Exhibition dates: 22nd May – 7th October 2018

Erich Salomon (German, 1886-1944)

(Portrait of Madame Vacarescu, Romanian Author and Deputy to the League of Nations, Geneva)

1928

Gelatin silver print

29.7 × 39.7cm (11 11/16 × 15 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In 1928, pioneering photojournalist, Erich Salomon photographed global leaders and delegates to a conference at the League for the German picture magazine Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. In a typically frank image, Salomon has shown Vacarescu with her head thrown back passionately pleading before the international assembly.

Elena Văcărescu or Hélène Vacaresco (September 21, 1864 in Bucharest – February 17, 1947 in Paris) was a Romanian-French aristocrat writer, twice a laureate of the Académie française. Văcărescu was the Substitute Delegate to the League of Nations from 1922 to 1924. She was a permanent delegate from 1925 to 1926. She was again a Substitute Delegate to the League of Nations from 1926 to 1938. She was the only woman to serve with the rank of ambassador (permanent delegate) in the history of the League of Nations.

Text from the Wikipedia website

From a distance…

For such an engaging subject, this presentation looks to be a bit of a lucky dip / ho hum / filler exhibition. You can’t make a definitive judgement from a few media images but looking at the exhibition checklist gives you a good idea of the overall organisation of the exhibition and its content. Even the press release seems unsure of itself, littered as it is with words like posits, probes, perhaps (3 times) and problematic.

Elements such as physiognomy are briefly mentioned (with no mention of its link to eugenics), as is the idea of the mask – but again no mention of how the pose is an affective mask, nor how the mask is linked to the carnivalesque. Or how photographs portray us as we would like to be seen (the ideal self) rather than the real self, and how this incongruence forms part of the formation of our identity as human beings.

The investigation could have been so deep in so many areas (for example the representation of women, children and others in a patriarchal social system through facial expression; the self-portrait as an expression of inner being; the photograph as evidence of the mirror stage of identity formation; and the photographs of “hysterical” women of the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris; and on and on…) but in 45 works, I think not. The subject deserved, even cried out for (as facial expressions go), a fuller, more in depth investigation.

For more reading please see my 2014 text Facile, Facies, Facticity which comments on the state of contemporary portrait photography and offers a possible way forward: a description of the states of the body and the air of the face through a subtle and constant art of the recovering of surfaces.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thanks to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The human face has been the subject of fascination for photographers since the medium’s inception. This exhibition includes posed portraits, physiognomic studies, anonymous snapshots, and unsuspecting countenances caught by the camera’s eye, offering a close-up look at the range of human stories that facial expressions – and photographs – can tell.

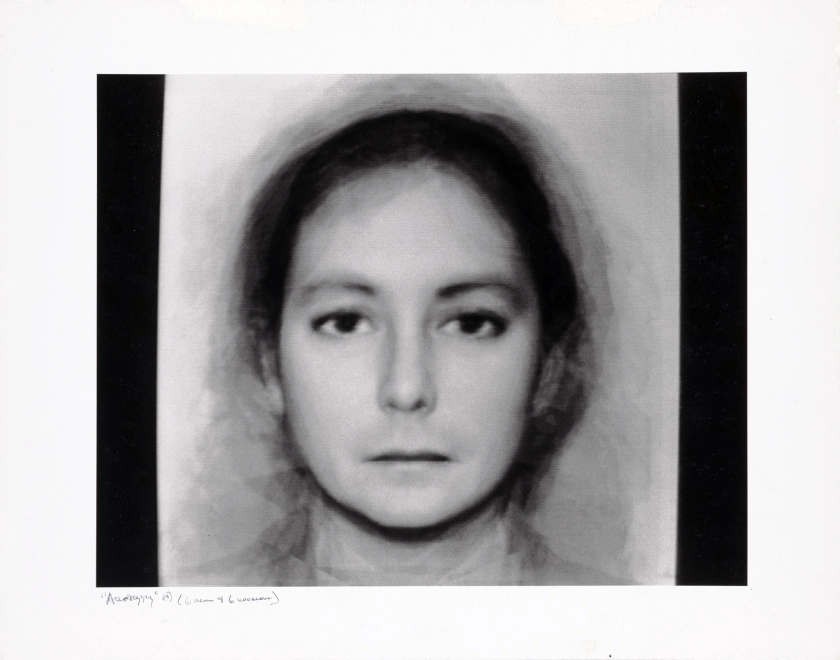

Nancy Burson (American, b. 1948)

Androgyny

1982

Gelatin silver print

21.6 × 27.7cm (8 1/2 × 10 7/8 in.)

© Nancy Burson

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Composite image of portraits of six men and six women

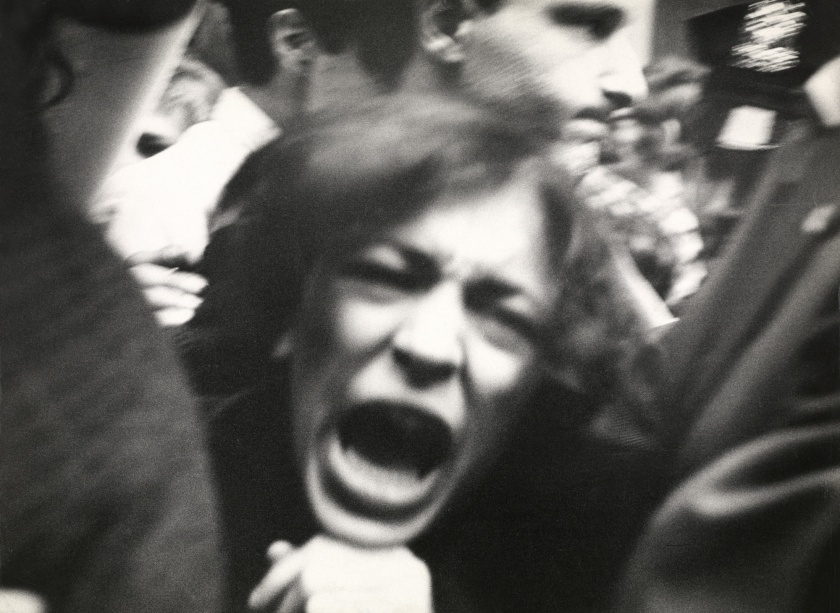

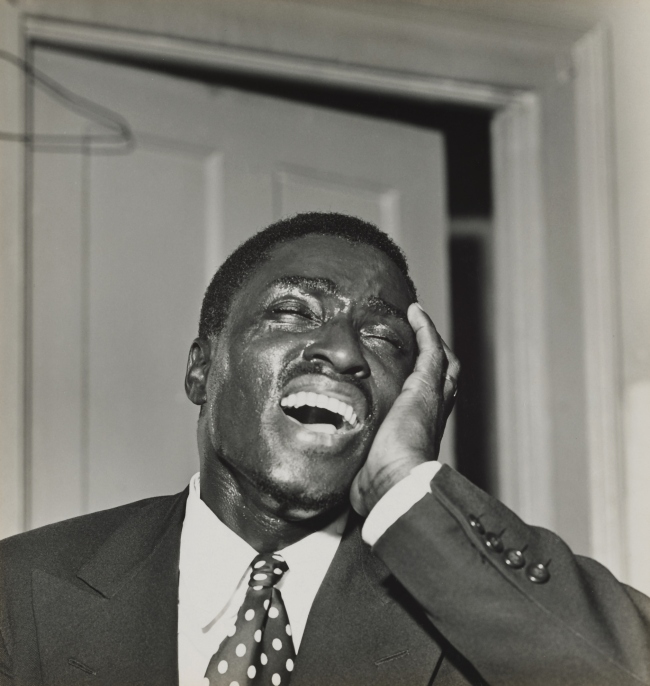

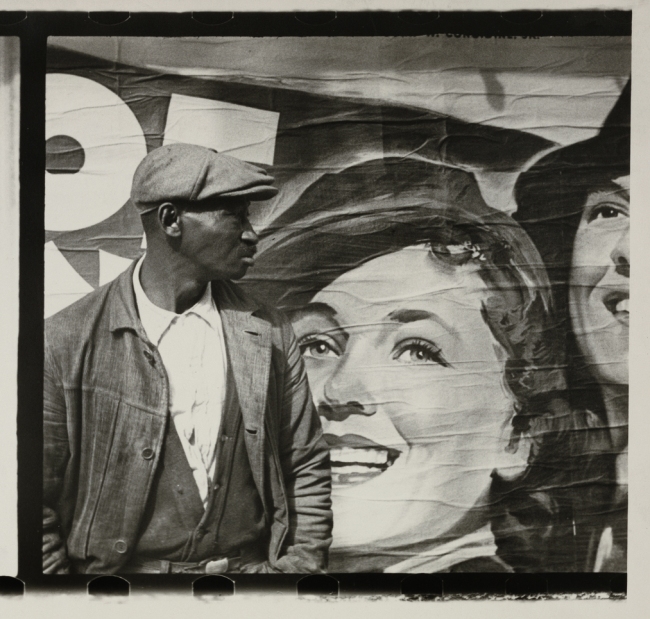

Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

Demonstration, New York City

1963

Gelatin silver print

25.9 × 35.4cm (10 3/16 × 13 15/16 in.)

© Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos, Inc.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of Brigitte and Elke Susannah Freed

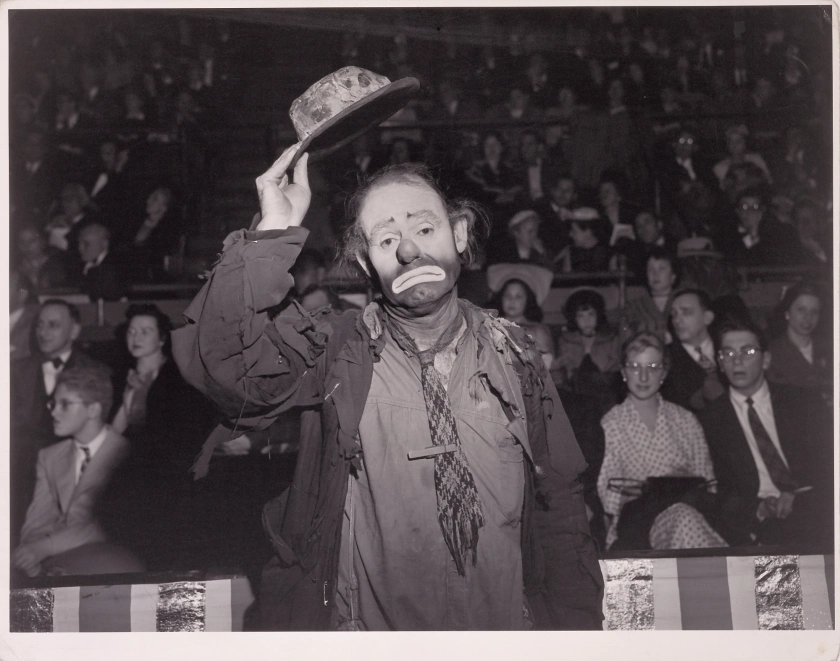

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American born Austria, 1899-1968)

Emmett Kelly, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus

Negative May 1943; print about 1950

Gelatin silver print

26 × 34.4cm (10 1/4 × 13 9/16 in.)

