibrant contrasts, and free brushwork. Ekster stretched the dynamic intentions of her work across all mediums. Ekster’s theatrical works such as sculptures, costume design, set design, and decorations for the revolutionary festivals, strongly reflect her work with geometric elements and vibrant intentions.

Through her costume work, she experimented with the transparency, movement, and vibrancy of fabrics. Ekster’s movement of her brushstroke in her artwork is reflected in the movement of the fabric in her costumes. Ekster’s theatrical sets used multi-coloured dimensions and experimented with spatial structures. She continued with these experimental tendencies in her later puppet designs. With her experimentation across many mediums, Ekster started to take the concept of her costume designing and integrate it into everyday life. In 1921, Ekster’s work in fashion design began. Though her mass production designs were wearable, most of her fashion design was highly decorative and innovative, usually falling under the category of haute couture.

In 1923, she continued her work in many media in addition to collaborating with Vera Mukhina and Boris Gladkov in Moscow on the decor of the All Russian Exhibition pavilions.

Ukrainian folk influences

Thanks to the connections of her husband, Mykola Ekster, Aleksandra met Natalia Davydova, who had an estate with craftsmanship in Verbivtsi near Cherkasy. It was there that the artist, who is now considered a representative of European Cubism, Futurism, Ukrainian avant-garde, one of the founders of the Art Deco style, discovered Ukrainian folk art, that was one of the influences in her works. According to Georgy Kovalenko, a researcher of Aleksandra Ekster’s work, the time in Verbivka was the determining factor in the artist’s painting, her colourful poem and became a source of imagery: “She conducted real scientific expeditions in search of ancient peasant embroideries, liturgical sewing, and weaving items,” Kovalenko wrote in his monograph.

Ekster and Davydova with other researchers searched for folk motifs, reinterpreted them, modernized them and, together with Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavska, drew supremacist designs for embroideries on bags, pillows, carpets, and belts. Later, they created the Kiev handicraft society, and also presented embroideries from Verbivtsi at exhibitions in Kiev and European countries. In 1917, more than 400 works were exhibited in Moscow, from where they never returned.

Text from the Wikipedia website

El Lissitzky (Russian born Ukraine, 1890-1941)

Composition

1918-1920s

Oil on canvas

71 x 58 cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

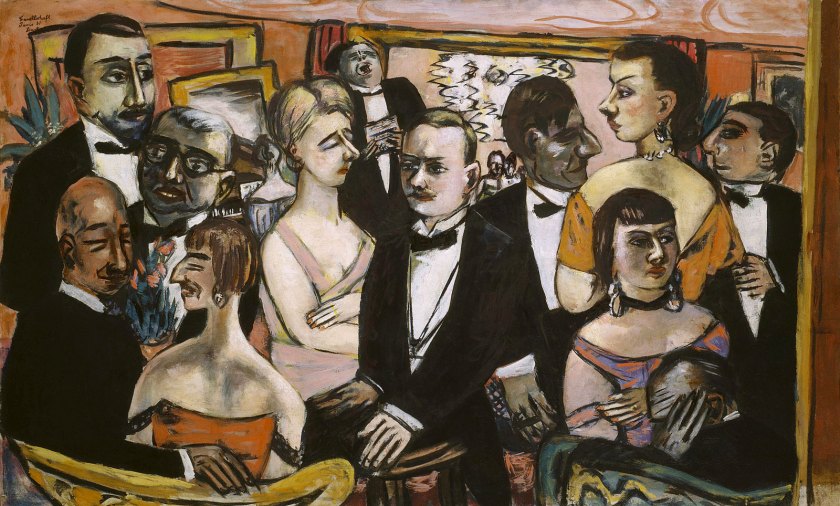

Theatre Design

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing the work of Vadym Meller

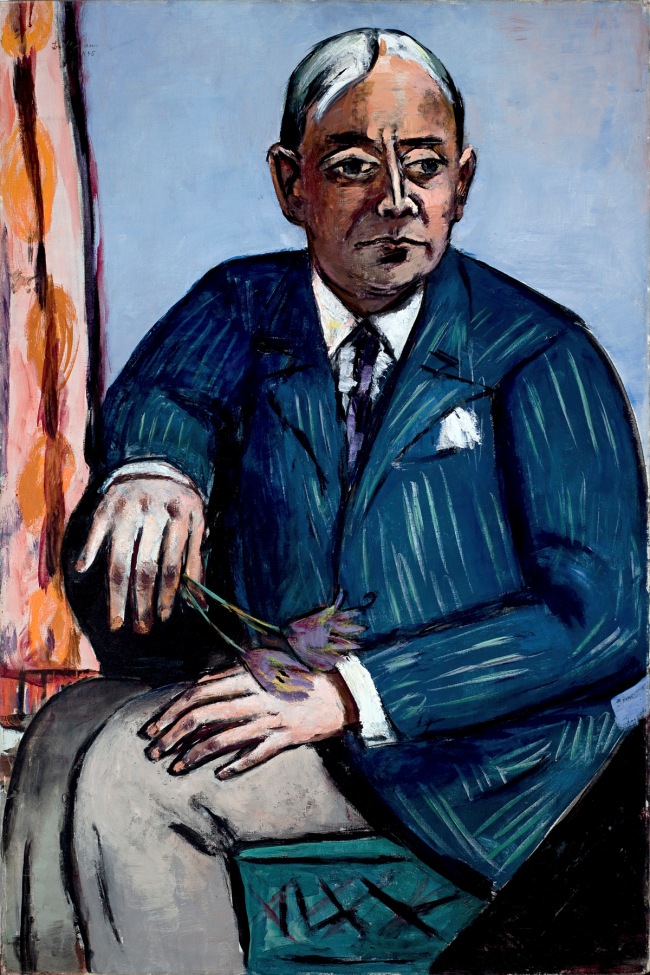

Vadym Meller (Ukrainian, 1884-1962)

Sketch for choreographic movement “Masks” for Bronislava Nijinska’s School of Movements, Kyiv

1919

Watercolour on cardboard

60 x 43cm

Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine

Vadym Meller or Vadim Meller, (Russian: Вадим Георгиевич Меллер; Ukrainian: Вадим Георгійович Меллер, 1884-1962) was a Ukrainian Soviet painter, avant-garde Cubist, Constructivist and Expressionist artist, theatrical designer, book illustrator, and architect. In 1925 he was awarded a gold medal for the scenic design of the Berezil’ theater in the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes (Art Deco) in Paris. …

V. Meller became the leader of the Constructivism movement in Ukrainian theatre design. He worked in the National theatre as a chief artist until 1945. From 1925 onward, he also taught at the Kyiv Art Institute (KKHI) together with Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Bogomazov. Also in 1925, V. Meller became a member of the artists union Association of the Revolutionary Masters of Ukraine together with David Burliuk (co-founder), Alexander Bogomazov (co-founder), Vasiliy Yermilov, Victor Palmov, and Khvostenko-Khvostov.

Text from the Wikipedia website

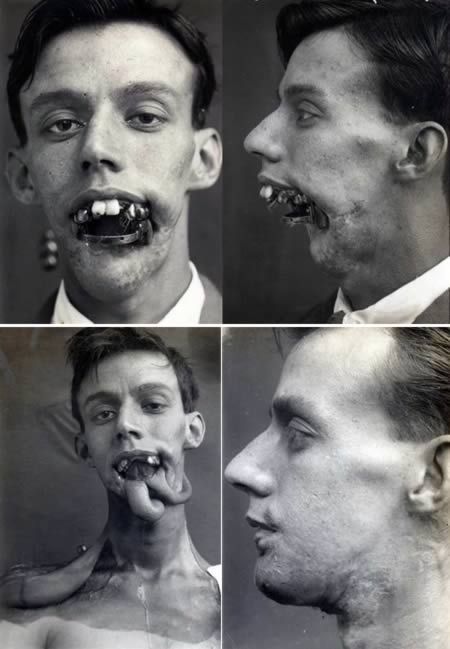

The exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s presents the ground-breaking art produced in Ukraine in the first decades of the 20th century, showcasing trends that range from figurative art to futurism and constructivism. The development of Ukrainian modernism took place against a complicated socio-political backdrop of collapsing empires, the First World War, the revolutions of 1917 with the ensuing Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921), and the eventual creation of Soviet Ukraine. The ruthless Stalinist repressions against Ukrainian intelligentsia led to the execution of dozens of writers, theatre directors and artists, while the Holodomor, the man-made famine of 1932-1933, killed millions of Ukrainians.

Despite these tragic circumstances, Ukrainian art of the period lived through a true renaissance of creative experimentation. In the Eye of the Storm reclaims this essential – though little-known in the West – chapter of European modernism, displaying around 70 works in a full range of media, from oil paintings and sketches to collages and theatre designs. Following a strict chronological order, the show presents works by masters of Ukrainian modernism, such as Oleksandr Bohomazov, Vasyl Yermilov, Viktor Palmov, and Anatol Petrytskyi. Exploring the polyphony of styles and identities, the exhibition includes neo-Byzantine paintings by the followers of Mykhailo Boichuk and experimental works by members of the Kultur Lige, who sought to promote their vision of contemporary Ukrainian and Yiddish art, respectively. It features pieces by Kazymyr Malevych and El Lissitzky, quintessential artists of the international avant-garde who worked in Ukraine and left a significant imprint on the development of the national art scene. The exhibition also showcases artworks of internationally renowned artists who were born and started their careers in Ukraine but became famous abroad, among them Alexandra Exter, Wladimir Baranoff-Rossiné, and Sonia Delaunay.

In the most comprehensive survey of Ukrainian modern art to date, with many works on loan from the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the State Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine, the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza celebrates the dynamism and diversity of the artistic scene in Ukraine, while safeguarding the country’s heritage during the inadmissible, present-day occupation of its territory by Russia. After its presentation in Madrid, the exhibition will travel to the Museum Ludwig in Cologne.

Acknowledgements

This exhibition has been made possible by the support of President Zelensky and the Office of the President of Ukraine. Also key is Oleksandr Tkachenko, the Ukrainian Minister of Culture, whose collaboration has enabled us to secure the exceptional loan of these works from a war-torn country.

We extend our gratitude to the National Art Museum of Ukraine and the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine for their generous loans, as well as to the private collectors who have collaborated.

Special thanks are due to Baroness Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, a member of the Board of Trustees of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, who has passionately and courageously promoted the project from the outset and facilitated the complex negotiations to bring these works to Spain.

The support of the PinchukArtCentre has also been notable.

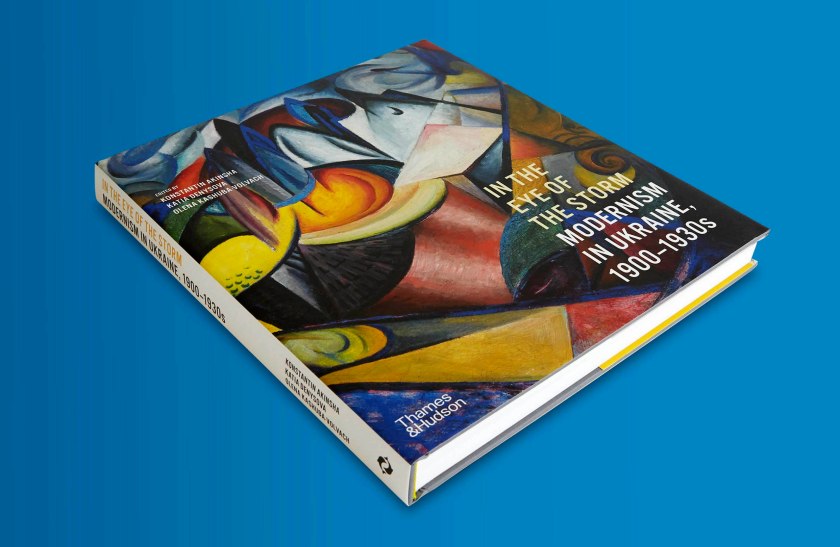

Mention should likewise be made of the work and dedication of the curators Konstantin Akinsha, Katia Denysova and Olena Kashuba-Volvach and their revealing essays that appear, together with those of other research scholars, in the magnificent edition published by Thames & Hudson.

This exhibition has been made a reality thanks to the support of Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza, Museums for Ukraine, the Deputy Directorate-General for State Museums of the Directorate-General for Cultural Heritage and Fine Arts (Spanish Ministry of Culture and Sport), Mastercard, Omega Capital, SITspain and Hammam Al-Andalus, among others.

Text from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum website

Spotify playlist In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s

Katia Denysova, curator of the exhibition, selects a list of recent hits, contemporary classics and the carol “Carol of the Bells”, inspired by a Ukrainian folk song.

