Exhibition dates: 3rd June – 29th August 2021

Curator: Ramón Esparza (University of the Basque Country)

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

St. Paul’s Cathedral in the moonlight

1942

25.72 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Bill Brandt: master of photography, master of reinvention

“I’m 70% sure this was a reality not a dream”

In 12 years of writing this archive, this is the first chance I have had to assemble a posting and really think about the work of Bill Brandt, one of the most significant and inventive photographers of the 20th century. Brandt exhibitions are few and far between.

Son of a British father and German mother, Bill Brandt was born in Hamburg in 1904. As an adolescent he contracted tuberculosis and spent much of his youth in a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. In 1927 he travelled to Vienna, “to see a lung specialist and then decided to stay and find work in a photography studio. There, in 1928, he met and made a successful portrait of the poet Ezra Pound, who subsequently introduced Brandt to the American-born, Paris-based photographer Man Ray. Brandt arrived in Paris to begin three months of study as an apprentice at the Man Ray Studio in 1929 … his work from this time shows the influence of André Kertész and Eugène Atget, as well as Man Ray and the Surrealists.”1

“For any young photographer at that time, Paris was the centre of the world. Those were the exciting early days when the French poets and surrealists recognised the possibilities of photography.” ~ Bill Brandt

Having visited London in 1928, upon his return to London, in 1931, Brandt was well versed in the language of photographic modernism. In 1933 Brandt settled permanently in North London with his wife. With the rise of Nazism in Germany, Brandt Anglicised his name and disowned his German background and would claim he was born in South London. “He adopted Britain as his home and it became the subject of his greatest photographs.” Here is his first reinvention: the obfuscation of his German heritage, but he could not hide that heritage in his photographs.

As a photojournalist working for magazines such as News Chronicle, Weekly Illustrated, Lilliput, Harper’s Bazaar and Picture Post, Brandt documented all levels of British society. In his first book, The English at Home (1936), “comprising sixty-three photographs, Brandt traversed the country to make a pictorial survey of sorts, moving across the social classes, and between rural life and the urban city.”2 In the book Brandt pairs upper and lower class photographs across double page spreads, mixing joy (girl dancing in the street) with sobriety (the parlourmaids). As David Campany observes in his excellent writing on the artist, “There is nothing overtly angry or revolutionary in the generally restrained tone of Brandt’s book. However it was unusual in bringing different classes into one volume, leaving the viewer to reconcile the social contradictions and inequities.”3

“The extreme social contrast, during those years before the war, was, visually, very inspiring for me. I started by photographing in London, the West End, the suburbs, the slums.” ~ Bill Brandt

The book was not a success. Much like Robert Frank’s The Americans (published in France in 1958), another book by an émigré photographing as an outsider a foreign country, the British did not understand the book and probably did not like the mirror that was being held up to their society – much as the Americans hated Frank’s book for the pointed insights its probing images revealed of their fractured society, which had never been shown to them before. Campany notes, “In the 1930s Brandt was drawn to the rituals and customs of daily life, with what he saw as the deeply unconscious ways people inhabit their social roles and class positions. For him, to photograph these minutiae was not simply to document but to estrange through a heightened sense of atmosphere, theatrical artifice and a dreamlike sensibility. As an outsider he seemed to see English behaviour as bordering on passive automatism.”4

In the midst of the Great Depression of the 1930s, the photographs would have made the English feel very uncomfortable. Through their social commentary and poetic resonance, through their direct, modernist gaze and Surrealist dances (the women washing the blackened coal miner, a man sheltering in a coffin), Brandt squeezes (conflates?) documentary and art together, seeing the familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Through reinvention he recasts the very nature of his characters, finding out what else is essential in the photographs, challenging the viewer to understand the complexities of the image as it moves across time and from documentary to art. Often this left the viewer perplexed and grasping at the mystery, the unknown.

Other bodies of work and books followed. In 1937, Brandt visited the North of England for the first time, photographing the desperate plight of the poor scavenging for coal on the slag-heaps. In 1938 Brandt published A Night in London which was based on Paris de Nuit (1936) by Brassaï, photographing pubs, common lodging houses at night, theatres, Turkish baths, prisons and people in their bedrooms. By 1939, he was back in London, photographing the blackout and people sheltering from the Blitz in the London Underground.

“In 1939, at the beginning of the war, I was back in London photographing the blackout. The darkened town, lit only by moonlight, looked more beautiful than before or since.” ~ Bill Brandt

And so it went, on through Literary Britain (1951) which combined brooding, atmospheric landscapes and photographs of William Wordsworth’s room at Dove Cottage, Shaw’s Corner, Glamis Castle from Macbeth, and the scene of Oscar Wilde’s imprisonment at Reading Gaol opposite British poetry and prose; from the 1940s onwards, portraits of the notable and creative, made during the 1960s using a wide-angle lens; and perspectives on nudes made from 1944 onwards using a 1931 Kodak mahogany and brass camera with a wide-angle lens used by the police for crime scene records, which allowed him to see, he said, ‘like a mouse, a fish or a fly’.

“The nudes reveal Brandt’s intimate knowledge of the École de Paris – particularly Man Ray, Picasso, Matisse and Arp – together with his admiration for Henry Moore. He published Perspective of Nudes in 1961. It featured nudes in domestic interiors and studios, and on the beaches of East Sussex and northern and southern France. He used a Superwide Hasselblad for the beach photographs. In 1977-1978 Brandt added further nudes, published in Nudes, 1945-1980.”5

Through all of this there is the reinvention… reinvention of the portrait where the sitter is now part of the whole scenario (the surroundings), reinvention of the landscape where the landscape emerges from chthonic darkness, and reinvention of the nude where Brandt transplants Brassai’s Distortions into domestic interiors and exterior beaches – where the Surrealist, distorted, enigmatic fragment, like an ear or a big toe, comes to stand for the whole embedded in an alien landscape. Finally, there was the big reinvention in the 1960s, where Brandt began to reprint his earlier photojournalist images with a much harsher contrast (see various comparison images in this posting) in order to enhance their (Surrealist) art credentials and keep them relevant in an Abstract Expressionist, Pop Art world.

As David Campany states, “In the 1960s there were two major changes in his work and its reception. Both were related to his emerging position in art photography. He began to print his negatives much more harshly, sacrificing the mid-tones for more modish graphic blocks of black and white. The rich descriptive information in his negatives would be subsumed, even obliterated in his new aesthetic… While his latest photography was pursued more openly as art, notably his nudes (published as a book in 1960), his expressionism was released anew upon his earlier work. His books from the 1960s are printed with graphic extremes of black and white.”6

These are the images that are now famous, these graphic reinventions of the work and the Self. The reinvention of the old into the new. Through rethinking, recalculating and reimagining his old photographs and how they looked (“the way in which the artist interpreted a single negative had changed over time”), Brandt opened up his way of seeing and opened up new matter… ‘in rerum natura‘: in the nature of things; in the realm of actuality; in existence. Perhaps never before in the history of photography had the negative just been a step in the production of an ever changing image.

