La llum negra. Tradicions secretes en l’art des dels anys cinquanta

Exhibition dates: 16th May – 21st October 2018

Curator: Enrique Juncosa

Artists: Carlos Amorales / Kenneth Anger / Antony Balch / Jordan Belson / Wallace Berman / Forrest Bess / Joseph Beuys / William S. Burroughs / Marjorie Cameron / Francesco Clemente / Bruce Conner / Aleister Crowley / René Daumal / Gino de Dominicis / Louise Despont / Nicolás Echevarría / Robert Frank / João Maria Gusmão + Pedro Paiva / Brion Gysin / Jonathan Hammer / Frieda Harris / Derek Jarman / Jess / Alejandro Jodorowsky / Joan Jonas / Carl Gustav Jung / Matías Krahn / Wolfgang Laib / LeonKa / Goshka Macuga / Agnes Martin / Chris Martin / Henri Michaux / Grant Morrison / Tania Mouraud / Barnett Newman / Joan Ponç / Genesis P-Orridge / Sun Ra / Harry Smith / Rudolf Steiner / Philip Taaffe / Antoni Tàpies / Fred Tomaselli / Suzanne Treister / Vaccaro – Brookner / Ulla von Brandenburg / Terry Winters / Zush

Leon Ka – La llum negra – Mural

The mural at the entrance of the exhibition Black Light created by the artist Leon Ka, represents some of the symbols of ocultism, magic, and the mysticism of spirituality.

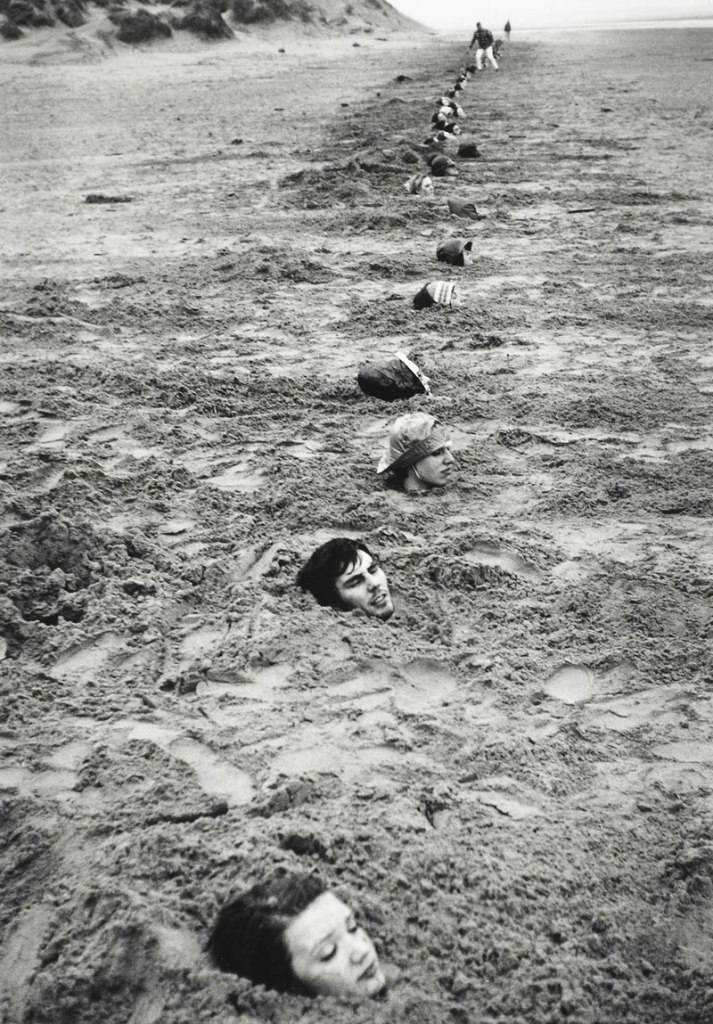

I love these eclectic exhibitions on unusual topics. Having studied a little Georges Gurdjieff, Carl Jung, Robert Johnson, Joseph Campbell and Carlos Castaneda to name just a few, I immersed myself in their spiritual, psychedelic and counterculture world. I had scarification done on my arm in 1992 which was one of the most spiritual rights of passage I have ever experienced in my life (see photograph below).

To be different, to explore that difference in art, is to violate the taboo of control – of adherence to the norm – that emotion which controls how we think, feel, act and create. As Georges Bataille observes,

“”The taboo is there in order to be violated.” This proposition is not the wager it looks like at first but an accurate statement of an inevitable connection between conflicting emotions. When a negative emotion has the upper hand we must obey the taboo. When a positive emotion is in the ascendant we violate it. Such a violation will not deny or suppress the contrary emotion, but justify it and arouse it.”1

An “understanding of the text (writing, art, music, etc.) as ‘social space’,” say Barthes, “activates a broad intertextuality and a productive plurality of meanings and signifying/interpretive gestures that escape the reduction of knowledge to fixed, monological re-presentations, or presences.” What he is saying here is that there is no singular unity… for unity is variable and relative. Further, according to Kurt Thumlert (citing Lentricchia, 1998), “a transgressive textuality can also become a mode of agential resistance capable of fragmenting and releasing the subject, and thereby producing a zone of invisibility where knowledge/power is no longer able ‘find its target’.”2

In other words, transgression of the taboo allows the artist (in this case) to release himself from the logic of control and where power cannot get its hooks into him. In order to do this during the production of art, the artist must understand that representations are presentations which entail,

“the use of the codes and conventions of the available cultural forms of presentation. Such forms restrict and shape what can be said by and/or about any aspect of reality in a given place in a given society at a given time, but if that seems like a limitation on saying, it is also what makes saying possible at all. Cultural forms set the wider terms of limitation and possibility for the (re)presentation of particularities and we have to understand how the latter are caught in the former in order to understand why such-and-such gets (re)presented in the way it does. Without understanding the way images function in terms of, say, narrative, genre or spectacle, we don’t really understand why they turn out the way they do.”3

The exhibition Black Light investigates how artists subvert these codes and conventions of representation and violate their taboo through emotions (whether positive or negative) present in the creative process. This transgressive spirit allows far seeing artists to become the seers of their day, playing with the dis/order of time, space and cultural (re)presentation. As a form of alchemy, all art partakes of this investigation into the past, present and future of life, our discontinuous existence as creatures who live and die, and the world that surrounds us, both physically and spiritually.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Bataille, Georges. Death and Sensuality: A Study of Eroticism and the Taboo. New York: Walker and Company, 1962, pp. 64-65.

