Exhibition dates: 3rd November 2015 – 20th March 2016

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of Young Girl with a Guitar

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

1/6 plate

Open: 9.2 x 15.2cm (3 5/8 x 6 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

The last in my trilogy of postings on 19th century photography features a rather uninspiring collection of daguerreotypes. Perhaps there were better ones in the exhibition.

Of most interest to me are two:

Nude Woman in Photographer’s Studio (c. 1850, below) with its almost van Gogh-esque perspective of the figure, chair and rug. The image is also notable for the daguerreotypes of men who stare down on the women from the wall behind: the objectification of the male gaze – of the photographer and of the observers. This daguerreotype also reminds me of the later haunting photographs by E. J. Bellocq (1873-1949) of the prostitutes of Storyville, New Orleans.

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey’s ghostly, evocative Facade and North Colonnade of the Parthenon on the Acropolis, Athens (1842, below). Can you imagine being shown this full plate, I repeat, full plate daguerreotype of one of the wonders of Ancient Greece just 3 years after the public announcement of the invention of photography. You would have never seen many, if any, images of foreign places in your life before, and that moment of initiation into the magic arts of photography would have taken on the deepest significance. Even now, the effect of this plate on the imagination and consciousness of the viewer is outstanding.

.

The rest of the daguerreotypes in this posting are more prosaic: vaguely interesting still life vanitas or portrait social documentation. If you were not told that these were images of a president of the United States, the inventor of the daguerreotype, or the writer Edgar Allen Poe they could be any “Portrait of a man” or “Portrait of a woman”. It’s amazing how even at this early stage of photography the codification of the image, its semiotic language if you like, was intimately tied up with the caption and text that accompanied it. Of course, unless we know that it’s called the Eiffel Tower then a photograph of the object without that knowledge would mean very little; but as soon as that title is present in collective consciousness, then anywhere an image of that structure is found, it is already known as such.

Now there’s a good idea for an exhibition: the influence of the title on the interpretation of the photographic image. ‘(Un)titled images’ anyone?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

James Maguire (American, 1816-1851)

[Portrait of Zachary Taylor]

1847

Daguerreotype

1/4 plate

Image: 7.9 x 5.4cm (3 1/8 x 2 1/8 in.)

Mat: 12.7 x 10.8cm (5 x 4 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

James Maguire (American, 1816-1851) Daguerreotypist, dealer in daguerreian supplies; active Tuscaloosa, Ala., before 1842; New Orleans 1842-50; Natchez, Miss., 184; Vicksburg, Miss., 1842; Plaquemine, La., 1842; Baton rouge, La., 1842; Belfast, Ireland, 1844; London, England, 1844; Paris, France, 1844.

According to his obituary, James Maguire was born in Belfast, Ireland, around 1815. By early 1842 he had learned the daguerreian art from Frederick A. P. Barnard and Dr. William H. Harrington in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Maguire was one of the earliest daguerreians to establish a permanent gallery in New Orleans. In that city on January 28, 1842 he advertised that he had opened a portrait gallery at 31 Canal Street, upstairs, where he would “remind a short time.” …

Maguire’s New orleans gallery flourished during the Mexican War, when the city enjoyed a boom as a key shipping centre and rendezvous for troops bound for Mexico…

When General Zachary Taylor passed through New Orleans in late 1847 on his triumphant return from the Mexican War, he favoured Acquire by sitting for his portrait. The Daily Picayune noted not January 11, 1848, that Macquire’s portrait was ‘the best and most striking likeness of ‘Old Zach’ we have yet seen of him anywhere.”

Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn. Pioneer Photographers from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide: A Biographical Dictionary 1839-1865. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005, pp. 411-412.

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States, serving from March 1849 until his death in July 1850. Before his presidency, Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to the rank of major general.

Taylor’s status as a national hero as a result of his victories in the Mexican-American War won him election to the White House despite his vague political beliefs. His top priority as president was preserving the Union, but he died seventeen months into his term, before making any progress on the status of slavery, which had been inflaming tensions in Congress.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Unknown maker (American)

Nude Woman in Photographer’s Studio

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

1/6 plate

Image: 9.5 x 7.6cm (3 3/4 x 3 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Unknown maker (American)

Nude Woman in Photographer’s Studio (detail)

c. 1850

Daguerreotype

1/6 plate

Image: 9.5 x 7.6cm (3 3/4 x 3 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe

late May – early June 1849

Daguerreotype

1/2 plate

Image: 12.2 x 8.9cm (4 13/16 x 3 1/2 in.)

Mat (and overmat): 15.6 x 12.7cm (6 1/8 x 5 in.)

Object (whole): 17.9 x 14.9cm (7 1/16 x 5 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of a Nurse and a Child

c. 1850

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/6 plate

Image: 6.2 x 4.8cm (2 7/16 x 1 7/8 in.)

Mat: 8.3 x 7.1cm (3 1/4 x 2 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Charles Richard Meade (American, 1826-1858)

Portrait of Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre

1848

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/2 plate

Image: 15.7 x 11.5cm (6 3/16 x 4 1/2 in.)

Mat: 16 x 12cm (6 5/16 x 4 13/16 in.)

