January 2022

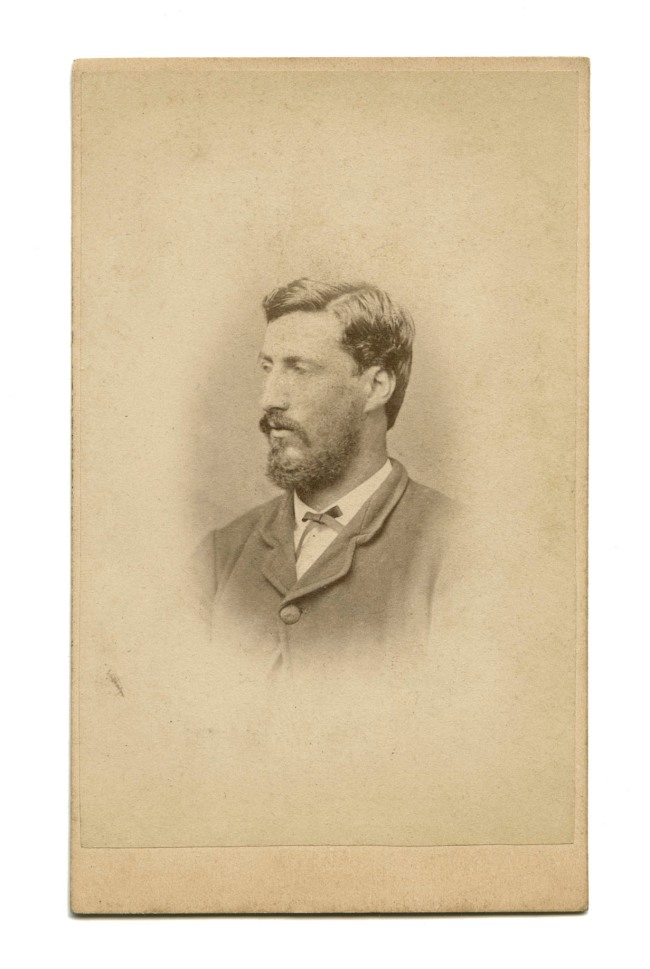

A. Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (recto)

c. 1864-1875

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

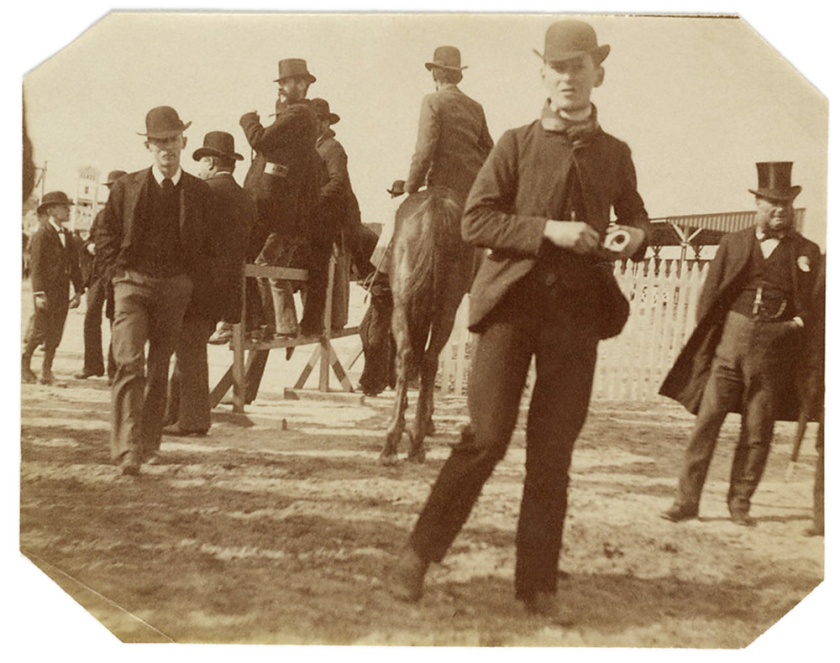

My friend Terence lent me his family photo album. It contains a lot of wonderful cartes-de-visite from photography salons in central Melbourne and country Victoria all in remarkably good condition. There are some unusual cards: family groups, twins in identical chequered outfits, a Latino woman, casual portraits with the sitter relaxing with their knees crossed and even an outdoor photograph of a dirty young vagabond with a chair. There is also a rare card, not strictly a cartes-de-visite, that lists when Omnibuses leave Hoddle Street (late Punt Road) and Toorak Road for St. Kilda via Chapel, Wellington, and Fitzroy Streets.

Several cartes-de-visite seem to have been taken at the same session but with different props: witness the Benson & Stevenson cards Untitled (Standing boy), Untitled (Seated woman) and Untitled (Seated woman holding book) where the background remains basically the same but the tablecloth has been inverted – probably son, mother and grandmother. Another Benson & Stevenson pairing Untitled (Seated wife and husband) and Untitled (Family group) possibly show the grandparents and their extended family.

Two cards by the Paterson Brothers, Untitled (Standing man holding a hat) and Untitled (Standing man) show the same backdrop but with a different width, height and design of column attached to the end of the colonnaded fence… perhaps to accommodate for the different height of the subjects. Were these two photographs taken in the same photographic session? Did the men know each other, were they brothers, or business partners?

A most beautiful card is that by an unknown photographer of Mr and Mrs Ritchie (1868, below). Against a plain backdrop and standing on a patterned piece of linoleum, the couple stand frontally facing the camera, her body slightly titled to the right while his lanky frame in oversized coat and lanky trousers is positioned to the left of the frame. The most striking thing about the photograph is Mrs Ritchie’s voluminous striped dress which takes up two-thirds of the pictorial frame, encroaching on Mr Ritchie’s space and obscuring his left foot. Her petite hand is nestled in the crook of his arm while his hands seem massive in comparison. He stares resolutely at the camera while she stares wistfully off camera to her right, mimicking the positioning of her body. This, as the back of the card observes, is the “likeness” of Mrs Alex Ritchie and a memory of her. Alex. Alex. Alex. What was your life like? What happiness and sadness did you endure that we remember you now, revisiting your likeness, bringing you into our consciousness, our hearts and thus into our memory – loved as you were by God & highly esteemed by all that knew her.

The more I reflect on these early photographs, the more I consider the moment that these people had their photographs taken – in those days, those several seconds that they had to remain still for the exposure – and the performance that led up to the capturing of their image. The appointment (if they had one), the entry into the gallery, the greeting, the seating, the waiting for the room to be available, the preparation of the attire, the combing of the hair, the direction by the photographer, the posing of the figure(s) and the exposure of the plate.

