Exhibition dates: 4th April 2020 – 11th April 2021

Curators: Iris Müller-Westermann and Milena Høgsberg

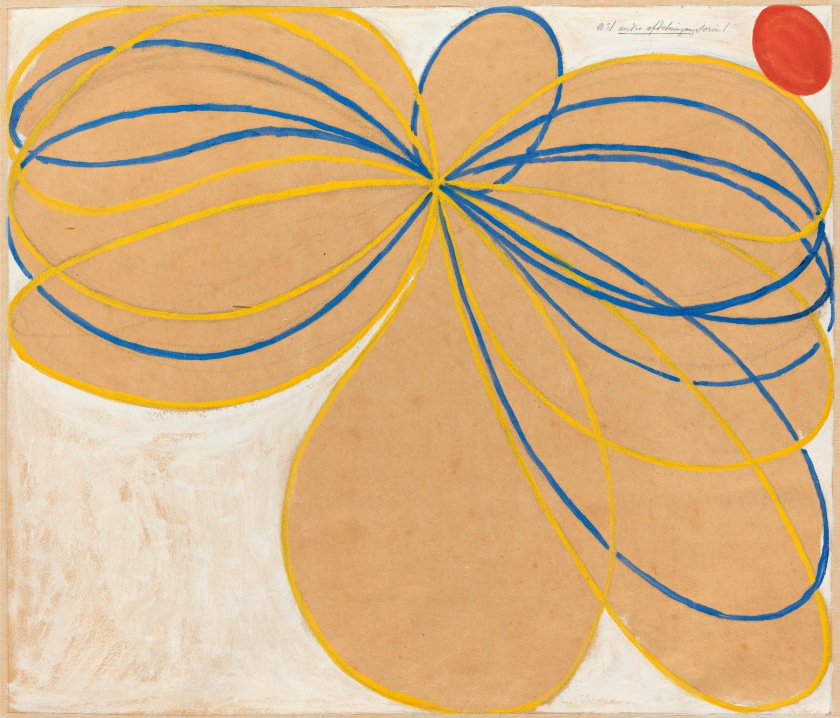

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

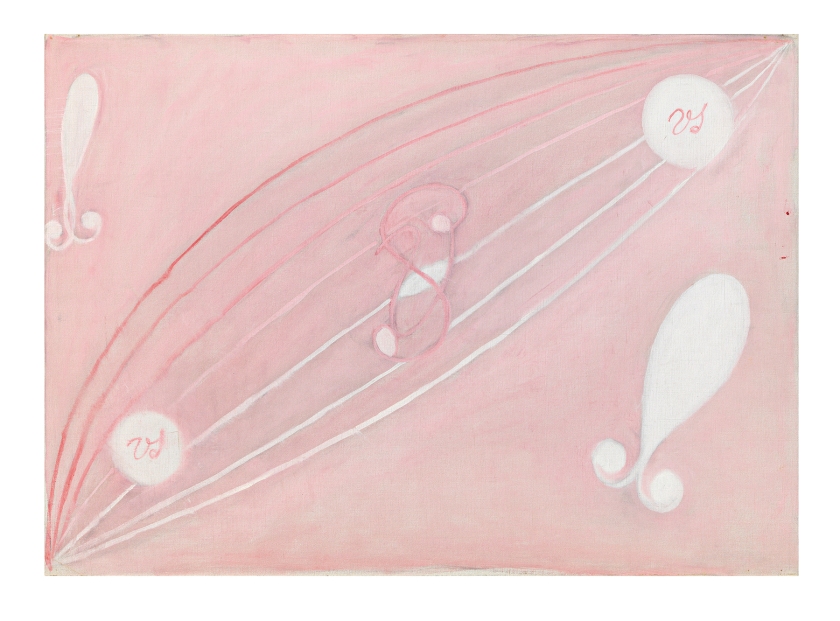

Serie WU/Rosen, Grupp II, The Eros Series, No. 2

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

The third secret

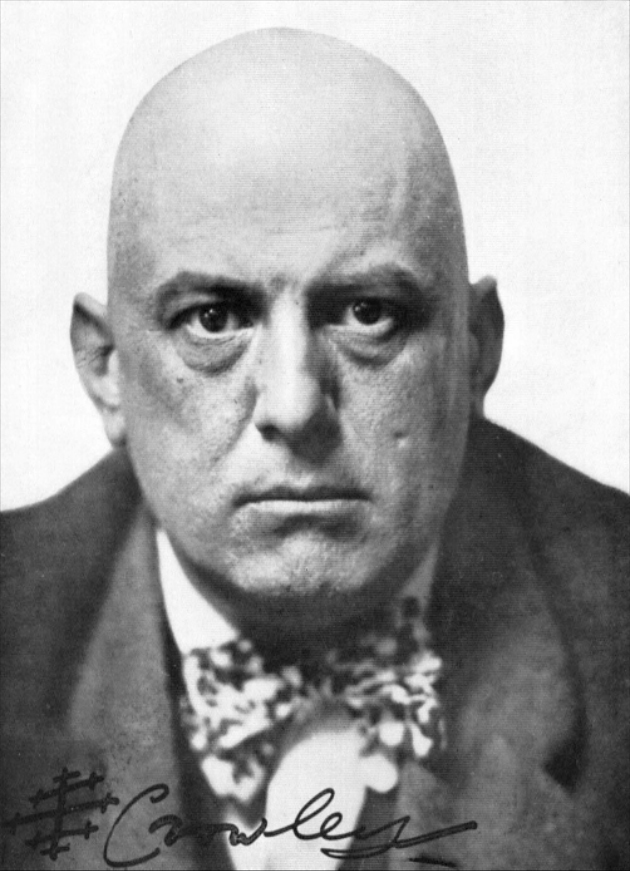

Af Klint is one my favourite painters. At such an early date (preceding any man), she created new forms from her imagination, abstract forms, that connect to, and exist, on a celestial plane.

af Klint studied Theosophy and Rosicrucianism, expanding her consciousness, trusting that “knowledge of a deeper spiritual reality could be achieved through focused attention on intuition, meditation, and other means of transcending normal human consciousness.” All from 1906-1907 onwards.

