Exhibition dates: 14th June – 12th July 2014

Alan Constable creating one of the cameras for the Polaroid Project

Polaroid Project is a vaguely disappointing exhibition at Arts Project Australia. The intentions and concept are good but the work sits rather silently and uneasily in the gallery space.

Constable’s anthropomorphised cameras are as lumpy and charismatic as ever, but the black colour does them no favours. Instead of transporting the viewer they become rather heavy and dull. They loose most of their transformative appeal.

Atkins’ boxes, “readymade abstractions” – his first attempt at sculpture – needed to be pushed further. While his painting practice uses distinctive graphic, jazz and minimalist colour forms, what makes them so watchable and mesmerising is that the eye has to attempt to go beyond the two-dimensional plane, to interrogate the juxtaposition of shape and space. The MDF cubes hand painted with auto acrylic paint deny the eye the ability to probe beyond the surface because the surface is already three dimensional. These boxes, these gestures of appropriation (devoid of text) just become perfect simulacra and, in reality, they really don’t take you anywhere.

Here’s an idea (or two): as Constable has had to take the camera out of the boxes – interior becomes exterior – what about carving into the MDF boxes in a series of steps that move inwards – exterior becomes interior! The colours would then move away from you. Not in all of them, just a few. It would certainly add more life and movement to the ensemble. And then, for good measure, paint a couple of the walls in the colours of the boxes – the whole goddam wall. THEN, place the cameras and cubes against this neon pop surface and see what happens… WHAM! KAPOW! Now we have something to think about, not this side by side act of representation that is really rather awkward.

Just me rabbiting on with some ideas, but as I said at the beginning, the whole exhibition is too silent and deadly. The whole shebang needs a good jolt of electricity to get the juices flowing. After all these ARE pop colours and these ARE Polaroid cameras – which produced the most popular form of instantaneous photograph, and representation in a physical form, so far invented. Ah, that speed and velocity of transmission.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

.

Many thankx to Arts Project Australia for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. As noted installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan

Polaroid camera inspiration

Polaroid Project is an in-depth collaborative project between celebrated Melbourne based artists Alan Constable and Peter Atkins examines both artists shared interests in the reinterpretation of existing forms, offering the viewer an opportunity to experience the complimentary ways these diverse artists view their distinctive worlds. This significant exhibition sees both artists responding to a collection of twelve original Polaroid cameras and packaging manufactured in the 1960s and 1970s.

Alan Constable (Arts Project Australia, Melbourne)

