Exhibition dates: 3rd December 2019 – 13th December 2020

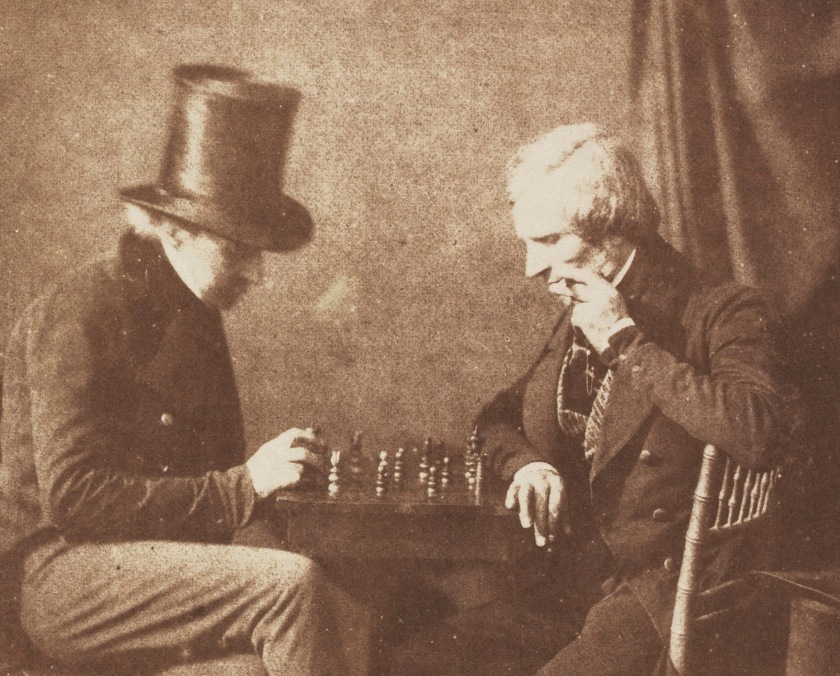

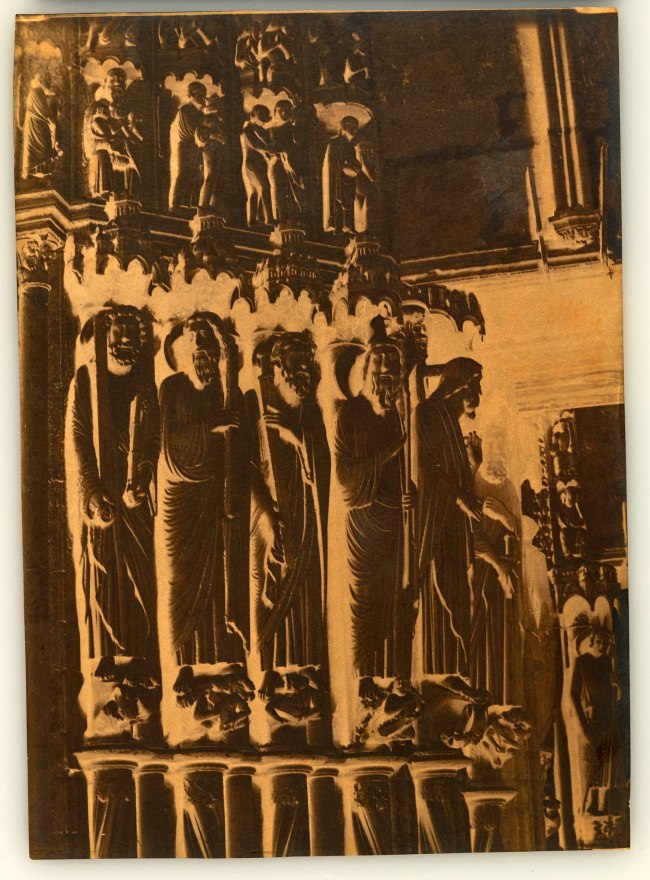

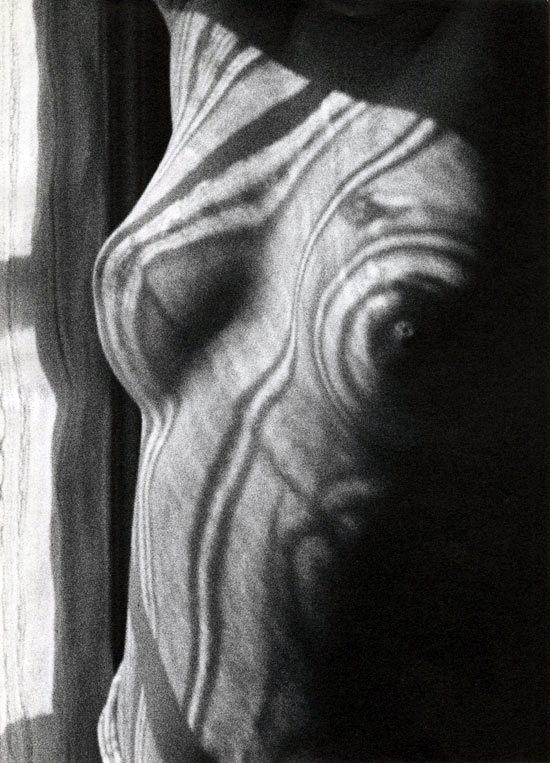

Likely by Antoine-François-Jean Claudet (French, Lyon 1797 – 1867 London)

