Exhibition dates: 27th April to 13th August 2017

Curator: Dr Martin Engler, Head of the Collection of Contemporary Art, Städel Museum

Co-curator: Dr Jana Baumann, Städel Museum

Artists: Volker Döhne, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Tata Ronkholz, Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse, Thomas Struth and Petra Wunderlich

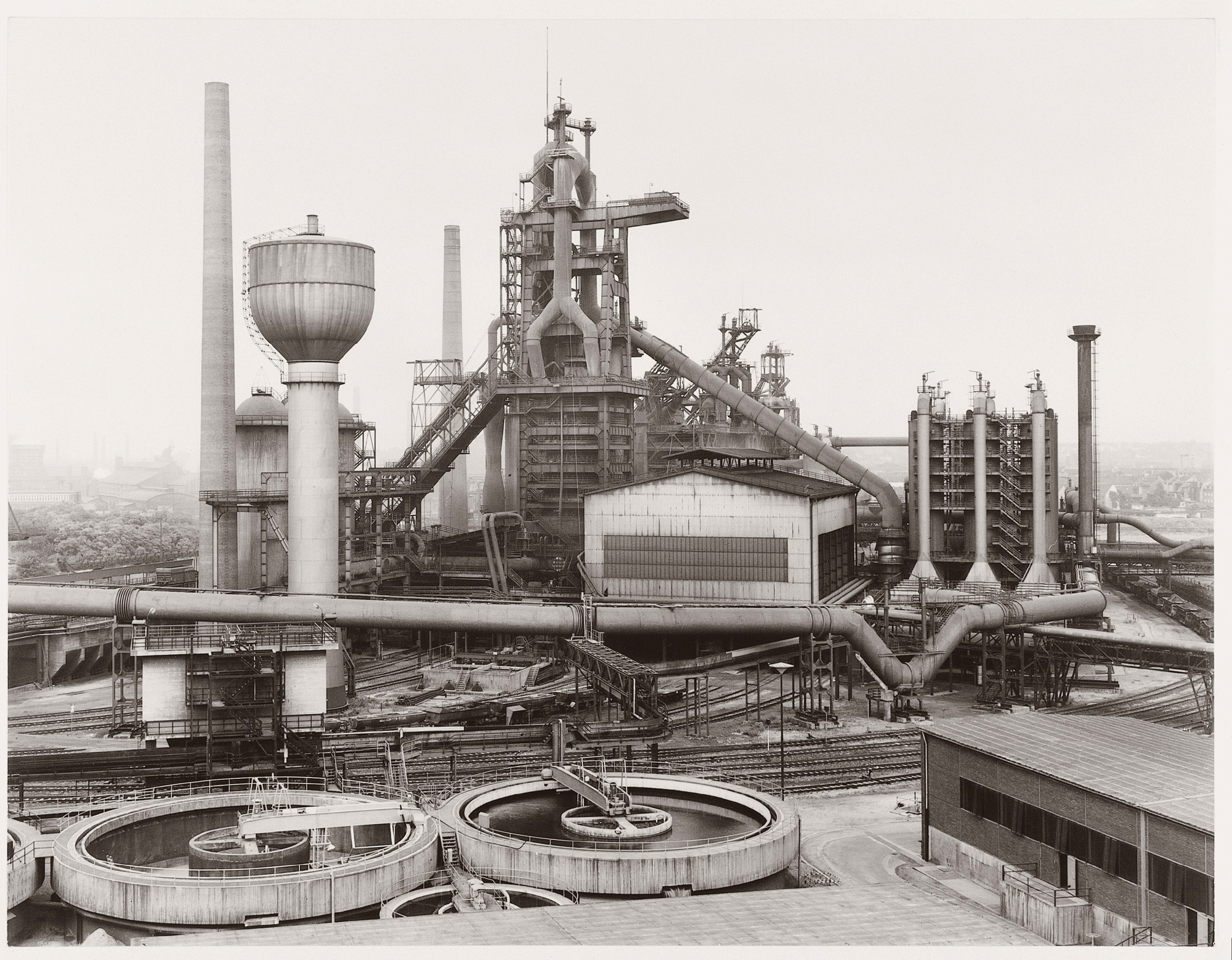

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Gutehoffnungshütte, Oberhausen, Ruhrgebiet

1963

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

75.3 x 91.4cm

Art Collection Deutsche Börse Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher

“What the teachings of Bernd and Hilla Becher sparked off – and their students developed further – is a new conception of the artwork according to which the boundaries between sculpture, painting and photography dissolve in terms of media and aesthetics alike. In other words, in the very moment in history when photography emancipated itself to become an independent medium, it sounded its own death knell.” (Press release)

WHAT ABSOLUTE RUBBISH – the second sentence, that is!

Just look at the photographs as pictures.

The Bechers and their students’ photographs might invoke a new concept of the pictorial but that does not mean the death of photography far from it. In fact, this conceptualisation opens up an expanded terrain of becoming for photography (continuing the theme of the last post on the work of Walker Evans). In this sense, the work of these artists is vital to an understanding of the place of photography within the observation, construction and taxonomy of contemporary culture and its pictorial representation. Everything in contemporary art relates not to beauty or aesthetics but to the social.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Städel Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. For more information please see the interactive website.

One of the most radical changes in art’s relation to its aesthetic, media, and economic contexts is closely associated with the students of the first Becher Class at the Düsseldorf art academy – but even more so with the names of their teachers, Bernd and Hilla Becher. The exhibition brings together 200 major works, some in large format, by these important artists, as well as a selection of their early works.

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Half-Timber Houses

1959-1961/1974

Silver gelatine print on baryta paper

152.4 x 112.5cm

Sammlung Deutsche Bank

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher

“This is a purely economic architecture […]. It is erected, used and discarded.”

