Exhibition dates: 19th November 2016 – 5th February 2017

Curator: Julie Ewington

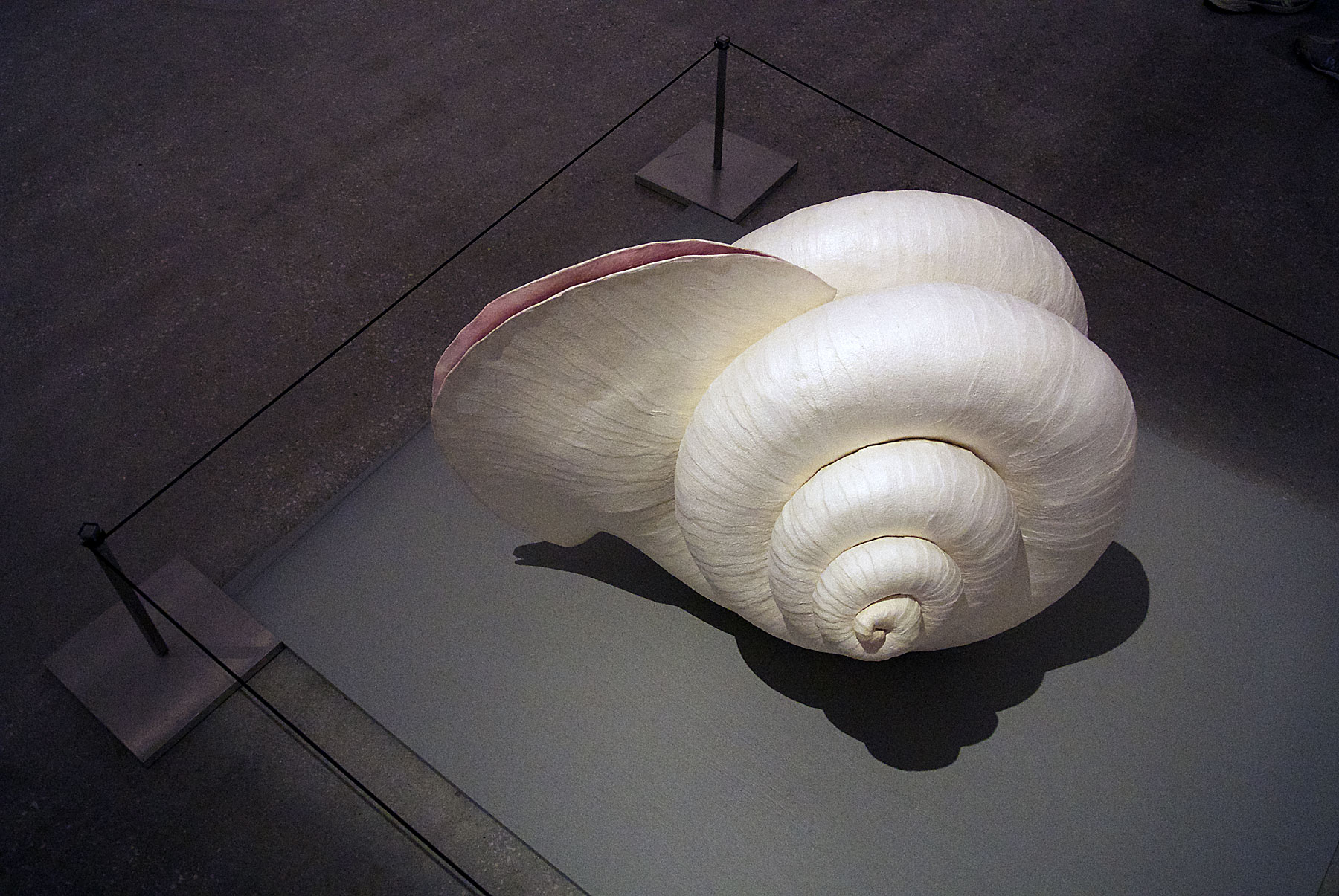

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Mantle

1985

Paper, fibreglass, dye

45.7 × 101.6 × 45.7cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

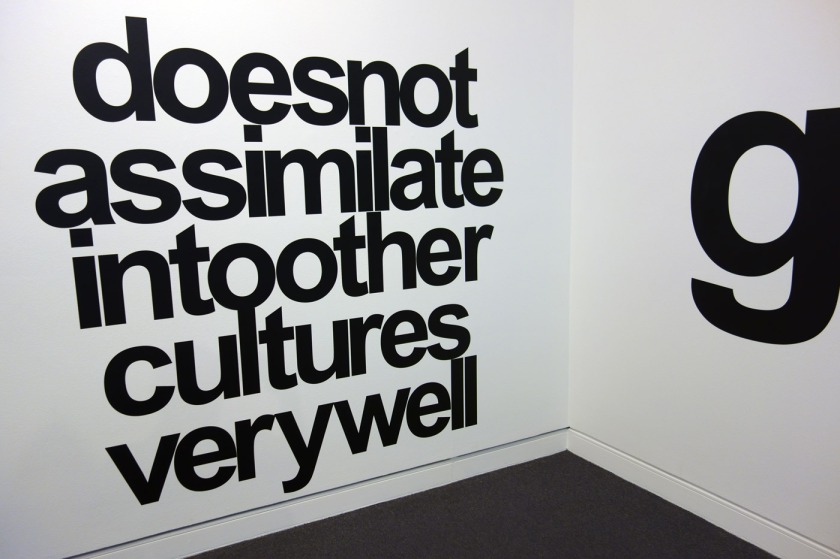

Reading either side of the sign

Bronwyn Oliver and the invitation to imagine

John Berger once said, “The Renaissance artist imitated nature. The Mannerist and Classic artist reconstructed examples from nature in order to transcend nature. The Cubist realised that his awareness of nature was part of nature.”

And the postmodernist?

The postmodern artist regarded nature as a series of multiplicities that were impossibly complex to define, so were at once irrelevant but also beyond any new mythologizing. Nature was the green screen background used to mask (and transform) lives into any new series of narratives.