It was in the totality of this new work that his eloquent eye emerged. To me Brandt is like a Zen master. Whether it be socio-documentary, portrait, landscape or nude, it was his ability to focus on a particular subject at any one time – to concentrate on seeing subjects and ideas clearly – that became a hallmark of his later artistic creation. Through bodies of work that mix reality and dream the artist challenges straight photographic seeing in order for us to understand that enigmatic fragments can stand alone from each other while at the same time combining to make the whole. While A snicket in Halifax (1937, below) may not be present in Unemployed miner returning home from Jarrow (1937, below), it is when they combine that the circle is closed. It is in the entirety of his imaged (imagined) world, in the entirety of his vision, when all fragments combine, that Brandt emphasises that the whole of anything is greater than its parts.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ “Bill Brandt.” Introduction by Mitra Abbaspour, Associate Curator, Department of Photography, 2014 on the MoMA website Nd [Online] Cited 22/08/2021

2/ David Campany. “The Career of a Photographer, the Career of a Photograph – Bill Brandt’s Art of the Document,” on the David Company website [Online] Cited 10/06/2021. First published in the Tate Liverpool exhibition catalogue ‘Making History: Art and documentary in Britain from 1929-Now’, 2006

3/ Ibid.,

4/ Ibid.,

5/ Anonymous. “Bill Brandt Biography,” archived from the original on the V&A website Nd [Online] Cited 22/08/2021

6/ Campany, op cit.,

Many thankx to Fundación Mapfre for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Fundación MAPFRE is presenting the first retrospective in Spain on Bill Brandt (1904-1983), considered one of the most influential British artists of the 20th century. The exhibition brings together 186 photographs developed by Brandt himself who, over the course of five decades, made use of almost all the photographic genres: social documentary, portraiture, the nude and landscape.

“Each of Brandt’s well-known images aims for a tight formal organisation, its content given dramatic charge and dense psychological resonance. As documents they aim unapologetically to exceed visual description. In this sense what served him ill as a photojournalist was just what predisposed his images toward posterity via art. …

In the 1950s he continued to work professionally but concentrated on the more established genres of portraiture and landscape. In the 1960s there were two major changes in his work and its reception. Both were related to his emerging position in art photography. He began to print his negatives much more harshly, sacrificing the mid-tones for more modish graphic blocks of black and white. The rich descriptive information in his negatives would be subsumed, even obliterated in his new aesthetic. It was a technique that looked backward through German expressionist cinema to art photography’s Pictorialist preference for deep shadows and chiaroscuro, but it also connected with the emerging Pop sensibility.

While his latest photography was pursued more openly as art, notably his nudes (published as a book in 1960), his expressionism was released anew upon his earlier work. His books from the 1960s are printed with graphic extremes of black and white. …

The reprinting of Parlourmaid and under-parlourmaid ready to serve dinner was never too harsh. Brandt knew well that the force of this photograph resided in its details as much as its bold graphic organisation. Shadow of Light even improved on its past reproductions allowing new layers of meaning to emerge. …

While some meanings of Brandt’s photograph have been buried as the image has moved across time and from documentary to art, new meanings have come to the surface, meanings entirely dependent on art’s demand for superior qualities of reproduction.

As with many photographers who were discovered by a wider audience later in life, Brandt found himself regarded as a ‘figure from the past’ and as a contemporary artist at the same time. Layered on top of this was what looked like a shift from documentarist to artist. The reality, as always, was more complicated. At his best Brandt was a ‘documentary artist’ with all the paradoxes and interpretative difficulties that entails. There could never be any simple distinction between his artistry and his documentary description. The two are inextricable and give us no clear answers. And in the end these tensions are at the heart of his work and its success.”

David Campany. Extract from “The Career of a Photographer, the Career of a Photograph – Bill Brandt’s Art of the Document,” on the David Company website [Online] Cited 10/06/2021. First published in the Tate Liverpool exhibition catalogue ‘Making History: Art and documentary in Britain from 1929-Now’, 2006

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Death and the industrialist, Barcelona

1932

25.40 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

An apprentice in the studio of Man Ray and influenced in his origins by artists such as Brassaï, André Kertész or Eugène Atget, Bill Brandt (Hamburg, 1904 – London, 1983), one of the founders of modern photography, conceives the photographic language as a powerful means of contemplation and understanding of reality, but always from a primacy of aesthetic considerations over documentaries. Published in the press or in books, some of his photographs quickly became iconic pieces, indispensable to understanding mid-century English society.

His work also expresses a permanent attraction for the strange , for that which causes as much attraction as it is strange and causes unease. His aesthetics are thus close to the concept of “the sinister”, understood as something opposite to the idea of the familiar, of the usual. This element will act as a plot line for a professional and artistic production that, at first, seems erratic and dispersed.

His late work shows a more experimental facet, a search for innovation through cropping and framing, present above all in nude images.

The exhibition brings together 186 photographs made by Bill Brandt himself, who throughout the almost five decades of his career did not stop addressing any of the great genres of the photographic discipline: social reporting, portraiture, nude and landscape .

The tour, divided into six sections (“First photographs”, “Up and down”, “Portraits”, “Described landscapes”, “Nudes” and “In Praise of imperfection”), tries to show how all these aspects – in the that identity and the concept of “the sinister” become protagonists – they come together in the work of this eclectic artist who was considered, above all, a flâneur, a “stroller” in terms similar to those of his admired Eugene Atget, whom he always considered one of his teachers. One hundred and eighty-six photographs that are complemented by writings, some of his cameras and various documentation (among which the interview he gave to the BBC shortly before his death stands out), as well as illustrated publications of the time. All thanks to the courtesy of the Bill Brandt Archive in London and the Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York.

Four keys

Surrealist beginnings

After starting his foray into photography in Vienna, where he made the famous portrait of the poet Ezra Pound in 1928, Bill Brandt went to Paris to enter as an assistant, for a short period of time, in the studio of Man Ray, which prompted him to blend in with the surrealist atmosphere of the French capital, which will permeate all of his work from then on. This influence, together with that of his admiration for Eugène Atget, the photographer who documented “old Paris” and for whom Fundación MAPFRE also organised an exhibition in 2011, led to images where the disturbing was already making an appearance: street scenes and Parisian nights are some of the most frequent motifs in the artist’s images during this period.

Concealment of German heritage

Together with his partner and future wife, Eva Boros, he also made numerous trips to the Hungarian steppe, to his native Hamburg and to Spain, where they visited Madrid and Barcelona, before moving to London in 1934. It was in this city when Brandt got rid of his German roots, eliminating all reference to them, a concealment due to the growing animosity towards Germany that followed the rise of Nazism. Brandt invented a British birth, creating an artistic corpus in which the United Kingdom that is at the core of his identity.

The portrait

After having made several portraits in the early days of his career, starting in the 1940s – a period in which he worked for magazines such as Picture Post, Liliput and Harper’s Bazaar – Bill Brandt approached this genre in a professional way. Some of the portraits represented a break with tradition, such as those that appeared in the aforementioned Lilliput in 1941, illustrating the article “Young Poets of Democracy”, which included some of the most representative faces of the writers and poets of the Auden Generation.