2/ Thumlert, Kurt. Intervisuality, Visual Culture, and Education. [Online] Cited 10/08/2006 No longer available.

3/ Dyer, Richard. The Matter of Images: Essays on Representations. London: Routledge, 1993, pp. 2-3.

Many thankx to the Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

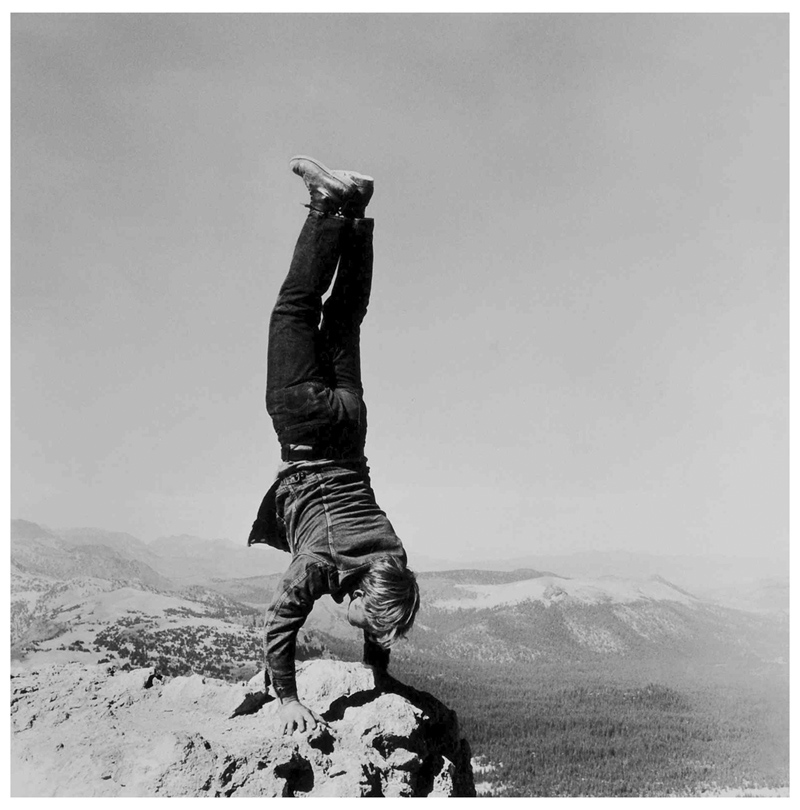

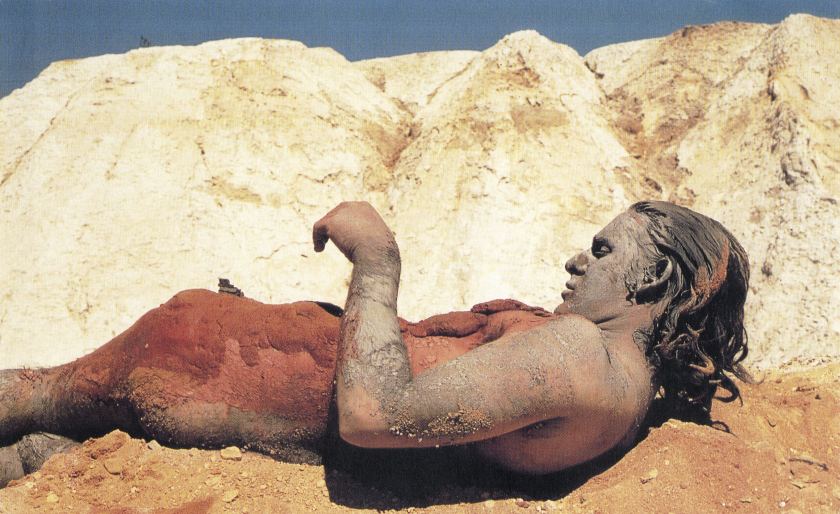

Marcus Bunyan (Australian, b. 1958)

Marcus (after scarification)

1992

Gelatin silver print

© Marcus Bunyan

Black Light. Discover the occult side of contemporary art

The occult, spirituality, psychedelia and esotericism come to the CCCB with the exhibition Black Light. An unusual look at the art of the past 50 years that has been strongly influenced by secret traditions.

Joan Jonas (American, b. 1936)

Reanimation (extract)

Henri Michaux (French born Belgium, 1899-1984)

Henri Michaux (French born Belgium, 1899-1984) was a highly idiosyncratic Belgian-born poet, writer, and painter who wrote in French. He later took French citizenship. Michaux is best known for his esoteric books written in a highly accessible style. His body of work includes poetry, travelogues, and art criticism. Michaux travelled widely, tried his hand at several careers, and experimented with psychedelic drugs, especially LSD and mescaline, which resulted in two of his most intriguing works, Miserable Miracle and The Major Ordeals of the Mind and the Countless Minor Ones.

Kenneth Anger (American, 1927-1996)

Lucifer Rising (Original track by Acqua Lazúli)

1972-80

For more information about this film please see the Lucifer Rising Wikipedia entry

Kenneth Anger (born Kenneth Wilbur Anglemyer; February 3, 1927) is an American underground experimental filmmaker, actor and author. Working exclusively in short films, he has produced almost forty works since 1937, nine of which have been grouped together as the “Magick Lantern Cycle”. His films variously merge surrealism with homoeroticism and the occult, and have been described as containing “elements of erotica, documentary, psychodrama, and spectacle”. Anger himself has been described as “one of America’s first openly gay filmmakers, and certainly the first whose work addressed homosexuality in an undisguised, self-implicating manner”, and his “role in rendering gay culture visible within American cinema, commercial or otherwise, is impossible to overestimate”, with several being released prior to the legalisation of homosexuality in the United States. He has also focused upon occult themes in many of his films, being fascinated by the English gnostic mage and poet Aleister Crowley, and is an adherent of Thelema, the religion Crowley founded.

