Exhibition dates: 24th April – 9th August 2009

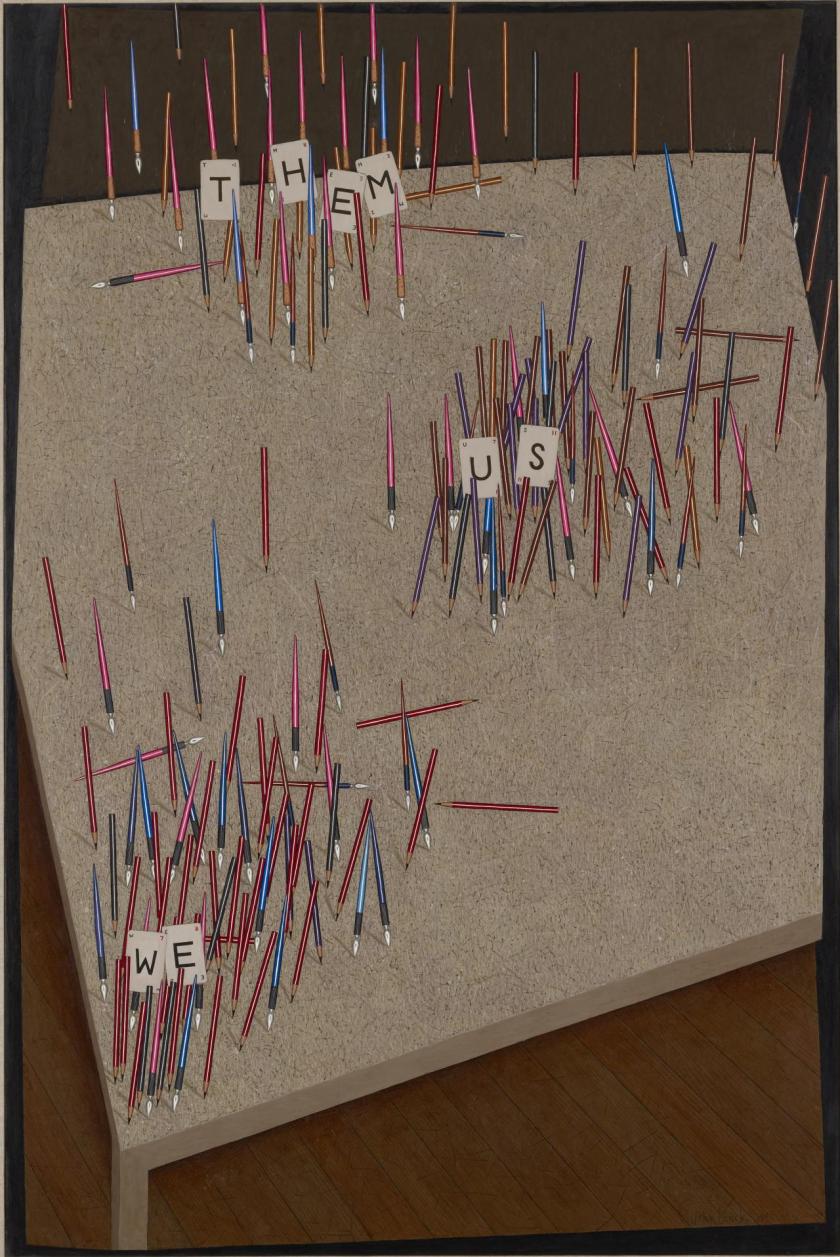

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The chase

1959

Oil on composition board

100.2 x 121.8 cm

Grishin, o94

Private collection, Melbourne

© Helen Brack

“One either has a subject, or one has not.”

John Brack

This is a solid retrospective of the work of the Australian artist John Brack (1920-1999) presented by the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. John Brack is, quintessentially, an Australian and more specifically a Melbourne artist. Melbournians have a love hate relationship with his work – loving the earlier paintings that view the working classes of 1950s Melbourne through a nostalgic, humorous, sardonic lens (when originally the popularity of the work in the 1950s/60s was, as Robert Nelson has observed, mistakenly identified with ridicule of the subject matter)1 while finding the later work of massed pencils, postcards, deities and wooden people mystifying, cold and elusive.