In Praise of Imperfection

In his introduction to Camera in London, the book on the British capital published in 1948, Bill Brandt noted: ‘I consider it essential that the photographer make his own copies and enlargements. The final effect of the image depends to a large extent on these operations, and only the photographer knows what he intends. For the artist, work in the laboratory was essential and, at the beginning of his career, he learned a whole range of artisan techniques: from magnification to enlargement, the use of brushes, scrapers or other tools.’ This manual retouching sometimes gave his photographs that somewhat crude aspect that can be associated with the aforementioned Freudian concept of the “unheimlich”: the sinister.

Text from the Fundación Mapfre website translated from the Spanish by Google Translate

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Bond Street hatter’s show-case

1934

30.48 x 23.50cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg in 1904 to a wealthy family of Russian origin, after a period living in Vienna and Paris Brandt decided to settle in London in 1934. Within the context of growing hostility to all things German due to the rise of Nazism, he attempted to erase all traces of his origins to the point of stating that he was British by nationality. This concealment and the creation of a new personality enveloped Brandt’s life in an aura of mystery and conflict that is directly reflected in his works.

This aspect combines with the photographer’s interest in psychoanalysis, which he underwent during his youth in Vienna. A few years earlier, in 1919, Sigmund Freud had published the essay Das Unheimliche in which he analysed this term, which is generally translated as “the uncanny” in the sense of something that produces unease. Almost all Brandt’s photographs, both the pre-war social documentary type and those from his subsequent more “artistic” phase, possess a powerful poetic charge as well as that very typical aura of strangeness and mystery in which, as in his own life, reality and fiction are always mixed.

The structure of the exhibition, which is divided into six sections, reveals how all these qualities – in which identity and the concept of “the uncanny” become the principal ones – blend together in the work of this eclectic artist. Above all Brandt was considered a flâneur or stroller in a way comparable to his admired Eugène Atget, whom he always considered one of his masters. The exhibition also reveals the relationship between Brandt’s images and Dada and Surrealism. This interest is reflected in clear references to psychoanalytical issues, expressed through increasingly sombre tones and an obsession with collecting found objects.

The exhibition is completed with a range of documentation, a number of Brandt’s cameras and examples of the illustrated press of the period that published some of his most iconic images. All this has been made possible courtesy of the Bill Brandt Archive in London and the Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York.

Press release from the Fundación Mapfre website

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

East Durham coal-searchers

1937

25.24 x 20.16cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

East Durham coal-searchers near Henworth, 1937. Coal searchers on slag heap searching for bits of coal 1940s.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Coal-Miner’s Bath, Chester-le-Street, Durham

1937

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Bill Brandt

Considered one of the most influential British photographers of the 20th century and one of the artists who, together with Brassaï, Henri Cartier-Bresson and others, laid the foundations of modern photography, Bill Brandt’s oeuvre can be considered an eclectic one, reflecting a career of nearly five decades during which he encompassed almost all the photographic genres: social documentary, portraiture, the nude and landscape.

Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg in 1904 to a wealthy family of Russian origin, after a period living in Vienna and Paris Brandt decided to settle in London in 1934. Within the context of growing hostility to all things German due to the rise of Nazism, he attempted to erase all traces of his origins to the point of stating that he was British by nationality. This concealment and the creation of a new personality enveloped Brandt’s life in an aura of mystery and conflict that was directly reflected in his work. His images aim to construct a vision of the country that he embraced as his own, although not of the real country but rather of the idea that he had created of it during his childhood through reading and from stories told by relatives.

Brandt had tuberculosis as a child and it was seemingly in the Swiss sanatoriums at Agra and Davos where his family sent him to convalesce that he first became interested in photography. After some years in Switzerland he moved to Vienna to undergo an innovative treatment for tuberculosis based on psychoanalysis. Imbued with a post-Romantic air, Brandt’s photography always seems to be located on the edge, provoking simultaneous attraction and rejection. It can be related to the concept of unheimlich, a term first used by Sigmund Freud in 1919. The adjective unheimlich – generally translated as “the uncanny”, “the sinister” or “the disturbing”, and which according to Eugenio Trías “constitutes the condition and limit of the beautiful” – is one of the characteristic traits that remains present throughout Brandt’s career. Psychoanalytical theories were among the fundamental pillars of Surrealism and their influence extended to the entire Parisian cultural scene in the 1930s. Brandt and his first partner, Eva Boros, moved to the French capital in 1930 where he worked as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio. It was at this point that he assimilated the ideas circulating in a city filled with young artists, many of them immigrants looking to make their way in the professional art world. His images of this initial period suggest a catalogue of psychoanalytical “themes”, clearly reflecting the influence of Surrealism on him even though he never actively participated in any of the historic avant-garde groups.

Almost all Brandt’s images, both the pre-war social documentary type and those from his subsequent more “artistic” phase, possess a powerful poetic charge as well as that very typical aura of strangeness and mystery in which, as in his own life, reality and fiction are always combined.

Bill Brandt died in London in 1983.

Ramón Esparza, curator

Early photographs

Following his apprenticeship as a photographer in Vienna, Brandt left for Paris in order to work for a brief period as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio, an activity that allowed him to move in the city’s Surrealist circles. Nonetheless, his photographs of this period are closer to those of his admired Eugène Atget. Brandt followed Atget, becoming a stroller or flâneur whose images of Parisian nightlife and street scenes anticipate his subsequent work and possess an already palpable sense of unease.

Brandt and his partner Eva Boros travelled on numerous occasions to the Hungarian steppes, to his native Hamburg and to Spain, where they visited Madrid and Barcelona among other cities and with the plan of spending their holidays in Majorca before moving to London in 1934. It was in London that Brandt shed his German origins and created a body of work in which the United Kingdom – a country marked by significant social inequality at that time – established itself as the core of his identity.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Dressmaker’s dummy, Paris

1929

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

During his years in Paris Brandt established connections with the Surrealist circle and with groups of photographers who aimed to make the camera both a means of expression and of earning a living. He never followed the principal trends and focused his attention on the daily life of the suburbs rather than on events of the day. Brandt’s photographs of this period reveal how he increasingly assimilated Surrealist concepts into his way of seeing. This dressmaker’s dummy found on the street is a metaphor for the idea of the double. Other images from these years, such as the hot air balloon flying over the skies of Paris, allow his early work to be seen as a type of catalogue of the principal themes of Surrealism.

Upstairs downstairs

The growing antipathy on the part of the British towards Nazi Germany meant that many immigrants who had arrived from the latter country changed their name. Brandt went even further than this as he completely concealed his origins and for more than twenty-five years passed himself off as a British citizen.