Possibly by Nicolaas Henneman (Dutch, Heemskerk 1813 – 1898 London)

The Chess Players (detail)

c. 1845

Salted paper print from paper negative

Sheet: 9 5/8 × 7 11/16 in. (24.5 × 19.6cm)

Image: 7 13/16 × 5 13/16 in. (19.8 × 14.7cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

An excellent selection of photographs in this posting. I particularly like the gender-bending, shape-shifting, age-distorting 1850s-60s Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits by an unknown artist. I’ve never seen anything like it before, especially from such an early date. Someone obviously took a lot of care, had a great sense of humour and definitely had a great deal of fun making the album.

Other fascinating details include the waiting horses and carriages in Fox Talbot’s View of the Boulevards of Paris (1843); the mannequin perched above the awning of the photographic studio in Dowe’s Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois (1860s); and the chthonic underworld erupting from the tilting ground in Carleton E. Watkins’ California Oak, Santa Clara Valley (c. 1863).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

When The Met first opened its doors in 1870, photography was still relatively new. Yet over the preceding three decades it had already developed into a complex pictorial language of documentation, social and scientific inquiry, self-expression, and artistic endeavour.

These initial years of photography’s history are the focus of this exhibition, which features new and recent gifts to the Museum, many offered in celebration of The Met’s 150th anniversary and presented here for the first time. The works on view, from examples of candid portraiture and picturesque landscape to pioneering travel photography and photojournalism, chart the varied interests and innovations of early practitioners.

The exhibition, which reveals photography as a dynamic medium through which to view the world, is the first of a two-part presentation that plays on the association of “2020” with clarity of vision while at the same time honouring farsighted and generous collectors and patrons. The second part will move forward a century, bringing together works from the 1940s through the 1960s.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

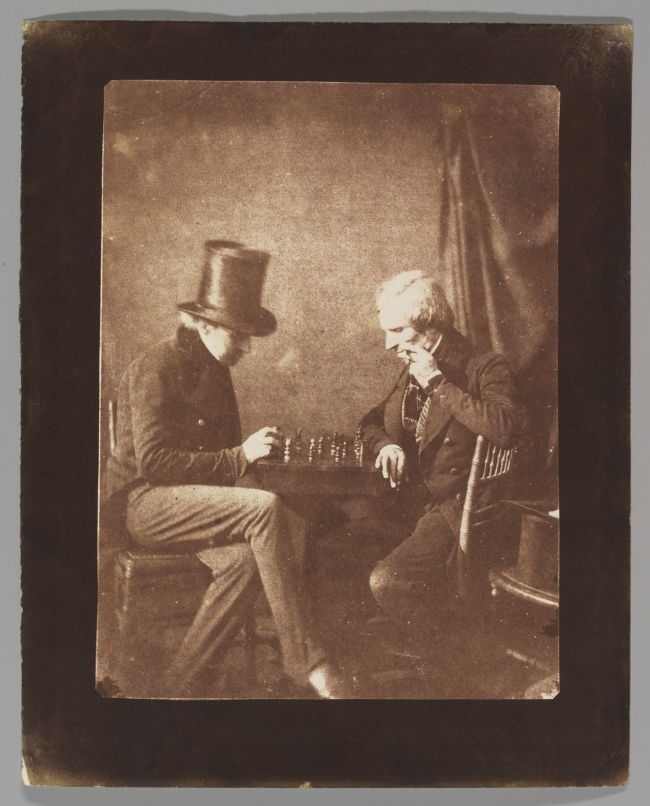

Likely by Antoine-François-Jean Claudet (French, Lyon 1797 – 1867 London)

Possibly by Nicolaas Henneman (Dutch, Heemskerk 1813 – 1898 London)

The Chess Players

c. 1845

Salted paper print from paper negative

Sheet: 9 5/8 × 7 11/16 in. (24.5 × 19.6cm)

Image: 7 13/16 × 5 13/16 in. (19.8 × 14.7cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 – 1898 Guildford)

[Alice Liddell]

June 25, 1870

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Sheet: 6 1/4 × 5 9/16 in. (15.9 × 14.1cm)

Image: 5 7/8 × 4 15/16 in. (15 × 12.6cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

Eighteen-year-old Alice Liddell’s slumped pose, clasped hands, and sullen expression invite interpretation. A favoured model of Lewis Carroll, and the namesake of his novel Alice in Wonderland, Liddell had not seen the writer and photographer for seven years when this picture was made; her mother had abruptly ended all contact in 1863. The young woman poses with apparent unease in this portrait intended to announce her eligibility for marriage. The session closed a long and now controversial history with Carroll, whose portraits of children continue to provoke speculation. In what was to be her last sitting with the photographer, Liddell embodies the passing of childhood innocence that Carroll romanticised through the fictional Alice.

