Exhibition dates: 11th September 2019 – 2nd February 2020

Visited October 2019 posted February 2020

Curators: Martin Myrone, Senior Curator, pre-1800 British Art, and Amy Concannon, Curator, British Art 1790-1850

Room 3 continued…

Patronage and independence

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing twelve large colour prints

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Visions of divine damnation

I believe. I am a believer… a person who believes in the truth and/or existence of something, that ineffable something, that is the magic of the art of William Blake.

I believe that it would take a lifetime of scholarship to begin to fully understand the mythology, symbolism, and poetry of this man. I do not possess that knowledge. What I do posses is the ability to look at these images, process their form, colour, movement and, possibly, feel their spirit.

From academic beginnings Blake develops a unique artistic language. The rebellious, radical symbolism of his books, humanist veins, tap into the un/bound scrimmage of pleasure and pain, f(l)ights of good and evil told through visual poems, paeans to the diabolical munificence of the cosmos.

When I look at Blake I am swept along in the sensuous, writhing curves of the body. I feel their lyrical movement, whether they are partner to themes of childhood and morality, or suffering and social injustice for example. I feel that they touch my soul, deeply. Suffused with melancholy, damnation, joy, redemption and forgiveness his forms raise me up from the everyday. They challenge me to understand… to understand the work, myself and the world in which I live. They have as much relevance today as they ever did. They are revelatory.

The startling a/symmetry and interweaving of forms that characterises so much of his work is particularly affective. The symmetry of the hands in Small Book of Designs: Plate 11, Gowned Male Seen from behind (1794) with the diagonal sweep of the leg; the interwoven leg and arms of The Great Red Dragon and the Beast from the Sea (c. 1805); and the glorious design for The Angel Rolling away the Stone (c. 1805) with its suffused colour scheme and ethereal light are three examples in this rich tapestry of creation. His work seems to float as if a breathless cloud, suffused with sex and spiritual ecstasy, imbibing of the realm of the sublime and the imagination.

In this second part of the posting, most impressive were the twelve large colour prints (below), a series of 12 large ‘frescos’ as Blake called them. To stand in a gallery and be surrounded by such powerful images was incredible. One after the other took your breath away through their musical form and colour. The binary opposites of The Good and Evil Angels (1795 – c. 1805), the Active Evil angel – “strong, muscular, agile; but dirty, indolent and trifling” – with his sightless eyes transfixing you. The hybrid of man and beast that is Nebuchadnezzar (1795 – c. 1805), “crawling the Earth on his hands and knees, skin like hide, toes turning into griffin’s talons.” Or the question mark of the form that is Newton (1795 – c. 1805), which shows “the mathematician and physicist completely absorbed in a geometrical problem, oblivious to the wondrous rock on which he sits.” Blind to the wonders of the world, here scientific rationalism is seen to be inadequate without the imagination and the creativity of the artist. Just a small detail, but the colouration of the rocks behind Newton will long live in my memory for its delicacy and radiance – a colour print enhanced with additional watercolour on paper, almost sponged on, like the under/world sponges at the bottom of the sea.

Other highlights in the second half of the exhibition was a recreation of Blake’s 1809 solo exhibition at his home at 28 Broad Street, London. Even though the paintings have darkened significantly over the years, the installation gave you an idea of how the paintings, highlighted with gold leaf, would have looked through the filtered light of Georgian windows, or would have shimmered under candlelight, as your eyes strained to see the forms of his paradise / lost. Another physiognomic “vision” – “the stuff of delirium and nightmare, [which] taps into the unconscious, internalised sublime” – was the painting The Ghost of a Flea (c. 1819) used to illustrate John Varley’s Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy (1828). In studying the work of Blake for this posting, I found it instructive to look at Blake’s preparatory sketches for his works which can be found online. They give you a good idea of the spontaneity of the drawing and the ideas that arise, transformed into the finished work. Here in the graphite on paper drawing of The Ghost of a Flea we can see Blake’s initial vision, a more static, pensive figure with serrated wings which morphs into a muscular, blood sucking monster set on a cosmic stage, of life framed by curtains and a shooting star. As the vision appeared to Blake he is said to have cried out: ‘There he comes! his eager tongue whisking out of his mouth, a cup in his hand to hold blood, and covered with a scaly skin of gold and green.’

My favourite works in this exhibition were Blake’s two exquisite large paintings, The Virgin and Child in Egypt (1810) and An Allegory of the Spiritual Condition of Man (? 1811). Bearing in mind that these two paintings would have darkened over time and the colours have changed, I was completely mesmerised by the intimacy of these images. The Mannerist hands and beatific nature of the first, and the Ascension of the figures in the second were completely sublime. His largest surviving canvases are RADIANT, all triangular structure, shimmering paint and Buddhist, Northern European iconography. That’s something that I did notice that hardly anyone talks about – how some of his figures echo the Zen-like quality of Buddhist painting.

His celestial bodies seem to exist in a place outside of this world, but they speak to us today as strongly as ever, of the trials and tribulations of our contemporary world – the struggle for the existence of life, of the animals and creatures of this planet, against the avarice of the rich and powerful, of nations and corporations that rape and pillage. Blake was an artist of the imagination rather than reason, a champion of creativity and feeling. Humanity, nature, creatures and creation are still the stuff of life on earth. Our life on earth.

I was so fully immersed in Blake’s world I did not want to leave. The spirit of this man and his work places him at the pinnacle of artistic creation, up there with Michelangelo and Rembrandt. At the time that Blake was working (and was considered a crackpot and mad), Beethoven was still conducting his own symphonies and dedicating his ‘Eroica’ (heroic) symphony to the tyrant Napoleon in 1804 before, in a fit of rage, scrubbing out Napoleon’s name after he ignominiously named himself Emperor. Both Blake and Beethoven were inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution and the liberty of the common man. Just think about that.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,137

Many thankx to Tate Britain for allowing me to publish the media images in the posting. All other installation photographs as noted © Dr Marcus Bunyan. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“The curators of this colossal survey, the first on such a scale in nearly 20 years, are wise to point out the almost impenetrable complexities of Blake’s thinking from the start. Their aim is to throw the focus on his works as images, as opposed to emblems – tiny, teeming visions of gods, monsters and wild scenarios taking place at the bottom of the ocean or outer space, but above all in the free world of Blake’s imagination. …

And Blake’s art remains irreducibly strange. Familiarity cannot diminish the utter singularity of his home-grown aesthetic: heads floating on columns of transparent Lycra-like material, rippling up towards multicoloured skies or gathering in tumultuous spirals. Saints diving through the firmament, devils flickering like fire, angels back-crawling through transparent seas. Lone bodies are shown in convulsion, drowning, paralysed or hunched tight as padlocks. Unbound, they appear spreadeagled, levitating, or hurtling upwards like the bellowed flames up a chimney.”

Laura Cumming. “William Blake review – a rousing call to arms,” on The Guardian website Sun 15 Sep 2019 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

Twelve large colour prints

Blake made these prints using a form of experimental monotype. This involved painting tacky ink onto a board and transferring it through pressure onto paper. He enhanced the basic printed image with ink and watercolour. The end result is very painterly, but with textures impossible to achieve by hand. Blake referred to these works as ‘frescos’. This reflects his wish to imitate the grand wall paintings of the ancient world and medieval times.

Thomas Butts purchased eight of these prints from Blake in 1805, and probably owned a full set. The subject matter comes from the Bible, Shakespeare and Milton, as well as Blake’s imagination. There is no definitive sequence. Scholars have connected the prints in many different, inventive ways.

