Exhibition dates: 29th June – 10th October, 2021

Curator: Mazie Harris

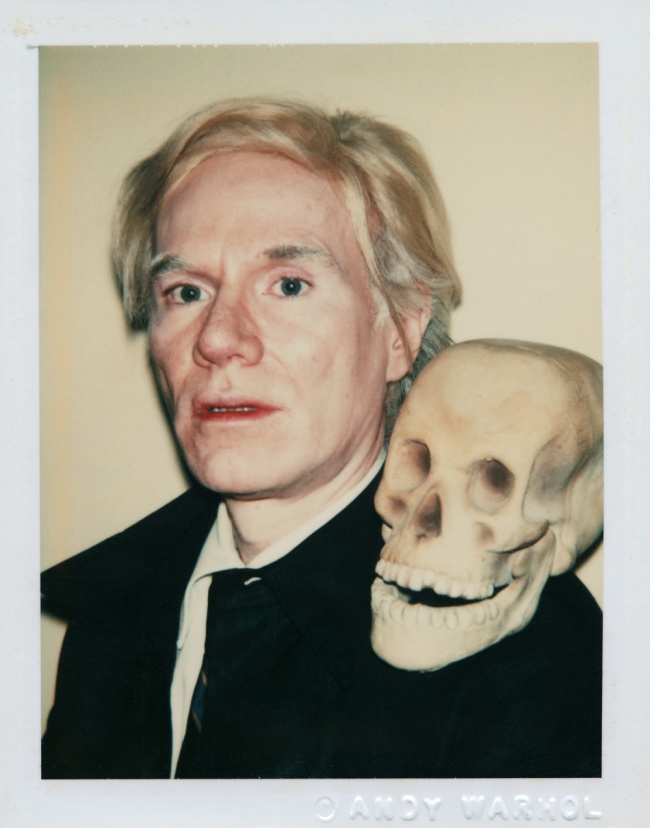

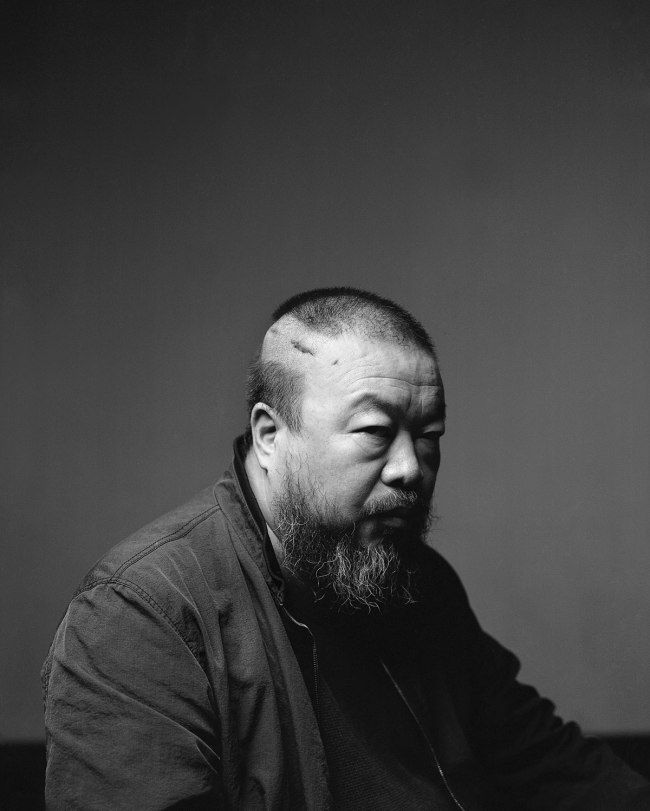

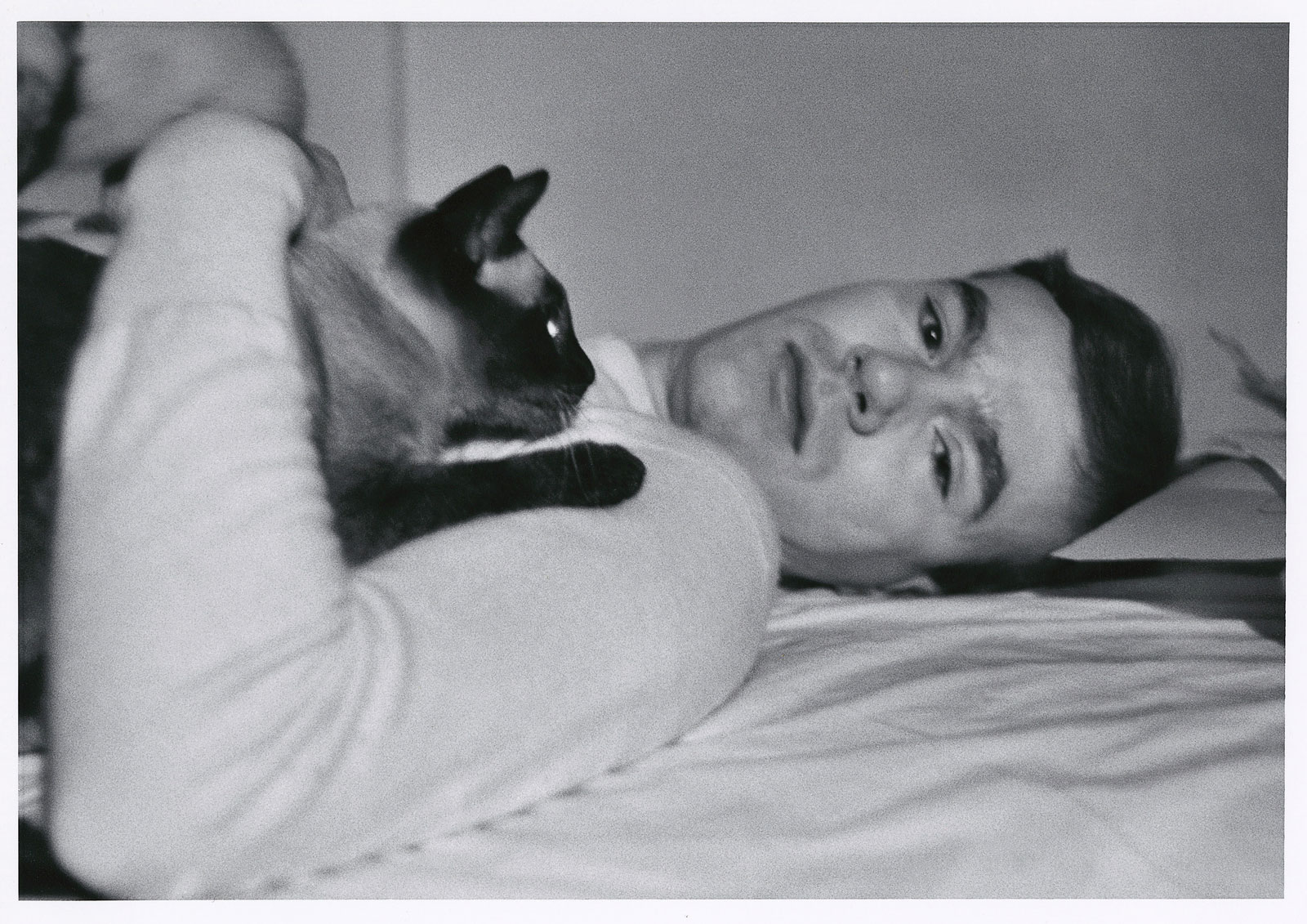

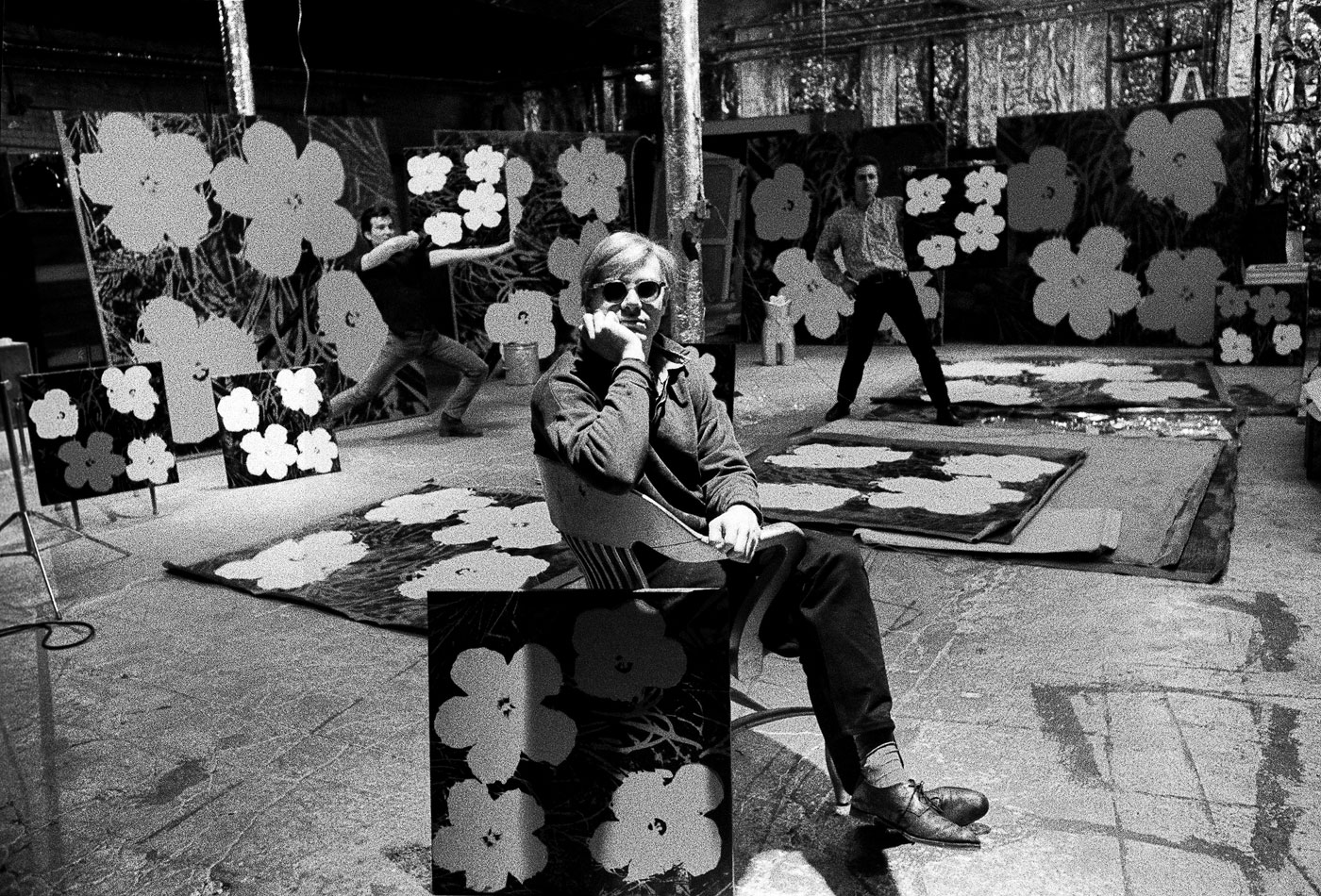

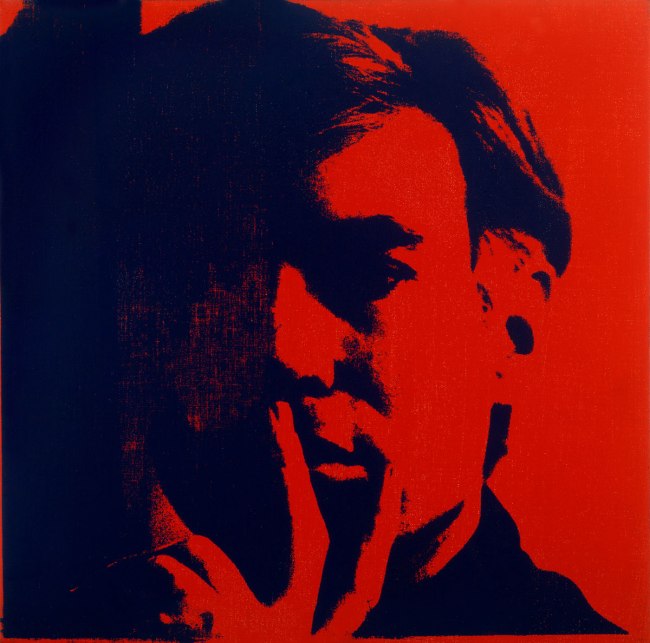

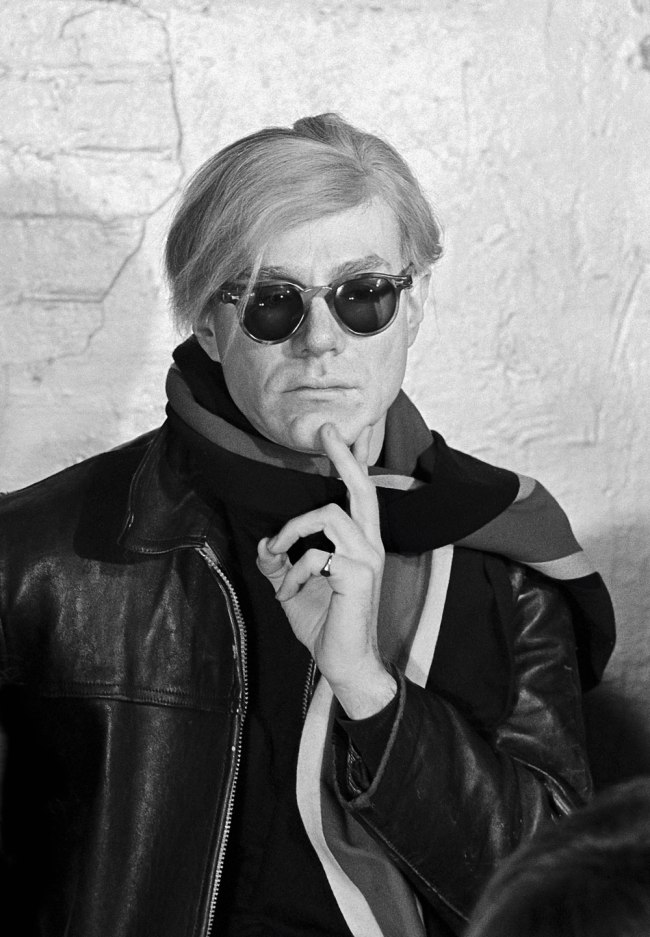

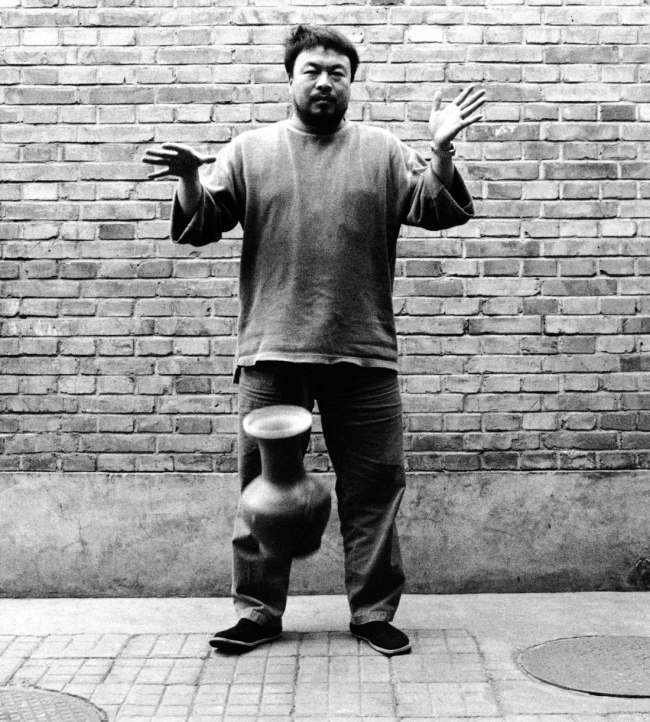

David Wojnarowicz in 1988

Please note, this photograph is not in the exhibition

Speaking up when others are silent

This one-room exhibition seems like a missed opportunity.

I note the observation of Anne Wallentine: “In Focus: Protest, a one-room exhibition at the Getty Center, focuses on palatable images of protest. There are no disturbing images of the police’s violent attacks on protesters during the June 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, for example, or of self-immolations protesting the Vietnam War. On the one hand, we don’t need to see violence to understand injustice. But this subject deserves a much deeper and broader show to explore the important power dynamics of protest – and of documenting it – than the Getty’s somewhat muddled march through the lowlights of American history.”1

Although I haven’t seen the exhibition I have been able to gather together numerous photographs from installation shots of the show. The exhibition focuses heavily on the civil rights photographs of the 1960s with sporadic abortion, women’s lib, Vietnam War, contemporary Black Lives Matter and metaphorical images standing in for actual protest photographs (such as the photographs of Robert Frank). As Wallentine observes, the subject deserves a much deeper and broader show to explore the important power dynamics of protest, and of documenting it.

