Exhibition dates: 26th October 2018 – 24th February 2019

Curators: Maya Benton in collaboration with The Photographers’ Gallery curator, Anna Dannemann and Jewish Museum London curator, Morgan Wadsworth-Boyle.

Presented simultaneously at The Photographers’ Gallery and Jewish Museum London, Roman Vishniac Rediscovered is the first UK retrospective of Russian born American photographer, Roman Vishniac (1897-1990).

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Interior of the Anhalter Bahnhof railway terminus near Potsdamer Platz, Berlin

1929 – early 1930s

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at The Photographers’ Gallery

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Wondrous, glorious images

Apart from the title, Roman Vishniac “Rediscovered” – photographically, I never thought he went away? – this is a magnificent exhibition of Vishniac’s complete works.

Since the press release states, “Roman Vishniac Rediscovered offers a timely reappraisal of Vishniac’s vast photographic output and legacy and brings together – for the first time – his complete works including recently discovered vintage prints, rare and ‘lost’ film footage from his pre-war period, contact sheets, personal correspondence, original magazine publications, newly created exhibition prints as well as his acclaimed photomicroscopy…” perhaps the exhibition should have been titled: Roman Vishniac Reappraised or Roman Vishniac: Complete Works. Each makes more sense than the title the curators chose.

Vishniac’s work is powerful and eloquent, a formal, classical, and yet poetic representation of the time and space of the photographs taking. Modernist yet romantic, monumental, sociological yet playful, his work imbibes of the music of people and place, portraying the rituals of an old society about to be swept away by the maelstrom of war. They are a joy to behold.

Here is happiness and sadness, urban poverty, isolation (as in figures from each other, figures isolated within their world, and within the pictorial frame – see the people walking in every direction in Isaac Street, Kazimierz, Cracow 1935-38, below), and nostalgia (for what has been lost). Here is life… and death.

Here is a handsome man, Ernst Kaufmann, born in Krefeld, Germany, in 1911. Arrested in June 1941 and killed in August of that year in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. Killed at barely 30 years old. As Vishniac recalls of his portrait of the seven year old David Eckstein, ‘I watched this little boy for almost an hour, and in this moment I saw the whole sadness of the world.’ Never forget what human beings are capable of, lest history repeat itself, and all our hard fought freedoms are destroyed.

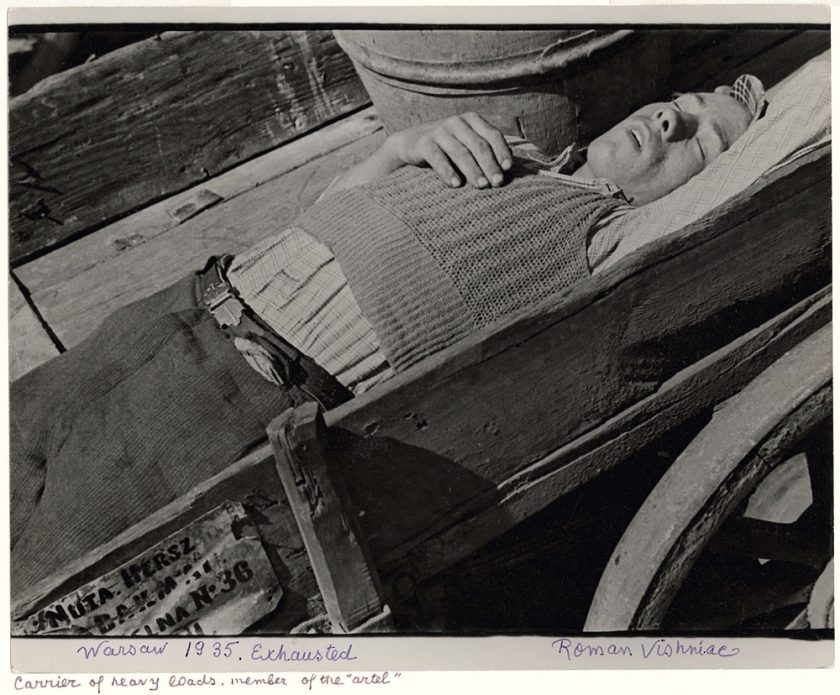

Despite the hubbub and movement of the people, towns and marketplaces, for me it is the sensitivity of a quiet moment, beautifully observed, that gets me every time. That hand (Exhausted. A Carrier of Heavy Loads, Warsaw c. 1935-1938, below), resting on the chest of an exhausted porter, seen in all its clarity and in humanity is transcendent. That intense feeling of an extended, (in)decisive moment, if ever there was one.

In my humble opinion, Vishniac is one of the greatest 20th century social documentary photographers to have ever lived.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Photographers’ Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Interview with curator Maya Benton

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

German family walking between taxicabs in front of the Ufa-Palast movie theater, Berlin

late 1920s – early 1930s

Courtesy International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

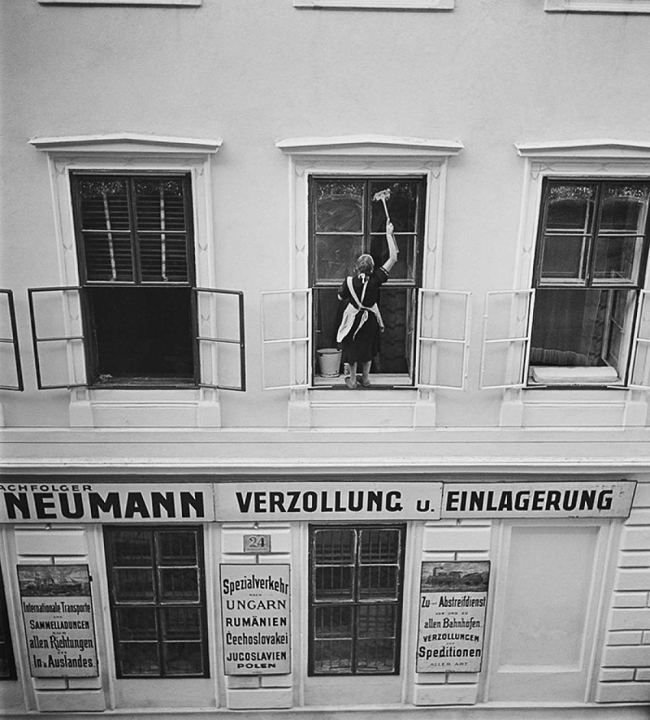

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Woman washing windows above Mandtler & Neumann Speditionen (Mandtler & Neumann Forwarding Agents), Ferdinandstrasse, Leopoldstadt, Vienna