© International Center of Photography

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Emmett Leo Kelly (December 9, 1898 – March 28, 1979) was an American circus performer, who created the memorable clown figure “Weary Willie”, based on the hobos of the Depression era.

Kelly began his career as a trapeze artist. By 1923, Emmett Kelly was working his trapeze act with John Robinson’s circus when he met and married Eva Moore, another circus trapeze artist. They later performed together as the “Aerial Kellys” with Emmett still performing occasionally as a whiteface clown.

He started working as a clown full-time in 1931, and it was only after years of attempting to persuade the management that he was able to switch from a white face clown to the hobo clown that he had sketched ten years earlier while working as a cartoonist.

“Weary Willie” was a tragic figure: a clown, who could usually be seen sweeping up the circus rings after the other performers. He tried but failed to sweep up the pool of light of a spotlight. His routine was revolutionary at the time: traditionally, clowns wore white face and performed slapstick stunts intended to make people laugh. Kelly did perform stunts too – one of his most famous acts was trying to crack a peanut with a sledgehammer – but as a tramp, he also appealed to the sympathy of his audience.

From 1942-1956 Kelly performed with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, where he was a major attraction, though he took the 1956 season off to perform as the mascot for the Brooklyn Dodgers baseball team. He also landed a number of Broadway and film roles, including appearing as himself in his “Willie” persona in Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (1952). He also appeared in the Bertram Mills Circus.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Hill & Adamson (David Octavius Hill, Scottish 1802-1870 and Robert Adamson, Scottish 1821-1848) (Scottish, active 1843-1848)

Mrs Grace Ramsay and four unknown women

1843

Salter paper print from Calotype negative

15.2 x 20.3cm (6 x 8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Lewis W. Hine (American, 1874-1940)

Connecticut Newsgirls

c. 1912-1913

Gelatin silver print

11.8 × 16.8cm (4 11/16 × 6 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

(Mme Ernestine Nadar)

1880-1883

Albumen silver print

Image (irregular): 8.7 × 21cm (3 7/16 × 8 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Nadar (Gaspard Félix Tournachon) (French, 1820-1910)

(Mme Ernestine Nadar) (detail)

1880-1883

Albumen silver print

Image (irregular): 8.7 × 21cm (3 7/16 × 8 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879)

Ophelia

Negative 1875; print, 1900

Carbon print

35.2 x 27.6cm (13 7/8 x 19 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

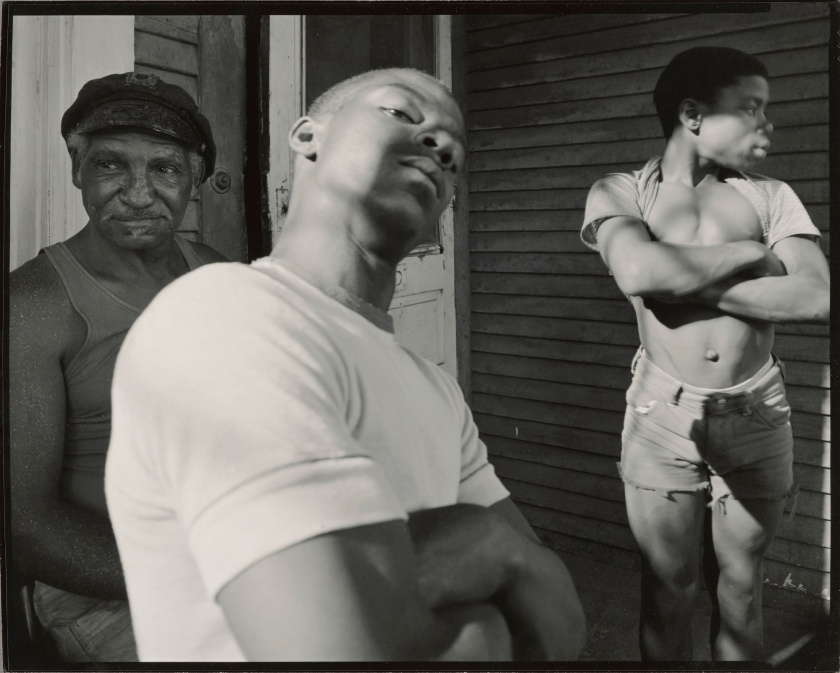

Nicholas Nixon (American, b. 1947)

W. Canfield Ave., Detroit

1982

Gelatin silver print

Image (irregular): 19.7 × 24.6cm (7 3/4 × 9 11/16 in.)

© Nicholas Nixon

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

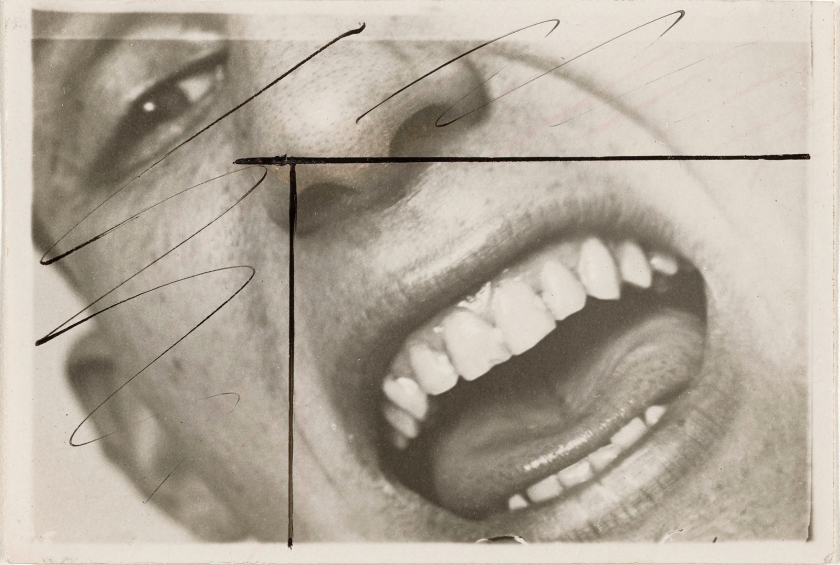

Unknown maker (German)

Close-up of Open Mouth of Male Student

c. 1927

Gelatin silver print

5.7 x 8.4cm (2 1/4 x 3 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Alec Soth (American, b. 1969)

Mary, Milwaukee, WI

2014

Inkjet print

40.1 × 53.5cm (15 13/16 × 21 1/16 in.)

© Alec Soth/Magnum Photos

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of Richard Lovett

Garry Winogrand (American, 1928-1984)

Los Angeles

January 1960

Gelatin silver print

22.6 × 33.9cm (8 7/8 × 13 3/8 in.)

© 1984 The Estate of Garry Winogrand

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

From Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, to Edvard Munch’s The Scream, to Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, the human face has been a crucial, if often enigmatic, element of portraiture. Featuring 45 works drawn from the Museum’s permanent collection, In Focus: Expressions, on view May 22 to October 7, 2018 at the J. Paul Getty Museum, addresses the enduring fascination with the human face and the range of countenances that photographers have captured from the birth of the medium to the present day.

The exhibition begins with the most universal and ubiquitous expression: the smile. Although today it is taken for granted that we should smile when posing for the camera, smiling was not the standard photographic expression until the 1880s with the availability of faster film and hand-held cameras. Smiling subjects began to appear more frequently as the advertising industry also reinforced the image of happy customers to an ever-widening audience who would purchase the products of a growing industrial economy. The smile became “the face of the brand,” gracing magazines, billboards, and today, digital and social platforms.

As is evident in the exhibition, the smile comes in all variations – the genuine, the smirk, the polite, the ironic – expressing a full spectrum of emotions that include benevolence, sarcasm, joy, malice, and sometimes even an intersection of two or more of these. In Milton Rogovin’s (American, 1909-2011) Storefront Churches, Buffalo (1958-1961), the expression of the preacher does not immediately register as a smile because the camera has captured a moment where his features – the opened mouth, exposed teeth, and raised face – could represent a number of activities: he could be in the middle of a song, preaching, or immersed in prayer. His corporeal gestures convey the message of his spirit, imbuing the black-and-white photograph with emotional colour. Like the other works included in this exhibition, this image posits the notion that facial expressions can elicit a myriad of sentiments and denote a range of inner emotions that transcend the capacity of words.

In Focus: Expressions also probes the role of the camera in capturing un-posed moments and expressions that would otherwise go unnoticed. In Alec Soth’s (American, born 1969) Mary, Milwaukee, WI (2014), a fleeting expression of laughter is materialised in such a way – head leaning back, mouth open – that could perhaps be misconstrued as a scream. The photograph provides a frank moment, one that confronts the viewer with its candidness and calls to mind today’s proliferation and brevity of memes, a contemporary, Internet-sustained visual phenomena in which images are deliberately parodied and altered at the same rate as they are spread.