Her paintings and drawings emit an aura, her aura “drawn” into a cosmic aura, as a revelation of spirit – invisible dimensions that exist beyond the visible world – a connection from our reality to the spirit of the cosmos. Childhood; youth; adulthood; primordial chaos; eros; evolution; the altar and the tree of knowledge. All knowledge that allows us access to the divine, that opens us not to phenomena, but to the noumenal experiences of the felt, spiritual sublime.

Imagine af Klint painting her huge canvases on the floor of her studio, so many years before Jackson Pollock attempted the same connection to altered consciousness, and creating these symbolic and sensation/al masterpieces. Then to have the prescience to understand that the world was not ready for her art, would not understand it, had no way of comprehending the enormity of her artistic enquiry. To leave “a radical body of work – unprecedented in its use of colour, scale and composition – which she hoped future audiences might be better able to sense and decode.” All in hope!

Leaving everything to her nephew, she instructed him not to even open the boxes of her abstract art (which she never exhibited during her lifetime) until 20 years after her death in the late 1960s. In the ultimate irony, in 1970 her entire collection was offered to the Moderna Museet as a gift – the very museum in which this exhibition is being staged – AND THEY REFUSED THE GIFT.

What were the big wigs and curators (probably all men) at the Moderna Museet thinking in 1970? Didn’t they use their eyes, didn’t they sense the bravery of af Klint’s artistic enquiry, or feel the ecstatic (involving an experience of mystic self-transcendence) ecstasy of her work – that rapture of an emotional divine!

I am SO happy her work is now being acclaimed. For the force was truly with her.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Moderna Museet Malmö for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The exhibition opens with the joyful series dedicated to Eros, the Greek god of love, associated with fertility and desire. Full of life, these pink-hued works take up the theme of polarity between male and female as the driving force of evolution. These abstract works completely differ from the classic representation of Eros.

In the series “The Seven-Pointed Star” (1908), Hilma af Klint experimented with a greater economy of line, depicting spiralling energy expanding outwards and forming new centres. As is the case with most of af Klint’s work, there is no singular meaning. Seven is a sacred number in many cultures, associated with divine order, and also the eternal harmony of the universe. In Theosophy the star cluster, known as the Seven Stars or the Pleiades, transmits spiritual energy that eventually reaches the human plane.

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie WU/Rosen, Grupp II, The Eros Series, No. 8

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

During the spring and summer of 2020, Moderna Museet Malmö will give its visitors an opportunity to become acquainted with the fascinating and ground-breaking Swedish artist Hilma af Klint in a comprehensive presentation. The exhibition will present, among other works, the series “The Ten Largest,” which will be shown in it’s entirety.

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) was a pioneer of abstraction. As early as 1906 she had developed a rich, symbolic imagery that preceded the more broadly recognised emergence of abstract art. Since her retrospective at Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2013, interest in the Swedish artist has increased all over the world. The exhibition “Hilma af Klint – Artist, Researcher, Medium” further expands our understanding of this groundbreaking artist and researcher.

Hilma af Klint studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm from 1882 to 1887 where she focused on naturalistic landscape and portrait paintings. Like many of her contemporaries, af Klint also had a keen interest in invisible dimensions that exist beyond the visible world. When painting she was convinced that she was in contact with higher consciousness, which conveyed messages through her. Her major series, “The Paintings for the Temple”, became the crux of this artistic inquiry.

The exhibition centres on three aspects of Hilma af Klint’s life and interests – as artist, researcher and medium – that are key to revealing and understanding her art. With few exceptions, af Klint never exhibited her abstract works during her lifetime. Yet she left us with a radical body of work – unprecedented in its use of colour, scale and composition – which she hoped future audiences might be better able to sense and decode.

Hilma af Klint made paintings for the future, and that future is now.

Artist and Medium

Like many of her contemporaries at the turn of the twentieth century, Hilma af Klint sought to expand her consciousness in order to gain a wider perspective on what we perceive as reality. Consciousness remains one of the deepest mysteries in our time, a subject eagerly explored in neurology, psychology, quantum physics and epigenetics. As part of her spiritual practice, af Klint meditated, adhered to a vegetarian diet, and studied Theosophy and Rosicrucianism. These two esoteric schools thought knowledge of a deeper spiritual reality could be achieved through focused attention on intuition, meditation, and other means of transcending normal human consciousness. Over a period of ten years, af Klint met weekly with four other women, known as De fem (“The Five”). They trained their capability to access or “channel” higher levels of consciousness through contact with spiritual guides known as De Höga (“The Masters”). Af Klint received a specific assignment, which she accepted, known as “The Paintings for the Temple”. She worked throughout her life to understand the deeper meaning embedded in these works.

“The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brushstroke.”

The artist described how she painted the series as a medium, where shapes, colours and compositions came to her. Although af Klint perceived these works as flowing uninhibitedly through her guided hand, she very much applied herself and all her skills in the process: she worked methodically and sequentially in series, divided into thematically and formally focused groups exploring different aspects of cosmic and human evolution.