Some people would have been annoyed at the process, irritated at how long it took and how long they had to keep still for. I suspect others were imbued of the magic and the theatre of the photographic gallery… and that those few seconds of stillness could become like a period of extended time, like a car crash, where time slows down.** A brief abeyance of the laws of physics becomes an extension of the time of the spirit. The “presence” of the man in A. Archibald McDonald’s cartes-de-visite (c. 1864-1875, above) is a case in point: the low depth of field; the casual placement of hands on thigh and back of chair; the high-buttoned coat, chequered shirt, and top pocket handkerchief; the magnificent beard and the coiffed hair; but above all that penetrating gaze, as though he is staring off into the space of immortality.

Everything in balance, in focus, in stillness.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

** What I am encouraging you to think about here is that the time freeze of the photograph, the snap of the shutter, can be defeated in the physicality of the image, and in the space of the exposure – by a distortion of the witness’s felt temporality.

I am using Paul Virilio’s observation:

“‘No’, Rodin replies. ‘It is art that tells the truth and photography that lies. For in reality time does not stand still, and the artist who manages to give the impression that a gesture is being executed over several seconds, their work is certainly much less conventional than the scientific image in which time is abruptly suspended …’ The sharing of duration (between art and witness) is automatically defeated by the innovation of photographic instantaneity, for if the instantaneous image pretends to scientific accuracy in its details, the snap-shot’s image freeze or rather image-time-freeze invariably distorts the witness’s felt temporality …”

Paul Virilio. The Vision Machine (trans. Julie Rose). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994, p. 2.

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

A. Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (verso)

c. 1864-1875

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873)

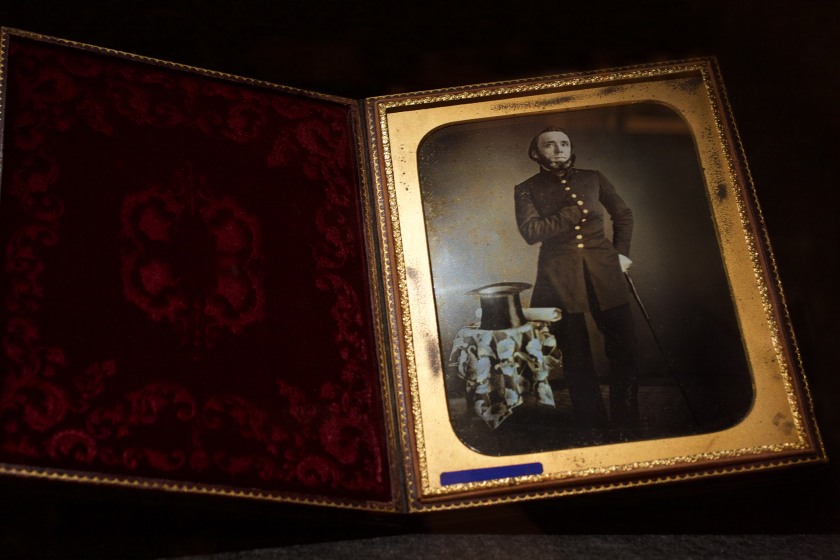

Archibald McDonald was a professional photographer, son of Hugh McDonald and Grace née McDougal, was born in Nova Scotia where his father was a planter. He came to Melbourne in about 1847 and was in partnership with Townsend Duryea by 1852. Their daguerreotype portraits and views in the 1854 Melbourne Exhibition were awarded a medal (which McDonald was still citing in advertisements in 1866). At the end of 1854 Duryea and McDonald were in Tasmania announcing that they would open a daguerreotype studio on 11 December at 46 Liverpool Street, Hobart Town. Still enough of a novelty to require promotion and explanation, their daguerreotypes were labelled ‘Curiosities as works of art – puzzles to the uninitiated – studies for the contemplative – pleasing reflections – historical records – pocket editions of the works of nature which “he who runs may read”‘. The partners had gone their separate ways by the following July when ‘Macdonald & Co., late Duryea & Macdonald’ began to advertise from Brisbane Street, Launceston. Archibald visited Launceston in July and again in November, in the interim making short tours to Deloraine (August), Longford (September) and Campbell Town (October).

Afterwards he continued the Melbourne firm of Duryea & McDonald possibly with Sanford Duryea , Townsend having relocated to Adelaide. By 1855 Thomas Adams Hill was the other half of the partnership at 3 Bourke Street, East Melbourne, but Hill soon left the studio to set up on his own. The young Charles Nettleton had joined the firm in 1854 and, according to Cato, then took over the outdoor work while McDonald concentrated on studio portraiture. The business flourished and by 1858 Duryea & McDonald had two Melbourne studios. McDonald set up a studio in his sole name in 1860 at 25 Bourke Street. In 1861 a case of his daguerreotype portraits in the Victorian Exhibition was awarded a first-class certificate and his photograph of the Albion Hotel received an honourable mention in the supplementary awards. Both his untouched and ‘Mezzotinto’ portrait photographs gained honourable mentions at the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition.

Having moved to St George’s Hall at 71 Bourke Street by 1864 McDonald was advertising extensive additions, including a new gallery, in 1866. His studio, he predictably claimed, was now ‘second to none in Europe or America and far surpassing anything in the Colonies’. The fire of March 1872 that destroyed the Theatre Royal, located directly behind his studio, also damaged his premises, but they were soon repaired and McDonald was at this address when he died the following year. His death was reported in the Illustrated Australian News on 4 December 1873…

Staff Writer. “Archibald McDonald,” on the Design & Art Australia Online website Jan 1, 1992 updated Oct 19, 2011 [Online] Cited 04/11/2021.

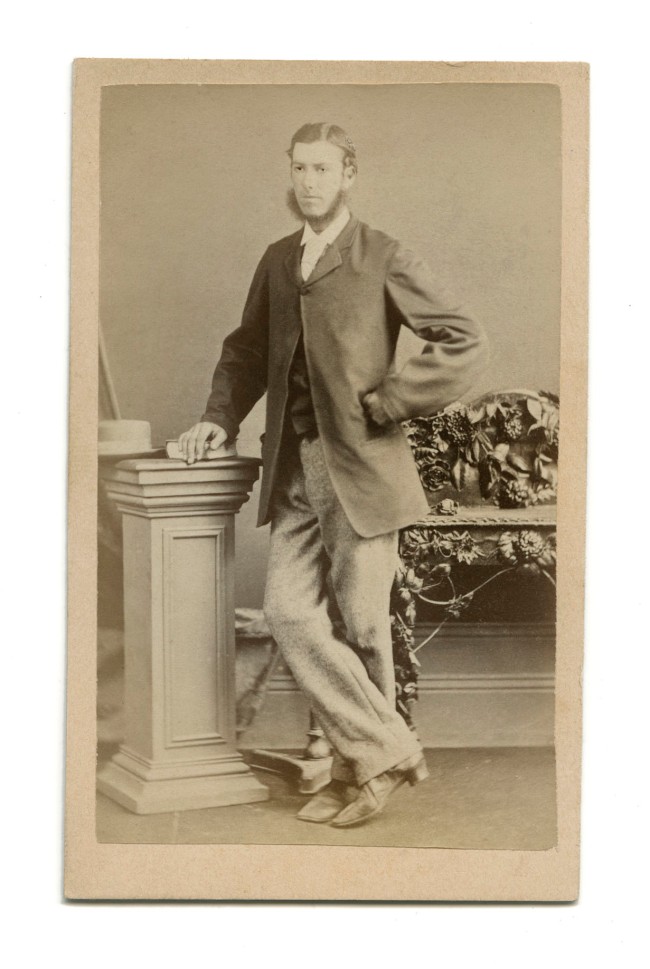

B. Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (recto)