Text from the Wikipedia website

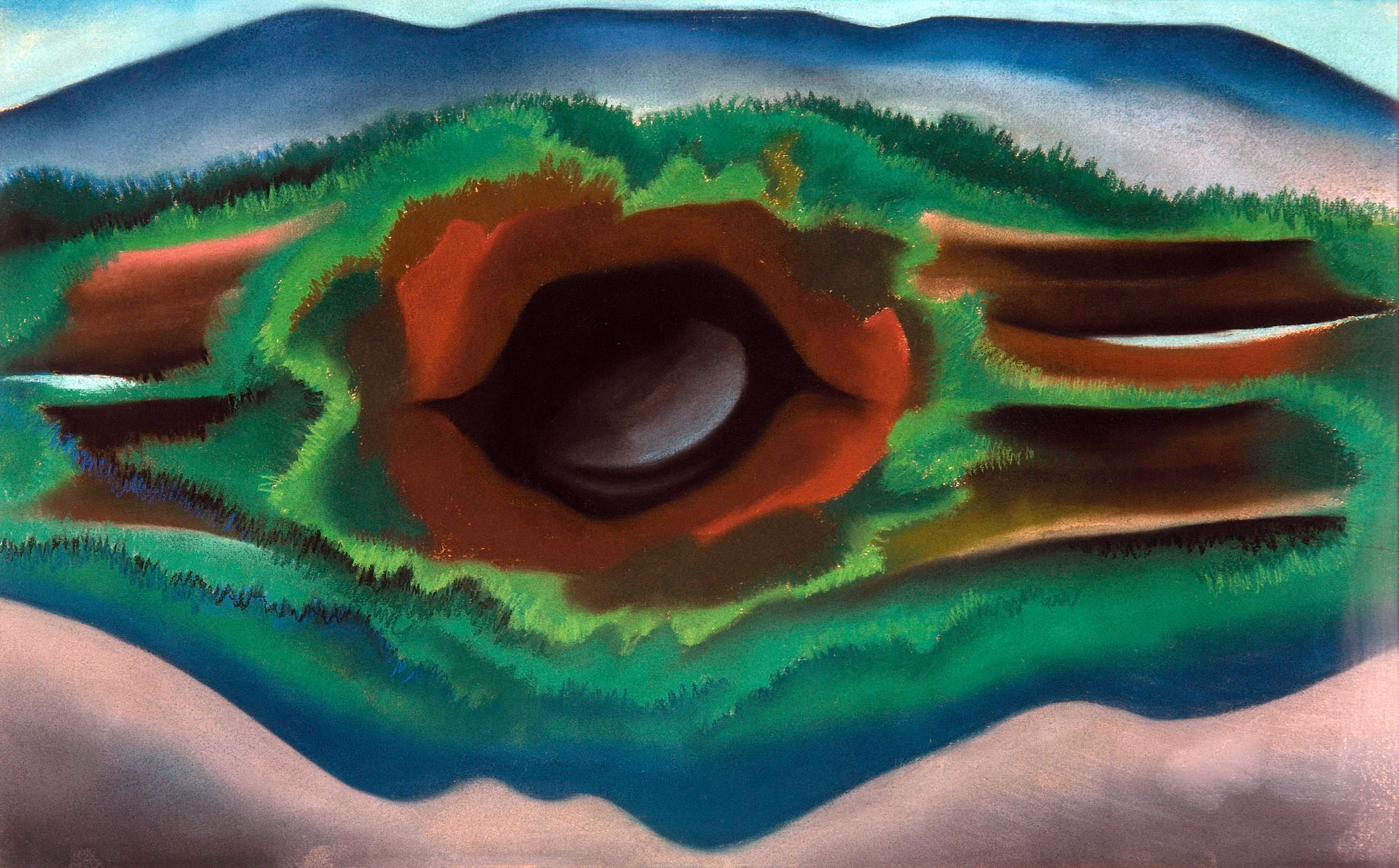

Barnett Newman (American, 1905-1970)

Untitled

1946

Oil on canvas

76.5 x 61.1cm

© IVAM, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Generalitat Valenciana

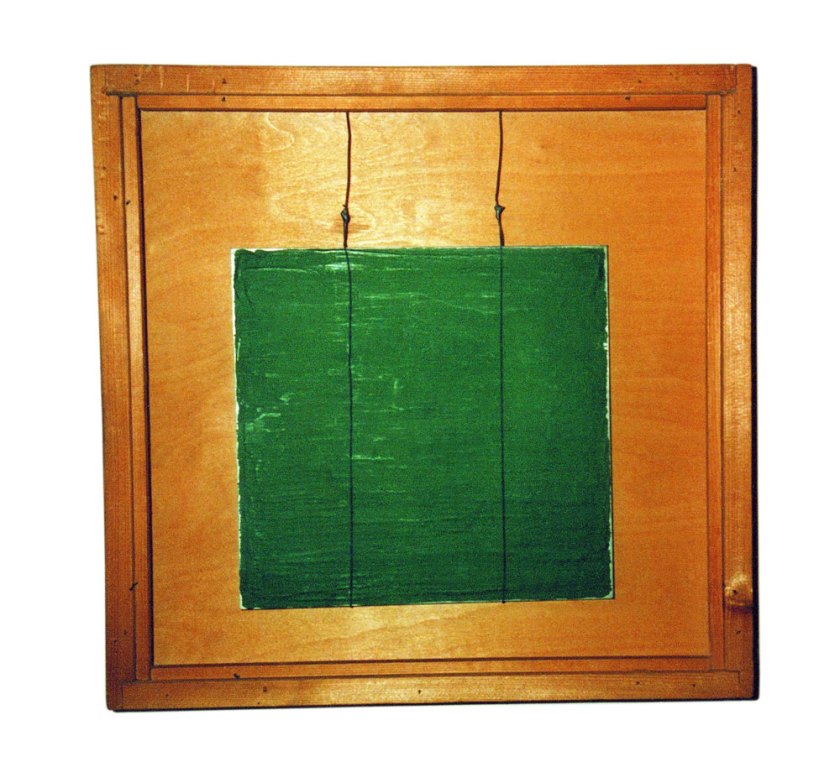

Antoni Tàpies (Spanish, 1923-2012)

Book covers

1987

Paintings on old book covers

60 x 78.5 cm

Private collection, Barcelona

© Heirs of Antoni Tàpies / Vegap, Madrid

Leon Ka (Spanish, b. 1980)

Creatio: Lux, Crux

2015

Door of the cultural association Magia Roja, Barcelona

Black light is about the influence that various secret traditions have had on contemporary art from the nineteen-fifties to the present day. It presents some 350 works by such artists as Antoni Tàpies, Agnes Martin, Henri Michaux, Joseph Beuys, Ulla von Brandenburg, William S. Burroughs, Joan Jonas, Jordan Belson, Goshka Macuga, Kenneth Anger, Rudolf Steiner, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Francesco Clemente and Zush.