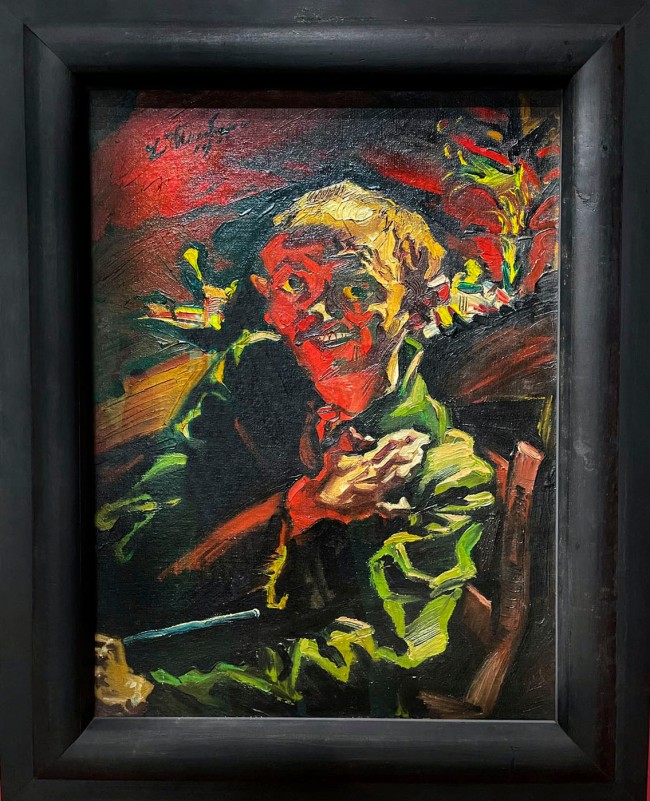

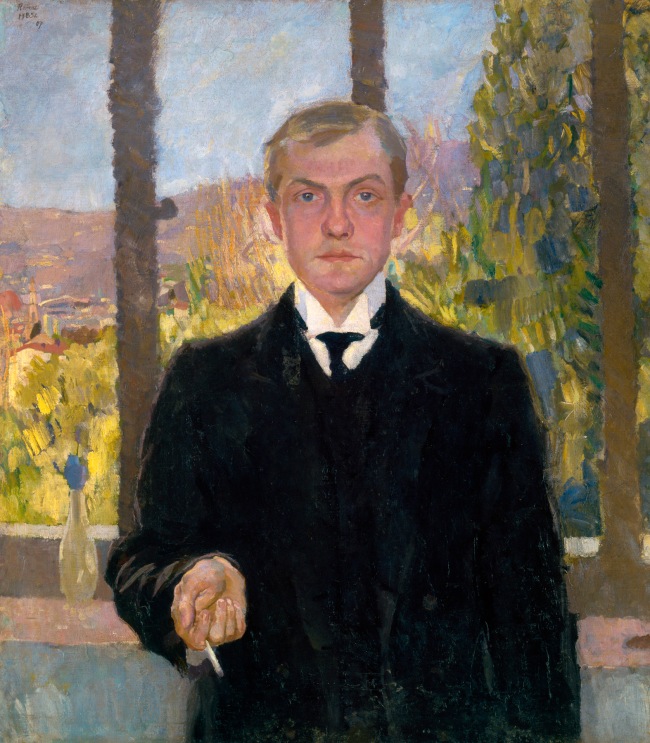

Davyd Burliuk (Ukrainian, 1882-1967)

Carousel

1921

Oil on canvas

33 x 45.5cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

David Burliuk devoted his artistic practice – which spanned painting, poetry, drawing, and engraving – to the pursuit of the modern. Using bold typefaces, vibrant colors, and energetic brush strokes, Burliuk turned against the artistic conventions of the past, capturing Russian Futurism’s ideas of dynamism, innovation, and revolution, declared in the 1912 manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. Burliuk and his Futurist compatriots challenged audiences to question the accepted ideals of aesthetics and beauty in the hope of developing a new and more forward-thinking world.1

Artists, like Burliuk, associated with Russian Futurism sought to both question and analyze – what they called “deconstruct” – established principles of art, including a classical attention to realism, balance, and natural subject matter. Explaining his methods, Burliuk wrote:

“deconstruction is the opposite of construction.

a canon can be constructive.

a canon can be deconstructive.

construction can be shifted or displaced.”2

David Burliuk was born on January 21, 1882, in the Village of Riabushky in the Russian Empire, in what is now Ukraine. He exhibited an early affinity for creative art, beginning independent painting studies at the age of 10. By the end of the 19th century, Burliuk had enrolled in the Royal Academy of Art in Munich, the first of four formal arts programs he would attend throughout his life. It was at the Moscow Academy of Fine Art, an institution in which Burliuk enrolled in 1910, that he began participating in exhibitions and collectives that questioned the conventional standards of beauty in art. During a time of significant industrialization and political change, movements such as the famed Der Blaue Reiter, a group Burliuk associated with in 1912, while he was in Munich, emphasized a shift away from the classical styles of the past, prioritizing the innovations of the future.

Between 1910 and 1913, Burliuk began to assemble artists and poets – including Vladimir Mayakovsky, Benedict Livshits, and Velimir Khlebnikov – to form a group that would become known as Gileia. Initially formed as a modern literary collective and founded on the principles proposed by Filippo Tomasso Marinetti‘s “Manifesto of Futurism,” Gileia and its members would quickly metamorphose into the Cubo-Futurists. Marked by graphic handling of subjects and unconventional editorial displays, the Cubo-Futurists were unwavering in pushing the boundaries of accepted aesthetics.

The Cubo-Futurist movement carved out a space for artists to explore the creative possibilities of the modern future that lay ahead. Unfortunately, by 1916 the First World War had taken its toll on the creative communities of Eastern Europe, and the group dissolved. Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, political conflict forced many to search for safer havens, and in 1922 Burliuk settled in the United States. He continued creating works consistent with the style of Cubo-Futurism, now informed by the trauma and displacement of war.

Distressed by the turmoil in his homeland, Burliuk joined other displaced artists, including Alexander Bogomazov and Vadym Meller, in creating the New York-based Association of Revolutionary Masters of Ukraine in 1925. While continuing his artistic practice, he would spend much of his later life attempting to revisit his homeland, a pursuit that proved successful in 1956, when his petition to visit was granted by the Soviet government. David Burliuk passed away on January 15, 1967. His art is a testament to constant innovation and, as he wrote in a 1912 manifesto, “the new impending beauty of the self-valuable (self-creating) word.”

Emily Olek, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Drawings and Prints, 2022. “Deconstruction is the opposite of construction,” on the MoMA website 2022 [Online] Cited 24/03/2023.

1/ Margit Rowell, Deborah Wye, and Jared Ash. The Russian Avant-Garde Book 1910-1934. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2002), p. 25.

2/ David Burliuk, “Cubism,” in John E. Bowlt, ed., Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934 (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1988), p. 76.

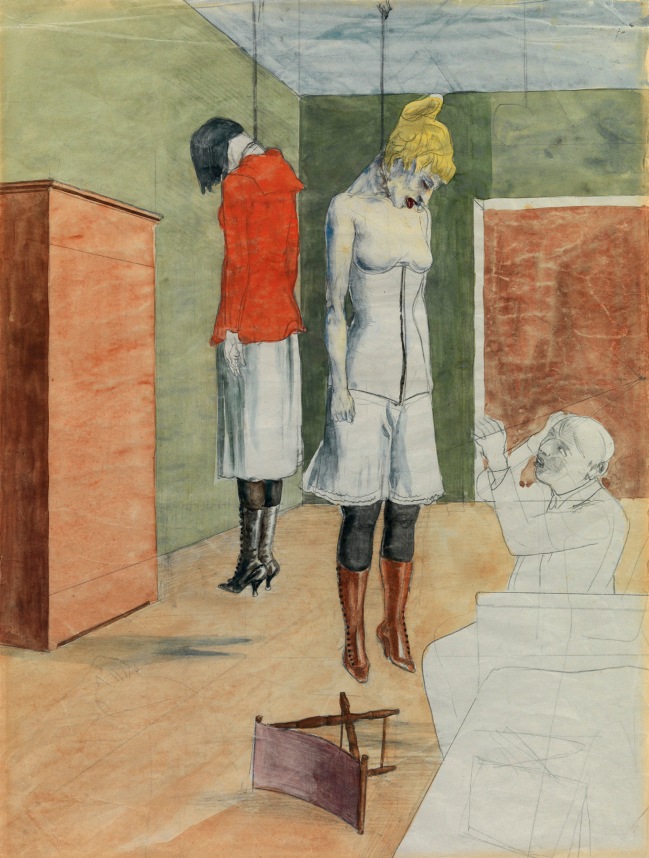

Mykhailo Boichuk (Ukrainian, 1882-1937)

Dairy Maid

1922-1923

Tempera on canvas

95 x 45cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Born in the region of Ternopil in Western Ukraine, Boichuk was educated in Krakiv, Munich, and Paris. It was in Paris that he established his first art school and where his “Neo-Byzantine” style gained critical acclaim. Later, Boichuk became a leading artist and art educator in 1920s Ukraine. However, he and his followers, called “Boichukists,” were brutally persecuted by the Soviet regime. Many of them, including Boichuk himself, were executed by the Soviet police in the 1930s, and most of their artworks were destroyed. In spite of this, the style of Boichukism became very influential in the twentieth-century Ukrainian art.

Anonymous. “‘Eye on Culture’: Mykhailo Boichuk (and Manuil Shekhtman) and the “Boichukist” Tradition in Painting,” on the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter website April 30th, 2020 [Online] Cited 23/03/2023

Boychuk was born in Romanivka, then in Austria-Hungary, and currently in Ternopil Oblast of Ukraine. He studied painting under Yulian Pankevych in Lviv, and subsequently in Kraków, where he graduated from the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts in 1905. He also studied at fine arts academies in Vienna and Munich. In 1905, he had his work exhibited at the Latour Gallery in Lviv and in 1907, his work was exhibited in Munich. Between 1907 and 1910 he lived in Paris where, in 1909, he founded his own studio-school. In this period, he worked with and was influenced by Félix Vallotton, Paul Sérusier and Maurice Denis. He held an exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants in 1910, featuring his and his students’ works on the revival of Byzantine art. The group of Ukrainian artists who studied and worked with him was known as the Boychukists. In 1910, Boychuk returned to Lviv, where he worked as a conservator at the National Museum. In 1911, he travelled to the Russian Empire, but, after World War I started, he was interned there as an Austrian citizen. After the war, Boychuk remained in Kyiv.

In 1917, he became one of the founders of the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts, where he taught fresco and mosaic, and in 1920 was a rector. In 1925, he co-founded the Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine. At the time, he already performed a number of high-profile monumental works, and formed a school of monumental painters which existed until his death. The school included renowned artists such as his brother Tymofiy Boychuk and Ivan Padalka.

Due to the Great Purge, the Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine was disestablished, and Boychuk was executed. His wife, Sofiia Nalepinska, also an artist, was executed several months after Boychuk.

Many of the works by Boychuk, which mainly involved frescoes and mosaics, were destroyed after he was executed. Even his paintings which were kept in museums of Lviv, were destroyed after World War II. The main projects carried out or coordinated by Boychuk and his school – which included his brother Tymofii Boichuk, Ivan Padalka, Vasyl Sedliar, Sofiia Nalepinska, Mykola Kasperovych, Oksana Pavlenko, Antonina Ivanova, Mykola Rokytsky, Kateryna Borodina, Oleksandr Myzin, Kyrylo Hvozdyk, Pavlo Ivanchenko, Serhii Kolos, Okhrym Kravchenko, Hryhorii Dovzhenko, Onufrii Biziukov, Mariia Kotliarevska, Ivan Lypkivsky, Vira Bura-Matsapura, Yaroslava Muzyka, Oleksandr Ruban, Olena Sakhnovska, Manuil Shekhtman, Mariia Trubetska, Kostiantyn Yeleva, and Mariia Yunak – are an important contribution to Ukrainian and world art.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at right, the work of Anatol Petrytskyi including the painting Disabled (1924, below)

Ukrainian artists at the Venice Biennale

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at left, Anatol Petrytskyi’s Disabled (1924, below)

Anatol Petrytskyi (Ukrainian, 1895-1964)