c. 1864-1875

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

B. Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (verso)

c. 1864-1875

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of a child) (recto)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

This could be the sister of the twin boys below. Notice the same backdrop and the same table and cover to the right. In this image a chair has been used as a prop while in the image of the twins it has been removed.

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of a child) (verso)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

One of the pioneers of early photography in the 19th century along with his stepfather Thomas Bock, Alfred Bock also pursued a number of other interests including botany, painting and engraving. Mostly a resident of Tasmania, Bock also spent time in Victoria and New Zealand. …

With Thomas, Alfred had practiced photography commercially from its beginning in the daguerreotype form and he was concerned in every stage of development of the technique in Australia, undertaking innovative work in connection with the wet-plate process. Davies states that Bock introduced the carte-de-visite to Hobart Town in 1861, its first appearance anywhere in Tasmania. In 1864 he himself claimed to be the only person in the colony using the genuine sennotype process, a technique that gave a rich three-dimensional effect to portraits by overlaying a waxed albumen print on a normal photograph. The claim led to a lengthy controversy with Henry Frith, aired in the press from April to July. In the Mercury of 3 September 1864 Bock advertised that he had ‘succeeded, after a great number of experiments, in producing ALBUM PORTRAITS, by a modification of the SENNOTYPE PROCESS, retaining all the relief, delicacy, and lifelike beauty of the larger pictures’. He became most expert at the process and introduced a variation for cartes-de-visite in 1864. He continued to advertise sennotypes and ‘every description of Photograph from Locket to Life-size, executed in the most perfect manner’ until he left Hobart Town. His repertoire also included oil portraits painted over solar-enlarged photographs. His painted photographs of J. Boyd , civil commandant at Port Arthur, and ‘the late Captain Spring’ were commended in the Mercury of 14 July 1866. …

In 1867 Bock moved to Victoria and settled at Sale where he again conducted a photography business, producing not only the popular cartes-de-visite from his studio in Foster Street but also enlarging hand-coloured photographic portraits of Gippsland notables. At the 1880 Melbourne International Exhibition, Sale Borough Council was exhibiting two Alfred Bock watercolours, Redbank, River Avon, North Gippsland and On the Albert River, South Gippsland , possibly painted earlier. Bock himself showed his work at various exhibitions – the London International Exhibition (1873), the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition (1876), the Sandhurst (Bendigo) Industrial Exhibition (1879), the Adelaide International Exhibition (1887) and the Paris International Exhibition (1889) – and gained several awards.

In 1882 Bock advertised the sale ‘of the whole of his portrait and landscape negatives as well as those by the late Mr Jones and others, to Mr F. Cornell of Foster Street, Sale’ and went to Auckland, New Zealand. The family was back in Melbourne by 1887 where they remained until about 1906. Then Alfred retired from business and settled near Wynyard, Tasmania. He died there on 19 February 1920, survived by his second wife and a number of his children.

Plomley, N. J. B. and Kerr, Joan. “Alfred Bock,” on the Design & Art Australia Online website 1992 updated 2012 [Online] Cited 04/11/2021.

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of twins) (recto)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of twins) (verso)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (recto)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Alfred Bock (Australian, 1835-1920)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (verso)

c. 1867-1882

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Not dated, but photographers’ flourish dates for Elizabeth St. address: 1872-1880

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Standing boy)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Notice the same floral basket on the table as in the photograph of the seated woman below: same background, inverted covering to the table, perhaps mother and son.

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Seated woman)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Seated woman holding book)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Again, the same background, table covering and floral basket as the seated woman in the photograph above: this could be the grandmother.

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Notice the same painted background with the column as the image of the seated woman above, but with different props: one a covered table, the other a colonnade

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Mrs E. Thornton (recto)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Mrs E. Thornton (verso)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Seated man)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Seated wife and husband)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

This could be the grandparents of the family in the cartes-de-visite below.

Benson & Stevenson (Australian)

Untitled (Family group)

c. 1872-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

John Botterill (Australian born England, 1817-1881)

Untitled (Standing man) (recto)

1872-1874

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

John Botterill (Australian born England, 1817-1881)

Untitled (Standing man) (verso)

1872-1874

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

John Botterill (Australian born England, 1817-1881)

John Botterill, miniaturist, portrait painter and professional photographer, was born in Britain, son of John Botterill and Mary, née Barker. John junior was working in Melbourne from the early 1850s, advertising in the Argus of 12 April 1853 as a portrait, miniature and animal painter and offering lessons in landscape, fruit and flower painting in oil, watercolour, ‘crayon’ or pencil. …

Botterill appeared in Melbourne directories from 1862 to 1866 as an artist of Caroline Street, South Yarra. Between 1861 and 1865 he was also working at P.M. Batchelder ‘s Photographic Portrait Rooms in Collins Street East, Melbourne, ‘engaged … to paint miniatures and portraits in oil, watercolour or mezzotint – these deserve what they are receiving, a wide reputation’, stated the Argus on 22 November 1865. In 1866 he became one of the proprietors of Batchelder’s with F.A. Dunn and J.N. Wilson, but the partnership lasted only until the end of the following year. For the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh to Melbourne in November 1867 Botterill painted a 4 × 5 foot (121 × 152cm) transparency to decorate Batchelder’s. The Argus described this in detail, noting that it represented four of England’s chief naval heroes (Drake, Blake, Nelson and Collingwood) as well as Prince Alfred, an Elizabethan galleon and the Galatea , with the motto ‘England’s naval heroes and her hope’. Two coloured photographs by Botterill, Portrait of Sir J.H.T. Manners-Sutton and Portrait of Lady Manners-Sutton, were lent by the Governor Manners-Sutton to both the Melbourne Public Library and Ballarat Mechanics Institute exhibitions in 1869. From 1870 to 1879 Botterill operated his own Melbourne photographic studio: at 19 Collins Street East in 1872-74 and at 12 Beehive Chambers, Elizabeth Street in 1875-79. He died on 25 July 1881 and was buried in the St Kilda Cemetery.