1930s

Courtesy International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Jewish school children, Mukacevo

c. 1935-1938

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at Jewish Museum London

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

From 1935 to 1938, Vishniac made numerous trips to the city of Mukacevo, a major center of religious learning among Jews from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Carpathian region. Mukacevo was widely known for its famous rabbis and yeshivot (religious schools). This image of Jewish schoolchildren appears in cropped form on the cover of Vishniac’s first posthumous publication, To Give Them Light; the recently digitised negative reveals that it represents only one-fifth of the full frame. Vishniac often directed printers or publishers to crop his images to focus on religiously observant Jewish men or boys, identifiable by their dress, an editorial decision that sometimes detracted from the composition by subverting aesthetic considerations to emphasise religious and observant life. The negative reveals Vishniac’s instinctive compositional acumen: a bustling and vibrant street scene, with a boy’s beaming, slightly out-of-focus face in the foreground and numerous hands pushing into and out of the frame, communicating the vitality and liveliness of the students.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

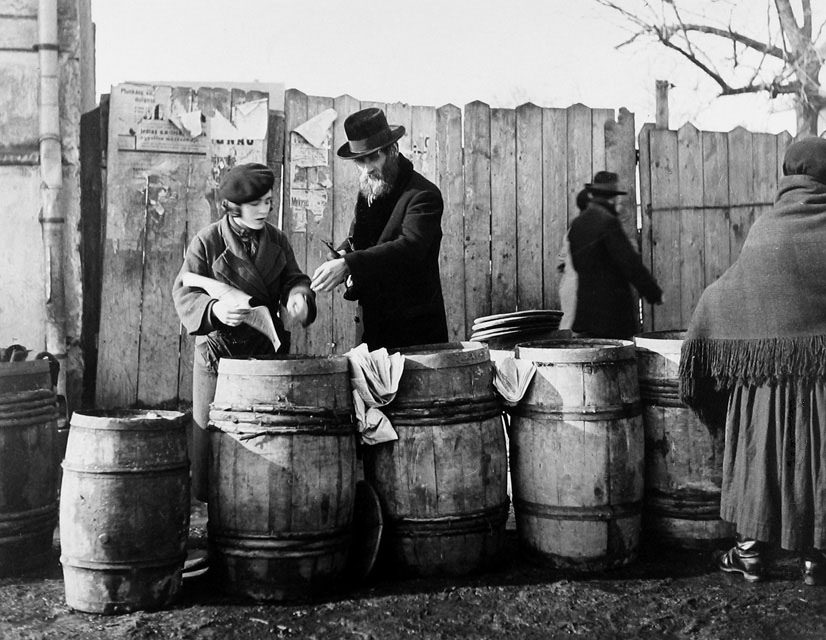

Roman Vishniac (1897-1990)

Man purchasing herring, wrapped in newspaper, for a Sabbath meal, Mukacevo

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Fish is the Favored Food for the Kosher Table

c. 1935-1938

Gelatin silver print

Image (paper): 11 1/2 x 9 3/16 in. (29.2 x 23.3cm)

Collection Philip Allen

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

“This image of a boy bending over a vat of herring communicates the excitement of the marketplace and the sheer abundance of herring. The unparalleled quality of the print transmits every detail, from the wet cobblestones and circular motion of the swimming fish to the rapid, eager movement of hands reaching in to grab the herring. Rather than focusing on religious life, these early prints demonstrate the vitality and frantic charm of a town rushing to prepare for the Sabbath.”

Maya Benton, ICP Adjunct Curator

These rare vintage prints are part of a collection of sixteen recently discovered prints that comprised Vishniac’s first exhibition abroad, and were displayed in the New York office of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) in 1938. Vishniac developed these early prints in his apartment in Berlin, and they are rare early examples of his virtuosic skill as a master printmaker. He gifted all sixteen prints to an employee of the New York office of the JDC who had helped him to organise his first exhibit; these prints are on loan from his son.

The image of a boy bending over a vat of herring communicates the excitement of the marketplace and the sheer abundance of herring. The unparalleled quality of the print transmits every detail, from the wet cobblestones and circular motion of the swimming fish to the rapid, eager movement of hands reaching in to grab the herring. Rather than focusing on religious life, these early prints demonstrate the vitality and frantic charm of a town rushing to prepare for the Sabbath.

Anonymous text. “Roman Vishniac,” on the International Center of Photography website Nd [Online] Cited 16/03/2022

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Young Jewish boys suspicious of strangers, Mukachevo

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Three women, Mukacevo

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

The notice on the wall reads “Come Celebrate Chanukah”

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990))

Jewish street vendors, Warsaw, Poland

1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Children playing outdoors and watching a game

c. 1935-1937

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Children playing on a street lined with swastika flags

mid-1930s

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Nat Gutman’s Wife, Warsaw

1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Nat Gutman, the porter, Warsaw 1935-1938 from A Vanished World, 1983 is the photograph of her husband. After working as a bank cashier for six years, Nat Gutman was dismissed because he was a Jew. He became a porter. The loads usually weighed forty-five to ninety pounds. This was the kind of work that bank cashier Gutman, a man with a bad hernia, was reduced to in order to support his wife and son. The family were exterminated.