Black light brings together, in more or less chronological order, paintings, drawings, audiovisuals, sculptures, photographs, installations, books, music, engravings and documents by artists largely from North America, where secret traditions have historically enjoyed greater acceptance. There are works by creators who are considered fundamental to the history of art, such as Antoni Tàpies, Barnett Newman and Agnes Martin, alongside less-known figures of the counterculture of the sixties and seventies. The show also presents young artists to reflect the renewed interest in these traditions.

The work of all of them goes to show the relevance and continuity of these habitually overlooked trends, in many cases regarding art as a possible means to a higher cognitive level, as an instrument of connection with a more profound reality, or as a form of knowledge in itself. These ideas are contrary, for example, to a purely formalistic understanding of abstraction. Specifically, the exhibition also explores the influence of esoteric ideas on areas of popular culture, such as comics, jazz, cinema and alternative rock.

Henri Michaux (French born Belgium, 1899-1984)

Untitled

1983

Oil on linen paper

24 x 33cm

© Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. Photography: Fabrice Gibert

Marjorie Cameron (American, 1922-1995)

West Angel

Nd

Graphite, ink and gold paint on paper

60.3 x 93.3cm

© Courtesy Nicole Klagsbrun and Cameron Parsons Foundation

Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (American, 1922-1995), who professionally used the mononym Cameron, was an American artist, poet, actress, and occultist. A follower of Thelema, the new religious movement established by the English occultist Aleister Crowley, she was married to rocket pioneer and fellow Thelemite Jack Parsons.

Read her entry on the Wikipedia website

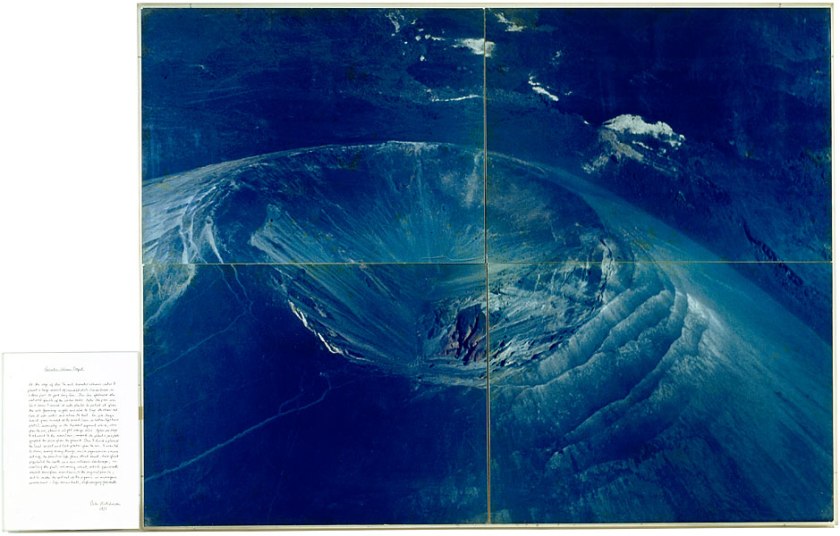

Aleister Crowley (English, 1875-1947)

Snow-Peak beyond Foothills, Libra I8 September-October

1934

Pen and wash on paper

45 x 50cm

© Ordo Templi Orientis

Unknown photographer

Aleister Crowley as Magus, Liber ABA

1912

Originally published in The Equinox volume 1, issue 10 (1913)

Wolfgang Laib (Germany, b. 1950)

Passageway

2013

Brass ships, rice, wood and steel

6 3/4 x 99 x 12 inches

© Wolfgang Laib

Wolfgang Laib (born 25 March 1950 in Metzingen) is a German artist, predominantly known as a sculptor. He lives and works in a small village in southern Germany, maintaining studios in New York and South India.

His work has been exhibited worldwide in many of the most important galleries and museums. He represented Germany in the 1982 Venice Biennale and was included with his works in the Documenta 7 in 1982 and then in the Documenta 8 in 1987. In 2015 he received the Praemium Imperiale for sculpture in Tokyo, Japan.

He became worldknown for his “Milkstones”, a pure geometry of white marble made complete with milk, as well as his vibrant installations of pollen. In 2013 The Museum of Modern Art in New York City presented his largest pollen piece – 7 m x 8 m – in the central atrium of the museum.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Brion Gysin (British, 1916-1986)

Dreamachine

1960-1976

Cylinder. Painted and cut hard paper, Altuglas, electric bulb and motor

120.5 cm x 29.5cm

© Galerie de France. Paris, Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle

Brion Gysin (19 January 1916-13 July 1986) was a painter, writer, sound poet, and performance artist born in Taplow, Buckinghamshire.

He is best known for his discovery of the cut-up technique, used by his friend, the novelist William S. Burroughs. With the engineer Ian Sommerville he invented the Dreamachine, a flicker device designed as an art object to be viewed with the eyes closed. It was in painting and drawing, however, that Gysin devoted his greatest efforts, creating calligraphic works inspired by the cursive Japanese “grass” script and Arabic script. Burroughs later stated that “Brion Gysin was the only man I ever respected.” …

The Dreamachine (or Dream Machine) is a stroboscopic flicker device that produces visual stimuli. Artist Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs’ “systems adviser” Ian Sommerville created the Dreamachine after reading William Grey Walter’ book, The Living Brain.

In its original form, a Dreamachine is made from a cylinder with slits cut in the sides. The cylinder is placed on a record turntable and rotated at 78 or 45 revolutions per minute. A light bulb is suspended in the centre of the cylinder and the rotation speed allows the light to come out from the holes at a constant frequency of between 8 and 13 pulses per second. This frequency range corresponds to alpha waves, electrical oscillations normally present in the human brain while relaxing. In 1996, the Los Angeles Times deemed the Dreamachine “the most interesting object” in Burroughs’ major visual retrospective Ports of Entry at LACMA. The Dreamachine is the subject of the National Film Board of Canada 2008 feature documentary film FLicKeR by Nik Sheehan.