Brack saw his paintings of suburbia as honest portrayals of the new milieux. His sparse, graphic style evidenced the emotionally distanced relationships between space and people in the new cityscapes and best suited his cerebral approach to the subject matter. Men become mannequins with skeletal faces that hover menacingly behind the barmaid in The bar (1954, above), an amorphous mass of brown-suited humanity. Two women are portrayed in all their high-collared stiffness in the painting ‘Two typists’ (1955, above), their stylised faces, black hat and hair surmounted by hanging, disembodied legs at the top of the painting. These two women then reappear at bottom right in one of Brack’s most famous paintings, Collins St, 5p.m. (1955, above) subsumed into the two lines of people wearily trudging home from a day’s work at the office.

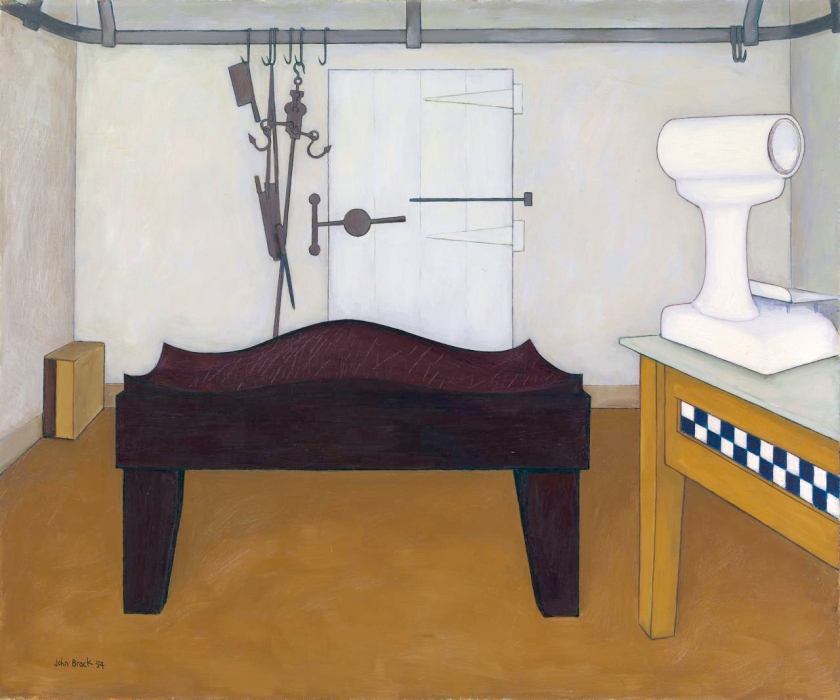

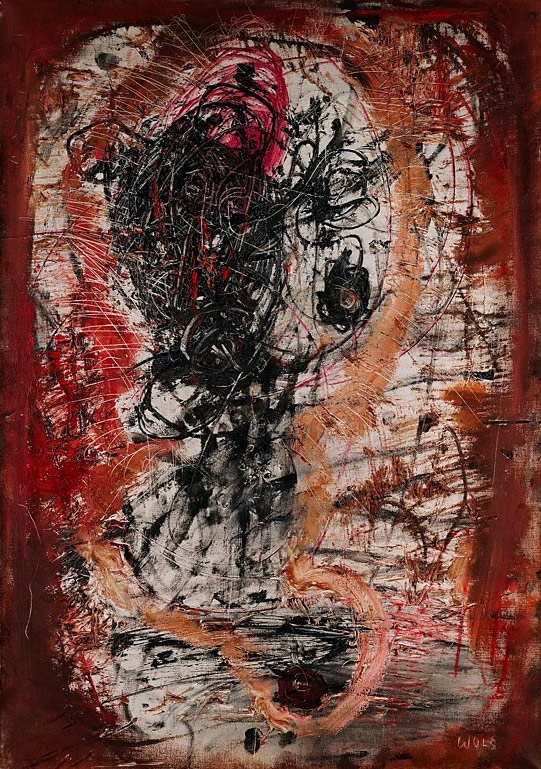

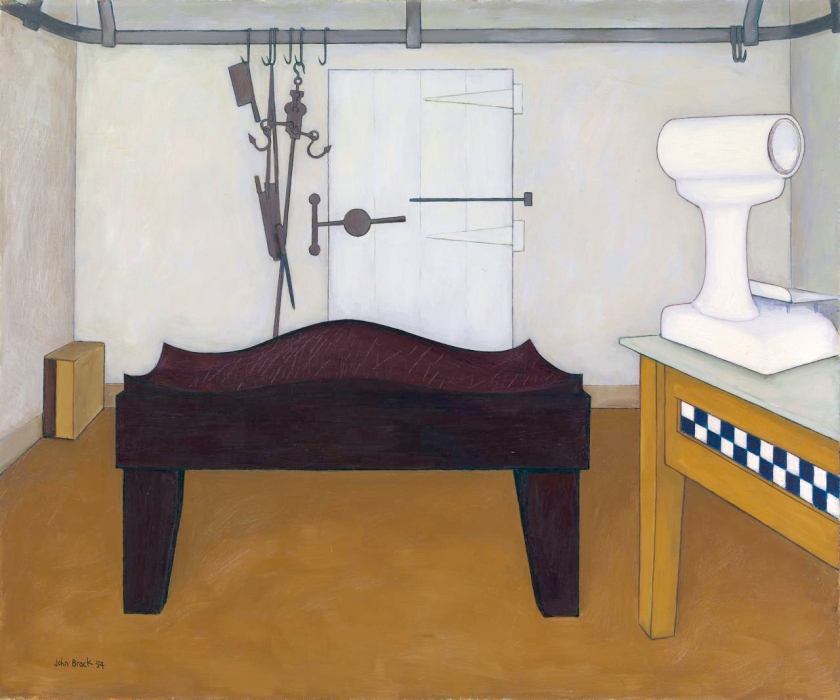

Brack’s early paintings are full of stylised metaphor – for example the clinical emptiness of space, the implied threat of hanging ‘instruments’ in ‘The block’ (1954, above) or the decapitated bird-like alienation of the fish head in The fish shop (1955, above) – offer comment on the nature of suburban life: ordered, dead, soulless surfaces, facades behind which life seethes. Brack recognises the slightly macabre beauty of these industrial spaces, their form and purpose, where no one had recognised them before. There are oversized teeth (The veil, 1952), large hands, the fleshy pink of faces (The barbers shop, 1952) and the tribal mask of a face in Man in pub (1953) where man becomes fragment. Above all there is a simplicity and eloquence in line and form grounded in a limited palette of ochres, yellows, greys, blacks, whites and browns. These are the colours of the early cave painters and it’s poignant that Brack uses them so effectively to anchor his subject matter both in history, memory and the present of contemporary life, a life we still recognise intimately over fifty years later.