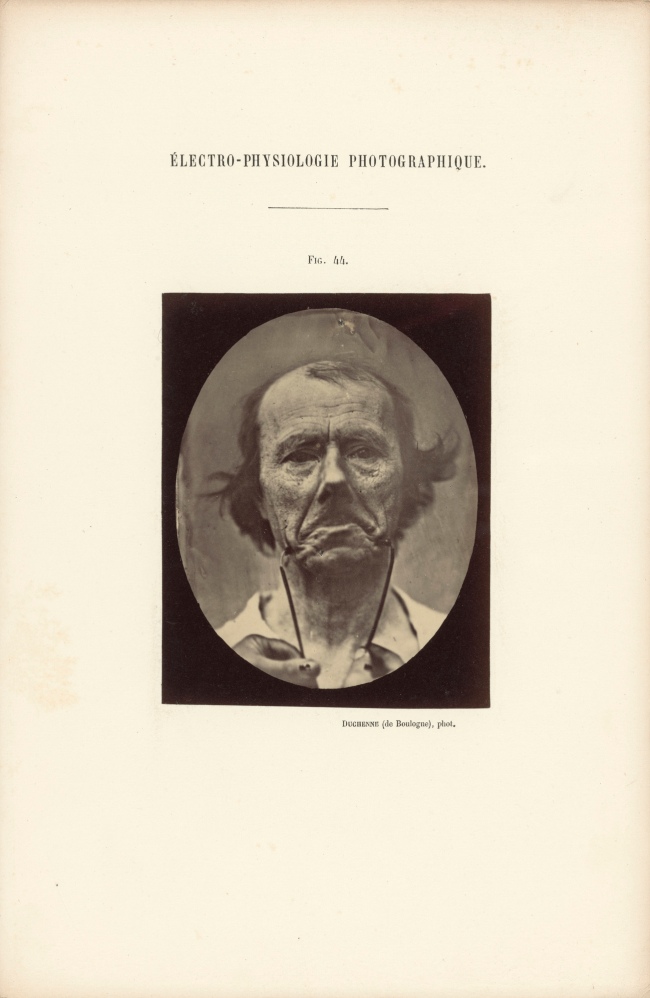

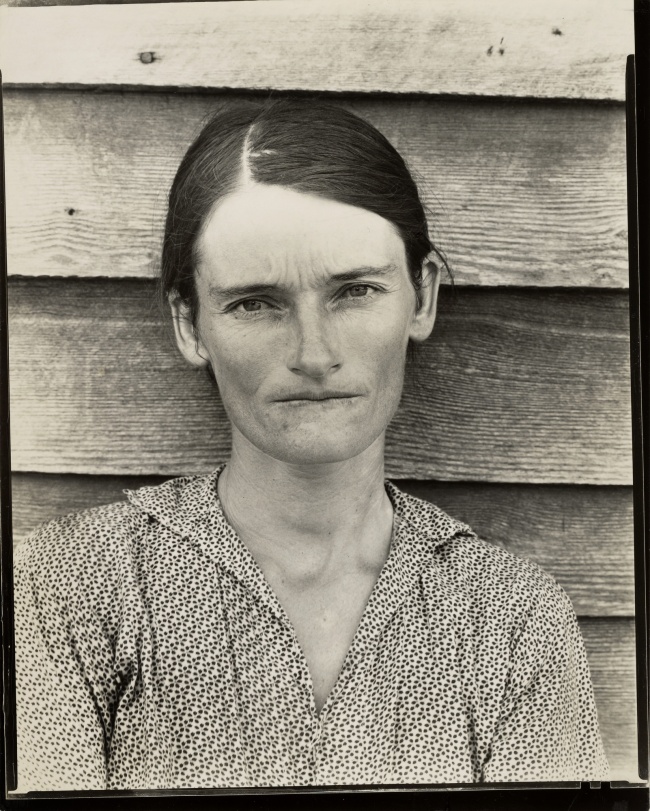

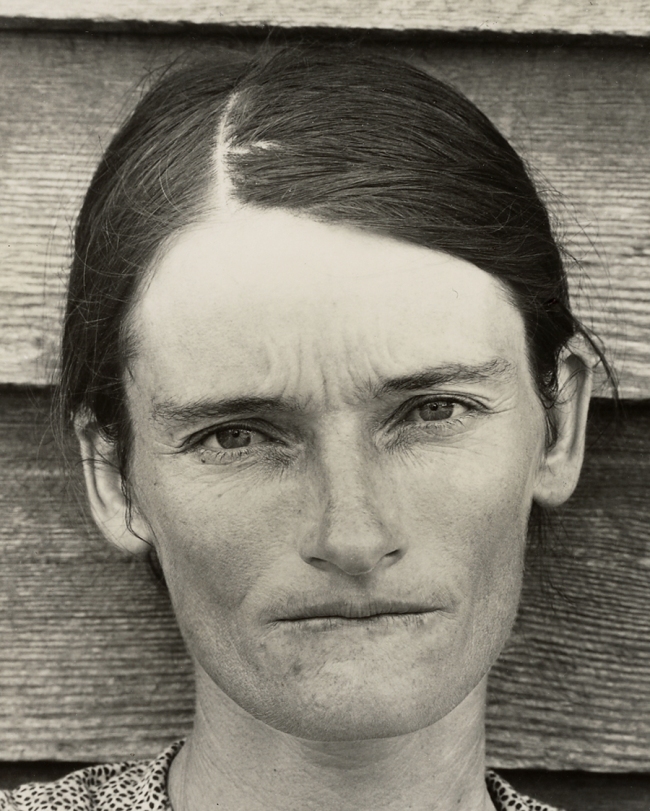

Perhaps equally radical as the introduction of candid photography is the problematic association of photography with facial expression and its adoption of physiognomy, a concept that was introduced in the 19th century. Physiognomy, the study of the link between the face and human psyche, resulted in the belief that different types of people could be classified by their visage. The exhibition includes some of the earliest uses of photography to record facial expression, as in Duchenne de Boulogne’s (French, 1806-1875) Figure 44: The Muscle of Sadness (negative, 1850s). This also resonates in the 20th-century photographs by Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975) of Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County Alabama (negative 1936) in that the subject’s expression could be deemed as suggestive of the current state of her mind. In this frame (in others she is viewed as smiling) she stares intently at the camera slightly biting her lip, perhaps alluding to uncertainty of what is to come for her and her family.

The subject of facial expression is also resonant with current developments in facial recognition technology. Nancy Burson (American, born 1948) created works such as Androgyny (6 Men + 6 Women) (1982), in which portraits of six men and six women were morphed together to convey the work’s title. Experimental and illustrative of the medium’s technological advancement, Burson’s photograph is pertinent to several features of today’s social media platforms, including the example in which a phone’s front camera scans a user’s face and facial filters are applied upon detection. Today, mobile phones and social media applications even support portrait mode options, offering an apprehension of the human face and highlighting its countenances with exceptional quality.

In addition to photography’s engagement with human expression, In Focus: Expressions examines the literal and figurative concept of the mask. Contrary to a candid photograph, the mask is the face we choose to present to the world. Weegee’s (Arthur Fellig’s) (American, born Austria, 1899-1968) Emmett Kelly, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus (about 1950) demonstrates this concept, projecting the character of a sad clown in place of his real identity as Emmett Kelly.

The mask also suggests guises, obscurity, and the freedom to pick and create a separate identity. W. Canfield Ave., Detroit (1982) by Nicholas Nixon (American, born 1947) demonstrates this redirection. Aware that he is being photographed, the subject seizes the opportunity to create a hardened expression that conveys him as distant, challenging, and fortified, highlighted by the opposing sentiments of the men who flank him. In return, the audience could be led to believe that this devised pose is a façade behind which a concealed and genuine identity exists.

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne (French, 1806-1875)

Figure 44, The Muscle of Sadness

Negative 1854-1856; print 1876

From the book Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine ou Analyse Electro-Physiologique de l’Expression des Passions

Albumen silver print

11 x 9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Duchenne de Boulogne (French, 1806-1875)

Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne (de Boulogne) (September 17, 1806 in Boulogne-sur-Mer – September 15, 1875 in Paris) was a French neurologist who revived Galvani’s research and greatly advanced the science of electrophysiology. The era of modern neurology developed from Duchenne’s understanding of neural pathways and his diagnostic innovations including deep tissue biopsy, nerve conduction tests (NCS), and clinical photography. This extraordinary range of activities (mostly in the Salpêtrière) was achieved against the background of a troubled personal life and a generally indifferent medical and scientific establishment.

Neurology did not exist in France before Duchenne and although many medical historians regard Jean-Martin Charcot as the father of the discipline, Charcot owed much to Duchenne, often acknowledging him as “mon maître en neurologie” (my teacher in neurology). … Duchenne’s monograph, the Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine – also illustrated prominently by his photographs – was the first study on the physiology of emotion and was highly influential on Darwin’s work on human evolution and emotional expression.

In 1835, Duchenne began experimenting with therapeutic “électropuncture” (a technique recently invented by François Magendie and Jean-Baptiste Sarlandière by which electric shock was administered beneath the skin with sharp electrodes to stimulate the muscles). After a brief and unhappy second marriage, Duchenne returned to Paris in 1842 in order to continue his medical research. Here, he did not achieve a senior hospital appointment, but supported himself with a small private medical practice, while daily visiting a number of teaching hospitals, including the Salpêtrière psychiatric centre. He developed a non-invasive technique of muscle stimulation that used faradic shock on the surface of the skin, which he called “électrisation localisée” and he published these experiments in his work, On Localized Electrization and its Application to Pathology and Therapy, first published in 1855. A pictorial supplement to the second edition, Album of Pathological Photographs (Album de Photographies Pathologiques) was published in 1862. A few months later, the first edition of his now much-discussed work, The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy, was published. Were it not for this small, but remarkable, work, his next publication, the result of nearly 20 years of study, Duchenne’s Physiology of Movements, his most important contribution to medical science, might well have gone unnoticed.

The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression

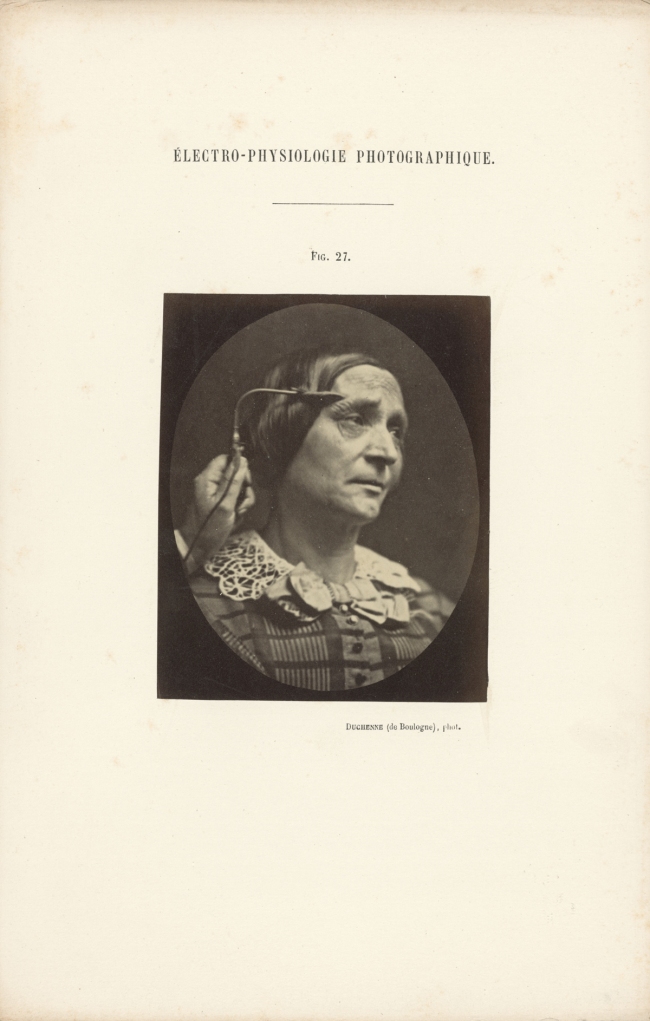

Influenced by the fashionable beliefs of physiognomy of the 19th century, Duchenne wanted to determine how the muscles in the human face produce facial expressions which he believed to be directly linked to the soul of man. He is known, in particular, for the way he triggered muscular contractions with electrical probes, recording the resulting distorted and often grotesque expressions with the recently invented camera. He published his findings in 1862, together with extraordinary photographs of the induced expressions, in the book Mecanisme de la physionomie Humaine (The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression, also known as The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy).