Staff Writer. “John Botterill,” on the Design & Art Australia Online website Jan 1, 1992 updated October 19, 2011 [Online] Cited 04/11/2021.

Arthur William Burman (Australian, 1851-1915) (active 1869-1889, photographer)

Untitled (shirtless man with arms folded) (recto)

1878-1888

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Arthur William Burman (Australian, 1851-1915) (active 1869-1889, photographer)

Untitled (shirtless man with arms folded) (verso)

1878-1888

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Undated but photographer’s flourish dates for this address: 1878-1888

Arthur William Burman was one of the nine children of photographer William Insull Burman (1814-1890), who came to Victoria in 1853. Burman senior worked as a painter and decorator before establishing his own photography business in Carlton around 1863. Arthur and his older brother, Frederick, worked in the family business which, by 1869, operated a number of studios around Melbourne. Arthur is listed as operating businesses under his own name from addresses in East Melbourne, Carlton, Windsor, Fitzroy and Richmond between 1878 and his death in 1890.

F. C. Burman & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

Nd

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

F. C. Burman & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

Nd

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Standing man) (recto)

c. 1873 – c. 1890 at Foster Street, Sale, Gippsland, Vic.

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Standing man) (verso)

c. 1873 – c. 1890 at Foster Street, Sale, Gippsland, Vic.

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell arrived in Melbourne in 1854 from England aged 21. He was joined in Melbourne by his brothers, and they ran a number of shops there. By 1865 Cornell was taking and exhibiting photographs, and in 1867 relocated to Sale. He was then variously at Bairnsdale and Beechworth until he finally settled at Sale in 1875. He travelled throughout Gippsland at various times, and set up temporary studios. Frederick Cornell died at Sale in June 1890.

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

c. 1873 – c. 1890 Foster Street, Sale, Gippsland, Vic.

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

c. 1873 – c. 1890 Foster Street, Sale, Gippsland, Vic.

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (recto)

Nd

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Frederick Cornell (Australian born England, c. 1833-1890) (active 1865-1890)

Untitled (Portrait of a man) (verso)

Nd

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William Davies & Co (Australian born England) (active Australia, 1855-1882)

Untitled (Standing man) (recto)

c. 1862 – 1870

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William Davies & Co (Australian born England) (active Australia, 1855-1882)

Untitled (Standing man) (verso)

c. 1862 – 1870

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William Davies (Australian born England)

English photographer William Davies had arrived in Melbourne by 1855. He is said to have worked with his friend Walter Woodbury and for the local outpost of the New York firm Meade Brothers before establishing his own business in 1858. By the middle of 1862, ‘Davies & Co’ had rooms at 91 and 94 Bourke Street, from where patrons could procure ‘CARTE de VISITE and ALBUM PORTRAITS, in superior style’. Like several of his contemporaries and competitors, Davies appears to have made the most of his location ‘opposite the Theatre Royal’, subjects of Davies & Co cartes de visite including leading actors such as Barry Sullivan and Gustavus Vaughan Brooke, and comedian Harry Rickards. Examples of the firm’s work – portraits and views – were included in the 1861 Victorian Exhibition and the London International Exhibition of 1862; and at the 1866 Intercolonial Exhibition the firm exhibited ‘Portraits, Plain and Coloured, in Oils and Water Colours’ alongside a selection of views for which they received an honourable mention.

Sandie Barrie’s book Australians under the Camera refers the user to an entry for Davies, William & Co. who operated as a photographer between 1855 and 1882 and then in April 1893 as a travelling photographer.

William Davies was a professional photographer who established a number of studios in Melbourne between the 1858 and 1882. Davies was probably born in Manchester, UK and arrived in Melbourne around 1855. He began his photographic career in Australia in the employ of his friend, Walter Woodbury (inventor of the Woodburytype) and the Meade Brothers. Davies purchased the Meades’ business in 1858 and opened his own studio, William Davies and Co at 98 Bourke St, specialising in albumen photography of individuals and local premises. This address was opposite the Theatre Royal, and Davies took advantage of the proximity by selling cartes de visite of famous actors, actresses and opera singers. In 1861, Davies’s firm showed a number of portraits and images of Melbourne and Fitzroy buildings, often with the proprietors standing outside, at the Victorian Exhibition, and then at the 1862 London International Exhibition, where they received honourable mention. Along with actresses and buildings, the company also specialised in carte de visite portraits of Protestant clergymen posed in the act of writing their sermons. From 1862 to 1870 the firm was located at 94A Bourke St, where they shared the premises with the photographers Cox and Luckin.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 05/11/2021

St. George’s Hall Photographic Co.,

William Davies & Co (Australian born England) (active Australia, 1855-1882)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

c. 1862 – 1870

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

St. George’s Hall Photographic Co.,

William Davies & Co (Australian born England) (active Australia, 1855-1882)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

c. 1862 – 1870

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Ezra Goulter (Australian born England, 1825-1899)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

c. 1876 – c. 1893

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Ezra Goulter (1825-1899) was born in England and arrived in Australia with his new wife Sarah in 1860. He had previously visited Australia in 1849. Goulter was a professional photographer who worked in various studios around Melbourne. From 1863-1871 he worked in Emerald Hill (now South Melbourne), then he had a brief period at 57 Collins Street East from 1866-1867, and from 1876-1893 he was based on Chapel Street in Prahran. He focused on portraiture and produced cartes-de-visite in both black-and-white and hand-coloured formats. He exhibited his portraits at the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition where he received an honourable mention.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Art website

Ezra Goulter (Australian born England, 1825-1899)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

c. 1876 – c. 1893

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Vignette of a man) (recto)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Vignette of a man) (verso)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt was a professional photographer, was a foundation member of the Council of the Photographic Society of Victoria formed at Melbourne in 1860. Ran his own studios in various Melbourne locations until 1899 when he moved to Stawell, Victoria.

Not dated but a Hewitt worked at 95 Swanston Street, Melbourne between 1866-1880. Ref.: Australians behind the camera, directory of early Australian photographers, 1841-1945 / Sandy Barrie, 2002

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Oval of a man) (recto)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Oval of a man) (verso)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Oval of a woman) (recto)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Hewitt (Australian, 1837-1912) (active c. 1860 – c. 1899)

Untitled (Oval of a woman) (verso)

c. 1866-1880

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

E. E. Hibling (photographer active c. 1873 – c. 1877)

Johnstone O’Shannessy & Co (active 1865-1905)

Untitled (family group) (recto)

c. 1873 – c. 1877

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

E. E. Hibling (photographer active c. 1873 – c. 1877)

Johnstone O’Shannessy & Co (active 1865-1905)

Untitled (family group) (verso)

c. 1873 – c. 1877

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Not dated but a Hibling worked at 7 Collins Street East, Melbourne between between 1873-1877. Ref.: Australians behind the camera, directory of early Australian photographers, 1841-1945 / Sandy Barrie, 2002.

