Exhibition dates: 21st March – 8th June 2015

Curator: Judy Annear, Senior curator of photographs, AGNSW

Judy Annear. The photograph and Australia. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2015. p. 236

“Cultural theorist Ross Gibson has written that ‘being Australian might actually mean being untethered or placeless … and appreciating how to live in dynamic patterns of time rather than native plots of space’. Photographs always enable imaginative time and space regardless of their size and how little we might know of the ostensible subject. When people are oriented toward the camera and photographer, there is a gap which the viewer intuitively recognises. The gap is time as much as space. Occasionally – as in an anonymous 1855 daguerreotype taken at Ledcourt, Victoria, of Isabella Carfrae on horseback where we see a servant standing on the verandah, shading her eyes, and in the 1877 Fred Kruger photograph of the white-clad cricketer at Coranderrk – a subject in the photograph presses so close to the picture plane that we know for the time of the exposure they look directly into an unknowable future and collide now with our gaze as we look back.”

Judy Annear. “Time,” in Judy Annear. ‘The photograph and Australia’. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2015. p. 19.

This is an important exhibition and book by Judy Annear and team at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, an investigation into the history of Australian photography that is worthy of the subject. Unfortunately, I could not get to Sydney to see the exhibition and I have only just received the catalogue. I have started reading it with gusto.

With regard to the exhibition all I have to go on is a friend of mine who went to see the exhibition, and whose opinion I value highly, who said that is was the messiest exhibition that she had seen in a long while, and that for a new generation of people approaching this subject matter for the first time it’s non-chronological nature would have been quite off putting.

But this is the nature of the beast (that being a thematic not chronological approach) and personally I believe that modern audiences are a lot more understanding of what was going on in the exhibition than she would give them credit for.

In the “Introduction” to the book, Annear rightly credits the work undertaken by colleagues – especially Gael Newton’s Shades of light: photography and Australia 1839-1988, published in 1988; Alan Davis’ The mechanical eye in Australia: photography 1841-1900, published in 1977; and Helen Ennis’ Photography and Australia, published in 2007.

As the latter did, this new book “emphasises the ways in which photographs, especially in the nineteenth century, function in social, cultural and political contexts, exploring photography’s role in representing relationships between Indigenous and settler cultures, the construction of Australia, and its critique.” (Annear, p. 10)

While Ennis’ book took a chronological approach, with sections titled First Photographs, Black to Blak, Land and Landscape, Being Modern, Made in Australia, Localism and Internationalism, The Presence of the Past – Annear’s book takes a more conceptual, thematic approach, one that crosses time and space, linking past and present work in classificatory sections titled Time, Nation, People, Place and Transmission.

Both books acknowledge the key issues that have to be dealt with when formulating a book on the photograph and Australia: “the medium itself, Australia’s history, and the relationship between them. Is Australian photography different? If so, how, and in relation to what? One has to look at places with not dissimilar histories, such as Canada and New Zealand. And other questions: what has preoccupied photographers working in relation to Australia at various points in time? Have their concerns been primarily commercial, aesthetic, historical, realist, interpretive, or theoretical? Have they developed projects unique to the photographic medium; for example, large-scale classificatory projects? What have they achieved, what did it mean then, and what does it mean now?” (Annear, p.10)

These questions are the nexus of Annear’s investigation and she seeks to answer them in the well researched chapters that follow, while being mindful of “preserving some of the slipperiness of the medium.” And there is the rub.

In order to define these classificatory sections in the exhibition and book, it would seem to me that Annear shoehorns these themes onto the fluid, mutable “state of being” of the photograph, imposing classifications to order the mass of photography into bite sized entities. While “the book encourages the reader to explore connections – between different forms of photography, people and place, past and present” it also, inevitably, imposes a reading on these historical photographs that would not have been present at the time of their production.

The press release for the book says, “The photograph and Australia investigates how photography was harnessed to create the idea of a nation.” Now I find the use of that word “harnessed” – as in control and make use of – to be hugely problematic.

Personally, I don’t think that the slipperiness and mutability of photography can ever be controlled by anyone to help create the idea (imagination?) of a nation. Nations build nations, not photography. As a friend of mine said to me, it’s a long bow to draw… and I would agree.

The crux of the matter is that THERE ARE NO HANDLES, only the ones that we impose, later, from a distance. There is no definitive answer to anything, there are always twists and turns, always another possibility of how we look at things, of the past in the present.

Photography and photographs, “with its ability to capture both things of the world and those of the imagination,” are always unstable (which is why the photograph can still induce A SENSE OF WONDER) – always uncertain in their interpretation, then and now. Photographs do not belong to a dimension or a classification of time and space because you feel their being NOT their (historical) consequence. Hence, all of these classifications are essentially the same/redundant.

Perhaps it’s only semantics, but I think the word “utilises” – make practical and effective use of – would be a better word in terms of Annear’s enquiries. It also occurred to me to turn the question around: instead of “how photography was harnessed to create the idea of a nation”; instead, “how the idea of a nation helped change photography.” Think about it.

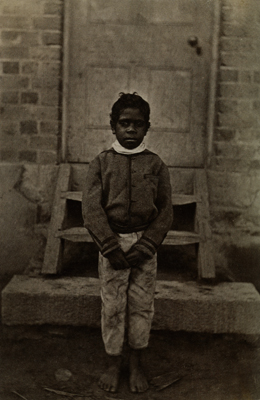

Finally, a comment on the book itself. Beautifully printed, of a good size and weight, the paper stock is of excellent quality and thickness. The type is simple and legible and the book is lavishly illustrated with photographs. The reproductions are a little ‘flat’ but the main point of concern is the size of the reproductions. Instead of reproducing carte de visite at 1:1 scale (that is, 64 mm × 100 mm), their mounted on card size – they are reproduced at 40 mm x 68 mm (see p. 236 of the catalogue below). Small enough already, this printing size renders the detailed reading of the images almost impossible. Worse, the images are laid out horizontally on a vertical page, with no size attribution of the original, nor whether they are 1/9th, 1/6th daguerreotype’s or ambrotypes, CDV’s or cabinet cards next to the image.