Becher, Bernd and Hilla cit. in: “Beauty in the Awful”, in: Time. The Weekly Newsmagazine, 94, 10, 5 September 1969, p. 69.

The same subject in nine different types: as in a scientific documentary the photos show nine coal silos before a neutral light-grey background. The Bechers’ photos all follow the same approach: from an elevated vantage point the artists photograph details and total views of objects or entire industrial facilities and position them centrally in the picture. Every detail is razor sharp. The sky is predominantly overcast. The photographs are black and white. Nothing is to distract from the subject, to guarantee a presentation that is as objective as possible.

Bernd Becher and Hilla Wobeser begin to collaborate in 1959. At the time both study at the art academy Düsseldorf. Two years later they marry. During the following five decades the artist couple produces mostly tableaus of several parts – consisting of three, nine, twelve or more photos; they call them typologies. Their subjects are disused headstocks, furnaces, oil refineries, water reservoir towers, grain silos, gasometres or even half-timbered houses in former workers’ settlements – all of them testimonies of a declining industrial culture.

The Bechers depict the half-timbered houses from the Siegerland in a sober and restrained fashion. The picture removes the buildings from their original context. One view follows the next. Thus the form of the single building becomes more important than its function. In the photographs the half-timbered houses become aesthetic objects with a sculptural character. Bernd and Hilla Becher do not present their images individually, but in a grid. Not the single photo is the work, but the total of the typology is.

When Hilla and Bernd Becher presented their works at the Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in 1969, this coincided with an exhibition on US-American minimal art – a juxtaposition that was to prove programmatic. In 1972 the American sculptor Carl Andre mentioned the insightful connection of the Bechers’ works and the movements of minimal and conceptual art. This prominent, art-theoretical connection significantly contributed to the great international success of the Bechers. This is also why – especially in the USA – the two are considered concept artists more than photographers. …

The Bechers’ method of working – ostensibly – is concerned with sobriety and anonymity, rigidity and objectivity. They work in series, where the whole and a part of this whole, total view and detail are balanced. Setting their photographs into the context of sculpture, they test the boundaries of the genres of photography and sculpture. Working and presenting their works in series, they move the photograph beyond the individual work: the viewer can never see everything at once; instead the eye oscillates between detail and general context.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website Nd [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Half-Timber Houses (detail)

1959-1961/1974

Silver gelatine print on baryta paper

152.4 x 112.5cm

Sammlung Deutsche Bank

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher

Bernd Becher (German, 1931-2007) and Hilla Becher (German, 1934-2015)

Half-Timber Houses (detail)

1959-1961/1974

Silver gelatine print on baryta paper

152.4 x 112.5cm

Sammlung Deutsche Bank

© Estate Bernd & Hilla Becher

The Becher School of Photography. An American Perspective – Vortrag von Alexander Alberro

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Weidengasse Cologne VIII 1977

1977 (2013)

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

42.6 x 36.7cm

Loan from the artist

© Candida Höfer, Köln; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Untitled (Colourful)

1979 (2014)

Colour print from colour transparency

37 x 47cm

Private collection

© Volker Döhne, Krefeld 2017

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Interior 1 D

1982

Chromogenic colour print

47 x 57cm

Loan from the artist

© Thomas Ruff; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

Doorman, Passport Control

1982 (2007)

Inkjet print

43.2 x 52.5cm

Loan from the artist / Courtesy Sprüth Magers

© Andreas Gursky / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017 / Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

Moedling House

1982-1984

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

66 x 80cm

Loan from the artist

© Axel Hütte

Petra Wunderlich (German, b. 1954)

Fossa Degli Angeli, Italy

1989

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

61 x 75.2cm

Private collection

© Petra Wunderlich; VG Bild-Kunst 2017

From 27 April to 13 August 2017, the Städel Museum is staging a comprehensive survey on the Becher Class at the Düsseldorf art academy and the major paradigm shift in the medium of artistic photography with which the Bechers and their students are associated. With the aid of some 200 photographs by Volker Döhne, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Tata Ronkholz, Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse, Thomas Struth and Petra Wunderlich – a group of whom some enjoy international renown and others are due for rediscovery – the exhibition will examine the influence exerted by Bernd and Hilla Becher on their students at the Düsseldorf school. What unites the students’ works with those of their teachers? How do they differ? Is there really such a thing as the “Becher School” or is it ‘merely’ a matter of several highly successful photographers who happened to be studying at the ‘right place’ at an especially propitious moment in history? And how have those artists influenced our present conception of what a picture is? Taking the artist duo’s work as a point of departure, the exhibition “Photographs Become Pictures. The Becher Class” will acquaint viewers with the radical changes in the medium of artistic photography that became manifest in the works of the Becher pupils in the eighties and above all the nineties, and investigate the art-historical impact of this development up to the very present. It will feature major large-scale works as well as key early endeavours by the members of what is presumably the most influential generation of German photographers in the field of fine art.

The students of the first in a long line of Becher Classes at the Düsseldorfer art academy introduced elementary changes to contemporary art’s aesthetic, media and economic contexts. They not only contributed decisively to shaping international photography in the 1990s, but also fundamentally redefined the status and perception of artistic photography in general. Their works can be considered as one of the most self-confident emancipations of photography as art in the mediums history, while at the same time reflecting the (not merely digital) moment when the boundaries between the media dissolve.

“Bernd and Hilla Becher’s first – meanwhile world-famous – students played a tremendously important role in establishing photography as an expressive medium on a par with other art forms. The nine artists featured in our show occupy a realm where the distinction between painting and photography is no longer clear. The permeability of the boundary between the media is deliberate in their work, and in that respect they mirror one of the key focuses of the Städel Museum’s collection of contemporary art,” observes Städel director Dr Philipp Demandt. And exhibition curator Dr Martin Engler adds: “What the teachings of Bernd and Hilla Becher sparked off – and their students developed further – is a new conception of the artwork according to which the boundaries between sculpture, painting and photography dissolve in terms of media and aesthetics alike. In other words, in the very moment in history when photography emancipated itself to become an independent medium, it sounded its own death knell.”