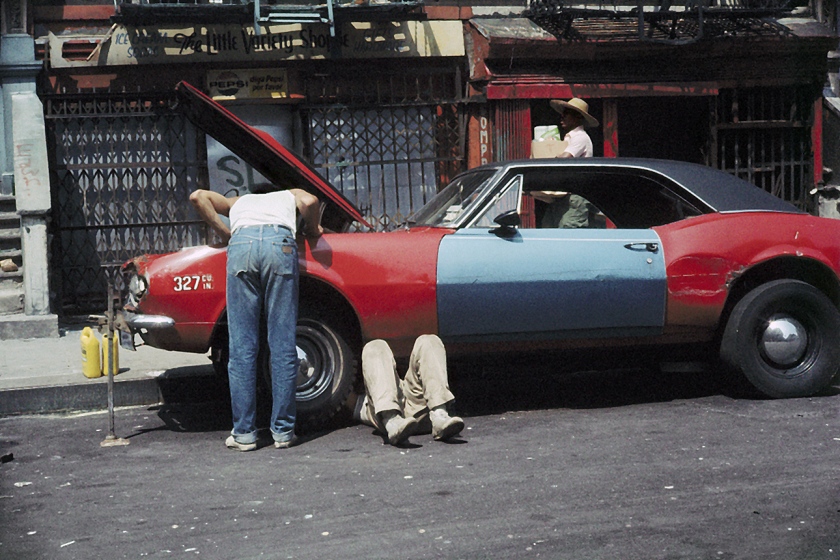

The 1930s was the decade of the great social protest movements and of strikes over working conditions following the 1929 financial crash. It was within this context that in 1936 Brandt published his first book, The English at Home, produced in a wide, album format. He employed a design particularly favoured by Central European graphic publications based on the combination of opposites in order to achieve a significant contrast between each pair of photographs. With these double-page spreads Brandt aimed to juxtapose two opposing social social classes, thus generating two parallel narrative discourses without mixing them together.

Following the outbreak of World War II Brandt started to work for the Ministry of Information. It was at this point that he produced two of his most famous series of images: his photographs of Londoners sleeping in Underground stations converted into improvised shelters; and his images of the city at ground level, showing a ghostly London lit only by the moon as protection against the air raids. Brandt abandoned the class differences that he had previously portrayed in favour of other types of scenes which denounced the effects of the war on the civilian population.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Couple in Peckham

1936

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Following in the wake of Brassaï and the success of his book Paris de nuit (1932), Brandt began to elaborate his own version of London at night. To do this he made regular use of friends and relatives who posed for him to create the scene he wished to photograph. In this case the “accosted” woman is his sister-in-law Ester Brandt and the man in the hat is his brother Rolf. The image allows for different interpretations but the reference to the genre of crime thrillers or simply to prostitution is clear.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Unemployed miner returning home from Jarrow

1937

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

The 1930s were economically harsh and politically turbulent years in Europe. The 1929 financial crash led the United Kingdom to close its mines and steelworks, resulting in unemployment rising to more than 2.5 million people. Activities such as collecting pieces of coal from mining waste on the beach became a way of life for many families. Brandt’s photograph shows one of these former miners, exhausted after an unproductive day’s labour and pushing his bicycle loaded with a sack of coal, the result of his efforts.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Parlourmaid and Under-parlourmaid ready to serve dinner

1933 printed later

23.81 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

This photograph was taken for a reportage published in Picture Post on 29 July 1939 with the title “The Perfect Parlourmaid” [but it never appeared in the Picture Post photo story of that name in July 1939]. Following his habitual practice, Brandt turned to his own family, in this case making use of his uncle Henry’s house. Pratt the parlourmaid waits in the dining room for the family members and their guests to be seated for dinner before starting to serve the food and attend the diners. This could be a classic image of social documentary photography except for the fact that Brandt very probably sat down at the table with the rest of the family after taking his shot. The image, however, reveals far more. The faces and poses of the two maids convey the difference between the gaze of the senior parlourmaid, which suggests both experience and assimilation of her social role, and that of her assistant, which seems to wander vaguely around the room.

“In his marvellous photograph the two house parlourmaids, prepared to wait at table, have eyes loaded like blunderbusses. Their starched caps and cuffs, their poker backs, mirror the terrible rectitude of learned attitudes. They have the same irritated loathing in defence of caste that shows in portraits of Evelyn Waugh.”

Mark Haworth-Booth cites Henderson in his introduction to the second edition of Brandt’s book Shadow of Light, Gordon Fraser, London 1977, p. 17.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Parlourmaid and Under-parlourmaid ready to serve dinner

1933

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

“… Brandt’s parlourmaids image is unusual in that something of those social contrasts is at play within its frame and so the image doesn’t lend itself to juxtaposition in the same way.

We see a dressed dinner table of a well-to-do household and the attendant women. The head parlourmaid seems at first glance to express a stern resentment mixed with weariness and professional discipline, but there is a kind of blankness about her too. Her junior has the vacant expression of an adolescent, not yet able to grasp the social forces that will shape her, perhaps. A reading of the image made by the photographer Nigel Henderson is similar but more pointed:

“In his marvellous photograph the two house parlourmaids, prepared to wait at table, have eyes loaded like blunderbusses. Their starched caps and cuffs, their poker backs, mirror the terrible rectitude of learned attitudes. They have the same irritated loathing in defence of caste that shows in portraits of Evelyn Waugh.”

Rhetorically, this is an image of doubles and differences. Its economy of form and content forces us to see in opposites, tapping into and reinforcing a general understanding of the social structures of class and service. It is as barbed as The English at Home gets. There is nothing overtly angry or revolutionary in the generally restrained tone of Brandt’s book. However it was unusual in bringing different classes into one volume, leaving the viewer to reconcile the social contradictions and inequities.”

David Campany. Extract from “The Career of a Photographer, the Career of a Photograph – Bill Brandt’s Art of the Document,” on the David Company website [Online] Cited 10/06/2021. First published in the Tate Liverpool exhibition catalogue Making History: Art and documentary in Britain from 1929-Now, 2006

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Sheltering in a Spitalfields crypt

1940

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Isidore Ducasse, who used the grandiloquent nom de plume of “the Comte de Lautréamont” for his poetic output, wrote one of the most frequently quoted definitions of Surrealist beauty: “As beautiful as the chance meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” Locating incongruence and transforming it into a work of art was one of Surrealism’s key strategies. By adding a dash of well-developed humour to this formula Brandt brought off the recipe with aplomb. At the height of the war, with German bombing raids nightly assailing a London whose inhabitants took shelter in the Underground and in basements, Bill Brandt photographed this man. Poor and working-class, to judge from his appearance, he is seen peacefully asleep in an open tomb in a crypt in clear defiance of death itself and of the terror it supposedly arouses.