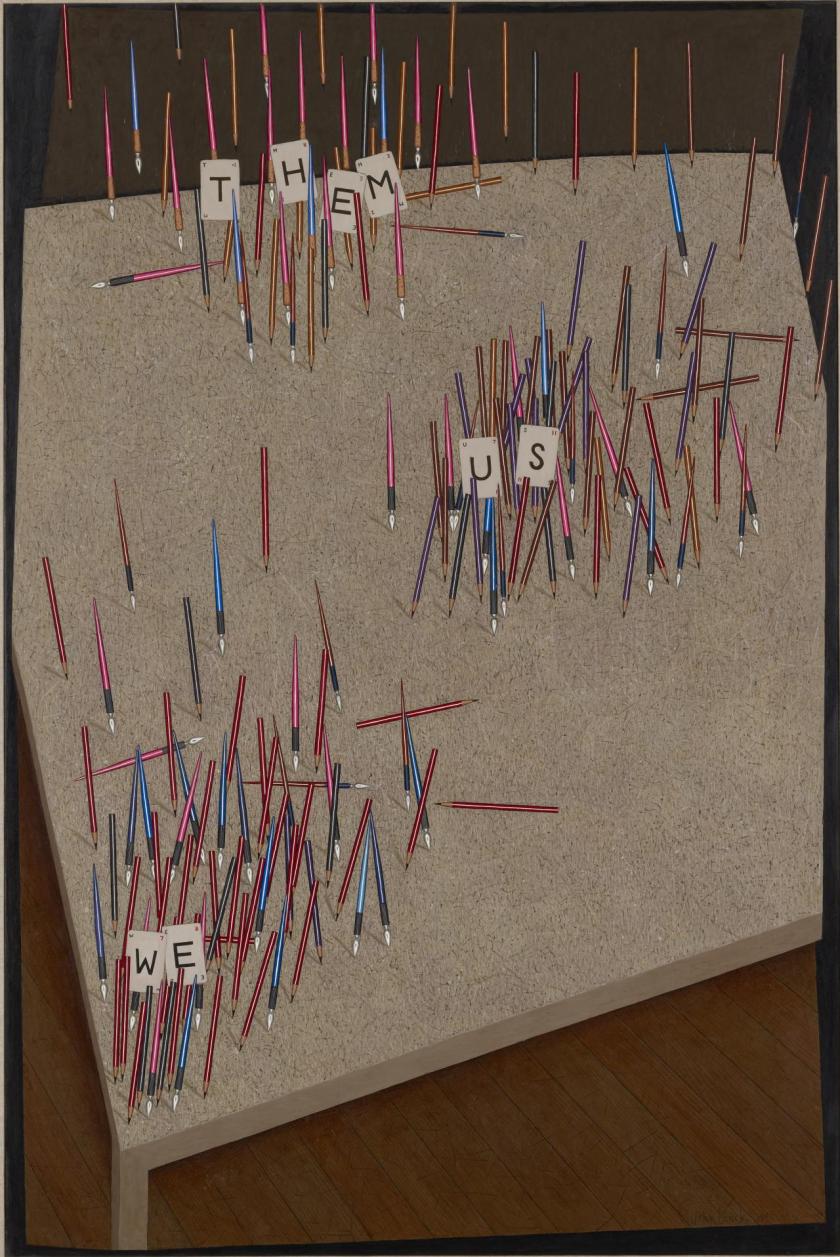

Here is the ‘Human Condition’ writ large (with capitals!), the humility of professions such as butchers, seamstresses, typists and barmaids (with their limited control of the environment) portraying the body of the worker, as in Satre’s ‘Nothingness’,2 living the tedium of suburban life whilst wanting to flee the anguish of this existence into the desirable light of the future toward which man projects himself. This a theme that Brack develops in the later paintings with their stilted, cerebral investigation of existentialism. These paintings offer a more general contribution to a view of the human condition – love and hate, we, us, them, pros and cons – a view originally grounded in the suburbs of Melbourne but elevated to the ethereal, paintings that seem to lack material substance but offer a hyper-refined conceptual aesthetic.