America has a long history of protest stretching back to its very beginning, such as the Boston Tea Party in 1773. But thinking about the photography of protest in America – where are the cartes de visit of slavery abolitionists such as Sojourner Truth or Frederick Douglass, the photographs of protests for women’s suffrage, after the Stonewall Riots, against the lack of funding for HIV/AIDS, for gun legislation, photographs of protests for Native American enfranchisement, marches for equal rights, anti-nuclear protests, Iraq War protests, climate change protests, and the worldwide Occupy movement?

What are issues and the politics involved with documenting protest, both for an against, as an expression of the photographers own beliefs? How does the presence of photographers affect how people “play up” to the camera? Does the photographer participate in the protest or stand aside and just document? How is documenting a form of protest in itself? How are these images then made propaganda and to what ends? What is the difference between the vernacular photography of protest and that of a professional photojournalist? How are both disseminated and what is the difference of this impact?

How is the framing of protest photography undertaken in a system – and here I am thinking, for example, of the selective cropping, editing and addition of text in photo essays by professional photographers such as Gordon Parks for Life magazine – and how do we, as viewers, recognise that the systems in which the works are viewed often obscure the networks in which they are created and operate… that is, structures that sit around those pictures re/presentation in galleries or newspapers, journals.

Essentially, in the power of the image, what lies in and beyond the frame of reference – in terms of the technologies of production, technologies of sign systems, technologies of power and technologies of the self2 – has an “affect” upon the reception and interpretation of images, their inculcation in memory through repetition, their performativity, their intertextuality and their promulgation in the world as acts of resistance and freedom, both from the point of view of the photographer and the viewer.

The one image that is my favourite protest photograph “of all time” can be seen above. To my knowledge, this photograph is not included in the exhibition. Taken by an anonymous photographer in 1988 it shows an anonymous man at a protest rally (evidenced by the placard in the background top right) wearing a jacket emblazoned with words in white capital letters “IF I DIE OF AIDS – FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A” over the pink triangle, symbol of homosexuals in the Nazi concentration camps later reclaimed as a positive symbol of self-identity for various LGBTQ identities. The F.D.A. referred to is the United States Food and Drug Administration which is responsible for protecting the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs and biological products… at the time dragging their feet over AIDS research.

The anonymous man is, in fact, American artist and activist David Wojnarowicz who died at the age of 37 in 1992, four years after the photograph was taken, of AIDS-related complications.