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

A street of Kazimierz, Cracow

1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Isaac Street, Kazimierz, Krakow

1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Isaac Street, Kazimierz, Cracow

1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Window washer balancing on a ladder, Berlin

mid-1930s

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at The Photographers’ Gallery

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Exhausted. A Carrier of Heavy Loads, Warsaw

c. 1935-38

Gelatin silver print

7 1/2 x 10 in. (19.1 x 25.4cm)

International Center of Photography

Gift of Mara Vishniac Kohn, 2013

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

“This unpublished image of a porter at rest in his wagon demonstrates Vishniac’s modern aesthetic and the influence of the avant-garde on his work. The diagonal slope of the central figure, stretched out along a sloping plane, fills the entire frame. The intuitive amalgamation of patterns and textures, one of Vishniac’s greatest talents, is evident throughout the image: the light reflected on the ornamented belt buckle; the double-patterned cable knit of his shrunken wool vest, which barely conceals a plaid shirt; and the round shapes of a wheel and bucket that divide the angular line formed by the central figure. It is a triumph of textures, angles, and lines, yet the worn sign with the name Nuta Hersz and his porter license number reminds us that the subject of the photograph is the victim of anti-Semitic boycotts and the limited job opportunities (only vendors and porters) permitted to Jews in Poland at that time.”

Maya Benton, ICP Adjunct Curator

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Villagers in the Carpathian Mountains

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

“Vishniac traveled to remote Jewish villages in rural Carpathian Ruthenia throughout the late 1930s, and in many cases was the only photographer to ever document these communities, which had been isolated for hundreds of years, yet maintained an enduring connection to Jewish observance, customs, and traditions.

Every detail of this image makes it a nearly perfect photograph: the sense of movement and the figures’ varied gestures and vibrant expressions; the carefully balanced horizontal bands of shadow and striped fabric; the detail of a woman peering out of a window while a glass pane on the facing structure points in the direction of an impossibly angled triangular building that vertically divides the frame in half; and the collective sense of surprise at encountering the photographer. Like much of Vishniac’s unpublished work, this composition recalls Henri Cartier-Bresson’s description of the decisive moment (a precise organisation of forms that give a time and place its ideal expression) and places Vishniac on par with the great photographers of the 20th century.”

Maya Benton, ICP Adjunct Curator

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

[David Eckstein, seven years old, and classmates in cheder (Jewish elementary school), Brod]

c. 1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

“The boy in this photograph has been identified as David Eckstein, a Holocaust survivor currently living in a commune in the American Southwest. Born in 1930 in the small town of Brod, Eckstein was seven years old when Vishniac took several photographs of him, his classmates, and his teacher just before the onslaught of World War II. Vishniac later recalled, ‘I watched this little boy for almost an hour, and in this moment I saw the whole sadness of the world.’ This portrait was later selected as the cover of Vishniac’s first publication, Polish Jews: A Pictorial Record (1947), and reprinted on the cover of I. B. Singer’s National Book Award-winning collection of stories, A Day of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing Up in Warsaw (1969).”

Maya Benton, ICP Adjunct Curator

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

[Grandmother and grandchildren in basement dwelling, Krochmaina Street, Warsaw]

c. 1935-1938

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

“Vishniac documented urban poverty in Warsaw, often focusing on the dark, cold basement dwellings of families where hungry Jewish children lived in crowded conditions. Vishniac photographed this woman taking care of her grandchildren while their parents searched for work in one of 26 basement compartments, each inhabited by a large family. In June 1941, the National Jewish Monthly published this image with the caption ‘Polish Jewry, once the bulwark of world Jewry, is done for as a community. Even if Hitler were to lose power tomorrow, their institutions and organisations are hopelessly smashed, could not be rebuilt in generations. But individuals remain, starved and persecuted. This picture shows an old grandmother and her grandchildren. What is going to become of them, and of the millions of other innocent victims of Fascist violence and terror?'”

Maya Benton, ICP Adjunct Curator

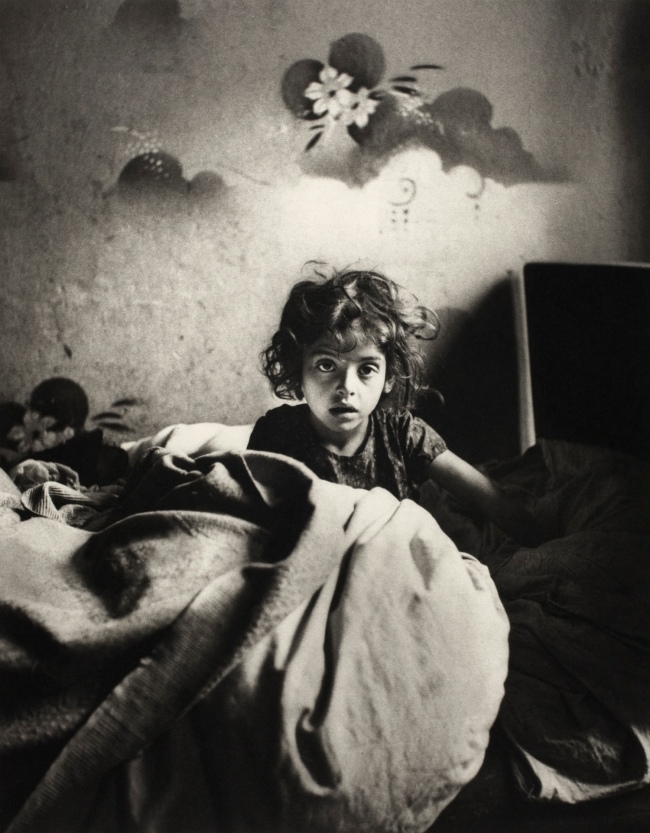

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Sara, sitting in bed in a basement dwelling, with stencilled flowers above her head, Warsaw

c. 1935-1937

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at The Photographers’ Gallery

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Vishniac documented the basement dwellings of Warsaw using the scant natural light that trickled through a few narrow, high windows, necessitating that he shoot during the day, when adults were often out looking for work or peddling their wares and children were sometimes the only inhabitants indoors. This photograph of Sara, one of Vishniac’s most iconic images, was reproduced on charity tins, or tzedakah boxes, and circulated throughout France by Jewish social service organisations, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (AJDC) in the late 1930s.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