The Paintings for the Temple

Between 1906 and 1915, Hilma af Klint created “The Paintings for the Temple”. It comprises 193 paintings and drawings, divided into series and groups. Works produced between 1906 and 1908 are on view in the Turbine Hall; works from the second part of the series from 1912 to 1915 are on view in the upstairs galleries at Moderna Museet Malmö.

The overall theme of the series is to convey different aspects of human evolution, instigated by polarity. “The Paintings for the Temple” also thematises different stages of development that every human being goes through during life on earth. The temple in the title refers not only to a physical building, which af Klint imagined would house the work, but also to the body as a temple for the soul.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

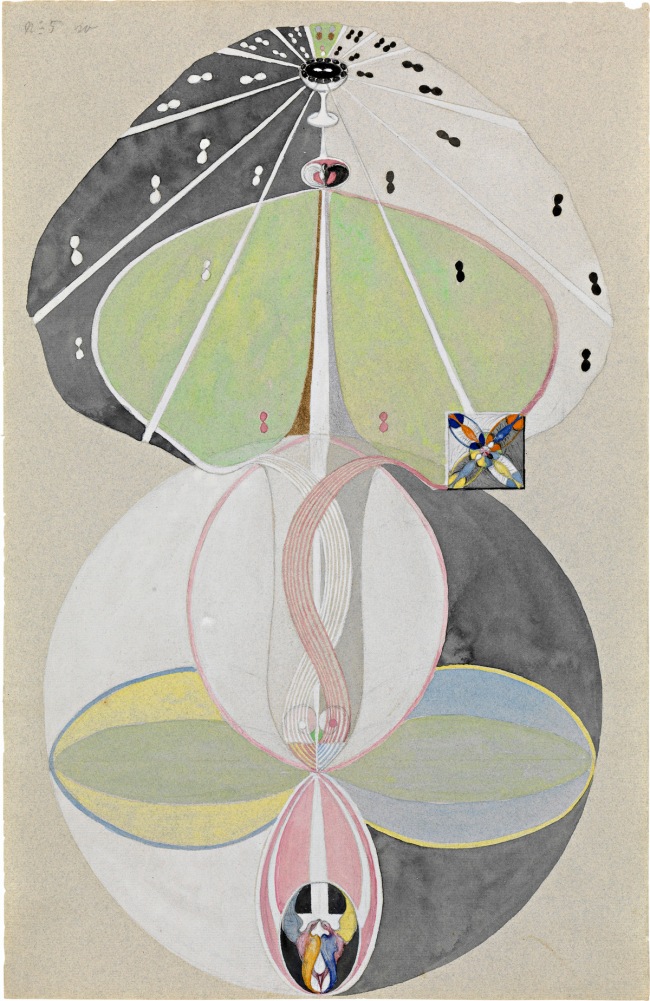

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 1, Childhood

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 2, Childhood

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Like many of the other series within “The Paintings for the Temple”, “The Ten Largest” seems somehow unfettered by limitations of place and time. Across ten canvases, swirling shapes in soft pastel colours rhythmically interact with cursive letters, forming a kind of visual poem. Petals, ovaries, flowers and spirals pulsate in constant sparks of creation. Hilma af Klint attributed this series to the exploration of the human life cycle, from childhood and youth to adulthood and old age. The artist created the ten works between November and December of 1907 on large sheets of paper later glued onto canvas. Given the unusual scale of the works, it is likely that af Klint painted each canvas, while it was lying flat on her studio floor.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 3, Youth

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 4, Youth

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 5, Adulthood

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 6

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 7, Adulthood

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Ten Largest, No. 8, Adulthood

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

On June 16, Moderna Museet Malmö opened again after having been closed for a time in response to the Coronavirus pandemic. Finally, Hilma af Klint – Artist, Researcher, Medium, a comprehensive presentation of the artist with 230 works occupying the entire museum building, can be experienced by the public.

Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) was an artist who allowed herself to take a broader perspective on life and who wanted to open up new ways of looking at reality. Her achievement as a pioneer of abstract art has been celebrated before, but with the exhibition Hilma af Klint – Artist, Researcher, Medium, Moderna Museet Malmö now wants to offer new insights into the artist’s systematic research.

“Hilma af Klint radically turned away from the portrayal of a visible reality,” says Iris Müller-Westermann. “For her, art making was about visualising contexts that lie beyond what the eye can see. Af Klint was convinced that she was connected to a higher level of consciousness when she was making her works. The exhibition argues that her spiritual practice was inextricably linked to her artistic practice. First and foremost, however, Hilma af Klint believed in the power of images.”

The whole Moderna Museet Malmö has been transformed into Hilma af Klint’s temple. The exhibition spans the artist’s entire career, and the selection of works examines the artist’s research into nature and the links between the visible and invisible worlds. In addition, the comprehensive exhibition touches on the artist’s own thoughts about her work and its various methods.

“Hilma af Klint had an inquisitive mind,” says Milena Høgsberg. “For her, painting was both an artistic activity and a spiritual one. When she was painting she meditatively allowed something bigger to pass through her and manifest itself in works of art. She then spent her life, systematically and analytically trying to understand the meaning behind her paintings, drawings, and writings.”

The heart of the exhibition are The Paintings for the Temple (1906-1915), which the artist considered her most important works. They also include the magnificent series The Ten Largest from 1907.