Disabled

1924

Oil on canvas

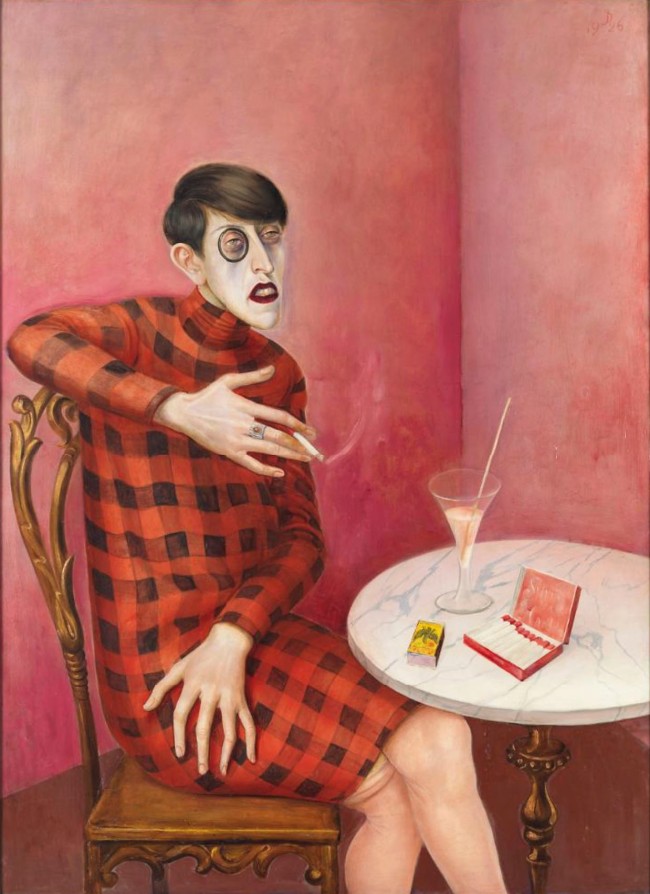

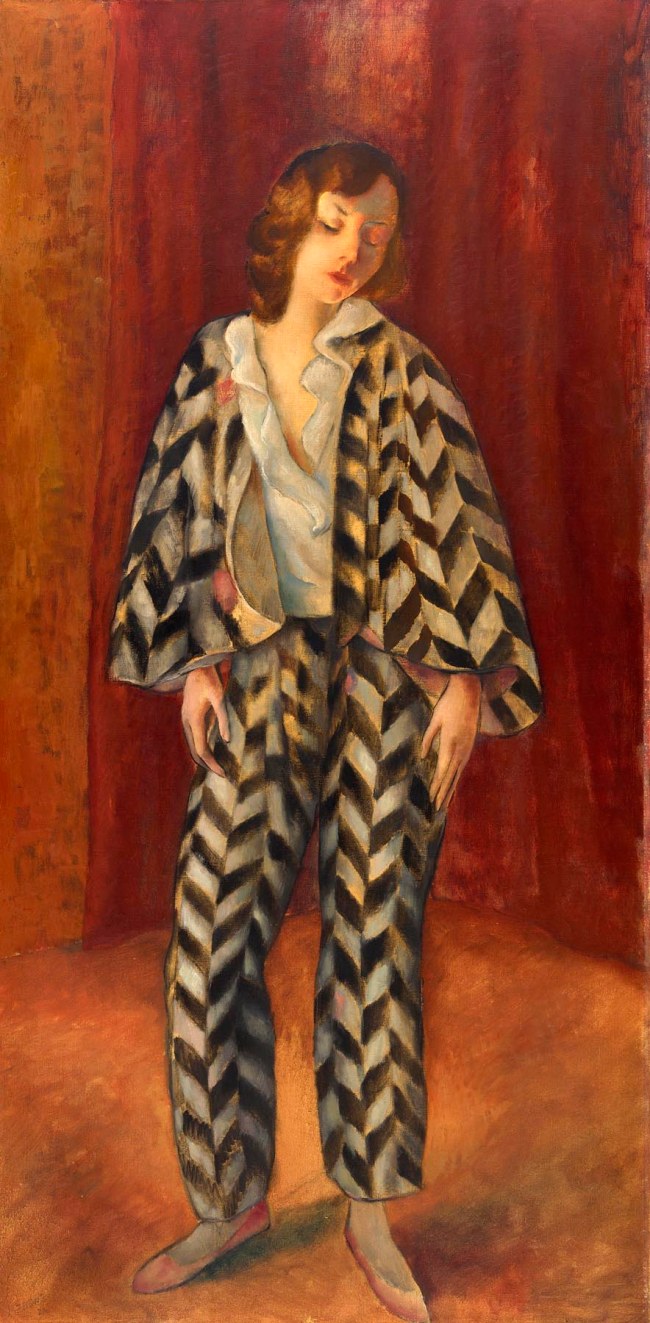

Sonia Delaunay (French born Ukraine, 1885-1979)

Simultaneous Dresses (Three Women, Forms, Colours)

1925

Oil on canvas

146 x 114cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

© Pracusa S.A.

Boichukists

A native of Halychyna in western Ukraine, Mykhalio Boichuk completed his education in art academies of Vienna, Krakow, Munich and Paris. In late 1917, he established a fresco, mosaics and tempera studio at the newly founded Ukrainian Academy of Arts in Kyiv. Advocating for arts as a national treasure and not a mere commodity, Boichuk arrived at a synthesis of styles, drawing on Byzantine art, Italian pre-Renaissance frescoes and Ukrainian folk art. In the earl Soviety period, his studio emerged as a school of monumental art, with its students, henceforth known as Boichukists, completing numerous state commissions for public spaces and buildings. The collaboration proved short-lived, however: labelled ‘bourgeois nationalists’, Boichuk and a close circle of his associates were executed during the Stalinist purge of the 1930s, with most of their public art subsequently destroyed.

Exhibition wall text

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at centre in the top image and at right in the bottom image, Manuil Shekhtman’s Jewish Pogrom 1926 (below)

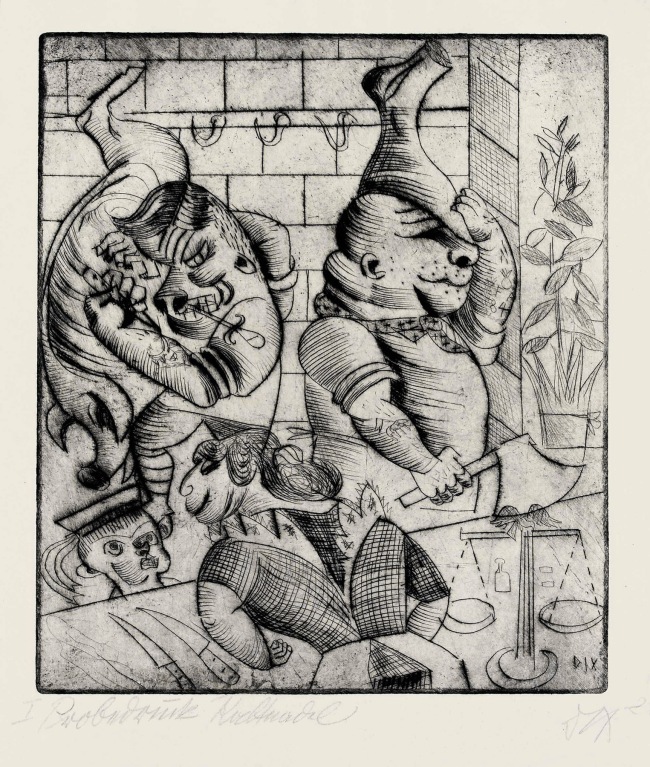

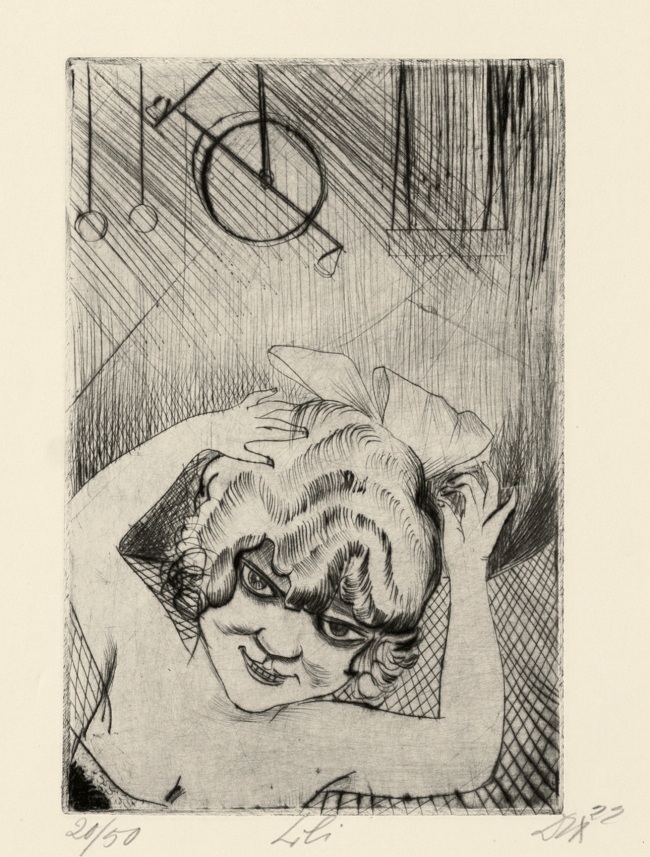

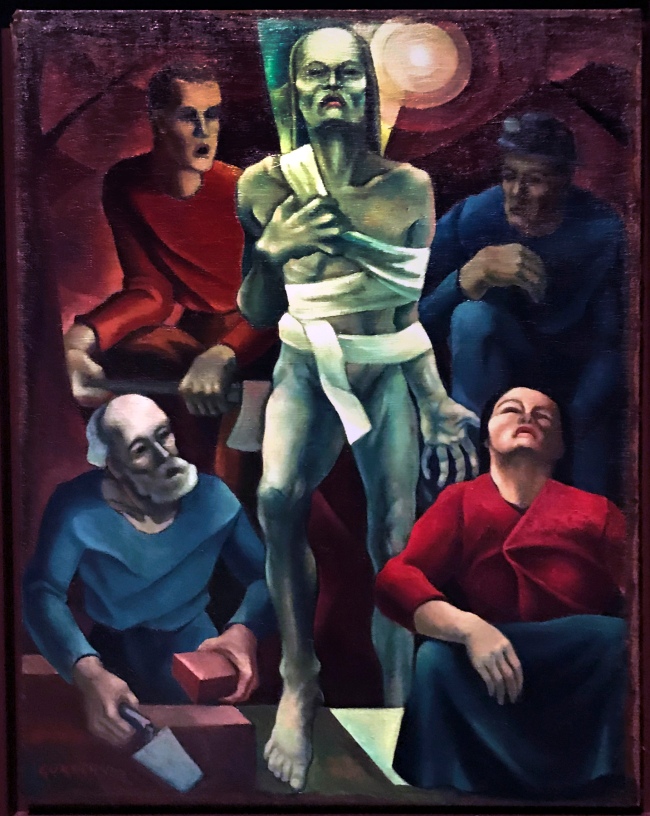

Manuil Shekhtman (Ukrainian, 1900-1941)

Jewish Pogrom

1926

Tempera on canvas

198 x 160cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

The artist Emmanul Shekhtman was born in 1900 in the village of Lipniki in the Volyn Province (now Zhitomir Region, Ukraine). Manuil spent his childhood with his grandfather in the town of Norinsk, where he studied at a heder (traditional Jewish elementary school). The children of the family grew up in an artistic atmosphere. His sister Malka was a poet who wrote in Hebrew under the pseudonym M. Bat-Khama (“Daughter of the Sun”). She would later work as assistant director at the Kiev State Jewish (i.e. Yiddish) Theater.

In 1913, Shekhtman entered the Kiev Art School, finishing it in 1920. In his youth, Emmanuel was an ardent Zionist and member of a youth movement. During that period, he collaborated with the Kiev branch of the Tarbut organization, while working on stage sets at the Hebrew-language Omanut theater studio. In 1922, Shekhtman entered the Kiev Art Institute to study under the primary ideologue of Ukrainian national art, Mikhail Boichuk. After graduating from the Institute in 1926, Shekhtman continued to actively cooperate with Jewish cultural organisations. From 1925 to 1927, he taught drawing at a Jewish orphanage in Kiev. In 1928, he served as head of the theatrical production of the Kiev State Jewish Theater. In the following year, Shekhtman became head of the artistic division of the Odessa Museum of Jewish Culture. In the early 1930s, there was a campaign of repression against Ukrainian avant-garde artists, which singled out Mikhail Boichuk and his present and past students – including Shekhtman, who was fired from all posts. Those years saw a shift in the country’s official policy, with the authorities beginning to cultivate a sense of Soviet patriotism, with an emphasis of the Russian historical past. In 1934, Shekhtman moved to Moscow. At first, he could find no employment, and was aided by former students who secured one-time commissions for him. Later, he was able to find work at the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition (VSKhV), for which he organized celebrations and served as a landscape architect. Subsequently, he was accepted as a member into the Moscow division of the Union of Soviet Artists.

Jewish themes were central to Shekhtman’s art. Two of his main works, “Those Who Suffered from Pogroms” (1926) and “The Resettlers” (1929), were part of a series entitled “My Biographical Particulars”. Another series of graphics by him, titled “Exile” or “Exodus” (1939-1941), exudes a sense of impending catastrophe for his people.

Following the outbreak of the Soviet-German war in late June 1941, Emmanuil Shekhtman was assigned to camouflaging military targets in Moscow. He later volunteered for frontline duty. In August 1941, he fought with a division of the Moscow People’s Militia. Subsequently, he was transferred to a separate battalion of sappers. In November 1941, he went missing in action in the area of Dmitrov (Moscow Region).

Anonymous. “Emmanul Shekhtman,” on the Yad Vashem website Nd [Online] Cited 24/03/2023

Ivan Padalka (Ukrainian, 1894-1937)

Photographer

1927

Tempera on paper

33.5 x 45cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Ivan Padalka (1894-1937) was a Ukrainian painter, art professor and author who was shot during the Great Terror. Representative of the generation of the Executed Renaissance and the Boychukism movement (a cultural and artistic phenomenon in the history of Ukrainian art between the 1910s and 1930s, distinguished by its artistic monumental-synthetic style. It was an original school of Ukrainian art, formed by a synthesis of Ukrainian folk art and the church art of Byzantium, Proto-Renaissance and Ukraine. The name comes from the name of the founder of the movement: Mykhailo Boychuk.