The founding of a chair for artistic photography at the Düsseldorf art academy in 1976 provided perhaps the single most important impulse for a change in how the medium of photography was perceived. In close cooperation with his wife Hilla Becher, Bernd Becher held that chair until 1996. Even before their appointment to the Düsseldorf school, the Bechers had been taking pictures of historical industrial architecture, subscribing to a work concept that exceeded the scope of a common documentary approach in photography. They portrayed mining headframes, blast furnaces, gas tanks, water towers and other testimonies to a vanishing industrial culture – frontally, in central perspective, with fascinating depth of field, and where possible before the backdrop of a uniformly grey sky. They arranged the individual shots in grids to form large-scale tableaus they called typologies. The concern here was no longer merely the illustration of reality, but its perception. Reality could no longer be depicted singly, but only in a multiplicity of simultaneous images. From the formal aesthetic point of view, the staging of the pictorial subjects was now far more than documentary in nature. The affinity to minimal and concept art – evident in the rigour of the pictorial vocabulary, the industrial aesthetic and the new perception of a work in stages – is unmistakable.

Especially in their early work, the students of the first Becher Class explored their teachers’ artistic strategy with great intensity. Yet as they continued to pursue it in the nineties, they did so ever more independently, and in their own highly individual styles. With the aid of various strategies in terms of scale, presentation and motif, and not least of all with abstract pictorial inventions provoked by digital image techniques, they took the interpenetration of the mediums of painting and photography to an extreme. The result was a new concept of the picture that blurs aesthetic and media distinctions. “The dissolution of media boundaries, but also the use of technical innovations, are characteristic of the works of the first Becher Class. It is here that the impact of a changing media culture is felt,” explains Dr Jana Baumann, the co-curator of the exhibition.

A show devoted to such a complex phenomenon on the one hand, and such productive teaching activities on the other, must inevitably be limited in scope. “Photographs Become Pictures” concentrates deliberately on the students of the early years of the Becher Class, beginning with Höfer, Döhne, Hütte and Struth in 1976 and ending with the completion of Gursky’s and Sasse’s studies in 1987/1988. In retrospect, it is precisely in the heterogeneity of the first Becher Class – with its wide range of approaches that have influenced our present-day understanding of the pictorial image – that the success of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s teachings is evident.

Candida Höfer (b. 1944) is known above all for her pictures of public interiors such as libraries, universities, museums and waiting rooms. Nevertheless, the purely documentary aspect is ultimately of secondary importance to her, as is also true of her teachers. Particularly when she turned to colour photography, she began producing iconically clear shots of meaning-charged interiors extremely striking in their rigorous aesthetic. In composition, repetition and rhythm as well as the sculptural emphasis, Höfer’s formal staging of her interiors is reminiscent of the Becher typologies.

A distinct affinity to the typologies is also evident in early street shots by Thomas Struth (b. 1954), such as West Broadway, Tribeca, New York (1978) or Sommerstrasse, Düsseldorf (1980). He proceeded in a manner similar to his teachers, but broadened his spectrum of motifs. He is concerned in his work with cultural structures; in addition to streets he also depicts museums or religious cult sites and portrays families. With the aid of social and ethnological allusions he reveals orders and interrelationships, thus achieving a universal survey of human and their lifeworld in imagery.

Petra Wunderlich‘s (b. 1954) black-and-white series depict details of churches or quarries that the artist has introduced to a new, abstract compositional framework. By this method she reduces architecture visually to its stereometric tectonics in such a way that elementary architectonic forms unexpectedly emerge from the “broken” surfaces of nature. Wunderlich’s photographs, like those by the Bechers, can be read as sociological and historical testimonies.

The workgroups of Volker Döhne (b. 1953) closely resemble Bernd and Hilla Bechers’ typologies with regard to concept and motif alike. He developed series such as Small-Scale Iron Industry (1977/78) or Small Railway Bridges and Underpasses in the Bergisches and Märkisches Land (1979). With his experimental Colour (1979) series, he then emancipated himself from his teachers.

Tata Ronkholz (1940-1997) was interested primarily in factory gates, shop windows, beverage kiosks and snack bars, which she photographed in the even light of grey days. Many aspects of these works are strongly reminiscent of the Becher photographs: the consistent placement of the subject at the pictorial centre, the unchanging size of the prints, but also the serial, typologically comparative approach.

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) is likewise deeply indebted to his teachers’ serial method, which we encounter in his work in ever-different formulations. His portraits as well as the strongly enlarged nocturnal shots of, in part, found material, convey his fundamentally sceptical attitude towards photography’s claim to truth and documentation. His persistent investigations of new pictorial sources and technologies are perhaps the most impressive demonstrations of the manner in which Ruff continues the approach of Bernd and Hilla Becher.

Axel Hütte‘s (b. 1951) early architectural details investigate social situations using a mode of photographic expression distinguished by distance and anonymity. Within this context, he devotes himself as much to spoiled landscapes as to supposedly untouched nature which nevertheless has always been formed by human intervention. A conspicuous aspect of his work is the strong reference to historical landscape painting, whose formal compositional principles he both copies and deconstructs. Whereas the Bechers directed their attention to the sculptural or conceptual potential of their pictures, Hütte focusses on painting as the leading medium of modern art.

Jörg Sasse (b. 1962) initially devoted himself to highly artificial and at the same time prosaic arrangements of petit-bourgeois domestic culture. His later “tableaus” represent a virtual antithesis to the reductive rigour of these early works. Using digital and analogue techniques alike, he began processing found pictures as well as images of his own making, in which context he blurred the distinction between painting and photograph beyond recognition.

