Exhibition dates: 1st March – 20th May 2018

Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography is curated by Phillip Prodger PhD, Head of Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, London

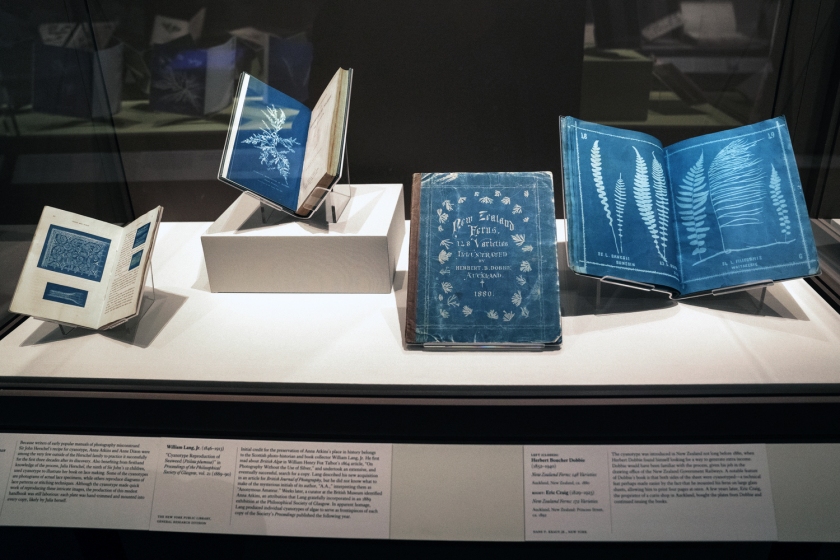

Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography at the National Portrait Gallery, London

A two-part bumper posting on this exhibition, Part 1 featuring the work of Lewis Carroll and our Julia… JMC, Julia Margaret Cameron, the most inventive, audacious and talented photographer of the era. In a photographic career spanning eleven years of her life (1864-1875) what Julia achieved in such a short time is incredible.

“Her style was not widely appreciated in her own day: her choice to use a soft focus and to treat photography as an art as well as a science, by manipulating the wet collodion process, caused her works to be viewed as “slovenly”, marred by “mistakes” and bad photography. She found more acceptance among pre-Raphaelite artists than among photographers.” (Wikipedia)

As with any genius (a person who possesses exceptional intellectual or creative power) who goes against the grain, full recognition did not come until later. But when it does arrive, it is undeniable. As soon as you see a JMC photograph… you know it is by her, it could be by no one else. Her “signature” – closely framed portraits and illustrative allegories based on religious and literary works; far-away looks, soft focus and lighting, low depth of field; strong men (“great thro’ genius”) and beautiful, sensual, heroic women (“great thro’ love”) – is her genius.

There is something so magical about how JMC can frame a face, emerging from darkness, side profile, filling the frame, top lit. Soft out of focus hair with one point of focus in the image. Beautiful light. Just the most sensitive capturing of a human being, I don’t know what it is… a glimpse into another world, a ghostly world of the spirit, the soul of the living seen before they are dead.

Love and emotion. Beauty, beautiful, beatified.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

View part 2 of the posting

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery, London for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“My aspirations are to ennoble Photography and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real & Ideal & sacrificing nothing of Truth by all possible devotion to poetry and beauty.”

Julia Margaret Cameron to Sir John Herschel, 31 December 1864

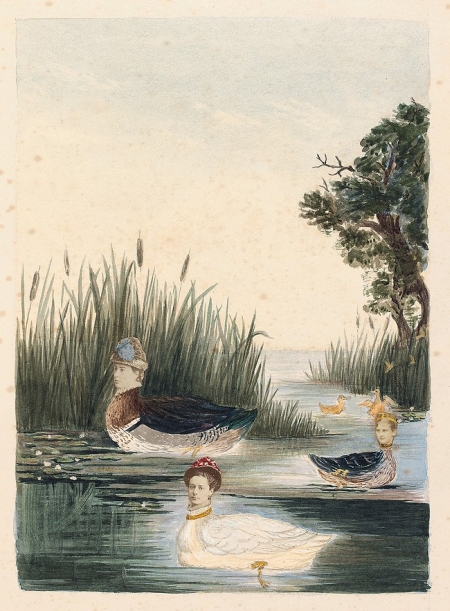

This major exhibition is the first to examine the relationship between four ground-breaking Victorian artists: Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822-1865) and Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875). Drawn from public and private collections internationally, the exhibition features some of the most breath-taking images in photographic history. Influenced by historical painting and frequently associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the four artists formed a bridge between the art of the past and the art of the future, standing as true giants in Victorian photography.

