Exhibition dates: 15th January – 15th April 2016

Installation view of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing from left to right, Trooper M, after Afghanistan (2012); and Trooper M, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (2012)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

This is the most profound exhibition that I have seen so far this year. Simply put, the exhibition is magnificent … a must see for any human being with an ounce of understanding and compassion in their body.

While I am vehemently anti-war, and believe that we should have never have been in Afghanistan in the first place, these sensual and skeletal paintings represent the danger that these soldiers exposed themselves to in the line of duty. The sensuousness and vulnerability of their solitary, contorted poses – poses which they themselves chose to for Quilty to paint – reflect an actual event, such as taking cover to engage insurgents. That these naked poses then turn out to have a quiet eroticism embedded in them confirms the link between eroticism, death and sensuality as proposed by Georges Bataille. The three forms of eroticism (physical, emotional, religious) try to substitute continuity (life) for discontinuity (death). In these paintings the soldiers lay bare their inner self. They bring forth experiences that have been buried – their dissociation from the reality of what occurred, the experiences they have repressed, the post-traumatic stress – brought to the surface and examined in these paintings through the re-presentation of suppressed emotions, through a form of emotional eroticism, a primordial rising of eroticism, death and sensuality. An affirming act of life over death.

As an artist, Quilty intimately understands this process. I think a strong element of this exhbition is the feeling that there is something missing, that the range of concerns is lacking something. I suspect this is deliberate. Something is being withheld. And what is being withheld in the paintings is, I believe, narrative.

While there is an overarching text narrative – soldiers painted “after Afghanistan” – and individual paintings have titles such as Sergeant P, Troy Park, Trooper M and Trooper Daniel Westcott, these paintings could almost be of any human being who has been a soldier. Other than the specific triptych of Air Commodore John Oddie (and even then the portraits remind me of the ambiguity of Francis Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953), these paintings could be of any soldier. As Gerhard Ricther observes, “You can only express in words what words are capable of expressing, what language can communicate. Painting has nothing to do with that.” After Richter, you might say that “there is no plan”, there is only feeling in the work of Ben Quilty, embodied through his brush. Here, I see links to the work of that great British painter, Francis Bacon.

“Bacon was deeply suspicious of narrative. For him, narrative seems to be the natural enemy of vision; it blinds… Bacon seems to propose an opposition between narrative as a product that can be endlessly reproduced, as re-presentation – the ‘boredom’ is inspired by the deja vu of repetition – and narrative as process, as sensation. Conveying a story implies that a pre-existing story, fictional or not, is transferred to an addressee. Narrative is then reduced to a kind of transferable message. Opposed to this ‘conveying of story’, ‘telling a story’ focuses on the activity or process of narrative. This process is not repeatable; it cannot be iterative because it takes place, it happens, whenever ‘story’ happens… Bacon’s hostility toward narrative is directed against narrative as product, as re-presentation, not against narrative as process.

(Bacon) does not paint characters, but figures. Figures, unlike characters, do not imply a relationship between an object outside the painting and the figure in the painting that supposedly illustrates that object. The figure is, and refers only to itself.”1

The figure is, and refers only to itself, and it is up to the viewer to actively interpret this telling of the story each time they view one of Quilty’s paintings. There is no transferable message.

Further, much like Bacon’s triptychs, Quilty’s paintings depict isolated figures or figural events on the panels. The figures are isolated in their space and their is never any clear interaction between the figures. “Bacon explains the use of the triptych as follows: ‘It helps to avoid storytelling if the figures are painted on three different canvases’ … The figures never fully become characters, while the figural events are never explained by being embedded in a sequence of events. The figures interact neither with each other nor with their environment. Although Bacon’s paintings display many signs which traditionally signify narrativity, by the same token any attempt to postulate narratives based on the paintings is countered.”2

