Exhibition dates: 30th July 2018 – 14th July 2019

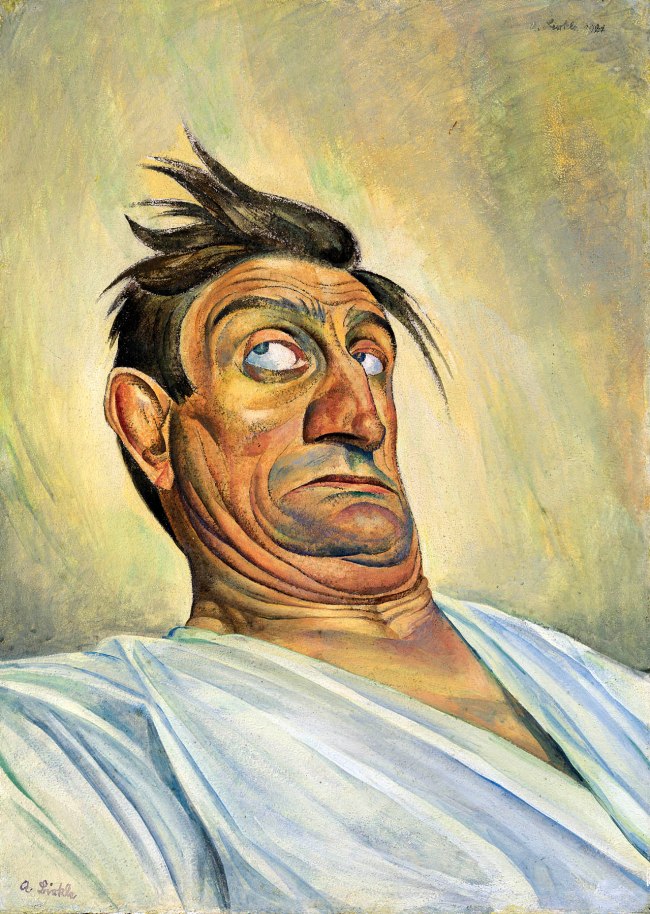

Conrad Felixmüller (German, 1897-1977)

The Beggar of Prachatice

1924

Watercolour, gouache and graphite on paper

500 x 645 mm

The George Economou Collection

© DACS, 2018

Butchers, lion tamers, and Lustmord (sexualised murder) makers. War, rape, prostitution, violence, old age and death. Creativity, defeat, disfigurement, and revelry. Suicide and misery, poverty and widowhood, beauty and song. Magic in realism, realism and magic.

The interwar years are one of the most creative artistic periods in human history. But there is a magical dark undertone which emanates from the mind of this Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity:

“The art historian Dennis Crockett says there is no direct English translation, and breaks down the meaning in the original German:

Sachlichkeit should be understood by its root, Sache, meaning “thing”, “fact”, “subject”, or “object.” Sachlich could be best understood as “factual”, “matter-of-fact”, “impartial”, “practical”, or “precise”; Sachlichkeit is the noun form of the adjective/adverb and usually implies “matter-of-factness” …

The New Objectivity was composed of two tendencies which Hartlaub characterised in terms of a left and right wing: on the left were the verists, who “tear the objective form of the world of contemporary facts and represent current experience in its tempo and fevered temperature;” and on the right the classicists, who “search more for the object of timeless ability to embody the external laws of existence in the artistic sphere.”

The verists’ vehement form of realism emphasised the ugly and sordid. Their art was raw, provocative, and harshly satirical. George Grosz and Otto Dix are considered the most important of the verists. The verists developed Dada’s abandonment of any pictorial rules or artistic language into a “satirical hyperrealism”, as termed by Raoul Hausmann, and of which the best known examples are the graphical works and photo-montages of John Heartfield. Use of collage in these works became a compositional principle to blend reality and art, as if to suggest that to record the facts of reality was to go beyond the most simple appearances of things. This later developed into portraits and scenes by artists such as Grosz, Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter. Portraits would give emphasis to particular features or objects that were seen as distinctive aspects of the person depicted. Satirical scenes often depicted a madness behind what was happening, depicting the participants as cartoon-like.

Other verists, like Christian Schad, depicted reality with a clinical precision, which suggested both an empirical detachment and intimate knowledge of the subject. Schad’s paintings are characterised by “an artistic perception so sharp that it seems to cut beneath the skin”, according to the art critic Wieland Schmied. Often, psychological elements were introduced in his work, which suggested an underlying unconscious reality.

Compared to the verists, the classicists more clearly exemplify the “return to order” that arose in the arts throughout Europe. The classicists included Georg Schrimpf, Alexander Kanoldt, Carlo Mense, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, and Wilhelm Heise. The sources of their inspiration included 19th-century art, the Italian metaphysical painters, the artists of Novecento Italiano, and Henri Rousseau.

The classicists are best understood by Franz Roh’s term Magic Realism, though Roh originally intended “magical realism” to be synonymous with the Neue Sachlichkeit as a whole. For Roh, as a reaction to expressionism, the idea was to declare “[that] the autonomy of the objective world around us was once more to be enjoyed; the wonder of matter that could crystallise into objects was to be seen anew.” With the term, he was emphasising the “magic” of the normal world as it presents itself to us – how, when we really look at everyday objects, they can appear strange and fantastic.” (Text from the Wikipedia website)

It strikes me, with a slap of the hand across the face, that the one, realism, cannot live cannot breathe with/out the other, the Other, magic. One cannot coexist without the other, as in the body not living without oxygen to breathe: one occupies the other whilst itself being inhabited. The precondition to reality is in essence the unknown. As order relies on mutation to define itself, so reality calls forth that form of hyperrealism, a state of magic, that we can have knowledge of (the image of ourselves before birth, that last image, can we remember, before death) but cannot mediate.

Magic/realism is no duality but a fluid, observational, hybridity which exists on multiple planes of reality – from the downright mad and evil to the ecstatic and revelatory. The fiction of a stable reality is twisted; magic or the supernatural is supposedly presented in an otherwise real-world or mundane setting. Or is it the other way round? Or no way round at all?

It is the role of the artist to set up opposites, throwing one against the other, to throw… into the void.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Tate Modern for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Tate Modern will explore German art from between the wars in a year-long, free exhibition, drawing upon the rich holdings of The George Economou Collection.

These loans offer a rare opportunity to view a range of artworks not ordinarily on public display, and to see a small selection of key Tate works returned to the context in which they were originally created and exhibited nearly one hundred years ago.

This presentation explores the diverse practices of a number of different artists, including Otto Dix, George Grosz, Albert Birkle and Jeanne Mammen. Although the term ‘magic realism’ is today commonly associated with the literature of Latin America, it was inherited from the artist and critic Franz Roh who invented it in 1925 to describe a shift from the art of the expressionist era, towards cold veracity and unsettling imagery. In the context of growing political extremism, the new realism reflected a fluid social experience as well as inner worlds of emotion and magic.

“Art is exorcism. I paint dreams and visions too; the dreams and visions of my time. Painting is the effort to produce order; order in yourself. There is much chaos in me, much chaos in our time.”

Otto Dix

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Assault Troops Advance under Gas (Sturmtruppe geht unter Gas vor)

1924

© DACS 2017

Image: Otto Dix Stiftung

Otto Dix World War I service

When the First World War erupted, Dix enthusiastically volunteered for the German Army. He was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden. In the autumn of 1915 he was assigned as a non-commissioned officer of a machine-gun unit on the Western front and took part in the Battle of the Somme. In November 1917, his unit was transferred to the Eastern front until the end of hostilities with Russia, and in February 1918 he was stationed in Flanders. Back on the western front, he fought in the German Spring Offensive. He earned the Iron Cross (second class) and reached the rank of vizefeldwebel. In August of that year he was wounded in the neck, and shortly after he took pilot training lessons.

He took part in a Fliegerabwehr-Kurs (“Defense Pilot Course”) in Tongern, was promoted to Vizefeldwebel and after passing the medical tests transferred to Aviation Replacement Unit Schneidemühl in Posen. He was discharged from service in 22 December 1918 and was home for Christmas.