The reproduction size of the daguerreotypes and ambrotypes is even worse, making the images almost unreadable. For example, in an excellent piece of writing at the end of the first chapter, “Time”, Annear refers to “an anonymous 1855 daguerreotype taken at Ledcourt, Victoria, of Isabella Carfrae on horseback where we see a servant standing on the verandah, shading her eyes,”.

In the image in this posting (below) we can clearly see this woman standing on the verandah, but in the reproduction in the book (p. 139), she is reduced to a mere smudge in history, an invisibility caused by the size of the reproduction, thereby negating all that Annear comments upon.

Instead of the “subject in the photograph presses so close to the picture plane that we know for the time of the exposure they look directly into an unknowable future and collide now with our gaze as we look back,” there is no pressing, hers has no presence, and our gaze cannot collide with this vision from the future past. Why designers of photographic books consistently fall prey to these traps is beyond me.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thank to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for allowing me to publish the photographs and text in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Unknown photographer

Australian scenery, Middle Harbour, Port Jackson

c. 1865

Carte de visite

Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Sydney 2014

Unknown photographer

Australian scenery, Middle Harbour, Port Jackson (verso)

c. 1865

Carte de visite

Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Sydney 2014

The first large-scale exhibition of its kind to be held in Australia in 27 years, The photograph and Australia presents more than 400 photographs from more than 120 artists, including Richard Daintree, Charles Bayliss, Frank Hurley, Harold Cazneaux, Olive Cotton, Max Dupain, Sue Ford, Carol Jerrems, Tracey Moffatt, Robyn Stacey, Ricky Maynard and Patrick Pound.

The works of renowned artists are shown alongside those of unknown photographers and everyday material, such as domestic and presentation albums. These tell peoples’ stories, illustrate where and how they lived, as well as communicate official public narratives. Sourced from more than 35 major collections across Australia and New Zealand, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Library of Australia and the Australian Museum, The photograph and Australia uncovers hidden gems dating from 1845 until now.

A richly illustrated publication accompanies the exhibition, reflecting the exhibition themes and investigating how Australia itself has been shaped by photography.

Extract from “Introduction”

“The task of this book is to formulate questions around Australian photography and its history, regardless of Australia’s, and the medium’s, permeable identity. While early photography in Australia made histories of the colonies visible, and a great deal can be read from the surviving photographic archives, interpretation of this material is often conjecture, and much remains oblique. Patrick Pound describes the sheer mass of photographs and images in the world today as an “unhinged album.”11 This dynamic of making, accumulating, ordering, disseminating, reinterpreting, re-collecting and re-narrating is an important aspect of photography. The intimate relationship, historically, between the photograph and the various arts and sciences, along with the adaptability to technological change and imaginative interpretations, allows for a constant montaging or weaving together of uses and meanings. This works against the conventional linear structure of classical histories and the idea of any progressive evolution of the medium. If what we are dealing with is a phenomenon rather than simply a form then analysing the phenomenon and its dynamic relationship to art, society, peoples, sciences, genres, and processes is critical to our modern understanding of ourselves and our place in the world as well as of the medium itself.12

In the 1970s, cultural theorist Roland Barthes wrote an essay entitled The photographic message.13 While he focussed primarily on press photography and made a distinction between reportage and ‘artistic’ photography, his pinpointing of the special status of the photographic image as a message without a code – one could say, even, a face without a name – and his understanding of photography as a simultaneously objective and invested, natural and cultural, is relevant in the colonial and post-colonial context.

We search for clues in photographs of our past and present. In some ways this is a melancholy activity, in other ways valuable detective work. In many cases it is both. Photography since its inception has belonged in a nether world of being and not being, legibility and opacity. This book preserves some of the slipperiness of the medium, while providing a series of texts touching on the photographs at hand. The history of the photograph and its relationship to Australia remains tantalisingly partial; the ever-burgeoning archives await further excavation.”14

Judy Annear. “Introduction,” in Judy Annear. The photograph and Australia. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2015. p. 13.

11. See ‘Transmission’ pp. 227-33

12. See Geoffrey Batchen, A Subject For, A History About, Photography accessed 23 December 2021

13. Roland Barthes, ‘The photographic message’, Image, music, text, trans Stephen Heath, Flamingo, London, 1984, pp. 15-31

14. Parts of this Introduction were in a paper delivered at the symposium, Border-lands: photography & cultural contest, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 31 Mar 2012

Time

The relationship of the photograph to ‘Time’ is discussed in chapter one, which examines how contemporary artists such as Anne Ferran, Rosemary Laing and Ricky Maynard reinvent the past through photography. The activities of nineteenth-century photographers such as George Burnell and Charles Bayliss are also discussed… The manipulation by artists and photographers of imaginative time – the time of looking at the photographic image – allows for consideration of the nexus between space and time, how subjects can be momentarily tethered and, equally, how they can float free.

Nation

Chapter two considers the idea of ‘Nation’: looking at the public role of the photograph in representing Australia at world exhibitions before Federation in 1901. Photography in this period enabled new classificatory systems to come into existence… Of particular importance was the use of the photograph to cement Darwinistic views that determined racial hierarchies according to superficial physical differences. The photograph also advertised the growing colonies to potential migrants and investors through the depiction of landscapes and amenities.

