Exhibition dates: 3rd February – 7th May, 2023

Originating curator: Lisa Volpe

Cincinnati Art Museum curator: Nathaniel M. Stein

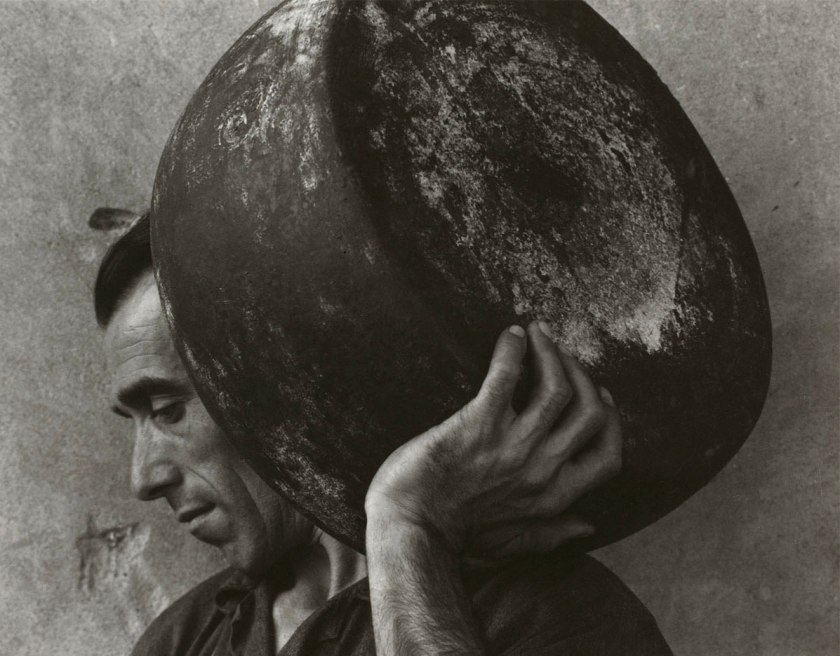

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Chrysler Building from the Window of the Waldorf Astoria, New York

c. 1960

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

O’Keeffe was unconcerned with creating perfect photographic prints and none of these photographs by Georgia O’Keeffe are memorable but the photographs help inform her art practice, acting as a form of documentary sketch rather than being about the art of photography. Perhaps for O’Keeffe it’s about a clarity of looking, and then looking again at the pictorial plane, in order to abrogate in her paintings a photographic reality that is always unreal in the first place.

Form, light, perspective and place in photographs are all reframed through O’Keeffe’s intuitive mind’s eye resulting in the physical painting so conceived. They inform her creative reimag(in)ings and expressive compositions of the landscape. The formal elements of the photographs, their light and shade, their depth and weight, are rendered – depicted artistically, become, made, translated, performed, surrendered – abstractly in the medium of paint, substituting one perceived reality for another. But the paradox is, what is being seen here, what does O’Keeffe see in her relations with the camera?

“To apprehend myself as seen is, in fact, to apprehend myself as seen in the world and from the standpoint of the world. The look does not carve me out in the universe; it comes to search for me at the heart of my situation and grasps me only in irresolvable relations with instruments. If I am seen as seated, I must be seen as “seated-on-a-chair,” … But suddenly the alienation of myself, which is the act of being-looked-at, involves the alienation of the world which I organise. I am seated on this chair with the result that I do not see it at all, that it is impossible for me to see it …”1

Everything (photography, painting, self, world) is in dis/agreement, everything is up for negotiation – as nothing is “in fact”. What did you say?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Jean-Paul Satre. Being and Nothingness (trans. Hazel Barnes). London: Methuen, 1966, p. 263.

Many thankx to the Cincinnati Art Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

How well do we know iconic American artist, Georgia O’Keeffe? Scholars have examined her paintings, home, library, letters, and even her clothes. Yet, despite O’Keeffe’s long and complex association with the American photographic avant-garde, no previous exhibition has explored her work as a photographer.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer presents nearly 100 photographs by the artist, together with a complementary selection of paintings and drawings. These works illuminate O’Keeffe’s use of the camera to further her modernist vision, showing how she embraced photography as a unique artistic practice and took ownership of her relationship with the medium. Discover, for the first time, O’Keeffe’s eloquent and perceptive photographic vision.

Through Another Lens: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Photography

Georgia O’Keeffe is revered for her iconic paintings of flowers, skyscrapers, animal skulls, and Southwestern landscapes. Her photographic work, however, has not been explored in depth until now. Originating exhibition curator Lisa Volpe joins us from The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, to discuss O’Keeffe’s relationship to and personal use of photography, the research that brought this history to light, and the discoveries still waiting to be made.

“There’s an incredible clarity in the way that she thought about composition and the way that forms fill a space the most beautifully… That was her primary concern, and that’s what she’s interested in photographing. It’s not about making a pretty picture or even showing what her dogs look like or any of those things. It’s about what the image looks like as a picture.”

Nathaniel Stein, Cincinnati Art Museum curator of photography

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Spotting Kit

Late 1910s – late 1940s

Various materials

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Gift of Juan and Anna Marie Hamilton

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Before the advent of digital retouching, flaws in a photographic print, such as dust spots or scratches, were covered on the print surface with a brush and spot tone dye. “Spotting” is a demanding process that requires patience, precision, and a sensitivity to tone. O’Keeffe first learned the technique while assisting Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) in the late 1910s. Decades later, she used her kit again, to eliminate visual interference in the perfect tonal masses and shapes in her own photographs. O’Keeffe’s mastery of painting easily translated to spotting – her touch-ups are so fine that they are almost imperceptible.

Large print label to the exhibition

Most people know renowned artist Georgia O’Keeffe as a painter. What they probably don’t know? O’Keeffe was also a passionate photographer. Soon, visitors can see a selection of her photographs at the exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, coming to the Cincinnati Art Museum February 3 – May 7, 2023.

In the first major investigation of O’Keeffe’s 30-year engagement with photography, Cincinnati Art Museum visitors can gain a rare, new understanding of the artist. More than 100 photographs and a complementary selection of paintings, drawings and objects from O’Keeffe’s life tell the story of her eloquent use of the camera to pursue her singular artistic vision.

“For me, an exciting facet of this project is how it shifts the paradigm for multiple audiences,” states Cincinnati Art Museum Curator of Photography Nathaniel M. Stein, PhD. “Photography buffs are learning her relationship with photography was larger and more complicated than we knew. I think those audiences will be surprised by the sophistication and rigour of O’Keeffe’s own exploration of photographic seeing, even as they have to let go of an assumption that she would be making photographs in service of her painting practice. On the other hand, audiences arriving out of admiration for O’Keeffe as a painter are coming to know the artist’s vision in an entirely new way, seeing her digest the world more clearly and gaining an understanding of elemental tenets of photographic composition and form through her eyes.”

Exhibition overview

Georgia O’Keeffe is the widely admired “Mother of American Modernism” who has long been examined by scholars for her paintings of flowers, skulls, and desert landscapes. Despite being one of the most significant artists of the 20th century, no previous exhibition has explored her work as a photographer … until now.

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue containing new scholarship by Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Curator of Photography Lisa Volpe and a contribution from Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Curator of Fine Arts Ariel Plotek. The catalogue will significantly broaden readers’ understanding of one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century. It will be available soon for purchase from the museum shop in person and online.

Press release from the Cincinnati Art Museum

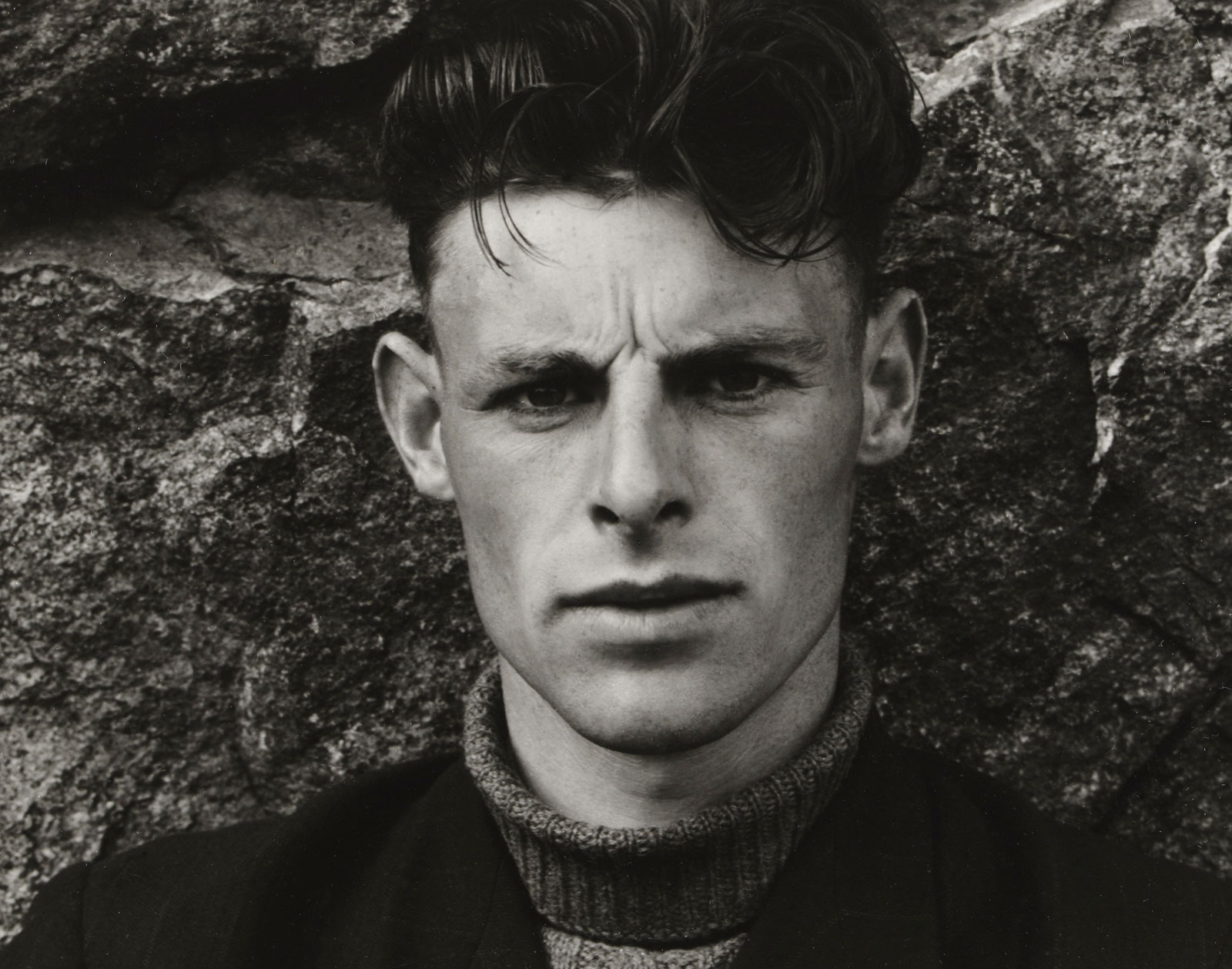

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946)

Georgia O’Keeffe

1933

Gelatin silver print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: The Target Collection of American Photography

Museum purchase funded by Target Stores

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Gallerist, publisher, and photographer Alfred Stieglitz made his first portrait of O’Keeffe in 1917 at the beginning of their romantic relationship. Over the next 20 years, he photographed her more than 300 times. Due in large part to Stieglitz’s epic portrait project and his outsized legacy in the American art world, historians have assumed that O’Keeffe’s relationship to photography was passive – that of a sitter, assistant, or spectator. However, O’Keeffe’s photographs prove that she developed her own visionary practice behind the camera.