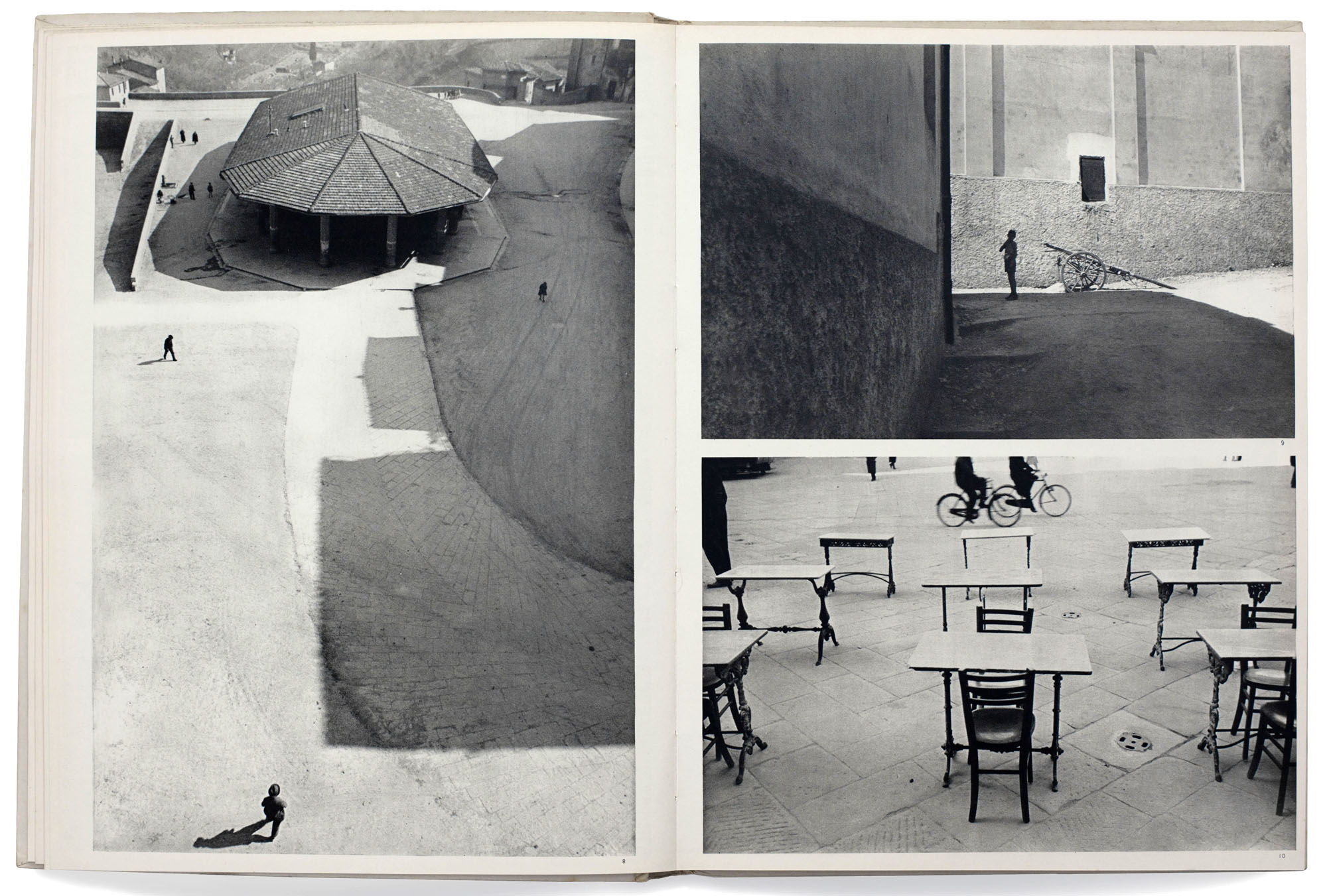

An extraordinarily versatile and innovative photographer, Vishniac is best known for having created one of the most widely recognised and reproduced photographic records of Jewish life in Eastern Europe between the two World Wars. Featuring many of his most iconic works, this comprehensive exhibition further introduces recently discovered and lesser-known chapters of his photographic career from the early 1920s to the late 1970s. The cross-venue exhibition presents radically diverse bodies of work and positions Vishniac as one of the most important social documentary photographers of the 20th century whose work also sits within a broader tradition of 1930s modernist photography.

Born in Pavlovsk, Russia in 1897 to a Jewish family Roman Vishniac was raised in Moscow. On his seventh birthday, he was given a camera and a microscope which began a lifelong fascination with photography and science. He began to conduct early scientific experiments attaching the camera to the microscope and as a teenager became an avid amateur photographer and student of biology, chemistry and zoology. In 1920, following the Bolshevik Revolution, he immigrated to Berlin where he joined some of the city’s many flourishing camera clubs. Inspired by the cosmopolitanism and rich cultural experimentation in Berlin at this time, Vishniac used his camera to document his surroundings. This early body of work reflects the influence of European modernism with his framing and compositions favouring sharp angles and dramatic use of light and shade to inform his subject matter.

Vishniac’s development as a photographer coincided with the enormous political changes occurring in Germany, which he steadfastly captured in his images. They represent an unsettling visual foreboding of the growing signs of oppression, the loss of rights for Jews, the rise of Nazism in Germany, the insidious propaganda – swastika flags and military parades, which were taking over both the streets and daily life. German Jews routinely had their businesses boycotted, were banned from many public places and expelled from Aryanised schools. They were also prevented from pursuing professions in law, medicine, teaching, and photography, among many other indignities and curtailments of civil liberties. Vishniac recorded this painful new reality through uncompromising images showing Jewish soup kitchens, schools and hospitals, immigration offices and Zionist agrarian training camps, his photos tracking the speed with which the city changed from an open, intellectual society to one where militarism and fascism were closing in.