People

The third chapter, ‘People’, analyses the uncertain post-colonial heritage that all Australian inherit and how that can be evidenced and examined in photographs. The chapter encompasses portraits by Tracy Moffatt and George Goodman, for example, and considerations of where and how people lived and chose to be photographed. These include the people of the Kulin nation of Victoria, those who resided at Poonindie Mission in South Australia, the Yued people living at New Norcia mission in Western Australia, as well as the Henty family in Victoria, the Mortlocks of South Australia, the children living at The Bungalow in Alice Springs and the people of Tumut in New South Wales.

Place

‘Place’ is examined in chapter four, particularly in terms of the use of photography to enable exploration, whether to Antarctica (Frank Hurley), to map stars and further the natural sciences (Henry Chamberlain Russell, Joseph Turner), or to open up ‘wilderness’ for tourism or mining (JW Beattie, Nicholas Caire, JW Lindt, Richard Daintree) … Photographs are examined as both documents and imaginative interpretations of activity and place.

Transmission

Chapter five, ‘Transmission’, considers the traffic in photographs and the fascination with the medium’s reproducibility and circulation… The evidential aspect of the photograph has proven to be fleeting and only tangentially related to the thing it traces. The possibility of being able to fully decipher a photograph’s meaning is remote, even when it has been promptly ordered and annotated in some form of album. Each photographic form expands the possibility of instant and easy communication, but the swarm of material serves only to prove the impossibility of order, classification, and accuracy. The photograph as an aestheticised object continues regardless of platform, and the imaginative possibilities of the medium have not been exhausted.

Sections from Judy Annear. “Introduction,” in Judy Annear. The photograph and Australia. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2015. p. 12.

Charles Bayliss (Australian born United Kingdom, 1850-1897)

Group of local Aboriginal people, Chowilla Station, Lower Murray River, South Australia

1886

From the series New South Wales Royal Commission: Conservation of water. Views of scenery on the Darling and Lower Murray during the flood of 1886

Albumen photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1984

This tableaux of Ngarrindjeri people fishing was carefully staged by photographer Charles Bayliss in 1886. Not just subjects, they actively participated in the photography process. It was observed at the time that the fishermen arranged themselves into position, with “the grace and unique character of which a skilful artist only could show.”

“In one extraordinary image created in 1886 by the photographer Charles Bayliss, the Ngarrindjeri people of the lower Murray River were active participants in the staging of a fishing scene. Writing in his journal, Bayliss’s companion Gilbert Parker noted: “Without a word of suggestion, these natives arranged themselves in a group, the grace and unique character of which a skilful artist only could show.” Annear says the image looks like a museum diorama to modern eyes. “But these people were very active in deciding how they wanted to be photographed,” she says. “They were determined to create an image they felt was appropriate.”

The first photographs of indigenous Australians were formal, posed portraits, taken in blazing sunlight. The sitters are often pictured leaning against each other (stillness was required for long exposure times) with eyes turned to the camera and bodies wrapped in blankets or kangaroo skins. Some wore headdresses or necklaces that may or may not have belonged to them.

“Indigenous Australians agreed to be photographed out of curiosity, or perhaps for food,” says Judy Annear, curator of The photograph and Australia, a major new photography exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. “In the past, it was considered that these sorts of early pictures were indicative of the colonial gaze. But now there is a lot of research going on into how these early photos were made. Often, the local people would have been invited to come into a studio and they were paid. They would have been dressed up and told what to do.””

Text in quotations from Elissa Blake. “Art Gallery of NSW photography exhibition: Stories told in black and white,” on the the Sydney Morning Herald website April 2, 2015 [Online] Cited 28/05/2015.

Ernest B Docker (Australian, 1842-1923)

The Three Sisters Katoomba – Mrs Vivian, Muriel Vivian and Rosamund 7 Feb 1898

1898

Stereograph

Macleay Museum, The University of Sydney

Charles Nettleton (Australian, 1825-1902)

Untitled

1867-1874

Carte de visite

6.2 x 9.1cm image; 6.3 x 10.0cm mount card

Purchased 2014

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Charles Nettleton was a professional photographer born in the north of England who arrived in Australia in 1854, settling in Melbourne. He joined the studio of Townsend Duryea and Alexander McDonald, where he specialised in outdoor photography. Nettleton is credited with having photographed the first Australian steam train when the private Melbourne-Sandridge (Port Melbourne) line was opened on 12 September 1854. Nettleton established his own studio in 1858, offering the first souvenir albums to the Melbourne public. He worked as an official photographer to the Victorian government and the City of Melbourne Corporation from the late 1850s to the late 1890s, documenting Melbourne’s growth from a colonial town to a booming metropolis. He photographed public buildings, sewerage and water systems, bridges, viaducts, roads, wharves, and the construction of the Botanical Gardens. In 1861 he boarded the ‘Great Britain’ to photograph the first English cricket team to visit Australia and in 1867 was appointed official photographer of the Victorian visit of the Duke of Edinburgh. For the Victorian police he photographed the bushranger Ned Kelly in 1880. This is considered to be the only genuine photograph of the outlaw.

Tracey Moffatt (Australian, b. 1960)

I made a camera

2003

Photolithograph

Collection of the artist

© Tracey Moffatt, courtesy Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

The Art Gallery of New South Wales is proud to present the major exhibition The photograph and Australia, which explores the crucial role photography has played in shaping our understandings of the nation. It will run from 21 March to 8 June 2015.

Tracing the evolution of the medium and its many uses from the 1840s until today, this is the largest exhibition of Australian photography held since 1988 that borrows from collections nationwide. It presents more than 400 photographs by more than 120 artists, including Morton Allport, Richard Daintree, Paul Foelsche, Samuel Sweet, JJ Dwyer, Charles Bayliss, Frank Hurley, Harold Cazneaux, Olive Cotton, Max Dupain, Sue Ford, Carol Jerrems, Tracey Moffatt, Robyn Stacey, Ricky Maynard, Anne Ferran and Patrick Pound.