Object (whole): 22.1 x 17.8cm (8 11/16 x 7 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Louis Daguerre (1787 – 10 July 1851) was born in Cormeilles-en-Parisis, Val-d’Oise, France. He was apprenticed in architecture, theatre design, and panoramic painting to Pierre Prévost, the first French panorama painter. Exceedingly adept at his skill of theatrical illusion, he became a celebrated designer for the theatre, and later came to invent the diorama, which opened in Paris in July 1822.

In 1829, Daguerre partnered with Nicéphore Niépce, an inventor who had produced the world’s first heliograph in 1822 and the first permanent camera photograph four years later. Niépce died suddenly in 1833, but Daguerre continued experimenting, and evolved the process which would subsequently be known as the daguerreotype. After efforts to interest private investors proved fruitless, Daguerre went public with his invention in 1839. At a joint meeting of the French Academy of Sciences and the Académie des Beaux Artson 7 January of that year, the invention was announced and described in general terms, but all specific details were withheld. Under assurances of strict confidentiality, Daguerre explained and demonstrated the process only to the Academy’s perpetual secretary François Arago, who proved to be an invaluable advocate. Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre’s studio. The images were enthusiastically praised as nearly miraculous, and news of the daguerreotype quickly spread. Arrangements were made for Daguerre’s rights to be acquired by the French Government in exchange for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce’s son Isidore; then, on 19 August 1839, the French Government presented the invention as a gift from France “free to the world”, and complete working instructions were published. In 1839, he was elected to the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician.

Daguerre died on 10 July 1851 in Bry-sur-Marne, 12 km (7 mi) from Paris. A monument marks his grave there.

Text from the Wikipedia website

James P. Weston (American, active South America about 1849 and New York 1851-1852 and 1855 -1857)

[Portrait of an Asian Man in Top Hat]

c. 1856

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/9 plate

Image: 5.4 x 4.3cm (2 1/8 x 1 11/16 in.)

Mat: 6.4 x 5.1cm (2 1/2 x 2 in.)

Open: 5.1 x 10.8cm (2 x 4 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

A “mirror with a memory,” a daguerreotype is a direct-positive photographic image fixed on a silver-coated metal plate. The earliest form of photography, this revolutionary invention was announced to the public in 1839. In our present image-saturated age, it is difficult to imagine a time before the ability to record the world in the blink of an eye and the touch of a fingertip. This exhibition, drawn from the Getty Museum’s permanent collection with loans from two private collections, presents unique reflections of people, places, and events during the first two decades of the medium.

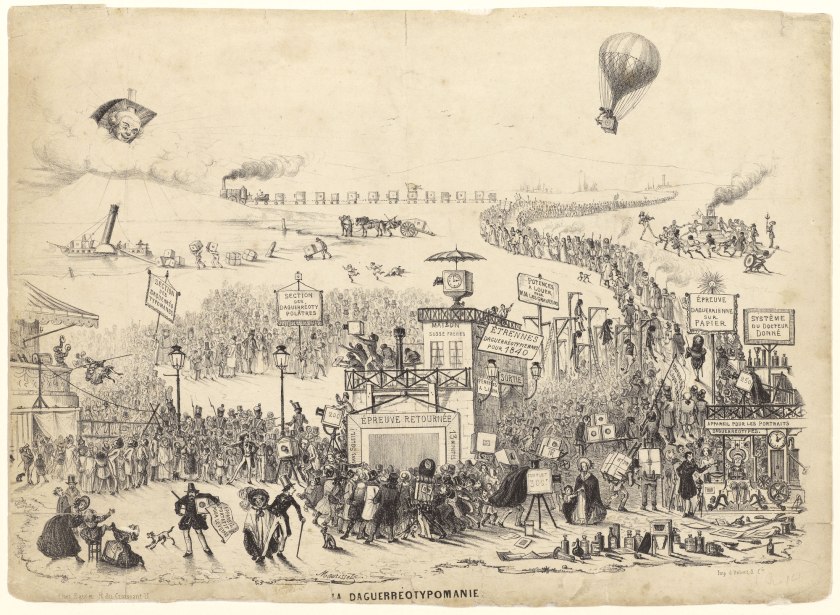

Popularly described as “a mirror with a memory,” the daguerreotype was the first form of photography to be announced to the world in 1839 and immediately captured the imagination of the public. The “Daguerreotypomania” that followed may seem surprising today, as photographs have become an omnipresent part of contemporary life. In Focus: Daguerreotypes, on view from November 3, 2015 – March 20, 2016 at the Getty Center, offers the photography enthusiast and the general visitor alike a unique opportunity to view rare and beautiful examples of this early photographic process. The works in the exhibition are drawn from the Getty Museum’s exceptional collection of more than two thousand daguerreotypes alongside loans from the outstanding private collections of musician Graham Nash and collector Paul Berg.

“Today, photographs can be taken, edited, and deleted within seconds and are the principal record of our everyday lives,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “It takes a leap of the imagination to appreciate what they represented to the pioneer inventors and to the public of the day. This exhibition explores how these first captured images – fragile, one-of-a-kind works – were treasured, not only by those who were just discovering the possibilities of the medium, but by those being photographed as well.”

By the mid-1840s, exposure times and costs had decreased markedly and, as a result, daguerreotypes became more accessible to a broader audience. Over the years, attempts were made to enhance the capabilities of the daguerreotype. To make up for the deficiency of colour, many portrait daguerreotypists employed former miniature painters to hand-paint each plate; an example of which is Portrait of a Woman with a Mandolin (1860), where light specks of colour enhance the ornamentation on the costume. Daguerreotypes were also nearly impossible to reproduce, though some attempts were made, including making the daguerreotype plate into a printing plate. Examples of this process will be on view in the exhibition.