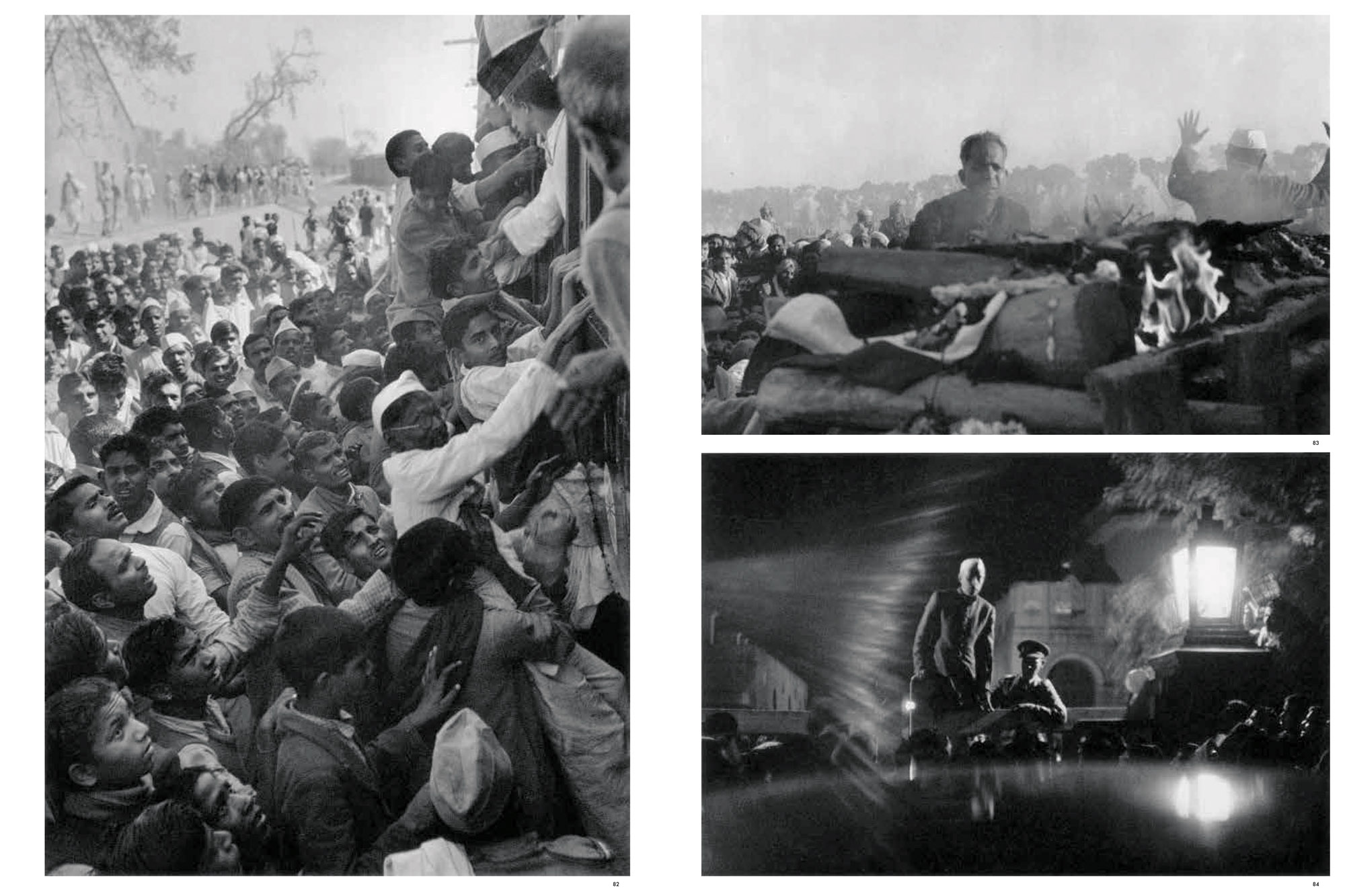

Social and political documentation quickly became a focal point of his work and drew the attention of organisations wanting to raise awareness and gain support for the Jewish population. In 1935, Vishniac was commissioned by the world’s largest Jewish relief organisation, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), to photograph impoverished Jewish communities in Eastern Europe. These images were intended to support relief efforts and were used in fundraising campaigns for an American donor audience. When the war broke out only a few years later, his photos served increasingly urgent refugee efforts, before finally, at the end of the war and the genocide enacted by Nazi Germany, Vishniac’s images became the most comprehensive photographic record by a single photographer of a vanished world.

Vishniac left Europe in 1940 and arrived in New York with his family on New Year’s Day, 1941. He continued to record the impact of World War II throughout the 1940s and 50s in particular focusing on the arrival of Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors in the US, but also looking at other immigrant communities including Chinese Americans. In 1947, he returned to Europe to document refugees and relief efforts in Jewish Displaced Persons camps and also to witness the ruins of his former hometown, Berlin. He also continued his biological studies and supplemented his income by teaching and writing.

In New York, Vishniac established himself as a freelance photographer and built a successful portrait studio on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. At the same time he dedicated himself to scientific research, resuming his interest in Photomicroscopy. This particular application of photography became the primary focus of his work during the last 45 years of his life. By the mid-1950s, he was regarded as a pioneer in the field, developing increasingly sophisticated techniques for photographing and filming microscopic life forms. Vishniac was appointed Professor of Biology and Art at several universities and his groundbreaking images and scientific research were published in hundreds of magazines and books.

Although he was mainly embedded in the scientific community, Vishniac was a keen observer and scholar of art, culture, and history and would have been aware of developments in photography going on around him and the work of his contemporaries. In 1955, famed photographer and museum curator Edward Steichen featured several of Vishniac’s photographs in the influential book and travelling exhibition The Family of Man shown at the Museum of Modern Art. Steichen later describes the importance of Vishniac’s work. “[He]… gives a last minute look at the human beings he photographed just before the fury of Nazi brutality exterminated them. The resulting photographs are among photography’s finest documents of a time and place.”

Roman Vishniac Rediscovered offers a timely reappraisal of Vishniac’s vast photographic output and legacy and brings together – for the first time – his complete works including recently discovered vintage prints, rare and ‘lost’ film footage from his pre-war period, contact sheets, personal correspondence, original magazine publications, newly created exhibition prints as well as his acclaimed photomicroscopy.

Drawn from the Roman Vishniac Archive at the International Center of Photography, New York and curated by Maya Benton in collaboration with The Photographers’ Gallery curator, Anna Dannemann and Jewish Museum London curator, Morgan Wadsworth-Boyle, each venue will provide additional contextual material to illuminate the works on display and bring the artist, his works and significance to the attention of UK audiences. Roman Vishniac Rediscovered is organised by the International Center of Photography.