Large print label to the exhibition

“It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

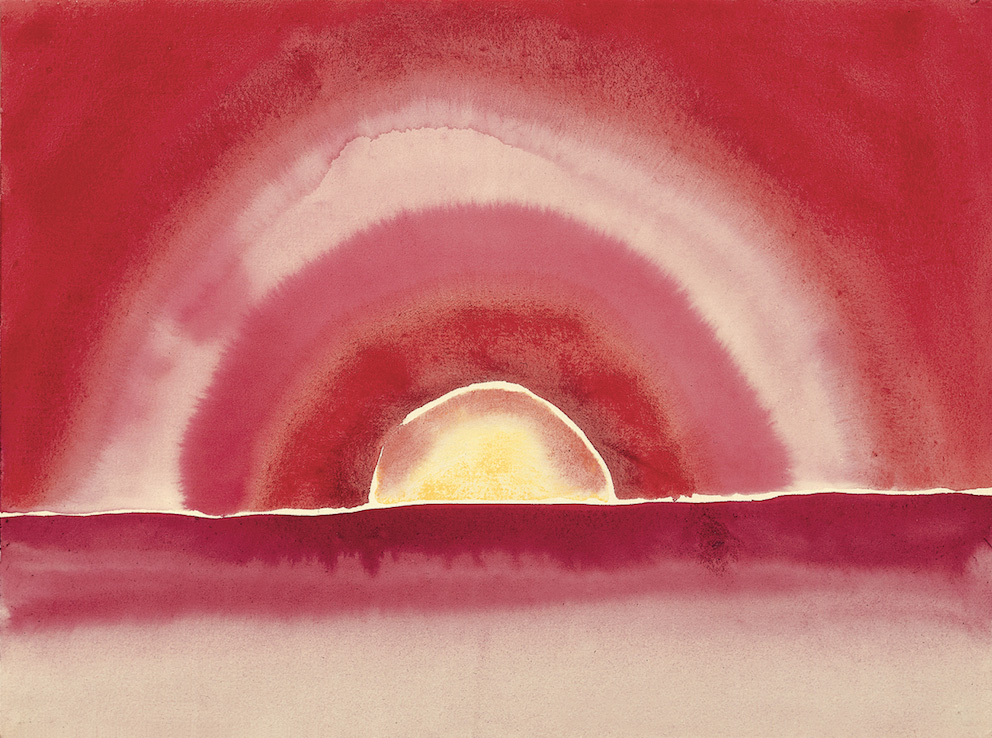

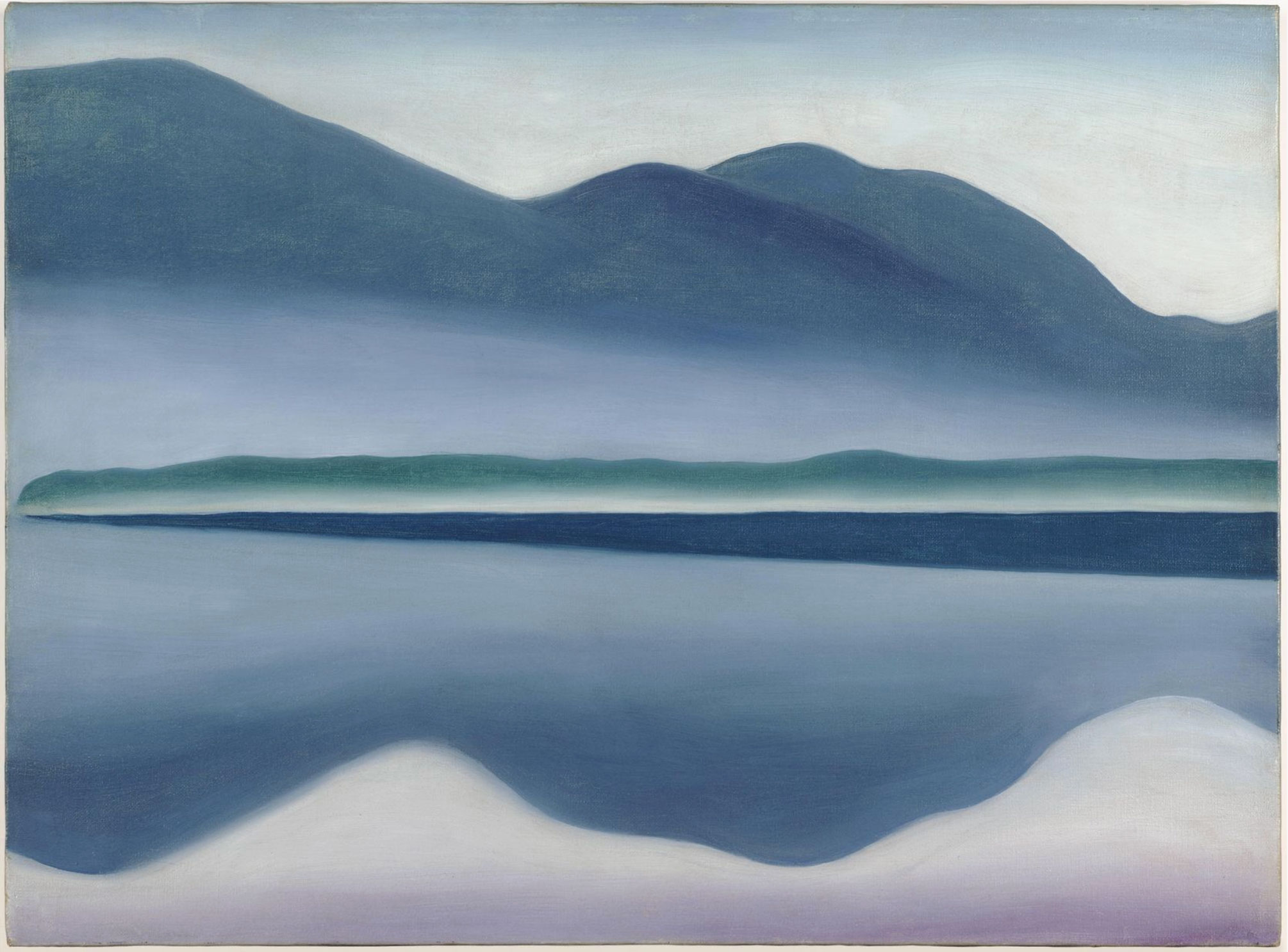

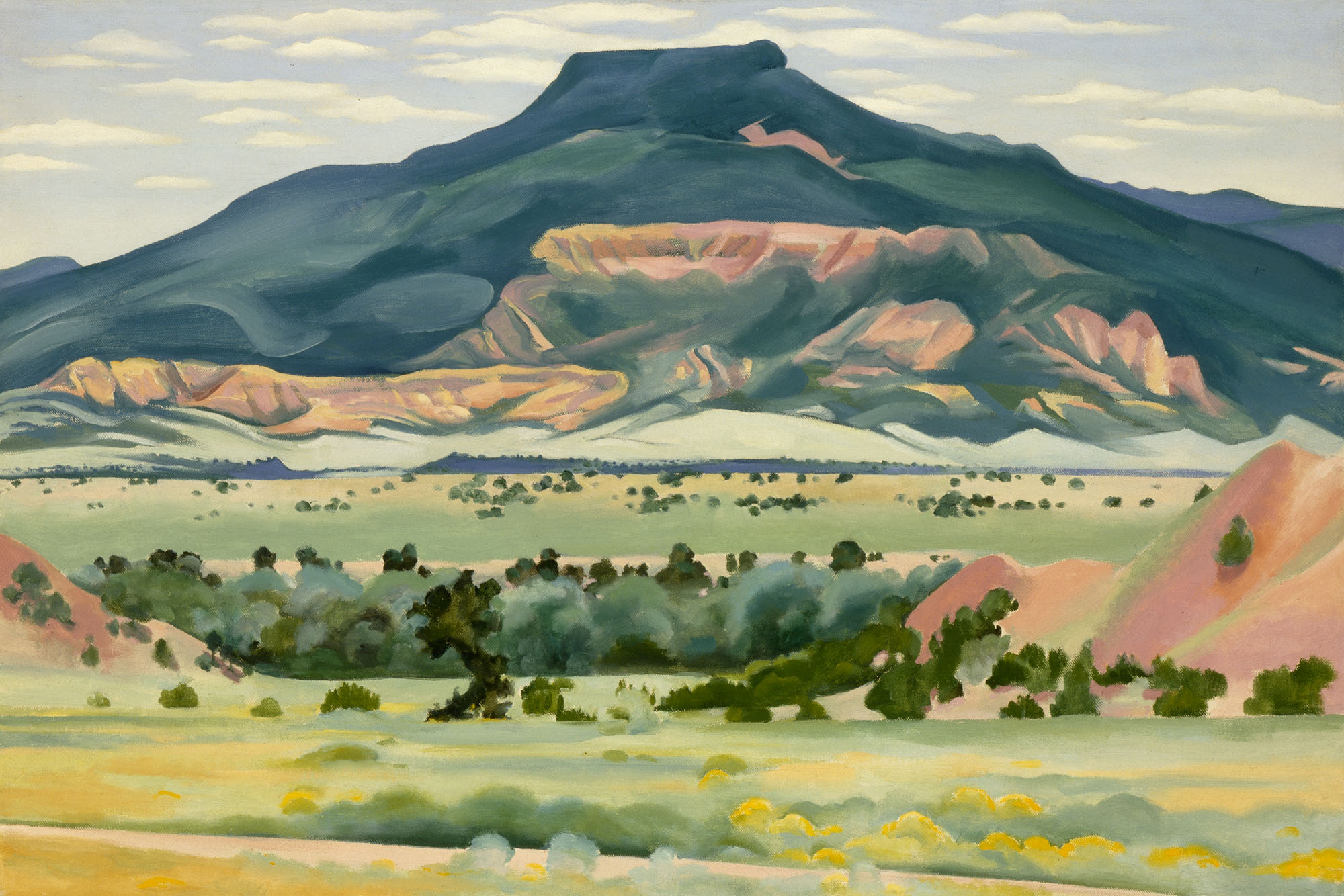

American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) strived to give visual form to “the unexplainable thing in nature that makes me feel the world is big far beyond my understanding … to find the feeling of infinity on the horizon line or just over the next hill.”