Inside the Portrait Studio

Daguerreotype studios were plentiful by the mid-19th century, and each studio developed novel ways to create distinctive and personal images for its customers. Confined to a well-lit indoor or outdoor location, many daguerreotypists would stage everyday scenes that might include painted backdrops of domestic interiors and subjects posing as if in conversation or seated at tables with everyday props. As it was extremely difficult to capture a smiling face without blurring the features, most sitters wore somber expressions. An unusual exception on view in the exhibition is Portrait of a Father and Smiling Child (about 1855).

Customers remarked on the incredible fidelity of the silver image and praised it as a means of preserving a loved one’s presence. Some family members – often children – passed away before they could pose for the camera, and their likenesses were preserved in post-mortem portraits, as in Carl Durheim’s (Swiss, 1810-1890) Postmortem Portrait of a Child (about 1852), which creates the illusion of quiet slumber rather than death.

Prominent and well-known members of society also had their daguerreotype portraits taken, which made their likenesses more accessible to the public than ever before. “The exhibition will include daguerreotypes of the Duke of Wellington, Edgar Allen Poe, and Queen Kalama of Hawaii,” says Karen Hellman, assistant curator of photographs in the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Department of Photographs and curator of the exhibition. “Because of the unique direct positive process, we find ourselves face to face with these historical figures.”

Outside the Portrait Studio

Some of the first subjects for the daguerreotype process were ancient monuments and far-off cityscapes that were previously accessible only to a small, educated elite. Some photographers traveled long distances to capture these remote locales; the exhibition includes images of the Parthenon in Athens, the Pantheon in Rome, and the Temple of Seti I in Egypt. Others trained their lenses closer to home, focusing on vernacular architecture or such structures of national significance as John Plumbe Jr.’s (American, born Wales, 1809-1857) 1846 image of the United States Capitol.

Despite its inability to capture fleeting moments, the daguerreotype nevertheless was used to document historical events. The exhibition includes images of parades and military festivals as well as pivotal historical moments, such as Ezra Greenleaf Weld’s (American, 1801-1874) image of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law Convention in Cazenovia, New York.

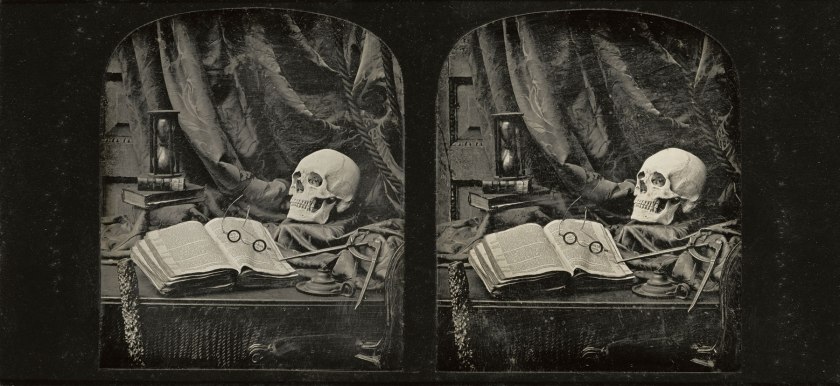

Because it was perceived as a faithful record, it was difficult to elevate the daguerreotype to the status of an art form. Nevertheless some photographers attempted to expand their studio practice to create more artistic scenes, such as The Sands of Time (1850-52), a still-life by Thomas Richard Williams (English, 1825-1871) that features books, glasses, an hourglass, and a human skull. Daguerreotypes were sometimes used for scientific experimentation, as is the case with Antoine Claudet, who used the medium as an instrument to measure focal distance.

The exhibition also features a selection of distinctive daguerreotype cases – wrapped in leather or decorated with oil painting, shell inlay, and gold foil. These elaborate cases emphasise the care that families took in protecting these treasured images, and the value they held from generation to generation.

In Focus: Daguerreotypes is on view November 3, 2015-March 20, 2016 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center. The exhibition is curated by Karen Hellman, assistant curator of photographs in the Getty Museum’s Department of Photographs.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum

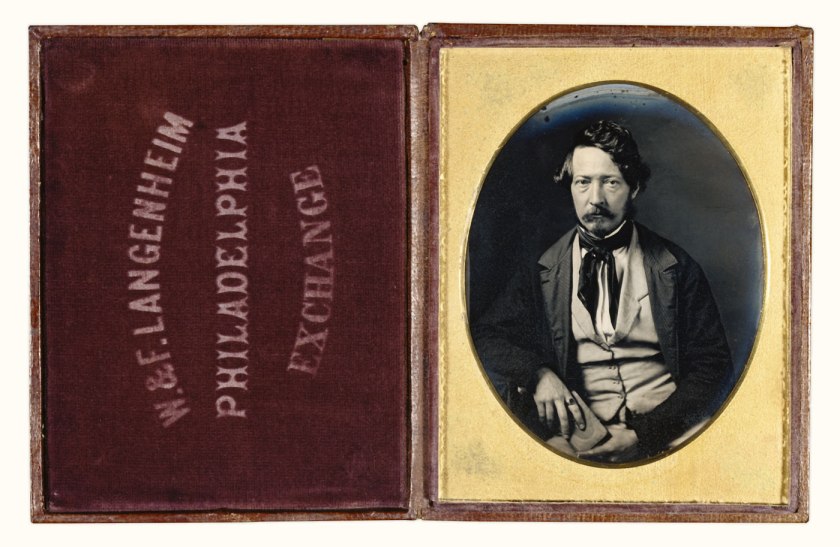

William Langenheim (American, born Germany, 1807-1874)

Portrait of Frederick Langenheim

c. 1848

Daguerreotype

1/4 plate

Image: 8.9 x 7cm (3 1/2 x 2 3/4 in.)