Wall text

A collection of twelve large prints by William Blake have been brought together at Tate Britain. Over 200 years old, these fragile works are normally only shown in small groups for short periods of time, making this an unmissable opportunity to see the remarkable full series together. The striking prints were sold by Blake as a group in 1805 and included one of his most iconic images, Newton 1795 – c. 1805. Produced using an experimental form of monotype printing that was enhanced with ink and watercolour, they appear painterly but with some extraordinary textures which would be impossible to achieve by hand. The collection draws inspiration from the world of science, the Bible, Shakespeare and Milton, as well as Blake’s own mind. Scholars have connected the prints in many different, inventive ways, but each image remains open to the viewers’ imagination.

Text from Tate Britain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Good and Evil Angels (installation views)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Good and Evil Angels

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

445 × 594 mm

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

In his annotations to a text by Lavater, Blake claimed that ‘Active Evil is better than Passive Good’, rendering the figures in this picture somewhat ambiguous. Perhaps the chain attached to the ‘evil’ angel’s ankle suggests the curtailing of energy by misguided rational thought?

In constructing his figures, Blake evokes conventional eighteenth century stereotypes. The heavy build and darker skin of the ‘evil’ angel suggest a non-European character, described by Lavater as ‘strong, muscular, agile; but dirty, indolent and trifling’, while the fair hair and light skin of the ‘good’ angel are consonant with ideas of physical – and intellectual – perfection.

Gallery label, March 2011

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Good and Evil Angels (installation views details)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing at left, Christ Appearing to the Apostles after the Resurrection (c. 1795) and at right, Nebuchadnezzar (1795 – c. 1805)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Nebuchadnezzar (installation views)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Nebuchadnezzar

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

54.3 x 72.5cm

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Gift of Mrs. Robert Homans

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Nebuchadnezzar (installation view details)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

The king of Babylon is a terrible warning to us all: “those that walk in pride, the Lord can abase”. Blake’s Nebuchadnezzar has been so abased it is by now a hybrid of man and beast, crawling the Earth on his hands and knees, skin like hide, toes turning into griffin’s talons.

Laura Cumming. “William Blake review – a rousing call to arms,” on The Guardian website Sun 15 Sep 2019 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Newton (installation views)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Newton (1795 – c. 1805), the first impression, is another of Blake’s most famous images. It shows the brilliant mathematician and physicist completely absorbed in a geometrical problem, oblivious to the wondrous rock on which he sits. Its standard interpretation is that Newton’s scientific rationalism was inadequate without imagination and the creativity of the artist – a negative view of the man who is still considered a towering genius.

Hoakley. “Tyger’s eye: the paintings of William Blake, 5 – The large prints, 1795,” on The Electric Light Company website November 26, 2016 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Newton

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

460 x 600 mm

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

In this work Blake portrays a young and muscular Isaac Newton, rather than the older figure of popular imagination. He is crouched naked on a rock covered with algae, apparently at the bottom of the sea. His attention is focused on a diagram which he draws with a compass. Blake was critical of Newton’s reductive, scientific approach and so shows him merely following the rules of his compass, blind to the colourful rocks behind him.

Gallery label, October 2018

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Newton (installation view detail)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Tate Britain has reimagined Blake’s paintings on the grand scale he envisioned, alongside recreating the humble reality of the only exhibition he staged in his lifetime. For the first time, The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan c. 1805-1809 and The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth c. 1805 have been digitally enlarged to be projected onto the gallery wall. The original paintings are shown nearby in a reconstruction of Blake’s ill-fated exhibition of 1809.

William Blake had grand ambitions as a visual artist and proposed vast frescos that were never realised. The artist suggested that Nelson and Pitt be executed 100-feet-high, following in the tradition of Renaissance masters such as Michelangelo and Raphael. Blake was confident he would ‘receive a national commission to execute these two pictures on a scale that was suitable to the grandeur of the nation’. However, the subjects he chose were ambiguous. Although depicting great British heroes of the time, each figure is shown commanding a vicious biblical beast, hinting at Blake’s own liberal and anti-war politics.

Blake first exhibited these images in 1809 above his family’s hosiery business in Soho. The architectural details of this small domestic space have been recreated at Tate Britain, allowing visitors to see the original works in context. The 1809 exhibition was a critical and commercial disaster and Blake consequently withdrew from public life. Attracting few visitors, the only review described ‘a few wretched pictures … a farrago of nonsense, unintelligibleness, and egregious vanity, the wild effusions of a distempered brain’.

Martin Myrone, Senior Curator, pre-1800 British Art, Tate said: “We are thrilled to celebrate Blake as a true visionary and to finally realise the full scale of his ambitions as a visual artist. It’s also important to set him in context, considering the reception of his work and how it was experienced by his contemporaries. Through the re-staging of the 1809 exhibition, as well as through the rare display of his illuminated books in their original bindings, visitors will be able to encounter Blake’s works as they were first seen over 200 years ago.”

Text from Tate Britain

Short Biography

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. What he called his prophetic works were said by 20th-century critic Northrop Frye to form “what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language”. His visual artistry led 21st-century critic Jonathan Jones to proclaim him “far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced”. In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC’s poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. While he lived in London his entire life, except for three years spent in Felpham, he produced a diverse and symbolically rich œuvre, which embraced the imagination as “the body of God” or “human existence itself”.

Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and as “Pre-Romantic”. A committed Christian who was hostile to the Church of England (indeed, to almost all forms of organised religion), Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American Revolutions. Though later he rejected many of these political beliefs, he maintained an amiable relationship with the political activist Thomas Paine; he was also influenced by thinkers such as Emanuel Swedenborg. Despite these known influences, the singularity of Blake’s work makes him difficult to classify. The 19th-century scholar William Michael Rossetti characterised him as a “glorious luminary”, and “a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors”.