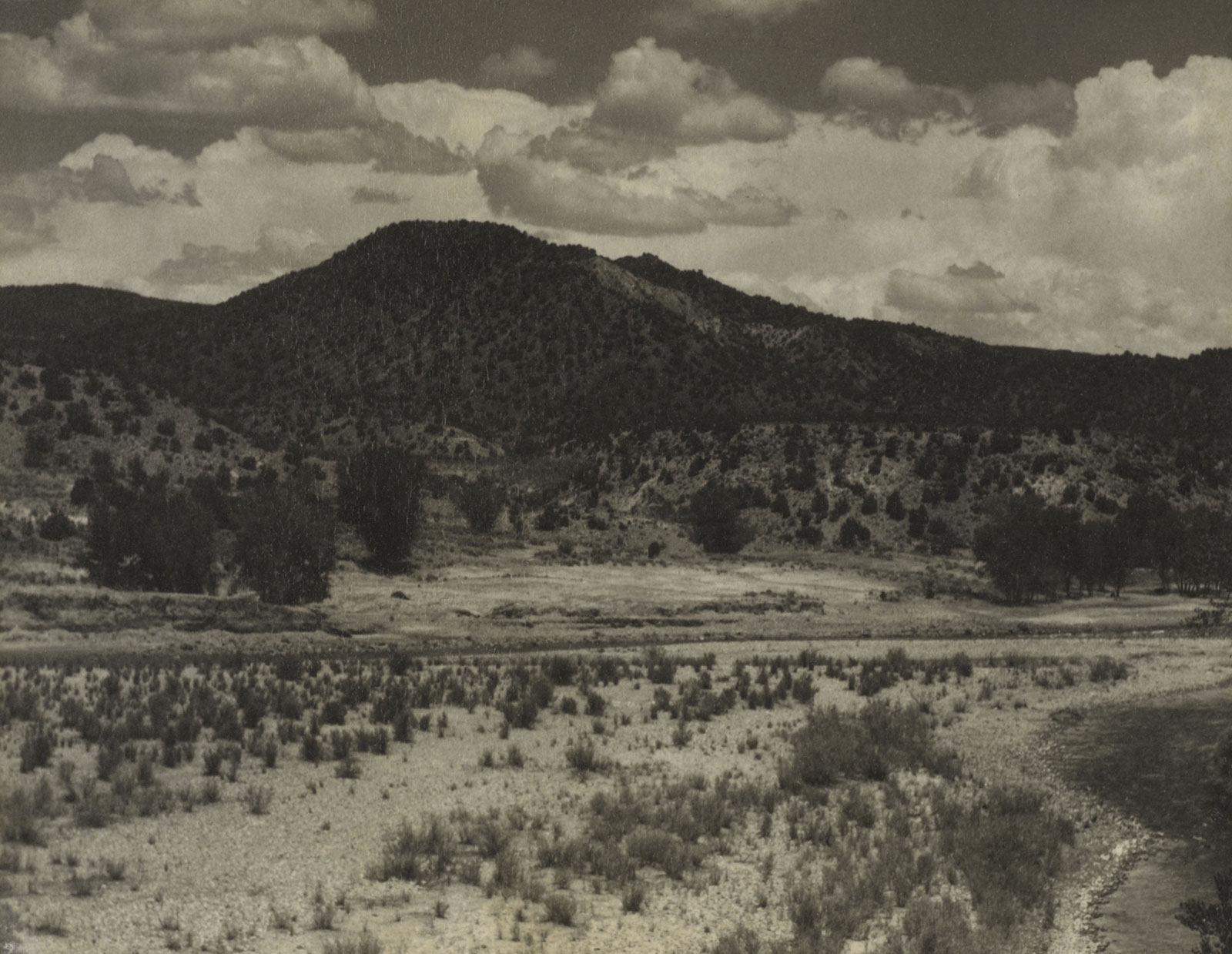

After nearly thirty years rendering the vistas of the Southwest on canvas, O’Keeffe still sought new ways to express the beauty and essential forms of the land in all its cycles. She produced more than 400 photographs of her New Mexico home, its surrounding landscape, and other subjects in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Photography offered a new means of artistic engagement with her world. Revisiting subjects she painted years or even decades earlier, O’Keeffe explored new formal and expressive possibilities with the camera.

Like her work in other media, O’Keeffe’s photographs demonstrate an acute attention to composition and passion for nature. Her photography provides a window into an artistic practice based on tireless looking and reconsideration. O’Keeffe used the camera to capture both momentary impressions and sustained investigations over the course of days, seasons, and years. Alongside her better-known paintings and drawings, O’Keeffe’s photographs open new insight into her unending dialogue with the world around her.

Introduction

From the mid-1950s until the 1970s, Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) produced more than 400 photographic images, focused primarily on her New Mexico home and the surrounding landscape. After rendering the vistas of the Southwest on canvas and paper for over 25 years, the artist still sought new ways to express the beauty of the land in all its cycles and forms. Photography offered O’Keeffe a new means of artistic engagement with her world. Revisiting subjects she painted years, or even decades, earlier, the artist’s photographs explored new formal and expressive possibilities.

Her photographs reveal the same passion for nature and acute attention to composition that we see in her paintings and drawings. Through photography, O’Keeffe captured multiple momentary impressions and recorded sustained investigations over the course of days, seasons, and years. Alongside her better-known paintings and drawings, O’Keeffe’s photographs reveal her unending, unique dialogue with the natural world.

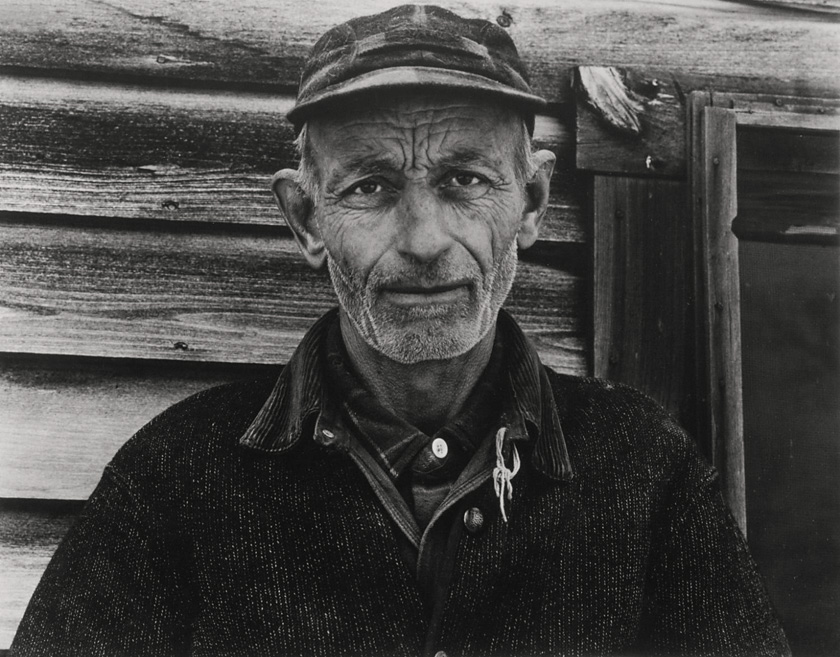

A Life in Photography

O’Keeffe was no stranger to photography. Family photos and travel snapshots marked her early decades. Sophisticated photographers – including her husband, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) – were drawn to picture the enigmatic artist throughout her life. O’Keeffe’s approach to the medium was informed by past encounters, but principally guided by her own interests. O’Keeffe dedicated her life to expressing her unique perspective, whether through her clothing, home décor, paintings, or photographs. By the time she began her photographic practice in earnest in the mid-1950s, O’Keeffe brought her singular, fully formed identity and artistic vision to her camera work.

Unknown Photographer

Georgia O’Keeffe and Friends in a Boat

1908

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe Museum Purchase

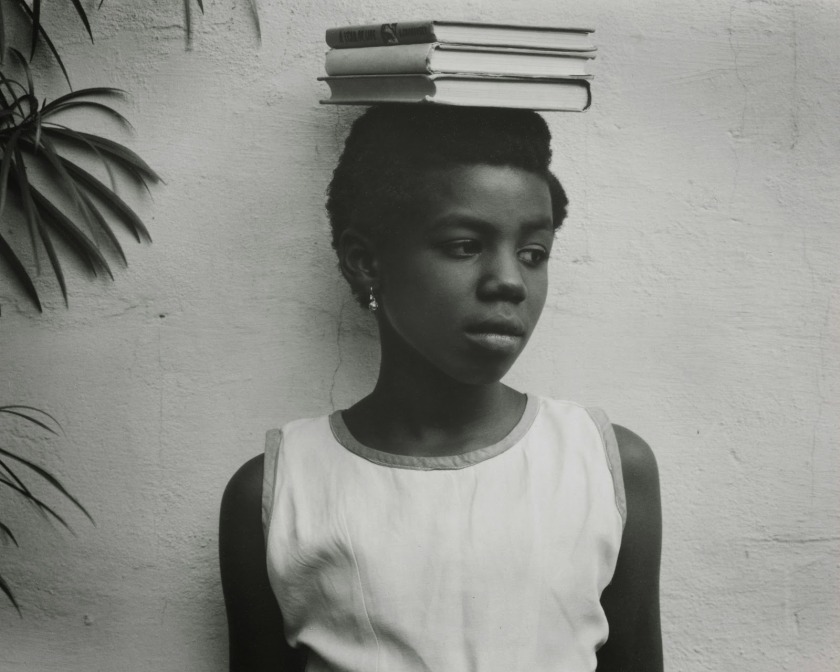

By 1890, the Eastman Company had sold millions of $1 Kodak Brownie cameras and photography was part of daily life for many people. Family photographs, studio portraits, and snapshots taken by O’Keeffe and her friends mark the artist’s earliest decades.