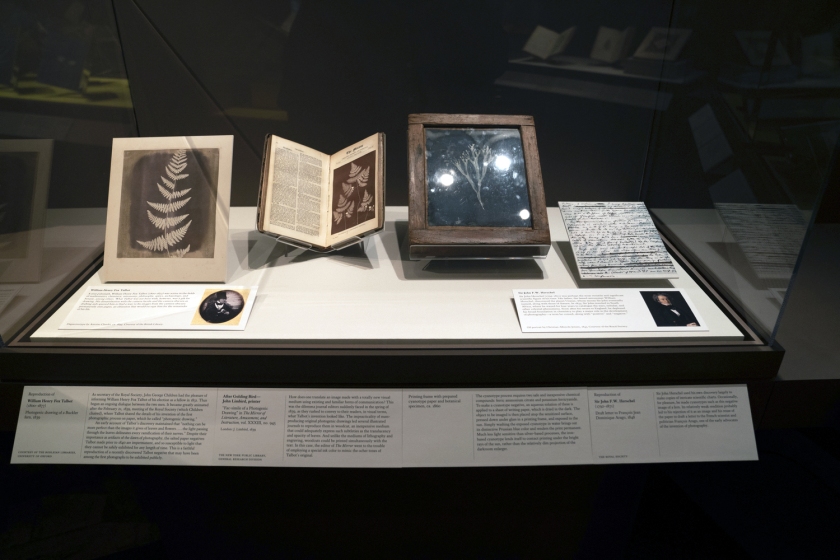

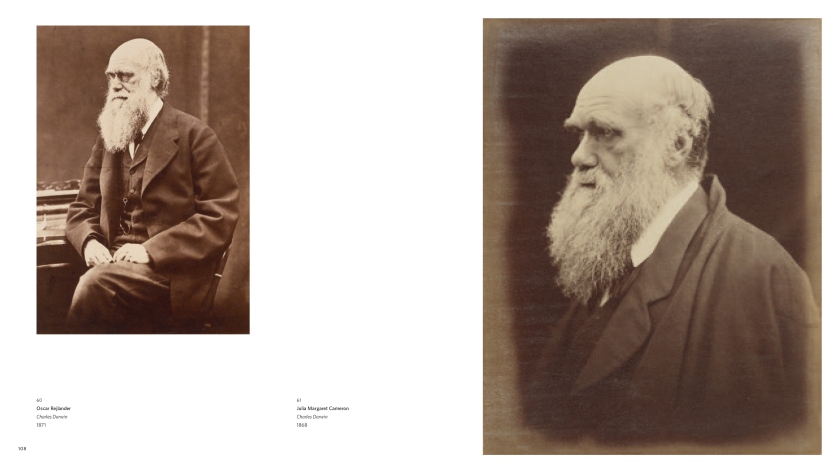

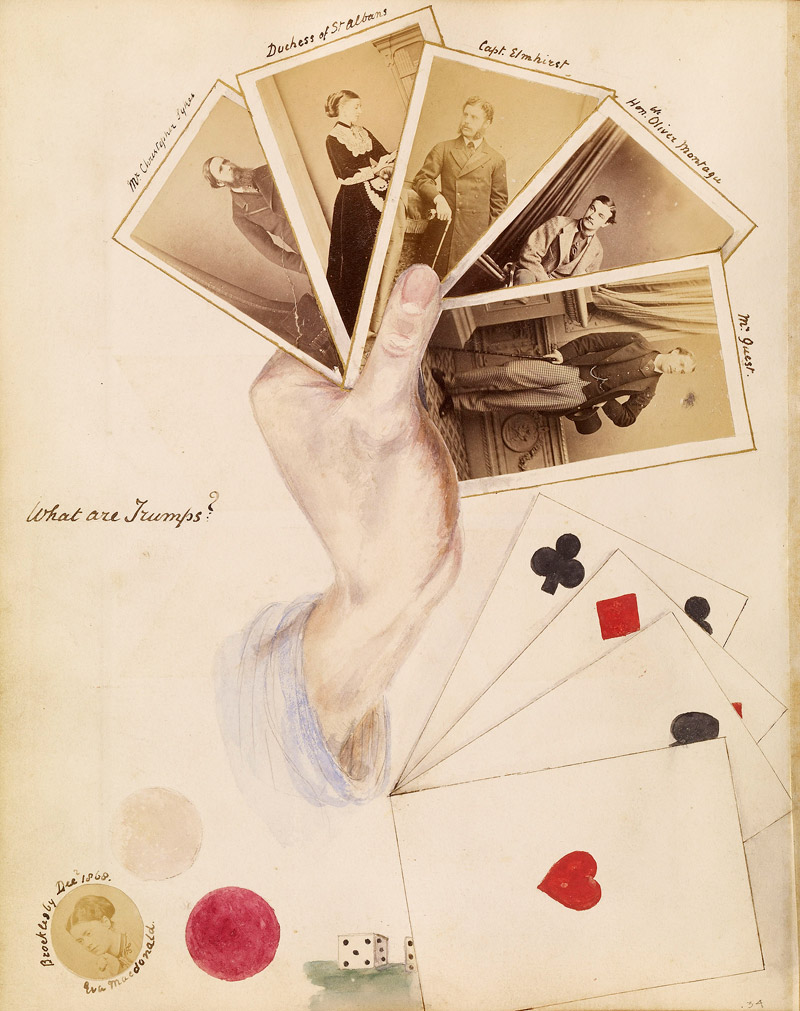

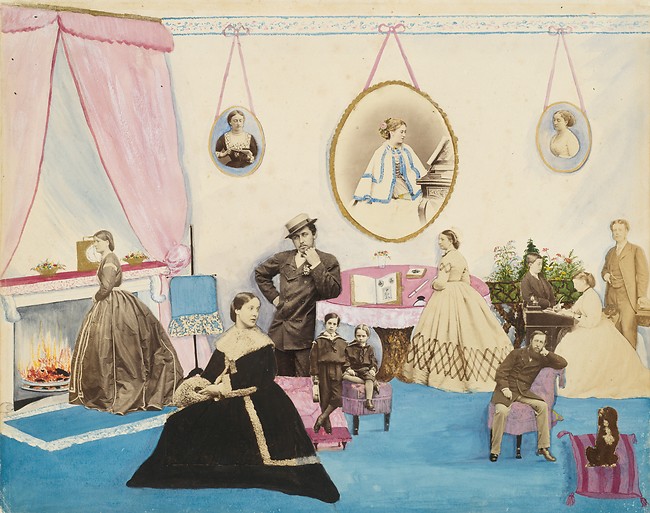

Figure 94 and 95 from the catalogue for the exhibition Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

In 1856, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend Reginald Southey. He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years.