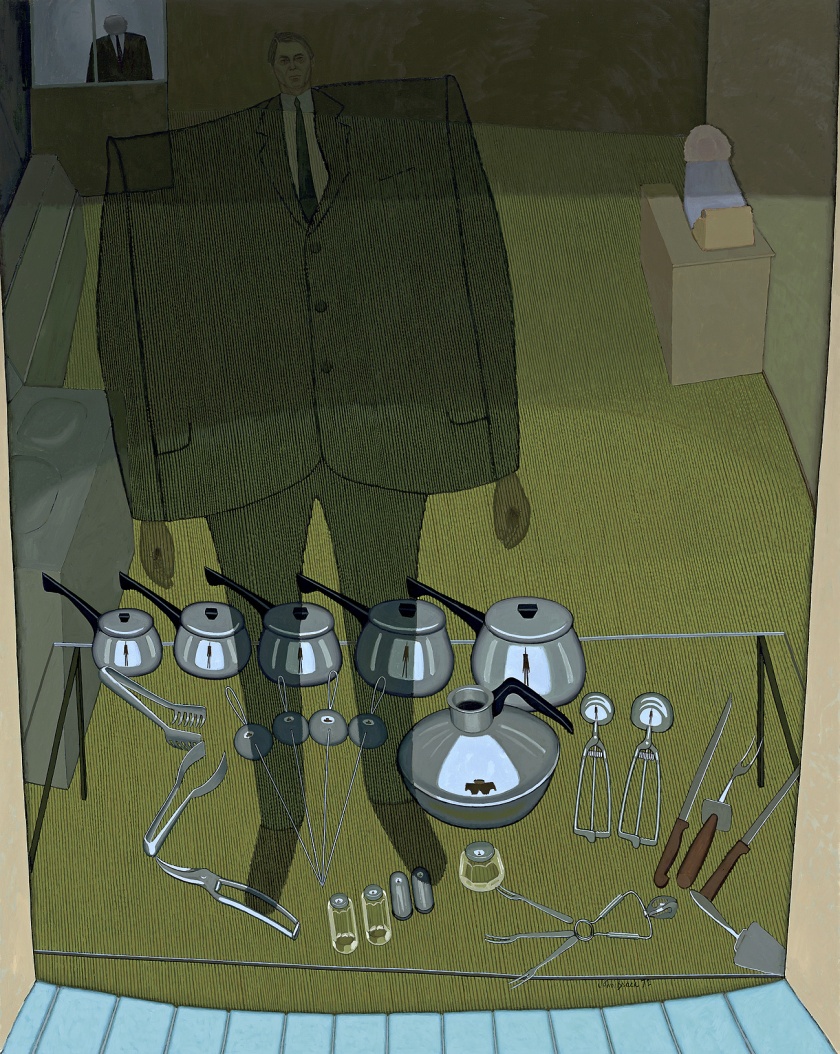

Sticks and Stones Will Break My Bones But Pencils Will Never Hurt Me

As early as Knives and forks (1958) and The playground (1959) we can observe the beginnings of the spaces of his later pencil paintings with their uniting of form, line and plane (think the planes of Cezanne). The later work is literally much colder, the palette now blues instead of the warmer ochres and yellows and this change is very obvious when you walk around the exhibition. There is an emotional distance here – from human contact and the warmth of company. Ronald Miller observed in 1970 that Brack’s work is about the rituals of life, about states of uneasy poise and vulnerability, about realities behind facades but in the later work the paintings become the facades: gone are the ambiguities and vulnerabilities to be replaced by an altogether different ‘order’ of existence.

We see in paintings such as Souvenirs (1976), We, Us, Them (1983), The pros and cons (1985) and Watching the flowers (1990-91 – see all below) how the canvas has become a stage set replete with turned up edges, spaces of ritual performance containing generalised metaphors for the nature of human existence, metaphors with universal themes. In his investigation of the universal Brack looses sight of the personal. His towers made of playing cards, his thrusting planes, the military precision of his opposing armies of goose-steeping pencils lack empathy for the thing that he was searching to be attuned with: the nature of existence, the human condition.

As Sartre observed,

“To apprehend myself as seen is, in fact, to apprehend myself as seen in the world and from the standpoint of the world. The look does not carve me out in the universe; it comes to search for me at the heart of my situation and grasps me only in irresolvable relations with instruments. If I am seen as seated, I must be seen as “seated-on-a-chair,” … But suddenly the alienation of myself, which is the act of being-looked-at, involves the alienation of the world which I organise. I am seated on this chair with the result that I do not see it at all, that it is impossible for me to see it …”3

.

This is the point that John Brack reached: through his desire to paint universal themes he was unable to visualise and apprehend himself as seen in the world from the standpoint of the world. It feels (yes feeling!) that he was alienated from the very thing he sought to portray – how the personal and the universal are one and the same.