Thinking about the sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver in this magnificent retrospective of her work, I was struck by the classical beauty of form, attention to detail and delicacy of their construction. I noted their monochromatic palette and the self contained nature of all the works (with one word titles such as Wrap, Husk, Flare and Siren), as though they could not exist outside of themselves. And yet they do.

I thought long and hard about how Oliver’s biomorphic sculptures transcend time and space, how intractable metal becomes mutable object, metal into cosmos, nature. How they become a “form” (in energy terms) of transmitted, transmuted reality. And how you access that energy through their punctum, the shadows that they cast on the wall. And I had this feeling, of a lump in the throat, of a most visceral experience which made me have a tear in my eye for most of the time I was walking around the gallery.

For Oliver has created a new mythology through her imagination and in her nature through a series of multiplicities which is anything but irrelevant.

These objects from another time have an ancient feeling, slipping and slithering through the mud of evolution, nursing their young in enclosed spirals, or waiting for prey – open mouthed like pitcher plants – waiting for prey to drop into their interior. There is a darker side to these sculptures that is usually unacknowledged. Order and chaos, a formal, sculptural logic and poetic logic, always go hand in hand. In both dark light (ying yang), the complexity and simplicity of everything presented here vibrates and hums with energy. I imagine much like the artist herself.

When work is inspired like this, the sculptures seem to attain another temporal dimension. They take the viewer out of themselves and into another world. How does the artist make this happen?

Oliver makes this happen through reading either side of the sign. While there are obvious references to shell, heart, calligraphy, text, wrap, cloak, cell, flower, comet, spiral, sphere, ring and more in her work, she never didactically forces these signs on the viewer. She invites them to reimagine, to see the world and its land / marks in unfamiliar ways by shaping, twisting, and reinterpreting the sign. Individually and collectively, the nexus of the work (the series of connections linking two or more things) creates, “A presence, energy in my objects that a human being can respond to on the level of soul or spirit.”

This is the strength and beauty and energy of her work.

While the works look absolutely stunning in TarraWarra Museum of Art galleries, not everything is sunshine and light. Some of the shadows cast on the wall were unfocussed and lacked definition, inhibiting access to the appearance and disappearance of form and the multiplying physicality of the works. Stronger and more focused lighting was needed in these instances. Perhaps another curatorial opportunity was lost in not bringing together the numerous forms of sculpture such as Eddy 1993 and Swathe 1997 in one grouping within the gallery. On their own the forms became slightly repetitious; together, as Oliver notes of her circular works being in a series, “They each have the same format, but very different energies. Different lives.” I would have liked to have had the opportunity to compare and feel those different energies in a group, side by side. These are minor quibbles, however, as this is one of the most memorable exhibitions I have seen in years.

I cannot recommend this exhibition highly enough: not to be missed!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the TarraWarra Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photograph for a larger version of the image. All images unless stated underneath © Dr Marcus Bunyan and TarraWarra Museum of Art.

“I am trying to create life. Not in the sense of beings, or animals, or plants, or machines, but ‘life’ in the sense of a kind of force. A presence, energy in my objects that a human being can respond to on the level of soul or spirit.”