Duchenne believed that the human face was a kind of map, the features of which could be codified into universal taxonomies of mental states; he was convinced that the expressions of the human face were a gateway to the soul of man. Unlike Lavater and other physiognomists of the era, Duchenne was skeptical of the face’s ability to express moral character; rather he was convinced that it was through a reading of the expressions alone (known as pathognomy) which could reveal an “accurate rendering of the soul’s emotions”. He believed that he could observe and capture an “idealized naturalism” in a similar (and even improved) way to that observed in Greek art. It is these notions that he sought conclusively and scientifically to chart by his experiments and photography and it led to the publishing of The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy in 1862 (also entitled, The Electro-Physiological Analysis of the Expression of the Passions, Applicable to the Practice of the Plastic Arts. in French: Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine, ou Analyse électro-physiologique de l’expression des passions applicable à la pratique des arts plastiques), now generally rendered as The Mechanism of Human Facial Expression. The work compromises a volume of text divided into three parts:

1/ General Considerations,

2/ A Scientific Section, and

3/ An Aesthetic Section.

These sections were accompanied by an atlas of photographic plates. …

Duchenne defines the fundamental expressive gestures of the human face and associates each with a specific facial muscle or muscle group. He identifies thirteen primary emotions the expression of which is controlled by one or two muscles. He also isolates the precise contractions that result in each expression and separates them into two categories: partial and combined. To stimulate the facial muscles and capture these “idealized” expressions of his patients, Duchenne applied faradic shock through electrified metal probes pressed upon the surface of the various muscles of the face.

Duchenne was convinced that the “truth” of his pathognomic experiments could only be effectively rendered by photography, the subject’s expressions being too fleeting to be drawn or painted. “Only photography,” he writes, “as truthful as a mirror, could attain such desirable perfection.” He worked with a talented, young photographer, Adrien Tournachon, (the brother of Felix Nadar), and also taught himself the art in order to document his experiments. From an art-historical point of view, the Mechanism of Human Physiognomy was the first publication on the expression of human emotions to be illustrated with actual photographs. Photography had only recently been invented, and there was a widespread belief that this was a medium that could capture the “truth” of any situation in a way that other mediums were unable to do.

Duchenne used six living models in the scientific section, all but one of whom were his patients. His primary model, however, was an “old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality.” Through his experiments, Duchenne sought to capture the very “conditions that aesthetically constitute beauty.” He reiterated this in the aesthetic section of the book where he spoke of his desire to portray the “conditions of beauty: beauty of form associated with the exactness of the facial expression, pose and gesture.” Duchenne referred to these facial expressions as the “gymnastics of the soul”. He replied to criticisms of his use of the old man by arguing that “every face could become spiritually beautiful through the accurate rendering of his or her emotions”, and furthermore said that because the patient was suffering from an anesthetic condition of the face, he could experiment upon the muscles of his face without causing him pain.

Text from the Wikipedia website

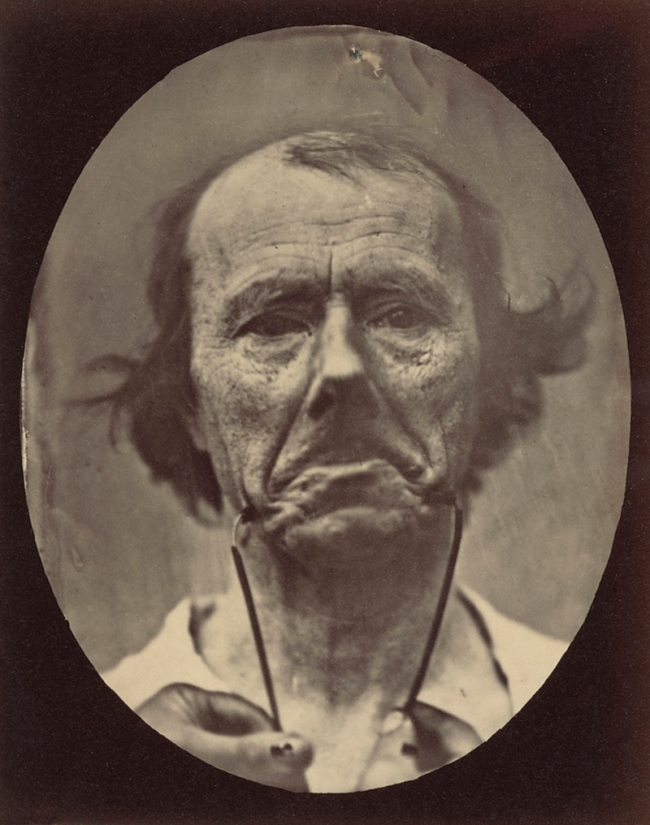

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne (French, 1806-1875)

Figure 44, The Muscle of Sadness (detail)

Negative 1854-1856; print 1876

From the book Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine ou Analyse Electro-Physiologique de l’Expression des Passions

Albumen silver print

11 x 9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Duchenne and his patient, an “old toothless man, with a thin face, whose features, without being absolutely ugly, approached ordinary triviality.” Duchenne faradize’s the mimetic muscles of “The Old Man.” The farad (symbol: F) is the SI derived unit of electrical capacitance, the ability of a body to store an electrical charge. It is named after the English physicist Michael Faraday

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne (French, 1806-1875)

Figure 27, The Muscle of Pain

Negative 1854-1856; print 1876

From the book Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine ou Analyse Electro-Physiologique de l’Expression des Passions

Albumen silver print

11 x 9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne (French, 1806-1875)

Figure 27, The Muscle of Pain (detail)

Negative 1854-1856; print 1876

From the book Mecanisme de la Physionomie Humaine ou Analyse Electro-Physiologique de l’Expression des Passions

Albumen silver print

11 x 9cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Milton Rogovin (American, 1909-2011)

Storefront Churches, Buffalo, preacher head in hand, eyes closed

1958-1961

Gelatin silver print

11 × 10.5cm (4 5/16 × 4 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of Dr. John V. and Laura M. Knaus

© Milton Rogovin

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama

Negative 1936; print 1950s

Gelatin silver print

24.3 × 19.2cm (9 9/16 × 7 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama (detail)

Negative 1936; print 1950s

Gelatin silver print

24.3 × 19.2cm (9 9/16 × 7 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Depression-era photography

In 1935, Evans spent two months at first on a fixed-term photographic campaign for the Resettlement Administration (RA) in West Virginia and Pennsylvania. From October on, he continued to do photographic work for the RA and later the Farm Security Administration (FSA), primarily in the Southern United States.

In the summer of 1936, while on leave from the FSA, he and writer James Agee were sent by Fortune magazine on assignment to Hale County, Alabama, for a story the magazine subsequently opted not to run. In 1941, Evans’s photographs and Agee’s text detailing the duo’s stay with three white tenant families in southern Alabama during the Great Depression were published as the groundbreaking book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Its detailed account of three farming families paints a deeply moving portrait of rural poverty. The critic Janet Malcolm notes that as in the earlier Beals’ book there was a contradiction between a kind of anguished dissonance in Agee’s prose and the quiet, magisterial beauty of Evans’s photographs of sharecroppers.

The three families headed by Bud Fields, Floyd Burroughs and Frank Tingle, lived in the Hale County town of Akron, Alabama, and the owners of the land on which the families worked told them that Evans and Agee were “Soviet agents,” although Allie Mae Burroughs, Floyd’s wife, recalled during later interviews her discounting that information. Evans’s photographs of the families made them icons of Depression-Era misery and poverty. In September 2005, Fortune revisited Hale County and the descendants of the three families for its 75th anniversary issue. Charles Burroughs, who was four years old when Evans and Agee visited the family, was “still angry” at them for not even sending the family a copy of the book; the son of Floyd Burroughs was also reportedly angry because the family was “cast in a light that they couldn’t do any better, that they were doomed, ignorant.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

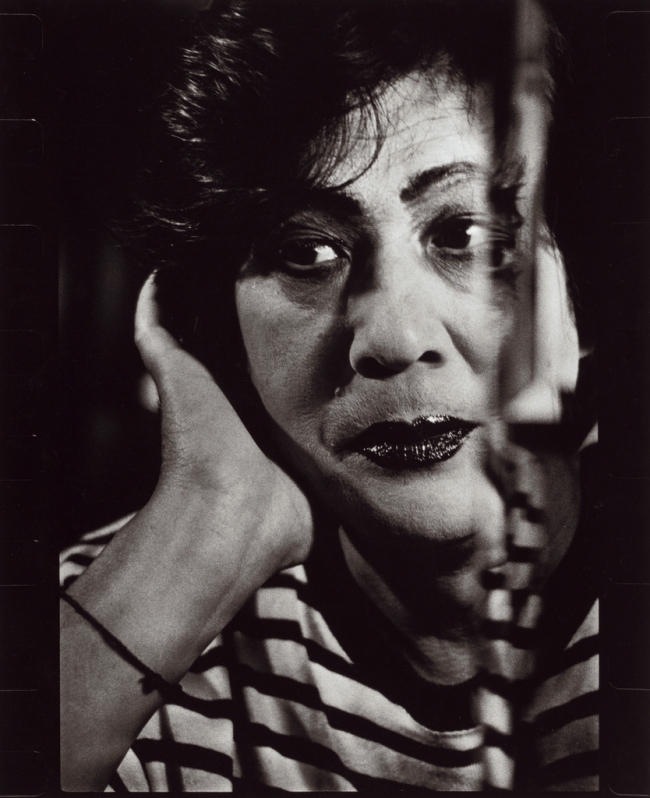

Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983)

(War Rally)

1942

Gelatin silver print

34.4 × 27.6cm (13 9/16 × 10 7/8 in.)

© Estate of Lisette Model

Courtesy Baudoin Lebon/Keitelman

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Robert Capa (American born Hungary, 1913-1954)

Second World War, Naples

October 2, 1943

Gelatin silver print

17.6 × 23.8cm (6 15/16 × 9 3/8 in.)

© International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

View of a group of woman with pained expressions on their faces with several holding handkerchiefs and one holding a card photograph of a young man.