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co was founded in Melbourne in 1864 by Henry James Johnstone and a photographer known as ‘Miss O’Shaughnessy’, who had previously been in partnership with her mother in their own photographic business in Carlton. The firm exhibited photographs at the Intercolonial Exhibition in Melbourne in 1866, where the ‘special excellence’ of their work was noted by the judges. By the mid-1880s, when the firm moved from their Bourke Street address to purpose-built premises in the section of Collins Street known as ‘the Block’, Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co. were arguably Melbourne’s leading portrait photographers, their services sought by governors, visiting royalty, politicians and other prominent members of society. Examples of Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co.’s portraits were included in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1875 and the 1888 Melbourne International Exhibition. They expanded to Sydney during the 1880s, but the firm’s fortunes declined during the economic downturn of the following decade.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website updated 2018 [Online] Cited 08/11/2021

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co was a leading photographic studio located in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It was active from 1865 to 1905.

Henry James Johnstone was born in Birmingham, England, in 1835 and studied art under a number of private teachers and at the Birmingham School of Design before joining his father’s photographic firm. He arrived in Melbourne in 1853 aged 18 and became Melbourne’s leading portrait photographer during the 1870s and 1880s. In 1862 he bought out the Duryea and MacDonald Studio and started work as Johnstone and Co. In 1865 the firm became Johnstone, O’Shannessy and Co. with partner Emily O’Shannessy and co-owner George Hasler.

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co. were Melbourne’s leading portrait photographers whose services were sought by governors, visiting royalty, politicians and other prominent members of society. Johnstone impressed the Duke of Edinburgh during his visit to Victoria and was appointed to his staff as Royal Photographer. Examples of Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co.’s photographic portraits were included in the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1875 and the 1888 Melbourne International Exhibition where the excellence of their work was noted by the judges.

In 1876 Johnstone left Melbourne for South Australia and then travelled extensively in America, and then in 1880 to London, where he regularly exhibited paintings at the Royal Academy until 1900. He died in London in 1907 aged 72. The firm continued without him and expanded to Sydney during the 1880s and occupied a variety of buildings in Melbourne until the 1890s, but the firm’s fortunes declined during the economic downturn of the following decade. George Hasler, who created a printing process called Neogravure, ran the company till his death in 1897, after which his son-in-law, Rupert De Clare Wilks, took over the company from 1897 until 1905 when he put it into liquidation.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co (active 1865-1905)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

1865-1886

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Not dated but Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co. worked from 3 Bourke St. East, Melbourne, 1865-1886. Ref.: Australians behind the camera, directory of early Australian photographers, 1841-1945 / Sandy Barrie, 2002.

Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Co (active 1865-1905)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

1865-1886

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Nettleton (Australian born England, 1826-1902)

Untitled (Seated man) (recto)

c. 1867 – late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

This could be the same man as in the photograph by A. Archibald McDonald (Australian born Canada, c. 1831-1873) Untitled (Portrait of a man) at the top of the posting. Very similar hair, beard, eyes, countenance and gaze.

Charles Nettleton (Australian born England, 1826-1902)

Untitled (Seated man) (verso)

c. 1867 – late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

When this portrait was taken, Nettleton’s business address was No. 1, Madeline St. North Melbourne where he remained from 1863 until the late 1880s, although he had three other studios in Melbourne, including an office in the Victoria Arcade, Bourke St (Kerr 1992: 568). This photograph has to be after 1867

Charles Nettleton (Australian born England, 1826-1902)

Charles Nettleton (1826-1902), photographer, was born in north England, son of George Nettleton. He arrived in Victoria in 1854 accompanied by his wife Emma, née Miles. In Melbourne he joined the studio of T. Duryea and Alexander McDonald and specialised in outdoor work. He carried his dark tent and equipment with him everywhere, a necessity in the days of the collodion process when plates had to be developed immediately after exposure. He became special photographer for the government and the Melbourne Corporation and is credited with having photographed the first Australian steam train when the private Melbourne-Sandridge (Port Melbourne) line was opened on 12 September 1854.