Unknown photographer (American)

[Surveyor]

c. 1854

Daguerreotype

Case: 1.6 × 9.2 × 7.9cm (5/8 × 3 5/8 × 3 1/8 in.)

Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

This portrait of a surveyor from an unknown daguerreotype studio was made during the heyday of the Daguerreian era in the United States, a time that coincided with an increased need for survey data and maps for the construction of railways, bridges, and roads. The unidentified surveyor, seated in a chair, grasps one leg of the tripod supporting his transit, a type of theodolite or surveying instrument that comprised a compass and rotating telescope. The carefully composed scene, in which the angle of the man’s skyward gaze is aligned with the telescope and echoed by one leg of the tripod, conflates its surveyor subject with an astronomer. As a result, the lands of young America are compared to the vast reaches of space, with both territories full of potential discovery.

Unknown photographer (American)

[Surveyor]

c. 1854

Daguerreotype

Case: 1.6 × 9.2 × 7.9cm (5/8 × 3 5/8 × 3 1/8 in.)

Gift of Charles Isaacs and Carol Nigro, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

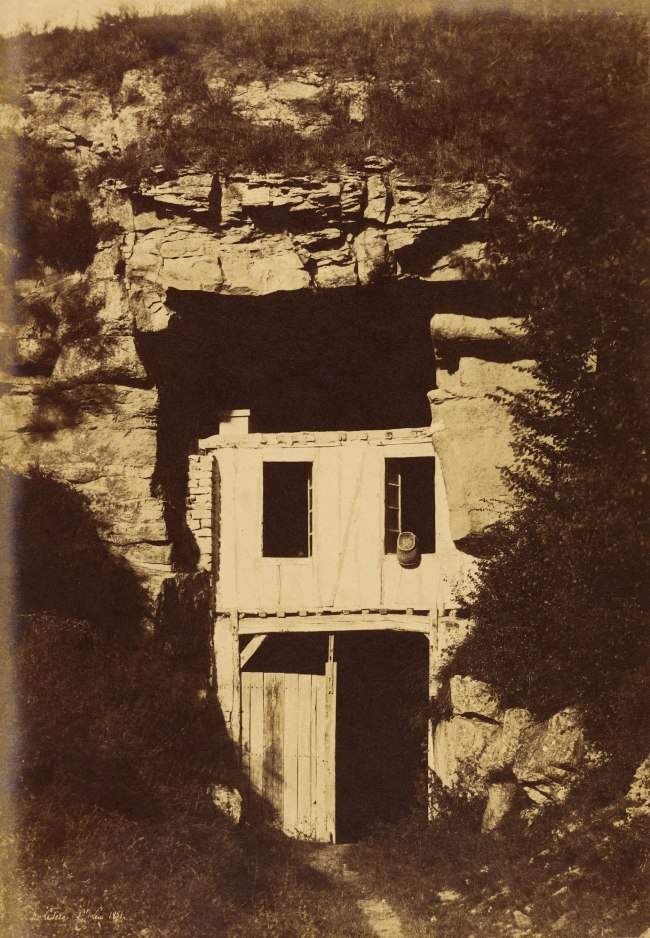

Alphonse Delaunay (French, 1827-1906)

Patio de los Arrayanes, Alhambra, Granada, Spain

1854

Albumen silver print from paper negative

10 in. × 13 5/8 in. (25.4 × 34.6cm)

Gift of W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg, 2017

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

One of the most talented students of famed French photographer Gustave Le Gray, Delaunay was virtually unknown before a group of his photographs appeared at auction in 2007. Subsequent research led to the identification of several bodies of work, including the documentation of contemporary events through instantaneous views captured on glass negatives. Delaunay also was a particular devotee of the calotype (or paper negative) process, with which he created his best pictures – including this view of the Alhambra. Among a group of pictures he made between 1851 and 1854 in Spain and Algeria, this view of the Patio de los Arrayanes reveals the extent to which Delaunay was able to manipulate the peculiarities of the paper negative. He revels in the graininess of the image, purposefully not masking out the sky before printing the negative, so that the marble tower appears somehow carved out of the very atmosphere that surrounds it. In contrast, the reflecting pool remains almost impossibly limpid, its dark surface offering a cool counterpart to the harsh Spanish sky.