Brack’s ‘failure’ as an artist (if indeed it can be called that) is not, as Robert Nelson has suggested, “because he didn’t talk enough or wisely enough to negotiate his way out of a misunderstanding” (that his work was sardonic). On the contrary I believe his ‘success’ as an artist is that he painted exactly what he wanted to paint in the time and place that he wanted to paint it. His later work might strike some as cold and impenetrable but if one looks clearly, with a steady eye, there still beats a heart under that chill exterior, a heart grounded in the life of suburban Melbourne. In the end Brack returns to the beginning, still exploring, still searching.

.

As T.S. Eliot wrote in one of The Four Quartets,4

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

Dr Marcus Bunyan for the Art Blart blog

.

Many thankx to the NGV for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

- Nelson, Robert. The Age newspaper. Melbourne, Friday 24th April, 2009

- “We learn that Nothingness is revealed to us most fully in anguish and that man generally tries to flee this anguish, this Nothingness which he is, by means of “bad faith.” The study of “bad faith” reveals to us that whereas Being-in-itself simply is, man is the being “who is what he is not and who is not what he is.” In other words man continually makes himself. Instead of being, he “has to be”; his present being has meaning only in the light of the future toward which he projects himself. Thus he is not what at any instant we might want to say he is, and he is that towards which he projects himself but which he is not yet.”

Barnes, Hazel. Introduction to Jean-Paul Satre’s Being and Nothingness. London: Methuen, 1966, pp. xvii-xix

- Satre, Jean-Paul. Being and Nothingness. (trans. Hazel Barnes). London: Methuen, 1966, p. 263

- Eliot, T.S. “Little Gidding” from The Four Quartets (1942)

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The barber’s shop

1952

Oil on canvas

63.7 × 76.3 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1953

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Two typists

1955

Oil on canvas

51.0 × 61.5 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

The Joseph Brown Collection. Presented through the NGV Foundation by Dr Joseph Brown AO OBE, Honorary Life Benefactor, 2004

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Collins St, 5 p.m.