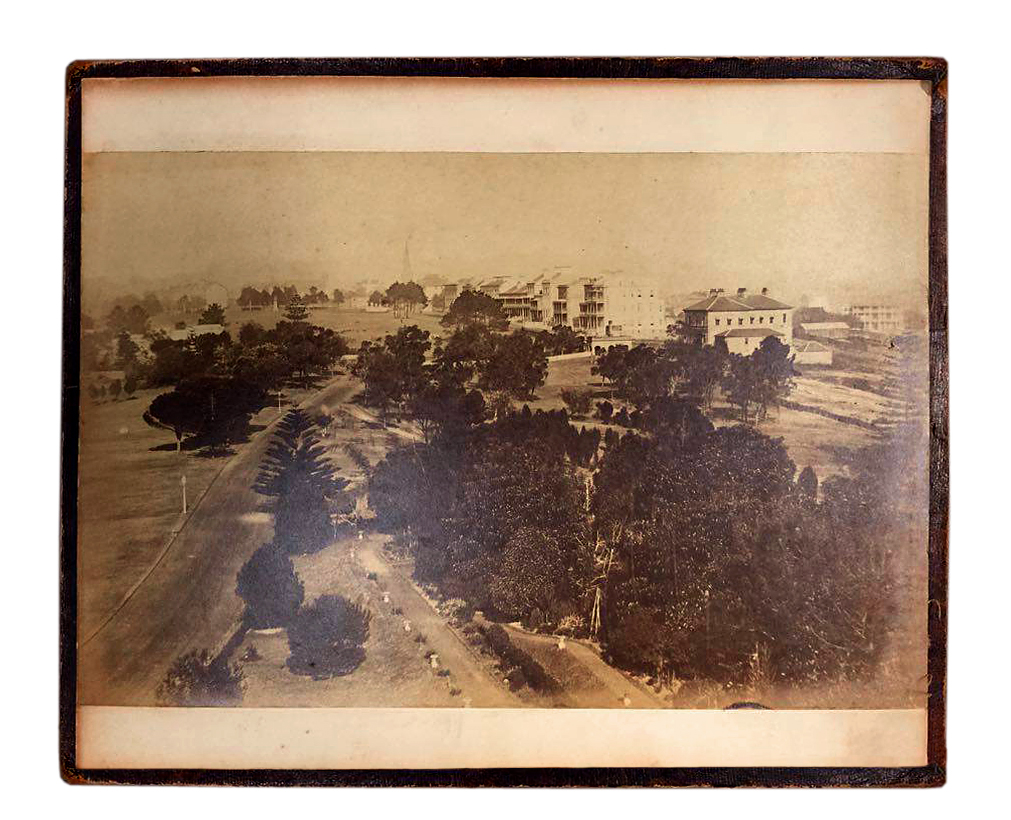

Nettleton systematically recorded Melbourne’s growth from a small town to a metropolis. Every major public work was photographed including the water and sewerage system, bridges and viaducts, roads, wharves, diversion of the River Yarra and construction of the Botanical Gardens. His public buildings include the Town Hall, Houses of Parliament, Treasury, Royal Mint, Law Courts and Post Office and he also photographed theatres, churches, schools, banks, hospitals and markets. His collection of ships includes photographs of the Cutty Sark, and the Shenandoah. He photographed the troops sent to the Maori war in 1860, the artillery camp at Sunbury in 1866 as well as contingents for the Sudan campaign and the Boxer rising. The sharp delineation of his pictures taken at six seconds exposure was a credit to his skill.

Nettleton visited the goldfields and country towns, photographed forests and fern glades, and rushed to disaster areas. In 1861 he boarded the Great Britain to take pictures of the first English cricket team to come to Australia. During the Victorian visit of the Duke of Edinburgh in 1867 he was appointed official photographer. He was police photographer for over twenty-five years and his portrait of Ned Kelly, of which one print is still extant, is claimed to be the only genuine photograph of the outlaw. Nettleton had opened his own studio in 1858. His souvenir albums were the first of the type to be offered to the public. However, when the dry-plate came into general use in 1885 he knew that the new process offered opportunities that were beyond his scope. Five years later his studio was closed. His work had won recognition abroad. His first success was at the London Exhibition of 1862 and in 1867 he was honoured in Paris. He was not a great artist but a master technician.

Nettleton was an active member of the Collingwood Lodge of Freemasons and a match-winning player of the West Melbourne Bowling Club. Aged 76 he died on 4 January 1902, survived by his wife, seven daughters and three sons.

Jean Gittins, “Nettleton, Charles (1826-1902),” on the Australian Dictionary of Biography website, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy (Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 5, Melbourne University Press, 1974), accessed online 9 November 2021.

Charles Nettleton (Australian born England, 1826-1902)

Untitled (Standing man) (recto)

c. 1867 – late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Charles Nettleton (Australian born England, 1826-1902)

Untitled (Standing man) (verso)

c. 1867 – late 1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (two brothers)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Notice what looks like a photo album of cartes-de-visite on the table at left probably open at a photographic of their mother and father

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Seated woman with clasped hands)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Seated woman)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Young vagabond standing outdoors)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Young vagabond standing outdoors) (detail)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Seated woman)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man holding hat)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man leaning on a pillar)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Mr and Mrs Ritchie) (recto)

1868

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Mr and Mrs Ritchie) (verso)

1868

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

“The likeness of Mrs Alex Ritchie.

In memory of Mrs Ritchie who died on Friday January 10th 1868. She was a child of God, loved by God & highly esteemed by all that knew her.

Her end was peace.

Sykes”

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man with blue sash)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Unknown photographer (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man in boots and spurs)

1860s-1880s

Albumen silver print with hand colouring

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Omnibuses timetable, Melbourne

February 1873 (recto and verso)

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing man holding a hat)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William Paterson was a professional photographer. He worked in Melbourne in partnership with his brother Archibald. At the 1866 Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition, both of them were awarded an honourable mention for their ‘Untouched and Coloured Portraits and Photographic Views’.

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing man holding a hat) (detail)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing man)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing man) (detail)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing boy) (recto)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Standing boy) (verso)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Vignette of a man) (recto)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Paterson Brothers (William and Archibald Paterson) (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1893)

Untitled (Vignette of a man) (verso)

c. 1866 – c. 1869 at 8 Bourke Street East, Melbourne, Vic

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Seated man) (recto)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Undated, flourish dates for photographer at Chapel Street, South Yarra: circa 1872.

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Seated man) (verso)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man) (recto)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing man) (verso)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

C. Rudd & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

c. 1872

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William H. Bardwell (Australian, 1836-1929)

Untitled (Seated man)

c. 1880-1888

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

William Bardwell was a professional photographer and regular exhibitor who spent most of his working life in Ballarat, Victoria. Bardwell’s studio operated between 1875-1891. Flourish dates for Bardwell at 21 Collins Street East, Melbourne: 1880-1888.

According to Davies & Stanbury (The Mechanical Eye In Australia: Photography 1841-1900. Oxford University Press, 1985), Bardwell was active at his 21 Collins Street address – his first Melbourne studio – only from 1880, but the Design & Art Australia Online website suggests he had already relocated to Melbourne by the end of 1878.

Solomon & Bardwell (Australian, active c. 1859-1866? 1874?)

Untitled (Mrs John Keys) (recto)

c. 1866

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Saul Solomon (Australian born England, 1836-1929)

Saul Solomon (1836-1929) had a studio in Main Road, Ballarat from 1857 to 1862, and worked in partnership with William Bardwell at 29 Sturt Street, Ballarat until 1874. Solomon and Bardwell also operated in Maryborough and Dunolly. From 1874 to 1891 Solomon operated under the name of the Adelaide School of Photography at 51 Rundle Street, Adelaide.

Saul Solomon was born on 15 January 1836 in Knightbridge, London. He was the son of well known dealer in photographic equipment, Joseph Solomon. He migrated to Victoria in 1852. He was in Ballarat in 1854 and in 1857 he set up a professional photography studio. In 1859 he was joined by William H. Bardwell (active, c.1858 – c.1889). He married Martha Patti at Balalrat on 13 October 1866. Two years later they moved to Adelaide.

William Bardwell (Australian, active c. 1858 – c. 1889)

Bardwell was a professional photographer and regular exhibitor who spent most of his working life in Ballarat, Vic.