Ivan Ivanovych Padalka (Ukrainian: Івaн Івaнович Пaдалка: 15 November 1894, Zhornoklyovy, currently Cherkasy Raion – 13 July 1937, Kiev) was a Ukrainian painter, art professor and author who was shot during the Great Terror. …

He was one of eight children born to a farming family of modest means. He began his education at the local parish school, where he first displayed a talent for art. His abilities were noticed by a local nobleman, who helped him to finance studies at the State Ceramics Vocational School in Myrhorod with Opanas Slastion. His work was often held up as a model for the class. He worked there until 1913, when he was excluded for organising revolutionary activities.

He then went to Poltava and found a position at the Ethnographic Museum [uk], where they made copies of Ukrainian carpet designs for a weaving workshop in Kiev owned by Bogdan Khanenko, who was a major patron of the arts. His earnings enabled him to enrol at the short-lived Kiev Art School. His works were regularly exhibited there, and he began to illustrate children’s books.

In 1917, after finishing his studies there, he transferred to the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts, where he became a student in the workshop of Mykhailo Boychuk. While there, he was largely involved in decorative work for buildings, designing posters and creating various revolutionary materials for public display. He also received a commission from the State Publishing House to illustrate a collection of children’s stories called Барвінок (Periwinkles). He worked on that project together with Boychuk’s younger brother Tymofiy.

After graduating in 1920, he returned to Myrhorod and became a teacher at his former ceramics school. Later, he taught the same subject at a technical school in Kiev. His proficiency in his chosen specialty was widely recognised, so he was able to secure a position at the Kharkiv Art and Industrial Institute [uk], where he worked from 1925 to 1934. That year, he returned to Kiev to accept an appointment as a Professor at the State Academy.

In 1936, he was arrested and tortured by the NKVD on charges of counterrevolutionary activities, related to his Ukrainian nationalism. In July, the following year, he was executed by firing squad, together with his former mentor and friend, Boychuk, and the painter Vasily Sedlyar. He was posthomously “rehabilitated” in 1958.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Vasyl Yermilov (Ukrainian, 1894-1967)

Nove Mystetstvo ([New Art], magazine cover design)

c. 1927

Indian ink and gouache on paper

36 x 23.9cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Yermilov, Vasyl [Єрмілов, Василь; Jermilov, Vasyl’] (Ermilov, Vasilii), b 22 March 1894 in Kharkiv, d 4 December 1967 in Kharkiv. Painter and graphic designer. He studied at the Art Trade School Workshop of Decorative Painting in Kharkiv (1905-1909), the Kharkiv Art School (1910-1911), and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1912-1913). In 1918 he joined the avant-garde Union of Seven group in Kharkiv and designed the script for its album Sem’ plius tri (Seven Plus Three, 1918). Under Soviet rule Yermilov designed posters, ‘agit-trains’, street decorations, billboards, the interiors of public buildings (eg, the murals in the foyer of the Kharkiv Circus and the Red Army Club in Kharkiv), theatrical sets, displays, packaging, and journal and book covers; he also directed the art department of the All-Ukrainian Bureau of the Russian Telegraph Agency (1920-1921) and taught at the Kharkiv Art Tekhnikum (1921-1922) and Kharkiv Art Institute (1922-1935). He received several international prizes for his graphic designs, including a gold medal at the 1922 Leipzig International Graphics Exhibition and an award at the 1928 Köln International Press Exhibition. While a member of the Avanhard (Avant-garde) group (1926-1929) he was graphic designer of its newspaper Doba konstruktsiï, its journal Mystets’ki materiialy Avanhardu, and, with Valeriian Polishchuk, the three issues of Biuleten’ Avanhardu. From 1927 he was also a member of the Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine. Yermilov’s synthesis of formalist esthetics, folk designs, and traditional painting methods (including egg tempera) was an important contribution to the development of Ukrainian design of the 1920s. His distinctive style of constructivist collage and typographic design, called constructive-dynamism or spiralism, developed distinctly and in parallel with Russian constructivism. Because of his formalist interests Yermilov was forced out of the Soviet art arena in the late 1930s. In the last years of his life he taught at the Kharkiv Industrial Design Institute (1963-1937). A book about him by Z. Fogel was published in Moscow in 1975. A retrospective exhibition of Yermilov’s works was organised in Kyiv in 2011 and a monograph about his life and art, Vasyl Yermilov zhde vesnu (Vasyl Yermilov Awaits the Coming of Spring), by Tetiana Pavlova was published in Kyiv in 2012.

Anonymous. “Yermilov, Vasyl,” on the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine website Nd [Online] Cited 24/03/2023

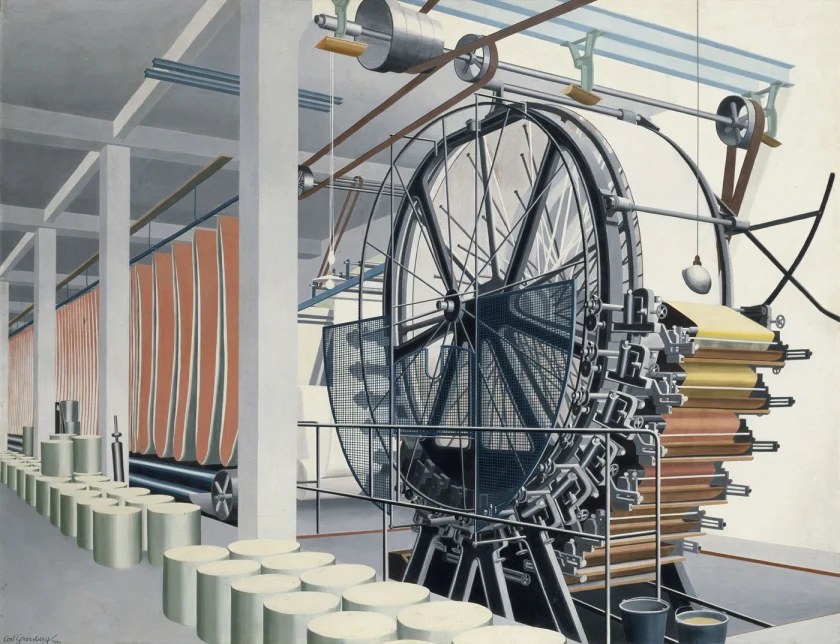

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at right, Oleksandr Bohomazov’s Sharpening the Saws 1927 (below)

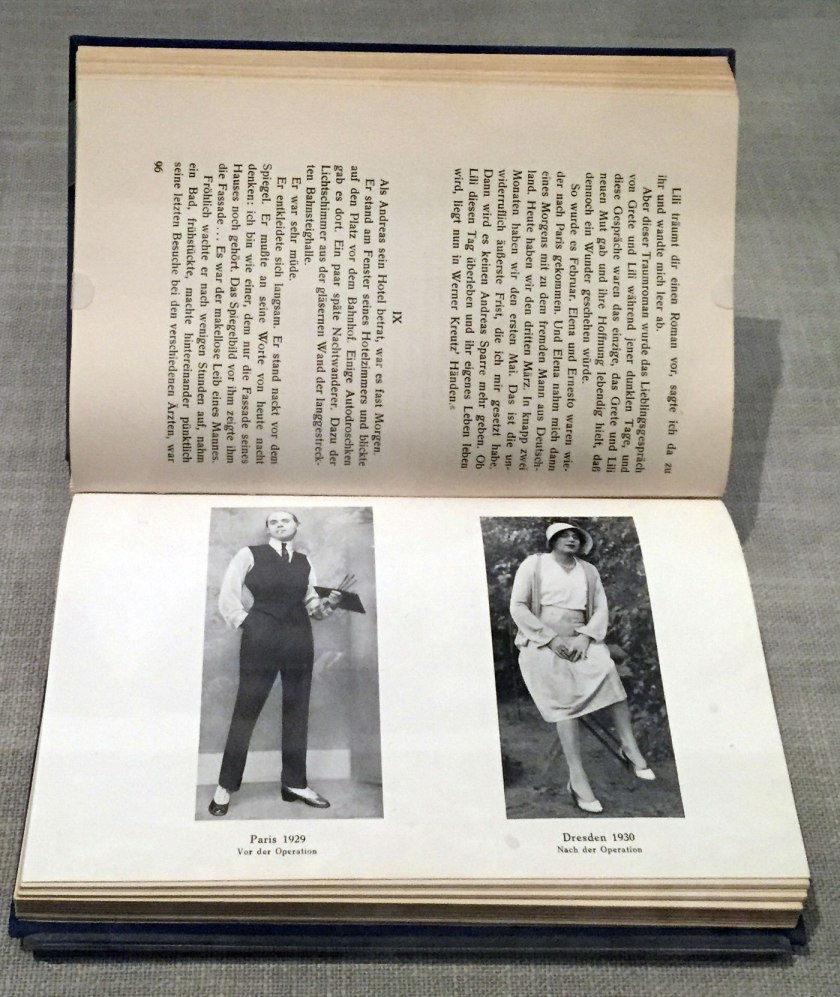

Oleksandr Bohomazov (Ukrainian, 1880-1930)

Sharpening the Saws

1927

Oil on canvas

138 x 155cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

In the summer of 1930, Bohomazov’s painting The Woodcutters was exhibited in the Soviet pavilion of the 17th Venice Biennale. At that time, the USSR’s participation in the biennale had become quite politicized: Russian ideologists viewed exhibitions as a vector of propaganda activities. However, young Soviet art was still relatively free from state censorship. So, together with Bohomazov other Ukrainian avant-garde artists saw their artwork make it to Venice – artists like Anatole Petrytsky, Ivan Padalka, Vasyl Sedlyar, and Sofia Nalepynska-Boychuk. The latter three would be executed seven years later under the trumped up charges of “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism and leading a national-fascist terrorist organization.”

At the time, Bohomazov had already been working as a professor of easel painting at Kyiv Art Institute for eight years (founded as the Ukrainian Academy of Arts in 1917), and participation in the biennale meant his recognition as an artist and a theoretician. Unfortunately, Bohomazov did not live until the biennale opening which had been delayed for five weeks: he died in Kyiv just before it opened.

He created The Work of Woodcutters in 1927-1930 in Boyarka, a dacha condominium. “The clearing was strewn with fresh sawdust, the logs almost rang in the sun, resinous and glistening. The figures of workers on the scaffolding seemed huge against the background of bright blue sky. The high sound of the saw resonated in the air,” remembered Yaroslava, Bohomazov’s daughter. The Work of Woodcutters triptych includes two paintings: The Woodcutters (1929) and Sharpening Saws (1927); the third one to be titled Rolling Logs remained only an idea, reproduced in many sketches and watercolours.

Bohomazov resumed easel painting after a long pause due brought on by his grave emotional state following the death of his father-in-law, revolutionary perturbations, and tuberculosis. Obviously feeling that the end was near, Bohomazov put all his effort into the development of the triptych defined by its dynamic rhythms and gleaming colours (corresponding to his theoretical concept of the artist engaging with four elements of art). “I have joy from work, sun, warmth, and energy. In my painting, I don’t want to show the necessity, complicated nature and adaptation, but the joy and energy, the call – so that the audience is compelled to work, to feel like a organised part of the whole,” Bohomazov wrote in his notes.

The Woodcutters, a mature masterpiece by Oleksandr Bohomazov, continues to wow audiences all over the world. In 1931, the painting was exhibited in Zurich, and in 1932, in Japan (researchers have yet to uncover in which city the exhibition took place.) The painting was returned to Kyiv damaged. For about 90 years it remained in this state in a closed museum “special fund” where works were sent in late 1930s to be destroyed. At that time, during the fight for pure Soviet art, the avant-garde art was declared to be “formalist”, and work by these artists were banned. Only in 2019 was The Woodcutters exhibited in the National Art Museum of Ukraine – the first time in years at the exhibition “Oleksandr Bohomazov: the creative lab”. Restorers had worked on the painting for three years before releasing it for the exhibit.

For decades it was forbidden to mention the work of world-renowned cubo-futurist artists. Only in late 1960s did Bohomazov’s name resurface from its enforced oblivion. Modest exhibitions were held in Kyiv, and European avant-garde researchers, namely Jean-Claude Marcadé, Jean Chauvelin and Andrei Nakov – turned their attention to Bohomazov. His works became fashionable additions to collections ranging far beyond the Soviet Union. Bohomazov’s works are currently exhibited in the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Guggenheim and MoMA in New York, Ludwig Museums (Germany) as well as in numerous private avant-garde collections.