1955

Oil on canvas

114.8 × 162.8 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1956

© National Gallery of Victoria

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The bar

1954

Oil on canvas

97.0 × 130.3 cm irreg.

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with the assistance of Peter Clemenger AM and Joan Clemenger, Elena Keown Bequest, Spotlight Foundation, NGV Foundation, Ross Adler AC and Fiona Adler, Bruce Parncutt and Robin Campbell, Marc Besen AO and Eva Besen AO, the Bowness Family, Lindsay Fox AO and Paula Fox, Dorothy Gibson, Rino Grollo and Diana Ruzzene Grollo, Ian Hicks AM, the NGV Women’s Association and donors to the John Brack Appeal, 2009

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The conference

1956

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The block

1954

Oil on canvas

59.0 × 71.5 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Presented through The Art Foundation of Victoria by Dr Joseph Brown, AO, OBE, Honorary Life Benefactor, 1999

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The fish shop

1955

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The new house

1953

Oil on canvas on board

127.0 x 55.8 cm

Private collection, Brisbane

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Self-portrait

1955

Oil on canvas

81.4 × 48.3 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with the assistance of the National Gallery Women’s Association, 2000

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The unmade road

1954

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Subdivision

1954

Oil on canvas

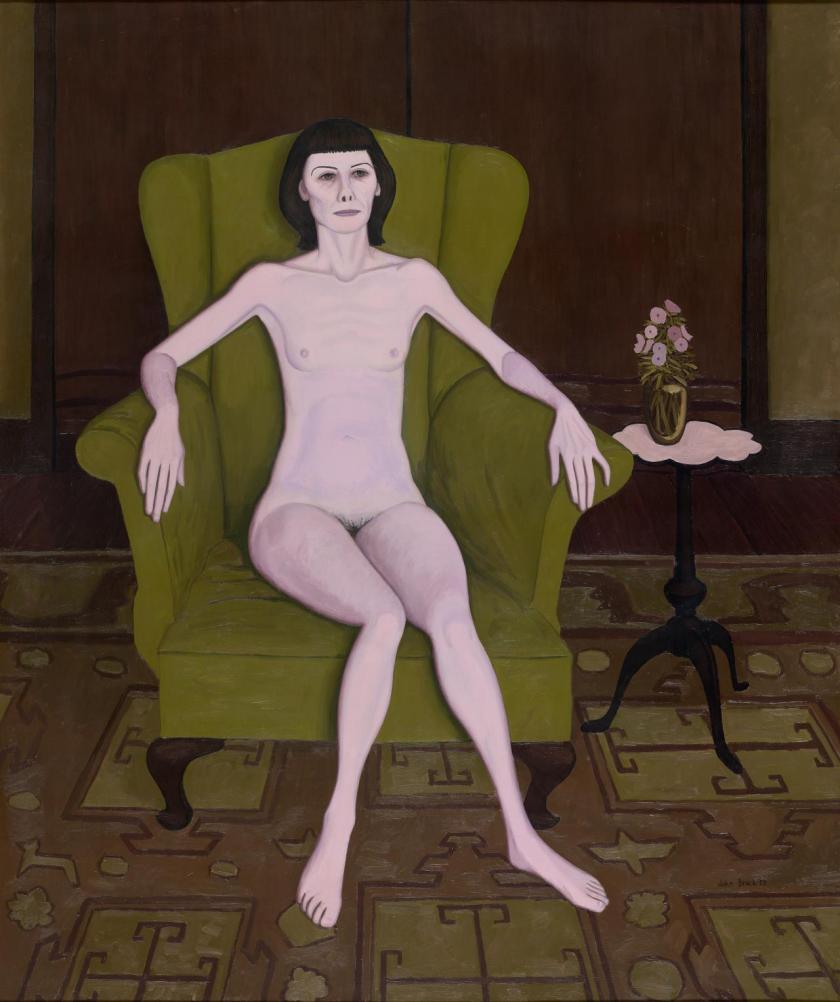

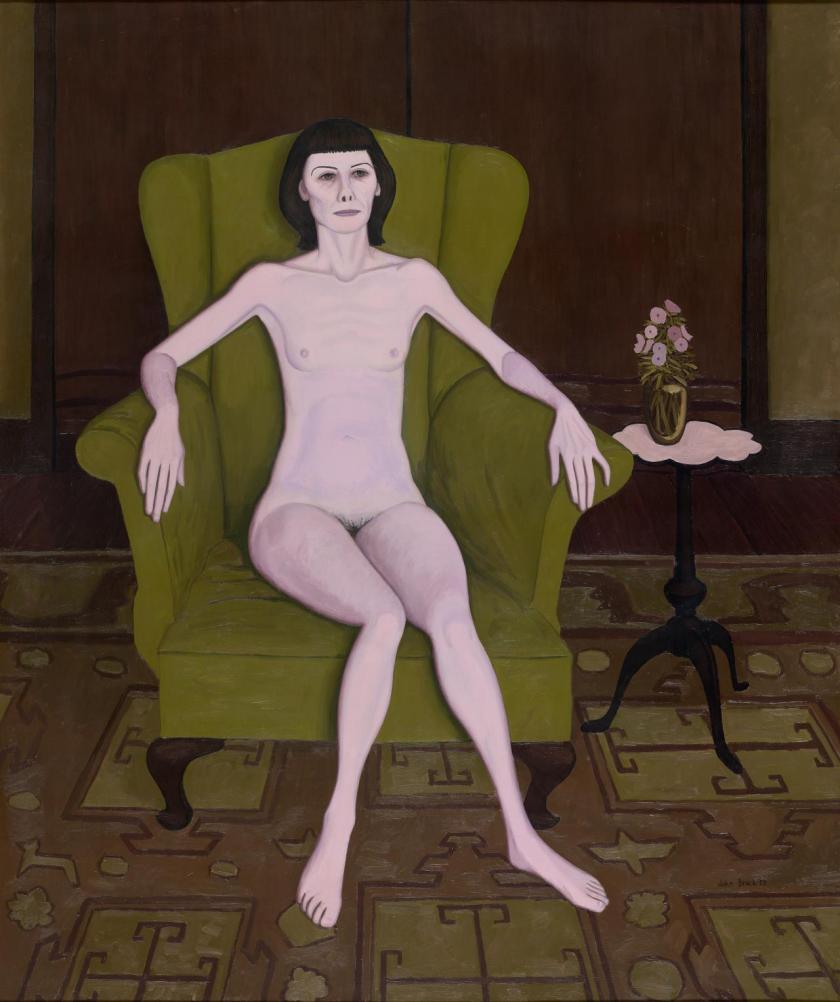

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Nude in an armchair

1957

Oil on canvas

127.6 × 107.4 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1957

© National Gallery of Victoria

“What I paint most is what interests me most, that is, people; the Human Condition, in particular the effect on appearance of environment and behaviour… A large part of the motive is the desire to understand, and if possible, to illuminate …”