Mat: 10.6 x 8.3cm (4 3/16 x 3 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Carl Durheim (Swiss, 1810-1890)

Postmortem of a Child

c. 1852

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/4 plate

Image: 6.8 x 9.4cm (2 11/16 x 3 11/16 in.)

Object (whole): 12.7 x 15.1cm (5 x 5 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of a Family

c. 1850

Framed: 35.6 x 40.6cm (14 x 16 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of a Family (detail)

c. 1850

Framed: 35.6 x 40.6cm (14 x 16 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Théodore Maurisset (French, active 1834-1859)

La Daguerreotypomanie (Daguerreotypomania)

December 1839

Lithograph

Image: 26 x 35.7cm (10 1/4 x 14 1/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Samuel J. Wagstaff, Jr.

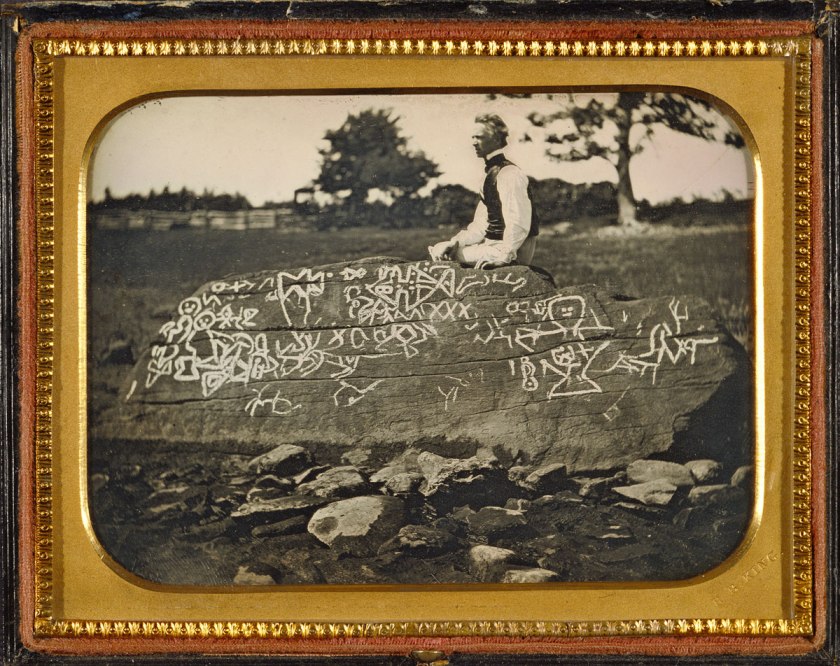

Horatio B. King (American, 1820-1889)

Seth Eastman at Dighton Rock, July 7, 1853

1853

Dighton Rock

The Dighton Rock is a 40-ton boulder, originally located in the riverbed of the Taunton River at Berkley, Massachusetts (formerly part of the town of Dighton). The rock is noted for its petroglyphs (“primarily lines, geometric shapes, and schematic drawings of people, along with writing, both verified and not.”), carved designs of ancient and uncertain origin, and the controversy about their creators. In 1963, during construction of a coffer dam, state officials removed the rock from the river for preservation. It was installed in a museum in a nearby park, Dighton Rock State Park. In 1980 it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).

Seth Eastman

Seth Eastman (1808-1875) and his second wife Mary Henderson Eastman (1818 – 24 February 1887) were instrumental in recording Native American life. Eastman was an artist and West Point graduate who served in the US Army, first as a mapmaker and illustrator. He had two tours at Fort Snelling, Minnesota Territory; during the second, extended tour he was commanding officer of the fort. During these years, he painted many studies of Native American life. He was notable for the quality of his hundreds of illustrations for Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s six-volume study on Indian Tribes of the United States (1851-1857), commissioned by the US Congress. From their time at Fort Snelling, Mary Henderson Eastman wrote a book about Dakota Sioux life and culture, which Seth Eastman illustrated. In 1838, he was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Honorary Academician…

Having retired as a Union brigadier general for disability during the American Civil War, Seth Eastman was reactivated when commissioned by Congress to make several paintings for the US Capitol. Between 1867 and 1869, he painted a series of nine scenes of American Indian life for the House Committee on Indian Affairs. In 1870 Congress commissioned Eastman to create a series of 17 paintings of important U.S. forts, to be hung in the meeting rooms of the House Committee on Military Affairs. He completed the paintings in 1875.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Thomas Richard Williams (English, 1825-1871)

The Sands of Time

1850-1852

Stereo-daguerreotype

Two 1/6 plates

Image (each): 7 x 5.9cm (2 3/4 x 2 5/16 in.)