Iconic images are shown alongside works by unknown and amateur photographers, including photographic objects such as cartes de visite, domestic albums and the earliest Australian X-rays. The exhibition’s curator – Judy Annear, senior curator of photographs, Art Gallery of NSW – said:

“Weaving together the multiple threads of Australia’s photographic history, The photograph and Australia investigates how photography invented modern Australia. It poses questions about how the medium has shaped our view of the world, ourselves and each other. Audiences are invited to experience the breadth of Australian photography, past and present, and the sense of wonder the photograph can still induce through its ability to capture both things of the world and the imagination.”

The exhibition brings together hundreds of photographs from more than 35 private and public collections across Australia, England and New Zealand, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Library of Australia and the State Library of Victoria. Highlights include daguerreotypes by Australia’s first professional photographer, George Goodman, and recent works by Simryn Gill. From mass media’s evolution in the 19th century to today’s digital revolution, The photograph and Australia investigates how photography has been harnessed to create the idea of a nation and reveals how our view of the world, ourselves and each other has been changed by the advent of photography. It also explores how photography operates aesthetically, technically, politically and in terms of distribution and proliferation, in the Australian context.

Curated from a contemporary perspective, the exhibition takes a thematic rather than a chronological approach, looking at four interrelated areas: Aboriginal and settler relations; exploration (mining, landscape and stars); portraiture and engagement; collecting and distributing photography. A lavishly illustrated 308-page publication, The photograph and Australia (Thames & Hudson, RRP $75.00), accompanies the exhibition, reflecting its themes and investigating the medium’s relationship to people, place, culture and history.

Press release from the Art Gallery of New South Wales

David Moore (Australian, 1927-2003)

Migrants arriving in Sydney

1966, printed later

Gelatin silver photograph

30.2 x 43.5cm

Gift of the artist 1997

© Lisa, Karen, Michael and Matthew Moore

In this evocative image Moore condenses the anticipation and apprehension of immigrants into a tight frame as they arrive in Australia to begin a new life. The generational mix suggests family reconnections or individual courage as each face displays a different emotion.

Moore’s first colour image Faces mirroring their expectations of life in the land down under, passengers crowd the rail of the liner Galileo Galilei in Sydney Harbour was published in National Geographic in 1967.1 In that photograph the figures are positioned less formally and look cheerful. But it is this second image, probably taken seconds later, which Moore printed in black-and-white, that has become symbolic of national identity as it represents a time when Australia’s rapidly developing industrialised economy addressed its labour shortage through immigration. The strength of the horizontal composition of cropped figures underpinned by the ship’s rail is dramatised by the central figure raising her hand – an ambiguous gesture either reaching for a future or reconnecting with family. The complexity of the subject and the narrative the image implies ensured its public success, which resulted in a deconstruction of the original title, ‘European migrants’, by the passengers, four of whom it later emerged were Sydneysiders returning from holiday, alongside two migrants from Egypt and Lebanon.2 Unintentionally Moore’s iconic image has become an ‘historical fiction’, yet the passengers continue to represent an evolving Australian identity in relation to immigration.

1. Max Dupain and associates. Accessed 17/06/2006. No longer available online

2. Thomas D & Sayers A 2000, From face to face: portraits by David Moore, Chapter & Verse, Sydney

© Art Gallery of New South Wales Photography Collection Handbook, 2007

David Moore (Australian, 1927-2003)

Redfern Interior

1949

Silver gelatin print

26.7 x 35.4cm

Purchased with funds provided by the Art Gallery Society of New South Wales 1985

David Moore’s career spanned the age of the picture magazines (for example: Life, Time, The Observer) through to major commissions such as the Sydney Opera House, CSR, and self initiated projects like To build a Bridge: Glebe Island. The breadth and depth of his career means there is an extraordinary archive of material which describes and interprets the last 50 years of Australian life, the life of the region, and events in Britain and the United States. He was instrumental in advancing Australian photography throughout his career and in the early 1970s was active in setting up the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney. From well-known images such as Migrants arriving in Sydney to Redfern interior, Moore has documented events and conditions in Sydney.

Charles Bayliss (England, Australia 1850-1897)

Henry Beaufoy Merlin (England, Australia 1830-1873)