Bronwyn Oliver, 1991

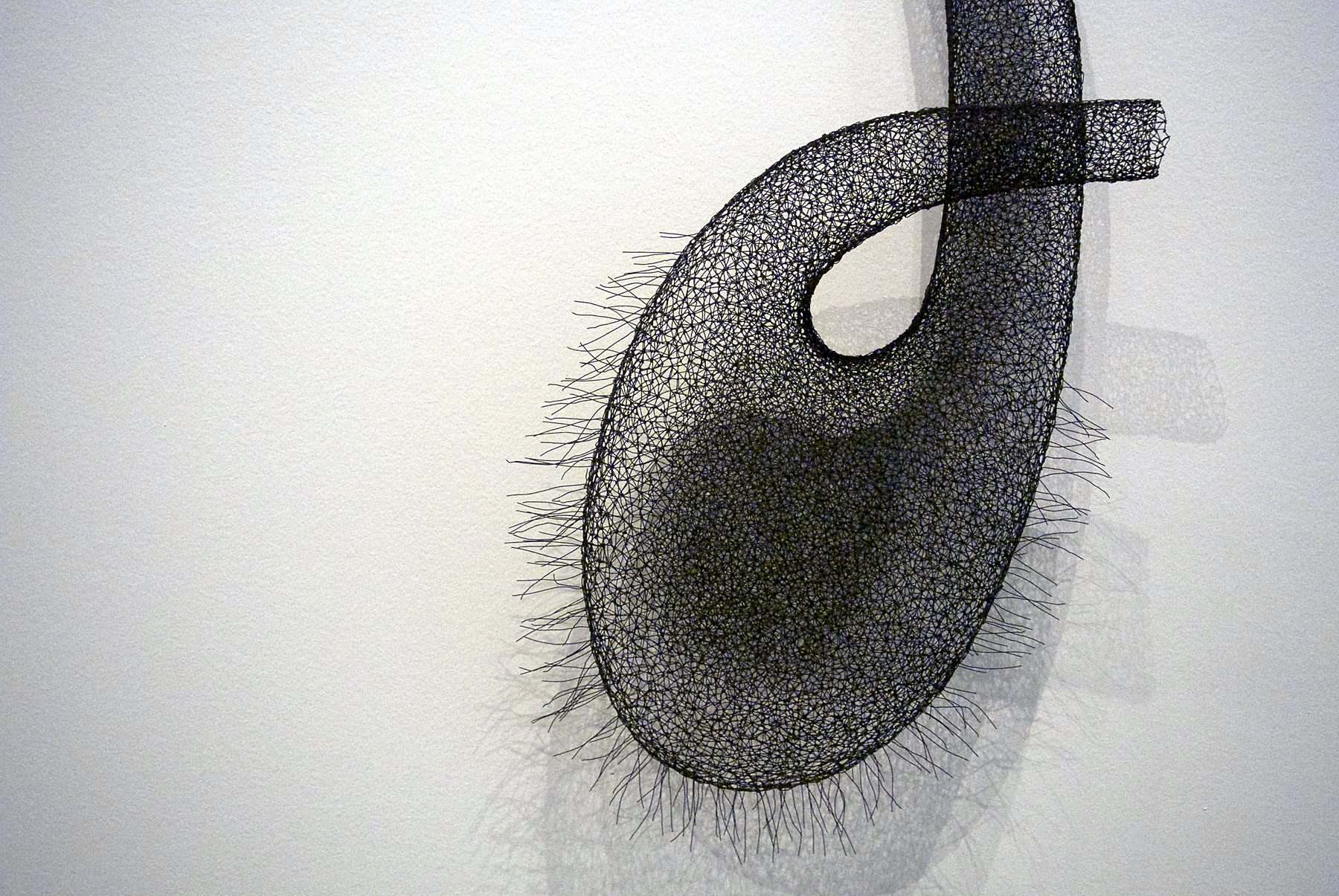

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Siren

1986

Paper, fibreglass, dye

71 × 91.5 × 76.2cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

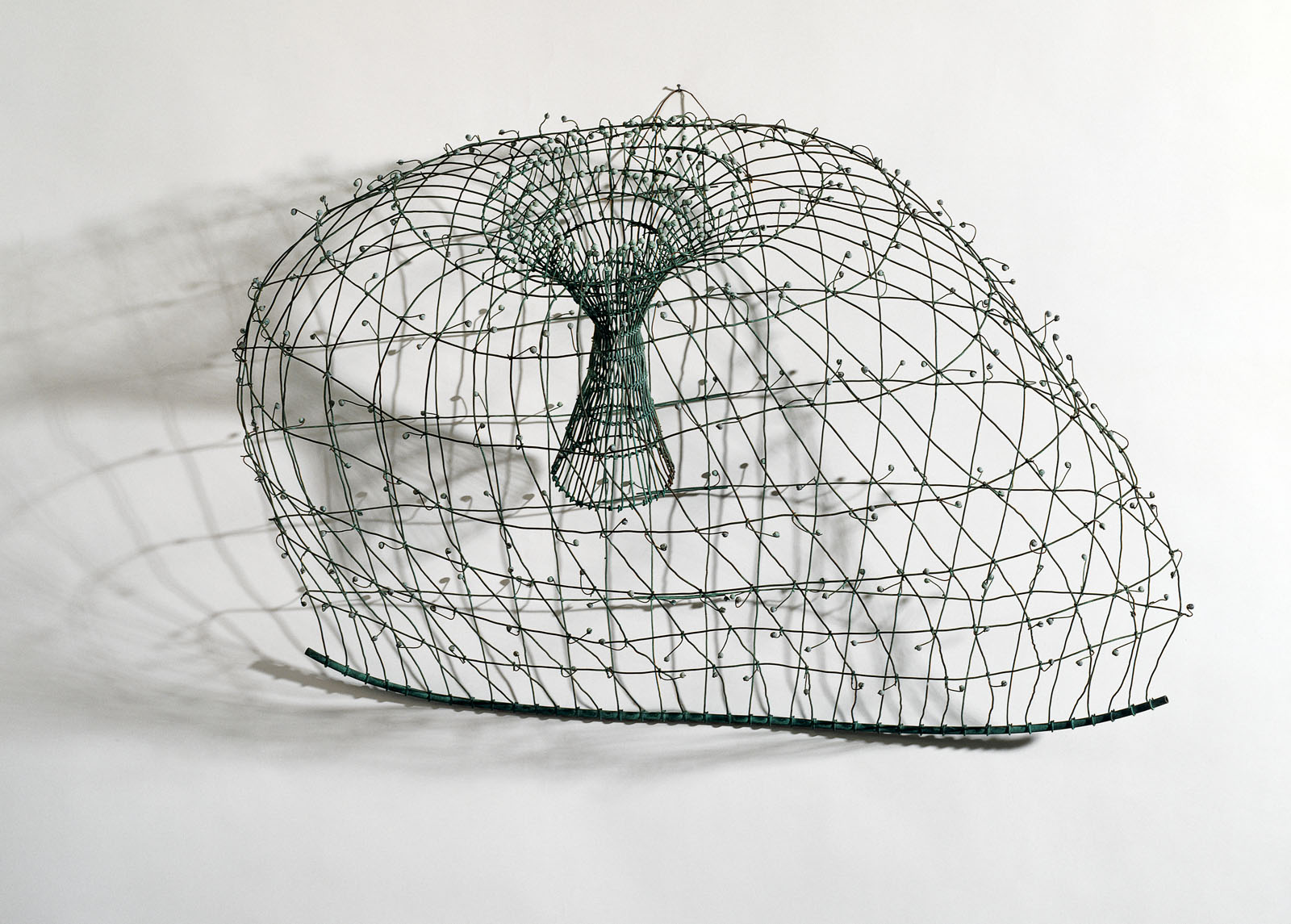

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Home of a Curling Bird

1988

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Apostrophe

1987

Copper and lead

100 × 100 × 60cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Andrew Curtis