Press release from The Photographers’ Gallery

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Inside the Jewish quarter, Bratislava

c. 1935-1938

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at Jewish Museum London

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

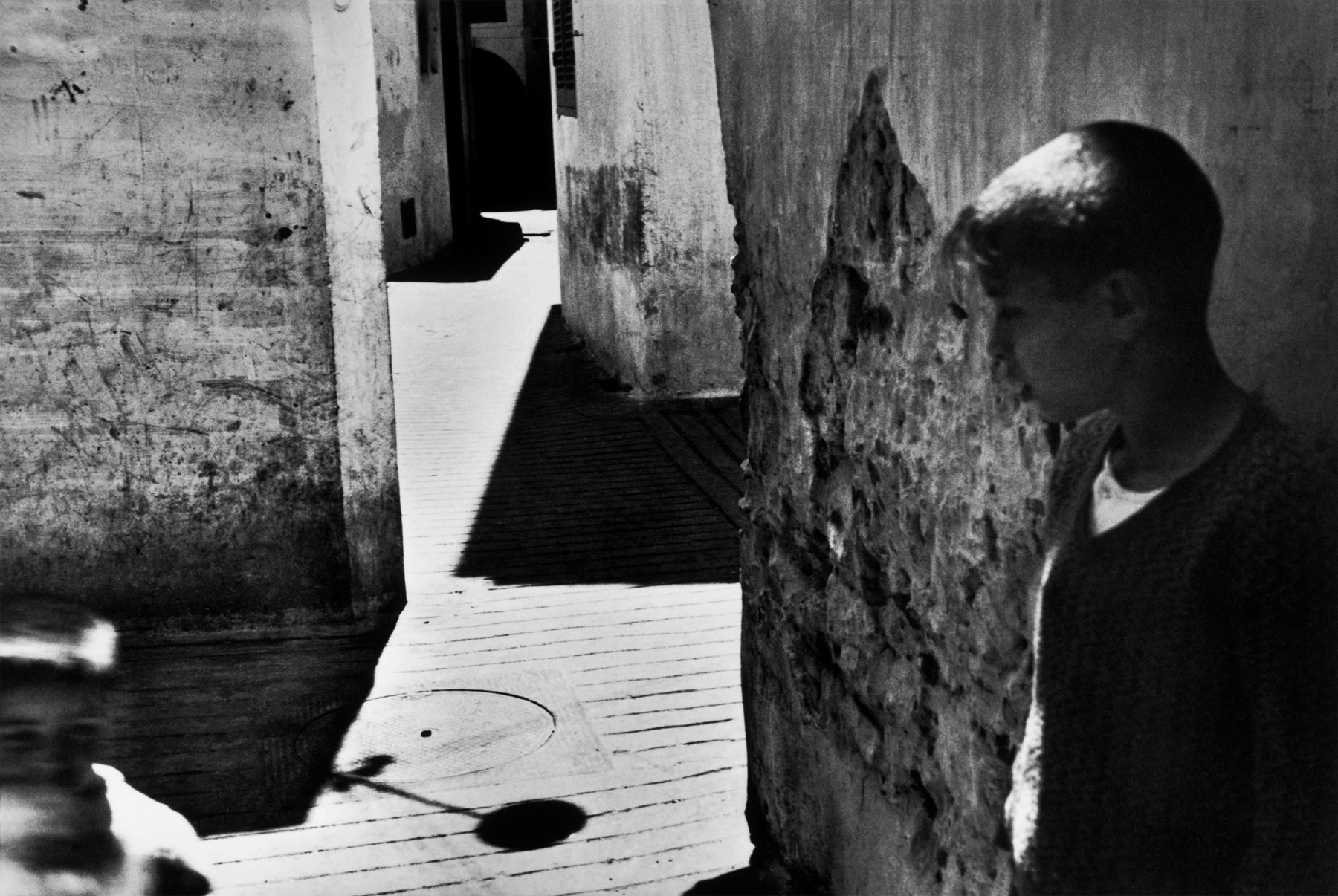

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Children at Play, Bratislava

c. 1935-1938

Courtesy International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Vishniac’s daughter Mara posing in front of an election poster for Hindenburg and Hitler that reads “The Marshal and the Corporal: Fight with Us for Peace and Equal Rights,” Wilmersdorf, Berlin

1933

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at Jewish Museum London

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Vishniac’s daughter Mara, age seven, was photographed standing in front of this 1933 poster celebrating Hitler’s recent appointment as German chancellor. The poster advertises a plebiscite to permit withdrawal from the League of Nations and Geneva Disarmament Conference, which restricted Germany’s ability to develop a military. Other posters include the slogans “Mothers, fight for your children!,” “The coming generation accuses you!,” and “In 8 months… 2,250,000 countrymen able to put food on the table. Bolshevism destroyed. Sectionalism overcome. A kingdom and order of cleanliness built… Those are the achievements of Hitler’s rule…”

Text from the International Center of Photography website

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Benedictine nun reading, probably France

1930s, printed 2012

Photo digital inkjet print

12 x 11 3/8 in. (30.5 x 29cm)

International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Ernst Kaufmann, center, and unidentified Zionist youth, wearing clogs while learning construction techniques in a quarry, Werkdorp Nieuwesluis, Wieringermeer, The Netherlands

1938-1939

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at Jewish Museum London

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

Ernst Kaufmann was born in Krefeld, Germany, in 1911. He was arrested in June 1941 and killed in August of that year in the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