Born in Wisconsin, O’Keeffe studied and worked in Virginia, Illinois, New York, South Carolina, and Texas before she was 30. As she moved from place to place, she kept her close friendships in part by trading snapshots. Her friend Anita Pollitzer wrote, “Won’t you send me a Kodak picture… of you?” O’Keeffe responded with her own request, noting, “I want to know what you are looking like this fall.” O’Keeffe continued this practice when she began photographing with a clear artistic intention in the late 1950s, sending her photos to family and friends.

Large print label to the exhibition

Between 1907-1908, Georgia O’Keeffe attended the Art Students League in New York and studied with William Merritt Chase, F. Luis Mora, and Kenyon Cox. In June of 1908, she was awarded League’s Still Life Scholarship and attended the League’s Outdoor School at Lake George, New York.

O’Keeffe’s years as a young student were marked by the release of the first easy-to-use handheld cameras that made photography more widely available. This amateur photograph shows a 21-year-old O’Keeffe enjoying the day on a boat with her friends.

Text from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum Instagram website

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Stieglitz at Lake George

c. 1923

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe Museum

This double exposure – produced when two images are captured on the same frame of film – shows two views of the Stieglitz family property at Lake George, New York. In the vertical image, Alfred Stieglitz walks ahead on a path, while the horizontal image shows an expanse of the family’s summer residence. Though the double exposure was probably unintentional, O’Keeffe kept this photograph for more than 60 years, suggesting she found the image noteworthy even though it was the result of operator error. Her later photographic practice also demonstrated a sense of certainty in her own visual instincts over and above the rules of technique.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

The Black Place

c. 1970

Black-and-white Polaroid

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Georgia O’Keeffe Papers

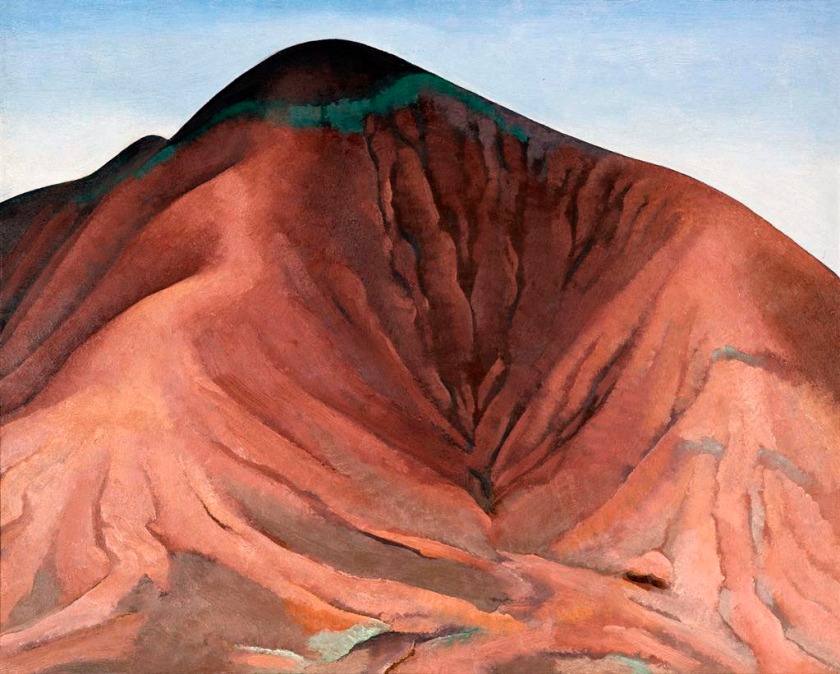

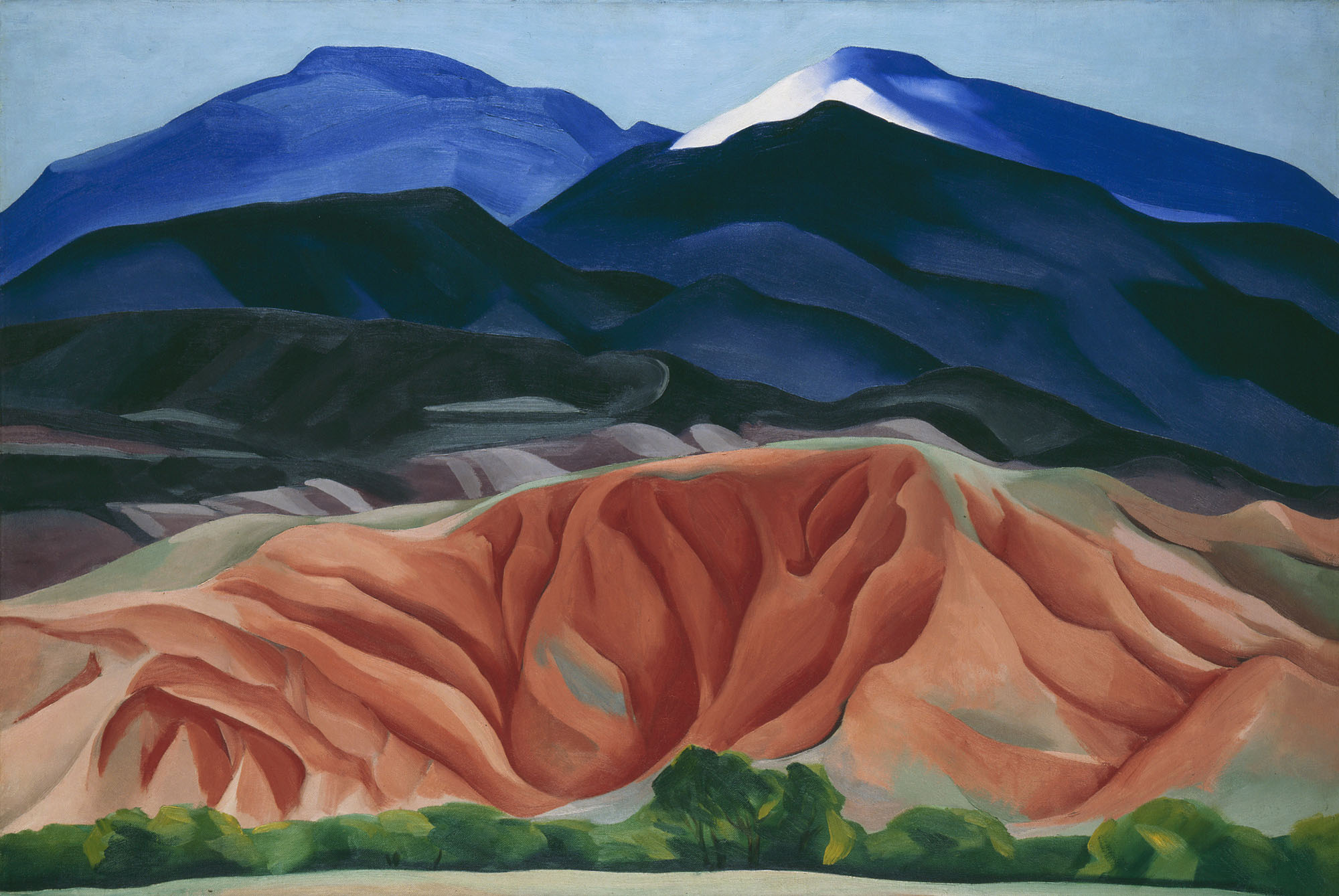

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Small Purple Hills

1934

Oil on panel

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Beginning in 1929, O’Keeffe spent part of almost every year in New Mexico until moving there permanently in 1949. Her beloved Southwestern landscape was a continual source of inspiration. “I never seem to get over my excitement in walking about here – I always find new places or see the old ones differently,” she wrote in 1943. O’Keeffe’s paintings, such as Small Purple Hills, conveyed her pleasure in the forms and colours of New Mexico. These same vistas would become the subjects of her photographs. In photography, O’Keeffe continued the formal exploration of those places that had ignited her artistic passions.