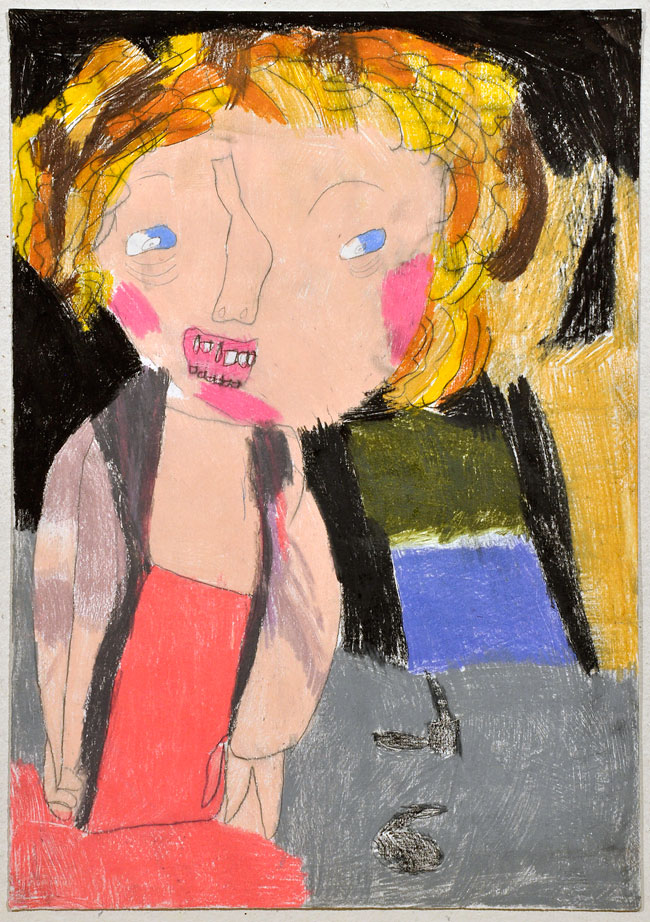

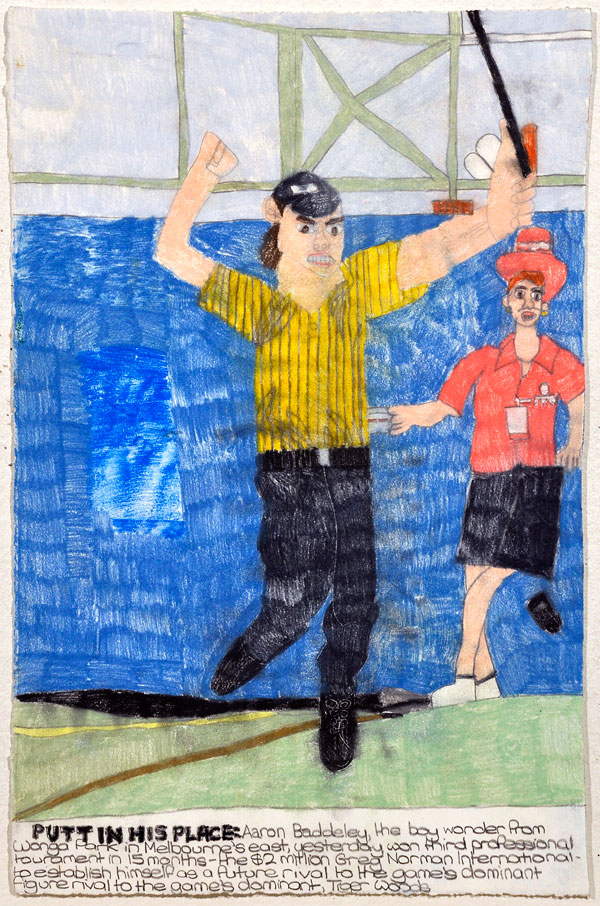

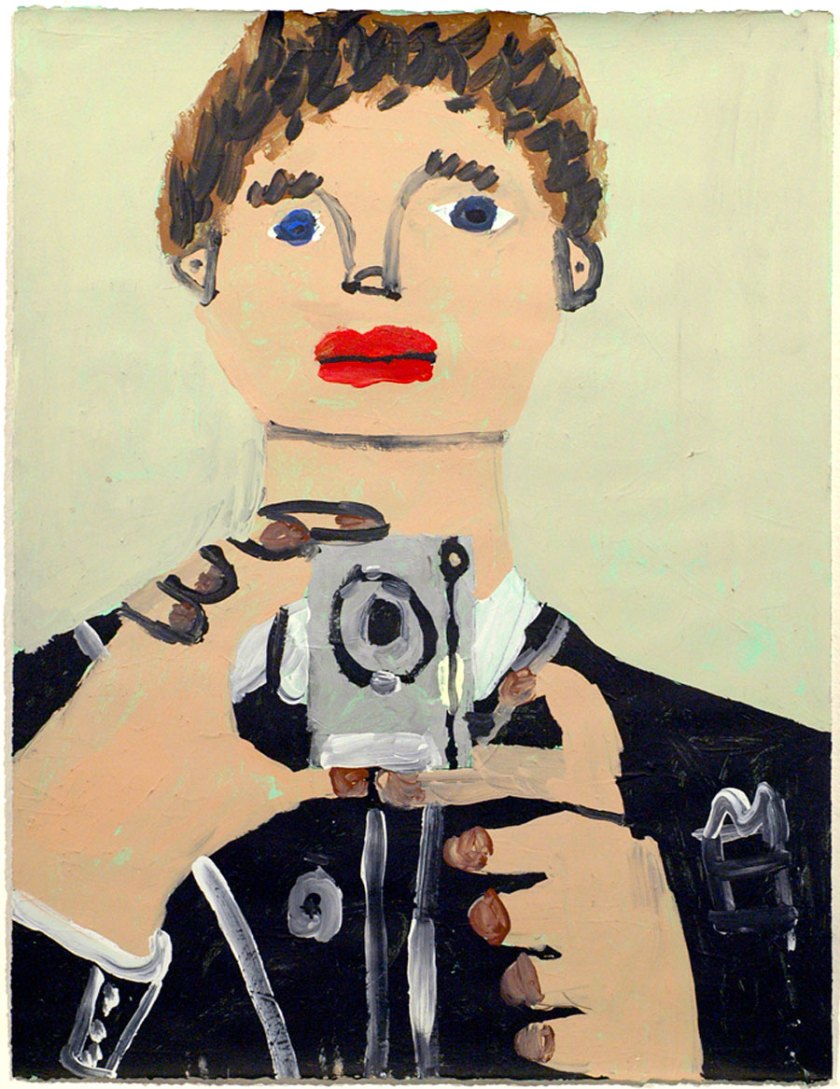

Alan Constable is both a painter and a ceramicist who has exhibited in Australian and International galleries for over 25 years and has been a finalist in a number of significant contemporary art awards. Based on imagery from newspapers and magazines, his recent paintings are notable for their vibrant kaleidoscopic effects and strong sense colour and patterning. Though Constable’s works are often centred on political events and global figures, his thematic concerns are frequently subjugated by the pure visual experience of colour and form. Despite the occasional gravity of his subject matter, there is a genuine sense of joy within Constable’s paintings.

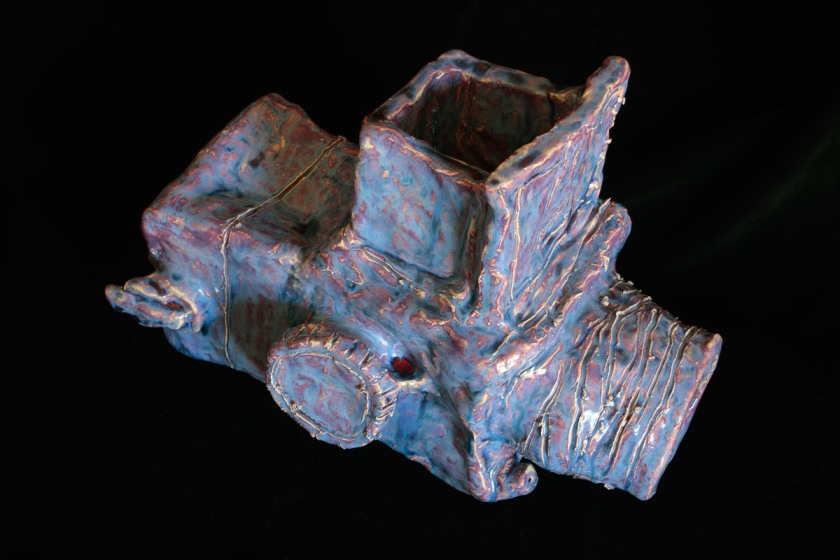

Constable’s ceramic works reflect a life-long fascination with old cameras, which began with his making replicas from cardboard cereal boxes at the age of eight. The sculptures are lyrical interpretations of technical instruments, and the artist’s finger marks can be seen clearly on the clay surface like traces of humanity. In this way, Alan Constable cameras can be viewed as extensions of the body, as much as sculptural representations of an object. Alan Constable’s clay cameras were recently exhibited in Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria. All thirteen cameras displayed were subsequently acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria for their permanent collection.

Peter Atkins (Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne)

Peter Atkins is a leading Australian contemporary artist and an important representative of Australian art in the International arena. Over the past twenty-five years he has exhibited in Australia, New Zealand, England, France, Spain, Italy, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Mexico. His practice has centred around the appropriation and reinterpretation readymade abstract forms and patterns that are collected within his immediate environment, either within a local or international context. This material becomes the direct reference source for his work, providing tangible evidence to the viewer of his relationship and experience within the landscape. Particular interest is paid to the cultural associations of forms that have the capacity to trigger within the viewer, memory, nostalgia or a shared history of past experiences. Recent projects including ‘Disney Color Project’, ‘The Hume Highway Project’, ‘Monopoly Project’ and ‘In Transit’ all reference this collective cultural recall and shared experience.