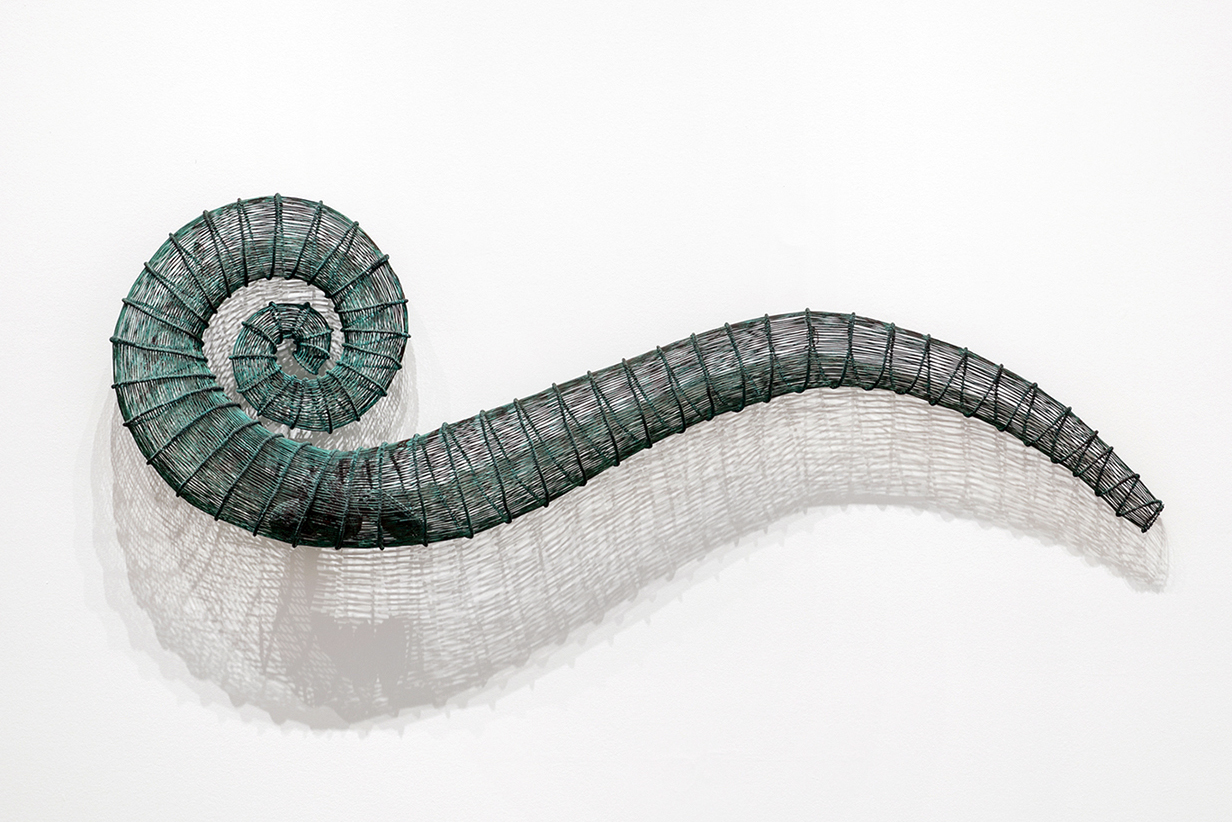

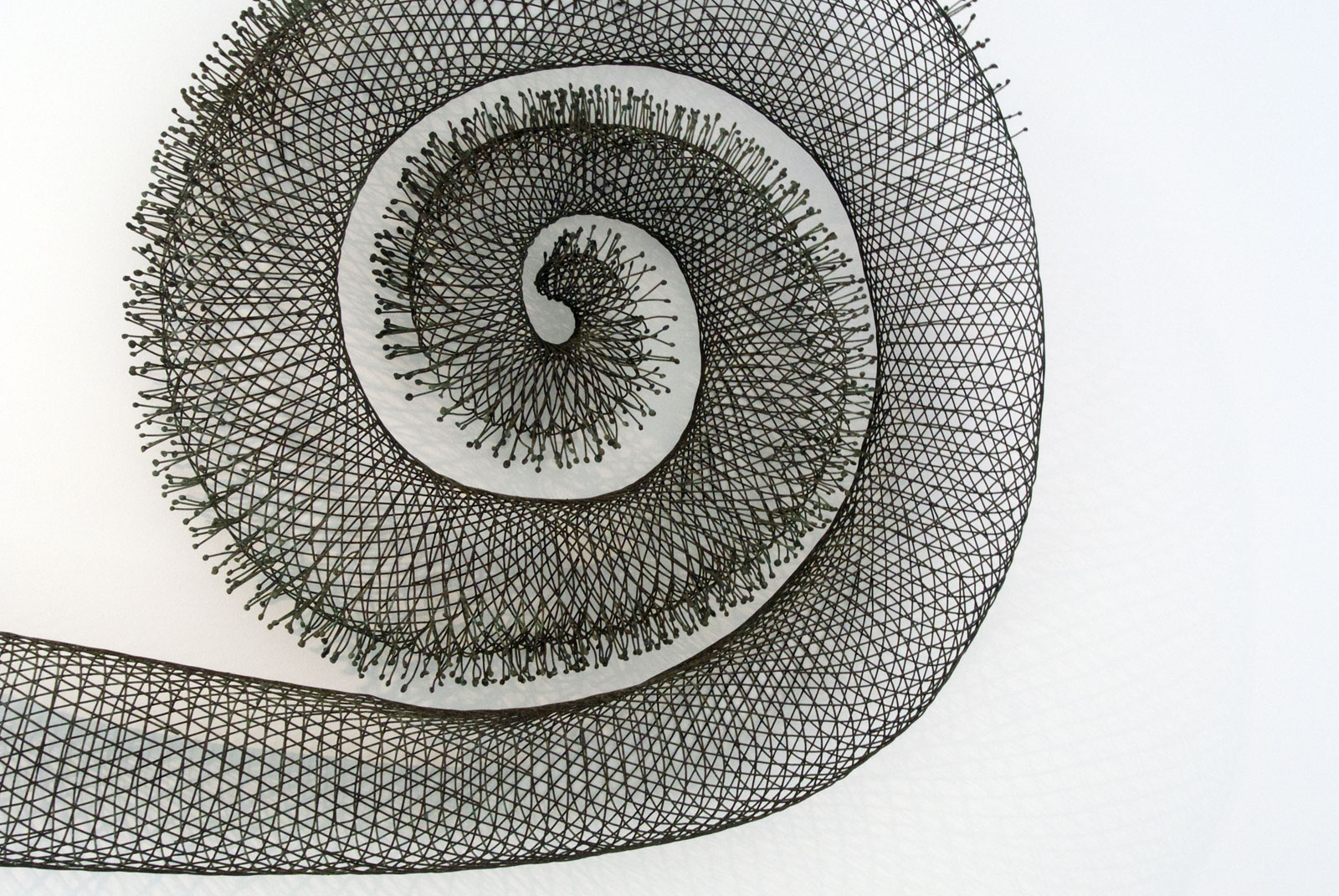

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Curlicue (detail)

1991

Copper wire

250 × 45 × 15cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Curlicue definition: A decorative curl or twist in calligraphy or in the design of an object.