In these paintings, Quilty does not turn away from the evidence of the soldiers before him who express through their bodies that life is violent. He does not attempt to save the viewer from such unpleasantries. As Bacon comments, “The feelings of desperation and unhappiness are more useful to an artist than the feeling of contentment, because desperation and unhappiness stretch your whole sensibility.” Quilty stretches his sensibility as an artist and as a human being by getting down and dirty with his subject matter, both physically and emotionally. In fact, I would say Quilty becomes his subject, so close does the artist get to the object of his attention (after all, this is also Quilty’s experience of Afghanistan, as much as it is the soldiers who he is painting. The artist is always present in the work). The closer you get to one of his paintings, the more the detail vanishes and the more the paint becomes like blood and guts. The artist presses up against his subject which dissolves into abstraction. A bravura tour de force of painting that it so confident in its intent… [that there are] huge stretches of bare white canvas as flesh, with these striking gestures for throat and nipple executed without fear in one stroke of the brush. The black hole appearing out of the side of the soldiers head reminds me of Carl Jung’s ambivalent feelings toward his unconscious shadow; and at one end of the gallery you have a black hole (Trooper Luke Korman, Tarin Kot, 2012, below) and at the other a white hole (Trooper Luke Korman, 2012, below), such are the energies of yin yang that flow through the lighter of the gallery spaces.

Using what the photographer Imogen Cunningham termed the ‘paradox of expansion via reduction’ – closing in on subject (either physically and/or mentally), the intensity and focus attendant to a clear way of seeing – allows Quilty’s work to be flooded with sensuality and reductive power. The horror of the body, of how fragile we are (Damien Hirst) is expressed through the visceral paint. The viewer’s mind tells the story, creates the horror, the closer you get to the work. As I said earlier, there is no transferable message, no actual interpretation but universal triggers that impinge on the viewer’s mind. Quilty plays with the flow of time and space, memory and war by disassociating himself from traditional narrative. As the quotation below from Peter Handke’s novel Across eloquently expresses it, it is a sense of “being-empty” (Zen), an empty form that is also full at the same time. Every object in Quilty’s opus moves into place and we pass over, quietly, into a place we have never been before, through paintings that picture the unknowable. Something we have never seen or felt before. In painting, I don’t think there are many artists that could have achieved what Quilty has with this body of work.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,125

Many thankx to Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan, the artist and Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum

1/ Ernst Van Alphen. Francis Bacon and the Loss of Self, 1992 quoted in “Francis Bacon and ‘Narrative’, the Natural Enemy of Vision,” on the ASX website, June 27 2013 [Online] Cited 29/03/2016.

2/ Ibid.,

“With the light of that moment, silence fell. The warming emptiness that I need so badly spread. My forehead no longer needed a supporting hand. It wasn’t exactly a warmth, but a radiance; it welled up rather than spread; not an emptiness, but a being-empty; not so much my being-empty as an empty form. And the empty form meant: story. But it also meant that nothing happened. When the story began, my trail was lost. Blurred. This emptiness was no mystery; but what made it effective remained a mystery. It was as tyrannical as it was appeasing; and its peace meant: I must not speak. Under its implosion, everything (every object) moved into place. “Emptiness!” The word was equivalent to the invocation of the Muse at the beginning of an epic. It provoked not a shudder but lightness and joy, and presented itself as a law: As it is now, so shall it be. In terms of image, it was a shallow river crossing.”

Peter Handke. Across. Ralph Manheim (translator). Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000, p. 5.

“I do not want to avoid telling a story, but I want very, very much to do the thing that Valery said – to give the sensation without the boredom of its conveyance. And the moment the story enters, the boredom comes upon you.”

Francis Bacon

Installation view of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing from left to right, Sergeant P, after Afghanistan (2012); Trooper Daniel Westcott, after Afghanistan (2012); and Troy Park, after Afghanistan (2012)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Sergeant P, a Special Operations Task Group soldier, is a survivor of a Black Hawk helicopter crash that claimed the lives of three Australians. Some of the soldiers depicted in the other portraits witnessed the crash and were first on the scene to provide assistance. The memory of this experience, and the friends who did not make it, will stay with these men for a long time.