This photograph is strikingly similar in subject and composition to a bronze relief plaque made in 1935 by Dutch artist Hildo Krop (1884-1970) for the monument on the Afsluitdijk, a dam that was completed in 1933 in the north of the Netherlands. The relief depicts three stoneworkers below the text “A nation that lives builds for the future.” Dutch modernist architect Willem Dudok (1884-1974) designed the Afsluitdijk and in 1935 Krop’s plaque was added. The dam was a triumph of Dutch engineering and a source of national pride. Residents of the Werkdorp probably took Vishniac to the Afsluitdijk; the well-known relief undoubtedly inspired him to stage this shot, an ideal composition for his heroic image of Jewish pioneers in the Werkdorp, and an unusual conflation of Dutch nationalist and Zionist visual sensibilities.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Beach dwellers in the afternoon, Nice, France

c. 1939

Courtesy International Center of Photography

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

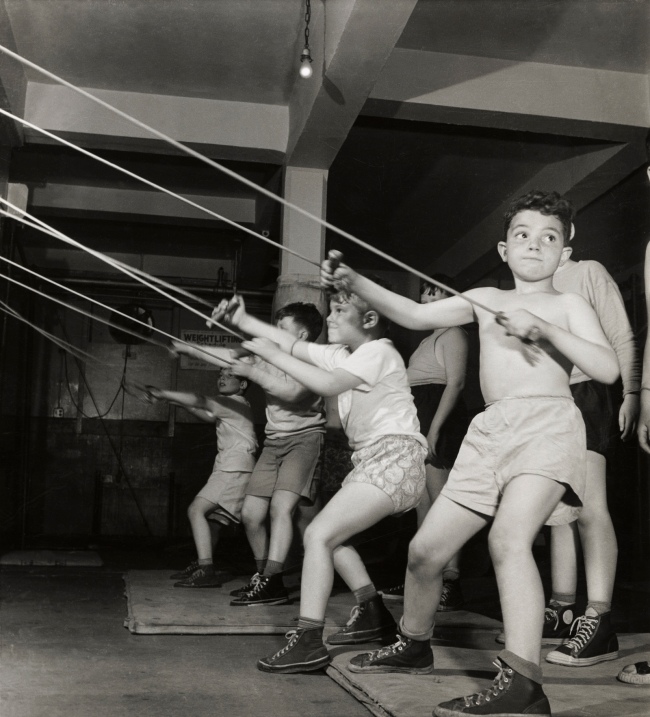

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Boys exercising in the gymnasium of the Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn

1949

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at The Photographers’ Gallery

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

The Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, known as the “J,” was established in 1927 to serve the growing population of first-generation American Jews migrating to South Brooklyn. The J’s mission, to “ennoble Jewish youth” by building and fostering a sense of Jewish community, was accomplished through the promotion of arts and recreation for all ages. American Jewish major league baseball legend Sandy Koufax, a regular at the J, had started his sports career there as a basketball player.

In a dramatic departure from his iconic photographs of impoverished children in prewar eastern Europe, here Vishniac focused on the strong, healthy young American children. The children’s vitality is reinforced by the diagonal lines and geometric angles of the ropes, contributing to a forceful and innovative composition reflective of Vishniac’s previously unknown American work from the 1940s.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

Roman Vishniac (America born Russia, 1897-1990)

Customers waiting in line at a butcher’s counter during wartime rationing, Washington Market, New York

1941-44

Courtesy International Center of Photography

On display at The Photographers’ Gallery

© Mara Vishniac Kohn

New York’s Washington Market, famed for its exceptional variety and quantity of food, was established in the eighteenth century. Vishniac documented the mostly female customers waiting for service during a period of wartime restrictions and food rationing. Through careful framing – customers stand against bare counters and voided display cases – he captured disenchanted expressions that can be read as a projection of Vishniac’s own experience as a new immigrant in America, as well as a record of comparative privation in the former plenty of Washington Market. As such, they anticipate the isolation and indifference shown in The Americans by Robert Frank, another Jewish immigrant from war-torn Europe.

Text from the International Center of Photography website

The Photographers’ Gallery

16-18 Ramillies Street

London

W1F 7LW

Opening hours:

Mon – Wed: 10.00 – 18.00

Thursday – Friday: 10.00 – 20.00

Satuday: 10.00 – 18.00

Sunday: 11.00 – 18.00

The Jewish Museum

A museum without walls at the moment.

The Photographers’ Gallery website

![Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) '[David Eckstein, seven years old, and classmates in cheder (Jewish elementary school), Brod]' c. 1938 Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) '[David Eckstein, seven years old, and classmates in cheder (Jewish elementary school), Brod]' c. 1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/icp_vishniac_pressimage_8-web.jpg?w=650&h=794)

![Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) '[Grandmother and grandchildren in basement dwelling, Krochmaina Street, Warsaw]' c. 1935-1938 Roman Vishniac (1897-1990) '[Grandmother and grandchildren in basement dwelling, Krochmaina Street, Warsaw]' c. 1935-1938](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/vishniac-grandmother-and-grandchildren-web.jpg?w=650&h=698)

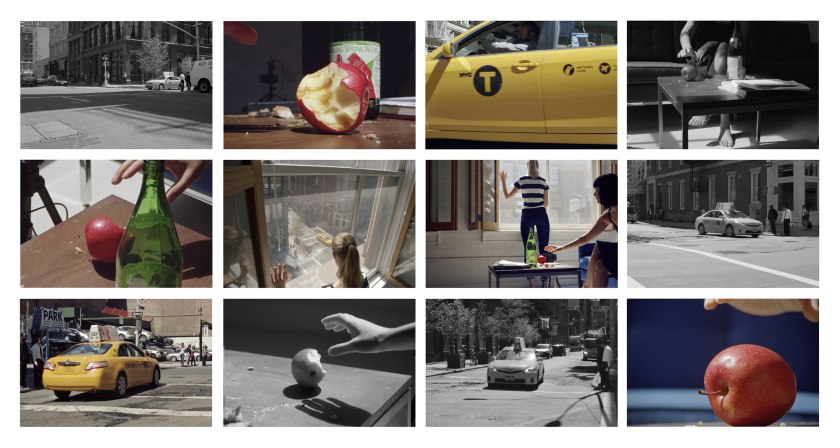

![Oscar Muñoz. 'El juego de las probabilidades' [The Game of Probabilities] 2007](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/el-juego-de-las-probabilidades-web.jpg?w=840)