“… during the plague years, he watched his best friends die horribly, while religious leaders pontificated against safe-sex education and politicians mooted quarantine on islands.

It filled him with rage, the brutality and the waste. He writes: “I want to throw up because we’re supposed to quietly and politely make house in this killing machine called America and pay taxes to support our own slow murder, and I’m amazed that we’re not running amok in the streets and that we can still be capable of gestures of loving after lifetimes of all this.” …

“It is exhausting, living in a population where people don’t speak up if what they witness doesn’t directly threaten them,” he writes. Long before the word intersectionality was in common currency, Wojnarowicz was alert to people whose experience was erased by what he called “the pre‑invented world” or “the one-tribe nation”. Politicised by his own sexuality, by the violence and deprivation he had been subjected to, he developed a deep empathy with others, a passionate investment in diversity. During the course of Close to the Knives he touches repeatedly on other struggles, from fighting police brutality towards people of colour to standing up to the erosion of abortion rights. …

As the rallying cry of Aids activists made clear, “Silence = Death”. From the very beginning of his life Wojnarowicz had been subjected to an enforced silencing, first by his father and then by the society he inhabited: the media that erased him; the courts that legislated against him; and the politicians who considered his life and the lives of those he loved expendable.

In Knives he repeatedly explains his motivation for making art as an acute desire to produce objects that could speak, testifying to his presence when he no longer could. “To place an object or piece of writing that contains what is invisible because of legislation or social taboo into an environment outside myself makes me feel not so alone,” he writes. “It is kind of like a ventriloquist’s dummy – the only difference is that the work can speak by itself or act like that magnet to attract others who carried this enforced silence.””3

The jacket that he made and the photograph of it form an intertextual art work, one both (physically) sculptural and photographic, objects that could visibly speak in the world by transgressing the taboo of invisibility, of silence. The photograph was taken by an anonymous photographer of an initially (to the viewer) anonymous man. It then proceeds to transcend its subject … through the projection of the voice of the artist through time, through the knowledge of the story of his own vitality and resistance, now his absence/presence. His protest stands “in eternity” where there is no time. Standing with others, speaking up when others are silent. That is the essence of protest. I just wonder where that jacket is now?

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Anne Wallentine. “A History of Protest Photography That Plays It Too Safe,” on the Hyperallergic website August 18, 2021 [Online] Cited 12/09/2021

2/ Michel Foucault, “Technologies of the Self,” quoted in Luther Martin, Huck Gutman, Patrick Hutton (eds.). Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with Michel Foucault. Tavistock Publications, London, 1988, p. 18.

3/ Olivia Laing. “David Wojnarowicz: still fighting prejudice 24 years after his death,” on the Guardian website, Friday 13 May 2016 [Online] Cited 12/09/2021

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

We are reminded frequently of the power of photographs to propel action and inspire change. During demonstrations photographers take to the streets to record fast-moving events. At other times they bear witness to daily injustices, helping to make them more widely known. This exhibition of images made during periods of social struggle in the United States highlights the myriad roles protest photographs play in shaping our understanding of American life.

In Focus: Protest, a one-room exhibition at the Getty Center, focuses on palatable images of protest. There are no disturbing images of the police’s violent attacks on protesters during the June 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, for example, or of self-immolations protesting the Vietnam War. On the one hand, we don’t need to see violence to understand injustice. But this subject deserves a much deeper and broader show to explore the important power dynamics of protest – and of documenting it – than the Getty’s somewhat muddled march through the lowlights of American history. …