Text from the Wikipedia website

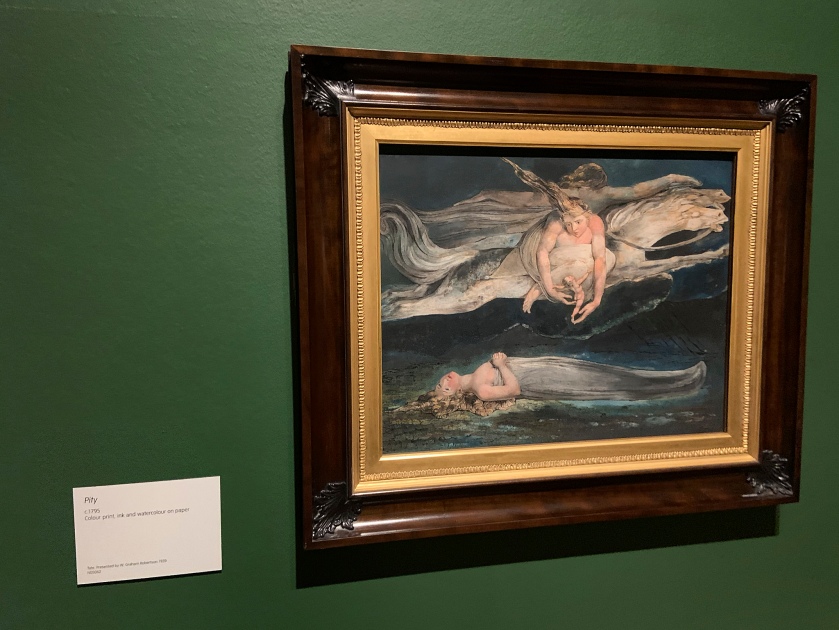

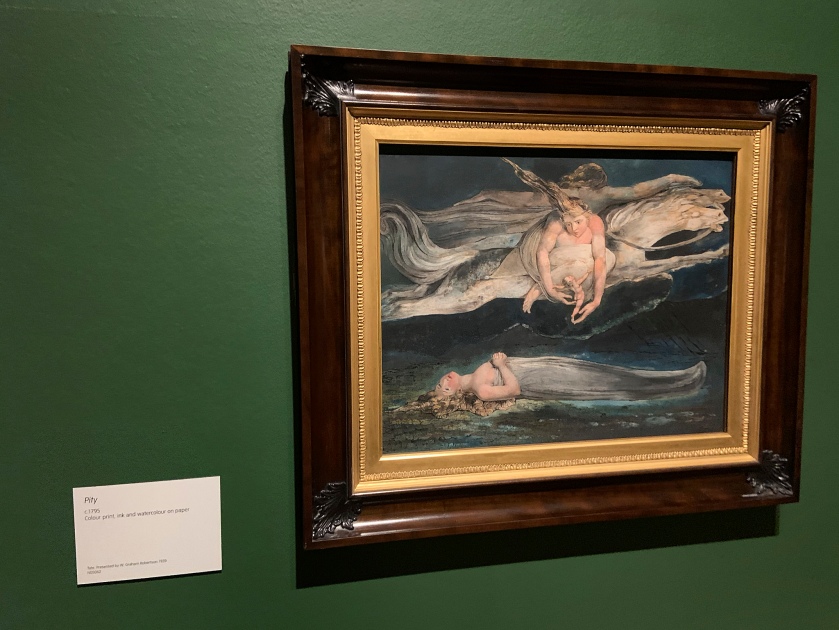

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Pity (installation views)

c. 1795

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

425 x 539 mm

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This image is taken from Macbeth: ‘pity, like a naked newborn babe / Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim horsed / Upon the sightless couriers of the air’. Blake draws on popularly-held associations between a fair complexion and moral purity. These connections are also made by Lavater, who writes that ‘the grey is the tenderest of horses, and, we may here add, that people with light hair, if not effeminate, are yet, it is well known, of tender formation and constitution’. Blake’s interest in the characters of different horses can also be seen in his Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims.

Gallery label, March 2011

And pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, horsed

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind. …

Act 1 Scene 7 of Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Pity

c. 1795

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

425 x 539 mm

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing at left, Satan Exulting over Eve (c. 1795) and at right, Lamech and his Two Wives (1795)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing at left, Lamech and his Two Wives (1795) and at right, Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab (c. 1795)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab (installation views)

c. 1795

Colour print finished in pen and ink, shell gold and Chinese white on paper

42.5 x 60cm

Victoria and Albert Museum. Given by J. E. Taylor, Esq, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab (c. 1795) is another first impression, showing a slightly more familiar Biblical narrative from the book of Ruth, chapter 1, verses 11-17. Naomi, seen at the left in a black robe, and her two daughters-in-law have become widowed. She decides to leave the land of Moab to return to her kin in Judah. Ruth, who is embracing her, remains devoted to Naomi, and returns with her, but Orpah, walking off to the right, decides to stay. Interestingly, because of her place in the lineage of David and so that of Jesus, Blake gives Naomi a halo, but not Ruth.

Hoakley. “Tyger’s eye: the paintings of William Blake, 5 – The large prints, 1795,” on The Electric Light Company website November 26, 2016 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Naomi Entreating Ruth and Orpah to Return to the Land of Moab

c. 1795

Colour print finished in pen and ink, shell gold and Chinese white on paper

42.5 x 60cm

Victoria and Albert Museum. Given by J. E. Taylor, Esq, London

Image courtesy of and © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The House of Death (installation views)

1795 – c.1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Blake produced a number of designs relating to plague, war, fire and disaster … This design has been linked to the poet John Milton’s vision of a ‘Lazar House’ – a hospital for infectious diseases – from Paradise Lost (1664).

The English poet John Milton, who died in 1674, was viewed by Blake as England’s greatest poet, worthy of emulation but by no means above criticism. It was inevitable that in the large colour prints, his most important printing project, Blake would include Miltonic subjects.This print illustrates lines from Book XI of Milton’s poem Paradise Lost. The Archangel Michael shows Adam the misery that will be inflicted on Man now he has eaten the Forbidden Fruit. In a vision of ‘Death’s ‘grim Cave” Adam sees a ‘monstrous crew’ of men afflicted by ‘Diseases dire’.

Gallery label, August 2004

The House of Death (1795 – c. 1805), sometimes known as The Lazar House (a lazar is someone afflicted with a disease), is the first impression. It is a rather grim image taken from Milton’s Paradise Lost book 11, lines 477-493. There, the Archangel Michael shows Adam the afflictions that man will suffer in the form of disease, now that he has eaten the Forbidden Fruit. So rather than the bodies being dead, they are in the throes of suffering the diseases which have been unleashed following the Fall.

The similarity of the figure, who should (by Milton) be the Archangel Michael, to Blake’s images of Urizen, is clear, and may refer back to his illuminated books, and to the French Revolution.

Hoakley. “Tyger’s eye: the paintings of William Blake, 5 – The large prints, 1795,” on The Electric Light Company website November 26, 2016 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The House of Death

1795 – c.1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Elohim Creating Adam (installation views)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Elohim is a Hebrew name for God. This picture illustrates the Book of Genesis: ‘And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground’. Adam is shown growing out of the earth, a piece of which Elohim holds in his left hand.

For Blake the God of the Old Testament was a false god. He believed the Fall of Man took place not in the Garden of Eden, but at the time of creation shown here, when man was dragged from the spiritual realm and made material.

Gallery label, May 2003

Elohim Creating Adam (1795, c 1805) is the only surviving impression of this work, which appears to have been listed by Blake as God Creating Adam. It is based on the book of Genesis chapter 2 verse 7:

And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.

Blake shows this fairly literally, with Adam’s body still being formed out of the earth, and a large worm (not a serpent) is coiled around his left leg. The worm is also a symbol of mortality.

Blake’s mythology for Elohim, the Hebrew word for God and judge, is different from the ‘standard’ Christian concept of God, and distinct from Urizen too. I am not convinced that Blake intended to show his Elohim or Urizen here, and therefore the work may better be titled simply as God Creating Adam.

Hoakley. “Tyger’s eye: the paintings of William Blake, 5 – The large prints, 1795,” on The Electric Light Company website November 26, 2016 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Elohim Creating Adam (installation views)

1795 – c. 1805

Colour print, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing The Horse c. 1805

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Quote above The Horse

“For when Los joind with me he took me in his firy whirlwind My Vegetated portion was hurried from Lambeths shades He set me down in Felphams Vale & prepard a beautiful Cottage for me that in three years I might write all these Visions To display Natures cruel holiness: the deceits of Natural Religion Walking in my Cottage Garden, sudden I beheld The Virgin Ololon & address’d her as a Daughter of Beulah.”