Dix was profoundly affected by the sights of the war, and later described a recurring nightmare in which he crawled through destroyed houses. He represented his traumatic experiences in many subsequent works, including a portfolio of fifty etchings called Der Krieg, published in 1924. Subsequently, he referred again to the war in The War Triptych, painted from 1929-1932.

Text from the Wikipedia website

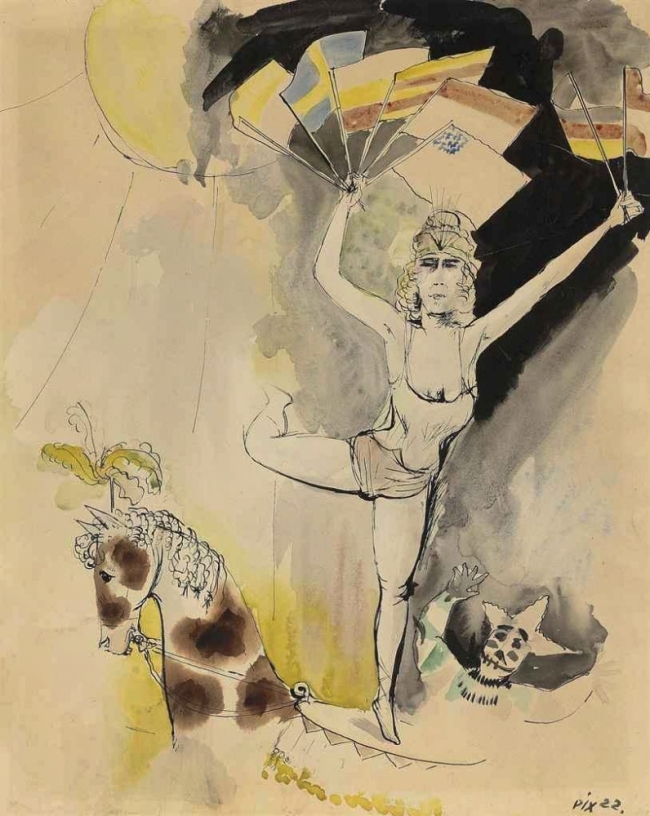

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

International Riding Act (Internationaler Reitakt)

1922

Etching, drypoint on paper

496 x 431 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

International Riding Scene (Internationale Reiterszene)

1922

Watercolour, pen and ink on paper

510 × 410 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

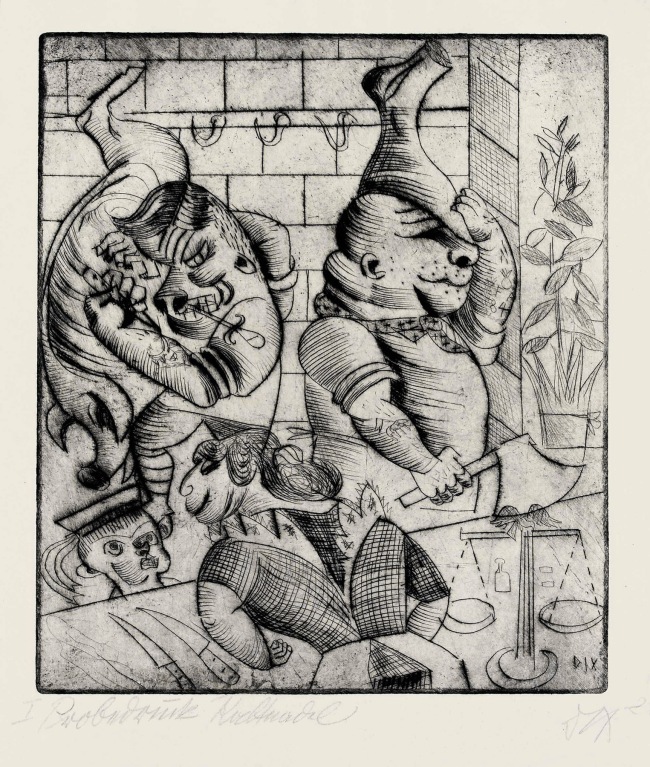

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Butcher Shop (Fleischerladen)

1920

Etching, drypoint on paper

495 x 338 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Lion-Tamer (Dompteuse)

1922

Etching, drypoint on paper

496 x 429 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Lust Murder (Lustmord)

1922

Watercolour, ink and graphite on paper

485 x 365 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

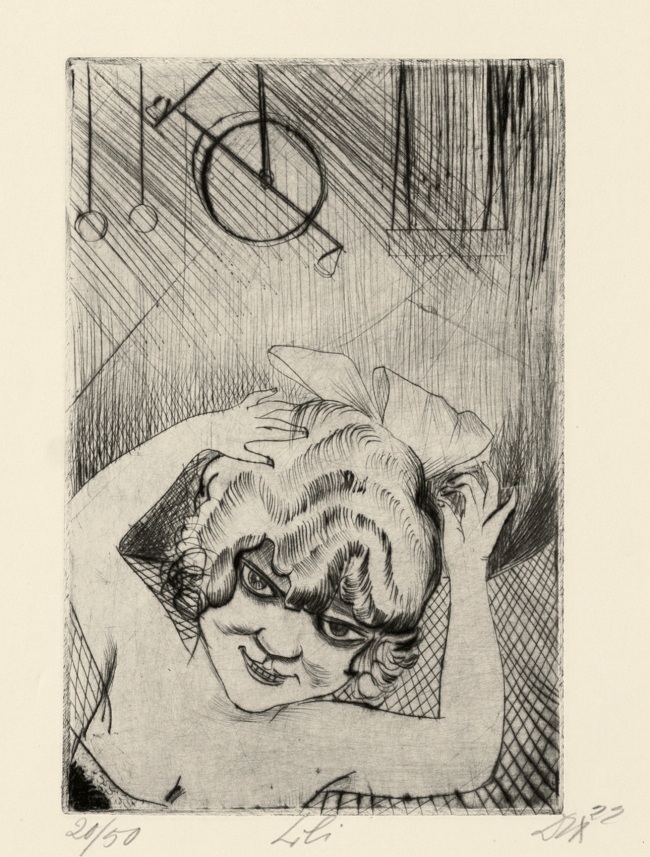

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Lili, the Queen of the Air (from Circus portfolio)

1922

Etching, drypoint on paper

The George Economou Collection

© The Estate of Otto Dix 2018

Otto Dix Post-war artwork

At the end of 1918 Dix returned to Gera, but the next year he moved to Dresden, where he studied at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste. He became a founder of the Dresden Secession group in 1919, during a period when his work was passing through an expressionist phase. In 1920, he met George Grosz and, influenced by Dada, began incorporating collage elements into his works, some of which he exhibited in the first Dada Fair in Berlin. He also participated in the German Expressionists exhibition in Darmstadt that year.

In 1924, he joined the Berlin Secession; by this time he was developing an increasingly realistic style of painting that used thin glazes of oil paint over a tempera underpainting, in the manner of the old masters. His 1923 painting The Trench, which depicted dismembered and decomposed bodies of soldiers after a battle, caused such a furore that the Wallraf-Richartz Museum hid the painting behind a curtain. In 1925 the then-mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, cancelled the purchase of the painting and forced the director of the museum to resign.

Dix was a contributor to the Neue Sachlichkeit exhibition in Mannheim in 1925, which featured works by George Grosz, Max Beckmann, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Karl Hubbuch, Rudolf Schlichter, Georg Scholz and many others. Dix’s work, like that of Grosz – his friend and fellow veteran – was extremely critical of contemporary German society and often dwelled on the act of Lustmord, or sexualised murder. He drew attention to the bleaker side of life, unsparingly depicting prostitution, violence, old age and death.

In one of his few statements, published in 1927, Dix declared, “The object is primary and the form is shaped by the object.”