Unknown maker (American)

(Smiling Man)

1860

Ambrotype

8.9 x 6.5cm

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

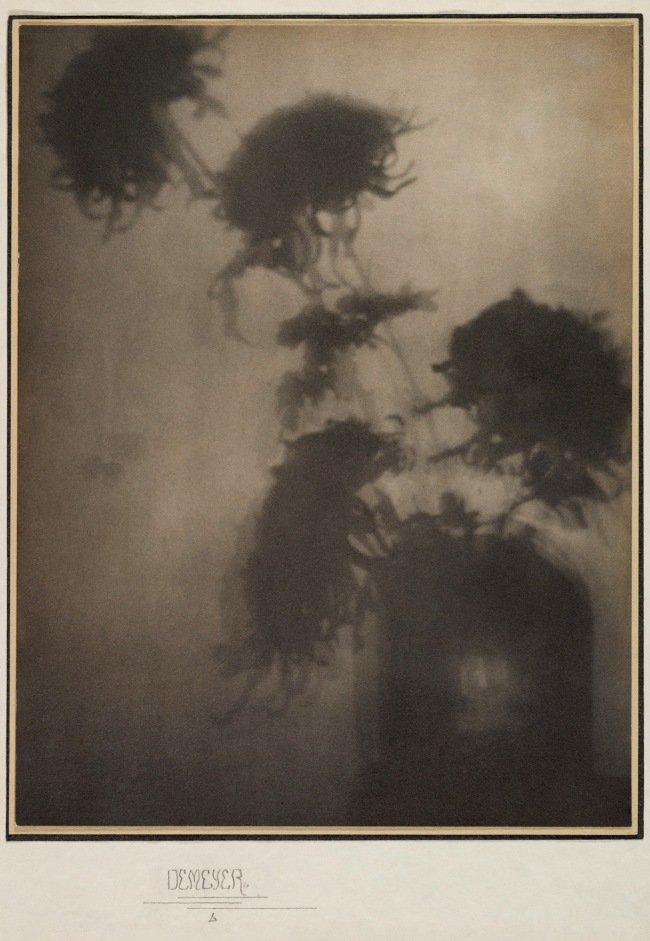

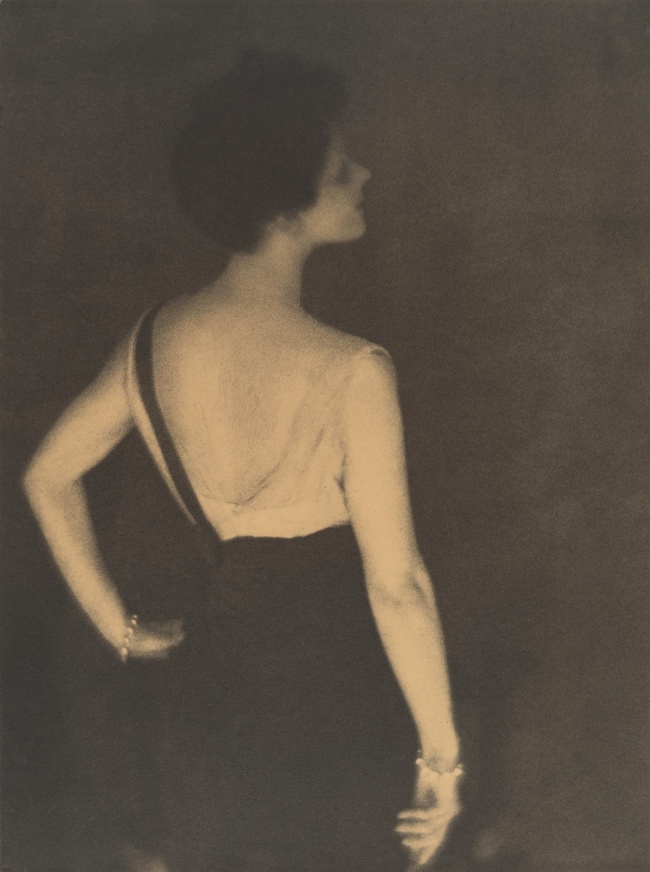

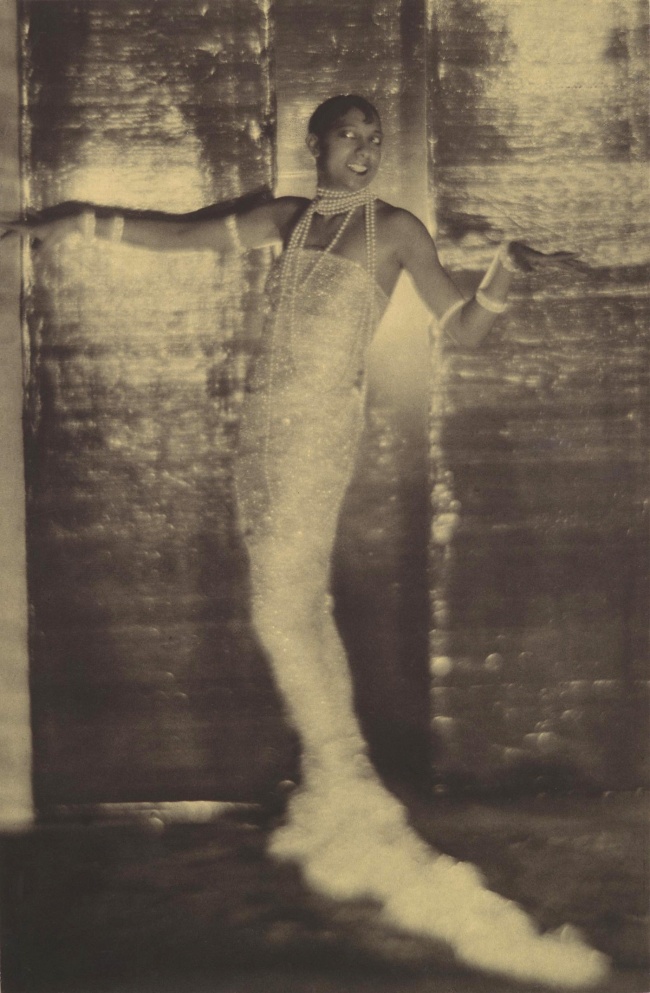

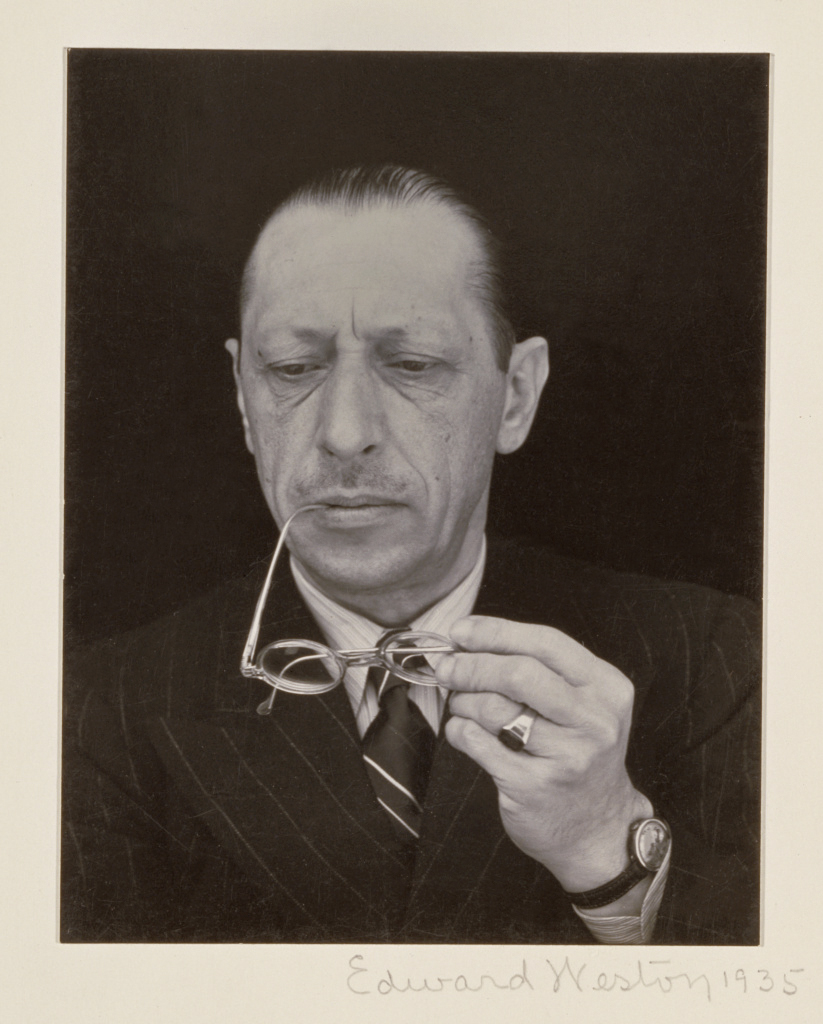

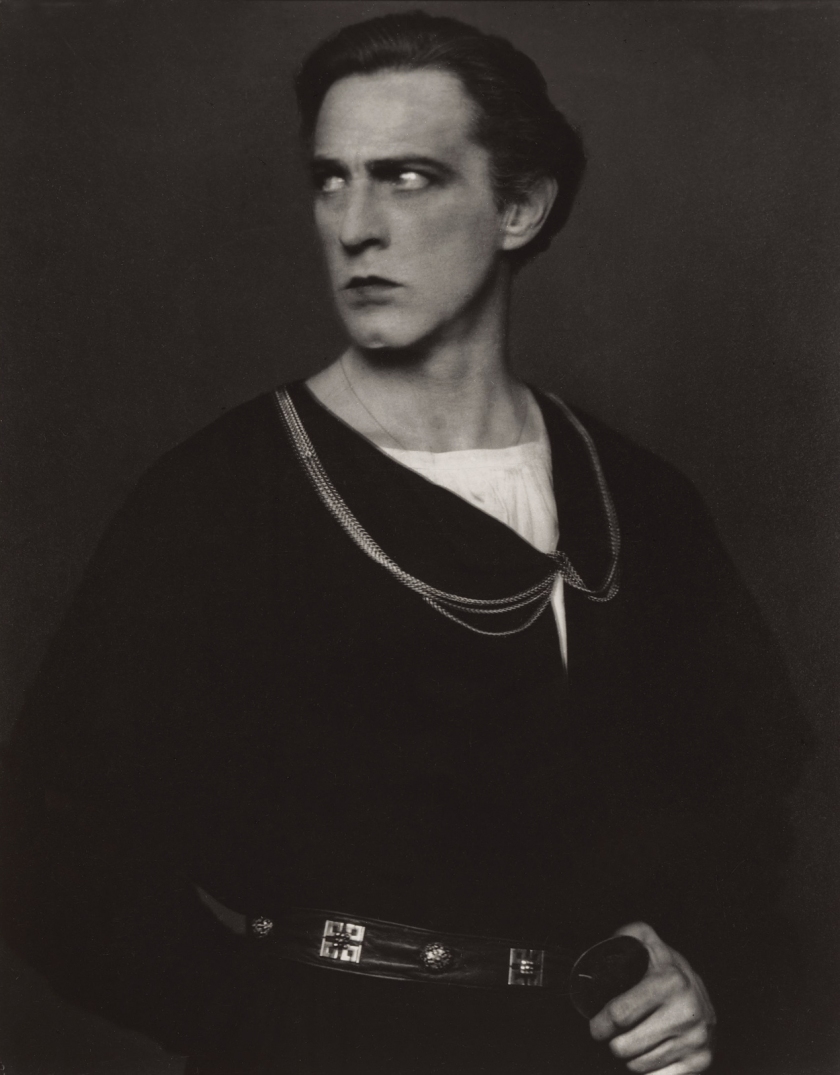

Baron Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946)