Object (whole): 8.3 x 17.1cm (3 1/4 x 6 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Thomas Richard Williams (English, 1825-1871)

The Sands of Time (detail)

1850-1852

Stereo-daguerreotype

Two 1/6 plates

Image (each): 7 x 5.9cm (2 3/4 x 2 5/16 in.)

Object (whole): 8.3 x 17.1cm (3 1/4 x 6 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Thomas Richard Williams (5 May 1824 – 5 April 1871) was a British professional photographer and one of the pioneers of stereoscopy.

Williams’s first business was in London around 1850. He is known for his celebrated stereographic daguerreotypes of the Crystal Palace. He also did portrait photography, now in the Getty Museum’s archives, which he regarded as his greatest success…

Williams’ first studio in Lambeth served both as business and home. Here, “Williams rapidly acquired a fine reputation as portraitist. One source describes how the vicinity of the studio was often ‘blocked with a dozen carriages awaiting the visitors at Mr. Williams’ studio.’ His portraits were exquisitely crafted, and displayed a restrained elegance which became his hallmark.”

Soon his success allowed him to open a studio separate from his home, in Regent Street in 1854. With over twenty photography studios nearby competition was keen – and included his former mentor and teacher, Claudet. “Williams, with his characteristic discretion and low-key approach, did not advertise his business or put up large signs to attract clientele. It seems, though, that the gentry beat a path to his door, and his stereoscopic portraits became highly popular.”

While the mainstay of his business was his stereoscopic (3-D) portraits, he was coming into his own with an artistic vision of what photography could and would become. He became one of the first photographers on record to shoot still life and other artistic compositions. These images became popular to the point that they became “part of the birth of a new genre that was to become the stereoscopic boom of the 1850s.” The Victorians loved them; sales boomed.

In the mid-1850s, Williams contracted with the London Stereoscopic Company to publish his images. The LSC published the work of many eminent stereo photographers, including William England, and was able to mass-produce his works, which helped meet growing demand for his prints.

The LSC published three stereoscopic series by Williams.

His “First Series” was made up of portraits, artistic compositions and still life, many taken in his studio. Dr. Brian May and Elena Vidal write: “The still life studies, with their fine detail and careful composition, showed a clear influence from the 17th century Dutch painting tradition, and a profound knowledge of the iconography surrounding this genre. Photographs such as ‘The Old Larder,’ ‘Mortality’ and ‘Hawk and Duckling’ are superb examples of the unique power of stereography, with their superb three-dimensional compositions, and wealth of detail, which, combined with an outstanding artistic sensibility, resulted in images of astonishing finesse. Another remarkable group of images in this series, entitled “The Launching of the Marlborough”, taken on 31 July 1855, was highly praised in the Victorian press, since they embodied the achievement of ‘instantaneous’ photography, executed as they were from a moving boat, and managing to ‘freeze’ the waves on the surface of the sea.”

The second series was “The Crystal Palace,” this time at Sydenham, as the original Palace in Hyde Park had been dismantled. “The quality of Williams’ original daguerreotypes from this event are such that, though they contain images of hundreds of people, individual facial features of Queen Victoria and her party are clearly discernible.” …

May and Vidal write, “Through his work, Williams is now widely recognised as pivotal in the history of stereoscopic photography, since his stereo cards were the first examples of photographic art for its own sake ever to achieve wide commercial success.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey (French, 1804-1892)

Facade and North Colonnade of the Parthenon on the Acropolis, Athens

1842

Daguerreotype

Whole plate

Image: 18.8 x 24cm (7 3/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

Object (whole): 18.8 x 24cm (7 3/8 x 9 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Alphonse-Louis Poitevin (French, 1819-1882)

The Pantheon, Paris

1842

Daguerreotype

1/2 plate

Image: 15.1 x 10.2cm (5 15/16 x 4 in.)

Mat: 21.5 x 15.6cm (8 7/16 x 6 1/8 in.)

Object (whole): 27.9 x 21.9cm (11 x 8 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of a Young Man in a Top Hat

c. 1850s

Daguerreotype

1/9 plate

Open: 7.3 x 12.4cm (2 7/8 x 4 7/8 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Attributed to Dr. Hugo Stangenwald (Austrian born Germany, 1829-1899)

Portrait of Queen Kalama of Hawaii

c. 1853-1854

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/16 plate

Image: 3 x 2.5cm (1 3/16 x 1 in.)

Mat: 4.1 x 3.5cm (1 5/8 x 1 3/8 in.)

Open: 5.1 x 8.9cm (2 x 3 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Kalama Hakaleleponi Kapakuhaili (1817 – September 20, 1870) was a Queen consort of the Kingdom of Hawai’i alongside her husband, Kauikeaouli, who reigned as King Kamehameha III. Her second name is Hazelelponi in Hawaiian.

Dr Hugo Stangenwald was an Austrian physician and pioneer photographer who arrived in Honolulu in 1853.