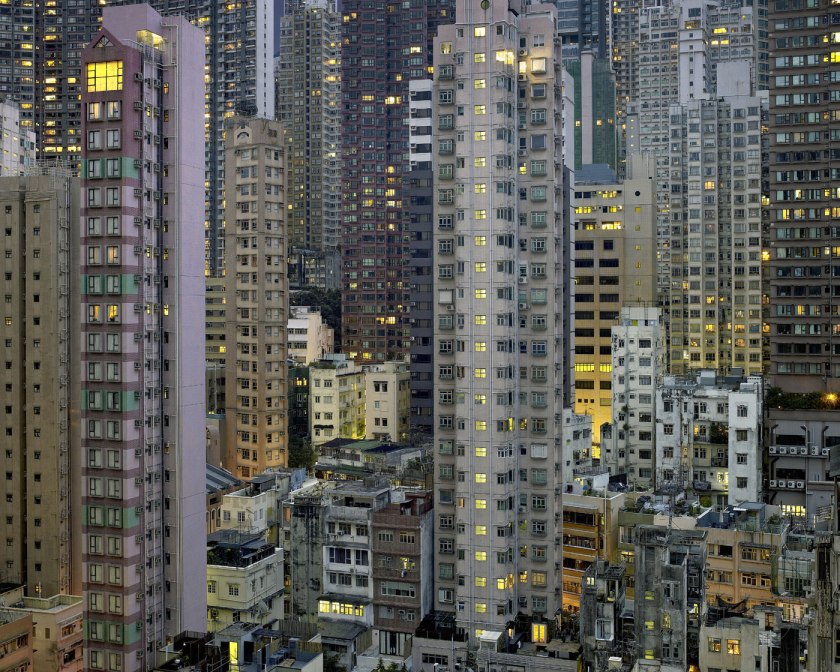

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994 Oscar Muñoz. 'Ambulatorio' [Ambulatory] 1994](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ambulatorio-web.jpg?w=840&h=555)

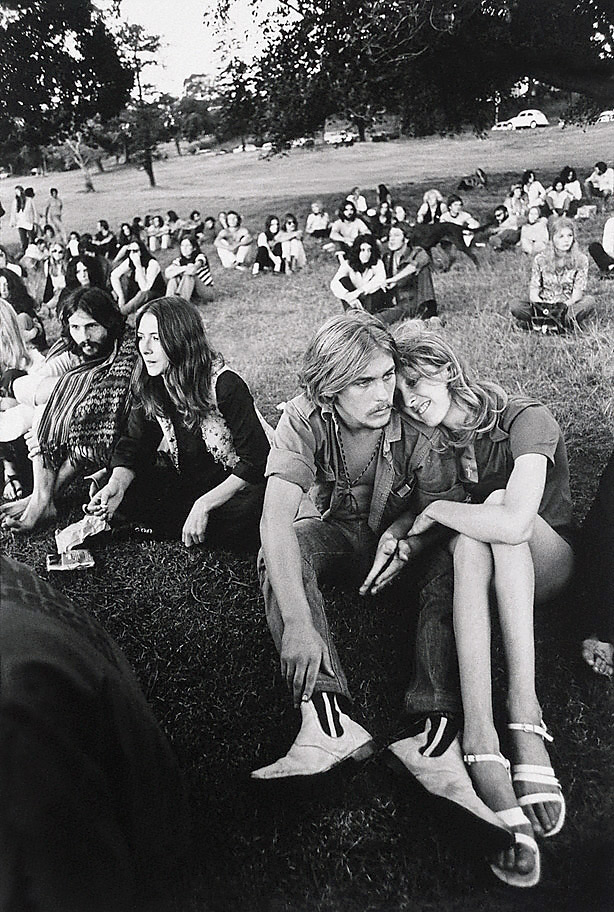

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986 Oscar Muñoz. 'Cortinas de Baño' [Shower curtains] 1985-1986](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/cortinas-de-bac3b1o-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narcisos (en proceso)' [Narcissi (in process)] 1995-2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/narcisos-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001 Oscar Muñoz. 'Narciso' [Narcissus] 2001](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/narciso-web.jpg?w=840&h=878)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004 Oscar Muñoz. 'Re/trato' [Portrait/I Try Again] 2004](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/re_trato-web.jpg?w=840&h=568)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995 Oscar Muñoz. 'Aliento' [Breath] 1995](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/aliento-web.jpg?w=840&h=687)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002 Oscar Muñoz. 'La mirada del cíclope' [The Cyclops' Gaze] 2002](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/la-mirada-del-cc3adclope-web.jpg?w=840&h=525)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011 Oscar Muñoz. 'Horizonte [Horizon]' 2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/horizonte-web.jpg?w=740&h=1024)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Fundido a blanco (dos retratos)' [Fade to White (Two Portraits)] 2010](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/fade-to-white-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Sedimentaciones' [Sedimentations] 2011](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sedimentaciones-web.jpg?w=840)

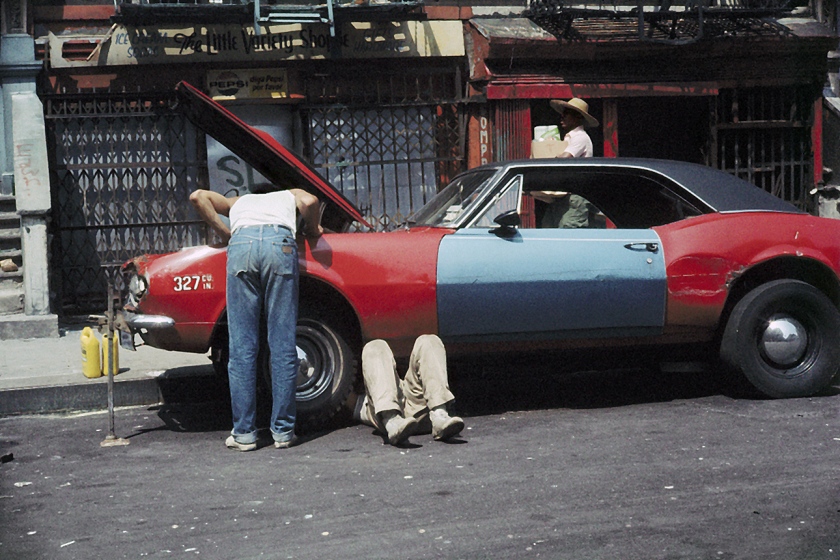

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-b-web.jpg?w=840)

![Oscar Muñoz. 'Línea del destino' [Line of Destiny] 2006](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/lc3adnea-del-destino-c-web.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.