Andreas Gursky‘s (b. 1955) early photographs are likewise characterised by a keen interest in everyday surroundings – the private as well as the public sphere, the context of work as well as leisure time. Like Sasse, he investigates the aesthetic boundary between photographic and painterly image production. By means of digital manipulations he uses to duplicate and mount the pictorial motif to the point of abstraction, he creates perplexing pictorial architectures that merge construction and reality in large-scale colour prints.

The development of the Becher Class shows how concept art’s expanding notion of the artwork led to a new concept of the pictorial including photography. What the teachers introduced in rudiments was taken by their students and the following generation of artists to a momentous change in the picturing of reality. The realisation that photography cannot reproduce reality impartially does not detract from the medium. On the contrary, it means an enhancement in terms of artistic potential. What is more, the lack of focus in the portrayal of reality – in the literal and figurative sense alike – enriches photography’s complexity. It is not least of digital changes that enables innovative pictorial invention. Yet the boundaries of the photographic image also became fluid in the development from individual work to typology and series, and from detail to overall image. The answer to all questions about the significance, classification, doctrine and conception of what we refer to as the “Becher School” can thus be found in an insight as simple as it is surprising: in the very moment in history when photography emancipated itself to become an independent medium, it sounded its own death knell.

Press release from the Städel Museum

At left in the bottom image, Axel Hütte (b. 1951) 15 artists USA (David McDermott, Stephen Prina, Mike Kelley, Peter McGough, David McDermott, Doug Starn, Mike Starn, Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Ross Bleckner) 1988 (2003)(detail)

Candida Höfer (left) and Thomas Struth (b. 1954) Louvre 3, Paris 1989 1989 (2012) (right)

Thomas Struth (b. 1954) Paradiese 09 Xi Shuang Banna, Provinz Yunnan, China, 1999

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Paradiese 09

Xi Shuang Banna, Provinz Yunnan, China, 1999

Thomas Ruff (b. 1958) House No. 1 1987 (right)

Axel Hütte (b. 1951)

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

Castellina

1992 (2015)

Chromogenic colour print

98.4 x 120.3cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung © Axel Hütte

In the bottom image, Thomas Struth (b. 1954) The Consolandi Family, Mailand, 1996 (2014) (left)

Exhibition views “Photographs Become Pictures. The Becher Class”

Photo: Städel Museum

The Bechers

For their photographs Bernd and Hilla Becher are awarded the “Golden Lion” in the category of “sculpture” at the Venice Biennale in 1990. How is that possible? Surprisingly at the time there was no separate category for photography at the Biennale. But this is not the real reason. Already in 1969 the first larger exhibition of the Bechers is called “Anonymous Sculptures”, just like their first volume of photographs. The artists very consciously link the genres of photography and sculpture. This idea informs their entire oeuvre.

Bernd Becher and Hilla Wobeser begin to collaborate in 1959. At the time both study at the art academy Düsseldorf. Two years later they marry. During the following five decades the artist couple produces mostly tableaus of several parts – consisting of three, nine, twelve or more photos; they call them typologies. Their subjects are disused headstocks, furnaces, oil refineries, water reservoir towers, grain silos, gasometres or even half-timbered houses in former workers’ settlements – all of them testimonies of a declining industrial culture.

An Overall Concept

When Hilla and Bernd Becher presented their works at the Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in 1969, this coincided with an exhibition on US-American minimal art – a juxtaposition that was to prove programmatic. In 1972 the American sculptor Carl Andre mentioned the insightful connection of the Bechers’ works and the movements of minimal and conceptual art. This prominent, art-theoretical connection significantly contributed to the great international success of the Bechers. This is also why – especially in the USA – the two are considered concept artists more than photographers.

The Bechers’ method of working – ostensibly – is concerned with sobriety and anonymity, rigidity and objectivity. They work in series, where the whole and a part of this whole, total view and detail are balanced. Setting their photographs into the context of sculpture, they test the boundaries of the genres of photography and sculpture. Working and presenting their works in series, they move the photograph beyond the individual work: the viewer can never see everything at once; instead the eye oscillates between detail and general context.

The artist couple directs the attention to formal, creative aspects of the photographed edifices at the same time allowing them to disappear in the typology’s grid. The rigidity of their pictorial vocabulary and the interest in an industrial aesthetic evidences the close proximity of the Bechers’ creative work to minimal and concept art.

Photography in Germany

“In principle it [photography] was a fallow field, where nothing ‘noteworthy’ had taken place in the past fifty years. We saw us in the tradition of objective photography of the 1920s; Bernd and Hilla Becher were the first to reconnect to this. There was absolutely nothing that we could fight or needed to disengage with. We could start from scratch.” ~ Thomas Ruff

“New Objectivity” this was the motto of the 1920s – also in photography. It was no longer the pictorial language of painting, but precision, focus and truth to detail, characteristics of photography that had garnered the artists’ interest.

The photographer August Sander focused on the society of the Weimar Republic and created a typology: in 1925 his pictorial atlas People of the 20th Century, where he systematically assembled hundreds of portraits of stereotypes of people of the most diverse social backgrounds and occupations. All of his sitters are portrayed frontally, which makes the photographs comparable. Sander also engaged in the photography of landscapes, industrial sites and cities.

Two more representatives of the photography of New Objectivity are also worth mentioning here: Albert Renger-Patzsch recorded industrial buildings and machinery in a sober directness. Karl Blossfeldt adopted scientific standards and photographed plants – always before a neutral background, removed from their natural setting.

Bernd and Hilla Becher draw on these approaches and develop them in their works. With a few exemptions, photography was not considered an autonomous artistic medium in Germany. Still in the 1960s, photography in art predominantly served as a means of documentation of actions, happenings and performances. Yet painting and photography interact. The painter Gerhard Richter for example, used photos as templates for his paintings since the early 1960s. The Bechers in turn greatly contributed to the recognition of photography as autonomous artistic medium with their photographs.