(Ruth St. Denis)

c. 1918

Platinum print

23.3 × 18.7cm (9 3/16 × 7 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

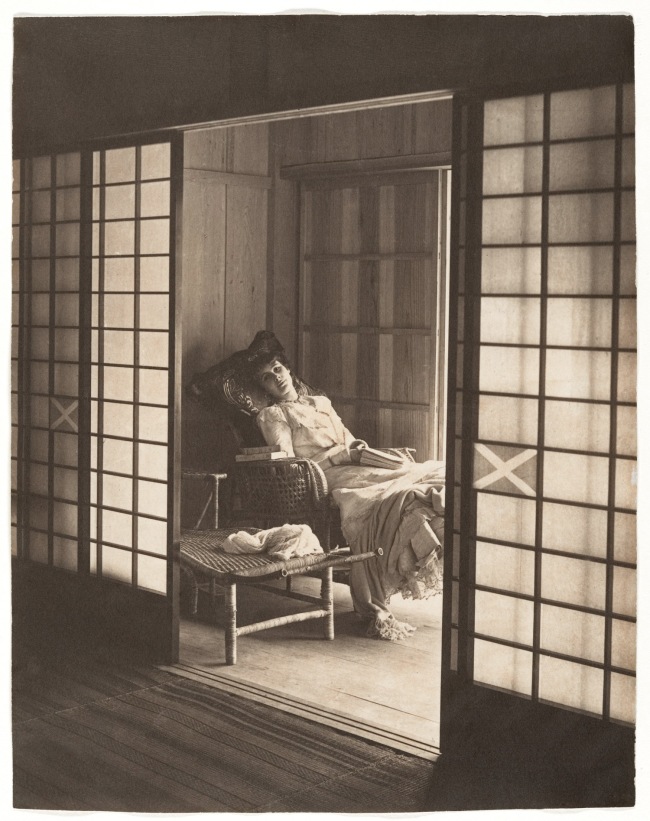

Woodbury & Page (British, active 1857-1908)

(Javanese woman seated with legs crossed, basket at side)

c. 1870

Albumen silver print

8.9 × 6cm (3 1/2 × 2 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Photography in Australia, the Far East, Java and London

In 1851 Woodbury, who had already become a professional photographer, went to Australia and soon found work in the engineering department of the Melbourne waterworks. He photographed the construction of ducts and other waterworks as well as various buildings in Melbourne. He received a medal for his photography in 1854.

At some point in the mid-1850s Woodbury met expatriate British photographer James Page. In 1857 the two left Melbourne and moved to Batavia (now Jakarta), Dutch East Indies, arriving 18 May 1857, and established the partnership of Woodbury & Page that same year.

During most of 1858 Woodbury & Page photographed in Central and East Java, producing large views of the ruined temples near Surakarta, amongst other subjects, before 1 September of that year. After their tour of Java, by 8 December 1858 Woodbury and Page had returned to Batavia.

In 1859 Woodbury returned to England to arrange a regular supplier of photographic materials for his photographic studio and he contracted the London firm Negretti and Zambra to market Woodbury & Page photographs in England.

Woodbury returned to Java in 1860 and during most of that year travelled with Page through Central and West Java along with Walter’s brother, Henry James Woodbury (born 1836 – died 1873), who had arrived in Batavia in April 1859.

On 18 March 1861 Woodbury & Page moved to new premises, also in Batavia, and the studio was renamed Photographisch Atelier van Walter Woodbury, also known as Atelier Woodbury. The firm sold portraits, views of Java, stereographs, cameras, lenses, photographic chemicals and other photographic supplies. These premises continued to be used until 1908, when the firm was dissolved.

In his career Woodbury produced topographic, ethnographic and especially portrait photographs. He photographed in Australia, Java, Sumatra, Borneo and London. Although individual photographers were rarely identified on Woodbury & Page photographs, between 1861 and 1862 Walter B. Woodbury occasionally stamped the mounts of his photographs: “Photographed by Walter Woodbury, Java.”

Text from the Wikipedia website

Weegee (Arthur Fellig) (American, 1899-1968)

The Critic

November 1943

Gelatin silver print

25.7 x 32.9cm (10 1/8 x 12 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

“I go around wearing rose-colored glasses. In other words, we have beauty. We have ugliness. Everybody likes beauty. But there is an ugliness…” ~ Weegee, in a July 11, 1945 interview for WEAF radio, New York City

While Weegee’s work appeared in many American newspapers and magazines, his methods would sometimes be considered ethically questionable by today’s journalistic standards. In this image, a drunk woman confronts two High Society women who are attending the opera. Mrs. George Washington Kavanaugh and Lady Decies appear nonplussed to be in close proximity to the disheveled woman. Weegee’s flash illuminates their fur wraps and tiaras, drawing them into the foreground. The drunk woman emerges from the shadows on the right side, her mouth tense and open as if she were saying something, hair tousled, her face considerably less sharp than those of her rich counterparts.

The Critic is the second name Weegee gave this photograph. He originally called it, The Fashionable People. In an interview, Weegee’s assistant, Louie Liotta later revealed that the picture was entirely set up. Weegee had asked Liotta to bring a regular from a bar in the Bowery section of Manhattan to the season’s opening of the Metropolitan Opera. Liotta complied. After getting the woman drunk, they positioned her near the red carpet, where Weegee readied his camera to capture the moment seen here.

Anonymous text. “The Critic,” on the J. Paul Getty Museum website [Online] Cited 24/02/2022

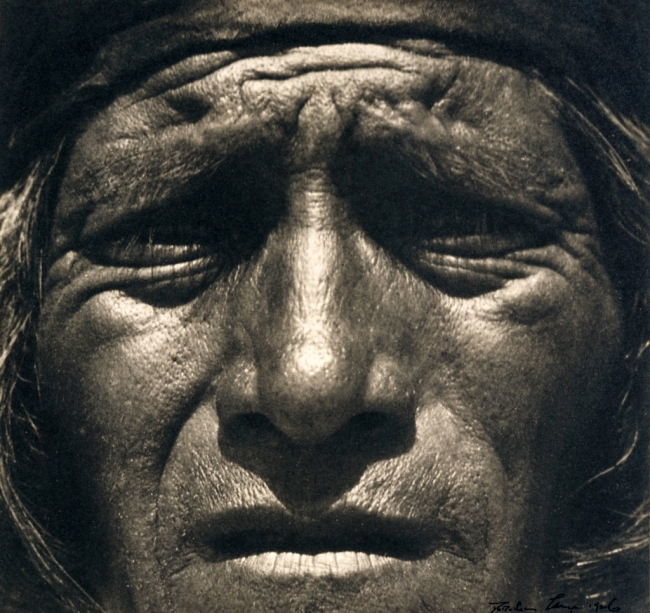

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Hopi Indian, New Mexico

Negative, c. 1923; print, 1926

Gelatin silver print

18.4 x 19.7cm (7 1/4 x 7 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Oakland Museum of California, the City of Oakland

Dorothea Lange made this portrait study not as a social document but rather as a Pictorialist experiment in light and shadow, transforming a character-filled face into an art-for-art’s-sake abstraction. This image bridges the two distinct phases of Lange’s work: her early, soft-focus portraiture and her better-known documentary work of the 1930s.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Street Scene, New Orleans

1936

Gelatin silver print

15.6 x 16.8cm (1 1/8 x 6 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

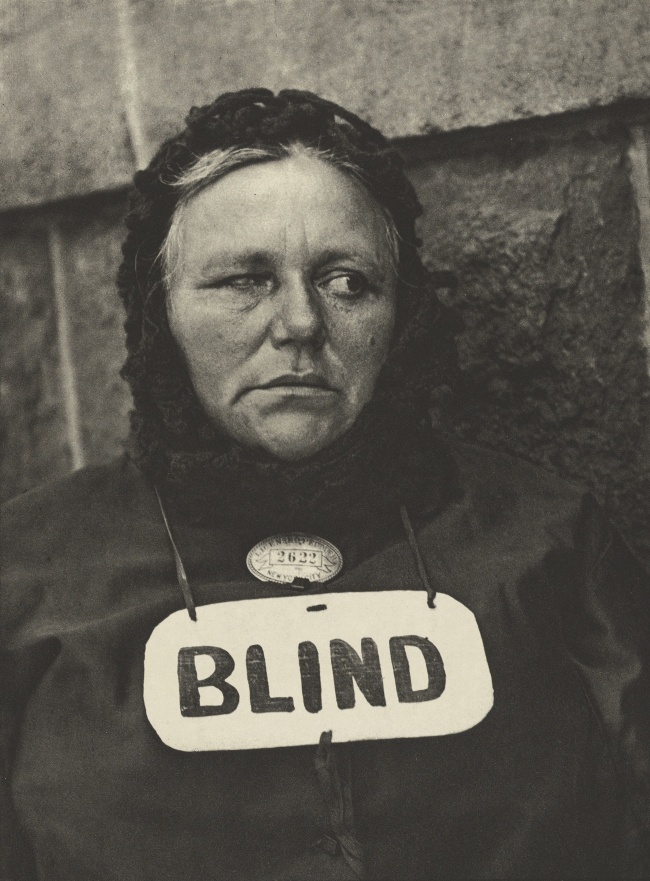

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Photograph – New York

Negative 1916; print June 1917

Photogravure

22.4 × 16.7cm (8 13/16 × 6 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

“I remember coming across Paul Strand’s ‘Blind Woman’ when I was very young, and that really bowled me over … It’s a very powerful picture. I saw it in the New York Public Library file of Camera Work, and I remember going out of there over stimulated: That’s the stuff, that’s the thing to do. It charged me up.” ~ Walker Evans

The impact of seeing this striking image for the first time is evident in Walker Evans’s vivid recollection. At the time, most photographers were choosing “pretty” subjects and creating fanciful atmospheric effects in the style of the Impressionists. Paul Strand’s unconventional subject and direct approach challenged assumptions about the medium.