William Blake, from ‘Milton a Poem’, c. 1804-1811

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Horse (installation view)

c. 1805

Tempera and ink on copper engraving plate

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Room 4

Independence and despair

The Enquiry in England is not whether a Man has Talents. & Genius – But whether he is Passive & Polite & a Virtuous Ass

This gallery traces a particularly tumultuous period in Blake’s life, from 1805 to 1812. In 1805 he secured work illustrating Robert Blair’s poem The Grave. Published in 1808, his designs were a critical success, praised by many leading artists and patrons. But Blake was disappointed that he did not get the work of engraving the illustrations as well as designing them. He also suspected the publisher, Robert Cromek, of stealing his idea to do an engraving of the pilgrims from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

In 1809 Blake organised a retrospective exhibition of his work. This was held in Broad Street, Soho, in the family home where his brother was now running the hosiery business. The exhibition catalogue set out his highly personal ideas about art and his ambitions as a painter of large-scale frescos. This room includes a recreation of the 1809 exhibition where you can experience Blake’s work as it would have been seen in Broad Street. There is also a projection showing his paintings at the gigantic scale he hoped to realise them.

The exhibition of 1809 was, however, a critical and commercial disaster. Blake was bitterly disappointed and felt betrayed by his friends in the art world. Having made big claims about restoring ‘the grand style of Art’, he exhibited for the last time in 1812. He then withdrew from the public gaze for several years.

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Death of the Good Old Man (installation views)

1805

Pen and ink and watercolour over traces of graphite on paper

Collection of Robert N. Essick

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Death of the Strong Wicked Man (installation views)

1805

Ink, watercolour and graphite on paper Paris, Musée du Louvre, Départment of Arts graphiques

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Death of the Strong Wicked Man

1805

Ink, watercolour and graphite on paper Paris, Musée du Louvre, Départment of Arts graphiques

© Photo RMN – Gerard Blot

The Grave

The materials gathered here relate to Blake’s work for an edition of Robert Blair’s poem, The Grave, published in 1808. Blake scholars have not given these images as much attention as illustrations of his original writings. But he took this project seriously, and it secured him a degree of acclaim at a difficult time in his career.

The illustrations were commissioned by Robert Cromek in 1805. This was the first publishing venture of Cromek, an engraver. Blake quickly produced the 20 drawings. He may have been invigorated by the themes of Blair’s poem, a reflection on death and the afterlife.

Cromek promoted The Grave tirelessly, taking Blake’s work to new places and new publics. As well as displaying them at his London house, Cromek toured Blake’s designs to Birmingham and Manchester. The illustrations were generally well received, but Blake came to feel betrayed by Cromek, who employed the fashionable engraver Luigi Schiavonetti to produce the prints.

Wall text from the exhibition William Blake

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

A Title Page for The Grave (installation views)

1806

Ink and blue watercolour on paper

238 × 200 mm

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

The 1809 Exhibition

The space opposite evokes the upstairs rooms at 28 Broad Street, Soho, where Blake held his one-man exhibition in 1809. This was an ordinary London town-house, built in the 1730s. The Blake family had lived there since the 1750s. We know the proportions of the front room on the first floor from archival records and images. Visitors probably gained access to the exhibition through the hosiery shop downstairs. In 1809 this was being run by Blake’s brother, James. This was a strange setting for an art exhibition.

It was even stranger given the visionary character of Blake’s works and the gigantic ambitions he expressed in the accompanying Descriptive Catalogue. There were only a handful of visitors, and a single published review which dismissed Blake as ‘an unfortunate lunatic’. Every 20 minutes two works in this recreated exhibition will be virtually ‘restored’. They will be illuminated so you can see how they would have looked in 1809. You will also hear Blake’s words about these pictures, expressing his ambition to be a painter of large-scale wall paintings. Blake’s words are spoken by the actor Kevin Eldon.

The projection shows details from two of Blake’s paintings at the scale Blake hoped his work might one day be seen. They depict the ‘spiritual forms’ of the Prime Minster, William Pitt, and the naval hero, Admiral Nelson. In the catalogue of his 1809 exhibition, Blake wrote of his ambition to execute these and other paintings 30 metres high or more, for display in public buildings.

Many artists in Blake’s time aspired to such ambitious paintings, inspired by the high-minded rhetoric of the Royal Academy. But Blake himself observed: ‘The Painters of England are unemployed in Public Works’. There was no state support for artists, and little patronage from the monarchy or Church of England. Artists were instead freelancers, dependent on the market.

Despite his aspirations, Blake must have known that his dreams would never be fulfilled. After the failure of his one-man show in 1809 he became increasingly withdrawn and bitter.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Penance of Jane Shore in St Paul’s Church

c. 1793

Ink, watercolour and gouache on paper

245 × 295 mm

Tate

Presented by the executors of W. Graham Robertson through the Art Fund 1949

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Jane Shore was a mistress of King Edward IV. After his death in 1483 she was accused of being a harlot and condemned to do public penance in St Paul’s Cathedral. The ‘golden glow’ of this watercolour comes from a very thick, now-yellowed glue layer that was almost certainly applied as a varnish by Blake. He varnished his temperas in a similar way. Once it had yellowed someone else added a picture varnish on top. This also went yellow but has since been removed. The subtle colouring of Blake’s painting is suppressed by the glue varnish.

Gallery label, September 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Christ in the Sepulchre, Guarded by Angels

c. 1805

Ink and watercolour on paper

42.0 x 30.2 cm

Lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Ruth the Dutiful Daughter in Law

1803

Wash, graphite, and coloured chalk on paper

Southampton City Art Gallery

Blake’s one-man exhibition was organised during a period of war and social upheaval. His imagery is spiritual and allegorical. It may appear disconnected from contemporary politics. But Blake imagined a public role for art. In connection with his watercolour of angels hovering over the body of Christ, on display here, he wrote: ‘The times require that every one should speak out boldly; England expects that every man should do his duty, in Arts, as well as in Arms, or in the Senate’.

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing the recreation of the 1809 exhibition. From left to right on the wall were: Satan calling up his Legions (1800-1805, out of shot); The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan (c. 1805-1809); The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth (1805); and The Bard, from Gray (? 1809)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Frederick Adcock (British, 1864-1930)

William Blake’s house, Soho, London

1912

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

Birthplace of William Blake at No. 28 Broad (now Broadwick) Street, Soho, London. Demolished to make way for a block of flats.

28 Broad Street

Blake’s exhibition was held in the first-floor rooms of 28 Broad Street. The plasterwork and window surrounds were later 19th-century additions. In 1809 Blake’s sister, brother and his wife lived at this address and ran the hosiery and haberdashery shop on the ground floor.

“The execution of my Designs, being all in Water-colours, (that is in Fresco) are regularly refused to be exhibited by the Royal Academy, and the British Institution has, this year, followed its example, and has effectually excluded me by this Resolution … it is therefore become necessary that I should exhibit to the Public, in an Exhibition of my own, my Designs, Painted in Watercolours. If Italy is enriched and made great by RAPHAEL, if MICHAEL ANGELO is its supreme glory, if Art is the glory of a Nation, if Genius and Inspiration are the great Origin and Bond of Society, the distinction my Works have obtained from those who best understand such things, calls for my Exhibition as the greatest of Duties to my Country.”

William Blake, from ‘[Advertisement of] Exhibition of Paintings in Fresco, Poetical and Historical Inventions’, 1809

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Satan calling up his Legions (from John Milton’s Paradise Lost) (installation views)

1800-1805

Tempera and gold leaf on canvas

533 × 496 mm

National Trust Collections, Petworth House, (The Egremont Collection)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Spiritual Form of Nelson Guiding Leviathan

c. 1805-9

Tempera and gold on canvas

762 x 625 mm

Tate. Purchased 1914

Blake showed this painting in his 1809 exhibition. It was exhibited alongside The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth. He provided a long commentary on his ‘spiritual forms’ of both Pitt and Nelson. The recently-deceased Prime Minster William Pitt and naval hero Admiral Nelson had both led Britain in the war against France. Blake shows these national figures guiding biblical monsters bringing chaos and destruction to the world. The symbolism used is complex. In the picture of Nelson ‘The Nations of the Earth’ are shown as contorted figures enveloped by the serpent. A figure of colour in chains lies collapsed at the bottom. He appears to be freed of the serpent’s coils, perhaps suggesting that such destruction could also lead to new freedoms and spiritual rebirth.