A study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over half of his surviving work depicts young girls, though about 60% of his original photographic portfolio is now missing. Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, boys, and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, and trees. His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden because natural sunlight was required for good exposures.

He also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday, Lord Salisbury, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

By the time that Dodgson abruptly ceased photography (1880, over 24 years), he had established his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, created around 3,000 images, and was an amateur master of the medium, though fewer than 1,000 images have survived time and deliberate destruction. He stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was too time-consuming. He used the wet collodion process; commercial photographers who started using the dry-plate process in the 1870s took pictures more quickly.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Alice Liddell as ‘The Beggar Maid’

also known as King Cophetua’s Bride

Summer 1858

Albumen silver print from glass negative

16.3 x 10.9cm (6 7/16 x 4 5/16in.)

Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005

© Metropolitan Museum of Art

Known primarily as the author of children’s books, Lewis Carroll was also a lecturer in mathematics at Oxford University and an ordained deacon. He took his first photograph in 1856 and pursued photography obsessively for the next twenty-five years, exhibiting and selling his prints. He stopped taking pictures abruptly in 1880, leaving over three thousand negatives, for the most part portraits of friends, family, clergy, artists, and celebrities. Ill at ease among adults, Carroll preferred the company of children, especially young girls. He had the uncanny ability to inhabit the universe of children as a friendly accomplice, allowing for an extraordinarily trusting rapport with his young sitters and enabling him to charm them into immobility for as long as forty seconds, the minimum time he deemed necessary for a successful exposure. The intensity of the sitters’ gazes brings to Carroll’s photographs a sense of the inner life of children and the seriousness with which they view the world.

Carroll’s famous literary works, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1865) and “Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There” (1872), were both written for Alice Liddell, the daughter of the dean of Christ Church, Oxford. For Carroll, Alice was more than a favourite model; she was his “ideal child-friend,” and a photograph of her, aged seven, adorned the last page of the manuscript he gave her of “Alice’s Adventures Underground.” The present image of Alice was most likely inspired by “The Beggar Maid,” a poem written by Carroll’s favourite living poet, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, in 1842. If Carroll’s images define childhood as a fragile state of innocent grace threatened by the experience of growing up and the demands of adults, they also reveal to the contemporary viewer the photographer’s erotic imagination. In this provocative portrait of Alice at age seven or eight, posed as a beggar against a neglected garden wall, Carroll arranged the tattered dress to the limits of the permissible, showing as much as possible of her bare chest and limbs, and elicited from her a self-confident, even challenging stance. This outcast beggar will arouse in the passer-by as much lust as pity. Indeed, Alice looks at us with faint suspicion, as if aware that she is being used as an actor in an incomprehensible play. A few years later, a grown-up Alice would pose, with womanly assurance, for Julia Margaret Cameron.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Alice Liddell

Summer 1858

Wet collodion glass-plate negative

6 x 5 in. (152 x 127mm)

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London and the National Media Museum (part of the Science Museum Group, London)

The fourth of ten children and later the inspiration for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking Glass, Alice Liddell is the most famous of Carroll’s child sitters. Contrary to popular belief, Carroll did not photograph her particularly often, and never photographed her in the nude. Of the 2,600 photographs recorded by Carroll, only twelve solo portraits of Alice are known. By comparison, he made six individual portraits of Alice’s sister, Ina, and forty-five of another favoured sitter, Xie Kitchin (see preceding room).

Wall text

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Ina Liddell

Summer 1858

Albumen print

5 7/8 x 5 in. (150 x 126mm) uneven

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London and the National Media Museum (part of the Science Museum Group, London)

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Edith Mary Liddell; Ina Liddell; Alice Liddell

Summer 1858

Wet collodion glass plate negative

6 x 7 1/8 in. (154 x 181mm)

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Edith Mary Liddell; Ina Liddell; Alice Liddell

Summer 1858

Albumen print

6 1/8 x 6 7/8 in. (156 x 176mm)

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Edith Mary Liddell

Summer 1858

Albumen print

5 7/8 x 7 in. (148 x 177mm) uneven

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Hallam Tennyson, 2nd Baron Tennyson

28 September 1857

Albumen print

5 1/8 x 3 7/8 in. (130 x 99 mm)

Purchased, 1977

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Hallam Tennyson (British, 1852-1928), Alfred Tennyson’s eldest son, was five years old when Carroll photographed him at Monk Coniston Park in the Lake District. Taken while the poet and his family were visiting friends, the portrait shows Hallam standing on a chair, holding what may be a hoop rolling stick. Carroll posed him with his legs crossed – a tricky stance for such a young child to maintain. As an adult, Hallam would marry May Prinsep, Julia Margaret Cameron’s niece. Carroll did make one portrait of Alfred Tennyson during his Lake District trip, but he was determined to make more. In 1864, he visited the Isle of Wight to try to photograph him again, armed with a ‘carpet bag full’ of his photographs to show Cameron and others. He was unable to photograph Tennyson, but Cameron and Carroll staged a ‘mutual exhibition’ in Cameron’s living room. (Wall text)

Hallam Tennyson, 2nd Baron Tennyson, GCMG, PC (11 August 1852 – 2 December 1928) was a British aristocrat who served as the second Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1903 to 1904. He was previously Governor of South Australia from 1899 to 1902.

Tennyson was born in Twickenham, Surrey, and educated at Marlborough College and Trinity College, Cambridge. He was the oldest son of the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and served as his personal secretary and biographer; he succeeded to his father’s title in 1892. Tennyson was made Governor of South Australia in 1899. When Lord Hopetoun resigned the governor-generalship in mid-1902, he was the longest-serving state governor and thus became Administrator of the Government. Tennyson was eventually chosen to be Hopetoun’s permanent replacement, but accepted only a one-year term. He was more popular than his predecessor among the general public, but had a tense relationship with Prime Minister Alfred Deakin and was not offered an extension to his term. Tennyson retired to the Isle of Wight, and spent the rest of his life upholding his father’s legacy.