“In January 1853m Stangenwald landed at Hilo, on the island of Hawaii, aboard a British brig. He was bound for Sydney, Australia, with his partner, Stephen Goodfellow, recently a resident of San Franciso. Together, as Stangenwald and Goodfellow, they found a profitable field of enterprise taking portraits of American missionaries and views of Hawaiian scenery during what was to have been a temporary stay. Missionary titus Coan called Stangenwald “the chief artist” and “a physician (so reported),” and summed him up as “a pleasant and pious young man.” On February 10, Coan wrote that Stangenwald and Goodfellow “are now using up all the faces in Hilo, and they soon with be through.” Can added that their prices were comparatively moderate; they charged “3$ for the smallest plates in a neat case, and a frame in proportion to the size, the amount of gold in ornamentation.” This helpful missionary went so far as to enlist the help of his colleagues in Honolulu to assist Stangenwald and Goodfellow in establishing themselves in that town.

By March 26, Stangenwald and Goodfellow were advertising the imminent opening of the daguerreian rooms next to the shoe store of J. H. Woods in Honolulu. After a week engaged in setting up their equipment and adjusting there work to the light, they were prepared to take portraits and “correct views of gentlemen’ residences, vessels, machinery and parts of the city … without reversing.” When a devastating outbreak of smallpox hit Honolulu in May, Goodfellow elected to dissolve his partnership with Stangenwald and resume his voyage to Australia. Stangenwald decided to remain in Hawaii.”

Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn. Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary 1840-1865. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000, p. 515.

Unknown maker (American)

[Portrait of an Unidentified Daguerreotypist Displaying a Selection of Daguerreotypes] / Daguerreotypist (?) Displaying Thirteen Daguerreotypes

1845

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/6 plate

Image: 6.7 x 5.2cm (2 5/8 x 2 1/16 in.)

Mat: 8.3 x 7cm (3 1/4 x 2 3/4 in.)

Open: 8.9 x 15.2cm (3 1/2 x 6 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]

1860

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/4 plate

Image: 9 x 6.5cm (3 9/16 x 2 9/16 in.)

Mat: 10.8 x 8.3cm (4 1/4 x 3 1/4 in.)

Open: 12.7 x 20.6cm (5 x 8 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin] (detail)

1860

Daguerreotype, hand-coloured

1/4 plate

Image: 9 x 6.5cm (3 9/16 x 2 9/16 in.)

Mat: 10.8 x 8.3cm (4 1/4 x 3 1/4 in.)

Open: 12.7 x 20.6cm (5 x 8 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Unknown maker (American)

Portrait of a Girl Holding a Doll

c. 1845

Daguerreotype

Framed: 24.1 x 19.1cm (9 1/2 x 7 1/2 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Auguste Belloc (French, 1800-1867)

Portrait of a Woman

May 1844

Daguerreotype

Image: 10.2 x 7.6cm (4 x 3 in.)

Framed: 24.8 x 22.9cm (9 3/4 x 9 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Auguste Belloc (French, 1800-1867)

Portrait of a Woman (detail)

May 1844

Daguerreotype

Image: 10.2 x 7.6cm (4 x 3 in.)

Framed: 24.8 x 22.9cm (9 3/4 x 9 in.)

Graham Nash Collection

Auguste Belloc (French, 1800-1867) was born in the beginning of the 19th century, in Montrabe, located in the Southwest of France (Haute-Garonne).

He began his career as a painter of miniatures and watercolours. Belloc’s first photographic studio was mentioned in 1851. Practicing daguerreotype, he became involved in wet collodion development and improved the wax coating process, helping the pictures to keep their wet-like luster.

But the most important research he led was about color stereoscopy (3 dimensional photography). Known for his nudes and portraits, he looked for the best way to express the reality and found a new method. This practice considered erotic photography and was declared illegal by the police in 1856 and 1860.

Marion Perceval. “Auguste Belloc,” in John Hannavy (ed.,). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge, 2008, p. 146.

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![James Maguire (American, 1816-1851) '[Portrait of Zachary Taylor]' 1847 James Maguire (American, 1816-1851) '[Portrait of Zachary Taylor]' 1847](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gm_06991301-web.jpg?w=650&h=749)

![James P. Weston (American, active South America about 1849 and New York 1851-1852 and 1855-1857) '[Portrait of an Asian Man in Top Hat]' c. 1856 James P. Weston (American, active South America about 1849 and New York 1851-1852 and 1855-1857) '[Portrait of an Asian Man in Top Hat]' c. 1856](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gm_05595301-web.jpg?w=650&h=841)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Portrait of an Unidentified Daguerreotypist Displaying a Selection of Daguerreotypes] / Daguerreotypist (?) Displaying Thirteen Daguerreotypes' 1845 Unknown maker (American) '[Portrait of an Unidentified Daguerreotypist Displaying a Selection of Daguerreotypes] / Daguerreotypist (?) Displaying Thirteen Daguerreotypes' 1845](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gm_06329401-web.jpg?w=650&h=737)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gm_05620001-web.jpg?w=650&h=838)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 (detail) Unknown maker (American) '[Chinese Woman with a Mandolin]' 1860 (detail)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gm_05620001-detail.jpg?w=650&h=839)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'El juego de las probabilidades' [The Game of Probabilities] 2007](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/el-juego-de-las-probabilidades-web.jpg?w=840)