This work is cracked and damaged because Blake used a thin canvas and chalk-based ground. The ground layer has darkened due to the conservation treatment of ‘glue’ lining; this is only suitable for oil paintings. Layers of glue in some of Blake’s paints have also darkened. The orange tonality comes from remnants of a discoloured varnish. The contraction of the glue-rich layers and the movement of the thin canvas has created stress, causing cracking.

Gallery label, October 2019

Blake provided a long commentary on his ‘spiritual forms’ of Pitt and Nelson. The recently deceased Prime Minister William Pitt and naval hero Admiral Nelson had both led Britain in the war against France. Blake shows these national figures guiding biblical monsters bringing chaos and destruction to the world. The symbolism is complex. In the picture of Nelson ‘The Nations of the Earth’ are show as contorted figures enveloped by the serpent. A figure of colour in chains lies collapsed at the bottom. He appears to be freed of the serpent’s coils, perhaps suggesting that such destruction could also lead to new freedoms and spiritual rebirth.

Wall text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth

1805

Tempera and gold on canvas

740 x 627 mm

Tate. Purchased 1882

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Spiritual Form of Pitt Guiding Behemoth

1805

Tempera and gold on canvas

740 x 627 mm

Tate. Purchased 1882

Wikipedia Commons, Public Domain

The subject of this picture is the prime minister, William Pitt. Blake showed this work in his exhibition in 1809, describing Pitt as ‘that Angel who, pleased to perform the Almighty’s orders, rides on the whirlwind, directing the storms of war.’

Pitt had led Britain into war against France after the 1789 Revolution. Blake saw him as one ‘ordering the Reaper to reap the Vine of the Earth, and the Plowman to plow up the Cities and Towers’. The words reflect Blake’s apocalyptic vision of war. The huge beast, Behemoth, is under Pitt and at his command.

Gallery label, December 2004

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing paintings from the 1809 exhibition

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Understanding the objectives behind Blake’s exhibition is far from straightforward. Although this display of sixteen works could be considered as a retrospective exhibition, Blake seems to have had several principal aims. Both the exhibition advertisement issued by Blake and the text of the Descriptive Catalogue itself make clear that the works on display were for sale. At the same time Blake was promoting and seeking subscriptions for his engraving of the Canterbury Pilgrims (issued in 1810). Moreover, the exhibition displayed Blake’s painting of Chaucer’s Canterbury Pilgrims (Pollok House, Glasgow) as a deliberate challenge to Thomas Stothard’s rival version of the same subject, The Pilgrimage to Canterbury 1806-1807 (Tate). Blake complained that his works were not accepted by the two most important exhibition venues of the time, the Royal Academy and the British Institution, because they were in the form of watercolours (rather than oil paintings). That might seem to be motivation for setting up this independent show. However, his works had been accepted at the Royal Academy on six different occasions, the last time being the year before his 1809 exhibition. And the exhibition was promoting what Blake called his latest invention: the ‘portable fresco’ (a kind of tempera painting). Blake explained that he could enlarge such fresco works and decorate public buildings. The Spiritual Form of Nelson and The Spiritual Form of Pitt (nos. I and II in the Descriptive Catalogue) were intended as monuments to the heroes of his country. This aspiration, expressed amidst the Napoleonic wars, at a time of rampant nationalism when several public monuments were commissioned and executed by sculptors, shows that Blake was hoping to gain a state commission. He thus associated his fresco productions with patriotic works and the advancement of the English School of art.

Above all, however, I believe that Blake’s exhibition was intended to present Blake as a painter, and the ‘inventor’ of subjects and techniques. He asserted unequivocally that this was an exhibition of ‘paintings’ or ‘pictures’ and designated them as ‘poetical and historical inventions’. His portable fresco, for example, as Aileen Ward has argued, was Blake’s attempt, ‘to circumvent the Academy prejudice against watercolour’ in the hope of being elected at the Academy as a painter.

Extract from Kostantinos Stefanis. “Reasoned Exhibitions: Blake in 1809 and Reynolds in 1813,” in Tate Papers no.14 Autumn 2010 on the Tate website [Online] Cited 26/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Bard, from Gray (installation view)

? 1809

Tempera and gold on canvas

Tate. Purchased 1920

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

A bad iPhone photo I know but it gives you an idea of how dark these paintings were

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Bard, from Gray

? 1809

Tempera and gold on canvas

Tate. Purchased 1920

This tempera has greatly altered since it was painted. Blake used a very thin, white, preparatory layer of chalk and glue. This was impregnated with more glue during a conservation ‘lining’ treatment more appropriate to an oil painting. This reduced the effect of transparent colours over a white background, and displaced some details painted in shell gold. Blake’s paint medium has also darkened greatly. The opaque red vermilion used for the line of blood, glazed over with madder lake, has survived better than blue areas.

Gallery label, September 2004

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing Blake’s work The Virgin and Child in Egypt (1810)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Virgin and Child in Egypt (installation views)

1810

Tempera on canvas

Lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This painting demonstrates Blake’s enduring ambition to work on a larger scale. He adopted the ‘Tüchlein’ technique of 16th-century Netherlandish painting, using tempera (glue-based paint) on linen. Blake had seen such paintings on the London art market. It is one of four life-size figure paintings done for Thomas Butts in 1810.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Virgin and Child in Egypt

1810

Tempera on canvas

Lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing Blake’s work An Allegory of the Spiritual Condition of Man (? 1811)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

An Allegory of the Spiritual Condition of Man (installation views)

? 1811

Ink and tempera on canvas

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

This is the largest surviving painting by Blake. The title is not Blake’s, and the subject matter remains open to interpretation. The symmetrical composition evokes large-scale European church paintings of the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

A new kind of man

After years of obscurity, Blake enjoyed a burst of creativity in the last ten years of his life. In 1818 he met a younger, more business-savvy artist, John Linnell. Together with fellow artists Samuel Palmer and John Varley, Linnell provided Blake with employment, friendship and a new sense of recognition.

Buoyed by their material and moral support, Blake produced some of his most extraordinary works. He completed his last and most ambitious illuminated book, Jerusalem, in 1820. He also found new purchasers for his older books and relief-etchings. He created a series of ‘visionary heads’ to indulge Varley’s spiritualist interests. For Linnell he made a long series of large and vivid watercolours illustrating Dante’s Divine Comedy and engravings for the biblical Book of Job, undertaken in the antiquated style he had always admired.

Blake spent his last years living with Catherine in modest accommodation in Fountain Court off the Strand, with a view onto the Thames. For the younger, more materially successful artists who gathered around him, he represented an ideal of creative integrity and spiritual authenticity. Their memories of him have been crucial in shaping modern perceptions of the artist. An influential 1863 biography drew on Blake’s followers’ recollections of him as ‘a new kind of man, wholly original’.