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Classical Head]

probably 1839

Salted paper print

6 1/2 × 5 7/8 in. (16.5 × 15cm)

Purchase, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

This luminous head seems to materialise before our very eyes, as if we are observing the moment in which the latent photographic image becomes visible. Nineteenth-century eyewitnesses to Hippolyte Bayard’s earliest photographs (direct positives on paper) described a similarly enchanting effect, in which hazy outlines coalesced with light and tone to form charmingly faithful, if indistinct, images. These works, which Bayard referred to as essais (tests or trials), often included statues and busts, which he frequently arranged in elaborate tableaux. In this case, he photographed the lone subject (an idealised classical head) from the front and side, as if it were a scientific specimen. The singular object emerges as a relic from photography’s origins and now distant past.

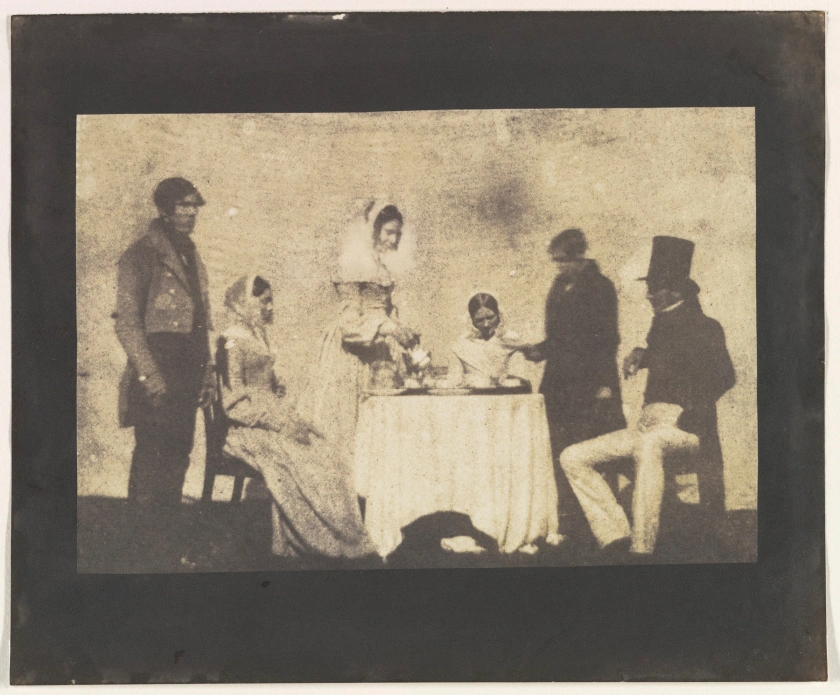

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, Dorset 1800 – 1877 Lacock)

Group Taking Tea at Lacock Abbey

August 17, 1843

Salted paper print from paper negative

Mount: 9 15/16 in. × 13 in. (25.3 × 33cm)

Sheet: 7 3/8 × 8 15/16 in. (18.7 × 22.7cm)

Image: 5 in. × 7 1/2 in. (12.7 × 19cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

Although Talbot’s groundbreaking calotype (paper negative) process allowed for more instantaneous image making, works such as this one nevertheless reflect the technical limitations of early photography. Here, he adapts painterly conventions to the new medium, staging a genre scene on his family estate. The stilted arrangement of figures – rigidly posed to produce a clear image – belies Talbot’s attempt to show action in progress. To achieve sufficient light exposure, he photographed the domestic tableau outdoors, arranging his subjects before a blank backdrop to create the illusion of interior space.

Unknown artist (American or Canadian)

[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]

1850s-1860s

Albumen silver prints

5 15/16 × 5 1/8 × 2 1/16 in. (15.1 × 13 × 5.3cm)

Bequest of Herbert Mitchell, 2008

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

Beginning in the late 1850s, cartes de visite, or small photographic portrait cards, were produced on a scale that put photography in the hands of the masses. This unusual collection of collages is ahead of its time in spoofing the rigidity of the format. The images play with scale and gender by juxtaposing cutout heads and mismatched sitters, thereby highlighting the difference between social identity – which was communicated in part through the exchange of calling cards – and individuality.

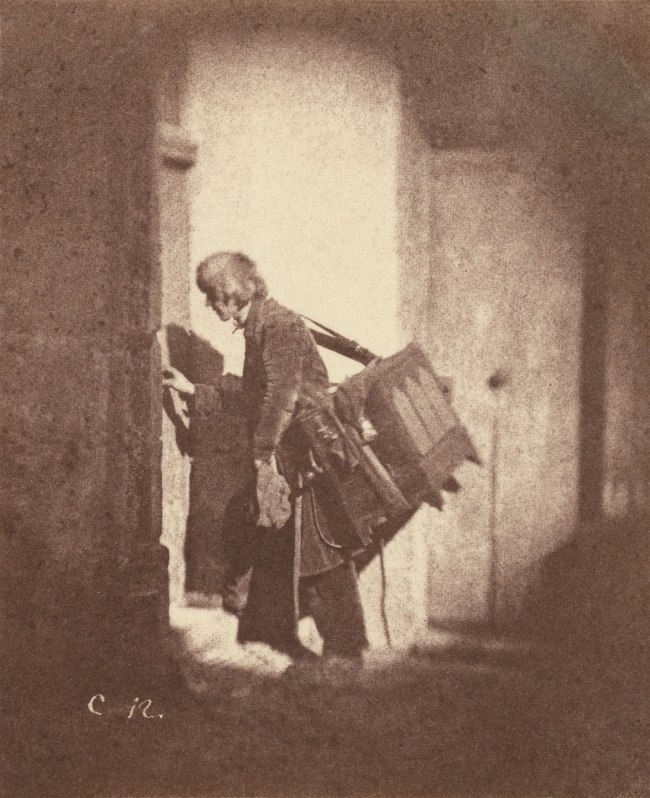

Unknown artist (American)