Sonia Payes (Australian, b. 1956)

Bronwyn Oliver

2006

C-type photograph, edition of 10

127 x 127cm

Courtesy of the artist

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Ring II

1994

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

“I am quite please about the circular works being in a series. I have not worked through an idea like this before. I think they will look quite strong together. They each have the same format, but very different energies. Different lives.” ~ Bronwyn Oliver, 1994

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Wrap

1997

Copper

45 × 35 × 12cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Husk

1994

Copper

Collection of Vivienne Sharpe

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Flare

1997

Copper

50 × 50 × 14cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

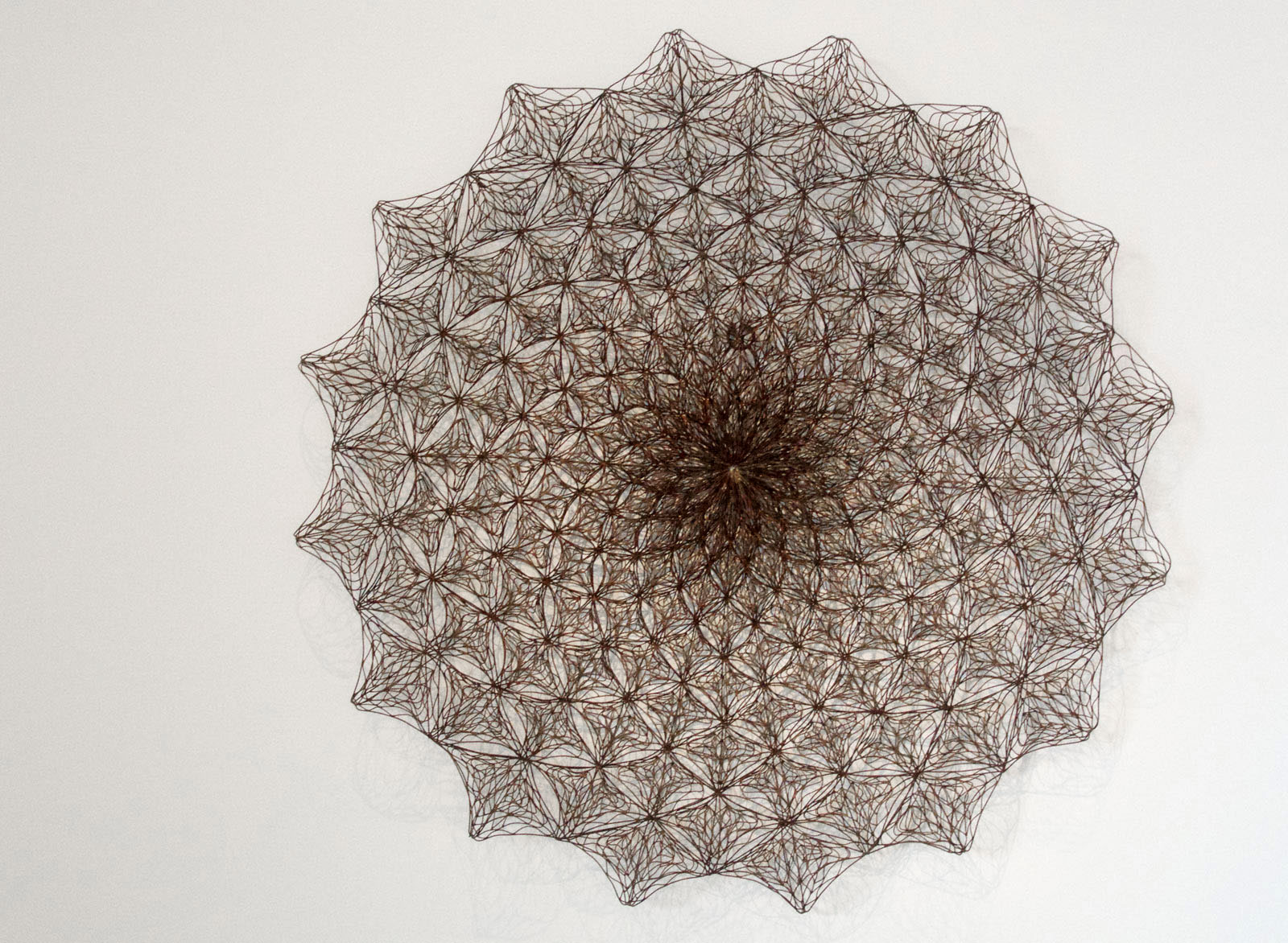

Bronwyn Oliver (1959-2006)