Text from the Tate website

Installation views of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing in bottom image at second right, Capaneus the Blasphemer (1824-1827) and at fourth right, Cerberus (1824-1827)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Capaneus the Blasphemer

1824-1827

Illustration for The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (Inferno XIV, 46-72)

Pen and ink and watercolour over pencil and black chalk, with sponging and scratching out

374 x 527 mm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Cerberus

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the National Gallery and donations from the Art Fund, Lord Duveen and others, and presented through the the Art Fund 1919

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Cerberus, the terrifying three-headed monster, guards the circle of Hell where gluttons are punished.

Blake drew this design with charcoal as well as pencil and, later, pen and ink. The distant flames of Hell are contrasts of deep red vermilion, a brownish-pink lake pigment that is probably brazilwood, and yellow gamboge. Brazilwood was one of the cheaper and less popular red/pink lake colours. Blake was always careful not to overlay colours or drawing media. This served him in good stead here because, as he undoubtedly knew, charcoal tends to absorb a lot of colour from red lakes.

Gallery label, September 2004

Cerberus is the horrifying three-headed canine monster shown in Blake’s late illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, painted between 1824-27. This refers to Dante’s Inferno, canto 6 verses 12-24, where Dante and Virgil enter the Third Circle, in which gluttons are punished. Blake is true to his source, except that he adds a cave to signify the weight of the material world. There are two versions of this painting: this in the Tate, and another in The National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia.

Cerberus is a good example of the redeployment of pre-Christian mythology into Christian beliefs: it was originally the guardian of the Underworld, and prevented those within from escaping back to the earthly world. It even features in the twelve labours of Heracles (Hercules), in which he captured Cerberus. Dante – with Virgil’s explicit involvement – incorporates it into his Christian concepts of the afterlife.

Most recently, Cerberus has been used in a more faithful transliteration from the Greek as Kerberos, a computer network authentication protocol. Such are the changes that have taken place in human mythology.

Hoakley. “Tyger’s eye: the paintings of William Blake, 16 – A miscellany,” on The Electric Light Company website December 28, 2016 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

Cerberus, cruel monster, fierce and strange,

Through his wide threefold throat, barks as a dog

Over the multitude immersed beneath.

His eyes glare crimson, black his unctuous beard,

His belly large, and claw’d the hands, with which

He tears the spirits, flays them, and their limbs

Piecemeal disparts. Howling there spread, as curs, ~

Under the rainy deluge, with one side

The other screening, oft they roll them round,

A wretched, godless crew.

The Divine Comedy

The last three years of Blake’s life were dominated by a major commission from Linnell. This was to illustrate The Divine Comedy by medieval Italian poet Dante Alighieri. This epic poem describes a journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise.

Blake threw himself into the task and apparently learned Italian especially. The young artist Samuel Palmer observed him at work on the watercolours, ‘hard working on a bed covered with books… like one of the Antique patriarchs, or a dying Michael Angelo.’

In his designs Blake uses colour to convey the transition from dark, menacing Hell to luminous Paradise. No other British artist since Flaxman had attempted to illustrate the poem in its entirety. Sadly the project, totalling 102 watercolours and seven engravings, remained unfinished at Blake’s death. Even in its unfinished state, this series demonstrates the power of Blake’s imagination, his unceasing creative energy and technical skill.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of the exhibition William Blake at Tate Britain, London showing work from Blake’s The Divine Comedy

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Inscription over the Gate (installation view)

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

527 × 374 mm

Tate

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Here Dante and his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, stand before the gates of Hell. The sublime landscape is populated by souls trapped in alternating circles of fire and ice.

Three quarters of Blake’s Divine Comedy illustrations depict Hell. Displayed nearby are Blake’s interpretations of its resident beasts and the various painful fates suffered by sinners. A corrupt Pope is plunged into a fiery pit, and a thief, Agnello Brunelleschi, undergoes a grotesque mutation, becoming half-man, half-serpent.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Inscription over the Gate

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

527 × 374 mm

Tate

In his Divine Comedy, Dante describes the pilgrimage he made with the poet Virgil, travelling into Hell, up the Mountain of Purgatory to reach Paradise at last. Entering the Gate of Hell was a moment when Dante (in red) wept with fear.

Dante describes the ‘dim’ colours which contribute to his terror. Blake’s dark shadows of pure black pigment next to areas of unpainted white paper contribute to this. He used Prussian blue for the blue areas, and indigo blue mixed with yellow for the green foliage, so that they contrast. The blue, green and vermilion red do not overlap.

Gallery label, September 2004

Through me you pass into the city of woe:

Through me you pass into eternal pain:

Through me among the people lost for aye.

Justice the founder of my fabric moved:

To rear me was the task of Power divine,

Supremest Wisdom, and primeval Love.

Before me things create were none, save things

Eternal, and eternal I endure.

All hope abandon, ye who enter here.

Such characters, in colour dim, I mark’d

Over a portal’s lofty arch inscribed.

Dante is being led by Virgil, the Roman poet, through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. Here they are shown entering the Gate of Hell. Once inside, they shall first pass through the region where the souls of the uncommitted (those who lived their lives without doing anything notably good or bad) reside. They shall then be ferried by Charon across the river Acheron into Hell proper. Virgil is the right-hand figure in blue, Dante the left-hand one in grey.

Notice how the greenery framing the outside of the gate contrasts with the bleak panorama of fire and ice inside. If you look carefully you can see tiny figures in torment on the hills. These successive hills represent the different circles of hell, where the souls of people guilty of different sins are punished in an appropriate manner. Those guilty of the sin of lust, for example, are buffeted about by the winds of passion and desire in the second circle.

Text from “William Blake’s illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy,” on the Tate website [Online] Cited 27/01/2020

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Serpent Attacking Buoso Donati (installation view)

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the National Gallery and donations from the Art Fund, Lord Duveen and others, and presented through the the Art Fund 1919

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Serpent Attacking Buoso Donati

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Ink and watercolour on paper

Tate. Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the National Gallery and donations from the Art Fund, Lord Duveen and others, and presented through the the Art Fund 1919

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

In Hell, Dante and Virgil see a thief, in the guise of a serpent ‘all on fire’, preparing to attack another thief, named Buoso de’Donati.

Here Blake’s figures show subtle effects of light and shade, particularly in their flesh tones. He used small brushstrokes of red, blue and black for this, laying the colours side by side rather than mixing them. The robber Donati (right) is about to be punished by being turned into a serpent. Blake’s technique and colour give form to his figure, but the blue also shows human life draining away into coldness.

Gallery label, August 2004

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Lawn with the Kings and Angels (installation view)

1824-1827

Illustration for The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (Purgatorio VII, 64-90 and VIII, 22-48 and 94-108)

Ink and watercolour over black chalk and traces of graphite, with sponging on paper

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1920

through the the Art Fund 1919

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Lawn with the Kings and Angels

1824-1827

Illustration for The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (Purgatorio VII, 64-90 and VIII, 22-48 and 94-108)

Ink and watercolour over black chalk and traces of graphite, with sponging on paper

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1920

Purgatorio VII, 64-90 and VIII, 22-48 and 94-108. The poets are now accompanied by Virgil’s fellow Mantuan, the poet Sordello and have come to a lawn scooped out from the mountainside. Here they see a group of Negligent Rulers singing sacred songs. Two angels appear with blunted, flaming swords to guard the kings from a serpent. Dante describes the richly coloured grass and flowers, but Blake shows the kings in a grove of trees, the symbol of error.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Matilda and Dante on the Banks of the Lethe with Beatrice on the Triumphal Chariot (installation views)

1824-1827

From Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy

Graphite, ink and watercolour on paper

Lent by The British Museum, London

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, Matilda is a beautiful woman who represents the active life of the soul. She stands on the Earthly Paradise side of the river Lethe, and offers to answer Dante’s questions. She tells him to look at Beatrice’s procession, which can be seen in Blake’s painting behind Matilda. Blake illustrated Dante’s Divine Comedy in 1824, a commission he undertook in 1824 at the request of John Linnell. A reverse Newtonian rainbow hangs above the scene.