The Becher Class: Adoption, Distinction

DÖHNE GURSKY HÖFER HÜTTE RONKHOLZ RUFF SASSE STRUTH WUNDERLICH

These are the students of the first Becher class. In 1976 Bernd Becher is appointed first professor for photography at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. In close cooperation with his wife Hilla he teaches there for twenty years. Their first students become artists, who will have a formative influence on photography in the 1980s and the 1990s internationally. The Becher students intensely study their teachers’ work. Especially in their early works comparable approaches develop: a distanced perspective, an interest in architecture and striving for technical precision.

The Bechers are preoccupied with an industrial architecture in decline, representative also of the social changes affecting the respective region. Taking this as a starting point, their students consider their direct surroundings and social contexts. They seek to identify systems of classification and in their photographs investigate the relationship of individual work and series. In the process the Becher students adopt their own positions. They discover new themes, techniques and creative strategies. Regardless of the distinctions they are indebted to the conceptual approach of their teachers, which they then developed in their individual ways.

In their teaching and their work Bernd and Hilla Becher explore a concept of the image, where medial and aesthetic distinctions of sculpture, painting and photography dissolve. Their students continue this work in very different ways. In the 1980s and 1990s their enquiries lead to a critical reflexion of the possibilities of representing reality. The lack of focus in the depiction of reality – literally and figuratively – represent an increase in artistic complexity. Innovative pictorial creations were now possible by way of digital intervention.

The borders of the photographic image blur at the stage between single work and typology and series. The alternation of perception, oscillating between detail and total image extend the possibilities of photography. The meaning of what is called “Becher school” can be summarised in a simple and surprising statement: at the historic moment, when photography becomes an independent medium, it also realises its potential and explores its limits. Photography reaches its limits, transgresses it and thus ultimately questions its existence.

Kiosks and Streets

The developments in American photography are also important to the Becher-students: Ed Ruscha, whose photos show everyday subjects, is one of their role models. In 1966 he creates Every Building on the Sunset Strip. With a simple handheld camera Ruscha photographs every building on the Los Angeles boulevard of that name; he presents his pictures in a fanfold or an artist’s book. This quickly reveals the serial principle behind the work. Volker Döhne’s approach in Reconstruction II is similar. He, too, documents the commercial architecture, largely determining the surrounding.

Ice cream parlour, garage, drug store, stationers, dwelling house, shoe shop – nicely aligned. Volker Döhne focuses on the urban space dominated by nondescript post war architecture and empty sites. Other than his American colleague Ed Ruscha, Döhne always positions his camera head-on in the same angle. Surprisingly this emphasises the buildings’ volume. Like his teachers Bernd and Hilla Becher he emphasises the three-dimensional, sculptural aspect of buildings and pursues a concept that he determined before he began to photograph.

The Bechers assemble identical, yet different photographs to a static tableau. Döhne on the other hand, required the viewer to move along the strip and proceed down the row of photographs. Above all the viewer must add together the photos of the Krefelder Straße by himself: the work forms as a result of the viewer’s active viewing and perception.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Krefeld, Ostwall corner Rheinstraße, (Reconstruction II)

1990 (1992)

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

47 × 37cm

Private collection

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Krefeld, Rheinstraße 82 (Reconstruction II)

1990 (1992)

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

47 × 37cm

Private collection

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Krefeld, Rheinstraße 84 (Reconstruction II)

1990 (1992)

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

47 × 37cm

Private collection

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Krefeld, Rheinstraße 86 (Reconstruction II)

1990 (1992)

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

47 × 37cm

Private collection

Volker Döhne (German, b. 1953)

Krefeld, Rheinstraße 88 (Reconstruction II)

1990 (1992)

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

47 × 37cm

Private collection

Tata Ronkholz (German, 1940-1997)

Beverage kiosk, Düsseldorf, Hermannstraße 31

1978

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

41.2 x 51.2cm

Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Köln/Dauerleihgabe der Sparkasse KölnBonn

© Tata Ronkholz, Nachlassverwaltung Van Ham Art Estate 2017

Cigarette and gumball machines are fixed to exterior walls. Advertising posters overlap. Beverages, magazines and sweets are visibly lined up behind glass. It is Tata Ronkholz’ serial presentation that enables the comparison of the kiosks and their study as a social phenomenon in urban contexts.

Kiosks are everyday meeting points and the setting for social life. At the same time their role fundamentally changed in the past decades. Ronkholz photographs kiosks as socially grown places. She positions them centrally in their architectural environment – people are absent. This is what the photos have in common with Becher-photographs. Like her teachers, Ronkholz is committed to the conservation and archiving of a changing urban culture.

Tata Ronkholz (German, 1940-1997)

Dusseldorf, Sankt-Franziskusstraße 107

1977

Silver gelatin print on baryta paper

41.2 × 51.2cm

Courtesy The Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne / Permanent Loan of the Sparkasse KölnBonn

Tata Ronkholz (German, 1940-1997)

Without title

1978

Silver gelatin print on baryta paper

41.2 × 51.2cm

Courtesy The Photographische Sammlung / SK Foundation Culture, Cologne / Dauerleihgabe der Sparkasse KölnBonn

Tata Ronkholz (German, 1940-1997)

Düsseldorf, Germany, Konkordiastraße 85

1978

Silver gelatin print on baryta paper

41.2 × 51.2cm

Courtesy The Photographische Sammlung / SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne / Permanent Loan of the Sparkasse KölnBonn

Picture Parallels

Bernd and Hilla Bechers students are linked to the work of their teachers in many ways. And yet they devote themselves, in part, to new motifs, subjects, and picture formats during their studies. In addition to architecture, they also photograph interiors, simple everyday objects or people.