In conjunction with the exhibition, a comprehensive and richly illustrated catalogue has been produced, with essays by Iris Müller-Westermann, Milena Høgsberg in conversation with Tim Rudbøg, Hedvig Martin, Ernst Peter Fischer, and Anne Sophie Jørgensen. The exhibition catalogue has been published in two editions – one in Swedish and one in English.

Hilma af Klint – Artist, Researcher, Medium will be on view at Moderna Museet Malmö until September 27, 2020.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Installation views, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020

Photos: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

De tio största, nr 9, Ålderdomen, grupp IV

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

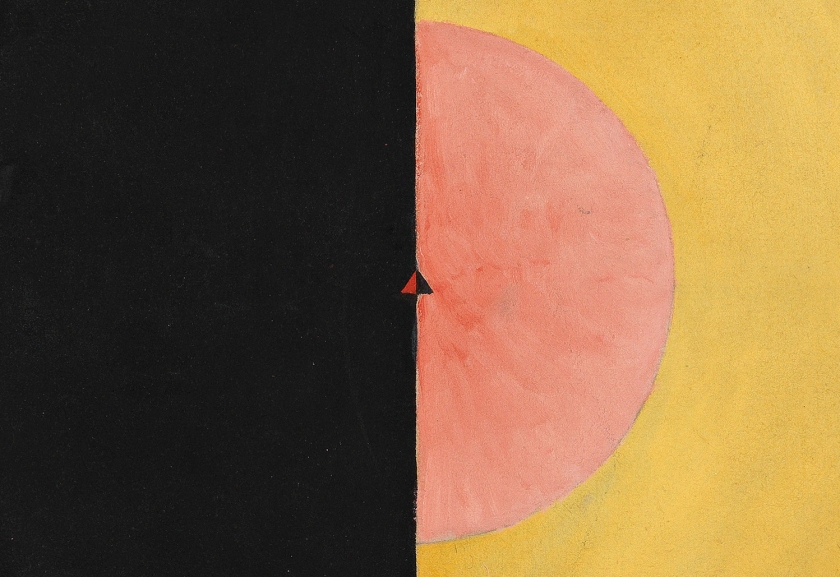

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/UW, nr 25, The Dove, No. 1

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

“The Dove” (1915) depicts the creation process. It draws upon Christian symbols such as the dove for spirit, peace and unity. It also thematises the battle between the forces of light and darkness through the allegory of Saint George and the Dragon.

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Dove, no. 9

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Installation view, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing at left The Dove, No. 1, and at right The Dove, No. 9

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Large Figure Paintings, No. 5

1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

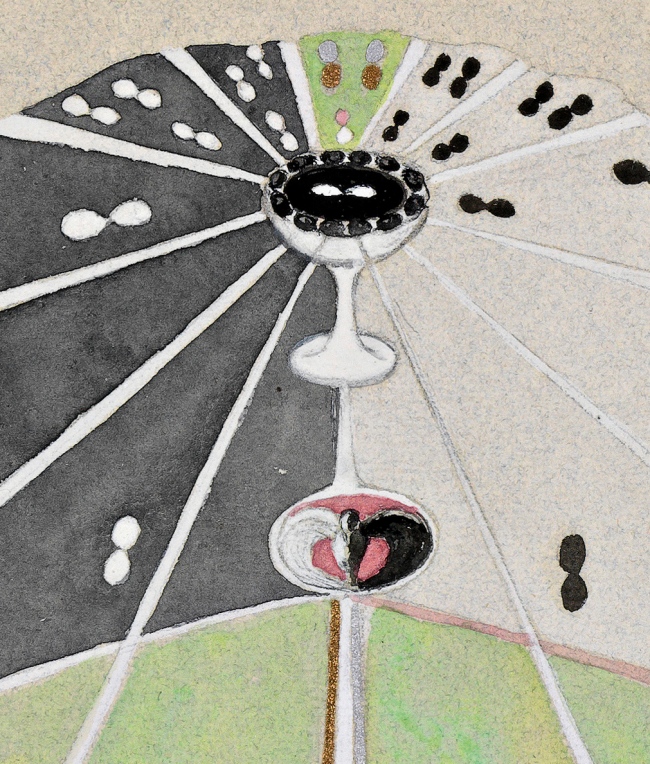

Group I, Primordial Chaos, No. 10

1906

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Primordial Chaos, No. 15

1906-1907

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

“Primordial Chaos” (1906-1907) is devoted to the creation of the physical world. From the original unity a polarised world arose out of spirit, shown here as feminine (blue and the eyelet) and masculine (yellow and the hook), and also as W (material) and U (spirit). These works are full of spirals of energy and sparks of creation, of symbols of fertility and rebirth (sperm, snakes, crosses).

Installation view, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing at left works from the series Evolution, and at centre works from the series Primordial Chaos

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Group VI, The Evolution, No. 7

1908

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

The theme of the evolution of consciousness runs throughout “The Paintings for the Temple”. In the series “Evolution” (1908), the process of development is shown through the interplay between polarities: male and female, light and darkness, good and evil. Compositionally these works strive to find a balance, in horizontal and vertical mirroring. Hilma af Klint’s exploration seems aligned with the theosophist notion of evolution as a spiritual process, extending beyond the biological perspective on human development that, with the publishing of Darwin’s “The Evolution of the Species” fifty years earlier, had gained widespread notoriety. This series ends the first part of “The Paintings for the Temple”, as the commission was paused between 1908 and 1912.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Group VI, The Evolution, No. 9

1908

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Evolution, No. 10

1908

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Installation view, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing work from the series The Swan

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, nr 1., The Swan, No. 1

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

When Hilma af Klint resumed her work on “The Paintings for the Temple” in 1912, her abstraction became more geometric in nature, and Christian symbols became increasingly pronounced. When working, the artist was still in contact with higher planes of consciousness but was encouraged to interpret spiritual messages more freely.