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

‘Open your mouth, and shut your eyes’ (Edith Mary Liddell; Ina Liddell; Alice Liddell)

July 1860

Wet collodion glass plate negative

10 x 8 in. (254 x 203mm)

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London

The Liddell family arrived at Christ Church, Oxford in 1856, just as Carroll was beginning to take up photography. He and the family became close friends. Henry Liddell served as Dean of the College throughout Carroll’s career, and initially supported his photographic efforts. In 1863, Carroll and the family broke off relations for unknown reasons. Speculation has included disappointment that Carroll went against the family’s wishes by refusing to court their governess or one of the older Liddell children – Ina has been mentioned as a candidate. Carroll was enormously charmed by the Liddell children, all of whom he photographed, and nearly all of whom made their way into Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and other, related writings.

Wall text

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

The Rossetti Family

7 October 1863

Albumen print

6 7/8 x 8 3/4 in. (175 x 222mm)

Given by Helen Macgregor, 1978

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Carroll spent months trying to arrange an introduction to Rossetti (1828-1882) so that he could photograph the famous Pre-Raphaelite painter and poet, and his family. This is one of several photographs he made in the garden of Tudor House, 16 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, during a four-day session in which he photographed the family and some of Rossetti’s artwork, including drawings of his late wife, Elizabeth Siddal.

The relationship between Carroll, Cameron, Hawarden, Rejlander and the Pre-Raphaelites was complex. They had many common friends and associates, and it is believed that several Pre-Raphaelite painters used photographs as studies for their paintings and sculpture. However, all four photographers were attracted to later styles of painting, especially the Spanish and Italian National Portrait Gallery, London Baroque, and the Dutch Golden Age. Led by the cantankerous critic John Ruskin, an associate of Henry Liddell’s at Oxford (Alice Liddell’s father), the Pre-Raphaelites were opposed to such painting, which they considered too literal and mundane.

Wall text

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

7 October 1863

Albumen print

5 3/4 x 4 3/4 in. (146 x 121mm)

Purchased, 1977

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti (12 May 1828 – 9 April 1882), generally known as Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a British poet, illustrator, painter and translator. He founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. Rossetti was later to be the main inspiration for a second generation of artists and writers influenced by the movement, most notably William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. His work also influenced the European Symbolists and was a major precursor of the Aesthetic movement.

Rossetti’s art was characterised by its sensuality and its medieval revivalism. His early poetry was influenced by John Keats. His later poetry was characterised by the complex interlinking of thought and feeling, especially in his sonnet sequence, The House of Life. Poetry and image are closely entwined in Rossetti’s work. He frequently wrote sonnets to accompany his pictures, spanning from The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) and Astarte Syriaca (1877), while also creating art to illustrate poems such as Goblin Market by the celebrated poet Christina Rossetti, his sister. Rossetti’s personal life was closely linked to his work, especially his relationships with his models and muses Elizabeth Siddal, Fanny Cornforth and Jane Morris.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Benjamin Woodward

Late 1850s

Albumen print

8 x 6 in. (203 x 152mm)

Purchased, 1986

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Irish-born architect Benjamin Woodward (1815-1861) is best known for having designed a number of buildings in Cork, Dublin and Oxford in partnership with Sir Thomas Deane and his son Sir Thomas Newenham Deane. Inspired by the writings of critic John Ruskin, his most important buildings include the museum at Trinity College, Dublin (1853-1857). Through Ruskin, Woodward met Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other Pre-Raphaelite artists, whom Woodward employed in 1857 to decorate his recently completed Oxford Union building.

Wall text

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

John Ruskin

6 March 1875

Albumen print

3 1/2 x 2 1/4 in. (90 x 58mm) overall

Given by an anonymous donor, 1973

© National Portrait Gallery, London

John Ruskin (8 February 1819 – 20 January 1900) was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era, as well as an art patron, draughtsman, water colourist, a prominent social thinker and philanthropist. He wrote on subjects as varied as geology, architecture, myth, ornithology, literature, education, botany and political economy.

His writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. He penned essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale. He also made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, and architectural structures and ornamentation. The elaborate style that characterised his earliest writing on art gave way in time to plainer language designed to communicate his ideas more effectively. In all of his writing, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society.

He was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism, sustainability and craft.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Lewis Carroll

c. 1857

Albumen print

5 1/2 x 4 5/8 in. (140 x 117mm)

Purchased with help from Kodak Ltd, 1973

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll took this photograph of himself with the assistance of Ina Liddell, Alice’s older sister. His diary records: ‘Bought some Collodion at Telfer’s […] and spent the morning at the Deanery … Harry was away, but the two dear little girls, Ina and Alice, were with me all the morning. To try the lens, I took a picture of myself, for which Ina took off the cap, and of course considered it all her doing!’

Wall text

Lewis Carroll (English, 1832-1898)

Alice Liddell

25 June 1870

Albumen carte-de-visite

3 1/2 x 2 1/4 in. (91 x 58mm)

Purchased jointly with the National Science and Media Museum, Bradford, with help from the Art Fund and the National Heritage Memorial Fund, 2002

© National Portrait Gallery, London

This is the only portrait of Alice that Carroll is known to have made after the publication of Alice in Wonderland, some seven years earlier. Showing Alice at age eighteen, the innocence of her earlier portraits has now completely drained away, replaced by a severe, inscrutable expression. The moment captured is unusually intimate, with Alice’s head lowered slightly and cocked to one side, looking up at the viewer, and her body slumped in a padded armchair. It is unclear whether Carroll orchestrated this pose, or whether Alice assumed it naturally.