Anonymous. “Bohomazov Oleksandr,” on the UA View website Nd [Online] Cited 23/03/2023

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing the work of Anatol Petrytskyi

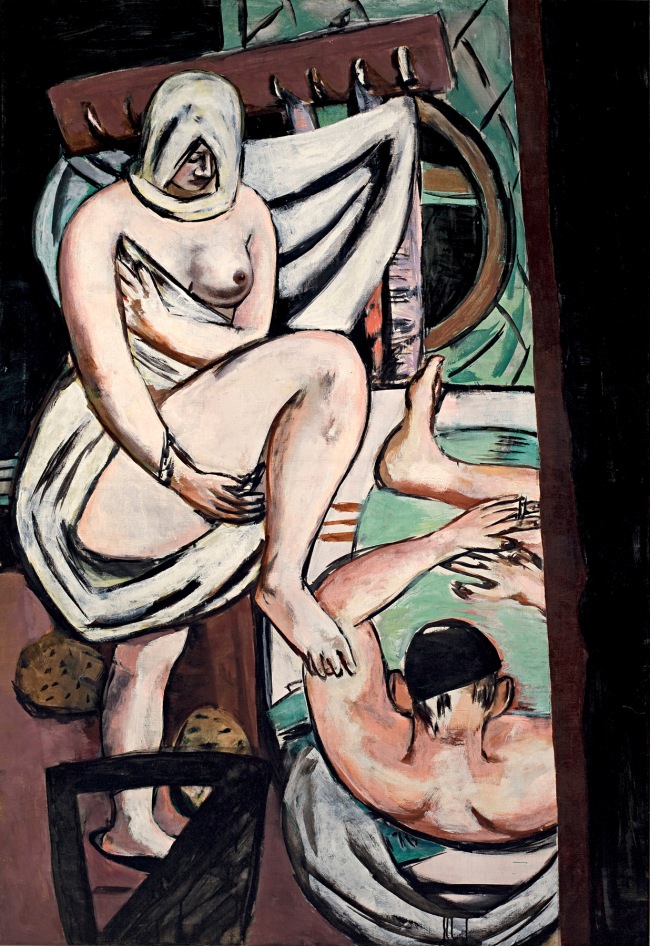

Anatol Petrytskyi (Ukrainian, 1895-1964)

Costume designs for Minister Pinh in the opera ‘Turandot’ at the State Opera Theatre, Kharkiv

1928

Gouache and Indian ink on paper

72 x 54cm

Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine

Anatol Petrytsky (1895-1964) was a Ukrainian painter, stage and book designer. The fate of Anatol Petrytsky (1895-1965), a first-rank artist of the Ukrainian avant-garde of the first third of the twentieth century, reflects the many twists and turns in twentieth-century Ukrainian art as part of the history of Ukraine, its struggle for independence, its defeats and victories. Like his older predecessors who were born in Ukraine at the end of the nineteenth century (Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Exter), he sought to develop his talent in foreign capitals and art centers. He was drawn to the Higher Art and Technical Studios (VKhUTEMAS) in Moscow, where he studied in 1922-1924, and the Bauhaus, whose entrance examination he passed in 1933 but was prevented from attending by the fateful changes in the sociopolitical life of Germany.

However, Petrytsky was already formed as an artist by the 1910s on the solid basis of the then already transformed Kyiv school of painting: the Kyiv Art School, the studios of Aleksandra Exter and Oleksandr Murashko, Mykhailo Boichuk’s monumental painting workshop at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts, and the strong influence of Vasyl Krychevsky and Danylo Shcherbakivsky. He took part in the process of reviving Ukrainian art from his early years. Together with Mykhailo Semenko he blazed the trail for Futurism. Together with Les Kurbas he reformed Ukrainian stage design: he began working on musical productions (Mykola Lysenko’s Taras Bulba, Aleksandr Borodin’s Prince Igor), exploring new avant-garde forms fused into a single undivided whole with the artistic traditions of the professional and folk art of Ukraine. In the 1920s, Petrytsky gained fame at home and abroad primarily as a brilliant avant-garde scenographer. His high status as an artist was confirmed by his highly successful participation in the 17th Venice Biennale (1930), where his large canvas Disabled (1924, above) became the “highlight of the exhibition,” according to art historian Mykhailo Drahan.

Anonymous. “The Ukrainian Avant-garde painter Anatol Petrytsky, 1920s,” on the Cocosse website Nd [Online] Cited 24/03/2023

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at right Viktor Palmov’s The 1st of May 1929 (below)

Kyiv Art Institute

The development of the visual arts in Ukraine in the 1920s-1930s was intimately linked to the Kyiv Art Institute – the successor to the Ukrainian Academy of Art. It was the first institution of higher art education in Ukraine, founded when the country proclaimed independence in 1917. In 1924, in consonance with the ideological tasks of the Soviet regime, the Academy was transformed into an Institute in order to bring educational methods in line with such trends in contemporary art as production design. To create more dynamic curriculum, the Institute signed on new instructors from across the Soviet Union with many prominent avant-garde artists, such as Kazymyr Malevich and Vladimir Tatlin, joining the Faculty.

Exhibition wall text

Viktor Palmov (Ukrainian born Russia, 1888-1929)

The 1st of May

1929

Oil on canvas

161 x 161cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Victor Nikolaevich Palmov (Ukrainian: Віктор Никандрович Пальмов) (10 October 1888 – 7 June 1929) was a Ukrainian painter of Russian origin and avant-garde artist (Futurist and Neo-primitivist) from the David Burliuk circle.

A famous artist (painter and graphic artist), art theorist, talented teacher, a prominent figure in the cultural process of the first quarter of the 20th century. Viktor Palmov is rightly considered a classic of the Ukrainian avant-garde. The artist developed his theory of “colorization” and was the author of several articles on the problems of the theory of new painting, published in the magazine “New Generation”. The master’s works were among those “arrested” and were banned from showing at galleries and museums on a par with the canvases of A. Bogomazov, D. Burliuk, A. Exter, and “Boychukists”.

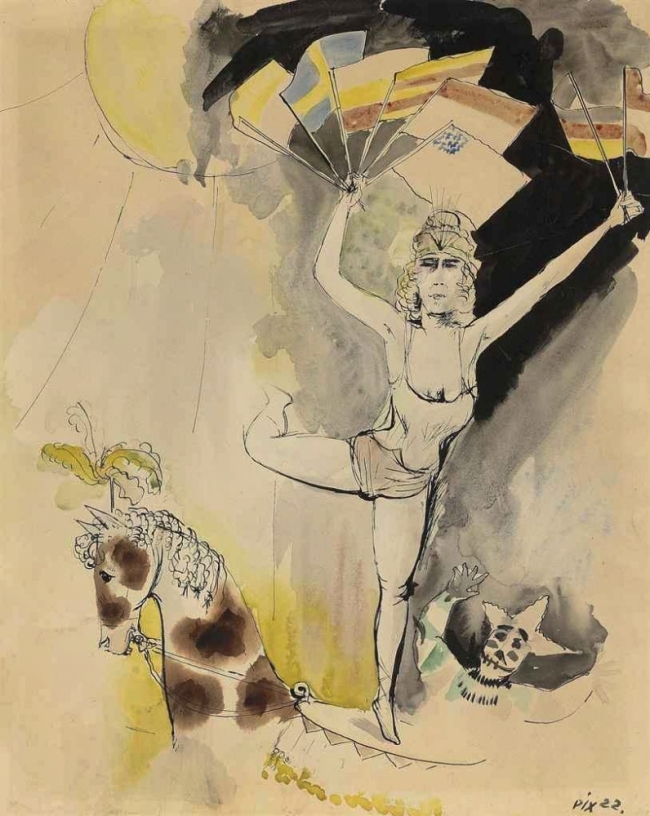

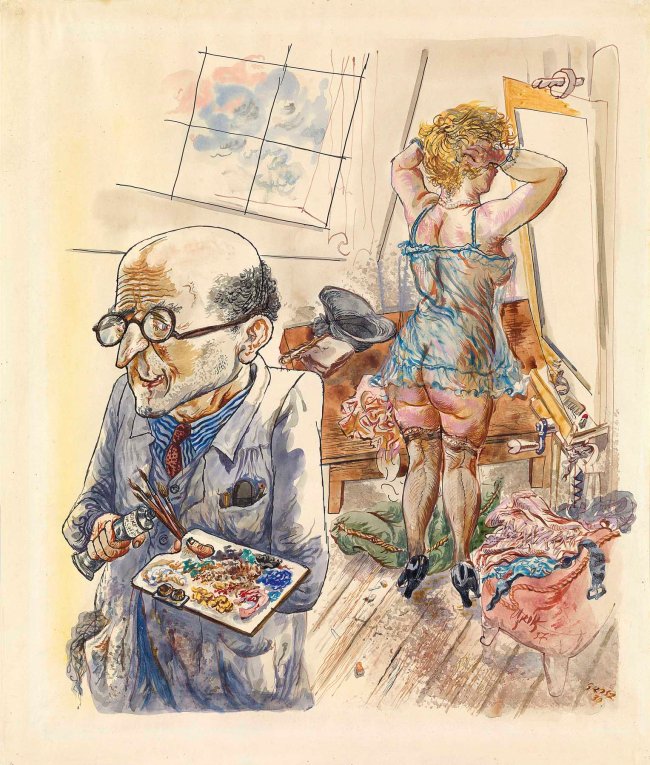

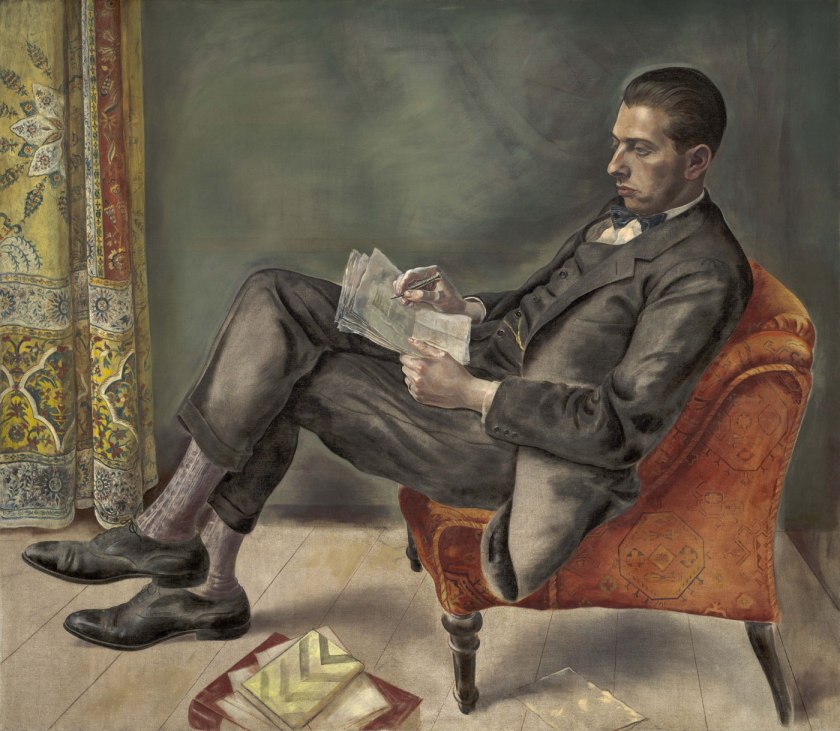

Anatol Petrytskyi (Ukrainian, 1895-1964)

Portrait of Mykhailo Semenko

1929

Watercolour, lead pencil and ink on paper

61.5 x 47.5cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Mykhail Semenko or Mykhailo Vasyliovich Semenko (Ukrainian, 1892-1937) was a Ukrainian poet, and a prominent representative of Ukrainian futurist poetry of the 1920s. He is considered to be one of the lead figures of the Executed Renaissance.

Kazymyr Malevych (Russian, 1879-1935)

Sketch of the painting for the conference hall of the All-Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, Kyiv

1930

Pastel and gouache on paper

44 x 31cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Kazimir Malevich, in full Kazimir Severinovich Malevich, (born February 23 [February 11, Old Style], 1878, near Kyiv, Russian Empire [now in Ukraine] – died May 15, 1935, Leningrad, Russia, U.S.S.R. [now St. Petersburg, Russia]), avant-garde painter who was the founder of the Suprematist school of abstract painting.

Malevich, who was born to parents of Polish origin, studied drawing in Kyiv and then attended the Stroganov School in Moscow and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. In his early work he followed Impressionism as well as Symbolism and Fauvism, and, after a trip to Paris in 1912, he was influenced by Pablo Picasso and Cubism. As a member of the Jack of Diamonds group, he led the Russian Cubist movement.

In 1913 Malevich began to create abstract geometric patterns in a manner he called Suprematism, a term expressing the notion that colour, line, and shape should reign supreme over subject matter or narrative in art. During this period, he painted a few of his most influential works, including Black Square (1915) and Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918). From 1919 to 1921 he taught painting in Moscow and Petrograd (renamed Leningrad in 1924), where he lived the rest of his life. On a 1927 visit to the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, he met Wassily Kandinsky and published a book on his theory under the title Die gegenstandslose Welt (The Non-objective World). Later, when Soviet politicians decided against modern art, Malevich and his art fell out of favour. During his last years, his works show a return to figuration. Malevich died from cancer in poverty and oblivion.

Malevich was the first to exhibit paintings composed of abstract geometric elements. He constantly strove to produce pure cerebral compositions, repudiating all sensuality and representation in art. White on White carries his Suprematist theories to their logical conclusion.