Among his most famous paintings are Sailor and Girl (1925), used as the cover of Philip Roth’s 1995 novel Sabbath’s Theater, the triptych Metropolis (1928), a scornful portrayal of depraved actions of Germany’s Weimar Republic, where nonstop revelry was a way to deal with the wartime defeat and financial catastrophe, and the startling Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden (1926). His depictions of legless and disfigured veterans – a common sight on Berlin’s streets in the 1920s – unveil the ugly side of war and illustrate their forgotten status within contemporary German society, a concept also developed in Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Technical Personnel (Technisches Personal)

1922

Etching, drypoint on paper

497 x 426 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Magic Realism

The term magic realism was invented by German photographer, art historian and art critic Franz Roh in 1925 to describe modern realist paintings with fantasy or dream-like subjects.

The term was used by Franz Roh in his book Nach Expressionismus: Magischer Realismus (After Expressionism: Magic Realism).

In Central Europe magic realism was part of the reaction against modern or avant-garde art, known as the return to order, that took place generally after the First World War. Magic realist artists included Giorgio de Chirico, Alberto Savinio and others in Italy, and Alexander Kanoldt and Adolf Ziegler in Germany. Magic realism is closely related to the dreamlike depictions of surrealism and neo-romanticism in France. The term is also used of certain American painters in the 1940s and 1950s including Paul Cadmus, Philip Evergood and Ivan Albright.

In 1955 the critic Angel Flores used the term magic realism to describe the writing of Jorge Luis Borges and Gabriel García Márquez, and it has since become a significant if disputed literary term.

Text from the Tate website [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

George Grosz (German, 1893-1959)

Suicide (Selbstmörder)

1916

Oil paint on canvas

1000 x 775 mm

Tate

Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund 1976

The horrific picture of Suicide by Groz astonishes by its savage imagery, harsh colours and restless composition. Highlighting the misery of the middle class who has no means to live on today and no future tomorrow, the artist gets one man strung up on a lamp post and the other shot on a stage just near a prompter guy in his cabin. Is his death a real thing or is it a part of some performance? It seems to be quite real because everybody promptly abandons the scene except for the hungry dogs roaming the desolate streets of Berlin. And these murders are no worse than dubious pleasures given by an ugly, man-like prostitute to an aged bald client visiting her in a cheap apartment block – the only source of solace from the cold and desolation for the bourgeois at the time. The pervasive moral corruption in Berlin during the war years is underlined by the forsaken Kirche at the back.

Text from the Arthive website [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

Grosz was drafted into the German army in 1914, after the outbreak of the First World War. His experiences in the trenches deepened his intense loathing for German society. Discharged from the army for medical reasons, he produced savagely satirical paintings and drawings that ‘expressed my despair, hate and disillusionment’. This work shows dogs roaming past the abandoned bodies of suicides in red nocturnal streets. The inclusion of an aged client visiting a prostitute reflects the pervasive moral corruption in Berlin during the war years.

Gallery label, September 2004

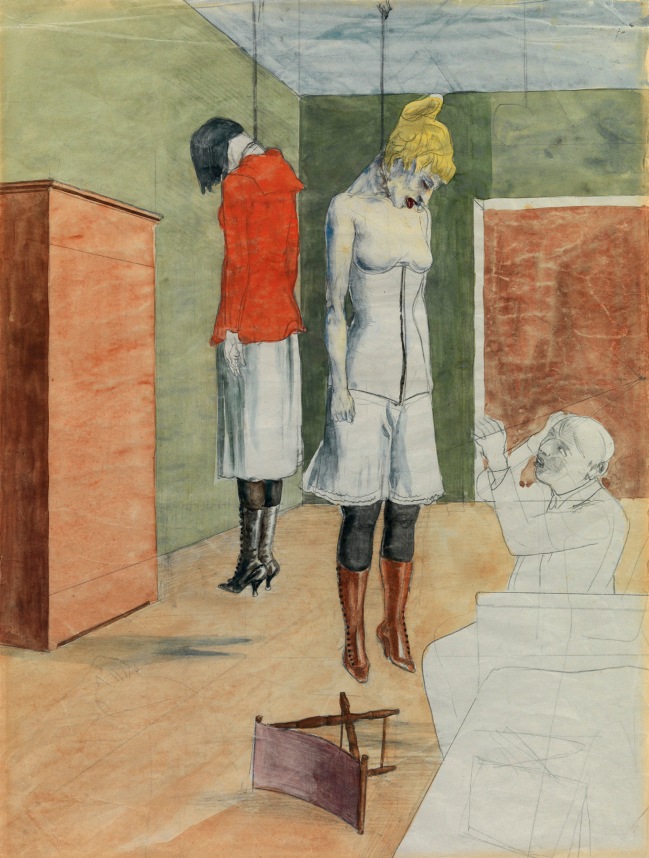

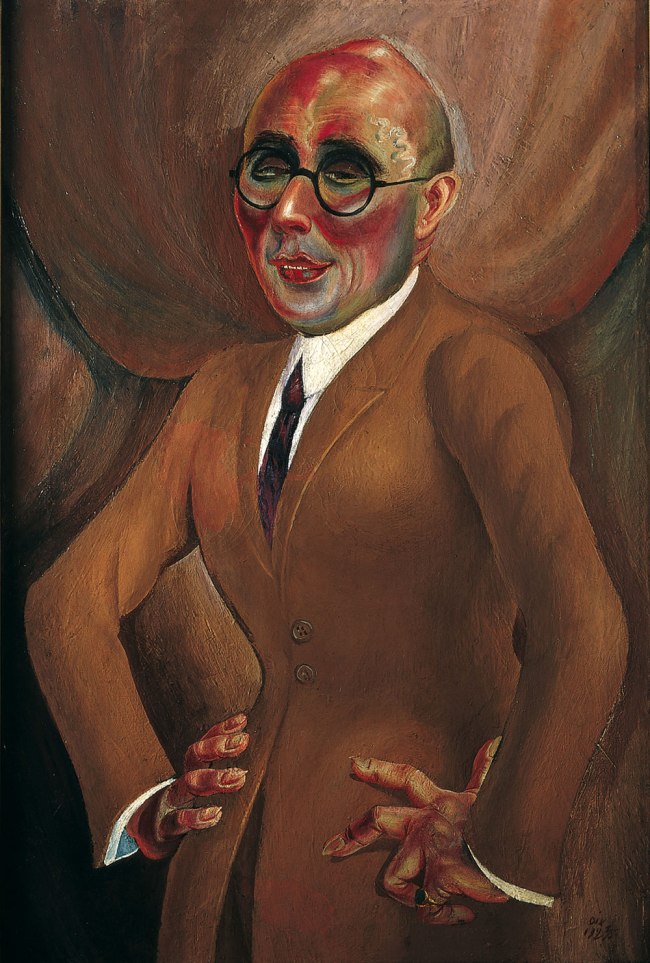

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

The Artist with Two Hanged Women (Der Künstler mit zwei erhängten Frauen)

1924

Watercolour and graphite on paper

453 x 340 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Sexualised murder was a recurrent theme within this period: the exhibition holding a number of other works similar to the piece by Dix. An example is Rudolf Schlichter’s The Artist with Two Hanged Women watercolour. Schlichter was known to have sexual fantasies revolved around hanging, as well as an obsession with women’s buttoned boots. Acting as a self-portrait, the image represents Schlichter’s private fantasies, whilst also drawing upon the public issues of suicide, which saw an unsettling rise during this period.