In the early 1980s the Becher-students Axel Hütte and Thomas Ruff turn to portrait photography practically at the same time. They capture their models with neutral facial expressions, generally head-on before a monochrome background. The extreme setting makes the individual recede while the surface of the background dominates. In the series the single faces turn into an interchangeable motif somewhere between person and typology.

From Near and Far

The directions of the persons’ gazes differs. Nothing distracts from their faces. The neutral background and the close details are reminiscent of giant passport photographs. One almost overlooks that some of the sitters are famous artists today.

Axel Hütte’s portraits with their conscious play with blurring and sharpness are irritating: some areas in the photo show up the slightest detail, while others are slightly blurred – a conscious reference to the Bechers’ works, characterised by their extreme depth of focus. When observing Hütte’s works from close-up the face becomes a surface of structures. If one wants to see it in focus, one needs to distance oneself. Thus the viewer is kept at bay and always in motion.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

15 artists USA (David McDermott, Stephen Prina, Mike Kelley, Peter McGough, David McDermott, Doug Starn, Mike Starn, Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Ross Bleckner)

1988 (2003)

Silver gelatin print on baryta paper

113 x 91cm each

Loan from the artist

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

15 artists USA (David McDermott, Stephen Prina, Mike Kelley, Peter McGough, David McDermott, Doug Starn, Mike Starn, Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Ross Bleckner) (detail)

1988 (2003)

Silver gelatin print on baryta paper

113 x 91cm each

Loan from the artist

Pictures Generation

Thomas Ruff explores the gap between reality and image. This is something he shares with the American artists of the so-called “Pictures Generation” from the 1970s and 1980s. This informal group of artists, among them Cindy Sherman, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo and Richard Prince, grew up with a flood of pictures in cinema, television and the print media. Their works show distrust for the media, as well as a fascination with it. The artists make use of existing images from film, advertising and art. They copy, quote and redesign this material – more subtly than the artists from American Pop Art in the 1960s. Instead of working with found images in print, collage or painting, the artists of the “Pictures Generation” make small interventions. By introducing minor changes or by producing a practically identical copy of an image they very consciously play with conventional ways of perception. In their works they draw attention to mechanisms of picture production and the methods of artificial construction of reality through pictures.

Photos of Faces

Like Axel Hütte, Thomas Ruff does not believe in an image of human character. He is convinced that only the exterior reality – the appearance – can be represented. In this sense Ruff’s portraits are photos of faces that resemble expressionless surfaces. The monochrome background hides any hint at a recognisable location.

The face becomes a surface and thus resembles a projection screen for an advertising message. The serial juxtaposition turns the individual in Ruff’s photographs into a type that also represents a particular generation. The stereotypes communicated by mass media and the influence of images on individual and collective opinion-forming are being questioned.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Portrait (G. Benzenberg)

1985

Chromogenic colour print

41 × 33cm

Loan from the artist

“Looks good. Continue in colour.”

The bed, bath and living rooms, the kitchen unit and the furniture of the 1950s and 1970s, Thomas Ruff finds at the homes of relatives and friends in the Black Forest, where he comes from. Bernd and Hilla Becher preferably work in black and white. Ruff on the other hand starts experimenting with colour photography early on during his studies:

“At some point I started, making use of the colour practice, which I […] had developed, in my interiors, and I thought this looked better than in black and white photos. The colleagues said, you cannot do this. Then I also asked Bernd Becher and he said: “Looks good. Continue in colour.”

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

Interior 3 A

1979

Chromogenic paint removal

45.7 x 39.4cm

Loan from the artist

A Question of Mise-en-Scène

The two clips on yellow ground look like two flies. The bright background emphasises the form of the represented objects. Their original function becomes secondary. The simple stationary objects become worthy of the photographer’s meticulous attention. Jörg Sasse uses and parodies the strategies of advertising photography, ever concerned with presenting an object as something special.

From the start, Sasse’s work shows a painterly tendency as well as a penchant for abstraction. This is also apparent in a sequence of still lives with reduced colour and shapes. In his early work Sasse is interested in his immediate environment. He seeks to capture the unusual in the everyday. This links his work with the typologies of his teachers. Other than they do, Sasse does not give titles to his works; instead he gives them random numbers. This allows him to remove the represented object even further from its original context without offering a new interpretation.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Jörg Sasse (German, b. 1962)

ST-84-12-06

1984

Chromogenic paint removal

18 × 24cm

Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

Kitchen, Bath Room and Living Room

Almost in symmetry Jörg Sasse’s photo shows a light blue jug and a glass jug on two hobs. It belongs to a series, which Sasse dedicated to modest interiors between the post war years and the economic miracle. Sometimes the photos show individual objects, sometimes a combination of two or three objects. They capture details of tiles, furniture or floors.

They give the impression as if the objects were arranged by coincident or as if the inhabitants had left them behind like this. At the same time the scenes appear to be very artificial. Sasse transforms colour, shape and structure of the interior settings into individual, abstract compositions. He focuses on formal contrasts, sequences and similarities. According to the artist it is “not the preoccupation with interiors but with the picture.” The photographer is more interested in the painterly composition than in the representation of reality.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Jörg Sasse (German, b. 1962)

W-84-02-13, Dusseldorf

1984

Chromogenic paint removal

57.2 × 67.6cm

Courtesy Gallery Wilma Tolksdorf

Courtyards and Street Canyons

The artists Axel Hütte and Thomas Struth share an interest in urban non-spaces, indistinct streets or architectures.

In the 1980s modernist residential dwellings like the brutalist, square James Hammett House in London, become increasingly less popular and are turned into social housing. The raw concrete façade of the London block of flats spreads across almost the entire picture. The empty square in front of it is abandoned. There is no sign of inhabitants: a forbidding place.