Iris

1989

Copper

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

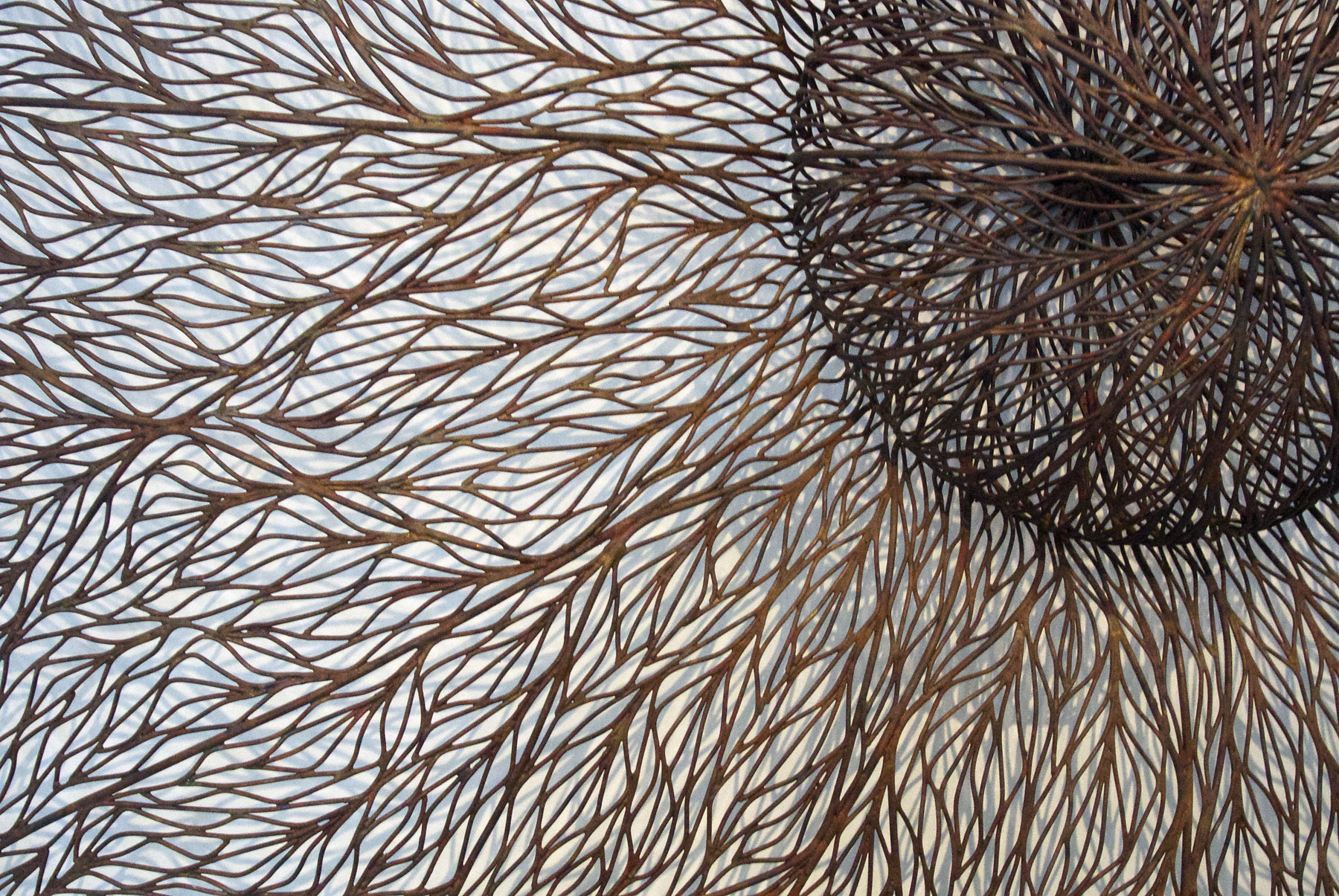

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Iris (detail)

1989

Copper

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Hatchery

1991

Copper, lead and wood

50 × 70 × 60cm

Artbank collection, purchased 1991

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Hatchery

1991

Copper, lead and wood

50 × 70 × 60cm

Artbank collection, purchased 1991

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Hatchery (1991) with Heart (1988) beyond

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Installation view (main gallery space), The Sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2016

L to R: Slip 1998, Anthozoa 2006, Unity 2001, Blossom 2004-05, Tress 1992

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Slip

1998

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Clef

1993

Copper

110 × 45 × 40 cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

“The ideas relate to the effect of the shadow as a drawing, and the appearance and disappearance of form.” ~ Bronwyn Oliver, 2006

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Clef (detail)