[Studio Photographer at Work]

c. 1855

Salted paper print

Image: 5 1/8 × 3 13/16 in. (13 × 9.7cm)

Sheet: 9 1/2 × 5 5/8 in. (24.1 × 14.3cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In this evocative image, picture making takes centre stage. Underneath a canopy of dark cloth, the photographer poses as if to adjust the bellows of a large format camera. The view reflected on its ground glass would appear reversed and upside down. Viewers’ expectations are similarly overturned, because the photographer’s subject remains unseen.

Unknown artist (American)

[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]

1850s

Daguerreotype with applied colour

Image: 3 1/4 × 2 3/4 in. (8.3 × 7cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The boy in this picture clutches a cased image to his chest, as if to illustrate his affection for the subject depicted within. Daguerreotypes were a novel form of handheld picture, portable enough to slip into a pocket or palm. Portraits exchanged between friends and family could be kept close – a practice often mimed by sitters, who would pose for one daguerreotype while holding another.

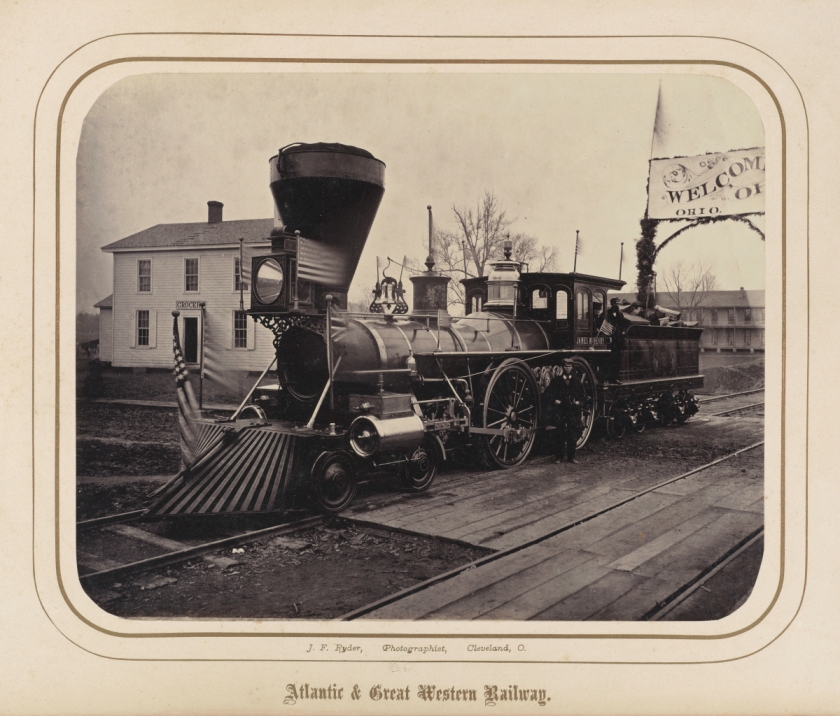

James Fitzallen Ryder (American, 1826-1904)

Locomotive James McHenry (58), Atlantic and Great Western Railway

1862

Albumen silver print

Image: 7 3/8 × 9 1/4 in. (18.7 × 23.5cm)

Mount: 10 × 13 in. (25.4 × 33cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In spring 1862, the chief engineer in charge of building the Atlantic and Great Western Railway – which ran from Salamanca, New York, to Akron, Ohio, and from Meadville to Oil City, Pennsylvania – engaged James Ryder to make photographs that would convince shareholders of the worthiness of the project. Ryder’s assignment was “to photograph all the important points of the work, such as excavations, cuts, bridges, trestles, stations, buildings and general character of the country through which the road ran, the rugged and the picturesque.” In a converted railroad car kitted out with a darkroom, water tank, and developing sink, he processed photographs that make up one of the earliest rail surveys.