Text by Georgia Massie-Taylor from the G’s Spots blog

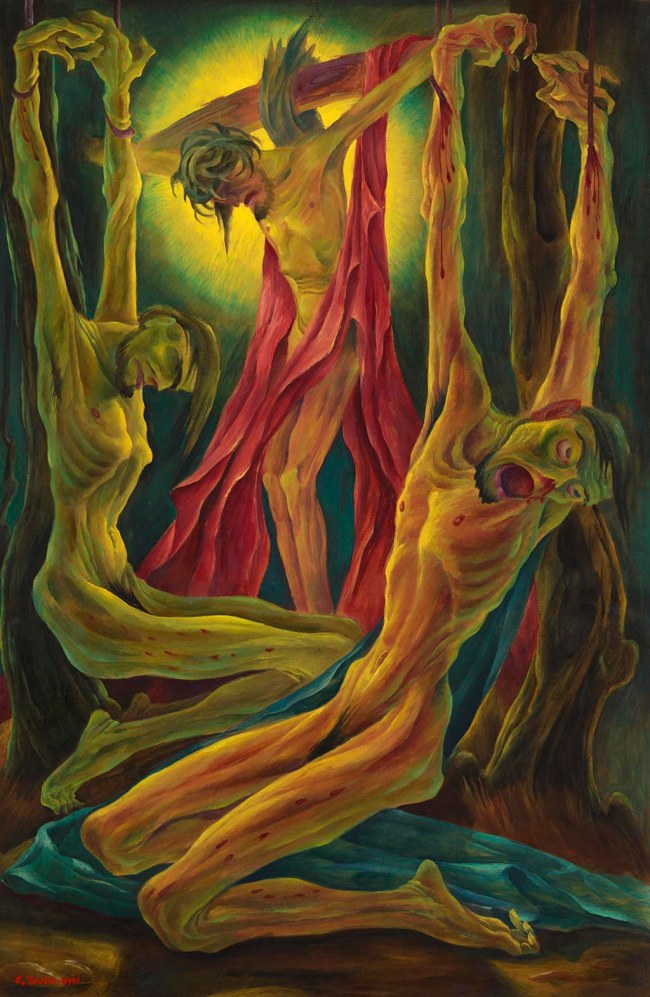

Albert Birkle (German, 1900-1986)

Crucifixion (Kreuzigung)

1921

Oil paint on board

920 x 607 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

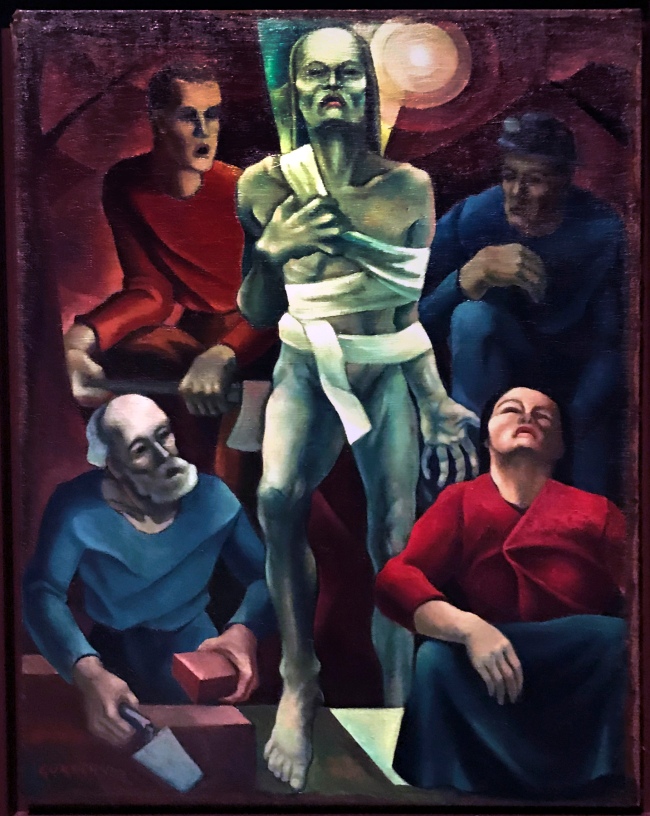

Herbert Gurschner (Austrian, 1901-1975)

Lazarus (The Workers) (Lazarus (Die Arbeiter))

1928

Oil paint on canvas

920 x 690 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Herbert Gurschner (Austrian, 1901-1975)

Herbert Gurschner was born on August 27, 1901 in Innsbruck. In 1917 he attended the art school in Innsbruck and had his first exhibition. Between 1918 and 1920 he studied at the Munich Art Academy. After that he had other exhibitions in Innsbruck.

In 1924 he married an English nobleman, through which he came to London artist and collector circles. In 1929 he had his first exhibition in the London Fine Art Society. Two years later, he showed another exhibition in the Fine Art Society and made the artistic breakthrough in England. Subsequently, he was able to open several exhibitions throughout the UK. Herbert Gurschner found access to aristocratic, diplomatic and business circles and was able to exhibit his works in New York City, among others .

At the time of World War II Gurschner obtained British citizenship and served in the British army. During this time, he met his future second wife, the actress Brenda Davidoff, with whom he lived in London. In the postwar years Gurschner exhibited only sporadically and instead focuses on the stage design (including for the Royal Opera House, Globe Theater and Hammersmith Apollo). On January 10, 1975 Gurschner died in London.

Text from the German Wikipedia website translated by Google Translate

Herbert Gurschner (Austrian, 1901-1975)

The Annunciation

1929-30

Oil on canvas

1617 x 1911 mm

Tate

Presented by Lord Duveen 1931

This summer, Tate Modern will explore the art of the Weimar Republic (1919-33) in a year-long, free display, drawing upon the rich holdings of The George Economou Collection. This presentation of around seventy paintings and works on paper will address the complex paradoxes of the Weimar era, in which liberalisation and anti-militarism flourished in tandem with political and economic uncertainty. These loans offer a rare opportunity to view a range of artworks not ordinarily on public display – some of which have never been seen in the United Kingdom before – and to see a selection of key Tate works returned to the context in which they were originally created and exhibited nearly one hundred years ago.

Although the term ‘magic realism’ is today commonly associated with the literature of Latin America, it was inherited from the artist and critic Franz Roh who invented it in 1925 to describe a shift from the anxious and emotional art of the expressionist era, towards the cold veracity and unsettling imagery of this inter-war period. In the context of growing political extremism, this new realism reflected a more liberal society as well as inner worlds of emotion and magic.

The profound social and political disarray after the First World War and the collapse of the Empire largely brought about this stylistic shift. Berlin in particular attracted a reputation for moral depravity and decadence in the context of the economic collapse. The reconfiguration of urban life was an important aspect of the Weimar moment. Alongside exploring how artists responded to social spaces and the studio, entertainment sites like the cabaret and the circus will be highlighted, including a display of Otto Dix’s enigmatic Zirkus (‘Circus’) print portfolio. Artists recognised the power in representing these realms of public fantasy and places where outsiders were welcomed.

Works by Otto Dix, George Grosz and Max Beckmann perhaps best known today for their unsettling depictions of Weimar life, will be presented alongside the works of under recognised artists such as Albert Birkle, Jeanne Mammen and Rudolf Schlichter, and many others whose careers were curtailed by the end of the Weimar period due to the rise of Nationalist Socialism and its agenda to promote art that celebrated its political ideologies.

The display comes at a pertinent time, in a year of commemoration of the anniversary of the end of the First World War, alongside Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One at Tate Britain and William Kentridge’s new performance for 14-18 Now at Tate Modern entitled The Head and the Load, running from 11-15 July 2018.

Magic Realism is curated by Matthew Gale, Head of Displays and Katy Wan, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. The display is realised with thanks to loans from The George Economou Collection, with additional support from the Huo Family Foundation (UK) Limited.

