Exhibition dates: –

Curator: Dr Karin Schick

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Frühe Menschen – Urlandschaft

Early humans – primeval landscape

1939 (revised 1947/48)

Gouache, watercolour and ink

49.8 x 64.5cm

Courtesy of Daxer & Marschall, München

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Daxer & Marschall, München

If ever there were a time in history that I would like to go back to and work as an artist, it is most definitely the interwar years in Paris, or Berlin up until 1933 when the Nazis took control of German culture. I would have revelled in the freedom of expression, freedom of identity, sexuality, gender, New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), New Woman, news ways of experimentation, and new ways of thinking about the human condition (Jung, Freud, Benjamin). I would have been empowered as an artist to push the boundaries of conservative society, to break prescriptive and outdated cultural norms.

And so with Max Beckmann. There is a basic and fundamental feeling to his paintings, a primordial feeling, in which the artist breaks the boundaries of the taboo fully aware that there may be consequences for doing so. In his paintings Beckmann crafts his stories of passion, desire, mythology and the jouissance of everyday life, expressed through ever more delineated black-outlined caricatures which feature elongated claw-like hands, distorted bodies and mobile, multiple perspectives (see Das Bad (The bathroom) 1930, below). These paintings so generate and compose their own existence (their presence) – one which opposes conventional classical portraiture – that the Nazis labelled them De/generate Art. “Although not Jewish, he was beleaguered by the Nazis, who dismissed him from his teaching post in Frankfurt in 1933 and removed his “degenerate” work from public collections.” (NY Times)