Attributed to Josiah Johnson Hawes (American, Wayland, Massachusetts 1808 – 1901 Crawford Notch, New Hampshire)

Winter on the Common, Boston

1850s

Salted paper print

Window: 6 15/16 × 8 15/16 in. (17.6 × 22.7cm)

Mat: 16 × 20 in. (40.6 × 50.8cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Having originally set his sights on a career as a painter, Josiah Hawes gave up his brushes for a camera upon first seeing a daguerreotype in 1841. Two years later, he joined Albert Sands Southworth in Boston to form the celebrated photographic studio Southworth & Hawes. Turning to paper-based photography in the early 1850s, Hawes frequently depicted local scenery. This surprising picture, which presents Boston Common through a veil of snow-laden branches, shows that Hawes brought his creative ambitions to the nascent art of photography.

Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916)

[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]

c. 1863

Albumen silver print

Image: 12 in. × 9 5/8 in. (30.5 × 24.5cm)

Mount: 21 1/4 in. × 17 5/8 in. (54 × 44.8cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

For viewers today, the crown of this majestic oak tree, with its complex network of branches, might evoke the allover paintings of Abstract Expressionism with their layers of dripped paint. As photographed by Carleton Watkins, the dark, flattened silhouette of the tree feathers out across the camera’s field of view. The sloped horizon line, uncommon in Watkins’s output, both echoes the ridge in the distance and grounds the energy of the tree canopy, ably demonstrating his masterful command of pictorial composition.

George Wilson Bridges (British, 1788-1864)

Garden of Selvia, Syracuse, Sicily

1846

Salted paper print from paper negative

Image: 6 15/16 × 8 9/16 in. (17.7 × 21.7cm)

Sheet: 7 5/16 × 8 13/16 in. (18.5 × 22.4cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

The monk’s gesture of prayer in this image by George Wilson Bridges is a touchstone of stillness against the impressive landscape and vegetation that rise up behind him. Bridges was an Anglican reverend and friend of William Henry Fox Talbot, the inventor of the calotype (paper negative), who instructed him on the method before it was patented. Bridges was also one of the earliest photographers to embark upon a tour of the Mediterranean region; he wrote to Talbot that he conceived of the excursion both as a technical mission to advance photography and as a pilgrimage to collect imagery of religious sites.

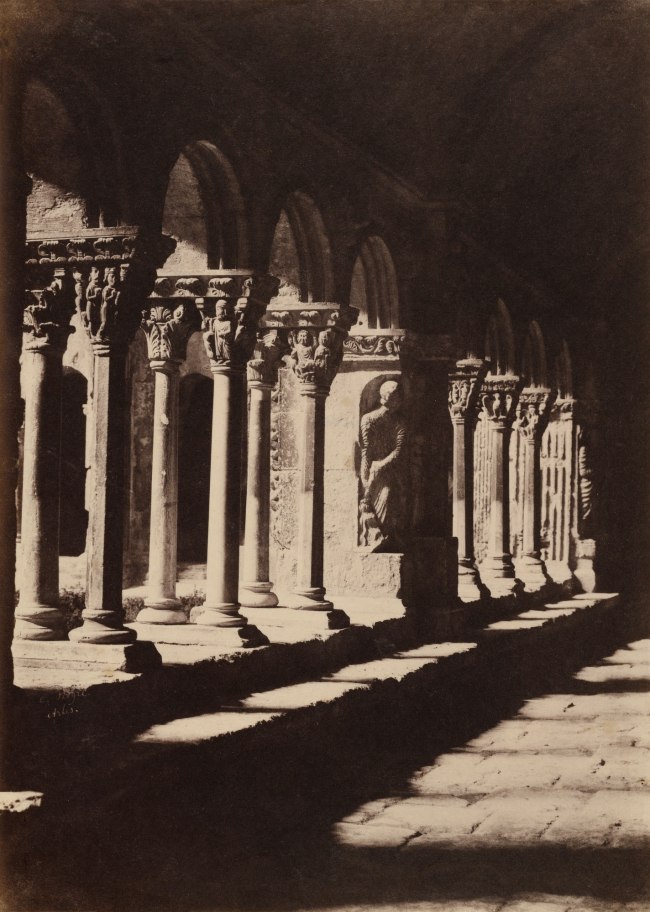

Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885)

[Spanish Steps, Rome]

c. 1855

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Image: 14 11/16 × 11 5/16 in. (37.3 × 28.8cm)

Sheet: 24 7/16 × 18 7/8 in. (62 × 48cm)

Gift of W. Bruce and Delaney H. Lundberg, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

Made in late afternoon light, Pietro Dovizielli’s picture shows a long shadow cast onto Rome’s Piazza di Spagna that almost obscures one of the market stalls flanking the base of the famed Spanish Steps. Rising above the sea of stairs is the church of Trinità dei Monti, its facade neatly bisected by the Sallustiano obelisk. In the piazza, a lone figure – the only visible inhabitant of this eerily empty public square – rests against the railing of the Barcaccia fountain. Keenly composed pictures like this led reviewers of Dovizielli’s photographs to proclaim them “the very paragons of architectural photography.”