Wall text

The National Portrait Gallery is to stage an exhibition of photographs by four of the most celebrated figures in art photography, including previously unseen works and a notorious photomontage, it was announced today, Tuesday 22 August 2017.

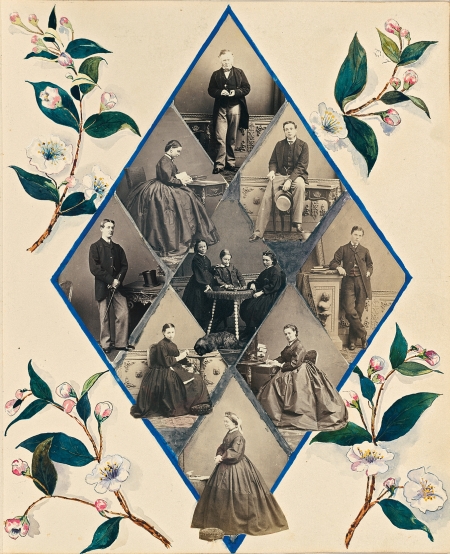

Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography (1 March – 20 May 2018), will combine for the first time ever portraits by Lewis Carroll (1832-1898), Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879), Oscar Rejlander (1813-1875) and Lady Clementina Hawarden (1822-1865). The exhibition will be the first to examine the relationship between the four ground-breaking artists. Drawn from public and private collections internationally, it will feature some of the most breath-taking images in photographic history, including many which have not been seen in Britain since they were made.

Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography will be the first exhibition in London to feature the work of Swedish born ‘Father of Photoshop’ Oscar Rejlander since the artist’s death. it will include the finest surviving print of his famous picture Two Ways of Life of 1856-1857, which used his pioneering technique combining several different negatives to create a single final image. Constructed from over 30 separate negatives, Two Ways of Life was so large it had to be printed on two sheets of paper joined together. Seldom-seen original negatives by Lewis Carroll and Rejlander will both be shown, allowing visitors to see ‘behind the scenes’ as they made their pictures.

An album of photographs by Rejlander purchased by the National Portrait Gallery following an export bar in 2015 will also go on display together with other treasures from the Gallery’s world-famous holdings of Rejlander, Cameron and Carroll, which for conservation reasons are rarely on view. The exhibition will also include works by cult hero Clementina Hawarden, a closely associated photographer. This will be the first major showing of her work since the exhibition Lady Hawarden at the V&A in London and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in 1990.

Lewis Carroll’s photographs of Alice Liddell, his muse for Alice in Wonderland, are among the most beloved photographs of the National Portrait Gallery’s Collection. Less well known are the photographs made of Alice years later, showing her a fully grown woman. The exhibition will bring together these works for the first time, as well as Alice Liddell as Beggar Maid on loan from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Visitors will be able to see how each photographer approached the same subject, as when Cameron and Rejlander both photographed the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson and the scientist Charles Darwin, or when Carroll and Cameron both photographed the actress, Ellen Terry. The exhibition will also include the legendary studies of human emotion Rejlander made for Darwin, on loan from the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University.

Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography celebrates four key nineteenth-century figures, exploring their experimental approach to picture-making. Their radical attitudes towards photography have informed artistic practice ever since.

The four created an unlikely alliance. Rejlander was a Swedish émigré with a mysterious past; Cameron was a middle-aged expatriate from colonial Ceylon (now Sri Lanka); Carroll was an Oxford academic and writer of fantasy literature; and Hawarden was landed gentry, the child of a Scottish naval hero and a Spanish beauty, 26 years younger. Yet, Carroll, Cameron and Hawarden all studied under Rejlander briefly, and maintained lasting associations, exchanging ideas about portraiture and narrative. Influenced by historical painting and frequently associated with the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, they formed a bridge between the art of the past and the art of the future, standing as true giants in Victorian photography.

Lenders to the exhibition include The Royal Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; Munich Stadtsmuseum; Tate and V & A. Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography will include portraits of sitters such as Charles Darwin, Alice Liddell, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Thomas Carlyle, George Frederick Watts, Ellen Terry and Alfred, Lord Tennyson.

Dr Nicholas Cullinan, Director, National Portrait Gallery, London, says: ‘The National Portrait Gallery has one of the finest holdings of Victorian photographs in the world. As well as some of the Gallery’s rarely seen treasures, such as the original negative of Lewis Carroll’s portrait of Alice Liddell and images of Alice and her siblings being displayed for the first time, this exhibition will be a rare opportunity to see the works of all four of these highly innovative and influential artists.’

Phillip Prodger, Head of Photographs, National Portrait Gallery, London, and Curator of Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography, says: ‘When people think of Victorian photography, they sometimes think of stiff, fusty portraits of women in crinoline dresses, and men in bowler hats. Victorian Giants is anything but. Here visitors can see the birth of an idea – raw, edgy, experimental – the Victorian avant-garde, not just in photography, but in art writ large. The works of Cameron, Carroll, Hawarden and Rejlander forever changed thinking about photography and its expressive power. These are pictures that inspire and delight. And this is a show that lays bare the unrivalled creative energy, and optimism, that came with the birth of new ways of seeing.’

Press release from the National Portrait Gallery

Figure 25 and 26 from the catalogue for the exhibition Victorian Giants: The Birth of Art Photography at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

In 1863, when Cameron was 48 years old, her daughter gave her a camera as a present, thereby starting her career as a photographer. Within a year, Cameron became a member of the Photographic Societies of London (1864) and Scotland. She remained a member of the Photographic Society, London, until her death. In her photography, Cameron strove to capture beauty. She wrote, “I longed to arrest all the beauty that came before me and at length the longing has been satisfied.” In 1869 she collated and gave what is now known as The Norman Album to her daughter and son-in-law in gratitude for having introduced her to photography. The album was later deemed by the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art to be of “outstanding aesthetic importance and significance to the study of the history of photography and, in particular, the work of Julia Margaret Cameron – one of the most significant photographers of the 19th century.”