Text from the Brittanica website

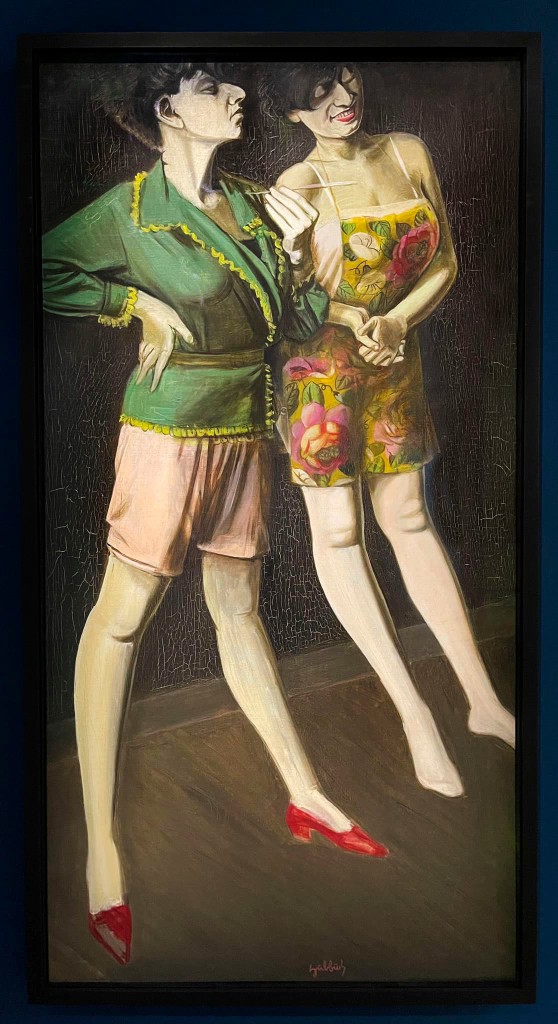

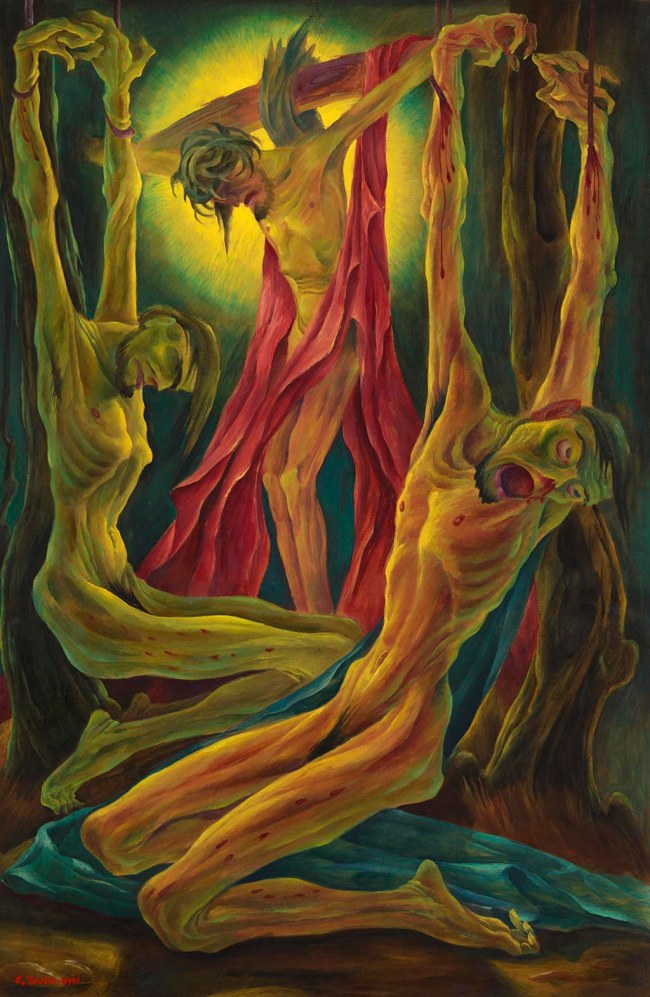

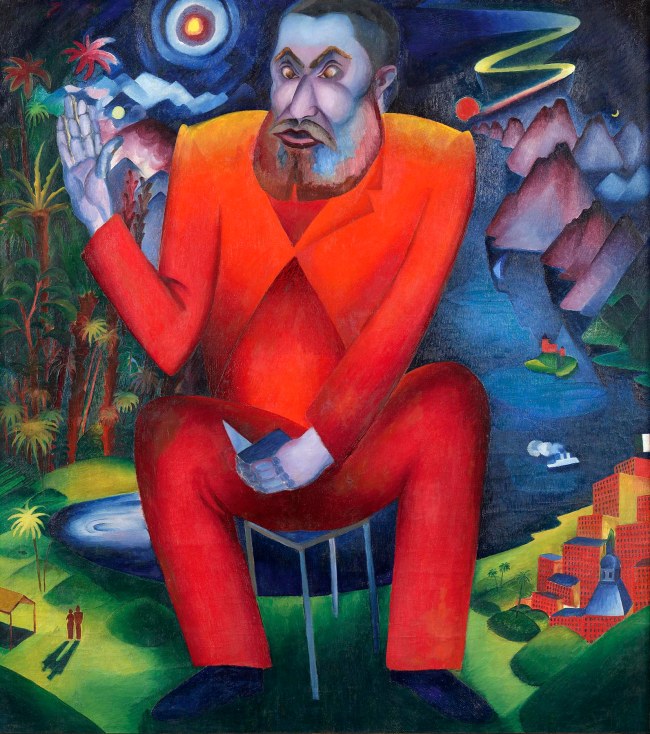

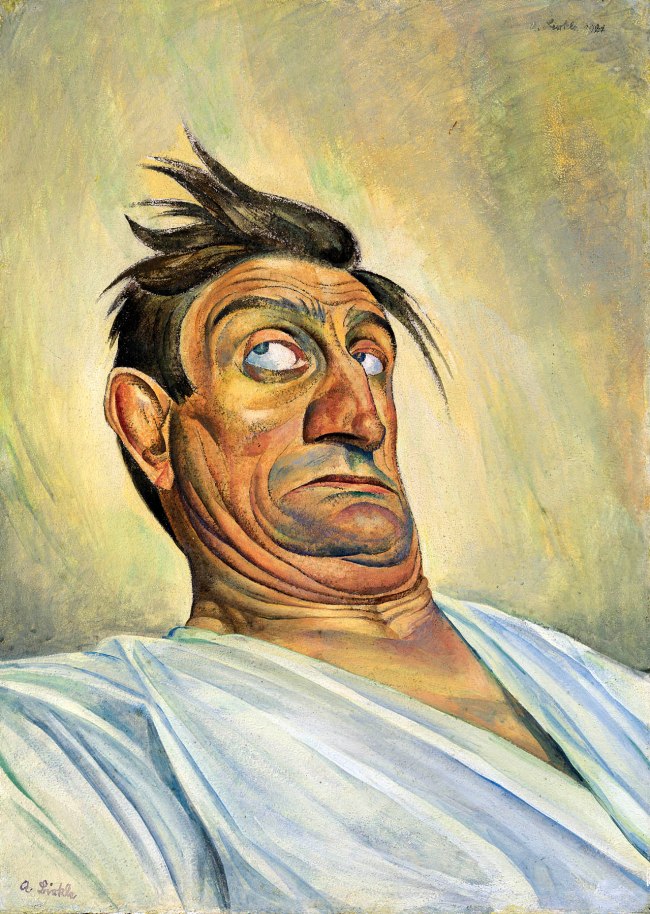

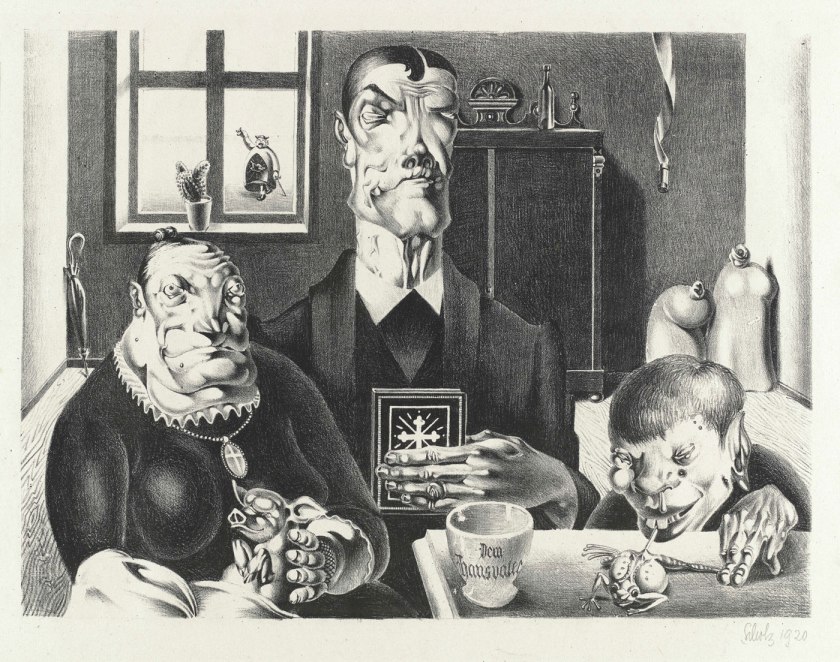

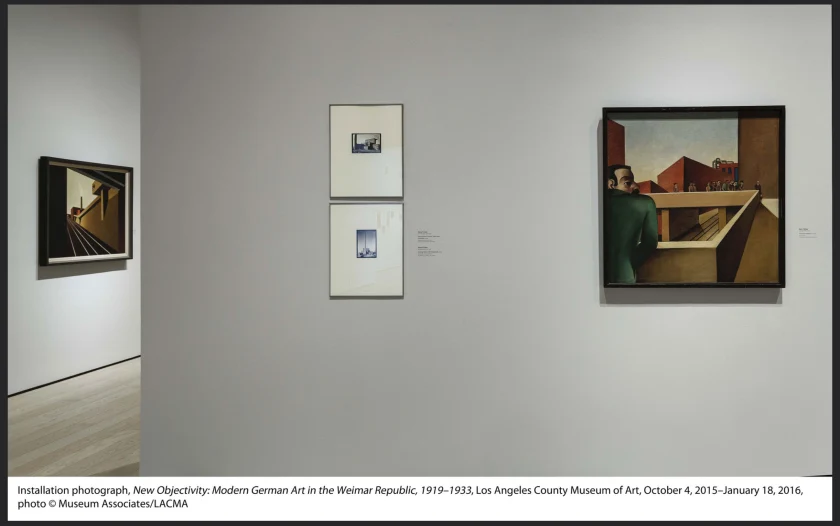

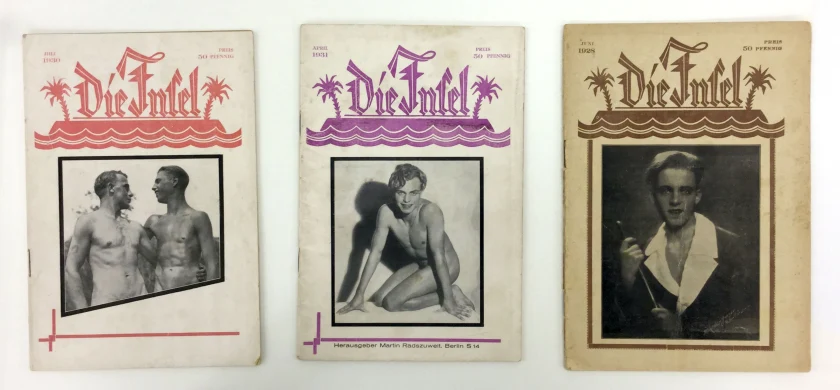

The Last Generation

The last generation of Ukrainian modernists matured in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Mainly graduates of the Kyiv Art Institute, these artists were fascinated with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and Novecento Italiano international movements, but their artistic activity was cut short by a radical change in the political climate. Art was increasingly viewed through a prism of ‘class consciousness’ and Soviet subject matter came to dominate all spheres of artistic output. In 1932, Socialist Realism was introduced as the only official artistic style to be practiced in the Soviet Union, with more value subsequently placed on the rally-like qualities in art rather than the merits of modernist experimentation.