At once depicting misery and endurance, struggle and degradation, Strand’s portrait of a blind woman sets up a complex confrontation. “The whole concept of blindness,” as one historian has noted, “is aimed like a weapon at those whose privilege of sight permits them to experience the picture. …”

Anonymous text. “New York [Blind Woman],” on the J. Paul Getty Museum website [Online] Cited 24/02/2022

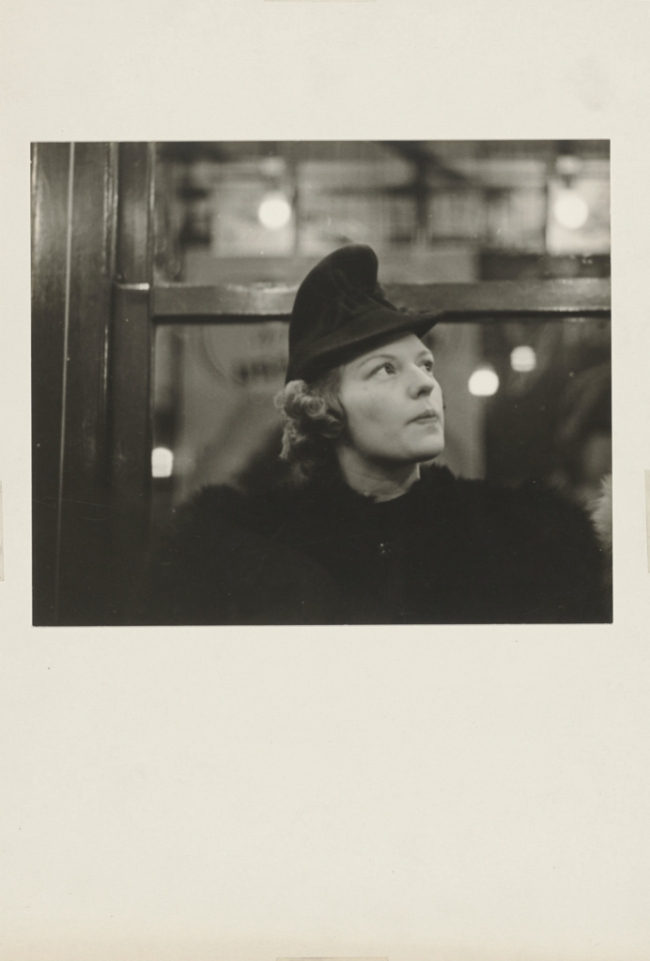

Walker Evans (American, 1903-1975)

Subway Portrait

1938-1941

Gelatin silver print

13.2 x 16cm (5 3/16 x 6 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

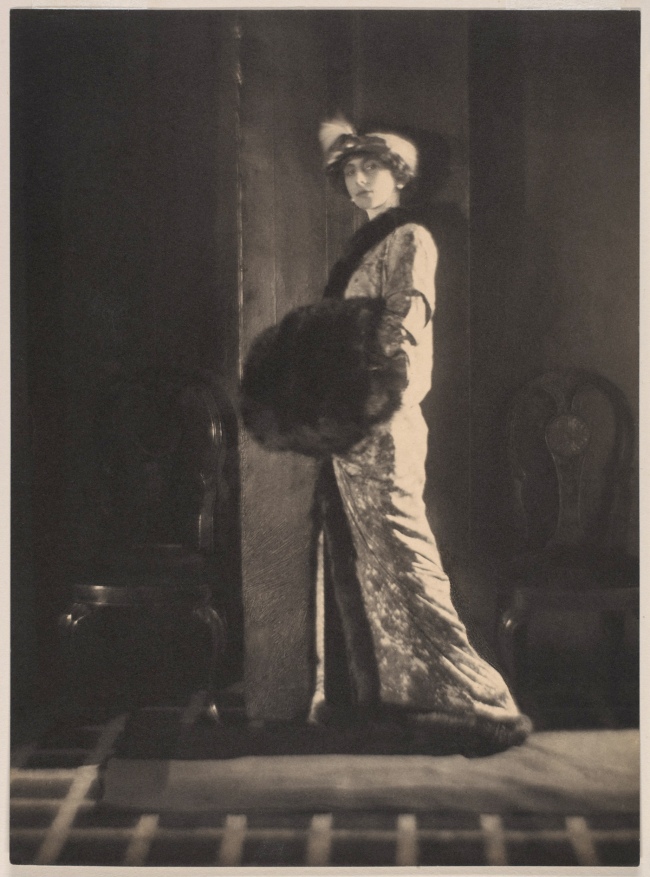

Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910)

(Madame Camille Silvy)

c. 1863

Albumen silver print

8.9 × 6cm (3 1/2 × 2 3/8 in.)

Gift in memory of Madame Camille Silvy born Alice Monnier from the Monnier Family

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Mikiko Hara (Japanese, b. 1967)

Untitled (Making a Void)

Negative 2001; print about 2007

Chromogenic print

© Mikiko Hara

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Purchased with funds provided by the Photographs Council

Lauren Greenfield (American, b. 1966)

Sisters Violeta, 21, and Massiel, 15, at the Limited in a mall, San Francisco, California

Negative 1999; print 2008

48.9 × 32.5cm (19 1/4 × 12 13/16 in.)

© Lauren Greenfield/INSTITUTE

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Daido Moriyama (Japanese, b. 1938)

Self-portrait

1997

Gelatin silver print

13.2 x 16cm (5 3/16 x 6 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Purchase with funds provided by the Photographs Council

© Daido Moriyama

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5.30pm

![Erich Salomon (German, 1886-1944) '[Portrait of Madame Vacarescu, Romanian Author and Deputy to the League of Nations, Geneva]' 1928 Erich Salomon (German, 1886-1944) '[Portrait of Madame Vacarescu, Romanian Author and Deputy to the League of Nations, Geneva]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/in-focus-expressions-1-web.jpg?w=840)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Mme Ernestine Nadar]' 1880-1883 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Mme Ernestine Nadar]' 1880-1883](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/in-focus-expressions-4-web.jpg?w=840)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Mme Ernestine Nadar]' 1880-1883 (detail) Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Mme Ernestine Nadar]' 1880-1883 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/in-focus-expressions-4-detail.jpg?w=650&h=873)

![Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983) '[War Rally]' 1942 Lisette Model (American born Austria, 1901-1983) '[War Rally]' 1942](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/in-focus-expressions-2-web.jpg?w=650&h=805)

![Unknown maker (American) '[Smiling Man]' 1860 Unknown maker (American) '[Smiling Man]' 1860](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/unknown-maker-smiling-man-1860-web.jpg?w=650&h=794)

![Baron Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Ruth St. Denis]' c. 1918 Baron Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Ruth St. Denis]' c. 1918](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/baron-adolf-de-meyer-ruth-st-denis-c-1918-web.jpg?w=650&h=956)

![Woodbury & Page (British, active 1857-1908) '[Javanese woman seated with legs crossed, basket at side]' c. 1870 Woodbury & Page (British, active 1857-1908) '[Javanese woman seated with legs crossed, basket at side]' c. 1870](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/woodbury-and-page-javanese-woman-web.jpg?w=650&h=1104)

![Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[Madame Camille Silvy]' c. 1863 Camille Silvy (French, 1834-1910) '[Madame Camille Silvy]' c. 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/camille-silvy-web.jpg?w=650&h=960)

![Mikiko Hara (Japanese, b. 1967) '[Untitled (Making a Void)]' Negative 2001; print about 2007 Mikiko Hara (Japanese, b. 1967) '[Untitled (Making a Void)]' Negative 2001; print about 2007](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/mikiko-hara-untitled-web.jpg?w=650&h=650)

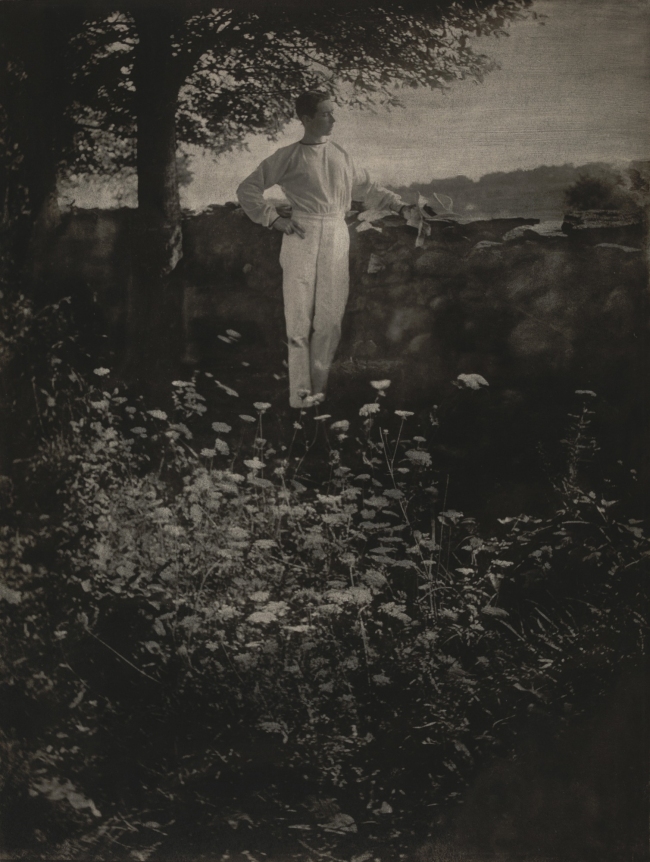

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Nude Models Posing for a Painting Class]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nude-models-posing-for-a-painting-class-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Adolf de Meyer Photographing Olga in a Garden]' 1890s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-photographing-olga-in-a-garden-web.jpg?w=840)

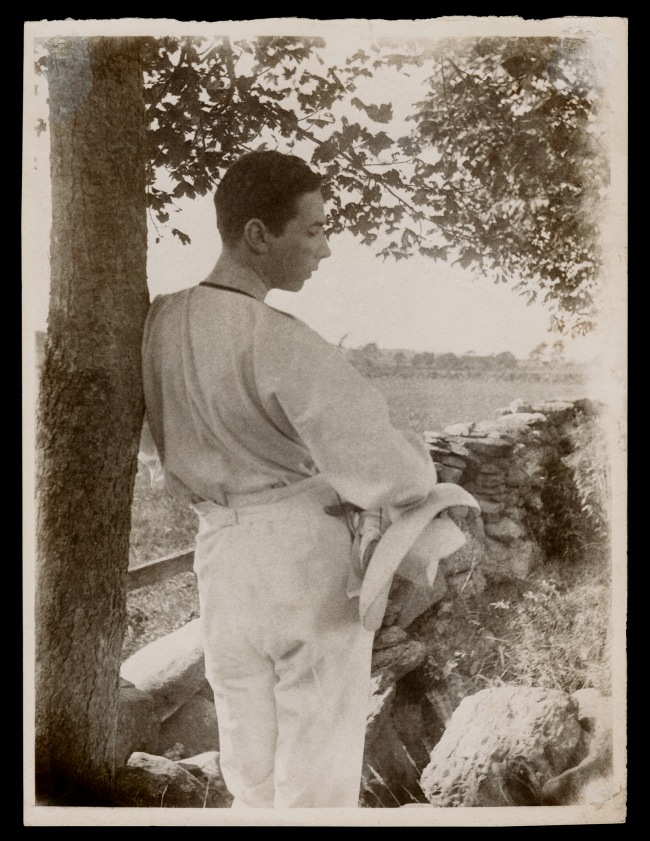

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Self-Portrait in India]' 1900 (detail)](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-self-portrait-in-india-detail.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Amida Buddah, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-amida-buddah-web.jpg?w=650&h=858)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[View Through the Window of a Garden, Japan]' 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-view-through-the-window-of-a-garden-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Lady Ottoline Morrell]' c. 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-lady-ottoline-morrell-web.jpg?w=650&h=871)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Dance Study]' c. 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-dance-study-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1912](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-portrait-of-vaslav-nijinski-1912-web.jpg?w=650&h=847)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Nijinsky [Plate from Le Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un Faune]' 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-nijinsky-plate-from-le-prelude-acc80-laprecc80s-midi-dun-faune-web.jpg?w=650&h=1045)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) '[Image from "Prelude à l'Après-Midi d'un faune"]' 1914](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-image-from-prelude-web.jpg?w=840)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Study for Vogue [Jan 1-1918, Betty Lee, Vogue, page 41]' 1918-1921](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-study-for-vogue-web.jpg?w=650&h=829)

![Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923 Adolf de Meyer (American born France, 1868-1946) 'Etienne de Beaumont [Count Etienne de Beaumont (French, 1883-1956)]' c. 1923](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/adolf-de-meyer-etienne-de-beaumont-web.jpg?w=650&h=824)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858-1935) 'A Mexican [Adolf de Meyer (American (born France), Paris 1868-1946 Los Angeles, California)]' 1905](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2018/02/sears-adolf-de-meyer-web.jpg?w=650&h=824)

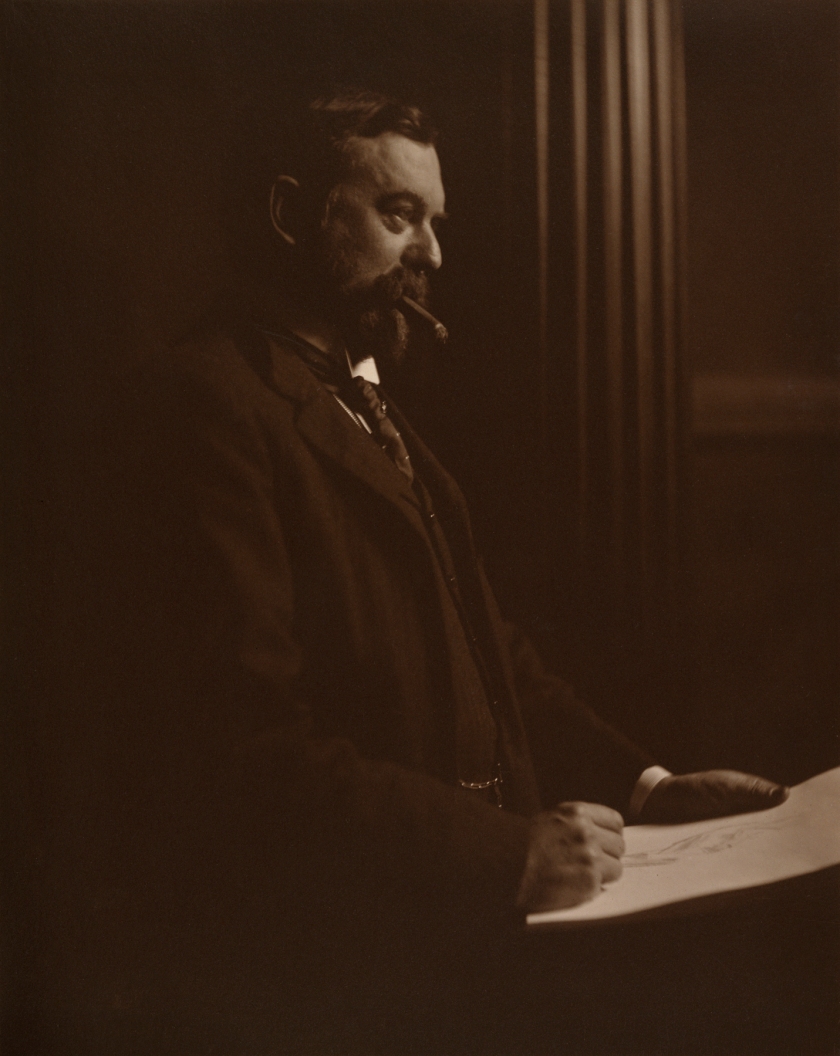

![Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864-1946) '[Self-Portrait]' Negative 1907; print 1930](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/stieglitz-self-portrait-1907.jpg?w=840)

![Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890 Sarah Choate Sears (American, 1858 - 1935) '[Julia Ward Howe]' about 1890](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/sears-julia-ward-howe.jpg?w=807&h=1024)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) '[Sarah Bernhardt as the Empress Theodora in Sardou's "Theodora"]' Negative 1884; print and mount about 1889](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar-sarah-bernhardt.jpg?w=840)

![Charles DeForest Fredricks (American, 1823-1894) '[Mlle Pepita]' 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/fredricks-mlle-pepita.jpg?w=840)

![André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889) '[Rosa Bonheur]' 1861-1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/disdecc81ri-rosa-bonheur.jpg?w=840)

![John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900 John Robert Parsons (British, about 1826-1909) '[Portrait of Jane Morris (Mrs. William Morris)]' Negative July 1865; print after 1900](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/parsons-portrait-of-jane-morris.jpg?w=840&h=1007)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=840)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Alexander Dumas [père] (1802-1870) / Alexandre Dumas' 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/nadar_alexander_dumas.jpg?w=840)

![Roger Fenton (English, 1819-1869) '[Still Life with Game and Gun]' about 1859](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/fenton-still-life-with-game-and-gun.jpg?w=840)

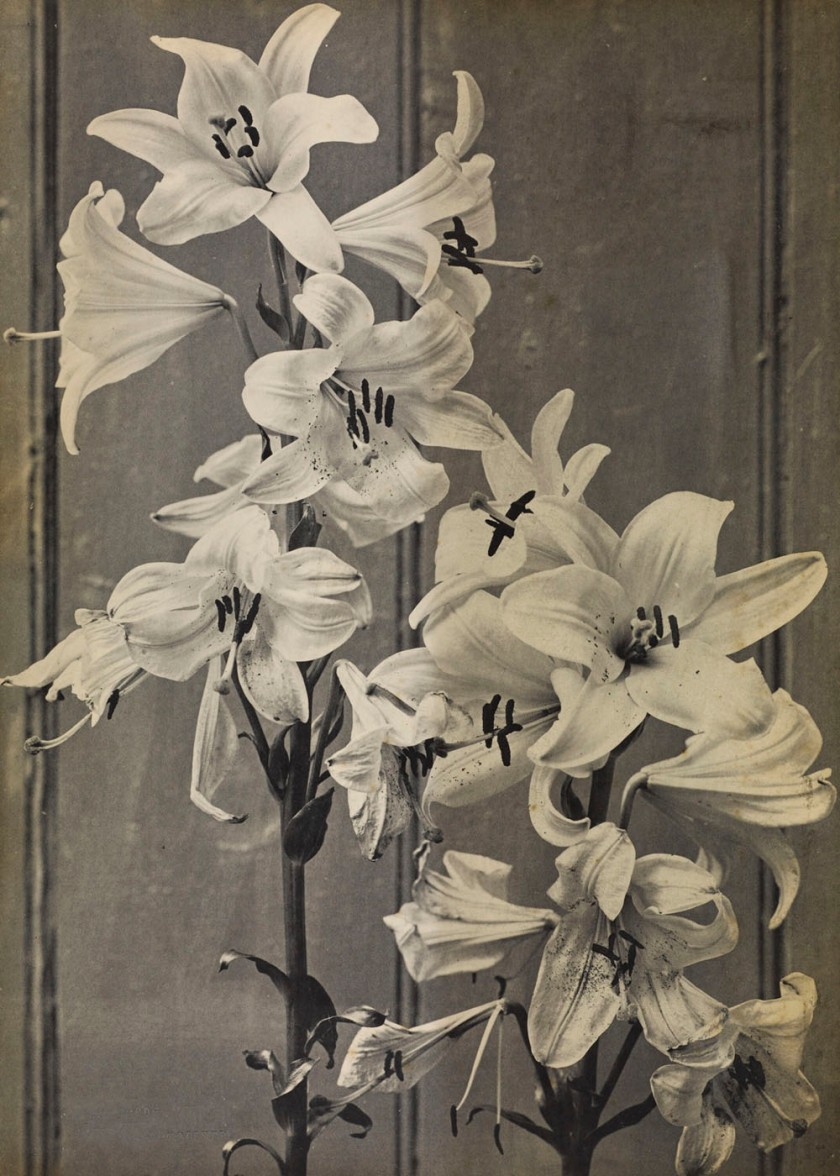

![Charles Aubry (French, 1811-1877) '[An Arrangement of Tobacco Leaves and Grass]' about 1864](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/aubry-tobacco.jpg?w=840)

![Louis-Rémy Robert (French, 1811-1882) '[Still Life with Statuette and Vases]' Negative 1855; print 1870s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/robert-still-life-with-statuette-and-vases.jpg?w=840)

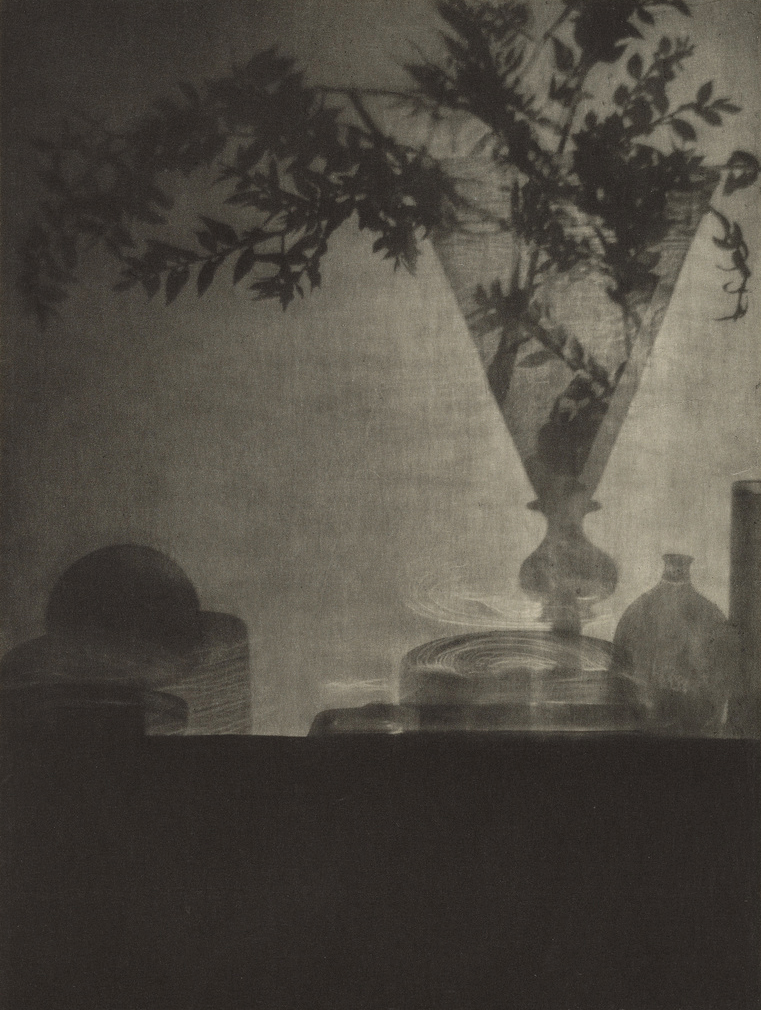

![Heinrich Kühn (Austrian born Germany, 1866-1944) '[Tea Still-life, Version III]' 1907](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/heinrich-kucc88hn-tea-sea-life.jpg?w=840)

![Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976) '[Black Bottle]' negative about 1919; print 1923-1939](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/strand-black-bottle.jpg?w=840)

![André Kertész (American, born Hungary, 1894-1985) '[Bowl with Sugar Cubes]' 1928](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/kertesz-sugar.jpg?w=840)

You must be logged in to post a comment.