John Linnell (British, 1792-1882)

William Blake wearing a hat

c. 1825

Graphite on paper

The Syndics of the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Linnell made this seemingly spontaneous portrait of Blake during one of their regular walks on Hampstead Heath, to the north of London. Linnell, who lived by the Heath, was Blake’s most important friend during his final years. Their families became close and through Linnell Blake’s social circle expanded. He met landscape artist John Constable at Linnell’s house. Looking at Constable’s drawing of trees on Hampstead Heath, Blake exclaimed that it was ‘not drawing, but inspiration!‘

Wall text

John Linnell (British, 1792-1882) and John Varley (British, 1778-1842)

The Blake / Varley Sketchbook (installation view)

1819

Book

Private collection

Varley gave Blake sketchbooks to record his nocturnal visions. This page shows Rowena, a Saxon queen renowned for her beauty.

The ‘Visionary Heads’

In October 1819 Blake began a series of extraordinary sketches of spirits. He claimed to have seen and even spoken with the spirits in ‘visions’. John Varley encouraged him. He provided Blake with drawing materials to make these so-called ‘Visionary Heads’. He also attended the séance-like sessions when the spirits appeared to Blake. Varley described sitting with Blake ‘from ten at night till three in the morning sometimes slumbering and sometimes waking, but Blake never slept’. According to Linnell, Varley believed in Blake’s visions ‘more than even Blake himself’.

Over a period of about six years Blake made over 100 ‘Visionary Heads’. They depict real historical figures such as medieval kings, as well as legendary characters like Merlin and a range of imagined beasts. Blake’s contemporaries debated whether his nocturnal visions were a sign of mental ill health or a charming quirk.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Ghost of a Flea (installation views)

c. 1819

Tempera heightened with gold on mahogany

214 x 162 mm

Tate. Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson 1949

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Ghost of a Flea

c. 1819

Tempera heightened with gold on mahogany

214 x 162 mm

Tate. Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson 1949

The Ghost of a Flea is one of Blake’s most bizarre and famous characters. As the vision appeared to Blake he is said to have cried out: ‘There he comes! his eager tongue whisking out of his mouth, a cup in his hand to hold blood, and covered with a scaly skin of gold and green.’ John Varley watched Blake make the original sketch of this character. He also owned this painting showing the creature on a stage, flanked by curtains with a shooting star behind. Varley was a keen astrologer. He paid Linnell to engrave Blake’s drawings, including the Flea, to illustrate his Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy (1828).

Wall text from the exhibition

Artist and astrologer John Varley encouraged Blake to sketch the figures, called ‘visionary heads’, who populated his visions. This image is the best known. While sketching the flea, Blake claimed it told him that fleas were inhabited by the souls of bloodthirsty men, confined to the bodies of insects because, if they were the size of horses, they would literally drain the population. Their bloodthirsty nature is shown by the eager tongue flicking at the ‘blood’ cup it carries. This intense disorientating image, the stuff of delirium and nightmare, taps into the unconscious, internalised sublime.

William Blake, “The Ghost of a Flea c. 1819-20,” in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Ghost of a Flea

c. 1819

Graphite on paper

Private collection

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Creation of Eve

1822

Illustration for Paradise Lost by John Milton (VIII, 452-77)

Pen and brown and black ink and watercolour over pencil and black chalk, with stippling and sponging

50.4 × 40.7cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1920

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Creation of Eve (installation views)

1822

Illustration for Paradise Lost by John Milton (VIII, 452-77)

Pen and brown and black ink and watercolour over pencil and black chalk, with stippling and sponging

50.4 × 40.7cm (sheet)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1920

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils (installation views)

c. 1826

Ink and tempera on mahogany

Tate. Presented by Miss Mary H. Dodge through the Art Fund 1918

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils

c. 1826

Ink and tempera on mahogany

Tate. Presented by Miss Mary H. Dodge through the Art Fund 1918

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

The first owner of this tempera was George Richmond, a member of the ‘Ancients’. This was a circle of young artists who gathered around Blake in the 1820s.

In the biblical text this work refers to, Satan is given permission by God to torture Job in order to test the limits of his faith. The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve and the set of engravings to the Old Testament Book of Job (displayed nearby) reprise work that Blake had made for Thomas Butts 20 years earlier.

Wall text from the exhibition

The biblical ‘Book of Job’ addresses the existence of evil and suffering in a world where a loving, all-powerful God exists. It has been described as ‘the most profound and literary work of the entire Old Testament’. In ‘Job’, God and Satan discuss the limits of human faith and endurance. God lets Satan force Job to undergo extreme trials and tribulations, including the destruction of his family. Despite this, as God predicted, Job’s faith remains unshaken and he is rewarded by God with the restoration of his health, wealth and family. Here Blake shows Satan torturing Job with boils.

William Blake, “Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils c. 1826,” in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication, January 2013.

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve (installation views)

c. 1826

Ink, tempera and gold on mahogany

Tate. Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson 1949

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

In the 1820s Blake’s work took on a richer appearance. He began to use more vibrant colour and to apply gold leaf more frequently. Another new practice was his use of a mahogany support. These innovations were perhaps inspired by Northern European art of the late 15th century, which adapted ideas of the Italian Renaissance. Blake and Linnell often visited such works in private and public collections across London. Blake’s use of gold may have been facilitated by the fact that one of his Fountain Court neighbours was a gilder.

Wall text

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve

c. 1826

Ink, tempera and gold on mahogany

Tate. Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson 1949

Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Pilgrim’s Progress

John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come (1678) was a popular religious text in Blake’s day. It is not known why Blake embarked on this series of illustrations. They were left unfinished at his death.

Pilgrim’s Progress tells the story of a challenging journey. Taking place in the realm of a dream, it follows the character Christian as he travels from the City of Destruction (earth) to the Celestial City (heaven) in the hope of unburdening himself of his sins.

Although it contains some of Blake’s most imaginative and original imagery, Pilgrim’s Progress has not received the same level of attention as his other late projects. One reason for this may be that Catherine, Blake’s wife, is thought to have been involved in colouring the illustrations. For nearly all their married life Catherine helped Blake to print and hand-colour his works. Her creative and practical influence is only beginning to be fully appreciated.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Christian in the Arbour

1824-1827

Illustration to Pilgrim’s Progress

Watercolour and ink over graphite and chalk on paper

Private collection

Reader! lover of books! lover of heaven,

And of that God from whom all books are given,

Who in mysterious Sinais awful cave

To Man the wond’rous art of writing gave,

Again he speaks in thunder and in fire!

Thunder of Thought, & flames of fierce desire:

Even from the depths of Hell his voice I hear,

Within the unfathomd caverns of my Ear.

Therefore I print; nor vain my types shall be:

Heaven, Earth & Hell, henceforth shall live in harmony

I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Mans

I will not Reason & Compare: my business is to Create

William Blake

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

Jerusalem, plate 28, proof impression, top design only

1820

Relief etching with pen and black ink and watercolour on medium, smooth wove paper

111 x 159 mm

Yale Center for British Art (New Haven, USA)

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

The Sea of Time and Space (installation views)

1821

Ink, watercolour and body colour on gesso ground on paper

National Trust Collections, Arlington Court (The Chichester Collection)

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

The subject of this detailed and richly coloured painting is a mystery. It appears to relate to the theme of choice. The kneeling figure has been identified as divine inspiration and imagination. Its title comes from Blake’s poem Vala, or the Four Zoas and was only applied in 1949.