Peter Atkins has held over 40 solo exhibitions with his survey exhibition titled Big Paintings 1990-2003 touring regional galleries during 2003-04. He has been represented in over fifty significant group exhibitions, including The Loti and Victor Smorgan Gift of Australian Contemporary Art at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Uncommon World: Aspects of Contemporary Australian Art and Home Sweet Home: Works from the Peter Fay Collection, both at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra and more recently in the prestigious Clemenger Contemporary Art Award at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2009/2010. His work is represented in the collections of every major Australian State Gallery as well as prominent Institutional, Corporate and Private collections both Nationally and Internationally. In 2010 his solo exhibition for Tolarno Galleries at the Melbourne Art Fair titled Hume Highway Project was purchased for The Lyon Collection in Melbourne.

Text from the Arts Project Australia website

Peter Atkins with Alan Constable in the Arts Project Australia Studio in Northcote.

Alan Constable work in progress at Arts Project Australia Studio in Northcote. The cameras are inspired by a collection of retro Polaroid cameras collected by Peter Atkins.

Installation views of the exhibition Polaroid Project at Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Two Takes On The Pop Object

Polaroid Project, which brings together Peter Atkins’ re-creations of Polaroid camera packaging and Alan Constable’s versions of the cameras found within those boxes, demonstrates the continued relevance of how artists engage with the objects of consumer culture fifty years after the advent of Pop Art. At first glance, Peter Atkins and Alan Constable seem like unlikely collaborators. Atkins is a painter and Constable is best known as a sculptor, a maker of ceramic cameras. Atkins is invested in reproducing the clean lines and abstract, colourful design of the advertising industry in exacting detail. The lines of Constable’s cameras are never clean. His forms are inherently exaggerated, and the cameras themselves showcase the thumbing, handling, and kneading of the clay medium. If Atkins goes out of his way to convince us that his Polaroid box paintings-cum-sculptures share the near-seamlessness of the real thing, Constable seems to do just the opposite with his cameras. The latter are obviously NOT real cameras: their comic-book personalities, decidedly handmade disposition, their larger-than-life scale, and the fact that they wear their ceramic qualities so proudly (glazed in any number of colours) collectively proclaim their fiction. Despite the apparent disparity of the two artists, both rely exclusively on their own hands to create their work, even when that labour replicates the aesthetic of mechanical reproduction, in the case of Atkins. If we dig deep, we can ascertain a pronounced kinship shared by the two artists that dates back to early Pop in the United States – before the advent of Warhol’s screenprinting techniques that relied on the photograph. Both Atkins and Constable inhabit the handmade rather than the machine-produced realm of Pop, and signal to us that such strategies are still surprisingly timely today despite the digital and highly mediated culture we inhabit.

For nearly 20 years, Peter Atkins has been painting design forms on tarpaulin canvases (occasionally using other supports as well) appropriated from a range of sources including outdoor advertising, record albums, matchbooks, paperback books, product packaging, and street signage. Atkins reduces the essential forms of selected designs by deleting accompanying text and focusing completely on the graphic qualities of the image itself. Atkins has labelled his engagement with the graphic design of packaging and signage ‘readymade abstraction’ – utilising imagery that already exists in the world to transpose and distil into pared-down paintings. Steeped in the gesture of appropriation that has concerned artists for a century now (the readymade made its debut at the 1913 Armory Show when Marcel Duchamp displayed a porcelain urinal as a sculpture), Atkins has worked exclusively as a painter until recently.