Viewed in sequence, “The Swan” (1914-1915) has a distinct visual rhythm. Often a horizontal line breaks the canvases into two sections where opposite forces meet – light and dark, male and female, life and death. These poles unfold as a black and white swan. Eventually, figuration gives way to abstraction in a fuller spectrum of colour. In the final work in the series, the swan pair returns, unified at the centre, intertwined yet distinct and balanced as male and female poles.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 8

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 9

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 16

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 17

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 21

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Serie SUW/UW, Grupp IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 23

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Installation view, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing work from the series The Swan

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

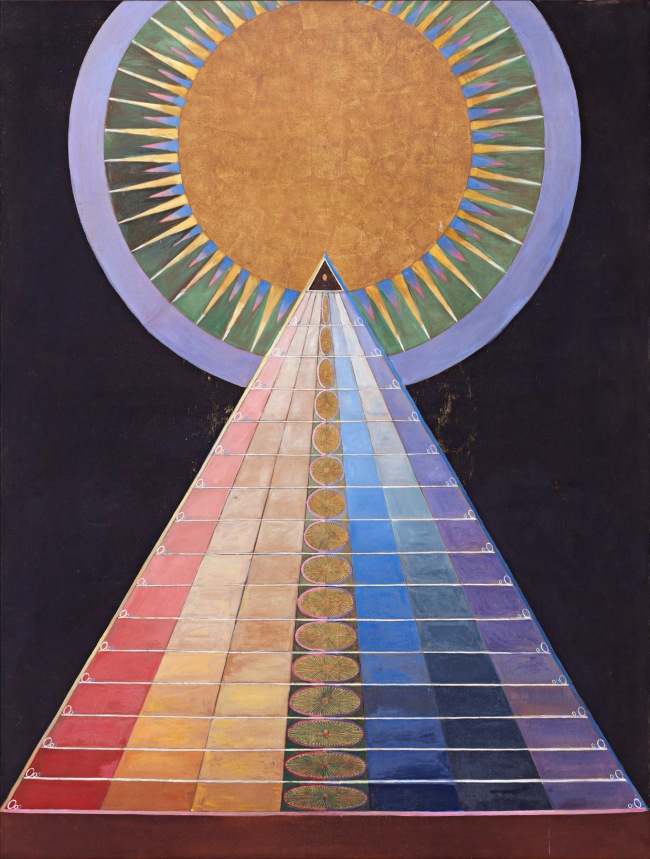

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Altarpiece Grupp X, No. 1

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Altarpiece Group X, No. 2

1915

Oil and metal leaf on canvas

93.75 x 70.5 inches

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint understood the three powerful “Altarpieces” (1915) as the essence of “The Paintings for the Temple”. These works capture the two directions of spiritual evolution: the ascension from the material world back to unity (the triangle pointing to the golden circle) and the descension from divine unity into the diversity of the material world (the inverted triangle). In the third and final painting, a small six-pointed star within the large golden circle is an esoteric symbol for the universe.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Installation views, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing work from the series Altarpieces

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Altarpiece Grupp X, No. 3

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Parsifal Grupp I, No. 1

1916

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

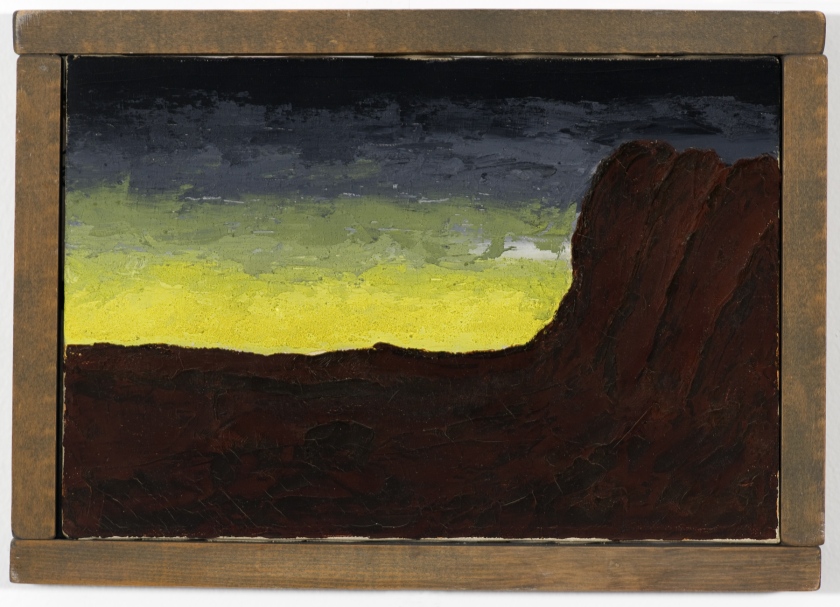

The title of this series from 1916 may refer to the legend of King Arthur, in which Parsifal, one of the Knights of the Round Table, takes part in the quest for the Holy Grail. On 144 sheets, of which a selection is on view, Hilma af Klint depicts the search for knowledge as a journey through various levels of consciousness. In the first image this is marked by a winding path through the darkness towards the white light at the centre of the spiral. In other works, a young boy, shown in different ages, attempts to balance between matter and spirit, up and down. This exploration is continued in radically conceptual yellow monochromes, inscribed with words marking direction: “Nedåt” (downward), “Framåt” (forward), “Bakåt” (backward), “Utåt” (outward) and “Inåt” (inward). Parsifal’s journey also mirrors the artist’s own process in the inward journey she has undertaken by accepting, completing and trying to understand “The Paintings for the Temple”.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Parsifal Grupp II, No. 69