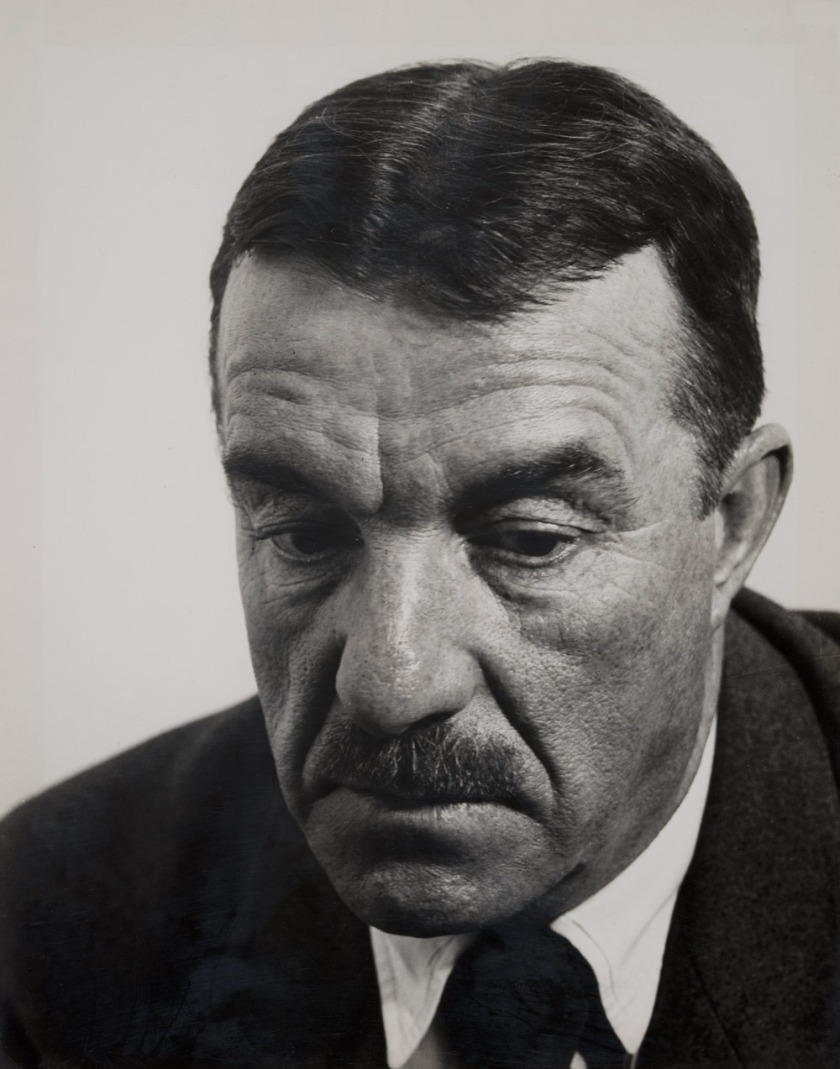

As with any artist, the journey is the key to the development of the work. Look at the assured, slightly fey, well-dressed man in Beckmann’s classical Self-portrait, Florence (1907, below) and then compare it to his Self-Portrait with Horn (1938, below). In the first self-portrait Beckmann is aged 23, seemingly untouched by the vicissitudes of life, debonair, staring straight at the camera, ooh I mean mirror – sorry, canvas – the mouth held in a small thin line, eyes almost blank, cigarette in nonchalantly curled hand. Thirty one years later, age/d 54, Beckmann’s features (having lived through the desolation of the First World War, famine, revolution, the Great Depression, assassination, violence) are gnarled and wizened, his expression grim, his clothing that of a concentration camp inmate, his horn silent and occluded, reminding me of the hearing trumpet of the composer Beethoven. Unable to hear, not wanting to face, the clamour of the onrushing maelstrom.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Hamburger Kunsthalle for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Self-portrait, Florence

1907

Oil on canvas

98 x 90cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle Dauerleihgabe Nachlass Peter und Maja Beckmann

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk

Foto: Elke Walford

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Self-Portrait with Horn

1938

Oil on canvas

101 x 110cm

Neue Galerie New York and Private Collection

Used under fair use conditions

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Adam and Eve

1917

Oil on canvas

79.8 x 56.7cm

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

Erworben mit Unterstützung der Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© bpk / Nationalgalerie, SMB

Foto: André van Linn

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Bildnis einer Rumänin (Bildnis Frau Dr. Heidel)

Portrait of a Romanian (Portrait of Dr. Heidel)

1922

Oil on canvas

100 x 65cm

Dauerleihgabe der Stiftung Hamburger Kunstsammlungen

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© SHK / Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk

Foto: Elke Walford

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Bildnis Käthe von Porada (Portrait of Käthe von Porada)

1924

Oil on canvas

120 x 43cm

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK

Foto: U. Edelmann

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Bildnis Ludwig Berger (Portrait of Ludwig Berger)

1945

Oil on canvas

135.6 x 90.9cm

Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Das Bad (The bathroom)

1930

Oil on canvas

174.9 x 121.3cm

Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May

Max Beckmann: feminine-masculine is the first exhibition to examine in detail the often contradictory roles played by women and men in the works of Max Beckmann (1884-1950), one of the great artists of modernism and a potent interpreter of his times. With some 140 paintings, sculptures and works on paper, the show demonstrates the impressive breadth of this subject area in the artist’s oeuvre while enabling viewers to come to a deeper understanding of Beckmann’s multifaceted art. Important loans from public and private collections in Germany and abroad – including the Max Beckmann Estate, the Städel Museum, Frankfurt on the Main, the Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri / USA, and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam – supplement the Hamburger Kunsthalle’s extensive Beckmann holdings.

The exhibition explores both the historical significance of Beckmann’s paintings as well as their relevance in today’s world. His incisive self-portraits, his double portraits with his wives, the stately likenesses of his sponsors and patrons as well as his mythological and biblical figure paintings compellingly evoke basic constants of human togetherness: desire, devotion and conflict, power and powerlessness, the urge for freedom and the longing to become one with another human being.

Beckmann both exaggerated and blurred gender roles; he discovered tenderness in both female and male figures, power in the heroine as well as the hero. Fascinated by the myths of different cultures, he was familiar with the age-old notion that male and female once split off from a single, androgynous gender and are doomed to yearn forever to be reunified. The artist also read and commented on contemporary writings by Carl Gustav Jung and Otto Weininger that are still the subject of frequent discussion today and which explain individuality as a combination of female and male elements. Beckmann nonetheless liked to style himself as a manfully resolute interpreter of the world, an image that to this day dominates the reception of his work, hindering a more open understanding of his many-layered art.

Accompanying the exhibition are a richly illustrated scholarly catalogue (Prestel Verlag, Munich), an audio guide and regular theme-based guided tours (Saturdays at 3 pm). The museum education offerings uncover multiple perspectives on Beckmann’s art and enable visitors to take part in an on-site dialogue between the curator and further experts (for example on gender research). On 15 January 2021, the Kunsthalle will also host a public, international symposium on Beckmann’s multifaceted examination of the topic of “femaleness and masculinity”.

The exhibition Max Beckmann: feminine-masculine is a true highlight on the Hamburger Kunsthalle’s agenda for 2020. It represents a further instalment in a series of highly acclaimed exhibitions devoted to Beckmann’s art, including Self-Portraits (1993), Landscape as Stranger (1998) and Max Beckmann: The Still Lifes (2014).