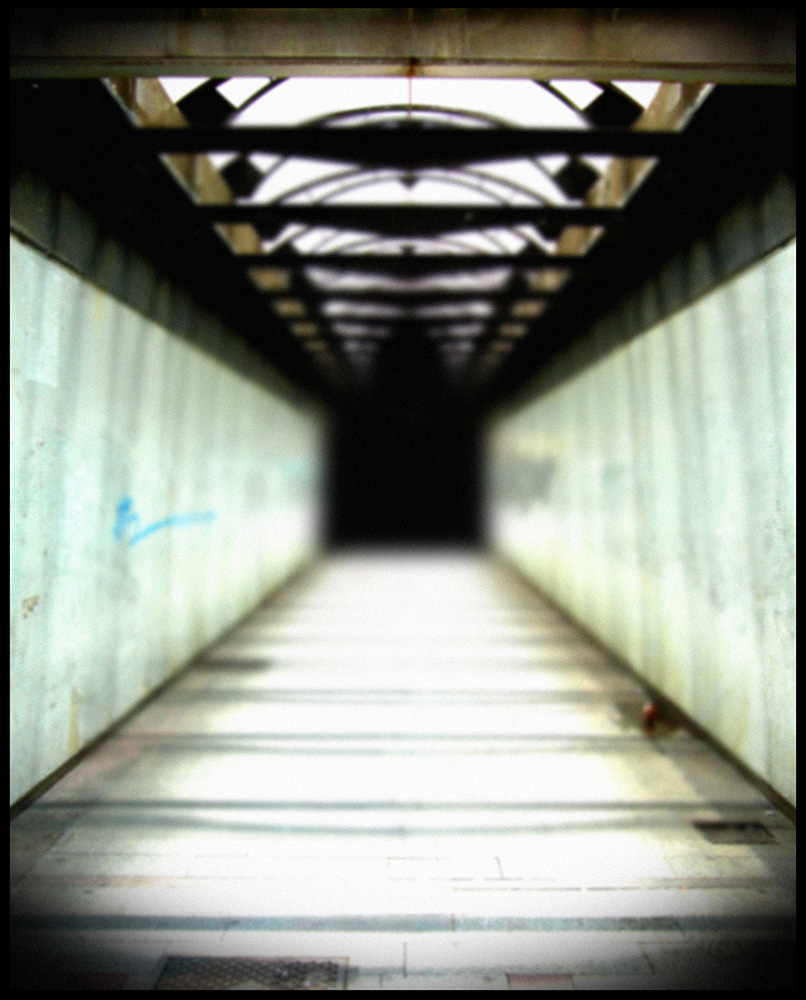

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994 Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ambulatorio-web.jpg?w=840&h=555)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986 Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/cortinas-de-bac3b1o-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narcisos (en proceso)' [Narcissi (in process)] 1995-2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/narcisos-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001 Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/narciso-web.jpg?w=840&h=878)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004 Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/re_trato-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

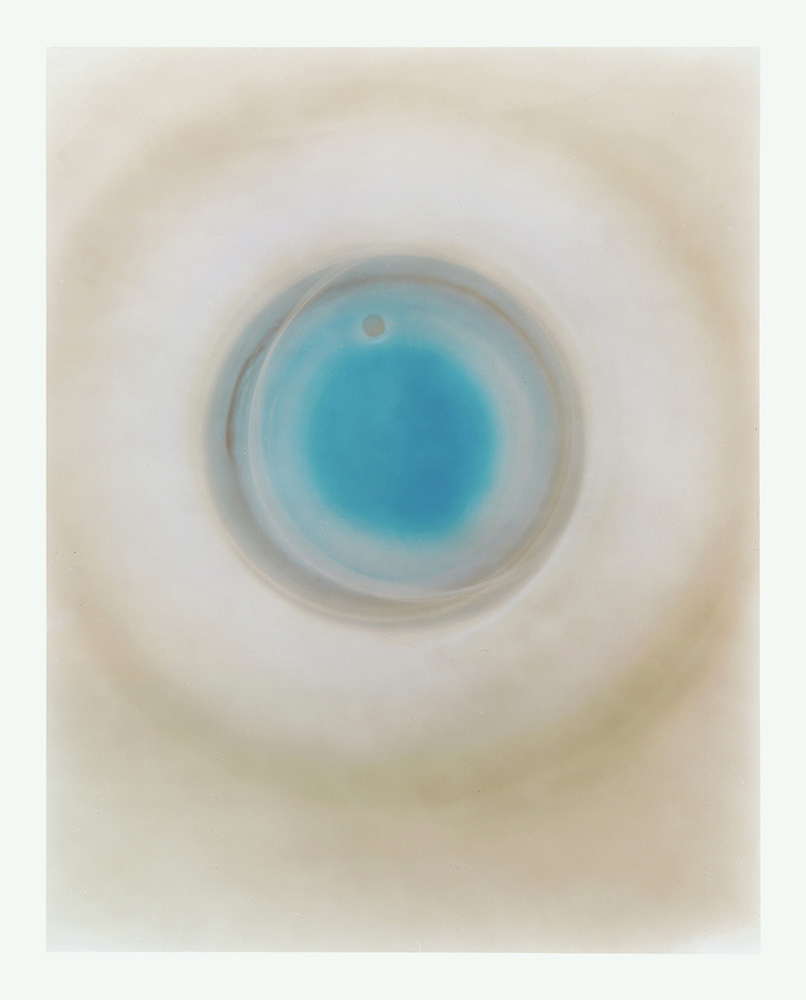

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995 Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/aliento-web.jpg?w=840&h=687)