Installation view of the exhibition In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid showing at left, Kostiantyn Yeleva’s Portrait Late 1920s – early 1930s (below); and at right, Semen Yoffe’s In the Shooting Gallery 1932 (below)

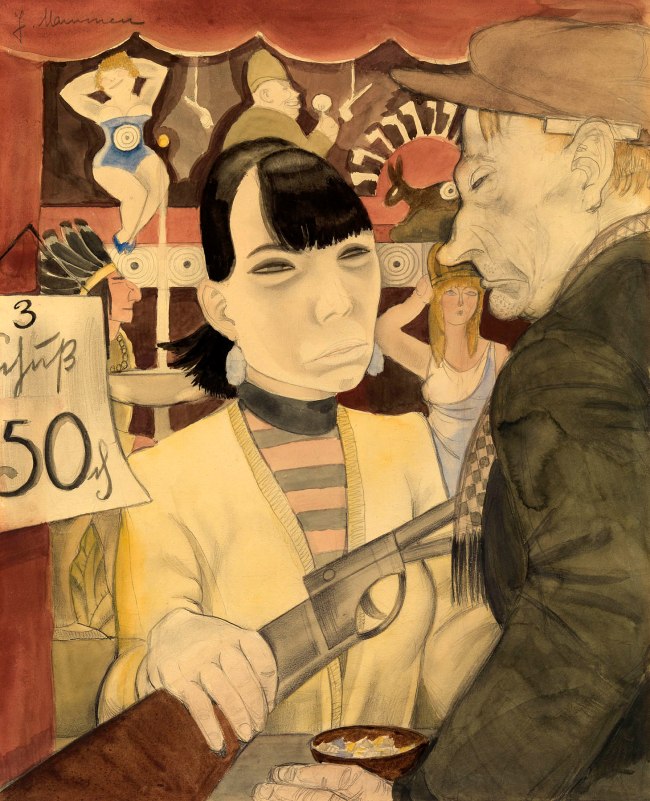

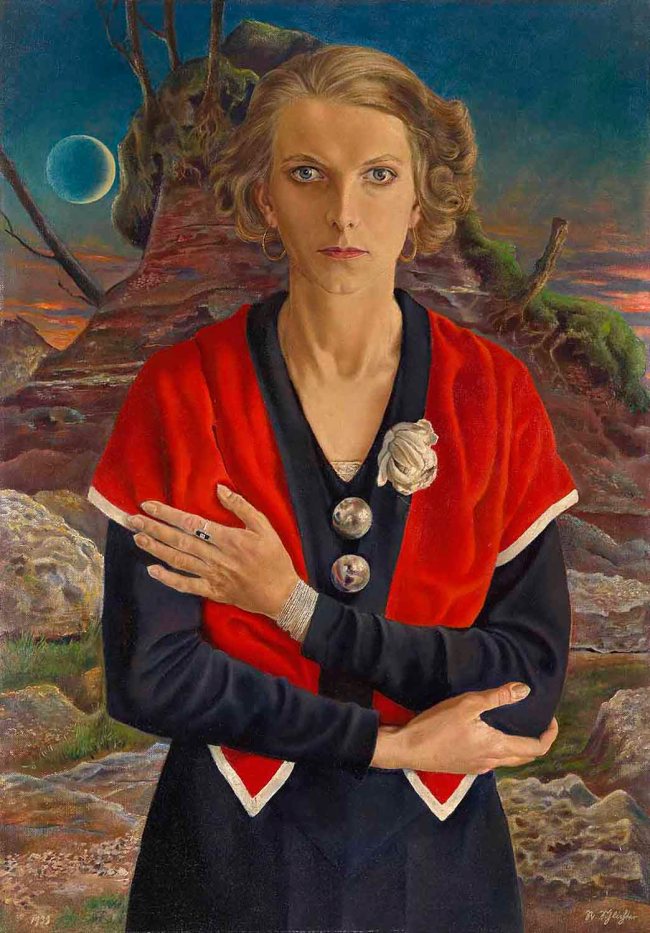

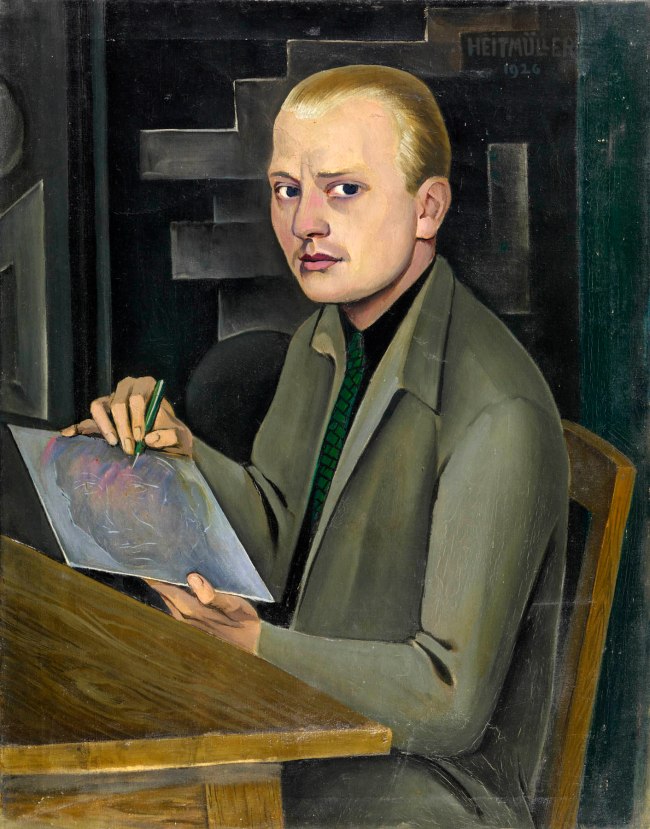

Kostiantyn Yeleva (Ukrainian, 1897-1950)

Portrait

Late 1920s – early 1930s

Oil on canvas

145 x 100cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Drawing, theatrical-decorative painting, and studio artist and teacher. Attended KKhll (1912-1918) and Ukrainian State Academy under Mykhailo Boychuk (1918-1922). Contributed to exhibitions (1917 onwards). Member of ARMU. During the Civil War (1919-1921) and World War II (1943 -1944) worked on political posters. Designer for the First Shevchenko Drama Theater of the Ukrainian SSR, Lesia Ukrainka Theater, the Odesa Ukrainian Drama Theater, and village and army clubs (1919-1926). Taught at KKhU (1926), chaired the Department of Theatrical-Decorative Art and served as Assistant Professor (1930-1932), before becoming Professor in the Drawing Department (1949). Designed patriotic posters for the TASS Windows (1943-1944). Late 1940s onwards also taught graduate courses in drawing at the Academy of Architecture of the Ukrainian SSR. Participated in the Venice Biennale (1928). One-man exhibitions in Kyiv (1940, 1945, 1950).

Text from the Ukrainian Art Library website

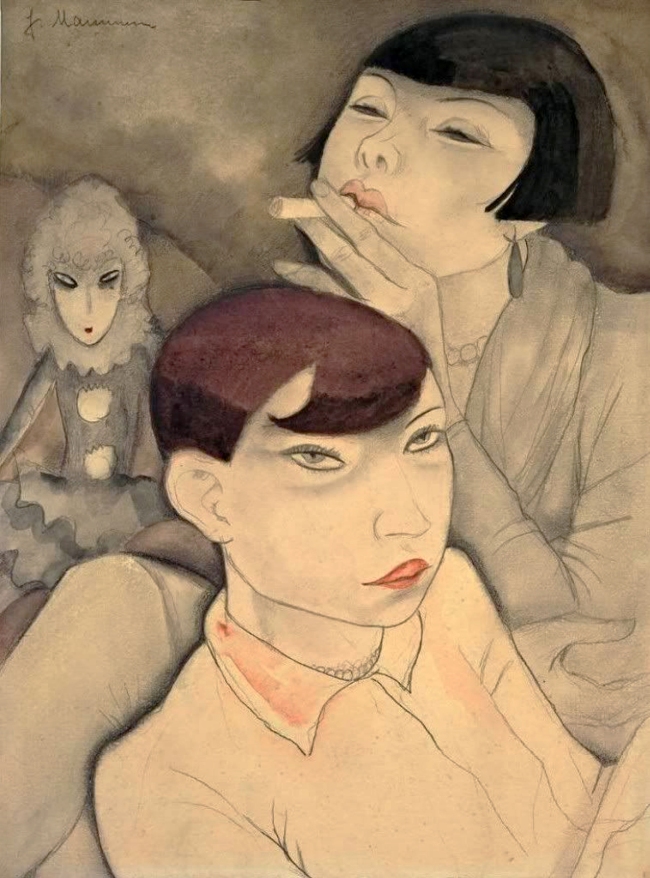

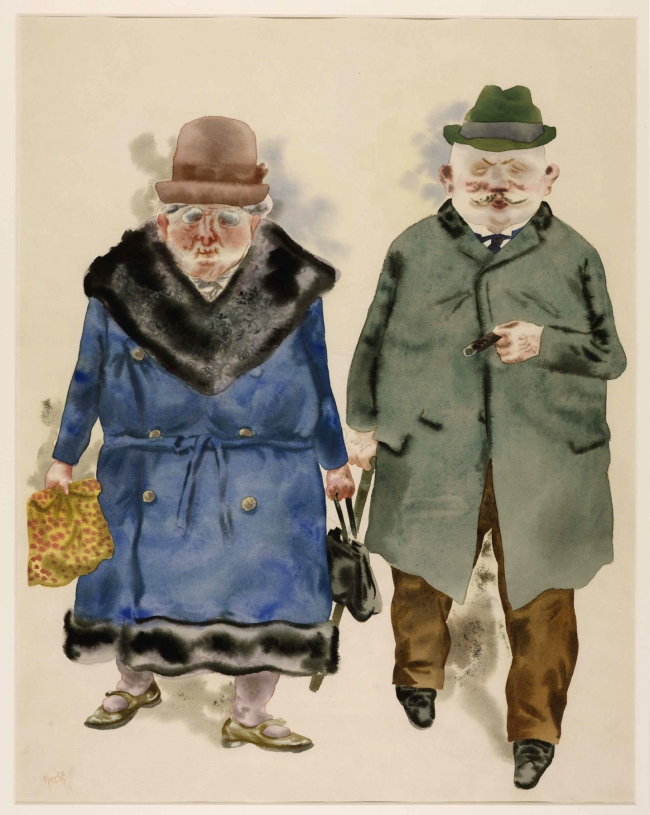

Semen Yoffe (Ukranian, 1909-1991)

In the Shooting Gallery

1932

Oil on canvas

200 x 150cm

National Art Museum of Ukraine

Stage designer. Graduated from Kharkiv Art Institute, where he studied under Vasyl Yermylov and Ivan Padalka (1926-1929); collaborated on the journal Nova generatsiia [New Generation], which reproduced some of his surrealistic drawings (1930). Active as an exhibition installationist and stage designer (1940s onwards).

Text from the Ukrainian Art Library website

Book overview

How does artistic life flourish during revolution and conflict? Ukraine in the early 1900s endured unimaginable political upheaval, yet this became a period of true renaissance in Ukrainian art, literature, theatre and cinema.

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s presents the ground-breaking art produced in Ukraine in the early 20th century, focusing on the three key cultural centres of Kyiv, Kharkiv and Odesa. Against a complicated socio-political backdrop of collapsing empires, World War I, the revolutions of 1917 with the ensuing Ukrainian War of Independence, and the eventual creation of Soviet Ukraine, several strands of distinctly Ukrainian art emerged.

While émigrés such as Sonia Delaunay and Alexander Archipenko found fame outside their homeland, the followers of Mykhailo Boichuk focused on Byzantine revivalism, and the artists of the Kultur Lige sought to promote the development of contemporary Yiddish culture. The first avant-garde exhibitions in Ukraine featured the radical art of Davyd Burliuk and Alexandra Exter, and the dynamic canvases of the Kyiv-based Cubo-Futurist Oleksandr Bohomazov. In Kharkiv, Vasyl Yermilov championed the industrial art of Constructivism, while Vadym Meller, Anatol Petrytskyi, Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov and Borys Kosarev revolutionized theatre design. The attempt to build a national identity in Ukraine resulted in a polyphony of styles and artistic developments across a full range of media – from oil paintings, sketches and sculpture to collages, cinema posters and theatre designs.

Twelve internationally renowned scholars, including curators from the National Art Museum of Ukraine, bring to life this astonishing period of creativity in Ukraine and all the movements it encompassed.

Text from the Thames & Hudson website

Book extract

This volume is dedicated to the dramatic story of Ukrainian modernism. The radical Ukrainian art formed in the last decade of the Russian Empire was a seismographic indicator of the tectonic changes to come, against the background of the upcoming revolution and subsequent attempts to establish an independent state. The Ukrainian modernists actively participated in nation-building, trying to create a recognizable national style. This is their story.

After nearly five years of the bloody War of Independence (1917-21), the Bolsheviks defeated nationalist Ukrainian forces and established the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic (UkrSSR). However, the initial period of Communist rule created a mere illusion of Soviet-controlled cultural autonomy. The policy of ‘Ukrainization’, initially supported by Moscow for tactical reasons, facilitated the rapid development of a national culture that very much proclaimed its own home-grown identity. The 1920s became a time of bold artistic and literary experimentation, a period of true renaissance in Ukrainian art, literature, theatre and cinema. This cultural autonomy helped Ukraine prolong its period of aesthetic experimentation in comparison with other republics in the Soviet Union. Such pivotal figures of the avantgarde art as Kazymyr Malevych (Russian: Kazimir Malevich, Polish: Kazimierz Malewicz, 1879-1935) and Volodymyr Tatlin (Russian: Vladimir Tatlin, 1885-1953), blacklisted early on in Russia as dangerous ‘formalists’, nonetheless found refuge in Kyiv. In Ukraine, as late as 1930, they still could teach, exhibit and publish freely. However, this was just a short period of calm before the inevitable storm. The policy of Ukrainization was abruptly curtailed in 1931, and there were immediate and ruthless purges of the Ukrainian intellectual elite. Numerous poets, writers and theatre directors, along with many artists, faced summary execution or imprisonment in the Gulag. Manuscripts, books and artworks were incinerated. Murals were overpainted or scraped off walls. Later, the martyrs of Ukrainian culture were referred to as the ‘Executed Renaissance’. After severe waves of repression, Ukrainian modernism was doomed to oblivion. Artworks that were not destroyed were sent to secret, purpose-built repositories.