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper Daniel Westcott, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Troy Park, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing from left to right in the bottom three images, Troy Park, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (2012); Trooper M, after Afghanistan (2012); and Trooper M, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (2012)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Troy Park, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Quilty asked the soldiers to suggest a post that encapsulated some of the emotions that surrounded their experience in Afghanistan. Often the pose is quite contorted, as it reflects an actual event, such as taking cover to engage insurgents.

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper M, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“You can’t really stop out there. You have to keep doing your job and keep moving forward … There is no time, until you get home, to stop and think about it.”

Trooper M

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper M, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (installation view detail)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“Sitting for Ben is therapeutic; it does get a lot of stuff off your chest. And actually seeing your portrait on canvas, I think for me it’s definitely a chapter that I can close and leave there.”

Trooper M

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Bushmaster (installation view)

2012

Aerosol and oil on linen

Donated by Ben Quilty through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program in 2013

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Portraiture for Quilty can also take a vehicle as its subject. This destroyed Bushmaster reflects the soldiers’ identity and is a vestige of their physical experience. They risk their lives while carrying out their duties in these versatile military vehicles.

“I met a young man who’d been in the back of a Bushmaster that had blown up. The Bushmaster is the big armoured four-wheel-drive vehicle that’s saving a lot of Australian lives, but even so the explosion caused every single you man inside that vehicle to suffer from concussion and one of them was blown out of the gun turret and landed in front of the vehicle among possibly more hidden explosive devices.”

Ben Quilty

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Captain S, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“I think when Ben paints, he’s not looking for what’s on the outside … He’s more after what they’re feeling o what they’ve been through … He’s looking at the inner instead of just the outer.”

Captain S

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Lance Corporal M, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Lance Corporal M, after Afghanistan (installation view detail)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The naked portraits have a sensuousness and vulnerability in their solitary, contorted poses. The rough surface signifies the uniform and body armour that have been stripped away in front of us, and them. We and they recognise what they have endured and achieved.

“I wanted [this soldier] to be naked, showing not only his physical strength but also the frailty of human skin and the darkness of the emotional weight of the war.”

Ben Quilty

Installation view of drawings from the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery including, at bottom left, Captain M II, Tarin Kot (October 2011, below) and third from left top, Waiting, Tarin Kot (October 2011, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“This very wild place”

Sitting and talking with the Australian soldiers in Afghanistan, Quilty became intrigued by their experiences. He came to feel responsible for telling the stories of these young men and women.

“I started doing drawings of the soldiers, and hearing their stories about their experiences of being in this very wild place. I realised that I needed to just sit with them … making portraits of these guys in Tarin Kot or wherever I was … getting them to sit still and talk to me about their experience. Those little drawings are a reminder to me of the time that I spent with those people. I hoped that there’d be some remnant of that experience that I could then draw out … to put into the paintings when I returned to Australia.”

Ben Quilty

The trust that Quilty developed with these soldiers in Afghanistan was strong enough to continue at home in Quilty’s studio, where he invited some to sit for larger portraits.

(top row, first three from left)

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Private C, Tarin Kot

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured felt tip pen on paper

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper M, Special Forces, Tarin Kot

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured felt tip pen, pencil and ink wash on paper

Collection of the artist

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Captain Kate Porter

27 October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured pencil and ink wash on paper

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

(bottom row, first three from left)

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Sergeant M II, Tarin Kot

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Pencil and ink wash on paper

Collection of the artist

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Chinook pilot, Kandahar Airfield

October 2011

Drawn at Kandahar Airfield, Kandahar province, Afghanistan

Pencil and ink wash on paper

Collection of the artist

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Brigadier General Noorullah, Afghan National Army, Tarin Kot

22 October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured felt tip pen on paper

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

While in Tarin Kot, Quilty attended a marching out parade of 400 Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers who had completed training under the Australian Mentoring Task Fore. There he met a senior ANA commander, Brigadier General Noorullah. Just days later, three Australian soldiers were killed at a similar training parade being held at Forward Operating Base Sorkh Bed (aka Pacemaker). Quilty learnt of the incident the day after he left Afghanistan, giving him an even greater sense of the dangers that the soldiers he met face daily.