Press release from the Tate website [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

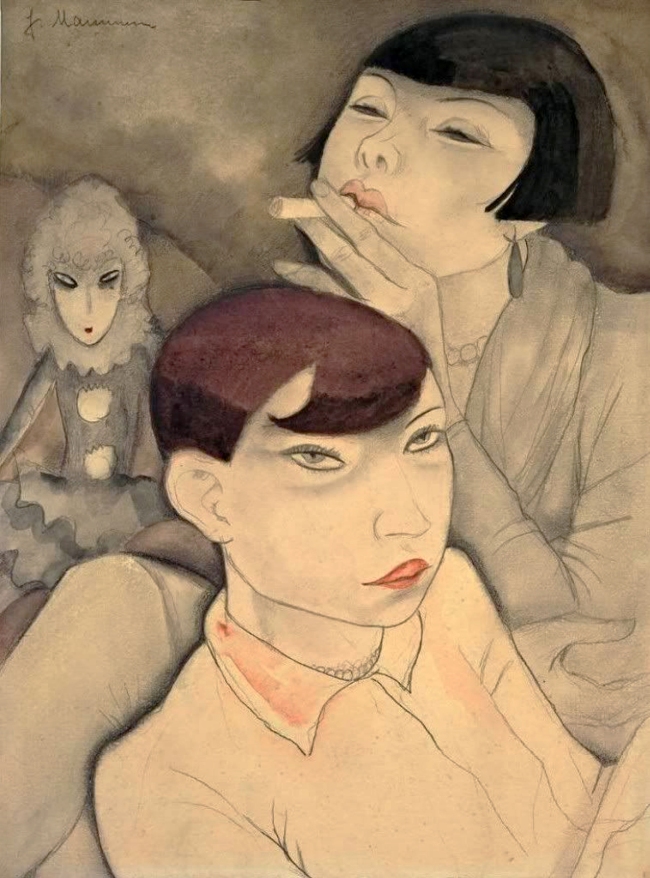

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Boring Dolls (Langweilige Puppen)

1929

Watercolour and graphite on paper mounted on cardboard

384 x 286 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Free room (Brüderstrasse (Zimmer frei))

1930

Watercolour, ink and graphite on vellum

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

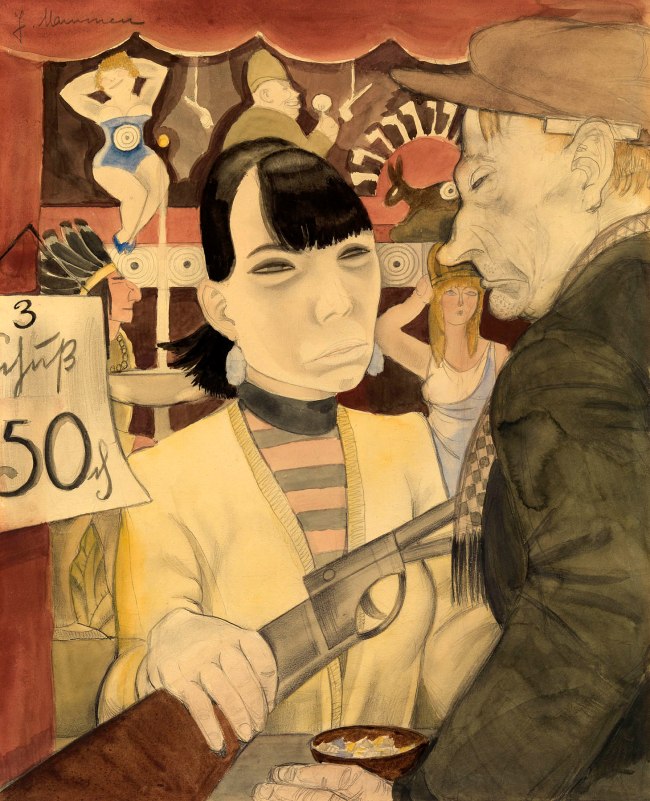

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

At the Shooting Gallery

1929

Watercolour and graphite on vellum

445 x 360 mm

The George Economou Collection

© DACS, 2018

Jeanne Mammen (German, 1890-1976)

Jeanne Mammen (21 November 1890 – 22 April 1976) was a German painter and illustrator of the Weimar period. Her work is associated with the New Objectivity and Symbolism movements. She is best known for her depictions of strong, sensual women and Berlin city life.

… In 1921, Mammen moved into an apartment with her sister in Berlin. This apartment was a former photographer’s studio which she lived in until her death. Aside from Art throughout her life Mammen also was interested in science. She was close friends with Max Delbrück who left Europe and took some of her artwork with him and exhibited them in California. In addition to bringing these art works to be exhibited he also sent Mammen care packages from the United States with art supplies.

In 1930 she had a major exhibition in the Fritz Gurlitt gallery. Over the next two years, at Gurlitt’s suggestion, she created one of her most important works: a series of eight lithographs illustrating Les Chansons de Bilitis, a collection of lesbian love poems by Pierre Louÿs.

In 1933, following her inclusion in an exhibition of female artists in Berlin, the Nazi authorities denounced her motifs and subjects as “Jewish”, and banned her lithographs for Les Chansons de Bilitis. The Nazis were also opposed to her blatant disregard for apparent ‘appropriate’ female submissiveness in her expressions of her subjects. Much of her work also includes imagery of lesbians. The Nazis shut down most of the journals she had worked for, and she refused to work for those that complied with their cultural policies. Until the end of the war she practiced a kind of “inner emigration”. She stopped exhibiting her work and focused on advertising. For a time she also peddled second-hand books from a handcart.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Otto Rudolf Schatz (Austrian, 1900-1961)

Moon Women (Mondfrauen)

1930

Oil paint on canvas

1915 x 1110 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Otto Rudolf Schatz (Austrian, 1900-1961)

Otto Rudolf Schatz was born on January 18, 1900, the son of a post office family in Vienna. From 1915 to 1918 Schatz studied at the Viennese Art Academy under Oskar Strnad and Anton von Kenner. In 1918 his studies were interrupted by military service in the Second World War although he graduated in 1919. During this time the artist’s chosen medium was wood. From 1920 he worked with the painter Max Hevesi who exhibited Schatz’s paintings and woodcuts. Otto Rudolf Schatz also published books with the art critic Arthur Roessler including The Gothic Mood.

In 1923 Schatz became friends with the Viennese gallery owner Otto Kallir who became one of his most important patrons. Kallir continuously presented Schatz’s works in the Neue Galerie. In the same year the Austrian collector Fritz Karpfen published Austrian Art featuring Schatz’s art. The artist’s book of twelve woodcuts was published with a foreword by the art historian Erica Tietze-Conrat. The painter also traveled to Venice in 1923.

In 1924 he had his first collective exhibition in the Neue Galerie. In 1925 Schatz exhibited in the Neue Galerie together with Anton Faistauer, Franz Probst, and Marianne Seeland. In the same year he became a member of the Austrian artists’ association Kunstschau and he provided eight original woodcuts for the publication of a fairytale book Im Satansbruch by Ernst Preczang.

In 1927 Schatz contributed woodcuts to the volume The New Town by the Berlin Büchergilde Gutenberg. From 1928 to 1938 he was a valued member in the Hagenbund in Vienna. In 1929 he produced several illustrations for The Stromverlag among others and for Stefan Zweig’s Fantastic Night and H. G. Wells The Invisible. In 1936 he participated in a collective exhibition with Georg Ehrlich in the Neue Galerie. In 1936 to 1937 Schatz traveled through the United States as well as visited the World Exhibition in Paris. His paintings were seen in exhibition of his New York, in the Neue Galerie, and in the Hagenbund. The artists provided illustrations for the Büchergilde Gutenberg edition of Upton Sinclair’s Co-op.

When the National Socialists gained power in 1938 Schatz was forbidden to work. In 1938 he lived with his Jewish wife Valerie Wittal in Brno and in 1944 in Prague where he painted landscape miniatures. In 1944 Schatz was imprisoned in the Klettendorf labour camp and then transferred to the Graditz and Bistritz concentration camps. In 1946 Schatz returned to Vienna where he was promoted by the cultural politician, city counsellor, and writer Viktor Matejka. In 1946 he became a member of the Vienna Secession. In 1947 Schatz received the prize of the city of Vienna for graphics. In the same year eighteen woodcuts were created for Peter Rosegger’s Jakob der Letzte. In 1949 Scatz’s watercolour series Das war der Prater was published in book form. In 1951 Schatz won the competition for the design of the Vienna Westbahnhof. On April 26, 1961 Otto Rudolf Schatz died of lung cancer in Vienna.

As a graphic artist and painter Otto Rudolf Schatz occupies a leading position in the Austrian inter-war period. His multi-faceted work which moves between Expressionism and New Objectivity, was characterised by a social-critical attitude that gives his work historical significance. The artist’s works are now found in numerous collections including the Belvedere in Vienna, the Vienna Museum, and the Hans Schmid Private Foundation.