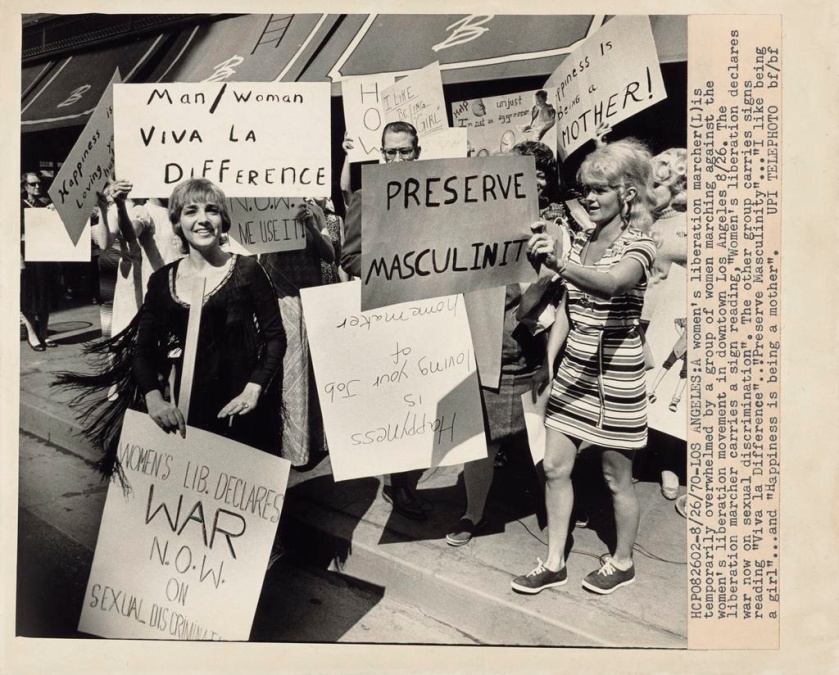

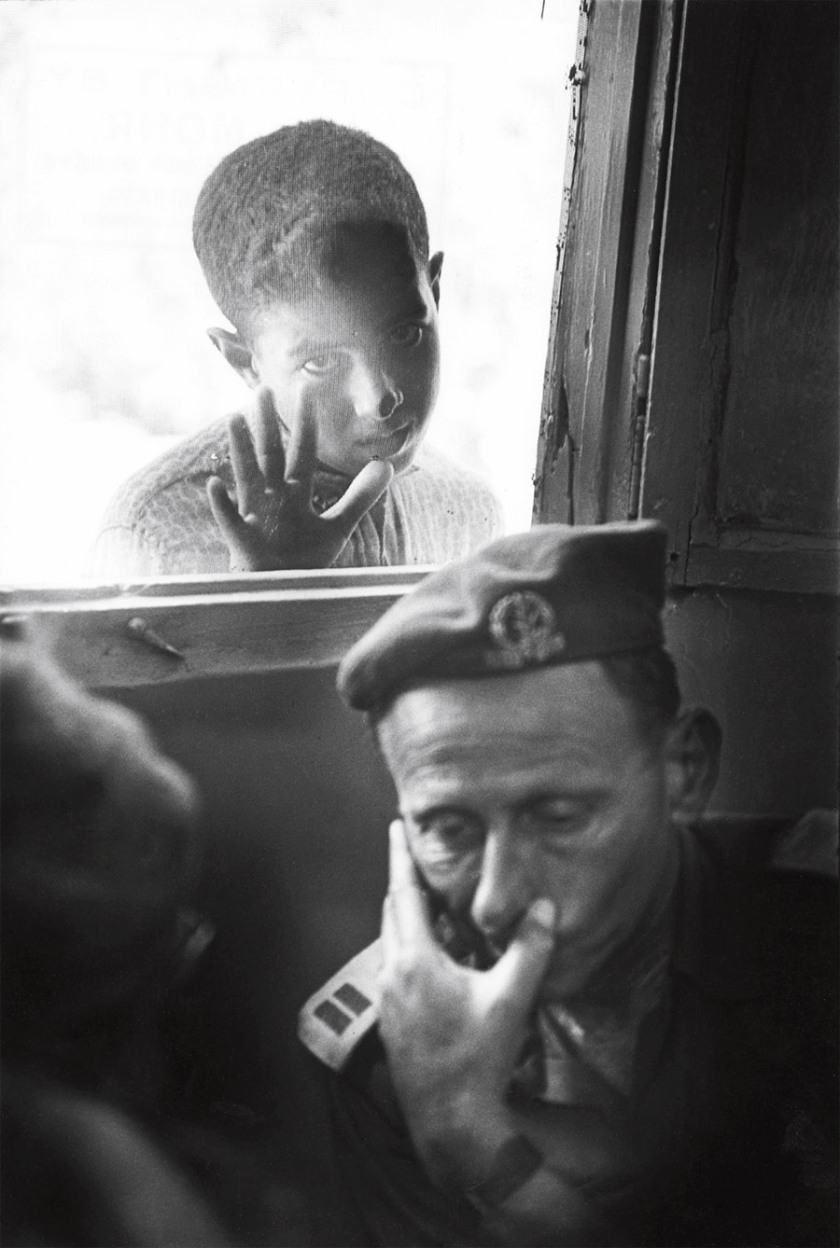

… depicting individuals carries new risks now. Contemporary protest photographers have to navigate the dangers of photo recognition technology for their subjects – notably, Kris Graves’s 2020 photo depicts a luminous memorial to George Floyd projected and graffitied onto a Confederate statue, rather than an image of identifiable marchers [see below]. At the very least, the issue deserves mention in the wall text to contextualize current photography amid this threat to human rights and the tricky role photographers have to navigate while recording and participating in protests. Documenting can be a form of protest, but it can be used against its subjects, too. The exhibition text, however, tends to swerve away from engaging with the complexities of history, mentioning the passage of the 19th Amendment and Voting Rights Act 1965 without referencing the continued struggles to ensure voting access in marginalized communities. It does provide images of counter-protest during the Vietnam War and women’s liberation movement of the 1970s, but these only sharpen the desire for a better understanding of the ebb and flow of human rights efforts into the present.

Anne Wallentine. “A History of Protest Photography That Plays It Too Safe,” on the Hyperallergic website August 18, 2021 [Online] Cited 12/09/2021

Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s)

[Women’s Campaign Train for Hughes]

1916

Gelatin silver print

18.7 × 24.9cm (7 3/8 × 9 13/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Adger Cowans (American, b. 1936)

Malcolm X Speaks at a Rally in Harlem at 115th St. & Lennox Ave., New York

September 7, 1963

Gelatin silver print

16.2 × 23.5cm (6 3/8 × 9 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Adger Cowans

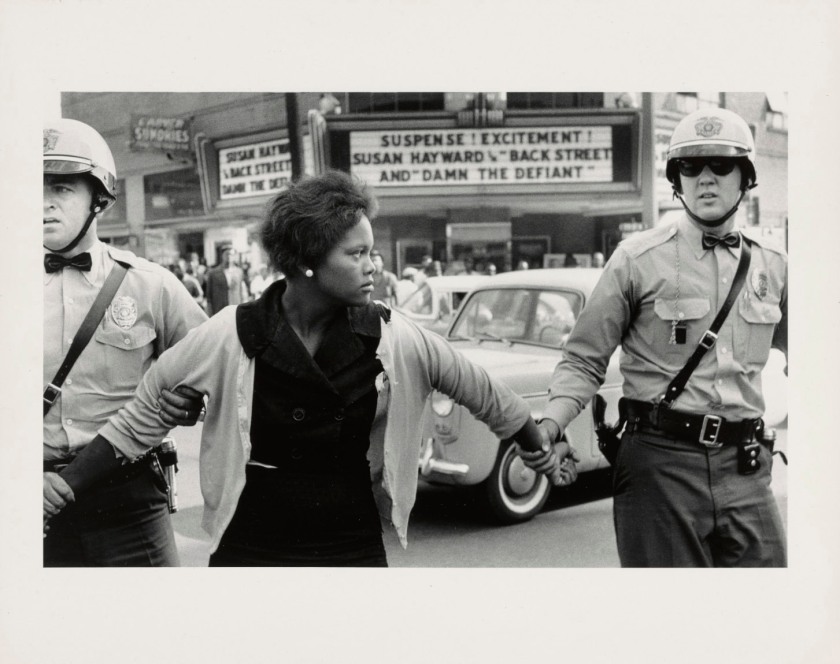

Bruce Davidson (American, born 1933)

Birmingham, Alabama

Negative 1963; print 1970-1979

Gelatin silver print

19.9 × 31.1 cm (7 13/16 × 12 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

An African-American woman is arrested by two Caucasian police officers, each holding her by her arms. In the background is a theatre marquee, bearing the signs for the movies, “Back Street” and “Damn the Defiant.”