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Captain Kate Porter (installation view)

27 October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured pencil and ink wash on paper

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Quilty wanted to meet a cross-section of people serving in Afghanistan – soldiers driving Bushmasters, Chinook pilots, Special Forces soldiers, and both men and women of all ranks – to try to understand who makes up the Australian Defence Force. He met Captain Kate Porter at Tarin Kot. There he spoke to her about her experiences as female in the very masculine community of the Special Operations Task Group, as well as her general experience as a soldier in Afghanistan.

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper M, Special Forces, Tarin Kot (installation view)

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured felt tip pen, pencil and ink wash on paper

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Waiting, Tarin Kot (installation view)

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Coloured felt tip pen on paper

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Captain M II, Tarin Kot (installation view)

October 2011

Drawn at Tarin Kot, Uruzgan province, Afghanistan

Pencil and ink wash on paper

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan is an extraordinary Australian War Memorial Touring Exhibition by one of the nation’s most incisive artists, and is of great relevance to all Australians. The exhibition officially opens at Castlemaine Art Gallery on Friday 15 January 2016.

The exhibition itself was the result of the Archibald Prize-winning artist’s three-week tour across Afghanistan in October 2011. Engaged as an Official War Artist, his purpose was to record and interpret the experiences of Australians deployed as part of Operation Slipper in Kabul, Kandahar, and Tarin Kot in Afghanistan and at Al Minhad Airbase in the United Arab Emirates. In fulfilling his brief, Quilty spoke with many Australian servicemen and women, gaining an insight into their experiences whilst serving in the region, and ultimately leaving with an overwhelming need to tell their stories.

Quilty recently spoke on ANZAC Day 2015 and paid tribute not only to those who did not return from Afghanistan and their grieving families, but also to “the young men and women who live amongst us who have paid so dearly and will quietly wear the thick cloak of trauma for many years to come, after Afghanistan.”

The exhibition is a must see as Quilty is arguably one of Australia’s greatest living painters, and this exhibition, with its intense and emotional subject matter is particularly important to Castlemaine, a town with a history of young men and women serving their country far from home. The exhibition has been very well received across the country with over 70,000 visitors attending the works when on display most recently in Darwin. Dr Brendan Nelson, Director of the Australian War Memorial believes Quilty should be considered one of Australia’s great official war artists.

“Ben Quilty’s works follows a truly great tradition at the Australian War Memorial of appointing artists to record and interpret the Australian experience of war.”

“Ben brought to this task all his brilliance, sensitivity and compassion. The works he produced will leave Australians a legacy which informs them not only about the impact of war on our country, but even more importantly, about the effects on the men and women he has depicted,” said Dr Nelson.

Dr Jan Savage, President of the Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum Committee of Management said the exhibition, “was significant in understanding the impact of war on serving members of the Australian armed forces and I encourage visitors to attend this most important exhibition.”

Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan is on display at Castlemaine Art Gallery from 15 January until 15 April 2016.

An Australian War Memorial Touring Exhibition, proudly sponsored by Thales.”

Text from the Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum website

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Tarin Kot, Hilux (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Kandahar (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Kandahar (installation view detail)

2012

Oil on linen

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Kandahar Airfield is a multinational vase with approximately 35,000 people from the International Security Assistance Fore, aid organisations, and a pool of local civilian staff. Weapons are carried at all times by both military and civilian personnel, creating a tense atmosphere with a violent undercurrent. Quilty described Kandahar as being a cross between the worlds of Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome and Catch 22, a surreal, dusty, and violent place. “For the first week in Kandahar, I basically felt like I was dodging rockets. The first night we landed there, two or three rockets landed inside the compound.”