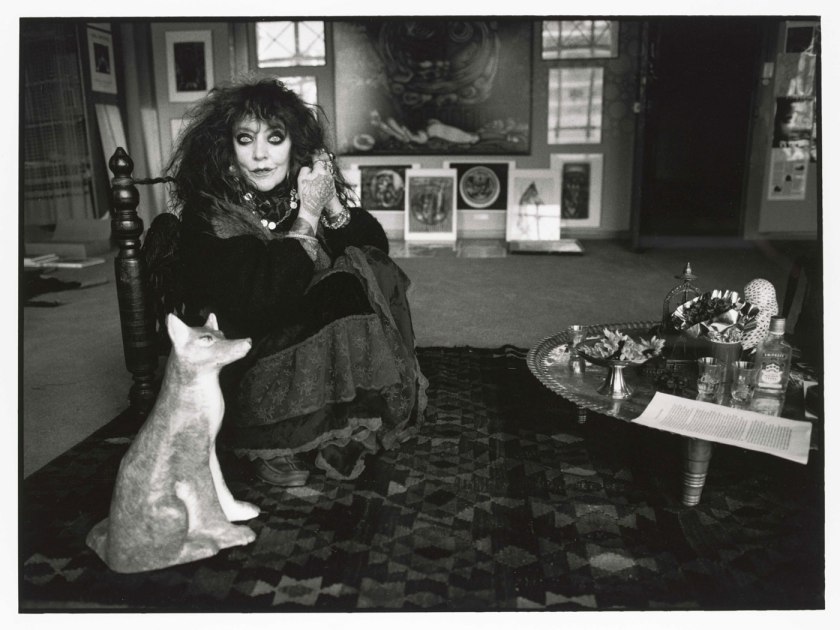

Portraits

As a portraitist, a genre to which he devoted himself professionally from 1943, Bill Brandt considered that the photographer’s aim should be that of capturing a “suspended” moment rather than just the appearance: “I think a good portrait ought to tell something about a subject’s past and suggest something about their future”; in other words, achieving an image that asks questions and raises issues about both the sitter and the viewer. Some of Brandt’s portraits mark a break from tradition, such as the ones published in the magazine Lilliput in 1941 to accompany the article “Young Poets of Democracy”, which includes images of some of the leading names of the Auden generation.

Brandt subsequently began to distort the space in his portraits, for example Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London (1963). He also produced a new series of portraits of eyes of clearly Surrealist inspiration. The eyes of Henry Moore, Georges Braque and Antoni Tàpies are among the examples of gazes that transformed the way of seeing and representing the world.

“I always take portraits in my sitter’s own surroundings. I concentrate very much on the picture as a whole and leave the sitter rather to himself. I hardly talk and barely look at him.” ~ Bill Brandt

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London

1963

25.40 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Brandt’s portraits evolved over time. Some mark a break with tradition, such as the images published in Lilliput in 1941 to accompany the article “Young Poets of Democracy”, which included some of the most famous faces of the writers and poets of the Auden generation. He subsequently began to distort the space in his images, as evident in Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London (1963), and also produced a new series of portraits of eyes of clearly Surrealist inspiration. The eyes of Henry Moore, Georges Braque and Antoni Tàpies are among the examples of gazes that transformed the way of seeing and representing the world.

One of several portraits of Francis Bacon by Brandt, here the photographer used the camera he had bought for his nudes on the beach. The notably wide angle lens, which produces a sense of space distorted in depth, and the chosen moment, just after sunset with the last light of day blending with the artificial light, give the scene a strange “atmosphere” (a term Brandt considered fundamental in his images). The familiar setting of an English park becomes disturbing with the dark sky, the curiously small and bent street light and Bacon, either indifferent or engaged, who turns his back on it all.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Henry Moore in his studio at Much Hadham, Hertfordshire

1946

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

The friendship and professional relations between Bill Brandt and the sculptors Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth was a lifelong one and they frequently collaborated. Moore accompanied Brandt on his visits to the night shelters in the London Underground and drew while his friend took photographs. Their work is being exhibited at The Hepworth Wakefield in 2020. The mutual influence between the two artists is evident in this portrait of Moore alongside one of his sculptures. The biomorphic forms that Moore has created from the wood recall those of Brandt’s nudes.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Graham Greene in his flat, St James’s Street, London

1948

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

The writer Graham Greene appears in this photograph next to a window which gives onto the interior courtyard of his London flat. Brandt, however, transformed a view of a simple courtyard into a type of labyrinth of lines in which it is difficult to discern what belongs to the window, what to the triangular shape located immediately next to Greene and what to the construction in the background. This confusion, the repetition of triangles and the mixture of lines can be seen as mimicking the author’s complex plots in his novels, while the harsh light that illuminates his face, falling from the upper right downwards, imbues his figure with a theatrical aura of mystery.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Georges Braque

1960

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

The eye of…

In the early 1960s Brandt embarked on a photographic series in which he reduced the sitter’s face to a foreground shot of one of the eyes. The subjects photographed in this manner were some of the leading visual artists of the day: Ernst, Braque, Vasarely, Moore, Tàpies, Arp, Dubuffet and Giacometti. The series aims to make the viewer reflect on the role of the gaze in art. Once the imperative of resemblance is rejected, what makes a painting powerful and interesting is the artist’s gaze, the way he or she has to look at and represent reality, or simply to produce a visible reality that does not refer to any other, as in the case of Victor Vasarely and Jean Arp. The camera, that glass eye which reflected the world in the 20th century, is used here to depict the instrument through which artists have seen and interpreted that world. To be exact, however, it should be acknowledged that both the camera and the eye are mere tools and that the essence of the process takes place “further back”, in the mind.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Jean Dubuffet

1960

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

This closely cropped eye belongs to the artist Jean Dubuffet. Brandt made ten photographs of notable visual artists; a few seem to have been taken at the same session as a published portrait, although none appear to be enlargements from other known works. They are striking departures from Brandt’s typical practice, mysterious despite their clarity of description, and they underscore the photographer’s experimental impulse, even late in his career. There is no record of their ever being published in a magazine.

MoMA gallery label from Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light, March 6 – August 12, 2013.

Landscapes described

Following his engagement with portraiture Brandt introduced landscape into his repertoire, thus encompassing all the categories traditionally considered to constitute the classic artistic genres. In his landscapes he aimed to introduce an atmosphere that connects with the viewer in order to provoke an emotional response from contemplation of the work. In this sense it would seem that Brandt did not merely aim to represent a place but to capture its very essence in a single image, as in Halifax; “Hail Hell & Halifax” (1937) and Cuckmere River (1963). When these landscapes started to include stone constructions such as tombs and crosses Brandt considered that he had achieved his aim: “Thus it was I found atmosphere to be the spell that charged the commonplace with beauty. … I only know it is a combination of elements … which reveals the subject as familiar and yet strange.”

It should be remembered that for Brandt the concept of landscape was deeply rooted in painting and the photographic tradition but also in literature. Literary Britain, which was published in 1951, makes this relationship clear. Brandt used images already published in other weekly magazines as well as photographs specially taken for this book, accompanying them with extracts from works by British authors.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Halifax; ‘Hail, Hell and Halifax’

1937

23.50 x 20.32cm

Bill Brandt Archive

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

In the social portrait that Brandt created of England in the 1930s the northern industrial cities made an inevitable appearance. Coal mining and steel production, both affected by a major crisis during this period, gave cities like Halifax and Newcastle a dark, sombre appearance which Brandt masterfully conveyed in his images. The photograph’s title refers to a verse from a popular 17th century poem by John Taylor: “From Hell, Hull and Halifax, Good Lord, deliver us!”, referring to the harshness of justice in those two cities.