A Dreamachine is “viewed” with the eyes closed: the pulsating light stimulates the optic nerve and thus alters the brain’s electrical oscillations. Users experience increasingly bright, complex patterns of colour behind their closed eyelids (a similar effect may be experienced when travelling as a passenger in a car or bus; close your eyes as the vehicle passes through flickering shadows cast by roadside trees, or under a close-set line of streetlights or tunnel striplights). The patterns become shapes and symbols, swirling around, until the user feels surrounded by colours. It is claimed that by using a Dreamachine one may enter a hypnagogic state. This experience may sometimes be quite intense, but to escape from it, one needs only to open one’s eyes. The Dreamachine may be dangerous for persons with photosensitive epilepsy or other nervous disorders. It is thought that one out of 10,000 adults will experience a seizure while viewing the device; about twice as many children will have a similar ill effect.

Text from the Wikipedia website

An approach without prejudice to art and esoteric beliefs

Esoteric traditions can be traced back to the very origins of civilisation, having served at different times to structure philosophical, linguistic, scientific or spiritual ideas. Despite their importance for the development of twentieth-century art, they tend to be ignored or disparaged these days due to the dominance of rationalistic thinking and the difficulty of talking about these subjects in clear, direct language.

In recent years, however, many artists have taken a renewed interest in subjects such as alchemy, secret societies, theosophy and anthroposophy, the esoteric strands in major religions, oriental philosophies, magic, psychedelia and drug-use, universal symbols and myths, the Fourth Way formulated by the Armenian mystic Georges Gurdjieff, etc., generating an interest in these fields that had not existed since the counterculture of the sixties and seventies.

According to the writer Enrique Juncosa, curator of this exhibition, this interest “may be due to the fact that we are, once again, living in a restless and unsatisfied world, worried about new colonial wars, fundamentalist terrorism, serious ecological crisis and nationalist populism, just as in the sixties and seventies people feared an imminent and devastating nuclear catastrophe. Furthermore, much of today’s mainstream art is actually rather boring due to its complete lack of mystery and negation of any kind of poetisation or interpretation of our experience of it.”

For the essayist Gary Lachman, author of the text “Occultism in Art. A Brief Introduction for the Uninitiated” in the exhibition catalogue, “in recent years, the art world seems to have become aware of the importance of occultism […]. Admitting the influence of Hermeticism on the Renaissance, or of theosophy on early abstract art, to mention just two examples, helps to re-situate occult forces as an undeniable part of human experience and rescue them from the marginal position to which they had been exiled for a few centuries.”

Terry Winters (American, b. 1949)

Bubble Diagram

2005

Oil on linen

215.9 x 279.4cm

© Mattew Marks Gallery

Terry Winters (born 1949, Brooklyn, NY) is an American painter, draughtsman, and printmaker whose nuanced approach to the process of painting has addressed evolving concepts of spatiality and expanded the concerns of abstract art. His attention to the process of painting and investigations into systems and spatial fields explores both non-narrative abstraction and the physicality of modernism. In Winters’ work, abstract processes give way to forms with real word agency that recall mathematical concepts and cybernetics, as well as natural and scientific worlds.

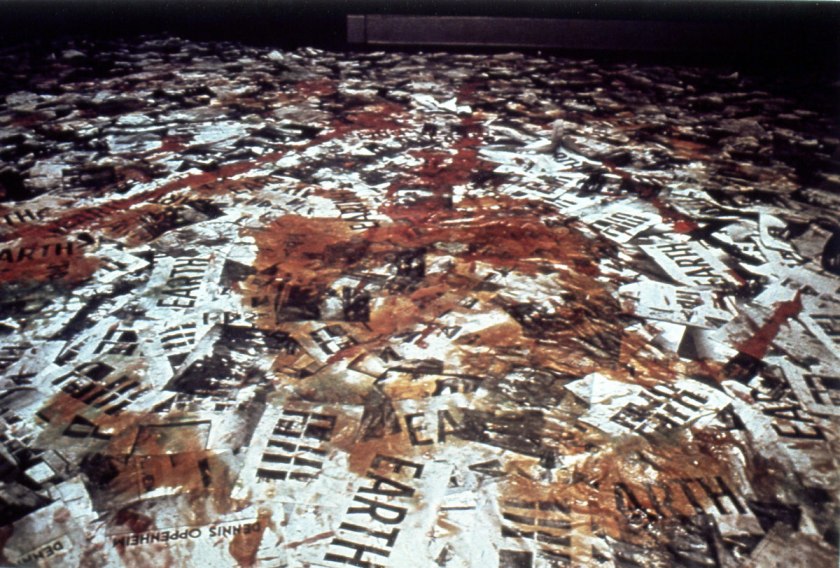

Fred Tomaselli (American, b. 1956)

Untitled (Datura Leaves)

1999

Leaves, pills, acrylic and resin on wood panel

182.88 x 137.16cm

© Collection Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman NY, Courtesy the FLAG Art Foundation

Fred Tomaselli (born in Santa Monica, California, in 1956) is an American artist. He is best known for his highly detailed paintings on wood panels, combining an array of unorthodox materials suspended in a thick layer of clear, epoxy resin.

Tomaselli’s paintings include medicinal herbs, prescription pills and hallucinogenic plants alongside images cut from books and magazines: flowers, birds, butterflies, arms, legs and noses, which are combined into dazzling patterns that spread over the surface of the painting like a beautiful virus or growth. He uses an explosion of colour and combines it with a basis in art history. His style usually involves collage, painting, and/or glazing. He seals the collages in resin after gluing them down and going over them with different varnishes.

“I want people to get lost in the work. I want to seduce people into it and I want people to escape inside the world of the work. In that way the work is pre-Modernist. I throw all of my obsessions and loves into the work, and I try not to be too embarrassed about any of it. I love nature, I love gardening, I love watching birds, and all of that gets into the work. I just try to be true to who I am and make the work I want to see. I don’t have a radical agenda.”

Tomaselli sees his paintings and their compendium of data as windows into a surreal, hallucinatory universe. “It is my ultimate aim”, he says, “to seduce and transport the viewer in to space of these pictures while simultaneously revealing the mechanics of that seduction.” Tomaselli has also incorporated allegorical figures into his work – in Untitled (Expulsion) (2000), for example, he borrows the Adam and Eve figures from Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (1426-27), and in Field Guides (2003) he creates his own version of the grim reaper. His figures are described anatomically so that their organs and veins are exposed in the manner of a scientific drawing. He writes that his “inquiry into utopia/dystopia – framed by artifice but motivated by the desire for the real – has turned out to be the primary subject of my work”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Philip Taaffe (American, b. 1955)

Rose Triangle

2008

Mixed media on canvas

178 x 178cm

© Collection Raymond Foye, New York

About the exhibition

In the fifties, US filmmakers Harry Smith and Jordan Belson made animated films that were precursors of the psychedelia and counterculture of the following two decades. Also at this time, painters associated with abstract expressionism in the US (such as Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt and Agnes Martin) and European Informalists, such as the Catalans associated with Dau al Set (including Antoni Tàpies and Joan Ponç), became interested in the writings of Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung, oriental philosophies, the great myths and primitive shamanic rites. The cult US filmmaker Kenneth Anger made films that are still considered radical, influenced by the ideas of the well-known English occultist Aleister Crowley, who was also influential in the world of rock. And Forrest Bess, a self-taught, isolated artist, an unusual figure in the American art of the last century, painted symbolic, visionary images of the universal collective subconscious.