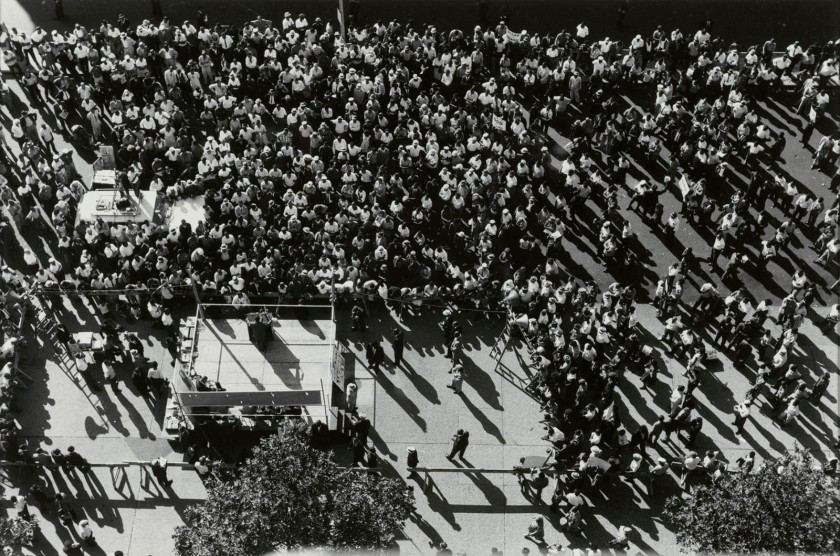

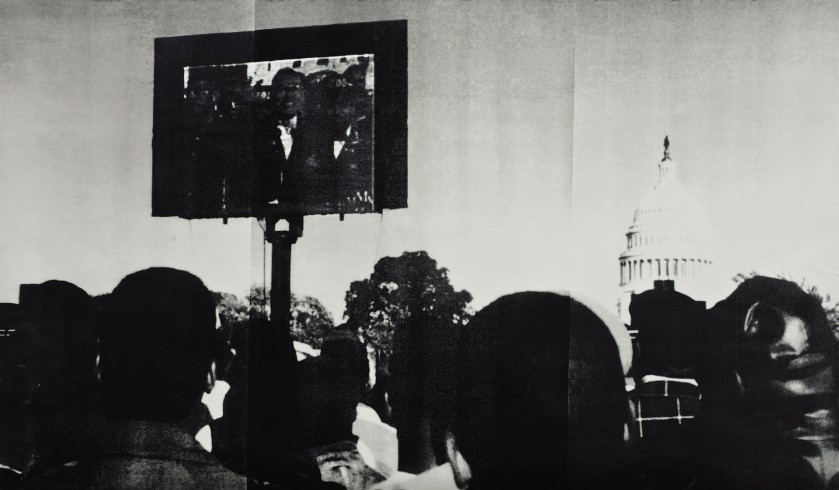

Leonard Freed (American, 1929-2006)

March on Washington, Washington, D.C.

August 28, 1963

Gelatin silver print

26.5 × 38.7cm (10 7/16 × 15 1/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Leonard Freed / Magnum Photos

Robert (Bob) Adelman (American, 1930-2016)

Washington, D.C., Cheering crowd during speeches at historic March on Washington

1963

Gelatin silver print

27.9 × 35.6cm (11 × 14 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Bob Adelman/Magnum Photos

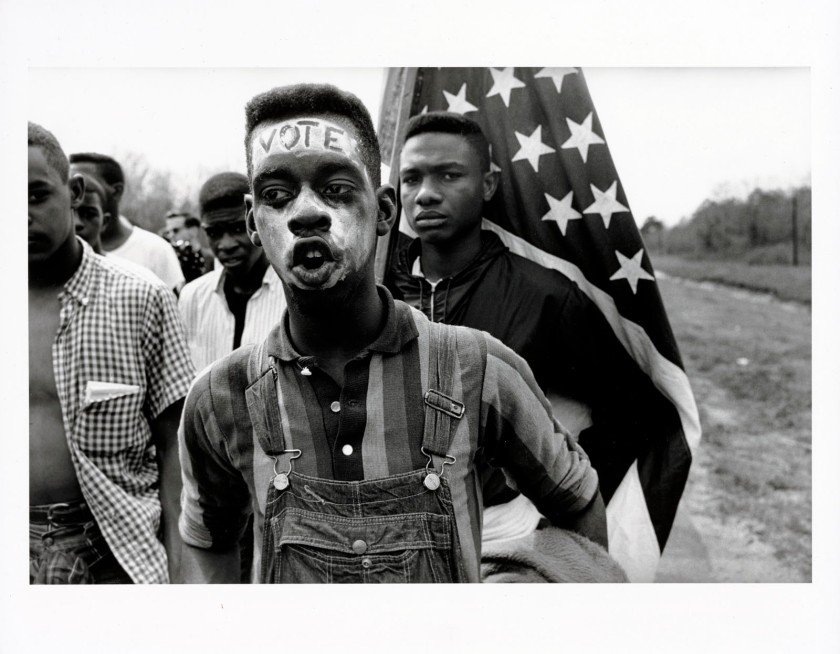

Bruce Davidson (American, b. 1933)

March from Selma, Alabama

Negative 1965; printed later

Gelatin silver print

21.7 × 32.8cm (8 9/16 × 12 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Photographs not only capture a nation’s values and beliefs but also help shape them. Camera in hand, photographers often take to the streets, recording protests and demonstrations or bearing witness to daily injustices to make them more widely known. Such images have inspired change for generations.

The late United States Congressman John Lewis emphasised the crucial role photography played in the civil rights struggles of the 1960s. “The unbelievable photographs published in newspapers and magazines… brought people from around the globe to small Southern towns to join the movement,” he said. “These photographs told us that those who expressed themselves by standing in unmovable lines… must be looked upon as the found mothers and fathers of a new America.”

This exhibition highlights how photographers have recorded periods of social struggle and transformation in the United States. Amid the country’s current and ongoing efforts to address and rectify injustice and systemic racism, and as the United States continues to grapple with how best to forge a new and better future, these images help us consider the myriad roles photography plays in shaping our understanding of American life.

Wall text from the exhibition

Voting Rights Act 1965

Voting Rights Act, U.S. legislation (August 6, 1965) that aimed to overcome legal barriers at the state and local levels that prevented African Americans from exercising their right to vote under the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) to the Constitution of the United States. The act significantly widened the franchise and is considered among the most far-reaching pieces of civil rights legislation in U.S. history.

In the 1950s and early 1960s the U.S. Congress enacted laws to protect the right of African Americans to vote, but such legislation was only partially successful. In 1964 the Civil Rights Act was passed and the Twenty-fourth Amendment, abolishing poll taxes for voting for federal offices, was ratified, and the following year Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson called for the implementation of comprehensive federal legislation to protect voting rights. The resulting act, the Voting Rights Act, suspended literacy tests, provided for federal approval of proposed changes to voting laws or procedures (“preclearance”) in jurisdictions that had previously used tests to determine voter eligibility (these areas were covered under Sections 4 and 5 of the legislation), and directed the attorney general of the United States to challenge the use of poll taxes for state and local elections. An expansion of the law in the 1970s also protected voting rights for non-English-speaking U.S. citizens. Sections 4 and 5 were extended for 5 years in 1970, 7 years in 1975, and 25 years in both 1982 and 2006.