1916

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Parsifal Grupp III, No. 110

1916

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Parsifal Grupp III, No. 117

1916

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

No title, No. 22

1917

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

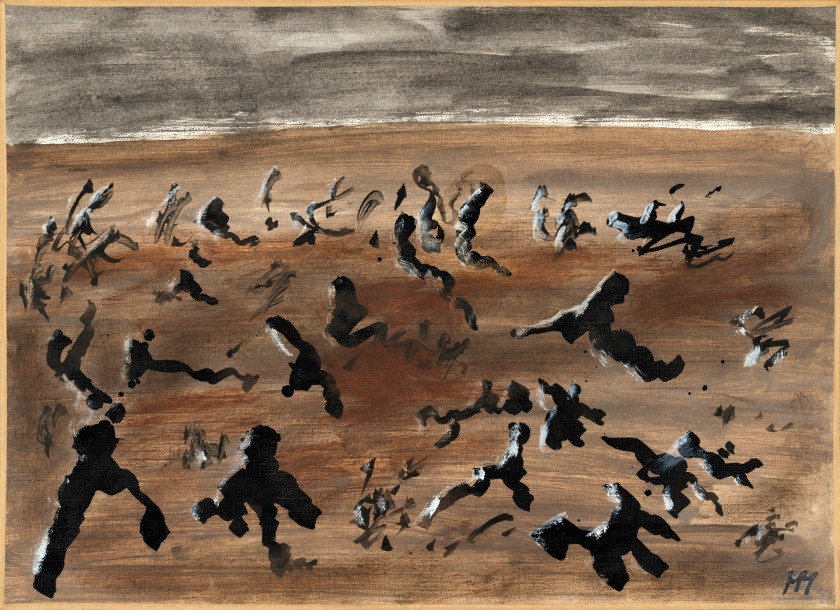

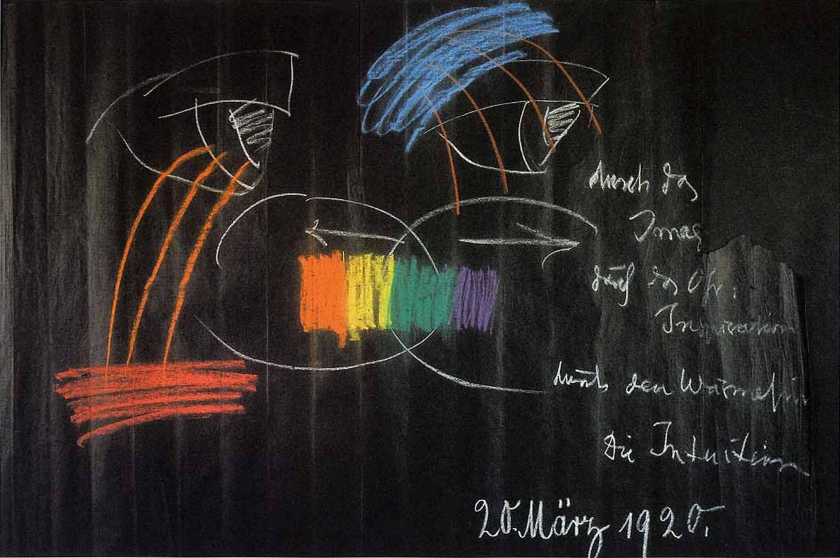

De Fem – Drawings

Between 1896 and 1906, Hilma af Klint and four other women formed the group “De Fem” (“The Five”). They met weekly to meditate, read spiritual literature and accesses higher consciousness through communication with spirit guides, “De Höga” (“The Masters”). These meetings were meticulously recorded in writing and led even to automatic drawings. The women took turns to wield the pen during their sessions, but individual authorship was not important, and rarely indicated on the drawings. The pastel works on view exhibit elements that recur in af Klint’s later work – for example, spiral, stylised floral motifs and other geometrical forms.

Installation views, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020 showing at bottom left, the Tree of Knowledge series 1915; and at centre right, work from Late Series