Press release from the Hamburger Kunsthalle

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Doppelbildnis (Max und Mathilde Beckmann)

Double portrait (Max and Mathilde Beckmann)

1941

Oil on canvas

193.5 x 89cm

Collection Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Messingstadt (City of Brass)

1944

Oil on canvas

115 x 150cm

Saarlandmuseum – Moderne Galerie, Saarbrücken, Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Saarlandmuseum – Moderne Galerie, Saarbrücken, Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz

Foto: Tom Gundelwein

Max Beckmann addresses the relationship between man and woman as the starting point for the repetitive torments of human existence. In this question too, he is inspired by the archetype of the fairy tale Messingstadt “Brass City”. (From “The Thousand and One Nights” or “Arabian nights”) In this story it is the hero Musa who manages to get inside the brass city. He enters a palace where he discovers a girl as “beautiful as the shining sun”. At the same time, he realises that it’s just her lifeless body.

Note: The Thousand and One Nights, also called The Arabian Nights, Arabic Alf laylah wa laylah, collection of largely Middle Eastern and Indian stories of uncertain date and authorship. Its tales of Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sindbad the Sailor have almost become part of Western folklore, though these were added to the collection only in the 18th century in European adaptations.

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Odysseus and Calypso

1943

Oil on canvas

150 x 115.5cm

Hamburger Kunsthalle

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Hamburger Kunsthalle / bpk

Foto: Elke Walford

Max Beckmann

Max Carl Friedrich Beckmann (February 12, 1884 – December 27, 1950) was a German painter, draftsman, printmaker, sculptor, and writer. Although he is classified as an Expressionist artist, he rejected both the term and the movement. In the 1920s, he was associated with the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), an outgrowth of Expressionism that opposed its introverted emotionalism. His work became full of horrifying imagery and distorted forms with combination of brutal realism and social criticism.

Life

Max Beckmann was born into a middle-class family in Leipzig, Saxony. From his youth he pitted himself against the old masters. His traumatic experiences of World War I, in which he volunteered as a medical orderly, coincided with a dramatic transformation of his style from academically correct depictions to a distortion of both figure and space, reflecting his altered vision of himself and humanity.

He is known for the self-portraits painted throughout his life, their number and intensity rivalled only by those of Rembrandt and Picasso. Well-read in philosophy and literature, Beckmann also contemplated mysticism and theosophy in search of the “Self”. As a true painter-thinker, he strove to find the hidden spiritual dimension in his subjects (Beckmann’s 1948 Letters to a Woman Painter provides a statement of his approach to art).

Beckmann enjoyed great success and official honours during the Weimar Republic. In 1925 he was selected to teach a master class at the Städelschule Academy of Fine Art in Frankfurt. Some of his most famous students included Theo Garve, Leo Maillet and Marie-Louise von Motesiczky. In 1927 he received the Honorary Empire Prize for German Art and the Gold Medal of the City of Düsseldorf; the National Gallery in Berlin acquired his painting The Bark and, in 1928, purchased his Self-Portrait in Tuxedo. By the early 1930s, a series of major exhibitions, including large retrospectives at the Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim (1928) and in Basel and Zurich (1930), together with numerous publications, showed the high esteem in which Beckmann was held.

His fortunes changed with the rise to power of Adolf Hitler, whose dislike of Modern Art quickly led to its suppression by the state. In 1933, the Nazi government called Beckmann a “cultural Bolshevik” and dismissed him from his teaching position at the Art School in Frankfurt. In 1937 the government confiscated more than 500 of his works from German museums, putting several on display in the notorious Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. The day after Hitler’s radio speech about degenerate art in 1937, Beckmann left Germany with his second wife, Quappi, for the Netherlands.

For ten years, Beckmann lived in self-imposed exile in Amsterdam, failing in his desperate attempts to obtain a visa for the United States. In 1944 the Germans attempted to draft him into the army, although the sixty-year-old artist had suffered a heart attack. The works completed in his Amsterdam studio were even more powerful and intense than the ones of his master years in Frankfurt. They included several large triptychs, which stand as a summation of Beckmann’s art.

In 1948, Beckmann moved to the United States. During the last three years of his life, he taught at the art schools of Washington University in St. Louis (with the German-American painter and printmaker Werner Drewes) and the Brooklyn Museum. He came to St. Louis at the invitation of Perry T. Rathbone, who was director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. Rathbone arranged for Washington University in St. Louis to hire Beckmann as an art teacher, filling a vacancy left by Philip Guston, who had taken a leave. The first Beckmann retrospective in the United States took place in 1948 at the City Art Museum, Saint Louis. In St. Louis, Morton D. May became his patron and, already an avid amateur photographer and painter, a student of the artist. May later donated much of his large collection of Beckmann’s works to the St. Louis Art Museum. Beckmann also helped him learn to appreciate Oceanian and African art. After stops in Denver and Chicago, he and Quappi took an apartment at 38 West 69th Street in Manhattan. In 1949 he obtained a professorship at the Brooklyn Museum Art School.