The Voting Rights Act resulted in a marked decrease in the voter registration disparity between white and Black people. In the mid-1960s, for example, the overall proportion of white to Black registration in the South ranged from about 2 to 1 to 3 to 1 (and about 10 to 1 in Mississippi); by the late 1980s racial variations in voter registration had largely disappeared. As the number of African American voters increased, so did the number of African American elected officials. In the mid-1960s there were about 70 African American elected officials in the South, but by the turn of the 21st century there were some 5,000, and the number of African American members of the U.S. Congress had increased from 6 to about 40. In what was widely perceived as a test case, Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District Number One v. Holder, et al. (2009), the Supreme Court declined to rule on the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), however, the Court struck down Section 4 – which had established a formula for identifying jurisdictions that were required to obtain preclearance – declaring it to be unjustified in light of changed historical circumstances. Eight years later, in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021), the Court further weakened the Voting Rights Act by finding that the law’s Section 2(a) – which prohibited any voting standard or procedure that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color” – was not necessarily violated by voting restrictions that disproportionately burden members of racial minority groups.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Voting Rights Act,” on the Britannica website last updated July 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 12/09/2021.

John Simmons (American, b. 1950)

Unite or Perish, Chicago, Illinois

1968

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© John Simmons

Simmons began his career at 15 as a photographer for the oldest African American-owned newspaper, The Chicago Daily Defender in 1965. Over his decades long career, he’s photographed icons of the Civil Rights Movement, turbulent protests and demonstrations, famed musicians and poignant intimate moments of everyday life. “I’m glad to see photographs I took back in my teens are still relevant today,” he says. …

Two of Simmons’ photographs are featured in “In Focus: Protest,” “an exhibition featuring images made during periods of social struggle in the U.S. and highlighting the myriad roles protest photographs play in shaping our understanding of American life,” says Mazie Harris, assistant curator in the department of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum. “With this exhibition we aim to give visitors a place to think about some of the ways photographers have brought attention to efforts to address and rectify injustice.” …

“My position on protest is interesting,” says Simmons. “My father was much older than my mother and when Harriet Tubman died my father was around 12 or 13 so that puts me in close relationship to slavery and to people who were arounds slaves. My great grandmother saw Abraham Lincoln and my great aunt was babysat by former slaves. I picked up a camera in 1965, the first year African Americans were allowed to vote. That was behind those eyes the first day I pressed a shutter. So in reality, every photograph I take is a protest photo.”

John Simmons quoted in Steve Simmons. “Photographer John Simmons, ‘Chronicler Of The Civil Rights Movement,’ Featured In Three Exhibits,” on the Linkedin website August 4, 2021 [Online] Cited 11/09/2021.

Robert Flora (American, 1929-1986)

A Women’s Liberation Marcher Is Temporarily Overwhelmed by a Group of Women Marching against the Women’s Liberation Movement in Downtown Los Angeles

August 26, 1970

Gelatin silver print with typed caption

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of the Flora Family

Reproduced with permission via Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bill Owens (American, born 1938)

Untitled

early 1970s

Gelatin silver print

19.2 × 21.5cm (7 9/16 × 8 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Gift of Robert Shimshak and Marion Brenner

© Bill Owens

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989)

American Flag

1977

Gelatin silver print

35.3 × 35.3cm (13 7/8 × 13 7/8 in.)

Jointly acquired by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, with funds provided by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

“Mapplethorpe evoked the frayed character of American ideals during a period when equal rights for gay men and women in the United States seemed nearly unimaginable.”

The J. Paul Getty Museum presents In Focus: Protest, an exhibition featuring images made during periods of social struggle in the United States, and highlighting the myriad roles protest photographs play in shaping our understanding of American life. The exhibition is on view at the Getty Center Museum June 29 – October 10, 2021.

Photographs not only capture a nation’s values and beliefs but also help shape them. Camera in hand, photographers often take to the streets, recording protests and demonstrations or bearing witness to daily injustices to make them more widely known. Such images have inspired change for generations.

“In Focus: Protest reminds us of the ability of photographs to both document and propel action,” says Mazie Harris, assistant curator of photographs at the Museum. “With this exhibition we aim to give visitors a place to think about some of the ways that photographers have brought attention to efforts to address and rectify injustice.” Among the works on view are images by well-known artists including Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965), Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946-1989), and L.A.-based cinematographer and artist John Simmons (American, born 1950). The exhibition also includes resonant images by photographers Robert Flora (American, 1929-1986), William James Warren (American, born 1942), An-My Lê (American, born 1960), and a 2020 photograph by Kris Graves (American, born 1982).

Press release from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895-1965)

Pledge of Allegiance, Raphael Weill Elementary School, San Francisco

Negative April 20, 1942; print about 1960s

Gelatin silver print

34 × 25.6cm (13 3/8 × 10 1/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Children’s symbol of hope and innocence can also be tied to their shielding from the “outside world”. Here we have a young Japanese girl reciting the American pledge of allegiance with much determination and passion, all while the United States government would take Japanese Americans into internment camps weeks later, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Trolley – New Orleans

1955

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

“America is an interesting country… but there is a lot here that I do not like and that I would never accept. I am also trying to show this in my photos.” ~ Robert Frank

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Railway Station, Memphis, Tennessee

1955

Gelatin silver print

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Fred W. McDarrah (American, 1926-2007)

Jose Rodriguez-Soltero Burned a Flag in a New York Happening

April 8, 1966

Gelatin silver print

34.8 × 25.8cm (13 11/16 × 10 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Estate of Fred W. McDarrah

William James Warren (American, b. 1942)

Robert F. Kennedy and César Chávez Celebrate Mass as Chávez Breaks a Twenty-Five Day Fast, Delano, California

1968

Gelatin silver print

31.2 × 21.6cm (12 5/16 × 8 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of William James Warren

© William James Warren

Mary Ellen Mark (American, 1940-2015)

Vietnam Pro Demonstration

1968

Gelatin silver print

24.3 × 16.7cm (9 9/16 × 6 9/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Mary Ellen Mark Foundation

Louis Draper (American, 1935-2002)

Fannie Lou Hamer, Mississippi

1971

Gelatin silver print

22.86 × 15.56cm (9 × 6 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In 1971 Essence magazine sent Draper on assignment to Mississippi to photograph civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer. This portrait appeared with the article “Fannie Lou Hamer Speaks Out,” in the October issue. Known for her fearlessness and strength in the midst of violence and intimidation, Hamer had been arrested and severely beaten by police in 1963 for her work on voter registration drives. She gained national attention when she returned to her activism in the mid-1960s, and this photograph visually distills her voice: “Today I don’t have any money, but I’m freer than the average white American ’cause I know who I am. I know what I’m about, and I know that I don’t have anything to be ashamed of.”