The basic techniques of soft-focus “fancy portraits”, which she later developed, were taught to her by David Wilkie Wynfield. She later wrote that “to my feeling about his beautiful photography I owed all my attempts and indeed consequently all my success”.

Lord Tennyson, her neighbour on the Isle of Wight, often brought friends to see the photographer and her works. At the time, photography was a labour-intensive art that also was highly dependent upon crucial timing. Sometimes Cameron was obsessive about her new occupation, with subjects sitting for countless exposures as she laboriously coated, exposed, and processed each wet plate. The results were unconventional in their intimacy and their use of created blur both through long exposures and leaving the lens intentionally out of focus. This led some of her contemporaries to complain and even ridicule the work, but her friends and family were supportive, and she was one of the most prolific and advanced amateurs of her time. Her enthusiasm for her craft meant that her children and others sometimes tired of her endless photographing, but it also left us with some of the best of records of her children and of the many notable figures of the time who visited her.

During her career, Cameron registered each of her photographs with the copyright office and kept detailed records. Her shrewd business sense is one reason that so many of her works survive today. Another reason that many of Cameron’s portraits are significant is because they are often the only existing photograph of historical figures, becoming an invaluable resource. Many paintings and drawings exist, but, at the time, photography was still a new and challenging medium for someone outside a typical portrait studio.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Mary Fisher (Mrs Herbert Fisher)

1866-1867

Albumen print

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Julia Jackson

1864

Albumen print

Born in Calcutta, Julia Prinsep Jackson (1846-1895) was the youngest of three daughters of Maria Pattle and the physician John Jackson. Greatly admired by the leading artists of the day, both Edward Burne-Jones and G.F. Watts painted her and she was extensively photographed by her aunt and godmother Julia Margaret Cameron. Julia Jackson’s first husband, Herbert Duckworth, died in 1870 after only three years of marriage. She later married Leslie Stephen, editor of The Dictionary of National Biography. Together they had four children, including the painter Vanessa Bell and the writer Virginia Woolf.

Wall text

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty

1866

Albumen print

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Positioned high in the frame against a dark neutral backdrop, with piercing eyes and determined expression, the Mountain Nymph reveals the psychological charge of Cameron’s best portraits. The title derives from John Milton’s poem L’Allegro (published 1645): ‘Come, and trip it as ye go / On the light fantastick toe, / And in thy right hand lead with thee, / The Mountain Nymph, sweet Liberty’. Little is known about the sitter, Mrs Keene. She may have been a professional model as she also sat for the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones.

Wall text

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Virginia Dalrymple

1868-1870

Gernsheim Collection, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Marie Stillman (née Spartali)

1868

Albumen cabinet card

5 1/4 x 3 7/8 in. (133 x 99mm)

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Marie Euphrosyne Spartali (Greek: Μαρία Ευφροσύνη Σπαρτάλη), later Stillman (10 March 1844 – 6 March 1927), was a British Pre-Raphaelite painter of Greek descent, arguably the greatest female artist of that movement. During a sixty-year career, she produced over one hundred and fifty works, contributing regularly to exhibitions in Great Britain and the United States.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

‘La Madonna Aspettante’ (William Frederick Gould; Mary Ann Hillier)

1865

Albumen carte-de-visite on gold-edged mount

2 3/4 x 2 1/4 in. (70 x 56mm)

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

‘The Kiss of Peace’ (Elizabeth (‘Topsy’) Keown; Mary Ann Hillier)

1869

Albumen print on gold-edged cabinet

5 1/8 x 3 7/8 in. (131 x 99mm) image size

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Daisy Taylor

1872

Albumen print

14 3/8 x 9 3/4 in. (364 x 247 mm) image size

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

‘Alethea’ (Alice Liddell)

1872

Albumen print

12 3/4 x 9 3/8 in. (324 x 237mm) oval

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Lewis Carroll’s photographs of Alice Liddell are well-known; less familiar are the portraits Julia Margaret Cameron made of her years later, several of which respond directly to Carroll’s pictures. In this photograph, the twenty-year-old Alice is posed in full profile, much as Carroll depicted her in his famous seated portrait of 1858, shown nearby. However, Cameron shows Alice’s long wavy hair cascading in front of and behind her, merging with a background of blooming hydrangeas, the flowering of the plant echoing her coming of age. Cameron named the portrait after the Greek Aletheia, meaning ‘true’ or ‘faithful’.

Wall text

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Ellen Terry at Age Sixteen

1864

Albumen print

With a stage career that began at the age of nine and spanned sixty-nine years, Ellen Alice Terry (1847-1928) is regarded as one of the greatest actresses of her time. She was particularly celebrated for her naturalistic portrayals. Already an established professional, she married the artist G.F. Watts, thirty years her senior, a week before her seventeenth birthday, the year this photograph was made. Although they separated after less than a year, Watts painted Ellen on several occasions. One such portrait is currently on view in Room 26, on the Gallery’s first floor. Cameron’s idea to use a photograph of a particular subject at a specific time to embody a broad, abstract concept was particularly bold. Many believed that photography was better suited to recording minute detail than communicating universal themes.

Wall text

Dame Alice Ellen Terry, GBE (27 February 1847 – 21 July 1928), known professionally as Ellen Terry, was an English actress who became the leading Shakespearean actress in Britain. Born into a family of actors, Terry began performing as a child, acting in Shakespeare plays in London, and toured throughout the British provinces in her teens. At 16 she married the 46-year-old artist George Frederic Watts, but they separated within a year. She soon returned to the stage but began a relationship with the architect Edward William Godwin and retired from the stage for six years. She resumed acting in 1874 and was immediately acclaimed for her portrayal of roles in Shakespeare and other classics.