He was a professional photographer, was employed in 1858 by Saul Solomon at Ballarat, Victoria providing photographs of the town which were lithographed by Francois Cogne (q.v.) for The Ballarat Album (1859). Solomon and Bardwell were soon partners; they worked in Main Street from 1859, in Sturt Street from 1865 and visited Maryborough and Dunolly (Victoria) in 1865. Together they exhibited photographic portraits at the 1862 Geelong Industrial Exhibition and the 1863 Ballarat Mechanics Institute Exhibition. Their ‘new sennotype process’ was judged ‘highly successful’ by the Illustrated Melbourne Post of 27 December 1862. On 9 February 1863, the Argus reported that Bardwell had photographed the ceremony of the laying of the foundation stone of the Burke and Wills memorial in Sturt Street from a vantage point on the roof of the Ballarat Post Office. By 28 September 1866 the partnership seems to have been dissolved for Bardwell was then advertising his Royal Photographic Studio in the Clunes Gazette: ‘The studio is every way replete with suitable accommodation for the preparation of toilet and rooms are provided for both ladies and gentlemen. Mr Bardwell’s long and practical example will entitle him to the claim to the first position in Ballarat as a photographer.’ He exhibited views and portraits, including Portrait of the Very Rev. Dean Hayes, at the 1869 Ballarat Institute Exhibition and showed photographs of Ballarat at the 1870 Sydney Intercolonial (for sale at £6). Other exhibited photographs included ‘a large panorama of the city of Ballarat, in a semi-circular form’, …

Text from the Trove website [Online] Cited 12/11/2021

William Bardwell was a professional photographer with a successful business in Ballarat and Melbourne. In Ballarat he formed a partnership with Saul Solomon in 1859 and together they exhibited photographic portraits at the 1862 Geelong Industrial Exhibition and the 1863 Ballarat Mechanics Institute Exhibition. It seems Bardwell was fond of using unusual vantage points: in 1863, the ‘Argus’ reported that he had photographed the ceremony of the laying of the foundation stone of the Burke and Wills memorial in Sturt Street from the roof of the Ballarat Post Office. ‘Bardwell established his own studio in 1866, which included rooms for ladies and gentlemen to prepare themselves for the lens’. He showed photographs of Ballarat at the 1870 Sydney Intercolonial exhibition (for sale at £6), and ‘a photographic panorama of the city of Ballarat’ as well as other photographs of its buildings and streets in the Victorian section of the London International Exhibition of 1873.

Text from the Art Gallery of New South Wales website [Online] Cited 12/11/2021

Solomon & Bardwell (Australian, active c. 1859-1866? 1874?)

Untitled (Mrs John Keys) (verso)

c. 1866

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

“In memory of Mrs John Keys who died in the year 1866. Her end was peace.”

Stewart & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Oval of a gentleman) (recto)

1881-1889

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Flourish dates for Stewart & Co. at 217-219 Bourke Street East, Melbourne: 1881-1889

“… the upmarket city studio of Stewart & Co. ‘photographers, miniature and portrait painters’, which was located in the theatre district of Bourke Street east. The owner, Englishman Robert Stewart (1838-1912), was a professional photographer who relocated from Sydney to Melbourne in 1871.”

Stewart & Co (Australian)

Untitled (Oval of a gentleman) (verso)

1881-1889

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Joseph Turner (Australian, active 1856-1880s)

Untitled (Standing woman) (recto)

c. 1866

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

Not dated but Turner’s New Portrait Rooms were at Moorabool St., Geelong, Victoria, between 1865-1867. Ref.: Australians behind the camera, directory of early Australian photographers, 1841-1945 / Sandy Barrie, 2002.

The dates for Moorabool St., differ from the entry on Design & Art Australia Online below.

Joseph Turner (Australian)

Joseph Turner was a professional photographer, worked at 24 Great Ryrie Street, Geelong, Victoria, in late 1856. Turner’s New Portrait Rooms were at 60 (later 66) Moorabool Street in 1857-1867, then at Latrobe Terrace until 1869. In June 1856 Turner lectured at the Geelong Mechanics Institute on ‘The Art of Photography’, promoting its superior accuracy to painting. Basing his talk on the quasi-scientific sermons of the Scottish divine Dr Thomas Dick, published as The Practical Astronomer (1855), Turner argued that the minuteness of light particles was a testament to ‘the wisdom and beneficence of the creator’.

The photographs Turner showed at the 1857 Geelong Mechanics Institute Exhibition may have been ambrotypes as his surviving ambrotype of three children (National Gallery of Australia) is thought to date from about 1860. At the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition in 1866 he showed albumen paper prints of architectural and landscape views in Geelong, including ‘large sized photographs of the Chamber of Commerce and the Savings Bank, as well as the United Presbyterian Church, the Mechanics Institute, the Telegraphic and Post offices, the London Chartered Bank, the Town Hall, a well arranged view of Malop Street, and the Private residences of the town’s leading citizens’. Aware of the importance of the photographic portrait to his business, he also exhibited four frames of plain and coloured cartes-de-visite, including portraits of women where ‘the pose and the drapery was wonderfully managed’. Cartes of the mayor, alderman, councillors and officials of Geelong were arranged against a crimson background in one frame. His several enlarged portraits included one of Mr Morrison of the Geelong College. He won a medal for his tinted portraits and another for his architectural and landscape views.

Reviewing the photographic views at the exhibition in the Australian Monthly Magazine, ‘Sol’ commended Turner’s method of printing and presentation. ‘Vignetting portraits has long been a favourable occupation’, he noted, ‘and we have sometimes seen it applied to landscapes, but never in this particular way, and we certainly admire the exquisite finish it gives to the picture’. The Geelong press, on the other hand, admired Turner’s ‘business enterprise’ in using these views and portraits for local publicity when he set up ‘a miniature exhibition’ in his New Portrait Rooms before sending the photographs to the Melbourne Intercolonial Exhibition, particularly as he advertised it at precisely the time that J. Norton and L. Ormerod’s commissioned views were on display in the Geelong Town Hall.

His ability to make the most of an opportunity again surfaced the following year, on the occasion of the visit of the Duke of Edinburgh to Geelong. A pair of plates he took, showing the reception for the royal visitor on the Yarra Street wharf with the mayor welcoming the Duke and the town clerk reading the corporation’s address to his Royal Highness, appeared as engravings in the Illustrated London News soon afterwards.

On 9 October 1869 a large fire in Geelong destroyed five buildings in Moorabool Street, including Turner’s premises, and he disappeared from Geelong. [Gael] Newton notes that Joseph Turner, described as ‘an excellent photographer’, was appointed to the Melbourne Observatory on 10 February 1873 and remained there until 1883. Lunar photographs by Turner are held at the Mount Stromlo and Siding Springs Observatory (Australian Capital Territory) and at the Australian National Gallery. Other photographs are in the La Trobe Library and at Melbourne University.