Large print label to the exhibition

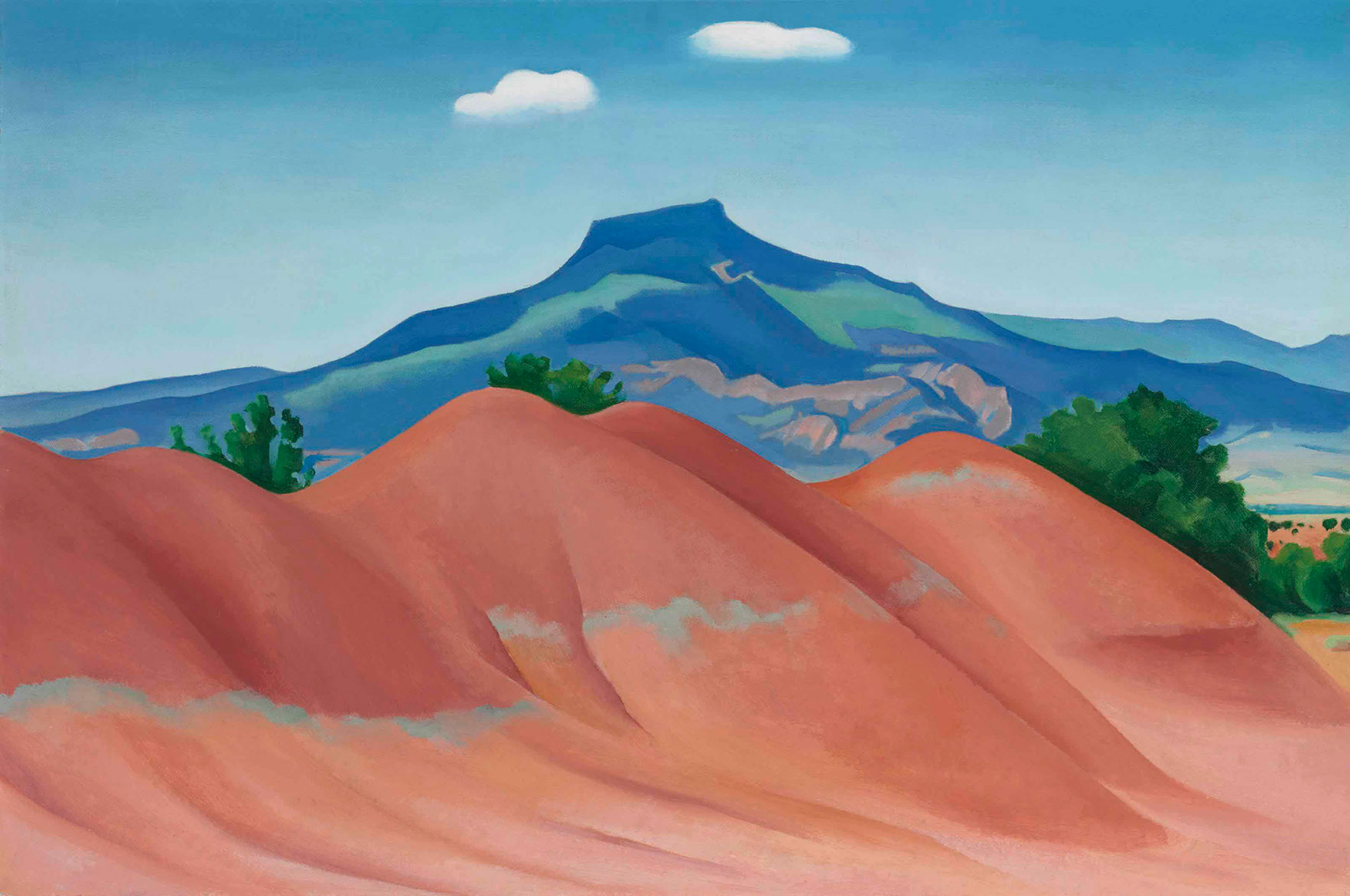

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Red Hill and White Shell

1938

Oil on canvas

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Gift of Isabel B. Wilson in memory of her mother, Alice Pratt Brown

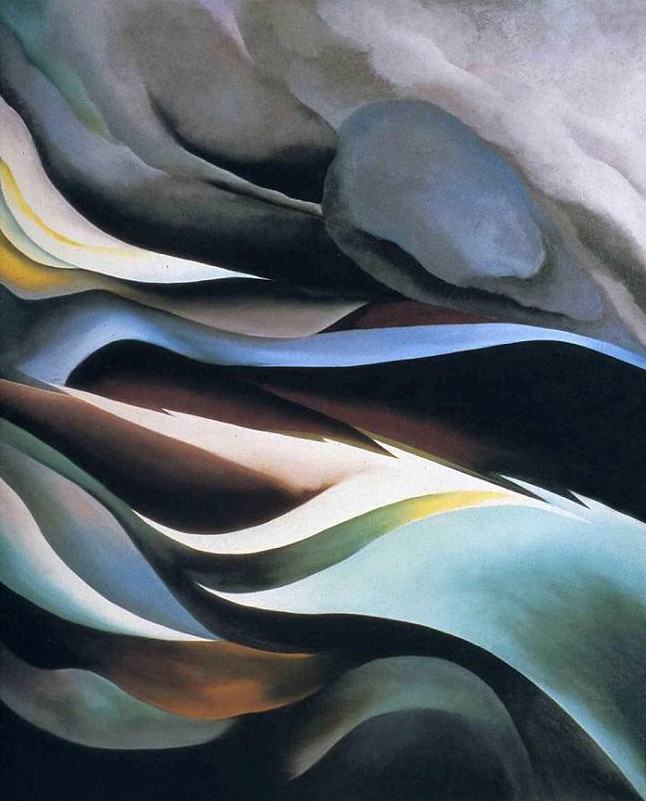

Red Hill and White Shell embodies O’Keeffe’s experiments with the fresh colours and dynamism of the natural world. Using the dual elements of a massive sandstone mesa and a small iridescent shell, the painting expresses attentiveness to environmental forms, both great and small. O’Keeffe’s careful abstractions in both painting and photography strove for a perfect union of aesthetic order and emotional expression. She wrote, “It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis that we get at the real meaning of things.”

Large print label to the exhibition

LIFE magazine (publisher)

“Georgia O’Keeffe Turns Dead Bones to Live Art”

February 14, 1938

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston: Courtesy of the Hirsch Library

During O’Keeffe’s lifetime, articles in newspapers and magazines made her face as recognisable to the public as her art, linking O’Keeffe, the woman, to the landscapes and objects she painted. This LIFE essay from 1938 juxtaposes the artist’s Horse’s Head with Pink Rose (1930) with three photos of her handling bones from New Mexico, presenting her art and her life as synonymous.

Large print label to the exhibition

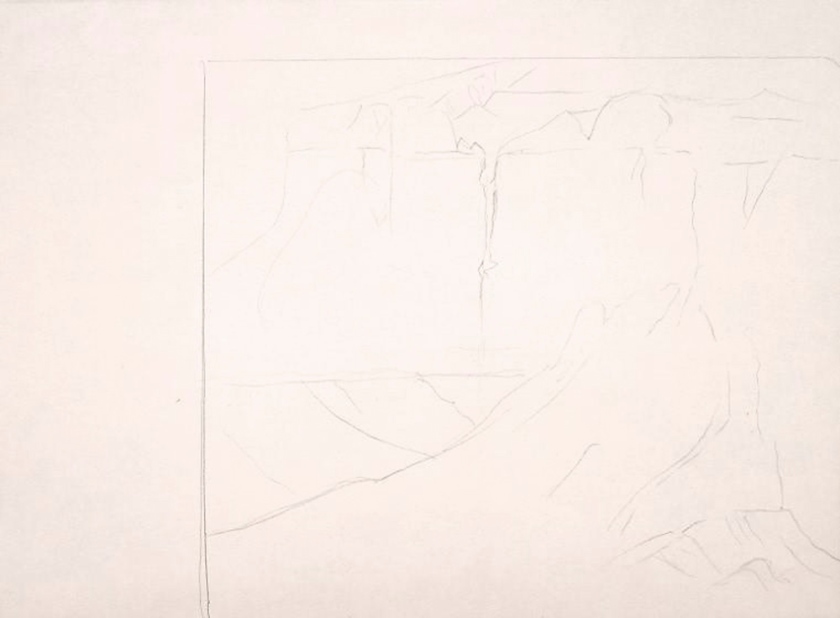

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Untitled (Ghost Ranch Cliffs)

About 1940

Graphite on paper

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Like her photographs, Ghost Ranch Cliffs reveals O’Keeffe’s restless experimentation with composition. Drawing upon lessons from her teacher, Arthur Wesley Dow, O’Keeffe would frame and reframe her landscape sketches, searching for the most expressive arrangement of forms. Accustomed to framing on paper, O’Keeffe’s transition to framing with a camera was a natural one.

Large print label to the exhibition

Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000)

Georgia O’Keeffe in Salita Door

July 1956, printed later

Inkjet print

Courtesy of the Todd Webb Archive

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Todd Webb in the Salita Door

July 1956, printed later

Inkjet print

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Museum

Purchases funded by the Director’s Accessions Endowment

In 1955 O’Keeffe’s interest in beginning a photographic practice was sparked by a visit from her friend, photographer Todd Webb. Over the next few summers, Webb visited O’Keeffe in New Mexico, and the pair photographed together, often trading his cameras back and forth. Here, the friends took turns posing for each other in O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú courtyard. “As you can see, you are a very good portrait photographer,” Webb wrote encouragingly to O’Keeffe. “I like the one of me in the doorway very much.”

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Seagram Building, New York

1958-1965

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Like her paintings of New York, many of O’Keeffe’s photographs of the city explore aspects of its monumentality and modernity. “One can’t paint New York as it is, but rather as it is felt,” she noted. O’Keeffe took this photo of the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s minimalist Seagram Building soon after it opened. Her dramatic, low camera angle presents the structure’s innovative vertical beams as endless lines stretching into the sky. Her view of the Chrysler Building [see first image in the posting] seems to grapple with a related experience, as a sense of quiet intimacy coexists with the vast scale and loftiness of the modern urban environment.

Large print label to the exhibition

Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000)

Georgia O’Keeffe Reviewing Photographs

1961, printed later

Inkjet print

Courtesy of the Todd Webb Archive

© Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA

Unlike most photographers, O’Keeffe was unconcerned with creating perfect photographic prints. More interested in the image than the final print, she used her instant Polaroid camera, printed her work at drugstores, or asked Todd Webb to create test prints or enlarged contact sheets of her pictures. These approaches did not align with the norms of contemporary art photography, yet they match O’Keeffe’s larger artistic practice.

Text from the Denver Art Museum website

Reframing

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Sugar Cane Fields and Clouds

March 1939

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In 1939, O’Keeffe accepted an invitation from an advertising company to go to Hawaii to produce paintings for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company. She kept these photographs for the remaining five decades of her life. The “Hawaii snaps,” as she referred to them, capture subject matter that is quintessentially O’Keeffe – dramatic landforms and perfect flower blooms.