Untitled

c. 1872

Albumen photograph

Dimensions

24.5 x 29.4cm image/sheet

Gift of Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Sydney 2014

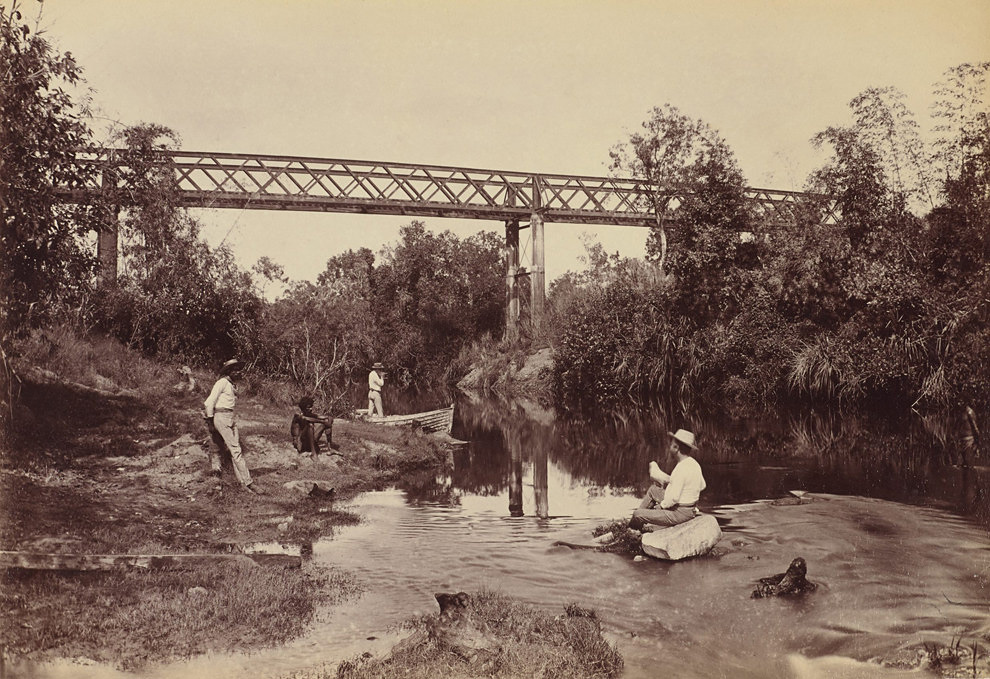

Paul Foelsche (Australian, 1831-1914)

Adelaide River

1887

Albumen photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of Josef & Jeanne Lebovic, Sydney 2014

This photo of people relaxing on the banks of the Adelaide River in the Northern Territory was taken by Paul Foelsche, a policeman and amateur anthropologist.

The collection of 19th century images brought together in The photograph and Australia show indigenous people in formal group portraits or as “exotic” subjects. They are photographed alongside early settlers, working as stockmen or holding tools. Amateur gentleman photographers such as the Scottish farmer John Hunter Kerr captured such images on his own property, Fernyhurst Station, in Victoria. Another amateur photographer, Paul Foelsche, the first policeman in the Northern Territory, took portraits of the Larrakia people, which have since become a priceless archive for their descendants.

NSW Government Printer

The General Post Office, Sydney

1892-1900

Albumen photograph

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, presented 1969

Melvin Vaniman (American, 1866-1912)

Panorama of intersection of Collins and Queen Streets, Melbourne

1903

Melvin Vaniman (American, 1866-1912)

Chester Melvin Vaniman (October 30, 1866 – July 2, 1912) was an American aviator and photographer who specialised in panoramic images. He shot images from gas balloons, ships masts, tall buildings and even a home-made 30-metre (98 ft) pole. He scaled buildings, hung from self-made slings, and scaled dangerous heights to capture his unique images.

Vaniman’s photographic career began in Hawaii in 1901, and ended some time in 1904. He spent over a year photographing Australia and New Zealand on behalf of the Oceanic Steamship Company, creating promotional images for the company, many as panoramas and which popularised the format in Australia, which was taken up with enthusiasm by Robert Vere Scott among others. During this time the New Zealand Government also commissioned panoramas.

Beginning in 1903, he spent over a year photographing Sydney and the surrounding areas. It was during this time that he created his best known work, the panorama of Sydney, shot from a hot air balloon he had specially imported from the United States. Vaniman is best known for his images of Hawaii, Australia, and New Zealand.

Text from the Wikipedia website

J. W. Lindt (Germany 1845 – Australia from 1862, Australia 1926)

Body of Joe Byrne, member of the Kelly gang, hung up for photography, Benalla

1880

Gelatin silver print

Australia’s first ever press photograph pushed boundaries few journalists would transgress today. Captured by J.W, Lindt in 1880, the photo shows the dead body of a member of Ned Kelly’s infamous gang, strung up on a door outside the jail house in Benalla in regional Victoria.

Joe Byrne died from loss of blood after being shot in the groin during the siege of Glenrowan pub. Another photographer is pictured mid-shot, while an illustrator walks away from the new technology with his hat on and portfolio tucked under his arm. “We see this as the first Australian press photograph. It has that spontaneity media photographs have, and it’s also very evocative with many different stories in it,” the gallery’s senior curator of photographs, Judy Annear, said.

Text from Rose Powell. “First Australian press photo shows body of Kelly Gang member Joe Byrne,” on the Sydney Morning Herald website March 20, 2015 [Online] Cited 30/05/2015.

Richard Daintree (Australian, 1832-1878)

Midday camp

1864-1870

Albumen photograph, overpainted with oils

Queensland Museum, Brisbane

This image was an albumen photograph (using egg whites to bind chemicals to paper) which was then hand-coloured with oil paints to bring it to life. The photographer took it in the 1860s to advertise Australia as a land of opportunity.

Ricky Maynard (Australian, b. 1953)

Ben Lomond, Tasmania , Cape Portland, Tasmania

The Healing Garden, Wybalenna, Flinders Island, Tasmania, from the series Portrait of a distant land

2005, printed 2009

Gelatin silver photograph, selenium toned

34 x 52cm

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Aboriginal Collection Benefactors’ Group and the Photography Collection Benefactors’ Program 2009

Ricky Maynard has produced some of the most compelling images of contemporary Aboriginal Australia over the last two decades. Largely self taught, Maynard began his career as a darkroom technician at the age of sixteen. He first established his reputation with the 1985 series Moonbird people, an intimate portrayal of the muttonbirding season on Babel, Big Dog and Trefoil Islands in his native Tasmania. The 1993 series No more than what you see documents Indigenous prisoners in South Australian gaols.

Maynard is a lifelong student of the history of photography, particularly of the great American social reformers Jacob Riis, Lewis Hines, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans. Maynard’s images cut through the layers of rhetoric and ideology that inevitably couch black history (particularly Tasmanian history) to present images of experience itself. His visual histories question ownership; he claims that ‘the contest remains over who will image and own this history…we must define history, define whose history it is, and define its purpose as well as the tools used for the telling it’.