Like Bernd and Hilla Becher in their pictures of industrial buildings, Axel Hütte emphasises the angular and unwieldy shapes of the architecture in his London series. From a distance the sad, functional façade appears to be an abstract pattern of rhythmically changing shades of grey, behind which the architecture recedes.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

James Hammett House

1982-1984

Silver gelatin print on baryte paper

66 x 80cm

Loan of the artist

In the Street

The row of houses on New York’s 21st Street seems never ending. Old houses and modern high rises alternate and form a sequence of textures and geometric forms rich in contrast. Thomas Struth was struck by the deep street canyons of the metropolis. He took his photos from the middle of the street, positioning the camera at eye-level – a method that resembles that of his teachers. It is an unusual perspective unfamiliar to both pedestrians and drivers.

Struth begins capturing urban spaces already when in Cologne and Düsseldorf. A stipend takes him to New York in 1978. His photographic approach offers a completely new view of the city’s urbanity and structure.

“I may very well stem from the legacy of documentary photography and do use its means and perspective, but my true concern exceeds this. […] To me the street is a space, where manifold influences and historical events convene and become apparent. The public space has a subconscious language, addressing us continuously.”

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

West 21st Street, Chelsea, New York

1978 (1987)

Gelatine silver print on baryta paper

66 x 84cm

DZ BANK art collection at the Städel Museum

© Thomas Struth

Variety

Landscapes, families, places of leisure, libraries, museums – the subjects of the Becher-students are equally as varied as their approach to photography. Their own positions develop more and more, while shared characteristics with their teachers’ oeuvre become apparent.

“Not the subject, but the representation of a landscape is what matters to me.” ~ Axel Hütte

Almost two thirds of the picture are concealed by thick fog. The rocks in the foreground, however, are razor sharp. In Furka Axel Hütte plays with the contrast of diffusion and focussed parts of the picture. He explores landscape photography and thus consciously enters into competition with the genre of painting.

Foggy landscape is of great importance in the paintings of German Romanticism. This art movement, which began in the late 19th century, is characterised by mystic nature, where religious ideas are intertwined with subjective sentiment. Caspar David Friedrich is recognised as one of the most important representatives of Romanticist landscape painting. To him nature mirrored the human soul. In his painting Mountains in the Rising Fog, which he painted around 1835, the hills are veiled and only the outlines can be made out. In his photographs, Hütte refers to this tradition and employs similar techniques to guide the viewer’s gaze and to compose the picture. The landscape can be sensually grasped. The atmosphere and the subjective experience come to the fore. While his teachers sought the proximity to sculpture, Hütte’s work reflects the strategies of painting.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Axel Hütte (German, b. 1951)

Furka

1994 (2012)

Chromogenic colour print

56.7 × 65.7cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung

The Silence Beside the Storm

Andreas Gursky’s works are dedicated to traffic hubs, mass events, economic centres, transit zones or places of leisure. Gursky’s focus is always on the common denominator and questions the relationship of man with nature and society. The photograph Teneriffa, Swimming Pool shows a holiday resort from a bird’s eye perspective that makes the tiny holidaymakers almost disappear. The force of nature represented by the foaming sea is in stark contrast with the artificial silence of the adjacent pool.

Like his teachers, Gursky keeps a distance to his subject. But unlike them he does not work in series and concentrates on single works. Bernd and Hilla Becher’s compositions are always about one centrally positioned object. Gursky’s images on the other hand are rich in detail and the motives are spread across the picture plane in captivating sharpness – he plays with visual challenge.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

Teneriffa, Swimming Pool

1987

Chromogenic colour print

104.5 × 127cm

On loan from the artist / Courtesy Sprüth Magers

Own Vantage Points

Candida Höfer too, photographs public spaces. Her photographs follow the architecture of the buildings she finds. At the same time she chooses unusual positions for her camera and thus resists the symmetries or views prescribed by the spaces. Her photos defy architectural hierarchies and structures and thus communicate the spatial experience in a particular way.

Waiting Room Cologne III 1981 is an early example of Höfer’s artistic method. The furniture reaches diagonally into the space, a dynamic underscored by the pattern of the parquet flooring. The row of tables and chairs in the bottom corner is cut off by the edge. Instead of creating a balanced symmetrical composition, she works with alternative vantage points.

This allows Höfer to emphasise her personal view of the interior architecture. Concurrently she is enquiring how the architectural space is influenced by the way people use it in the course of time. The Waiting Room with Neo-Baroque décor dating from the second half of the 19th century forms a stark contrast to the simple furniture that is easily 100 years less old.

“By means of the print I then create my own space once again. It is not my intention to show the space in a manner as realistic as possible.”

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Waiting Room Cologne III 1981

1981

Chromogenic colour print

155 × 155cm

Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

Libraries as Brand

Above all Candida Höfer is famous for her large-scale interior views of libraries devoid of people. The workspaces in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris are lined up like books in libraries. The artist frequently focuses on places that preserve and order knowledge and culture. Apart from libraries she also worked on museums or operas. She is interested in how humans influence architecture through their culture. Her photos are always determined by a cool sobriety. This is what they have in common with the photographs of the Bechers. However, Höfer always works with the light and the space present in each situation. She strives to capture the atmosphere and aura of a space.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Candida Höfer (German, b. 1944)

Bibliothèque Nationale de France Paris XIII 1998

1998

Chromogenic colour print

155 × 215cm

Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

The Picture in the Picture

In his series Museum Photographs Thomas Struth focuses on imposing interior spaces such as the gallery at the Louvre in Paris – unlike Höfer, he always shows the visitors, too. They become a multifaceted continuation of the figures in the paintings on the wall. Through the photograph Struth establishes a connection of pictorial space and real space, the painterly and photographic space. Here, the formerly competing media painting and photography enter into a dialogue as equals.