Large print label to the exhibition

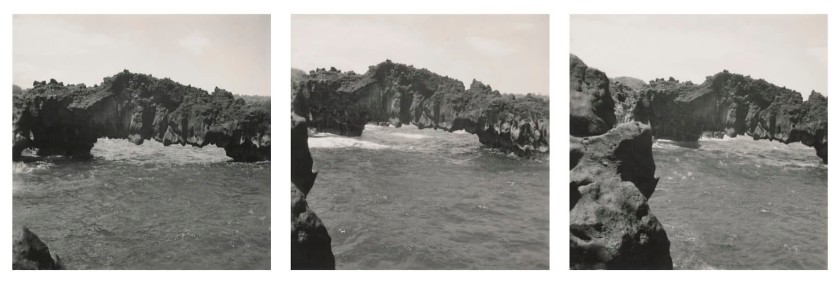

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Lava Arch, Wai’anapanapa State Park March

1939

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

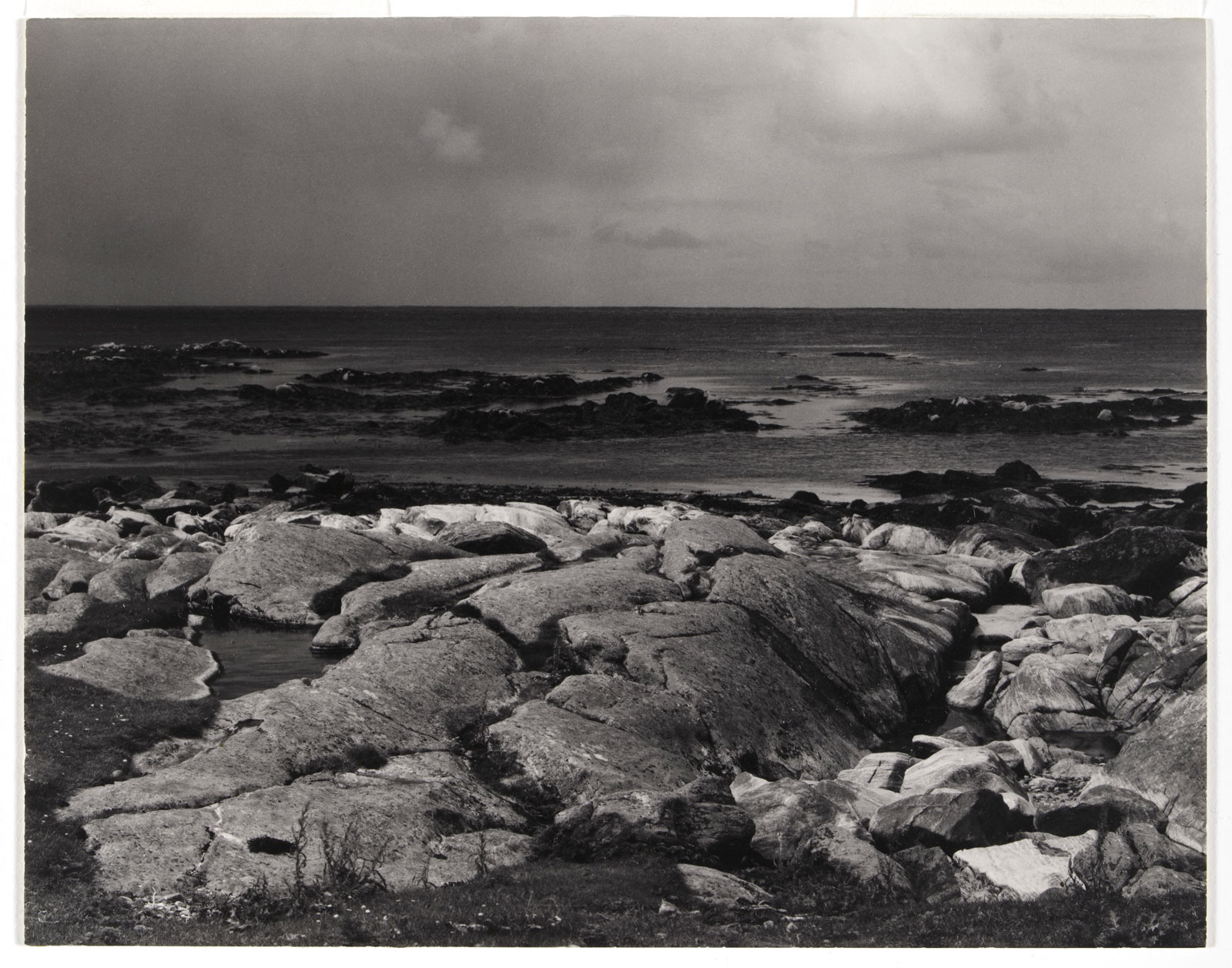

O’Keeffe made her first significant body of photographs on her 1939 trip to Hawaii. These photographs make clear that O’Keeffe had an intuitive interest in the photographic frame. Later, reframing would become a central tool in her sustained exploration of the medium.

Large print label to the exhibition

Though a handful of scattered snapshots made before 1939 can be attributed to O’Keeffe, her trip to Hawaii that year produced her first significant body of photographs. From this group of images, you can see O’Keeffe already framing and reframing the same landscape. These early photographs reveal that reframing was a method she intuitively brought to the medium and not one she learned from others nearly two decades later.

Text from the Denver Art Museum website

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Natural Stone Arch near Leho’ula Beach, ‘Aleamai

March 1939

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Here, O’Keeffe uses subtle reframing to seek an ideal expression of her experience of the place. She works with four boldly simplified elements – arch, water, sky, and coast – within a square picture area. In the top image, O’Keeffe uses the shoreline to bisect the middle of the picture plane, resulting in a composition that feels natural and balanced. In the bottom image, she has raised the shoreline within the frame, compressing the ocean, arch, and sky. How does your experience of the picture change because of her compositional choices?

Large print label to the exhibition

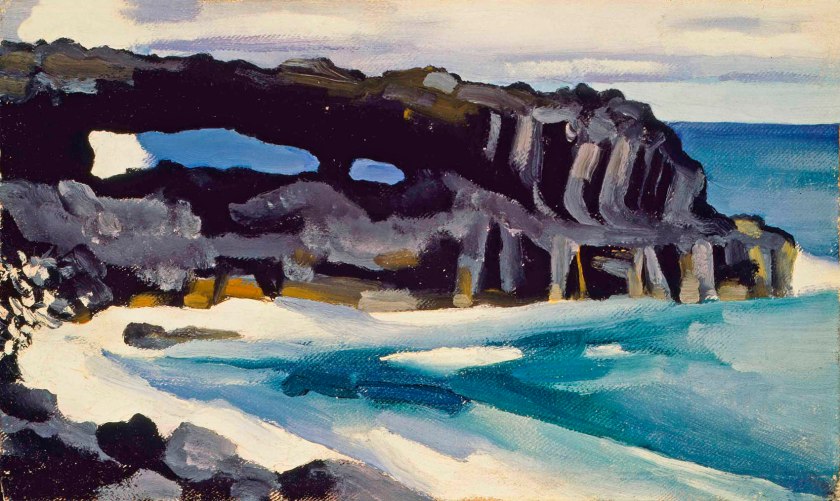

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast No. 2

1939

Oil paint on canvas

Honolulu Museum of Art: Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 1994, 7893.1. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

O’Keeffe’s small oil painting Black Lava Bridge, Hana Coast No. 2 depicts the same coastline as her nearby photographs. Compared to the square pictures, the painting’s wider, lateral format emphasises the massy character of the rock formation itself, drawing our attention to its horizontality and relationship with the water.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Wai’anapanapa Black Sand Beach

March 1939

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In many of her letters home from Maui, O’Keeffe described her desire to photograph the island’s landscape and vistas. “The black sands of Hawaii – have something of a photograph about them,” she wrote. Perhaps the artist was responding to the chromatic simplicity of lacy white sea foam on black sand. Yet, there is also a notable relationship between O’Keeffe’s attraction to reframing and the constantly changing, expressive compositions created by nature as the edges of waves skim over the beach. Here, she seems to explore exactly that visual potential.

Large print label to the exhibition

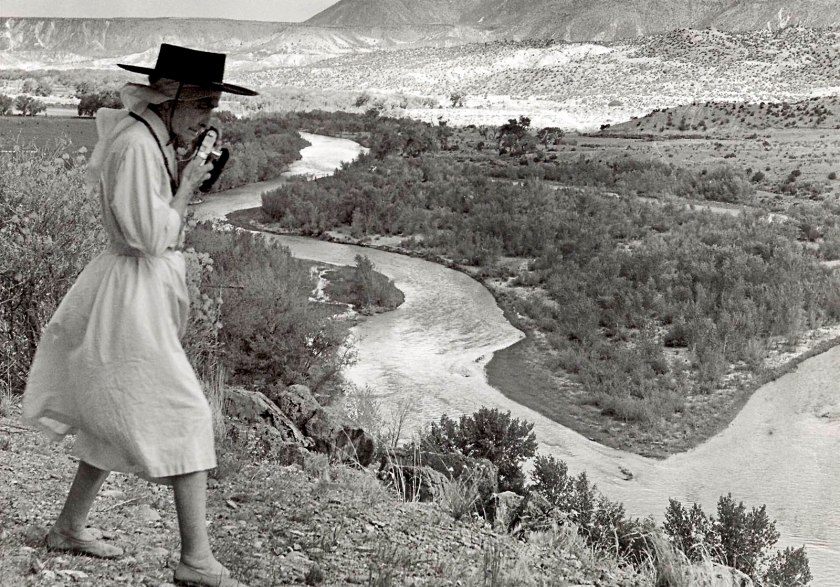

Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000)

Georgia O’Keeffe with Camera

1959, printed later

Inkjet print

Todd Webb Archive

© Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA

In 1940, O’Keeffe purchased a cottage on Ghost Ranch, northwest of Abiquiú, New Mexico. Ghost Ranch would become her summer and fall home – a place of solitude where she concentrated on painting. In 1945 she purchased a home in Abiquiú, where she would spend the winter and spring seasons. She moved to the Southwest permanently in 1949. In the mid-1950s, O’Keeffe took up the camera in earnest to continue her relentless search for ideal artistic expression. She made most of her photographs on or near her Abiquiú property.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Garage Vigas and Studio Door

July 1956

Gelatin silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous Gift, 1977

© 2022 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Studio Door

July 1956

Gelatin silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous Gift, 1977

© 2022 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Abiquiú studio door is a subject unique to O’Keeffe’s photography. In this series of photographs, she explored ways to visually compress the subject into two dimensions using the arrangement of forms within the frame. Photographing her studio door from a vantage point inside her garage (which is located across an open courtyard), she positioned her camera to include more or less of the garage ceiling. The linear pattern of vigas (round roof beams) and latillas (ceiling slats) change the way space seems to work in the picture, moving from three-dimensional depth to increasingly flattened planes of form.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Salita Door, Patio

1956-1957

Gelatin silver print

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Lane Collection

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Image © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

“As I climbed and walked about in the ruin, I found a patio with a very pretty well house and bucket to draw up water. It was a good-sized patio with a long wall with a door on one side. That wall with a door in it was something I had to have.”