This painting was Quilty’s first visceral response on his return from Afghanistan and i sums up his emotions, particularly his personal experience of Kandahar and being a part of the maelstrom of war.

Installation view of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing at centre, Tarin Kot, Hilux (2012); and at right, Kandahar (2012)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing at left in the bottom image, Air Commodore John Oddie, after Afghanistan, no. 3 (2012, below)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Returning from war

“You can’t take the experiences out of your head.

You can’t take the damages out of your head.”

John Oddie

On his return to Australia, Ben Quilty contacted Air Commodore John Oddie (Ret’d), whom he had met during his Afghanistan deployment, to invite him to sit for a portrait in his studio. From February to October 2011, Oddie had been the Deputy Commander of Australian forces in the Middle east, a position of immense responsibility.

Quilty eventually produced three portraits over five months. These works reveal a man returning from war and its burden of responsibility, exhausted emotionally and mentally, and his progress towards a more positive view of life and of himself as a survivor.

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Air Commodore John Oddie, after Afghanistan, no. 3 (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Air Commodore John Oddie, after Afghanistan, no. 3 (installation view detail)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“I don’t necessarily see beauty, I see insight in what Ben does. That’s reflected in the way he paints … I think his later portraits, done after he’s got to know us better, are different from the raw emotion of the first ones.”

John Oddie

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Air Commodore John Oddie, after Afghanistan, no. 1 (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“With through a lack of insight or through an unwillingness … I wasn’t always admitting the truth to myself about my life. Ben really took that out and put it on a table in front of me like a three-course dinner and said, well, how about that? And you know, I sort of thought well, I’m not going to come to this restaurant again in a hurry!”

John Oddie

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Air Commodore John Oddie, after Afghanistan, no. 2 (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

“He’s got this one little gash of paint and it brings out this wry smile that I didn’t even know I had … When I stood back and had a look, I was just stunned at the honesty of the painting – until then I hadn’t really been fully honest with myself about what I was feeling.”