The reputation of the great British documentary photographer Bill Brandt rests in large part on his capacity to manage the tension between black and white in a photograph. For Brandt, strong tonal contrast came to represent the social and cultural experience of Britain between the wars – a place of vast contrasts between rich and poor, worker and elite, urban and rural. But strong tonal contrast, and blackness in particular, carried other, more metaphysical associations. For Brandt, blackness represented the forces and mysteries at work in the world, a place of power and tragedy. Blackness in a photograph also introduced ‘a new beauty’ to the subject, one that intensified the visual and emotional experience of it.

Text © National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Gull’s nest, midsummer evening, Skye

1947

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Brandt saw this gull’s nest on a sunny afternoon during his trip to photograph northern Scotland. The light was too flat so he decided to return later. This was close to the time of year of the midnight sun. As Brandt wrote: “When I approached the nest on an isolated outpost of rocks, an enormously large gull which had been sitting on the eggs flew off and circled low around my head, barking like a dog. It was windstill, the mountains of the Scottish mainland were reflected in the sea – the light was now just right for the picture.”

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, London

1952

22.86 x 19.37cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Nudes

In 1944 Brandt returned to the theme of the nude. For the artist, documentary photography had become a widely extended fashion while the old Great Britain with its marked class divisions was now something of the past. It should also be remembered that the nude is one of the traditional themes of painting and as such signals Brandt’s evolution from documentary photography to the social status of “artist”.

In the 1950s he visited the French Channel Coast beaches in order to make a series of portraits of the painter Georges Braque. Seeing those pebble beaches led to a change of direction and he started to photograph stones and parts of the female body as if they were stones themselves. He combined flesh and rock, heat and cold, hardness and softness in a single formal discourse.

The distortions are often so pronounced that the parts of the body have lost any reference point but they nonetheless produce sensations that are more poetic or profound. It may be that for Brandt these “fragments” of the human body in comparison or communion with natural forms represented primordial forms of some type through which we can perceive “the totality of the world”, as with the Urformen of the Gestalt School and its theory of perception.

Brandt’s nudes of the late 1970s bear no relation to his earlier ones. They transmit a certain sense of violence which reveals the alienation of an artist who no longer felt himself part of the world in which he lived.

“Instead of photographing what I saw, I photographed what the camera was seeing. I interfered very little, and the lens produced anatomical images and shapes which my eyes had never observed.” ~ Bill Brandt

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, Campden Hill, London

1947

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

The Kodak camera that Brandt found in a second-hand shop near Covent Garden was designed to produce a clear image of an interior space without any major technical complications. It offered an unusual vision of the motif, creating a space that evokes a dreamlike mood. Most of Brandt’s photographs of nudes in interiors were taken with this old wooden camera which imbues the scene with a sensation of both beauty and disquiet. The repetition of specific visual elements such as windows, which are always in the background of the scene, half-open doors and different pieces of furniture, including the two chairs in this image, suggests issues such as absence, the desire to escape or a complex representation of desire stripped of the object (equivalent to reducing it to its most primary sense).

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, East Sussex coast

1959

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, East Sussex coast

1977

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

While walking on the Channel Coast beaches, Brandt’s attention was caught by the rounded forms of the rocks on the beach and their resemblance to some forms of the human body. This idea gave rise to his series of nudes photographed outdoors. For this project he abandoned his old Kodak plate camera in favour of a Hasselblad with a wide angle lens and his much used Rolleiflex. The formal interplay that he began to develop in this photograph is closely related to the constructivist nature of what the theoreticians of the Gestalt school (the German psychology movement which began to analyse the bases of human perception in the early 20th century) called Urformen or primordial forms. The combination of both elements, rock and flesh, hard and soft, produces a series of relationships that can be associated with Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth’s sculpture.

In Praise of Imperfection

In the introduction to Camera in London, his book on that city published in 1948, Brandt wrote: “I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants.”

For the artist, hands-on work in the photographic lab was essential for ensuring control over the final image, which in most cases was the stage prior to the publishing process when the image appeared in a book or magazine. At the outset of his career Brandt had learned a wide range of traditional techniques, including blow-up, enlarging and the use of brushes, scrapers and other tools.

These manual retouchings sometimes gave his photographs that rather crude look which can be associated with the above-mentioned Freudian concept of unheimlich or “sinister”. Many of them clearly show brushstrokes of black wash on the surface, for example At Charlie Brown’s, Limehouse (1946), displayed in this section of the exhibition.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

At Charlie Brown’s, Limehouse

1945/1946

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

At Charlie Brown’s, Limehouse

1945/1946

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

In the background of this image, taken in one of London’s East End pubs, is another one: a poster issued by the military Red Cross and referring to that organisation’s work on the battlefields during World War I. It is not known why, in the second version of the image, Brandt partly obscured the poster with black wash, the medium he most commonly used to retouch his photographs.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

A snicket in Halifax

1937

25.40 x 20.50cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

A snicket in Halifax

1937, printed later

25.40 x 20.50cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

In 1951 Brandt started to develop his photographs using a high contrast paper in order to obtain very dark and light zones in the same image. This led him to develop some of his best known images again, including A snicket in Halifax. In contrast to the earlier prints of that photograph, in which the details of the façade of the building on the left are perfectly visible, he now reinterpreted the image with the façade totally blackened and thus strongly contrasting with the glint on the ramp’s cobblestones while adding a plume of black smoke in the sky.

As early as 1997 Nigel Warburton, an art historian who has undertaken some of the best work on Brandt, questioned the concept of authenticity in this photograph in one of his texts, reflecting on the changes that Brandt had introduced in the prints of his images. Warburton asked which is the most “authentic”, emphasising the fact that the way in which the artist interpreted a single negative had changed over time and rejecting the idea that the simple distinction between what are known as “vintage” prints and later reprints resolves this issue.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, Vasterival, Normandy

1954

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, Vasterival, Normandy

1954

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

In contrast to photographic purists such as Edward Weston, Brandt had no objection to retouching his images, cropping them or reversing the negative in accordance with his preferences or to meet the requirements of its layout on the printed page. Here we see two versions of the same image with the negative flipped in the enlarger. This is not a unique case and there are other examples in the exhibition: Policeman in a dockland alley, Bermondsey was published in two versions, while Behind the restaurant is a photograph that was always printed in reverse, as evident from the lettering on the boxes.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Policeman in a Dockland Alley, Bermondsey

1934

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Top Withens, West Riding, Yorkshire

1944-1945

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

This photograph was included in Brandt’s book Literary Britain (1951) and he recalled how he visited the place various times in order to take it, considering it one of the settings that best conveyed the world of Emily Brontë’s works. The farm, now a ruin, is supposedly the place that inspired her novel Wuthering Heights.