Anonymous text. “Biography,” on the Otto Rudolf Schatz website Nd [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

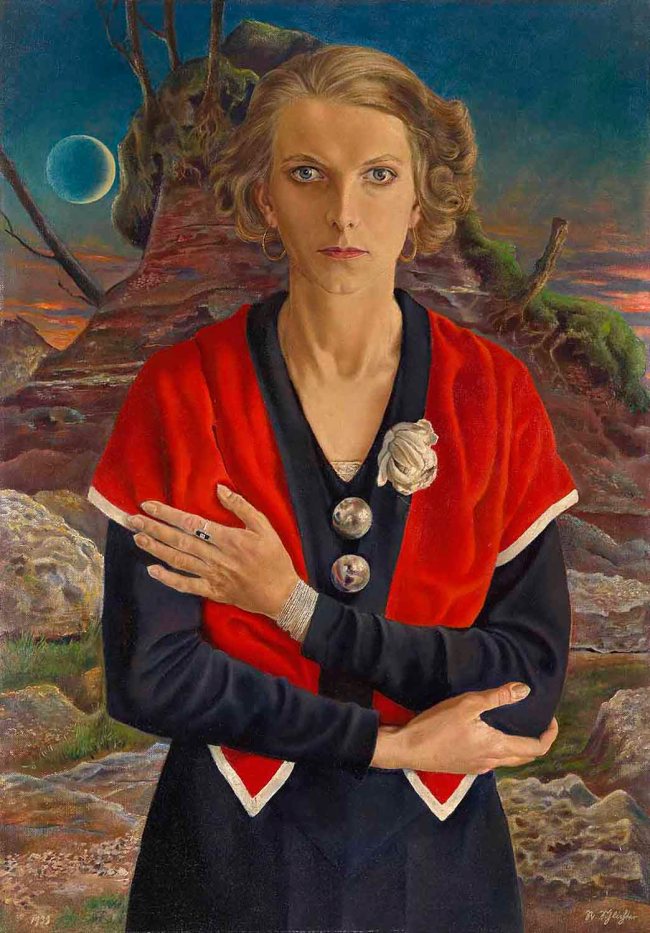

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Lady with Red Scarf (Speedy with the Moon) (Frauenportrait (Speedy))

1933

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Rudolf Schlichter (German, 1890-1955)

Rudolf Schlichter (or Rudolph Schlichter) (December 6, 1890 – May 3, 1955) was a German artist and one of the most important representatives of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement.

Schlichter was born in Calw, Württemberg. After an apprenticeship as an enamel painter at a Pforzheim factory he attended the School of Arts and Crafts in Stuttgart. He subsequently studied under Hans Thoma and Wilhelm Trübner at the Academy in Karlsruhe. Called for military service in World War I, he carried out a hunger strike to secure early release, and in 1919 he moved to Berlin where he joined the Communist Party of Germany and the “November” group. He took part in a Dada fair in 1920 and also worked as an illustrator for several periodicals.

A major work from this period is his Dada Roof Studio, a watercolour showing an assortment of figures on an urban rooftop. Around a table sit a woman and two men in top hats. One of the men has a prosthetic hand and the other, also missing a hand, appears on closer scrutiny to be mannequin. Two other figures in gas masks may also be mannequins. A child holds a pail and a woman wearing high button shoes (for which Schlichter displayed a marked fetish) stands on a pedestal, gesturing inexplicably.

In 1925 Schlichter participated in the “Neue Sachlichkeit” exhibit at the Mannheim Kunsthalle. His work from this period is realistic, a good example being the Portrait of Margot (1924) now in the Berlin Märkisches Museum. It depicts a prostitute who often modelled for Schlichter, standing on a deserted street and holding a cigarette.

When Adolf Hitler took power, bringing to an end the Weimar period, his activities were greatly curtailed. In 1935 he returned to Stuttgart, and four years later to Munich. In 1937 his works were seized as degenerate art, and in 1939 the Nazi authorities banned him from exhibiting. His studio was destroyed by Allied bombs in 1942.

At the war’s end, Schlichter resumed exhibiting works. His works from this period were surrealistic in character. He died in Munich in 1955.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Sergius Pauser (Austrian, 1896-1970)

Self-Portrait with Mask

1926

Oil paint on canvas

600 x 730 mm

The George Economou Collection

© Angela Pauser and Wolfgang Pauser

Sergius Pauser (Austrian, 1896-1970)

Sergius Pauser, who was born in Vienna on 28 December 1896, represents the prototype of this generation of artists. As a painter, he enjoyed the recognition of his contemporaries and as a much sought-after artist who was able to earn his living with his paintings. He was never a revolutionary but rather a “gentleman of the Viennese order”, who sought to capture moods and atmosphere in his paintings. The writer Thomas Bernhard (1931-1989) wrote of Pauser: “Sergius Pauser uttered thoughts about people – Adalbert Stifter, for example – that I have never heard before or since; he succeeded in revealing the most concealed corners of poetic sensitivity; he was a tender and vigilant diviner on the landscape of world literature, a philosopher and an artist through and through.” And yet a painter like Sergius Pauser is barely known today; only a few of his works hang in Austrian galleries and many of his paintings cannot be traced due to the emigration of their owners.

Dr. Isabella Ackerl. “Sergius Pauser (1896-1979),” on the Sergius Pauser website Nd [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

Hans Grundig (German, 1901-1958)

Girl with Pink Hat

1925

Oil paint on cardboard

704 x 500 mm

The George Economou Collection

© DACS, 2018

Hans Grundig (German, 1901-1958)

Hans Grundig (February 19, 1901 – September 11, 1958) was a German painter and graphic artist associated with the New Objectivity movement.

He was born in Dresden and, after an apprenticeship as an interior decorator, studied in 1920–1921 at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. He then studied at the Dresden Academy from 1922 to 1923. During the 1920s his paintings, primarily portraits of working-class subjects, were influenced by the work of Otto Dix. Like his friend Gert Heinrich Wollheim, he often depicted himself in a theatrical manner, as in his Self-Portrait during the Carnival Season (1930).

He had his first solo exhibition in 1930 at the Dresden gallery of Józef Sandel. He made his first etchings in 1933.

Politically anti-fascist, he joined the German Communist Party in 1926, and was a founding member of the arts organisation Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler in Dresden in 1929.

Following the fall of the Weimar Republic, Grundig was declared a degenerate artist by the Nazis, who included his works in the defamatory Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich in 1937. He expressed his antagonism toward the regime in paintings such as The Thousand Year Reich (1936). Forbidden to practice his profession, he was arrested twice – briefly in 1936, and again in 1938, after which he was interned in Sachsenhausen concentration camp from 1940 to 1944.

In 1945 he went to Moscow, where he attended an anti-fascist school. Returning to Berlin in 1946, he became a professor of painting at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. In 1957 he published his autobiography, Zwischen Karneval und Aschermittwoch (“Between Shrovetide carnival and Ash Wednesday”). He was awarded the Heinrich Mann Prize in Berlin in 1958, the year of his death.