He suffered from angina pectoris and died after Christmas 1950, struck down by a heart attack at the corner of 69th Street and Central Park West in New York, not far from his apartment building. As the artist’s widow recalled, he was on his way to see one of his paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Beckmann had a one-man show at the Venice Biennale of 1950, the year of his death.

Themes

Unlike several of his avant-garde contemporaries, Beckmann rejected non-representational painting; instead, he took up and advanced the tradition of figurative painting. He greatly admired not only Cézanne and Van Gogh, but also Blake, Rembrandt, and Rubens, as well as Northern European artists of the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, such as Bosch, Bruegel, and Matthias Grünewald. His style and method of composition are partially rooted in the imagery of medieval stained glass.

Engaging with the genres of portraiture, landscape, still life, and history painting, his diverse body of work created a very personal but authentic version of modernism, one with a healthy deference to traditional forms. Beckmann reinvented the religious triptych and expanded this archetype of medieval painting into an allegory of contemporary humanity.

From his beginnings in the fin de siècle to the period after World War II, Beckmann reflected an era of radical changes in both art and history in his work. Many of Beckmann’s paintings express the agonies of Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Some of his imagery refers to the decadent glamour of the Weimar Republic’s cabaret culture, but from the 1930s on, his works often contain mythologised references to the brutalities of the Nazis. Beyond these immediate concerns, his subjects and symbols assume a larger meaning, voicing universal themes of terror, redemption, and the mysteries of eternity and fate.

His Self-Portrait with Horn (1938), painted during his exile in Amsterdam, demonstrates his use of symbols. Musical instruments are featured in many of his paintings; in this case, a horn that the artist holds as if it were a telescope by which he intends to explore the darkness surrounding him. The tight framing of the figure within the boundaries of the canvas emphasise his entrapment. Art historian Cornelia Stabenow terms the painting “the most melancholy, but also the most mystifying, of his self-portraits”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Venus – Mars

1945

India ink and watercolour

36,2 x 19.5cm

Private collection

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Privatbesitz

Max Beckmann (German, 1884-1950)

Zwei Frauen (in Glastür)

Two women (in glass door)

1940

Oil on canvas

80 x 61cm

Museum Ludwig, Köln

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020

© Foto: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

Hamburger Kunsthalle

Glockengießerwall 20095 Hamburg

Phone: +49 (0)40-428 131 204

Opening hours:

Tuesdays to Sundays 10am – 6pm

Thursdays 10am – 9pm

Closed Mondays

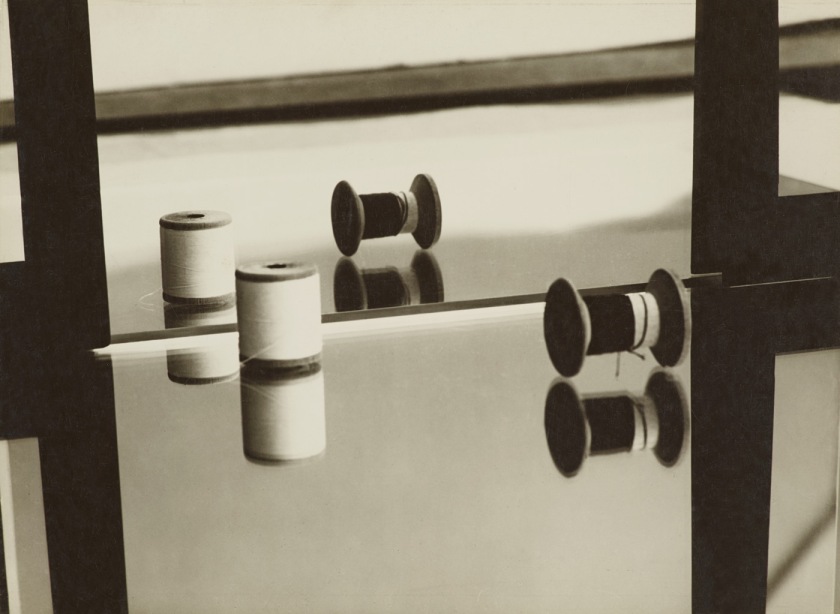

![Florence Henri. 'Composition abstraite [Still-life composition]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_08_compositionabstraite-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Mannequin de tailleur [Tailor's mannequin]' 1930-1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_05__mannequindetailleur-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Composition Nature morte [Still-life composition]' 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_10_compositionnaturemorte-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Pont [Bridge]' 1930-1935](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_21_pont-web.jpg?w=840)