For the painter David Hockney, a great admirer of Brandt, this was one of his favourite photographs but he was extremely disappointed to discover that it is in fact a composite image and that the storm filled clouds, which descend almost to the ground, were taken from another negative and added in the photography lab. The other photograph, taken from higher up on the hill, provides the reverse shot on a foggy winter day.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Top Withens, West Riding, Yorkshire

1944-1945

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Barmaid at the Crooked Billet, Tower Hill

March 1939

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd

Bill Brandt employed a wide range of retouching techniques on his prints, which was common practice in analogue photography, in which tiny scratches on the negative or specks of dust that cannot be completely removed leave marks on the photographic paper. In addition, Brandt often attempted to conceal imperfections in the individuals or objects photographed. The most widely used materials for this were watercolour, Conté crayon and even lead pencil. Brandt, however, also frequently used a scraper and Indian ink.

In this photograph the outline of the barmaid’s face, her eye and eyebrows have been reinforced with a metal point to define the lines, while the use of watercolour and Conté crayon allows various imperfections in the area of the left arm to be concealed.

Bill Brandt

Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt in Hamburg in 1904 to a wealthy family of Russian origin, after a period living in Vienna and Paris in 1934 Brandt decided to settle in London. Within the context of growing hostility to all things German due to the rise of Nazism, he attempted to erase all traces of his origins to the point of stating that he was British by nationality. This concealment and the creation of a new personality enveloped Brandt’s life in an aura of mystery and conflict that was directly reflected in his work. His images aim to construct a vision of the country that he embraced as his own, although not of the real country but rather of the idea that he had created of it during his childhood through reading and from stories told by relatives.

Brandt had tuberculosis as a child and it was seemingly in the Swiss sanatoriums at Agra and Davos where his family sent him to convalesce that he first became interested in photography and where he made many of his literary discoveries: Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Gustave Flaubert, Franz Kafka, Guy de Maupassant, Ernest Hemingway and Charles Dickens. After some years in Switzerland he moved to Vienna to undergo an innovative treatment for tuberculosis based on psychoanalysis. Imbued with a post-Romantic air, Brandt’s photographs always seems to be located on the edge, provoking simultaneous attraction and rejection.

As the exhibition’s curator Ramón Esparza has noted, they can be related to the concept of unheimlich, a term first used by Sigmund Freud in 1919. The adjective unheimlich – generally translated as “the uncanny”, “the sinister” or “the disturbing”, and which according to Eugenio Trías “constitutes the condition and limit of the beautiful” – is one of the characteristic traits that remains present throughout Brandt’s career. Psychoanalytical theories were one of the fundamental pillars of Surrealism and their influence extended to the entire Parisian cultural scene in the 1930s. Brandt and his first partner, Eva Boros, moved to the French capital in 1930 where he worked as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio. Without ever actively participating in any of the historic avant-garde movements, he undoubtedly assimilated the ideas that circulated in a city filled with young artists, many of them immigrants looking to make their way in the professional art world. Brandt’s images of this period suggest a catalogue of psychoanalytical “themes”, clearly reflecting the influence of Surrealism on him.

Almost all Brandt’s images, both the pre-war social documentary type and those from his subsequent more “artistic” phase, possess a powerful poetic charge as well as that very typical aura of strangeness and mystery in which, as in his own life, reality and fiction are always mixed.

The exhibition

Fundación MAPFRE is delighted to be presenting the first retrospective in Spain on Bill Brandt (Hamburg 1904 – London, 1983), considered one of the most influential British photographers of the 20th century. The exhibition, together with Paul Strand. Fundación MAPFRE Collections, inaugurates the KBr Fundación MAPFRE, our new Photography Centre in Barcelona.

The exhibition presents 186 photographs developed by Brandt himself who, over the course of nearly five decades of professional activity, encompassed almost all the principal photographic genres: reportage, portraiture, the nude and landscape, as noted by his biographer Paul Delany in Bill Brandt. A Life, 2004.

The structure of the exhibition, which is divided into six sections, reveals how all these qualities – in which identity and the concept of “the uncanny” become the principal ones – blend together in the work of this eclectic artist. Above all Brandt was considered a flâneur or stroller in a way comparable to his admired Eugène Atget, whom he always considered one of his masters.

The early photographs

After initiating his activities as a photographer in Vienna, where he produced the famous and widely praised portrait of the poet Ezra Pound in 1928, Bill Brandt left for Paris in order to work for a short period as an assistant in Man Ray’s studio. In the French capital Brandt encountered Surrealism, which would influence his work from that point onwards. Some of his images, such as Balloon flying over the northern suburbs of Paris (1929), can be related to the psychoanalytical theories of Freud, who considered a hot air balloon in a dream to be a symbol of the masculine. Brandt’s photographs of this period are also closely related to the earlier work of his admired Eugène Atget; like him, Brandt photographed street scenes and Parisian nightlife (images that precede his subsequent, better known work) in which the above-mentioned notion of the disturbing makes its appearance.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Evening in Kew Gardens

1932

25.24 x 20.48cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Brandt and his partner Eva Boros (another of Man Ray’s students who had previously studied with André Kertész) travelled on numerous occasions to the Hungarian steppes, to his native Hamburg and to Spain, where they visited Madrid and Barcelona among other cities and with the plan of spending their holidays in Majorca before moving to London in 1934. It was at this point that Brandt shed his German origins, even to the point of inventing British nationality for himself and creating a body of work in which the United Kingdom – a country marked by significant social inequality at that time – established itself as the core of his identity.

Upstairs, downstairs

“Bill Brandt was a man who loved secrets, and needed them. The face he presented to the world was that of an English-born gentleman, someone who could easily blend in with the racegoers at Ascot whom he liked to photograph. [A] façade which he would defend with outright lies if he had to […]. Today, many people are eager to discover their roots and make an identity from them. Brandt did the exact opposite: he buried his true origins and presented himself as a completely different person from the one he had been, in reality, for the first twenty-five years of his life.”

Paul Delany starts his biography of Bill Brandt with these lines. According to that author, Brandt not only wanted to live in England but to become English, which was understandable in the context of the growing British antipathy to Nazi Germany and to the events that followed Hitler’s rise to power and the outbreak of World War II. In the London art world it was habitual practice for emigrants arriving from Germany to change their name. Among those who had done so were Stefan Lorant, a Hungarian who had been the editor-in-chief of the Münchner Illustrierte Presse, and two of his photographers, Hans Baumann and Kurt Hübschmann, who anglicised their names to Felix Man and Kurt Hutton, just as Brandt changed his first name to Bill.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

East End girl dancing the ‘Lambeth Walk’

March 1939

22.86 x 19.68cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

In February 1936, two years after his arrival in London, Brandt published his first book, The English at Home. Despite their natural, spontaneous appearance, the scenes reproduced in the book were carefully prepared in advance. For this first book Brandt opted for a wide, album format and made use of one of the design formats most commonly employed in Central European graphic publications: the combination of opposites in order to create a significant contrast between each pair of photographs. Brandt aimed to juxtapose and counterbalance two different social classes on each double-page spread, developing two parallel narrative discourses but without mixing them together. We thus see family scenes of the upper classes out strolling or dining, followed by the same activities undertaken by working-class and mining families. Two years after the publication of The English at Home Brandt published A Night in London, which represents a type of replica of a work by Brassaï, one of the photographers he most admired, whose book Paris de nuit had appeared in France six years earlier. A Night in London can be seen as Brandt’s contribution to the photographic and cinematographic genre that some art historians have termed “the symphony of the metropolis.”