Text from the Wikipedia website

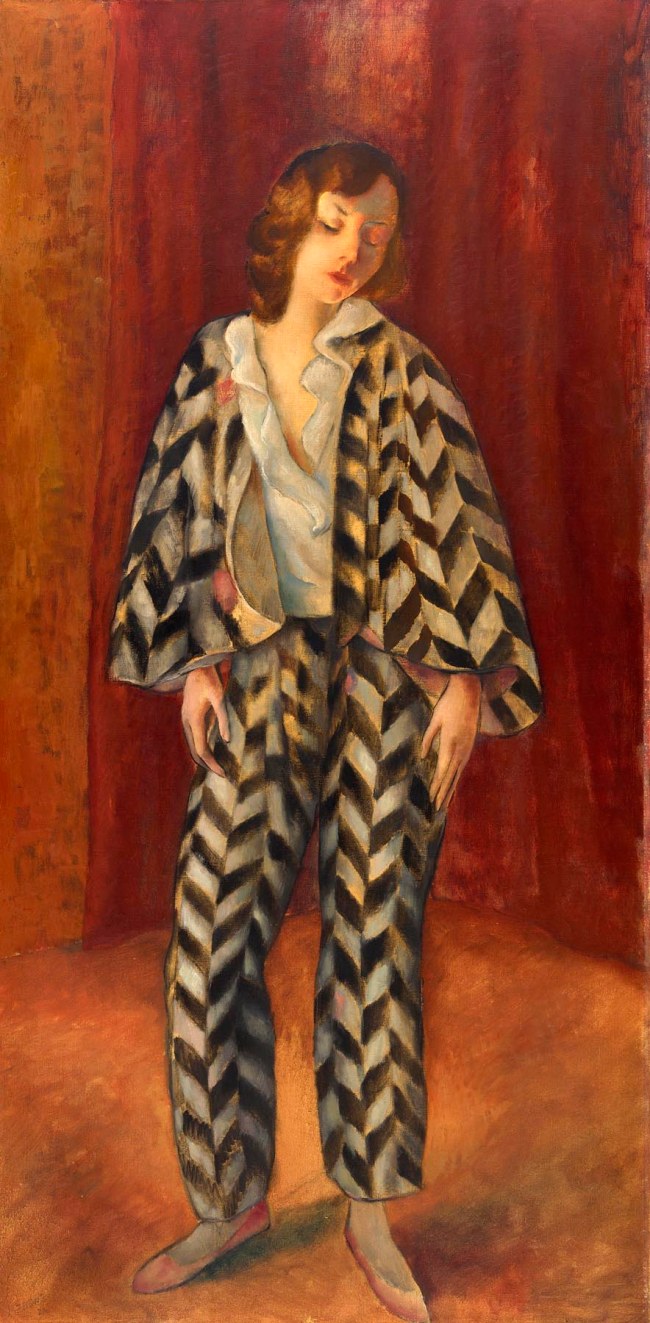

Josef Eberz (German, 1880-1942)

Dancer (Beatrice Mariagraete)

1923

Oil paint on canvas

1580 x 785 mm

The George Economou Collection

Josef Eberz died in utter loneliness on 27 August 1942, his apartment with his studio burned out in a bombing raid.

Conrad Felixmüller (German, 1897-1977)

Portrait of Ernst Buchholz

1921

Oil paint on canvas

900 x 750 mm

The George Economou Collection

© DACS, 2018

Conrad Felixmüller (German, 1897-1977)

Conrad Felixmüller (21 May 1897 – 24 March 1977) was a German expressionist painter and printmaker. Born in Dresden as Conrad Felix Müller, he chose Felixmüller as his nom d’artiste.

He attended drawing classes at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts in 1911-1912 before studying under Carl Bantzer at the Dresden Academy of Art. In 1917 he performed military service as a medical orderly, and became a founding member of the Dresden Expressionist group Expressionistische Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dresden. He achieved his earliest success as a printmaker. Felixmüller was a member of the Communist Party of Germany from 1918 to 1922. He published many woodcuts and drawings in left-wing magazines, and remained a prolific printmaker throughout his career. He was a close friend of the composer Clemens Braun of whom he produced a number of portraits and a woodcut depicting him on his deathbed.

He was one of the youngest members of the New Objectivity movement. His paintings often deal with the social realities of Germany’s Weimar Republic. He was mentor to the German Expressionist Otto Dix.

Felixmüller’s work became more objective and restrained after the mid-1920s. He wrote in 1929:

“It has become increasingly clear to me that the only necessary goal is to depict the direct, simple life which one has lived oneself, also involving the design of colour as painting – in the manner in which it was cultivated by the Old Masters for centuries, until Impressionism and Expressionism, infected by the technical and industrial delusions of grandeur, rejected every affinity for tradition, ability and results, committing harakiri.”

In the 1930s, many of his works were seized as degenerate art by the Nazis, and destroyed. In 1944, his studio in Berlin was bombed, resulting in more losses of his works. From 1949 to 1962 Felixmüller taught at the University of Halle. He died in the Berlin suburb of Zehlendorf.

Text from the Wikipedia website

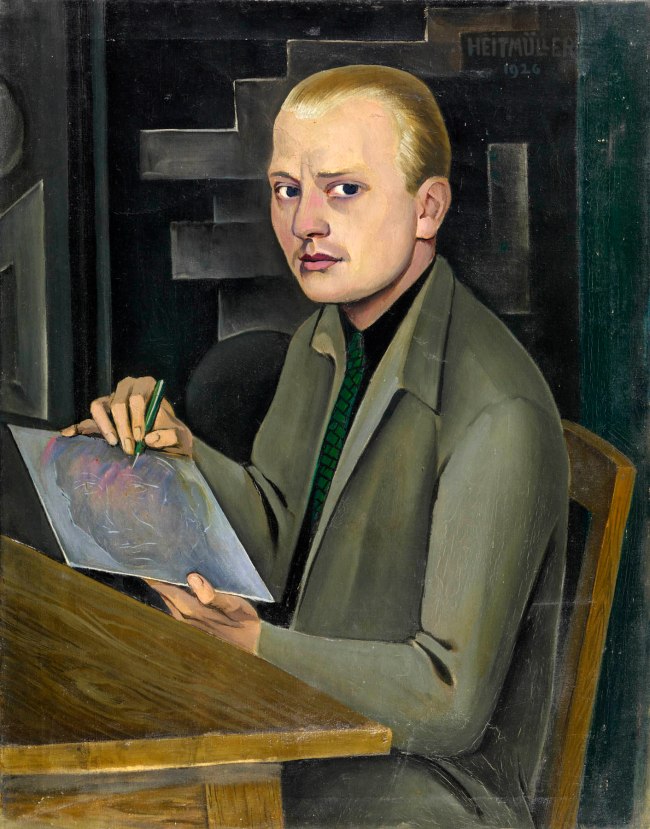

August Heitmüller (German, 1873-1935)

Self-Portrait

1926

Oil paint on canvas

900 x 705 mm

The George Economou Collection

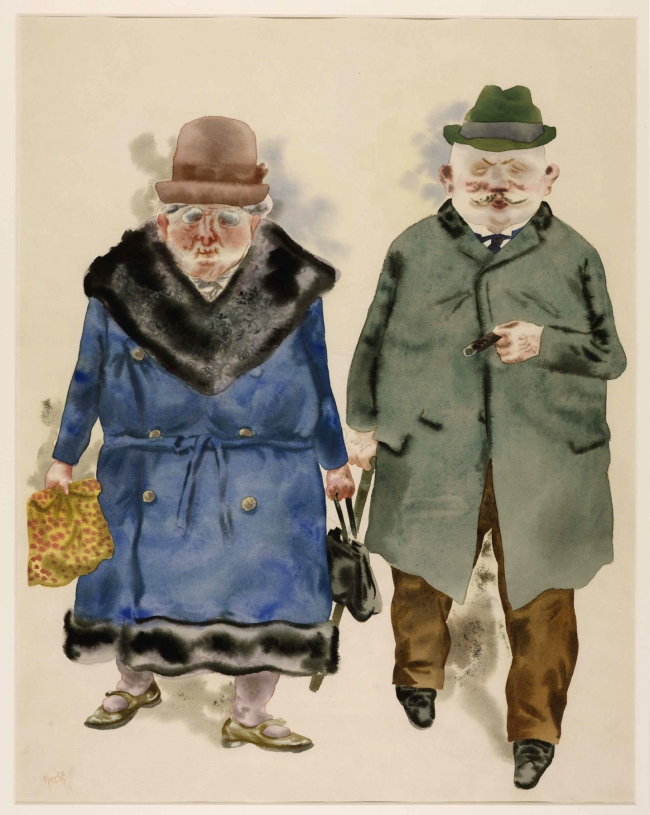

George Grosz (German, 1893-1959)