Photo: Helene Toresdotter/Moderna Museet

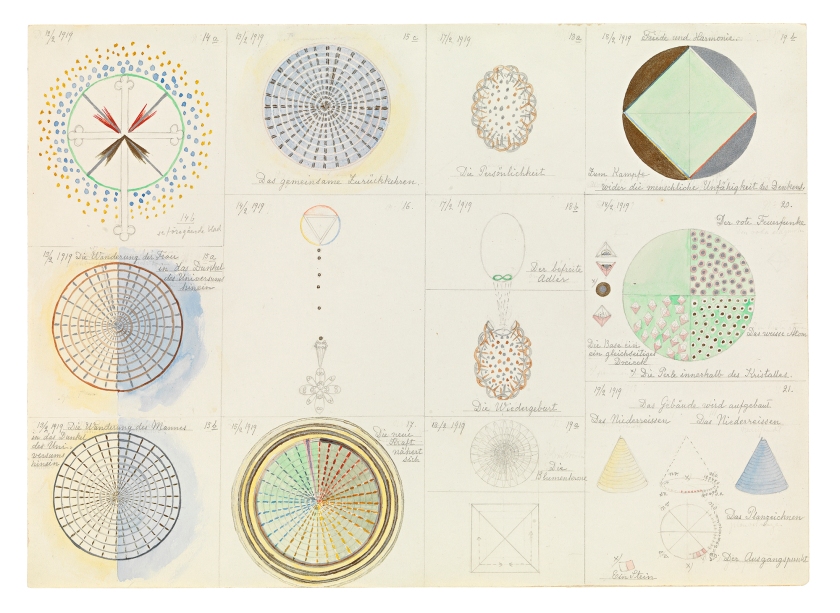

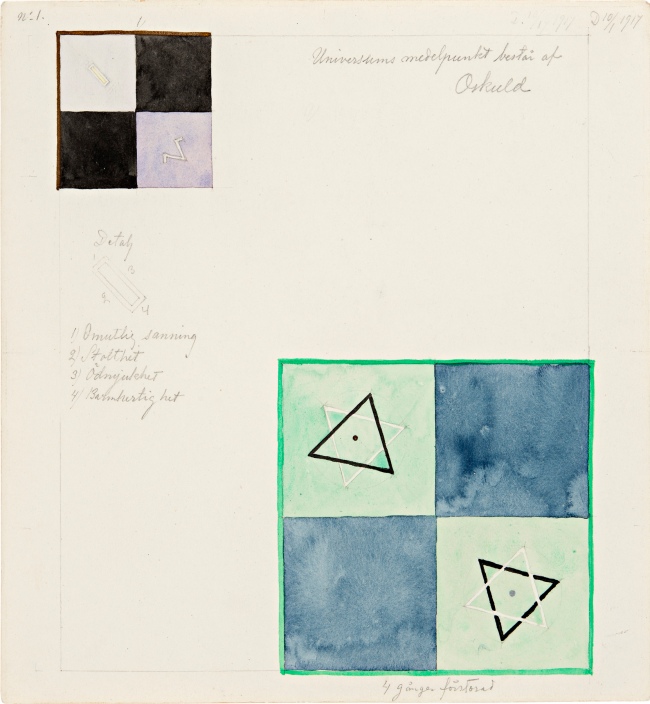

New Gallery is dedicated to Hilma af Klint the researcher, specifically her effort to process and understand the deeper meaning of her spiritually guided work in paintings, drawings and writing, from the 1890s to 1930s. Af Klint had an inquisitive mind. She came from a family of naval officers and nautical cartographers and approached her artistic practice with structured rigour. While she had the courage to open herself to let something larger flow through her while painting, she approached the resulting body of work in a systematic and analytic way.

Throughout her life, af Klint took copious notes, regarding her experiences and interpretations of the messages she apprehended through her spiritual practice. After completing “The Paintings for the Temple”, the artist tried to methodically gain an overview of her work and its possible meanings. In the spirit of a scientific researcher, she edited and reorganised her early notes, created a dictionary of the symbols that appeared in her works and catalogued all the works in “The Paintings for the Temple” in a portable portfolio. Remarkably, af Klint understood all of her works of art as a unified project – a notion radical for the time, but also a testament to the fact that she believed her work to have a higher purpose.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Tree of Knowledge, No. 3

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

In the series the “Tree of Knowledge” (1913-1915), Hilma af Klint maps the different spiritual planes of existence in order to picture the complexity of existence and the connection between the earth and the divine. In later series like “Series IV” (1920) and “VII” (1920), af Klint seems to focus her research on symbols such as the cross, the circle and the triangle as well as the six-pointed star and processes these sacred symbols instigate. Many of these works are characterised by a geometric idiom and involve analysis on both the macrocosmic and microcosmic level.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Tree of Knowledge, No. 5

1915

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Group 2, No title, No. 14a – No. 21

1919

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Installation view, Hilma af Klint, Moderna Museet Malmö, 2020