It is shown in its original frame, which was made by John Linnell’s father, the framer James Linnell. It is thought that Colonel John Palmer Chichester, of Arlington Court, may have purchased it directly from Blake.

Wall text from the exhibition

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

‘Europe’ Plate i: Frontispiece, ‘The Ancient of Days’ (installation views)

1827

Relief etching with ink and watercolour on paper

232 x 120mm

The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

William Blake (British, 1757-1827)

‘Europe’ Plate i: Frontispiece, ‘The Ancient of Days’

1827

Relief etching with ink and watercolour on paper

232 x 120mm

The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

Tate Britain’s major William Blake retrospective ends with what is believed to be the artist’s final work. On his deathbed, Blake is said to have coloured this impression of Ancient of Days 1827, claiming with satisfaction that it was ‘the best I have ever finished’. This ominous figure was created as a frontispiece for Blake’s 1794 prophetic book Europe a Prophecy. Along with its partner publication America, a Prophecy 1793, these epic and highly symbolic texts relate to the French revolution and revolutionary war in America respectively. Blake created several known versions of the work in his lifetime, including one thought coloured by his wife Catherine. One of Blake’s own favourite works, the image has since been embraced in popular culture and has been used to cover books and albums in recent years. It is reported that upon finishing this version the artist turned to Catherine, a constant source of support and inspiration, and proclaimed ‘you have ever been an angel to me’. He died only days later on 12 August 1827.

Text from Tate Britain

In his final days Blake is said to have coloured an impression of this work. He is reported to have claimed it ‘the best I have ever finished’. Though small in size it has become one of Blake’s best-known images. Its central figure is Urizen. He represents the scientific quest for answers. Urizen measures the world below with his golden compass. This act symbolises a threat to freedom of thought, imagination and creativity. For Blake, these were the cornerstones of human happiness.

Wall text from the exhibition

The divine white-beard, reaching down from his burning disc to measure the Earth below with his shining dividers. For all the force and similarity, this is not in fact God but Blake’s Urizen, the despised personification of Reason and Science.

Laura Cumming. “William Blake review – a rousing call to arms,” on The Guardian website Sun 15 Sep 2019 [Online] Cited 18/01/2020

Tate Britain

Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

United Kingdom

Phone: +44 20 7887 8888

Opening hours:

10.00am – 18.00pm daily

Tate Britain website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870 Lewis Carroll (British, Daresbury, Cheshire 1832 - 1898 Guildford) '[Alice Liddell]' June 25, 1870](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/lewis-carroll-alice-liddell.jpg?w=650&h=741)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-surveyor-a.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854 Unknown photographer (American) '[Surveyor]' c. 1854](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-surveyor-b.jpg?w=650&h=758)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Classical Head]' probably 1839](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/bayard-classical-head.jpg?w=650&h=715)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-a.jpg?w=650&h=783)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-b.jpg?w=650&h=760)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-c.jpg?w=650&h=798)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-d.jpg?w=650&h=844)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-e.jpg?w=650&h=800)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-f.jpg?w=650&h=771)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-g.jpg?w=650&h=830)

![Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s Unknown artist. '[Carte-de-visite Album of Collaged Portraits]' 1850s-1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/anon-collaged-portraits-h.jpg?w=650&h=761)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855 Unknown artist (American) '[Studio Photographer at Work]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/unknown-artist-american-studio-photographer-at-work-c-1855.jpg?w=650&h=807)

![Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s Unknown artist (American) '[Boy Holding a Daguerreotype]' 1850s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/unknown-american-active-1850s-boy-holding-a-daguerreotype-1850s.jpg?w=650&h=759)

![Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863 Carleton E. Watkins (American, 1829-1916) '[California Oak, Santa Clara Valley]' c. 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/watkins-california-oak-santa-clara-valley.jpg?w=650&h=805)

![Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855 Pietro Dovizielli (Italian, 1804-1885) '[Spanish Steps, Rome]' c. 1855](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/dovizielli-spanish-steps.jpg?w=650&h=846)

![Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853 Edouard Baldus (French (born Prussia), 1813-1889) '[Amphitheater, Nîmes]' c. 1853](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/baldus-amphitheater.jpg?w=840)

![Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s Lewis Dowe (American, active 1860s-1880s) '[Dowe's Photograph Rooms, Sycamore, Illinois]' 1860s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/lewis-dowe-dowes-photograph-rooms-sycamore-illinois-1860s.jpg?w=840)

![E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863 E. & H. T. Anthony (American) '[Specimens of New York Bill Posting]' 1863](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/e-h-t-anthony-specimens-of-new-york-bill-posting-1863.jpg?w=840)

![Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857 Felice Beato (British (born Italy), Venice 1832-1909 Luxor) and James Robertson (British, 1813-1881) [Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem] 1856-1857](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/beato-dome.jpg?w=840)

![R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s R.C. Montgomery (American, active 1850s) '[Self-Portrait (?)]' 1850s](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2020/07/r.c.-montgomery-self-portrait-1850s.jpg?w=650&h=1068)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'South West View of the Parthenon [on the Acropolis, Athens, Greece]' 31 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/south-west-view-of-the-parthenon-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Portions of the Frieze of the Parthenon [Athens, Greece]' 31 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/portions-of-the-frieze-of-the-parthenon-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'The Caryatid porch of the Erechtheum [Athens, Greece]' 30 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-caryatid-porch-of-the-erechtheum-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Acropolis and Temple of Jupiter Olympus [Olympieion, Athens]' 31 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/acropolis-and-temple-of-jupiter-olympus-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'The Temple of Jupiter from the north west [Baalbek, Lebanon]' 3 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-temple-of-jupiter-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'The Temple of the Sun and Temple of Jupiter [Baalbek, Lebanon]' 4 May 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-temple-of-the-sun-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'The Colossi on the plain of Thebes [Colossi of Memnon]' 17 Mar 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-colossi-on-the-plain-of-thebes-web.jpg?w=840)

![Joseph Albert (1825-86) (photographer) '[The Prince of Wales with Prince Louis of Hesse, and companions, in Munich, February 1862]' 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-prince-of-wales-and-companions-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'View through the Great Gateway into the Grand Court of the Temple of Edfou [Temple of Horus, Edfu]' 14 Mar 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/view-through-the-great-gateway-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'The Great Propylon of the Temple at Edfou [Pylon of the Temple of Horus, Edfu]' 14 Mar 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/the-great-propylon-of-the-temple-at-edfou-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Tombs of the Memlooks at Cairo [Mausoleum and Khanqah of Emir Qawsun]' 25 Mar 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/tombs-of-the-memlooks-at-cairo-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Mosque of Mehemet Ali [Mosque of Muhammad Ali, Cairo]' 8 March 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/mosque-of-mehemet-ali-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Fountain in the Court of the Mosque of Mehemet Ali [Mosque of Muhammad Ali, Cairo]' 3 Mar 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/fountain-in-the-court-of-the-mosque-web.jpg?w=840)

![Francis Bedford (1815-94) (photographer) 'Garden of Gethsemane [Jerusalem]' 2 Apr 1862](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/garden-of-gethsemane-web.jpg?w=840)