Anonymous text from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts website

Anthony Friedkin (American, b. 1949)

These Are the Thoughts that Set Fire to Your City

1993

Gelatin silver print

32.6 × 22cm (12 13/16 × 8 11/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Sue and Albert Dorskind

© Anthony Friedkin

This photograph was taken following the 1992 Rodney King Riots that happened across Los Angeles.

Rodney King (American, 1965-2012)

Rodney Glen King (April 2, 1965 – June 17, 2012) was an African-American man who was a victim of police brutality. On March 3, 1991, King was beaten by LAPD officers during his arrest, after a high-speed chase, for driving while intoxicated on I-210. An uninvolved individual, George Holliday, filmed the incident from his nearby balcony and sent the footage to local news station KTLA. The footage showed an unarmed King on the ground being beaten after initially evading arrest. The incident was covered by news media around the world and caused a public furor.

At a press conference, announcing the four officers involved would be disciplined, and three would face criminal charges, Los Angeles police chief Daryl Gates said: “We believe the officers used excessive force taking him into custody. In our review, we find that officers struck him with batons between fifty-three and fifty-six times.” The LAPD initially charged King with “felony evading”, but later dropped the charge. On his release, he spoke to reporters from his wheelchair, with his injuries evident: a broken right leg in a cast, his face badly cut and swollen, bruises on his body, and a burn area to his chest where he had been jolted with a stun gun. He described how he had knelt, spread his hands out, and slowly tried to move so as not to make any “stupid moves”, being hit across the face by a billy club and shocked. He said he was scared for his life as they drew down on him.

Four officers were eventually tried on charges of use of excessive force. Of these, three were acquitted, and the jury failed to reach a verdict on one charge for the fourth. Within hours of the acquittals, the 1992 Los Angeles riots started, sparked by outrage among racial minorities over the trial’s verdict and related, longstanding social issues. The rioting lasted six days and killed 63 people, with 2,383 more injured; it ended only after the California Army National Guard, the Army, and the Marine Corps provided reinforcements to re-establish control.

The federal government prosecuted a separate civil rights case, obtaining grand jury indictments of the four officers for violations of King’s civil rights. Their trial in a federal district court ended on April 16, 1993, with two of the officers being found guilty and sentenced to serve prison terms. The other two were acquitted of the charges. In a separate civil lawsuit in 1994, a jury found the city of Los Angeles liable and awarded King $3.8 million in damages.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Glenn Ligon (American, b. 1960)

Screen

1996

Silkscreen on canvas

213.36 x 365.76cm (84 x 144 in.)

Taking up an entire wall of a four-walled exhibit is Ligon’s “Screen”, where he took and enlarged a newspaper photograph from the Million Man March in Washington, DC. “Ligon has noted that while the march was meant to inspire African American unity, women and gay men were excluded,” says the photograph’s blurb. Ligon states, “I’m interested in what citizenship is in a democratic country… and the responsibilities that come with it.” On the video screen is Louis Farrakhan, a controversial organiser of the Million Man March.

Text from Julianna Lozada. “”In Focus Protest”: A Close Look at the New Getty Center Exhibit,” on the Karma Compass website July 14, 2021 [Online] Cited 11/09/2021

Million Man March

The Million Man March was a large gathering of African-American men in Washington, D.C., on October 16, 1995. Called by Louis Farrakhan, it was held on and around the National Mall. The National African American Leadership Summit, a leading group of civil rights activists and the Nation of Islam working with scores of civil rights organisations, including many local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (but not the national NAACP) formed the Million Man March Organizing Committee. The founder of the National African American Leadership Summit, Dr. Benjamin Chavis Jr. served as National Director of the Million Man March.

The committee invited many prominent speakers to address the audience, and African American men from across the United States converged in Washington to “convey to the world a vastly different picture of the Black male” and to unite in self-help and self-defence against economic and social ills plaguing the African American community.

The march took place in the context of a larger grassroots movement that set out to win politicians’ attention for urban and minority issues through widespread voter registration campaigns. On the same day, there was a parallel event called the Day of Absence, organised by women in conjunction with the March leadership, which was intended to engage the large population of black Americans who would not be able to attend the demonstration in Washington. On this date, all blacks were encouraged to stay home from their usual school, work, and social engagements, in favour of attending teach-ins, and worship services, focusing on the struggle for a healthy and self-sufficient black community. Further, organisers of the Day of Absence hoped to use the occasion to make great headway on their voter registration drive.

Text from the Wikipedia website

An-My Lê (American born Vietnam, b. 1960)

Fragment VI: General Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard Monuments, Homeland Security Storage, New Orleans, Louisiana

2017

Inkjet print

142.2 × 100.3cm (56 × 39 1/2 in.)

Pier 24 Photography, San Francisco

© An-My Lê courtesy of the Artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

John Simmons (American, b. 1950)

Fight Like a Girl, Los Angeles

Negative 2019; print 2020

Pigment print

24.1 × 38.1cm (9 1/2 × 15 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© John Simmons

Kris Graves (American, b. 1982)

George Floyd Projection, Richmond, Virginia

2020

Inkjet print

40 × 50.1cm (15 3/4 × 19 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916 Underwood & Underwood (American, founded 1881, dissolved 1940s) '[Women's Campaign Train for Hughes]' 1916](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2021/09/underwood-underwood-womens-campaign-train-for-hughes.jpg?w=840)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Silver Liz [Ferus Type]' 1963](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2016/03/exhi032777-web.jpg?w=650&h=652)

![Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965 Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987) 'Screen Test: Edie Sedgwick [ST308]' 1965](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/exhi037605-web.jpg)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/anon-borough-of-clunes-notice-strike-rm-rate-front-no-back3.jpg?w=655&h=441)

![National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/national-photo-company-nd-front1.jpg?w=655&h=421)

![E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/e-b-pike-back2.jpg?w=458&h=656)

![Otto von Hartitzsch. 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883 Otto von Hartitzsch. 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/otto-von-hartitzsch-adelaide-1867-back2.jpg?w=463&h=662)

![Profesor Hawkins. 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875 Profesor Hawkins. 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/professor-hawkins-melbourne-front3.jpg?w=444&h=589)

![J. R. Tanner. 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875 J. R. Tanner. 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/j-r-tanner-1875-front1.jpg?w=408&h=617)

You must be logged in to post a comment.