~ Georgia O’Keeffe

On many occasions, O’Keeffe claimed that the dark salita door – the door leading into her salita, or sitting room – was the reason she purchased her Abiquiú home. She depicted this door in her work with notable frequency, producing 23 paintings and drawings from 1946 until 1960 and numerous photographs beginning in 1956. “It’s a curse – the way I feel I must continually go on with that door,” she noted.

Text from the Denver Art Museum website

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Salita Door, Patio

1956-1957

Gelatin silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Anonymous Gift, 1977

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

On many occasions, O’Keeffe claimed that the salita door was the reason she purchased her Abiquiú property. This interior door separates the central patio from the salita, or sitting room. O’Keeffe used the salita as a workroom and storage space for her paintings, making the door a physical and metaphorical link between her home and her art. “I’m always trying to paint that door – I never quite get it,” O’Keeffe wrote. Her 23 paintings and drawings of the door were followed by a series of photographs.

Large print label to the exhibition

This door separates the central patio from the salita, or sitting room, which O’Keeffe used as a workroom and storage space for her paintings. The door can be seen as a physical and metaphorical link between her home and her art. “I’m always trying to paint that door – I never quite get it,” O’Keeffe wrote.

Text from the Denver Art Museum website

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Patio and Zaguan

1956-1957

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

The multiple doors and windows of the central patio in O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú home lent themselves to experiments in reframing. By moving the position and orientation of her camera, the artist could explore a huge variety of precise compositions in her own domestic space. Here, she turned toward the entryway of the zaguan – a central passage between the interior courtyard and the exterior of the house. O’Keeffe’s reflection, sometimes visible in a window at the left of the frame, captures the artist carefully framing the scene.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Salita Door

1956-1958

Gelatin silver print

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Anonymous Gift

One of O’Keeffe’s first photographs of her Abiquiú, New Mexico home was a carefully and beautifully rendered image of the salita door in her courtyard. In the picture, the dark rectangle of the door breaks the adobe wall. A long, sleek shadow cuts diagonally through the frame, and a silvery sage bush fills the bottom left corner.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Ladder against Studio Wall in Snow

1959-1960

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.M.

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

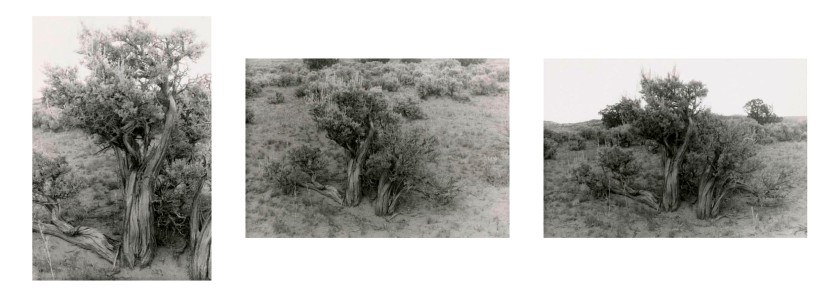

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Big Sage (Artemisia tridentata)

Big Sage (Artemisia tridentata)

Big Sage (Artemisia tridentata)

1957

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In 1957, O’Keeffe produced a group of eight photographs of big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) near Barranca, New Mexico. She pictured the three, tightly grouped shrubs at close range, in contrast to the rolling horizon, or framed against the packed ground. Moving her camera with each capture, she altered the arrangement of the forms and changed the overall organisation of the scene. The resulting images are radically different, though each contains the same basic elements.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Big Sage (Artemisia tridentata)

1957

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

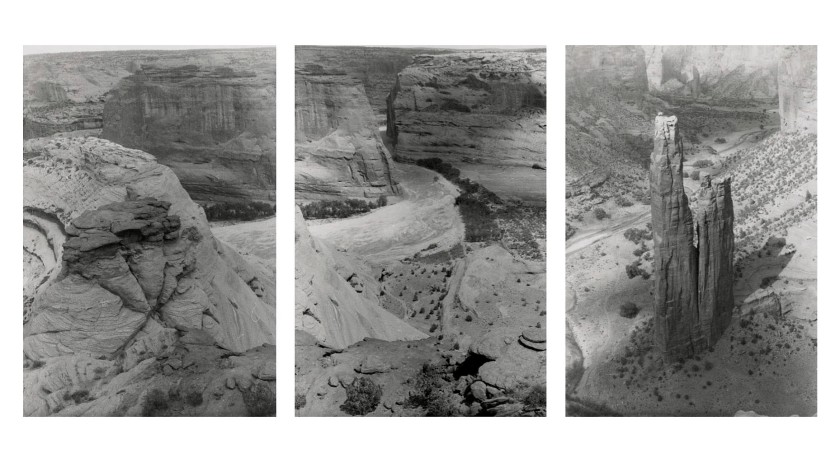

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

White House Overlook

White House Overlook

Spider Rock

July 1957

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

While O’Keeffe organised most of her photographic compositions within single film frames, a few noteworthy examples demonstrate her interest in testing that limitation. In July 1957, O’Keeffe visited Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, making three images at White House Overlook. Together, the images form a panorama, moving from the starburst form of a crag, through the winding canyon below, to the tall sandstone spire of Spider Rock. O’Keeffe’s choice to use vertical frames to capture a sweeping horizontal vista is distinctive. What might have interested her about this approach?

Large print label to the exhibition

In July 1957, O’Keeffe visited Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, and produced three images at White House Overlook. Together, the three images form a panorama, moving from the starburst form of a crag, through the winding canyon below, to the tall sandstone spire of Spider Rock. O’Keeffe’s choice to capture a sweeping, horizontal vista through three vertical photos is another characteristic of her photography.

Text from the Denver Art Museum website

Light

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Dark Rocks

1938

Oil on canvas

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Gift of Patricia Barrett Carter

The painting Dark Rocks exemplifies O’Keeffe’s talent for abstracting natural forms. Her rendering of stacked rocks includes precisely placed areas of highlight and shadow. These formal elements result in an ambiguous relationship between positive and negative space. What is solid and what is mere shadow? This play of depth and weight is also evident in O’Keeffe’s photographs of her chow chows, which she rendered in her art as abstract round forms – much like these rocks. O’Keeffe often used light and dark to explore the qualities of form, dimension, and depth.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Bo II (Bo-Bo)

1960-1961

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

In these photographs, O’Keeffe’s chow Bo II (also known as Bo-Bo) curls up on sun-bleached tree trunks outside the artist’s studio door. The dog’s body is a dark, weighty form juxtaposed in various ways against the light cylindrical forms of the tree trunks. At the same time, the shadow of a ladder suggests the dog’s form could read as a shadow – a negative space without depth or weight.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Untitled (Dog)

1951

Graphite on paper

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Gift of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

O’Keeffe owned eight chow chows – seven blue and one red – over the course of more than 20 years. She received her first two, Bo and Chia, as Christmas presents in 1951. O’Keeffe often described her dogs in formal terms. She wrote to her sister Claudia, “I have two new chow puppies – half grown… not quite blue and against the half snow has a frosty colour – very pretty.” The artist appreciated the dogs’ dark fur in contrast to the bright New Mexico environment and their ambiguous shape when they lay curled on the ground.

Large print label to the exhibition

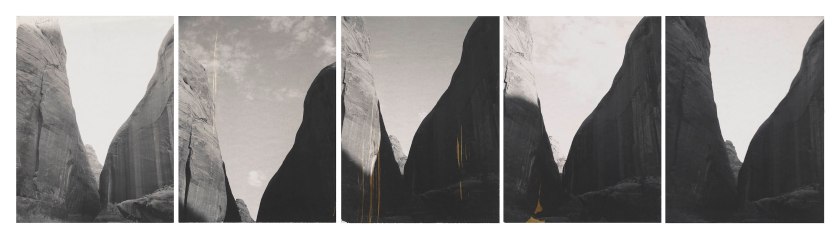

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Forbidding Canyon, Glen Canyon

September 1964

Black-and-white Polaroids

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

During her second trip to Glen Canyon in Utah and Arizona, O’Keeffe and her group camped for four nights at a picturesque location near Forbidding Canyon. There, the monumental form of two cliffs meeting in a “V” shape provided a spectacular view each morning. The strong morning light turned one cliff into a bright white form, while the other, cast in shade, became a dark mass. As the sun moved across the morning sky, the shadows quickly shifted. O’Keeffe’s Polaroids tracked the changing proportions of dark and light in this dynamic scene, much like she had looked at the surf on the black sands of Maui 25 years earlier.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

In the Patio VIII

1950

Oil on canvas

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Gift of the Burnett Foundation and the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In the Patio VIII depicts the interior courtyard of O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú home. In the painting, she uses a bold band of a shadow to pick out the geometry of the space. The dark angular shape cuts across the lower half of the painting, differentiating the planes of walls and ground. It is as if the shadow lends the space a three-dimensional nature. For O’Keeffe, shadows were entities that could define a composition.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

North Patio Corridor

1956-1957

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

The door, wall, and sagebrush at the north corner of O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú patio presented the artist with an eye-catching array of lines, shadows, and shapes. Characteristically, she used these features of her environment relentlessly to search for the perfect arrangement of forms.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Ladder against Studio Wall with White Bowl

Ladder against Studio Wall with Black Chow (Bo-Bo)

1959-1960

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

O’Keeffe produced these two photographs in rapid succession. Often, she rendered light as a bright white form and shadow as a weighty dark object. By placing a white bowl to the left of the ladder in one frame and one of her pet dogs to the right in the other, O’Keeffe created startlingly different compositions through one minor change.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Ladder against Studio Wall with White Bowl

1959-1960

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Skull, Ghost Ranch

1961-1972

Chromogenic print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.M.

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

O’Keeffe shared her photographs with family and friends, often mailing prints with handwritten notes on the back. For the artist, these photographs provided her friends with glimpses of her home and artistic world. Skull, Ghost Ranch was printed multiple times. On the verso of one print, O’Keeffe hand wrote to an unknown acquaintance, “Another present this is. It is beside the Studio door. Pretty isn’t it!”