Paul Fox. “Joseph Turner,” on the Design & Art Australia Online website 1992 updated 2011 [Online] Cited 12/11/2021

Joseph Turner (Australian, active 1856- 1880s)

Untitled (Standing woman) (verso)

c. 1866

Albumen silver print

Cartes-de-visite

11 x 7cm

![George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865 George Roberts (Australian born United Kingdom, c. 1800-1865) '[Mrs Macquarie's chair]' c. 1843-1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mrs-macquaries-chair-web.jpg)

![Unknown photographer. '[A group of Aboriginal men at Coranderrk Station, Healesville]' Nd Unknown photographer. '[A group of Aboriginal men at Coranderrk Station, Healesville]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/sixteen-aboriginal-men.jpg)

![Talma & Co. (1893-1932) 119 Swanston St. Melbourne 'Barak, Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. [Barak drawing a corroboree]' c. 1895-1898 Talma & Co. (1893-1932) 119 Swanston St. Melbourne 'Barak, Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. [Barak drawing a corroboree]' c. 1895-1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/william-barak-a.jpg?w=650&h=1016)

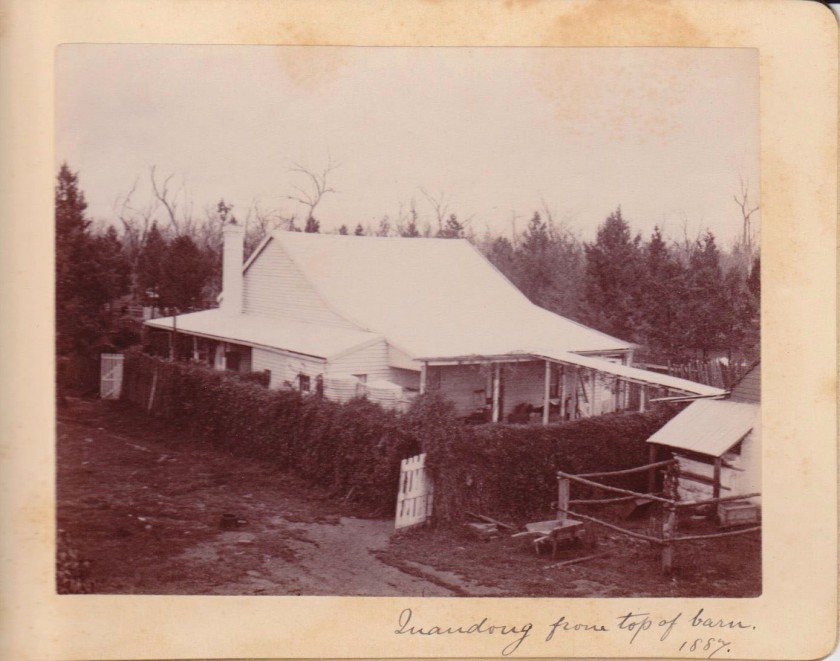

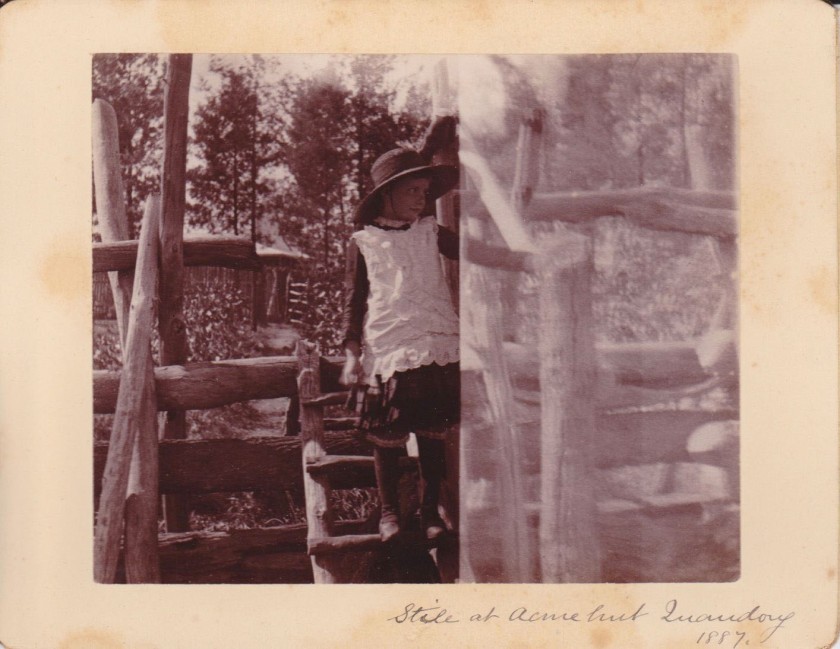

![Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Horse and trap], Quandong' 1887 Unknown photographer. 'Untitled [Horse and trap], Quandong' 1887](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/quandong11.jpg?w=840)

![Unknown photographer. 'At Quandong [Horse, foal and cart]' 1887 Unknown photographer. 'At Quandong [Horse, foal and cart]' 1887](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/quandong9.jpg?w=840)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[Merlin's photographic cart ?] and Mitchell's London Hotel, Railway Place, Sandridge [Port Melbourne]' 1870-1875 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[Merlin's photographic cart ?] and Mitchell's London Hotel, Railway Place, Sandridge [Port Melbourne]' 1870-1875](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-merlins-photographic-cart-and-mitchells-london-hotel-railway-place-sandridge-port-melbourne-1870-1875-web.jpg?w=840&h=543)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. 'A domestic miner [Hill End]' 1872 American & Australasian Photographic Company. 'A domestic miner [Hill End]' 1872](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-couple-and-child-in-the-front-formal-garden-of-their-slab-hut-cottage-hill-end-1870-1875-web.jpg?w=655&h=502)

![Gibbs, Shallard & Co., Colour Printers [188-?] 'Holtermann's Life Preserving Drops' 1872 Gibbs, Shallard & Co., Colour Printers [188-?] 'Holtermann's Life Preserving Drops' 1872](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/holtermans-life-preserving-drops-1872-web.jpg?w=814&h=1024)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante', Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873]' Aug 1873 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante', Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873]' Aug 1873](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/american-australasian-photographic-company-french-warship-atalante-fitzroy-dock-sydney-1873-1873-web.jpg?w=840&h=710)

![American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante' at Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873 / attributed to the American & Australasian Photographic Company]' 1873 American & Australasian Photographic Company. '[French warship 'Atalante' at Fitzroy Dock, Sydney, 1873 / attributed to the American & Australasian Photographic Company]' 1873](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/french-warship-atalante-at-fitzroy-dock-web.jpg?w=840&h=696)

![Charles Bayliss [American & Australasian Photographic Company]. 'Pall Mall, Bendigo' 1874 Charles Bayliss [American & Australasian Photographic Company]. 'Pall Mall, Bendigo' 1874](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/charles-bayliss-pall-mall-bendigo-1874-web.jpg?w=840&h=692)

You must be logged in to post a comment.