A Married Couple

1930

Watercolour, gouache, pen and ink on paper

505 x 440 mm

The George Economou Collection

© Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018

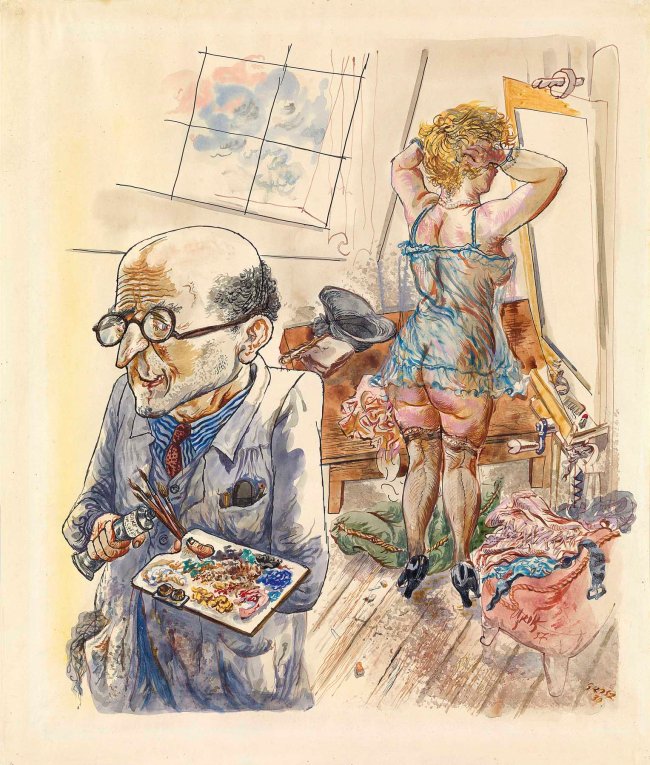

George Grosz (German, 1893-1959)

Self-Portrait with Model in the Studio

1930-1937

Watercolour on paper

660 x 473 mm

Tate

© Estate of George Grosz, Princeton, N.J. 2018

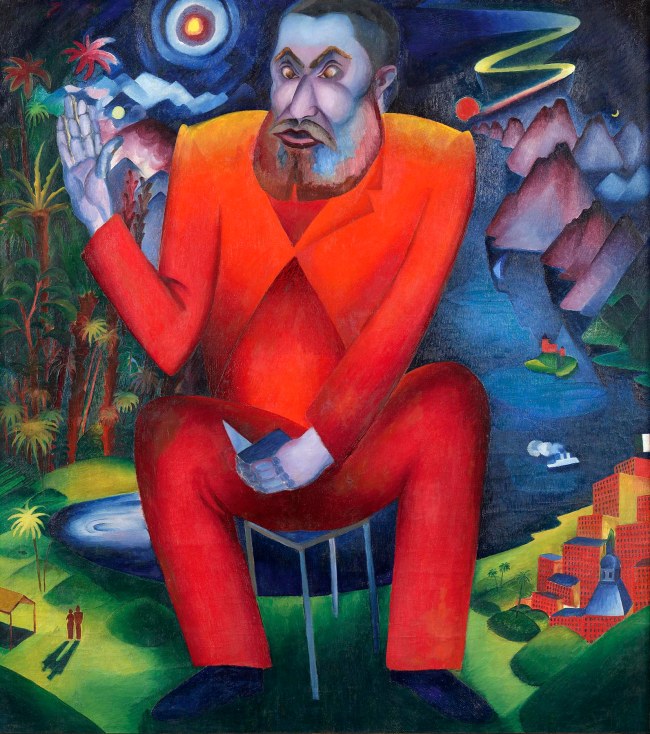

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970)

The Poet Däubler (Der Dichter Däubler)

1917

Oil paint on canvas

1810 x 1603 mm

The George Economou Collection

On short term loan

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (German, 1894-1970)

Heinrich Maria Davringhausen (21 October 1894 – 13 December 1970) was a German painter associated with the New Objectivity.

Davringhausen was born in Aachen. Mostly self-taught as a painter, he began as a sculptor, studying briefly at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts before participating in a group exhibition at Alfred Flechtheim’s gallery in 1914. He also traveled to Ascona with his friend the painter Carlo Mense that year. At this early stage his paintings were influenced by the expressionists, especially August Macke.

Exempted from military service in World War I, he lived in Berlin from 1915 to 1918, forming friendships with George Grosz and John Heartfield. In 1919 he had a solo exhibition at Hans Goltz’ Galerie Neue Kunst in Munich, and exhibited in the first “Young Rhineland” exhibition in Düsseldorf. Davringhausen became a member of the “Novembergruppe” and gained some prominence among the artists representing a new tendency in German art of the postwar period. He was asked to take part in the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) exhibition in Mannheim which brought together many leading “post-expressionist” artists, including Grosz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Alexander Kanoldt and Georg Schrimpf.

Davringhausen went into exile with the fall of the Weimar republic in 1933, first going to Majorca, then to France. In Germany approximately 200 of his works were removed from public museums by the Nazis on the grounds that they were degenerate art. Prohibited from exhibiting, Davringhausen was interned in Cagnes-sur-Mer but fled to Côte D’Azur. In 1945 however he returned to Cagnes-sur-Mer, a suburb of Nice, where he remained for the rest of his life. He worked as an abstract painter under the name Henri Davring until his death in Nice in 1970.

Perhaps the best-known work from Davringhausen’s New Objectivity period is Der Schieber (The Black-Marketeer), a Magic realist painting of 1920-1921, which is in the Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf im Ehrenhof. Painted in acidulous colours, it depicts a glowering businessman seated at a desk in a modern office suite that foreshortens dramatically behind him. Although Davringhausen rarely presented social criticism in his work, in Der Schieber “the artist created the classic pictorial symbol of the period of inflation that was commencing”.

Much of Davringhausen’s work was deposited in 1989 in the Leopold Hoesch museum in Düren, which has subsequently organised several exhibitions of his pictures, above all those from the later period.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Albert Birkle (German, 1900-1986)

The Acrobat Schulz V

1921

Oil paint on canvas

920 x 607 mm

The George Economou Collection

© DACS, London 2018

Albert Birkle (German, 1900-1986)

Albert Birkle was born in Charlottenburg, then an independent city and since 1920 part of Berlin. His grandfather on his mother’s side, Gustav Bregenzer, and his father, Carl Birkle, both were painters, originally from Swabia. Albert Birkle was trained as a decorative painter in his father’s firm. From 1918 to 1924, he studied at the Hochschule für die bildenden Künste / College of Fine Arts, a predecessor of today’s Universität der Künste Berlin. Birkle developed a unique style informed by expressionism and New Objectivity / Neue Sachlichkeit. His subjects were lonely, mystic landscapes, typical scenes of Berlin of the 20’s and 30’s, such as scenes from Tiergarten Park, bar scenes etc., character portraits, and religious scenes. In his style of portrait painting he was often compared to Otto Dix and George Grosz.

In 1927, Birkle had his first one man show in Berlin, which turned out to be very successful. He decided to turn down a professorship at the Koenigsberg Acadamy of Arts in order to continue to work independently as an artist and to dedicate himself to assignments in the field of church decoration, where he had become a specialist. As National Socialism was on its way to power, Birkle moved to Salzburg, Austria in 1932. Nevertheless, he represented Germany at the Venice Biennale as late as 1936. In 1937, his artwork was declared to be “entarted”, his works were removed from public collections, and a painting ban was imposed on him.

In 1946, Birkle received Austrian citizenship. In the post-war year, he made a living painting religious frescos for various churches and doing oil paintings. In his final year, he more and more returned back to his Berlin themes of the 20’s and 30’s.

Text from the Albert Birkle website [Online] Cited 23/06/2019

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

United Kingdom

Opening hours:

Daily 10.00 – 18.00

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bohemians [Willi Bongard, Gottfried Brockmann]' c. 1922-5, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Bohemians [Willi Bongard, Gottfried Brockmann]' c. 1922-5, printed 1990](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/august-sander-bohemians-willi-bongard-gottfried-brockmann-c-1922e280935-web.jpg?w=840)

![August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Photographer [August Sander]' 1925, printed 1990 August Sander (German, 1876-1964) 'Photographer [August Sander]' 1925, printed 1990](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2017/09/august_sander_august_sander_1925-web.jpg?w=650&h=924)

You must be logged in to post a comment.