“It never occurs to me that [skulls] have anything to do with death. They are very lively,” O’Keeffe noted. “I have enjoyed them very much in relation to the sky.” For O’Keeffe, the artistry in rendering skulls lay in juxtaposition. The harmonious relation of the skull’s form to other elements resulted in an artistic play of light and shadow and positive and negative space that sustained her interest.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Goat’s Head

1957

Oil on canvas

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

Gift of the Estate of Tom Slick

Skulls were a favourite subject for O’Keeffe, appearing in her paintings from the 1930s until the 1960s and in her photographs until the 1970s. These bones, however, were never depicted in isolation. O’Keeffe’s skulls were always juxtaposed with other elements: cloth backgrounds, desert landscapes, architectural forms, and blue skies. In Goat’s Head, O’Keeffe presents the skull against alternating planes of light and shadow, suggesting a retreating desert landscape. The careful cropping of the composition, like a photograph, unites the forms of the skull and landscape and encourages a comparison of bone and background.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Roofless Room

1959-1960

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Roofless Room

1959-1960

Gelatin silver print

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Streaked by morning shadows, O’Keeffe’s photographs of her “roofless room” at Abiquiú are stunning studies of the dimensional quality of shadows. As the sun’s position changed throughout the day, the shadows cast by the latillas (ceiling slats) crept down the walls and across the bare floor, reframing the scene. In each image, O’Keeffe uses these dramatic shadows to articulate the planes and angles of the room.

Large print label to the exhibition

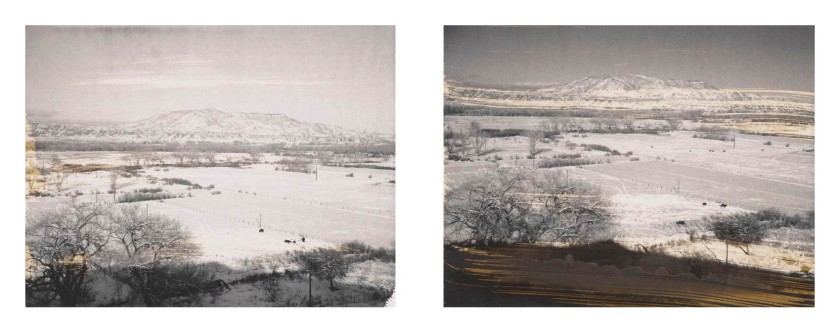

Seasons

In the Southwest, each season brings subtle and dramatic shifts in the quality of sunlight and the appearance of the landscape. While full, leafy trees cast deep shadows in the summer, the same place offers bare branches and evenly lit, snowy ground in the low sun of winter. O’Keeffe photographed her environment in all seasons, allowing the change in nature to act as an inherent formal characteristic in her artwork.

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Road from Abiquiú

1964-1968

Black-and-white Polaroids

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

“The valley is wide and flat with a row of bare trees on the far side – masking the river that I do not see because of them – then a very fine long mountain rises beyond. It is all frosty this morning – The sun this time of year hits the mountain first – then the trees – with a faint touch of pink – then spreads slowly across the valley as sun light.” O’Keeffe’s sensitivity to the seasonal change outside her bedroom windows is evident in her multiple photographs of those views, which capture the landscape in winter, spring, summer, and fall.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Road out Bedroom Window

Road out Bedroom Window

Probably 1957

Gelatin silver prints

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Anonymous Gift, 1977

Several extant photographs of the mesa and road outside O’Keeffe’s east window track the view at different times of the year. In addition to overtly reframing the scene, the artist allowed nature’s changes to alter the relationships of form and light within the composition. The strong summer sun cast hard shadows onto the silvery road in one photograph, while in another, the diffuse light of spring highlights the new growth of the thin foliage.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Road Past the View

1964

Oil on canvas

Collection of Carl & Marilynn Thoma

In her 1976 Viking Press book, titled Georgia O’Keeffe, the artist included the following text next to the seductive painting Road Past the View: “The road fascinates me with its ups and downs and finally its wide sweep as it speeds toward the wall of my hilltop to go past me. I had made two or three snaps of it with a camera.” It is notable that this anecdote about photography was included in a book with limited text covering an impressive 60-year career. O’Keeffe was sure to write photography into her story.

Large print label to the exhibition

Todd Webb (American, 1905-2000)

Georgia O’Keeffe Photographing the Chama River

1961, printed later

Inkjet print

Courtesy of the Todd Webb Archive

In 1957 Todd Webb wrote to O’Keeffe, “Will we stand on the bridge and watch the Chama in flood?” The pair often visited this spot, located between O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch property and her main house in Abiquiú. In these three frames, Webb captured O’Keeffe as she moved along the rise, reframing the river view with her camera.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe and Todd Webb met in 1946. That year she was the first woman to be honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Webb, a photographer and protégé of the artist’s husband Alfred Stieglitz, documented the exhibition. That same year, Webb’s urban scenes were shown at the Museum of the City of New York, curated by influential photographic historian Beaumont Newhall. Despite these professional accomplishments, it was also a time of loss as Stieglitz died in July of that year. They went on to have a long friendship and Webb visited O’Keeffe in New Mexico multiple times. Their friendship is documented in a series of photographs on exhibit alongside works by O’Keeffe.

In 1961, O’Keeffe traveled with Lucille and Todd Webb along with a dozen other friends on a ten-day raft trip down the Colorado River to Glen Canyon, Utah. After the trip, Webb presented O’Keeffe with an album of photographs from their shared experience. With his camera focused on the artist, he also framed the extraordinary beauty of the canyons accessible only on the water…

In a 1981 letter to the photographer, O’Keeffe remembered a day in 1946 which solidified their friendship. She was packing artwork for her MoMA exhibition. “I had the world to myself to pack up thirty or forty paintings to go. It looked like quite a formidable task… When you saw the problem you started right in to help me. I may have seen you before, talking with Stieglitz, but I never spoke with you. However, I will never forget your helping me for hours – a person, almost a stranger – till we had everything packed and ready to go.”

Anonymous. “Todd Webb,” on the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum website 2016 [Online] Cited 07/04/2023

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Chama River

1957-1963

Gelatin silver prints

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

Located between O’Keeffe’s Abiquiú home and Ghost Ranch, this south-facing elevation overlooks the Chama River as it makes a tight bend. O’Keeffe photographed the view in a variety of seasons, capturing the changing depth of the rushing water, the density of foliage, and the deepness of shadows throughout the year.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

Jimsonweed (Datura stramonium)

1964-1968

Black-and-white Polaroid

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

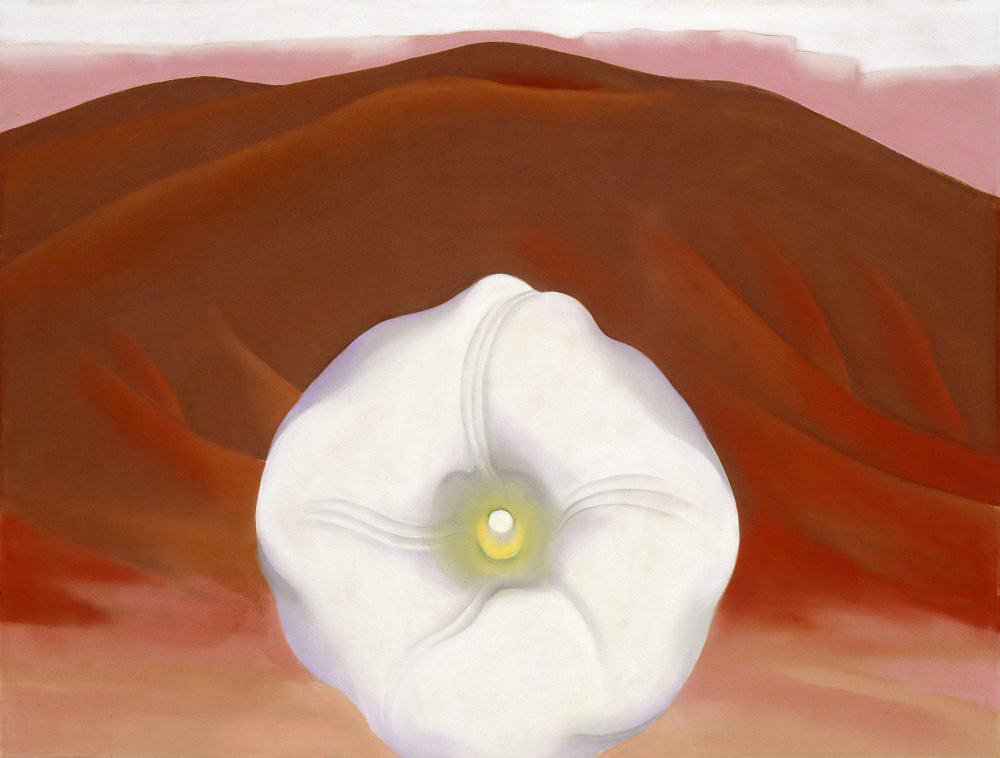

O’Keeffe’s photographs of jimsonweed flowers exemplify her interest in seasonal change. The trumpet-like flowers of the jimsonweed began blooming around her home in late summer and continued through the first frost. The flowers obey both the cycle of the seasons and a shorter daily cycle, opening in the afternoon and closing with the rising sun the next day.

O’Keeffe’s many photographs of jimsonweed present the bright white flower in contrast to its dark surrounding leaves. Individually or in groups of blooms, jimsonweed signals O’Keeffe’s ongoing fascination with nature’s transformation in all its forms.

“Well – I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t,” O’Keeffe scolded. For the artist, her renderings of flowers were about detail, light and shade, and formal juxtaposition. Though many critics read other meanings into these works, O’Keeffe maintained that they signified only the artistic potential of flowers. Here, she distills their potential not with pencil or paint, but with her camera.

Large print label to the exhibition

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887-1986)

White Flower

1929

Oil on canvas

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection

Georgia O’Keeffe is perhaps best known for her paintings of flowers. Their magnified structures fill the canvas and absorb the viewer in her unique vision of nature. She magnified her painted flowers so that people would “be surprised into taking time to look at it.” O’Keeffe rendered her blooms at their peak, capturing this fleeting view of nature in enveloping detail.

Large print label to the exhibition

Cincinnati Art Museum

953 Eden Park Drive

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Phone: (513) 721-ARTS (2787)

Opening hours:

Open Tuesday – Sunday 11am – 5pm

Closed Mondays

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918 Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) 'Untitled [O'Keeffe with sketchpad and watercolors]' 1918](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/georgia_okeeffe_by_stieglitz_1918-web.jpg)

![Harry Callahan (American, 1912-1999) [Detroit] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/harry-callahan-detroit.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.