John Reed, New Painting 1952-62, Longmans, Melbourne, 1963, p. 19.

Opening 24 April, the National Gallery of Victoria will present a major retrospective of the work of John Brack, the first in more than twenty years. This exhibition will survey John Brack’s complete career, incorporating over 150 works from all of his major series. John Brack will bring together a significant body of the artist’s paintings and works on paper, including pictures that have developed ‘icon status’ and others that have rarely, if ever, been seen publicly since they were first exhibited.

Kirsty Grant, Senior Curator Australian Art, NGV said that more than any other artist of his generation, John Brack was a painter of modern Australian life.

“John Brack painted images which explored the social rituals and realities of everyday life. Long considered the quintessential Melbourne artist, Brack’s images of urban and suburban Melbourne painted during the 1950s drew attention for their novelty of subject and instantly recognisable references. His work is much broader however and in this exhibition we will see the continuity throughout his career of his fundamental interest in people, human nature and the human condition,” said Ms Grant.

Frances Lindsay, NGV Deputy Director said John Brack was widely considered one of Australia’s greatest twentieth century artists.

“The NGV has enjoyed a long association with John Brack: he worked as an assistant frame maker at the gallery in 1949, became head of the National Gallery School in 1962, and the NGV was also the first public institution to purchase one of his works. Brack’s iconic works are certainly the highlight for many visitors to the Gallery. We are thrilled to be continuing this special relationship by presenting this important and timely retrospective.”

The exhibition will be displayed chronologically, beginning with some rare early student works. Each phase of Brack’s practice will be explored, from his well-known urban scenes of the 1950s to the highly symbolic paintings from the 1970s. Many of Brack’s most familiar paintings are included in the exhibition such as Collins St, 5p.m, The bar and The Old Time.