In the sixties and seventies, the emergence of counterculture and the hippy movement was accompanied by an upsurge in interest in esoteric matters and alternative spirituality. US writer William S. Burroughs and French artist and writer Brion Gysin, both interested in occultism and mysticism, developed the cut-up method to write texts using collage, actions which, like the origin of art itself, they considered magic. The American musician Sun Ra, one of the jazz world’s most idiosyncratic figures (he claims he was born on Saturn), set up the secret society Thmei Research in Chicago, and was interested in the writings of Armenian philosopher and master mystic Georges Gurdjieff, and the Ukrainian Madame Blavatsky, creator of the esoteric current known as theosophy. Sun Ra’s compositions, with a big band that performed in strange colourful clothing, were highly radical, embracing improvisation and chaos. In Europe, the German artist Joseph Beuys was inspired by the writings and activities of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy, as a model to explain his ideas. Beuys called for a return to spirituality and defended art as a vehicle for healing and social change. The French artist Tania Mouraud, interested in introspection and philosophy, with a strong analytical vein, creates installations that are spaces for meditation, and the Catalan artist Zush, in Ibiza, discovers psychedelia and draws fantastic beings connected by vibrant energies.

The eighties and nineties saw the consolidation of a large number of artists who saw artistic practice as something that can facilitate a higher cognitive level. Several American abstract painters, like Terry Winters, Philip Taaffe and Fred Tomaselli, became interested in spiritual themes. Winters, for example, who took scientific images as his inspiration, based a large series of paintings on knot theory, a mathematical concept that might be seen as an emblem of the hermetic. Taaffe, meanwhile, used ornamental forms from different cultures, combining them in complex configurations of an ecstatic nature, and Tomaselli produced compositions using all kinds of drugs in a reference to psychedelia. In Europe, the German sculptor Wolfgang Laib, interested in Zen Buddhism and Taoism, creates sculptures and installations with symbolic images, like stairs and boats, suggesting ascension, travel and inner transformation, while the Italian Gino de Dominicis, who claimed to believe in extra-terrestrials and was obsessed by Sumerian culture and mythology, creates invisible sculptures. The paintings by Italian Francesco Clemente, a representative of the Transavanguardia movement, feature images of an apparently hermetic nature, creating a singular narrative of spiritual symbolism. The Chilean-French artist Alejandro Jodorowsky explores esoteric ideas in his extraordinary films of great visual imagination and also creates highly celebrated comics. In the nineties, several alternative rock bands such as Psychic TV (led by the English musician, poet and artist Genesis P-Orridge) were also interested in occultism and magic.

The origin of the title “Black Light”

The title “Black light” refers to a concept of Sufism, the esoteric branch of Islam that teaches a path of connection with divinity leading via inner vision and mystic experience. Sufism, which regards reality as light in differing degrees of intensity, speaks of a whole system of inner visions of colours that mark the spiritual progress of initiates until they become “men and women of light”. The intention is to achieve a state of supra-consciousness that is announced symbolically by this black light.

Press release from the Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona website

Chris Martin (American, b. 1954)

If You Don’t See It Ask For It

2016

Acrylic and glitter on canvas

195.6 x 152.4 x 4.4cm

© Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Photography: Brian Forrest

Genesis P-Orridge (British, 1950-2020)

Burns Forever Thee Light

1986

Hair, Indian corn, wax, saliva, semen, blood, acrylic paint, flourescent tape, pages from Man Myth & Magic, Polaroids, c-prints, paint pen

20 x 25 inches

© Courtesy of the artist and INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge (born Neil Andrew Megson; 22 February 1950) was an English singer-songwriter, musician, poet, performance artist, and occultist. After rising to notability as the founder of the COUM Transmissions artistic collective and then fronting the industrial band Throbbing Gristle, P-Orridge was a founding member of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth occult group, and fronted the experimental band Psychic TV. P-Orridge identifies as third gender.

Born in Manchester, P-Orridge developed an early interest in art, occultism, and the avant-garde while at Solihull School. After dropping out of studies at the University of Hull, he moved into a counter-cultural commune in London and adopted Genesis P-Orridge as a nom-de-guerre. On returning to Hull, P-Orridge founded COUM Transmissions with Cosey Fanni Tutti, and in 1973 he relocated to London. COUM’s confrontational performance work, dealing with such subjects as sex work, pornography, serial killers, and occultism, represented a concerted attempt to challenge societal norms and attracted the attention of the national press. COUM’s 1976 Prostitution show at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts was particularly vilified by tabloids, gaining them the moniker of the “wreckers of civilization.” P-Orridge’s band, Throbbing Gristle, grew out of COUM, and were active from 1975 to 1981 as pioneers in the industrial music genre. In 1981, P-Orridge co-founded Psychic TV, an experimental band that from 1988 onward came under the increasing influence of acid house.

In 1981, P-Orridge co-founded Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth, an informal occult order influenced by chaos magic and experimental music. P-Orridge was often seen as the group’s leader, but rejected that position, and left the group in 1991. Amid the Satanic ritual abuse hysteria, a 1992 Channel 4 documentary accused P-Orridge of sexually abusing children, resulting in a police investigation. P-Orridge was subsequently cleared and Channel 4 retracted their allegation. P-Orridge left the United Kingdom as a result of the incident and settled in New York City. There, P-Orridge married Jacqueline Mary Breyer, later known as Lady Jaye, in 1995, and together they embarked on the Pandrogeny Project, an attempt to unite as a “pandrogyne”, or single entity, through the use of surgical body modification to physically resemble one another. P-Orridge continued with this project of body modification after Lady Jaye’s 2007 death. Although involved in reunions of both Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV in the 2000s, P-Orridge retired from music to focus on other artistic mediums in 2009. P-Orridge is credited on over 200 releases.