In Portrait of a distant land Maynard addresses the emotional connection between history and place. He uses documentary style landscapes to illustrate group portraits of Aboriginal peoples’ experiences throughout Tasmania. Each work combines several specific historical events, creating a narrative of shared experience – for example The Mission relies on historical records of a small boy whom Europeans christened after both his parents died in the Risdon massacre. This work highlights the disparity between written, oral and visual histories, as Maynard attempts to create ‘a combination of a very specific oral history as well as an attempt to show a different way of looking at history in general’.

JW Lindt (Australian born Germany, 1845-1926)

No 37 Bushman and an Aboriginal man

1873

Albumen photograph

Grafton Regional Gallery Collection, Grafton, gift of Sam and Janet Cullen and family 2004

Professional photographers such as the Frankfurt-born John William Lindt (who became famous for photographing the capture of the Kelly Gang at Glenrowan in 1880) took carefully posed tableaux images in his Melbourne studio. One set of Lindt photographs, taken between 1873 and 1874, show settlers and indigenous people posing with the tools of their trade. One unusual image shows a settler holding a spear and a local man holding a rifle.

Annear says the photographs speak of a time when early settlers and indigenous people were engaged in an exchange of cultures. “These photos weren’t just a passive, one-way process,” Annear says. “It wasn’t just about capture and exoticism. We are finding contemporaneous accounts that point to a level of exchange going on that was extremely important. These photos show who those people were, where they lived and what they were doing. They have a very powerful presence in that regard, and Aboriginal people today are going back through these photographs in order to trace their family trees.” …

Annear says she could have put together an exhibition of images of the “great suffering” experienced by Aboriginal people in Australia, but chose not to. “I found the 19th century material so rich and strong and most people aren’t aware of these images. It seemed like a great opportunity to bring them forward,” she says. “I don’t want to whitewash history, but I do want people to see how rich life was, how people were adapting, and then how that was removed. After Federation and the White Australia policy and other assimilation policies, photos of indigenous people seem to disappear. Why did they disappear? The people were still here. They were greatly diminished in many senses, but nonetheless they were still here.”

Elissa Blake. “Art Gallery of NSW photography exhibition: Stories told in black and white,” on the Sydney Morning Herald website, April 2, 2015 [Online] Cited 30/05/2015

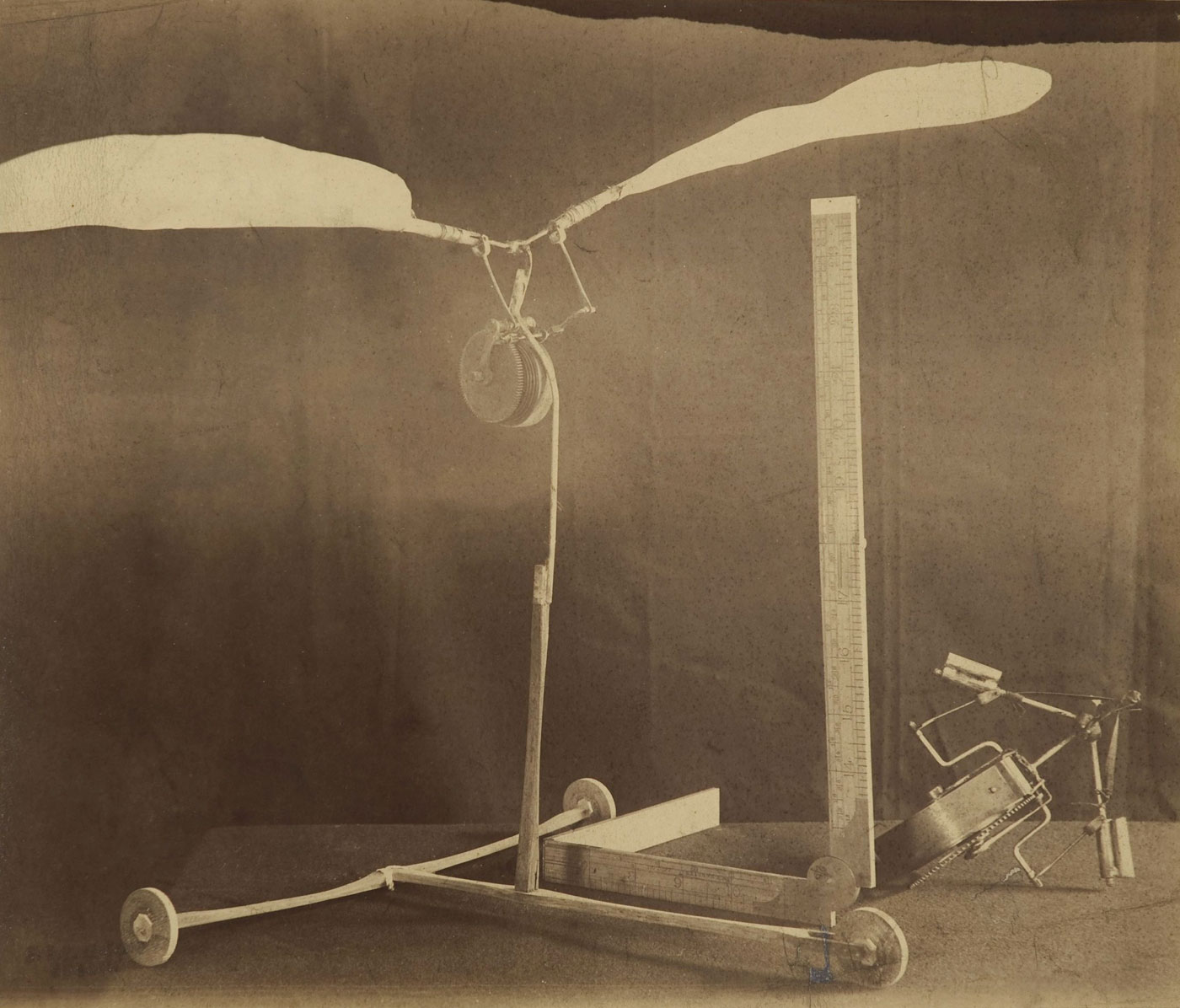

Charles Bayliss (Australian born England, 1850-1897)