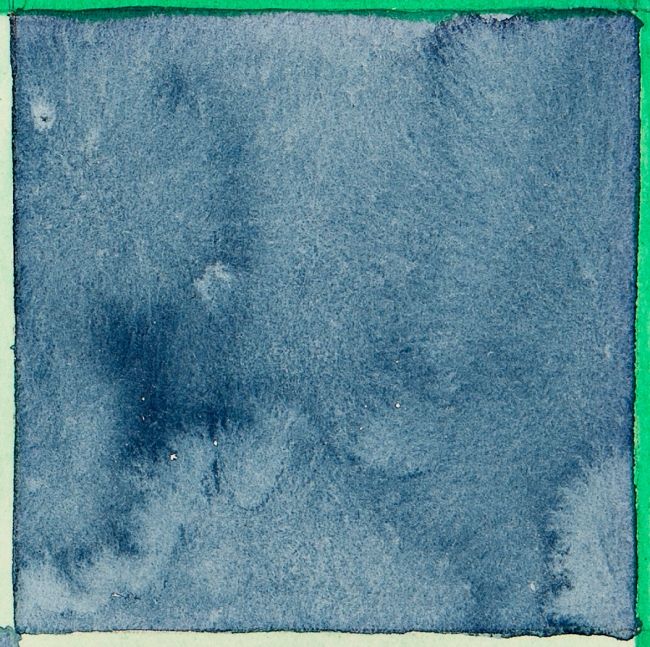

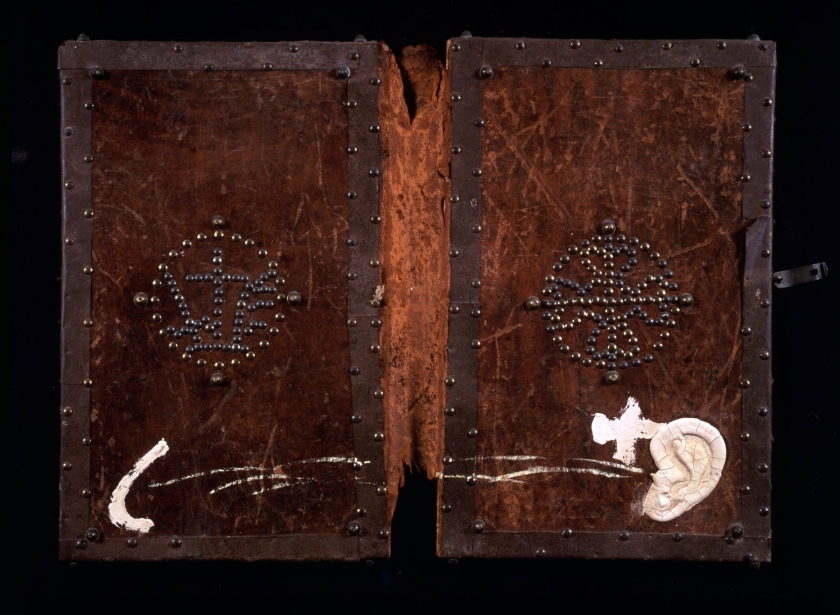

The Blue Books

In 1917, Hilma af Klint had a studio built on Munsö, where for the first time she had the possibility of seeing all “The Paintings for the Temple’s” different series in their entirety. Perhaps this is what precipitated the creation of the ten blue-bound books, a portable overview of “The Paintings for the Temple”. On each spread, a work is represented by a black-and-white photograph and a watercolour intended to give an accurate impression of the original. In some of the watercolours, af Klint adds close-ups and lets us examine the work as if through a microscope in order to further clarify what was not clear enough in the paintings. The works were organised in concordance with the order of the series. This tremendous effort demonstrates that af Klint wanted to reinvestigate and reflect on her life’s work in a systematic way and perhaps to share it more easily with others.

Text from the Moderna Museet Malmö website

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

The Atom, No. 5

1917

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

In “The Atom Series” from 1917, Hilma af Klint explored another aspect of life that could not be perceived by the human eye: the world of atoms and their energy, a science popular at the time. Apart from the first two drawings, all feature two renderings of an atom: a large one in the lower right, which represents the energy of a physical atom, and a smaller one in the upper left, which represents the atom on an etheric or metaphysical plane. In handwritten notes, af Klint describes the atom as embodying human properties. For the theosophists, whom the artist studied, the discovery of atoms, sub-particle waves etc., were seen as proof of an invisible reality beyond the perceptible world. For af Klint, atoms and thus humans were spiritual entities connected to the centre of the universe.

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Violet Blossoms with Guidelines, Series I

1919

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Botanical Studies

Throughout her life, Hilma af Klint had a deep interest in nature and botany. Her early botanical studies up to the late watercolours, convey that she was not only a keen observer, but also possessed a rigorously analytic mind, which she could apply in her endeavour to perceive aspects of existence beyond the visible.

Her botanical studies reveal a shifting focus from naturalistic renderings of plant-life as she observed it, to renderings intended to express the spiritual essence or presence beyond the visible body. In “The Violet, Blossoms with Guidelines, Series 1” (1919) she combines naturalistic renderings of the flower with a diagram of its essence. In “Blumen, Moose, Flechten” [Flowers, Moss, Lichens] (1919-1920), represented here as a facsimile, af Klint continues with her systematic investigation of the plant kingdom. She combines a diagram with the plant’s Latin name and the date of investigation, alongside properties such as joy, humility and devotion, which one can attempt to come in contact with through contemplation on the plant in question. By 1923, af Klint made yet another stylistic shift, influenced by Rudolf Steiner’s anthroposophical views on aesthetics and her visits to the The Goetheanum, the centre for the anthroposophical movement in Dornach, Switzerland. Here af Klint gave up painting geometric compositions and began instead portraying the spiritual dimension of nature in fluid watercolours.

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Vid betraktandet av blommor och träd (When considering flowers and trees)

1922

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944)

Titel saknas

1924

© Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk

Photo: Albin Dahlström/Moderna Museet

Moderna Museet Malmö

Gasverksgatan 22 in Malmö

Moderna Museet Malmö is located in the city centre of Malmö. Ten minutes walk from the Central station, five minutes walk from Gustav Adolfs torg and Stortorget.

Opening hours:

Tuesday, Thursday – Sunday 11-17

Wednesday 11-19

Mondays closed

![Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944) 'The Ten Largest, No. 7., Adulthood, Group IV' [The age of men] 1907 Hilma af Klint (Swedish, 1862-1944) 'The Ten Largest, No. 7., Adulthood, Group IV' [The age of men] 1907](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/hilma-af-klint-groupiv-the-ten-largest-no.7-web.jpg?w=650&h=874)

![Photographer unknown. 'Untitled (Klytie Pate [centre] at Melbourne Technical College)' early 1930s Photographer unknown. 'Untitled (Klytie Pate [centre] at Melbourne Technical College)' early 1930s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/photographer-unknown-untitled-klytie-pate-at-melbourne-technical-college-early-1930s-web.jpg?w=840)

![Fred Tomaselli (American, b. 1956) 'Untitled [Datura Leaves]' 1999 Fred Tomaselli (American, b. 1956) 'Untitled [Datura Leaves]' 1999](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/tomaselli-untitled-datura-leaves-1999-web.jpg?w=650&h=813)

You must be logged in to post a comment.