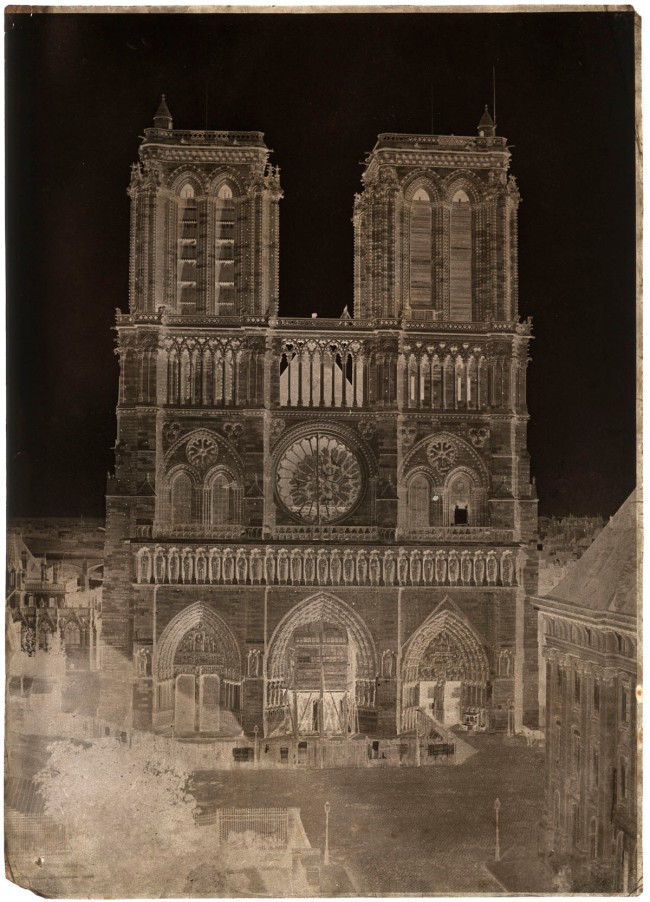

Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889)

[Amphitheater, Nîmes]

c. 1853

Salted paper print from paper negative

Overall: 12 3/8 × 15 3/16 in. (31.5 × 38.5cm)

Gift of Joyce F. Menschel, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Instead of photographing the entire arena in Nîmes, as he had two years earlier, Baldus focusses here on a section of the façade, playing the superimposed arches against the vertical, shadowed pylons in the foreground. The resulting composition manages to isolate and monumentalise the architecture, while creating a rhythmic play of light and dark that energises the picture. The photograph was part of a massive, four-year project, Villes de France photographiées, in which the views from the south of France were said to surpass all of the photographer’s previous work in the region.

William Henry Fox Talbot (British, Dorset 1800 – 1877 Lacock)

View of the Boulevards of Paris

1843

Salted paper print from paper negative

Mount: 9 in. × 10 1/16 in. (22.8 × 25.6cm)

Sheet: 7 3/8 × 10 1/8 in. (18.7 × 25.7cm)

Image: 6 5/16 × 8 1/2 in. (16.1 × 21.6cm)

Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2012

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Public domain

In May 1843 Talbot traveled to Paris to negotiate a licensing agreement for the French rights to his patented calotype process. His invention used a negative-positive system and a paper base – not a copper support as in a daguerreotype. Although his negotiations were not fruitful, Talbot’s views of the elegant new boulevards of the French capital were highly successful.

Filled with the incidental details of urban life, architectural ornamentation, and the play of spring light, this photograph appears as the second plate in Talbot’s groundbreaking publication The Pencil of Nature (1844). The chimney posts on the roofline of the rue de la Paix, the waiting horses and carriages, and the characteristically French shuttered windows evoke as vivid a notion of mid-nineteenth-century Paris now as they must have 170 years ago.

Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s)

[Dowe’s Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]

1860s

Albumen silver print

Image: 5 7/8 × 7 5/8 in. (14.9 × 19.3cm)

Mount: 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Above a bustling thoroughfare in Sycamore, Illinois, boldface lettering advertises the services of photographer Lewis Dowe, a portraitist who also published postcards and stereoviews. Easier to miss in the image is a mannequin perched above the awning to promote the studio. The flurry of activity below Dowe’s storefront and the prime location of the outfit, poised between a tailor and a saloon, speak to the important role of photography in town life.

E. & H. T. Anthony (American)

[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]

1863

Albumen silver prints

Mount: 3 1/4 in. × 6 3/4 in. (8.3 × 17.1cm)

Image: 2 15/16 in. × 6 in. (7.5 × 15.3cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Benefit concerts, minstrel shows, lectures, and horse races all clamour for attention in this graphic field of broadsides posted in the Bowery neighbourhood of Manhattan. The stereograph format lends added depth and dimensionality to the layered fragments of text, transporting viewers to a hectic city sidewalk. Published for a national market, the scene indexes a precise moment in the summer of 1863, offering armchair tourists an inadvertent trend report on downtown cultural life.