Lawrence Hargrave trochoided plane model

1884

Albumen photograph

Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, gift of Mr William Hudson Shaw 1994

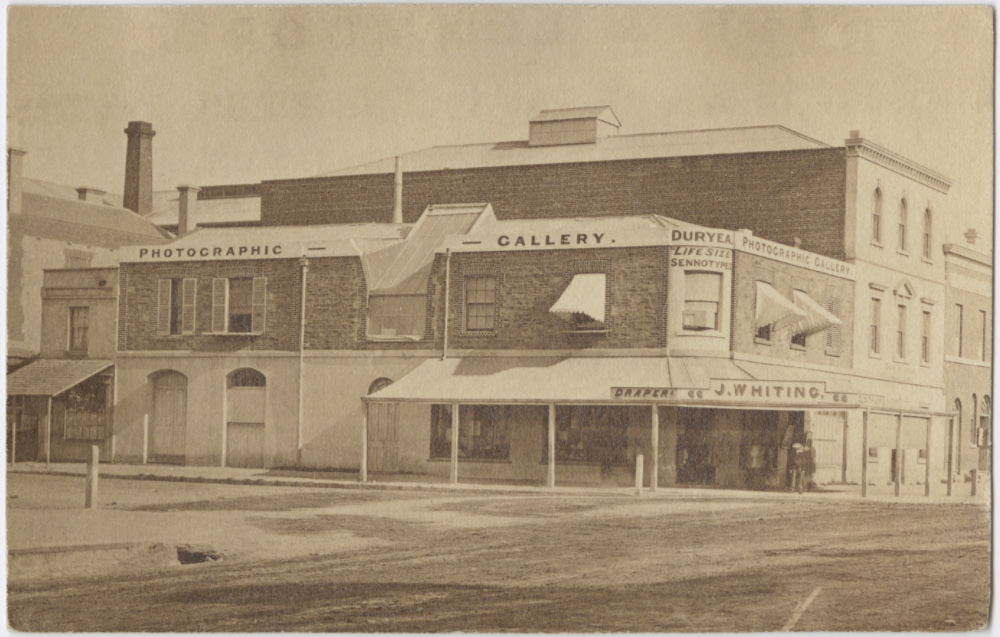

Unknown photographer

Duryea Gallery, Grenfell Street, Adelaide

c. 1865

Carte de visite

State Library of South Australia, Adelaide

J. J. Dwyer (Australian, 1869-1928)

Kalgoorlie’s first post office

c. 1900

Gelatin silver photograph

Kerry Stokes Collection, Perth

Photo: Acorn Photo, Perth

Harold Cazneaux (Australian, 1878-1953)

Spirit of endurance

1937

Gelatin silver photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, gift of the Cazneaux family 1975

Keast Burke (New Zealand, Australia 1896-1974)

Husbandry 1

c. 1940

Gelatin silver photograph, vintage

30.5 x 35.5cm image/sheet

Gift of Iris Burke 1989

Eric Keast Burke (16 January 1896 – 31 March 1974) was a New Zealand-born photographer and journalist.

Unknown photographer

Isabella Carfrae on horseback, Ledcourt, Stawell, Victoria

c. 1855

Daguerreotype, hand-tinted

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 2012

Unknown photographer

Isabella Carfrae on horseback, Ledcourt, Stawell, Victoria

c. 1855

Daguerreotype, hand-tinted

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, purchased 2012

“In the late 19th century, cameras were taking us both inside the human body and all the way to the moon. By the 1970s the National Gallery of Victoria had begun collecting photographic art, and within another decade the digital revolution was underway. But this exhibition – the largest display of Australian photography since Gael Newton mounted the 900-work Shades of Light: Photography and Australia 1838-1988 at the National Gallery of Australia 27 years ago – is not chronological.

It opens with a salon hang of portraits of 19th and 20th century photographers, as if to emphasise their say in what we see, and continues with works grouped by themes: Aboriginal and settler relations; exploration; mining, landscape and stars; portraiture and engagement; collecting and distributing photography.

“A number of institutions and curators have tackled Australian photography from a chronological perspective and have done an extremely good job of it,” Annear says. “I have used their excellent research as a springboard into another kind of examination of the history of photography in this country. Nothing in photography was actually invented here, so I have turned it around and considered how photography invented Australia.”

Most of the photographs – about three quarters of the show, in fact – date from the first 60 years after Frenchman Louis Daguerre had his 1839 revelation about how to capture detailed images in a permanent form. Annear says the decades immediately following photography’s arrival in Australia provide a snapshot of all that has followed since.

“In terms of the digital revolution it is interesting to look back at the 19th century. What is going on now was all there then, it is just an expansion. There is a very clear trajectory from the birth of photography towards multiplication. After the invention of the carte de visite in the late 1850s they were made like there was no tomorrow. There are millions of cartes de visite in existence.”

There are quite a few of these small card-mounted photographs (the process was patented in Paris, hence the French) in the exhibition too, including one of a woman reflected in water at Port Jackson dating from circa 1865. With the trillions of images now in existence, it is easy to forget that once upon a time catching your reflection in the water, glass or a mirror was the only way to glimpse your own image (short of paying hefty sums for an artist to draw you).