In 1878 she joined Henry Irving’s company as his leading lady, and for more than the next two decades she was considered the leading Shakespearean and comic actress in Britain. Two of her most famous roles were Portia in The Merchant of Venice and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing. She and Irving also toured with great success in America and Britain.

In 1903 Terry took over management of London’s Imperial Theatre, focusing on the plays of George Bernard Shaw and Henrik Ibsen. The venture was a financial failure, and Terry turned to touring and lecturing. She continued to find success on stage until 1920, while also appearing in films from 1916 to 1922. Her career lasted nearly seven decades.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson, formerly Mrs Duckworth)

1867

Albumen print, oval

13 1/2 x 10 3/8 in. (344 x 263mm)

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Prinsep Stephen, née Jackson (7 February 1846 – 5 May 1895) was a celebrated English beauty, philanthropist and Pre-Raphaelite model. She was the wife of the agnostic biographer Leslie Stephen and mother of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell, members of the Bloomsbury Group.

Born in India, the family returned to England when Julia Stephen was two years old. She became the favourite model of her aunt, the celebrated photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron, who made over 50 portraits of her. Through another maternal aunt, she became a frequent visitor at Little Holland House, then home to an important literary and artistic circle, and came to the attention of a number of Pre-Raphaelite painters who portrayed her in their work. Married to Herbert Duckworth, a barrister, in 1867 she was soon widowed with three infant children. Devastated, she turned to nursing, philanthropy and agnosticism, and found herself attracted to the writing and life of Leslie Stephen, with whom she shared a mutual friend in Anny Thackeray, his sister-in-law.

After Leslie Stephen’s wife died in 1875 he became close friends with Julia and they married in 1878. Julia and Leslie Stephen had four further children, living at 22 Hyde Park Gate, South Kensington, together with his seven year old handicapped daughter. Many of her seven children and their descendants became notable. In addition to her family duties and modelling, she wrote a book based on her nursing experiences, Notes from Sick Rooms, in 1883. She also wrote children’s stories for her family, eventually published posthumously as Stories for Children and became involved in social justice advocacy. Julia Stephens had firm views on the role of women, namely that their work was of equal value to that of men, but in different spheres, and she opposed the suffrage movement for votes for women. The Stephens entertained many visitors at their London home and their summer residence at St Ives, Cornwall. Eventually the demands on her both at home and outside the home started to take their toll. Julia Stephen died at her home following an episode of influenza in 1895, at the age of 49, when her youngest child was only 11. The writer, Virginia Woolf, provides a number of insights into the domestic life of the Stephens in both her autobiographical and fictional work.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson, formerly Mrs Duckworth); Gerald Duckworth

August 1872

Albumen print

8 1/2 in. x 12 1/8 in. (216 x 309mm)

Given by Cordelia Curle (née Fisher), 1959

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Robert Browning

1865

Albumen print

© Wellcome Collection, London

Cameron had a genius for recognising the expressive potential of chance events in her work. In this incomparable portrait, she allowed the many speck marks that cover this picture, caused by dust or debris settling on the plate after sensitising, to remain as part of the image. As a result, the poet Browning (1812-1889) becomes a transcendent figure, seemingly emerging from a field of stars. Browning developed an early interest in literature and the arts, encouraged by his father who was a clerk for the Bank of England. He refused to pursue a formal career and from 1833, he dedicated himself to writing poems and plays. In 1846 he married the poet Elizabeth Barrett. The couple lived in Italy until Elizabeth’s death in 1861, five years before this picture was taken.

Wall text

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of the dramatic monologue made him one of the foremost Victorian poets. His poems are known for their irony, characterisation, dark humour, social commentary, historical settings, and challenging vocabulary and syntax.

Browning’s early career began promisingly, but was not a success. The long poem Pauline brought him to the attention of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and was followed by Paracelsus, which was praised by William Wordsworth and Charles Dickens, but in 1840 the difficult Sordello, which was seen as wilfully obscure, brought his poetry into disrepute. His reputation took more than a decade to recover, during which time he moved away from the Shelleyan forms of his early period and developed a more personal style.

In 1846 Browning married the older poet Elizabeth Barrett, who at the time was considerably better known than himself, thus starting one of the most famous literary marriages. They went to live in Italy, a country he called “my university”, and which features frequently in his work. By the time of her death in 1861, he had published the crucial collection Men and Women. The collection Dramatis Personae and the book-length epic poem The Ring and the Book followed, and made him a leading British poet. He continued to write prolifically, but his reputation today rests largely on the poetry he wrote in this middle period.

When Browning died in 1889, he was regarded as a sage and philosopher-poet who through his writing had made contributions to Victorian social and political discourse – as in the poem Caliban upon Setebos, which some critics have seen as a comment on the theory of evolution, which had recently been put forward by Darwin and others. Unusually for a poet, societies for the study of his work were founded while he was still alive. Such Browning Societies remained common in Britain and the United States until the early 20th century.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Thomas Carlyle

1865

Albumen print

Lent by Her Majesty The Queen

Cameron portrayed the eminent historian and essayist Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) completely out of focus – a disembodied, ethereal being, with light playing across his head, face, and beard.

Born in Scotland, Carlyle is considered one of the most important social commentators of his time. His ideas about the role of ‘great men’ in shaping history informed his lecture series and book On Heroes, Hero-Worship and The Heroic in History (1841). Instrumental in the founding of the National Portrait Gallery, he became one of its first Trustees. Carlyle was lifelong friends with Henry Taylor (shown in the next room), to whom Cameron was also close.