John Oddie

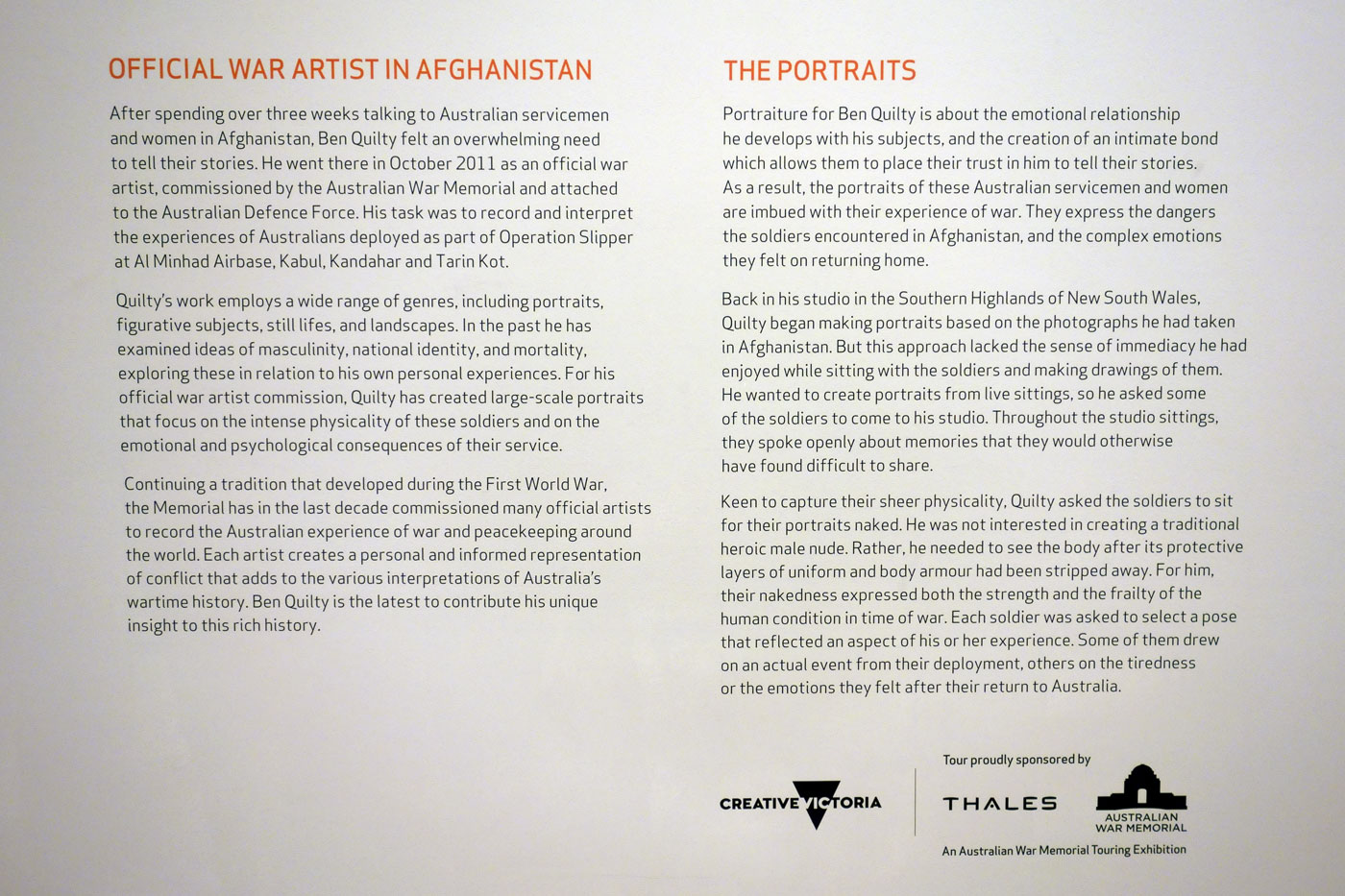

Introductory titles and text for the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing the work Trooper Daniel Spain, Tarin Kot (2012, below)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper Daniel Spain, Tarin Kot (installation view)

2012

Oil on linen diptych

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In some of the works, Quilty has used dramatic symbols to represent the emotional weight and the sense of emptiness he felt some soldiers brought home with them after Afghanistan. The black hole motif also reflects his own feelings of anxiety and uncertainty during his time there.

“I had such extreme feelings about the smell, sound, emotions of being in Afghanistan … I wanted to convey this.”

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper Luke Korman (installation view)

2012

Aerosol and oil on linen

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Ben Quilty: After Afghanistan at the Castlemaine Art Gallery showing on the far wall, Trooper Luke Korman, Tarin Kot (2012, left) and SOTG, after Afghanistan (2011, right)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

Trooper Luke Korman, Tarin Kot (installation view)

2012

Aerosol and oil on linen diptych

Collection of the artist

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Ben Quilty (Australian, b. 1951)

SOTG, after Afghanistan (installation view)

2011

Oil on linen diptych

Acquired under the official art scheme 2012

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

As part of his initial idea for the war artist commission, Quilty photographed soldiers of the Special Operations Task Group in Afghanistan in the same pose. He asked each of them to face the sun with their eyes closed, then open them and stare into the blinding light. At that instant Quilty would take the photograph. “To me, this symbolises what they’re facing, something immense, overwhelming.”

Back in Australia, Quilty attempted to work from these photographs, and created a handful of portraits. He was dissatisfied with the results. Determined to re-establish a personal connection with his subjects, he invited some of them to sit for portraits in his studio.

Castlemaine Art Gallery and Historical Museum

14 Lyttleton Street (PO Box 248)

Castlemaine, Vic 3450 Australia

Phone: (03) 5472 2292

Email: info@castlemainegallery.com

Opening hours:

Thursday – Saturday 11am – 4pm

Sunday 12pm – 4pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.