Atkins has long been a collector of the objects on which he bases his paintings and the genesis of Polaroid Project firmly demonstrates this. Struck by the iconic graphic design of bright rainbow colour patterns on the original containers for Polaroid instant cameras, Atkins began collecting the camera boxes in earnest about three years ago (the original cameras were still inside the packaging). All of the packages and cameras date between 1969 and 1978; the colour spectrum / rainbow motif evident on the packages is not only indicative of graphic design of the period, but also alludes to the purported chromatic vibrancy of Polaroid film. Atkins knew he wanted to make a body of work using the boxes and was aware that he would be breaking new ground within the evolution of his practice by painting three-dimensionally. Atkins acknowledges that he first ignored what was inside the boxes he was collecting – the cameras themselves. Fetishising the veneer surrounding the product rather than the thing itself, Atkins almost forgot that the purpose of the packaging was to sell cameras. Halfway through the development of the project, Atkins began to marvel at the engineering elegance of the cameras and a light bulb went off in his head – the Arts Project Australia studio artist Alan Constable, recognised for his ceramic sculptures of cameras, would be an inspired collaborator for the project. If Atkins explores the visual language of how we are drawn to things, thereby making images designed for the masses his own, Constable’s skill lies in personalising what is inside the box, transforming a mass-produced consumer product into an idiosyncratic object.

Polaroid Project marks the first time Atkins has focused on replicating consumer packaging in 3D, creating what Donald Judd might have termed ‘specific objects’, art objects that incorporate aspects of painting and sculpture, but do not fit neatly into either category. As Atkins admits himself, his transformed Polaroid camera containers are difficult to categorise: Are they 3D paintings or sculptures? Similarly, they exist in the interstices of Pop and Minimalism, referencing images taken from advertisements, but eliminating descriptive text, distilling ads to abstraction. If it were not for Alan Constable’s cameras exhibited nearby, the viewer would most likely be unable to make the associative leap that these brightly coloured objects are in fact based on commercial packaging that housed and marketed cameras. In order to create boxes that appear as realistic as possible while still retaining proper rigidity as a support for a painting, Atkins used 6mm thick MDF board that he painstakingly sanded, infilling any gaps or surface blemishes with epoxy in order to simulate paper packing material as closely as possible. He then masked out the designs with tape and finally painted the Polaroid signature designs using carefully matched automobile spray paint. What looks machine-printed and fabricated is actually the product of artistic labour. Atkins’ boxes are the same size as the original packaging and are seemingly authentic in every way except for his decision not to reproduce text or photographic imagery, concentrating only on the colourful designs and the cubic format of the container.

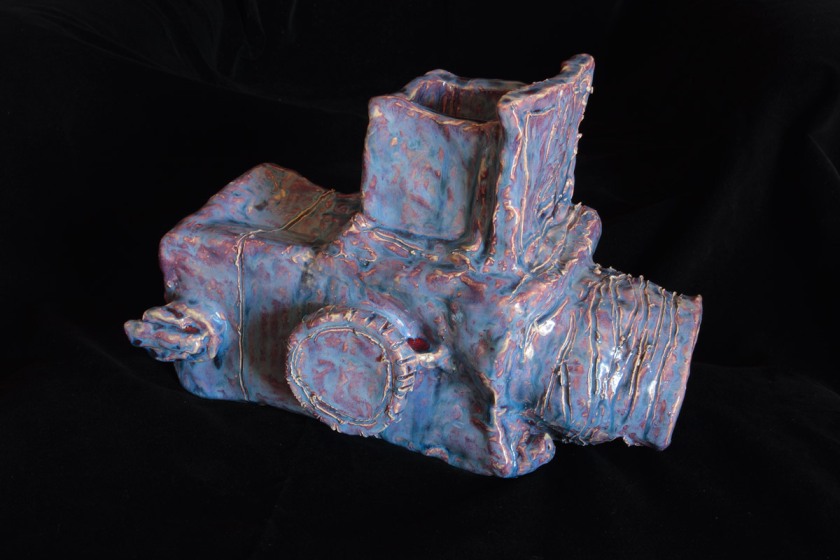

Alan Constable’s glazed ceramic cameras lack precise lines and angles; their handmade wonkiness imbues them with a sentience, as if each sculpture is a character, a refugee from a cartoon narrative. If Philip Guston was a ceramicist, these are the kind of objects he would make. Constable has had a near life-long fascination with cameras. He made his first cameras from cardboard at the age of eight. The ceramic cameras have ranged from accordion-style devices to digital cameras to Polaroids, and all share the noticeable imprint of the artist’s hands and fingers, and quite often, an enlargement of scale compared to their real-world counterparts. Constable is legally blind and has pinhole vision so must work close-up during the creative process. For objects whose very existence are predicated on recording the visible, Constable’s cameras are created far more out of a sense of touch than sight. In Constable’s hands, cameras, which we usually associate with the optical, are transformed into the tactile.