1993

Copper

110 × 45 × 40cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

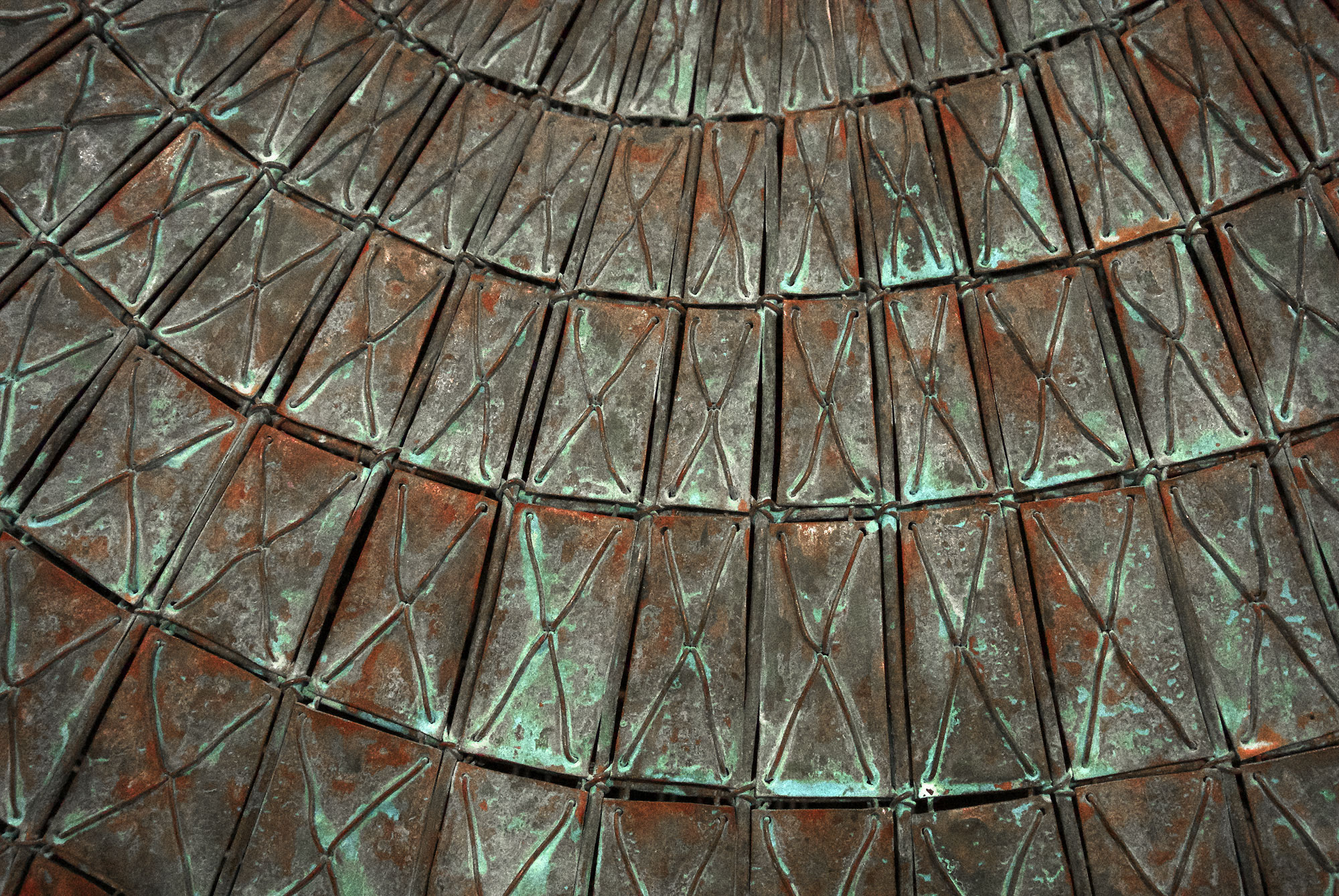

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Anthozoa (detail)

2006

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (1959-2006) was one of the most significant Australian sculptors of recent decades. This first comprehensive survey of 50 key works, from the mid-1980s to the final solo exhibition in 2006, includes early works made in paper, major sculptures from public collections, and maquettes for many of her much-loved public sculptures.

Emerging in the early 1980s when many artists were turning to installation, video and other ephemeral art forms, Oliver resolutely pursued making complex and substantial works in a variety of materials, eventually exclusively in metal. Studying in the UK and working in Europe, Oliver came to artistic maturity at the time of an international resurgence of sculpture; having attained a Masters degree at Chelsea School of Art in 1982-83, she witnessed the nascent years of the ‘New British Sculpture’.

This exhibition reveals Bronwyn Oliver’s lyrical sensibility and inventiveness. She developed an original, distinctive and enduring vocabulary that expressed her fascination with the inner life and language of form, and she tenaciously followed the beguiling demands of her chosen materials.

‘My work is about structure and order. It is a pursuit of a kind of logic: a formal, sculptural logic and poetic logic. It is a conceptual and physical process of building and taking away at the same time. I set out to strip the ideas and associations down to (physically and metaphorically) just the bones, exposing the life still held inside.’1

Oliver brought poetic brevity and decision to her sculpture. Many works suggest aspects of the natural world and its metaphorical potential, and a number of the public works are located in gardens. Yet works such as Home of a Curling Bird and Eddy evoke associations with shelter or natural movement or, as with Curlicue,conjure human mark-making with studied panache. Oliver’s work encompasses what appear to be archetypal forms, like shells, spirals, circles, and spheres; their delicate shapes trace shadows that become spectral drawings on the gallery wall, multiplying the physicality of the works.

Between 1986 and her death in 2006, Oliver presented 18 solo exhibitions and from 1983 participated in numerous group exhibitions in Australia and in Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany, New Zealand, Korea and China. At the same time, she undertook many commissions where she worked closely with clients and stakeholders, and for 19 years taught art to primary school students at Sydney’s Cranbrook School. Prodigiously hardworking, Oliver devised exquisite sculptures for the public domain, in locations as various as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Hilton Hotel and Quay Restaurant in inner-city Sydney, and at the University of New South Wales, as well as in Brisbane, Adelaide and Orange in regional NSW. Her work is held in most major Australian public collections, and in numerous collections in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Europe and the USA.

As writer Hannah Fink memorably observed in 2006, ‘Bronwyn Oliver had that rarest of all skills: she knew how to create beauty.’ This exhibition is a tribute to that power.

Text from the TarraWarra Museum of Art website

1/ Bronwyn Oliver quoted in Hannah Fink, ‘Strange things: on Bronwyn Oliver’, in Burnt Ground, (ed. Ivor Indyk), Heat 4. New series, Newcastle: Giramondo Publishing Co, 2002, pp. 177-187.

Installation view (main gallery space), The Sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2016

L to R: Eddy 1993, Shield 1995, Wand 1991, Blossom 2004-05, Lily 1995

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Eddy (detail)

1993

Copper

Art Gallery of South Australia

Gift of the Moët and Chandon Australian Art Foundation Fellow Collection 2000

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

“‘… the act of fabrication’ [is essential] … A couple of pairs of pliers, a wire-cutter, hand-drill, rivet gun and a Stanley knife is my usual kit. That’s what I’ll be taking to France. I’m compulsive. I’ll start work within 24 hours.” ~ Bronwyn Oliver, 1994

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Swathe

1997

Copper

180 × 300 × 300cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Swathe (detail)

1997

Copper

180 × 300 × 300cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Swathe (detail)

1997

Copper

180 × 300 × 300cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Sonia Payes (Australian, b. 1956)

Bronwyn Oliver

2006

Courtesy of the artist

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Shield

1995

Copper

McClelland Gallery + Sculpture Park collection

Purchased with funds from the Elisabeth Murdoch Sculpture Foundation, 1995

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

“All in this series have a ‘ruched’ copper surface in common, and the idea of a swelling / breathing form beneath the surface. (Idea began with a (dreadful) sculpture seen in the Musée d’Orsay in 1990-91. Sculpture of a gladiator, in bronze, wearing ‘ruched’ leggings, with musculature taut beneath the surface of the cloth). Final work completed in Hautvillers studio.” ~ Bronwyn Oliver, 2006