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

The Diamond and Wasp, Balaklava Harbour

March, 1855

Albumen silver print from glass negative

Image: 8 in. × 10 1/8 in. (20.3 × 25.7cm)

Mount: 19 5/16 × 24 3/4 in. (49 × 62.9cm)

Gift of Thomas Walther Collection, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fenton’s view of the Black Sea port of Balaklava, which the British used as a landing point for their siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War, shows a busy but orderly operation. The British naval ships, HMS Diamond and HMS Wasp, oversaw the management of transports into and out of the harbour, which explains the presence of ships and rowboats, as well as the large stack of crates near the rail track in the foreground. Against claims of “rough-and-tumble” mismanagement of Balaklava in the British press, Fenton (commissioned by a Manchester publisher to record the theatre of war) offers documentation of a well-functioning port.

Roger Fenton (British, 1819-1869)

The Mamelon and Malakoff from front of Mortar Battery

April, 1855

Salted paper print from glass negative

Image: 9 1/8 × 13 1/2 in. (23.1 × 34.3cm)

Sheet: 14 3/4 × 17 13/16 in. (37.5 × 45.3cm)

Gift of Joyce F. Menschel, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary, 2019

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fenton’s extensive documentation of the Crimean War – the first use of photography for that purpose – was a commercial endeavour that did not include pictures of battle, the wounded, or the dead. His unprepossessing view of a vast rocky valley instead discloses, in the distance, a site of crucial strategic importance. Fort Malakoff, the general designation of Russian fortifications on two hills (Mamelon and Malakoff) is just perceptible at the horizon line. Malakoff’s capture by the French in September 1855, five months after Fenton made this photograph, ended the eleven-month siege of Sevastopol and was the final episode of the war.

Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881)

[Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem]

1856-1857

Albumen silver print

Image: 9 in. × 11 1/4 in. (22.9 × 28.6cm)

Mount: 17 5/8 in. × 22 1/2 in. (44.8 × 57.2cm)

Gift of Joyce F. Menschel, 2013

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

This detailed print showing the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem provides a sense of the structure’s natural and architectural surroundings. Felice Beato depicted the religious site from a pilgrim’s point of view – walls and roads are given visual priority and stand between the viewer and the shrine. Holy sites such as this were the earliest and most common subjects of travel photography. Beato made multiple journeys to the Mediterranean and North Africa, and he is perhaps best known for photographing East Asia in the 1880s.

R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s)

[Self-Portrait (?)]

1850s

Daguerreotype with applied colour

Image: 3 1/4 × 4 1/4 in. (8.3 × 10.8cm)

William L. Schaeffer Collection, Promised Gift of Jennifer and Philip Maritz, in celebration of the Museum’s 150th Anniversary

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The insouciant subject here may be the daguerreotypist himself, posing in bed for a promotional picture or a private joke. His rumpled suit and haphazard hairstyle affect intimacy, perhaps in an effort to showcase an informal portrait style. Because they required long exposure times, daguerreotypes often captured sitters at their most stilted. With this surprising picture, the maker might have hoped to attract clients who were in search of a more novel or natural likeness.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

1000 Fifth Avenue at 82nd Street

New York, New York 10028-0198

Phone: 212-535-7710

Opening hours:

Thursday – Tuesday 10am – 5pm

Closed Wednesday

![Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/lewis-carroll-alice-liddell.jpg?w=650&h=741)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-surveyor-a.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-surveyor-b.jpg?w=650&h=758)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/bayard-classical-head.jpg?w=650&h=715)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-a.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-b.jpg?w=650&h=760)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-c.jpg?w=650&h=798)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-d.jpg?w=650&h=844)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-e.jpg?w=650&h=800)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-f.jpg?w=650&h=771)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-g.jpg?w=650&h=830)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-h.jpg?w=650&h=761)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855 Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/unknown-artist-american-studio-photographer-at-work-c-1855.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/unknown-american-active-1850s-boy-holding-a-daguerreotype-1850s.jpg?w=650&h=759)

![Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863 Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/watkins-california-oak-santa-clara-valley.jpg?w=650&h=805)

![Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855 Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/dovizielli-spanish-steps.jpg?w=650&h=846)

![Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853 Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/baldus-amphitheater.jpg?w=840)

![Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/lewis-dowe-dowes-photograph-rooms-sycamore-illinois-1860s.jpg?w=840)

![E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863 E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/e-h-t-anthony-specimens-of-new-york-bill-posting-1863.jpg?w=840)

![Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857 Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/beato-dome.jpg?w=840)

![R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/r.c.-montgomery-self-portrait-1850s.jpg?w=650&h=1068)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Self-Portrait' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal12-web.jpg?w=650&h=800)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'Jean-François Philibert Berthelier, Actor' 1856-1859](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal21-web.jpg?w=650&h=821)

![Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865 Nadar [Gaspard Félix Tournachon] (French, 1820-1910) 'George Sand (Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin), Writer' c. 1865](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/realideal5-web.jpg?w=650&h=854)

You must be logged in to post a comment.