A controversial figure with an anti-establishment stance, P-Orridge has been heavily criticised by the British press and politicians. P-Orridge has been cited as an icon within the avant-garde art scene, accrued a cult following, and been given the moniker of the “Godperson of Industrial Music”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

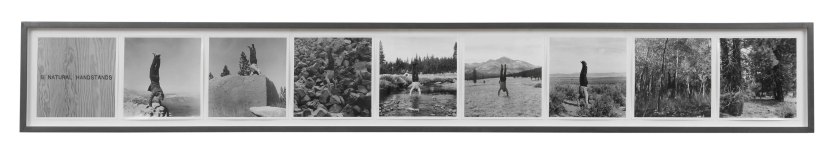

Harry Smith (American, 1923-1991)

Untitled, October 19, 1951

1951

Ink, watercolour, and tempera on paper

86.36 x 69.85cm

Collection Raymond Foye, New York

Agnes Martin (American born Canada, 1912-2004)

Untitled, No. 7

1997

Acrylic and graphite on canvas

152.4 x 152.4cm

Collection “la Caixa”. Art Contemporani

© Vegap

Agnes Bernice Martin (March 22, 1912 – December 16, 2004), born in Canada, was an American abstract painter. Her work has been defined as an “essay in discretion on inward-ness and silence”. Although she is often considered or referred to as a minimalist, Martin considered herself an abstract expressionist. She was awarded a National Medal of Arts from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1998. …

Martin praised Mark Rothko for having “reached zero so that nothing could stand in the way of truth”. Following his example Martin also pared down to the most reductive elements to encourage a perception of perfection and to emphasise transcendent reality. Her signature style was defined by an emphasis upon line, grids, and fields of extremely subtle colour. Particularly in her breakthrough years of the early 1960s, she created 6 × 6 foot square canvases that were covered in dense, minute and softly delineated graphite grids. In the 1966 exhibition Systemic Painting at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Martin’s grids were therefore celebrated as examples of Minimalist art and were hung among works by artists including Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman, and Donald Judd. While minimalist in form, however, these paintings were quite different in spirit from those of her other minimalist counterparts, retaining small flaws and unmistakable traces of the artist’s hand; she shied away from intellectualism, favouring the personal and spiritual. Her paintings, statements, and influential writings often reflected an interest in Eastern philosophy, especially Taoist. Because of her work’s added spiritual dimension, which became more and more dominant after 1967, she preferred to be classified as an abstract expressionist.

Martin worked only in black, white, and brown before moving to New Mexico. The last painting before she abandoned her career, and left New York in 1967, Trumpet, marked a departure in that the single rectangle evolved into an overall grid of rectangles. In this painting the rectangles were drawn in pencil over uneven washes of gray translucent paint. In 1973, she returned to art making, and produced a portfolio of 30 serigraphs, On a Clear Day. During her time in Taos, she introduced light pastel washes to her grids, colours that shimmered in the changing light. Later, Martin reduced the scale of her signature 72 × 72 square paintings to 60 × 60 inches and shifted her work to use bands of ethereal colour. Another departure was a modification, if not a refinement, of the grid structure, which Martin has used since the late 1950s. In Untitled No. 4 (1994), for example, one viewed the gentle striations of pencil line and primary colour washes of diluted acrylic paint blended with gesso. The lines, which encompassed this painting, were not measured by a ruler, but rather intuitively marked by the artist. In the 1990s, symmetry would often give way to varying widths of horizontal bands.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Matías Krahn Uribe (Chile, b. 1972)

Panamor

2016

Canvas and cotton

225 x 225cm

© Matías Krahn Uribe

Matías Krahn (b. Santiago de Chile, 1972) Catalan painter born in Chile who lives and works in Barcelona.

His colourful works are a reflection of the world that surrounds him, of a concrete circumstance and environment, but also of the most intimate and subjective. Interested in the balance between the exterior and the interior, it orders the space and the figures it contains. His work, influenced by surrealism, is the mirror of the psyche and the unconscious that expresses itself in infinite forms and tonalities.

Francesco Clemente (Italian, b. 1952)

Tarot cards: the High Priestess

2009-2011

Water colour, gouache, ink, colour pencil

48.2 x 25.4cm

© Courtesy of the artist

Francesco Clemente (born 23 March 1952) is an Italian contemporary artist. He has lived at various times in Italy, in India, and in New York City. Some of his work is influenced by the traditional art and culture of India. He has worked in various artistic media including drawing, fresco, graphics, mosaic, oils and sculpture. He was among the principal figures in the Italian Transavanguardia movement of the 1980s, which was characterised by a rejection of Formalism and conceptual art and a return to figurative art and Symbolism.

Black Light – Secret traditions in art since the 1950s: occultism, magic, esotericism and mysticism

This exhibition analyses the influence that different secret traditions have had on art since the 1950s and today. These are traditions that can be traced back to the very origins of civilisation and that have served at various times to structure philosophical, linguistic, scientific and spiritual ideas.

Despite the importance that these ideas had for the development of 20th century art – being fundamental in the work of key figures of modernity such as Piet Mondrian, Vasili Kandinski, Arnold Schönberg, William Butler Yeats and Fernando Pessoa – it is a tradition that has often been ignored in our time because of the dominant influence of rationalist orthodox thoughts, which are often ignored in our times.

Today, however, many contemporary artists re-explore these themes and are interested in issues as diverse as alchemy, secret societies, theosophy and anthroposophy; the esoteric currents of the great religions; oriental philosophies and magic; psychedelia and the ingestion of drugs; universal symbols and myths; the so-called fourth way of the Armenian mystic Georges Gurdjieff, etc., and, in so doing, generate a renewed interest in these issues that did not exist since the years of counterculture in the 1970s. Authors such as Mircea Eliade, historian of religions and novelist; Carl Gustav Jung, psychologist; Henry Corbin, specialist in Sufism, the esoteric current of Islam; Gershom Scholem, specialist in Kabbalah, the esoteric current of Judaism; and Rudolf Steiner, the founding philosopher of anthroposophy, have now found numerous new readers.