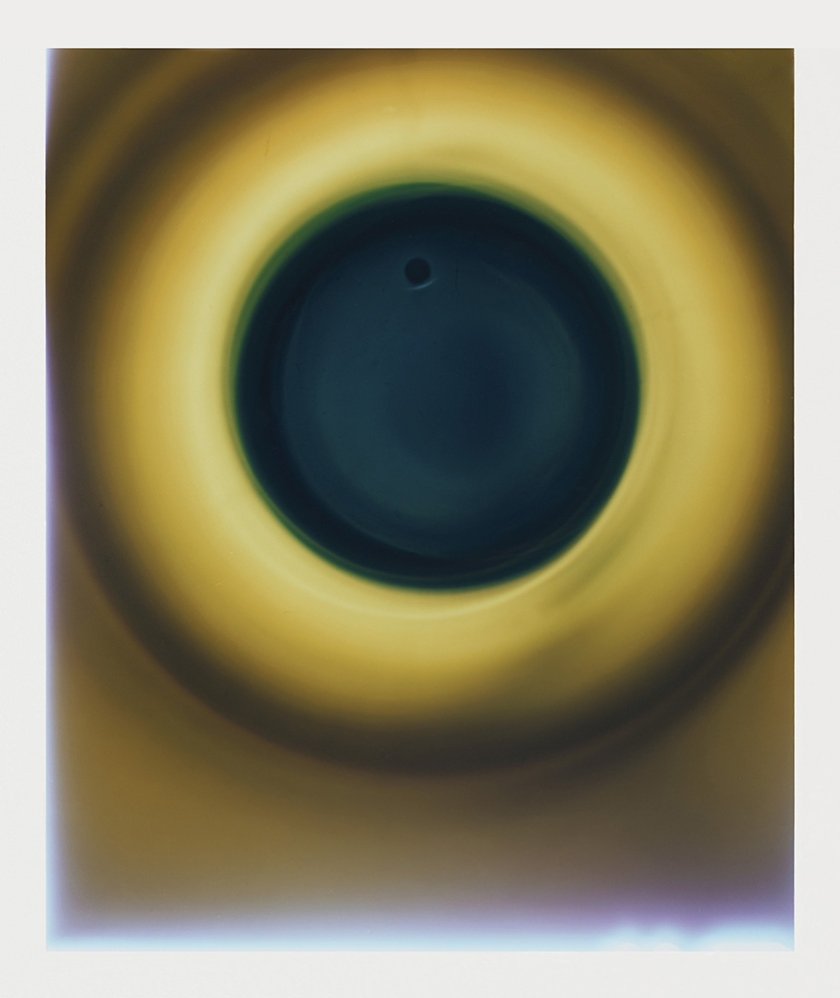

![Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002 Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/la-mirada-del-cc3adclope-web.jpg?w=840&h=525)

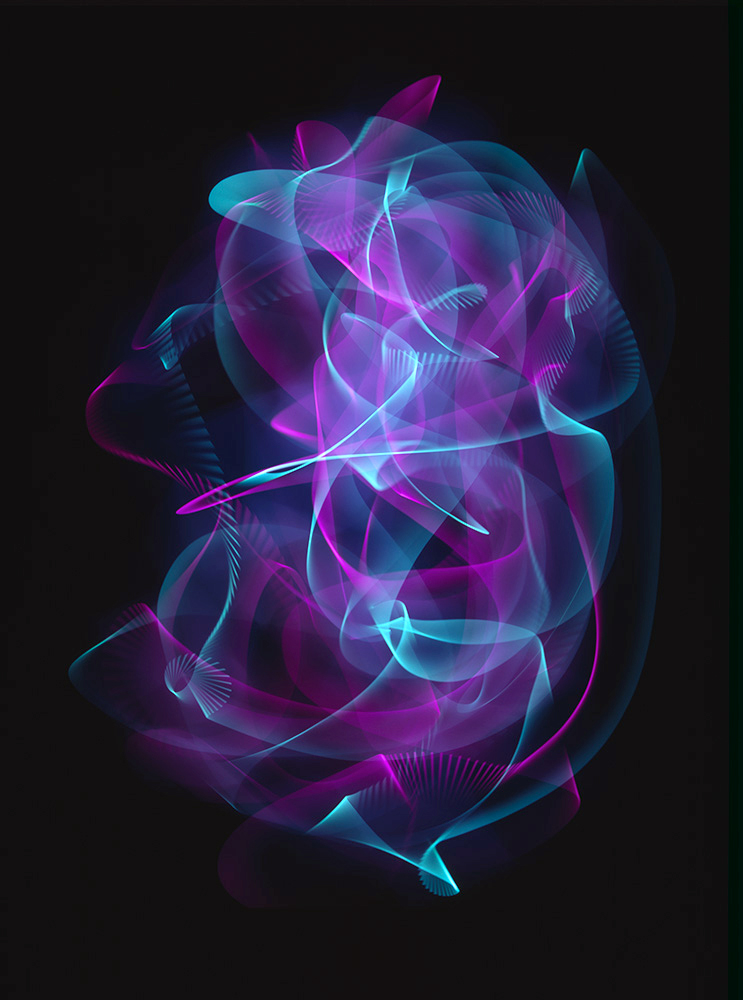

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011 Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/horizonte-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Fundido a blanco (dos retratos)' [Fade to White (Two Portraits)] 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/fade-to-white-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Sedimentaciones' [Sedimentations] 2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sedimentaciones-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-b-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-c-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.