Wall text

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Bt

1867

Albumen print

13 3/8 x 10 3/8 in. (340 x 264mm)

Purchased, 1982

© Wilson Centre for Photography

Cameron portrayed astronomer and physicist John Frederick William Herschel (1792-1871) as a romantic hero, his wild white hair and shining eyes emerging from darkness. Cameron and Herschel were lifelong friends. They had met in South Africa in 1836, where he was mapping the sky of the southern hemisphere, and where she was recovering from illness. A pioneer in the invention of photography, Herschel was responsible for numerous advancements and is credited with coining the terms ‘negative’, ‘positive’, and ‘photograph’. He introduced Cameron to photography in 1839 and shared the results of his early experiments with her. Rejlander also photographed Herschel, several years previously.

Wall text

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet KH FRS (7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath, mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, and experimental photographer, who also did valuable botanical work. He was the son of Mary Baldwin and astronomer William Herschel, nephew of astronomer Caroline Herschel and the father of twelve children.

Herschel originated the use of the Julian day system in astronomy. He named seven moons of Saturn and four moons of Uranus. He made many contributions to the science of photography, and investigated colour blindness and the chemical power of ultraviolet rays; his Preliminary Discourse (1831), which advocated an inductive approach to scientific experiment and theory building, was an important contribution to the philosophy of science.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

3 June 1869

Albumen print

11 3/8 x 9 3/4 in. (289 x 248mm)

Purchased, 1974

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Here, Cameron shows the poet emerging out of inky darkness, crowned by wild locks of hair on either side of his head, sporting an abundant beard, and framed by two points of his lapel. She positioned him on high, god-like and looking down, the viewer’s eye fixed at the height of his top button.

Wall text

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Charles Darwin

1868-1869

Albumen print

13 x 10 1/8 in. (330 x 256mm)

Purchased, 1974

© National Portrait Gallery, London

In the summer of 1868, Darwin and his family rented a holiday cottage on the Isle of Wight from Cameron’s family. The visit gave Cameron the opportunity to make this famous photograph. Publically, Darwin wrote of this portrait: ‘I like this photograph very much better than any other which has been taken of me.’ Privately, he was less positive, describing it as ‘heavy and unclear’. This particular print once belonged to Virginia Woolf, who was Julia Margaret Cameron’s great niece.

Wall text

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin’s Place

London, WC2H 0HE

Opening hours:

Open daily: 10.30 – 18.00

Friday and Saturday: 10.30 – 21.00

National Portrait Gallery website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Julia Margaret Cameron (English, 1815-1879) '[Kate Keown]' 1866 Julia Margaret Cameron (English, 1815-1879) '[Kate Keown]' 1866](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/12/4-_kate-keown-web.jpg?w=840&h=847)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[Merlin's photographic cart ?] and Mitchell's London Hotel, Railway Place, Sandridge [Port Melbourne]' 1870-1875 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[Merlin's photographic cart ?] and Mitchell's London Hotel, Railway Place, Sandridge [Port Melbourne]' 1870-1875](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-merlins-photographic-cart-and-mitchells-london-hotel-railway-place-sandridge-port-melbourne-1870-1875-web.jpg?w=840&h=543)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. 'A domestic miner [Hill End]' 1872 American & Australasian Photographic Company. 'A domestic miner [Hill End]' 1872](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-couple-and-child-in-the-front-formal-garden-of-their-slab-hut-cottage-hill-end-1870-1875-web.jpg?w=655&h=502)

![Gibbs, Shallard & Co., Colour Printers [188-?] 'Holtermann's Life Preserving Drops' 1872 Gibbs, Shallard & Co., Colour Printers [188-?] 'Holtermann's Life Preserving Drops' 1872](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/holtermans-life-preserving-drops-1872-web.jpg?w=814&h=1024)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante', Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873]' Aug 1873 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante', Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873]' Aug 1873](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-french-warship-atalante-fitzroy-dock-sydney-1873-1873-web.jpg?w=840&h=710)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante' at Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873 / attributed to the American & Australasian Photographic Company]' 1873 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante' at Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873 / attributed to the American & Australasian Photographic Company]' 1873](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/french-warship-atalante-at-fitzroy-dock-web.jpg?w=840&h=696)

![Charles Bayliss [American & Australasian Photographic Company]. 'Pall Mall, Bendigo' 1874 Charles Bayliss [American & Australasian Photographic Company]. 'Pall Mall, Bendigo' 1874](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/charles-bayliss-pall-mall-bendigo-1874-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

![Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd Anonymous photographer. 'Untitled [Borough of Clunes Notice Strike ..rm Rate]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/anon-borough-of-clunes-notice-strike-rm-rate-front-no-back3.jpg?w=655&h=441)

![National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd National Photo Company. 'Untitled [Group of bricklayers holding their tools and a baby]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/national-photo-company-nd-front1.jpg?w=655&h=421)

![E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd E. B. Pike. 'Untitled [Older man with moustache and parted beard]' Nd](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/e-b-pike-back2.jpg?w=458&h=656)

![Otto von Hartitzsch. 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883 Otto von Hartitzsch. 'Untitled [Man with quaffed hair and very thin tie]' 1867-1883](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/otto-von-hartitzsch-adelaide-1867-back2.jpg?w=463&h=662)

![Profesor Hawkins. 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875 Profesor Hawkins. 'Untitled [Chinese women with handkerchief]' c. 1858-1875](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/professor-hawkins-melbourne-front3.jpg?w=444&h=589)

![J. R. Tanner. 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875 J. R. Tanner. 'Untitled [Two woman wearing elaborate hats]' 1875](https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/j-r-tanner-1875-front1.jpg?w=408&h=617)

You must be logged in to post a comment.