Constable’s cameras are made by adding, subtracting, forming, and inscribing clay. A viewfinder or dial might be modelled separately from the camera body and then grafted on later and finally secured in the firing process. Viewfinders and lenses may be actual apertures or voids, but sometimes (as in the case of Constable’s copies of digital cameras) the display might feature an incised drawing of an imagined landscape, Constable’s take on trompe l’oeil realism. Constable also incises line work onto the camera’s surface to suggest dimension and detail. Constable’s cameras are structurally engineered from the inside out, containing internal chambers and walls to provide inherent stability, but also, perhaps, as a nod to speculative authenticity. Constable usually makes his cameras based on magazine advertisements; for Polaroid Project he had the rare opportunity of using real cameras as models for his sculptures.

Atkins is firmly situated within the handmade domain of the pop object/painting, as his renditions of Polaroid boxes are fabricated and painted only by him not by mechanical means, although the precise and seamless nature of his paint application replicates the look of commercial printing nearly exactly. While Alan Constable also relies on his hands in an endeavour to create a rendering of a commercial product, he does not in any way attempt to copy the Polaroid camera perfectly, or at least the results of his labour do not suggest a desire for verisimilitude. In a certain sense, Atkins plays Roy Lichtenstein to Constable’s Claes Oldenburg – two masters of early 1960s Pop. Lichtenstein made paintings of mass-produced printed imagery – notably comics – enlarging the image to reveal the building block of newsprint, the Ben Day dot. While Atkins does not necessarily play with scale the way Lichtenstein did, he shares with Lichtenstein a keen interest in exploring the imagery of popular culture, transposing it in paint to mimic commercial printing. In his installation The Store (1961), Claes Oldenburg riffed on the consumer products of the day creating handmade, cartoonish objects of exaggerated scale. While Constable forms his cameras out of clay, Oldenburg made his renditions of consumer goods from plaster-soaked muslin formed over wire frames, then painted in enamel – making no attempt to ape the real. Oldenburg’s objects have more in common with paintings than Constable’s cameras, but both amplify scale and instil an animated sensibility in the work, anthropomorphising objects. Lichtenstein and The Store-era Oldenburg represent the extremes of how Pop artists engaged with representation – mimicking commercial printing technology through exacting paintings, on the one hand, versus reproducing commercial goods through awkward handcraft on the other. The pairing of Atkins and Constable shows that the Lichtenstein / Oldenburg diametric is alive and well today and that artists continue to explore different registers of the real in depicting the pop object, relying solely on their own hands.

© ALEX BAKER 2014

Director Fleisher/Ollman Gallery, Philadelphia USA

Reproduced with permission

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Square Shooter 2 #2 (installation view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16.7 x 16.7 x 18.4cm

Camera: 16 x 14 x 16cm

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Super Shooter (installation view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16 x 17.5 x 18cm

Camera: 16 x 14 x 16cm

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Colorpack ll (installation view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16.7 x 16.7 x 19.8cm

Camera: 15.5 x 16 x 20cm

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Colorpack ll (detail)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Camera: 15.5 x 16 x 20cm

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

The Clincher (detail)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Camera: 17.5 x 18 x 18cm

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Colorpack 82 (catalogue view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16.7 x 16.7 x 18.4cm

Camera: 16.5 x 14.5 x 20cm

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Super Color Swinger (catalogue view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16.7 x 16.7 x 18.4cm

Camera: 17 x 15 x 15cm

Alan Constable and Peter Atkins

Square Shooter 2 (with flash) (catalogue view)

2014

Ceramic camera and auto acrylic on MDF

Box: 16.7 x 16.7 x 18.4cm

Camera: 17 x 14 x 18cm

Arts Project Australia

Studio

24 High Street

Northcote Victoria 3070

Phone: + 61 3 9482 4484

Gallery

Level 1 Perry Street building

Collingwood Yards

Enter via 35 Johnson Street or 30 Perry Street, Collingwood

Phone: +61 477 211 699

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Friday 11am – 5pm

Saturday & Sunday 12 – 4pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.