The Great Purges culled artists and intellectuals in the length and breadth of the USSR, but in Ukraine repression started earlier and had a character all its own. In Russia at large, repressed artists and writers were classified as ‘enemies of people’, a broad and generic term. In Ukraine, they were accused of ‘bourgeois nationalism’, an altogether more emotive and destructive appellation. The scene was set, and the destruction of Ukrainian literature and art from 1931 onwards amounted to nothing less than mass cultural genocide. The period 1932-33 saw a broader form of genocide – the Holodomor, often called the Terror-Famine, an artificially induced famine unleashed on Ukraine by the Soviet regime, which took millions of lives. The double catastrophe had far-reaching effects that still resonate to this day, greatly amplified by the most recent invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

During Khrushchev’s abortive de-Stalinization period, interest in Ukrainian modernism started to renew. Some ‘formalist’ works, taboo for so long, were even reinstated in national museums. However, the process was painful and patchy – and behind it lay the ever-present accusation of ‘nationalism’ that had made the rehabilitation of so many Ukrainian artists nearly impossible. At the same time, though, the West had rediscovered the revolutionary avant-garde art of the early Soviet period. The fashion for ‘the Great Experiment of Russian Art’ led to the appropriation of Ukrainian artists, as they conveniently fell under the umbrella term ‘Russian avant-garde’, adroitly coined by the Western art market. By this market-driven alchemy, artists who had spent all their lives in Ukraine, and whose artistic experimentation was integral to the development of Ukrainian art, unexpectedly became ‘Russian’. Western art dealers and museum curators alike followed the old Russian imperialist agenda. Few, if any, attempts were made to clarify the difference between Russian and Ukrainian culture of the period within the art market. In broader terms, we know that the word ‘Russia’ was (and is) frequently used to describe the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and the contemporary Russian Federation – a dangerously misleading if understandable Western generalization.

The real rediscovery of Ukrainian modernism started only after the fall of the Soviet Union and the declaration of Ukraine’s independence in 1991. Despite the publication of important research and the staging of breakthrough exhibitions, the process was not free from mythologizing. To reclaim the legacy of national art, Ukrainian art historians coined the definition ‘Ukrainian avant-garde’. Such a doppelganger of the generalized label, used for marking radical art from the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, often with complete disregard for its geographic provenance, proved to be no less misleading in the Ukrainian case. Ukrainian artists, like their Russian counterparts of the first half of the 20th century, did not use the word ‘avant-garde’ to describe themselves, preferring instead the labels of different ‘isms’ – Futurism, Suprematism, Constructivism, etc. In the case of Ukrainian art, an attempt at a ‘one size fits all’ approach proved to be especially controversial. A good example is the Boichukist school, the only truly monolithic art group in the history of Ukrainian modernism. It was united by the artistic method and ideology of Byzantine revivalism and a pronounced orientation towards folk culture, so it was retrospective in essence and had nothing in common with radical experimentation. Attempts to classify it as avant-garde seem at best naive. Apart from Mykhailo Boichuk (1882-1937) and his followers, Ukrainian art did not produce any other movements united by a definite aesthetic preference. Polyphony dominated the landscape of national modernism, with artists creating their own personal ‘isms’, such as the ‘colourism’ of Viktor Palmov (1888-1929). Others developed their versions of international trends, often quite different from the source of inspiration, a principal example being the Cubo-Futurism of Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880-1930) or the ‘Constructivism’ propagated by Vasyl Yermilov (1894–1968).

Many representatives of Ukrainian modernism escape straightforward stylistic classification. A case in point is Anatol Petrytskyi (1895–1964), who was influenced by different international movements from Cubism to Constructivism, adopting them in his work in a highly individualized manner. The polyphony of identities supplemented the polyphony of styles, so that many artists born in Ukraine continued their careers in Russia or in other foreign countries but left a strong imprint on the development of Ukrainian art. One considers the mark left by Davyd Burliuk (Russian: David Burliuk, 1882-1967) and Alexandra Exter (Ukrainian: Oleksandra Ekster, 1882-1949) on the development of the local version of Cubo-Futurism, or the influence of Kazymyr Malevych, an ethnic Pole born in Kyiv, on Ukrainian artists. A further voice in this complex polyphony was Viktor Palmov, a Russian who relocated to Kyiv at the beginning of the 1920s and became one of the most active participants in the country’s artistic processes. Bearing all these complexities in mind, one might reasonably conclude that ethnic labelling within the modernist movement in Ukraine, during the time of the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union, can hardly help create an appropriately nuanced and realistic picture of the development of Ukrainian art.

Oleh Ilnytzkyj, the pioneer of research on Ukrainian literary Futurism, wrote about the reassessment of the history of the movement during the period of the Russian Empire: ‘The goal is not to place a new “Ukrainian” straitjacket on cultural activities in the empire, but to find way to do justice to the variety of sources and the myriad of cultural influences that flowed from so many directions. The recognition of Burliuk, Ekster and Malevich as Ukrainians does not diminish their relevance for either the imperial (transnational) avant-garde or for strictly Russian culture, where their impact is undeniable.’ Such an approach is also applicable to many artists of the Soviet period, from Klyment Redko (Russian: Kliment Redko, 1897-1956) to Oleksandr Tyshler (Russian: Aleksandr Thyshler, 1898-1980).

One of the main tasks for Ukrainian artists at the beginning of the 20th century was to create a national style. They were not alone. The age of nationalism, on the rise in Europe since the Napoleonic wars, provoked the nation-building earthquake following the collapse of the empires in 1917-18. Art played an essential role in the seismic shift. Art Nouveau, defined in Germany and Austria as Secession, in Italy as Liberty, and in Russia as Modern, became the last international style to produce a dominant visual language. The paradox was that similar stylistic features were used to visualize different national mythologies from Paris and Berlin to Helsinki and Kyiv. The Ukrainian version of Art Nouveau was no less of an attempt to find a national artistic form of self-expression. The cosmopolitan style of Oleksandr Murashko (1875-1919) was challenged by Mykhailo Zhuk (1883-1964), and especially by the Krychevski brothers, who opted for national topicality and found inspiration in Ukrainian folk art. In addition to folk art, there were other and no less important primary sources of inspiration for the Ukrainian Art Nouveau practitioners. Early medieval mosaics and frescoes, created under strong Byzantine influence, was one such. The Ukrainian Baroque of the 17th and early 18th centuries was another. It is not surprising, given the vigour and eclecticism of the movement, that the visual identity of the short-lived independent Ukrainian state of 1917–20, including the coat of arms and banknotes, created by Heorhii Narbut (1886–1920), was an exquisite example of the national version of Art Nouveau.

Ukrainian advocates of radical modernism were also very interested in co-opting the folk traditions. Ukrainian naïve pictures, embroideries, ornaments and painted eggs all fascinated Exter and Davyd Burliuk, both members of the Kyiv Cubo-Futurist scene. They were the pioneers of the transformation of the folklore elements into ‘radical chic’. The passion for folk art and ornament became an inherent part of ‘Ukrainian-ness’ in the country’s modernism, extending to such unexpected territory as the constructivist designs of Vasyl Yermilov. Despite this happy and inventive immersion in folklore, it is important to remember that the Ukrainian artists’ preoccupation with tradition was very different from that of their Russian counterparts, whose approach to folk art broadly proceeded in two directions. On the one hand, the Russians embraced naive village art, or the kitsch aspects of urban sub-culture, as a kind of shock tactic, a means to épater le bourgeois by glorifying ‘lower’ rather than ‘higher’ elements of culture. On the other, native folklore and folk art were often seen as a viable homegrown alternative to exotic, foreign imports from France and elsewhere – the perfect means by which Russian modernists might take a stance against Western decadence. Such calculated feelings were utterly foreign to Ukrainian artists, whose studious attention to folk art and ornamentation was quite devoid of irony or strategy. However radical Ukrainian modernists were, they felt they had inherited the task of establishing a national visual language from their predecessors, and took it very seriously. Unfortunately, Ukrainian modernism in all its aspects, aside from folklore influences, has been historically analysed predominantly through the lens of comparison with Russian art. Perhaps now is the time to look at it in the context of the development of modernist traditions in such Central European countries as Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic, where the local schools who sought a national art style were no less influenced by folk tradition than those in Ukraine.

If the Ukrainian art of the 1910s-20s has already been reasonably researched and analysed, the enforced transition to Socialist Realism still requires profound conceptualization. The attempts of leading modernists like Oleksandr Bohomazov and Viktor Palmov to find their place in the new, politically imposed frame of reference, resulted in masterpieces characterized by a new and sometimes uncomfortable hybridity of styles that certainly requires further investigation. In the same vein, the efforts of Boichukists to adjust their art to the changing demands of the time also requires fresh analysis. Their status as martyrs of Ukrainian art often precludes a dispassionate discourse on the transformation of their style, and their participation in the development of Stalinist propaganda and iconography. Whether such a shift was the result of a Faustian pact or sincere political belief remains to be answered, case by case. Fresh territory for research and discussion in Ukrainian art history is being mapped out year after year. The ground-breaking exhibition ‘Spetsfond’ (Special Secret Holding), organized by the National Art Museum of Ukraine in 2015, resulted in the rediscovery of Ukrainian art of the early 1930s. For the first time, numerous paintings, hidden for more than half a century for political reasons, were returned to public display. The show restored to Ukrainian art history the names and reputations of such painters as Kostiantyn Yeleva (1897-1950), Semen Yoffe (1909-1991) and Yurii Sadylenko (1903-1967). This was just a start, and so much more is yet to be done. For example, the influence of such trends as Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and Il Novecento Italiano on Ukrainian artists still requires fundamental investigation – and while research into Ukrainian cinema has been greatly stimulated though the activity of the Oleksandr Dovzhenko National Centre, the history of Ukrainian photography from the 1920s and early 1930s remains largely terra incognita. This volume and the exhibition that accompanies it constitute an attempt to introduce the international public to the complicated history of Ukrainian modernism, an essential but little-known part of European culture.

Extracted from In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Paseo del Prado 8, 28014 Madrid, Spain

Phone: 91 791 13 70

Opening hours:

Monday: 12.00 – 16.00

Tuesday to Sunday: 10.00 – 19.00

![Vasyl Yermilov (Ukrainian, 1894-1967) 'Nove Mystetstvo' ([New Art], magazine cover design) c. 1927 Vasyl Yermilov (Ukrainian, 1894-1967) 'Nove Mystetstvo' ([New Art], magazine cover design) c. 1927](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2023/03/yermilov_nove_mystetsvo.jpg?w=650&h=975)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) '[Unemployed Man in Winter Coat, Hat in Hand]' 1920](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/unemployed-man-in-winter-coat-hat-in-hand-1920-august-sander1.jpg?w=650&h=983)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]' 1928-1932](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/sander-maler-web.jpg?w=650&h=813)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Proletarian Intellectuals' [Else Schuler, Tristan Rémy, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Gerd Arntz] c. 1925](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/07/august-sander-proletarian-intellectuals.jpg?w=650&h=823)

![George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view) George Grosz (Georg Ehrenfried Gross) (German, 1893-1959) 'Construction (Untitled)' (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel]) 1920 (installation view)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2022/08/germany-installation-g.jpg?w=650&h=894)

![George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920 George Grosz. 'Construction (Untitled) (Konstruktion [Ohne Titel])' 1920](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/grosz-construction.jpg?w=650&h=867)

![Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928 Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) 'Bügeleisen für Schuhfabrikation, Faguswerk Alfeld [Shoemakers' irons, Fagus factory, Alfeld]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/renger-patzsch-bugeleisen-fur-schuhfabrikation.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bohemians [Willi Bongard, Gottfried Brockmann]' c. 1922-5, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bohemians [Willi Bongard, Gottfried Brockmann]' c. 1922-5, printed 1990](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/august-sander-bohemians-willi-bongard-gottfried-brockmann-c-1922e280935-web.jpg?w=840)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Photographer [August Sander]' 1925, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Photographer [August Sander]' 1925, printed 1990](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/august_sander_august_sander_1925-web.jpg?w=650&h=924)

![Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974) 'Untitled (Couple)' (Ohne Titel [Paar]), 1926 Gert Wollheim (German, 1894-1974) 'Untitled (Couple)' (Ohne Titel [Paar]), 1926](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/wollheim-untitled.jpg?w=650&h=879)

![Florence Henri. 'Composition abstraite [Still-life composition]' 1929](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/florencehenri_08_compositionabstraite-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Mannequin de tailleur [Tailor's mannequin]' 1930-1931](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/florencehenri_05__mannequindetailleur-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Composition Nature morte [Still-life composition]' 1931](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/florencehenri_10_compositionnaturemorte-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Pont [Bridge]' 1930-1935](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/03/florencehenri_21_pont-web.jpg?w=840)