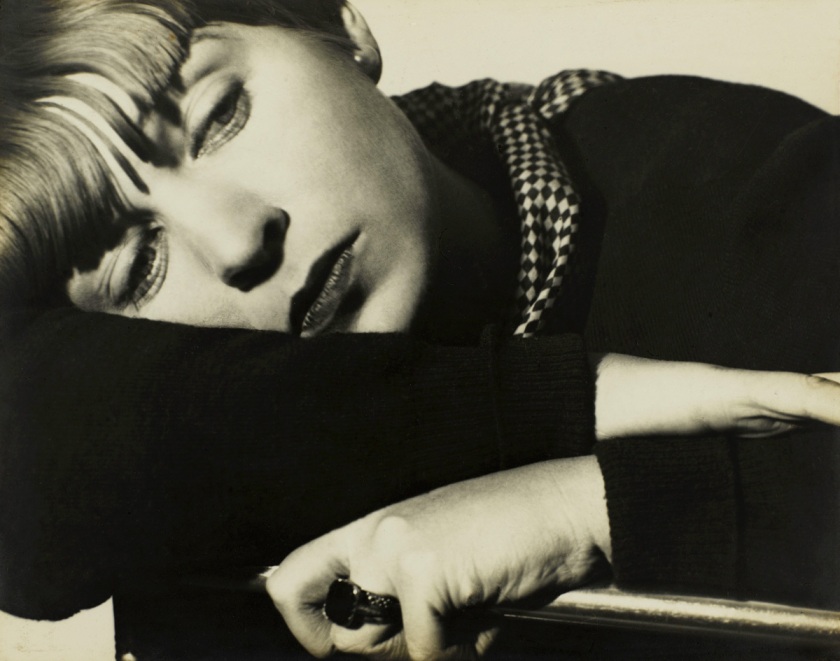

![Florence Henri. 'Autoportrait [Self-portrait]' 1928](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_01_autoportrait-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Femme aux cartes [Woman with cards]' 1930](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_11_femmeauxcartes-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Fenêtre [Window]' 1929](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_06_fenetre-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Composition Nature morte [Still-life composition]' 1931](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_09_compositionnaturemorte-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Composition Nature morte [Still-life composition]' c. 1933](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_17_compositionnaturemorte-web.jpg?w=840)

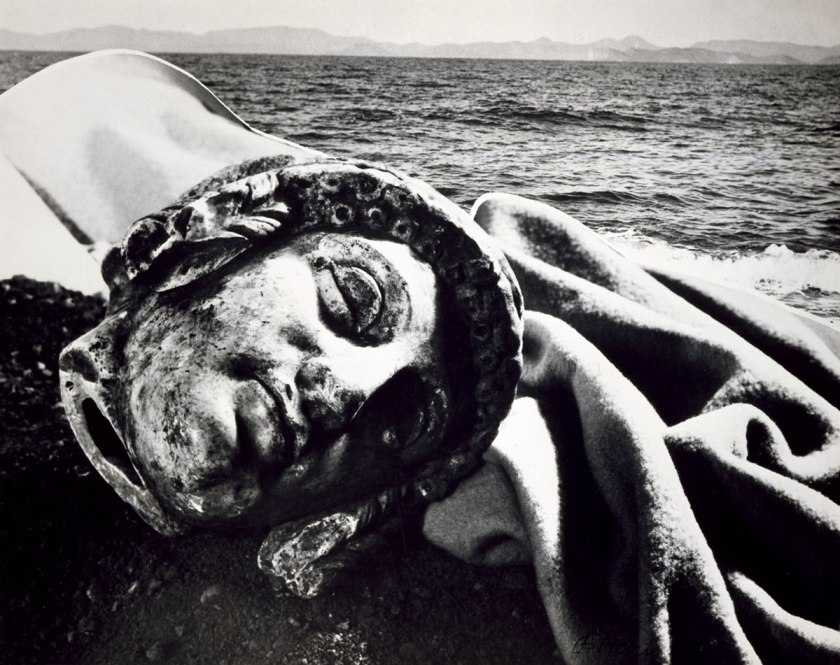

![Florence Henri (New York 1893 - Compiègne 1982) 'Bretagne [Brittany]' 1937-1940](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_19_bretagne-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Structure (intérieur du Palais de l'Air, Paris, Exposition Universelle) [Structure (Interior of the Palais de l'Air, Paris, World's Fair)]' 1937](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_20_structure-web.jpg?w=840)

![Florence Henri. 'Autoportrait [Self-portrait]' 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/florencehenri_18_autoportrait-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.