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Elephant & Castle Underground

1940

25.72 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Elephant and Castle underground station during WWII. 1942. Deep underground at Elephant and Castle Underground station, Bill Brandt photographed many hundreds sleeping as they sought shelter from the Blitz overhead.

Following the outbreak of World War II, Brandt started to work for the Ministry of Information, producing two of his most celebrated series. The first comprises photographs of hundreds of Londoners sleeping in Underground stations converted into improvised shelters, while the second portrays the city on the surface; a ghostly London lit only by moonlight as a safety precaution due to the air raids. The United Kingdom had become a single country united against the enemy. Brandt abandoned the class differences that he had previously portrayed in favour of other types of scenes which denounced the effects of the war on the civilian population.

Portraits

While Brandt produced photographs on an independent basis that he would subsequently group together for his different books, much of his output appeared in publications and magazines such as Picture Post, as well as in Lilliput and in the American edition of Harper’s Bazaar, for which he started to work in 1943. It was at this point that he turned to portraiture as a professional activity. His first reference to his portraits, of which more than 400 are known, was published in Lilliput in 1948. In Brandt’s words: “André Breton once said that a portrait should not only be an image but an oracle one questions, and that the photographer’s aim should be a profound likeness, which physically and morally predicts the subject’s entire future. […] The photographer has to wait until something between dreaming and action occurs in the expression of a face.”

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Francis Bacon

c. 1951

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

Brandt’s portraits evolved over time. Some mark a break with tradition, such as the images published in Lilliput in 1941 to accompany the article “Young Poets of Democracy”, which included some of the most famous faces of the writers and poets of the Auden generation. He subsequently began to distort the space in his images, as evident in Francis Bacon on Primrose Hill, London (1963), and also produced a new series of portraits of eyes of clearly Surrealist inspiration. The eyes of Henry Moore, Georges Braque and Antoni Tàpies are among the examples of gazes that transformed the way of seeing and representing the world.

Landscape described

Following his focus on portraiture, Brandt introduced landscape into his repertoire, thus encompassing all the categories traditionally considered to constitute the classic artistic genres. In his landscapes he aimed to introduce an atmosphere – a term that for Brandt seems to involve an entire series of aesthetic references associated with both the pictorial and the literary traditions – which connects with the viewer in order to provoke an emotional response from contemplation of the image. In this sense it would seem that Brandt did not aim to merely represent a place but to capture its very essence in a single image, as in Halifax; “Hail Hell & Halifax” (1937) and Cuckmere River (1963). When these landscapes started to include stone constructions such as tombs and crosses Brandt considered that he had achieved his aim of capturing the atmosphere.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Cuckmere River (Río Cuckmere)

1963

20 x 24.13cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

It should be remembered that for Brandt the concept of landscape was deeply rooted in painting and the photographic tradition but also in literature. Literary Britain, which was published in 1951, makes this relationship clear. Using images already published in other weekly magazines as well as photographs specially taken for this book, Brandt accompanied his photographs with extracts from works by British authors. It is here that an explanation of his somewhat imprecise concept of “atmosphere” can be found: the moment when the different elements that make up the landscape (nature, light, viewpoint, weather conditions) converge in an aesthetic canon rooted in a cultural tradition.

Nudes

When Brandt focused again on the theme of the nude in 1944 he seemed to feel the need to return to a more poetic type of image. For the artist, documentary photography had become a widely extended fashion while the old Great Britain with its marked class divisions was now something of the past. It should also be remembered that the nude is one of the traditional themes of painting and as such signals Brandt’s evolution from documentary photography to the social status of “artist”. For this transition he made use of an old plate camera with a lens that produced an effect of broad spatiality and depth, transforming the everyday space of a room into a dreamlike setting.

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Nude, Baie des Anges, France (Desnudo, Baie de Anges, Francia)

1959

25.24 x 20.32cm

Private collection

Courtesy Bill Brandt Archive and Edwynn Houk Gallery

© Bill Brandt / Bill Brandt Archive Ltd.

In the 1950s Brandt visited the beaches of Normandy in order to make a series of portraits of the painter Georges Braque. Seeing those pebble beaches led to a change of direction and he started to photograph stones and parts of the female body as if they were stones themselves. He combined flesh and rock, heat and cold, hardness and softness in a single formal discourse. The distortions are often so pronounced that the parts of the body have lost any reference point but they nonetheless produce sensations that are more poetic or profound. It may be that for Brandt these “fragments” of the human body in comparison or communion with natural forms represented primordial forms of some type through which we can perceive “the totality of the world”, as with the Urformen of the Gestalt School and its theory of perception.

In the late 1970s Brandt again returned to the theme of the nude but these images bear no relation to his earlier ones. They transmit a certain sense of violence which reveals the alienation of an artist who no longer felt himself part of the world in which he lived.

In Praise of Imperfection

In the introduction to Camera in London, his book on that city published in 1948, Brandt wrote: “I consider it essential that the photographer should do his own printing and enlarging. The final effect of the finished print depends so much on these operations. And only the photographer himself knows the effect he wants.” Brandt was far more concerned than many other photographs with the actual developing of his analogue photographs. He considered working in the photographic lab to be essential and he could spend hours there in order to ensure complete control over the final image, which in most cases was the stage prior to the publishing process when the image appeared in a book or magazine. At the outset of his career he had learned a wide range of traditional techniques, including blow-up, enlarging and the use of brushes, scrapers and other tools, as can be seen in the works displayed in the case in this room, which include various prints of the same image retouched in different ways. These manual retouchings sometimes gave his photographs that rather crude look which can be seen in the context of the above-mentioned Freudian concept of unheimlich or “the uncanny”. A large number of these images clearly show brushstrokes of black wash on the surface. Another example is Top Withens, West Riding, Yorkshire of 1945, an image taken for Brandt’s book Literary Britain. It includes clear signs that the stormy sky which gives the landscape a more threatening appearance was added later in the lab.

The catalogue

The catalogue that accompanies the exhibition includes reproductions of all the works on display, in addition to a principal essay by the project’s curator, Ramón Esparza, doctor of Communication Sciences and professor of Audiovisual Communication at the Universidad del País Vasco, and another by Maud de la Forterie, doctor in Art History at the Sorbonne, whose doctoral thesis was devoted to the work of Bill Brandt. The catalogue also features an essay by Nigel Warburton on the artist, originally published in 1993 and revised for the present edition, and Bill Brandt’s text “A Statement” which was published in the magazine Album in March 1970.

FUNDACIÓN MAPFRE – Instituto de Cultura

Paseo de Recoletos, 23

28004 Madrid, Spain

Phone: +34 915 81 61 00

Opening hours:

Monday (except holidays) from 2.00pm – 8.00pm

Tuesday to Saturday from 11am – 8pm

Sundays and holidays from 11am – 7pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.