Simultaneously the viewer is confronted with different levels of viewing: those who contemplate Struth’s photos inevitably also observe the visitors at the Louvre contemplating the art works there. Thus the artist prompts a reflection on how we deal with art and its history, with seeing and being seen. Struth does not influence the positions of the visitors in his Museum Photographs. He waits for situations that can serve as the basis of his compositions. Struth merely decides on the space and the visual angle he takes.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

Louvre 3, Paris 1989

1989 (2012)

Chromogenic colour print

152.2 × 168.3cm

DZ BANK Kunstsammlung im Städel Museum, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

Family Relations

The photo The Consolandi Family, Milano by Thomas Struth belongs to the series Family Portraits, which shows relationships that are complex and full of tension. The viewer is challenged to explore the connections of the family, reflected in subtle looks, mimics or posture.

The Family Portraits evolved from an unpublished project, which Struth and a friend of his, a psychoanalyst, pursued in the early 1980s. Patients were asked to submit a couple of photographs that were typical of their families, which Struth then combined in a portfolio. Drawing on this project, the photographer began to work with family portraits he took. He photographed people he knew in their homes. The individuals were asked to choose their position in a space that the artist had selected. Struth’s psychological interest in the family as a social fabric is evident. The order resembles a sociagram after all.

Like the Bechers’ works, Struth’s photographs are determined by an intrinsic dynamic full of tension. While his teachers work with industrial fields of force, he balances psychological energies. This results in an alternation of perception – the eye sways between single pictorial elements and the total composition.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Thomas Struth (German, b. 1954)

The Consolandi Family, Milan 1996

1996 (2014)

Chromogenic colour print

178 × 214.2cm

Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation

Picture Editing

In February 1982 the first great scandal about a digitally edited press picture occurs: for the title of the periodical National Geographic – actually indebted to scientific exactitude – the pyramids at Gizeh have been pushed closer together so they would fit the portrait format. This represents a fundamental shift in photo and media culture that also affects the work of the Becher students.

Ruff, Sasse and Gursky especially, develop their works digitally. This inevitably distances them from their teachers’ documentary approach more and more. The artists do not depict reality they create their own reality. This results in photographs that cannot be explained through analogue camera technology. The truth in the pictures is questioned, just like the viewer’s perception. In nascent form this approach is already present in the typologies created by the Bechers.

Digital interventions

This photo of an average residential block from 1987 marks a turning point in Thomas Ruff’s oeuvre. Things – namely a tree and a street sign – are missing. Ruff decided to have these details erased. He also retouched an opened skylight. This is one of the first digitally edited pictures in the circle of the Becher students. Ruff’s idea is to emphasise the symmetrical appearance and the hermetic quality of the building. Still, he is not really meddling with the picture’s structure of reality.

Ruff’s photos of the House Series confront the viewer with urban banality. The enormous scale of the works, measuring nearly 2 x 3 metres exaggerates the uneventfulness as a crucial characteristic of this architecture. From the 1980s the Becher students increasingly use large formats. They become a trademark of the group. Mostly presented with a wooden frame the artists elevate the photos to the level of paintings. Like the Bechers, Ruff worked in series, but no longer arranged his works in typologies. His series preserve the suspicion of a single image that might represent the world.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Thomas Ruff (German, b. 1958)

House No. 1

1987

Chromogenic colour print

179 × 278cm

Loan from the artist

Giant Grid

In photos like Paris, Montparnasse Andreas Gursky enlarges the image to a monumental scale of over four metres in width. He, too, relies on digital editing. The frontal view of the residential block is presented in strictly right-angular lines. The building is so wide that it would be impossible to capture it in a single photo. Hence, Gursky used two photos and joined them on the computer.

From a distance, the geometrical grid of the building looks abstract. The skeleton structure of the block also means that the windows offer hundreds of single images. However, it is impossible to simultaneously perceive the detail as well as the overall structure. Gursky requires the viewer to constantly alternate his focus between close-up and distance.

“My pictures are always composed for two aspects […]. The smallest detail can be read from close up. From afar they are mega-signs.”

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Exhibition view “Photographs Become Pictures. The Becher Class” showing Andreas Gursky’s Paris, Montparnasse 1993 (before 2003)

Photo: Städel Museum

Andreas Gursky (German, b. 1955)

Paris, Montparnasse

1993 (before 2003)

Chromogenic colour print

207 × 422cm

On loan from the artist / Courtesy Sprüth Magers

Pixel and Pixel and Pixel

Sasse’s work 1546 (1993) also plays with perception at the border of abstraction. The single pixels as a trace of the digital reworking are immediately visible. The realistic representation of a curtain is ruptured. Instead pixel and square colour fields become the focus, while the original sense of space is lost. The photo appears two-dimensional.

Sasse takes up a basic issue with the illusion of space that has a long art historic tradition. Already in early Renaissance the artist and scholar Leon Battista Alberti considers painting as a window to the world. He considered it important for an illusionist way of painting to conceal the two-dimensionality of the canvas. In his oeuvre Sasses draws on this issue. He questions photography and painting’s claim to realism and questions the possibility of pictorially representing reality at all.

Anonymous text from the Becher Class at the Städel Museum website [Online] Cited 27/12/2021

Jörg Sasse (b. 1962) 1546, 1993 (centre) and Jörg Sasse (b. 1962) 7341, 1996 (right)

Jörg Sasse (German, b. 1962)

1546

1993

Chromogenic colour print

137 × 200cm

Private collection

Jörg Sasse (German, b. 1962)

7341

1996

Chromogenic colour print

93 x 150cm

DZ BANK art collection at the Städel Museum

© Jörg Sasse; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Städel Museum

Schaumainkai 63

60596 Frankfurt

Opening hours:

Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday – Sunday 10.00am – 6.00pm

Thursday 10.00am – 9.00pm

Monday closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.