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Lily (detail)

1995

Copper

Newcastle Art Gallery collection

Gift of Ann Lewis AO 2011

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Installation view (farther gallery space), The Sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2016

L to R: Striation 2004, Grandiflora (Bud) 2005, Rose 2006, Grandiflora (Bloom) 2005

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Rose

2006

Copper

Collection © Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Rose (detail)

2006

Copper

Collection © Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Umbra

2003

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Umbra (detail)

2003

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Umbra (detail)

2003

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Lock

2002

Copper

125 x 125 x 14cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Lock (detail)

2002

Copper

125 x 125 x 14cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Sakura

2006

Copper

48 × 48 × 20cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Ammonite

2005

Copper

95 × 90 × 90cm

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Oliver developed an original, distinctive and enduring vocabulary that expressed her fascination with the inner life and language of form and the strict but beguiling demands of her chosen materials.

Above all, she brought an almost poetic brevity and decision to her sculpture. Many works suggest aspects of the natural world and its metaphorical potential, and some of the most successful public works are located in gardens. Yet Oliver always tenaciously followed the logic of her material, making works such as Eyrie or Eddy that evoke associations with shelter or natural movement or, as with Curlicue, conjure human mark-making with deliberate panache.

TarraWarra Director, Victoria Lynn, described the exhibition as a testament to the short but poignant contribution made by Oliver to Australian sculpture – a vision that remains exceptional in the history of Australian contemporary art.

“Oliver’s unique and labour-intensive approach involved joining threads of copper wire to create what appear to be woven forms that allow light to pass through their surface and cast shadows on the walls and floors. Her works resonate with the force of archetypes, and their green and brown patinas suggest an enduring presence that remains as relevant now as when they were first created. Some appear to be rescued from an archaeological past, while others resemble the quintessential forms found in nature: spirals, spheres, rings and loops,” Ms Lynn said.

Oliver was renowned for sensitive and inventive sculptures placed in the public domain, and she worked closely with clients, stakeholders and architects in their installation. This exhibition will include maquettes of some of Oliver’s much-loved public works, accompanied by working documents and images. Exhibition curator Julie Ewington said the exhibition, located within the museum building in TarraWarra’s magnificent grounds, will be the perfect setting for appreciating Oliver’s work.

Bronwyn Oliver (1959-2006)

Bronwyn Oliver was one of the outstanding Australian artists of her generation, and perhaps its leading sculptor. Originally working in cane and paper, by 1988 Oliver began working in metal, especially copper, and in the next two decades achieved a distinctive and enduring body of work. As writer Hannah Fink memorably observed in 2006, ‘Bronwyn Oliver had that rarest of all skills: she knew how to create beauty’.

Raised near Inverell in country New South Wales, in 1959, Bronwyn Oliver first studied sculpture in Sydney at Alexander Mackie College of Advanced Education from 1977-80. She said of her arrival at the College sculpture department, ‘I knew straight away I was in the right place’. After gaining the NSW Travelling Art Scholarship, Oliver completed a Masters’ degree in London at the Chelsea School of Arts in 1982-3. The recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, in 1988 Oliver was artist-in-residence in the French coastal city of Brest, where she studied Celtic metalworking; in 1994 she won the prestigious Moët & Chandon Award, which allowed her to spend a year living and working in France.

Oliver emerged in the 1980s at the same time as an international resurgence of contemporary sculpture. In response to the Conceptual and Minimal art of the prior decade, artists returned to the fabrication of sculptural form. Having attained a Masters of Sculpture at Chelsea School of Art in 1982-83, Oliver was witness to the nascent years of this celebration of form in British art, where it was known as ‘New British Sculpture’.

Between 1986, with her first solo show at Sydney’s Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, and her death in 2006, Oliver presented 19 solo exhibitions, including a number at Christine Abrahams Gallery, Melbourne; in 2005-6, McClelland Gallery, at Langwarrin in Victoria, presented a selected survey of her work; and from 1983 onwards Oliver participated in numerous group exhibitions in Australia and internationally, including in Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Germany, New Zealand, Korea and China (her final solo exhibition was posthumous). At the same time, she undertook many commissions where she worked closely with clients and stakeholders, and for 19 years taught art to primary school students at Sydney’s Cranbrook School.

Prodigiously hardworking, Oliver was renowned for devising exquisite sculptures for the public domain, installed in locations as various as the Royal Botanic Gardens, the Hilton Hotel and Quay Restaurant in inner-city Sydney, and on the Kensington campus of the University of New South Wales. Other noted public works are in the Queen Street Mall, Brisbane, Hyatt Hotel, Adelaide and Orange Regional Gallery in regional NSW. Her work is also held in most major Australian public collections, and in numerous important public and private collections in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Europe and the USA.

The Estate of Bronwyn Oliver is represented by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney.

Press release from the TarraWarra Museum of Art

Installation view (side gallery space), The Sculpture of Bronwyn Oliver, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2016

L Spiral IV 1993 and in case Women’s suffrage maquette 2002

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Spiral IV (detail)

2003

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Spiral IV (detail)

2003

Copper

Private collection

© Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Women’s Suffrage maquette (detail)

2002

Copper, nickel

Collection © Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

Bronwyn Oliver (Australian, 1959-2006)

Women’s Suffrage maquette (detail)

2002

Copper, nickel

Collection © Estate of Bronwyn Oliver. Courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: © TarraWarra Museum of Art and Dr Marcus Bunyan

TarraWarra Museum of Art

311 Healesville-Yarra Glen Road,

Healesville, Victoria, Australia

Melway reference: 277 B2

Phone: +61 (0)3 5957 3100

Opening hours:

Open daily 11am to 5pm

Open all public holidays except Christmas day

Summer Season – open 7 days

Open 7 days per week from Boxing Day to the Australia Day public holiday

You must be logged in to post a comment.