After the invention of photography, people were quick to see how easily they could manipulate the impression created. While photographs are about fixing a moment in time, we can never be really sure just what it is they are fixing. “It’s not as simple as windows and mirrors – what we are looking at has always been constructed in some way,” Annear says. “What’s interesting about the medium is that you think it’s recording, fixing and capturing, but it is just creating an endless meditation on whatever a photograph’s relationship might be to whatever was real at the time it was taken.”

Extract from Megan Backhouse. “How the Photograph Shaped a Nation,” on the Art Guide Australia website, 20 April 2015 [Online] Cited 30/05/2015. No longer available online.

Sue Ford (Australian, 1943-2009)

Self-portrait

1986

From the series Self-portrait with camera (1960-2006) 2008

Colour Polaroid photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by the Paul & Valeria Ainsworth Charitable Foundation, Russell Mills, Mary Ann Rolfe, the Photography Collection Benefactors and the Photography Endowment Fund 2015

© Sue Ford Archive

George Goodman (Australian born England, 1815-1891)

Caroline and son Thomas James Lawson

1845

Daguerreotype

State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, presented 1991

Olive Cotton (Australian, 1911-2003)

Only to taste the warmth, the light, the wind

c. 1939

Gelatin silver photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased with funds provided by John Armati 2006

Unknown photographer

John Gill and Joanna Kate Norton

1856

Albumen photograph

Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria, Melbourne

Unknown photographer

Alfred and Fred Thomas, proprietors of the Ravenswood Hotel

1880-1890

Tintype

State Library of Western Australia, Perth

Mervyn Bishop (Australian, b. 1945)

Prime Minister Gough Whitlam pours soil into the hands of traditional land owner Vincent Lingiari, Northern Territory

1975

Type R3 photograph

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Hallmark Cards Australian Photography Collection Fund 1991

© Mervyn Bishop. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Mervyn Bishop (born July 1945) is an Australian news and documentary photographer. Joining The Sydney Morning Herald as a cadet in 1962 or 1963, he was the first Aboriginal Australian to work on a metropolitan daily newspaper and one of the first to become a professional photographer. In 1971, four years after completing his cadetship, he was named Australian Press Photographer of the Year. He has continued to work as a photographer and lecturer.

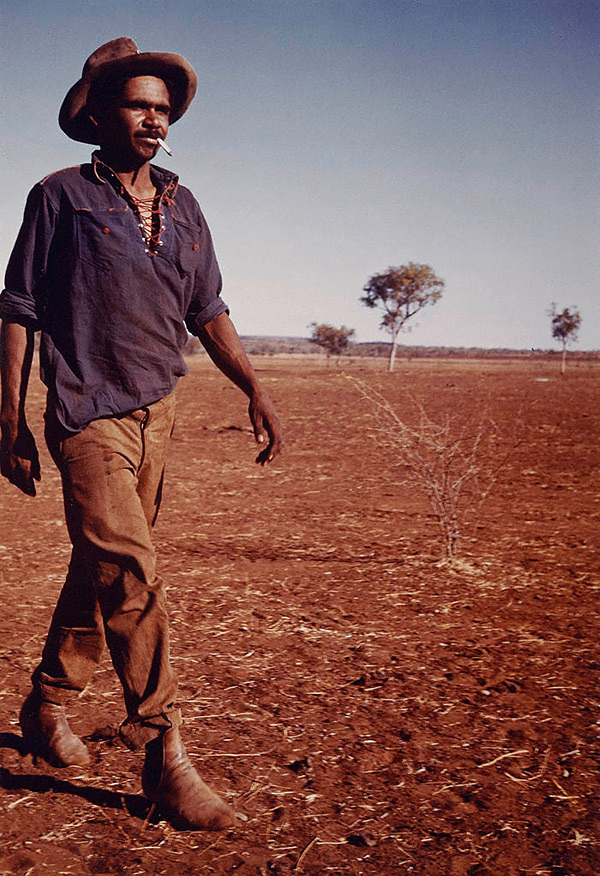

Axel Poignant (England, Australia, England 1906-1986)

Aboriginal stockman, Central Australia

c. 1947, printed 1982

Type C photograph

35.6 x 24.4cm image/sheet

Purchased 1984

© Courtesy Roslyn Poignant

Though not born in Australia, Axel Poignant’s work is largely about the ‘Outback’, its flora and fauna and the traditions of Australian and Indigenous identity. Poignant was born in Yorkshire in 1906 to a Swedish father and English mother, and arrived in Australia in 1926 seeking work and adventure. After tough early years of unemployment and homelessness, he eventually settled in Perth and found work as a portrait photographer, before taking to the road and the bush in search of new subjects. Poignant became fascinated with the photo-essay as a means of adding real humanity to the medium, and much of his work is in this form. The close relationships he developed with Aborigines on his travels are recorded in compassionate portraits of these people and their lives – the low angles and closely cropped frames appear more natural and relaxed than the stark compositions of earlier ethnographic photography.

Nicholas Caire (Australian born England, 1837-1918)

Fairy scene at the Landslip, Blacks’ Spur

c. 1878

Albumen photograph

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 1994

Nicholas John Caire (28 February 1837 – 13 February 1918) was an Australian photographer. Caire was born in Guernsey, Channel Islands, to Nicholas Caire and Hannah Margeret. As a boy Caire spoke French found he had a passion for photography that his parents encouraged. Caire moved to Adelaide, Australia, along with both his parents in 1860. Around this time Caire Found a mentor in Townsend Duryea. in 1867 he opened his own studio in Adelaide, Australia. He was married to Louisa Master in 1870 and then shortly after moved to Talbot, Victoria where he continued his photography and started to write for Life and Health Magazine. Caire died in 1918 in Armadale, Victoria.

Frank Styant Browne (Australian born England, 1854-1938)

Hand

1896

X-ray

Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery collection, Launceston

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

You must be logged in to post a comment.