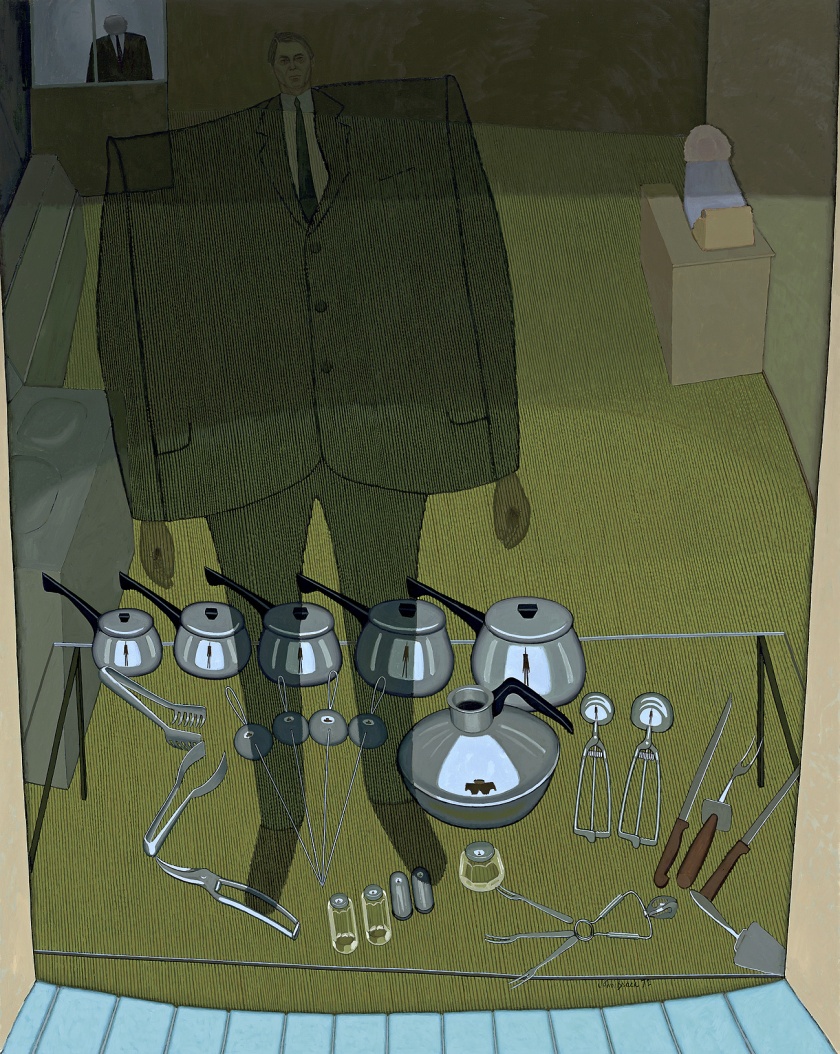

Brack produced compelling pictures which captured the essential characteristics of his subjects involved in everyday activities and, in some of his most engaging series, he depicted the characters of the racecourse, children at school and professional ballroom dancers. Throughout his career Brack also painted the nude, still life subjects and portraits, both of family and friends – including artists Fred Williams and John Perceval – as well as commissioned subjects, such as Barry Humphries as his alter-ego Edna Everage. During the 1970s Brack replaced the human figure with an assortment of everyday implements including cutlery, pens and pencils which he used as metaphors for the complexities of human behaviour and relationships.

Press release from the NGV website [Online] Cited 26/07/2009 no longer available online

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Inside and outside (The shop window)

1972

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Latin American Grand Final

1969

Oil on canvas

167.5 x 205.0 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased, 1981

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Portrait of Fred Williams

1979-80

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The pros and cons

1985

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

The Battle

19181-83

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

We, Us, Them

1983

Oil on canvas

183.4 × 122.4 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased through The Art Foundation of Victoria with the assistance of Mr Philip Russell, Fellow, 1983

© Helen Brack

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Kings and Queens

1988

Oil on canvas

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Souvenirs

1976

John Brack (Australian, 1920-1999)

Watching the flowers

1990-91

Oil on canvas

The Ian Potter Centre:

NGV Australia

Federation Square

Corner of Russell and

Flinders Streets, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Everyday 10am – 5pm

National Gallery of Victoria website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.