The exhibition will present, more or less chronologically, paintings, drawings, films, sculptures, photographs, installations, books, music and documents by artists as varied as Harry Smith, Jordan Belson, Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, Ad Reinhardt, Antoni Tàpies, Joan Ponç, Henri Michaux, René Daumal, Forrest Bess, Kenneth Anger, Alejandro Jodor. The work of all of them demonstrates the relevance and continuity of these usually ignored traditions, and in many cases understands art as a possible way to reach a higher cognitive level or as a form of knowledge in itself.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a catalogue with texts by specialists such as Cristina Ricupero, Gary Lachman, Erik Davies and Enrique Juncosa. The proposal will also investigate and reveal occult traditions and their current context in the cultural production of our country.

Text from the Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona website

Irrationality from rationality

Vincenç Villatoro, director of the CCCB, has justified the presence of this exhibition in a centre that defends rational culture, alluding to the fact that much of the artistic production can not be understood without its connection to non-rationalistic traditions: mystical, esoteric, hermetic … and points out that although in the second half of the twentieth century the hegemonic thought was the scientist, there was a sensitive part of society that came to other traditions, especially to give meaning to its life. Villatoro warns the visitor that the exhibition La llum negra is not an encyclopedia on hidden traditions, but neither is it intended to be a defence, nor a refutation. But the exhibition points out that for many creators, art is a way to access a deeper reality, which is difficult to access in other ways. Thus, secret tradition and art are complemented.

Gustau Nerín

Forrest Bess (American, 1911-1977)

Homage to Ryder

1951

Oil on canvas

20.8 × 30.5cm

© Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago Gift of Mary and Earle Ludgin Collection

Forrest Bess (October 5, 1911-November 10, 1977) was an American painter and eccentric visionary. He was discovered and promoted by the art dealer Betty Parsons. Throughout his career, Bess admired the work of Albert Pinkham Ryder and Arthur Dove, but the best of his paintings stand alone as truly original works of art. …

He worked as a commercial fisherman, but painted in his spare time. He experienced visions or dreams, which he set down in his paintings. It was during this time he began to exhibit his works, earning one-person shows at museums in San Antonio and Houston. During his most creative period, 1949 through 1967, Betty Parsons arranged six solo exhibitions at her New York City gallery.

Bess was never comfortable for very long around other people, although he hosted frequent visitors to his home and studio at Chinquapin: artists, reporters, and some patrons made the trip to the spit of land on which Bess’s shack stood. He did forge lasting relationships with a few friends and neighbours, and maintained years-long friendships and correspondence with Meyer Schapiro and with Betty Parsons. But ultimately Bess preferred solitude, and his prolific activities as an artist, highlighted by limited notoriety and success, alternated with longs spells of loneliness, depression, and an ever-increasing obsession with his own anatomical manifesto.

In the 1950s, he also began a lifelong correspondence with art professor and author Meyer Schapiro and sexologist John Money. In these and other letters (which were donated to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art), Bess makes it clear that his paintings were only part of a grander theory, based on alchemy, the philosophy of Carl Jung, and the rituals of Australian aborigines, which proposed that becoming a hermaphrodite was the key to immortality. He was never able to win any converts to his theories or validation from the many doctors and psychologists with whom he corresponded. In his own home town of Bay City, he was considered something of a small-town eccentric.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Rudolf Steiner (Austrian, 1861-1925)

Untitled (Blackboard drawing from a lecture held by Rudolf Steiner on 20. 03. 1920)

1920

Chalk on paper

87 x 124cm

Rudolf Steiner Archiv, Dornach

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 (or 25) February 1861-30 March 1925) was an Austrian philosopher, social reformer, architect and esotericist. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century as a literary critic and published philosophical works including The Philosophy of Freedom. At the beginning of the twentieth century he founded an esoteric spiritual movement, anthroposophy, with roots in German idealist philosophy and theosophy; other influences include Goethean science and Rosicrucianism.

In the first, more philosophically oriented phase of this movement, Steiner attempted to find a synthesis between science and spirituality. His philosophical work of these years, which he termed “spiritual science”, sought to apply the clarity of thinking characteristic of Western philosophy to spiritual questions, differentiating this approach from what he considered to be vaguer approaches to mysticism. In a second phase, beginning around 1907, he began working collaboratively in a variety of artistic media, including drama, the movement arts (developing a new artistic form, eurythmy) and architecture, culminating in the building of the Goetheanum, a cultural centre to house all the arts. In the third phase of his work, beginning after World War I, Steiner worked to establish various practical endeavours, including Waldorf education, biodynamic agriculture, and anthroposophical medicine.

Steiner advocated a form of ethical individualism, to which he later brought a more explicitly spiritual approach. He based his epistemology on Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s world view, in which “Thinking… is no more and no less an organ of perception than the eye or ear. Just as the eye perceives colours and the ear sounds, so thinking perceives ideas.” A consistent thread that runs from his earliest philosophical phase through his later spiritual orientation is the goal of demonstrating that there are no essential limits to human knowledge.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The blackboard drawings are the instructions of a new design language that the artist wants to develop. Steiner believes in the development of a supersensible consciousness, a big change for the future of humanity. He gives many lectures in which he details his research on the concept of transmission and its influence on the social. Whether true or not, artists such as Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky and others are interested in the complex graphics of Steiner and his research. Mondrian will even write: “Art is a way of development of mankind.”

Anonymous text from the Culture Box website translated from French [Online] Cited 17/10/2018. No longer available online

Adaptive images from the exhibition Black Light: Secret traditions in art since the 1950s at the Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona

Centre de Cultura Contemporania de Barcelona

Montalegre, 5 – 08001 Barcelona

Phone: 93 306 41 00

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 11.00 – 20.00

![Fred Tomaselli (American, b. 1956) 'Untitled [Datura Leaves]' 1999 Fred Tomaselli (American, b. 1956) 'Untitled [Datura Leaves]' 1999](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/tomaselli-untitled-datura-leaves-1999-web.jpg?w=650&h=813)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'El juego de las probabilidades' [The Game of Probabilities] 2007](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/el-juego-de-las-probabilidades-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994 Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/ambulatorio-web.jpg?w=840&h=555)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986 Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/cortinas-de-bac3b1o-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narcisos (en proceso)' [Narcissi (in process)] 1995-2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/narcisos-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001 Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/narciso-web.jpg?w=840&h=878)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004 Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/re_trato-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995 Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/aliento-web.jpg?w=840&h=687)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002 Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/la-mirada-del-cc3adclope-web.jpg?w=840&h=525)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011 Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/horizonte-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Fundido a blanco (dos retratos)' [Fade to White (Two Portraits)] 2010](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/fade-to-white-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Sedimentaciones' [Sedimentations] 2011](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/sedimentaciones-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-b-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-c-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.